Synthesis of Chitosan-based GCPs

The chitosan backbone was prepared using a method adopted by Sashiwa et al [

19]. For complete dissolution to take place the CHI-CSA salt was freeze-dried. The solid was found to readily dissolve in DMSO. With this development further chemical modification of CHI could be carried out in homogeneous water-free conditions. Many factors in sourcing and manufacturing CHI affect the characteristics and composition of the final product. Since the amino groups of CHI initiate grafting, it is important to establish the fraction of available amino groups prior to modification.

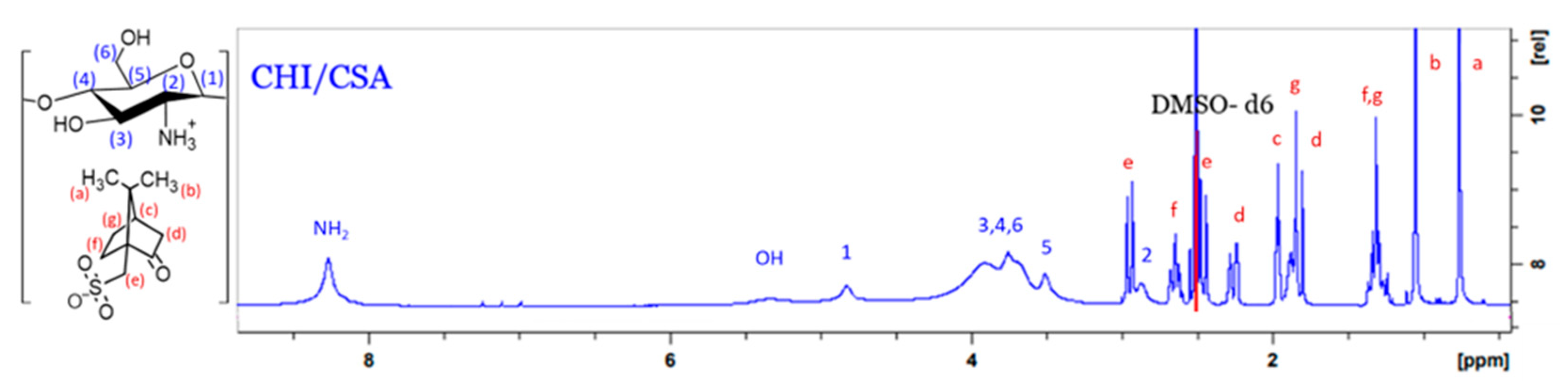

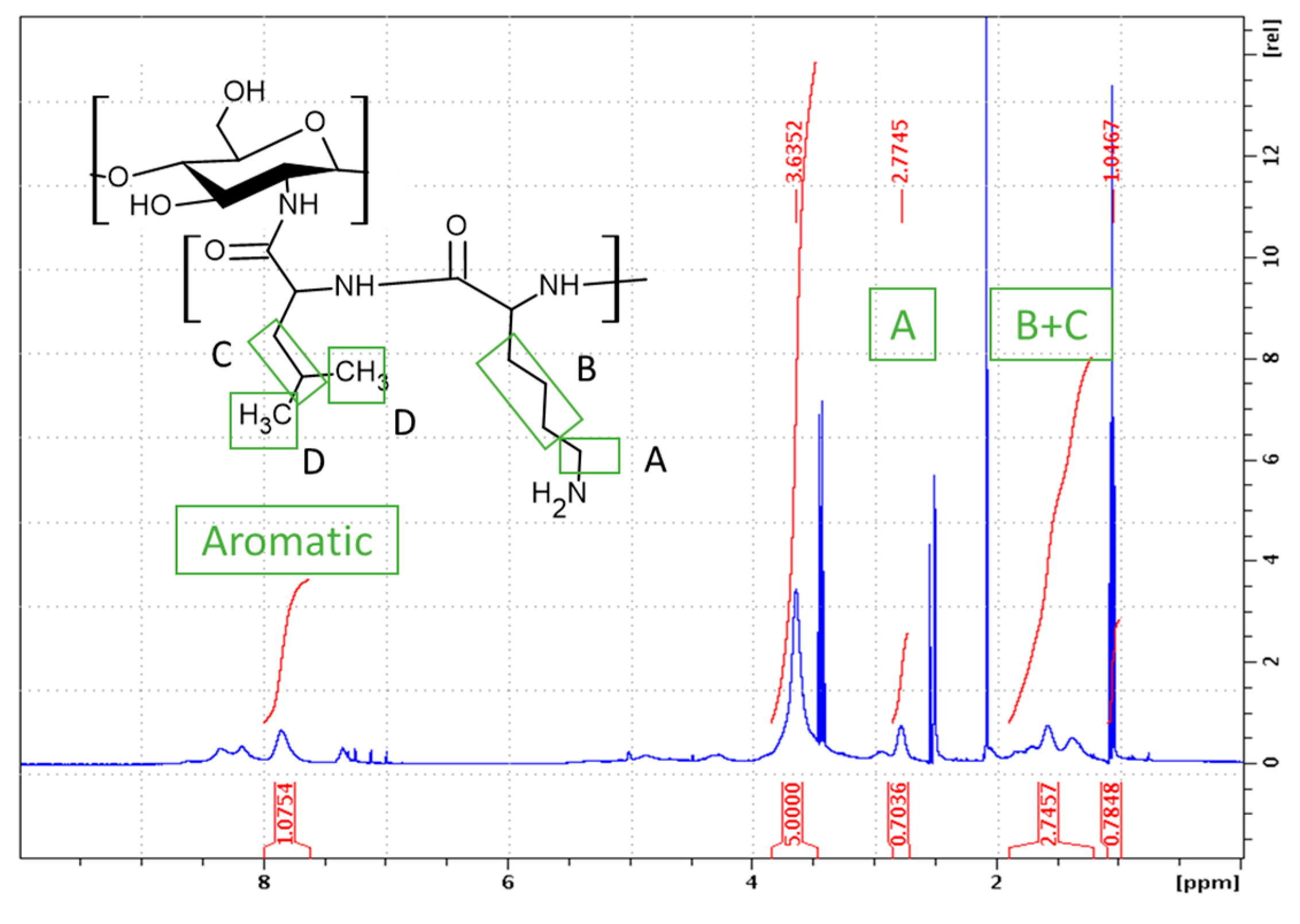

1H NMR spectrum of CHI-CSA in DMSO-d

6 is presented in

Figure 2. The signals at 3.5 ppm, 4.8 ppm, and 8.3 ppm are attributed to the -5, -1, and -NH

2 hydrogens of CHI, respectively. The hydrogens bound to the pyranose ring (3, 4, 5, and 6) are assigned to a broad peak at about 3.8 ppm.

The degree of acetylation was calculated using a method proposed by Weinhold et al., where the area of the acetyl CH

3 hydrogens

, and the H2-H6 signals

of CHI are used according to Eq. 1 [

21]:

The %DA was found to be > than 99%. Literature reports that N-acetyl linkages, as well as main chain (glycosidic linkages) of CHI, are susceptible to acidic hydrolysis [

22]. It is likely that during the dissolution of CHI the acetyl groups are cleaved while in the presence of excess CSA.

