Introduction

CKD affects approximately 14% of adults in the United States and is more prevalent among older adults, women, and non-Hispanic black individuals [

1]. CKD can progress to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [

2]. Ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) is a common cause of AKI, a major risk factor for CKD, in both clinical and experimental settings [

3,

4]. The progression from AKI to CKD involves maladaptive repair, including persistent inflammation, tubular atrophy, capillary loss, and fibrosis, altogether leading to irreversible renal failure [

5]. No effective therapies exist to prevent or reverse IRI-induced AKI or halt CKD progression [

6]. Evidence also shows systemic effects, with contralateral kidney injury driven by circulating inflammatory/oxidative factors, indicating AKI impacts whole-body homeostasis [

5,

7].

Genetic predispositions, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes in oxidative stress regulation and immune signaling, have been linked to modulate susceptibility to AKI and CKD [

8]. Notably, SNPs in the

Engulfment and Cell Motility 1 (

ELMO1) gene have been associated with kidney diseases such as diabetic nephropathy and nephrotic syndrome [

9,

10]. Our previous work showed that physiological variation in

Elmo1 (20–200%) links diabetic complications via increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [

11,

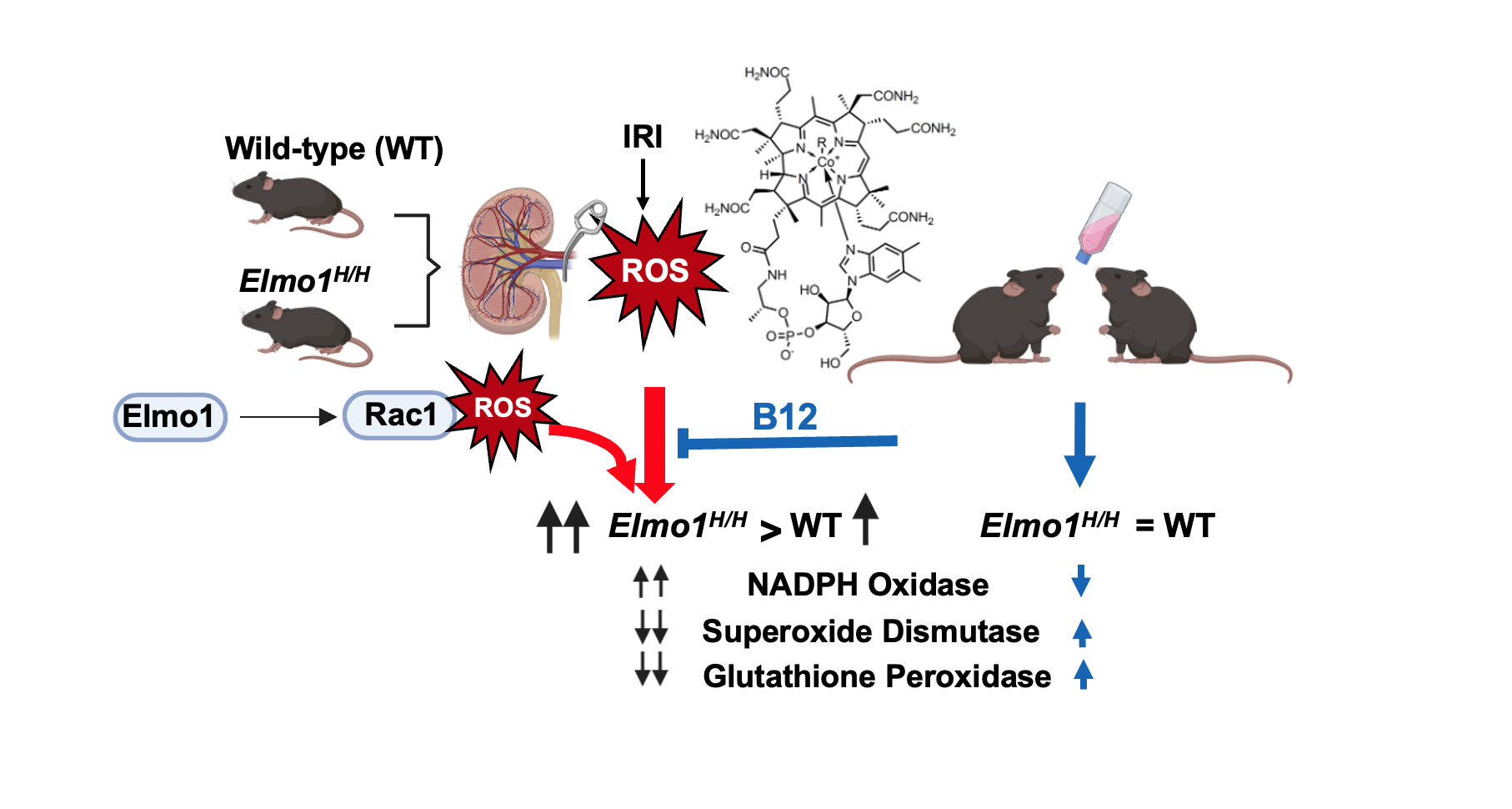

12]. Elmo1 activates Rac family small GTPase 1 (Rac1) through dedicator of cytokinesis (Dock) proteins, promoting NADPH oxidase–dependent ROS generation. Oxidative stress is a key mediator of IRI-induced kidney injury and AKI-to-CKD progression [

13].

In this study, we examined the role of high

Elmo1 expression in kidney damage progression at one month and four months after unilateral IRI. Using wild-type (WT) and

Elmo1H/H mice, which express approximately twice the WT level of

Elmo1 mRNA [

11]. We showed that

Elmo1 overexpression worsened CKD-like phenotypes in both affected and contralateral kidneys, with altered redox genes, heightened immune response, and increased fibrosis, indicating overexpressed

Elmo1 amplifies injury beyond the primary site. Because vitamin B12 (cobalamin) has potent antioxidant properties and our prior study demonstrated its protective effects against IRI [

14], we tested whether vitamin B12 could execute any beneficial effects on AKI induced CKD progression in this context. Our findings highlight redox imbalance as a key driver in disease progression and support vitamin B12 as a readily available candidate for therapeutic intervention, particularly during the early transition phase.

Methods

Mice: WT and Elmo1H/H mice with a C57BL/6J background in both sexes at age of 12–16 weeks were housed in standard cages on a 12-h light/dark cycle and were allowed free access to food and water. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institute of Health’s guidelines for the use and care of experimental animals, as approved by the IACUC of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (protocol number #: 22-229).

Renal ischemia/reperfusion (IR) procedure: Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane inhalation, and core body temperature was maintained at 37°C. A midline laparotomy was performed, the left renal pedicle was clamped using microaneurysm clamps for 30 minutes to induce ischemia. The clamps were then removed to allow reperfusion, and the incision was closed. In sham-operated controls, the renal pedicle was left untouched, but the abdomen remained open for 30 minutes with exposure of the left renal pedicle as previously described [

14].

Vitamin B12 treatment: Mice with IR surgery were randomly enrolled into either vehicle (water) or B12 treatment groups at a dose of 50 mg/L via drinking water immediately after surgery for four months. Rodent chow (Cat# 3002909–203, PicoLab, Fort Worth, Texas) contained B12 at 79 μg/kg [

14].

Biochemical analysis: One and four months after surgery, spot urine was collected before being euthanized. Blood and tissues were collected after euthanasia. Plasma cystatin C, Endothelin-1 (ET-1), corticosterone, and urinary albumin were measured by ELISA kits. (MSCTC0, DET100, R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN; 80556, Crystal Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL; Albuwell M kit #1011, Ethos Biosciences, Logan Township, NJ). Mouse urine creatinine was measured by an enzymatic assay kit (80350, Crystal Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL).

