Submitted:

12 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Key Features That Should Reproduce the FS MODEL

2.1. The Main Types of FSs

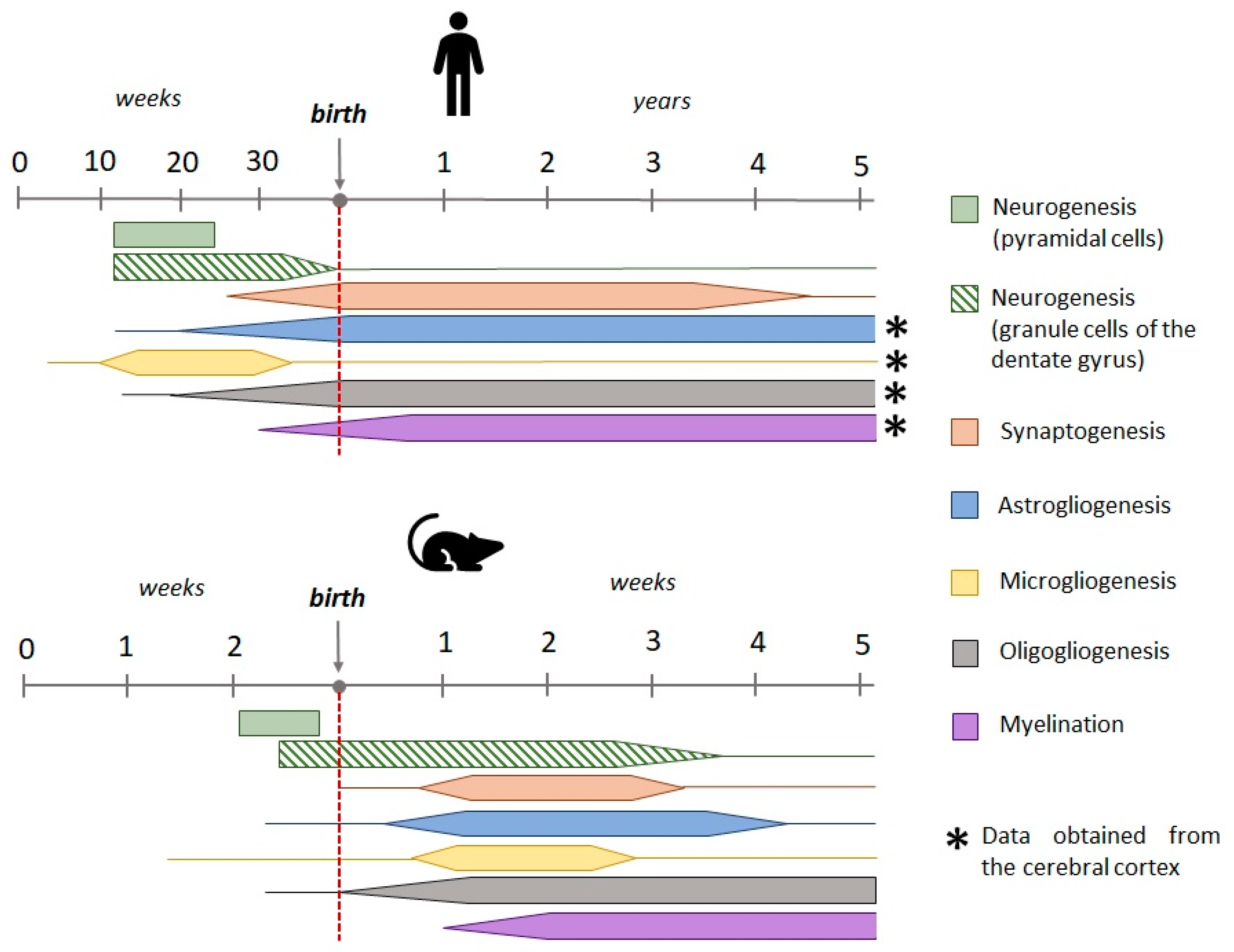

2.2. Age-Related Characteristics of Febrile Seizures

2.3. Body Temperature

2.4. The Source of the Ictal Activity in the Brain during a Febrile Seizure

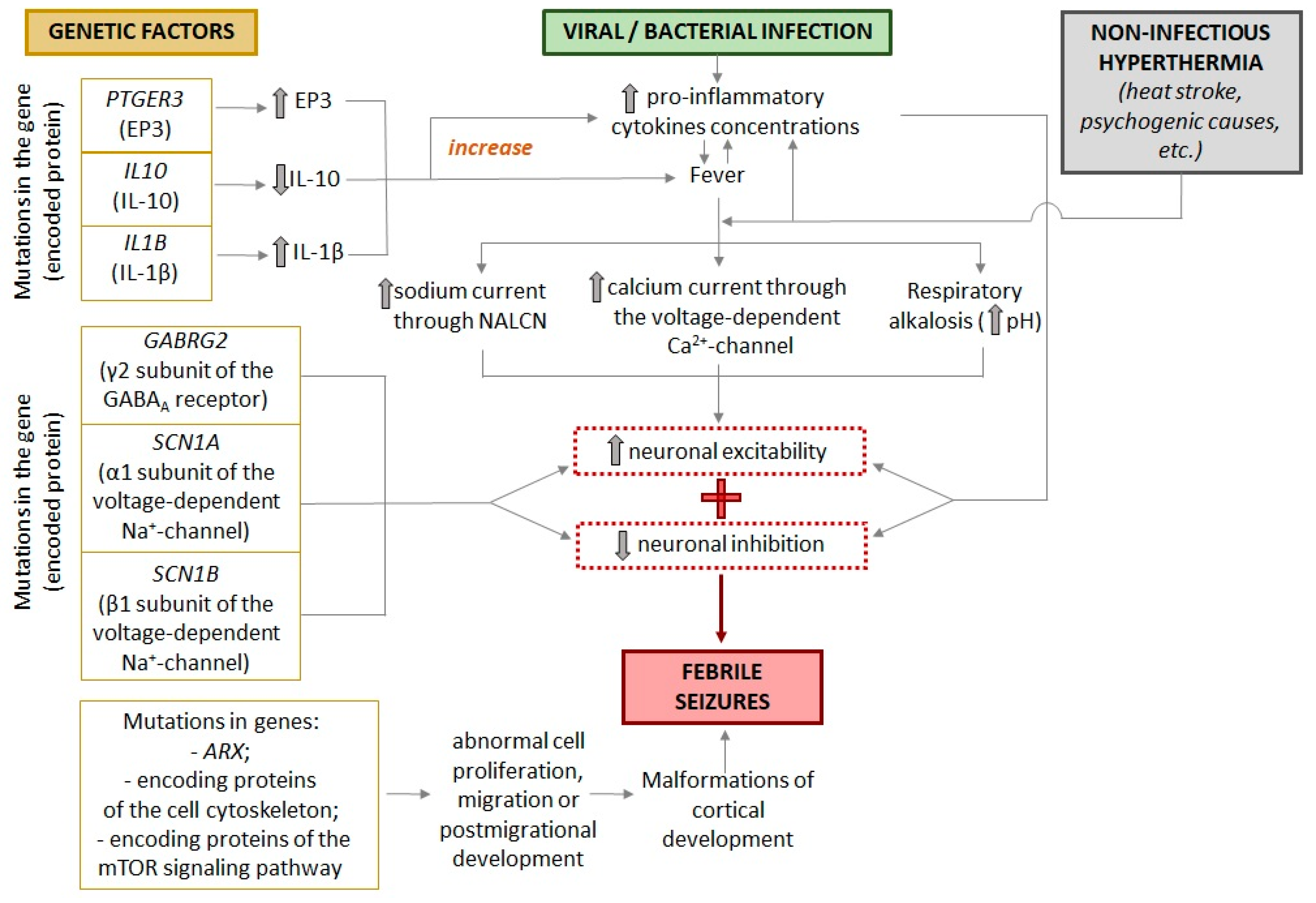

3. Factors That Influence the Course of Febrile Seizures

3.1. Genetic Background

3.2. Malformations of Cortical Development

3.3. Sex-Related Characteristics of Febrile Seizures

4. Models of Febrile Seizures Ex Vivo

5. Models of Febrile Seizures In Vivo

5.1. Species Used to Model FSs

5.2. Hyperthermia-Based Model

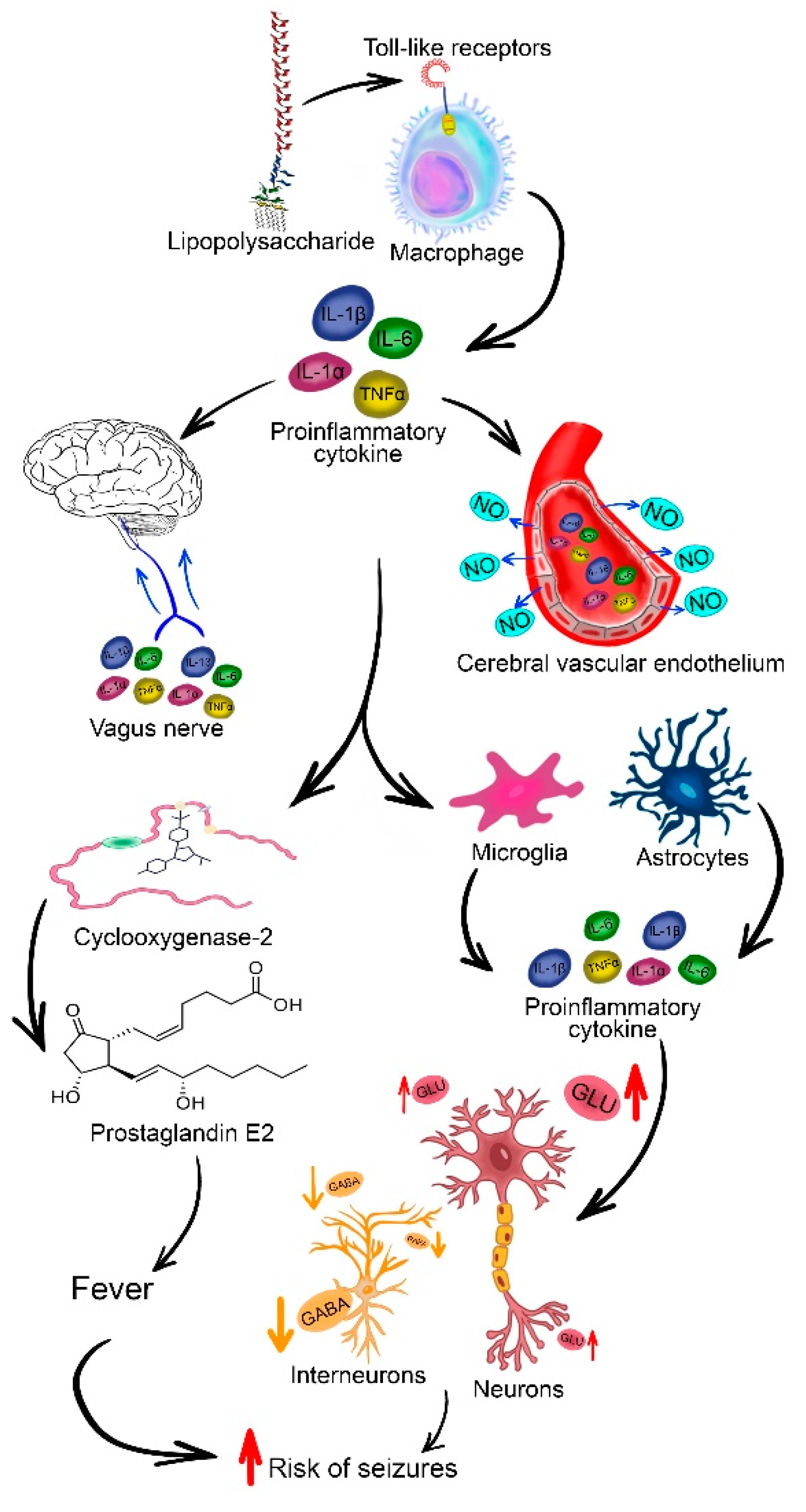

5.3. Fever Model

5.3. Combination Models of FSs

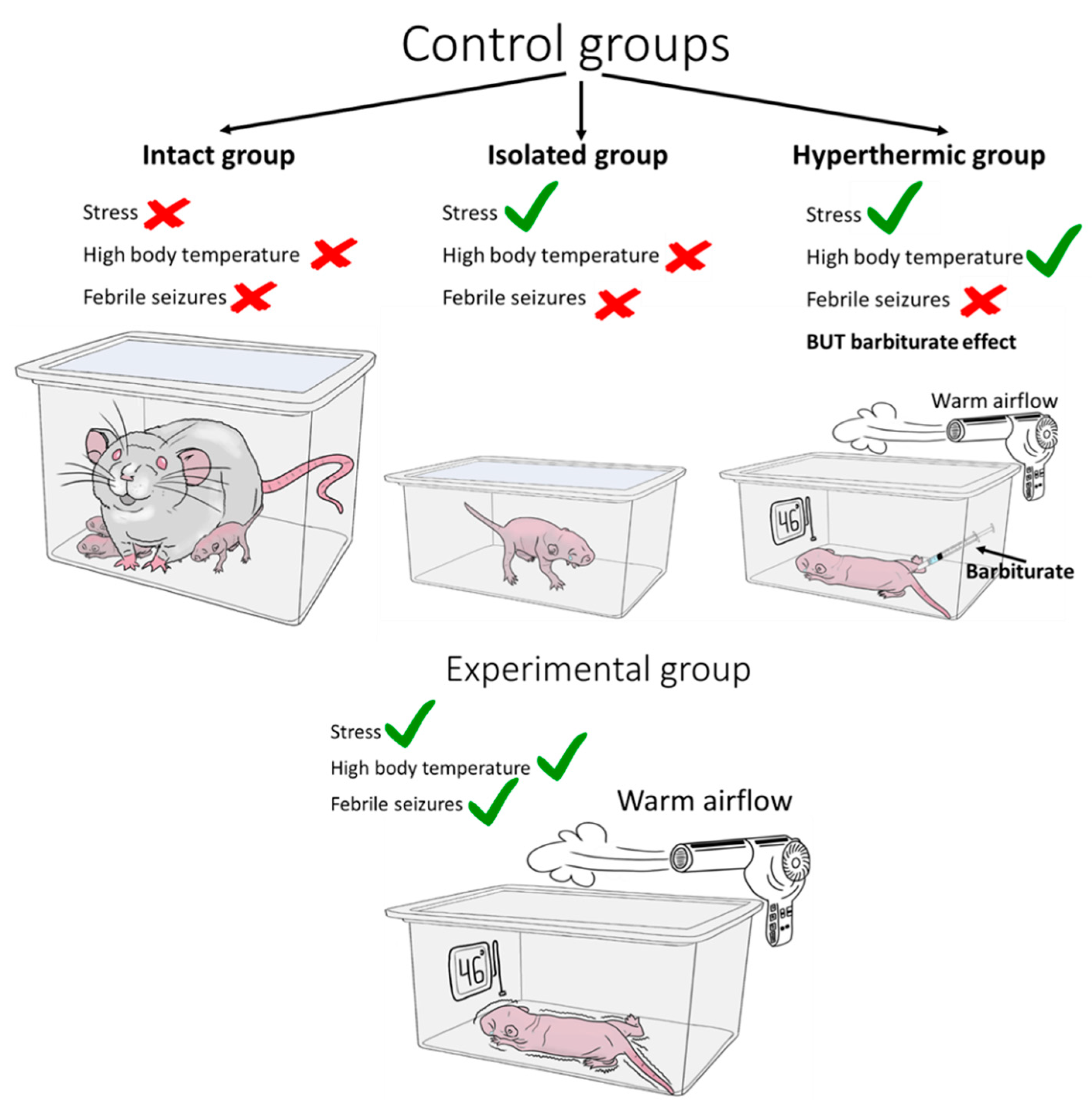

5.4. Required Control Groups

6. Main Results Obtained in Models of Febrile Seizures

6.1. Morphologic Changes in Neurons

6.2. Morphologic Changes in Glial Cells

6.3. Changes in Neuronal Properties and Synaptic Transmission

6.4. Changes in Synaptic Plasticity

6.5. A Predisposition to Recurrent Seizures and Epilepsy

6.6. Behavioural Disorders after Febrile Seizures

7. Conclusions. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leung, A.K.; Hon, K.L.; Leung, T.N.H. Febrile Seizures: An Overview. Drugs Context 2018, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Jung, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kwon, H.; Park, J.W.; Kwak, Y.H.; Kim, D.K.; Lee, J.H. Febrile Seizures: Are They Truly Benign? Longitudinal Analysis of Risk Factors and Future Risk of Afebrile Epileptic Seizure Based on the National Sample Cohort in South Korea, 2002–2013. Seizure 2019, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugai, K. Current Management of Febrile Seizures in Japan: An Overview. Brain Dev. 2010, 32, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verity, C.M.; Butler, N.R.; Golding, J. Febrile Convulsions in a National Cohort Followed up from Birth. I--Prevalence and Recurrence in the First Five Years of Life. BMJ 1985, 290, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civan, A.B.; Ekici, A.; Havali, C.; Kiliç, N.; Bostanci, M. Evaluation of the Risk Factors for Recurrence and the Development of Epilepsy in Patients with Febrile Seizure. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2022, 80, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.B.; Ellenberg, J.H. Predictors of Epilepsy in Children Who Have Experienced Febrile Seizures. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976, 295, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Yousefichaijan, P.; Safi Arian, S.; Ebrahimi, S.; Naziri, M. Comparison of Relation between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children with and without Simple Febrile Seizure Admitted in Arak Central Iran. Iran. J. child Neurol. 2016, 10, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dreier, J.W.; Pedersen, C.B.; Cotsapas, C.; Christensen, J. Childhood Seizures and Risk of Psychiatric Disorders in Adolescence and Early Adulthood: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Lancet. Child Adolesc. Heal. 2019, 3, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhong, C.; Wei-Wei, H. The Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Febrile Seizures and Underlying Mechanisms. Front. cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1186050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, D.; Obana, K.; Olson, J. Hyperthermia-Induced Seizures in the Rat Pup: A Model for Febrile Convulsions in Children. Science 1981, 213, 1034–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjeresen, D.L.; Guy, A.W.; Petracca, F.M.; Diaz, J. A Microwave-hyperthermia Model of Febrile Convulsions. Bioelectromagnetics 1983, 4, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baram, T.Z.; Gerth, A.; Schultz, L. Febrile Seizures: An Appropriate-Aged Model Suitable for Long-Term Studies. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1997, 98, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Duong, T.M.; de Lanerolle, N.C. The Neuropathology of Hyperthermic Seizures in the Rat. Epilepsia 1999, 40, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heida, J.G.; Boissé, L.; Pittman, Q.J. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Febrile Convulsions in the Rat: Short-Term Sequelae. Epilepsia 2004, 45, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eun, B.L.; Abraham, J.; Mlsna, L.; Kim, M.J.; Koh, S. Lipopolysaccharide Potentiates Hyperthermia-Induced Seizures. Brain Behav. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gassen, K.L.I.; Hessel, E.V.S.; Ramakers, G.M.J.; Notenboom, R.G.E.; Wolterink-Donselaar, I.G.; Brakkee, J.H.; Godschalk, T.C.; Qiao, X.; Spruijt, B.M.; van Nieuwenhuizen, O.; et al. Characterization of Febrile Seizures and Febrile Seizure Susceptibility in Mouse Inbred Strains. Genes. Brain. Behav. 2008, 7, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R.F.; Hortopan, G.A.; Gillespie, A.; Baraban, S.C. A Novel Zebrafish Model of Hyperthermia-Induced Seizures Reveals a Role for TRPV4 Channels and NMDA-Type Glutamate Receptors. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 237, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Gilligan, J.; Staber, C.; Schutte, R.J.; Nguyen, V.; O’Dowd, D.K.; Reenan, R. A Knock-in Model of Human Epilepsy in Drosophila Reveals a Novel Cellular Mechanism Associated with Heat-Induced Seizure. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 14145–14155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, R.A.; Dubé, C.; Baram, T.Z. Febrile Seizures and Mechanisms of Epileptogenesis: Insights from an Animal Model. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2004, 548, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbing, J.; Sands, J. Quantitative Growth and Development of Human Brain. Arch. Dis. Child. 1973, 48, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, A. , Keydar, I. K., & Epstein, H.T. Rodent Brain Growth Stages: An Analytical Review. Neonatology 1977, 6, 166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Avishai-Eliner, S.; Brunson, K.L.; Sandman, C.A.; Baram, T.Z. Stressed-out, or in (Utero)? Trends Neurosci. 2002, 25, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herschkowitz, N.; Kagan, J.; Zilles, K. Neurobiological Bases of Behavioral Development in the First Year. Neuropediatrics 1997, 28, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, S.A. Development of the Hippocampal Region in the Rat I. Neurogenesis Examined with 3 H-thymidine Autoradiography. J. Comp. Neurol. 