Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Sample Processing

2.1. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cytotoxic Test of Doxorubicin-Induced Cytotoxicity in Feline Kidney Cells

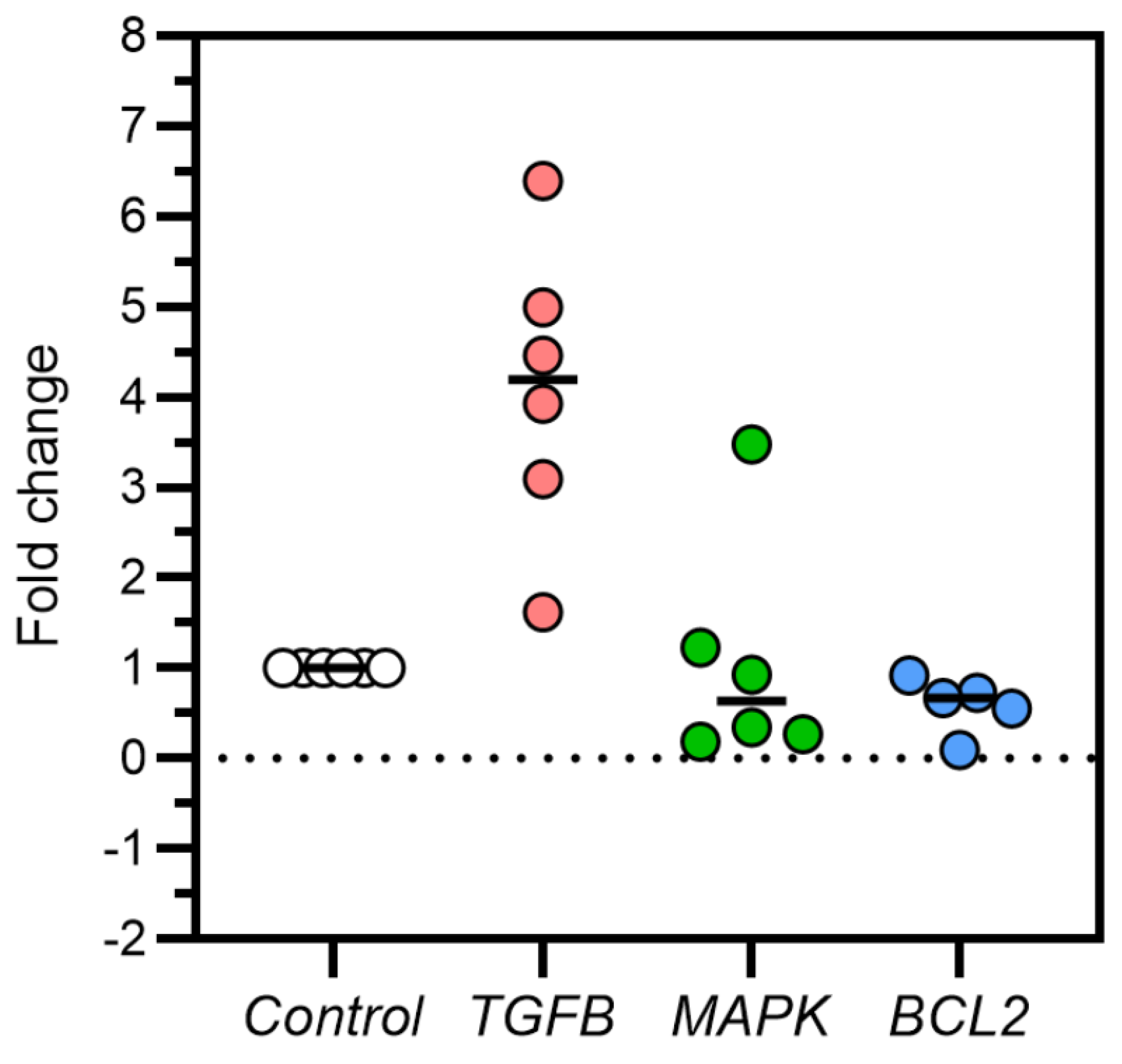

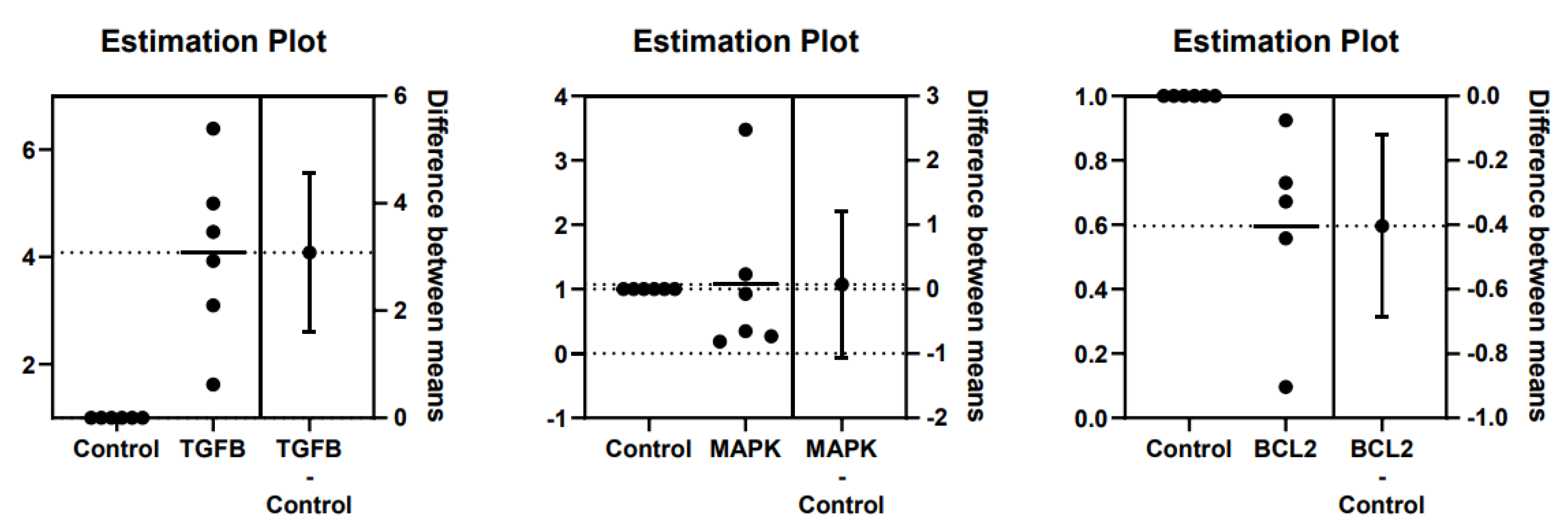

3.2. TGFβ, MAPK, and Bcl2 Relative Gene Expression in Feline Kidney Cells

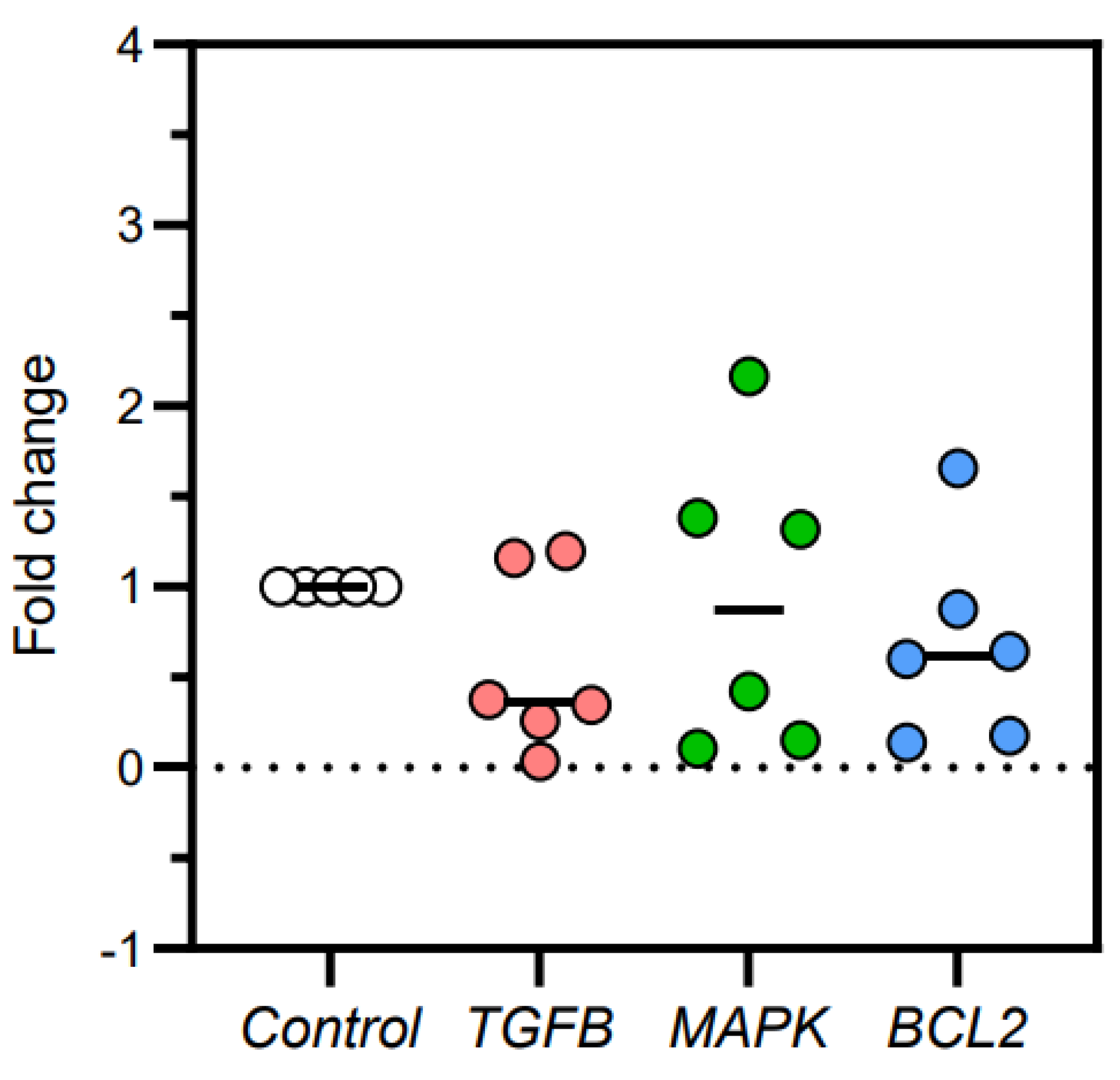

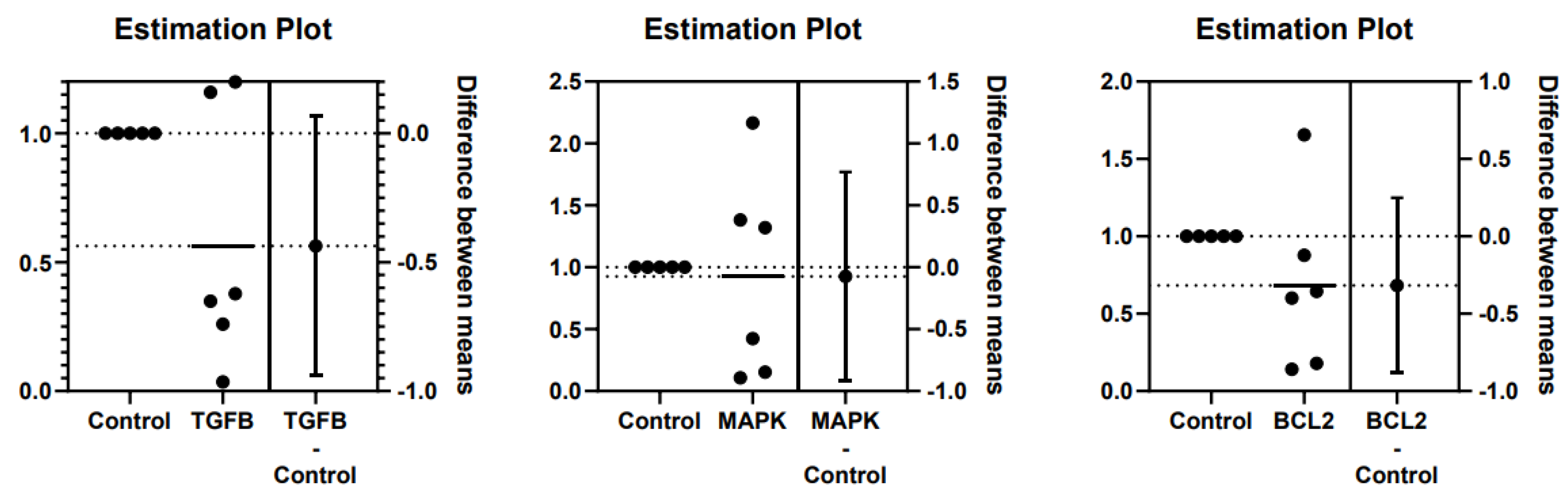

3.3. TGFβ, MAPK, and Bcl2 Relative Gene Expression in Kidney Tissues

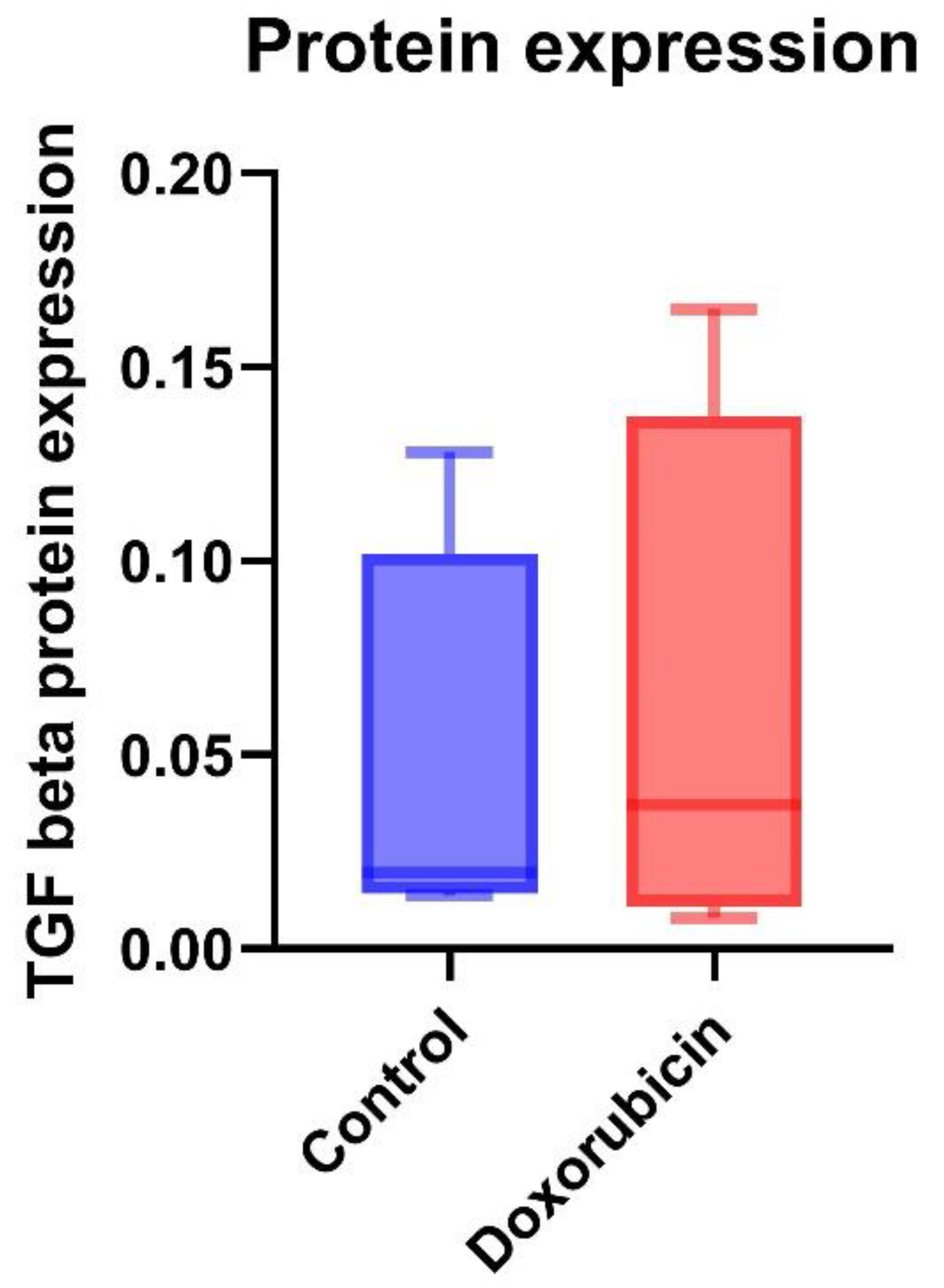