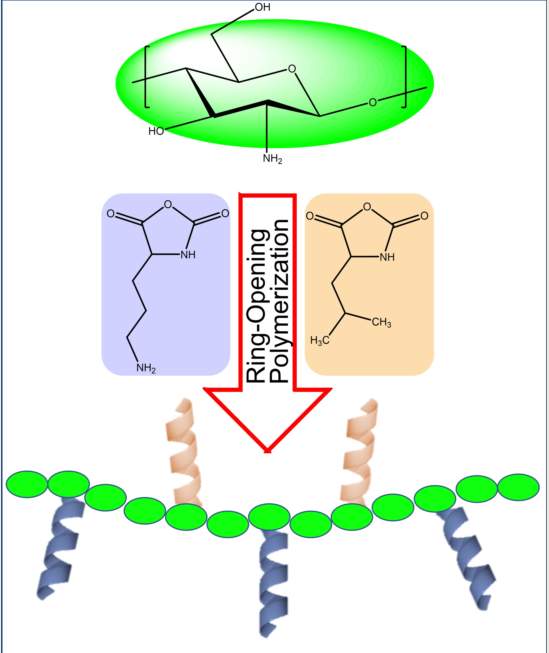

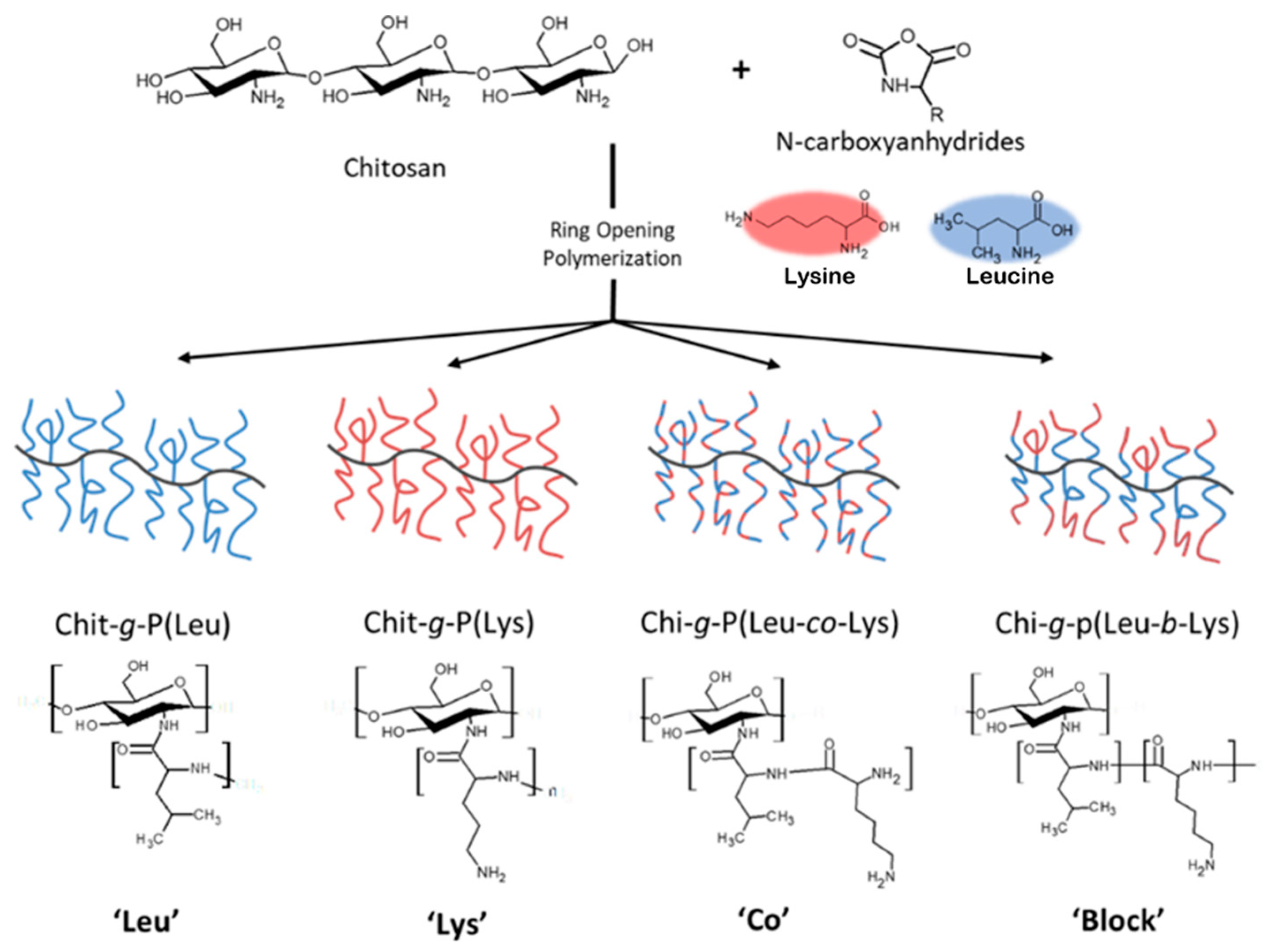

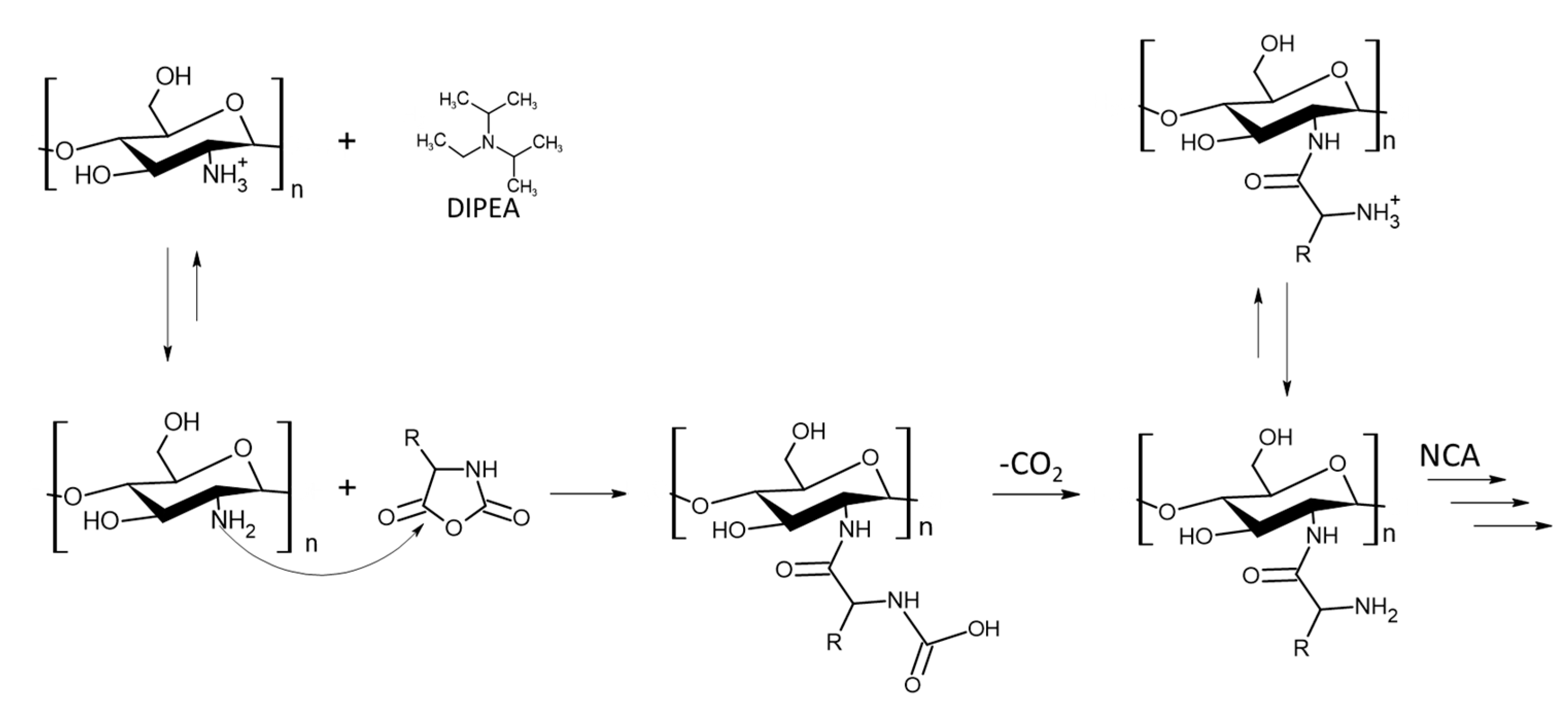

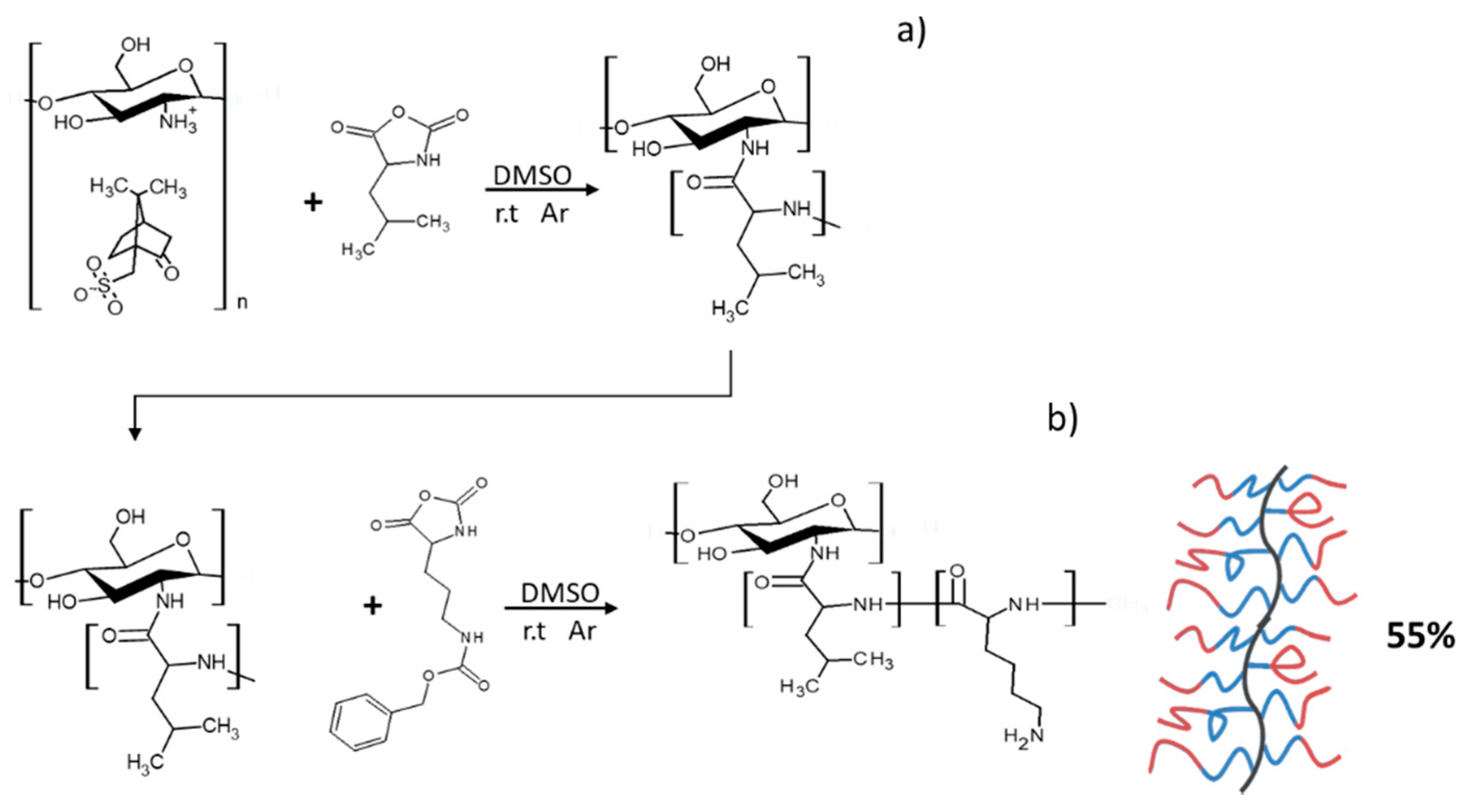

CHI-graft-polypeptides could yield a versatile material with the combined characteristics of its components, tunable amphiphilicity, and potentially controlled interactions with the environment. Several research groups have synthesized such materials using the amino group of CHI to initiate ROP of amino acid NCAs (

Figure 3). However, the restricted solubility of CHI limits the number of synthetic pathways. Kurita et al. and Chi et al. synthesized CHI-g-poly(γ-methyl L-glutamate) and CHI-g-poly(L-lysine) using a biphasic interfacial approach in ethyl acetate and water [

23, 24]. Alternatively, the synthesis of CHI-g-Poly(l-glutamic) acid and Poly(lysine-ran-phenylalanine) copolymers was accomplished in homogenous conditions using a soluble form of CHI, 6-O-triphenylmethyl CHI, in anhydrous DMF [

25]. In this work, we adopted an approach first utilized by Perdith et al. [

26] who synthesized CHI-graft-poly(sodium-L-glutamate) nanoparticles using the primary amine sulfonate salt, CHI-CSA, as a macroinitiator in DMSO. Extending this strategy, we explored the synthesis of CHI based GCPs with a hydrophobic L-leucine and cationic hydrophilic L-lysine amino acids.

