1. Introduction

Corrosion of metal substrates, particularly carbon steel, is a significant issue that affects the structural integrity, safety, and economic viability of infrastructure and industrial assets globally [

1]. Among the protection methods, the application of protective coatings is considered the most practical and effective solution to minimize corrosion damage [

2]. In this field, silicate-based inorganic zinc-rich (IOZ) coatings have long been recognized as the standard for long-term corrosion protection in harsh operating environments, such as marine environments and industrial atmospheres [

3].

The primary protection mechanism of zinc-rich paints is based on galvanic protection, in which a high zinc powder content (>80 wt% in the dry film) provides sacrificial cathodic protection to the underlying steel substrate [

4]. This is complemented by the formation of a tough, ceramic-like silicate matrix during curing, which provides superior thermal stability and abrasion resistance [

5]. To further enhance performance, hybrid pigment systems are often incorporated. The addition of flake pigments, such as zinc-aluminium (Zn-Al), has been shown to improve barrier properties by creating a “zigzag diffusion pathway” that hinders the transport of corrosive agents to the steel surface, thereby synergistically combining barrier protection and galvanic protection mechanisms [

6,

7].

Despite the proven efficacy, the constant drive for improved durability and environmental sustainability has fueled research into new additives. One attractive avenue is the development of “green” corrosion inhibitors derived from plants, in response to increasing regulatory and environmental pressure to replace traditional toxic inhibitors such as hexavalent chromium compounds [

8]. Plant extracts are rich in phytochemicals containing heteroatoms (N, O, S) and π electron systems, which facilitate adsorption onto metal surfaces, form a protective molecular film, and inhibit electrochemical reactions during corrosion [

9].

Among the many candidates,

Lawsonia inermis extract stands out due to its availability, low cost, and non-toxic nature [

10,

11]. The main active ingredient, lawsone (2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone), is believed to play a central role in the inhibition mechanism by forming a stable chelate complex with metal cations (such as Fe

2⁺) on the steel surface [

12]. The efficacy of henna extract has been demonstrated in several studies, mainly in organic polymer matrices. For example, Khoshkhou et al. reported that the incorporation of 3% henna extract into a TMSM-PMMA hybrid coating on low carbon steel reduced the corrosion rate from 1.90 MPY to 0.02 MPY in 0.1 M HCl solution [

13]. Similarly, on aluminum alloys, Wan Nik et al.'s study showed that Lawsone contributed to chemical absorption or adsorption, forming an insulating layer on the aluminum alloy surface, achieving an inhibition efficiency of 88% at a henna concentration of 500 ppm in seawater [

14]. Another study by Zulkifli et al. on the effect of different concentrations of henna leaf extract (HLE) when incorporated into an acrylic coating showed that an acrylic coating with 0.2 wt/vol% HLE (AC2) exhibited the best performance in protecting 5083 aluminum alloy from corrosion [

15].

However, an overview of published works shows that existing studies mainly focus on the application of henna extract in organic polymer matrices (such as PMMA, epoxy, acrylic) or as an inhibitor in aqueous solutions. Its efficacy, compatibility and mechanism when directly incorporated into a reactive inorganic coating matrix, such as potassium silicate, remains an area that has not been fully explored.

To contribute to filling this gap, our study systematically investigates the effect of Lawsonia inermis leaf extract as a functional additive in potassium silicate coatings formulated with a hybrid pigment system consisting of 50 wt% zinc spheres and 5 wt% zinc-aluminum flakes on carbon steel substrates. The effects of extract concentration on the physicochemical properties (FTIR), crystal structure (XRD), surface elemental composition distribution (XRF), microstructural morphology (SEM), adhesion and especially the corrosion protection of the paint films will be comprehensively evaluated by electrochemical techniques such as Open Circuit Potential (OCP), Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) and Dynamic Potential Polarization. The ultimate goal is to elucidate the resonant protection mechanism from the integration of green inhibitors into advanced inorganic composite coating systems, thereby expanding the scope of application in the development of high-performance and durable protective coatings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of Extract

Commercial henna powder (HNCO Organics, India) was dried at 105°C for 60 minutes to completely remove moisture. Then, 50g dry henna powder was dispersed in 500 ml of distilled water, boiled and stirred for 30 minutes. The mixture was cooled and filtered through Whatman filter paper to collect the liquid extract.

The total polyphenol content in the extract was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using an UV-VIS Spectrophotometer SP-UV1100 (China). The total polyphenol content was expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE) and was determined to be 103 mg GAE/g dry extract powder. An aliquot of this liquid extract was concentrated to dryness using a rotary evaporator to obtain a dry henna extract powder, named Dried Aqueous Henna Extract (DAHE). This DAHE powder was used only for FTIR spectra of the pure inhibitor.

2.2. Coating Preparation

CT3 carbon steel substrates (composition: 96.84% Fe; 0.1% C; 0.75% Al; 0.19% Si; 2.11% Cu) were sanded with sandpaper up to P1200, degreased with methanol in an ultrasonic bath, rinsed with ionized water and dried. Then, the steel samples were pretreated with a Zr⁴⁺ conversion coating.

The zinc-rich silicate paint system is a two-component system. Component A is a solid mixture of spherical Zinc particles, with a size of 5–7 μm and a Zn:ZnO ratio of 50.3:49.7, supplied by Jotun Paint Company (Vietnam). Meanwhile, ZnAl flake alloy with the same particle size of 5–7 μm and a Zn:Al ratio of 80:20, was purchased from Hunan Jinhao New Material Technology Co., Ltd. (China). Component B is a liquid solution containing potassium silicate as a film former with nano-silica added to achieve a molar ratio of SiO₂/K₂O = 5/1. In this study, component B was supplemented with the above-prepared henna extract at concentrations of 0, 3, 5, 8, 10, and 12 wt%, corresponding to the samples denoted H0, H3, H5, H8, H10, and H12.

The paint formulations were mechanically stirred for 30 min and applied to steel substrates by spraying to achieve a dry film thickness of 100 ± 10 µm. The samples were allowed to cure naturally for 7 days at room conditions before measurements were taken.

2.3. Characteristic Analysis Methods

To analyze the characteristics of the paint films, a variety of methods were used. The surface morphology was examined using a JMS-6510LV (Jeol, Japan) device after the samples were stabilized at room temperature, cut into 1x1 cm pieces, and coated with a layer of gold powder to support surface conductivity. Chemical analysis was performed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) on a Nicoletis10 spectrometer (Thermo, USA). For this analysis, the henna extract was evaporated to dryness and placed on a sample holder with a diffuse reflectance measurement accessory. The crystal phase structure (XRD) was determined using a D8-ADVANCE device (Bruker-Germany) after the paint samples had dried naturally for 7 days. The measurements were performed using CuKα radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA, recording diffraction patterns in the angle range of 4–80° (2θ) with a step size of 0.02° and a scanning time of 0.4 s/step. The elemental composition was determined by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy using a VietSpace model XRF 5006 - 2020 on 5x5 cm samples at room temperature, with a wavelength range of 0.01 to 10 nm. Finally, the adhesion of the paint film was quantified by the pull-off test according to ASTM D4541.

Electrochemical studies were carried out using an Autolab PGSTAT 302N device with a three-electrode system, consisting of a platinum electrode (auxiliary), an Ag/AgCl electrode (reference), and a sample (working). Potentiodynamic polarization measurements were conducted to investigate the corrosion current density (icorr) and corrosion potential (Ecorr). The potential was scanned at ±150 mV relative to the open circuit potential (OCP) at a scan rate of 0.01 V/s. The corrosion current density was collected by Tafel extrapolation at ±50 mV around the OCP. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed over an area of 3.46 cm2 in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution at a frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz, with an alternating potential amplitude of 10 mV. Each sample was tested at least three times to ensure the repeatability of the measurements, and the obtained data were analyzed using Nova 2.1 software.

