Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and Mineralogical Characterization

2.2. Leaching Tests

3. Results and Discussion

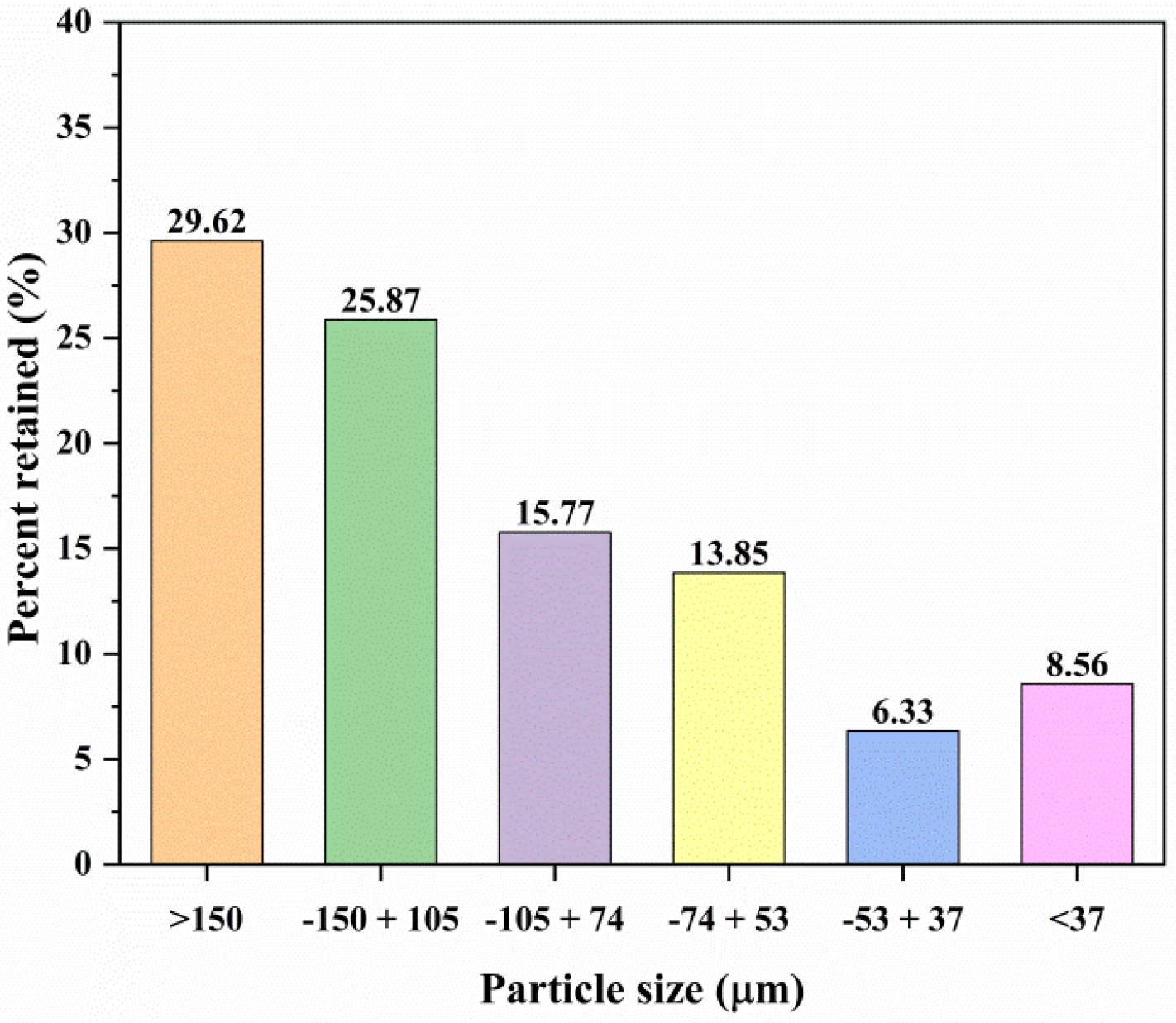

3.1. Granulometric Analysis and Metal Content

3.2. Neutralization Potential (NP) and Acid Potential (AP)

| Iron content% | |||

| Aqua regia | HCL | Pyritic iron | Pyrite content (%) |

| 4.3 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 8.1 |

| HNO3 | HCL | Pyritic iron | Pyrite content (%) |

| 3.9 | 0.6 | 3.3 | 7.1 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| NP (g CaCO3 /kg) | 116.5 |