The CHI-CSA was rapidly dissolved under argon in dry DMSO to which 0.3 molar equivalents of DIPEA with respect to –NH

3+ of CHI-CSA was added. The addition of DIPEA served to suppress acid-catalyzed cleavage of chitosan and increase the propagation rate of NCA-ROP. Control over the reactivity of the growing polymer chain end is critical to achieve a high molecular weight with optimal conditions often necessary to be determined empirically. Amine salts such as CHI-CSA have diminished reactivity as a nucleophile due to the formation of the inactive protonated amines -NH

3+. Polymerizations initiated with hydrochloride salts were found to yield single NCA addition and required elevated temperatures to proceed [

27, 28]. Since CHI degrades in the presence of sulfonic acids, we adjusted the equilibrium of free amines by adding the base instead of temperature (

Figure 4). DIPEA was selected as it is a sterically hindered base capable of scavenging protons without acting as a nucleophile. The addition of 0.3 equivalents of DIPEA to individual ammonium group of CHI-CSA was found to effectively yield graft copolymers after 3 days at room temperature. Upon completion the products were precipitated with diethyl ether and sequentially washed with THF and water to remove any starting materials and bi-products.

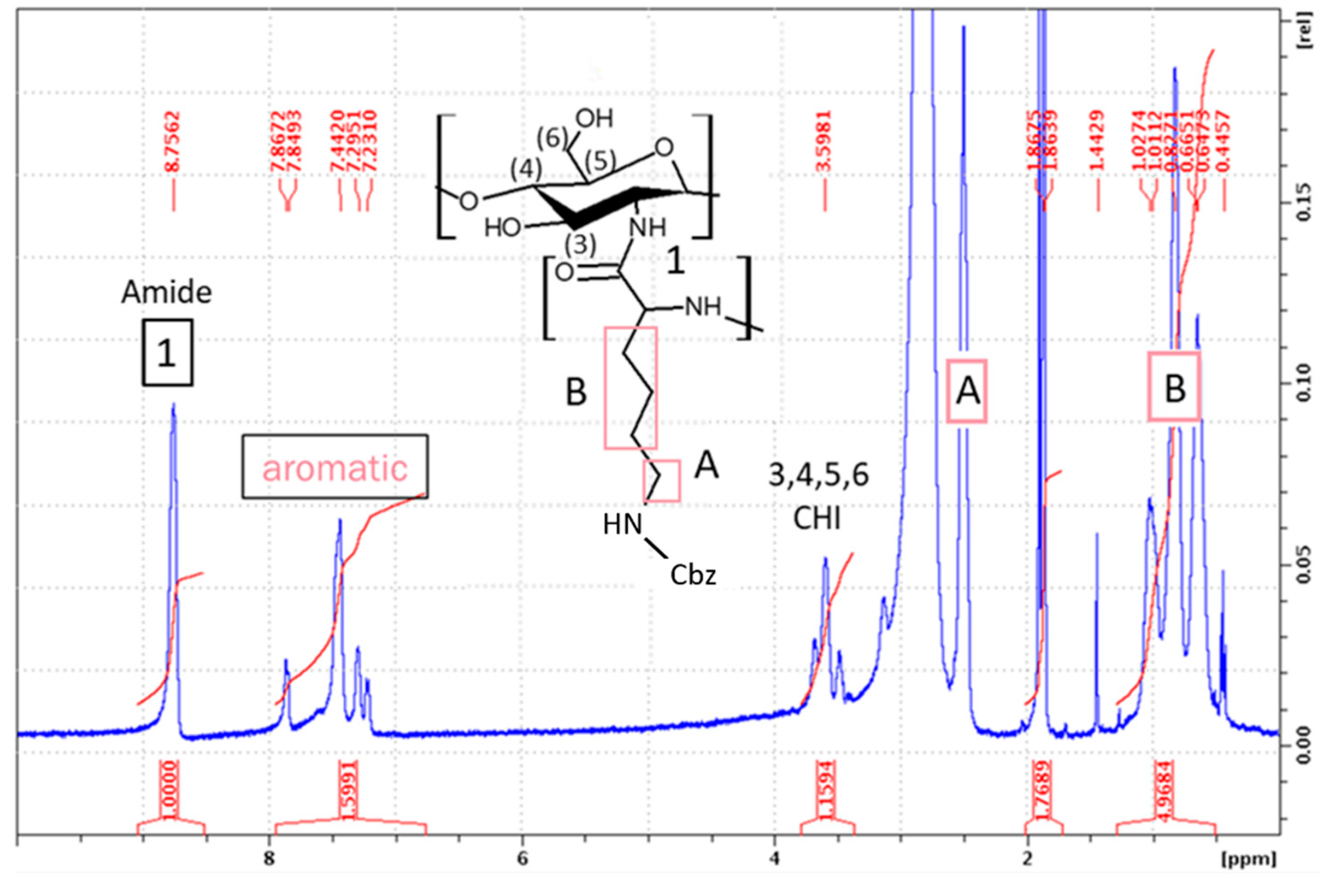

Synthesis of CHI-graft-Poly(L-lysine(Z))

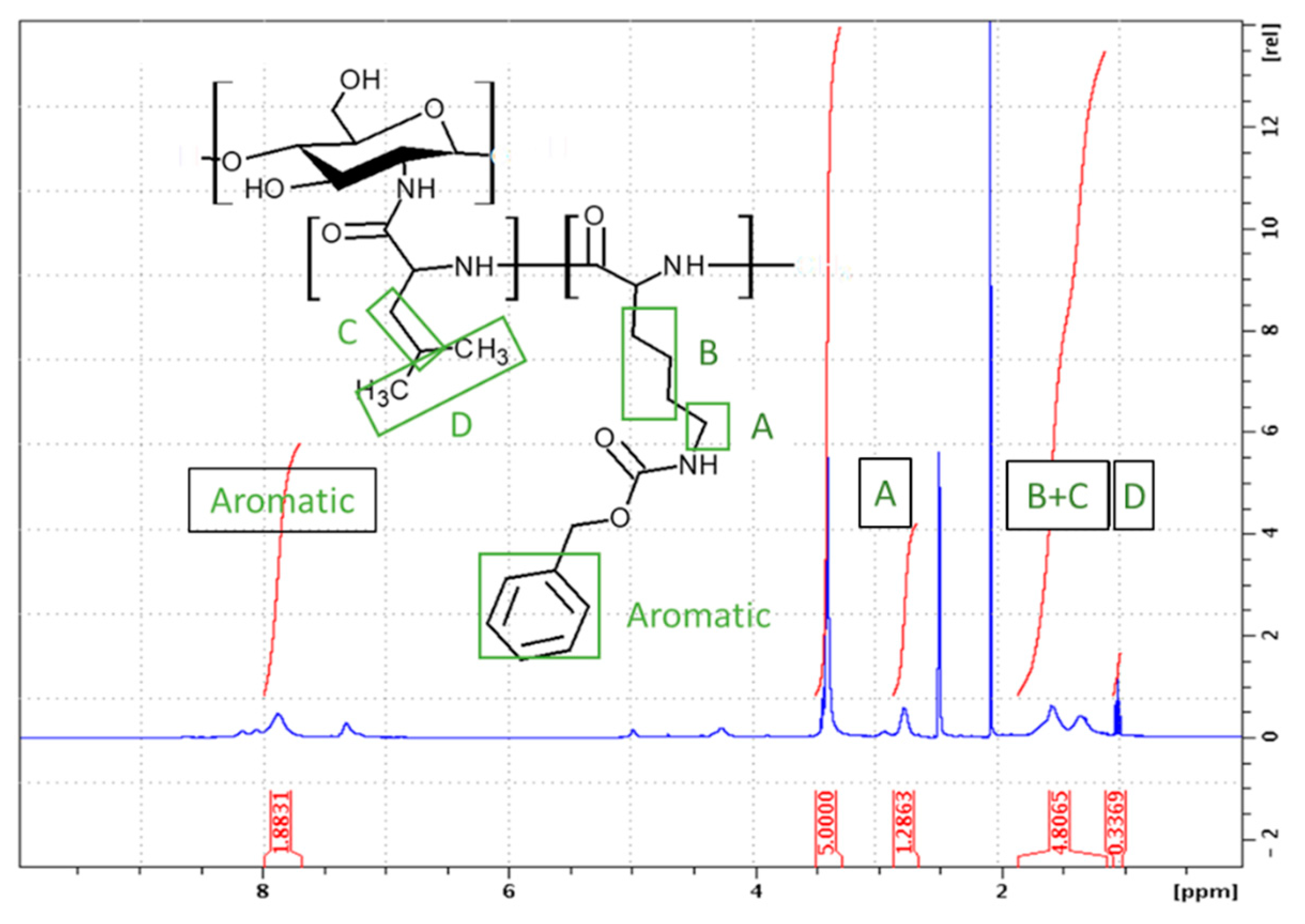

Synthesis of CHI-graft-Poly(L-lysine(Z)) was carried out in standard conditions using a Cbz-protected form of L-lysine, N-ε-Carbobenzyloxy-L-lysine NCA (L-lysine(Z)-NCA). The ratio between the CHI and L-lysine(Z) NCA repeating units (CHI:Lys) was estimated by dividing the normalized integral value of the CHI protons 3H–6H (5 protons) by normalized integral value of the L-lysine(Z) B signal (6 protons) (

Figure 5). A ratio of 1:0.43 for CHI to aliphatic lysine protons was found according to the Eq. 2:

where, A

pyranose is the area of 5 protons of the pyranose ring of CHI, B

Akyl is the area of 6 aliphatic protons of L-lysine, and A

Lys A is the area of the 2 remaining aliphatic protons of L-lysine.

The Cbz protecting groups of L-lysine(Z) units were removed in two sequential deprotection reactions using HBr/AcOH and TFA. This yielded a water-soluble product rich in NH

2 functionalities, the deprotection degree was found to be 62% using Eq. 3:

where A

aromatic is the area of the 5 aromatic protons of the benzyloxycarbonyl protecting group of L-lysine(Z).

Synthesis of CHI-graft-poly(lysine-co-leucine)

Following the established procedure, CHI-graft-poly(L-lysine-co-L-leucine) was synthesized by copolymerization of NCA L-lysine and L-leucine in the presence of CHI for a 49% yield. A feed ratio of 1:1.5:1.5 (CHI-to-Lys-to-Lue) was selected so that the total NCA concentration remained consistent. As stated previously, L-leucine was selected as the hydrophobic component of the GCP. Additionally, L-Leucine allows for straightforward characterization of L-lysine(Z) deprotection as its proton resonances do not overlap with the aromatic protons of the Cbz protecting group. Upon work up the ratio of amino acids to CHI was determined with

1H NMR using Eqs. 4 and 5:

where 𝐴

B+𝐶 = 6∗(1/2)𝐴

𝐿𝑦𝑠 A + 3∗𝐴

𝐿𝑒𝑢 𝐶, A

pyranose is the area of 5 protons on the pyranose ring of chitosan, A

Lys A is the area of 2 alkyl protons on Lysine, and A

B+C is the area of 3 protons from leucine and 6 alkyl protons from lysine. The CHI:Lys ratio was determined to be 1:0.35 (

Figure 6). With this information the ratio of CHI:Leu can be calculated using the resonance peak of B+C which consists of 6 lysine and 3 leucine protons. Upon substitution of A

Lys B into Eq. 5 the CHI:Leu was found to be 1:0.22. Similarly, the extent of deprotection was found to be 39%.