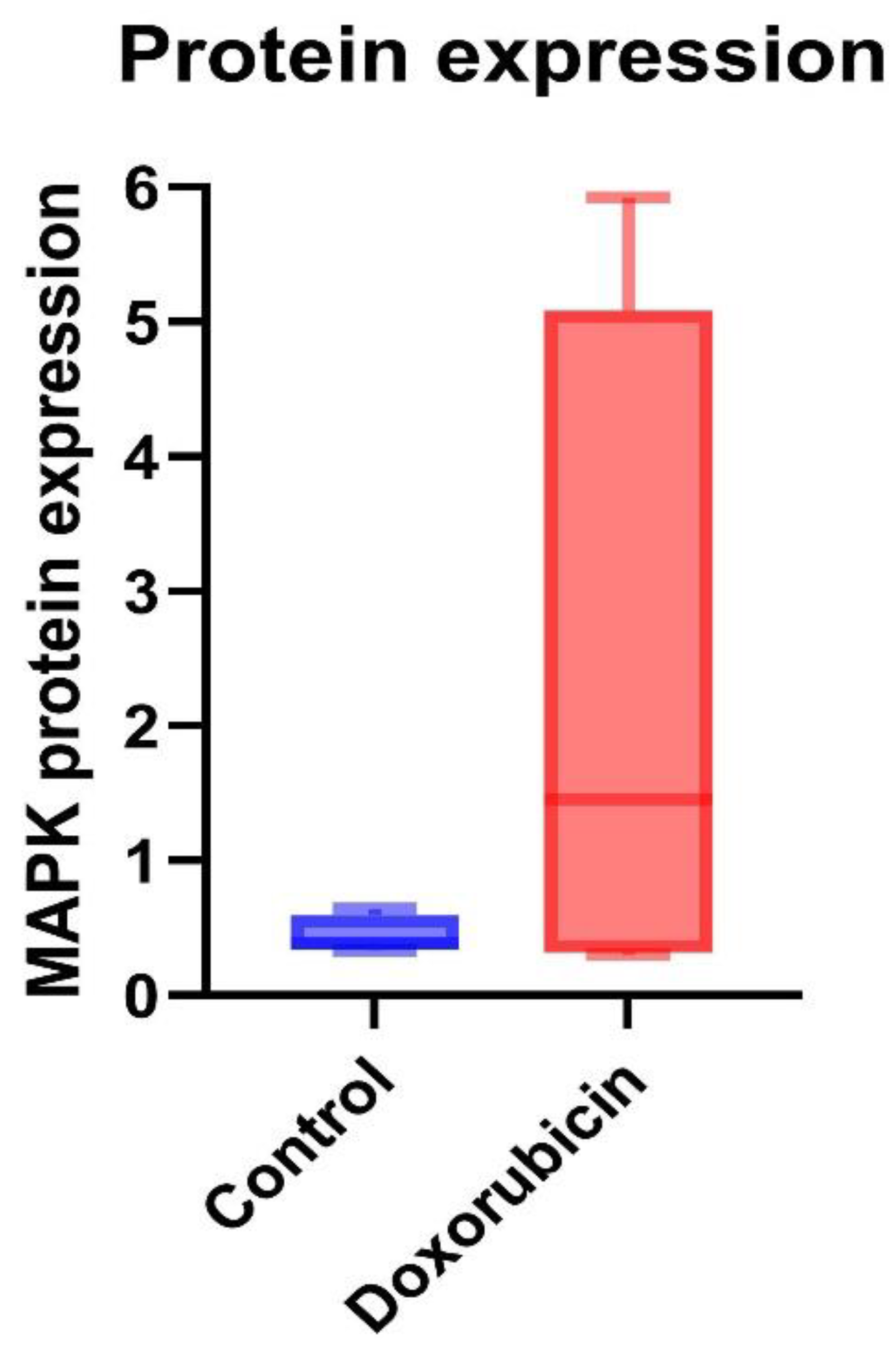

3.4. Protein Expression of TGF-β and MAPK in Feline Kidney Cells

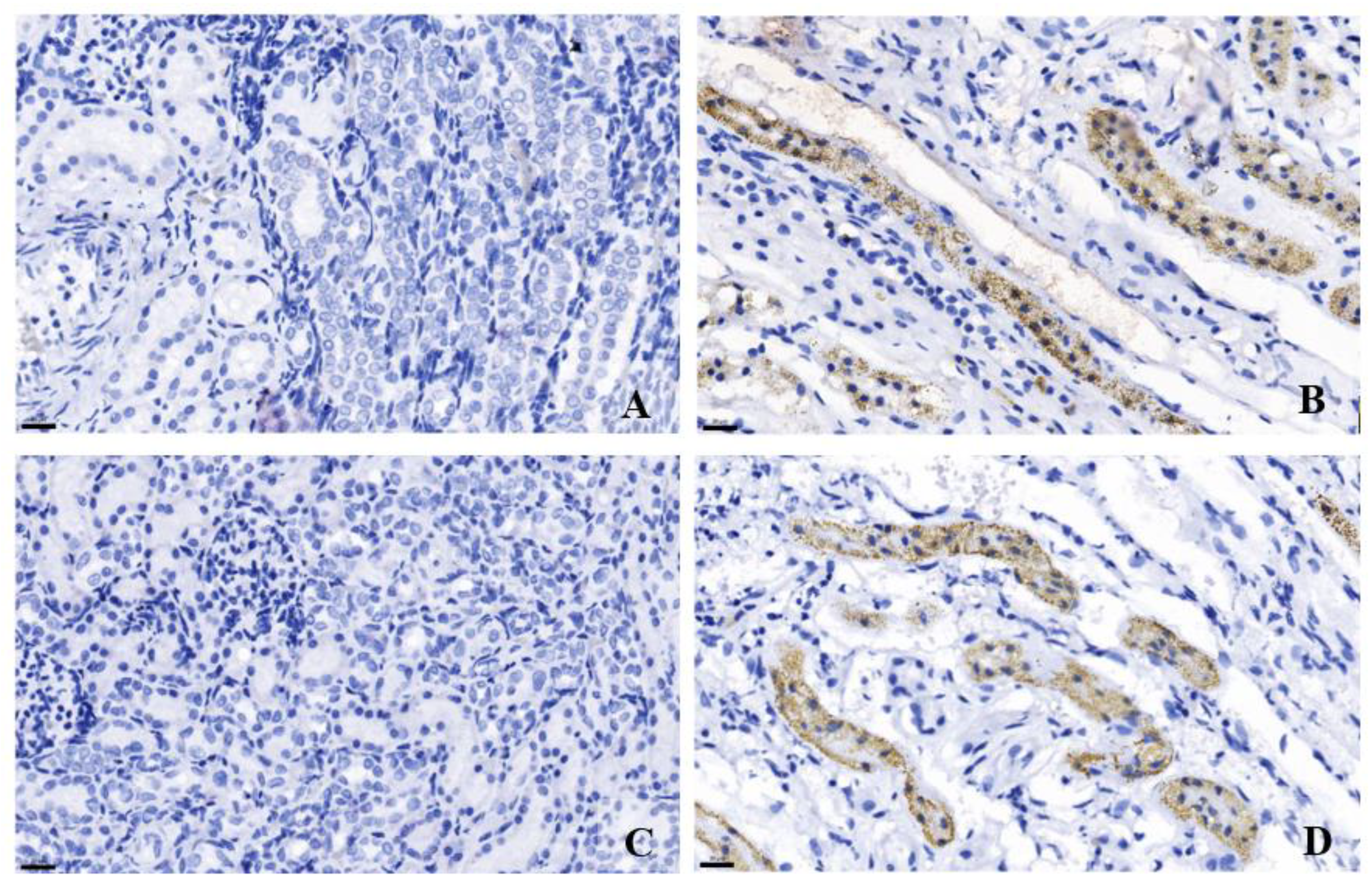

3.5. Immunohistochemistry of TGF-β and MAPK in Cat Kidney Tissues

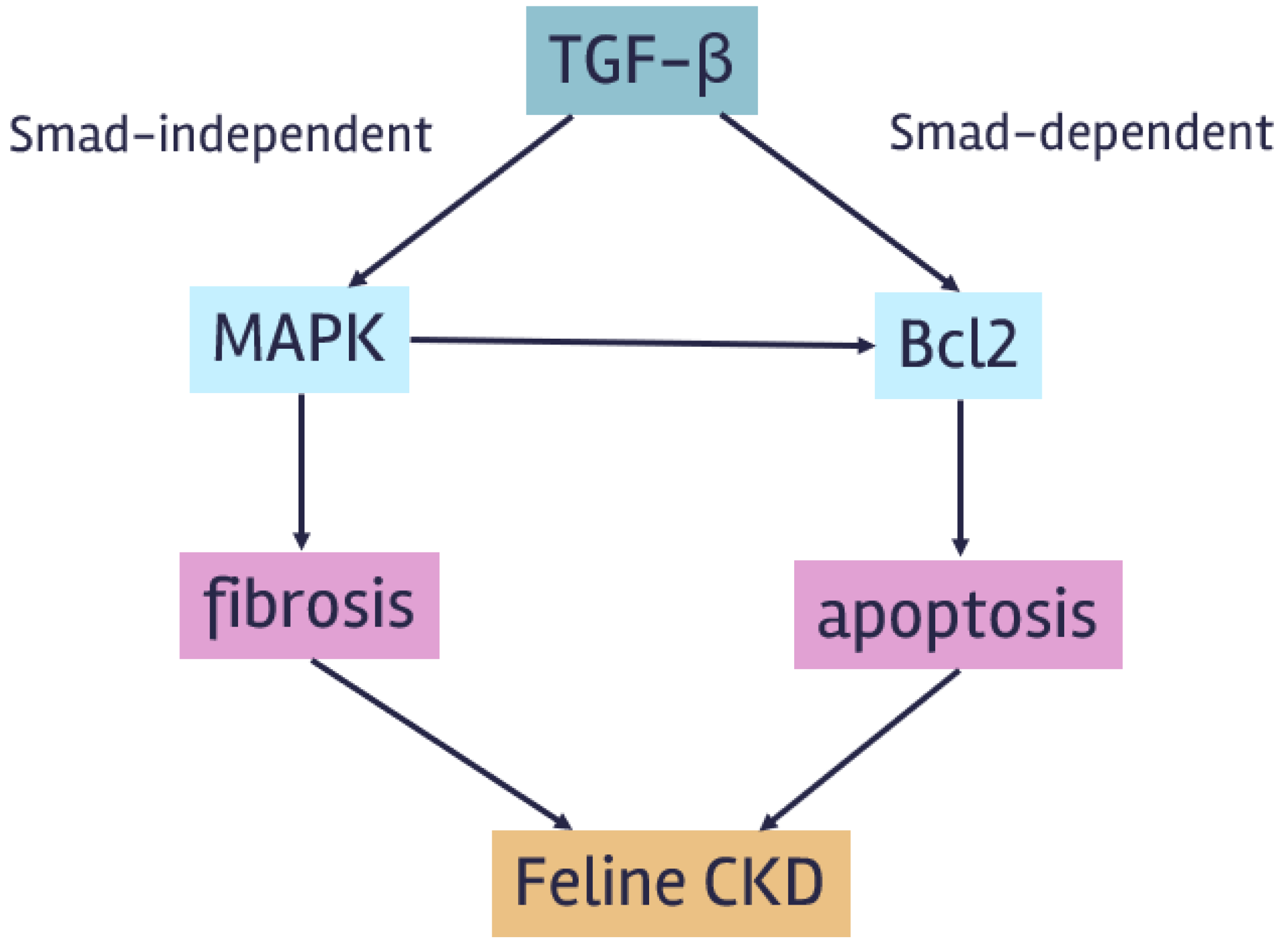

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Polzin, D.J. Chronic kidney disease in small animals. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice 2011, 41, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'neill, D.; Church, D.; McGreevy, P.; Thomson, P.; Brodbelt, D. Prevalence