1. Introduction

Lactobacilli are one of the most prominent groups of probiotics, widely known for their long history of consumption and their general recognition as safe for human use [

1,

2]. However, the possibility of unforeseen safety concerns cannot be entirely excluded. Factors such as the strain's growth conditions, the ingredients and methods used in the production of bacterial powder, and storage conditions may result in genetic changes, altered gene expression, and shifts in metabolic products [

3,

4]. While certain bacterial species are traditionally considered safe, the use of non-traditional delivery formats and increased dosages can introduce potential safety risks. Additionally, some strains, although deemed safe, originate from environments such as human or animal feces, raising questions about their safety under these circumstances [

4].

A report by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the importance of safety considerations for probiotic strains [

5]. According to the report, probiotics can pose four potential adverse effects: systemic infections, harmful metabolic activities, excessive immune stimulation in susceptible individuals, and gene transfer [

6]. The FAO/WHO working group recommends several tests for probiotic safety confirmation: (1) determination of antibiotic resistance patterns; (2) assessment of specific metabolic activities, such as D-lactate production and bile salt deconjugation; (3) monitoring side effects during human studies; (4) epidemiological surveillance of adverse incidents in consumers; and (5) testing for toxin production, especially if the strain is known to produce mammalian toxins. If the strain belongs to a species with known hemolytic potential, hemolytic activity must also be assessed.

Various regulatory bodies have published lists of microorganisms approved for use in food, with the Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) list from European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) being one of the most well-known. First released in 2007, the QPS list is regularly reviewed and updated by expert committees and includes microorganisms considered safe for consumption or use in food additive production (

https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/qualified-presumption-safety-qps). EFSA guidelines provide specific standards for microbial analysis, including the quality and methods for whole genome sequencing (WGS), offering a standardized approach to safety assessments [

7]. This emphasizes the crucial role of microbial identification in evaluating safety. Recent advancements in microbial classification methods have enhanced the precision and consistency of taxonomic identification [

8], leading to more reliable safety assessments.

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp.

paracasei (formerly

Lactobacillus paracasei subsp.

paracasei) NTU 101, isolated from human feces, exhibits strong acid and bile tolerance [

9]. Previous studies have demonstrated its various probiotic benefits, including improvements in gut health [

10], metabolic function [

11,

12,

13], and immune modulation [

14]. NTU 101 has been shown to exert anti-obesity effects in obese rats by modulating the gut microbiota, fatty acid oxidation, lipolysis, and adipogenesis [

15]. It also helps alleviate allergic reactions associated with atopic dermatitis, thereby preventing its onset [

16]. Clinical trials have revealed that daily intake of NTU 101 enhances intestinal peristalsis, immunity, and antioxidant capacity [

17]. NTU 101 may promote peristalsis through the purinergic pathway, potentially preventing constipation-related irritable bowel syndrome [

18].

As a species included in the QPS list,

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei has already demonstrated sufficient safety. In previous studies, NTU 101 has passed multiple safety tests, including the bacterial reverse mutation test, cell chromosomal aberration test, rodent peripheral blood micronucleus test, and a 28-day oral toxicity assay [

19]. The objective of this study is to follow the WHO/FAO safety assessment criteria and EFSA guidelines [

7,

20], using integrated phenotypic and genotypic analyses to confirm the safety of NTU 101 at the strain level. Building on the results of the 28-day oral toxicity assay, a repeat-dose 90-day oral toxicity study was conducted to further assess the long-term safety of NTU 101 under dietary exposure. This study aimed to evaluate the safety of NTU 101 when consumed over an extended period at various intake levels, helping to establish the range and flexibility of its use as a food ingredient.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

NTU 101 is stored long-term in glycerol cryotubes at -80°C. The strain was also deposited in the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ) under accession number 28047. For strain activation, the cryopreserved cells are streaked on De Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) (BD Difco, USA) agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 48-72 hours. The reference strains used in the hemolysis activity assay and mucin degradation activity were purchased from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center (BCRC) in Hsinchu, Taiwan. These strains include L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 17002, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 12248T, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 14023, and L. rhamnosus BCRC 16000. These strains are preserved and activated in the same manner as NTU 101.

