Submitted:

07 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

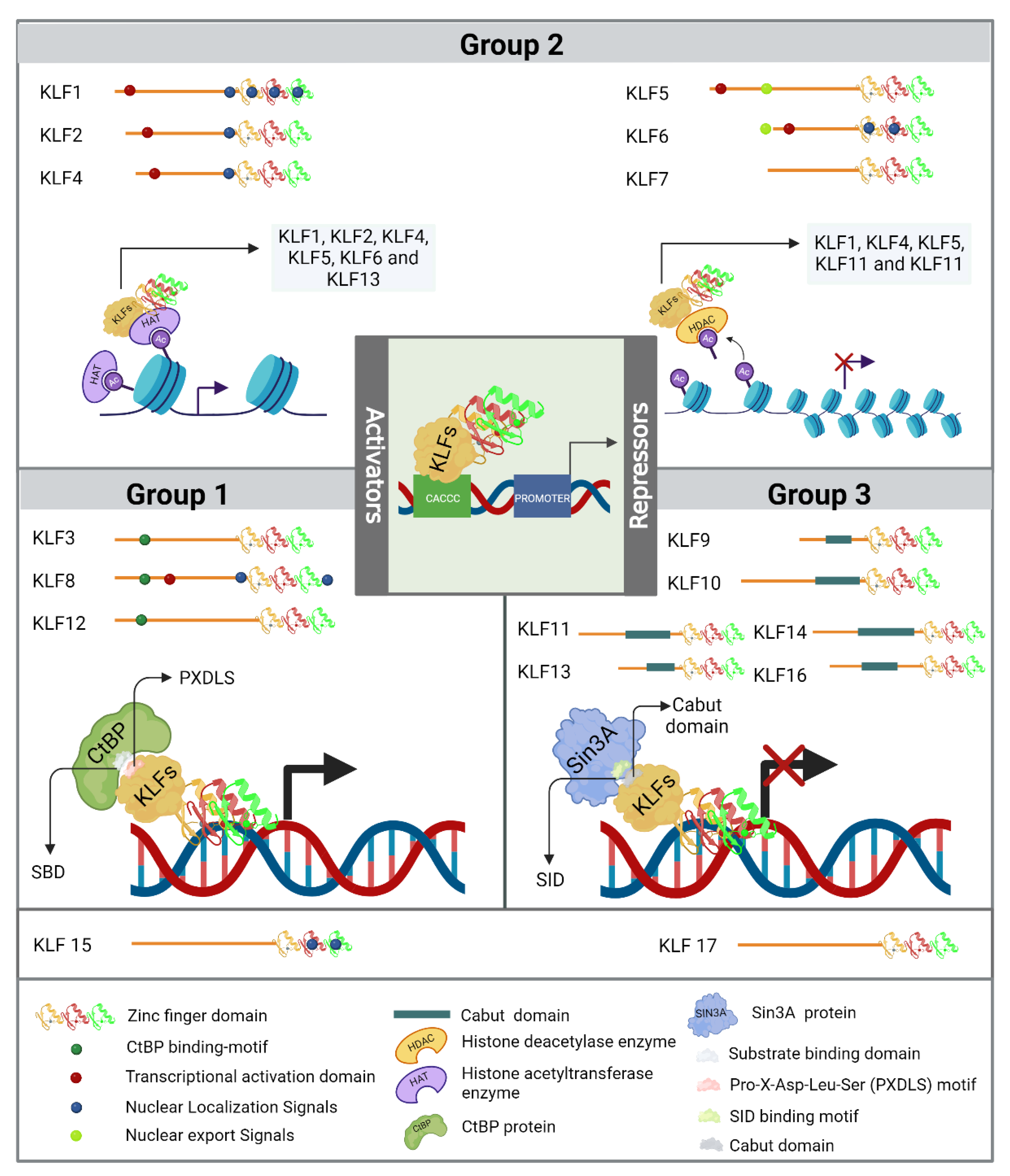

2. Krüppel Like Factors

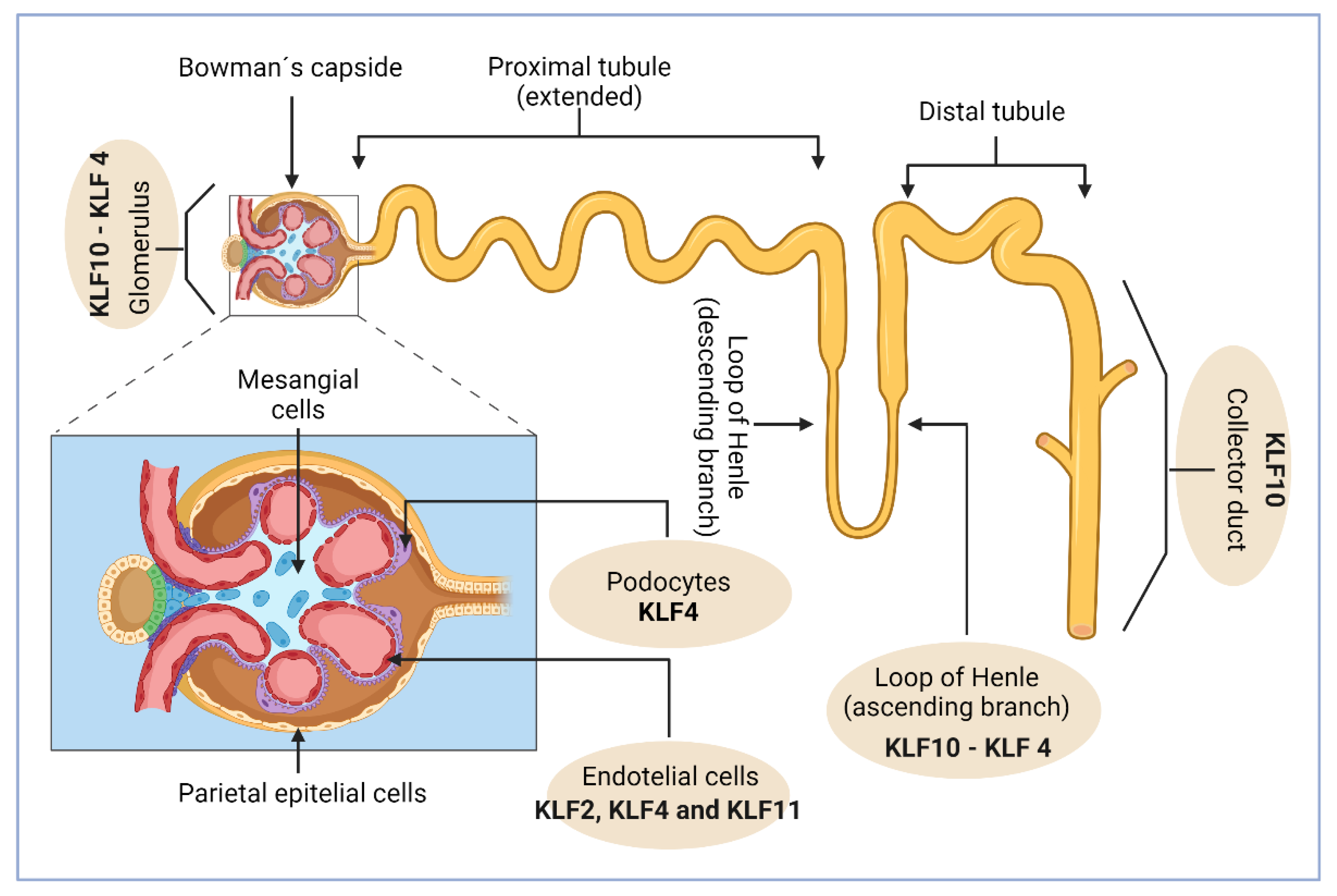

3. KLFs in Kidney Physiology

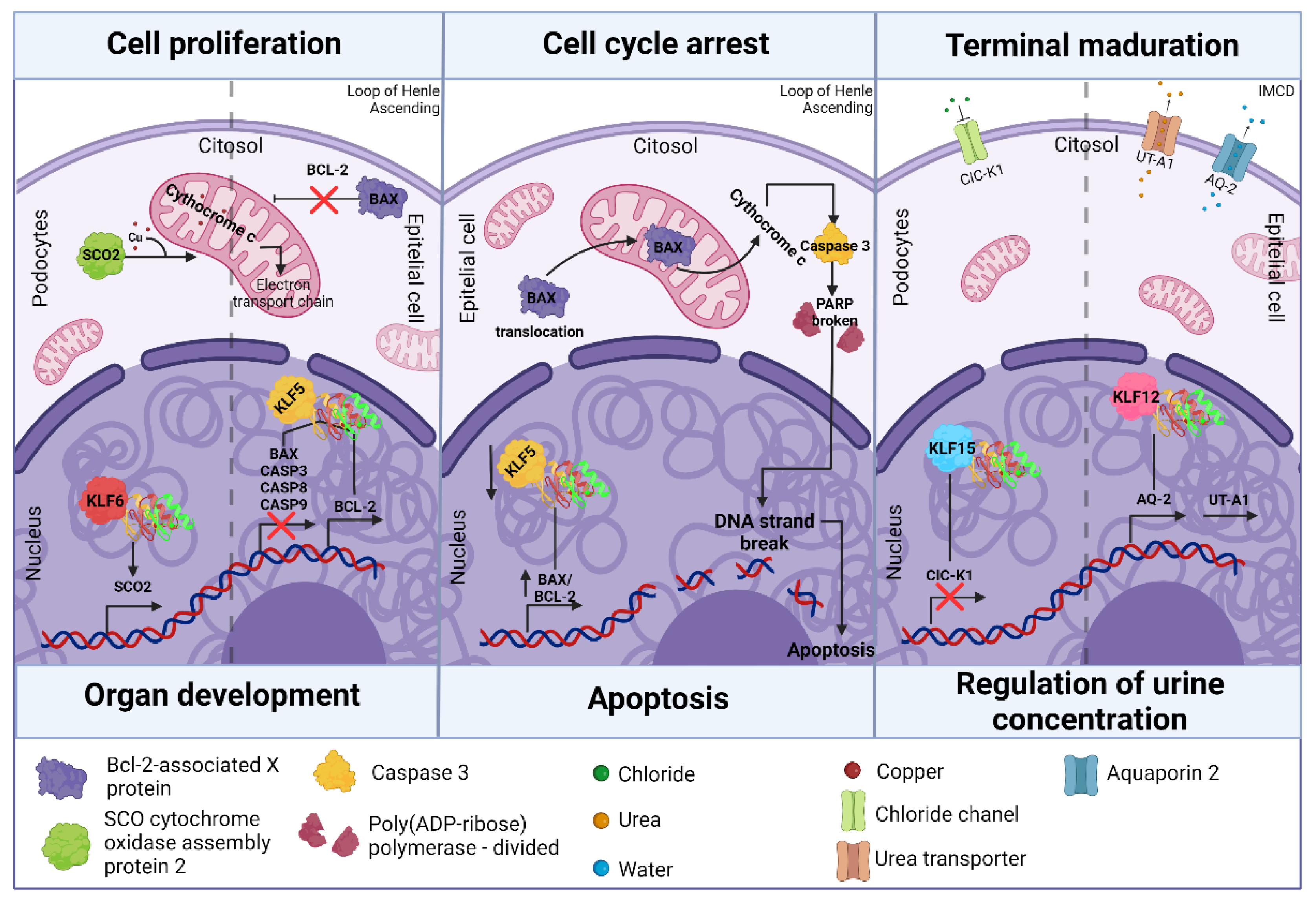

3.1. Klf in Kidney Development

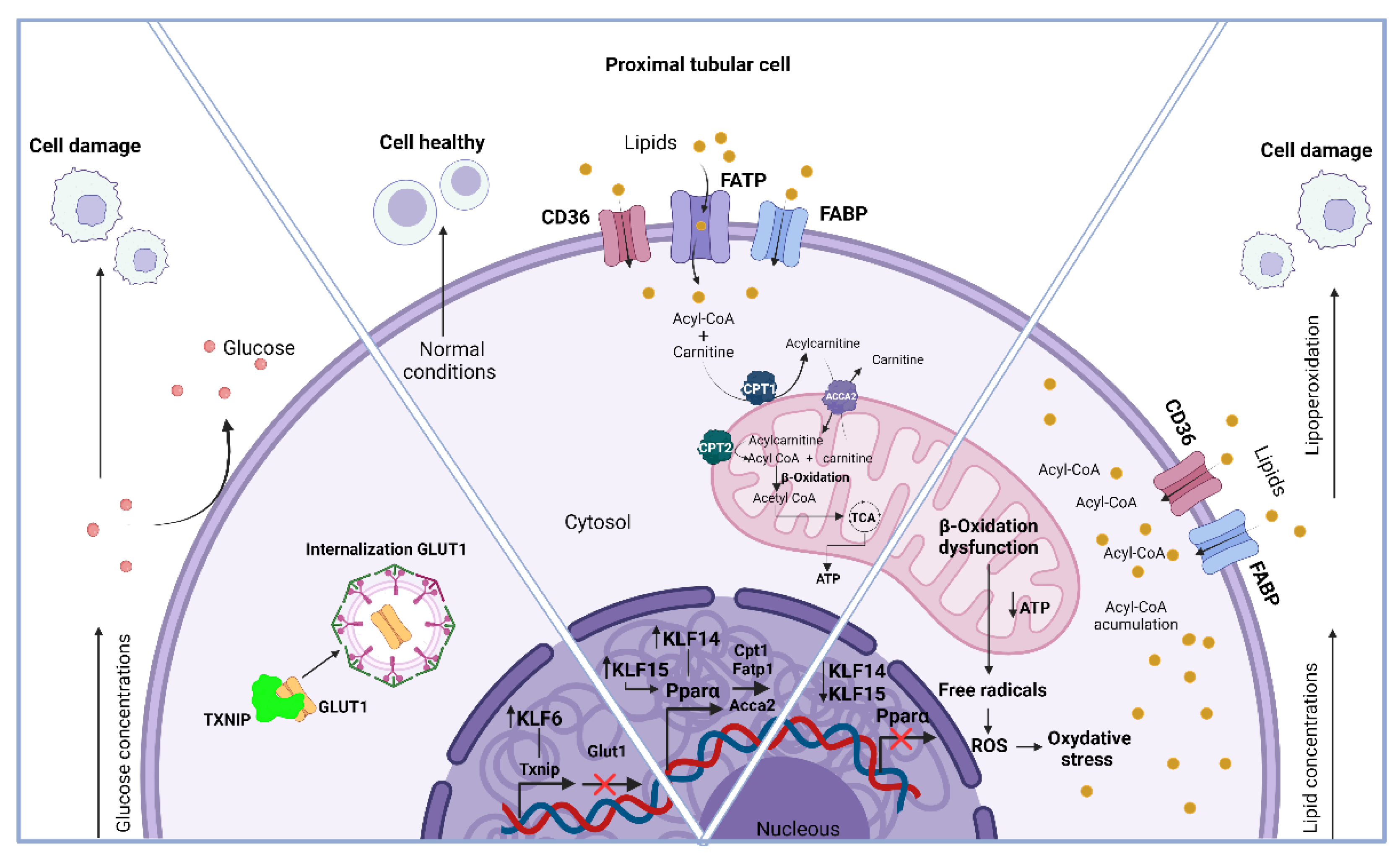

3.2. Klf in Kidney Metabolism

3.3. Klfs in Kidney Disease

5. Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wallace, M.A. Anatomy and Physiology of the Kidney. AORN J 1998, 68, 799–820. [CrossRef]

- Levassort, H.; Essig, M. Le Rein, Son Anatomie et Ses Grandes Fonctions. Soins Gerontol 2024, 29, 10–20. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, V.; Olivero, J. The Kidney as an Endocrine Organ. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 2018, 14, 305. [CrossRef]

- Vaquerizas, J.M.; Kummerfeld, S.K.; Teichmann, S.A.; Luscombe, N.M. A Census of Human Transcription Factors: Function, Expression and Evolution. Nat Rev Genet 2009, 10, 252–263. [CrossRef]

- Chiplunkar, A.R.; Lung, T.K.; Alhashem, Y.; Koppenhaver, B.A.; Salloum, F.N.; Kukreja, R.C.; Haar, J.L.; Lloyd, J.A. Krüppel-Like Factor 2 Is Required for Normal Mouse Cardiac Development. PLoS One 2013, 8, e54891. [CrossRef]