| AP (g CaCO3 /kg)* | 140 |

| Relación NP/AP | 0.83 |

| *Estimation considering 8.1% FeS2 obtained by chemical method. | |

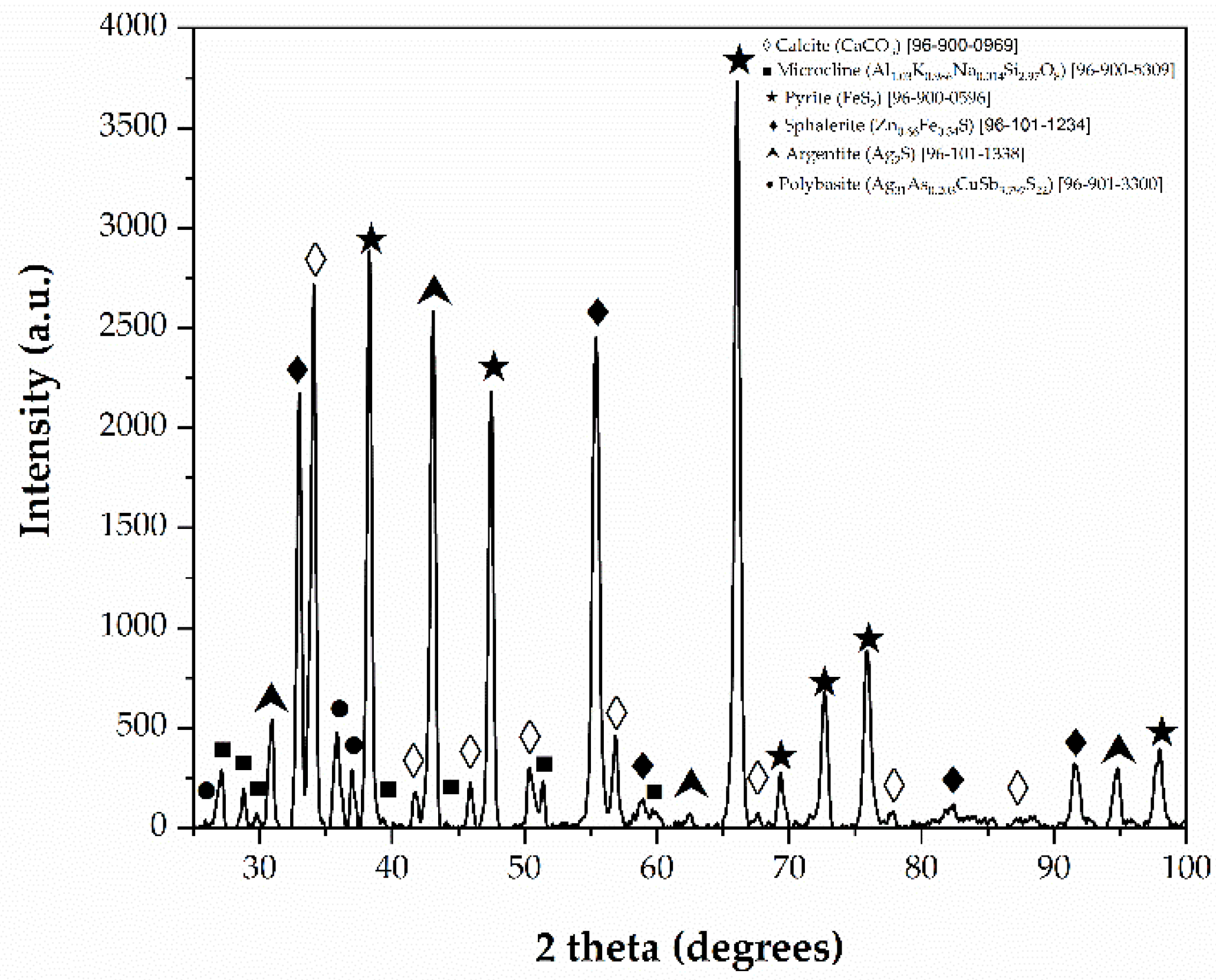

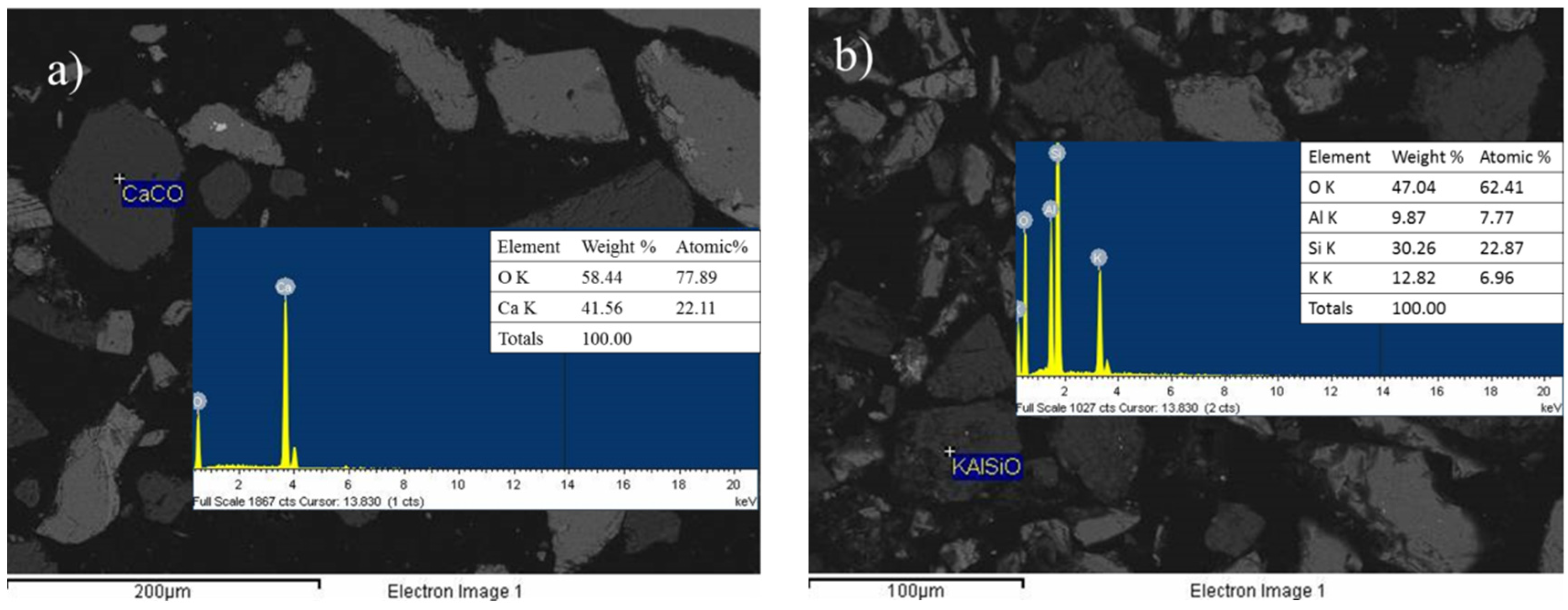

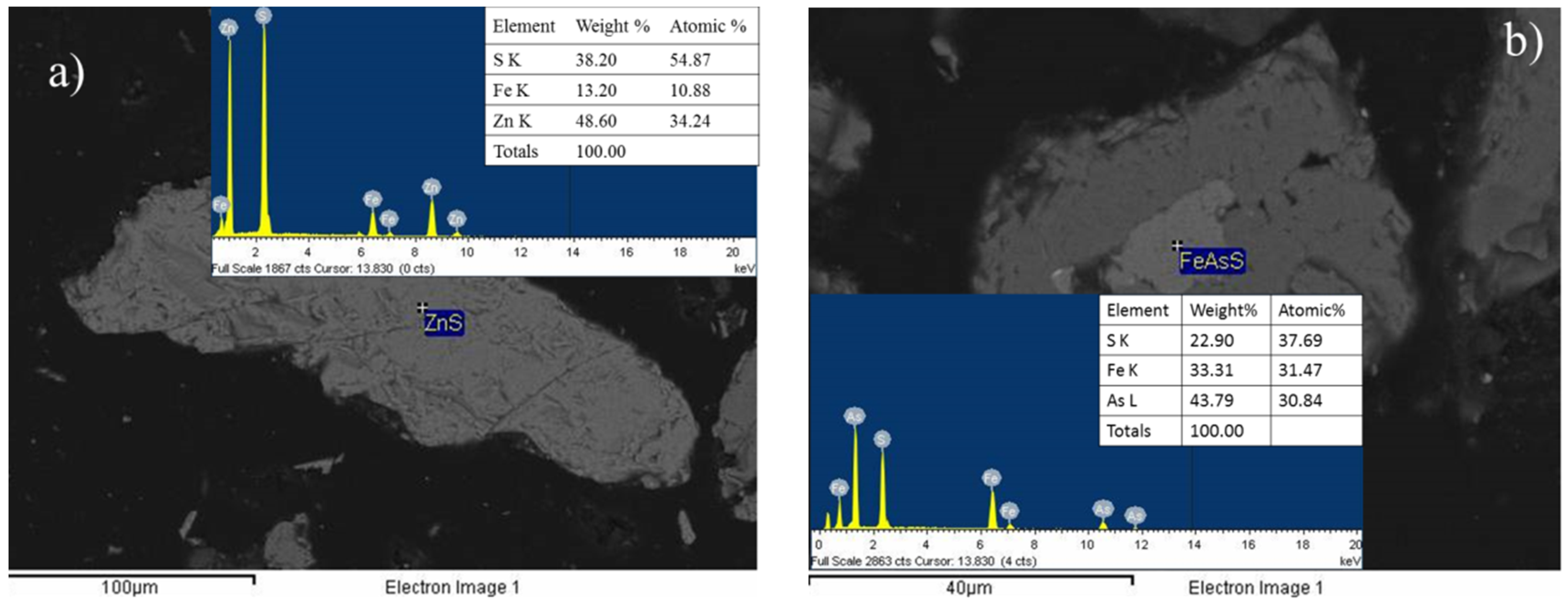

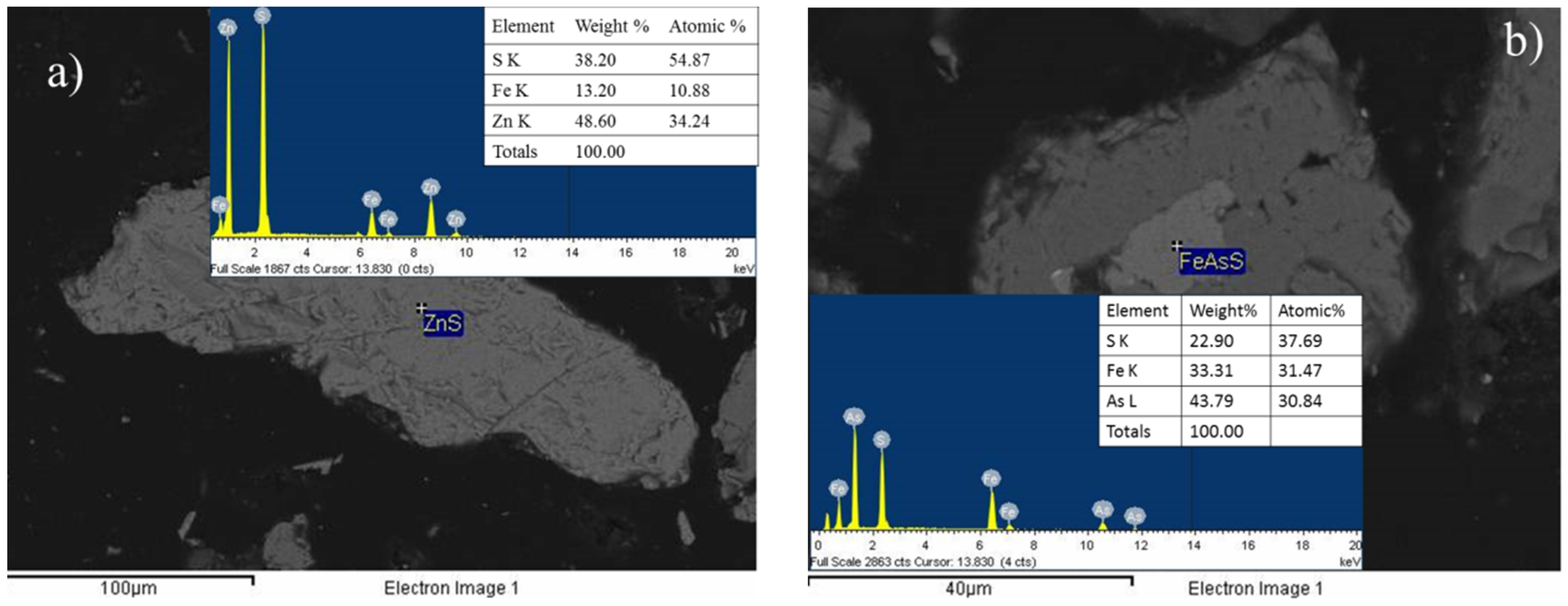

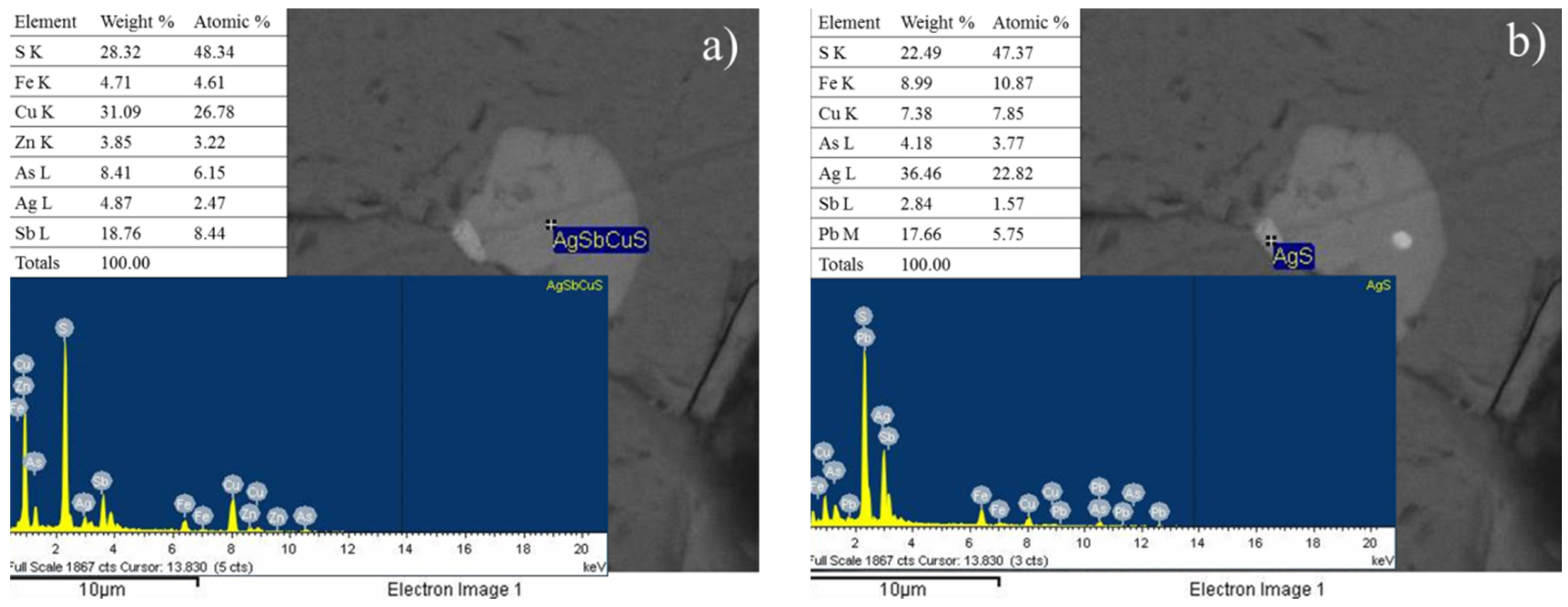

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD) and Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis (SEM)

