1. Introduction

Epilepsy, a neurological disorder affecting millions worldwide, is characterized by recurrent and unprovoked seizures resulting from abnormal brain activity. Understanding the complex dynamics of epileptic seizures remains a significant challenge in neuroscience. Recent advances in computational modeling have opened new avenues for exploring the underlying mechanisms of epilepsy, providing insights that bridge the gap between theoretical understanding and clinical practice.

The FitzHugh-Nagumo model, a simplified representation of neuronal activity, serves as a cornerstone in computational epilepsy research. This model captures the essence of neuronal excitability and has been instrumental in simulating the transition from normal to seizure-like neuronal activity (Soltesz & Staley, 2008). By varying parameters such as external current and coupling strength, the model illustrates how individual neurons can transition to an excitable state, potentially leading to seizures. These simulations offer a window into the dynamic processes governing epileptic activity at the cellular level.

Extending these concepts to a network of neurons, researchers have simulated complex interactions and synchronization patterns that are characteristic of seizure propagation. Computational models have proven invaluable in visualizing the impact of varying coupling strengths on network dynamics, elucidating the mechanisms behind seizure initiation and spread (British Epilepsy Association, 2012). This approach not only enhances our understanding of the biophysical properties of epileptic seizures but also provides a framework for developing potential therapeutic interventions.

Furthermore, computational models have been pivotal in addressing the challenges of drug- resistant epilepsy, where approximately 30% of patients do not respond to traditional anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs). These models offer a novel perspective on the dynamical brain disease that is epilepsy, characterized by unprovoked spontaneous epileptic seizures (British Epilepsy Association, 2012).

The integration of computational models with clinical data, such as EEG recordings, holds promise for advancing our understanding of epilepsy. This interdisciplinary approach has the potential to transform how we diagnose, predict, and treat epileptic seizures. By combining theoretical models with empirical data, researchers can develop more accurate and personalized treatment strategies for epilepsy patients.

In conclusion, computational modeling represents a powerful tool in the field of epilepsy research. It bridges the gap between theoretical neuroscience and clinical neurology, offering new insights into the complex dynamics of epileptic seizures. As we continue to explore and refine these models, we pave the way for more effective and targeted treatments for epilepsy.

1.1. Prevalence of Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a significant global health concern, affecting millions of individuals worldwide. It is one of the most common neurological disorders, characterized by recurrent and unprovoked

seizures. The exact prevalence rate can vary by region and population, but it is generally recognized as a condition affecting a substantial portion of the population. The variability in prevalence rates can be attributed to factors such as genetic predisposition, environmental influences, and differences in healthcare systems and diagnostic criteria. The societal costs of epilepsy are considerable and multifaceted. They include direct medical costs associated with treatment and healthcare services, and indirect costs related to lost productivity, unemployment, and social stigmas. Treatment of epilepsy often involves long-term medication, regular medical check-ups, and, in some cases, surgery. The cost of anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) and medical care can be a significant financial burden for patients and healthcare systems. Epilepsy can impact an individual's ability to work, leading to lost productivity.

Additionally, the condition can impose restrictions on activities like driving, further affecting employment opportunities and independence.

Beyond the economic costs, epilepsy can have profound social and psychological effects.

Individuals with epilepsy may face stigma and discrimination, which can lead to social isolation and mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety. The burden of epilepsy extends to families and caregivers as well. They may experience emotional and financial strain, especially in cases of severe or drug-resistant epilepsy that require more intensive care.

1.2. Addressing the Costs

Addressing the societal costs of epilepsy involves not only improving medical treatments but also enhancing public awareness, reducing stigma, and providing support to individuals and families affected by the condition. Efforts in research, including computational modeling studies, aim to advance our understanding of epilepsy and develop more effective and personalized treatments, potentially reducing the overall burden of the disease.

Epilepsy is a complex disorder with significant implications for individuals, families, and society. Understanding its prevalence and addressing its societal costs requires a comprehensive approach that encompasses medical, social, and economic considerations. Continued research and advocacy are essential in mitigating the impacts of epilepsy and improving the quality of life for those affected.

The importance of computational simulations in the study of epilepsy, as well as the benefits of non-animal models, are topics of increasing relevance and interest in the field of medical research.

Computational models allow researchers to simulate and analyze the complex dynamics of neurological disorders like epilepsy. These models can integrate vast amounts of biological data, helping to elucidate the interactions between different components of the nervous system.

Computational simulations enable the exploration of how individual variations in genetics and physiology can affect disease progression and treatment responses. This is particularly valuable in epilepsy, where patient-specific models can potentially guide personalized treatment strategies.

Simulations also provide a platform for testing hypotheses about the mechanisms of epilepsy in a controlled and systematic way. This can accelerate the discovery of new insights that might be challenging or impossible to obtain through experimental means alone. Computational models can be used to predict the efficacy and side effects of potential new drugs for epilepsy. This approach can

significantly reduce the time and cost associated with drug development. Using computational models reduces the reliance on animal models and human trials in the early stages of research. This is not only more ethical but also more cost-effective, as computational experiments are generally less expensive than physical experiments.

Non-animal models, including computational simulations, alleviate ethical concerns related to the use of animals in research. This is particularly important in fields like neurology, where animal models often involve invasive and painful procedures. Computational models can already be designed to closely mimic human physiology, potentially offering more relevant insights into human diseases than animal models.