- Oishi, Y.; Manabe, I. Krüppel-Like Factors in Metabolic Homeostasis and Cardiometabolic Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med 2018, 5, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Rane, M.J.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, L. Krϋppel-like Factors (KLFs) in Renal Physiology and Disease. EBioMedicine 2019, 40, 743–750. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, L.; Zhou, W.; Cai, L.; Xu, Z.; Rane, M.J. Roles of Krüppel-like Factor 5 in Kidney Disease. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 2342–2355. [CrossRef]

- Swamynathan, S.K. Krüppel-like Factors: Three Fingers in Control. Hum Genomics 2010, 4, 263–270. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, B.R.; Damery, S.; Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Anderson, N.; Calvert, M.; Cockwell, P.; Ferguson, J.; Horton, M.; Paap, M.C.S.; Sidey-Gibbons, C.; et al. Symptom Burden and Health-Related Quality of Life in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med 2022, 19, e1003954. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Feng, L.; Lu, H.; Wang, X. Krüppel-like Factors in Breast Cancer: Function, Regulation and Clinical Relevance. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 123, 109778. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Han, J.; Dmitrii, G.; Ning, K.; Zhang, X. KLF Transcription Factors in Bone Diseases. J Cell Mol Med 2024, 28. [CrossRef]

- Santoyo-Suarez, M.G.; Mares-Montemayor, J.D.; Padilla-Rivas, G.R.; Delgado-Gallegos, J.L.; Quiroz-Reyes, A.G.; Roacho-Perez, J.A.; Benitez-Chao, D.F.; Garza-Ocañas, L.; Arevalo-Martinez, G.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; et al. The Involvement of Krüppel-like Factors in Cardiovascular Diseases. Life 2023, 13, 420. [CrossRef]

- García-Loredo, J.A.; Santoyo-Suarez, M.G.; Rodríguez-Nuñez, O.; Benitez Chao, D.F.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; Zapata-Morin, P.A.; Padilla-Rivas, G.R.; Islas, J.F. Is the Cis-Element CACCC-Box a Master Regulatory Element during Cardiovascular Disease? A Bioinformatics Approach from the Perspective of the Krüppel-like Family of Transcription Factors. Life 2024, 14, 493. [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Saeki, N.; Ikeda, Y.; Ohba, S. Kruppel-like Factors in Skeletal Physiology and Pathologies. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15174. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.; Fleetwood, J.; Eaton, S.; Crossley, M.; Bao, S. Krüppel-like Transcription Factors: A Functional Family. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology 2008, 40, 1996–2001. [CrossRef]