Morphological examination: After perfusion with 0.1% heparin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned (5 μm), then stained with Masson’s Trichrome and hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) [

15,

16]. Semi-quantification of tubular injury was performed by an investigator who was blinded to the experimental groups. For each kidney section, five fields per slide were captured under a standard field of view using light microscopy (Olympus BX43, Tokyo, Japan). The standardized field size was estimated using scale-calibrated images on imaging software. Images were captured with cellSENS Microscope Imaging Software (Evident Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Blood Pressure Measurement: Systolic blood pressure was measured using non-invasive tail-cuff photoplethysmography machine (Visitech BP-2000) at one month and four months post-surgery [

17].

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Tissues were collected and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde/2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 for 1 hour at room temperature and stored at 4°C until processing. Approximately 3 sections (2mm) of cortex were dissected out and were washed with 0.15M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) three times for 5 minutes each then incubated in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Ultrathin sections (80 nm) were cut using a diamond knife on a Leica UCT7 ultramicrotome and applied to 200 mesh copper grids. Grids were stained with 4% aqueous uranyl acetate for 12 minutes followed by Reynold’s lead citrate for 8 minutes (Reynolds, 1963). Samples were viewed using a JEOL 1400 Flash transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA) and images were acquired with an AMT NanoSprint61 ActiveVu: High Resolution CMOS TEM camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Woburn, MA) [

18].

Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR): Total RNA from tissues was extracted using TRIzol

® (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. mRNA was quantified with TaqMan qRT-PCR (QuantStudio 3 real-time PCR systems, ThermoFisher Scientific, Foster City, CA) by using the one-step qRT-PCR Kit (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA) with

18s as the reference gene in each reaction. The 2

–ΔΔCt method was used for comparing the data. The sequences of primers and probes used are listed in

Table S1.

RNA Sequencing: Total kidney RNA was extracted using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Library preparation and sequencing were performed by High Throughput Sequencing Facility (HTSF) at UNC-Chapel Hill. Paired-end raw sequences of 100 bp were acquired by NextSeq 2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA), and subsequent demultiplexing was performed using bclconvert with a 1-mismatch threshold to segregate reads based on indexes. Raw sequencing reads were preprocessed using FASTP to remove adapters and trim poly-G tails. The trimmed reads were then aligned to the Ensemble gene database (release 113) using the SALMON aligner. The gene count matrices were generated and extracted from the SALMON quantification files. The raw counts were then filtered and normalized for the subsequent differential gene expression analysis using relevant Bioconductor packages in R studios (Posit Software, PBC Version 2024.12.1+563).

Statistical analysis: The data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated. A multifactorial analysis of variance test was used with the program JMP® Pro 17.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Group differences were analyzed using one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For one-way ANOVA, pairwise comparisons were conducted using Student’s t-tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Elmo1H/H Mice Had Severely Compromised Kidney Function Than WT Counterparts Four Months After IRI