of disorders recorded in cats attending primary-care veterinary practices in England. The Veterinary Journal 2014, 202, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piyarungsri, K.; Tangtrongsup, S.; Thongtharb, A.; Sodarat, C.; Bussayapalakorn, K. The risk factors of having infected feline leukemia virus or feline immunodeficiency virus for feline naturally occurring chronic kidney disease. Veterinary Integrative Sciences 2020, 18, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Marino, C.L.; Lascelles, B.D.X.; Vaden, S.L.; Gruen, M.E.; Marks, S.L. Prevalence and classification of chronic kidney disease in cats randomly selected from four age groups and in cats recruited for degenerative joint disease studies. Journal of feline medicine and surgery 2014, 16, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.H.; Caney, S.; Chalhoub, S.; Elliott, J.; Finch, N.; Gajanayake, I.; Langston, C.; Lefebvre, H.P.; White, J.; Quimby, J. ISFM consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of feline chronic kidney disease. Journal of feline medicine and surgery 2016, 18, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Syme, H.; Brown, C.; Elliott, J. Histomorphometry of feline chronic kidney disease and correlation with markers of renal dysfunction. Veterinary pathology 2013, 50, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, J.; Elliott, J.; Wheeler-Jones, C.; Syme, H.; Jepson, R. Renal fibrosis in feline chronic kidney disease: known mediators and mechanisms of injury. The Veterinary Journal 2015, 203, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M.; Derynck, R.; Miyazono, K. TGF-β and the TGF-β family: context-dependent roles in cell and tissue physiology. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2016, 8, a021873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeeva, O. TGFβ family signaling pathways in pluripotent and teratocarcinoma stem cells’ fate decisions: Balancing between self-renewal, differentiation, and cancer. Cells 2019, 8, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholin, L.; Vincent, D.F.; Valcourt, U. TGF-β as tumor suppressor: in vitro mechanistic aspects of growth inhibition. TGF-β in Human Disease 2013, 113-138.