- Pollak, N.M.; Hoffman, M.; Goldberg, I.J.; Drosatos, K. Krüppel-Like Factors: Crippling and Uncrippling Metabolic Pathways. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2018, 3, 132–156. [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.T.; Pevsner, J.; Yang, V.W. The Biology of the Mammalian Krüppel-like Family of Transcription Factors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2000, 32, 1103–1121. [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, J.; Cook, T.; Urrutia, R. Sp1- and Krüppel-like Transcription Factors. Genome Biol 2003, 4, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Andrés García-Loredo, J.; Santoyo-Suarez, M.G.; Rodríguez-Núñez, O.; Francisco Benitez Chao, D.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; Zapata-Morin, P.A.; Padilla-Rivas, G.R.; Islas, J.F. In the Cis-Element CACCC-Box a Master Regulatory Element during Cardiovascular Disease? A Bioinformatics Approach from the Perspective of the Kruppel-like Family of Transcription Factors. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, M.B. MicroRNAs and the Regulation of Aldosterone Signaling in the Kidney. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2015, 308, C521–C527. [CrossRef]

- Uchida, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Ito, H.; Saitoh-Ohara, F.; Inazawa, J.; Yokoyama, K.K.; Sasaki, S.; Marumo, F. Transcriptional Regulation of the CLC-K1 Promoter by Myc-Associated Zinc Finger Protein and Kidney-Enriched Krüppel-Like Factor, a Novel Zinc Finger Repressor. Mol Cell Biol 2000, 20, 7319–7331. [CrossRef]

- Mallipattu, S.K.; Horne, S.J.; D’Agati, V.; Narla, G.; Liu, R.; Frohman, M.A.; Dickman, K.; Chen, E.Y.; Ma’ayan, A.; Bialkowska, A.B.; et al. Krüppel-like Factor 6 Regulates Mitochondrial Function in the Kidney. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2015, 125, 1347–1361. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Chou, C.-L.; Knepper, M.A. Deep Sequencing in Microdissected Renal Tubules Identifies Nephron Segment–Specific Transcriptomes. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2015, 26, 2669–2677. [CrossRef]

- Balzer, M.S.; Rohacs, T.; Susztak, K. How Many Cell Types Are in the Kidney and What Do They Do? Annu Rev Physiol 2022, 84, 507–531. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Deile, J.; Schiffer, M. Podocytes from the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Point of View. Pflugers Arch 2017, 469, 1007–1015. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Bunda, P.; Ishibe, S. Podocyte Endocytosis in Regulating the Glomerular Filtration Barrier. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Natesan, V.; Shi, H.; Dong, F.; Kawanami, D.; Mahabeleshwar, G.H.; Atkins, G.B.; Nayak, L.; Cui, Y.; Finigan, J.H.; et al. Kruppel-Like Factor 2 Regulates Endothelial Barrier Function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010, 30, 1952–1959. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Sasamura, H.; Nakamura, M.; Azegami, T.; Oguchi, H.; Sakamaki, Y.; Itoh, H. KLF4-Dependent Epigenetic Remodeling Modulates Podocyte Phenotypes and Attenuates Proteinuria. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2014, 124, 2523–2537. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Han, S.M.; Kim, J.-E.; Chung, K.-Y.; Han, K.-H. Expression of E-Cadherin in Pig Kidney. J Vet Sci 2013, 14, 381. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, J.C. An Update: The Role of Nephrin inside and Outside the Kidney. Sci China Life Sci 2015, 58, 649–657. [CrossRef]

- Huber, T.B.; Schermer, B.; Benzing, T. Podocin Organizes Ion Channel-Lipid Supercomplexes: Implications for Mechanosensation at the Slit Diaphragm. Nephron Exp Nephrol 2007, 106, e27–e31. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, M.I.; Wafai, R.; Wong, M.K.; Newgreen, D.F.; Thompson, E.W.; Waltham, M. Vimentin and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Breast Cancer – Observations in Vitro and in Vivo. Cells Tissues Organs 2007, 185, 191–203. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.-M. α-Smooth Muscle Actin and ACTA2 Gene Expressions in Vasculopathies. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Cardiovascular 2015. [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.P.; Quaggin, S.E. The Cell Biology of Renal Filtration. Journal of Cell Biology 2015, 209, 199–210. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Lee, K.; He, J.C. Role of Krüppel-like Factor-2 in Kidney Disease. Nephrology 2018, 23, 53–56. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Yamashita, M.; Iwai, M.; Hayashi, M. Endothelial Krüppel-Like Factor 4 Mediates the Protective Effect of Statins against Ischemic AKI. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2016, 27, 1379–1388. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Han, Z.; Dong, J.; Pang, D.; Fu, Y.; Li, L. KLF4 Alleviates Cerebral Vascular Injury by Ameliorating Vascular Endothelial Inflammation and Regulating Tight Junction Protein Expression Following Ischemic Stroke. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Pollak, M.R.; Quaggin, S.E.; Hoenig, M.P.; Dworkin, L.D. The Glomerulus. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2014, 9, 1461–1469. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, R.A.; Lopez, M.L.S.S. Plasticity of Renin Cells in the Kidney Vasculature. Curr Hypertens Rep 2017, 19, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-H. Mesangial Cells and Renal Fibrosis. In; 2019; pp. 165–194. [CrossRef]

- Falkson, S.R.; Bordoni, B. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Bowman Capsule; 2024;

- Kimura, T.; Isaka, Y.; Yoshimori, T. Autophagy and Kidney Inflammation. Autophagy 2017, 13, 997–1003. [CrossRef]

- Mreich, E.; Chen, X.; Zaky, A.; Pollock, C.A.; Saad, S. The Role of Krüppel-like Factor 4 in Transforming Growth Factor- β –Induced Inflammatory and Fibrotic Responses in Human Proximal Tubule Cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2015, 42, 680–686. [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzo, S.B.; Vrieze, A.M.; Johnson, R.A.; Lien, K.R.; Nath, K.A.; Garovic, V.D.; Khazaie, K.; Grande, J.P. KLF11 Deficiency Enhances Chemokine Generation and Fibrosis in Murine Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0266454. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, G.; Gu, X.; Fu, L.; Mei, C. Kruppel-Like Factor 15 Modulates Renal Interstitial Fibrosis by ERK/MAPK and JNK/MAPK Pathways Regulation. Kidney Blood Press Res 2013, 37, 631–640. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Skoultchi, A.I. Coordinating Cell Proliferation and Differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2001, 11, 91–97. [CrossRef]

- El-Dahr, S.S.; Aboudehen, K.; Saifudeen, Z. Transcriptional Control of Terminal Nephron Differentiation. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2008, 294, F1273–F1278. [CrossRef]

