Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

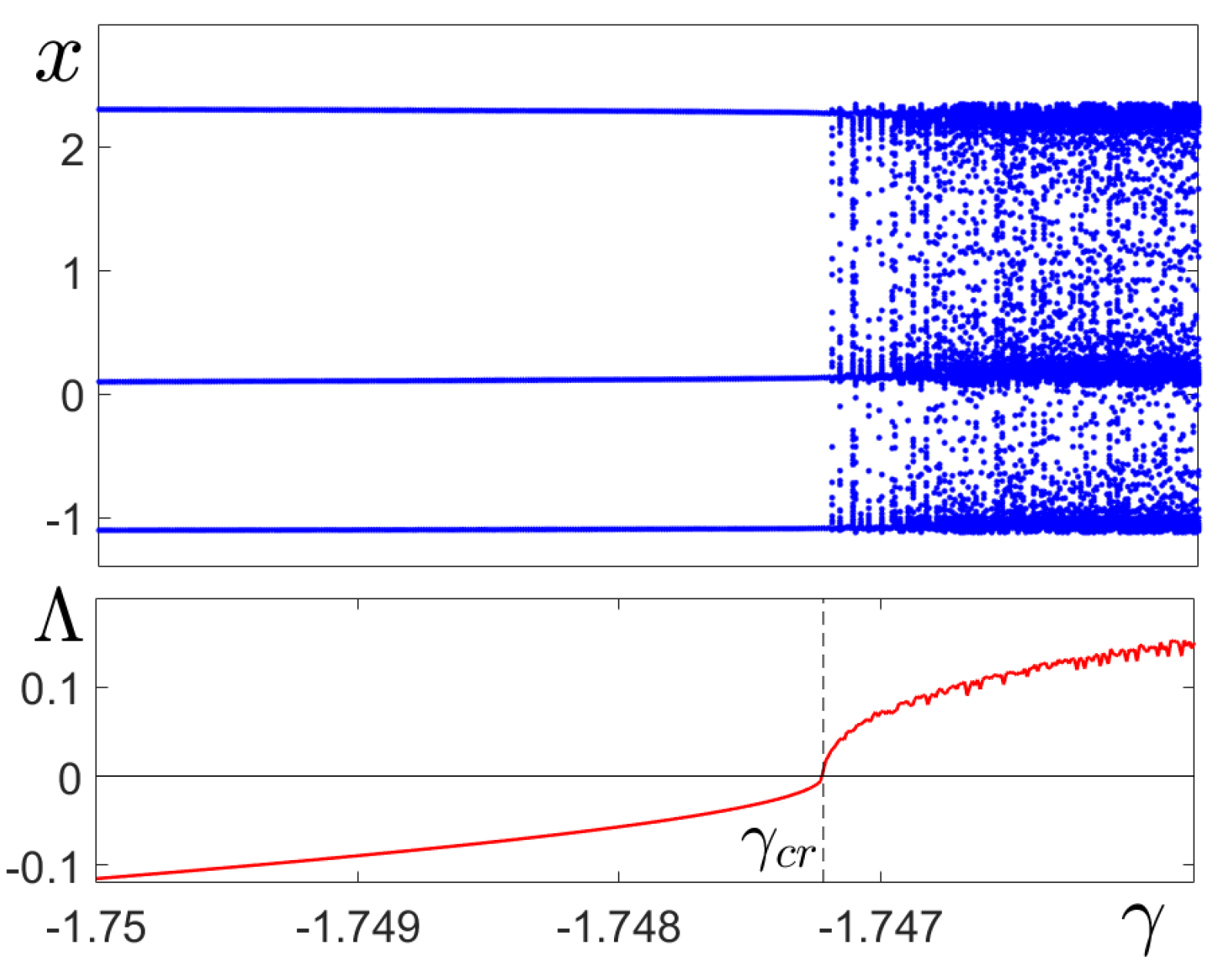

2. Deterministic Model

2.1. Dynamics of isolated neuron

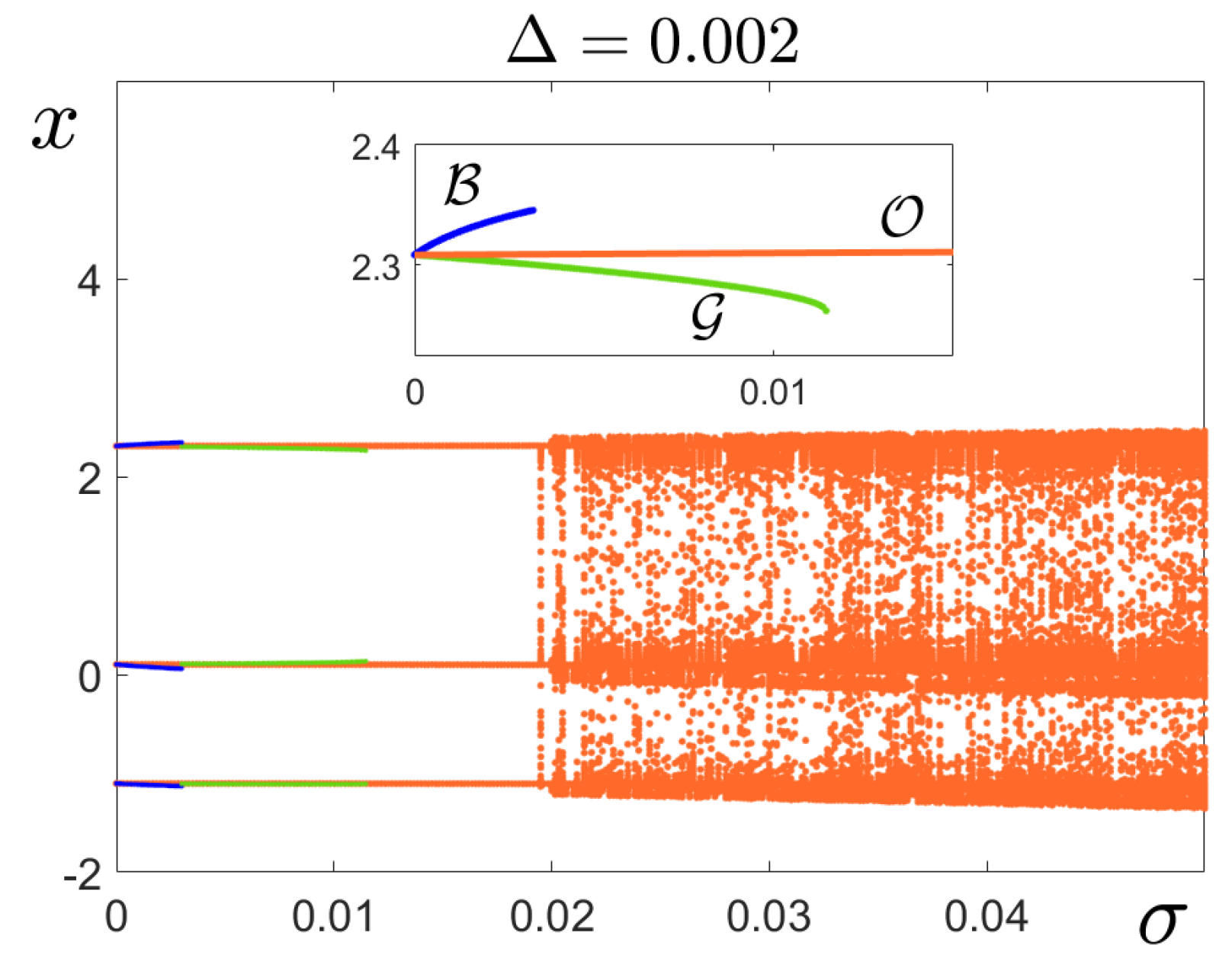

2.2. Dynamics of coupled neurons

3. Stochastic Model

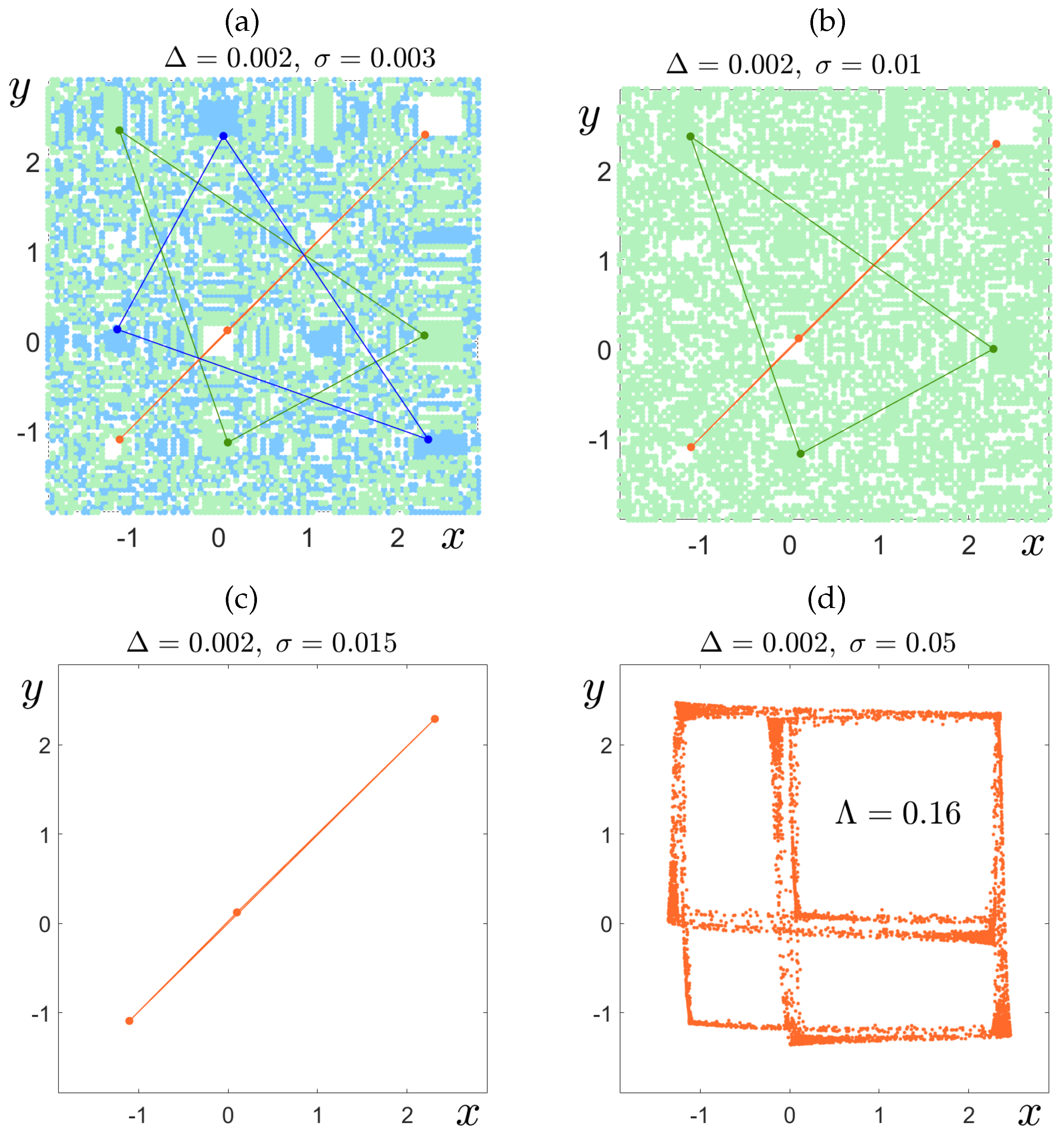

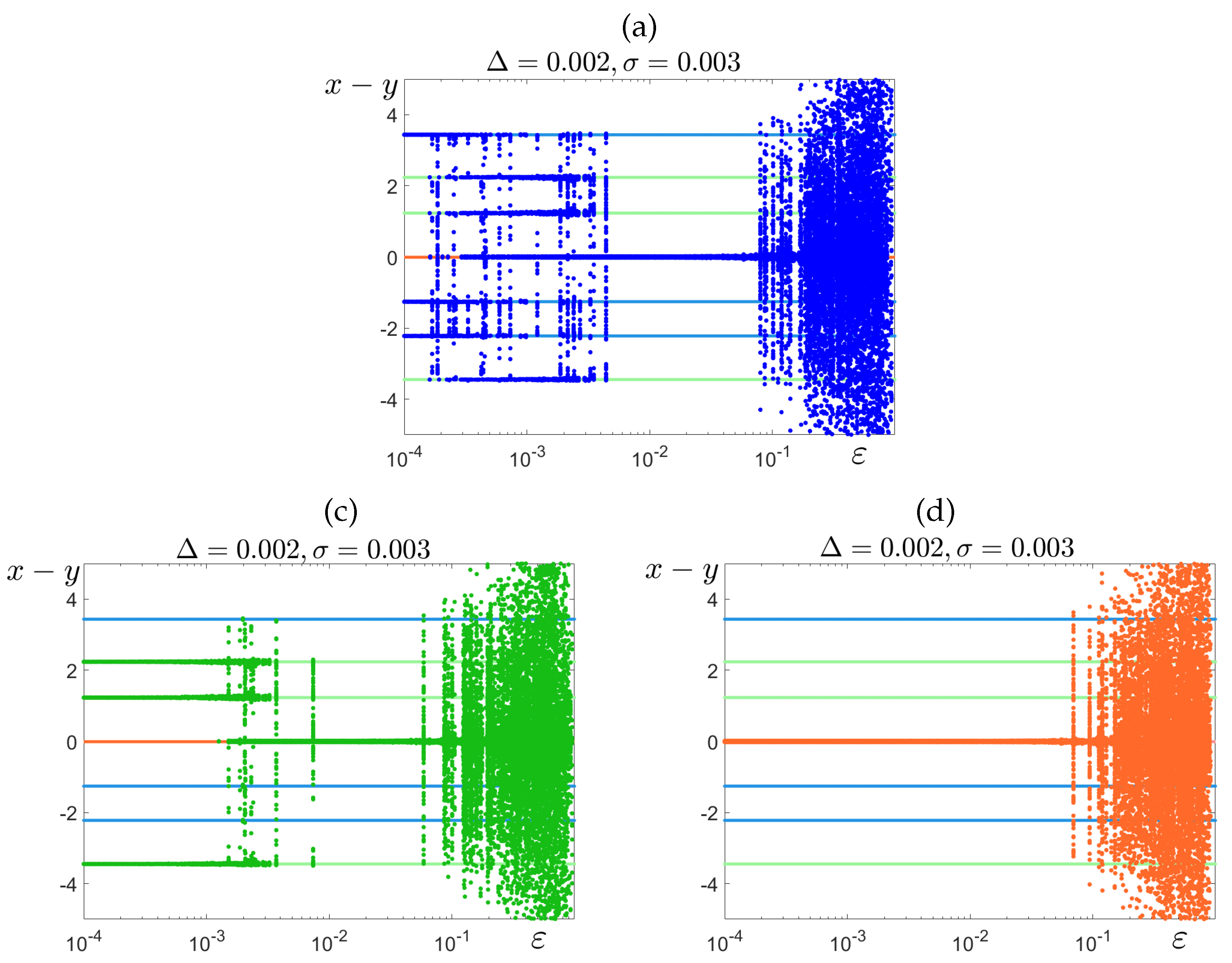

3.1. Stochastic Deformations in the Tristability Case

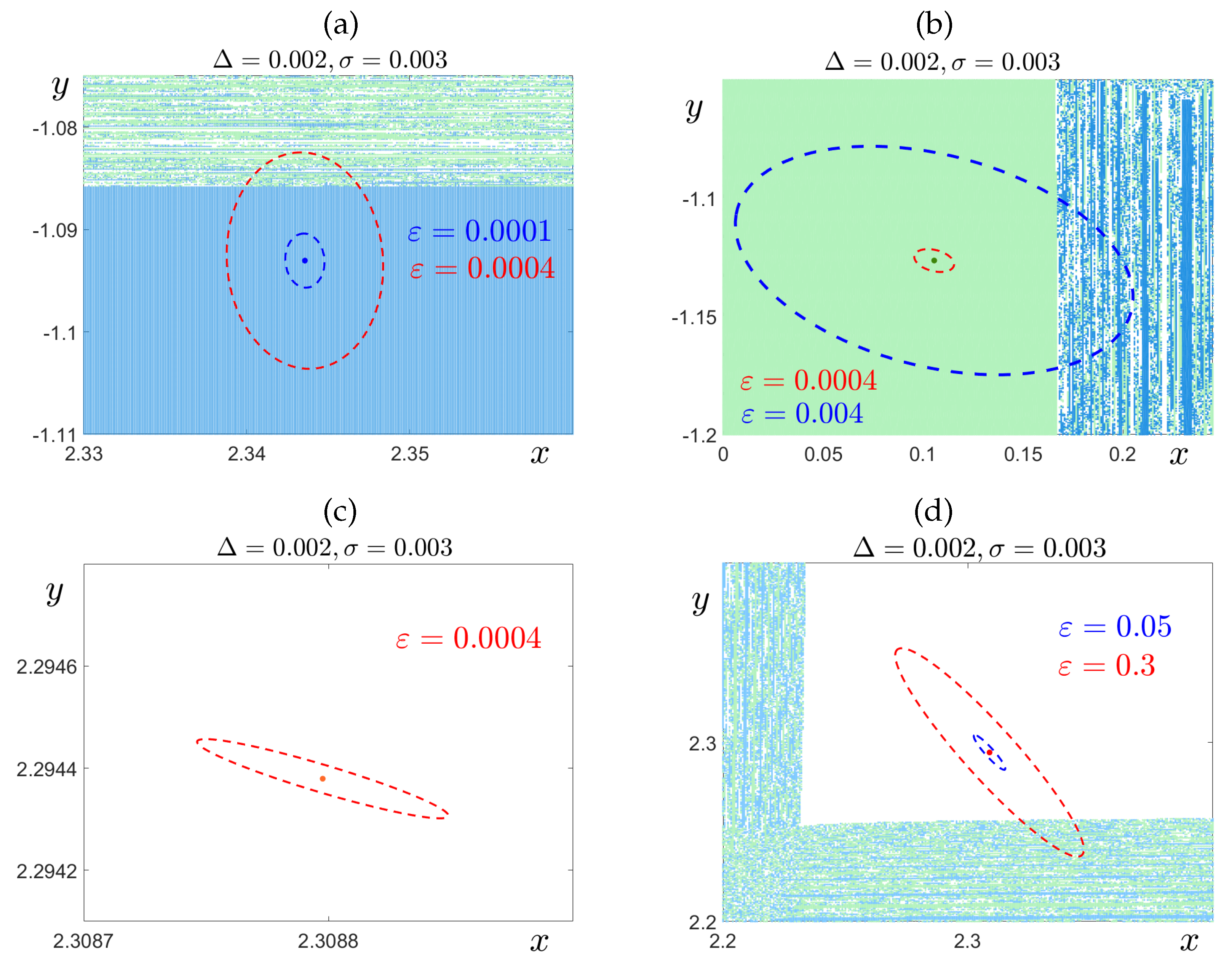

3.2. Confidence Domain Method

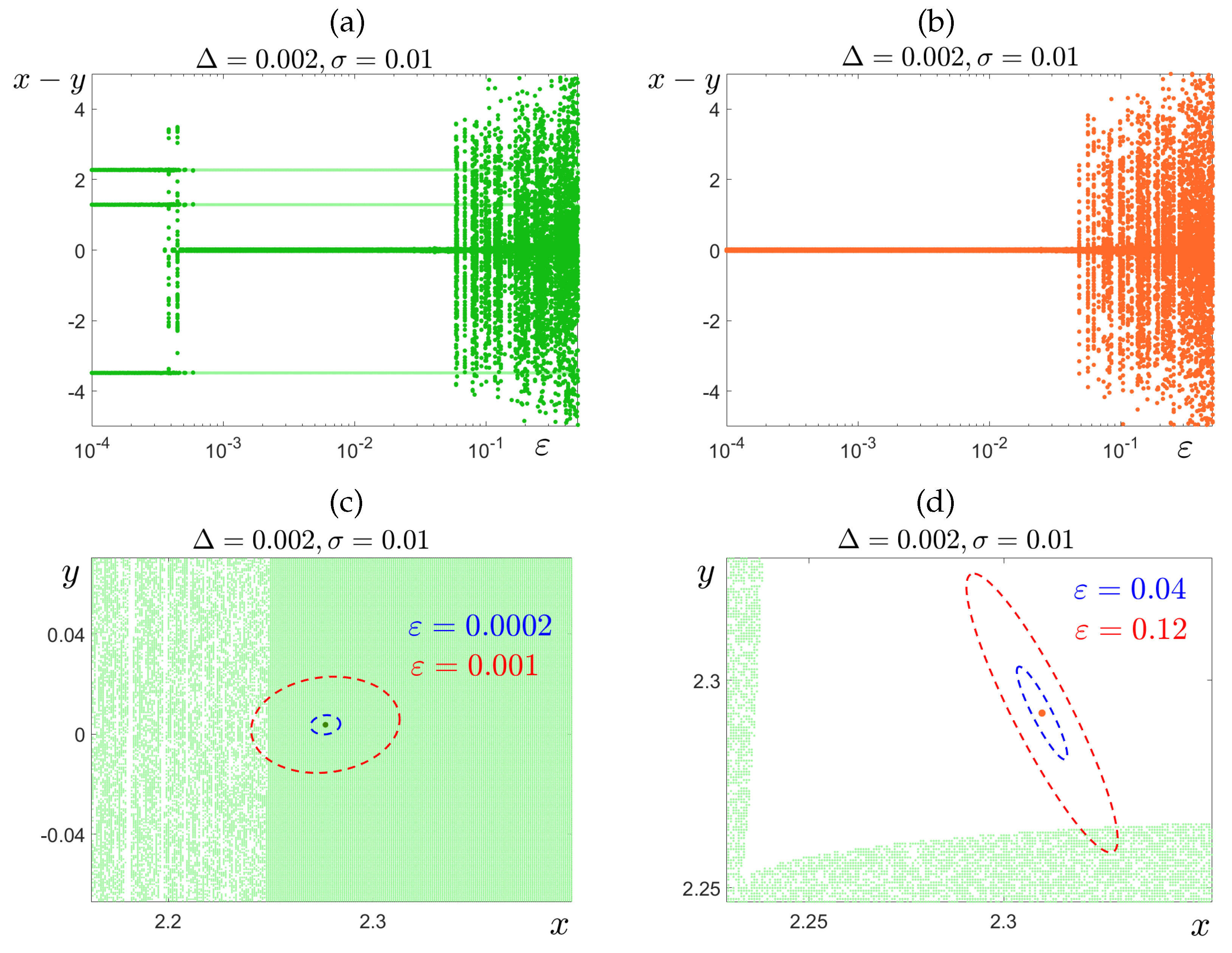

3.3. Stochastic Deformations in the Bistability Case

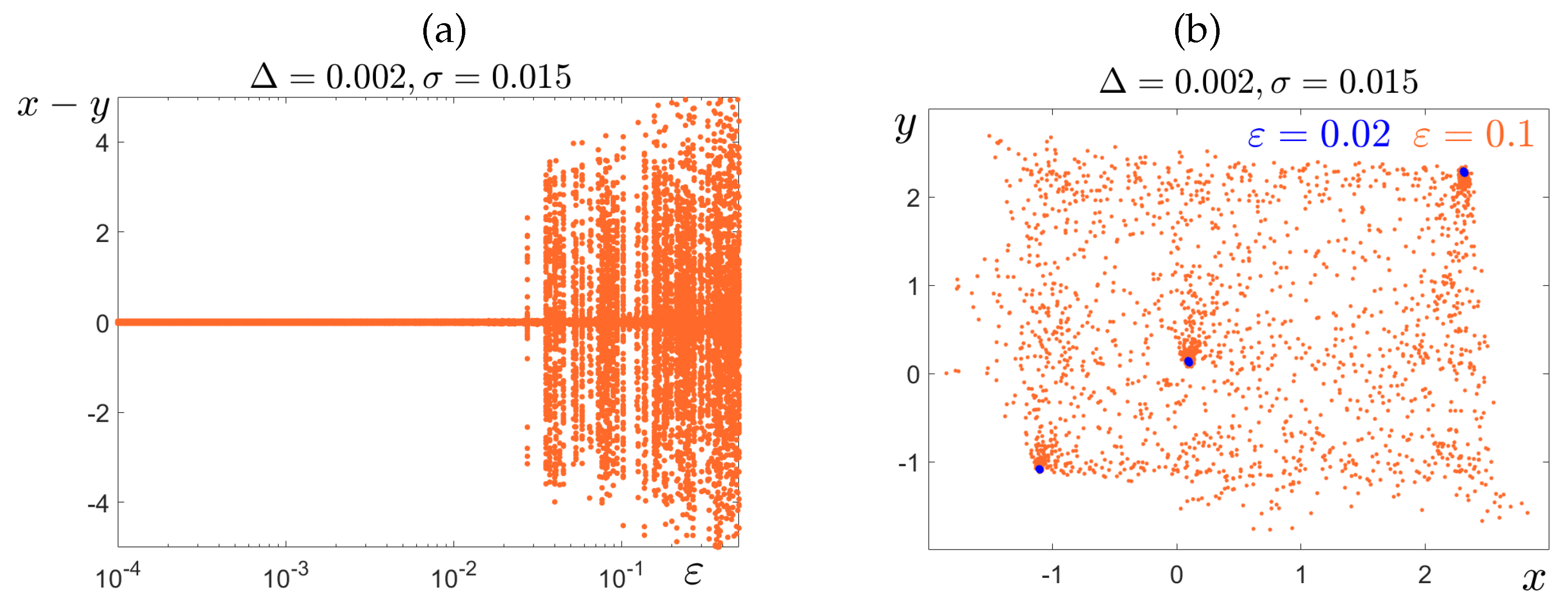

3.4. Stochastic Deformations in the Monostability Case

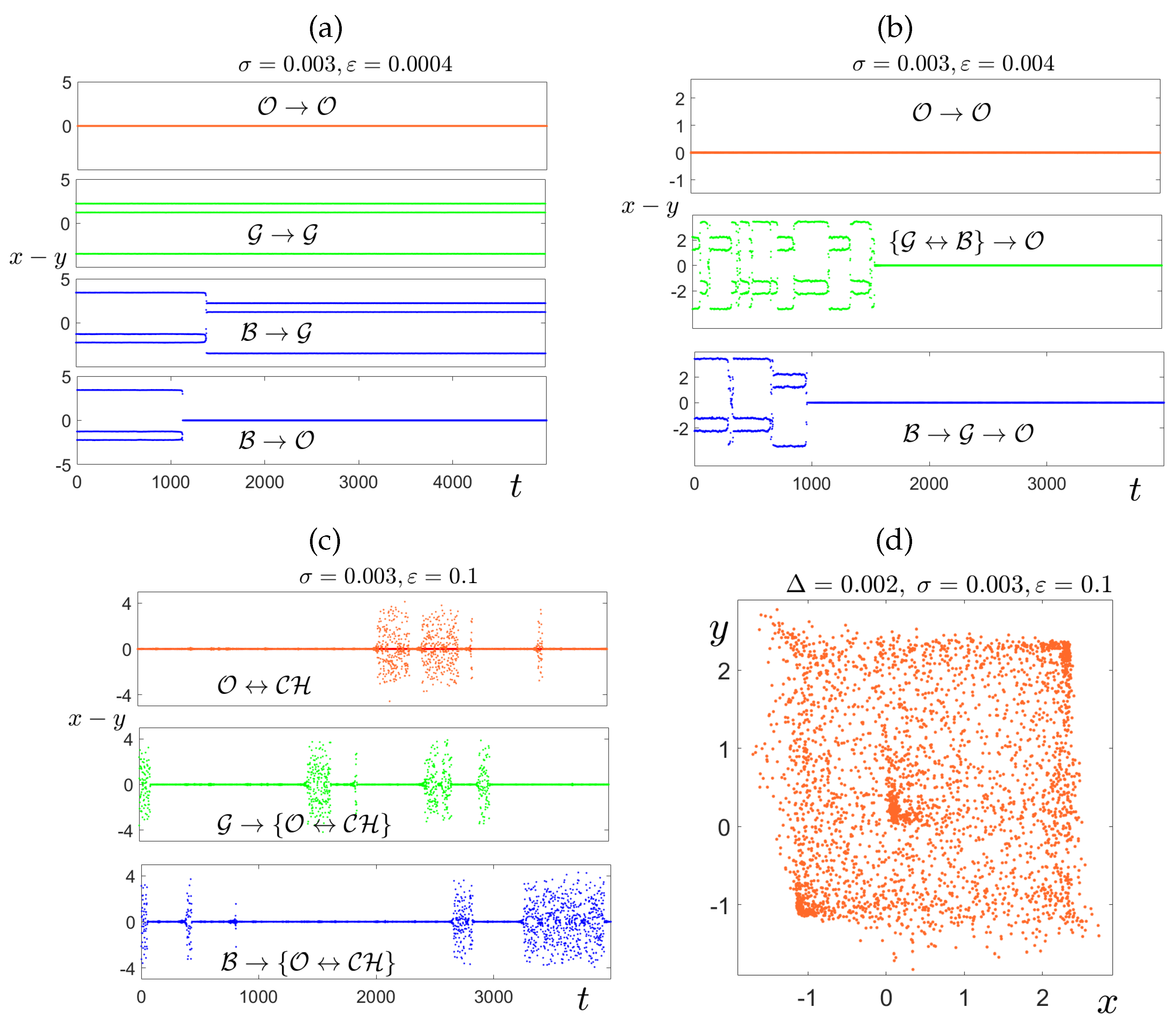

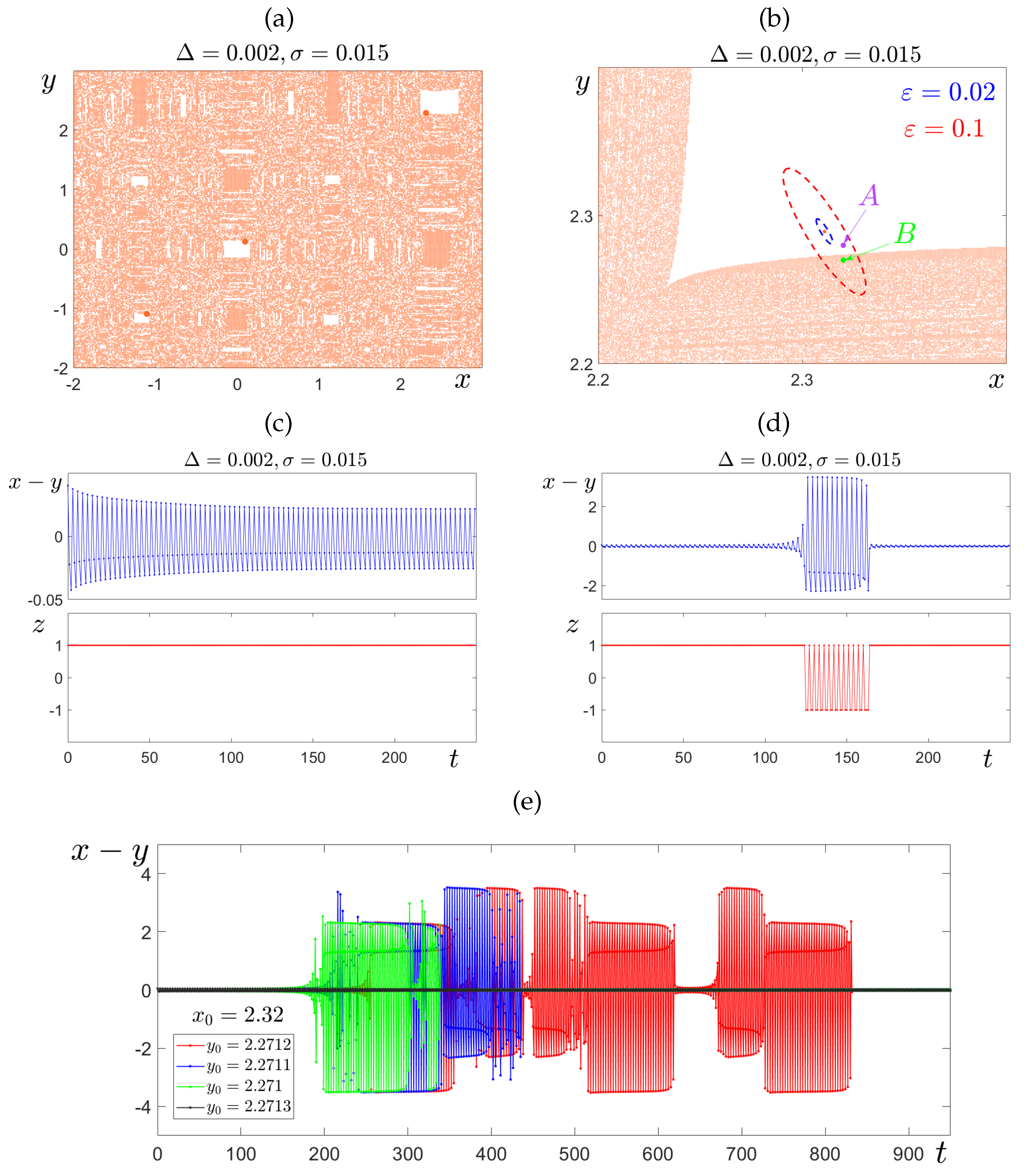

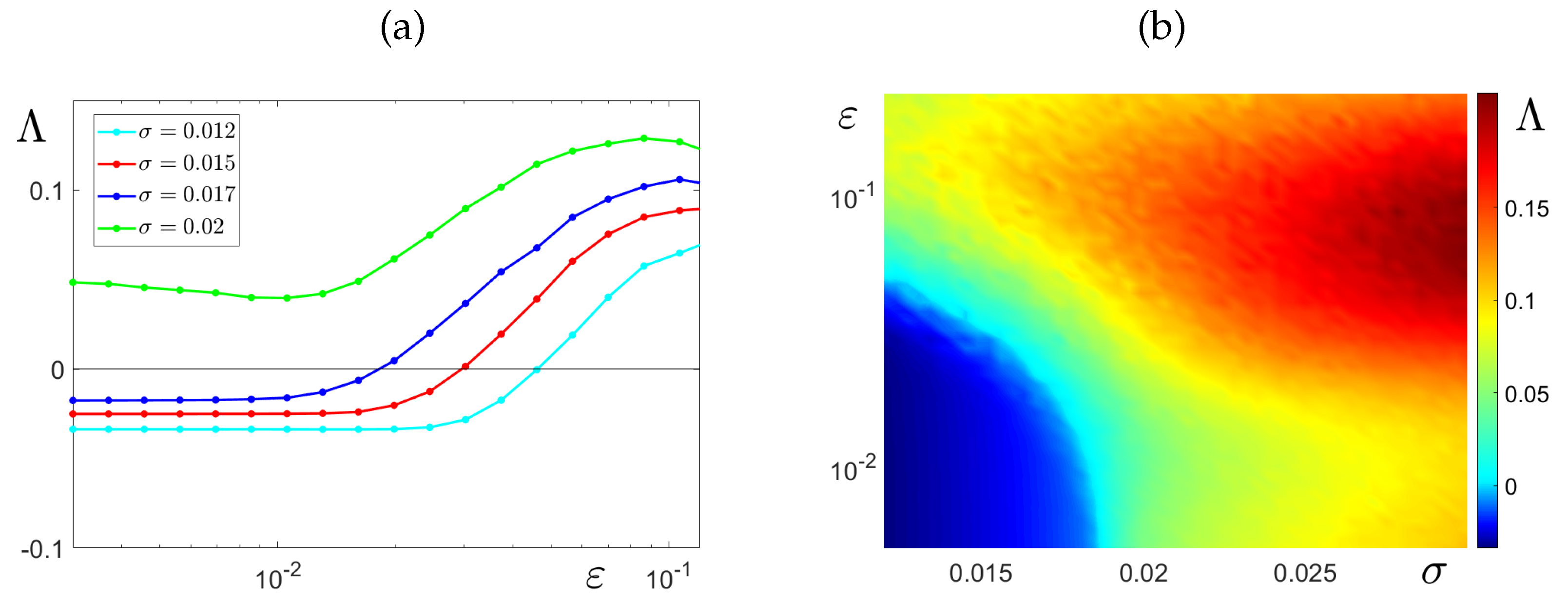

4. Transients and Intermittent Synchronization

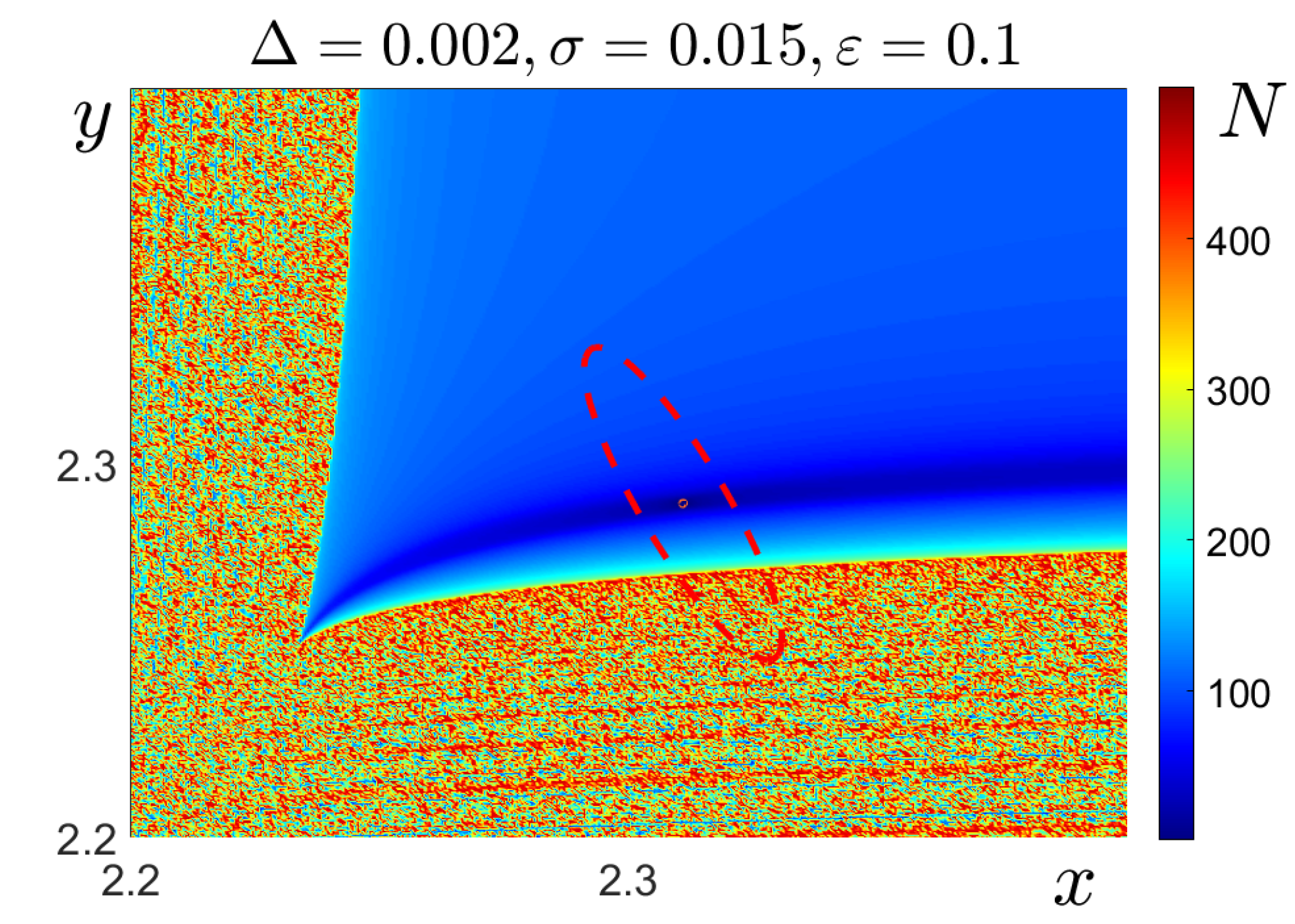

4.1. Short and Long Transients Basins

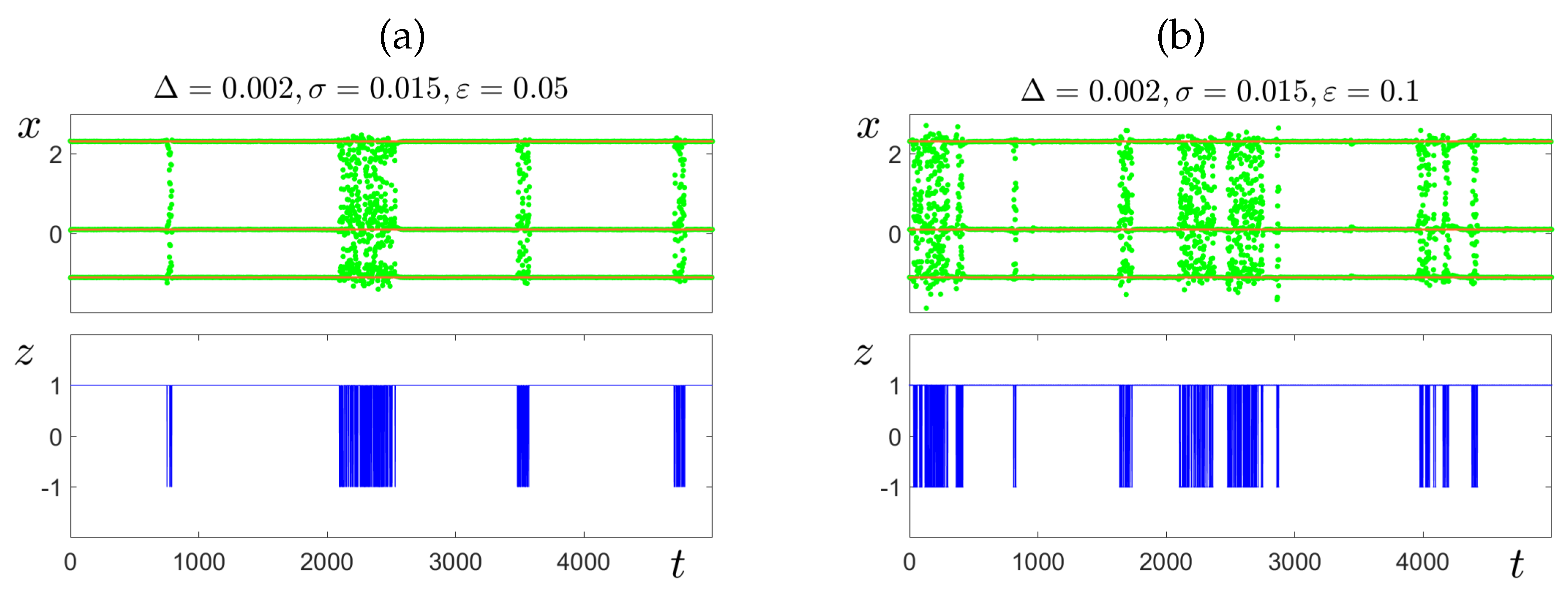