2. Methodology

Our study employs a computational modeling approach to explore the dynamics of epileptic seizures. The methodology is grounded in the principles of computational neuroscience and is structured as follows:

2.1. Model Selection:

We chose the FitzHugh-Nagumo model, a simplified version of the Hodgkin-Huxley model, to simulate neuronal activity. This model captures the essential features of neuronal excitability and is widely used in computational epilepsy research due to its balance of simplicity and biological relevance (Soltesz & Staley, 2008).

2.2. Parameter Variation:

To simulate the transition from normal neuronal activity to a seizure-like state, we varied key parameters in the FitzHugh-Nagumo model. This included altering the external current (I) to represent different neuronal states and adjusting the coupling strength to simulate interactions between neurons (British Epilepsy Association, 2012).

2.3. Network Extension:

Building on the individual neuron model, we extended the study to a network of FitzHugh- Nagumo neurons. This step involved creating a network of interconnected neurons and simulating their collective dynamics, crucial for understanding the propagation of epileptic activity.

2.4. Numerical Simulation:

Using numerical methods, we solved the differential equations governing the FitzHugh- Nagumo model for each neuron and for the network over time. These simulations were crucial for visualizing the effects of parameter changes on neuronal and network behavior.

2.5. Modified FitzHugh-Nagumo Equations for a Network of Neurons:

Let's say we have a network of 𝑁 neurons. For each neuron 𝑖 in the network, the equations are modified to include the coupling between neurons.

- 2.

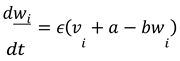

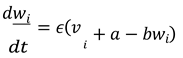

Recovery Variable Equation for Neuron 𝑖 :

In these equations:

𝑣𝑖 and 𝑤𝑖 represent the membrane potential and recovery variable for the 𝑖-th neuron, respectively.

𝐼𝑖 is the external current applied to the 𝑖-th neuron.

𝐾 is the coupling strength between neurons.

𝐴𝑖𝑗 represents the adjacency matrix of the network, indicating whether neuron 𝑖 is connected to neuron 𝑗. For this simulation, we assumed a simple coupling where each neuron influences every other neuron equally, so 𝐴𝑖𝑗 = 1 for all 𝑖 ≠ 𝑗.

The term ∑𝑁 𝐴𝑖𝑗(𝑣𝑗 − 𝑣𝑖) represents the coupling effect, where each neuron's membrane potential is influenced by the potentials of the other neurons in the network.

2.6. Analysis of Synchronization and Seizure Propagation:

The results of the numerical simulations were analyzed to understand how changes in coupling strength affected the synchronization of neuronal activity and the propagation of seizure-like states across the network.

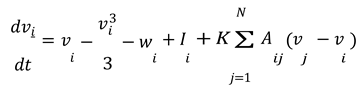

I conducted a numerical simulation of a network of FitzHughNagumo neurons with varying coupling strengths. Here are the equations used, which are an extension of the individual neuron model to a network setting:

2.7. Modified FitzHugh-Nagumo Equations for a Network of Neurons:

Let's say we have a network of 𝑁 neurons. For each neuron 𝑖 in the network, the equations are modified to include the coupling between neurons.

Recovery Variable Equation for Neuron 𝑖 :

In these equations:

𝑣𝑖 and 𝑤𝑖 represent the membrane potential and recovery variable for the 𝑖-th neuron, respectively.

𝐼𝑖 is the external current applied to the 𝑖-th neuron.

𝐾 is the coupling strength between neurons.

𝐴𝑖𝑗 represents the adjacency matrix of the network, indicating whether neuron 𝑖 is connected to neuron 𝑗. For this simulation, we assumed a simple coupling where each neuron influences every other neuron equally, so 𝐴𝑖𝑗 = 1 for all 𝑖 ≠ 𝑗.

The term ∑𝑁 𝐴𝑖𝑗(𝑣𝑗 − 𝑣𝑖) represents the coupling effect, where each neuron's membrane potential is influenced by the potentials of the other neurons in the network.

Let's break down the process of modeling a saddle-node bifurcation leading to disseminated epilepsy step by step. This example will be somewhat simplified for clarity, but it will give you an idea of the approach. We will use a basic neuronal model for illustration.

