Submitted:

03 October 2024

Posted:

04 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

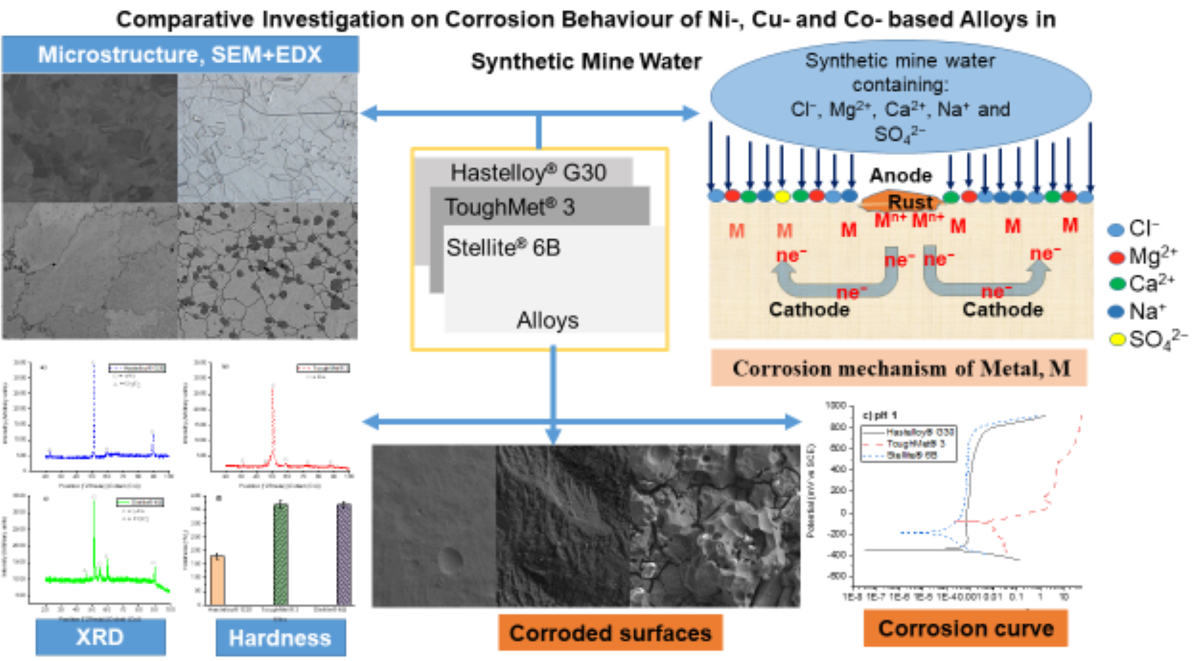

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Microstructures and X-ray Diffraction Characterisation

