Submitted:

01 October 2024

Posted:

01 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

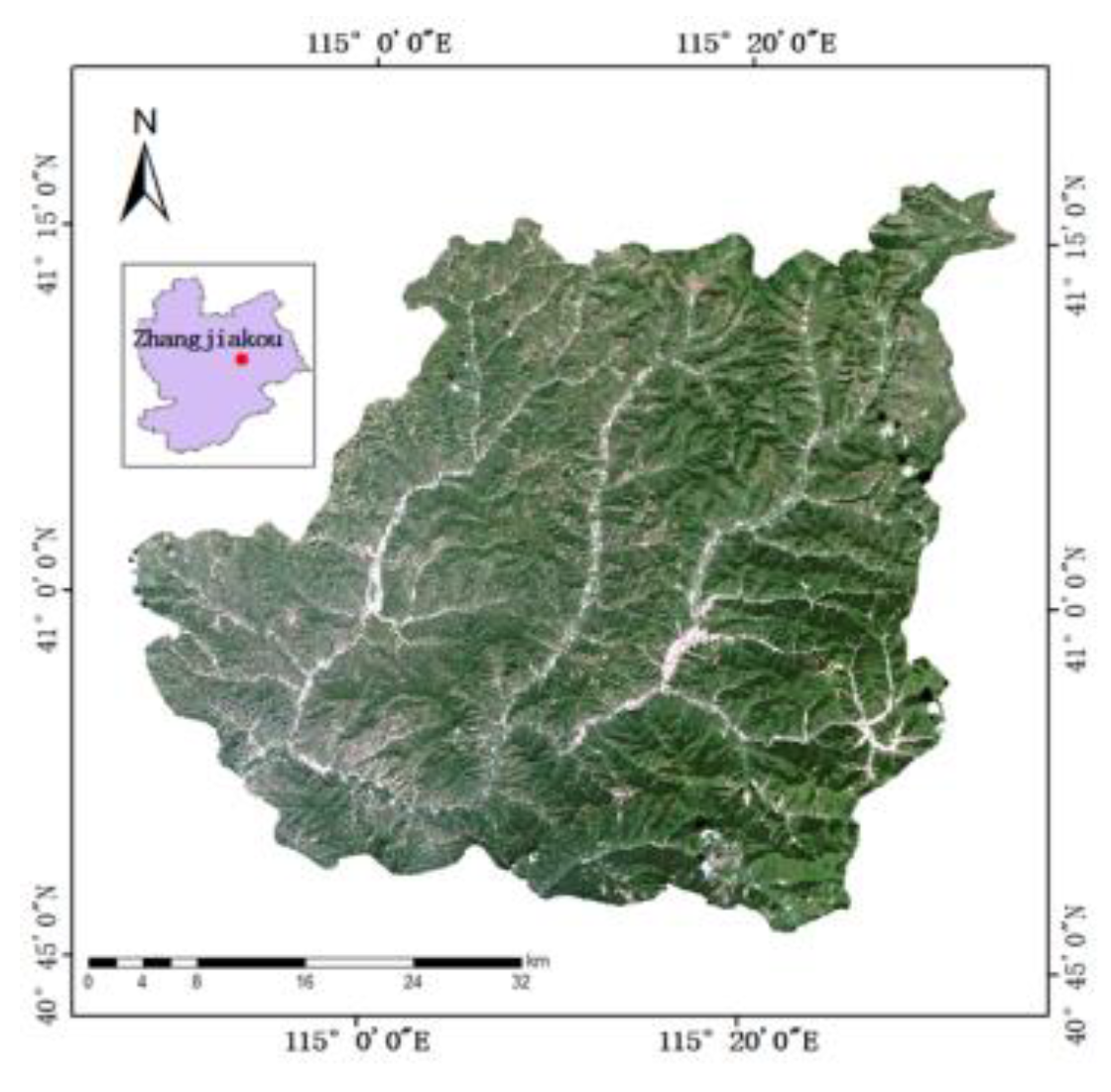

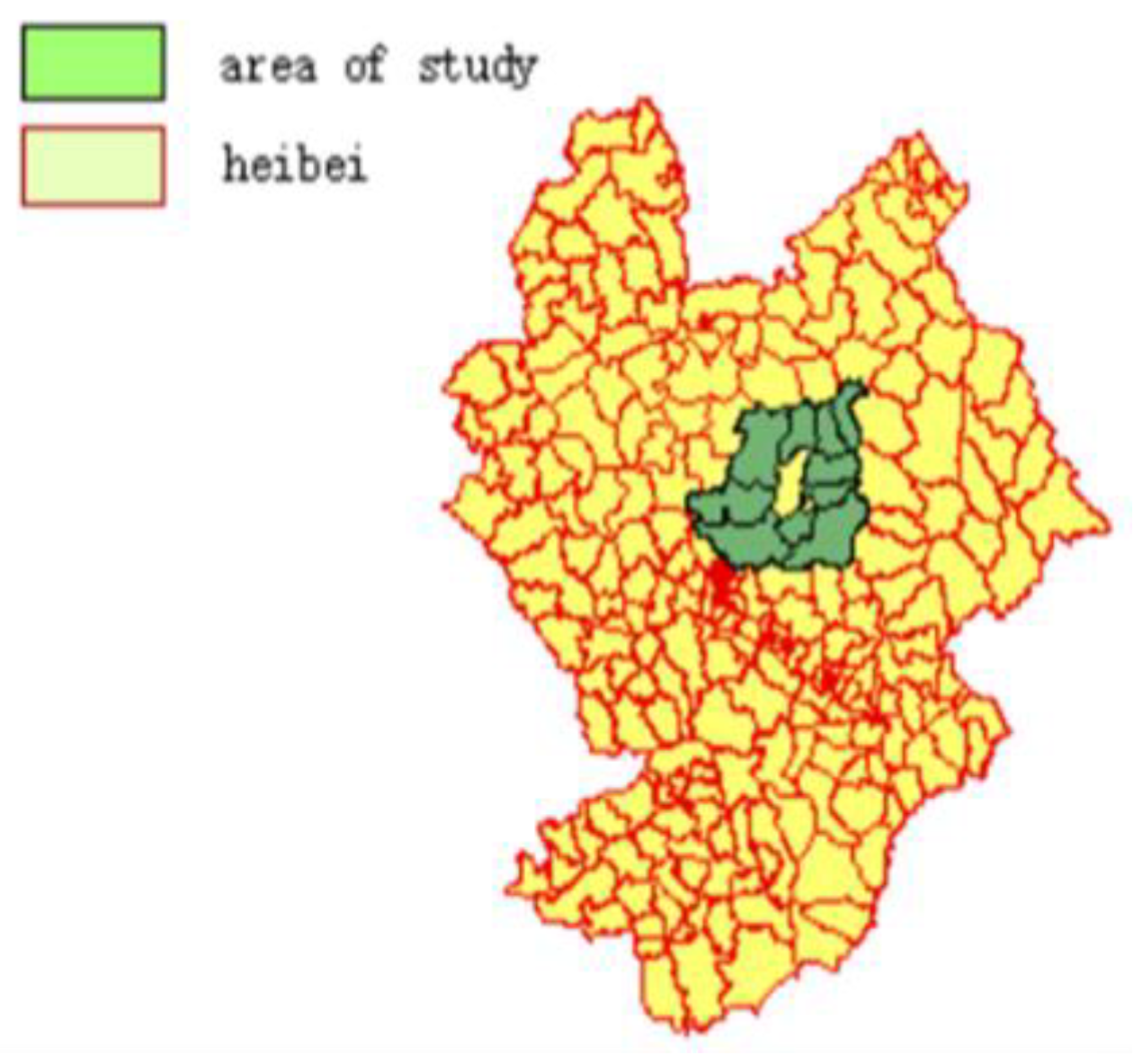

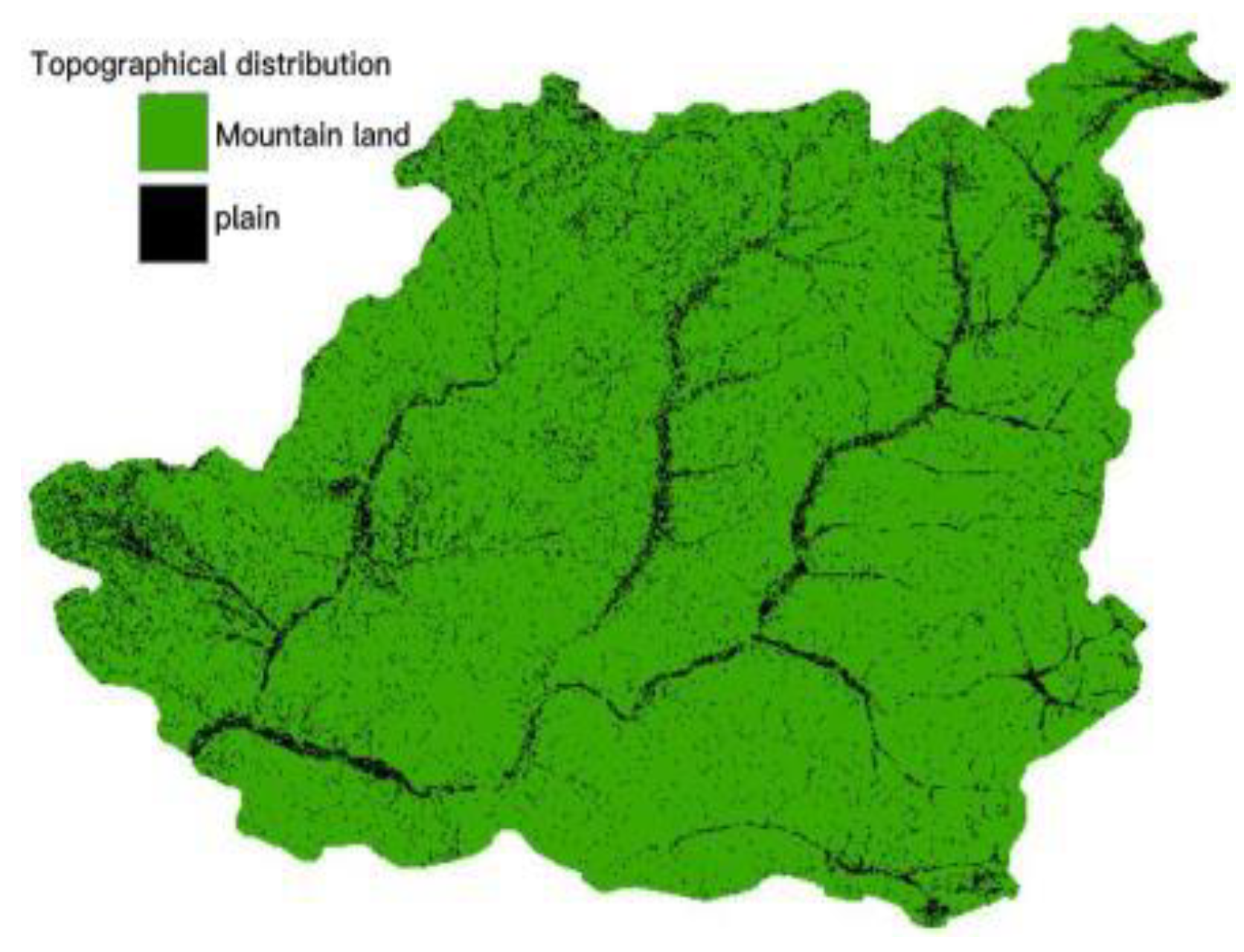

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Overview of the Study Area