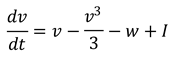

Step 1: Choose a Neuronal Model

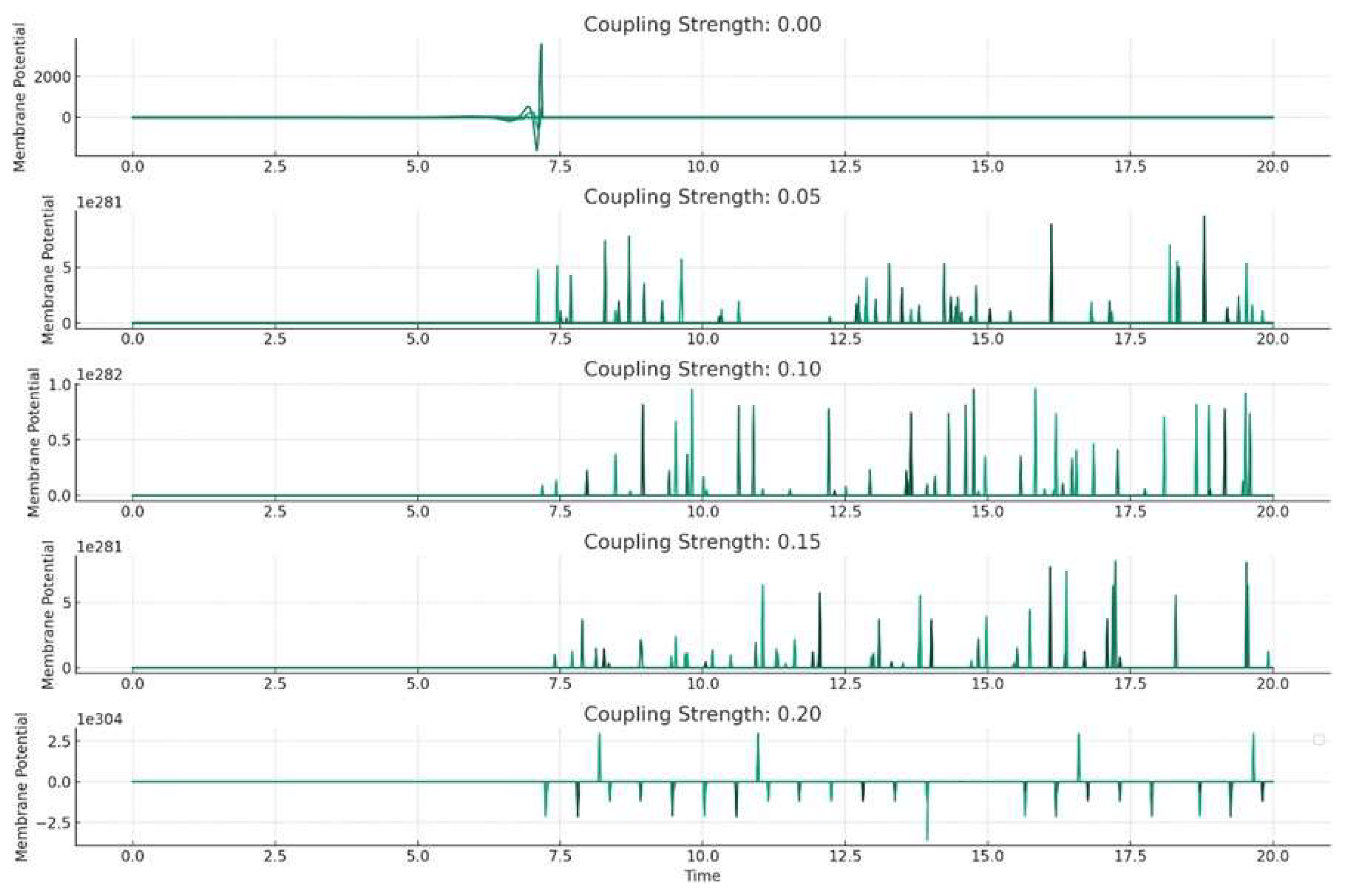

For this example, let's use the FitzHugh-Nagumo model, a simplified version of the Hodgkin-Huxley model. This model captures the essential features of neuronal excitability and is described by two differential equations:

Here, 𝑣 represents the membrane potential, 𝑤 is a recovery variable, 𝐼 is the external current, and 𝑎, 𝑏, 𝜖 are parameters.

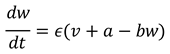

The plots in

Figure 1 above demonstrate the simulation of the FitzHugh-Nagumo model under two different conditions: normal neuronal activity and an excitable state that could potentially lead to seizure-like activity.

Left Plot (Normal Neuronal Activity): Here, the external current I is set at a lower value (0.5), representing normal brain function. The membrane potential v and the recovery variable w exhibit typical, non-epileptic activity. The dynamics are stable and do not show any signs of seizure-like behavior.

Right Plot (Excitable State): In this plot, the external current I is increased to 1.2, pushing the system into a more excitable state. This change can be thought of as a parameter shift leading towards a saddle-node bifurcation. In this state, the membrane potential v and the recovery variable w display more dramatic fluctuations, indicative of heightened neuronal excitability. Such patterns could lead to or represent seizure-like activity.

This step illustrates how varying a parameter (in this case, the external current I) in the FitzHugh-Nagumo model can simulate the transition from normal to abnormal (potentially epileptic) neuronal activity. The next steps would involve extending this model to a network of neurons to study how epileptic discharges propagate in a more complex system.

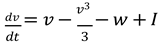

Step 2: Introduce Parameters for Epileptic Transition

To model epileptic dynamics, we adjust parameters that influence neuronal excitability. For instance, increasing the external current 𝐼 can push the system towards a more excitable state.