Synthesis of block GCPs

Amphiphilic GCPs with block sequences may adopt a number of conformations to as a result of various interactions with the local environment [

29, 30]. Polypeptide block copolymers can be prepared in a one-pot synthesis where NCAs are sequentially added to the polymerization mixture. This technique allows for the synthesis of polymers with potentially complex structures that are often poorly defined and difficult to characterize. In our work we synthesized the block graft copolymer, CHI-graft-Poly(Leucine-block-Lysine), in a two-step sequential graft copolymerization with NCA leucine and lysine, respectively (

Figure 7). First, CHI initiated NCA-ROP of L-leucine at a ratio of 1:3 (CHI amino groups-to-NCA) to yield a CHI-g-poly(L-leucine) with a yield of >90%. The product was characterized with

1H NMR to determine the actual ratio of CHI:Leu. However, the peaks associated with the CHI backbone protons were difficult to observe due to matrix effects. We observed such silencing of CHI. This is due to the fact that free CHI is insoluble in a solvent and the graft copolymer adopts a conformation where CHI collapses while the sidechains swell thus providing solubility of the entire macromolecule. On second step, CHI-g-poly(L-leucine) was subjected to NCA-ROP of L-lysine(Z). Ideally, only the amino groups present on the propagating ends of the polyleucine will initiate polymerization. However, unreacted amino groups on CHI may also serve as grafting sites yielding blocks of poly(L-lysine) directly attached to the CHI backbone. Regardless, the resulting product will still adopt configurations that maximize favorable interactions with the environment and access novel conformations and assemblies. Upon work up, the ratio of the amino acid blocks to CHI was evaluated with

1H NMR using Equations 5 and 6:

=where, A

pyranose is the area of 5 protons on the pyranose ring of chitosan, A

Lys A is the area of 2 alkyl protons on Lysine, and A

B+C is the area of 3 protons from leucine and 6 alkyl protons from lysine. The CHI:Lysine ratio was determined to be 1:0.65 from Equation (6). With this information, the ratio of CHI:Leu was calculated using the combintion of peaks of B+C which consists of 6 lysine and 3 leucine protons. Upon substitution of A

Lys A into Equation (5) the CHI:Leu was found to be 1:0.31. Similarly, the extent of Cbz-deprotection was determined to be 45% by evaluating the resonances A

aromatic and A

Lys A (

Figure 8). It is important to note that this value may be underestimated due to matrix effects. The graft copolymer can adopt conformations that place protected and deprotected lysine in distinct environments.

In conjunction with CHI-graft-Poly(L-leucine-block-L-lysine), which has a hydrophobic core and cationic shell, we made an attempt to synthesize CHI-graft-Poly (L-lysine-block-L-leucine) “reverse-block”. The polymer has been successfully obtained and isolated. Unfortunately, upon deprotection it was not soluble in water and thus could not be used any further.

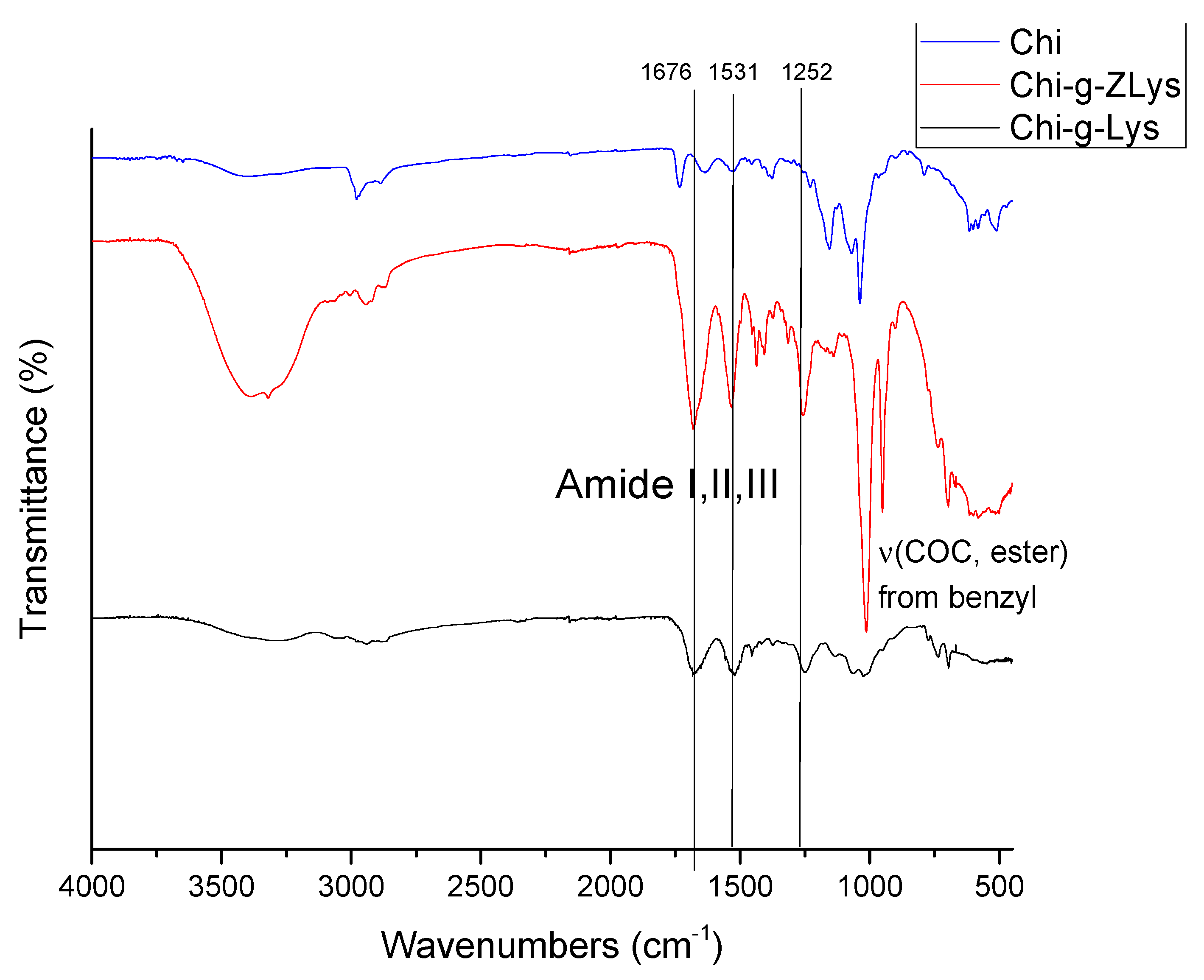

FTIR spectroscopic analysis was employed to characterize the final products and confirm the grafting of the peptide chains (

Figure 9). CHI was evaluated and compared after each step of the synthesis. In all spectra the absorbance of amide bands I (1676 cm

-1), II (1531 cm

-1), and III (1252 cm

-1) appear after ROP, supporting the successful grafting of polypeptides. Additionally, the disappearance of the C-O-C benzyl stretch upon deprotection indicates the removal of the carboxybenzyl group from grafted polylysine.

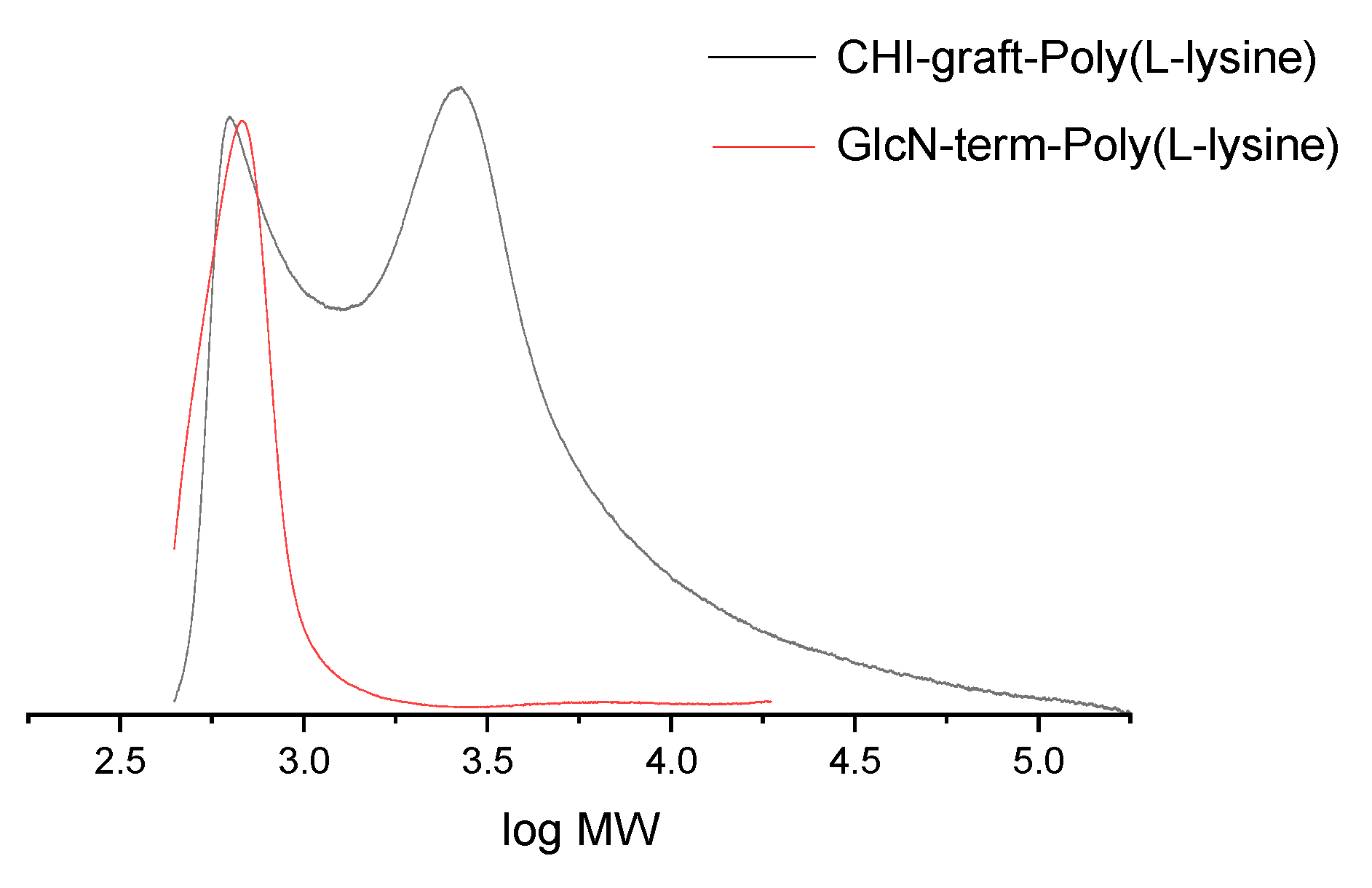

We used SEC to assess the molecular weight of some of the products. In general, characterization charged polymers with SEC poses substantial challenges caused by specific interactions of the polymer and the stationary phase of the column, and a lack of standards that accurately represent the hydrodynamic radius of nonlinear molecules and polyelectrolytes [

31, 32]. We used aprotic solvent DMF in order to minimize ionization of the polymeric products. Only two products were soluble in DMF: CHI-graft-Poly(L-lysine) and a linear model compund GlcN-term-poly(lysine)). Our attempts to use SEC for this and other compunds dissolved in water resulted in extremely low elution volumes corrsponding to high molecular weights beyond any possibility which indicated either strong ionization of the products or formation of aggregates.