3. Results and Discussion

This study focused on evaluating the effectiveness of Lawsonia inermis extract as a green corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel when incorporated into a water-based zinc-rich potassium silicate paint system. The physicochemical properties, surface morphology and corrosion protection of paint films with different concentrations of the extract were systematically investigated. The addition of the extract is expected to improve the corrosion protection of the coating through a dual mechanism of action from the physical barrier of the paint system and the active inhibition of organic compounds contained in the extract. The results obtained will provide a basis for the development of environmentally friendly paint systems.

3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Analysis (FTIR)

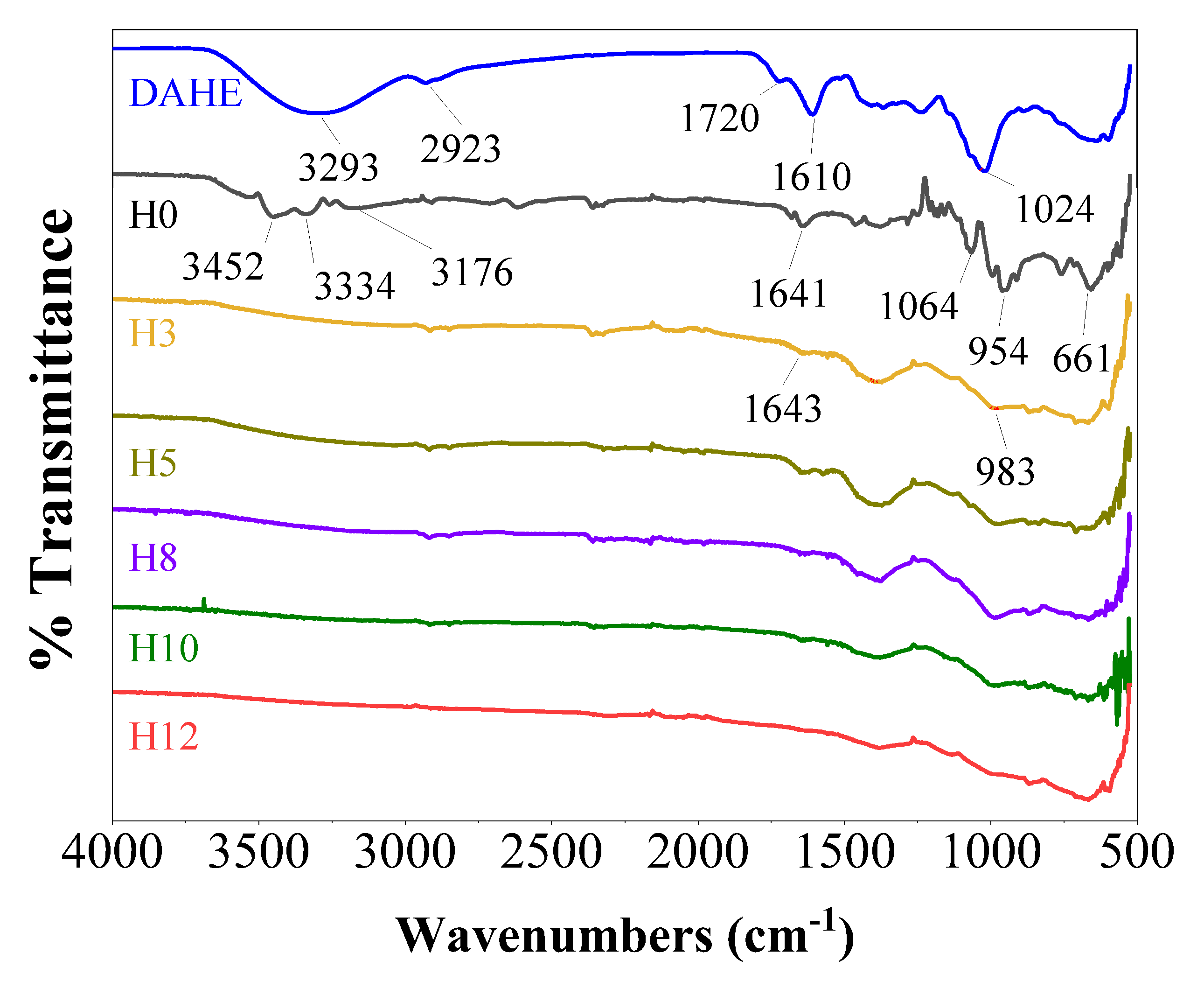

To confirm the presence and interaction of henna extract in the paint film, infrared spectroscopy was performed, with the results presented in

Figure 1. The spectrum of the DAHE powder exhibited characteristic absorption bands of polyphenolic compounds. The broad band at 3293 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the valence vibration of the O-H bond [

16]. The peaks at 1720 cm⁻¹ (C=O) and 1610 cm⁻¹ (C=C aromatic ring) were of the major compounds such as lawsone and flavonoids [

17]. In addition, the peaks at 2923 cm⁻¹ (C-H) and 1024 cm⁻¹ (C-O) also confirmed the complex organic nature of the extract [

18].

For the control paint film (H0), the spectrum shows the characteristics of a water-based potassium silicate paint system. The broad band in the region of 3452–3176 cm⁻¹ and the peak at 1641 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the vibrations of the O-H group (from the silanol group and adsorbed water) and water molecules. The strongest and most characteristic absorption band in the region of 1064–954 cm⁻¹ is identified as that of the asymmetric stretching vibration of the Si-O-Si bond, which is the “backbone” of the inorganic silicate network [

19]. Another absorption peak at around 661 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the deformation vibration of the O-Si-O bond [

20].

To confirm the presence and interaction of henna extract in the paint film, infrared spectroscopy was performed, with the results presented in

Figure 1. The spectrum of DAHE powder showed characteristic absorption bands of polyphenolic compounds. The broad band at 3293 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the valence vibration of the O-H bond [

16]. The peaks at 1720 cm⁻¹ (C=O) and 1610 cm⁻¹ (C=C aromatic ring) were of the major compounds such as lawsone and flavonoids [

17]. In addition, the peaks at 2923 cm⁻¹ (C-H) and 1024 cm⁻¹ (C-O) also confirmed the complex organic nature of the extract [

18].

For the control paint film (H0), the spectrum shows the characteristics of a water-based potassium silicate paint system. The broad band in the region of 3452–3176 cm⁻¹ and the peak at 1641 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the vibrations of the O-H group (from the silanol group and adsorbed water) and water molecules. The strongest and most characteristic absorption band in the region of 1064–954 cm⁻¹ is identified as that of the asymmetric stretching vibration of the Si-O-Si bond, which is the “backbone” of the inorganic silicate network [

19]. Another absorption peak at around 661 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the deformation vibration of the O-Si-O bond [

20].

Distinct changes were observed when comparing the spectra of the paint films containing the extract with the control sample H0. The entire spectrum of H3, H5, H8, H10, H12 becomes flatter and broader, which is a strong evidence for the formation of a dense and complex hydrogen bond network between the polyphenol molecules and the silicate network [

21]. This interaction is further confirmed by the shift of the main Si-O-Si band. In the coating samples containing henna extract, the center of this band has shifted to a lower wavenumber, centered around 983 cm⁻¹. This peak shift demonstrates that the chemical environment of the Si-O-Si bond has changed due to the interaction with the hydroxyl groups of the inhibitor. The presence of the peak at 1643 cm⁻¹ further confirms that the organic compounds from the extract have been successfully incorporated into the structure of the paint film.

3.2. Crystal Structure Analysis by X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted to determine the crystalline phases present in the paint film and evaluate the effect of extract addition on the structure of the pigment particles.