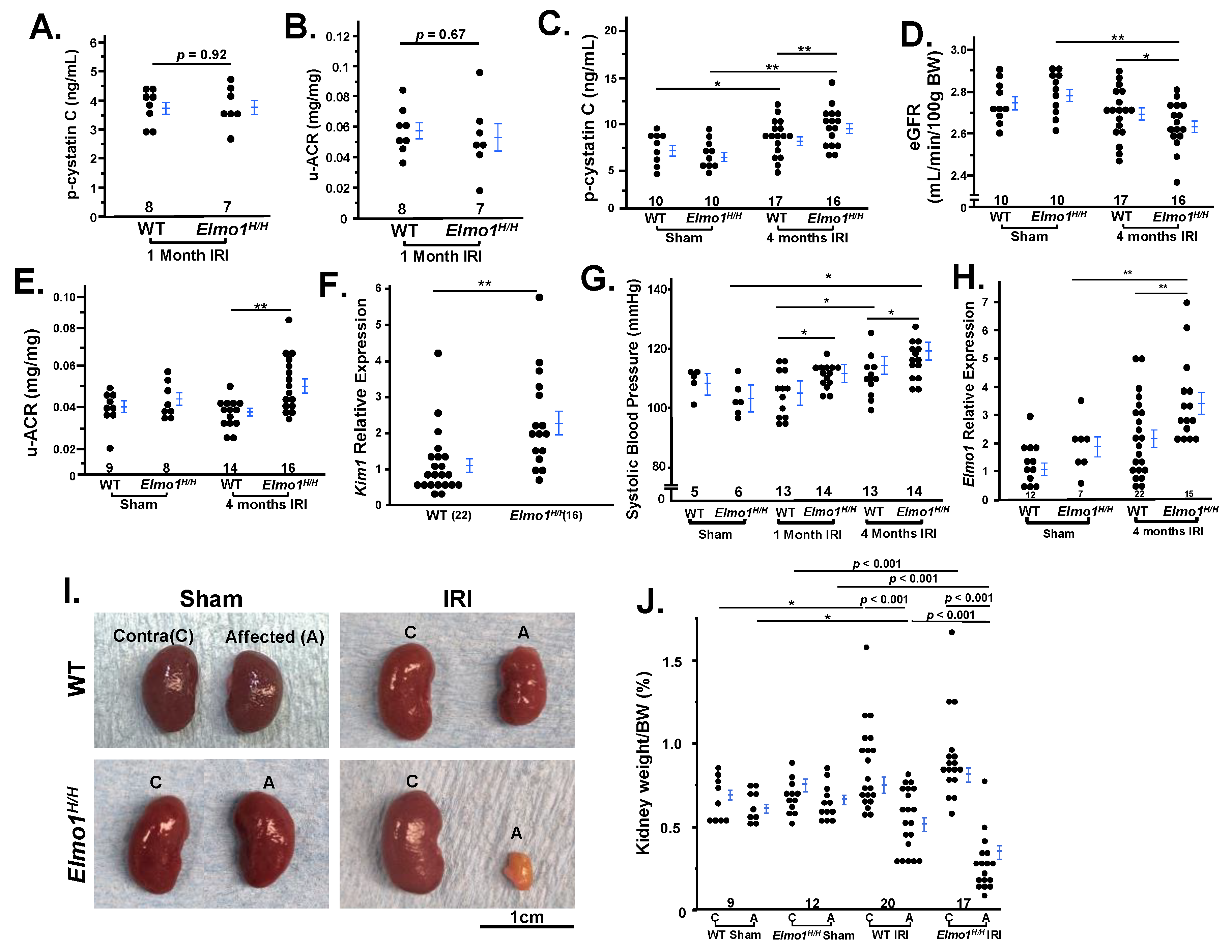

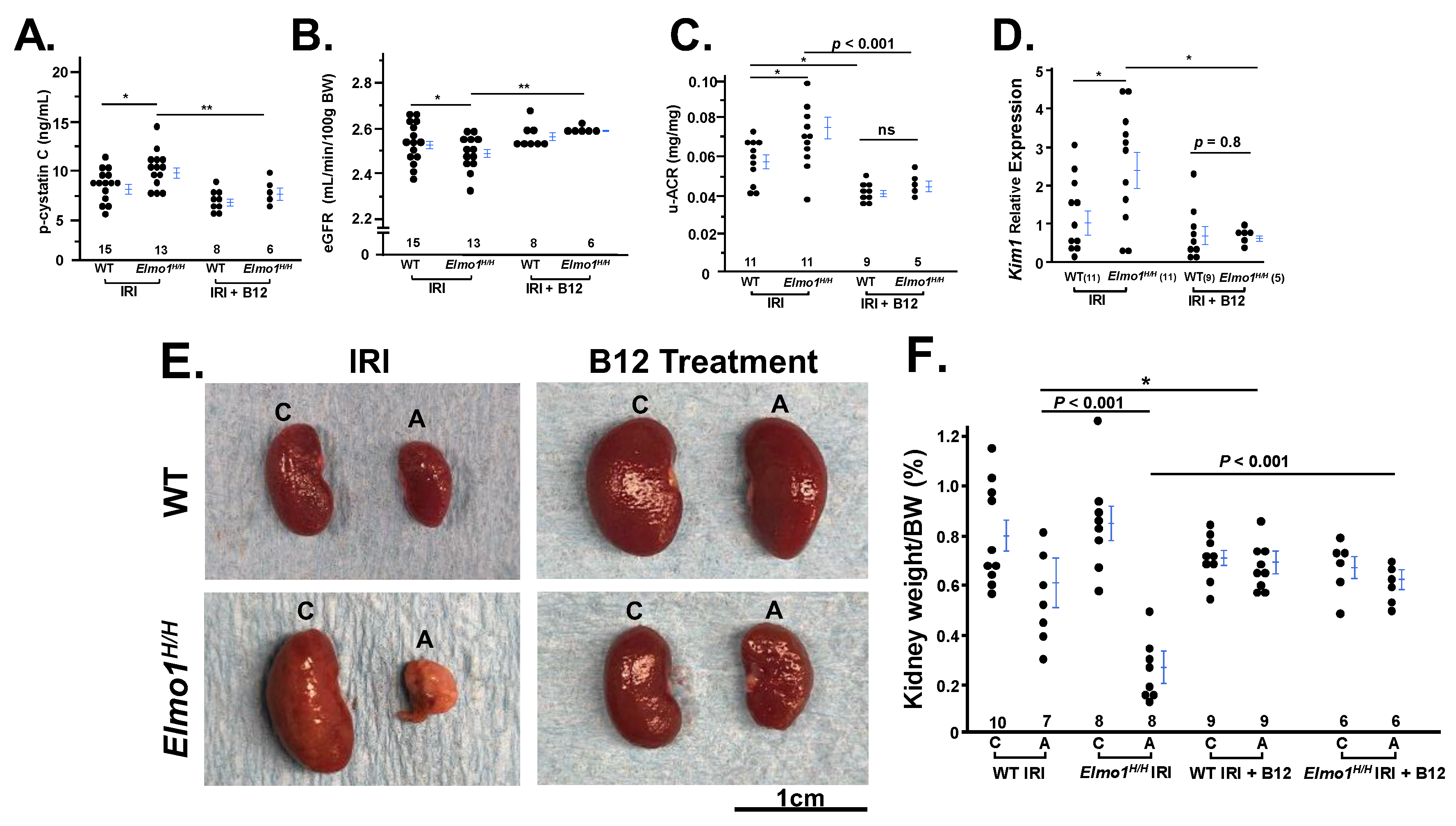

We evaluated overall renal injury and dysfunction by measuring plasma cystatin C, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (u-ACR), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) as complementary indicators of kidney function [

19]. One month after IRI, we observed no significant difference in the kidney functions between

Elmo1H/H and WT groups (

Figure 1A,B). Four months after IRI, plasma cystatin C levels increased in WT and

Elmo1H/H mice, to a significantly greater extent in

Elmo1H/H mice (

Figure 1C). eGFR decreased in

Elmo1H/H mice (

Figure 1D) while these mice had higher u-ACR (

Figure 1E). Kidney injury molecule 1 (Kim1) is a transmembrane damage marker associated with inflammation and fibrosis [

20,

21]. It is encoded by

Kim1 gene, and its expression was more than twice as high as the expression in contralateral kidneys of

Elmo1H/H mice compared with WT (

Figure 1F), demonstrating that increased

Elmo1 accelerates IRI-induced renal damage and dysfunction in mice during the CKD progression.

As kidneys regulate hormones and electrolytes [

22], we observed an earlier and greater rise in systolic blood pressure (SBP) in

Elmo1H/H mice after at one month IRI and remained elevated throughout, while WT showed a later rise; by four months both groups exceeded sham controls and

Elmo1H/H mice still had higher SBP than WT counterparts (

Figure 1G).

Elmo1H/H mice had 2x higher mRNA level of

Elmo1 compared with WT as expected (

Figure 1H). Endothelin 1 (ET-1) plays an important role in AKI-CKD progression [

23]. IRI mice in both groups had higher plasma ET-1 than their sham counterparts and surprisingly,

Elmo1H/H mice at four months had significantly lower ET-1 than in WT after IRI, (

Figure S1A). Plasma corticosterone levels did not show statistic difference among the four groups of mice (

Figure S1B).

Four months after IRI, both WT and

Elmo1H/H mice showed loss of renal mass in the IRI kidney, with greater atrophy in

Elmo1H/H (

Figure 1I). About 25% of

Elmo1H/H IRI kidneys appeared pale, suggesting poor circulation and/or fibrosis [

24]. Contralateral kidneys remained at approximately 1% of body weight and showed compensatory enlargement (

Figure 1J). When evaluating the relationship between contralateral kidney size and affected kidney size, we noticed sham mice showed little variation between the two kidneys (

Figure S2A). Compensatory growth of the contralateral kidneys post-IRI appeared to be limited in the WT mice and two thirds of the

Elmo1H/H mice (

Figure S2B). Three out of 14

Elmo1H/H mice had further growth compensation of the contralateral kidneys. Affected kidneys of those mice had severe atrophy (0.2% of body weights). These findings indicate that

Elmo1 overexpression worsens injury while enhancing compensatory remodeling of the uninjured kidney.

There was no difference between WT and

Elmo1H/H mice underwent sham surgery (

Figure 1)