1980, 190, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menassa, D.A.; Gomez-Nicola, D. Microglial Dynamics During Human Brain Development. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esiri, M.M.; al Izzi, M.S.; Reading, M.C. Macrophages, Microglial Cells, and HLA-DR Antigens in Fetal and Infant Brain. J. Clin. Pathol. 1991, 44, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermitzakis, I.; Manthou, M.E.; Meditskou, S.; Tremblay, M.-È.; Petratos, S.; Zoupi, L.; Boziki, M.; Kesidou, E.; Simeonidou, C.; Theotokis, P. Origin and Emergence of Microglia in the CNS-An Interesting (Hi)Story of an Eccentric Cell. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 2609–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Mlsna, L.M.; Yoon, S.; Le, B.; Yu, S.; Xu, D.; Koh, S. A Postnatal Peak in Microglial Development in the Mouse Hippocampus Is Correlated with Heightened Sensitivity to Seizure Triggers. Brain Behav. 2015, 5, e00403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; He, L.; Xiang, W.; Ai, W.-M.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.-S.; Pan, A.; Luo, X.-G.; Li, Z.; Yan, X.-X. Somal and Dendritic Development of Human CA3 Pyramidal Neurons from Midgestation to Middle Childhood: A Quantitative Golgi Study. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken). 2013, 296, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degl’Innocenti, E.; Dell’Anno, M.T. Human and Mouse Cortical Astrocytes: A Comparative View from Development to Morphological and Functional Characterization. Front. Neuroanat. 2023, 17, 1130729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivi, E.; Di Benedetto, B. Brain Stars Take the Lead during Critical Periods of Early Postnatal Brain Development: Relevance of Astrocytes in Health and Mental Disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakovcevski, I.; Filipovic, R.; Mo, Z.; Rakic, S.; Zecevic, N. Oligodendrocyte Development and the Onset of Myelination in the Human Fetal Brain. Front. Neuroanat. 2009, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, A.; Shimizu, T.; Sherafat, A.; Richardson, W.D. Life-Long Oligodendrocyte Development and Plasticity. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 116, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kracht, L.; Borggrewe, M.; Eskandar, S.; Brouwer, N.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Laman, J.D.; Scherjon, S.A.; Prins, J.R.; Kooistra, S.M.; Eggen, B.J.L. Human Fetal Microglia Acquire Homeostatic Immune-Sensing Properties Early in Development. Science 2020, 369, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjeresen, D.L.; Diaz, J. Ontogeny of Susceptibility to Experimental Febrile Seizures in Rats. Dev. Psychobiol. 1988, 21, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Nagao, H.; Sano, N.; Takahashi, M.; Matsuda, H. Hyperthermia-Induced Seizures with a Servo System: Neurophysiological Roles of Age, Temperature Elevation Rate and Regional GABA Content in the Rat. Brain Dev. 1990, 12, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundgren-Andersson, A.K.; Östlund, P.; Bartfai, T. Simultaneous Measurement of Brain and Core Temperature in the Rat during Fever, Hyperthermia, Hypothermia and Sleep. Neuroimmunomodulation 1998, 5, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, R.C. Hippocampal Abnormalities after Prolonged Febrile Convulsion: A Longitudinal MRI Study. Brain 2003, 126, 2551–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, D.K.; Demyer, W.E.; Edwards-Brown, M.; Sanders, S.; Garg, B. From Swelling to Sclerosis: Acute Change in Mesial Hippocampus after Prolonged Febrile Seizure. Seizure 2003, 12, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.-J.; Hsieh, K.L.-C.; Lin, Y.-K.; Tsai, M.-L.; Wong, T.-T.; Chang, H. Febrile Seizures Reduce Hippocampal Subfield Volumes but Not Cortical Thickness in Children with Focal Onset Seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2021, 179, 106848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamelin, S.; Vercueil, L. A Simple Febrile Seizure with Focal Onset. Epileptic Disord. 2014, 16, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, B.; Gindner, D. Febrile Seizures Are a Syndrome of Secondarily Generalized Hippocampal Epilepsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, 1151–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, A.T.; Shinnar, S.; Shapiro, E.D.; Salomon, M.E.; Crain, E.F.; Hauser, W.A. Risk Factors for a First Febrile Seizure: A Matched Case-Control Study. Epilepsia 1995, 36, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchmann, S.; Hauck, S.; Henning, S.; Grüters-Kieslich, A.; Vanhatalo, S.; Schmitz, D.; Kaila, K. Respiratory Alkalosis in Children with Febrile Seizures. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 1949–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchmann, S.; Schmitz, D.; Rivera, C.; Vanhatalo, S.; Salmen, B.; Mackie, K.; Sipilä, S.T.; Voipio, J.; Kaila, K. Experimental Febrile Seizures Are Precipitated by a Hyperthermia-Induced Respiratory Alkalosis. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrino, M.; Somjen, G.G. Concentration of Carbon Dioxide, Interstitial PH and Synaptic Transmission in Hippocampal Formation of the Rat. J. Physiol. 1988, 396, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzicki, D.; Yau, H.J.; Pollema-Mays, S.L.; Mlsna, L.; Cho, K.; Koh, S.; Martina, M. Temperature-Sensitive Cav1.2 Calcium Channels Support Intrinsic Firing of Pyramidal Neurons and Provide a Target for the Treatment of Febrile Seizures. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 9920–9931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemann, A.E.; Schnizler, M.K.; Albert, G.W.; Severson, M.A.; Howard, M.A.; Welsh, M.J.; Wemmie, J.A. Seizure Termination by Acidosis Depends on ASIC1a. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviani, B.; Bartesaghi, S.; Gardoni, F.; Vezzani, A.; Behrens, M.M.; Bartfai, T.; Binaglia, M.; Corsini, E.; Di Luca, M.; Galli, C.L.; et al. Interleukin-1β Enhances NMDA Receptor-Mediated Intracellular Calcium Increase through Activation of the Src Family of Kinases. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 8692–8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheng, Q.; Malik, S.; Yang, J. Interleukin-1beta Inhibits Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Type A (GABA(A)) Receptor Current in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 292, 497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Skotte, L.; Fadista, J.; Bybjerg-Grauholm, J.; Appadurai, V.; Hildebrand, M.S.; Hansen, T.F.; Banasik, K.; Grove, J.; Albiñana, C.; Geller, F.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Febrile Seizures Implicates Fever Response and Neuronal Excitability Genes. Brain 2022, 145, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virta, M.; Hurme, M.; Helminen, M. Increased Frequency of Interleukin-1beta (-511) Allele 2 in Febrile Seizures. Pediatr. Neurol. 2002, 26, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.C.; Shen, Y.; Hu, N.; Shen, W.; Narayanan, V.; Ramsey, K.; He, W.; Zou, L.; Macdonald, R.L. GABRG2 Variants Associated with Febrile Seizures. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.H.; Wang, D.W.; Singh, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; George, A.L.; Phillips, H.A.; Saar, K.; Reis, A.; W. johnson, E.; Sutherland, G.R.; et al. Febrile Seizures and Generalized Epilepsy Associated with a Mutation in the Na+-Channel Β1 Subunit Gene SCN1B. Nat. Genet. 1998, 19, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audenaert, D.; Claes, L.; Ceulemans, B.; Löfgren, A.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; De Jonghe, P. A Deletion in SCN1B Is Associated with Febrile Seizures and Early-Onset Absence Epilepsy. Neurology 2003, 61, 854–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.-P.; Shi, Y.-W.; Long, Y.-S.; Zeng, Y.; Li, T.; Yu, M.-J.; Su, T.; Deng, P.; Lei, Z.-G.; Xu, S.-J.; et al. Partial Epilepsy with Antecedent Febrile Seizures and Seizure Aggravation by Antiepileptic Drugs: Associated with Loss of Function of Na(v) 1.1. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 1669–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkovich, A.J.; Dobyns, W.B.; Guerrini, R. Malformations of Cortical Development and Epilepsy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a022392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rantala, H.; Uhari, M.; Hietala, J. Factors Triggering the First Febrile Seizure. Acta Paediatr. 1995, 84, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, K.E.; Dooley, J.M.; Wood, E.P.; Bethune, P. Is Temperature Regulation Different in Children Susceptible to Febrile Seizures? Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 36, 192–195. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S.S.; Repasky, E.A.; Fisher, D.T. Fever and the Thermal Regulation of Immunity: The Immune System Feels the Heat. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J. Endogenous Antipyretics. Clin. Chim. Acta 2006, 371, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Morshedy, S.; Elsaadany, H.F.; Ibrahim, H.E.; Sherif, A.M.; Farghaly, M.A.A.; Allah, M.A.N.; Abouzeid, H.; Elashkar, S.S.A.; Hamed, M.E.; Fathy, M.M.; et al. Interleukin-1β and Interleukin-1receptor Antagonist Polymorphisms in Egyptian Children with Febrile Seizures. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017, 96, e6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyomina, A. V.; Zubareva, O.E.; Smolensky, I. V.; Vasilev, D.S.; Zakharova, M. V.; Kovalenko, A.A.; Schwarz, A.P.; Ischenko, A.M.; Zaitsev, A. V. Anakinra Reduces Epileptogenesis, Provides Neuroprotection, and Attenuates Behavioral Impairments in Rats in the Lithium–Pilocarpine Model of Epilepsy. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santtila, S.; Savinainen, K.; Hurme, M. Presence of the IL-1RA Allele 2 (IL1RN*2) Is Associated with Enhanced IL-1beta Production in Vitro. Scand. J. Immunol. 1998, 47, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tütüncüoğlu, S.; Kütükçüler, N.; Kepe, L.; Coker, C.; Berdeli, A.; Tekgül, H. Proinflammatory Cytokines, Prostaglandins and Zinc in Febrile Convulsions. Pediatr. Int. 2001, 43, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Niu, X.; Cheng, M.; Zeng, Q.; Deng, J.; Tian, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Shi, W.; Wu, W.; et al. Phenotypic Spectrum and Prognosis of Epilepsy Patients With GABRG2 Variants. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Q.; MacDonald, R.L. Molecular Pathogenic Basis for GABRG2Mutations Associatedwith a Spectrum of Epilepsy Syndromes, from Generalized Absence Epilepsy to Dravet Syndrome. JAMA Neurol. 2016, 73, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essrich, C.; Lorez, M.; Benson, J.A.; Fritschy, J.M.; Lüscher, B. Postsynaptic Clustering of Major GABAA Receptor Subtypes Requires the Gamma 2 Subunit and Gephyrin. Nat. Neurosci. 1998, 1, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, K.F.; Macdonald, R.L. GABA(A) Receptor Subunit Γ2 and δ Subtypes Confer Unique Kinetic Properties on Recombinant GABA(A) Receptor Currents in Mouse Fibroblasts. J. Physiol. 1999, 514, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hernandez, C.C.; Hu, N.; Macdonald, R.L. Three Epilepsy-Associated GABRG2 Missense Mutations at the Γ+/β- Interface Disrupt GABAA Receptor Assembly and Trafficking by Similar Mechanisms but to Different Extents. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 68, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A. Dravet Syndrome: A Sodium Channel Interneuronopathy. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2018, 2, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauser, S.; Huppertz, H.-J.; Bast, T.; Strobl, K.; Pantazis, G.; Altenmueller, D.-M.; Feil, B.; Rona, S.; Kurth, C.; Rating, D.; et al. Clinical Characteristics in Focal Cortical Dysplasia: A Retrospective Evaluation in a Series of 120 Patients. Brain 2006, 129, 1907–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesdorffer, D.C.; Chan, S.; Tian, H.; Allen Hauser, W.; Dayan, P.; Leary, L.D.; Hinton, V.J. Are MRI-Detected Brain Abnormalities Associated with Febrile Seizure Type? Epilepsia 2008, 49, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luhmann, H.J. Models of Cortical Malformation--Chemical and Physical. J. Neurosci. Methods 2016, 260, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.-H.; Yum, M.-S.; Lee, M.; Kim, E.-J.; Shim, W.-H.; Ko, T.-S. A New Rat Model of Epileptic Spasms Based on Methylazoxymethanol-Induced Malformations of Cortical Development. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquiles, A.; Fiordelisio, T.; Luna-Munguia, H.; Concha, L. Altered Functional Connectivity and Network Excitability in a Model of Cortical Dysplasia. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorák, K.; Feit, J. Migration of Neuroblasts through Partial Necrosis of the Cerebral Cortex in Newborn Rats-Contribution to the Problems of Morphological Development and Developmental Period of Cerebral Microgyria. Histological and Autoradiographical Study. Acta Neuropathol. 1977, 38, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scantlebury, M.H.; Gibbs, S.A.; Foadjo, B.; Lema, P.; Psarropoulou, C.; Carmant, L. Febrile Seizures in the Predisposed Brain: A New Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 58, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, L.; Sidenvall, R.; Blomquist, H.K.; Heijbel, J. A Prospective Incidence Study of Febrile Convulsions. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1990, 79, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanopoulou, A.S. Dissociated Gender-Specific Effects of Recurrent Seizures on GABA Signaling in CA1 Pyramidal Neurons: Role of GABAA Receptors. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez, J.L.; McCarthy, M.M. Evidence for an Extended Duration of GABA-Mediated Excitation in the Developing Male Versus Female Hippocampus. Dev. Neurobiol. 2007, 14, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ari, Y. Excitatory Actions of GABA during Development: The Nature of the Nurture. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kight, K.E.; McCarthy, M.M. Androgens and the Developing Hippocampus. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloc, M.L.; Marchand, D.H.; Holmes, G.L.; Pressman, R.D.; Barry, J.M. Cognitive Impairment Following Experimental Febrile Seizures Is Determined by Sex and Seizure Duration. Epilepsy Behav. 2022, 126, 108430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tancredi, V.; D’Arcangelo, G.; Zona, C.; Siniscalchi, A.; Avoli, M. Induction of Epileptiform Activity by Temperature Elevation in Hippocampal Slices from Young Rats: An In Vitro Model for Febrile Seizures? Epilepsia 1992, 33, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weninger, J.; Meseke, M.; Rana, S.; Förster, E. Heat-Shock Induces Granule Cell Dispersion and Microgliosis in Hippocampal Slice Cultures. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hájos, N.; Mody, I. Establishing a Physiological Environment for Visualized in Vitro Brain Slice Recordings by Increasing Oxygen Supply and Modifying ACSF Content. J. Neurosci. Methods 2009, 183, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postnikova, T.Y.; Griflyuk, A. V.; Amakhin, D. V.; Kovalenko, A.A.; Soboleva, E.B.; Zubareva, O.E.; Zaitsev, A. V. Early Life Febrile Seizures Impair Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity in Young Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, T.N.; Golden, G.T.; Smith, G.G.; DeMuth, D.; Buono, R.J.; Berrettini, W.H. Mouse Strain Variation in Maximal Electroshock Seizure Threshold. Brain Res. 2002, 936, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosobud, A.E.; Crabbe, J.C. Genetic Correlations among Inbred Strain Sensitivities to Convulsions Induced by 9 Convulsant Drugs. Brain Res. 1990, 526, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yushko, L. V.; Kotova, M.M.; Vyunova, T. V.; Kalueff, A. V. Experimental Zebrafish Models of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of CNS Diseases. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2023 596 2024, 59, 2114–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinday, M.T.; Baraban, S.C. Large-Scale Phenotype-Based Antiepileptic Drug Screening in a Zebrafish Model of Dravet Syndrome. eNeuro 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhish, M.; Manjubala, I. Effectiveness of Zebrafish Models in Understanding Human Diseases—A Review of Models. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meshalkina, D.A.; Kysil, E. V.; Warnick, J.E.; Demin, K.A.; Kalueff, A. V. Adult Zebrafish in CNS Disease Modeling: A Tank That’s Half-Full, Not Half-Empty, and Still Filling. Lab Anim. (NY). 2017, 46, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.M.; Ullmann, J.F.P.; Norton, W.H.J.; Parker, M.O.; Brennan, C.H.; Gerlai, R.; Kalueff, A. V Molecular Psychiatry of Zebrafish. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Dupper, A.; Deshpande, T.; Graan, P.N.E.D.; Steinhäuser, C.; Bedner, P. Experimental Febrile Seizures Impair Interastrocytic Gap Junction Coupling in Juvenile Mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 94, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, C.; Matyash, M.; Pivneva, T.; Schipke, C.G.; Ohlemeyer, C.; Hanisch, U.-K.; Kirchhoff, F.; Kettenmann, H. GFAP Promoter-Controlled EGFP-Expressing Transgenic Mice: A Tool to Visualize Astrocytes and Astrogliosis in Living Brain Tissue. Glia 2001, 33, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanci, F.; Türay, S.; Balci, P.; Kabakuş, N. Reflex Epilepsy with Hot Water: Clinical and EEG Findings, Treatment, and Prognosis in Childhood. Neuropediatrics 2020, 51, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogland, G.; Raijmakers, M.; Clynen, E.; Brône, B.; Rigo, J.-M.; Swijsen, A. Experimental Early-Life Febrile Seizures Cause a Sustained Increase in Excitatory Neurotransmission in Newborn Dentate Granule Cells. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, H.R.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, S.W.; Baek, H.S.; Byun, J.C.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.M. Seasonal Trend of Viral Prevalence and Incidence of Febrile Convulsion: A Korea Public Health Data Analysis. Child. (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, L.R. Invited Review: Cytokine Regulation of Fever: Studies Using Gene Knockout Mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 2648–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haveman, J.; Geerdink, A.G.; Rodermond, H.M. Cytokine Production after Whole Body and Localized Hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperth. 1996, 12, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, C.; Vezzani, A.; Behrens, M.; Bartfai, T.; Baram, T.Z. Interleukin-1β Contributes to the Generation of Experimental Febrile Seizures. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladehin, A.; Blatteis, C.M. Induction of Fos Protein in Neonatal Rat Hypothalami Following Intraperitoneal Endotoxin Injection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997, 813, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubareva, O.E.; Postnikova, T.Y.; Grifluk, A. V.; Schwarz, A.P.; Smolensky, I. V.; Karepanov, A.A.; Vasilev, D.S.; Veniaminova, E.A.; Rotov, A.Y.; Kalemenev, S. V.; et al. Exposure to Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide in Early Life Affects the Expression of Ionotropic Glutamate Receptor Genes and Is Accompanied by Disturbances in Long-Term Potentiation and Cognitive Functions in Young Rats. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 90, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postnikova, T.Y.; Griflyuk, A. V.; Ergina, J.L.; Zubareva, O.E.; Zaitsev, A. V. Administration of Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide during Early Postnatal Ontogenesis Induces Transient Impairment of Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity Associated with Behavioral Abnormalities in Young Rats. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heida, J.G.; Teskey, G.C.; Pittman, Q.J. Febrile Convulsions Induced by the Combination of Lipopolysaccharide and Low-Dose Kainic Acid Enhance Seizure Susceptibility, Not Epileptogenesis, in Rats. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 1898–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, W. a; Robinson, S.M. Minimal Penetration of LPS across the Murine BBB. Brain Behav. Immunol. 2010, 24, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Jiang, Y. How Does Peripheral Lipopolysaccharide Induce Gene Expression in the Brain of Rats? Toxicology 2004, 201, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucile, Capuron; Miller, A.H. Immune System to Brain Signaling. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 130, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, V.H. The Influence of Systemic Inflammation on Inflammation in the Brain: Implications for Chronic Neurodegenerative Disease. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2004, 18, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvin, Y.; Tovote, P.; Pentkowski, N.S.; Zeyda, T.; King, L.B.; Vasconcellos, A.J.; Dunlap, C.; Spiess, J.; Blanchard, D.C.; Blanchard, R.J. Maternal Separation Modulates Short-Term Behavioral and Physiological Indices of the Stress Response. Horm. Behav. 2010, 58, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.; Schmerder, K.; Hedtstück, M.; Bösing, K.; Mundorf, A.; Freund, N. Maternal Separation and Its Developmental Consequences on Anxiety and Parvalbumin Interneurons in the Amygdala. J. Neural Transm. 2023, 130, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.G.; Chang, W.; Shin, S.Y.; Adhikari, A.S.; Seol, G.H.; Song, D.Y.; Min, S.S. Maternal Separation in Mice Leads to Anxiety-like/Aggressive Behavior and Increases Immunoreactivity for Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase and Parvalbumin in the Adolescence Ventral Hippocampus. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2023, 27, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Ramirez, M.; Salgado-Ceballos, H.; Orozco-Suarez, S.A.; Rocha, L. Hyperthermic Seizures and Hyperthermia in Immature Rats Modify the Subsequent Pentylenetetrazole-Induced Seizures. Seizure 2009, 18, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, A.; Bender, R.A.; Chen, Y.; Dube, C.; Eghbal-Ahmadi, M.; Baram, T.Z. Developmental Febrile Seizures Modulate Hippocampal Gene Expression of Hyperpolarization-Activated Channels in an Isoform- and Cell-Specific Manner. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 4591–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaindl, A.M.; Koppelstaetter, A.; Nebrich, G.; Stuwe, J.; Sifringer, M.; Zabel, C.; Klose, J.; Ikonomidou, C. Brief Alteration of NMDA or GABAA Receptor Mediated Neurotransmission Has Long Term Effects on the Developing Cerebral Cortex. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2008, 7, 2293–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizenga, M.N.; Forcelli, P.A. Neuroprotective Action of the CB1/2 Receptor Agonist, WIN 55,212-2, against DMSO but Not Phenobarbital-Induced Neurotoxicity in Immature Rats. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 35, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, S.; Tamer, Z.; Opoku, F.; Forcelli, P.A. Anticonvulsant Drug-Induced Cell Death in the Developing White Matter of the Rodent Brain. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonomidou, C. Triggers of Apoptosis in the Immature Brain. Brain Dev. 2009, 31, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torolira, D.; Suchomelova, L.; Wasterlain, C.G.; Niquet, J. Phenobarbital and Midazolam Increase Neonatal Seizure-Associated Neuronal Injury. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 82, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, R.A.; Dubé, C.; Gonzalez-Vega, R.; Mina, E.W.; Baram, T.Z. Mossy Fiber Plasticity and Enhanced Hippocampal Excitability, without Hippocampal Cell Loss or Altered Neurogenesis, in an Animal Model of Prolonged Febrile Seizures. Hippocampus 2003, 13, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griflyuk, A. V.; Postnikova, T.Y.; Malkin, S.L.; Zaitsev, A. V. Alterations in Rat Hippocampal Glutamatergic System Properties after Prolonged Febrile Seizures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, J.W.; Brady, R.J.; Martin, D.L. Postnatal Development of GABA-Mediated Synaptic Inhibition in Rat Hippocampus. Neuroscience 1989, 28, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, Z.; Yan, X.-X.X.; Haftoglou, S.; Ribak, C.E.; Baram, T.Z. Seizure-Induced Neuronal Injury: Vulnerability to Febrile Seizures in an Immature Rat Model. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 4285–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallyas, F.; Güldner, F.H.; Zoltay, G.; Wolff, J.R. Golgi-like Demonstration of “Dark” Neurons with an Argyrophil III Method for Experimental Neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol. 1990, 79, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallyas, F.; Farkas, O.; Mázló, M. Gel-to-Gel Phase Transition May Occur in Mammalian Cells: Mechanism of Formation of “Dark” (Compacted) Neurons. Biol. cell 2004, 96, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallyas, F.; Csordás, A.; Schwarcz, A.; Mázló, M. “Dark” (Compacted) Neurons May Not Die through the Necrotic Pathway. Exp. brain Res. 2005, 160, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, A.; Kátai, E.; Kálmán, E.; Bogner, P.; Schwarcz, A.; Dóczi, T.; Sík, A.; Pál, J. In Vivo Detection of Hyperacute Neuronal Compaction and Recovery by MRI Following Electric Trauma in Rats. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2016, 44, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, D.S.; Tumanova, N.L.; Kim, K.K.; Lavrentyeva, V. V.; Lukomskaya, N.Y.; Zhuravin, I.A.; Magazanik, L.G.; Zaitsev, A. V. Transient Morphological Alterations in the Hippocampus After Pentylenetetrazole-Induced Seizures in Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2018, 43, 1671–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijmakers, M.; Clynen, E.; Smisdom, N.; Nelissen, S.; Brône, B.; Rigo, J.M.; Hoogland, G.; Swijsen, A. Experimental Febrile Seizures Increase Dendritic Complexity of Newborn Dentate Granule Cells. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.L.; Pun, R.Y.K.; Yin, H.; Faulkner, C.R.; Loepke, A.W.; Danzer, S.C. Heterogeneous Integration of Adult-Generated Granule Cells into the Epileptic Brain. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Chen, Y.-B.; Zhang, Y.-F. The Rearrangement of Actin Cytoskeleton in Mossy Fiber Synapses in a Model of Experimental Febrile Seizures. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1107538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łotowska, J.; Sobaniec, P.; Sobaniec-Łotowska, M.; Szukiel, B.; Łukasik, M.; Łotowska, S. Effects of Topiramate on the Ultrastructure of Synaptic Endings in the Hippocampal CA1 and CA3 Sectors in the Rat Experimental Model of Febrile Seizures: The First Electron Microscopy Report. Folia Neuropathol. 2019, 57, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaniec, P.; Lotowska, J.M.; Sobaniec-Lotowska, M.E.; Zochowska-Sobaniec, M. Influence of Topiramate on the Synaptic Endings of the Temporal Lobe Neocortex in an Experimental Model of Hyperthermia-Induced Seizures: An Ultrastructural Study. Brain Sci. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Gao, H.; Yang, Y.; Fu, R. Repeated Febrile Convulsions Impair Hippocampal Neurons and Cause Synaptic Damage in Immature Rats: Neuroprotective Effect of Fructose-1,6-Diphosphate. Neural Regen. Res. 2014, 9, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, C.M.; Ravizza, T.; Hamamura, M.; Zha, Q.; Keebaugh, A.; Fok, K.; Andres, A.L.; Nalcioglu, O.; Obenaus, A.; Vezzani, A.; et al. Epileptogenesis Provoked by Prolonged Experimental Febrile Seizures: Mechanisms and Biomarkers. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 7484–7494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.P.; Brennan, G.P.; Curran, M.; Kinney-Lang, E.; Dubé, C.; Rashid, F.; Ly, C.; Obenaus, A.; Baram, T.Z. Rapid, Coordinate Inflammatory Responses after Experimental Febrile Status Epilepticus: Implications for Epileptogenesis. eNeuro 2015, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griflyuk, A. V.; Postnikova, T.Y.; Zaitsev, A. V. Prolonged Febrile Seizures Impair Synaptic Plasticity and Alter Developmental Pattern of Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP)-Immunoreactive Astrocytes in the Hippocampus of Young Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Pristov, J.B.; Nobili, P.; Nikolić, L. Can Glial Cells Save Neurons in Epilepsy? Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannasch, U.; Vargová, L.; Reingruber, J.; Ezan, P.; Holcman, D.; Giaume, C.; Syková, E.; Rouach, N. Astroglial Networks Scale Synaptic Activity and Plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 8467–8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łotowska, J.M.; Sobaniec-Łotowska, M.E.; Sobaniec, W. Ultrastructural Features of Astrocytes in the Cortex of the Hippocampal Gyrus and in the Neocortex of the Temporal Lobe in an Experimental Model of Febrile Seizures and with the Use of Topiramate. Folia Neuropathol. 2009, 47, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Łotowska, J.M.; Sobaniec-Łotowska, M.E.; Sendrowski, K.; Sobaniec, W.; Artemowicz, B. Ultrastructure of the Blood-Brain Barrier of the Gyrus Hippocampal Cortex in an Experimental Model of Febrile Seizures and with the Use of a New Generation Antiepileptic Drug--Topiramate. Folia Neuropathol. 2008, 46, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Curran, M.M.; Hall, A.M.; Patterson, K.P.; Shao, M.; Eltom, N.; Chen, K.; Dubé, C.M.; Baram, T.Z. Dexamethasone Attenuates Hyperexcitability Provoked by Experimental Febrile Status Epilepticus. eNeuro 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Huang, W.; Han, S.; Yin, J.; Liu, W.; He, X.; Peng, B. Activation of TRPV1 Contributes to Recurrent Febrile Seizures via Inhibiting the Microglial M2 Phenotype in the Immature Brain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Leak, R.K.; Shi, Y.; Suenaga, J.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, P.; Chen, J. Microglial and Macrophage Polarization—New Prospects for Brain Repair. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaniani, N.R.; Roohbakhsh, A.; Moghimi, A.; Mehri, S. Protective Effect of Toll-like Receptor 4 Antagonist on Inflammation, EEG, and Memory Changes Following Febrile Seizure in Wistar Rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 420, 113723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H.; Kim, S.-W.; Im, H.; Lee, Y.R.; Kim, G.W.; Ryu, S.; Park, D.-K.; Kim, D.-S. Febrile Seizure Causes Deficit in Social Novelty, Gliosis, and Proinflammatory Cytokine Response in the Hippocampal CA2 Region in Rats. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Connors, B.W. High Temperatures Alter Physiological Properties of Pyramidal Cells and Inhibitory Interneurons in Hippocampus. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postnikova, T.Y.; Griflyuk, A. V; Zhigulin, A.S.; Soboleva, E.B.; Barygin, O.I.; Amakhin, D. V; Zaitsev, A. V Febrile Seizures Cause a Rapid Depletion of Calcium-Permeable AMPA Receptors at the Synapses of Principal Neurons in the Entorhinal Cortex and Hippocampus of the Rat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.; León-Navarro, D.A.; Martín, M. Glutamatergic System Is Affected in Brain from an Hyperthermia-Induced Seizures Rat Model. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaitsev, A. V.; Smolensky, I. V.; Jorratt, P.; Ovsepian, S. V. Neurobiology, Functions, and Relevance of Excitatory Amino Acid Transporters (EAATs) to Treatment of Refractory Epilepsy. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Baram, T.Z.; Soltesz, I. Febrile Seizures in the Developing Brain Result in Persistent Modification of Neuronal Excitability in Limbic Circuits. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, C.; Chen, K.; Eghbal-Ahmadi, M.; Brunson, K.; Soltesz, I.; Baram, T.Z.; Eghbal-Ahmadi, M.; Brunson, K.; Soltesz, I.; Baram, T.Z.; et al. Prolonged Febrile Seizures in the Immature Rat Model Enhance Hippocampal Excitability Long Term. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 47, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, K.P.; Kramer, M.A.; Mertz, J.; Staley, K.J.; White, J.A. Pyramidal Cells Accumulate Chloride at Seizure Onset. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 47, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librizzi, L.; Losi, G.; Marcon, I.; Sessolo, M.; Scalmani, P.; Carmignoto, G.; de Curtis, M. Interneuronal Network Activity at the Onset of Seizure-Like Events in Entorhinal Cortex Slices. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 10398–10407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swijsen, A.; Brône, B.; Rigo, J.-M.; Hoogland, G. Long-Lasting Enhancement of GABA(A) Receptor Expression in Newborn Dentate Granule Cells after Early-Life Febrile Seizures. Dev. Neurobiol. 2012, 72, 1516–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.; León-Navarro, D.A.; Martín, M. Na(+)/K(+)- and Mg(2+)-ATPases and Their Interaction with AMPA, NMDA and D(2) Dopamine Receptors in an Animal Model of Febrile Seizures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, K.J.; Goudet, C. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. CXI. Pharmacology, Signaling, and Physiology of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2021, 73, 521–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niswender, C.M.; Conn, P.J. Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors: Physiology, Pharmacology, and Disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 50, 295–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Gong, J.; Tu, E.; Long, L.; Xiao, B.; Yan, X.; Wan, L. Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors (MGluRs) in Epileptogenesis: An Update on Abnormal MGluRs Signaling and Its Therapeutic Implications. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notenboom, R.G.E.; Ramakers, G.M.J.J.; Kamal, A.; Spruijt, B.M.; De Graan, P.N.E. Long-Lasting Modulation of Synaptic Plasticity in Rat Hippocampus after Early-Life Complex Febrile Seizures. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010, 32, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.; Kuo, Y.-M.; Huang, A.-M.; Huang, C.-C. Repetitive Febrile Seizures in Rat Pups Cause Long-Lasting Deficits in Synaptic Plasticity and NR2A Tyrosine Phosphorylation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005, 18, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.M.; Teyler, T.J. Developmental Onset of Long-Term Potentiation in Area CA1 of the Rat Hippocampus. J. Physiol. 1984, 346, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.S.; Suppes, T.; Harris, K.M. Stereotypical Changes in the Pattern and Duration of Long-Term Potentiation Expressed at Postnatal Days 11 and 15 in the Rat Hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 1993, 70, 1412–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, D.; Oliver, M.; Lynch, G. Developmental Changes in Synaptic Properties in Hippocampus of Neonatal Rats. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1989, 49, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Harris, K.M. Developmental Regulation of the Late Phase of Long-Term Potentiation (L-LTP) and Metaplasticity in Hippocampal Area CA1 of the Rat. J. Neurophysiol. 2012, 107, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benveniste, M.; Clements, J.; Vyklický, L.; Mayer, M.L. A Kinetic Analysis of the Modulation of N-Methyl-D-Aspartic Acid Receptors by Glycine in Mouse Cultured Hippocampal Neurones. J. Physiol. 1990, 428, 333–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, K.A.; Popescu, G.K. Glycine-Dependent Activation of NMDA Receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 2015, 145, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneberger, C.; Papouin, T.; Oliet, S.H.R.; Rusakov, D.A. Long-Term Potentiation Depends on Release of d-Serine from Astrocytes. Nature 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, C.; Richichi, C.; Bender, R.A.; Chung, G.; Litt, B.; Baram, T.Z. Temporal Lobe Epilepsy after Experimental Prolonged Febrile Seizures: Prospective Analysis. Brain 2006, 129, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipp, K.H.; Mecklinger, A.; Becker, M.; Reith, W.; Gortner, L. Infant Febrile Seizures: Changes in Declarative Memory as Revealed by Event-Related Potentials. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2010, 121, 2007–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinos, M.M.; Yoong, M.; Patil, S.; Chin, R.F.M.; Neville, B.G.; Scott, R.C.; de Haan, M.; Haan, M. De Recognition Memory Is Impaired in Children after Prolonged Febrile Seizures. Brain 2012, 135, 3153–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagoubi, N.; Jomni, Y.; Sakly, M. Hyperthermia-Induced Febrile Seizures Have Moderate and Transient Effects on Spatial Learning in Immature Rats. Behav. Neurol. 2015, 2015, 924303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, C.M.; Zhou, J.-L.; Hamamura, M.; Zhao, Q.; Ring, A.; Abrahams, J.; McIntyre, K.; Nalcioglu, O.; Shatskih, T.; Baram, T.Z.; et al. Cognitive Dysfunction after Experimental Febrile Seizures. Exp. Neurol. 2009, 215, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, D.; Feng, B.; Chen, B.; Tang, Y.; Jin, M.; Zhao, H.; Dai, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Prolonged Febrile Seizures Induce Inheritable Memory Deficits in Rats through DNA Methylation. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alese, O.O.; Mabandla, M. V Transgenerational Deep Sequencing Revealed Hypermethylation of Hippocampal MGluR1 Gene with Altered MRNA Expression of MGluR5 and MGluR3 Associated with Behavioral Changes in Sprague Dawley Rats with History of Prolonged Febrile Seizure. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0225034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H.; Kim, S.-W.; Im, H.; Song, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, Y.R.; Kim, G.W.; Hwang, C.; Park, D.-K.; Kim, D.-S. Febrile Seizures Cause Depression and Anxiogenic Behaviors in Rats. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, M.; León-Navarro, D.A.; Martín, M. Early-Life Hyperthermic Seizures Upregulate Adenosine A2A Receptors in the Cortex and Promote Depressive-like Behavior in Adult Rats. Epilepsy Behav. 2018, 86, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model organism |