2.2.1. Selection of Data Source

2.2.2. Sample Area DEM Data Acquisition

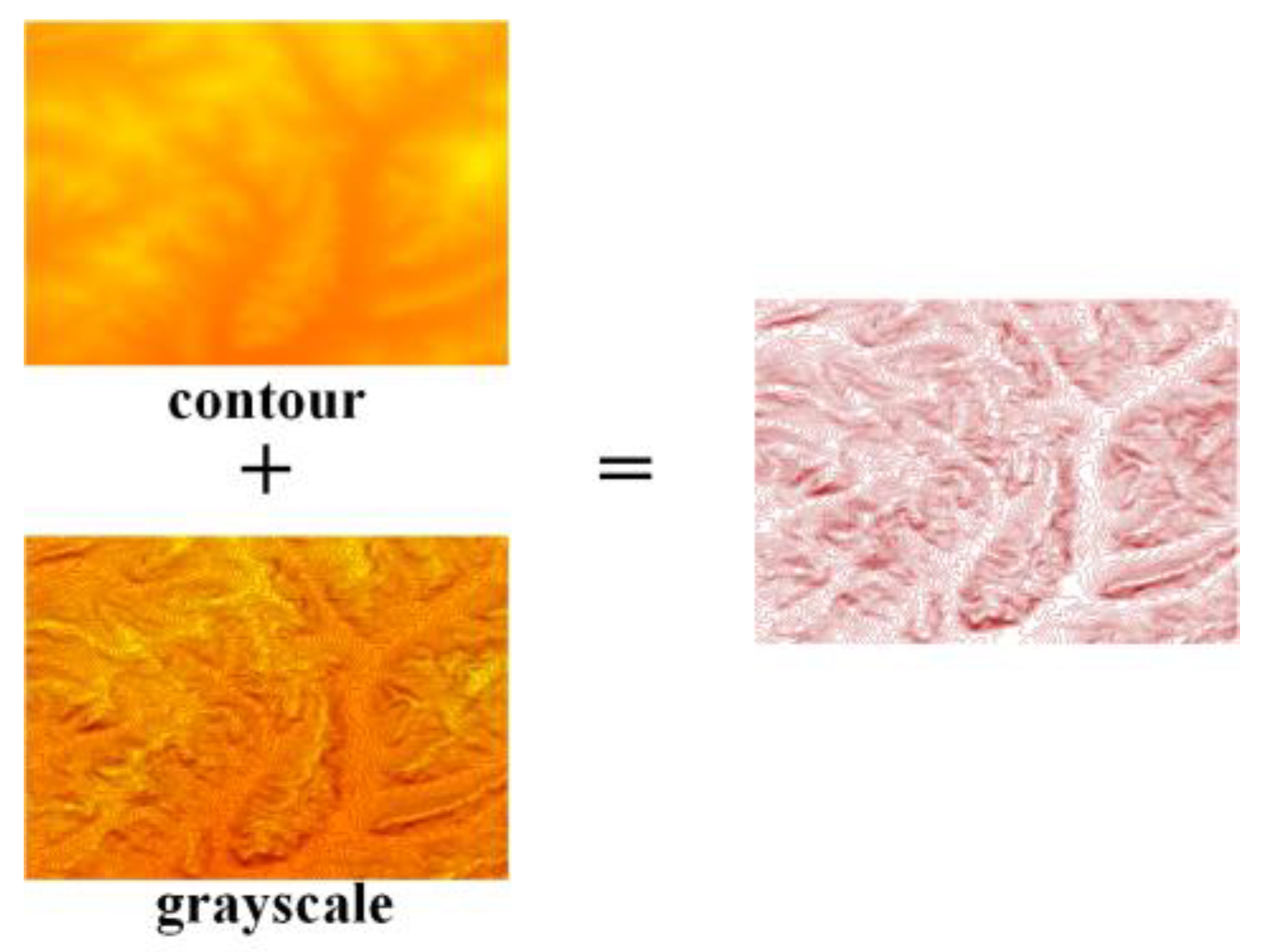

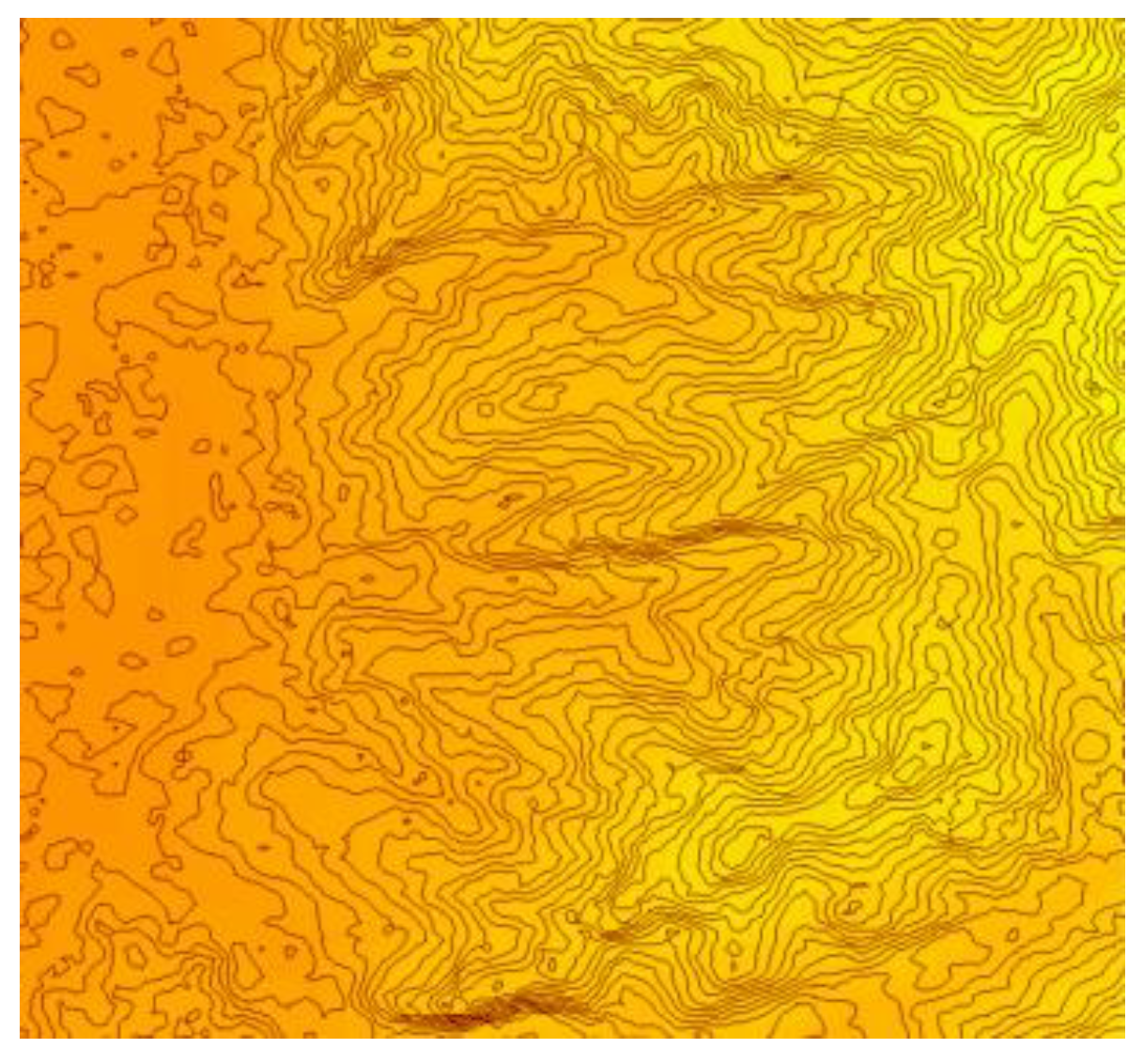

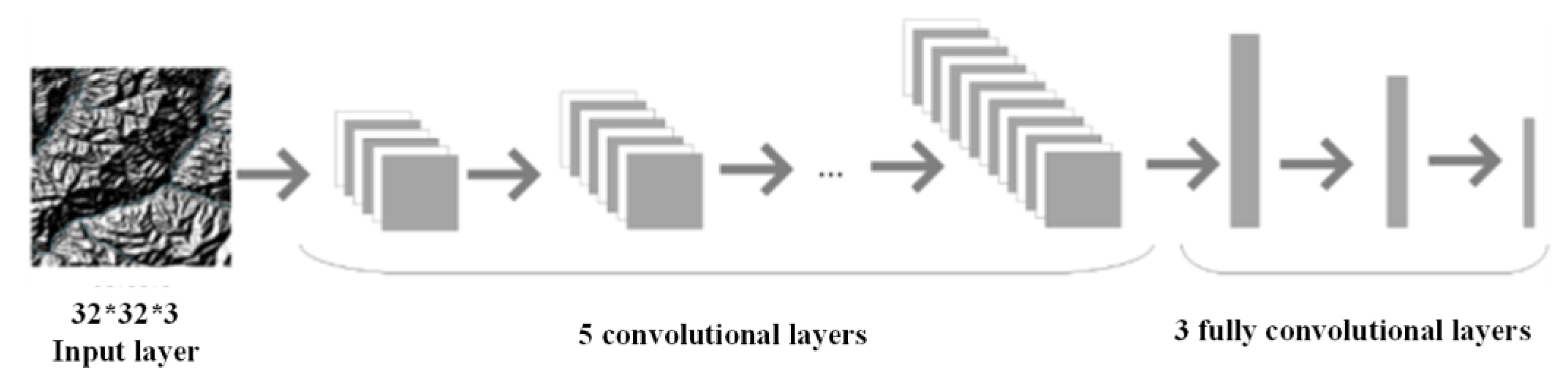

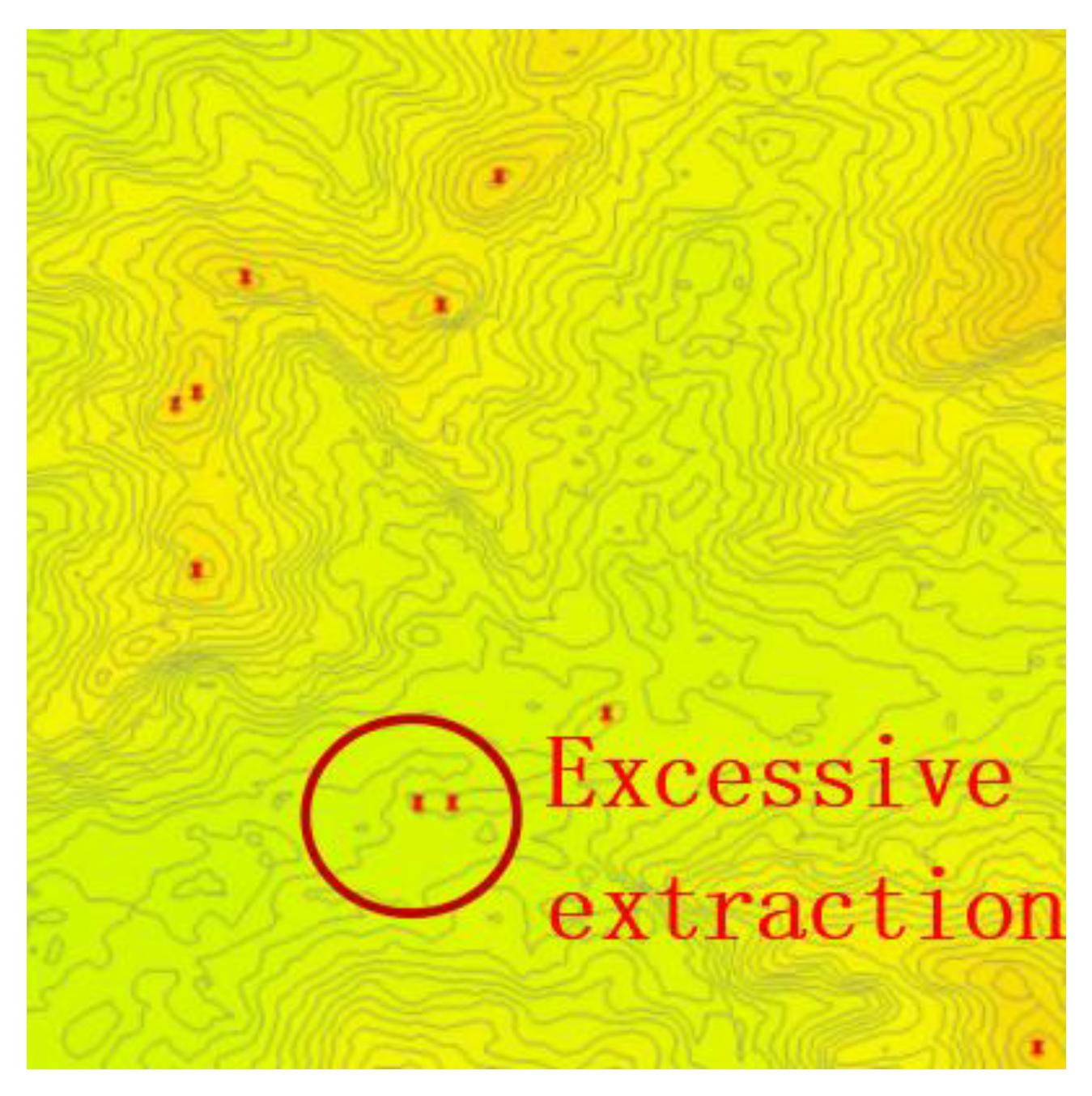

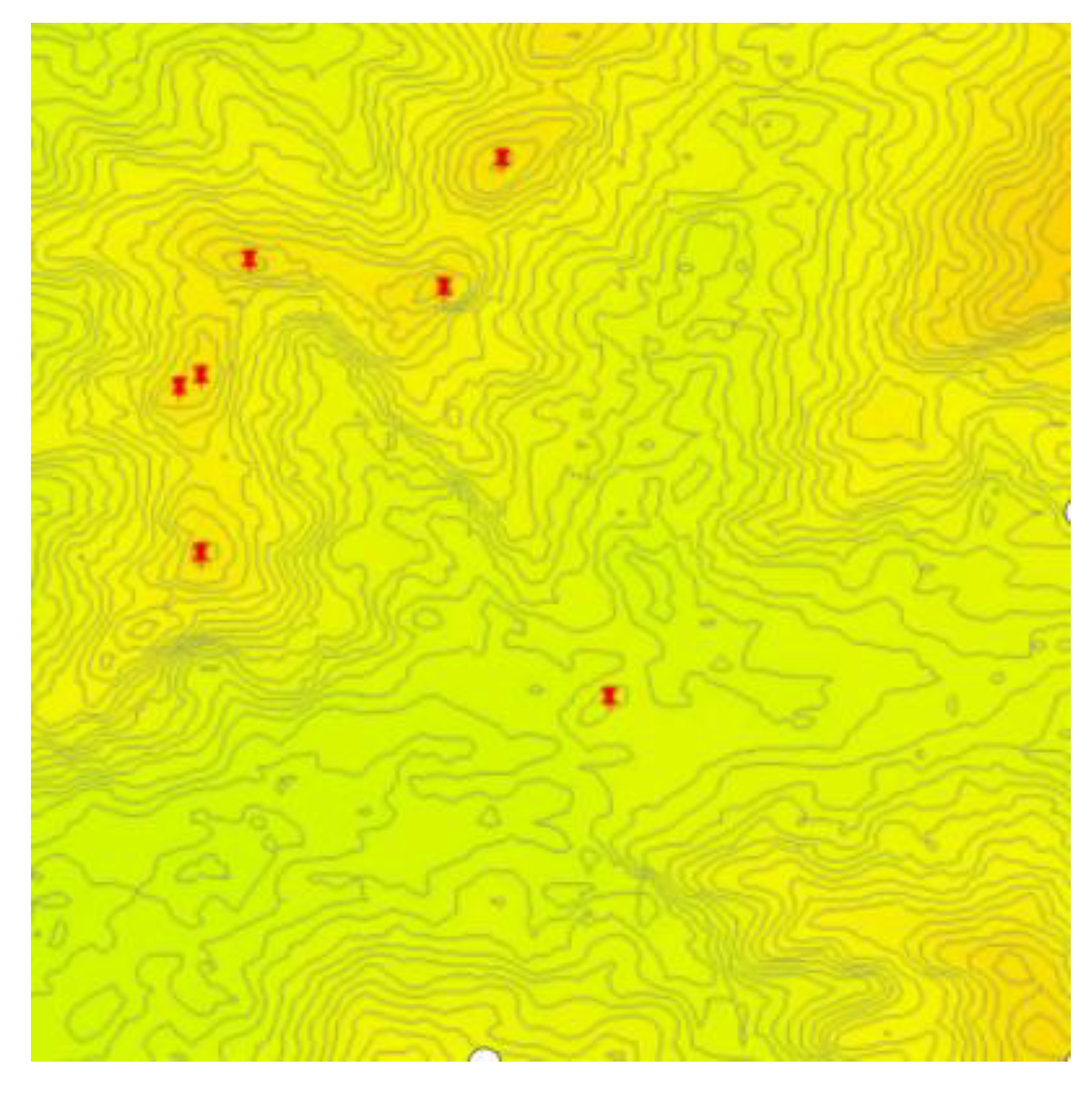