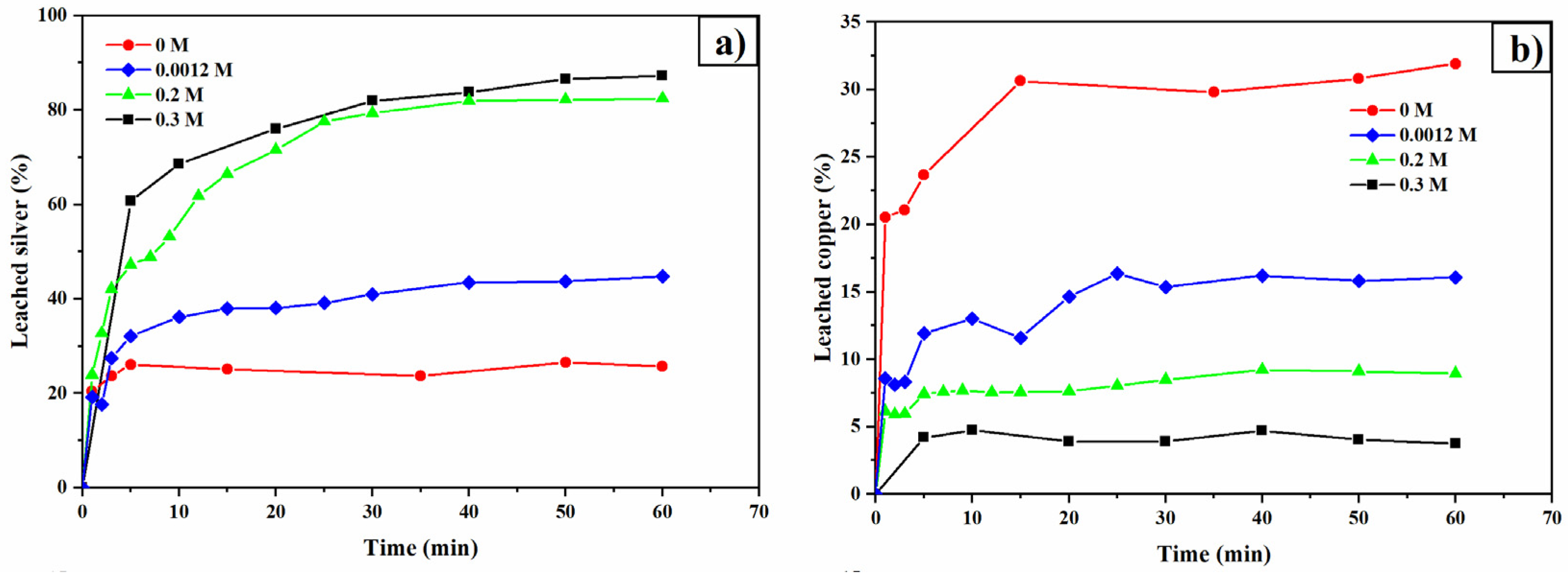

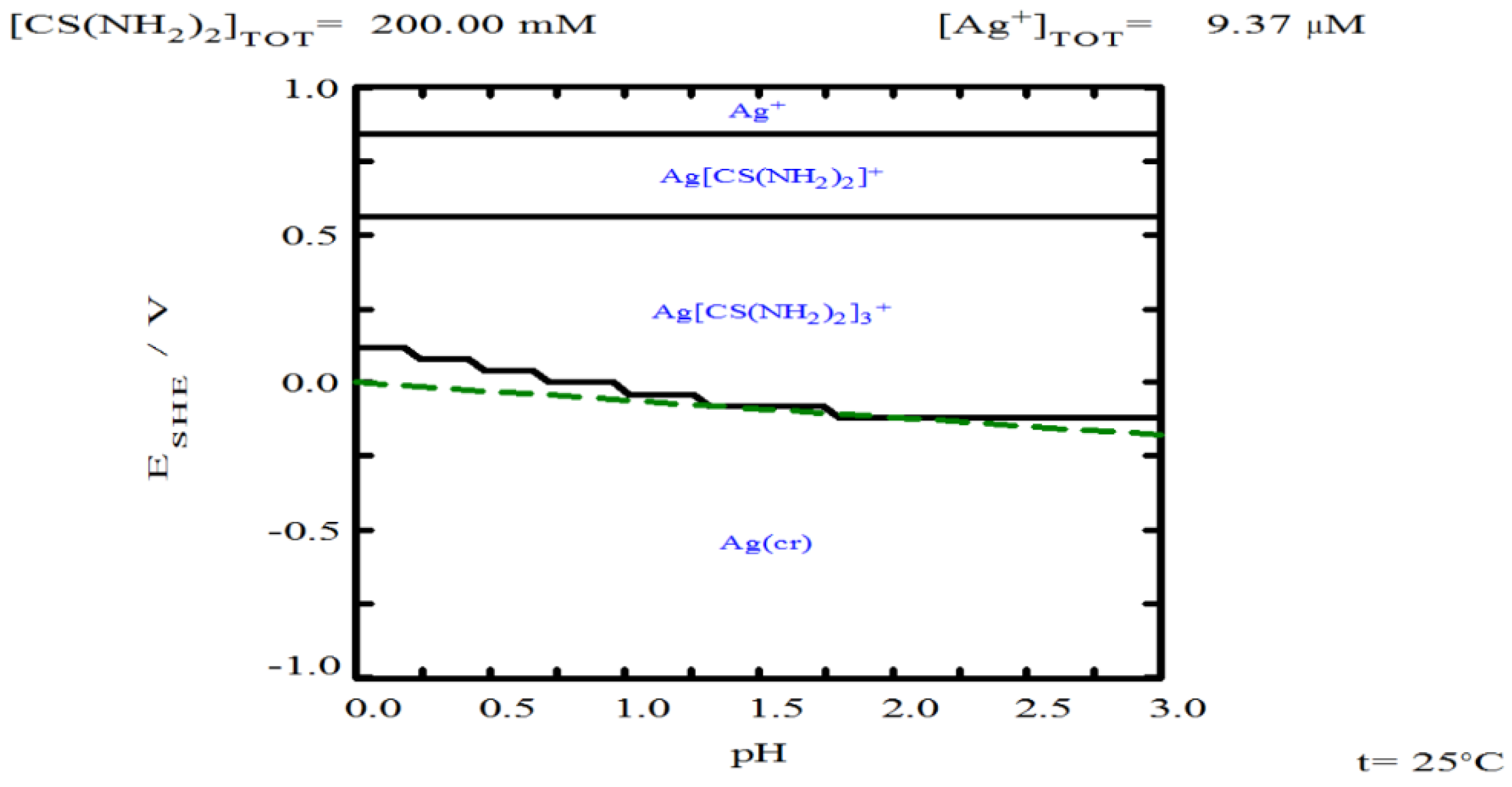

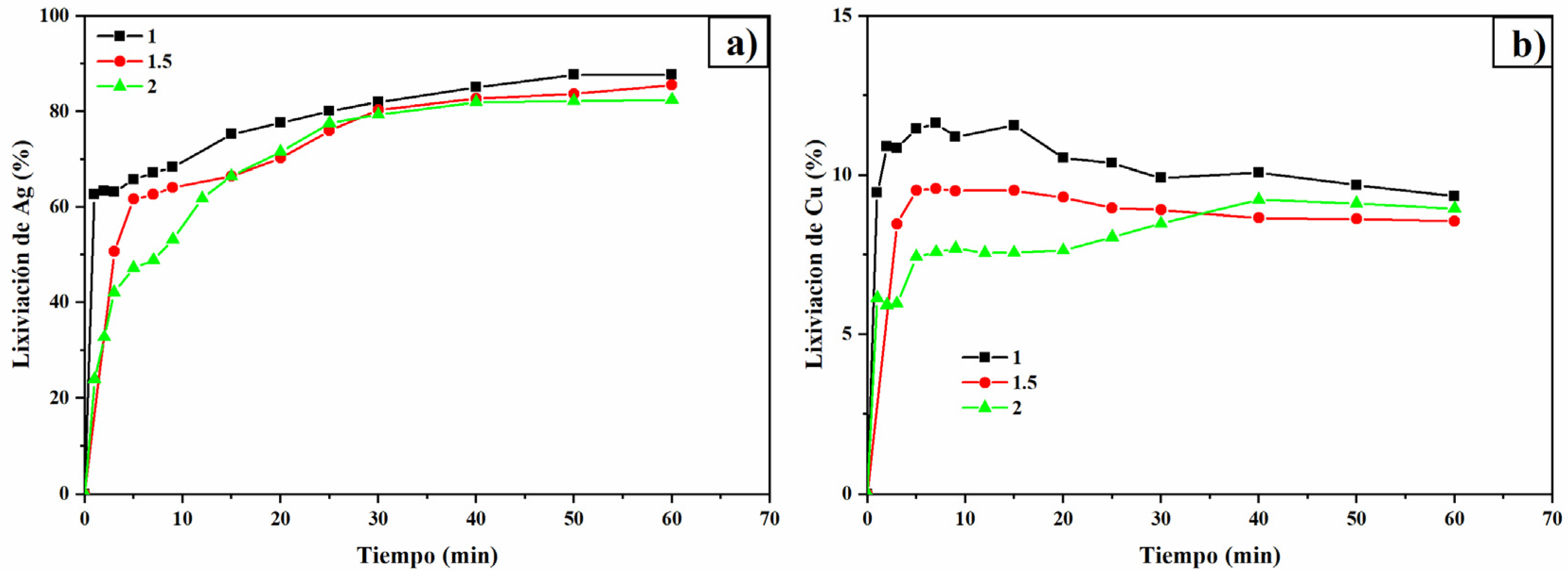

3.4. Thiourea Concentration

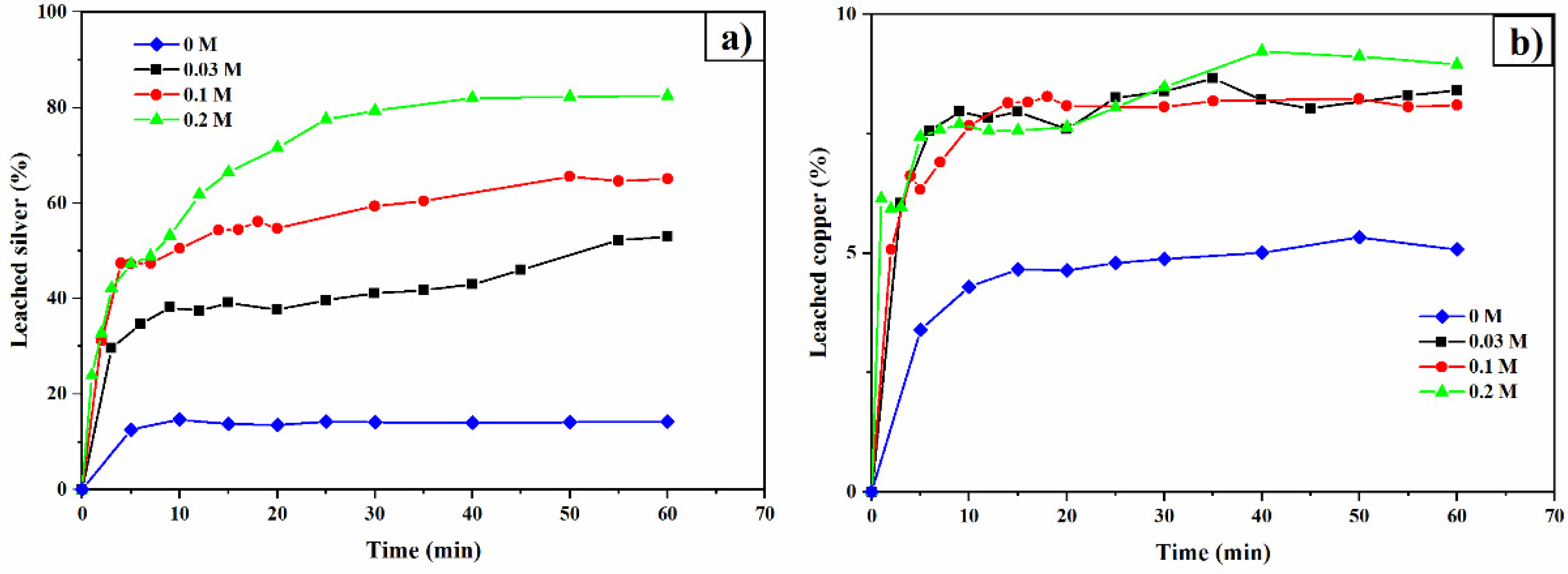

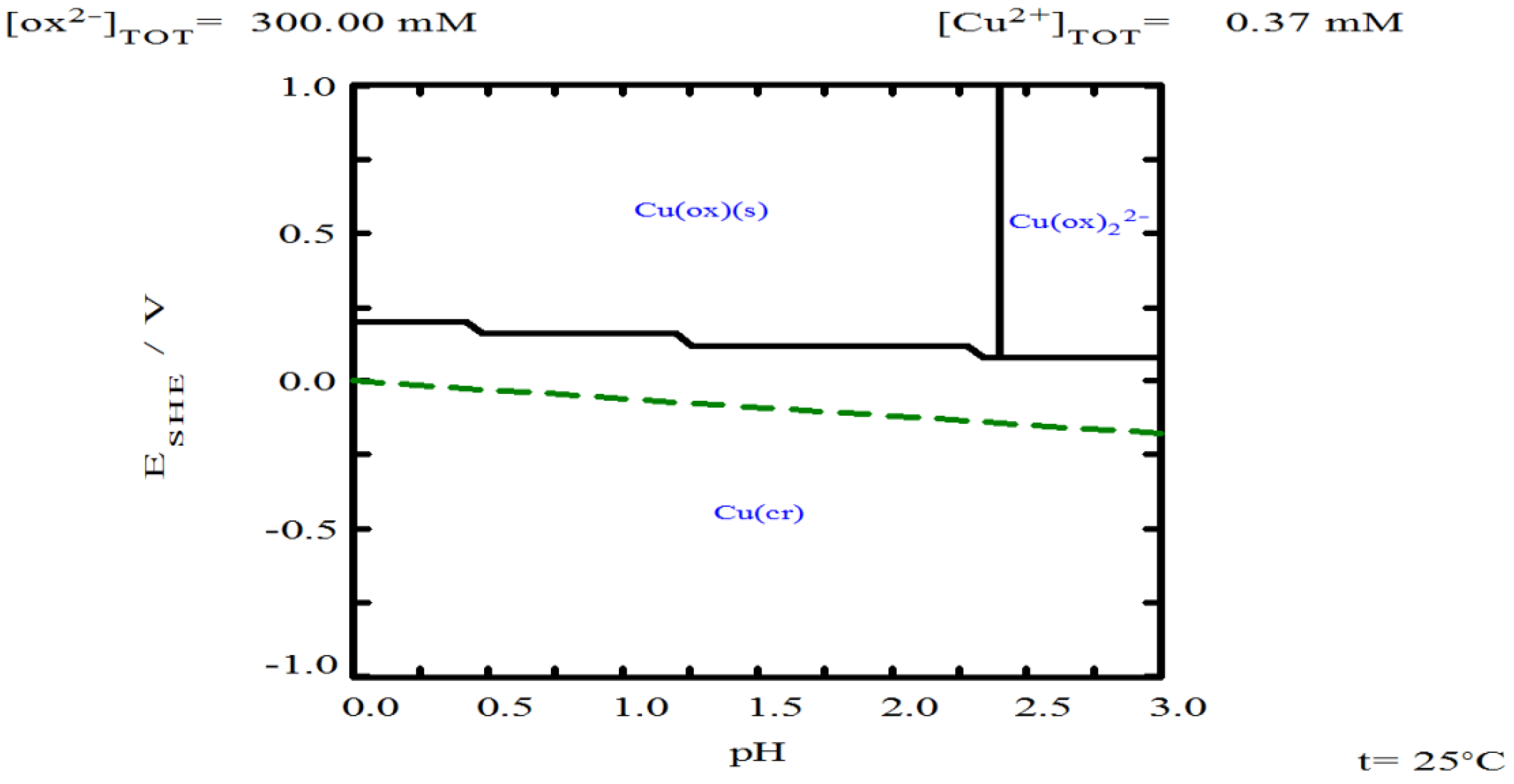

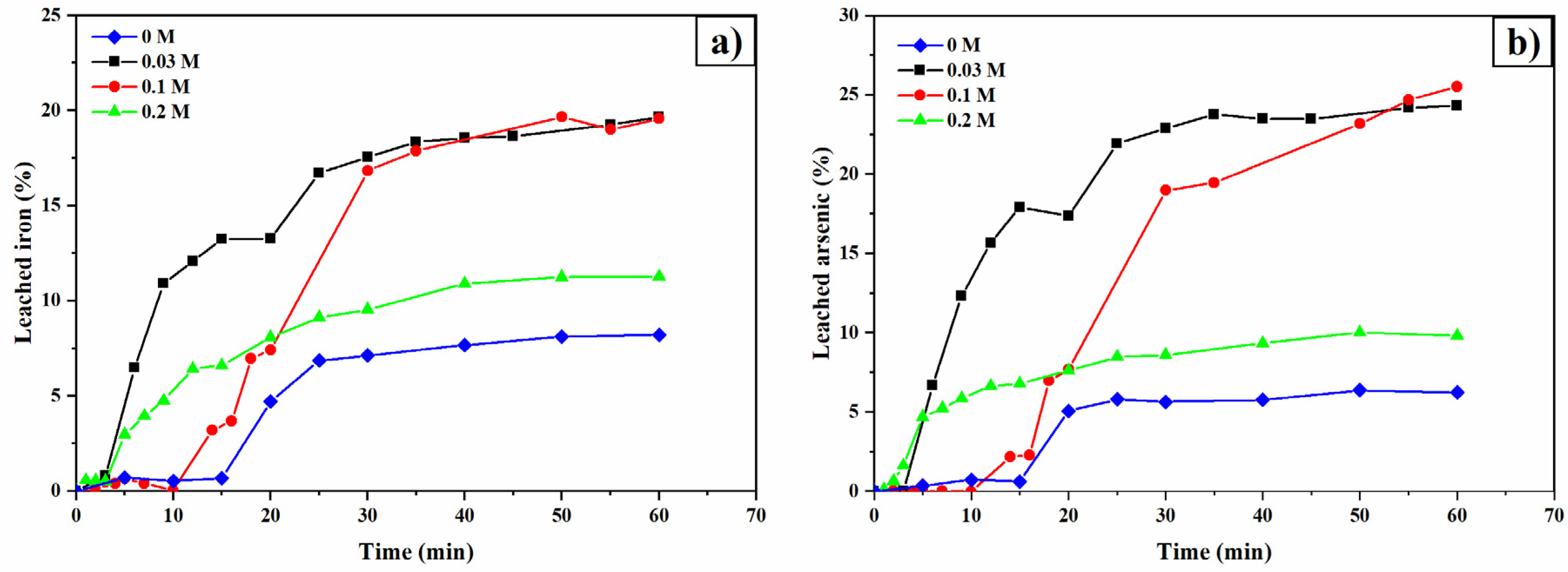

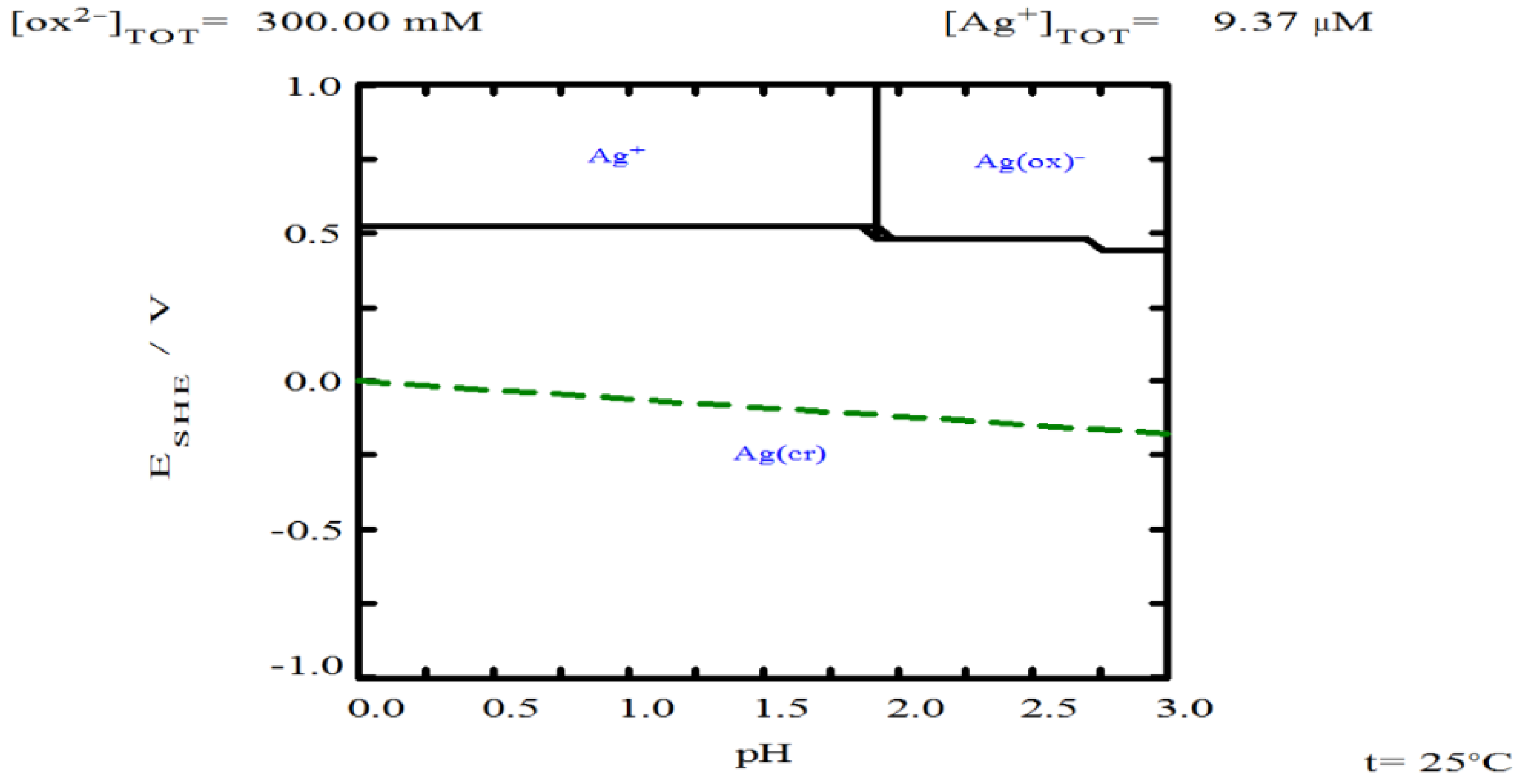

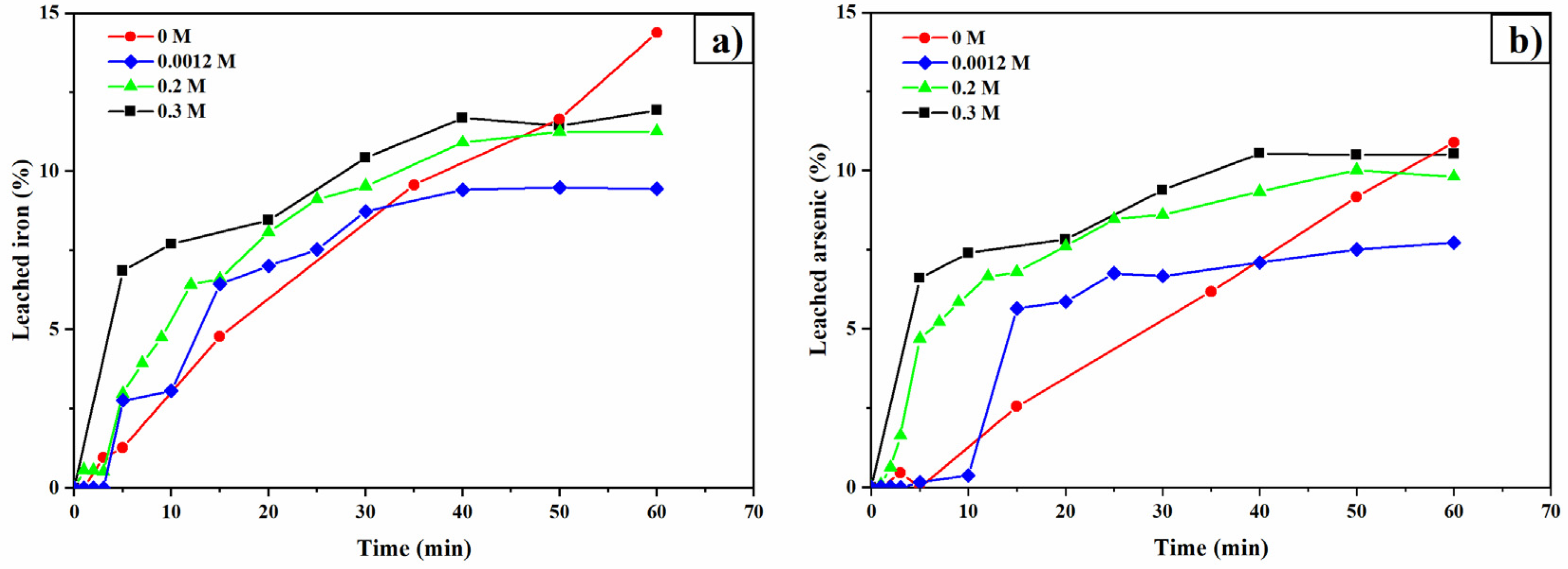

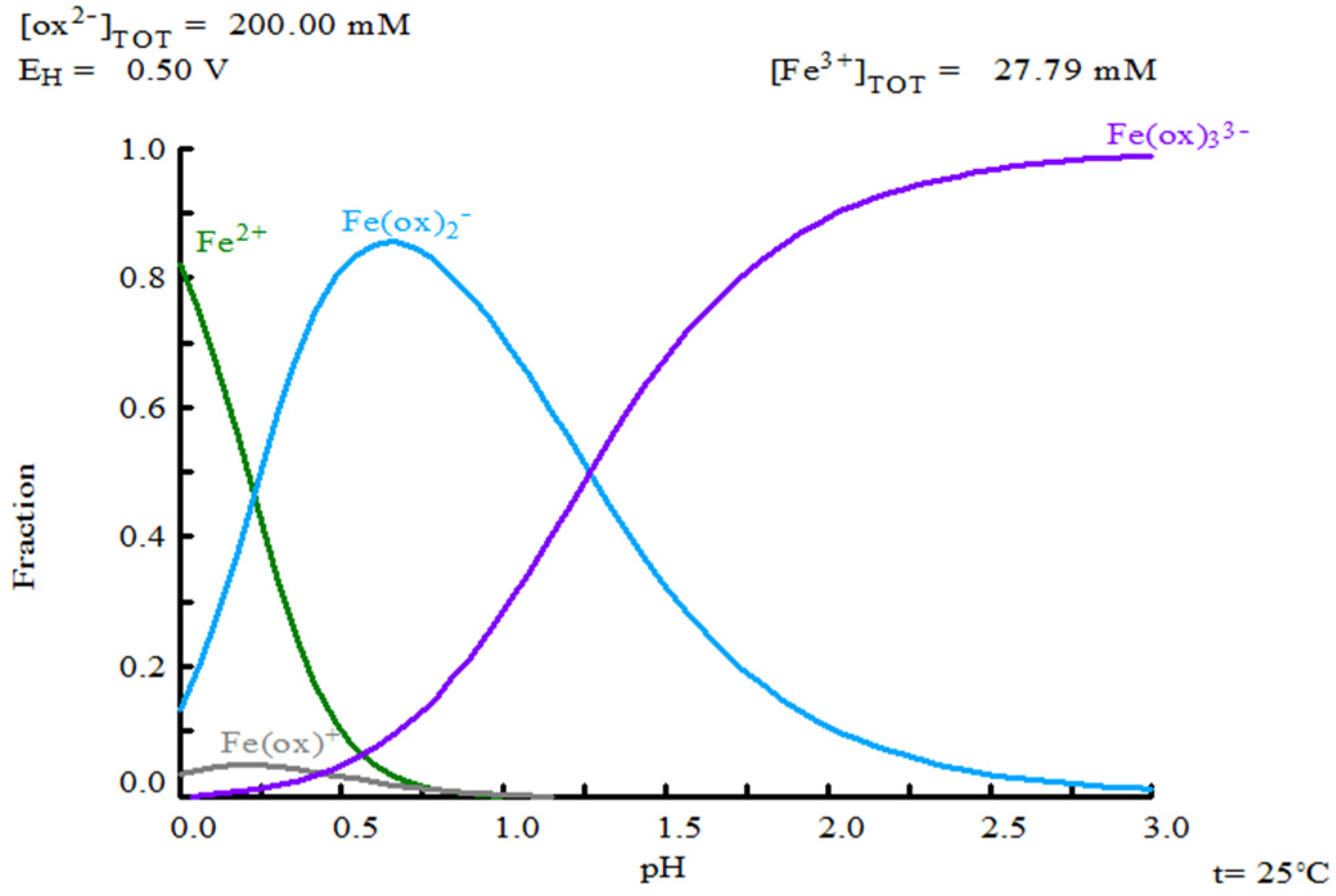

3.5. Oxalate Concentration

3.6. pH Effect

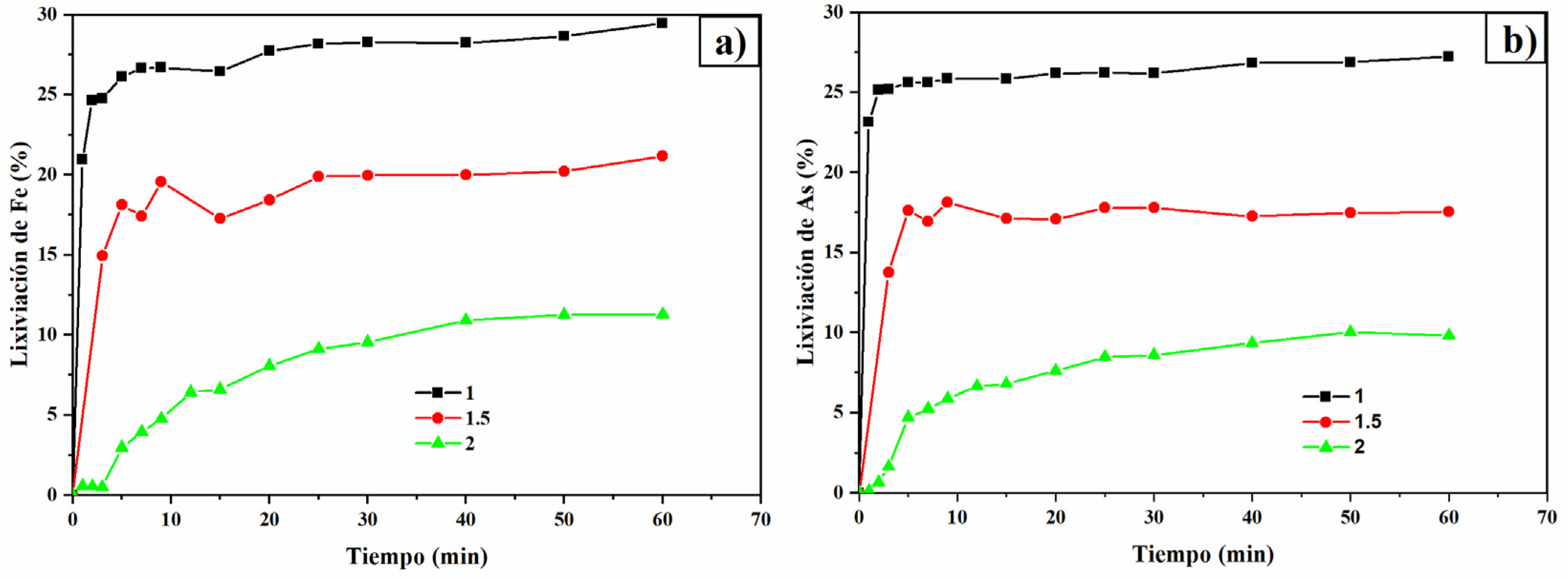

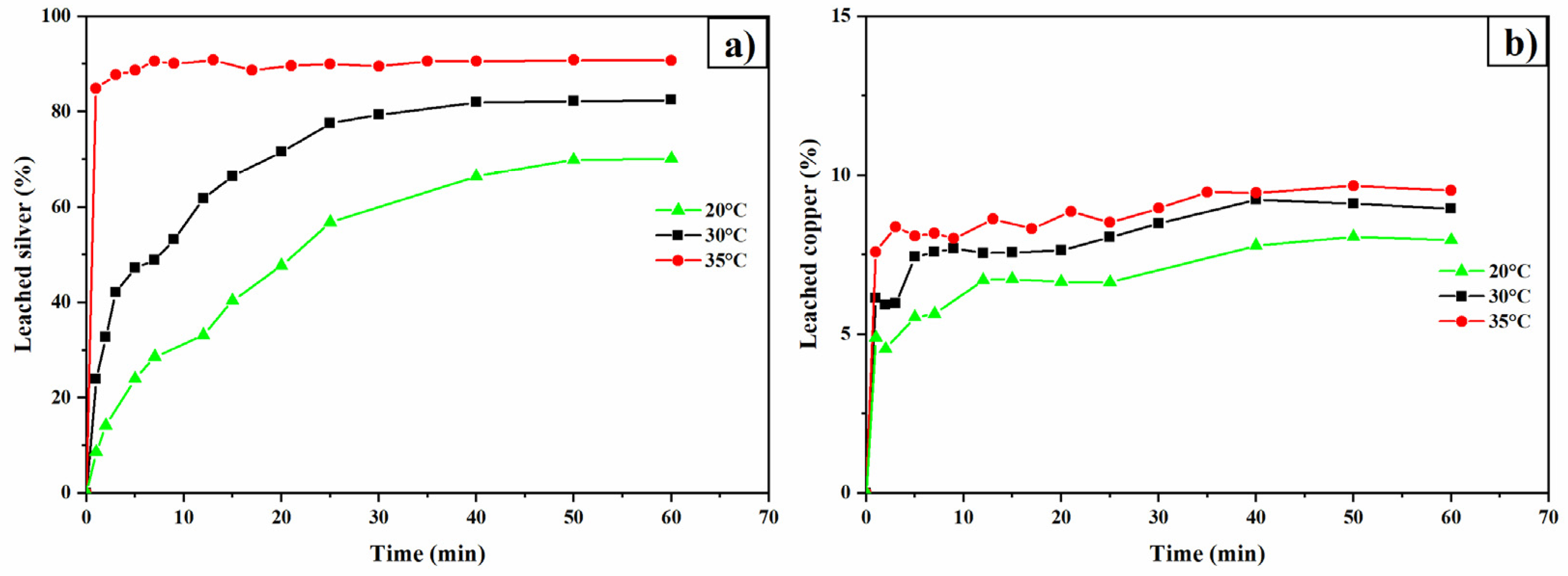

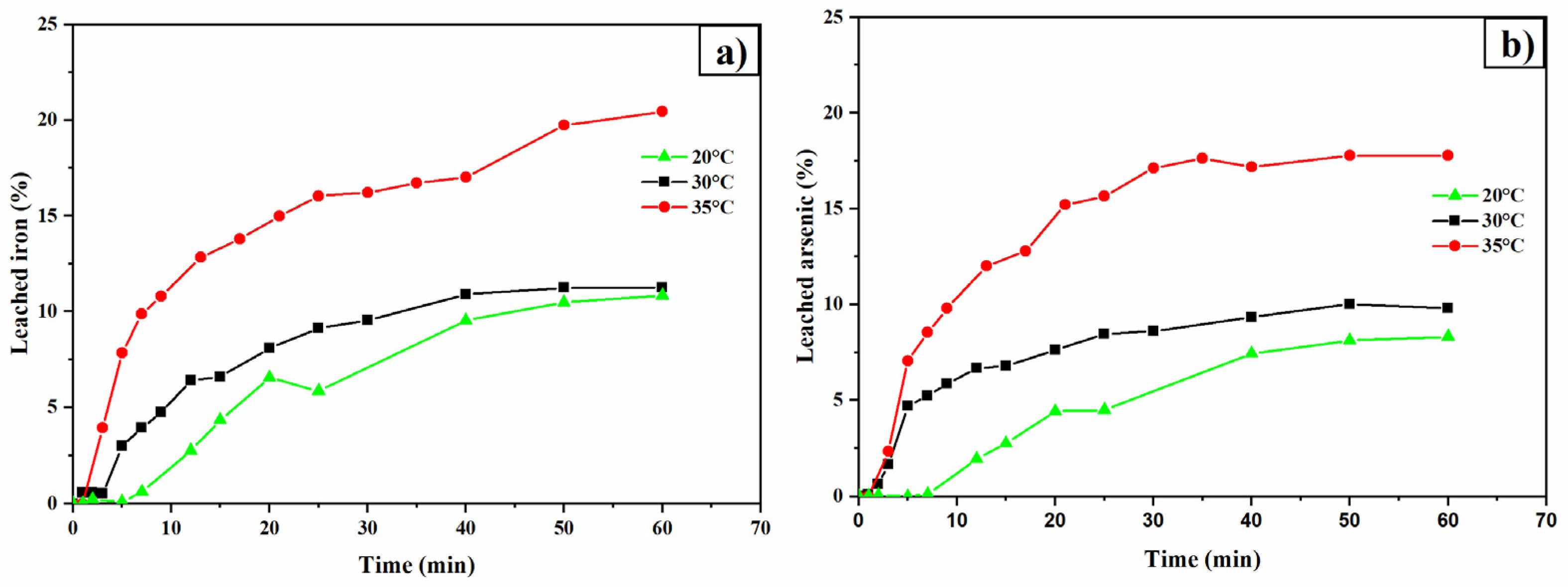

3.7. Temperature Effect

4. Conclusions

- The TU-Ox system represents a suitable option for recovering precious metals present in tailings. This approach adds value to these residues, which are rich in sulfides and may potentially generate acid drainage in the future.

- The most critical variables for optimizing this process are the temperature and the concentrations of thiourea and oxalate.

- The TU-Ox system demonstrated improvements in the leaching process, particularly in the presence of arsenopyrite—a mineral phase that catalyzes the decomposition of thiourea.

- Oxalate helps stabilize thiourea, ensuring its availability to form complexes with silver. However, increasing oxalate concentration can lead to the formation of solid copper oxalate, which creates resistance to the transport of reagents and products.

- Higher temperatures enhance silver leaching, suggesting that the process is chemically controlled. However, elevated temperatures also accelerate thiourea decomposition.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- G.R.Hancock, T.J. G.R.Hancock, T.J.Coulthard. Tailings dams: Assessing the long-term erosional stability of valley fill designs. Science of The Total Environment, November of 25, Volume 849. [CrossRef]