- Habenicht, L.M.; Webb, T.L.; Clauss, L.A.; Dow, S.W.; Quimby, J.M. Urinary cytokine levels in apparently healthy cats and cats with chronic kidney disease. Journal of feline medicine and surgery 2013, 15, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, Y.; Furusawa, Y.; Islam, M.S.; Yamato, O.; Hatai, H.; Ichii, O.; Yabuki, A. Immunohistochemical Expression of TGF-β1 in Kidneys of Cats with Chronic Kidney Disease. Veterinary Sciences 2022, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piyarungsri, K.; Chuammitri, P.; Pringproa, K.; Pila, P.; Srivorakul, S.; Sornpet, B.; Pusoonthornthum, R. Decreased circulating transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and kidney TGF-β immunoreactivity predict renal disease in cats with naturally occurring chronic kidney disease. Journal of feline medicine and surgery 2023, 25, 1098612X231208937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, H.; Radford, R.; Slyne, J.; O’Connell, S.; Slattery, C.; Ryan, M.P.; McMorrow, T. The role of MAPK in drug-induced kidney injury. Journal of signal transduction 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Warner, G.M.; Yin, P.; Knudsen, B.E.; Cheng, J.; Butters, K.A.; Lien, K.R.; Gray, C.E.; Garovic, V.D.; Lerman, L.O. Inhibition of p38 MAPK attenuates renal atrophy and fibrosis in a murine renal artery stenosis model. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2013, 304, F938–F947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; López, J.M. Understanding MAPK signaling pathways in apoptosis. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkan, S.C. The role of BCL-2 family members in acute kidney injury. Seminars in nephrology 2016. [CrossRef]

- Youle, R.J.; Strasser, A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2008, 9, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pila, P.; Chuammitri, P.; Patchanee, P.; Pringproa, K.; Piyarungsri, K. Evaluation of Bcl-2 as a marker for chronic kidney disease prediction in cats. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 9, 1043848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaotham, C.; De-Eknamkul, W.; Chanvorachote, P. Protective effect of plaunotol against doxorubicin-induced renal cell death. Journal of natural medicines 2013, 67, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Journal of immunological methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiggeri, G.M.; Bertelli, R.; Ginevri, F.; Oleggini, R.; Altieri, P.; Trivelli, A.; Gusmano, R. Multiple mechanisms for doxorubicin cytotoxicity on glomerular epithelial cells ‘in vitro’. European Journal of Pharmacology: Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 1992, 228, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, W.; Zhao, J.; Sun, W.; Yang, Q.; Chen, C.; Xia, P.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, G. Apigenin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced renal injury via inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy 2021, 137, 111308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piyarungsri, K.; Pusoonthornthum, R.; Rungsipipat, A.; Sritularak, B. (2014). INVESTIGATION OF RISK FACTORS INVOLVING IN FELINE CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE, OXI DATIVE STRESS AND STUDY THE EFFECT OF ANTIDESMA ACIDUM CRUDE EXTRACT IN F ELINE KIDNEY CELL LINE Doctoral thesis, Chulalongkorn University].

- Park, E.J.; Kwon, H.K.; Choi, Y.M.; Shin, H.J.; Choi, S. Doxorubicin induces cytotoxicity through upregulation of pERK-dependent ATF3. PLoS One 2012, 7, e44990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-M.; Jeon, J.-H.; Kim, C.-W.; Cho, S.-Y.; Lee, H.-J.; Jang, G.-Y.; Jeong, E.M.; Lee, D.-S.; Kang, J.-H.; Melino, G. TGFβ mediates activation of transglutaminase 2 in response to oxidative stress that leads to protein aggregation. The FASEB Journal 2008, 22, 2498–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beusekom, C.D.; Zimmering, T.M. Profibrotic effects of angiotensin II and transforming growth factor beta on feline kidney epithelial cells. Journal of feline medicine and surgery 2019, 21, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Wu, G.; Dai, T.; Lang, Y.; Chi, Z.; Yang, S.; Dong, D. Naringin attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis by regulating the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway and inflammation. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2021, 21, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Yang, S.; He, W.; Li, L.; Xu, R.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Zhan, R.; Sun, W.; Tan, J. P311 promotes renal fibrosis via TGFβ1/Smad signaling. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 17032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Gao, W.; Dang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Peng, X.; Ye, X. (2013). Both ERK/MAPK and TGF-Beta/Smad signaling pathways play a role in the kidney fibrosis of diabetic mice accelerated by blood glucose fluctuation. Journal of diabetes research, 2013.

- Lv, Y. h.; Ma, K. j.; Zhang, H.; He, M.; Zhang, P.; Shen, Y. w.; Jiang, N.; Ma, D.; Chen, L. A Time Course Study Demonstrating m RNA, micro RNA, 18 S r RNA, and U 6 sn RNA Changes to Estimate PMI in Deceased Rat's Spleen. Journal of forensic sciences 2014, 59, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakral, S.; Purohit, P.; Mishra, R.; Gupta, V.; Setia, P. (2023). The impact of RNA stability and degradation in different tissues to the determination of post-mortem interval: A systematic review. Forensic Sci Int, 349, 111772. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, J.; Syme, H.; Wheeler-Jones, C.; Elliott, J. (2016). Urinary active transforming growth factor β in feline chronic kidney disease. The Veterinary Journal, 214, 1-.