2.3. Extraction of Mountain top Points Based on DEM and Deep Learning

2.3.1. Definition of Mountain Top Point

2.3.2. Extraction of Mountain Top Point

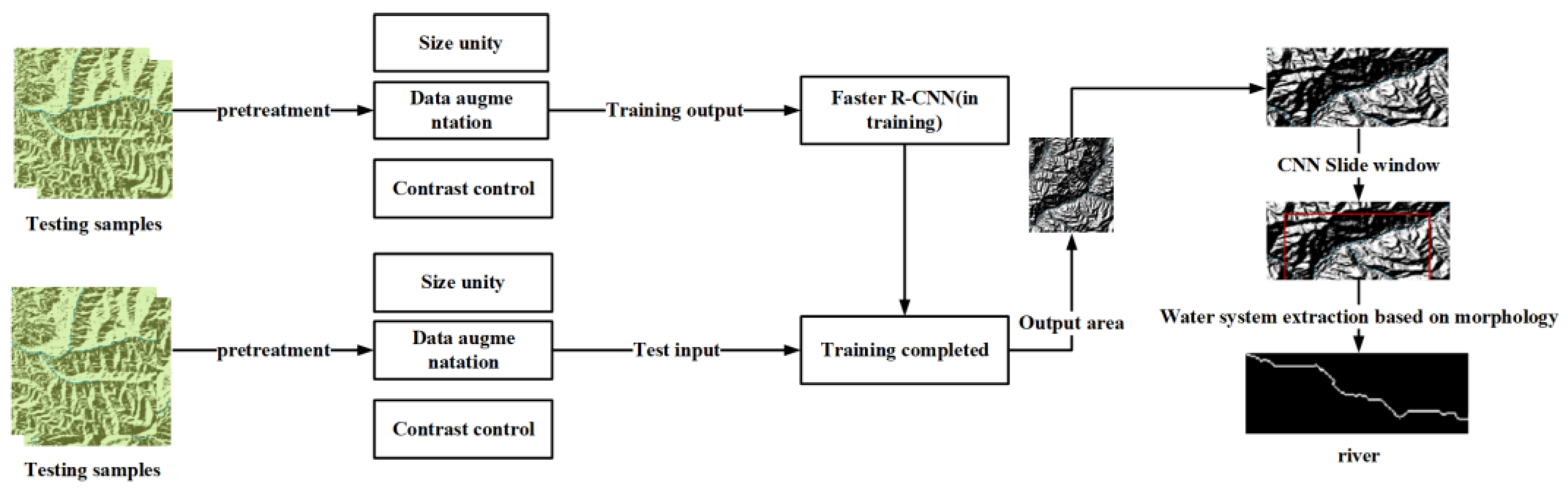

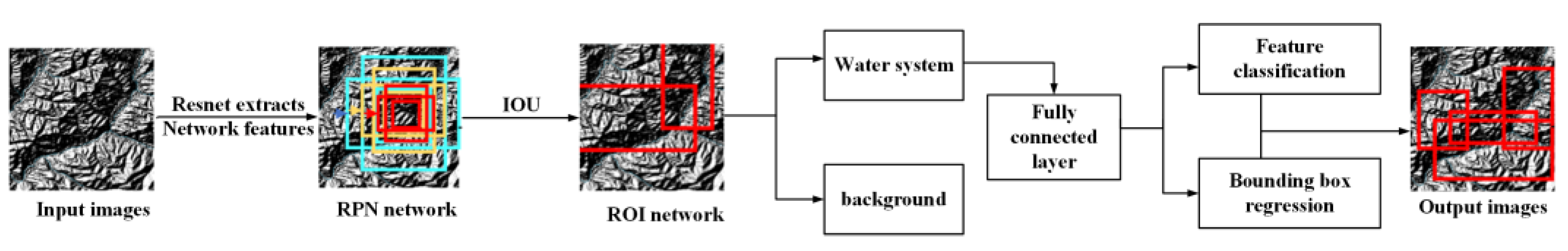

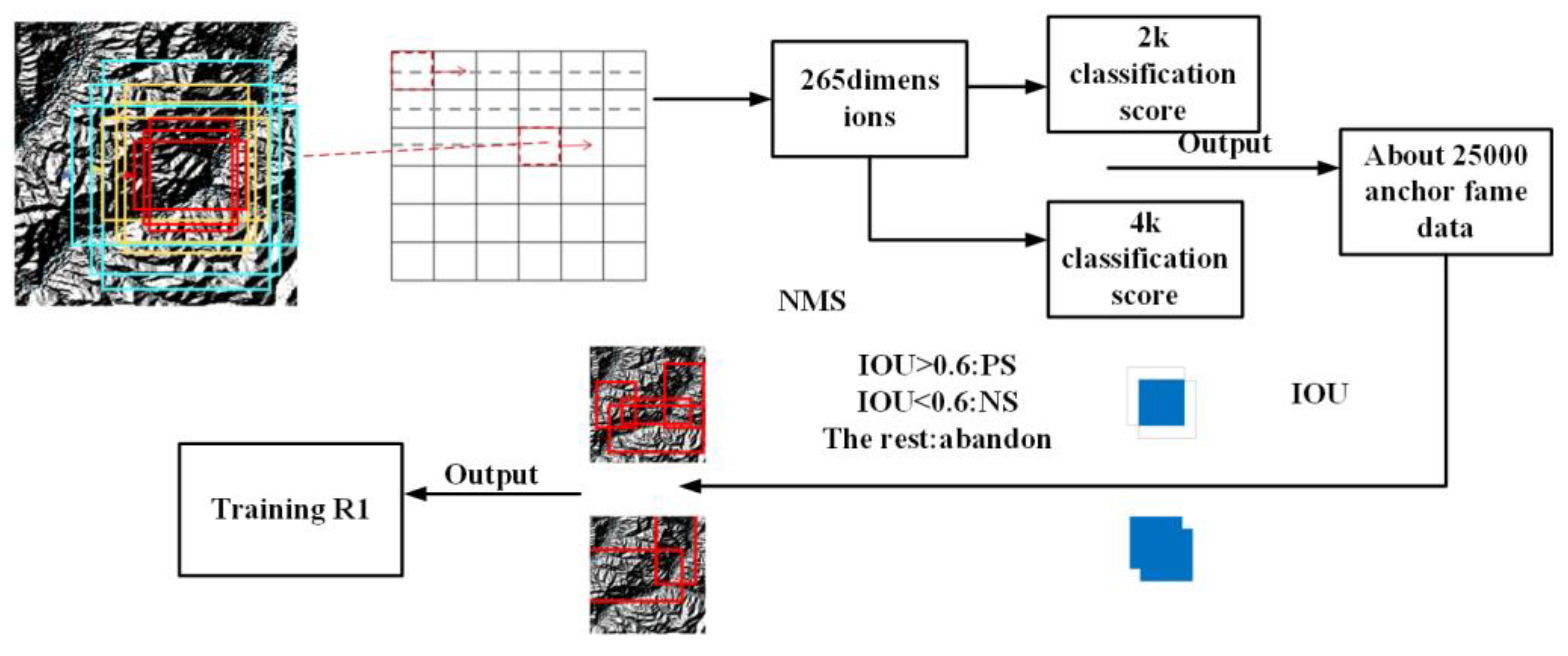

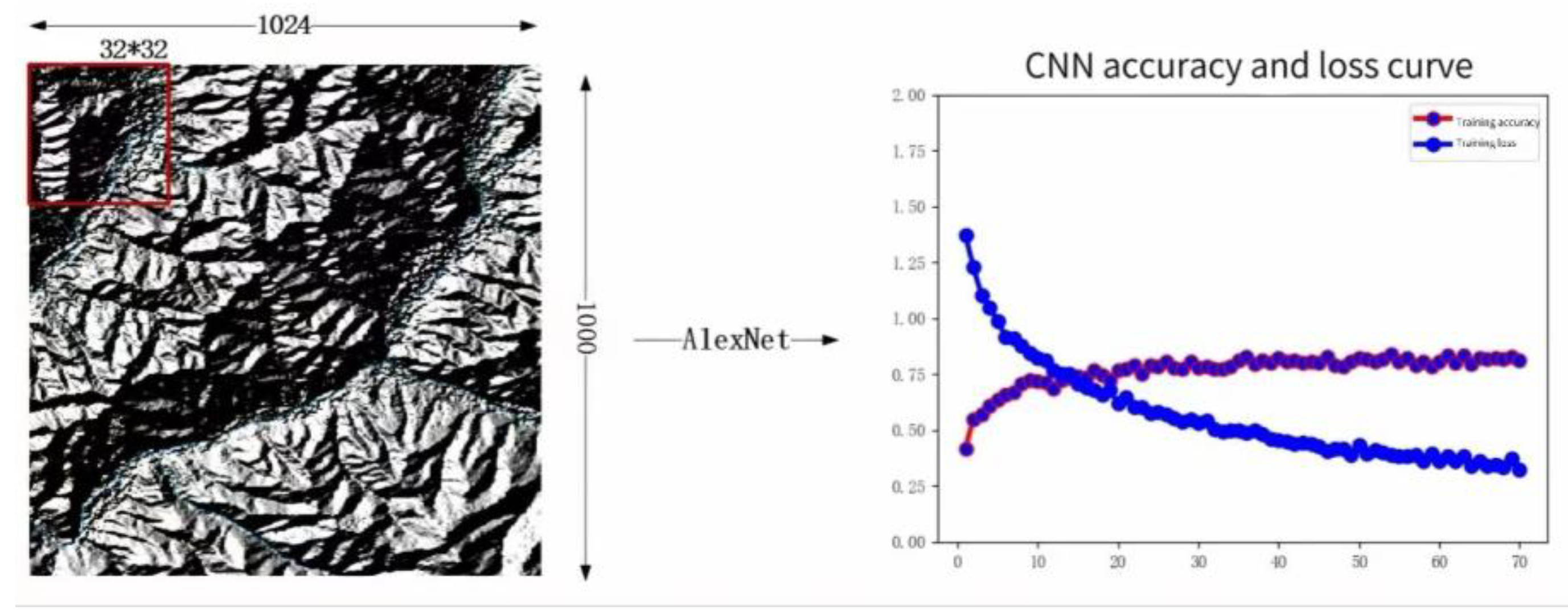

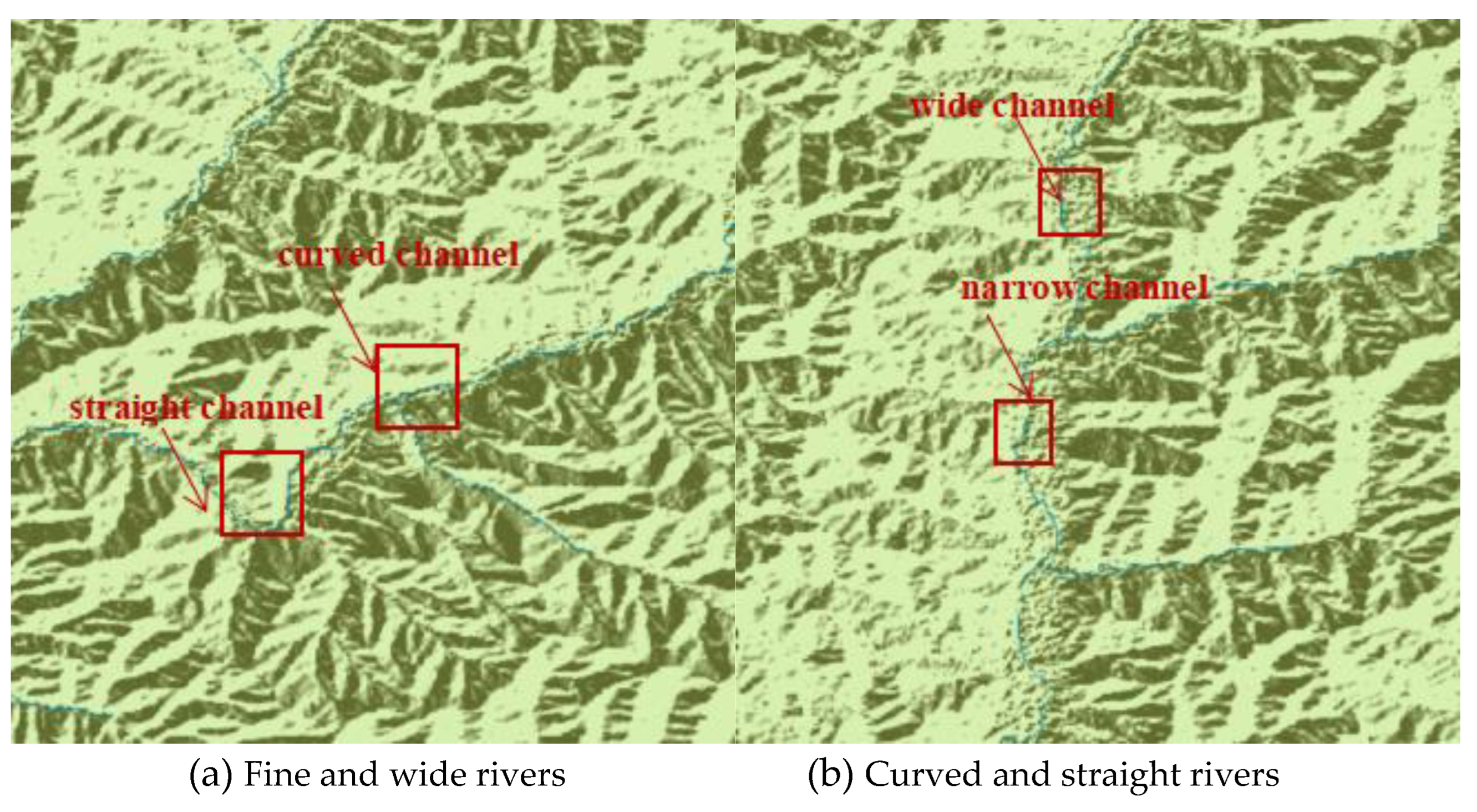