- Rao, L.; White, E. Bcl-2 and the ICE Family of Apoptotic Regulators: Making a Connection. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1997, 7, 52–58. [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, A.; Nebreda, A.R. Mechanisms and Functions of P38 MAPK Signalling. Biochemical Journal 2010, 429, 403–417. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ma, L.; Cai, C.; Gong, X. Caffeine Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Suppressing MAPK/NF-ΚB and A2aR Signaling in LPS-Induced THP-1 Macrophages. Int J Biol Sci 2019, 15, 1571–1581. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, Y.; LIU, K.; ZHANG, Y.; QI, J.; LU, B.; SHI, C.; YIN, Y.; CAI, W.; LI, W. ABL-N May Induce Apoptosis of Human Prostate Cancer Cells through Suppression of KLF5, ICAM-1 and Stat5b, and Upregulation of Bax/Bcl-2 Ratio: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Oncol Rep 2015, 34, 2953–2960. [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne, J.O.; Zhang, H.; Zeid, A.M.; Strittmatter, K.; Rocha, A.D.; Williams, T.; Zhang, S.; Marneros, A.G. Transcription Factors AP-2α and AP-2β Regulate Distinct Segments of the Distal Nephron in the Mammalian Kidney. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2226. [CrossRef]

- Suda, S.; Rai, T.; Sohara, E.; Sasaki, S.; Uchida, S. Postnatal Expression of KLF12 in the Inner Medullary Collecting Ducts of Kidney and Its Trans-Activation of UT-A1 Urea Transporter Promoter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 344, 246–252. [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-L.; Hwang, G.; Hageman, D.J.; Han, L.; Agrawal, P.; Pisitkun, T.; Knepper, M.A. Identification of UT-A1- and AQP2-Interacting Proteins in Rat Inner Medullary Collecting Duct. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2018, 314, C99–C117. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Pace, J.; Li, Z.; Ma’ayan, A.; Wang, Z.; Revelo, M.P.; Chen, E.; Gu, X.; Attalah, A.; Yang, Y.; et al. Podocyte-Specific Induction of Krüppel-Like Factor 15 Restores Differentiation Markers and Attenuates Kidney Injury in Proteinuric Kidney Disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2018, 29, 2529–2545. [CrossRef]

- Saifudeen, Z.; Dipp, S.; Fan, H.; El-Dahr, S.S. Combinatorial Control of the Bradykinin B2 Receptor Promoter by P53, CREB, KLF-4, and CBP: Implications for Terminal Nephron Differentiation. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2005, 288, F899–F909. [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Shen, C.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X.; Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, C.; Zhong, C.; Gao, Z.; Miao, W.; et al. Hepatic Krüppel-like Factor 16 (KLF16) Targets PPARα to Improve Steatohepatitis and Insulin Resistance. Gut 2021, 70, 2183–2195. [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, C.E.; Foster, J.E.; Ramdath, D.D. A Maternal High-Fat, High-Sucrose Diet Alters Insulin Sensitivity and Expression of Insulin Signalling and Lipid Metabolism Genes and Proteins in Male Rat Offspring: Effect of Folic Acid Supplementation. British Journal of Nutrition 2017, 118, 580–588. [CrossRef]

- Oishi, Y.; Manabe, I.; Tobe, K.; Ohsugi, M.; Kubota, T.; Fujiu, K.; Maemura, K.; Kubota, N.; Kadowaki, T.; Nagai, R. SUMOylation of Krüppel-like Transcription Factor 5 Acts as a Molecular Switch in Transcriptional Programs of Lipid Metabolism Involving PPAR-δ. Nat Med 2008, 14, 656–666. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-L.; Lu, X.-J.; Zou, K.-L.; Ye, K. Krüppel-like Factor 2 Promotes Liver Steatosis through Upregulation of CD36. J Lipid Res 2014, 55, 32–40. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Q.; Jiao, T.; Cui, A.; Sun, X.; Fang, W.; Xie, L.; Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Chang, Y. Involvement of KLF11 in Hepatic Glucose Metabolism in Mice via Suppressing of PEPCK-C Expression. PLoS One 2014, 9, e89552. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Hong, X.; He, X.; Lin, J.; Fan, S.; Wu, J.; Liang, Z.; Chen, S.; Yan, L.; Ren, M.; et al. Intermittent Fasting–Improved Glucose Homeostasis Is Not Entirely Dependent on Caloric Restriction in Db/Db Male Mice. Diabetes 2024, 73, 864–878. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Meng, S.; Xiang, M.; Ma, H. Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase in Cell Metabolism: Roles and Mechanisms beyond Gluconeogenesis. Mol Metab 2021, 53, 101257. [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.C.; Arany, Z. Genetic Models of PGC-1 and Glucose Metabolism and Homeostasis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2014, 15, 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, K.; Takeda, J.; Horikawa, Y. Krüppel-like Factor-10 Is Directly Regulated by Carbohydrate Response Element-Binding Protein in Rat Primary Hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 412, 638–643. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, K.; Hu, B.; Cai, Z.; Li, J.; Tao, H.; Cao, J. Fatty Acid Binding Protein 5 Promotes the Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells by Degradation of Krüppel-like Factor 9 Mediated by MiR-889-5p via CAMP-Response Element Binding Protein. Cancer Biol Ther 2022, 23, 424–438. [CrossRef]

- Brey, C.W.; Nelder, M.P.; Hailemariam, T.; Gaugler, R.; Hashmi, S. Krüppel-like Family of Transcription Factors: An Emerging New Frontier in Fat Biology. Int J Biol Sci 2009, 622–636. [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Chen, X.; Holian, J.; Tan, C.Y.R.; Kelly, D.J.; Pollock, C.A. Transcription Factors Krüppel-Like Factor 6 and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ Mediate High Glucose-Induced Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein. Am J Pathol 2009, 175, 1858–1867. [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zheng, B.; Shaywitz, A.; Dagon, Y.; Tower, C.; Bellinger, G.; Shen, C.-H.; Wen, J.; Asara, J.; McGraw, T.E.; et al. AMPK-Dependent Degradation of TXNIP upon Energy Stress Leads to Enhanced Glucose Uptake via GLUT1. Mol Cell 2013, 49, 1167–1175. [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.; Pan, S.; Guo, Y.; Xu, P.; Zhai, Y. PPARs as Nuclear Receptors for Nutrient and Energy Metabolism. Molecules 2019, 24, 2545. [CrossRef]

- Schlaepfer, I.R.; Joshi, M. CPT1A-Mediated Fat Oxidation, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potential. Endocrinology 2020, 161. [CrossRef]