- Juan Lorenzo-Tallafigo, Nieves Iglesias-González, Aurora Romero-García, Alfonso Mazuelos, Pablo Ramírez del Amo, Rafael Romero, Francisco Carranza.. The reprocessing of hydrometallurgical sulphidic tailings by bioleaching: The extraction of metals and the use of biogenic liquors. Minerals Engineering, 2022, Volume 176. [CrossRef]

- Xin Hu, Hong Yang, Keyan Tan, Shitian Hou, Jingyi Cai, Xin Yuan, Qiuping Lan, Jinrong Cao, Siming Yan., Treatment and recovery of iron from acid mine drainage: a pilot-scale study. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2022, Vols. Volume 10. [CrossRef]

- Jason Berberich, Tao Li, Endalkachew Sahle-Demessie. Biosensors for Monitoring Water Pollutants: A Case Study With Arsenic in Groundwater. Separation Science and Technology, 2019,Volume 11.

- Ruiz-Sanchez, Julio C. Juárez Tapia, G.T. Lapidus. Evaluation of acid mine drainage (AMD) from tailings and their valorization by copper recovery. 2022, Vol. 191. [CrossRef]

- Glen, T. Nwailaa, Yousef Ghorbanib, Steven Zhangc, Hartwig Frimmel, León CK Tolmay, Derek H. Rose, Phumzile C. Nwaila, Julie Bourdeauc. Valorisation of mine waste - Part I: Characteristics of, and sampling methodology for, consolidated mineralised tailings by using Witwatersrand gold mines (South Africa) as an example. 2021, Vol. 295. [CrossRef]

- Glen, T. Nwaila, Yousef Ghorban, Steven E. Zhang, Leon C.K. Tolmay, Derek H. Rose, Phumzile C. Nwaila, Julie E. Bourdeau, Hartwig E. Frimme. Valorisation of mine waste - Part II: Resource evaluation for consolidated and mineralised mine waste using the Central African Copperbelt as an example. 2021, Vol. 299. [CrossRef]