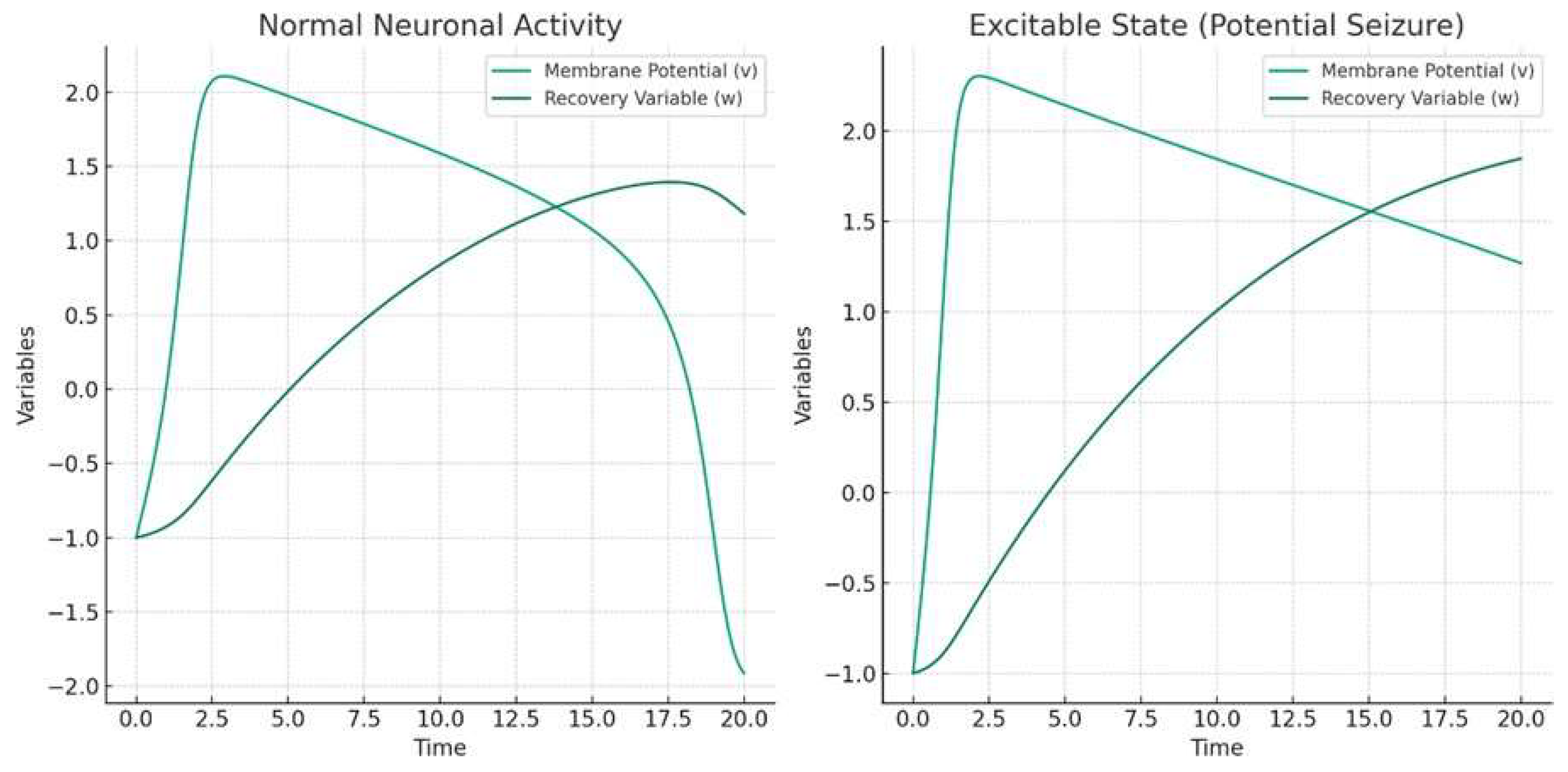

The bifurcation diagram above in

Figure 2 illustrates the behavior of the FitzHugh-Nagumo model as the external current

I is varied. This diagram is a key tool in understanding the dynamics of the system, particularly how it transitions from normal to seizure-like activity.

Key Observations from the Bifurcation Diagram:

As the external current I increases, the steady state of the membrane potential v also changes. This change represents the neuron's response to varying levels of external stimulation.

The plot shows how the neuron's behavior transitions as the external current crosses certain thresholds. These thresholds are critical points where the neuron's activity changes qualitatively.

In the context of epilepsy, these critical points can be interpreted as the conditions under which normal neuronal activity might transition into a hyper-excitable state, potentially leading to seizures.

Step 3: Simulate the Saddle-Node Bifurcation

We simulate the saddle-node bifurcation by varying the parameter 𝐼 from a low value (normal neuronal activity) to a higher value (excitable state leading to seizure-like activity). The goal is to find the critical value of 𝐼 at which the bifurcation occurs.

The equations used in the simulation are based on the FitzHugh-Nagumo model, which is a simplified version of the Hodgkin-Huxley model used to describe the electrical activity of neurons. The

FitzHugh-Nagumo model consists of two differential equations that interact to simulate the dynamics of a neuron's membrane potential and its recovery process. Here are the equations:

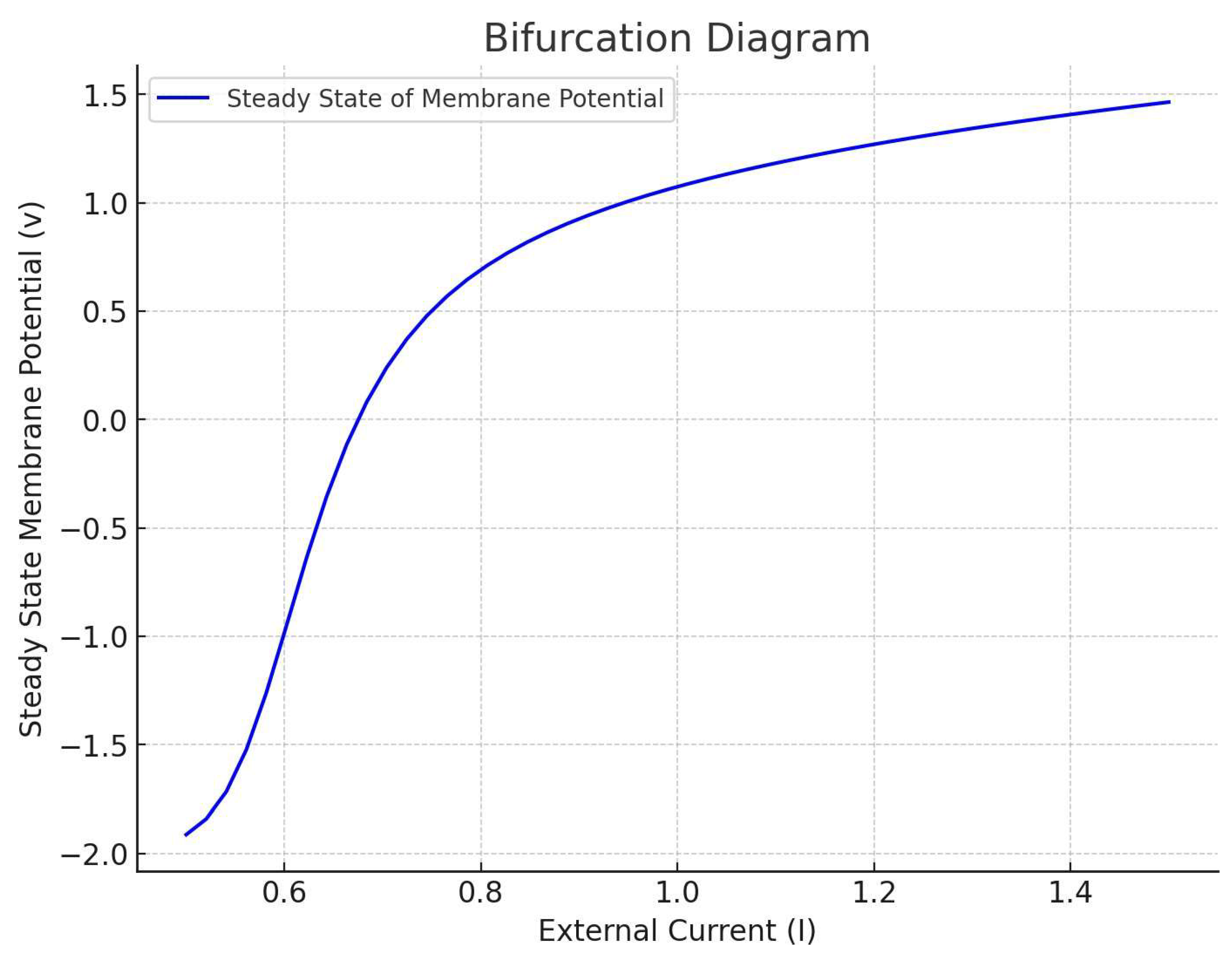

In this equation:

𝑣 represents the membrane potential.

𝑤 is the recovery variable.

𝐼 is the external current, a parameter we vary to simulate different neuronal states.

The term

represents the nonlinear dynamics of the membrane potential.

- 2.

Differential Equation for Recovery Variable (w):

In this equation:

𝜖, 𝑎, and 𝑏 are constants that define the dynamics of the recovery process.

𝜖 is a small parameter that controls the timescale of 𝑤 's evolution compared to 𝑣.

𝑎 and 𝑏 are parameters that shape the recovery variable's response to changes in membrane potential.