2.3. Hardness Tests

2.4. Test Solution

2.5. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results

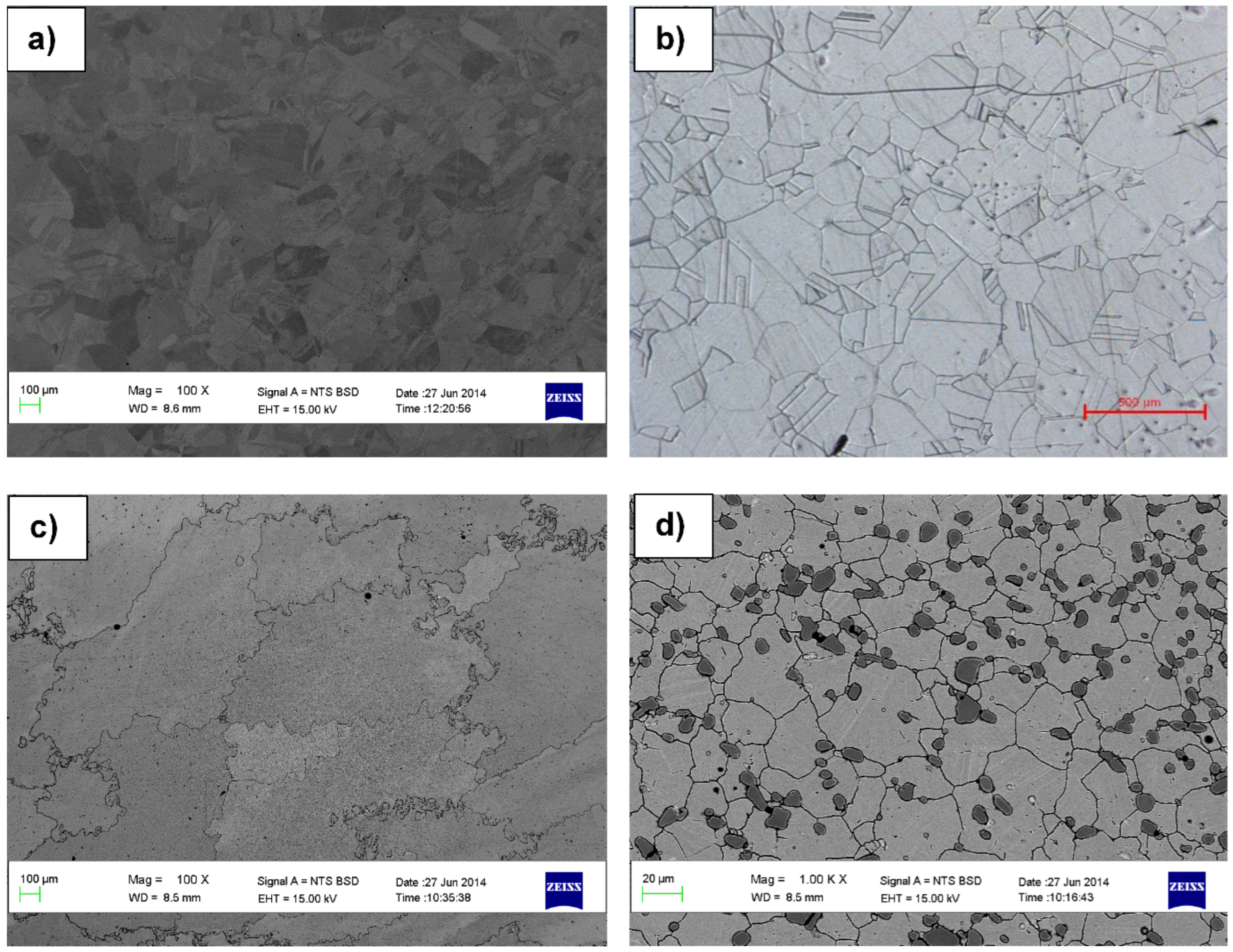

3.1. Microstructural, X-Ray Diffraction and Hardness

| Element (wt%) | Hastelloy® G30 | ToughMet® 3 | Stellite® 6B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Light grey | Dark grey | Overall | Grains | Overall | Light grey | Dark grey | |

| Cu | 1.7±0.3 | 2.3±0.2 | 2.4±0.2 | 78.3±0.2 | 76.7±1.0 | - | - | - |

| Al | 0.2±0.0 | 0.3±0.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ni | 41.8±0.5 | 44.8±0.1 | 44.8±0.3 | 13.9±0.1 | 14.9±1.0 | 1.7±0.1 | 2.1±0.1 | - |

| Si | 0.6±01 | 0.1±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 | - | - | 0.4±0.0 | 0.5±0.0 | - |