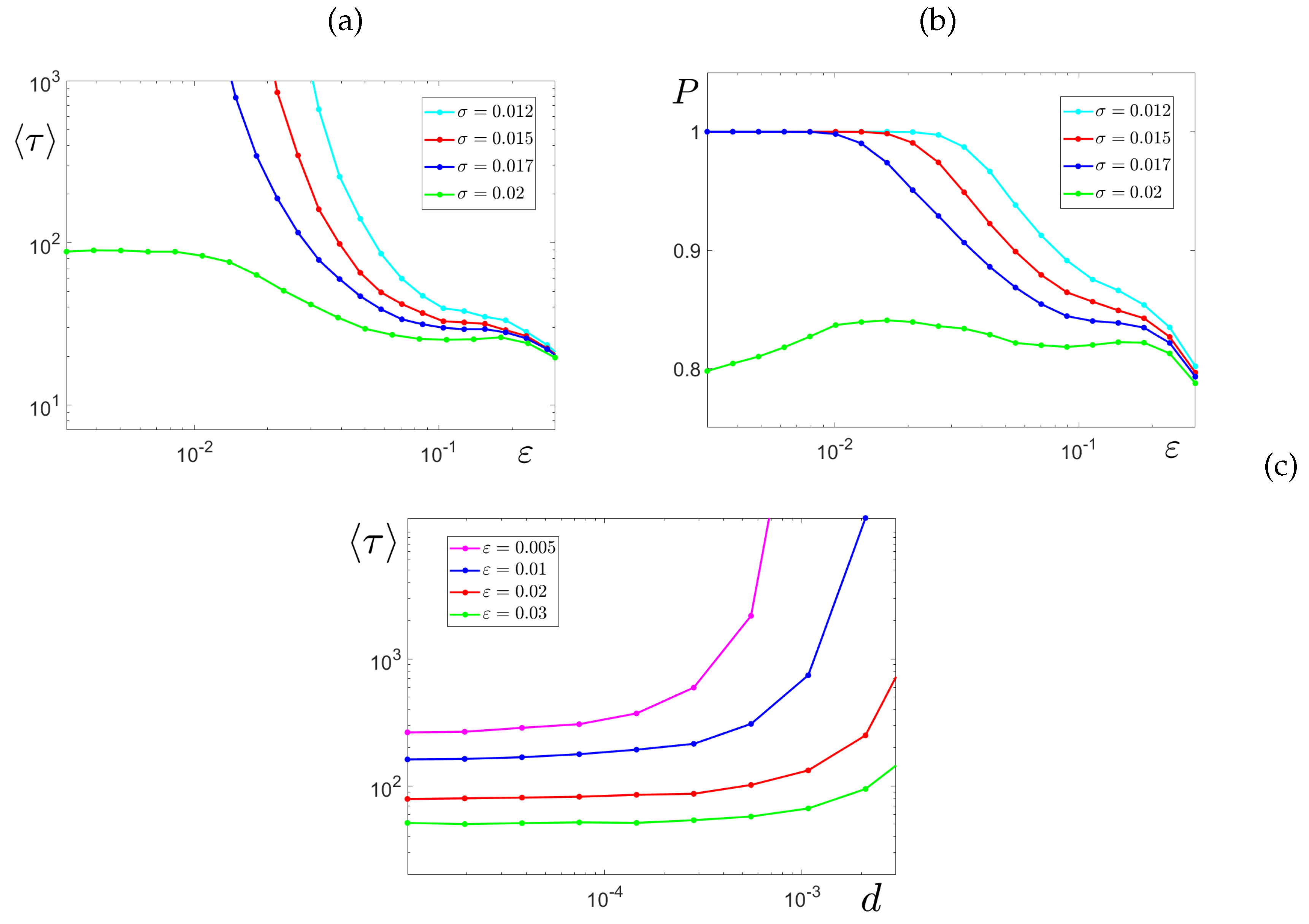

4.2. Intermittent Synchronization

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pikovsky, A.S.; Rosenblum, M.G.; Kurths, J. Synchronization: A Universal Concept in Nonlinear Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Boccaletti, S.; Pisarchik, A.N.; del Genio, C.I.; Amann, A. Synchronization: From Coupled Systems to Complex Networks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D.; Frasca, M.; Rizzo, A.; Majhi, S.; Rakshit, S.; Alfaro-Bittner, K.; Boccaletti, S. The synchronized dynamics of time-varying networks. Phys. Rep. 2022, 949, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, C.Y.; Mao, B.; Lu, J.; Lü, J.; Zhang, Y.C.; Lü, L. Synchronization in multiplex networks. Phys. Rep. 2024, 1060, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destexhe, A.; Rudolph-Lilith, M. Neuronal Noise; Vol. 8, Springer: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, F.; Yudovina, E. Stochastic