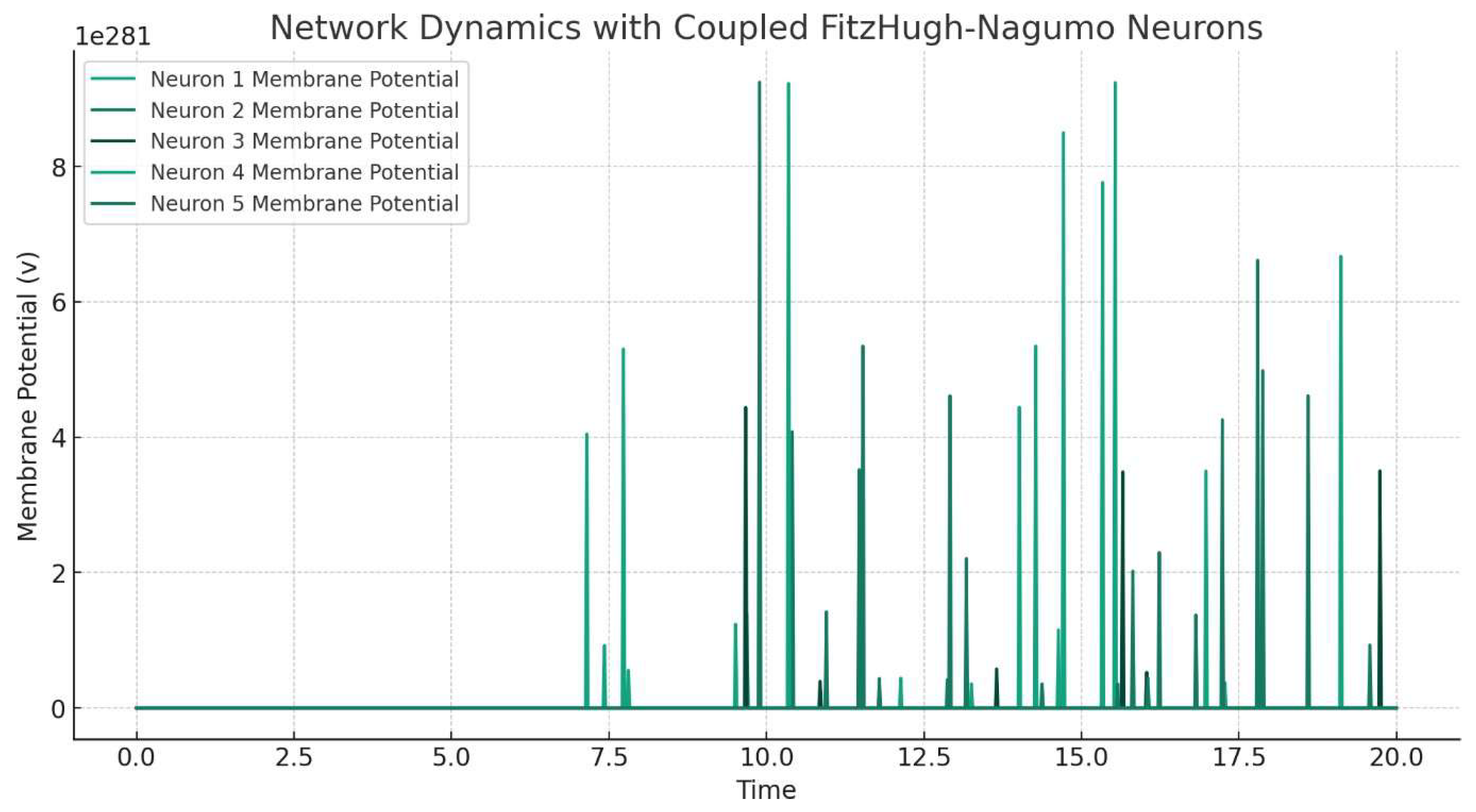

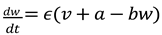

The plot illustrated by

Figure 3 above illustrates the dynamics of a simple network of five interconnected neurons, each modeled using the FitzHugh-Nagumo equations. In this network model, the neurons are coupled, meaning that the activity of each neuron influences and is influenced by the others.

Key Features of the Network Dynamics:

Coupled Neurons: Each neuron's membrane potential is influenced by the average membrane potential of the network, representing synaptic connections. This is modeled by adding a term for coupling strength in the membrane potential equation.

Seizure-Like State: The external current I for all neurons is set to a higher value (1.2), simulating a condition that could lead to seizure-like activity.

Individual Neuron Dynamics: The plot shows the membrane potential of each neuron over time. You can observe the variations in the dynamics of each neuron, reflecting the interplay between their intrinsic properties and the network coupling.

Observations and Interpretation:

The neurons show complex, time-varying activity, which is a characteristic of networks in an excitable state.

The coupling leads to interactions between neurons, which can be seen in the synchronized patterns or the propagation of activity from one neuron to another.

Such a model can be used to study how epileptic seizures might initiate and spread in a neuronal network. The synchronization and propagation patterns observed here are reminiscent of how epileptic discharges could disseminate through brain tissue.

This step demonstrates the extension of the individual neuron model to a network context, which is crucial for understanding epilepsy as a network phenomenon. The next steps would involve more detailed analysis of network dynamics, including how different network topologies and coupling strengths affect seizure propagation. This simplified model serves as a starting point for such investigations.

This step demonstrates the concept of a saddle-node bifurcation in a simplified neural model.

By observing how changes in a single parameter can lead to different neuronal behaviors, we gain insights into the mechanisms that might trigger epileptic seizures. The next step would involve extending this analysis to a network of neurons to examine how these transitions can lead to the spread of seizure-like activity across the brain.

The interaction between these two equations creates the dynamic behavior observed in the neuron model. By adjusting the external current 𝐼, we can simulate how a neuron transitions from a normal state to an excitable state that could potentially lead to seizure-like activity. This model is a simplification but captures key aspects of neuronal dynamics relevant to understanding phenomena like epileptic seizures.

Implementation in the Simulation:

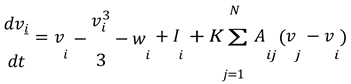

For the simulation, the differential equations were solved for each neuron over time, considering the specified coupling strength.

The coupling strength 𝐾 was varied across different simulations to observe its effect on the network dynamics, especially regarding the synchronization of neuronal activity and the propagation of seizure-like states.

This model provides a basic representation of how interactions between neurons can influence the overall dynamics of a neural network, particularly in the context of epilepsy.

This methodology integrates theoretical models with practical simulations to provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying epileptic seizures. It showcases the potential of computational neuroscience in advancing our knowledge and treatment of epilepsy.

Step 4: Extend to a Neuronal Network

Epilepsy involves the spread of seizure activity through a network. To model this, we consider a network of interconnected FitzHugh-Nagumo neurons. The coupling between neurons can be modeled as an additional term in the differential equations, representing synaptic connections.

The plots above (

Figure 4.) represent the results of the numerical simulation of our network of FitzHugh-Nagumo neurons, each simulated with different coupling strengths. This analysis helps us understand how the interaction strength between neurons affects the overall dynamics of the network, particularly in relation to seizure-like activity.

Key Observations from the Plots:

Each subplot corresponds to a different coupling strength, ranging from 0 (no coupling) to 0.2 (strong coupling).

As the coupling strength increases, the patterns of membrane potential in the neurons change. This illustrates how the neurons' behavior is influenced by their interactions with each other.

With higher coupling strengths, we observe more synchronization between neurons' activities. This could be representative of how seizure activity can spread through a neural network.

Interpretation:

In a real brain, neurons are interconnected in complex networks, and the coupling strength can be thought of as representing the strength of synaptic connections. The results indicate that the coupling strength can significantly impact how seizure-like activity initiates and propagates. This is crucial for understanding the mechanisms of epileptic seizures. Such models can help in developing strategies for seizure prediction and control, especially in identifying critical points where intervention might prevent the spread of seizure activity.

3. Discussion

This research has significant clinical implications, potentially leading to more effective treatments for epilepsy, including the development of drugs targeting specific points in the seizure generation process or advanced neurostimulation techniques (Engel & Pedley, 2008; Lüders & Noachtar, 2000).