Figure 10.

SEC of CHI-graft-Poly(L-lysine) (black) and a linear model compund GlcN-term-poly(lysine)) (red) in DMF.

Figure 10.

SEC of CHI-graft-Poly(L-lysine) (black) and a linear model compund GlcN-term-poly(lysine)) (red) in DMF.

The results of SEC of CHI-graft-Poly(L-lysine) and GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine)) are shown in

Figure 10. The molecular weight of GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine)) is 627 g/mol. Taking into account the weight of terminal GlcN fragment 178 g/mol, we determine the length of poly(L-lysine) is about 3.5 units. This finding fits well with the synthesis when 3-fold (molar) amount of lysine(Z) NCA monomer was added to GlcN initiator. Some amount of GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine)) is also observed on the SEC of CHI-graft-Poly(L-lysine), while the main broad peak has averaged 3250 g.mol. Taking into account the molar ratio 1:0.65 of CHI and L-lysine from NMR, we obtain ave. 2.5 poly(L-lysine) chains of ave. 3.5 units long grafted to CHI backbone composed of 13 units of glucosamine.

Antimicrobial Activity

Following the characterization of all of our products, we examined the antimicrobial activity of our graft-copolymers. AMPs preferentially bind to the plasma membrane bilayer (PMB) of bacteria through electrostatic interactions. The selectivity in binding arises from differences in the relative abundance and distribution of charged and hydrophobic phospholipids. In line with this model, many reports cite that an optimum level of hydrophobicity is required to sufficiently facilitate interactions with fatty acyl chains to trigger membrane permeabilization [

33]. However, AMPs with increased hydrophobic content can bind to mammalian membranes and exhibit increased toxicity [

34].

In the case of chitosan-graft-polypeptides, several variables create a more complex picture of selectivity. For example, many of the naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides characterized to date possess a net positive charge, ranging from +2 to +9 [

35], whereas the GCPs in this work potentially carry more positive charges per macromolecule. From this perspective, they may bind to cells irrespective of their composition and greatly reduce selectivity or efficiency. Additionally, if the GCPs do in fact deliver a high local concentration of peptide mass to the membrane interface, then off-target interactions with host cells could trigger cell death and lead to increased cytotoxicity. However, membrane adsorption is a poorly defined process in a complex environment. Off-target interactions such as protein adsorption and cation screening may substantially affect the electrostatic potential of the GCP. Additionally, outside the cytoplasmic membrane of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, there is a peptidoglycan layer consisting of glycan chains interconnected by peptide side chains [

36]. GCPs in this work mimic the composition of bacteria cell walls and may provide complementary interactions in that environment. This additional structural affinity may promote selectivity and offset hydrophobic binding to mammalian cells.

Finally, due to the large molecular weight of the GCPs small changes in the mole fraction of its components can lead to dramatic changes in adsorption behavior. All these traits combined make it difficult to target compositions that exhibit strong selectivity. With this in mind, the synthesized chitosan-graft-polypeptides were initially screened for cytotoxicity.

The colorimetric MTT assay was utilized to assess mammalian cell biocompatibility and in vitro cytotoxicity. In this experiment the GCPs were tested against Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDF) cells. HDF cell were chosen as they are widely used as model to mimic the interaction of materials with human skin. They are also key components in inflammatory processes and wound healing. Due to the large molecular weight of GCPs they are likely best suited for topical applications rather than systemic administration. The cytotoxicity GCPs against HDF cells was evaluated over more common hemolytic activity.

In general, CHI-graft-Poly(L-lysine), exhibited the lowest toxicity with a minimum cell viability of 65% at 30 mg/ml. Glucosamine terminiated poly(lysine) was slightly more toxic with 50% viability at 30 mg/ml. CHI-graft-poly(Lys-co-Leu) and CHI-graft-poly(Leu-block-Lys) exhibited similar profiles and were substantially more toxic with nearly 90% cell death at the solubility limit of 30 mg/ml (See