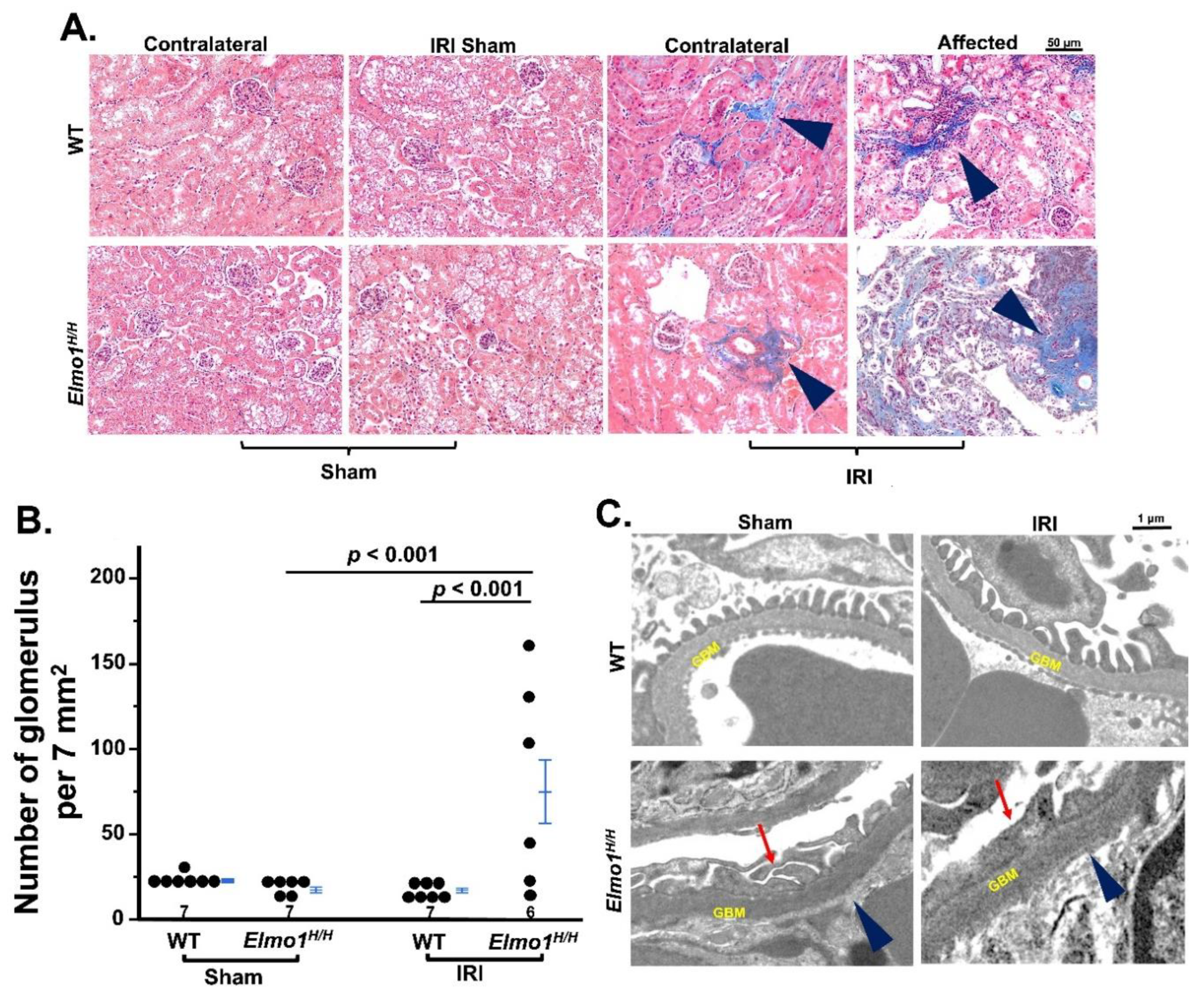

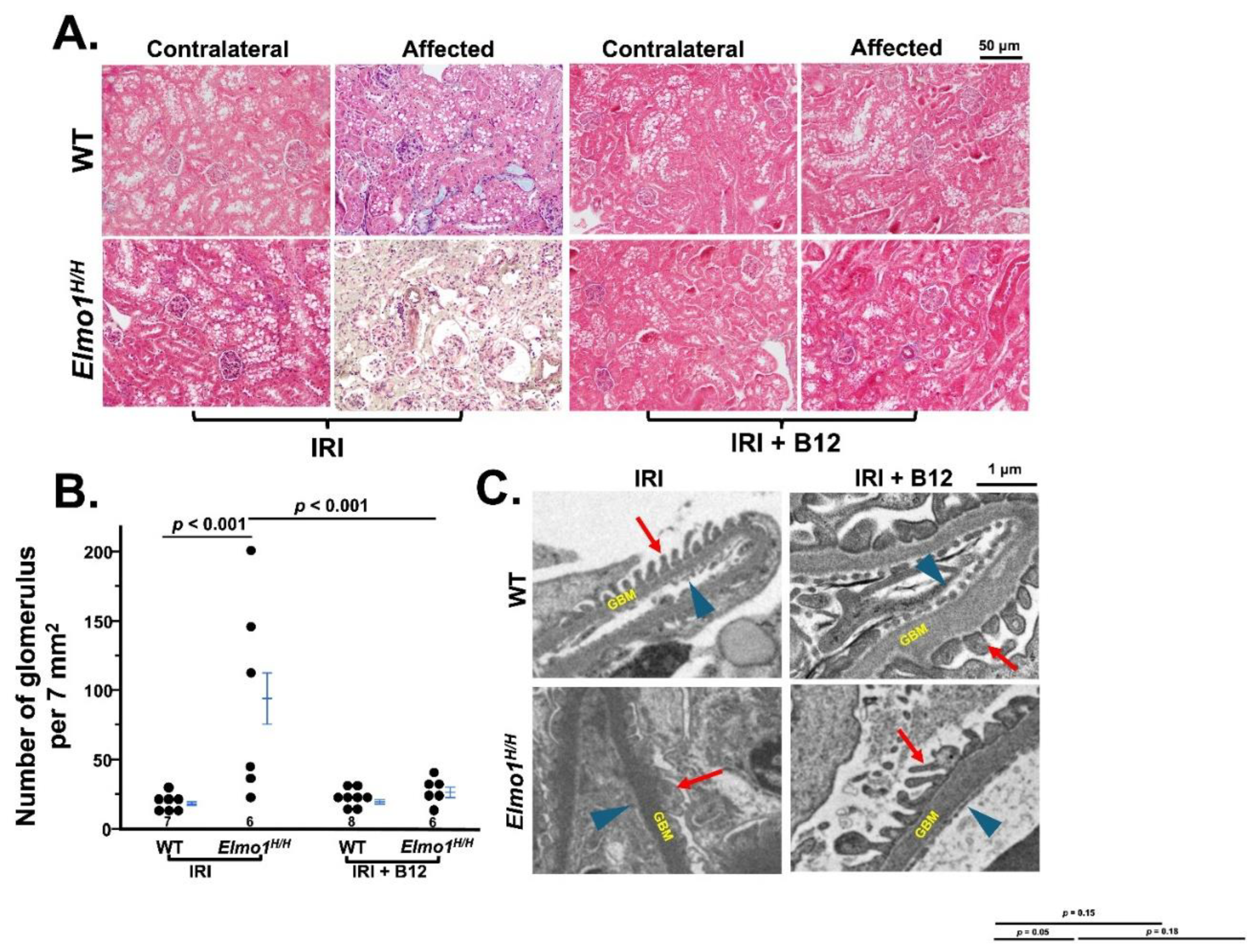

Elmo1H/H Mice Had More Severe CKD-like Morphological Changes, Especially in the Affected Kidneys

Next, we evaluated the histological changes of kidneys at four months after surgery. Under light microscopy, there were no remarkable changes at one month after surgery (

Figure S3A). After four months, the evaluation of fibrosis by Masson’s trichrome staining showed that

Elmo1H/H mice had more severe tubulointerstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis in both IRI and contralateral kidneys than WT counterparts (

Figure 2A) [

25]. Tubular atrophy and loss were seen in affected kidneys in

Elmo1H/H mice, as evidenced by clusters of glomeruli, reflected in higher glomerular number per field (

Figure 2A,B). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) examination in the affected kidneys showed loss of endothelial fenestration, podocyte foot effacement, and loss of slits in glomeruli, which was not present in WT counterparts [

26,

27] (

Figure 2C). Sham kidneys did not show any obvious abnormalities in WT and

Elmo1H/H mice under light microscope and TEM (

Figure 2A,C).