- Gai, Z.; Wang, T.; Visentin, M.; Kullak-Ublick, G.; Fu, X.; Wang, Z. Lipid Accumulation and Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 722. [CrossRef]

- Gewin, L.S. Sugar or Fat? Renal Tubular Metabolism Reviewed in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1580. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-S.; Noh, M.R.; Kim, J.; Padanilam, B.J. Defective Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Oxidation and Lipotoxicity in Kidney Diseases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Piret, S.E.; Attallah, A.A.; Gu, X.; Guo, Y.; Gujarati, N.A.; Henein, J.; Zollman, A.; Hato, T.; Ma’ayan, A.; Revelo, M.P.; et al. Loss of Proximal Tubular Transcription Factor Krüppel-like Factor 15 Exacerbates Kidney Injury through Loss of Fatty Acid Oxidation. Kidney Int 2021, 100, 1250–1267. [CrossRef]

- Ghajar-Rahimi, G.; Agarwal, A. Endothelial KLF11 as a Nephroprotectant in AKI. Kidney360 2022, 3, 1302–1305. [CrossRef]

- Niculae, A.; Gherghina, M.-E.; Peride, I.; Tiglis, M.; Nechita, A.-M.; Checherita, I.A. Pathway from Acute Kidney Injury to Chronic Kidney Disease: Molecules Involved in Renal Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 14019. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, F.; Du, J.; Wang, M.; Hu, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, M.; et al. Diacylglycerol Kinase Epsilon Protects against Renal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Mice through Krüppel-like Factor 15/Klotho Pathway. Ren Fail 2022, 44, 902–913. [CrossRef]

- Sadrkhanloo, M.; Paskeh, M.D.A.; Hashemi, M.; Raesi, R.; Bahonar, A.; Nakhaee, Z.; Entezari, M.; Beig Goharrizi, M.A.S.; Salimimoghadam, S.; Ren, J.; et al. New Emerging Targets in Osteosarcoma Therapy: PTEN and PI3K/Akt Crosstalk in Carcinogenesis. Pathol Res Pract 2023, 251, 154902. [CrossRef]

- Zhengbiao, Z.; Liang, C.; Zhi, Z.; Youmin, P. Circular RNA_HIPK3-Targeting MiR-93-5p Regulates KLF9 Expression Level to Control Acute Kidney Injury. Comput Math Methods Med 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, C. Krüppel-like Factor 4 Modulates the MiR-101/COL10A1 Axis to Inhibit Renal Fibrosis after AKI by Regulating Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Ren Fail 2024, 46. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, J.; Lan, H.-Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.; Mak, K.K.; et al. Activation of the YAP/KLF5 Transcriptional Cascade in Renal Tubular Cells Aggravates Kidney Injury. Molecular Therapy 2024, 32, 1526–1539. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Dominguez, M.; Golestaneh, L. Diabetic Kidney Disease. Medical Clinics of North America 2023, 107, 689–705. [CrossRef]

- Nastase, M. V.; Zeng-Brouwers, J.; Wygrecka, M.; Schaefer, L. Targeting Renal Fibrosis: Mechanisms and Drug Delivery Systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2018, 129, 295–307. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Su, R.; Zhen, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, G. Small Extracellular Vesicles-Shuttled MiR-23a-3p from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviate Renal Fibrosis and Inflammation by Inhibiting KLF3/STAT3 Axis in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 139, 112667. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Mallipattu, S.K.; Estrada, C.; Menon, M.; Salem, F.; Jain, M.K.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Lee, K.; He, J.C. Reduced Krüppel-Like Factor 2 Aggravates Glomerular Endothelial Cell Injury and Kidney Disease in Mice with Unilateral Nephrectomy. Am J Pathol 2016, 186, 2021–2031. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Lu, X.; Ren, J.; Privratsky, J.R.; Yang, B.; Rudemiller, N.P.; Zhang, J.; Griffiths, R.; Jain, M.K.; Nedospasov, S.A.; et al. KLF4 in Macrophages Attenuates TNFα-Mediated Kidney Injury and Fibrosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2019, 30, 1925–1938. [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, N.A.; Frimpong, B.O.; Zaidi, M.; Bronstein, R.; Revelo, M.P.; Haley, J.D.; Kravets, I.; Guo, Y.; Mallipattu, S.K. Podocyte-Specific KLF6 Primes Proximal Tubule CaMK1D Signaling to Attenuate Diabetic Kidney Disease. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 8038. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, W.; Chen, J. Krüppel-like Factor 15: A Potential Therapeutic Target For Kidney Disease. Int J Biol Sci 2019, 15, 1955–1961. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, G.; Gu, X.; Fu, L.; Mei, C. Kruppel-Like Factor 15 Modulates Renal Interstitial Fibrosis by ERK/MAPK and JNK/MAPK Pathways Regulation. Kidney Blood Press Res 2013, 37, 631–640. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, C. Krüppel-like Factor 4 Modulates the MiR-101/COL10A1 Axis to Inhibit Renal Fibrosis after AKI by Regulating Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Ren Fail 2024, 46. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Lv, L.; Tang, T.; Wen, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhu, X.; Feng, S.; Crowley, S.D.; Liu, B. FIH-1-Modulated HIF-1α C-TAD Promotes Acute Kidney Injury to Chronic Kidney Disease Progression via Regulating KLF5 Signaling. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021, 42, 2106–2119. [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zhu, S.; Chen, Y.; Cai, N.; Xu, C.; Tu, W.; Qin, X. Kruppel Like Factor 5 Enhances High Glucose-Induced Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell Transdifferentiation in Diabetic Nephropathy. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2022, 32, 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Kanai, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Ogino, H.; Ochi, H. Adrenergic Receptor Signaling Induced by Klf15, a Regulator of Regeneration Enhancer, Promotes Kidney Reconstruction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119. [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.-H.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Chen, T.-H.; Lin, C.-L. Recent Advances in Diabetic Kidney Diseases: From Kidney Injury to Kidney Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 11857. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lv, L.; Liu, B.; Tang, R. Crosstalk between Tubular Epithelial Cells and Glomerular Endothelial Cells in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Cell Prolif 2020, 53. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Luo, M.; Bai, X.; Nie, P.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, H.; Li, B.; Luo, P. Cellular Crosstalk of Glomerular Endothelial Cells and Podocytes in Diabetic Kidney Disease. J Cell Commun Signal 2022, 16, 313–331. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Zhan, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jin, J.; He, Q. Krüppel-like factor 4 Ameliorates Diabetic Kidney Disease by Activating Autophagy via the MTOR Pathway. Mol Med Rep 2019. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Lin, R.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J.; Pan, K.; et al. Lactate Drives Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Diabetic Kidney Disease via the H3K14la/KLF5 Pathway. Redox Biol 2024, 75, 103246. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-C.; Lin, H.-H.; Tang, M.-J. Matrix-Stiffness–Regulated Inverse Expression of Krüppel-Like Factor 5 and Krüppel-Like Factor 4 in the Pathogenesis of Renal Fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2015, 185, 2468–2481. [CrossRef]