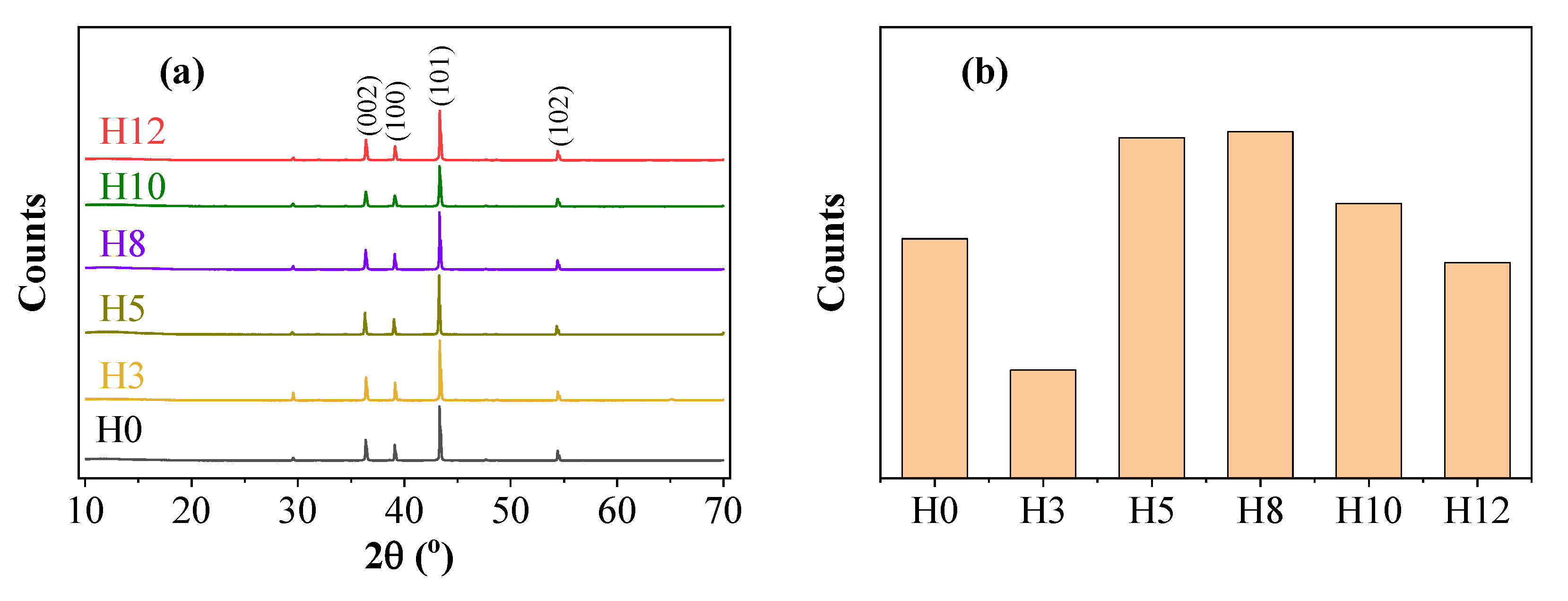

Figure 2 shows the XRD patterns of samples H0, H3, H5, H8, H10, H12 and the change in intensity of the main diffraction peak.

The XRD patterns of the paint films (

Figure 2a) show similarities in the positions of the diffraction peaks. The main peaks at 2θ = 36.2°, 38.9°, 43.2°, 54.3°, and 70.6° correspond to the (002), (100), (101), (102), and (110) crystal planes of metallic zinc (Zn) with a hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure [

22]. The peak at 43.2° is the most intense characteristic peak of zinc. The absence of new crystalline phases or peak shifts in samples H3, H5, H8, H10, and H12 compared to H0 confirms that the addition of henna extract did not alter the crystalline structure of the zinc pigment but may have affected factors such as particle orientation.

However, the variation in intensity of the main diffraction peak (101) shows a more complex trend, as illustrated in

Figure 2b. Observation of the bar graph shows that the intensity of the (101) peak varies non-monotonically with the concentration of the extract. Specifically, compared with the control sample H0, the diffraction intensity decreases in samples H3, H10, and H12, but increases in samples H5 and H8, with sample H5 showing the highest peak intensity among all samples.

The increase in diffraction intensity in sample H5 is an important finding, and can be explained through the role of the extract as a dispersant, a mechanism that will be confirmed by the XRF analysis results in the following section. Specifically, at the optimal concentration (5 wt%), the polyphenolic compounds in the extract were effectively adsorbed onto the surface of the pigment particles, preventing agglomeration and promoting uniform dispersion in the liquid paint matrix. A better dispersed pigment system would facilitate a more orderly arrangement of the particles during solvent evaporation and paint film curing, leading to a preferential orientation of the (101) crystal planes and thus an increase in the intensity of the corresponding diffraction peak [

23]. This mechanism supports the hypothesis that the extract not only acts as an inhibitor at the steel surface but also acts as an effective microstructural modifier.

In contrast, the intensity decrease at low (H3) and high (H10, H12) concentrations could be explained by other mechanisms. At low concentrations, the amount of inhibitor may not be sufficient to produce an orientation effect. At high concentrations, the excess of organic molecules may lead to a more random packing of the zinc particles, reducing the orientation and simultaneously enhancing the attenuation of the X-ray signal. This result suggests that the extract concentration has a subtle influence on the microstructure of the paint layer, and a concentration of around 5 wt% seems to produce a more optimal arrangement of the zinc pigment particles.

3.3. Surface Elemental Composition Analysis by X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

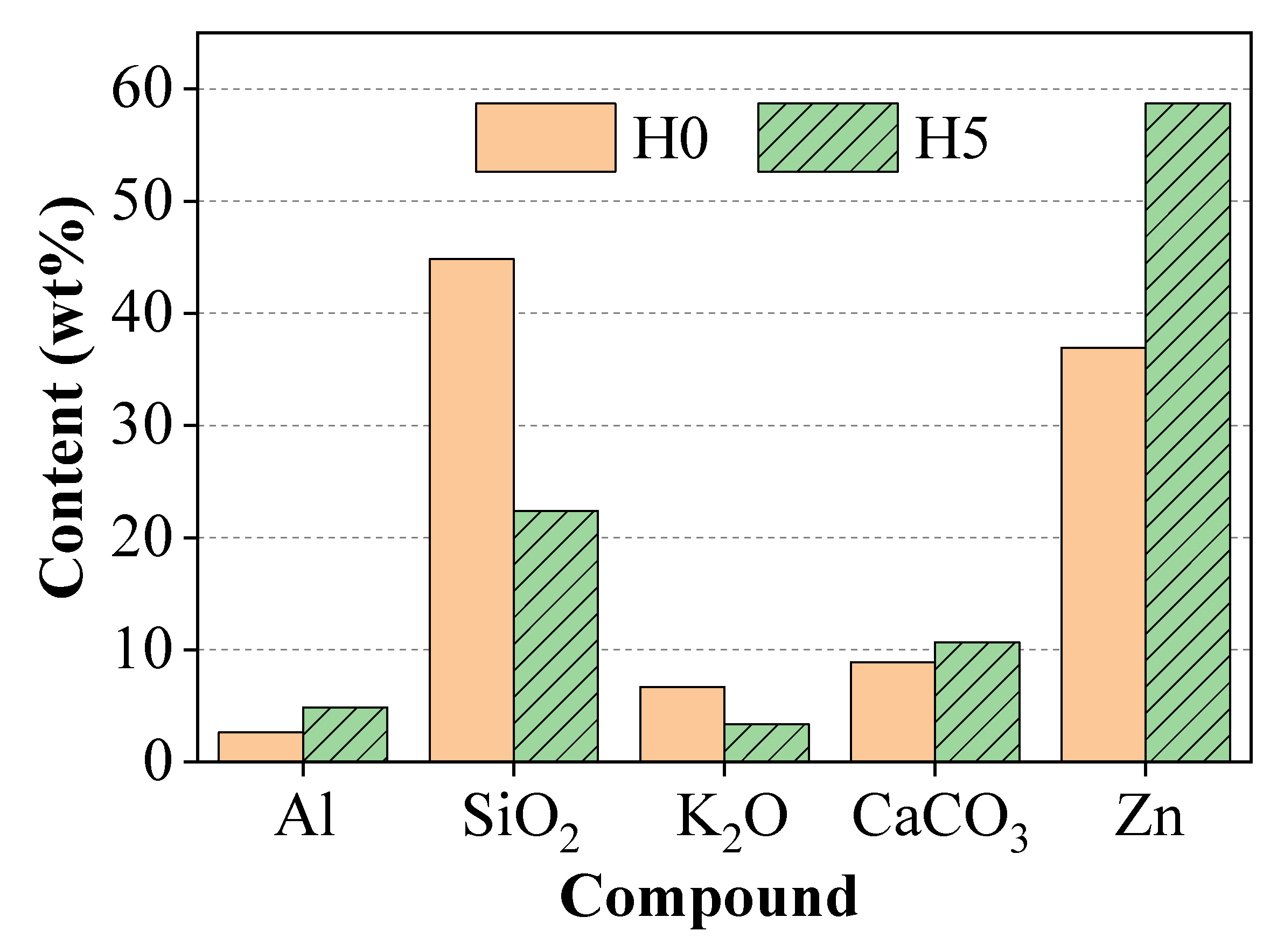

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis was performed to determine and compare the elemental composition of the surface of the control paint film (H0) and the paint film containing the inhibitor (H5). The quantitative results (presented in

Figure 3) showed a notable change in the surface composition in the presence of henna extract. Specifically, compared to sample H0, the surface of sample H5 showed a clear increase in Zinc (Zn) and Aluminum (Al) content, while a significant decrease in Silicon (Si) content was recorded.