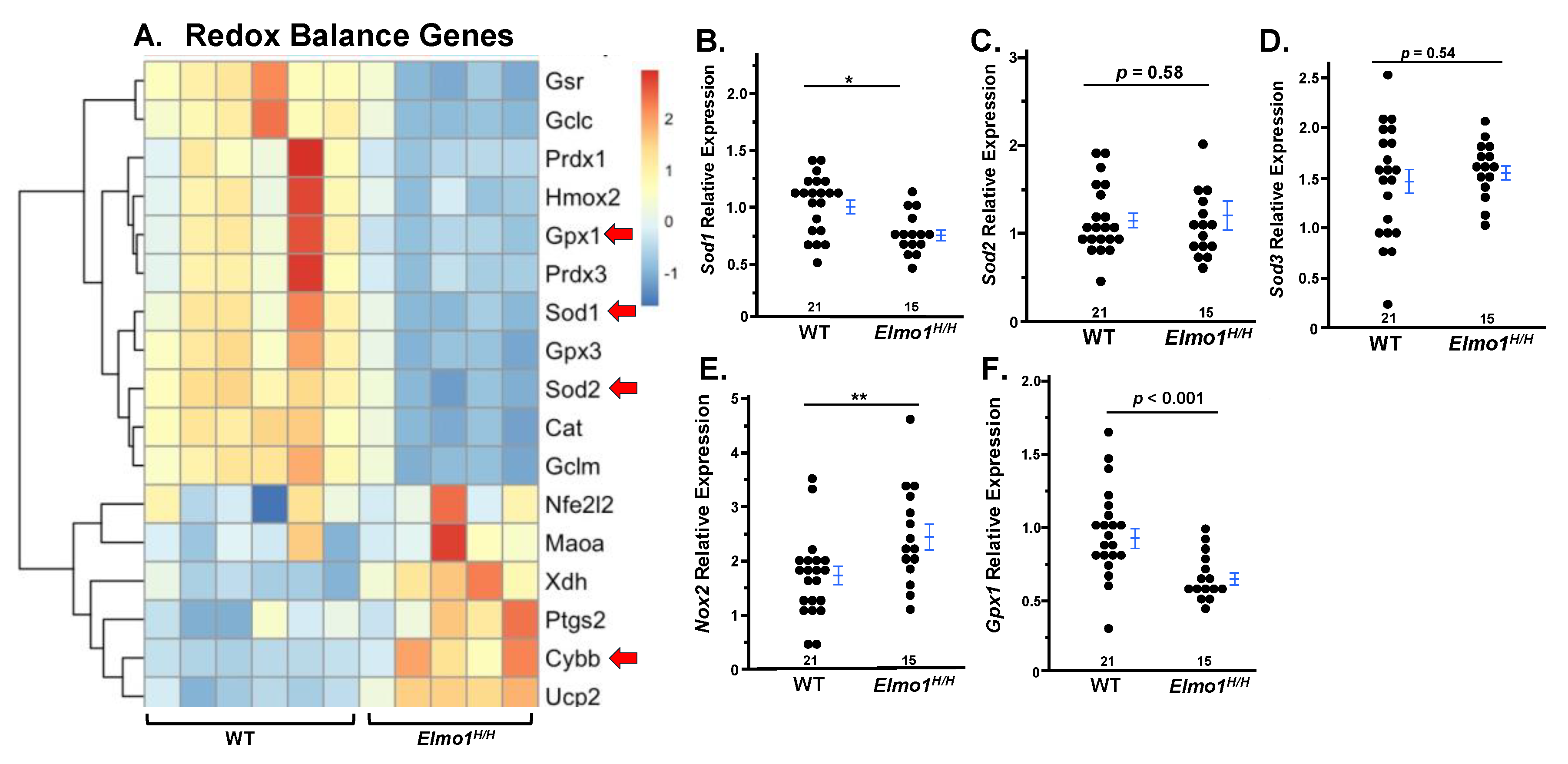

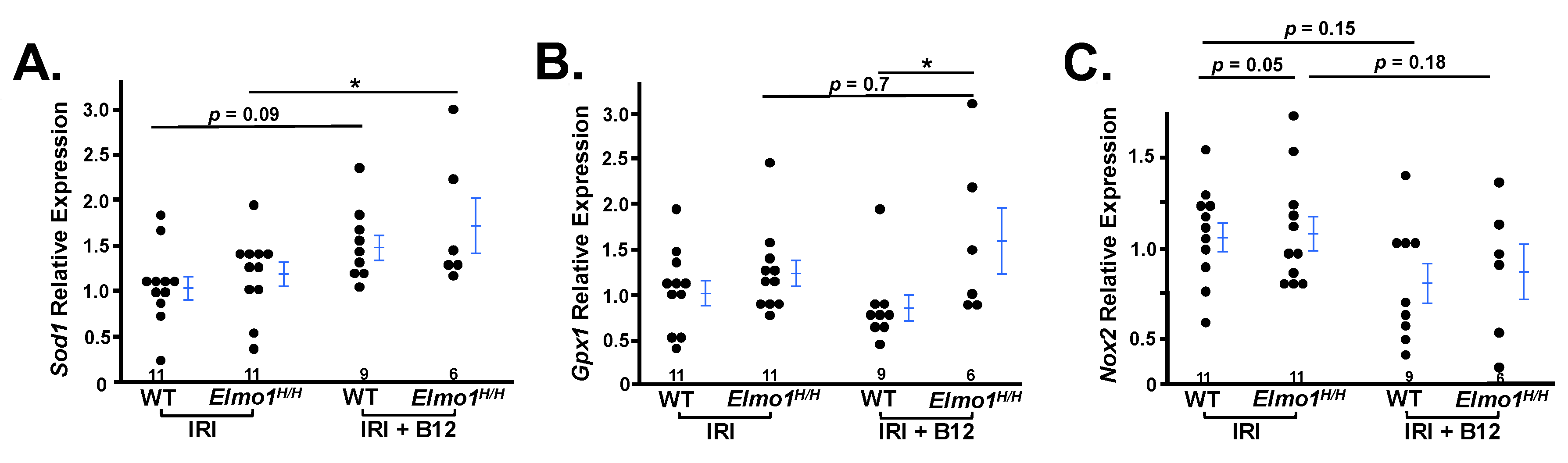

Elmo1H/H Mouse Kidneys Showed Redox Imbalance Four Months After IR Surgery

To investigate the molecular basis of kidney function four months after IRI, we analyzed RNA expression patterns by RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq). We used six WT and five

Elmo1H/H affected kidneys. The samples were selected as their affected kidney weight over their contralateral kidney weight fell within the average range (0.62 ± 0.057% in 20 WT, 0.44 ± 0.062% in 17 Elmo

1H/H). Because ROS plays an important role in CKD progression and severity [

28], and

Elmo1 overexpression is linked to increased ROS in diabetic cardiomyocytes [

12]. Therefore, we assessed the expression of genes related to redox system four months after surgery. RNA-seq analysis of affected kidneys revealed a significant disruption of redox balance between WT and

Elmo1H/H groups, with

Elmo1H/H mice showing impaired antioxidant responses (

Gpx1, Gpx3, Cat) and upregulation of pro-oxidant genes (

Ptgs2, Cybb, Ucp2) in

Elmo1H/H kidneys, potentially contributing to tissue injury and fibrogenesis as shown under histological examination (

Figure 3A).

Superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1) is a key cytosolic enzyme encoded by

Sod1 that converts superoxide radicals into hydrogen peroxide. Its gene expression was markedly reduced in contralateral kidneys from

Elmo1H/H mice with IRI compared to WT counterparts (

Figure 3B), while no differences in

Sod2 or

Sod3 were observed (

Figure 3C,D).

Glutathione peroxidase 1 (Gpx1), an essential antioxidant enzyme that detoxifies hydrogen peroxide to water, was also downregulated in

Elmo1H/H mice with IRI (

Figure 3E).

NADPH oxidase 2 (

Nox2), a major pro-oxidant gene increased ~2.5-fold (

Figure 3F), indicating redox imbalance in the contralateral kidney, and confirmed

Elmo1’s role in enhancing ROS production.

Because oxidative stress is a key driver of tissue remodeling and chronic progression in kidney injuries [

29,

30], we next examined whether redox imbalance in

Elmo1H/H mice was accompanied by changes in fibrotic and inflammatory pathways. Heatmaps showed a consistent trend of upregulated gene profiles in

Elmo1H/H mice, with increased expression of

Tgf-β, Col1a1, Col4a1, Fn1, and

Vim, consistent with extracellular matrix deposition [

31,

32,

33,

34], tubular dedifferentiation, and maladaptive remodeling (

Figure S4). Fibrosis- and inflammation-related gene expressions in contralateral kidneys largely mirrored changes in IRI kidneys, indicating a systemic response. Although many changes were not statistically significant, the pattern suggests fibrosis extends beyond the injured kidney. Inflammatory genes displayed a similar trend, with

Il6 and

Tnfα elevated,

Tlr4 suppressed [

35], and acute chemokines

Ccl2 and

Cxcl1 reduced, consistent with chronic-phase suppression of immune trafficking [

36] (

Figure S5). These findings parallel the redox imbalance observed in affected kidneys, as sustained oxidative stress can amplify fibrotic and inflammatory signaling pathways. Together, the data indicate that

Elmo1-driven ROS accumulation exacerbates local injury and promotes inter-kidney crosstalk, leading to systemic oxidative stress–linked fibrosis and maladaptive remodeling.