| Cr | 29.8±0.2 | 28.8±0.2 | 28.9±0.1 | - | - | 29.5±1.0 | 24.0±0.1 | 75.3±0.3 |

| Co | 2.7±0.1 | 2.3±0.1 | 2.4±0.3 | - | - | 46.2±0.4 | 53.7±0.1 | 9.3±0.1 |

| Fe | 15.3±0.4 | 12.8±0.0 | 12.9±0.1 | - | - | 1.7±0.1 | 1.9±0.1 | 0.6±0.0 |

| Mo | 3.5±0.3 | 5.4±0.1 | 5.3±0.3 | - | - | - | 0.7±0.4 | - |

| Mn | 1.3±0.0 | 1.1±0.1 | 1.0±0.1 | - | - | 1.5±0.1 | 1.6±0.2 | 1.3±0.1 |

| W | 3.3±0.1 | 2.1±0.1 | 2.3±0.1 | - | - | 4.8±0.2 | 5.2±0.2 | 3.1±0.4 |

| Sn | - | - | - | 7.8±0.1 | 8.4±0.4 | - | - | - |

| O | - | - | - | - | - | 7.4±1.0 | 6.5±0.3 | 7.4±1.0 |

| C | - | - | - | - | - | 7.6±1.1 | 3.9±1.0 | 10.6±0.2 |

3.2. Corrosion of the Hard Alloys

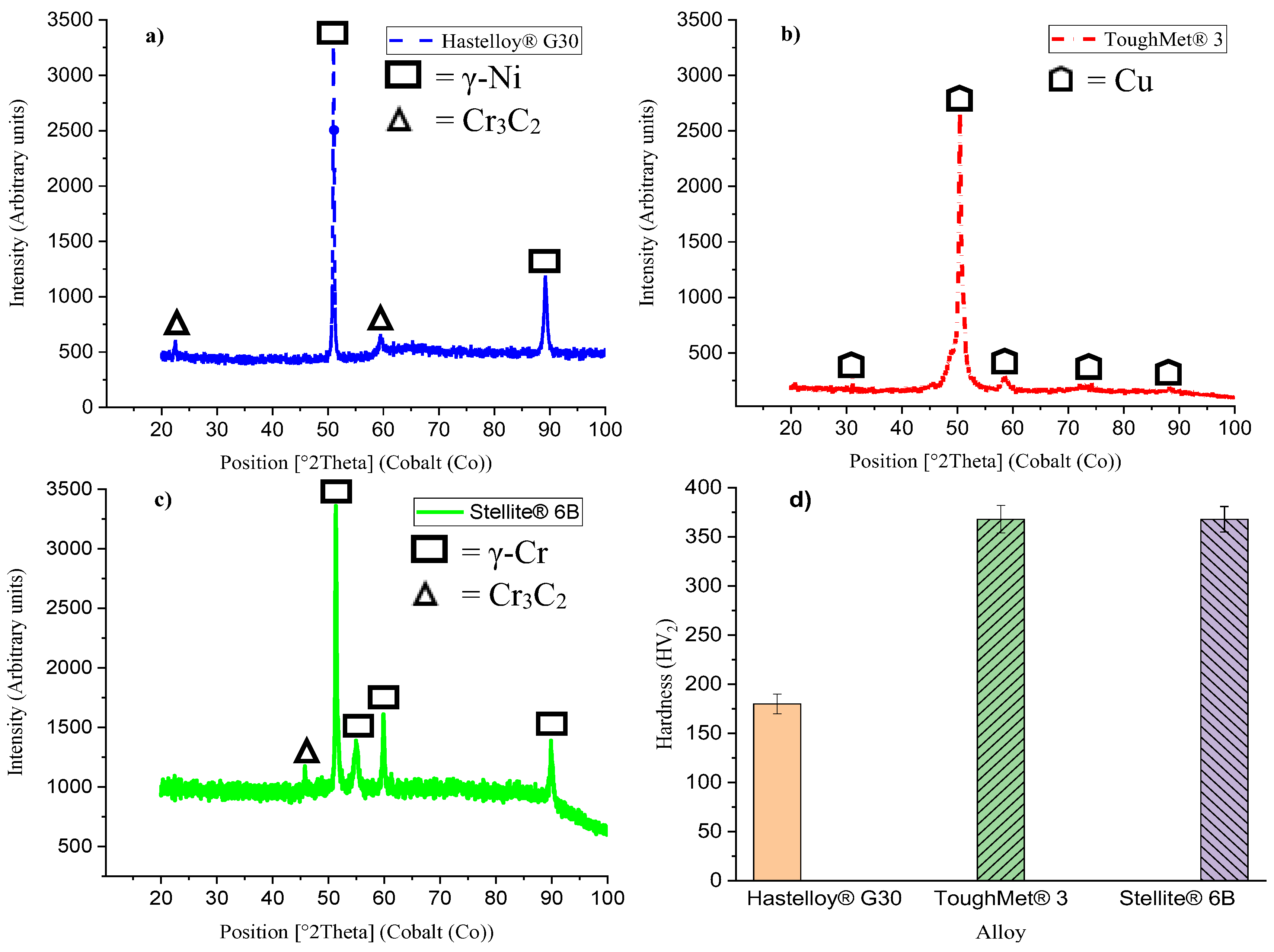

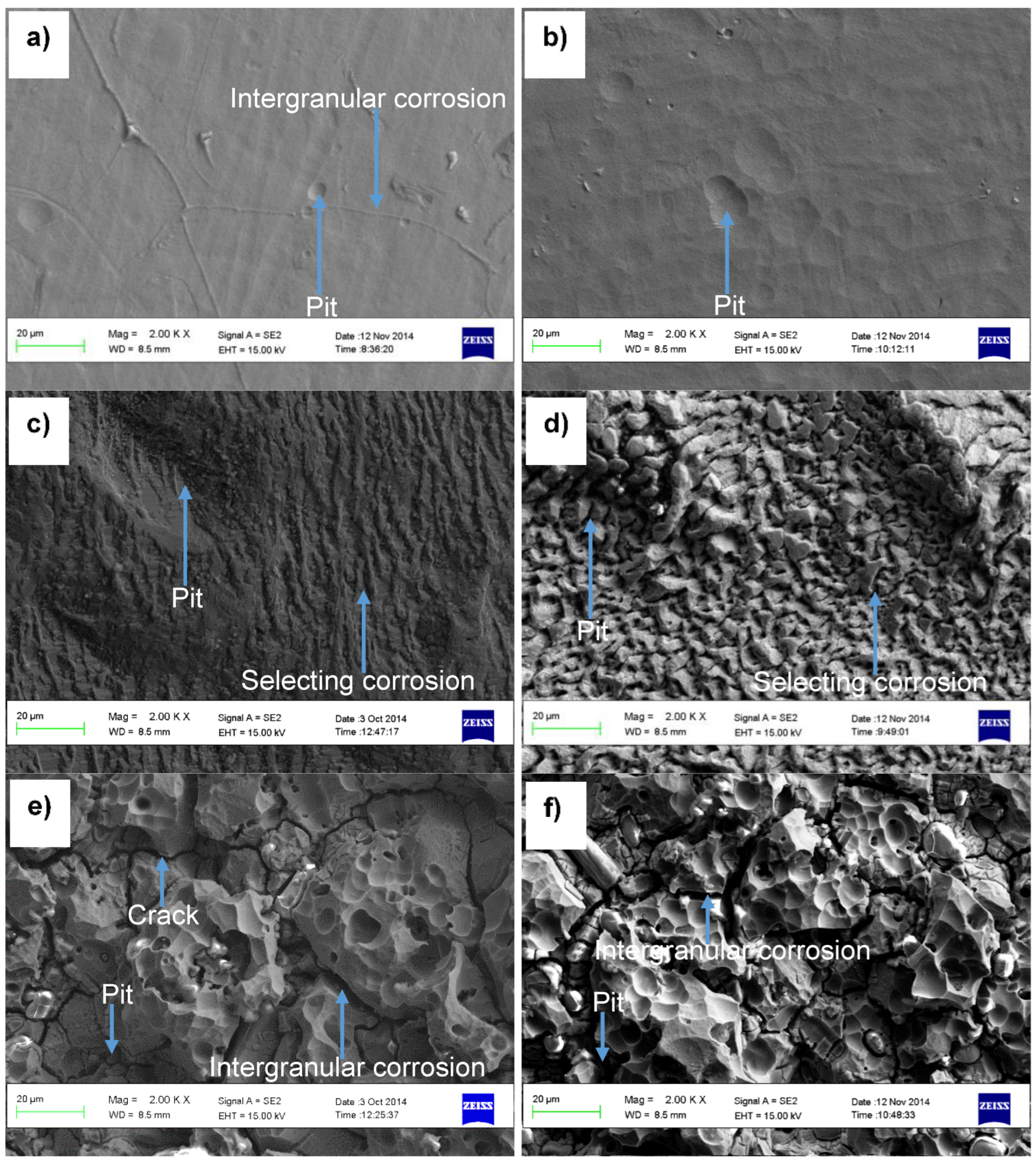