- Ömer Canıeren, Cengiz Karagüzel. Silver Metal Extraction from Refractory Silver Ore Using Chloride-Hypochlorite and Hydrochloric Acid Media Under High Pressure. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration, 2021, Vol. 38. [CrossRef]

- Julio, C. Juárez Tapia, Francisco Patiño Cardona, Antonio Roca Vallmajor, Aislinn M. Teja Ruiz, Iván A. Reyes Domínguez, Martín Reyes Pérez, Miguel Pérez Labra and Mizraim U. Flores Guerrero. Determination of Dissolution Rates of Ag Contained in Metallurgical and Mining Residues in the S2O32−-O2-Cu2+ System: Kinetic Analysis. 2018, Vol. 8. [CrossRef]

- Margarita Merkulova, Olivier Mathon, Pieter Glatzel, Mauro Rovezzi, Valentina Batanova, Philippe Marion, Marie-Christine Boiron, and Alain Manceau*. Revealing the Chemical Form of “Invisible” Gold in Natural Arsenian Pyrite and Arsenopyrite with High Energy-Resolution X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy. ACS publications, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Denis Rogozhnikov, Kirill Karimov, Andrei Shoppert, Oleg Dizer, Stanislav Naboichenko. 105525. Kinetics and mechanism of arsenopyrite leaching in nitric acid solutions in the presence of pyrite and Fe(III) ions. Hydrometallurgy, February de 2021, Volume 199. [CrossRef]

- CELEP, İ. ALP, H. DEVECİ, M. VICIL. Characterization of refractory behaviour of complex gold/silver ore by diagnostic leaching. 2009, Pages 707-713. [CrossRef]

- Piervandi, Zeinab. Pretreatment of refractory gold minerals by ozonation before the cyanidation process: A review. 2023, Vol. 11. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo Larrabure, Juan Carlos F. Rodríguez-Reyes. A review on the negative impact of different elements during cyanidation of gold and silver from refractory ores and strategies to optimize the leaching process. Minerals Engineering, 2021, Vol. 173. [CrossRef]