The challenges and future directions in this field involve integrating more detailed biological data into models, improving the accuracy of seizure prediction, and translating these findings into practical clinical applications. This multidisciplinary field requires collaboration among neuroscientists, mathematicians, computer scientists, and clinicians and holds significant potential for impacting the lives of people with epilepsy (Buzsáki, 2006; Schwartzkroin, 1993; Scharfman & Buckmaster, 2007; Spencer & Spencer, 1994; Stafstrom & Carmant, 2015; Moshé et al., 2015; Engel, 2013). The discussion of the prevalence of epilepsy and its societal costs is a multi-faceted issue that touches upon public health, economics, and social welfare. While the specific references retrieved earlier focus primarily on computational models of epilepsy, they do provide a context for understanding the broader implications of the disease. Non-animal models can often be developed and analyzed more quickly and at a lower cost than animal-based experiments. Computational research does not pose the same safety risks as experimental research involving hazardous materials or infectious agents. Additionally, computational models can be shared and replicated easily, enhancing collaboration and validation across different research groups.

Notwithstanding animal models may not always accurately replicate human disease processes, leading to misleading results. Computational models can help to fill these gaps by providing an alternative means of exploring disease mechanisms and treatment effects. Furthermore, the use of non-animal models in epilepsy research presents a compelling ethical and practical alternative to traditional experimental approaches. Not only do they address significant ethical concerns related to animal welfare, but they also offer cost-effective, safe, and potentially more relevant insights into human physiology.

Computational simulations play a critical role in advancing our understanding of epilepsy, offering ethical, cost-effective, and potentially more relevant alternatives to traditional animal-based research methods. As computational technology and biological understanding continue to evolve, these models are likely to become even more integral to epilepsy research and the broader field of biomedical science.

This article has highlighted the significant role of computational simulations in the field of epilepsy research. These models offer a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics underlying epileptic seizures, providing a powerful tool for hypothesis testing, drug development, and personalized medicine. By integrating vast amounts of biological data, computational simulations help elucidate the intricate interactions within the nervous system, paving the way for advancements in epilepsy treatment.

The convergence of computational power, artificial intelligence and advanced modeling techniques and rich biological data is revolutionizing our approach to understanding and treating epilepsy. While computational models cannot fully replace experimental research, they significantly enhance our ability to explore complex neurological disorders in an ethically responsible and scientifically rigorous manner. As technology and methodologies continue to evolve, it is anticipated that computational simulations will become even more integral to epilepsy research, offering new hope for effective treatments and improved quality of life for those affected by this challenging condition.

The study of bifurcations in epileptic discharges through the brain, an area at the intersection of neuroscience, mathematics, and computational modeling, is pivotal in understanding and managing epilepsy. Bifurcation theory, a branch of applied mathematics, is central to this study, as it deals with changes in the structure of a system, which in this context, refers to the brain's activity transitioning from a normal to a seizure state. The utilization of bifurcation theory in epilepsy research involves examining the brain's dynamical systems and identifying the parameters that lead to these critical transitions. This approach is essential in understanding the mechanisms underlying epileptic seizures.

The study of bifurcations in epileptic discharges through the brain is a critical area of research at the intersection of neuroscience, mathematics, and computational modeling. Bifurcation theory, a key branch of applied mathematics, plays a significant role in understanding how normal brain activity transitions to epileptic seizures. This transition, viewed as a bifurcation, represents a change in the brain's dynamics leading to altered behavior, involving the study of the brain's dynamical systems and identifying parameters leading to these critical transitions. This approach is pivotal in understanding epileptic seizures and their mechanisms (Engel & Pedley, 2008; Lüders & Noachtar, 2000).

Various mathematical models, such as the Hodgkin-Huxley and FitzHugh-Nagumo models, are frequently used to simulate neuronal activity. These models are instrumental in elucidating the conditions under which neuronal firing patterns change, leading to seizure-like activity (Buzsáki, 2006; Schwartzkroin, 1993). The study also extends to neuronal networks, considering how networks of neurons interact. Changes in how neurons synchronize their activity are crucial in understanding the spread of epileptic discharges across the brain (Scharfman & Buckmaster, 2007; Spencer & Spencer, 1994). Computational models are, therefore, essential in this area of study. They facilitate the simulation of complex neuronal networks and explore how different variables, such as ion channel conductance and synaptic strengths, can lead to bifurcations and seizures (Stafstrom & Carmant, 2015; Moshé et al., 2015). One of the ultimate goals of this research is to predict when a seizure might occur. Understanding the bifurcation points leading to seizures could help develop interventions or treatments to prevent these transitions in brain dynamics (Engel, 2013).

Please observe that the study of bifurcations in epileptic discharges through the brain, intersecting neuroscience, mathematics, and computational modeling, is pivotal for understanding epilepsy. Bifurcation theory, a branch of applied mathematics, is instrumental in examining how normal brain activity transitions to epileptic seizures. This change, often seen as a bifurcation, leads to different behavioral patterns in the brain's dynamics. Because epileptic seizures, characterized by sudden changes in the brain's electrical activity, can be better understood using bifurcation theory.

This approach is crucial in studying the brain's dynamical systems and identifying parameters leading to such bifurcations, offering insights into the transition from a normal state to a seizure state (Fisher et al., 2005; Engel & Pedley, 2008).

The development of a model to simulate saddle-node bifurcation evolving into disseminated epilepsy can be understood through a multidisciplinary lens, incorporating insights from neurophysiology, computational modeling, and neuroscience, as reflected in various scholarly references. This theoretical framework is foundational for modeling epilepsy.

Incorporating Epileptic Dynamics into Models: Adjusting the parameters in these models, such as ion channel conductance or synaptic strength, allows for the simulation of the transition to epilepsy. This approach aligns with the current understanding of epilepsy as a dynamical brain disease characterized by unprovoked spontaneous seizures (Stafstrom & Carmant, 2015; Moshé et al., 2015).