Line / breed | Age | The characteristics of the convulsive episode | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | Sprague-Dawley | P6-P8 | Body temperature rises to 40°C. Freezing, rare facial automatisms | [12] |

| Sprague-Dawley Wistar |

P10-P11 | Body temperature rises to 39°-40°C. Facial automatisms, often accompanied by unilateral bending of the body. Myoclonic twitching of the hind limbs. Clonic convulsions. | [12,84,88] | |

| Wistar | P20 | Threshold temperature 44°C. Generalised clonic convulsions. The duration of convulsions is significantly longer than in rats of other ages. | [36] | |

| Mouse | C57BL/6J | P10 | Similar to the course of FSs in rats at the age of P10 | [96] |

| transgenic mice with human GFAP (hGFAP) promoter-controlled expression of EGFРP (based on the FVB/N line) | P14-P15 | Several episodes of sudden cessation of activity and prolonged immobility with reduced responsiveness. Facial automatisms (chewing). Clonic or tonic–clonic seizures are not observed. | [96], [97] | |

| Drosophila | 2-day-old fly | Brief leg twitches, followed by failure to maintain standing posture, with wing flapping, leg twitching, and sometimes abdominal curling. | [18] | |

| Danio rerio | larval aged 3 to 7 days post-fertilization | After implantation of a glass microelectrode into the forebrain of the larva, abnormal electrographic convulsive activity is recorded when the temperature in the bath where the larvae are kept rises. | [17] | |

| 1 week after FSs | 1 to 4 weeks after FSs | > 1 month after FSs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Neurons | There is minimal cell death in the initial hours following FSs [125] Significant populations of silver-stained 'dark' neurons in discrete hippocampal and amygdala regions [125] A decrease in the number of neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region, hilus and dentate gyrus [123] The ultrastructural disruption of synaptic endings in both hippocampal neurons and temporal lobe cortical cells [134,135,136] |

A decrease in the number of neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region [123] Increased dendrite length of granular cells that appeared after seizures [131] |

A decrease in the number of neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region [123] Excessive growth of mossy fibers [122] Increase in F-actin in the presynaptic endings of mossy fiber synapses [133] Increased dendritic complexity and number of mushroom-like spines in dentate gyrus cells [131] |

| Glial cells | Activation of astroglial cells [137,138] Reduction of astrocytic gap junction coupling, decrease in the level of connexin 43 [96] Edema in astrocytes, damage to the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria [142]. Disruption of the blood-brain barrier [143,144] Activation of microglial cells [28,96,138,145] |

Activation of astrocytic and microglial cells in the hippocampal CA2 region [149] Impaired of the age-related dynamics of astrocyte maturation [139] |

||

|

Synaptic transmission Synaptic plasticity |

Decrease in synaptic transmission efficiency and a decrease in calcium conductance through calcium-permeable AMPA receptors [151] Decrease in synaptic transmission efficiency, changes in short-term plasticity in hippocampal CA3-CA1 neurons and a decrease in the frequency of miniature excitatory synaptic currents [123] Increased GLT-1 levels, reduced glutamate concentration, and unchanged mGlu5R levels in the cortex brain [152] |

Increased inhibitory postsynaptic currents in the hippocampus mediated by GABAA receptors [154] Increased Na+/K+-ATPase activity in cortical plasma membranes [159] Decrease in the level of LTP [139,164] Disturbance of age-related changes in the magnitude and character of LTP [139] Heightened desensitization of NMDA receptors [88] Reduction in tyrosine phosphorylation of the GluN2A subunit of NMDA receptors [164] Increase in the threshold for pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures [115] Decrease in GLT-1 levels [152] Increase in mGlu5R levels [152] |

Increased expression of the GABAA receptor in granular cells born after FSs in the dentate gyrus [158] Increased Na+/K+-ATPase activity in cortical plasma membranes [159] Decrease in the level of the LTP [139] Increase in the maximal electroshock seizure threshold [123] Increased susceptibility to seizures in rats when kainate was used [155] Electroencephalographically recorded epileptiform discharges in the limbic system [172] |

|

| Behavior | Cognitive impairment [175] Depressive-like behavior [178,179] Anxiogenic behaviors [179] Social novelty deficits, repetitive behavior and hyperlocomotion [149] |

Cognitive impairment [84,139,176,177] Depressive-like behavior [178,179,180] Anxiogenic behaviors [179] Social novelty deficits, repetitive behavior [149] |

||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).