- Chang Lei, Bo Yan, Tao Chen, Xiao-Liang Wang, Xian-Ming Xiao. Silver leaching and recovery of valuable metals from magnetic tailings using chloride leaching. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2018, Vol. 181. [CrossRef]

- Eleazar Salinas-Rodríguez, Juan Hernández-Ávila, Isauro Rivera-Landero, Eduardo Cerecedo-Sáenz, Ma. Isabel Reyes-Valderrama, Manuel Correa-Cruz, Daniel Rubio-Mihi. Leaching of silver contained in mining tailings, using sodium thiosulfate: A kinetic study. Hydrometallurgy, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J. Olson, Corale L. Brierley, Andrew P. Briggs, Ernesto Calmet. Biooxidation of thiocyanate-containing refractory gold tailings from Minacalpa, Peru. 2006, Vol. 81. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Hernandez, E. J. , Teja-Ruíz, A. M., Reyes-Pérez, M., Cobos-Murcia, J. Ángel, Reyes-Cruz, V. E., & Juárez-Tapia, J. C. Estudio preliminar de lixiviación de Polibasita: efecto de la temperatura. Pädi Boletín Científico De Ciencias Básicas E Ingenierías Del ICBI, 2023, Vol. 10. [CrossRef]

- Calla-Choque, D. , Nava-Alonso, F., & Fuentes-Aceituno, J. C. Acid decomposition and thiourea leaching of silver from hazardous jarosite residues: Effect of some cations on the stability of the thiourea system. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Li Jing-ying, Xu Xiu-li, Liu Wen-quan. Thiourea leaching gold and silver from the printed circuit boards of waste mobile phones. 2012, Vol. 32. [CrossRef]

- WOODCOCK, GRAHAM J. SPARROW &JAMES T. Cyanide and Other Lixiviant Leaching Systems for Gold with Some Practical Applications. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review, 1995, Vol. 14. [CrossRef]