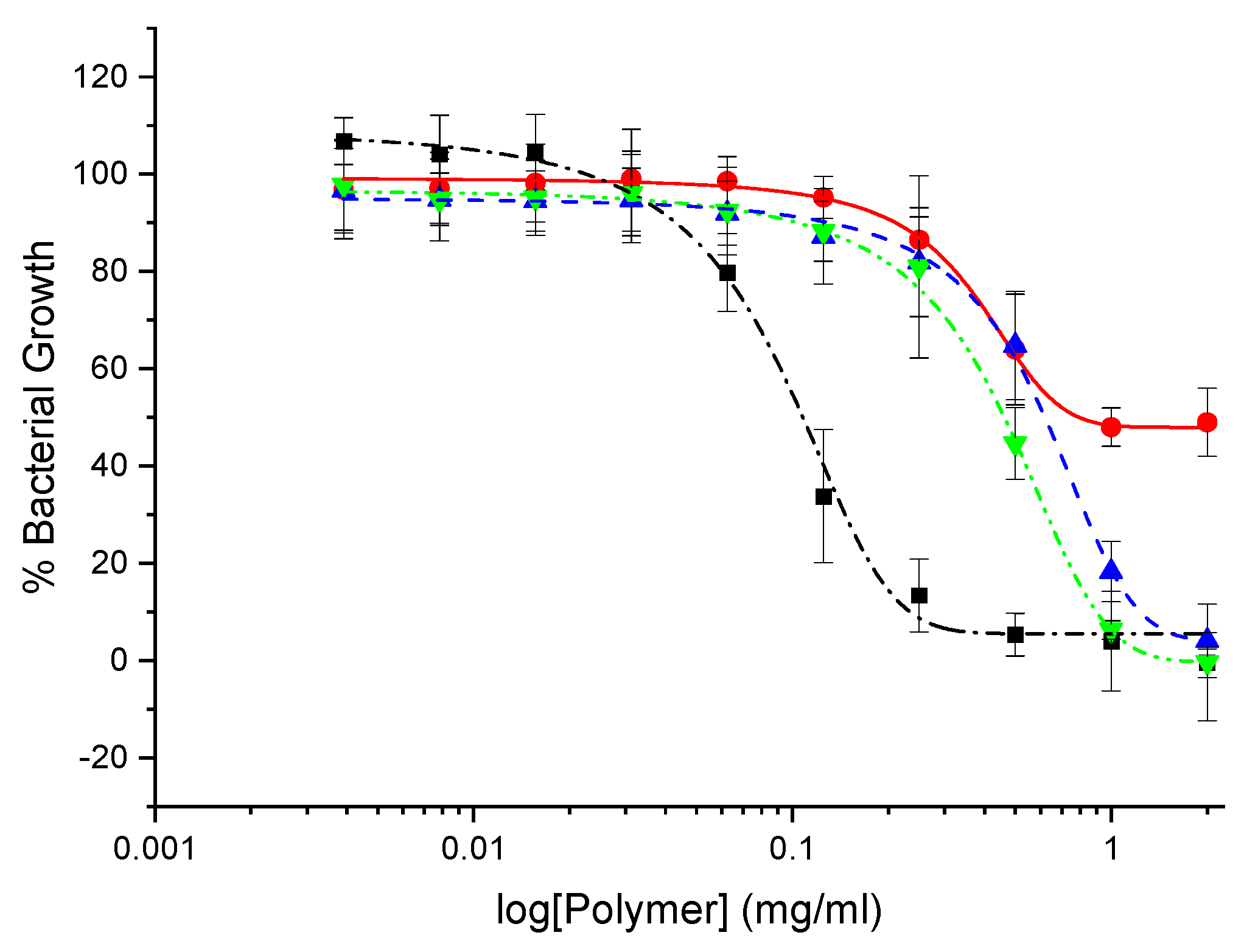

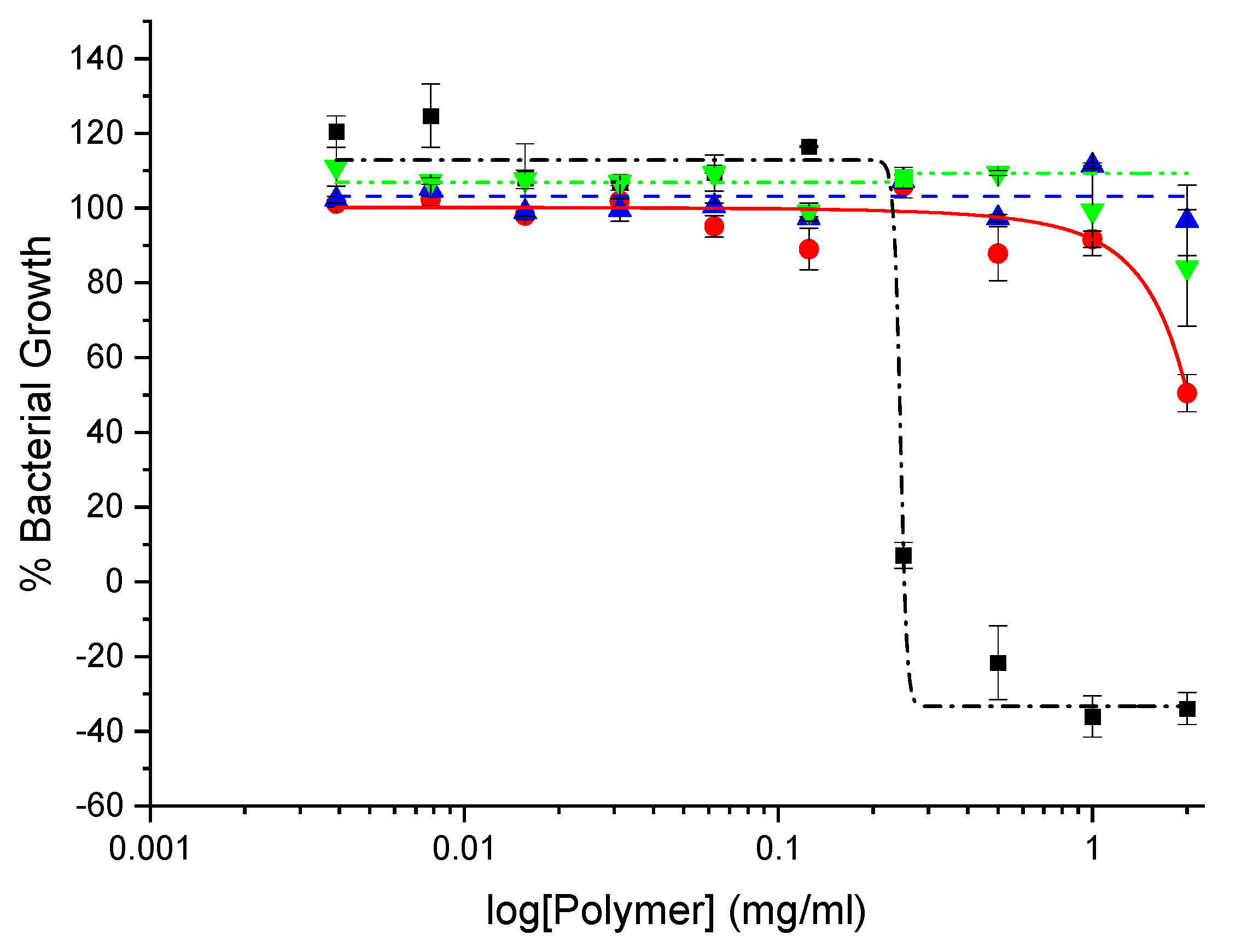

Supplementary Information, Figure S1). In the case of all four compounds, however, 2.5 mg/ml was found to have no-to-little effect on HDF viability. Equipped with this information antibacterial assays of the GCPs were conducted at concentrations below 2.5 mg/ml for therapeutic relevance.The antimicrobial activity of GCP’s against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus was determined using microtiter dilution methods. For each graft copolymer and GLU-term-p(Lys), the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined as the lowest concentration of polymer to inhibit 90% of bacteria after overnight incubation. Reductions in the growth of E. coli and S. aureus vs polymer concentration are shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, respectively, and represent the average of at least 12 trials. MIC values were quantified using a nonlinear regression method adapted from Lambert et al. [

37] and reported in

Table 2.

The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined using alamarBlue cell viability reagent. When added to bacteria, alamarBlue is modified by the reducing environment of viable cells and turns red. Wells with the lowest polymer concentration which do not change color correspond to the MBC. The MBC was also confirmed by subculturing wells with the lowest concentration of polymer that inhibited growth onto agar plates. Plates that did not show bacteria growth after overnight incubation corresponds to the MBC (

Figure 12). Further details of the antimicrobial assay procedure are given in the material and methods section.

Our results show that all the polymers can inhibit in vitro growth of E. coli but are largely inactive against S. aureus (

Table 2). At the highest concentrations, CHI-graft-poly(L-lysine) was observed to reduce E. coli growth by 50% (

Figure 11). Despite possessing hydrophobic content from the chitosan backbone, CHI-graft-poly(L-lysine) probably lacked sufficient hydrophobicity to efficiently compromise membrane integrity. CHI-graft-poly(Leu-block-Lys) and CHI-graft-poly(Lys-co-Leu), on the other hand, showed a nearly complete reduction in bacteria growth at similar concentrations. CHI-g-poly(Lys-co-Leu) was found to be twice as potent as CHI-g-poly(Leu-block-Lys) despite having similar amino acid composition. Though the overall activity was similar, differences are consistent with the hypothesis that block copolymer architectures may facilitate membrane permeabilization compared to homogeneous copolymers. However, further study with greater contrast between block and copolymer composition is needed. Despite these promising results, the GCPs are inactive against S. aureus (

Figure 12). This is likely due to the presence of a thick peptidoglycan layer on the outer membrane of gram-positive bacteria which can prevent the diffusion of large molecules.

GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine) effectively inhibited in vitro growth of E. coli and S. aureus at concentrations well below the graft copolymers MIC (

Table 2). Similar end-tethered oligo-Lysine structures synthesized by Singla et al. [

38], exhibit comparable antimicrobial activity and were found to induce membrane damage in the tested microbes. Given GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine) biocompatibility and activity further optimization of such scaffolds could prove to be effective antimicrobial agents. It is important to note that differences in activity between GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine) and the graft copolymers may be exaggerated from expressing the MIC in terms of mg/ml rather than µM. Graft copolymers have a substantially larger molecular weight which equates to fewer molecules per gram compared to GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine).

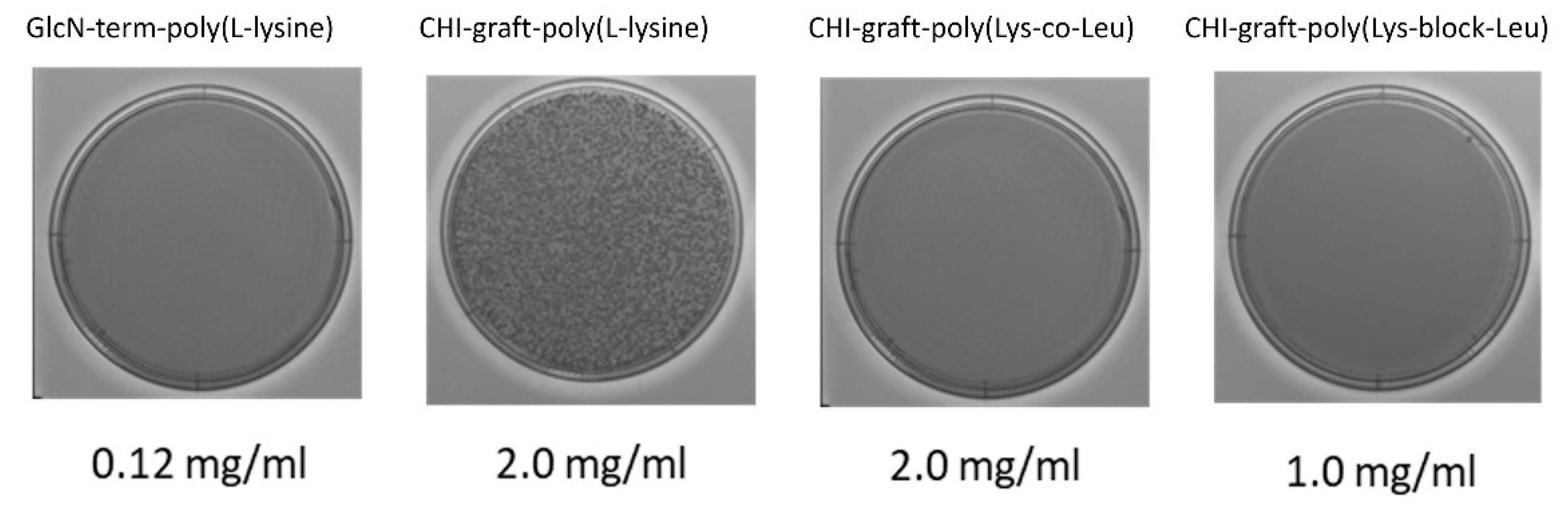

MBC was evaluated by subculturing the broth dilution of the MIC test. Wells above and below the respective MIC were subcultured onto agar plates and incubated for 24 hr. As seen in

Figure 14, plates inoculated with GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine), CHI-graft-poly(Lys-co-Leu), and CHI-graft-poly(Lys-block-Leu) at the respective MIC concentration did not proliferate. However, CHI-graft-poly(L-lysine) showed growth at 2.0 mg/ml which agrees with MIC data.

Figure 13.

MBC Plates. E. coli cultures with the lowest concentration of graft copolymer that exhibited no change in growth were subcultured to determine minimum bactericidal concentrations. Each image displays bacteria growth on Mueller-Hinton agar plates after 24 hrs incubation. Note 2.0 mg/ml was the highest concentration tested and is below the MIC of CHI-graft-poly(L-lys).

Figure 13.

MBC Plates. E. coli cultures with the lowest concentration of graft copolymer that exhibited no change in growth were subcultured to determine minimum bactericidal concentrations. Each image displays bacteria growth on Mueller-Hinton agar plates after 24 hrs incubation. Note 2.0 mg/ml was the highest concentration tested and is below the MIC of CHI-graft-poly(L-lys).