2.2. Taxonomic Identification Through Phenotypic and Genotypic Analysis

For phenotypic identification, Gram staining was initially performed to determine the Gram stain type of the strain. The microscopic morphology of the colonies was then examined to assess their appearance. Additionally, the API 50 CHL Identification System (Biomérieux, France) was employed for phenotypic characterization. In terms of genotypic identification, performed according to the standards outlined by Resico and Trujillo (2024) [

8], the 16S rDNA sequence obtained through Sanger sequencing was used to assess sequence similarity for strain identification.

For WGS, genomic DNA from NTU 101 was extracted using overnight-cultured liquid samples. The extraction was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the Quick-DNA™ Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, USA). The whole genome sequencing was performed using a MinION Mk1B device (Oxford Nanopore, U.K.) with an R9.4.1 flow cell (FLO-MIN106D), and Nanopore sequencing reagents were used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Library preparation was carried out using KAPA Hyper Prep (Roche, Switzerland) and KAPA HyperPure Beads (Roche, Switzerland). The sequencing data processing and assembly were performed according to the procedures described in Murigneux et al. (2021) [

21], with further polishing of the assembly using Homopolish (

https://github.com/ythuang0522/homopolish).

Genome completeness was assessed using CheckM (v0.9.7). To confirm the genetic taxonomy, the average nucleotide identity (ANI) was calculated using the PGAP. Additionally, digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) was assessed using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) implemented in the Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS,

https://tygs.dsmz.de/) to determine the genomic similarity of the strain.

2.3. Gene Prediction and Annotation

Gene prediction and annotation for NTU 101 were performed using the Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) (version 6.7, 2024-07-18.build7555), with default command-line parameters. The classification of protein clusters of orthologous groups (COGs) was conducted using COGclassifier (v1.0.5,

https://github.com/moshi4/COGclassifier), which analyzed the PGAP-annotated protein sequences with default parameters. The analysis utilized a reverse position-specific Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) search against the NCBI conserved domain database (2020 update). Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes Database (CAZy,

http://www.cazy.org/) gene annotation was performed using the dbCAN server (HMMdb v12) (

https://bcb.unl.edu/dbCAN2/). Annotation of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was conducted using the hidden Markov model (HMM) profile (ver. 2024-05-01, KEGG release 110.0) and analyzed with KofamKOALA server (

https://www.genome.jp/tools/kofamkoala/), which utilizes the kofamScan 1.3.0 tool.

The detection of mobile genetic elements was performed using MobileElementFinder (

https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/MobileElementFinder/) to assess the potential for horizontal gene transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors. For virulence factor analysis, protein sequences from the full dataset of the Virulence Factor Database were downloaded (version 26-07-2024,

http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/download.htm). The searching algorithm of BLAST version 2.16.0+, including BLASTn, BLASTp and BLASTx was used to search the protein sequences of NTU 101 annotated by PGAP and annotation tools to identify potential pathogenic and virulence factor genes.

2.4. Antibiotic Susceptibility Assay and Resistance Genes Prediction

The phenotypic analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility was performed according to the EFSA guidelines to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC). The MIC values were tested and compared with the EFSA cut-off value for Lacticaseibacillus paracasei to determine susceptibility.

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) were screened using the following databases and tools. The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) version 3.2.9 (

https://card.mcmaster.ca/home) was used, employing the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) version 6.0.3 to analyze the NTU 101 WGS data. For additional screening, ResFinder version 4.5.0 (

http://genepi.food.dtu.dk/resfinder) was used with specific analysis conditions. AMRFinderPlus version 3.12.8 (

https://github.com/ncbi/amr) was used to analyze the NTU 101 protein sequences annotated by PGAP, following the usage instructions provided.

2.5. Analysis of Biogenic Amine

The analysis of biogenic amines (BA) in fermentation broths was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The conditions and gradient for HPLC were adapted from the methods described by Sang et al. (2020) [

22] and Ma et al. (2021) [

23]. The biogenic amines analyzed, including putrescine, cadaverine, tryptamine, histamine, tyramine, spermidine, and spermine, were purchased from Dr. Ehrenstorfer (Germany), while 2-phenylethylamine was obtained from Sigma (USA). For the detection of these biogenic amines, dansyl chloride (ACROS, Belgium) derivatization was performed, following the method described by Eerola et al. (1993) [

24]. This derivatization process was applied to standard BA samples as well as to BAs present in three types of fermentation media, including MRS broth, milk, and soymilk, all fermented by NTU 101.