3.2.1. Microscopic Morphologies of the Alloys after Corrosion Tests

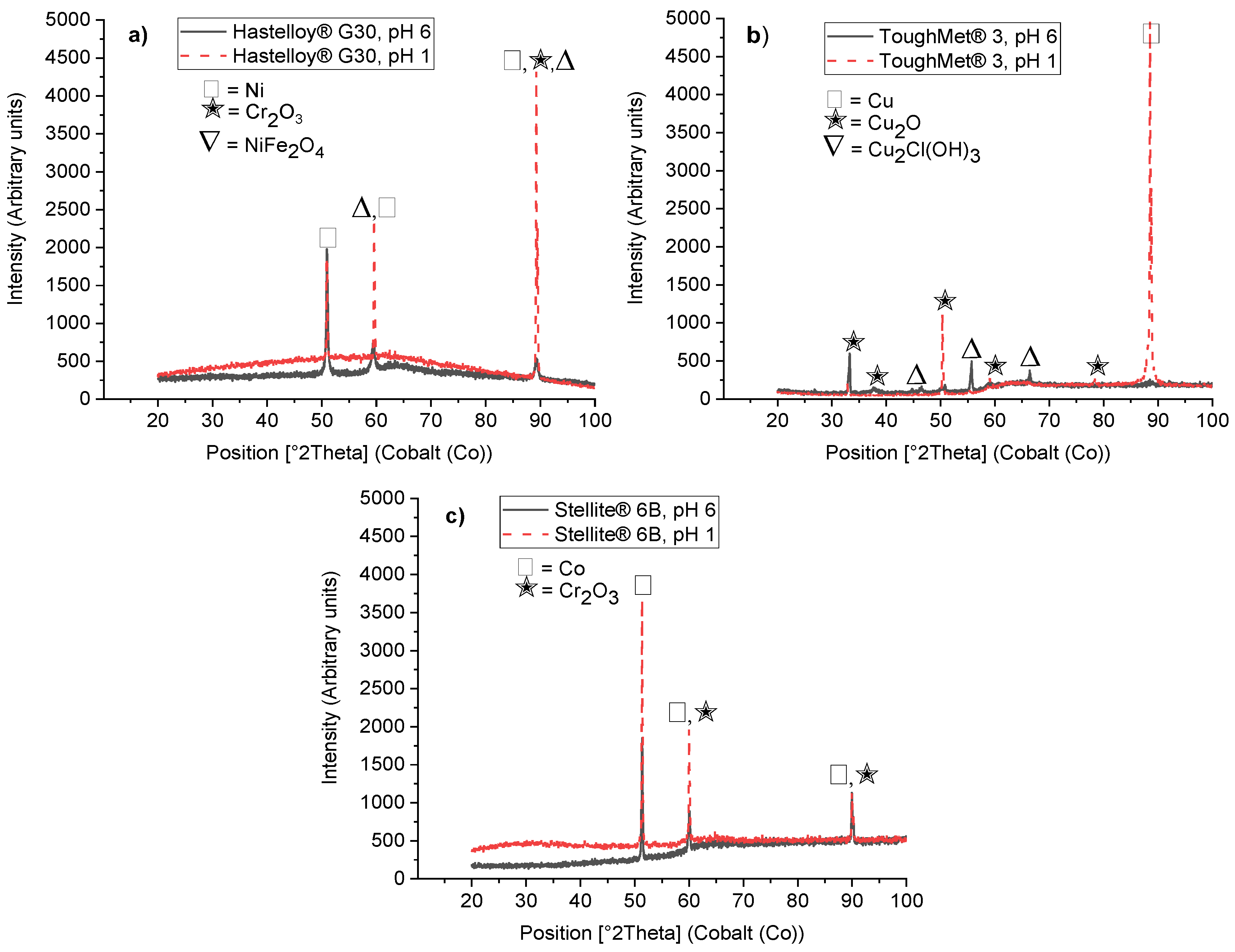

3.2.2. Corrosion Products by XRD Analyses

| Element (wt%) |

pH 6 | pH 3 | pH 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ToughMet® 3 | Stellite® 6B | ToughMet® 3 | Stellite® 6B | ToughMet® 3 | Stellite® 6B | |

| C | - | 14.6±1.0 | - | 11.3±1.0 | - | 6.6±1.0 |

| Ca | 0.4±0.0 | 0.3±0.0 | 0.4±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 | 1.5±1.0 | 0.2±0.0- |

| Cu | 50.4±7.0 | - | 64.4±2.0 | - | 69.0±12.0 | - |

| O | 11.3±2.0 | 8.4±0.3 | 12.9±2.0 | 7.0±0.1 | 12.4±5.0 | 12.6±0.2 |

| Na | 0.1±0.0 | 0.3±0.0 | 0.4±1.0 | 0.2±0.1 | 0.2±0.0- | 0.2±0.0 |

| S | 0.4±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 | 0.3±0.0 | 0.3±0.1- | 0.8±0.1 |