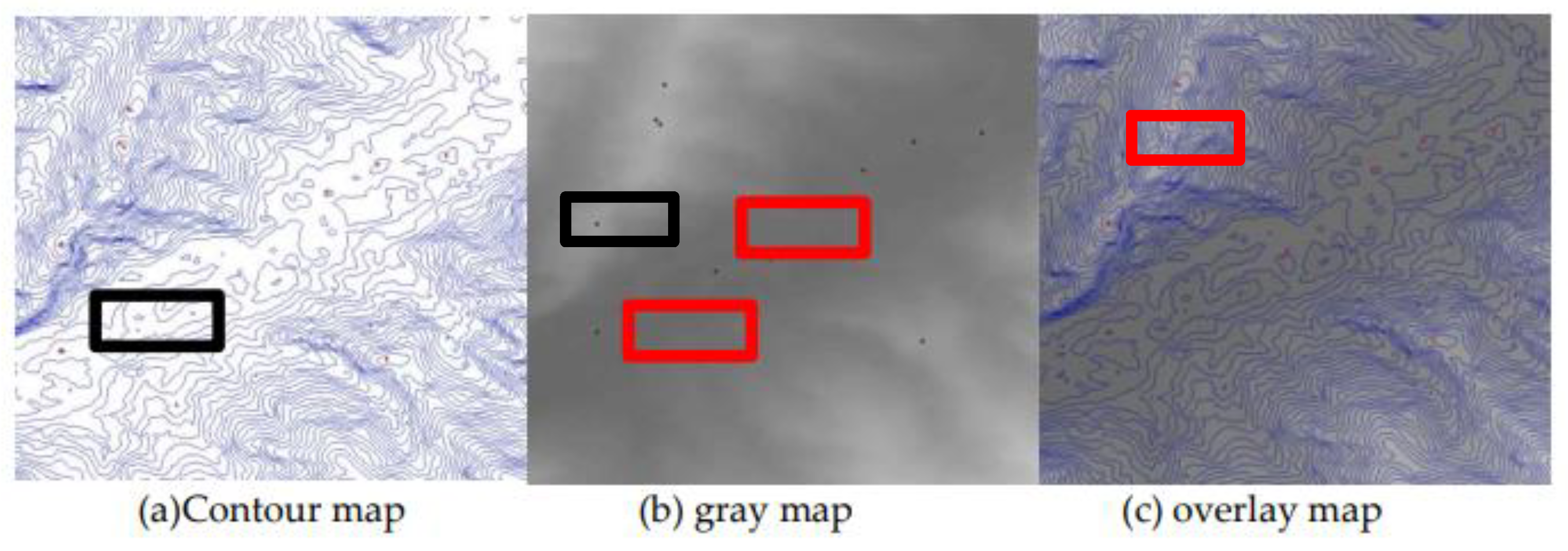

2.4. Water system Information Extraction in Chongli District Based on Faster R-CNN

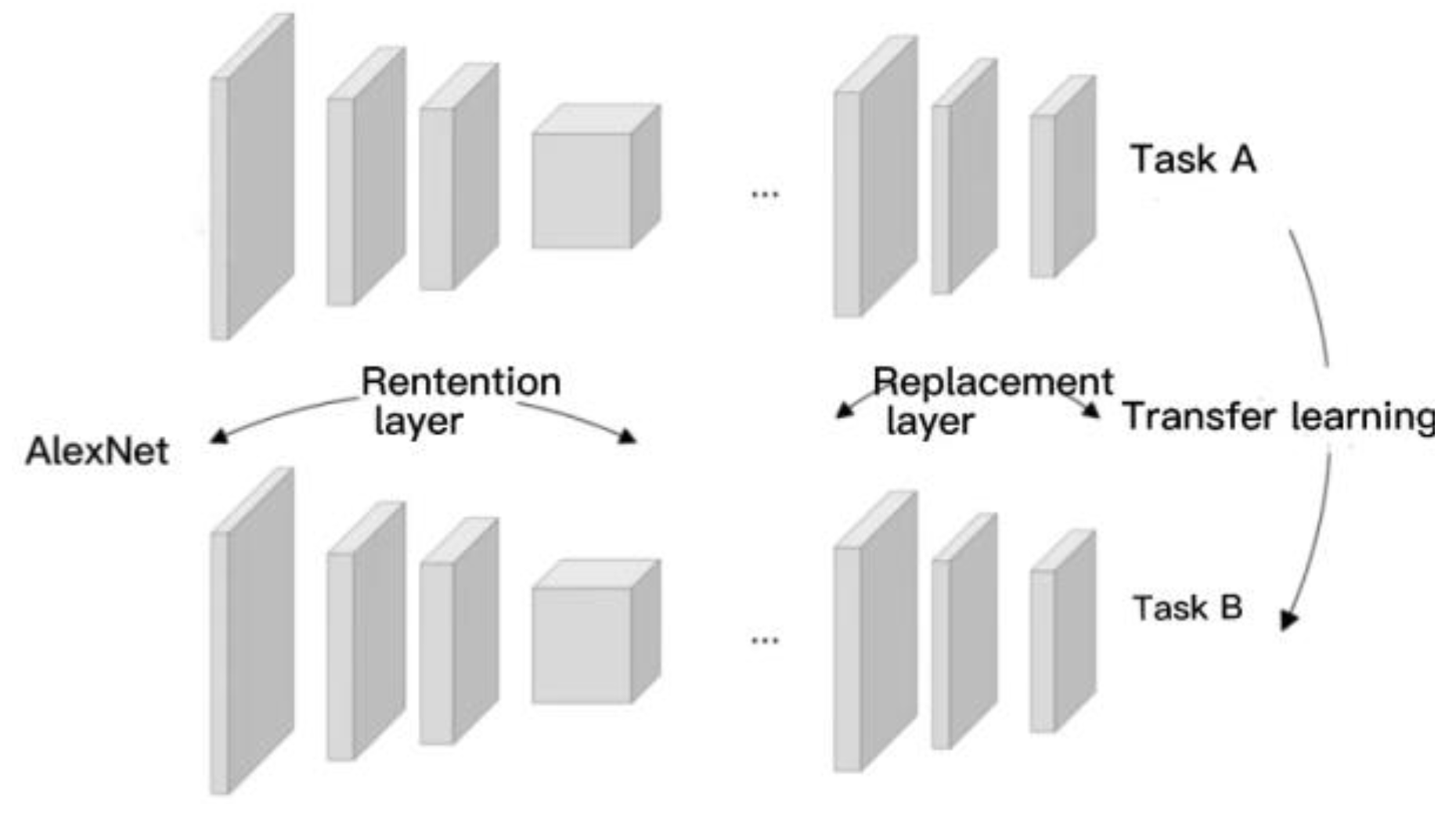

2.4.1. System Architecture

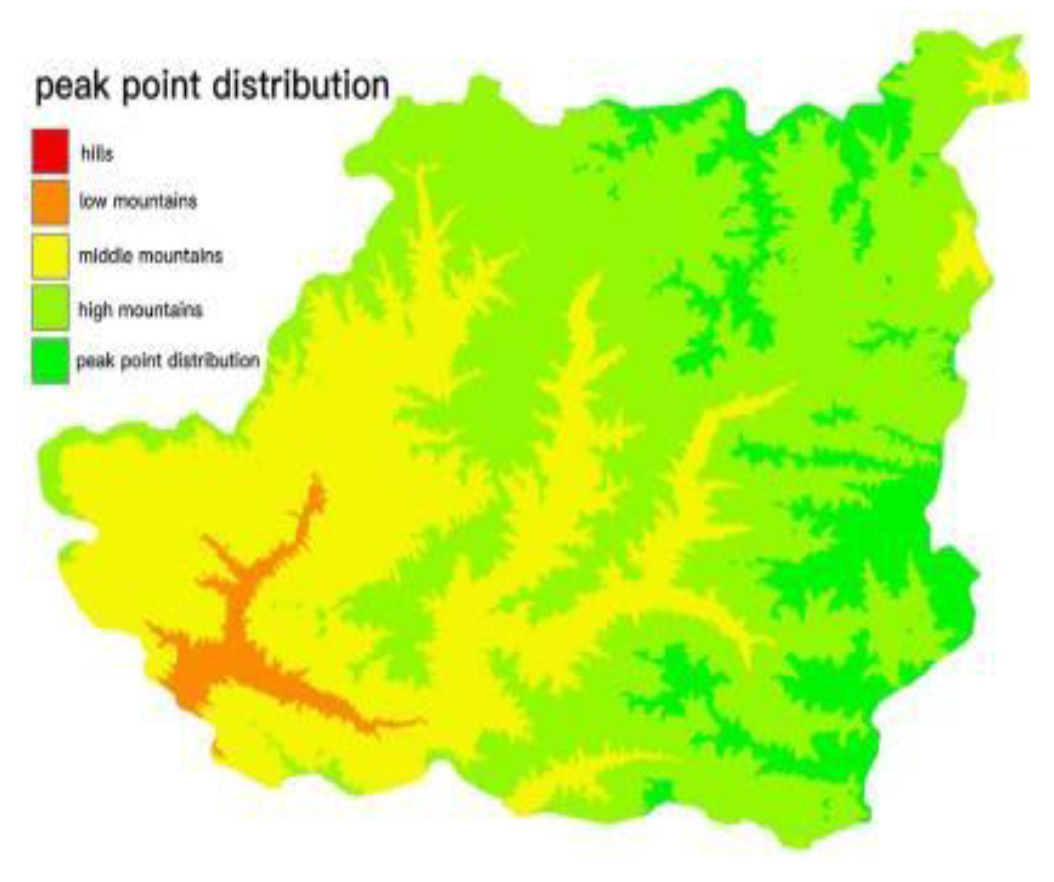

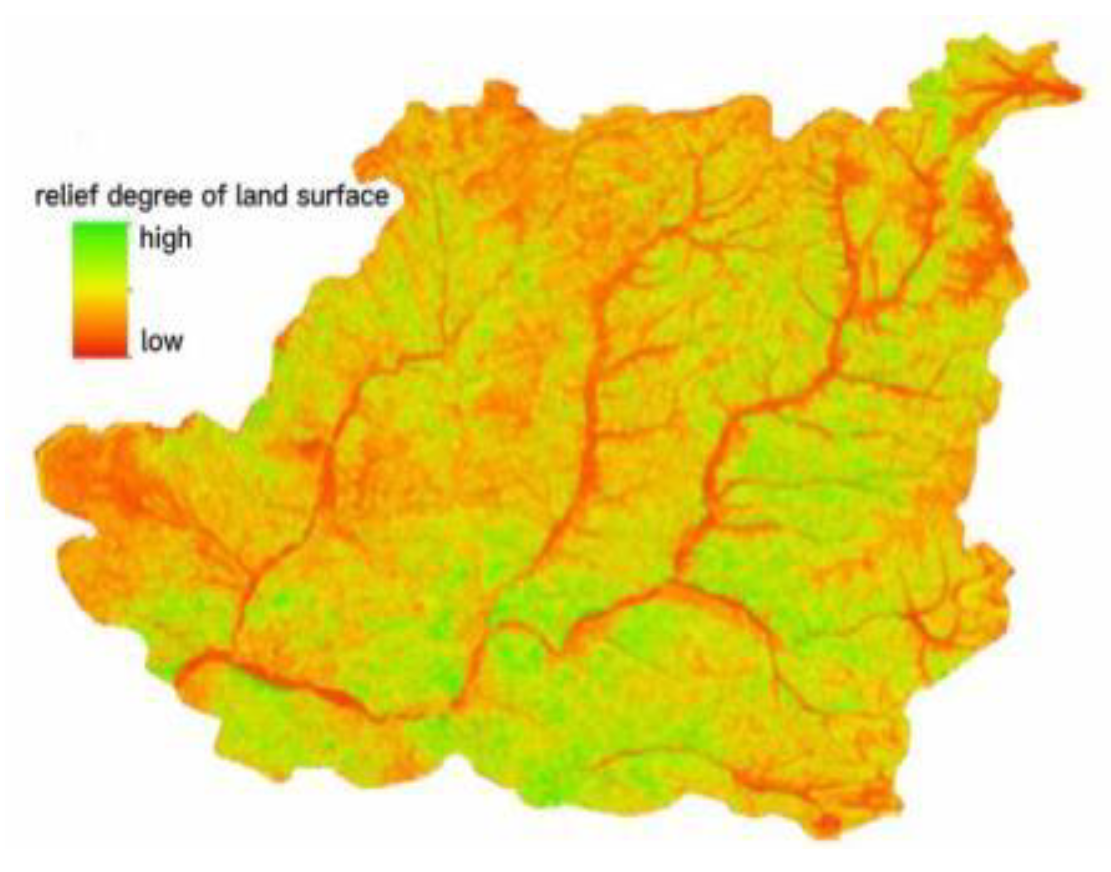

3. Results