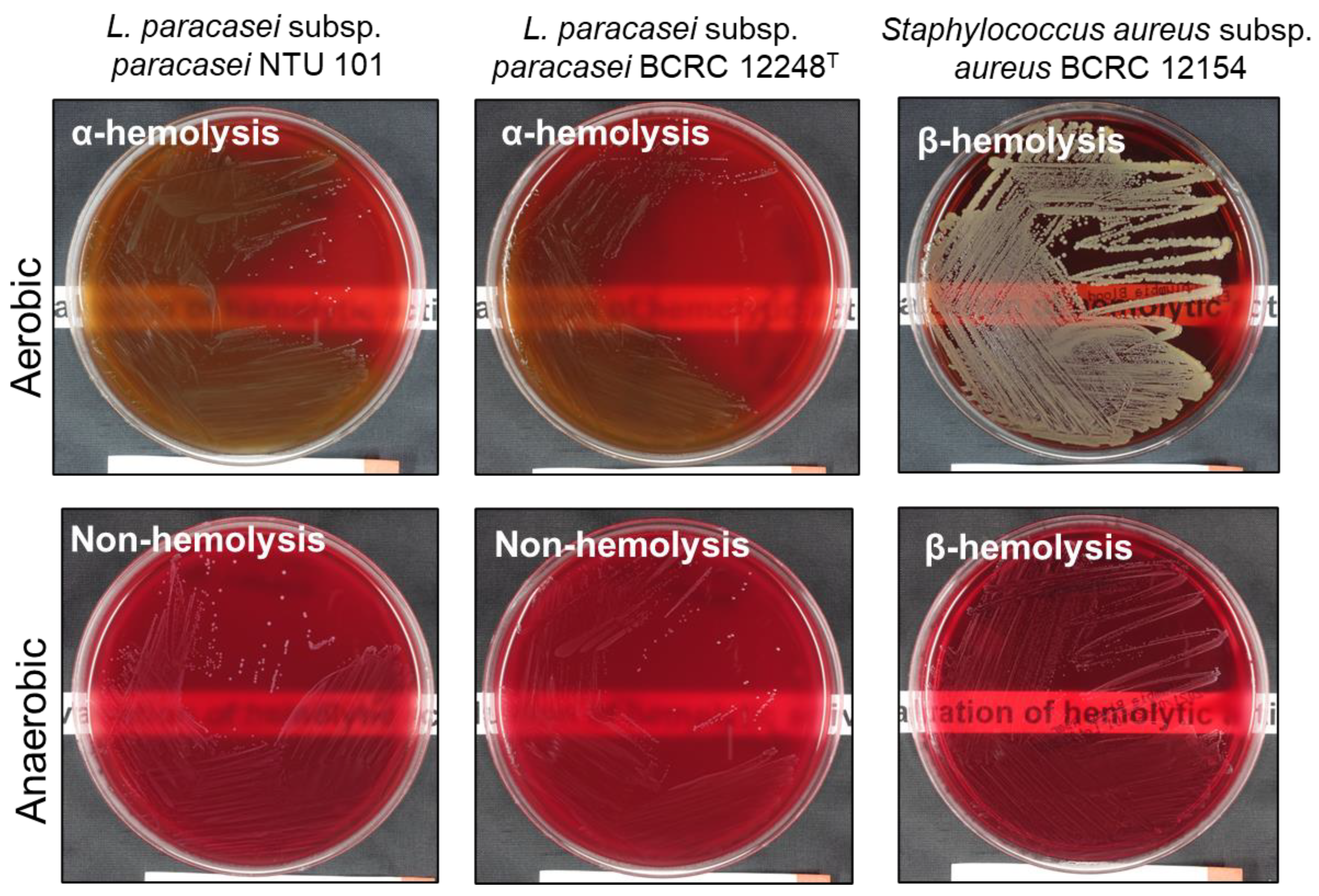

2.6. Hemolytic Activity Assay

Following the methods described by Casarotti et al. (2017) [

25], activated NTU 101, reference lactic acid bacteria strains, and the positive control strain

S. aureus BCRC 12154 were cultured. The bacterial suspensions were inoculated onto CMP

TM Columbia Agar (BD Difco, USA) with 5% defibrinated sheep blood using a four-quadrant streaking method. The plates were incubated at 37°C under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions for 48 hours. After incubation, the appearance of the colonies and the surrounding areas on the plates were observed. According to the standards set by Buxton (2005) [

26], α-hemolysis was indicated by a green or brown discoloration around the colonies, β-hemolysis was indicated by a clear zone surrounding the colonies, and γ-hemolysis was indicated by no change in the coloration around the colonies.