| Cl | 10.0±3.0 | - | 20.3±5.0 | - | 10.0±5.0 | - |

| Cr | - | 26.6±0.1 | - | 27.9±0.3 | - | 29.6±0.2 |

| Mn | - | 1.5±0.0 | - | 1.7±0.2 | - | 1.4±0.1 |

| Fe | - | 1.9±0.0 | - | 2.0±0.0 | - | 1.5±0.0 |

| Co | - | 38.8±0.0 | - | 42.8±1.0 | - | 35.8±0.2 |

| Ni | 0.6±0.0 | - | 0.2±0.0 | 1.0±0.1 | 0.9±0.3 | 1.4±0.0 |

| Mo | - | - | - | 5.5±0.1 | - | 0.9±0.4 |

| W | - | 6.1±1.0 | - | 5.5±0.1 | - | 8.7±0.4 |

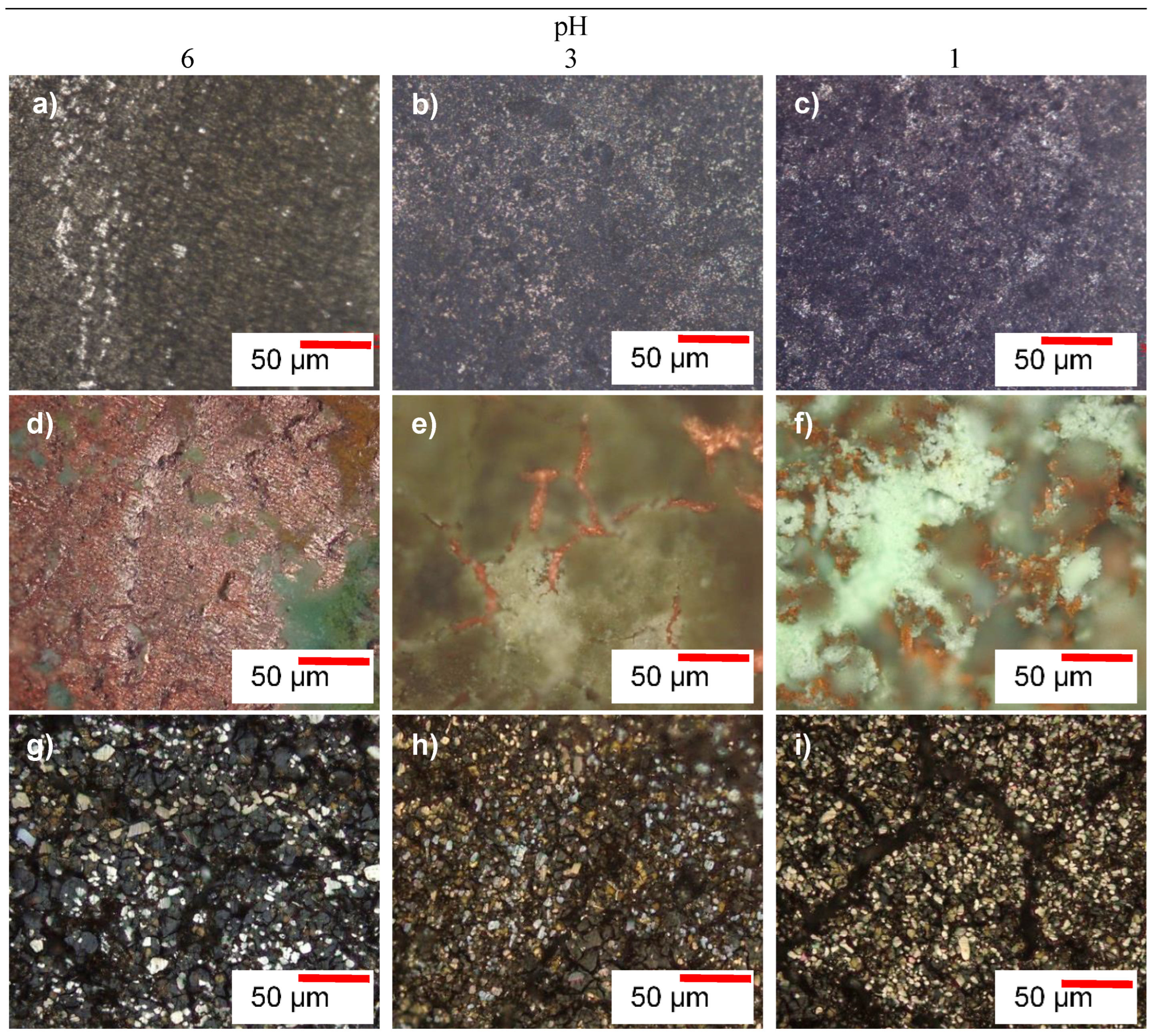

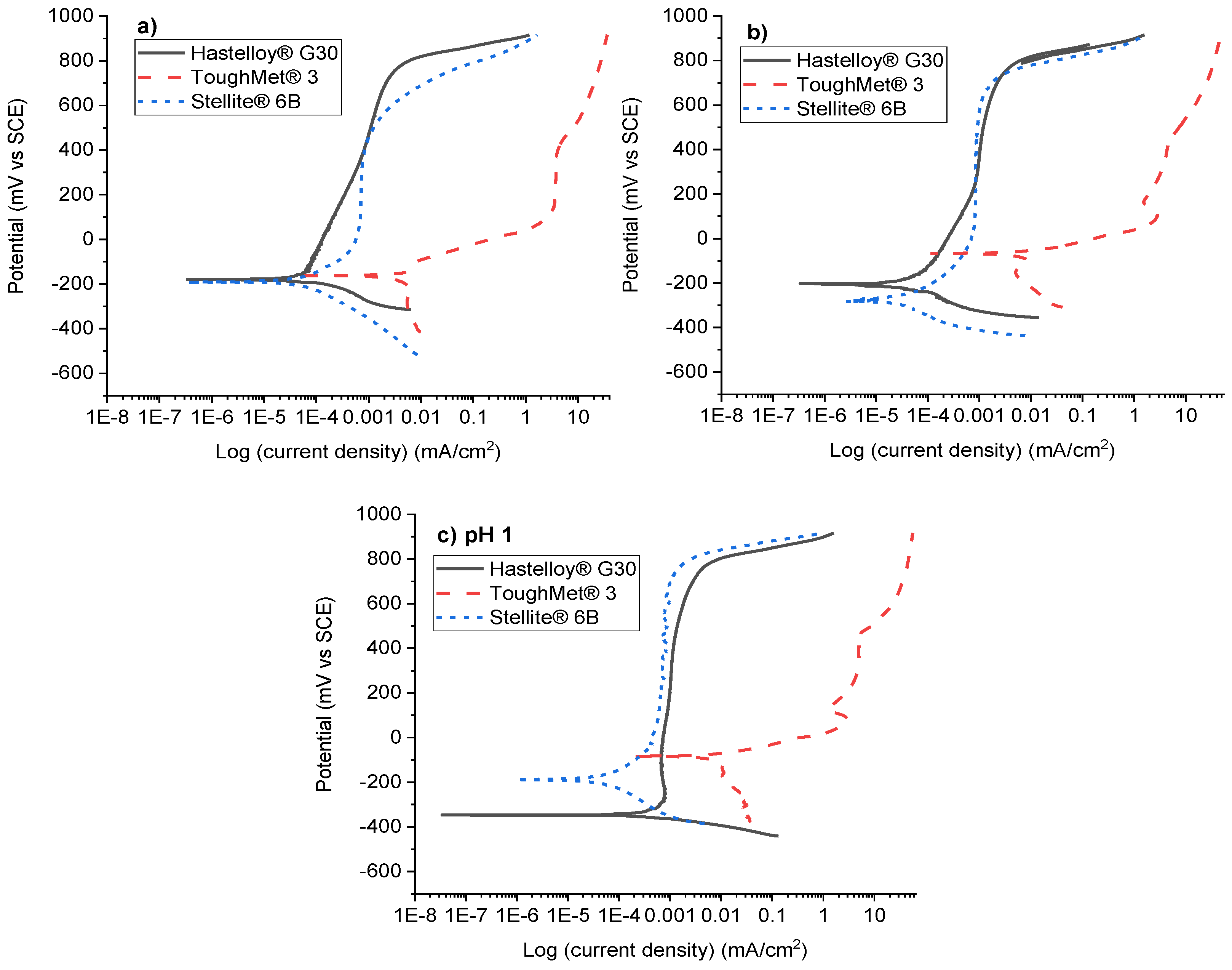

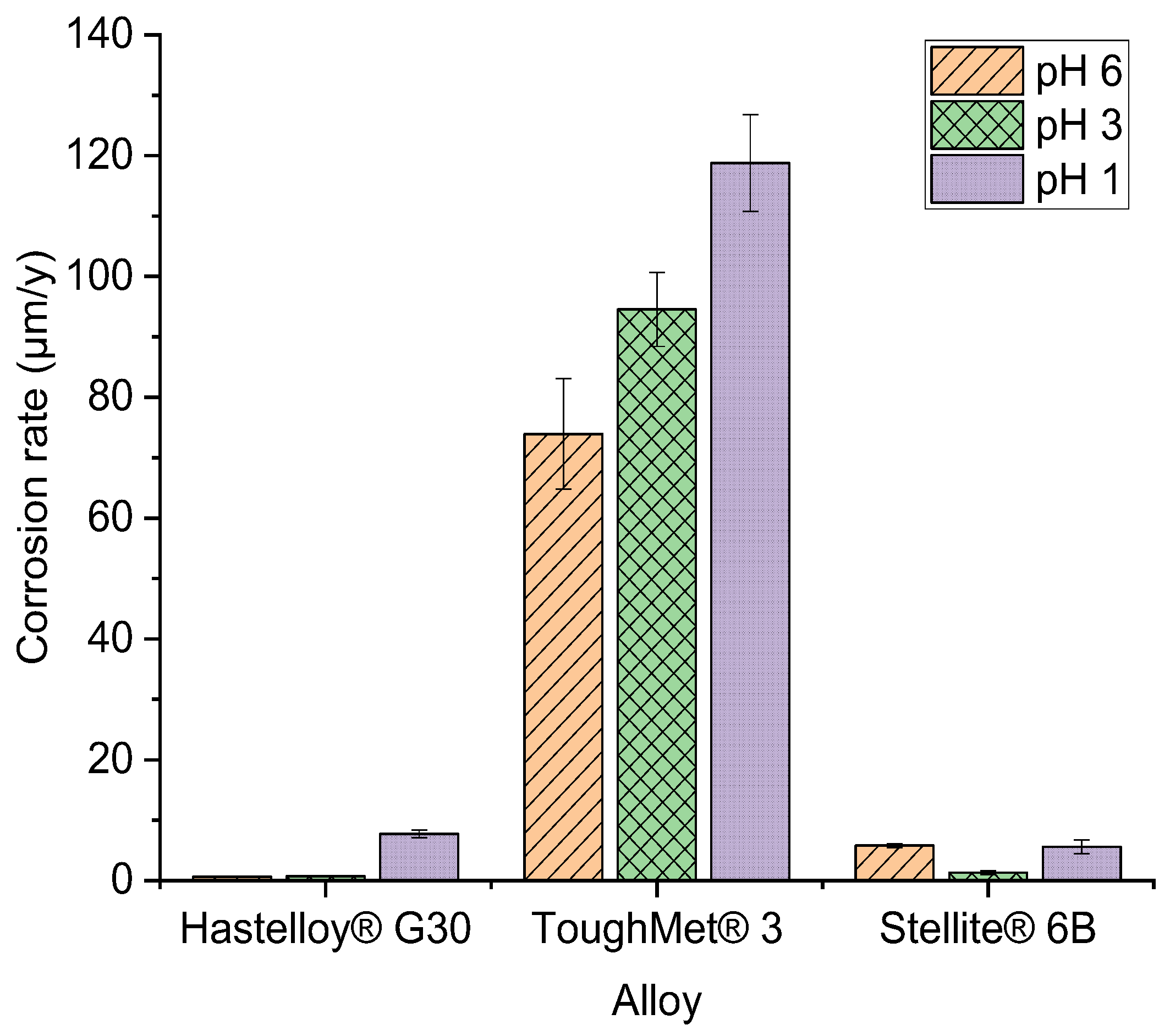

3.3. Electrochemical Results

| pH | Bulk alloy | Ecorr (mV) | icorr (µA/cm2) | Corrosion rate (µm/y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Hastelloy® G30 | -179.4±2.4 | 0.063±0.001 | 0.63±0.01 |

| ToughMet® 3 | -162.5±3.2 | 6.1±0.4 | 73.93±9.12 | |

| Stellite® 6B | -191.7±1.3 | 0.13±0.02 | 5.81±0.33 | |

| 3 | Hastelloy® G30 | -202.2±2.6 | 0.074±0.00 | 0.74±0.05 |

| ToughMet® 3 | -67.2±1.3 | 7.8±0.6 | 94.54±6.11 | |

| Stellite® 6B | -283.2±3.1 | 0.13±0.04. | 1.32±0.34 | |

| 1 | Hastelloy® G30 | -347.1±3.3 | 0.071±0.001 | 7.75±0.64 |

| ToughMet® 3 | -83.9±1.7 | 9.8±0.7 | 118.78±8.00 | |

| Stellite® 6B | -182.8±4.1 | 0.058±0.004 | 5.61±1.13 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Microstructures of the Hard Alloys

4.2. Hardness of the Alloys

4.3. Potentiodynamic Polarisation Behaviours of the Hard Alloys

5. Conclusions

- Hastelloy® G30 composed of irregular and equiaxed shape γ-Ni grains with twinning and Cr3C2, ToughMet® 3 showed large and irregular grains, while Stellite® 6B consisted of γ-Co grains with twinning and large Cr3C2 precipitated at the grain boundaries.