- Meng, X.-m.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.J.; Lan, H.Y. TGF-β: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2016, 12, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-A.; Kim, H.-T.; Cho, I.-S.; Sheen, Y.; Kim, D.-K. IN-1130, a novel transforming growth factor-β type I receptor kinase (ALK5) inhibitor, suppresses renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Kidney international 2006, 70, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T.; Holbrook, N.J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. nature 2000, 408, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.M.; Xu, W.M.; Lin, J.C.; Mo, L.Q.; Hua, X.X.; Chen, P.X.; Wu, K.; Zheng, D.D.; Feng, J.Q. Activation of the p38 MAPK/NF-kappaB pathway contributes to doxorubicin-induced inflammation and cytotoxicity in H9c2 cardiac cells. Mol Med Rep 2013, 8, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H.T. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell research 2002, 12, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, T.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. TGF-beta signaling in health, disease, and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.N.; Yang, S.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Hwang, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, D.W.; Hur, D.G.; Oh, Y.K. Periostin induces kidney fibrosis after acute kidney injury via the p38 MAPK pathway. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2019, 316, F426–F437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; An, J.N.; Hwang, J.H.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.P.; Kim, S.G. p38 MAPK activity is associated with the histological degree of interstitial fibrosis in IgA nephropathy patients. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0213981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshikawa, M.; Mukoyama, M.; Mori, K.; Suganami, T.; Sawai, K.; Yoshioka, T.; Nagae, T.; Yokoi, H.; Kawachi, H.; Shimizu, F. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in podocyte injury and proteinuria in experimental nephrotic syndrome. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2005, 16, 2690–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.; Yang, Y.; Shi, K.; Luo, H.; Duan, J.; An, J.; Wu, P.; Ci, Y.; Shi, L.; Xu, C. The p38 MAPK-regulated PKD1/CREB/Bcl-2 pathway contributes to selenite-induced colorectal cancer cell apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Cancer letters 2014, 354, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Harchegani, A.; Saeedian, S.; Owrang, M.; Parvizi, M. (2021). Effect of N-acetyl cysteine on oxidative stress and Bax and Bcl2 expression in the kidney tissue of rats exposed to lead. Ukrainian Biochemical Journal.

- Motyl, T.; Grzelkowska, K.; Zimowska, W.; Skierski, J.; Warȩski, P.; Płoszaj, T.; Trzeciak, L. Expression of bcl-2 and bax in TGF-β1-induced apoptosis of L1210 leukemic cells. European journal of cell biology 1998, 75, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goumenos, D.S.; Tsamandas, A.C.; Kalliakmani, P.; Tsakas, S.; Sotsiou, F.; Bonikos, D.S.; Vlachojannis, J.G. Expression of Apoptosis-Related Proteins Bcl-2 and Bax Along with Transforming Growth Factor (TGF-β1) in the Kidney of Patients with Glomerulonephritides. Renal failure 2004, 26, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyarungsri, K.; Pusoonthornthum, R. Changes in reduced glutathione, oxidized glutathione, and glutathione peroxidase in cats with naturally occurring chronic kidney disease. Comparative Clinical Pathology 2016, 25, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene name | Accession | Direction | Sequence | Annealing Temp. (°C) | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβ | M38449.1 | Forward | CCCTGGACACCAACTATTGC | 60 60 |

163 |

| Reverse | TCCAGGCTCCAAATGTAGGG | ||||

| MAPK | XM_003994973.5 | Forward | ACTGCTGAGCTAAGACCATGAG | 60 60 |

119 |

| Reverse | AAGTCAATGCCACAGTGTGC | ||||

| Bcl2 | NM_001009340.1 | Forward | CCTATCTGGGCCACAAGTGA | 60 60 |

123 |

| Reverse | TAAGAGACCACGGCTTCGTT | ||||

| β-actin | AB051104.1 | Forward | CCATCGAACACGGCATTGT | 60 60 |

147 |

| Reverse | TCTTCTCACGGTTGGCCTTG |

| Protein name | Antibodies | Dilution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WB | IHC | ||

| TGF-β | Primary mouse monoclonal TGF-beta 1 Secondary goat anti-mouse |

1:1000 1:5000 |

1:200 |

| MAPK | Primary mouse polyclonal p38 MAPK Secondary goat anti-mouse |

1:1000 1:5000 |

1:200 |

| β-actin | Direct-Blot HRP mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin | 1:1000 | |

| mRNA expression | Fold-change | Difference between mean ± SD | ANOVA P-value |

Unpaired t-test P-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 6) |

DOX-treated (n = 6) |

||||

| TGFβ | 1 | 4.084 | 3.084 ± 0.668 0.072 ± 0.509 -0.404 ± 0.125 |

0.002** | 0.001** |

| MAPK | 1 | 1.072 | 0.890 | ||

| Bcl2 | 1 | 0.596 | 0.010* | ||

| mRNA expression | Fold-change | Difference between mean ± SD | ANOVA P-value |

Unpaired t-test P-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No kidney lesions (n = 6) |

CKD (n = 6) |

||||

| TGFβ | 1 | 0.563 | -0.437 ± 0.222 -0.075 ± 0.373 -0.317 ± 0.251 |

0.549 | 0.081 |

| MAPK | 1 | 0.925 | 0.846 | ||

| Bcl2 | 1 | 0.683 | 0.238 | ||

| Protein expression | Control (n = 3) |

DOX-treated (n = 3) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β | 0.04 ± 0.05 | 0.06 ± 0.07 | 0.73 |

| MAPK | 0.44 ± 0.14 | 2.28 ± 2.64 | 0.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).