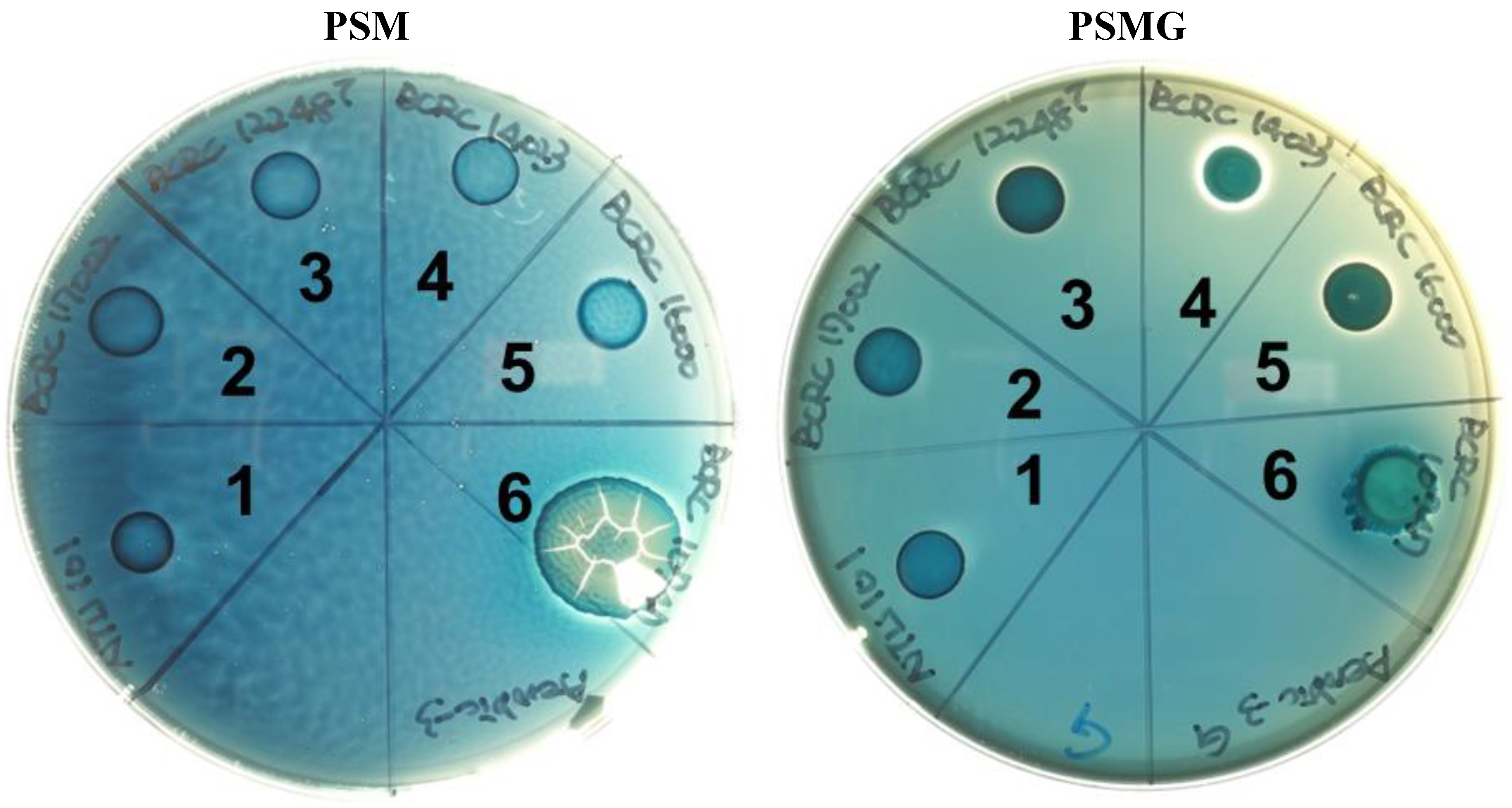

2.7. Mucin Degradation Activity

Following the methods described by Zhou et al. (2001) [

27], type III mucin from porcine stomach (PSM) (Sigma, USA) was pretreated. Two types of agar plates were prepared: 0.5% w/v PSM with or without 3% w/v glucose, referred to as PSMG and PSM agar, respectively, according to the formulation by Zhou et al. (2001). Activated NTU 101, reference lactic acid bacteria strains, and the positive control strain