Vitamin B12 (B12) Markedly Improved the Kidney Function and Structure Four Months After IR Surgery

Since B12 is a potent antioxidant, and we have previously demonstrated that B12 acute supplementation decreases renal superoxide and post-IRI in mice [

14,

37], we evaluate whether B12 protect the severe phenotypes of CKD noted in

Elmo1H/H mice. Following four months of vitamin B12 treatment, both WT and

Elmo1H/H mice exhibited improved kidney function relative to untreated IR groups. Plasma cystatin C levels and u-ACR in B12-treated mice were closer to sham levels, indicating preserved glomerular filtration and reduced kidney damage, along with the restoration of eGFR in both injury groups (

Figure 4A,C).

Kim1 mRNA level was also significantly lower in the B12 treated group compared to IRI group (

Figure 4D). B12 treatment preserved renal mass and kidney weight in both genotypes (

Figure 4E,F).

Chronic vitamin B12 treatment also significantly attenuated kidney structural and morphological injury following IRI, as demonstrated by both light and electron microscopy. Masson’s trichrome staining revealed a marked reduction in interstitial and vascular fibrosis in B12-treated mice (

Figure 5A), as indicated by a lower glomerular count per field of view compared to vehicle-treated counterparts (

Figure 5B), reflecting preservation of tubular and interstitial spaces and notable preservation of glomerular architecture in both WT and

Elmo1H/H IRI groups. Histological evaluation also revealed reduced tubular atrophy and restored cortical perfusion, suggesting improved oxygen delivery to the lateral kidney border (

Figure 5A). On the ultrastructural level, electron microscopy confirmed that B12 treatment preserved podocyte foot processes, endothelial fenestration, and glomerular basement membrane structure, reversing the extensive cellular damage observed in vehicle-treated

Elmo1H/H mice (

Figure 5C).

We further compared gene expression profiles between treated and untreated groups. We specifically analyzed the expression of key oxidative stress–related genes involved in antioxidant defense. In B12-treated mice, expression of antioxidant genes

Sod1 and

Gpx1 was significantly increased (

Figure 6A,B), indicating restoration of redox homeostasis. Additionally,

Nox2 expression was reduced, suggesting decreased oxidative stress during the adaptive repair phase (

Figure 6C) [

38]. These results support the role of vitamin B12 in enhancing antioxidant capacity and mitigating ROS-mediated damage in the context of IRI.

Collectively, the data suggest that the beneficial effects of B12 are mediated through its antioxidant function, which likely contribute to the attenuation of chronic kidney disease progression.

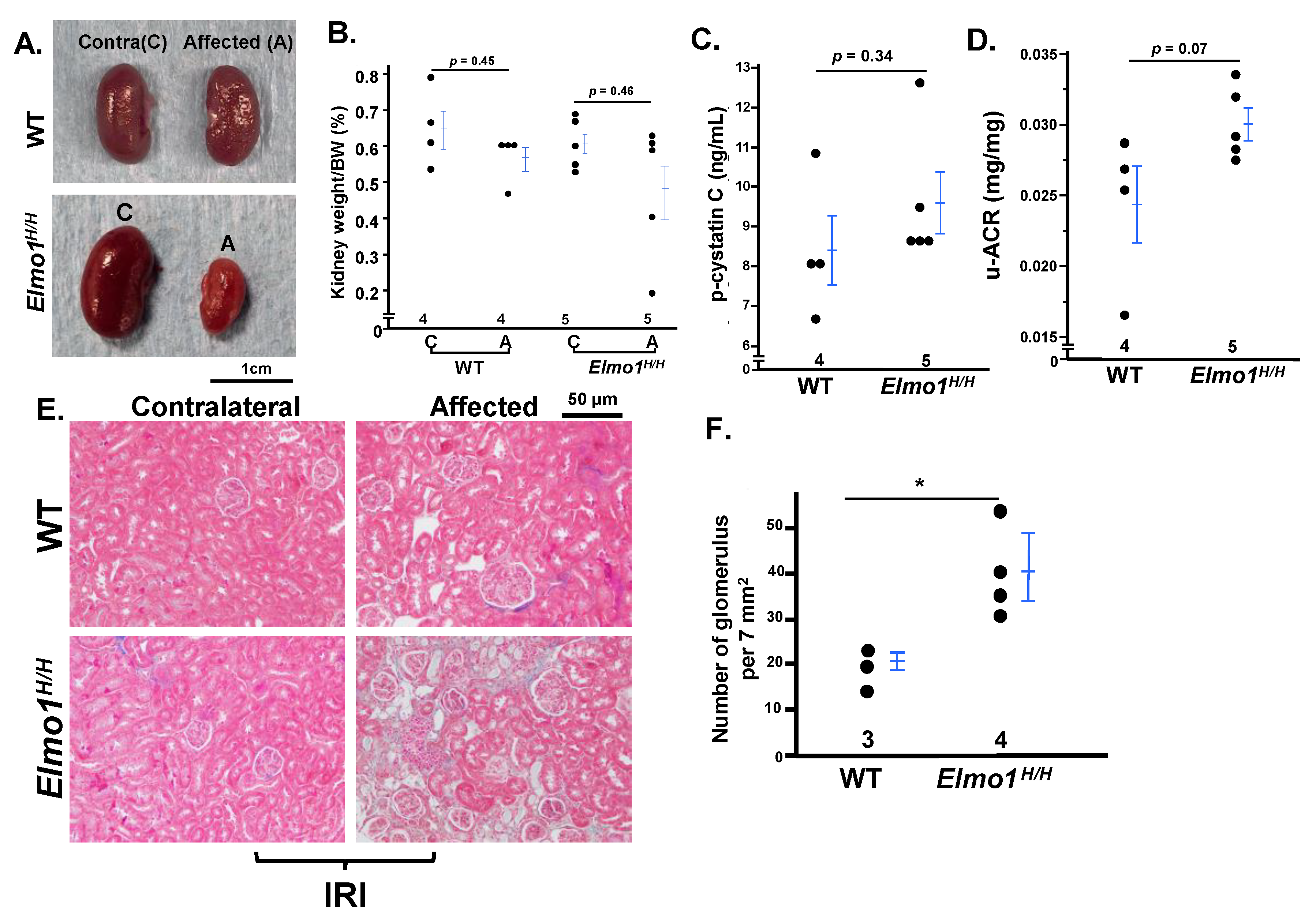

Female Mice Developed Less Severe CKD-like Phenotypes After IRI Than Males Four Months After IRI, While Effects Of High Elmo1 Persisted

Although CKD is more prevalent in women [

1],

Elmo1H/H female mice developed only mild CKD-like phenotypes at four months after IR, less severe than males. They showed moderate increased plasma cystatin C and u-ACR, slight kidney weight loss, and mild fibrosis (only one mouse out of six mice) (

Figure 7A–E). Notably, glomerular density was higher in

Elmo1H/H females than in WT females, consistent with interstitial tubular loss observed in the male counterparts (

Figure 7F). These observations align with reports of sex-specific differences in AKI-to-CKD progression in mice [

39], but the overexpression of

Elmo1 enhanced CKD progression persisted in females as in males.

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrated that Elmo1 overexpression significantly exacerbates the progression of AKI (induced by IRI) to CKD progression. While the damage at one month after IRI was not obviously different histologically and physiologically. Four months after IR surgery, Elmo1H/H male mice developed more advanced CKD-like phenotypes than WT counterparts. They showed higher plasma cystatin C and u-ACR, and drastic interstitial tubular loss, fibrosis, and glomerular damages. Additionally, antioxidant gene expression was downregulated, while genes involved in superoxide production were upregulated in Elmo1H/H mice, implicating oxidative stress as a key contributor to the aggravated CKD-like phenotype. Consistent with this, we showed that B12 (a potent SOD mimetic) supplementation immediately after surgery completely reversed the severity of CKD in Elmo1H/H mice.