4. Discussion

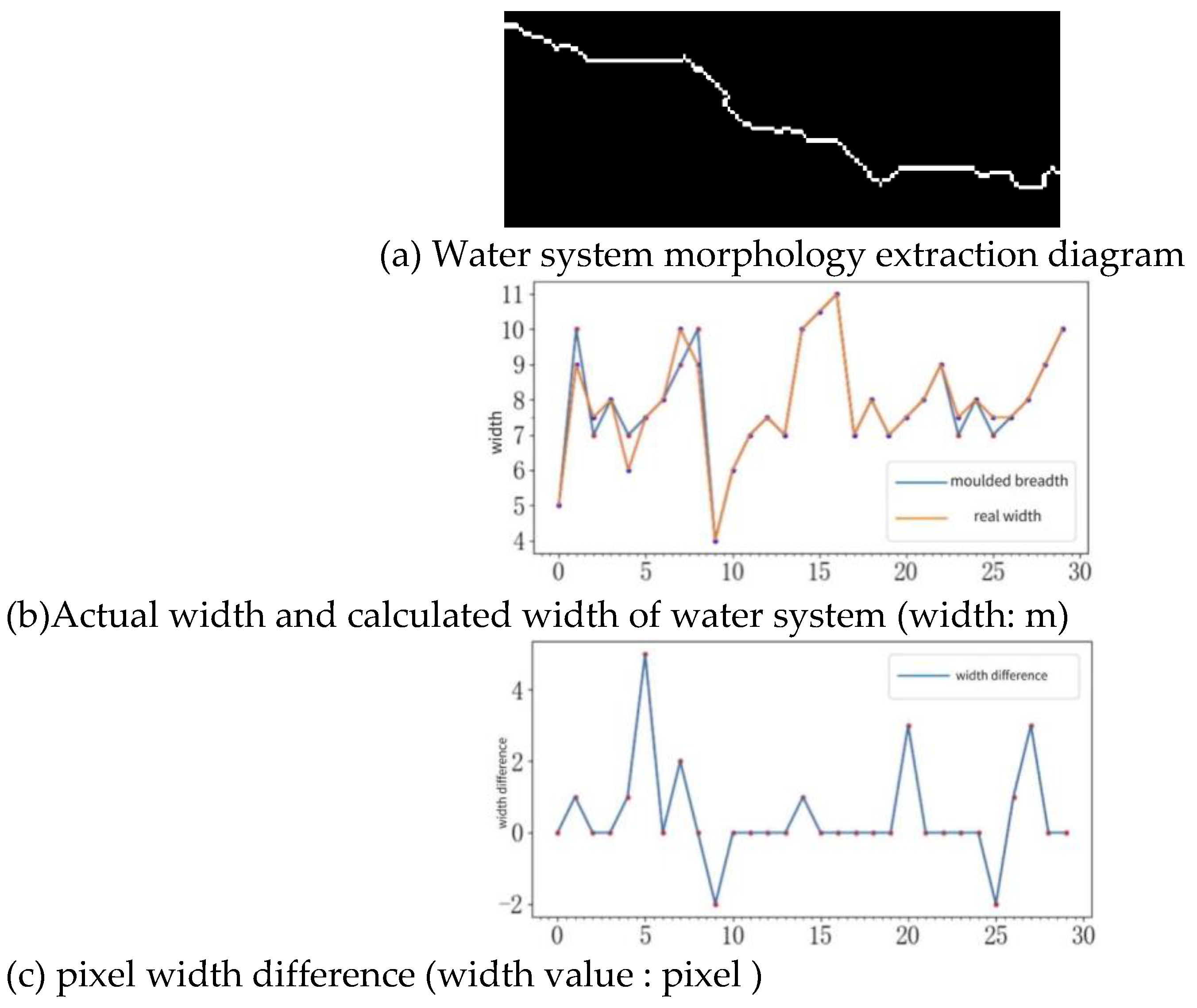

4.1. Water System Extraction and Recognition Accuracy

4.2. Mountain Top point Extraction Recognition Accuracy

5. Conclusions

References

- Shi, X.; Mao, D.; Song, K.; Xiang, H.; Li, S.; Wang, Z. Effects of landscape changes on water quality: A global meta-analysis. Water Res. 2024, 260, 121946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia, G. Combining geomorphometry, feature extraction techniques and Earth-surface processes research: The way forward. Geomorphology 2020, 355, 107055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wong, D.W. Effects of DEM sources on hydrologic applications. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2010, 34, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R. (2020). Research on the impact of landform on land use in Yuzhong County, Gansu Province [Doctoral dissertation, Lanzhou Jiaotong University].