S. enterica subsp.

enterica BCRC 10747 were each cultured in liquid form. A 10 µL drop of each bacterial suspension was placed in the six quadrants of the pre-prepared PSMG and PSM agar plates. The plates were then incubated at 37°C under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions for 72 hours. After incubation, the plates were stained for 30 minutes with 0.1% w/v amido black (Sigma, USA) dissolved in 3.5 M acetic acid and subsequently washed with 1.2 M acetic acid. Colonies that turned deep blue after staining and exhibited a clear zone around them were considered positive for mucin degradation activity. If no colony growth was observed and the surrounding area remained light blue after staining, the result was classified as negative for mucin degradation activity.

2.8. Translocation on Intestinal Epithelial Cells

In this study, we examined whether NTU 101 bacterial powder can translocate across a monolayer of intestinal epithelial cells under conditions of barrier dysfunction induced by hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), following the approach described by Fatmawati et al. (2020) [

28]. C2BBel BCRC 60182 cells, a clone of human colon adenocarcinoma cells (Caco-2, ATCC HTB-37), were seeded into transwell apical chambers (8.0 μm pore size) at a density of 4 × 10

4 cells per well, and cultured with Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum and 0.01 mg/mL holo-transferrin (Sigma, USA).

We used a Millicell ERS-2 voltohmmeter (Millipore, Germany) to monitor transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) values throughout the culture period. When the TEER value exceeded 300 Ω × cm², the monolayer was deemed suitable for use in experiments. H2O2 was used to induce intestinal barrier dysfunction by co-incubating for 2 to 3 hours. Then NTU 101 bacterial suspensions (108 CFU/mL) were added to both untreated cells and cells with H2O2-induced dysfunction for 1 hour. Following incubation, the cell culture medium was centrifuged at 8,000-10,000 g, and an aliquot was plated on MRS agar. Colony growth of NTU 101 was assessed visually after 48 to 72 hours of incubation. The absence of colony growth indicated that bacterial translocation did not occur under conditions of normal epithelial barrier function.

2.9. D/L-Lactic Acid Production

Activated NTU 101 was subcultured at a 1% (v/v) concentration into sterilized MRS liquid medium in test tubes. The cultures were incubated at 37°C under anaerobic conditions for 24 hours. For lactic acid analysis, fermentation samples were prepared according to the method described by Kim et al. (2022) [

29]. After incubation, the fermentation broth was centrifuged at 5000 × g and 4°C for 10 minutes to obtain the supernatant. The supernatant was then filtered through a 0.22 μm filter to obtain the filtrate for subsequent analysis. The concentrations of D- and L-lactic acids were measured using the D-Lactic Acid (D-lactate) (Rapid) Kit and L-Lactic Acid (L-Lactate) Assay Kit (Megazyme, Ireland) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