Since the initial mix composition of the paint remained constant, this difference does not reflect a change in the overall composition of the coating, but suggests a microstructural restructuring during curing. XRF is a surface-sensitive technique, therefore, this result suggests that the henna extract may have acted as an effective dispersant for the pigment particles. The polyphenolic compounds in the extract were able to adsorb onto the surface of the Zn and ZnAl pigment particles, reducing the interaction between the particles and preventing agglomeration. This improved dispersion may have allowed the heavier metal pigment particles to be distributed uniformly and dominate the outermost surface layer, while the lighter components of the binder and filler (containing Si) were pushed to the inner layer [

23].

This finding provides an important explanation for the structural and morphological analysis results. A better-dispersed pigment system is a prerequisite for a more compact and homogeneous paint film structure; this is expected to be evident in the surface morphology analysis in the next section. Furthermore, the ordered arrangement of the particles is consistent with the XRD results, which show an increase in diffraction intensity in sample H5, suggesting a preferential orientation of the zinc particles.

3.4. Surface Morphology Analysis (SEM)

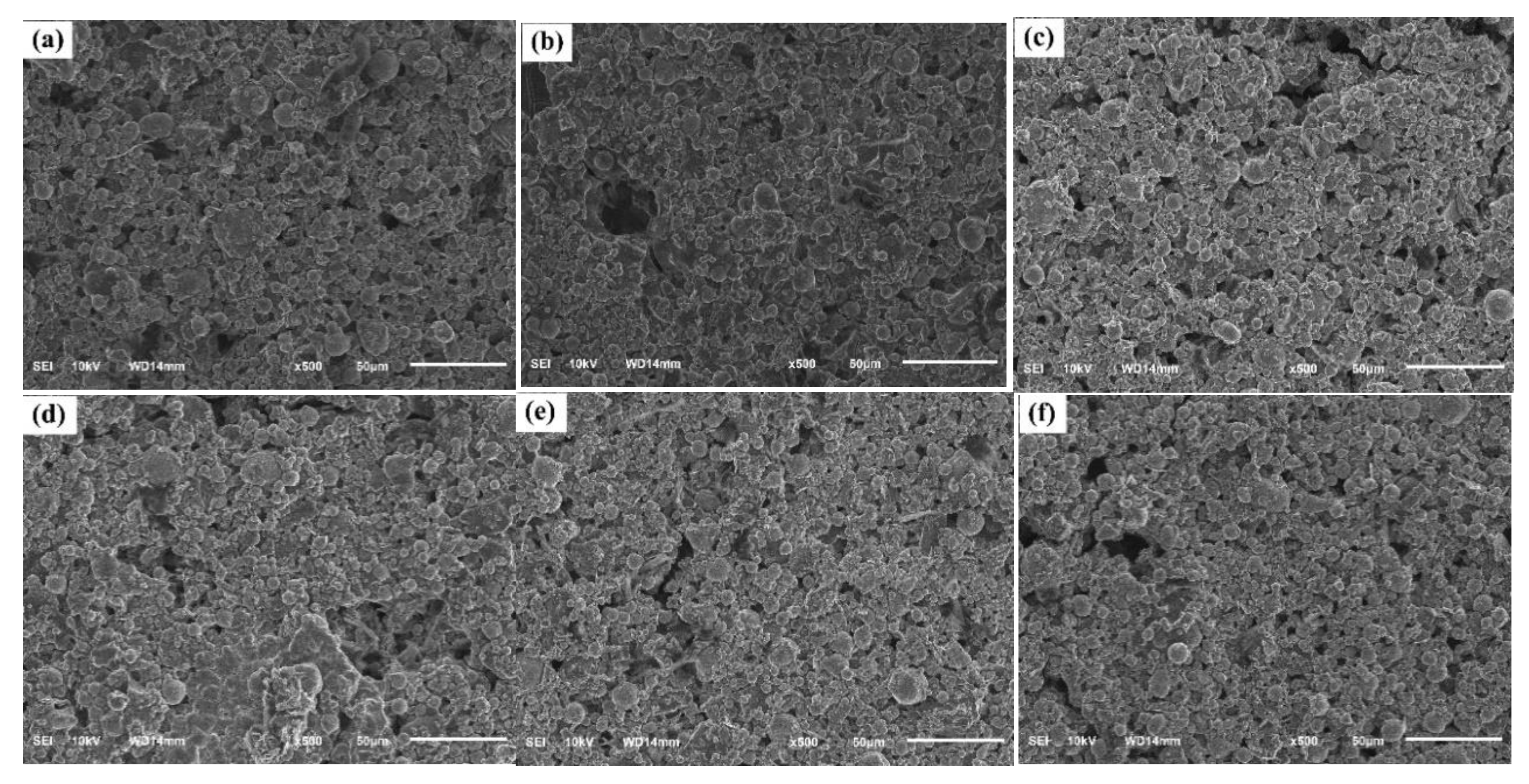

The surface morphology of the paint films, an important factor affecting the protective ability of the coating, was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The SEM images of samples are shown in

Figure 4.

All the paint films showed a rough surface structure, consisting of spherical zinc particles and flake-like pigments distributed within a silicate binder. The control H0 paint film showed a relatively porous structure with the presence of small voids and pores between the pigment particles. This microporous structure is characteristic of zinc-rich paints, which is necessary to maintain electrical contact between the zinc particles to ensure an effective cathodic protection mechanism [

24]. However, high porosity can also facilitate the penetration of corrosive agents such as water and chloride ions into the coating.

With the addition of the extract, the surface morphology of the paint films changed notably with concentration. At low and medium concentrations of 3 wt% and 5 wt% (samples H3, H5), the surface became significantly more compact and homogeneous than that of sample H0. In particular, sample H5, the pigment particles were more closely packed, significantly reducing the size and number of pores on the surface. This improved morphology is a direct result of the extract's role as an effective dispersant, as demonstrated by previous XRF analysis. Such a compact film structure would create a more effective physical barrier, slowing the penetration of electrolytes and thus improving corrosion resistance. [

25]. However, when the extract content was further increased to 8 wt%, 10 wt% and 12 wt% (samples H8, H10 and H12), the paint film surface tended to become less uniform and more defective than sample H5. Specifically in sample H12, the appearance of some pigment agglomerates and the structure became more porous. The excess of organic compounds may have hindered the formation of silicate network bonds, or caused the agglomeration of pigment particles, resulting in a more defective structure. [

26]. Such a suboptimal structure may reduce both the barrier efficiency and the cathodic protection of the coating.