- Holian, J.; Qi, W.; Kelly, D.J.; Zhang, Y.; Mreich, E.; Pollock, C.A.; Chen, X.-M. Role of Krüppel-like Factor 6 in Transforming Growth Factor-Β1-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Proximal Tubule Cells. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2008, 295, F1388–F1396. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-C.; Ho, C.; Shih, Y.-H.; Ni, W.-C.; Li, Y.-C.; Chang, H.-C.; Lin, C.-L. Knockout of KLF10 Ameliorated Diabetic Renal Fibrosis via Downregulation of DKK-1. Molecules 2022, 27, 2644. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Hsu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Shih, Y.; Wang, C.; Chiang, W.; Chang, P. A KDM6A–KLF10 Reinforcing Feedback Mechanism Aggravates Diabetic Podocyte Dysfunction. EMBO Mol Med 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Mou, X.; Zhou, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhou, D. Identification of Potential Therapeutic Target Genes in Mouse Mesangial Cells Associated with Diabetic Nephropathy Using Bioinformatics Analysis. Exp Ther Med 2019. [CrossRef]

| Cell of nephron | KLF | Role | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Podocytes | KLF2 | Downregulates the expression of occludin, preventing its overexpression from altering the structure of the GBM. | [26] |

| KLF4 | Induces positive expression of E-cadherin, podocin, and nephrin through interactions with HDACs, for the maintenance of tight junctions and the slit diaphragm. ____________________________________________________ Induces the expression of cytokeratins (K8 and K18) that help in the cytoskeleton's organization. _____________________________________________________ Downregulates mesenchymal markers such as vimentin and α-SMA, preventing EMT and structural damage. |

[29] | |

| Glomerular endothelial cells | KLF2 | Regulates the size and distribution of transcellular pores in the ECs by inhibiting the phosphorylation of the myosin light chain. ____________________________________________________________ Modulates VEGF-A-mediated angiogenesis by downregulating its expression, preventing an excess of blood vessels. |

[28,36] |

| KLF4 | Mediates inflammation by downregulating VCAM1 induced by TNF-α, inhibiting the p65 subunit of NF-κB. | [37] | |

| Mesangial cells | KLF4 | Attenuates the expansion of the mesangial matrix and its proliferation by negatively regulating the mTOR pathway, downregulating the expression of phosphorylated (p) mTOR and p S6K proteins, preventing excessive extracellular ECM production, | [41] |

| Proximal tubule cells | KLF4 | Mitigates inflammation and fibrosis by decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as MCP-1, MIP-3α, and IL-8. | [44] |

| KLF11 | Like KLF4, it participates in the mitigation of inflammation and fibrosis by reducing the expression of the same pro-inflammatory cytokines. | [43] | |

| KLF15 | Decreases the expression of fibronectin by negatively regulating the MAPK pathways. | [46] |

| Disease | Group Klf | Role | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic kidney disease | Group 1 (Klf 3, 8 and 12) |

Not Available | |

| Group 2 (Klf 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7) |

KLF2 protects endothelial cell injury through anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, and anti-angiogenic effects, as it maintains the proper function of glomerular endothelial cells. Its deficiency has been shown to lead to the progression of renal disease | [36,87] | |

| KLF4 suppression causes the polarization of infiltrating macrophages into myeloid cells that accumulate in the glomerulus and tubular interstitium in CKD to shift to an M1 phenotype. The M1 phenotype of macrophages promotes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-1β. These cytokines exacerbate renal parenchymal injury and accelerate disease progression. Conversely, KLF4 expression suppresses the differentiation of infiltrating macrophages, mitigating renal damage by inhibiting TNFα expression in myeloid cells. Thus, KLF4 is considered a protective transcription factor. In addition, KLF4 mitigates inflammation and fibrosis caused by the TGF-β1-induced release of cytokines MCP-1, MIP-3α and IL-8 in human proximal tubule cells, possibly relating to the phosphorylation of KLF4 that TGF-β1 induces via SMAD and p38/MAPK signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). It has even been linked to the inhibition of podocyte apoptosis through regulating the mTOR signaling pathway, which is involved in regulating cell growth, proliferation, and survival. | [44,88] | ||

| KLF5 participates in the initiation and progression of tubulointerstitial inflammation, and its expression is increased in proliferating renal tubule cells in the cortex and medulla of fibrotic kidneys. KLF5 regulates renal fibrosis through activation of HIF-1α-KLF5-TGF-β1 pathway, renal cell proliferation through activation of ERK/YAP1/KLF5/cyclin D1 pathway, and tubulointerstitial inflammation with upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines which promotes kidney injury. | [7,8] | ||

| KLF6 triggers the release of Apolipoprotein J/Clusterin (Apoj) in podocytes. Apoj activates the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 1D (CaMK1D) signaling in neighboring proximal tubular cells. This is crucial because CaMK1D can attenuate mitochondrial fission and restore mitochondrial function under diabetic conditions [7]. | [89] | ||

| Group 3 (Klf 9, 10, 11, 13, 14 and 16) |

KLF11 deficiency is associated with increased renal atrophy, fibrosis, and interstitial inflammation in a mouse model of chronic renal obstruction (UUO). In KLF11 KO-UUO mice, this deficiency is linked to the upregulation of genes such as collagen type I, fibronectin, TGF-β1, as well as IL-6 and TNF-α. These genes are associated with TGF-β signaling, fibrosis, and inflammation. |