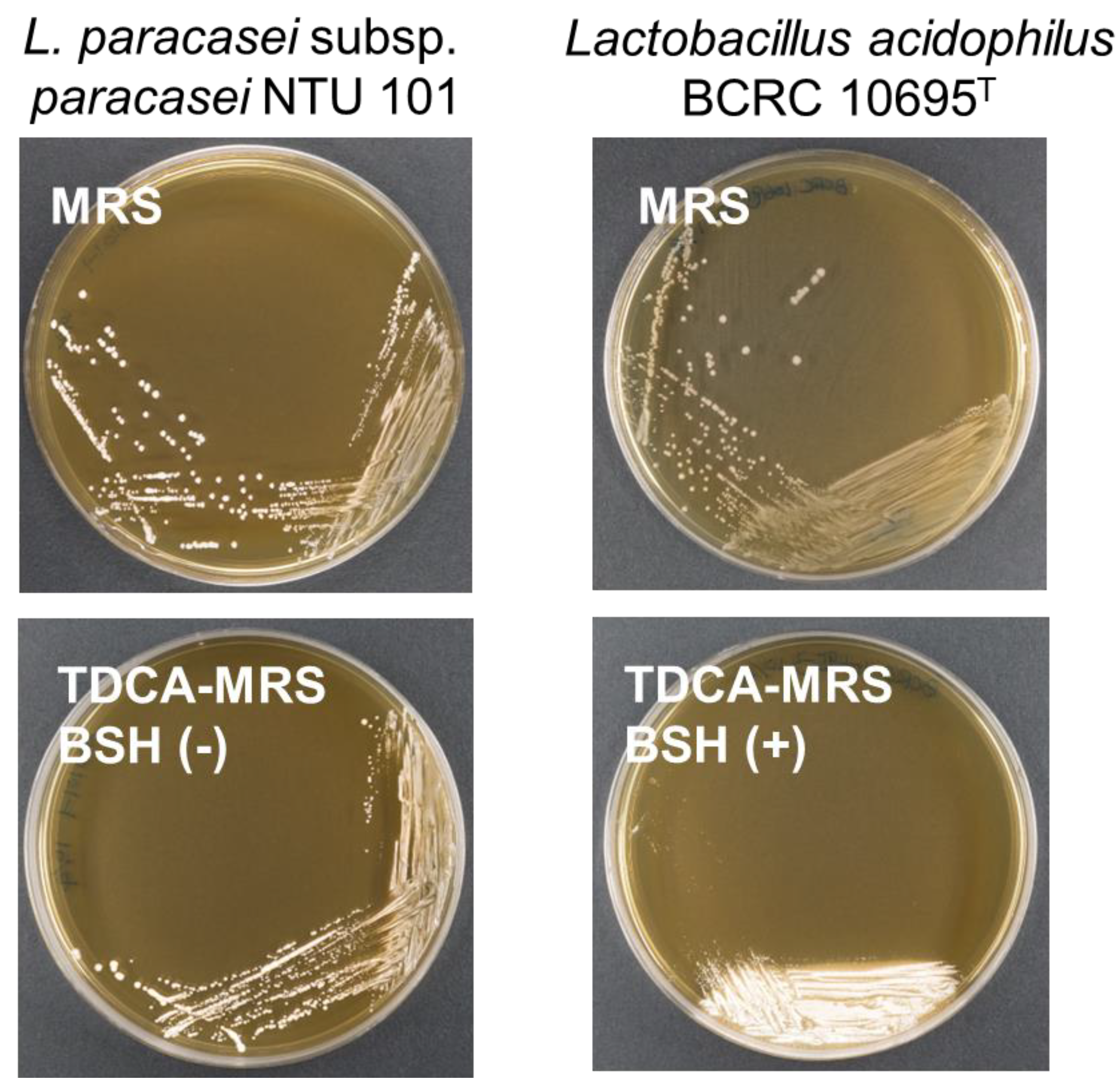

2.10. Bile Salt Hydrolase Activity

The bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity was assessed using the method described by Dashkevicz and Feighner (1989) [

30]. Activated NTU 101 and the positive control strain

L. acidophilus BCRC 10695

T were streaked onto MRS agar plates and MRS agar plates containing 0.5% (w/v) taurodeoxycholic acid (TDCA) (Sigma, USA). The plates were incubated at 37°C under anaerobic conditions for 48 hours. After incubation, the colonies and the surrounding areas were observed. A positive BSH activity was indicated by the presence of a white precipitate either on the colonies or in the surrounding area. If no color changes or colonies formation were observed, the result was classified as negative for BSH activity.

2.11. Repeated Dose 90-Day Oral Toxicity Study in Rats

A repeated dose 90-day oral toxicity study was conducted in compliance with Good Laboratory Practice for Nonclinical Laboratory Studies (21 CFR Part 58), FDA, USA, 1987; OECD Principles on Good Laboratory Practice, ENV/MC/CHEM (98) 17, 1998 and General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories (ISO/IEC 17025), International Organization for Standardization, 2005. All procedures involving animal handling were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Super Laboratory Co., Ltd. (New Taipei City, Taiwan) under approval number 105-91.

The test article used in this study was NTU 101 powder (brand name: Vigiis 101-LAB, containing 100 billion bacteria of NTU 101). Forty male and forty female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were obtained from BioLASCO Taiwan Co., Ltd (Taipei, Taiwan), and were subjected to 12 hours light/dark cycle with a maintained relative humidity of 55 ± 15% and a temperature 22 ± 3°C. Feed (MFG; Oriental Yeast Co., Tokyo, Japan) and sterile reverse osmosis (RO) water provide with water bottle. The test article was administered to the low, medium and high dose groups in a dose of 500 mg/kg B.W., 1000 mg/kg B.W. and 2000 mg/kg B.W., which were 30, 60 and 120-fold the human recommended daily intake (1000 mg/60 kg B.W.), respectively. There were ten male and ten female SD rats in each group. The test article was weighted daily, dissolved in adequate amount of reverse osmosis water and mixed evenly.