- The presence of twins and Cr3C2 phases in the Hastelloy® G30 and Stellite® 6B alloys determine their hardness levels.

- Hastelloy® G30 and Stellite® 6B alloys displayed active-passive transition behaviours due to their ability to form protective thin films, and exhibited pitting and intergranular corrosion, while ToughMet® 3 experienced pseudo-passivation behaviour, pitting and selective corrosion in synthetic mine water at all pH values.

- The Stellite® 6B alloy experienced the lowest corrosion at pH 3 (1.32±0.34 µm/y), and then pH 1 (5.61±1.13 µm/y) and pH 6 (5.81±0.33 µm/y). It also had the highest hardness as ToughMet® 3 (368±13 HV2) than the Hastelloy® G30 (180±10 HV2) alloy.

- Stellite® 6B emerges as the optimal alloy to substitute mild steel in industrial applications, particularly in components for slurry pumps like casings, sleeves, and valves, where both corrosion resistance and hardness are to be considered.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hango, S.I.; Cornish, L.A.; van der Merwe, J.W.; Chown, L.H.; Kavishe, F.P.L. Corrosion Behaviour of Cobalt-Based Coatings with Ruthenium Additions in Synthetic Mine Water. Results Mater. 2024, 21, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherly International, Central Operations Executive Summary. Available online: https://weatherlyplc.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/WI-Central-Ops-Exec-Sum_v2-17-06-13.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Li, H.; Oraby, E.; Eksteen, J. Extraction of Precious Metals from Waste Printed Circuit Boards Using Cyanide-Free Alkaline Glycine Solution in the Presence of an Oxidant. Miner. Eng. 2022, 181, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitiya, R.; Jacob, L.; Emilinot, R.J. A Pilot Study on the Concentration of Heavy Metals in Sediments from the Lower Orange River, //Karas Region, Namibia. J. Mater. Sci. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes International, HASTELLOY® G-30 Alloy: Principal Features. Available online: https://www.haynesintl.com/alloys/alloy-portfolio_/Corrosion-resistant-Alloys/HASTELLOY-G-30-alloy (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Guo, C.; Shi, S.; Dai, H.; Yu, J.; Chen, X. Corrosion Mechanisms of Nickel-Based Alloys in Chloride-Containing Hydrofluoric Acid Solution. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 140, 106580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bai, S.L.; Ge, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.Y. Erosion-corrosion Behavior and Electrochemical Performance of Hastelloy C22 Coatings Under Impingement. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 456, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Y.; Zhang, X.S.; Zheng, H.B.; Liu, T.Y.; Dong, L.J.; Zhang, J.; Xi, Y.C.; Zeng, D.Z.; Lin, Y.H.; Luo, H. Intergranular Corrosion Mechanism of Sub-Grain in Laser Additive Manufactured Hastelloy C22 Induced by Heat Treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 608, 155140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xu, D.; Jiang, G.; Kuang, W. Corrosion Behavior and Mechanism of Ni-Based Alloys Hastelloy C2000 and Inconel 740 in Chloride-Containing Supercritical Water Oxidation. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 907, 164452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Qian, L.; Li, Y.; Lin, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhang, W. Corrosion Behavior of Nickel Base Alloys, Stainless Steel and Titanium Alloy in Supercritical Water Containing Chloride, Phosphate and Oxygen, Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2015, 100, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materion, Brush Peformance Alloys: Problematic Bearing Applications. 2020. Available online: https://multialloys.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/toughmet-brochure.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Loto, R.T. Correlative Investigation of the Corrosion Susceptibility of C70600 and C26000 Copper Based Alloys for Application in Seawater Environment. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 2151–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.X.; Li, X.N.; Wei, K.R.; Li, Z.M.; Zheng, Y.H.; Li, N.J.; Cheng, X.T.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, Q.; Dong, C. Cu–Ni–Sn–Si Alloys Designed by Cluster-Plus-Glue-Atom Model. Mater. Des. 2019, 167, 107641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.C.; Wang, Z.B.; Hu, H.X.; Zheng, Y.G. Understanding Localized Corrosion Mechanism of 90/10 Copper-Nickel Alloy in Flowing NaCl Solution Induced by Partial Coverage of Corrosion Products Films. Corros. Sci. 2024, 227, 111716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidah, I.; Solehudin, A.; Hamdani, A.; Hasanah, L.; Khairurrijal, K.; Kurniawan, T.; Mamat, R.; Maryanti, R.; Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Hammouti, B. Corrosion of Copper Alloys in KOH, NaOH, NaCl, and HCl ELectrolyte Solutions and its Impact to the Mechanical Properties. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 2235–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, D.; Jegadeeswaran, N.; Somasundaram, B.; Raju, B.S. Corrosion Resistance by HVOF Coating on Gas Turbine Materials of Cobalt Based Superalloy. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 20, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hango, S.I.; Cornish, L.A.; Chown, L.H.; van der Merwe, J.W.; Kavishe, F.P.L. Sliding Wear Resistance of the Co-balt-Based Coatings, ULTIMETTM and STELLITETM 6 with Ruthenium Additions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 155, 107717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, A.; Khullar, P.; Bouknight, C.; Gilbert, J.L. Corrosion properties of Low Carbon CoCrMo and Additively Manufactured CoCr Alloys for Dental Applications. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Schmitt, T.; Bousser, E.; Vernhes, L.; Khelfaoui, F.; Perez, G.; Klemberg-Sapieha, J.E.; Brochu, M. Microstructural and Mechanical Characterization of Stellite-Hardfaced Coatings with Two Types of Buffer Layers. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 390, 125611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Falcon, C.M.; Gil-Lopez, T.; Verdu-Vazquez, A.; Mirza-Rosca, J.C. Electrochemical characterization of some cobalt base alloys in Ringer solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 260, 124164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangtong, P.; Rodchanarowan, A.; Chaysuwan, D.; Chanlek, N.; Goodall, R. The corrosion behaviour of CoCrFeNi-x (x = Cu, Al, Sn) high entropy alloy systems in chloride solution. Corros. Sci. 2020, 172, 108740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennametal Stellite, Wrought Wear-Resistant Alloy. Available online: https://www.stellite.com/us/en/products/stellite-6b.html (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Hango, S.I. Failure of Pump Systems Operating in Highly Corrosive Mine Water at Otjihase Mine, PhD Thesis, Uni-versity of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2018. Available online: http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/25666.