[45] | |

| No group (15 and 17) |

KLF15 is downregulated by TGF-β1, which activates multiple intracellular signal transduction systems and MAPK pathways, including ERK and JNK, leading to renal fibrosis. Thus, KLF15 may play an anti-fibrotic factor in renal interstitial fibrosis by decreasing extracellular matrix fibronectin, type III collagen and CTGF expression in renal fibroblast. KLF15 Prevents fibrosis by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathways and suppress the recruitment of P/CAF to the CTGF promoter in mesangial cells. | [90,91] | |

| Acute kidney injury | Group 1 (Klf 3, 8 and 12) |

Not Available | |

| Group 2 (Klf 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7) |

Overexpression of KLF4 in proximal tubular cells (HK-2) upregulates the expression of miR-101. This increase in miR-101, downregulates the expression of COL10A1, thereby suppressing EMT and renal fibrosis during the pathogenic process of renal fibrosis associated with acute kidney injury. In contrast, the inhibition of KLF4 expression, directly mediated by epigenetic regulatory enzymes such as DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1), which hypermethylates the KLF4 promoter region, contributes to the progression of EMT in renal EpC. | [92] | |

| KLF5 is regulated by YAP and promotes the expression of Mst1/2, which are proteins involved in the Hippo signaling pathway. Activation of this pathway leads to over proliferation of tubular cells, tubular injury, and inflammation. KLF5 can be upregulated in severe acute kidney injury because of the activation of HIF-1α, which facilitates the transition to chronic kidney disease. The overexpression of KLF5 promotes renal fibrosis and tubular dysfunction, exacerbating acute kidney injury. Another mechanism by which KLF5 is attributed the ability to drive the transdifferentiation of renal tubular EpC is that, in a hypercaloric state, KLF5 binds to the HMGB1 promoter, thereby promoting the transcription of High Mobility Group Box 1 protein. | [83,93,94] | ||

| Group 3 (Klf 9, 10, 11, 13, 14 and 16) |

KLF9, which is upregulated by miR-93-5p, inhibited the expression of circHIPK3, leading to alleviation of oxidative stress and apoptosis in an in vivo model of AKI established by ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) in C57BL/6 mice or hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) in HK-2 cells. The circular RNA HIPK3 (circHIPK3), derived from the HIPK3 gene, is important because of its pro-inflammatory activity. | [81] | |

| KLF10 is downregulated in tubular cells during acute kidney injury. This finding suggests that KLF10 acts as a renoprotective protein and provides protection against acute kidney injury, as its induction improves tubular regeneration through the ZBTB7A-KLF10-PTEN axis. PTEN is important because it can inhibit the PI3K/Akt pathway, which regulates cell growth, death, migration, and differentiation. | [80] | ||

| No group (15 and 17) |

KLF15 acts as a bridge connecting the signaling of diacylglycerol kinase epsilon (DGKE) and Klotho. This DGKE/KLF15/Klotho pathway protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) and AKI in a murine model. In a Xenopus laevis model, it was showed that KLF15 directly binds to enhancers and stimulates the expression of regenerative genes, including adrenoreceptor α 1A (adra1α), suggesting that KLF15 might even promote the regeneration of nephric tubules. As KLF15 attenuates damage and development of glomerulosclerosis, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, inflammation, and stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton, thereby improving renal function. | [79,95] | |

| Diabetic kidney disease | Group 1 (Klf 3, 8 and 12) |

KLF3 directly regulates the transcription of STAT3. In proximal tubular cells (HK-2) exposed to high glucose concentrations, the suppression of KLF3 mediated by miR-23a-3p resulted in the inhibition of STAT3, a protein crucial for regulating inflammation and fibrosis associated with metabolic diseases. Thus, the inhibition of KLF3 leads to a protective effect in renal disease. | [86] |

| Group 2 (Klf 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7) |

KLF2 is upregulated by insulin treatment and downregulated by high glucose concentrations in cultured endothelial cells from KLF2 KO diabetic mice. This effect was showed through FOXO1-dependent transcriptional silencing, which led to glomerular endothelial damage and podocyte injury. This inhibition of KLF2 by FOXO1 has been shown to decrease the expression of the genes nephrin, podocin, and synaptopodin, which are important for the structure and function of podocytes. The deletion of KLF2 (knockout, KO) in the glomeruli reduces the expression of several of its target genes, including endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), the glycocalyx, fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 (Flt1), tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like and EGF-like domains 2 (Tie2), and angiopoietin 1 (Angpt1). These genes are primarily involved in the function and integrity of the vascular endothelium, which is why KLF2 is considered a vasoprotective factor. |

[7,96,97,98] |

|

| KLF4 overexpression induces podocyte autophagy, protecting the tissue from damage in DKD. Suppresses cell proliferation and differentiation during fibrosis and inhibits EMT processes. Hyperglycemia also decreases KLF4 expression and increases TGF-β expression leading to unregulated inflammation in renal tissue. | [7,96,97,99] | ||

| KLF5 is overexpressed in the collecting duct EpC found in diabetic kidney and tubulointerstitial disease and associated with alterations like an expansion of mesangial matrix and tubular interstitial space, podocyte damage, and glomerular basement membrane thickening, showing that KLF5 plays a pivotal role in the initiation and progression of renal inflammation. In fact, the inverse expression of KLF4 and KLF5 in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis is modulated by a matrix stiffness-regulated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), which increases the protein level and nuclear translocation of mechanosensitive YAP1, preventing the degradation of KLF5. KLF5 is upregulated under hyperglycemic conditions through lactylation of lysine 14 on histone H3 (H3K14la). KLF5 binds to the promoter of the gene encoding E-cadherin (Cadherin 1, cdh1) and inhibits its transcription, promoting disease progression. This lactylation results from the accumulation of lactate because of the metabolic reprogramming that renal PCT undergo in a hyperglycemic state, specifically the shift from oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to glycolysis. | [8,100,101] | ||

| KLF6, under conditions that promote renal damage and fibrosis, such as diabetic nephropathy, its overexpression enables TGF-β1 to induce the loss of E-cadherin, gain in vimentin expression, and EMT of proximal tubule cells. In CKD, TGF-β promotes renal fibrosis by enhancing matrix formation, cell proliferation, and cell migration via MAPK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B, and Smad2/3/4 pathways, subsequently elevating fibronectin, collagen, and α-SMA. | [102] | ||

| Group 3 Klf 9, 10, 11, 13, 14 and 16) |

KLF 10 Activates KDM6A and induces proteinuria, kidney damage and fibrosis under diabetic conditions. Represses nephrin, WT1, podocin, and synaptophysin in podocytes. Increases expression of type I and III collagen, fibronectin, and metalloproteinases. | [96,103,104] | |

| No group and (KLF15 and KLF17) |

KLF15 modulates mitochondrial biogenesis and homeostasis through the SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway in mouse mesangial cells associated with diabetic nephropathy. This finding was determined through enrichment analysis, which identifies KLF15 as a therapeutic target. | [105] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).