All analyses and records were conducted in accordance with the previously mentioned guidelines and standards, including daily clinical observations to monitor morbidity and mortality signs in all rats. Body weight was measured weekly, and food consumption was also recorded weekly. Hematology, clinical biochemistry, pathology, gross necropsy, and histopathology were performed following the procedures and parameters outlined in these guidelines and standards. Blood, urine, and organ samples were collected for analysis and data recording. For clinical chemistry analysis, blood samples were analyzed using an automated analyzer (7070 Autoanalyzer, Hitachi, Japan). For urinalysis, the collected urine samples were analyzed using a compact urine analyzer (PU-4010, ARKRAY Core Laboratory, Japan). For histopathological examination, the fixed organs of control group and high dose group were subjected to tissue section for histopathological examination. These fixed organs were dehydrated, clarified, infiltrated with paraffin and embedded after trimming, forming paraffin tissue blocks, being cut into 2-μm thickness of a tissue slice using paraffin tissue slicing machine (Leica, Germany), stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E). If the test article treatment-related changes were observed in particular organ or tissue in high dose group, then the examination should be extended to the organ or tissues of medium dose group and low dose group.

For 90-day oral toxicity study, all data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (S.D.). The SPSS statistical software was used for the analysis. The body weight, feed intake, organ weight, hematology and clinical biochemistry analysis were carried out using One-Way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test to determine the significant difference between the treatment and control group. A significant difference was defined as a p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. WGS, Taxonomic Identification and Annotation Results

Phenotypic identification of NTU 101 revealed it to be rod-shaped under microscopic observation and classified as a Gram-positive bacterium (

Figure S1). Strain identification, based on carbon fermentation characteristics using API 50 CHL, confirmed it as

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp.

paracasei (

Table S1). Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rDNA sequence from NTU 101 showed that its closest relatives were

L. paracasei R094

T,

L. paracasei NBRC 15889

T,

L. paracasei subsp.

tolerans NBRC 15906

T,

L. chiayiensis BCRC 81062

T,

L. zeae RIA 482

T, and

L. casei DSM 20011

T, all with sequence similarities greater than 99%, a common threshold for species delineation.

The complete genome sequence of NTU 101 has been submitted to the NCBI GenBank under accession number GCA_002901165.3 and is summarized in

Table S2. This sequence was compared to the genome of

L. paracasei subsp.

paracasei JCM 8130, the type strain of

L. paracasei subsp.

paracasei. The NTU 101 genome is 3,061,587 base pairs (bp) in length with a GC content of 46.5%, consisting of a single circular chromosome of 3,010,957 bp and a plasmid of 50,630 bp. Gene annotation using PGAP revealed 2,956 genes, including 2,879 coding DNA sequences (CDS). In the analysis of COGs, 82.18% (2,287 out of 2,783) of the sequences were classified into COG functional categories, with the highest number of genes associated with category G (carbohydrate transport and metabolism) (

Figure S2).

To assess the quality of genome sequencing and assembly, we used CheckM, a standard tool for evaluating microbial genome completeness and contamination [

31]. A genome completeness greater than 90% and contamination below 5% are considered thresholds for high-quality genomes [

31,

32]. The NTU 101 genome met these criteria, with a CheckM completeness of 91.88% and contamination of 4.13%, comparable to the JCM 8130 genome.

The average nucleotide identity (ANI) between NTU 101 and JCM 8130 was calculated using PGAP's built-in ANI tool, resulting in a similarity of 98.682%. Additionally, results from the TYGS analysis yielded a digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) value of 88.2% similarity with JCM 8130, using the

d4 formula (formula 2 in GGDC). Both values exceed the accepted species boundaries of ANI greater than 95–96% and dDDH above 70% [

8,

33,

34]. Based on these findings, NTU 101 is confirmed to belong to the species

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp.

paracasei.