The association between

Elmo1 gene variants and diabetic nephropathy was first reported by Shimazaki et al. Later, Hassan et al. showed ELMO1 polymorphism (rs741301) is associated with nephrotic syndrome [

9,

10]. However, associations with other kidney diseases remain unclear. Here, we demonstrated that mice over-expressing

Elmo1 exhibited severe CKD-like phenotypes progressed from AKI caused by IRI, providing strong evidence for its involvement in broader kidney pathologies. Interestingly, we did not observe overt kidney impairment in either WT or

Elmo1H/H sham-operated mice, suggesting that elevated

Elmo1 levels alone is not sufficient to induce kidney dysfunction, but rather aggravates the progression and severity of disease under stress conditions.

Elmo1 signaling is known to regulate actin-based cytoskeletal dynamics and cell motility, and has also been linked to the activation of NADPH oxidases (Nox), which generate reactive ROS [

12,

28]. In the current study, the increased/decreased expression of antioxidant/superoxide producing genes were observed in both affected and contralateral kidneys in

Elmo1H/H mice, suggesting a systematic role for ROS in the pathogenesis in

Elmo1H/H mice. To test whether CKD progression in this model is through ROS related pathway, we treated mice with IR surgery with B12 because of its potent anti-ROS function. Notably, chronic B12 treatment appeared to attenuate the progression from AKI to CKD, suggesting that oxidative stress play a key role in

Elmo1-driven renal pathology.

B12 (cobalamin) is the largest vitamin, containing a central cobalt atom within a corrin ring [

40]. Although synthesized only by certain bacteria and archaea, cobalamins are essential coenzymes for nearly all life (except plants); in vertebrates, methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin are required for methionine synthase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase [

41]. Once inside the cell, the oxidation state of the cobalt atom is reduced from Co(III) to Co(II) and to Co(I). Prior study has reported that Co(II)balamin is a highly effective intracellular superoxide (O

2• −) scavenger with a reaction rate close to that of superoxide dismutase (SOD) [

42]. Our previous work showed that B12 mitigates IRI-induced AKI by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis, DNA damage response, and apoptosis [

14]. In addition, B12 plays a crucial role in the maintenance of one-carbon metabolism [

43]. It is highly likely that B12 could exert protective effects through mechanisms beyond superoxide scavenging [

44].

In this study, a single high dose of B12 given immediately after IR surgery effectively prevented CKD progression in both WT and

Elmo1H/H mice without adverse effects. However, in patients with kidney impairment, toxic B12 metabolites such as thiocyanate may accumulate, potentially limiting its benefit [

45]. Our previous work showed that much lower doses (1/10 of the current dose) also prevented diabetic cardiomyopathy in mice [

46], suggesting that dose optimization and timing could reduce risks. Extending treatment into the chronic phase may further preserve kidney function, as prior findings demonstrated that B12 reduced acute kidney injury even when administered up to five days post-IRI [

14]. Future studies should determine whether early intervention alone is sufficient and/or if continued therapy is required, guiding optimal strategies for CKD management. Previous interventions, including genetic signaling pathway inhibitors and nephrectomy, have shown limited success in slowing kidney disease progression [

47,

48]. In the current study, B12 presents an attractive, noninvasive therapeutic option. However, the optimal timing for B12 initial administration point as well as duration of treatment remains unclear, as pinpointing the exact transition point from AKI to CKD is also challenging during clinical settings. Future studies should compare early, short-term intervention with prolonged treatment to determine the most effective dose, timing, and duration, guiding the strategic use of B12 to prevent CKD progression.

Our study demonstrates that Elmo1 overexpression significantly accelerates AKI-to-CKD progression by exacerbating oxidative stress following with fibrosis and inflammation, while simultaneously impairing compensatory capacity in the contralateral kidney. This systemic effect underscores the critical role of kidney–kidney crosstalk in disease progression and positions Elmo1 as a promising therapeutic target. We further show that early, high-dose B12 supplementation effectively halts CKD progression in Elmo1H/H mice, likely through its potent antioxidant and cytoprotective actions. These findings expand our understanding of Elmo1’s pathogenic role in kidney injury and support the translational potential of B12, emphasizing the need for future studies to define the optimal timing and dosing strategies to maximize therapeutic benefit while minimizing risk.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

F.L. and N.M.-S. designed the study; F.L., J.Z., Y.W., J.H., Q.M., X.Y., and M.C. carried out experiments; J.Z., F.L., C.J. and N.M.-S. analyzed and interpreted the data; J.Z. drafted and F.L., N.M.-S., Y.W., and Y.K. revised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01HL049277 to N.M. and R01HD101485 to F.L.

Data Sharing Statement

RNA sequencing data are deposited to NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (accession: GSE304219).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guideline for use and care of experimental animals, as approved by the IACUC of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Protocol Number#: 22-229) on September 30, 2022.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wariyapperuma Appuhamillage Niroshani Madushika for advice and Keyi Xue for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclosure

The Microscopy Services Laboratory is supported in part by P30-CA016086. HTSF is supported by the University Cancer Research Fund, NIH-P30-CA016086/P30-ES010126.