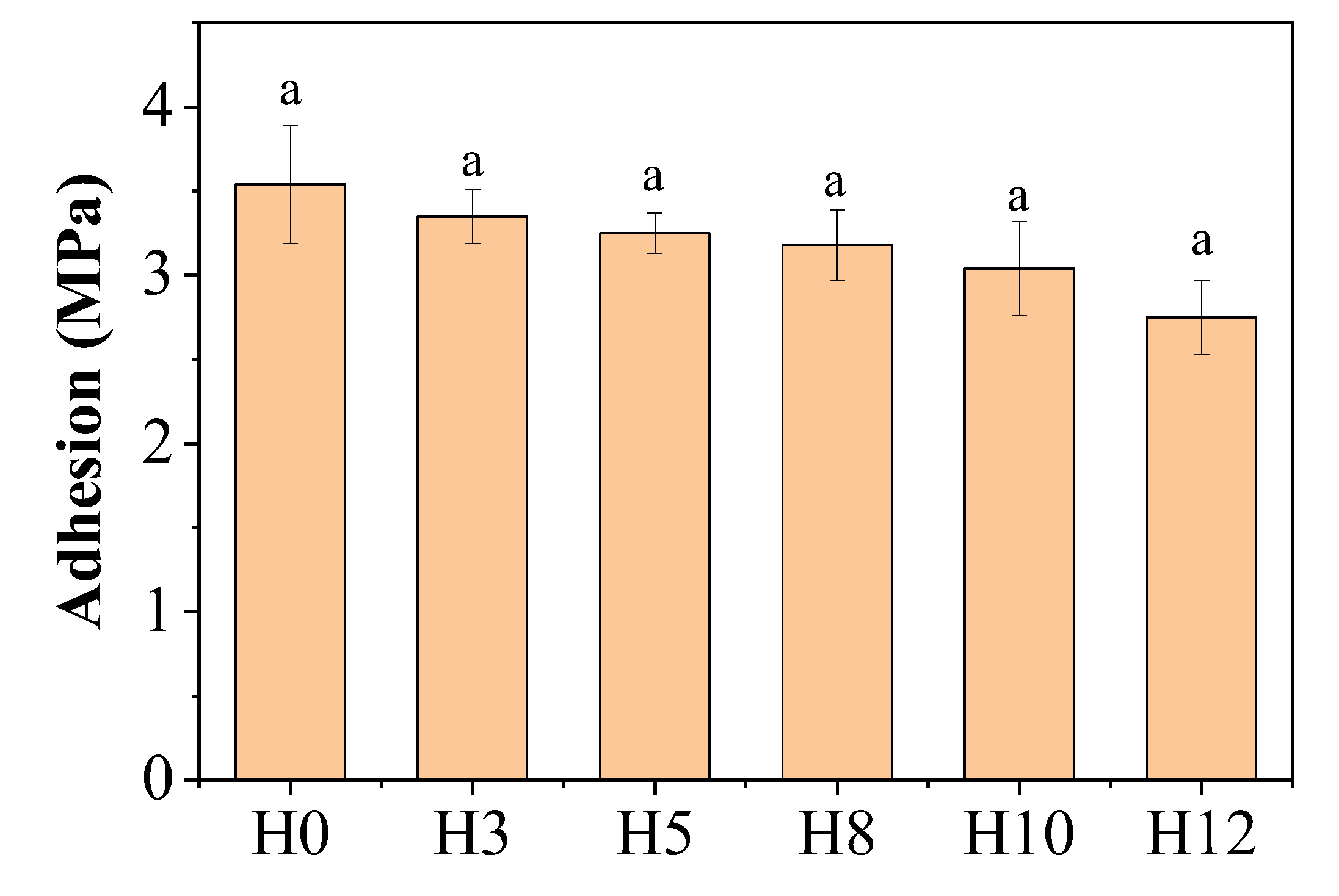

3.5. Adhesion Analysis (Pull-Off Test)

Figure 5 shows the results of adhesion measurements of paint films on carbon steel substrates using the pull-off method (ASTM D4541). The results show that the adhesion of the control paint film H0 (without extract) reached the highest value, 3.54 MPa. When henna extract was added, the adhesion tended to decrease gradually with the increase in the concentration of the extract. Sample H12, with the highest extract content (12 wt%), exhibited the lowest adhesion, 2.75 MPa. Despite the decreasing trend, it should be noted that the statistical difference between samples may not be significant, as by the symbol "a" on the data columns.

This adhesion loss can be explained by several mechanisms. First, the organic compounds present in the extract, mainly polyphenols, may interfere with the formation of the Si-O-Si cross-linked network of the potassium silicate binder. The presence of these molecules may disrupt the continuity of the inorganic structure, leading to a decrease in the cohesive strength within the paint film, which is an important factor in determining the measured adhesion [

27]. In fact, the adsorption mechanism of organic molecules onto the surface of the pigment particles—which improves dispersion as demonstrated by XRF—may also be responsible for this decrease. When organic molecules coat the pigment particles, they may reduce the direct interaction between the pigment and the silicate binder, thereby weakening the bonds within the paint film.

Second, at high concentrations, organic molecules are able to migrate and concentrate at the interface between the paint and the metal substrate. This accumulation can form a weak boundary layer, reducing the direct interaction and chemical bonding between the silicate binder and the steel surface, thereby reducing the adhesion strength [

28]. Furthermore, the adsorption of organic compounds onto the surface of zinc pigment particles can also affect their wetting and bonding with the binder, contributing to a reduction in the overall mechanical integrity of the entire coating.

This result suggests that an optimal inhibitor concentration is necessary, as increasing the concentration to improve corrosion resistance may lead to a deterioration of key mechanical properties, such as adhesion.

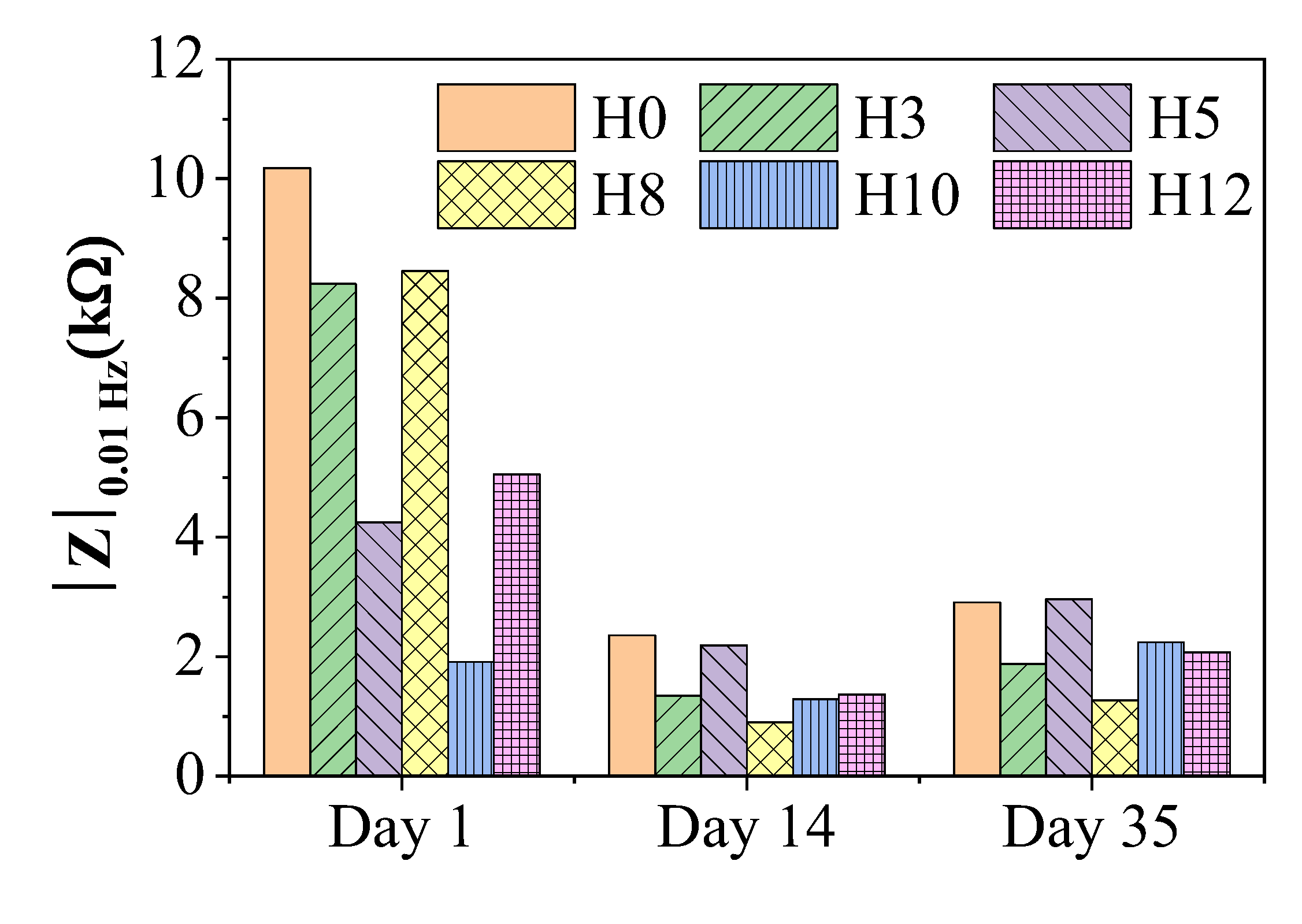

3.6. Electrochemical Impedance Spectrum Analysis (EIS)

To evaluate the corrosion protection of the coatings over time, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed after immersion cycles of the samples in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution.