- Miller, Jinshan Li & Jan D. A REVIEW OF GOLD LEACHING IN ACID THIOUREA SOLUTIONS. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy, 2006, Vol. 27. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M. S. , Mensah-Biney, R., & Pizarro, R. S. Modern trends in gold processing overview. Minerals Engineering, 1991. [CrossRef]

- Bandehzadeh Masoud1, Aryanimehr Amir, Rezai Bahram. Investigate of Effective Factors on Extraction of Silver from Tailings of Lead Flotation Plant Using Thiourea Leaching. Scientific Research Publishing, 2016. ISSN Online: 2331-4249. [CrossRef]

- Ahamed Ashiq, Janhavi Kulkarni, Meththika Vithanage. Electronic Waste Management and Treatment Technology. Editors: Majeti Narasimha Vara Prasad and Meththika Vithanage. Chapter 10 - Hydrometallurgical Recovery of Metals From E-waste. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2019. [CrossRef]

- BERG, PAUL W. PREISLER AND LOUIS. Oxidation-Reduction Potentials of Thiol-Dithio Systems: Thiourea-Formamidine Disulfide. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1947. [CrossRef]

- J.D Miller, JLi and. [ed.] Gamini Senanayake. Reaction kinetics for gold dissolution in acid thiourea solution using formamidine disulfide as oxidant. Hydrometallurgy, 2002, Pages 215-223. [CrossRef]

- Aylmore. Chapter 27 - Alternative Lixiviants to Cyanide for Leaching Gold Ores. MG. Australia: Gold Ore Processing (Second Edition), 2016, Vols. Pages 447-484. [CrossRef]

- M. Elena Poisot-Díaz, Ignacio González, Gretchen T. Lapidus. Electrodeposition of a Silver-Gold Alloy (DORÉ) from Thiourea Solutions in the Presence of Other Metallic Ion Impurities. Hydrometallurgy, 2008, Vol. 93. [CrossRef]

- Marsden, J.O. House, C.I. The chemistry of gold extraction. SME, 2006. ISBN: 978-0-87335-240-6.