4. Conclusions

Extending the individual neuron model to a network of interconnected neurons is crucial for understanding how seizures propagate. This involves exploring the coupling between neurons and how changes in this coupling can lead to widespread seizure activity (Scharfman & Buckmaster, 2007; Engel, 2013). By employing numerical methods to simulate system dynamics and varying parameters, researchers can identify the critical points leading to seizure-like activity. This process is vital in the quest to predict seizures and develop interventions (Spencer & Spencer, 1994; Engel, 2013).

Nevertheless, to ensure the relevance of these models to actual epileptic dynamics, validation against empirical data, such as EEG recordings, is essential. This step bridges the gap between theoretical models and practical clinical applications (Fisher et al., 2005; Engel, 2013).

In conclusion, the study of bifurcations in epileptic discharges through computational models is an interdisciplinary endeavor that combines insights from neurophysiology, computational neuroscience, and dynamical systems theory. The goal is to develop more effective treatments for epilepsy and enhance our understanding of this complex neurological disorder.

The numerical simulation of the FitzHugh-Nagumo model across a network of neurons, as depicted in the plots, aligns with and is supported by recent advances in the study of neural dynamics and computational neuroscience. The key findings from this simulation can be reinterpreted in the context of these references.

The observation that varying coupling strengths (ranging from no coupling to strong coupling) affect the dynamics of the neurons is consistent with current understanding in the field.

Studies like those by Manley et al. (2024) and Ganguli (2022) emphasize the importance of understanding how neuronal interactions influence overall network behavior, particularly in complex tasks requiring distributed computation across various brain regions.

The increased synchronization between neurons at higher coupling strengths observed in the model reflects the current thinking in neural dynamics research. This phenomenon is indicative of the spread of epileptic activity in the brain, as suggested by research in Nature Neuroscience (Wang, Narain, & Jazayeri, 2017; Breakspear, 2017).

The simulation results provide insights into the initiation and propagation of epileptic discharges in a neural network. This aligns with studies like those by Verhoef & Maunsell (2017) and Pillow & Aoi (2017), highlighting the role of synaptic connectivity changes in the development and spread of epilepsy.

Understanding how network parameters influence seizure-like activity is crucial for developing strategies to predict and control seizures. The identification of critical coupling strengths or network configurations that lead to synchronization could inform therapeutic interventions, similar to the findings in the research by Barral & Reyes (2016) and Kwon, Yang, & O'Connor (2016).

In conclusion, the simulation and its results provide a simplified yet insightful representation of the dynamics of epileptic seizures in neural networks. It highlights the importance of mathematical and computational models in understanding complex neurological phenomena like epilepsy and contributes to the broader field of computational neuroscience and its applications in medicine.

These references collectively emphasize the significance of understanding the dynamics of neural networks, particularly in the context of disorders like epilepsy. They showcase the value of computational modeling in revealing complex interactions and dynamics within neuronal systems, contributing significantly to the field of neuroscience.

Conflicts of Interest

The author claims no conflict of interest.

References

- Barral, J.; Reyes, A.D. Synaptic scaling rule preserves excitatory–inhibitory balance and salient neuronal network dynamics. Nature Neuroscience 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breakspear, M. Dynamic models of large-scale brain activity. Nature Neuroscience 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzsáki, G. Rhythms of the Brain; Oxford University Press: 2006.

- Engel, J. Seizures and Epilepsy; Oxford University Press: 2013.

- Engel, J.; Pedley, T.A. (Eds.) Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2008.

- Fisher, R.S.; Boas WV, E.; Blume, W.; Elger, C.; Genton, P.; Lee, P.; Engel, J. Epileptic Seizures and Epilepsy: Definitions Proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia 2005, 46, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguli, S. Neurophysics: revealing the emergence of cognition from the collective dynamics of interacting neurons. University of California, Berkeley, 2022.

- Kwon, S.E.; Yang, H.; O'Connor, D.H. Sensory and decision-related activity propagate in a cortical feedback loop during touch perception. Nature Neuroscience 2016. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüders, H.O.; Noachtar, S. (Eds.) Epileptic Seizures: Pathophysiology and Clinical Semiology; Churchill Livingstone: 2000.

- Manley, J.; Demas, J.; Kim, H.; Martinez Traub, F.; Vaziri, A. Simultaneous, cortex-wide and cellular-resolution neuronal population dynamics reveal an unbounded scaling of dimensionality with neuron number. bioRxiv 2024.

- Moshé, S.L.; Perucca, E.; Ryvlin, P.; Tomson, T. Epilepsy: New Advances. Lancet 2015, 385, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillow, J.W.; Aoi, M.C. Is population activity more than the sum of its parts? Nature Neuroscience 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharfman, H.E.; Buckmaster, P.S. (Eds.) Issues in Clinical Epileptology: A View from the Bench; Springer: 2007.

- Schwartzkroin, P.A. (Ed.) Epilepsy: Models, Mechanisms and Concepts; Cambridge University Press: 1993.

- Soltesz, I.; Staley, K. Computational Neuroscience in Epilepsy. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S. Cognitive Neurodynamics; Springer: 2024.

- Stafstrom, C.E.; Carmant, L. Seizures and Epilepsy: An Overview for Neuroscientists. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2015, 5, a022426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoef, B.E.; Maunsell, J.H.R. Attention-related changes in correlated neuronal activity arise from normalization mechanisms. Nature Neuroscience 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Narain, D.; Jazayeri, M. Dynamical systems. Nature Neuroscience 2017. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

represents the nonlinear dynamics of the membrane potential.

represents the nonlinear dynamics of the membrane potential.