Figure 6 shows the variation of the impedance modulus at low frequency (|Z|₀.₀₁ Hz) – an important parameter reflecting the total impedance of the system and commonly used to evaluate the corrosion protection performance of the coating [

29]. A higher value of |Z|₀.₀₁ Hz indicates a better protection of the coating.

The graph shows that all paint samples had a significant decrease in impedance value after the first 14 days of immersion, and then tended to stabilize until day 35. This initial decrease is a common phenomenon, reflecting the process of electrolyte solution penetrating through the pores and micro-defects of the paint film to reach the base metal surface [

30].

When comparing the performance between samples, on the first day, the control H0 paint film showed the highest impedance value. However, over time, the protective performance of H0 rapidly decreased. By day 35, the H5 paint film (containing 5 wt% extract) showed the highest |Z|₀.₀₁ Hz value among all the samples, surpassing the control H0. This superior performance can be attributed to the synergistic effect of two mechanisms. The first mechanism is the enhancement of the barrier properties of the paint film. As demonstrated by XRD and SEM analyses, the 5 wt% extract concentration seemed to act as an effective dispersant, resulting in a dense, homogeneous, and less porous paint film microstructure [

25]. This improved barrier significantly slowed down the penetration of corrosive agents. The second mechanism (Active Corrosion Inhibition) is activated when the electrolyte solution has penetrated the steel surface. Here, the organic molecules in the henna extract move along the solution and adsorb onto the metal surface, forming a protective molecular film. This film directly hinders the electrochemical reactions of the corrosion process, thereby maintaining high impedance for the system for a long time [

28,

31].

Samples containing different concentrations of extract (H3, H8, H10, H12) all showed lower impedance values than sample H5 and the control sample H0 at day 35. This result indicates the existence of an optimal inhibitor concentration. At concentrations lower than 5 wt%, the amount of inhibitor may not be sufficient to form a complete coating on the metal surface. Conversely, at higher concentrations, the excess of organic compounds may impair the structural integrity of the paint film (as suggested by SEM and adhesion analysis), creating more pathways for electrolyte penetration and reducing the overall protective effect.

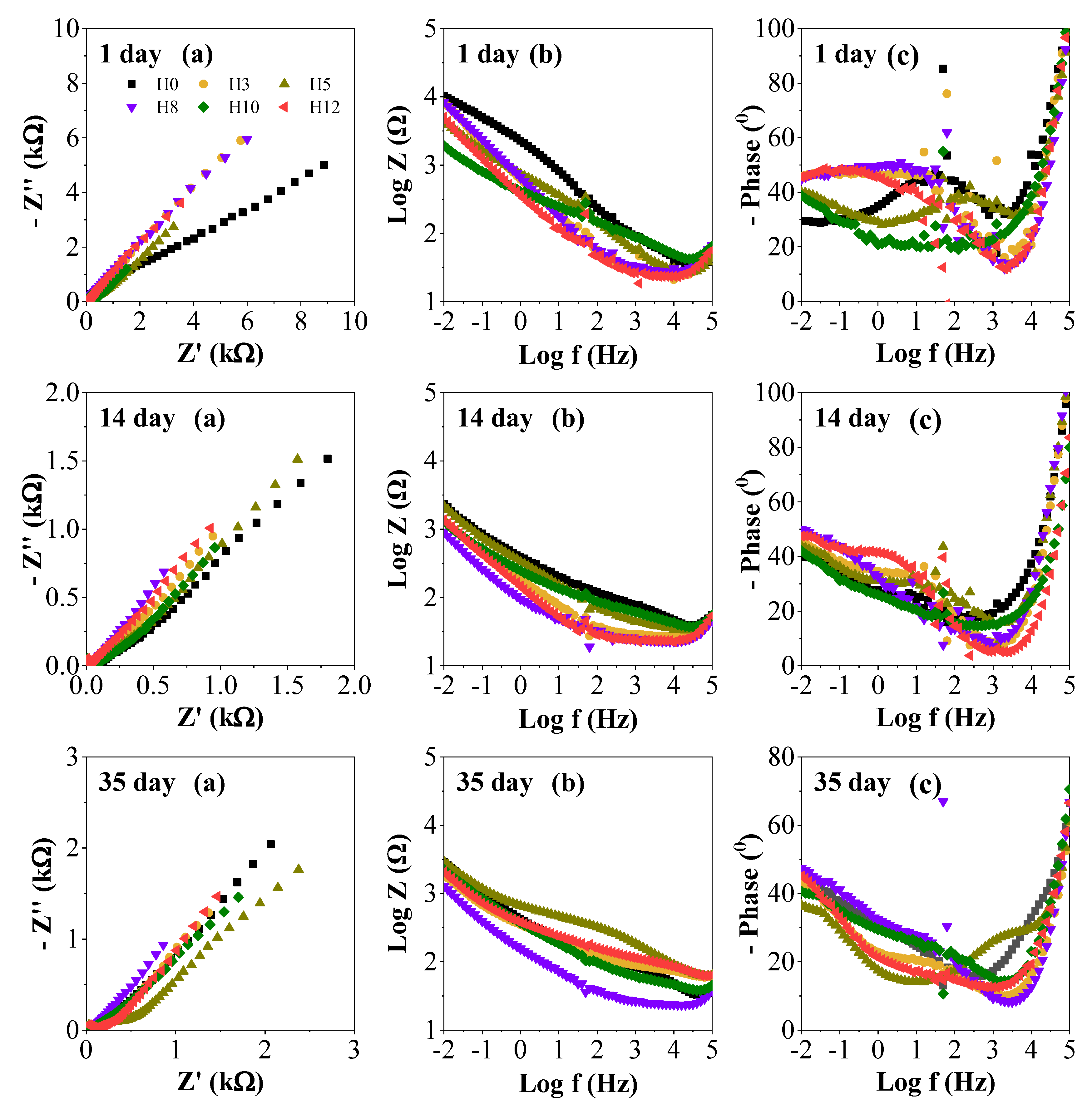

3.7. Detailed EIS Analysis

Figure 7 presents detailed electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data in the form of Nyquist (a), Bode (b) and phase angle (c) of samples at 1, 14 and 35 days of immersion. These plots provide a deeper insight into the mechanism and kinetics of the corrosion process, complementing the summary data in

Figure 6.

Overall, over the immersion time from 1 to 35 days, all samples show a clear change in impedance spectra. In the Nyquist plot (a), the diameter of the semicircles is significantly narrowed, indicating a decrease in charge transfer resistance (Rct), a parameter inversely proportional to the corrosion rate [

32]. Similarly, in the Bode plot (b), the impedance value at low frequencies decreases, and in the phase angle plot (c), a second time constant begins to appear in the low frequency region. These changes are characteristic signs of coating degradation, as the electrolyte solution has penetrated the paint film and corrosion processes begin to take place at the metal/paint interface [

32].