- Al-Qawabah, S.; Mostafa, A.; Al-Rawajfeh, A.; Al-Qawabeha, U. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Grain Size, Microhardness and Corrosion Behavior of the Cold-Working Tool Steels Aisi D2 and Aisi O1. Mater. Tehnol. 2020, 54, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; Wang, L.; Wu, K. Corrosion Behavior and Passive Film Properties of Nickel-Based Alloy in Phosphoric Acid, Corros. Commun. 2023, 9, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Chen, L.Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Zhao, C.H.Y.; Lu, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L.C. Corrosion Behavior and Mechanism of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Produced Cocrw in an Acidic NaCl Solution. Corros. Sci. 2023, 213, 110999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzi, A.C.; Ramos, F.D.; Vargas, D.B.O. Microabrasive Wear Behavior of Different Stellites Obtained by Laser Cladding and Casting Processes. Wear 2023, 524–525, 204857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; de Villiers Lovelock, H.L.; Davies, S. Sliding wear of Blended Cobalt Based Alloys. Wear 2021, 466–467, 203533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krell, J.; Röttger, A.; Theisen, W. Comprehensive Investigation of the Microstructure-Property Relationship of Differently Manufactured Co–Cr–C Alloys at Room and Elevated Temperature. Wear 2020, 444–445, 203138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Li, Y.; Ni, S.; Wang, Z.; Song, M. Microstructural and Hardness Evolutions of a Cold-Rolled Cobalt. Mater. Sci. Eng. : A 2021, 803, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, P.S.; Tiwari, A.; Seman, S.; Mohamed, S.A.B.; Jayaganthan, R. Erosion-Corrosion Protection due to Cr3C2-NiCr Cermet Coating on Stainless Steel. Coatings 2020, 10, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Cui, H.; Yang, S.; Lv, S.; Xie, X.; Qu, J. Effect of Carbon Addition on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of a Typical Hard-to-Deform Ni-Base Superalloy. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2023, 33, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlaček, M.; Zupančič, K.; Šetina Batič, B.; Kosec, B.; Zorc, M.; Nagode, A. Influence of Precipitation Hardening on the Mechanical Properties of Co-Cr-Mo and Co-Cr-W-Mo Dental Alloys. Metals 2023, 13, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaprakash, N.; Yang, C.H.; Karuppasamy, S.S.; Duraiselvam, M. Stellite 6 Cladding on AISI Type 316L Stainless Steel: Microstructure, Nanohardness and Corrosion Resistance. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2023, 76, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y. Li, L., Yin, W., Chu, C., and Guan, Y. Investigation of Corrosion Behavior and Film Formation on 90Cu-10Ni Alloys Immersed in Simulated Seawater. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaprakash, N.; Yang, C.H.; Karuppasamy, S.S.; Dhineshkumar, S.R. Evaluation of Microstructure, Nanoindentation and Corrosion Behavior of Laser Cladded Stellite-6 Alloy on Inconel-625 Substrate. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Jiang, W.; Chen, G.; Luo, J.; Fan, Y.; Jin, Q.; Xie, J.; Feng, Y.; Xie, J. Study on Corrosion Behavior of 13Cr Gate Valve Using Weld Deposited Gate and Seat in Well Operation Environments. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 148, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Tang, N.; Onodera, E.; Chiba, A. Corrosion behaviour of CoCrMo alloys in 2 wt% sulphuric acid solution. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 125, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolenska, H. Cobalt Base Clad Layer Resistance on the Corrosion Under Low Sulfur Pressure. Solid State Phenom. 2010, 165, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, V.; Kannoorpatti, K. Corrosion Behaviour of High Chromium White Iron Hardfacing Alloys in Acidic and Neutral Solutions. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros. 2016, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, W.; Anurag, A.; Pahlevani, F.; Hossain, R.; Privat, K.; Sahajwalla, V. Effect of selective-precipitations process on the corrosion resistance and hardness of dual-phase high-carbon steel. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Talib, N.; Al-Gebory, L. Investigation of Corrosion Behavior of Carbon Steel for Petroleum Pipeline Applications Under Turbulent Flow Conditions. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 36, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Qin, Y.; Dilimulati, D.; Wang, Y. The Effect of Chlorine Ion on Metal Corrosion Behavior under the Scratch Defect of Coating. Int. J. Corros. 2019, 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xu, D.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Macdonald, D.D. Corrosion Characteristics and Mechanisms of Typical Ni-Based Corrosion-Resistant Alloys in Sub- and Supercritical Water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2021, 170, 105138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, C. Comparative Investigation on Corrosion Behavior of Laser Cladding C22 Coating, Hastelloy C22 Alloy and Ti–6Al–4V Alloy In Simulated Desulfurized Flue Gas Condensates. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 18, 2194–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cao, R.; Xu, L.; Qiao, L. The Role of Hydrogen in the Corrosion and Cracking of Steels - A Review. Corros. Commun. 2021, 4, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, Z.; Ahonen, M.; Virkkunen, I.; Nevasmaa, P.; Rautala, P. Study of Cracking and Microstructure in Co-Free Valve Seat Hardfacing. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2022, 31, 101202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).