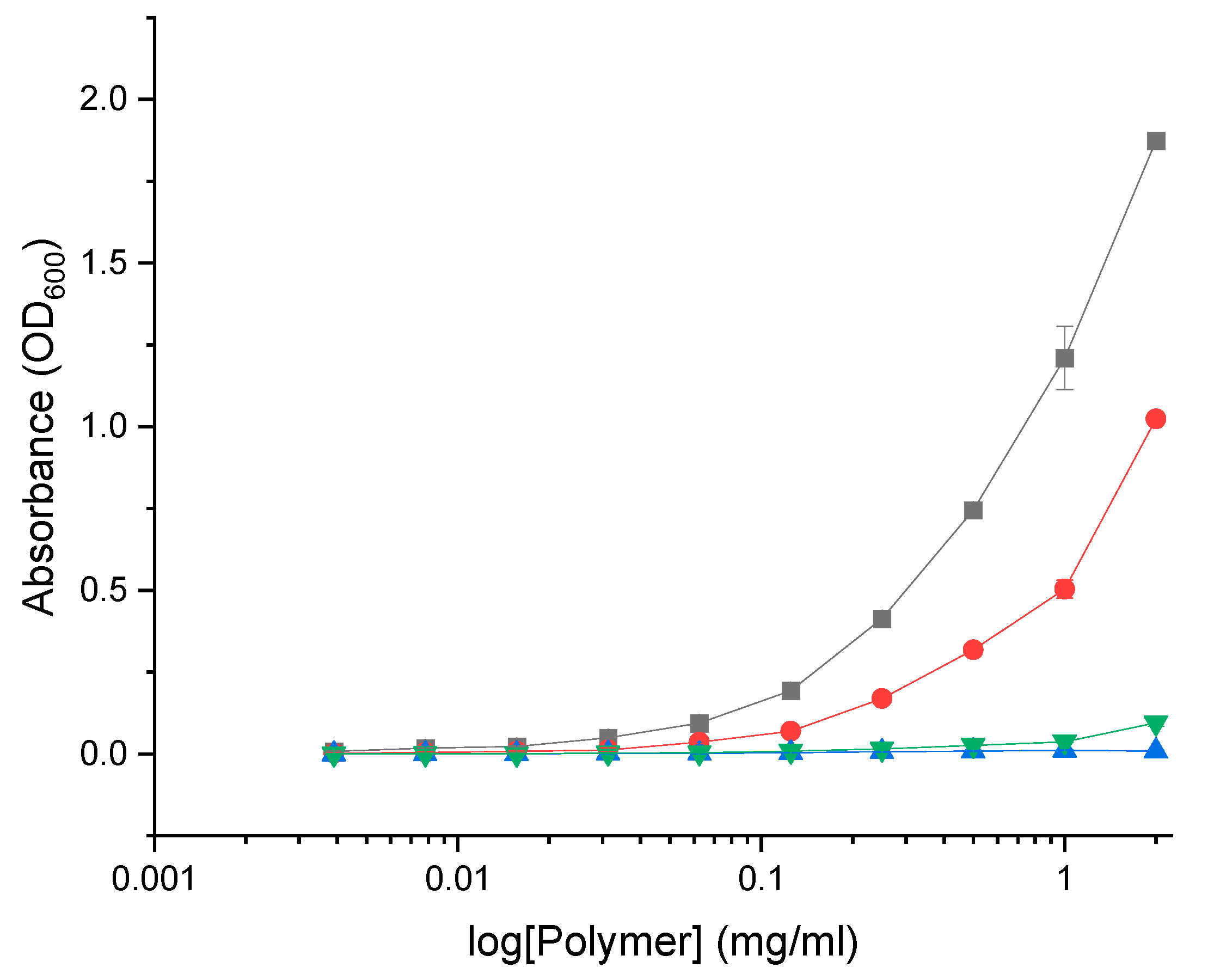

Another factor potentially influencing the antimicrobial activity of GCPs is the formation of aggregates such as micelles. Amphiphilic polymers form micelles in aqueous solution whereby the polar region faces the outside surface, and the nonpolar region forms the core. In this state the antimicrobial activity of GCPs may be substantially affected. Additionally, the formation of micelles corresponds to changes in optical properties such as light scattering which may impact absorbance measurements in the MIC assay. In order to determine if the GCPs form micelles at concentration relevant to the MIC the optical absorbance was evaluated over increasing concentrations of polymer in MH media (

Figure 13). Both GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine) and CHI-graft-poly(L-lysine) demonstrated non-linear scattering which indicate the formation of micelles. CHI-g-p(Lys-co-Leu) and CHI-g-p(Leu-block-Lys) on the other hand did not exhibit a change in slope over relevant concentrations. This may explain why GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine) effectively inhibited in vitro growth of E. coli and S. aureus at concentrations well below the graft copolymers MIC.

Figure 14.

Absorbance of the graft copolymers at varying concentration in MH media at 600nm: GlcN-term-poly(lysine) (black squares), CHI-graft-poly(lysine) (red circles), CHI-graft-poly(lysine-co-leucine) (blue triangles), and CHI-graft-poly(leucine-block-lysine) (green triangles) for 24hrs. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, n=4.

Figure 14.

Absorbance of the graft copolymers at varying concentration in MH media at 600nm: GlcN-term-poly(lysine) (black squares), CHI-graft-poly(lysine) (red circles), CHI-graft-poly(lysine-co-leucine) (blue triangles), and CHI-graft-poly(leucine-block-lysine) (green triangles) for 24hrs. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, n=4.

Biofilms consist of an assembly of microorganisms embedded in a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) containing polysaccharides, extracellular DNA, proteins, and lipids [

39]. The EPS layer acts as a sort of a “glue” adhering the cells to one another and shields bacteria from harsh environmental conditions. In this protected scaffold biofilm-associated cells grow significantly slower and enter a non-replicating dormant state. As a result, biofilm-embedded bacteria exhibit strong antibiotic resistance and typically require 1000-fold higher concentrations to be effective [

40].

Biofilms are of clinical relevance due to their ability to colonize medical devices such as catheters and implants. The National Institutes of Health in the USA reported that approximately 80% of chronic infections in humans are biofilm-related [

41]. Due to the unique characteristics of biofilm and its role in human diseases, an urgent need exists for effective treatments.

AMP-mediated strategies for biofilm eradication are an attractive approach that has gained attention in recent years. Compared to traditional small-molecule antibiotics AMPs offer fast-killing kinetics, a high potential to act on slow-growing or non-growing bacteria, and the ability to synergize with antibiotics [

42]. Antimicrobial peptides and polymers have been reported to act at several stages of biofilm development and with different mechanisms of action.

Depending on the stage of development the AMP targets it may inhibit the formation or eradicate established biofilms. AMPs that follow an inhibitory pathway typically do so by; (1) altering the adhesion of microbial cells by binding their surface or the surface of the substrate, [

43] (2) disrupting signaling molecules that regulate biofilm formation [

44], or (3) killing early colonizer cells to prevent biofilm maturation [

45].

AMPs that target established biofilms follow mechanisms that either kill microbial cells or reduce biofilm mass. Killing pathways typically do so by penetrating the EPS matrix and inhibiting cell division or, disrupting the cytoplasmic membrane of microbial cells directly [

46]. AMPs that eradicate biofilms reduce film mass by solubilizing components of the EPS matrix via its amphipathic and cationic structure [

47].

We studied the potential of cationic peptidopolysaccharide graft copolymers to act as an anti-biofilm agent. In addition to antimicrobial activity, the synthesized GCPs readily form micelles that may support the solvation of key components in the ECM matrix. Similar materials have been found to act as compatibilizers, stabilizing the solvation of immiscible blends [

48, 49]. Additionally, the cationic and hydrophobic motifs may promote favorable interaction with the outer membrane of bacteria and neutralize surface charges. Finally, the GCPs may adsorb onto biofouling surfaces before colonization or directly on the biofilm and prevent further development.

Herein, we evaluated the anti-biofilm activity of the graft copolymers series against Agrobacterium tumefaciens (A. tumefaciens ). A. tumefaciens was selected as a model bacterium as it readily forms biofilms, is generally safe to humans and has well-established assays and protocols for evaluation.