Networks; Vol. 2, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, A.; Ranft, J.; Hakim, V. Synchronization, stochasticity, and phase waves in neuronal networks with spatially-structured connectivity. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 569644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olin-Ammentorp, W.; Beckmann, K.; Schuman, C.D.; Plank, J.S.; Cady, N.C. Stochasticity and robustness in spiking neural networks. Neurocomputing 2021, 419, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurrer, C.; Schulten, K. Noise-induced synchronous neural oscillations. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 51, 6213–6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, W. Sampled-data intermittent synchronization of complex-valued complex network with actuator saturations. Nonlin. Dyn. 2022, 107, 1023–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarchik, A.N.; Hramov, A.E. Stochastic processes in the brain’s neural network and their impact on perception and decision-making. Physics-Uspekhi 2023, 66, 1224–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, S.; Feudel, U.; Grebogi, C. Preference of attractors in noisy multistable systems. Phys. Rev. E 1999, 59, 5253–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, S.; Feudel, U. Multistability, noise, and attractor hopping: the crucial role of chaotic saddles. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 015207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronovskii, A.A.; Hramov, A.E.; Grubov, V.V.; Moskalenko, O.I.; Sitnikova, E.; Pavlov, A.N. Coexistence of intermittencies in the neuronal network of the epileptic brain. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 93, 032220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarchik, A.N.; Hramov, A.E. Multistability in Physical and Living Systems: Characterization and Applications; Springer: Cham, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rulkov, N.F. Regularization of synchronized chaotic bursts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, P.; Cao, H. Chaos in the Rulkov neuron model based on Marotto’s theorem. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos 2021, 31, 2150233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liang, S. New phenomena in Rulkov map based on Poincaré cross section. Nonlin. Dyn. 2023, 111, 19447–19458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkirtseva, I.; Ryashko, L. Transformations of spike and burst oscillations in the stochastic Rulkov model. Chaos Soliton. Fract. 2023, 170, 113414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Duan, J.; Yue, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, D. Dynamical analysis of the Rulkov model with quasiperiodic forcing. Chaos Soliton. Fract. 2024, 189, 115605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkirtseva, I.A.; Pisarchik, A.N.; Ryashko, L.B. Coexisting attractors and multistate noise-induced intermittency in a cycle ring of Rulkov neurons. Mathematics 2023, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marghoti, G.; Ferrari, F.A.S.; Viana, R.L.; Lopes, S.R.; Prado, T.d.L. Coupling dependence on chaos synchronization process in a network of Rulkov neurons. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos 2023, 33, 2350132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkirtseva, I.A.; Pisarchik, A.N.; Ryashko, L.B. Multistability and stochastic dynamics of Rulkov neurons coupled via a chemical synapse. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2023, 125, 107383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.; Cheng, L.; Cao, H. Complete synchronization of three-layer Rulkov neuron network coupled by electrical and chemical synapses. Chaos 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, B.B. Asymmetric coupling of nonchaotic Rulkov neurons: Fractal attractors, quasimultistability, and final state sensitivity. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 111, 034201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkirtseva, I.; Ryashko, L. Stochastic sensitivity analysis of noise-induced phenomena in discrete systems. In Recent Trends in Chaotic, Nonlinear and Complex Dynamics; World Scientific Series on Nonlinear Science Series B, 2021; chapter 8, pp. 173–192.

- Bashkirtseva, I.; Nasyrova, V.; Ryashko, L. Analysis of noise effects in a map-based neuron model with Canard-type quasiperiodic oscillations. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulat. 2018, 63, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garain, K.; Sarathi Mandal, P. Stochastic sensitivity analysis and early warning signals of critical transitions in a tri-stable prey-predator system with noise. Chaos 2022, 32, 033115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, E.; Holmes, P. Noise-induced intermittency in a model of turbulent boundary layer. Physica D 1989, 37, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, N.; Hammel, S.M.; Heagy, J.F. Effects of additive noise on on-off intermittency. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 72, 3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heagy, J.F.; Platt, N.; Hammel, S.M. Characterization of on-off intermittency. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 48, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisaka, H.; Ouchi, K.; Ohara, H. On-off convection: Noise-induced intermittency near the convection threshold. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 64, 036201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalenko, O.; Koronovskii, A.A.; Zhuravlev, M.O.; Hramov, A.E. Characteristics of noise-induced intermittency. Chaos Soliton. Fract. 2018, 117, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).