- Calla-Choque, D. , & Nava-Alonso, F. THIOUREA DETERMINATION FOR THE PRECIOUS METALS LEACHING PROCESS BY IODATE TITRATION. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, M.I. Jeffrey. A fundamental study of ferric oxalate for dissolving gold in thiosulfate solutions. Hydrometallurgy, 2005. [CrossRef]

- D.Calla-Choque, G.T. D.Calla-Choque, G.T.Lapidus and. [ed.] Gamini Senanayake. Acid decomposition and silver leaching with thiourea and oxalate from an industrial jarosite sample. Hydrometallurgy, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Calla-Choque, G.T. D. Calla-Choque, G.T. Lapidus. Jarosite dissolution kinetics in the presence of acidic thiourea and oxalate media. Hydrometallurgy, 21, Vol. 200. doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2021.105565. 20 March.

- SGM. Panorama Minero del Estado de Hidalgo. Mexicano, Servicio Geológico. [En línea] 29 de Julio de 2021. [Citado el: 2022 de 08 de 11.] https://www.gob.mx/sgm/es/articulos/consulta-los-panoramas-mineros-estatales.

- Ángel Ruiz-Sánchez, Gretchen T. Lapidus. Study of chalcopyrite leaching from a copper concentrate with hydrogen peroxide in aqueous ethylene glycol media. Hydrometallurgy, 2017. [CrossRef]

- NOM-141-SEMARNAT-2003, Norma Oficial Mexicana. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-141-SEMARNAT-2003, Que establece el procedimiento para caracterizar los jales, así como las especificaciones y criterios para la caracterización y preparación del sitio, proyecto, construcción, operación y postoperación de presa. Diario Oficial de la Federación.

- Petersen, Leif. Chemical Determination of Pyrite in Soils. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, 1969. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.T. Patent and Trademark Office. No. 4,334,882. Washington, DC: U.S, 1982.

- NMX-B-021-1982, Norma Mexicana. Determinación de las formas de azufre en el carbón. Dirección General de Normas. Secretaría de Comercio y Fomento Industrial.

- Erick Jesús Muñoz Hernández, Aislinn Michelle Teja Ruiz, Martin Reyes Pérez, Gabriel Cisneros Flores, Miguel Pérez Labra, Francisco Raúl Barrientos Hernández & Julio Cesar Juárez Tapia. Leaching of Arsenopyrite Contained in Tailings Using the TU-OX System. Springer, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xue-yi Guo, Lei Zhang, Qing-hua Tian, Hong Qin. Stepwise extraction of gold and silver from refractory gold concentrate calcine by thiourea. Hydrometallurgy, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Hernandez, E. J. , Teja-Ruíz, A. M., Reyes-Pérez, M., Reyes-Domínguez, I. A., Urbano-Reyes, G., & Juárez-Tapia, J. C. Lixiviación de Pb y Zn empleando el sistema Tiourea-EDTA. 2022, Vol. 10.

- Ke Li, Qian Li, Yongbin Yang, Bin Xu, Tao Jiang, Rui Xu.. The Role of Oxalate on Thiourea Leaching of Gold in the Presence of Jarosite. SSRN, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, E, et al. Monosodium Glutamate as Selective Lixiviant for Alkaline Leaching of Zinc and Copper from Electric Arc Furnace Dust. Metals, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yukun Huang, Dasong Wang, Hongtu Liu, Guixia Fan, Weijun Peng, Yijun Cao. Selective complexation leaching of copper from copper smelting slag with the alkaline glycine solution: An effective recovery method of copper from secondary resource. Separation and Purificacion Technology, 2023, Vol. 326. [CrossRef]

- Andrew Churg MD, Nestor L. Muller MD. Update on Silicosis. Surgical Pathology Clinics, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ilhwan Park, Carlito Baltazar Tabelin, Sanghee Jeon, Xinlong Li, Kensuke Seno, Mayumi Ito, Naoki Hiroyoshi. A review of recent strategies for acid mine drainage prevention and mine tailings recycling. Chemosphere, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Laura, J. Swinkels, Mathias Burisch, Constantin M. Rossberg, Marcus Oelze, Jens Gutzmer, Max Frenzel. Gold and silver deportment in sulfide ores – A case study of the Freiberg epithermal Ag-Pb-Zn district, Germany. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Moreno Tovar, Raúl, & Barbanson, Luc, & Coreño Alonso, Oscar. Neoformación mineralógica en residuos mineros (jales) del distrito minero Zimapán, estado de Hidalgo, México. Minería y Geología, 2009. ISSN: 0258-8959.

- Raúl MORENO TOVAR, Jesús TÉLLEZ HERNÁNDEZ y Marcos G. MONROY FERNÁNDEZ. Influencia de los minerales de los jales en la bioaccesibilidad de arsénico, plomo, zinc y cadmio en el distrito minero Zimapán, México. Revista internacional de contaminación ambiental, 2012. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-49992012000300003&lng=es&tlng=es.. ISSN 0188-4999.

- C.L. Corkhill, D.J. C.L. Corkhill, D.J. Vaughan. Arsenopyrite oxidation – A review. Applied Geochemistry, 2009. [CrossRef]

- D.W. Blowes, C.J. D.W. Blowes, C.J. Ptacek, J.L. Jambor, C.G. Weisener, D. Paktunc, W.D. Gould, D.B. Johnson. 11.5 - The Geochemistry of Acid Mine Drainage. Treatise on Geochemistry, 2014.

- Nelson Belzile, Stephanie Maki, Yu-Wei Chen, Douglas Goldsack. Inhibition of pyrite oxidation by surface treatment. Science of The Total Environment, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Anssi Karppinen, Sipi Seisko, Mari Lundström. Atmospheric leaching of Ni, Co, Cu, and Zn from sulfide tailings using various oxidants. Minerals Engineering, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A.N. Buckley, H.J. A.N. Buckley, H.J. Wouterlood, R. Woods. The surface composition of natural sphalerites under oxidative leaching conditions. Hydrometallurgy, 1989. [CrossRef]

- S.K.Halda, Josip Tišljar. Chapter 1 - Rocks and Minerals. Introduction to mineralogy and petrology. Elsevier, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Kissin, H. S.A. Kissin, H. Mango. 13.16 - Silver Vein Deposits. Treatise on Geochemistry. Elsevier Science, 2014, Vol. 13.

- Puigdomenech, I. MEDUSA: make equilibrium diagrams using sophisticated algorithms. Inorganic chemistry, 2004.

- Ke Li, Qian Li, Yan Zhang, Xiaoliang Liu, Yongbin Yang, Tao Jiang. Thiourea leaching of gold: Elucidating the mechanism of arsenopyrite catalyzed thiourea oxidation by Fe3+ and the beneficial role of oxalate through experimental and density functional theory (DFT) investigations. Minerals Engineering, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xiyun Yang, Michael S. Moats, Jan D. Miller, Xuming Wang, Xichang Shi, Hui Xu. Thiourea–thiocyanate leaching system for gold. Hydrometallurgy, 2011, Vol. 106. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sánchez, I. Lázaro, G.T. Lapidus. Improvement effect of organic ligands on chalcopyrite leaching in the aqueous medium of sulfuric acid hydrogen peroxide-ethylene glycol. Hydrometallurgy, 2020, Volume 193. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Poisot-Diaz, I. M.E. Poisot-Diaz, I. Gonzalez, G.T. Lapidus. Electrodeposition of a silver-gold alloy (DORE) from thiourea solutions in the presence of other metallic ion impurities. Hydrometallurgy, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Martell, A. E. , Smith, R. M. Critical stability constants. Volume 6: Second supplement. Plenum press, 1974.

- Smith, R. M. , Martell, A. E.. Critical stability constants: volume 2: amines. Springer Science & Business Media, 1975.

| Effervescence Degree (Carbonate Neutralization) | HCl 1 N Volume (mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 hours | 24 hours | |

| None | 1 | 1 |

| Low | 2 | 1 |

| Moderate | 2 | 2 |

| Strong | 3 | 2 |

| Particle Size (μm) | Elemental Composition (Kg/t) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag* | Cu | Fe | As | |

| >150 | 30 | 1.13 | 65.69 | 2.52 |

| -150 + 105 | 20 | 1.01 | 78.60 | 4.39 |

| -105 + 74 | 20 | 0.82 | 78.51 | 4.81 |

| -74 + 53 | 70 | 0.45 | 68.37 | 8.60 |

| -53 + 37 | 120 | 2.65 | 152.38 | 13.05 |

| <37 | 180 | 2.68 | 73.75 | 7.33 |

| *Composition expressed in g/ton | ||||

| Particle Size (μm) | (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | Cu | Fe | As | |

| >150 | 17.06 | 28.18 | 25.07 | 14.10 |

| -150 + 105 | 10.91 | 21.99 | 26.20 | 21.49 |

| -105 + 74 | 6.03 | 10.98 | 15.95 | 14.34 |

| -74 + 53 | 20.54 | 5.32 | 12.20 | 22.55 |

| -53 + 37 | 15.39 | 14.18 | 12.43 | 15.63 |

| <37 | 30.08 | 19.36 | 8.14 | 11.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).