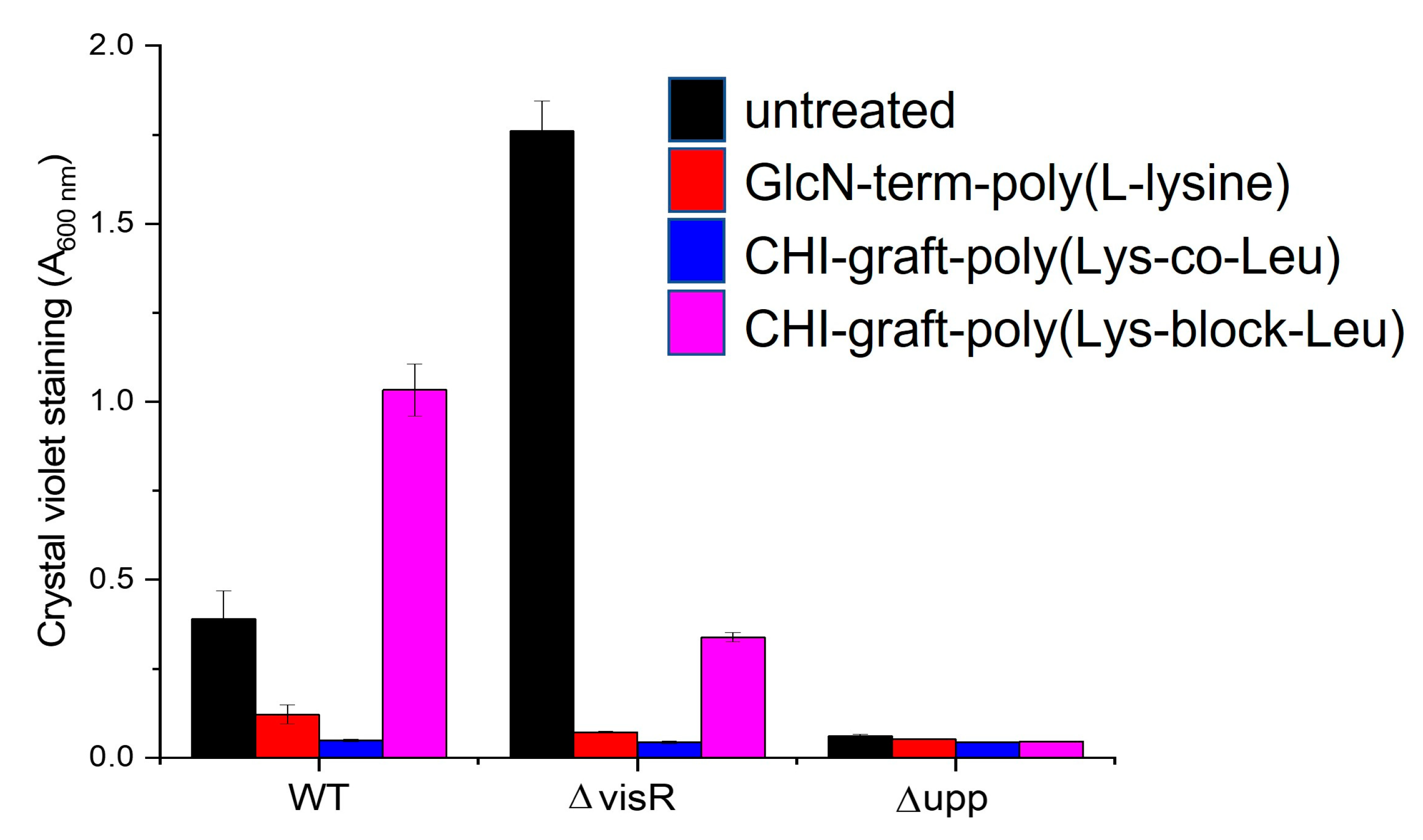

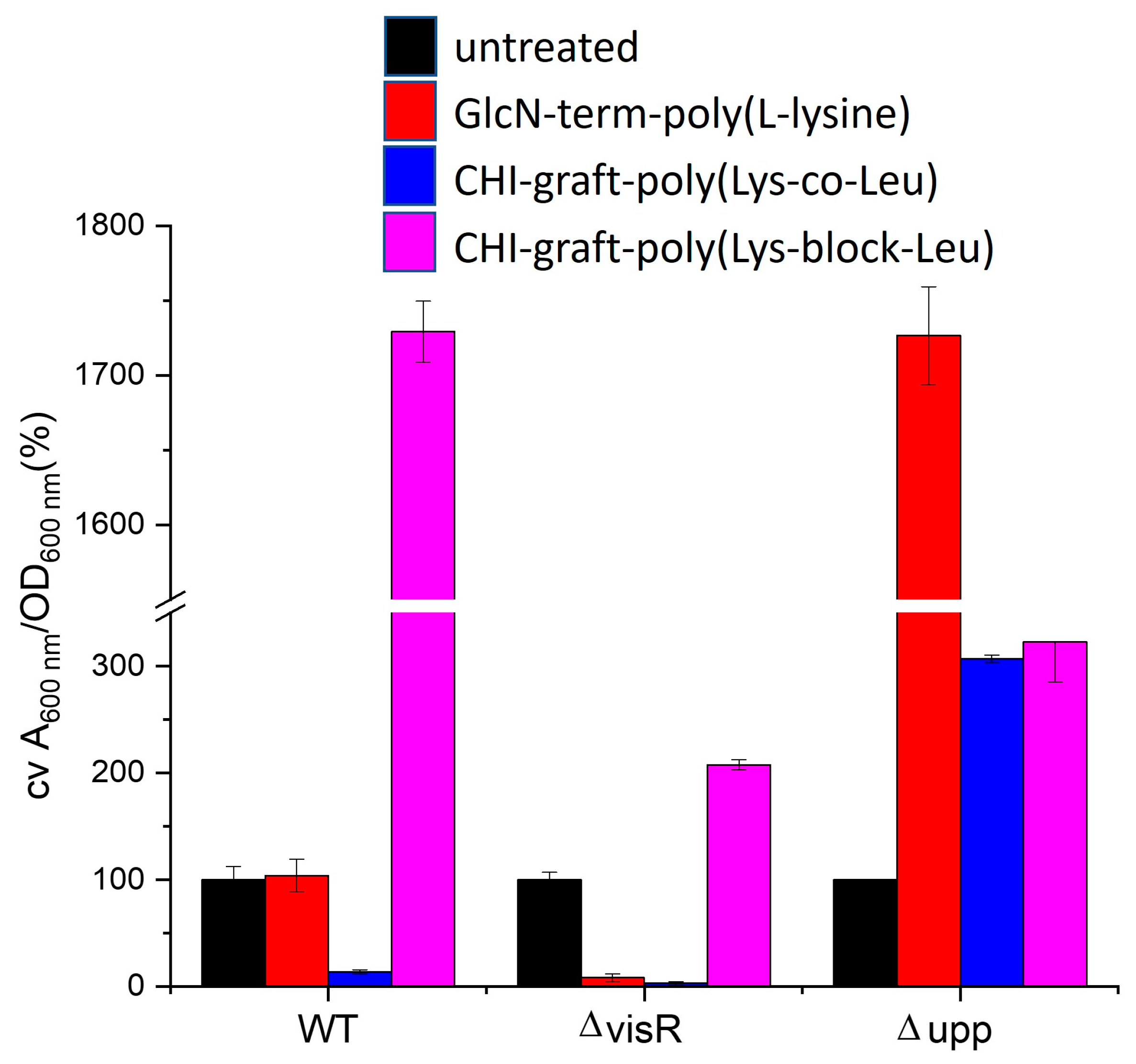

The anti-biofilm activity of the GCPs was evaluated by inoculating wild type A. tumefaciens and the mutants ΔvisR and Δupp before colonizing the substrate surface. The deletion mutants ΔvisR and Δupp were included as controls and exhibit increased and decreased biofilm production respectively. Changes in biofilm mass were quantified using a static biofilm coverslip assay optimized for A. tumefaciens [

18, 50]. Briefly, the agrobacterium strains were cultured overnight and diluted to an optical density of 0.05 A.U. in 35mm wells. The cultures were inoculated to a concentration of 0.25 mg/ml with the respective GCP and a polyvinyl chloride coverslip was suspended in the solution. After 24hrs incubation planktonic bacteria growth was quantified by spectrophotometry and the colonized coverslips were stained with crystal violet solution. Images of the stained biofilms were collected for qualitative analysis. Finally, crystal violet was solubilized from the films and the absorbance was measured at 600nm to estimate the relative amounts of adhered biomass.

Adherent biofilm mass after treatment with the respective graft copolymers is shown in

Figure 15. When compared to untreated, both GlcN-term-poly(L-lysine) and CHI-graft-poly(Lys-co-Leu) showed significant reductions in the adherent mass of WT and ΔvisR strains. CHI-graft-poly(Leu-block-Lys) on the other hand, increased biofilm mass of wild type while decreasing ΔvisR. No changes were observed in the biofilms of the Δupp strain for any of the graft copolymers. Given that Δupp lacks the exopolysaccharide adhesions that are critical for surface attachment, exposure to the graft copolymers could only result in increased adherent mass.

Differences in the activity of CHI-graft-poly(Leu-block-Lys) when exposed to wild type or ΔvisR are unexpected. However, antimicrobial peptides are known to target a wide range of intracellular components, including, DNA, RNA, and proteins [

51]. Binding to any of these sites is complex as it can lead to opposing trends in biofilm regulation. Subtle changes in gene expression or the intracellular composition of ΔvisR may facilitate graft copolymer binding and alter biofilm expression.

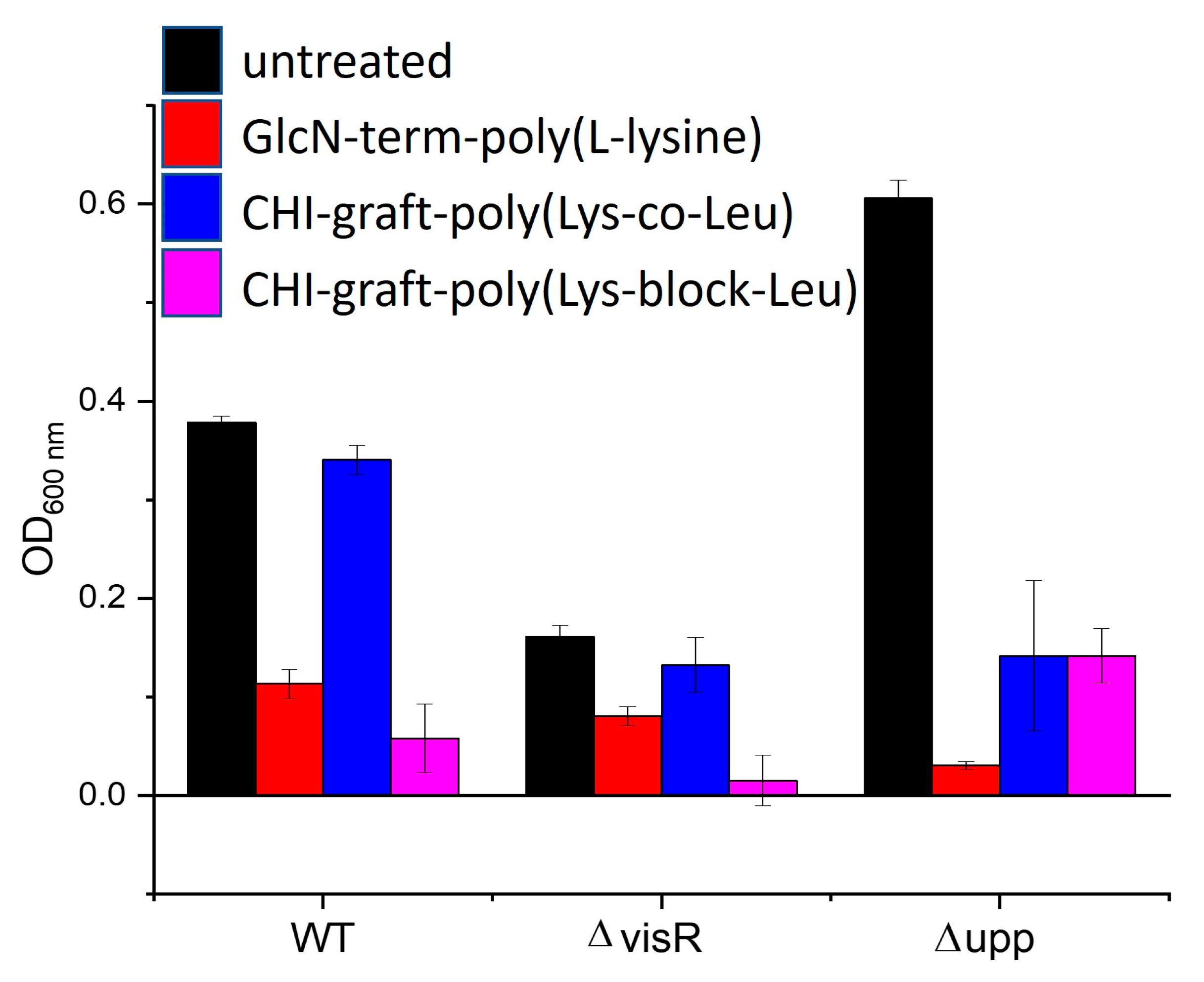

The direct antimicrobial effects of the graft copolymers on planktonic A. tumefaciens were also evaluated. Optical density measurements of the biofilm inoculum were taken before and after film formation (

Figure 16). Reductions of 50% or greater were observed for all graft polymers and strains of bacteria. This implies that direct antimicrobial activity of the GCPs in solution may contribute to biofilm losses.

The extent to which reductions in biofilm mass correspond to reductions in planktonic bacteria was evaluated by normalizing the ratio of biofilm mass to the number of planktonic bacteria (

Figure 17). Values greater than 100% correspond to elevated biofilm formation, while values less than 100% indicate the biofilm is disproportionately reduced relative to viable planktonic bacteria.

Wild type A. tumefaciens treated with glucosamine-terminated poly(lysine) exhibited reductions in biofilm mass and planktonic bacteria that are in proportion to untreated. This suggests the anti-biofilm activity of GLU-term-p(Lys) is a result of antimicrobial action rather than selective inhibition. CHI-g-p(Lys-co-Leu) on the other hand, reduced adherent mass without killing planktonic bacteria. Finally, CHI-g-p(Leu-block-Lys) was found to increase adherent mass despite reducing viable bacteria. Further investigation is required to understand the mechanism of this paradoxical behavior.