References

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: An update 2022. In Kidney International Supplements; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 12, pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, J.; Floege, J.; Fliser, D.; Böhm, M.; Marx, N. Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathophysiologi-cal Insights and Therapeutic Options. Circulation 2021, 143, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, R.; Bridge, J.; Ressel, L.; Scarfe, L.; Sharkey, J.; Czanner, G.; A Kalra, P.; Odudu, A.; Kenny, S.; Wilm, B.; et al. Murine models of renal ischemia reperfusion injury: An opportunity for refinement using noninvasive monitoring methods. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gameiro, J.; Marques, F.; Lopes, J.A. Long-term consequences of acute kidney injury: a narrative review. Clin. Kidney J. 2020, 14, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Widdop, R.E.; Ricardo, S.D. Transition from acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease: mechanisms, models, and biomarkers. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2024, 327, F788–F805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menshikh, A.; Scarfe, L.; Delgado, R.; Finney, C.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, H.; de Caestecker, M.P. Capillary rarefaction is more closely associated with CKD progression after cisplatin, rhabdomyolysis, and ischemia-reperfusion-induced AKI than renal fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2019, 317, F1383–F1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, F.S.; Oliveiros, B.; Carreira, I.M.; Alves, R.; Ribeiro, I.P. Genetic Variants Related to Increased CKD Progression—A Systematic Review. Biology 2025, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Hassan, E.; Elsaid, A.M.; -Elzahab, M.M.A.; El-Refaey, A.M.; Elmougy, R.; Youssef, M.M. The Potential Impact of MYH9 (rs3752462) and ELMO1 (rs741301) Genetic Variants on the Risk of Nephrotic Syndrome Incidence. Biochem. Genet. 2024, 62, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazaki, A.; Kawamura, Y.; Kanazawa, A.; Sekine, A.; Saito, S.; Tsunoda, T.; Koya, D.; Babazono, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Matsuda, M.; et al. Genetic variations in the gene encoding ELMO1 are associated with susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 2005, 54, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, C.K.; Chang, A.S.; Grant, R.; Kim, H.-S.; Madden, V.J.; Bagnell, C.R.; Jennette, J.C.; Smithies, O.; Kakoki, M. High Elmo1 expression aggravates and low Elmo1 expression prevents diabetic nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 2218–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoki, M.; Bahnson, E.M.; Hagaman, J.R.; Siletzky, R.M.; Grant, R.; Kayashima, Y.; Li, F.; Lee, E.Y.; Sun, M.T.; Taylor, J.M.; et al. Engulfment and cell motility protein 1 potentiates diabetic cardiomyopathy via Rac-dependent and Rac-independent ROS production. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wei, Q.; Liu, J.; Yi, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; Peng, Y.; Liu, F.; Venkatachalam, M.A.; et al. AKI on CKD: heightened injury, suppressed repair, and the underlying mechanisms. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Bahnson, E.M.; Wilder, J.; Siletzky, R.; Hagaman, J.; Nickekeit, V.; Hiller, S.; Ayesha, A.; Feng, L.; Levine, J.S.; et al. Oral high dose vitamin B12 decreases renal superoxide and post-ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.H. Masson’s trichrome stain in the evaluation of renal biopsies. An appraisal. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1976, 65, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, A.T.; Wolfe, D. Tissue processing and hematoxylin and eosin staining. In Histopathology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 1180, pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Krege, J.H.; Hodgin, J.B.; Hagaman, J.R.; Smithies, O. A Noninvasive Computerized Tail-Cuff System for Measuring Blood Pressure in Mice. Hypertension 1995, 25, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, E.S. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 1963, 17, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, E.R.; Estiverne, C.; Tolan, N.V.; Melanson, S.E.; Mendu, M.L. Estimated GFR With Cystatin C and Creatinine in Clinical Practice: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Kidney Med. 2023, 5, 100600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, T.; Bonventre, J.V.; Bailly, V.; Wei, H.; Hession, C.A.; Cate, R.L.; Sanicola, M. Kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), a putative epithelial cell adhesion molecule containing a novel immunoglobulin domain, is up-regulated in renal cells after injury. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 4135–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbisetti, V.S.; Waikar, S.S.; Antoine, D.J.; Smiles, A.; Wang, C.; Ravisankar, A.; Ito, K.; Sharma, S.; Ramadesikan, S.; Lee, M.; et al. Blood kidney injury molecule-1 is a biomarker of acute and chronic kidney injury and predicts progression to ESRD in type I diabetes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadei, H.M.; Textor, S.C. The role of the kidney in regulating arterial blood pressure. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2012, 8, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, P.; Vaňourková, Z.; Škaroupková, P.; Kompanowska-Jezierska, E.; Sadowski, J.; Walkowska, A.; Veselka, J.; Táborský, M.; Maxová, H.; Vaněčková, I.; et al. Endothelin type A receptor blockade increases renoprotection in congestive heart failure combined with chronic kidney disease: Studies in 5/6 nephrectomized rats with aorto-caval fistula. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLarnon, S.C.; Johnson, C.; Giddens, P.; O'Connor, P.M. Hidden in Plain Sight: Does Medullary Red Blood Cell Congestion Provide the Explanation for Ischemic Acute Kidney Injury? Semin. Nephrol. 2022, 42, 151280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polichnowski, A.J.; Griffin, K.A.; Licea-Vargas, H.; Lan, R.; Picken, M.M.; Long, J.; Williamson, G.A.; Rosenberger, C.; Mathia, S.; Venkatachalam, M.A.; et al. Pathophysiology of unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury: importance of renal counterbalance and implications for the AKI-CKD transition. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2020, 318, F1086–F1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, N.C.; Neal, C.R.; Welsh, G.I.; Foster, R.R.; Satchell, S.C. The unique structural and functional characteristics of glomerular endothelial cell fenestrations and their potential as a therapeutic target in kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2023, 325, F465–F478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Ricart, M.; Torramade-Moix, S.; Pascual, G.; Palomo, M.; Moreno-Castaño, A.B.; Martinez-Sanchez, J.; Vera, M.; Cases, A.; Escolar, G. Endothelial Damage, Inflammation and Immunity in Chronic Kidney Disease. Toxins 2020, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irazabal, M.V.; Torres, V.E. Reactive Oxygen Species and Redox Signaling in Chronic Kidney Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Sun, H. MiR-556-3p mediated repression of klotho under oxidative stress promotes fibrosis of renal tubular epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyurászová, M.; Gurecká, R.; Bábíčková, J.; Tóthová, Ľ. Oxidative Stress in the Pathophysiology of Kidney Disease: Implications for Noninvasive Monitoring and Identification of Biomarkers. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barwinska, D.; El-Achkar, T.M.; Ferreira, R.M.; Syed, F.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Winfree, S.; Ferkowicz, M.J.; Hato, T.; Collins, K.S.; Dunn, K.W.; et al. Molecular characterization of the human kidney interstitium in health and disease. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigato, M.; Caprara, C.; Cabrera-Aguilar, J.S.; Marzano, N.; Giuliani, A.; Mancini, B.; Gastaldon, F.; Ronco, C.; Zanella, M.; Zuccarello, D.; et al. Collagen Type IV Variants and Kidney Cysts: Decoding the COL4A Puzzle. Genes 2025, 16, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelletti, F.; Donadelli, R.; Banterla, F.; Hildebrandt, F.; Zipfel, P.F.; Bresin, E.; Otto, E.; Skerka, C.; Renieri, A.; Todeschini, M.; et al. Mutations in FN1 cause glomerulopathy with fibronectin deposits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 2538–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramann, R.; DiRocco, D.P.; Maarouf, O.H.; Humphreys, B.D. Matrix-Producing Cells in Chronic Kidney Disease: Origin, Regulation, and Activation. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2013, 1, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Shibuya, A.; Tsuchiya, K.; Akiba, T.; Nitta, K. Reduced expression of Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to impaired cytokine response of monocytes in uremic patients. Kidney Int. 2006, 70, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wu, Z.; He, Y.; Lin, L.; Tan, W.; Yang, J. Interaction Between Intrinsic Renal Cells and Immune Cells in the Progression of Acute Kidney Injury. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 954574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Lagemaat, E.E.; De Groot, L.C.P.G.M.; van den Heuvel, E.G.H.M. Vitamin B12 in Relation to Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, E.; Hallner, A.; Wiktorin, H.G.; Staffas, A.; Hellstrand, K.; Martner, A. NOX2 inhibition reduces oxidative stress and prolongs survival in murine KRAS-induced myeloproliferative disease. Oncogene 2019, 38, 1534–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima-Posada, I.; Portas-Cortés, C.; Pérez-Villalva, R.; Fontana, F.; Rodríguez-Romo, R.; Prieto, R.; Sánchez-Navarro, A.; Rodríguez-González, G.L.; Gamba, G.; Zambrano, E.; et al. Gender Differences in the Acute Kidney Injury to Chronic Kidney Disease Transition. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, D.; Cooke, A.; Young, T.R.; Deery, E.; Robinson, N.J.; Warren, M.J. The requirement for cobalt in vitamin B12: A paradigm for protein metalation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 118896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, C.R. Vitamin B12 in health and disease: part I--inherited disorders of function, absorption, and transport. Gastroenterologist 1995, 3, 329–44. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Moreira, E.; Yun, J.; Birch, C.S.; Williams, J.H.H.; McCaddon, A.; Brasch, N.E. Vitamin B(12) and redox homeostasis: cob(II)alamin reacts with superoxide at rates approaching superoxide dismutase (SOD). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15078–15079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, D.S.; Fowler, B.; Baumgartner, M.R. Vitamin B12, folate, and the methionine remethylation cycle—biochemistry, pathways, and regulation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. The beneficial role of vitamin B12 in injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion: Beyond scavenging superoxide? J Exp Nephrol. 2021, 2, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.D.; Yi, Q.; Hankey, G.J. B vitamins in stroke prevention: time to reconsider. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoki, M.; Ramanathan, P.V.; Hagaman, J.R.; Grant, R.; Wilder, J.C.; Taylor, J.M.; Jennette, J.C.; Smithies, O.; Maeda-Smithies, N. Cyanocobalamin prevents cardiomyopathy in type 1 diabetes by modulating oxidative stress and DNMT-SOCS1/3-IGF-1 signaling. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Yoo, T.-H. TGF-β Inhibitors for Therapeutic Management of Kidney Fibrosis. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kierulf-Lassen, C.; Nielsen, P.M.; Qi, H.; Damgaard, M.; Laustsen, C.; Pedersen, M.; Krag, S.; Birn, H.; Nørregaard, R.; Jespersen, B.; et al. Unilateral nephrectomy diminishes ischemic acute kidney injury through enhanced perfusion and reduced pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic responses. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0190009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).