At 35 days, the difference in the protective performance of the coatings is most apparent. Looking at all the samples, sample H5 shows a semicircular arc on the Nyquist plot with the largest diameter, while sample H12 has the smallest diameter and sample H0 has an intermediate size. Samples H3, H8 and H10 show semicircular arcs with smaller diameters than H5, consistent with the protective effect trend noted in the composite plot.. This indicates that the H5 coating retains its capacitive (i.e. barrier) properties better after a long period of exposure to the corrosive environment.

In contrast, sample H12 exhibited the smallest semicircular diameter and the lowest impedance value, indicating a high corrosion rate. This reaffirms that the 12 wt% extract concentration was too high, which may have damaged the paint film structure and reduced the protective ability. The control sample H0 has a performance between H5 and H12, which indicates that while it had good initial barrier properties, it lacked an active protection mechanism to resist long-term corrosion once the electrolyte had penetrated. Therefore, these detailed EIS data further reinforce the conclusion that the 5 wt% concentration of henna extract (sample H5) provides the optimal combination of barrier protection and active inhibition mechanisms, resulting in the most superior anti-corrosion efficacy.

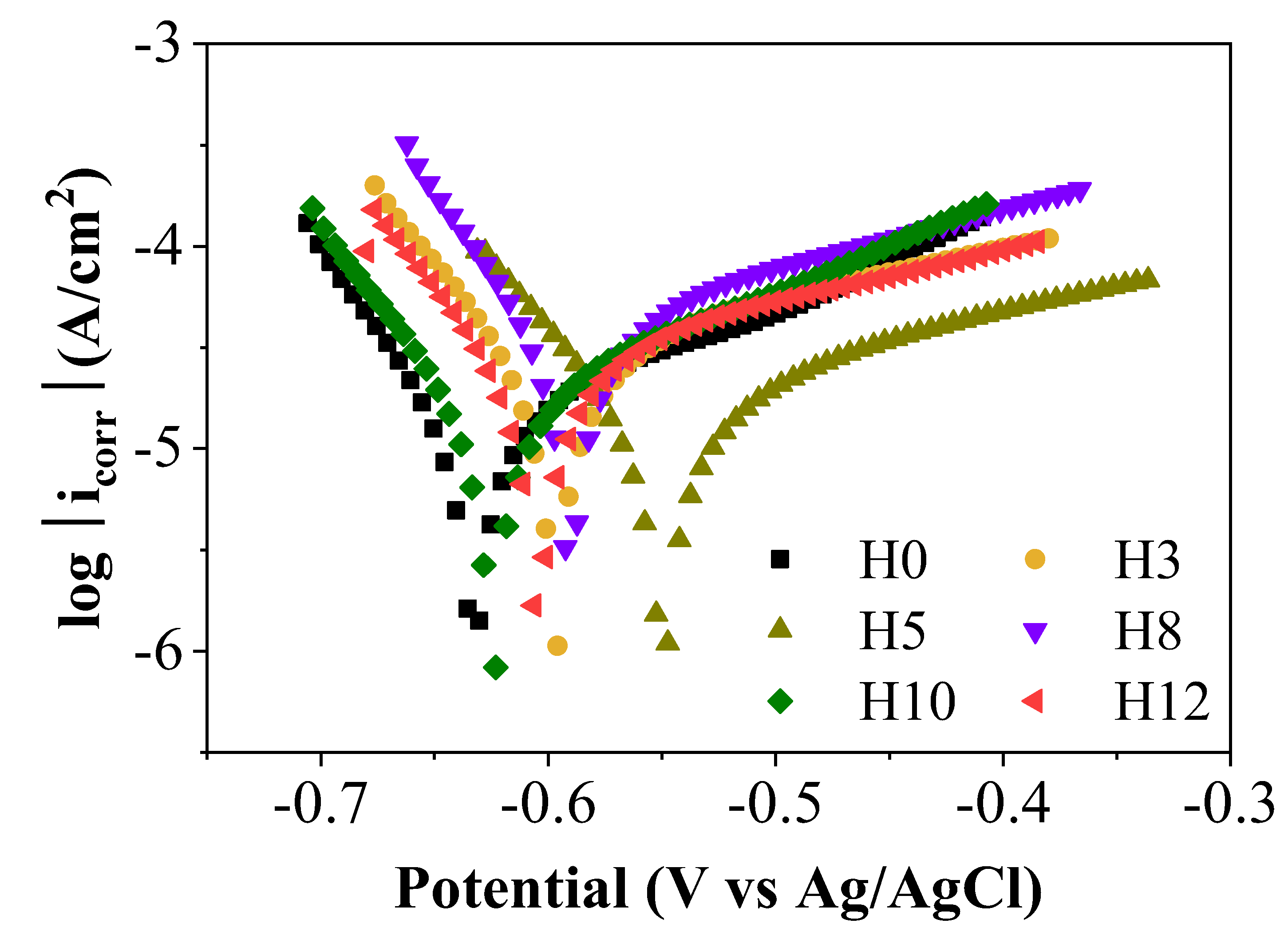

3.8. Polarization Curve Analysis (Potentiodynamic Polarization)

To further confirm the effectiveness and clarify the corrosion inhibition mechanism, potentiodynamic polarization measurements were performed after 35 days of sample immersion.

Figure 8 and

Table 1 present the polarization curves and the electrochemical parameters extracted from them, providing detailed information on the kinetics of the electrochemical reactions on the surface.

From

Table 1, it can be seen that the corrosion potentials (E

corr) of the samples containing the extract (H3-H12) are all shifted towards the positive side compared to the control sample H0 (-0.633 V). Notably, sample H5 has the most positive E

corr value (-0.55 V). The shift of Ecorr towards the more positive side is an indication that the inhibitor tends to act on the anode regions, slowing down the dissolution of the metal [

33]. However, observation of the polarization curves of all samples showed that both the anodic and cathodic branches were shifted in the presence of the inhibitor compared to the control sample H0. This combined with the changes in the positive (βa) and negative (βc) Tafel slope values (Table 2), confirms that the henna extract acts as a mixed-type inhibitor, capable of simultaneously inhibiting both the metal dissolution reaction at the anode and the oxygen reduction reaction at the cathode [

34]. Other studies have also shown the mixed inhibition mechanism of henna extract on carbon steel [

13,

35].

An important point to consider is the corrosion current density (i

corr) value, a parameter that is directly proportional to the corrosion rate. The data in

Figure 8 and

Table 1 show that sample H5 (5.385 µA/cm

2) has a slightly higher icorr value than sample H0 (4.507 µA/cm

2), while the other samples have significantly higher icorr. This result appears to be inconsistent with data from the EIS, where H5 showed superior protection compared to H0. This difference can be explained by considering the specific protection mechanism of zinc-rich paints. In this system, the measured icorr reflects not only the corrosion of the steel substrate but also includes the current generated by the sacrificial dissolution of zinc particles, which is the main protection mechanism (cathodic protection). Therefore, a low icorr value such as that of sample H0 may simply indicate that the system is in a relatively passive state. Conversely, a slightly higher icorr value of sample H5 may be an indication of an effective cathodic protection system, in which zinc particles are actively dissolving to protect the steel [

36]. In this context, polarization resistance (Rp), a parameter inversely proportional to the corrosion rate at the interface, becomes a more reliable indicator to assess the actual protection of the base steel [

37]. The data in

Table 1 show that sample H5 possesses the highest Rp value (1939.4 Ω), outperforming sample H0 (1694.5 Ω) and the remaining samples. This result is consistent with the impedance data from EIS measurements, confirming that the paint film containing 5 wt% extract provides the most effective corrosion protection for steel. The superior protection effect at a certain optimum concentration has also been observed in other paint systems containing henna extract, where either too high or too low concentrations reduced the performance [

12,

31].

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of Lawsonia inermis extract as a functional additive in zinc potassium silicate-rich paint systems, with the optimum concentration determined to be 5 wt%. At this concentration, the extract exhibited a dual role: it acted not only as a mixed-type corrosion inhibitor, but also as an effective microstructural modifier. XRF, XRD and SEM analyses showed that the extract improved the dispersion of the pigment, resulting in a denser, more ordered and zinc-rich paint film on the surface.