- Lee, J. , Shuai, Y., & Zhu, Q. (2004, September). Using images combined with DEM in classifying forest vegetations. In IGARSS 2004. 2004 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (Vol. 4, pp. 2362-2364). IEEE.

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Hu, C.; Liu, H.; Cheng, Y. Deep learning of DEM image texture for landform classification in the Shandong area, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 16, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (2020). Research on observation point setting and its parallelization method based on terrain visibility [Doctoral dissertation, Nanjing Normal University].

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y. Generalization of DEM for terrain analysis using a compound method. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 2011, 66, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Luo, M.; Bai, L.; Duan, J.; Yu, B. An Integrated Algorithm for Extracting Terrain Feature-Point Clusters Based on DEM Data. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, T.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Dai, W.; Su, X.; Zhao, Y. Terrain Skeleton Construction and Analysis in Loess Plateau of Northern Shaanxi. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2022, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaze, J.; Teng, J.; Spencer, G. Impact of DEM accuracy and resolution on topographic indices. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, S.; Sfougaris, A.; Christopoulou, O. Review of Geoinformatics-Based Forest Fire Management Tools for Integrated Fire Analysis. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 5423–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Benoy, G.; Chow, T.L.; Rees, H.W.; Daigle, J.-L.; Meng, F.-R. Impacts of Accuracy and Resolution of Conventional and LiDAR Based DEMs on Parameters Used in Hydrologic Modeling. Water Resour. Manag. 2009, 24, 1363–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe A (1992) Automated recognition of valley heads from digital elevation models. 3: Earth Surf Process Landf 16.

- Garbrecht J, Martz LW (2000) Digital elevation model issues in water resources modeling. In: Maidment D, Djokic D (eds) Hydrologic and hydraulic modeling support with geographic information systems.

- Starks PJ, Garbreach JD, Schiebe FR, Salisbury JM, Waits DA (2003) Selection, development, and use of GIS coverages for the Little Washita River research watershed. In: Lyon JG (ed) GIS for water resources and watershed management.

- Callow, J. N. , Van Niel, K. P., & Boggs, G. S. (2007). How does modifying a DEM to reflect known hydrology affect subsequent terrain analysis? Journal of hydrology, 332(1-2), 30-39.

- Yang, Z. , & Wang, H. (2021). Design and implementation of an interactive terrain editing system based on multi-feature sketches. Electronic Technology and Software Engineering, (17), 47-48.

- James, A.; Hodgson, M.E.; Ghoshal, S.; Latiolais, M.M. Geomorphic change detection using historic maps and DEM differencing: The temporal dimension of geospatial analysis. Geomorphology 2012, 137, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhu, A.-X.; Wang, W.; Xiao, W.; Huang, Y.; Li, G.; Li, D.; Zhu, J. A hierarchical approach coupled with coarse DEM information for improving the efficiency and accuracy of forest mapping over very rugged terrains. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.N.C.; Ogilvie, J.; Meng, F.-R.; White, B.; Bhatti, J.S.; Arp, P.A. Modelling and mapping topographic variations in forest soils at high resolution: A case study. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 2314–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W. , Gan, S. ( 2021). Extraction and analysis of microgeomorphic features in the southern margin of Dinosaur Valley. Surveying and Mapping Bulletin, 48–54.

- Chowdhury, M. S. (2023). Modelling hydrological factors from DEM using GIS. MethodsX, 10, 102062.

- Ryzhkova, V.; Danilova, I.; Korets, M. A Gis-Based Mapping and Estimation the Current Forest Landscape State and Dynamics. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2011, 4, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Hou, Z.; Li, X.; Liang, J.; You, K.; Zhou, X. PointDMIG: a dynamic motion-informed graph neural network for 3D action recognition. Multimedia Syst. 2024, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Thiyagalingam, J.; Kirubarajan, T.; Xu, S. Speed-adaptive multi-copy routing for vehicular delay tolerant networks. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 94, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Tang, R.; Zhou, W. Delay-sensitive energy-efficient routing scheme for the Wireless Sensor Network with path-constrained mobile sink. Ad Hoc Networks 2024, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-H.; Li, J.-H.; Zhou, W.; Chen, C. Learning-Empowered Resource Allocation for Air Slicing in UAV-Assisted Cellular V2X Communications. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 17, 1008–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiao, W.; Yu, W. The Combined Strategy of Energy Replenishment and Data Collection in Heterogenous Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, PP, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Ou, L.; Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; He, T. Physical-layer CTC from BLE to Wi-Fi with IEEE 802.11ax. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, PP, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Ou, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, H. DeepSpoof: Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Spoofing Attack in Cross-Technology Multimedia Communication. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 2024, PP, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Wang, L.; Hu, B. Spectrum Efficient Communication for Heterogeneous IoT Networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 3945–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Yin, Z.; Mumtaz, S.; Li, X.; Frascolla, V.; Nallanathan, A. WiLo: Long-Range Cross-Technology Communication from Wi-Fi to LoRa. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2024, PP, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xue, Y. Total leaf area estimation based on the total grid area measured using mobile laser scanning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhu, H. Performance evaluation of 2D LiDAR SLAM algorithms in simulated orchard environments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, T.; Li, J.; Ma, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, R.; Eichhorn, M.P.; Zhang, H. Status, advancements and prospects of deep learning methods applied in forest studies. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2024, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, C.; Qian, W.; Wang, Q. RT-Deblur: real-time image deblurring for object detection. Vis. Comput. 2023, 40, 2873–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. , Lu, P., Liu, W., & Song, L. (2020). Automatic extraction of mountaintop points based on independent self-enclosed contour surfaces. Geospatial Information, 18(12), 48-50+6.

- Jiao, W.; Zhang, C. An Efficient Human Activity Recognition System Using WiFi Channel State Information. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 6687–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T. (2021). Research on automatic recognition method of geographical scenes based on ARG and spatial pattern matching [Doctoral dissertation, Nanjing Normal University].

- Sun, X. , Li, J., Zhang, R., Wang, S., Ji, X., & Li, G. (2023). Research on the relationship between reconstruction of ancient water system network and urban planning in Xiong'an based on remote sensing. Remote Sensing of Natural Resources, 35(1), 132-139.

- Qian, W.; Hu, C.; Wang, H.; Lu, L.; Shi, Z. A novel target detection and localization method in indoor environment for mobile robot based on improved YOLOv5. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 28643–28668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Hu, H.; Li, X.; Meng, Q.; Lu, H.; Huang, Q. An efficient Fusion-Purification Network for Cervical pap-smear image classification. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 251, 108199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, H.; Hou, Z.; Liang, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Xu, A. Motion focus global–local network: Combining attention mechanism with micro action features for cow behavior recognition. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Xue, Q.; Feng, J.; Bai, D. Internet of things intrusion detection model and algorithm based on cloud computing and multi-feature extraction extreme learning machine. Digit. Commun. Networks 2022, 9, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Liu, Y.; Hu, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.; He, T. Time Synchronization Based on Cross-Technology Communication for IoT Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 19753–19764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-H.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Yu, G. Stochastic Game for Resource Management in Cellular Zero-Touch Deterministic Industrial M2M Networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2022, 11, 2635–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Bai, D.; Lin, H.; Zhou, H.; Qian, J. FireViTNet: A hybrid model integrating ViT and CNNs for forest fire segmentation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| label | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 370 | 120 | 430 | 200 | 1 |

| 325 | 240 | 370 | 370 | 1 |

| 300 | 425 | 250 | 440 | 1 |

| Geomorphic type | hill | Low mountain | high mountain | Extreme mountain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undulation(m) | 20-150 | >150 | 260-600 | >2000 |

| Altitude(m) | <500 | 500-800 | 2000-3000 | >5500 |

| Geomorphic type | hill | Low mountain | middle mountain | high mountain | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average altitude(m) | <500 | 500-800 | 800-3000 | >3000 | |||

| Undulation(m) | 20-150 | <150 | ≥150 | <200 | ≥200 | <500 | ≥500 |

| Minimum elevation of peak(m) | +30 | +30 | +200 | +200 | +500 | +500 | +1000 |

| Predictive value | Authenticity | |

|---|---|---|

| positive | Negative | |

| Positive | 500 | 900 |

| TP | FP | |

| Negative | 0 | 700 |

| FN | TN | |

| Result | Contour map | Contour map | overlay map |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ri (%) | 15.41 | 7.52 | 4.25 |

| Ro (%) | 12.05 | 9.23 | 4.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).