Consequently, the H5 paint film exhibited superior corrosion protection after 35 days of immersion in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, a finding confirmed by both EIS and potentiodynamic polarization measurements. Despite a slight decrease in adhesion, the overall results confirmed the potential of henna extract as an effective green inhibitor that simultaneously enhances both barrier protection and active inhibition mechanisms for industrial coating systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Le Thi Nhung; Methodology: Le Thi Nhung, Nguyen Hoang; Formal analysis and investigation: Truong Anh Khoa, Phan Minh Phuong; Writing - original draft preparation: Le Thi Nhung, Nguyen Hoang; Writing - review and editing: Le Thi Nhung, Nguyen Hoang.

Funding

This research was funded by Institute of Oceanography, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Grant Number CSCL18.02/24-25.

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Lobo, R.E. , Guzmán, B., Orrillo, P.A., Domínguez, C.C., Jimenez, L.E., Torino, M.I. Corrosion: basics, adverse effects and its mitigation. In Sustainable Food Waste Management: Anti-corrosion Applications, Springer, 2024; pp. 3–22.

- Joshi, S.S. , Patil, V.J., Gite, V.V. High performance coating formulation using multifunctional monomers and reinforcing functional fillers for protecting metal substrate. Pigm. Resin. Technol. 2025, 54, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L. Inorganic zinc coatings--Well known, yet commonly forgotten facts. Mater. Perform. 2000, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.X. , Li, B.J., Peng, Y.L., Yue, W.T. Influence of zinc content on anti-corrosion performance of zinc-rich coatings. AMM 2013, 423, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. , Li, J., Guo, Y., Wang, J., Yang, Z., Liang, M.J.J.o.A. The formation mechanism of the composited ceramic coating with thermal protection feature on an Al12Si piston alloy via a modified PEO process. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 682, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahayata, B. , Mahanta, S.K., Upadhyay, P., Mendon, R.R., Basu, A., Das, S., Mallik, A. An approach to improve corrosion resistance in electro-galvanized Zn-Al composite coating by induced passivity. Mater. Lett. 2023, 351, 135013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubielewicz, M. , Langer, E., Krolikowska, A., Komorowski, L., Wanner, M., Krawczyk, K., Aktas, L., Hilt, M. Concepts of steel protection by coatings with a reduced content of zinc pigments. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 161, 106471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, L.K.M. Mazumder, M.A. Green corrosion inhibitors. In Corrosion inhibitors, IntechOpen, 2019; pp.

- Sharma, S. , Solanki, A.S., Thakur, A., Sharma, A., Kumar, A., Sharma, S.K. Phytochemicals as eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in sulfuric acid solutions: A review. Corros. Rev. 2024, 42, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N. , Karthiga, N., Keerthana, R., Umasankareswari, T., Krishnaveni, A., Singh, G., Rajendran, S. Extracts of leaves as corrosion inhibitors-An overview and corrosion inhibition by an aqueous extract of henna leaves (Lawsonia inermis). Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 2020, 9, 1169–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Batool, A. , Ashiq, K., Khalid, M., Munir, A., Akbar, J., Ahmed, A. An up-to-date review on the phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of the Lawsonia inermis. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, H. , Zulkifli, F., Suriani, M., Sabri, M.M., Nik, W.W. Lawsonialnermis extract enhances performance of corrosion protection of coated mild steel in seawater. in MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences.

- Khoshkhou, Z. , Torkghashghaei, M., Baboukani, A.R. Corrosion inhibition of henna extract on carbon steel with hybrid coating TMSM-PMMA in HCL solution. OJSTA 2018, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik, W.W. , Zulkifli, F., Sulaiman, O., Samo, K., Rosliza, R. Study of henna (Lawsonia inermis) as natural corrosion inhibitor for aluminum alloy in seawater. in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing.

- Zulkifli, F. , Ali, N.a., Yusof, M.S.M., Isa, M., Yabuki, A., Nik, W.W. Henna leaves extract as a corrosion inhibitor in acrylic resin coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 105, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H. Iwata, S. Theoretical studies of geometric structures of phenol-water clusters and their infrared absorption spectra in the O–H stretching region. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P. , Mukhopadhyay, D.P., Chakraborty, T. On the origin of donor O–H bond weakening in phenol-water complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, A. El-Gendy, N.S. Thermodynamic, adsorption and electrochemical studies for corrosion inhibition of carbon steel by henna extract in acid medium. Egypt. J. Pet. 2013, 22, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroya, M. Infrared spectra of SiO2 coating films prepared from various aged silica hydrosols. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1991, 64, 1019–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R. Some applications of infrared spectroscopy in the examination of painting materials. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 1979, 19, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapolova, E. , Korolev, K., Lomovsky, O. Mechanochemical interaction of silicon dioxide with chelating polyphenol compounds and preparation of the soluble forms of silicon. Chem. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 575–580. [Google Scholar]

- Devan, R.S. , Lin, J.-H., Huang, Y.-J., Yang, C.-C., Wu, S.Y., Liou, Y., Ma, Y.-R. Two-dimensional single-crystalline Zn hexagonal nanoplates: Size-controllable synthesis and X-ray diffraction study. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 4339–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J. , Lin, Z., Ju, Y., Rahim, M.A., Richardson, J.J., Caruso, F. Polyphenol-mediated assembly for particle engineering. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo, M. , Svoboda, M., Feliu Jr, S., Kanápek, B., Simancas, J., Kubátova, H.J.P. A new pigment to be used in combination with zinc dust in zinc-rich anti-corrosive paints. Pigm. Resin. Technol. 1998, 27, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawiah, B. , Asinyo, B.K., Frimpong, C., Howard, E.K., Seidu, R.K. An overview of the science and art of encapsulated pigments: preparation, performance and application. Color. Technol. 2022, 138, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becit, B. , Duchstein, P., Zahn, D. Molecular mechanisms of mesoporous silica formation from colloid solution: Ripening-reactions arrest hollow network structures. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0212731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballweg, T. Nique, S., Dialkoxy-or dihydroxyphenyl radicals containing silanes, adhesives produced therefrom and method for producing silanes and adhesives. 2011, Google Patents.

- Marcoen, K. , Gauvin, M.l., De Strycker, J., Terryn, H., Hauffman, T. Molecular Characterization of Multiple Bonding Interactions at the Steel Oxide–Aminopropyl triethoxysilane Interface by ToF-SIMS. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q. , Ma, X., Cai, Y., Wang, Y. Corrosion life prediction of organic coating by gray model based on low-frequency imdepance modulus. in IET Conference Proceedings CP819. IET.

- Amor, Y.B. , Sutter, E., Takenouti, H., Orazem, M.E., Tribollet, B. Interpretation of electrochemical impedance for corrosion of a coated silver film in terms of a pore-in-pore model. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, C573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A. , Hegazi, M., El-Azaly, A. Henna extract as green corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2019, 14, 4668–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croll, S. , Croes, K., Keil, B. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy: characterizing the performance of corrosion protective pipeline coatings. in Pipelines 2015.

- Koumya, Y. , Idouhli, R., Oukhrib, A., Khadiri, M., Abouelfida, A., Benyaich, A. Synthesis, electrochemical, thermodynamic, and quantum chemical investigations of amino cadalene as a corrosion inhibitor for stainless steel type 321 in sulfuric acid 1M. Int. J. Electrochem. 2020, 2020, 5620530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, H. Vashi, R. The study of henna leaves extract as green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acetic acid. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2016, 8, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbout, J. , Touzani, R., Bouklah, M., Hammouti, B. An insight on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel in aggressive medium by henna extract. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 2021, 10, 1042–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Wint, N. , Wijesinghe, S., Yan, W., Ong, W., Wu, L., Williams, G., McMurray, H. The Sacrificial Protection of Steel by Zinc-Containing Sol-Gel Coatings. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, C434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofian, A.H. Noda, K. Corrosion resistance and mechanism of zinc rich paint in corrosive media. ECS Trans. 2014, 58, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).