3.2. Antibiotic Resistance

The results of the MIC and genotypic analysis for NTU 101 are presented in

Table 1. With the exception of chloramphenicol, all MIC values were below the cut-off limits established by EFSA for

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei species [

20]. These findings are consistent with the MIC results for BCRC 12248

T (

Table 1) and align with previous reports in the literature [

35,

36]. According to EFSA guidelines, when a strain exhibits antibiotic resistance, it is essential to identify the genetic determinants of this resistance to rule out the possibility of acquired resistance [

37].

To analyze potential antibiotic resistance genes, we compared NTU 101 against three continuously updated databases. A search using RGI against the CARD database identified a "Strict" hit, which detect previously unknown variants of known antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [

38] for the

qacJ gene, which showed 38% sequence identity, well below the EFSA threshold of 80%. Further analysis using BLASTp in the NCBI RefSeq protein database confirmed that

qacJ encodes a multidrug efflux pump from the SMR transporter family, specifically associated with the EmrE conserved domain. Previous studies have shown that the EmrE transporter in

Escherichia coli does not confer resistance to chloramphenicol [

39]. Additionally, this gene was detected in other

Lacticaseibacillus species within the BLASTp results (data not shown), suggesting that the EmrE-encoding gene is likely intrinsic to

Lacticaseibacillus and is unlikely to be transferable.

Moreover, we identified 284 "Loose" hits, which detect distant homologs of ARGs or emerging threats [

38], but none were considered potential risk genes after filtering for an 80% identity threshold. We also used ResFinder and AMRfinderPlus to detect acquired antimicrobial and disinfectant resistance genes, with neither method detecting any resistance genes. Additionally, analysis using MobileElementFinder revealed no mobile genetic elements carrying resistance genes. Based on these analyses, NTU 101 can be considered safe with respect to antibiotic resistance.

3.3. Biogenic Amine

We next analyzed the biogenic amine content in the fermentation broth of NTU 101 cultivated in MRS medium, milk, and soymilk using HPLC. The results revealed a noticeable increase in biogenic amine levels. In the MRS medium, cadaverine was detected at 4.18 ppm. During milk fermentation, putrescine (4.54 ppm), cadaverine (2.85 ppm), 2-phenylethylamine (3.79 ppm), and spermine (22.47 ppm) were identified. In contrast, soymilk fermentation produced histamine (2.44 ppm) and tyramine (12.73 ppm) (

Table 2).

Biogenic amines are primarily formed by bacterial decarboxylation of amino acids, a process catalyzed by decarboxylase [

40]. To investigate this further, we analyzed the NTU 101 protein sequences using the KofamKOALA gene function annotation tool available on the KEGG website. The results, presented in

Table 3, showed no genes encoding histidine decarboxylase or tyrosine decarboxylase, which are responsible for histamine and tyramine production, respectively, in the NTU 101 genome. Similarly, no genes responsible for the decarboxylation of 2-phenylethylamine, spermine, or tyramine were detected. Additionally, no other enzymes involved in these synthetic pathways were identified.

In the gene annotation results obtained from PGAP, NTU 101 was found to contain the gene encoding L-ornithine decarboxylase [EC: 4.1.1.17], an enzyme widely present in

L. paracasei strains, confirmed via BLASTp search of the RefSeq protein database. L-ornithine decarboxylase catalyzes the conversion of L-ornithine to putrescine. This enzyme has been previously reported in the

L. paracasei genome [

41,

42,

43]. Furthermore, we identified intact genes encoding the four subunits of the channel protein PotABCD, which transports putrescine [

44,

45]. Additionally, a gene encoding putative lysine decarboxylase [EC 4.1.1.18], responsible for producing cadaverine from lysine, was also identified, though conserved domain analysis suggested it may not correspond to this enzyme.

The genes encoding synthetic enzymes related to certain biogenic amines, including 2-phenylethylamine, tyramine, and spermine, were not detected, which aligns with findings from previous studies [

46,

47]. It has been hypothesized that an unidentified enzyme with amino acid decarboxylase activity may exist, warranting further investigation into the enzymes involved in biogenic amine production.

Lactic acid bacteria often metabolize amino acids to generate energy or as a survival mechanism in low pH environments [

48]. According to a report by the EFSA [

49], fermented dairy products are known to contain biogenic amines, with average levels of histamine, tyramine, putrescine, and cadaverine ranging from 0.3 to 65.1, 0.3 to 335, 0.7 to 449, and 1.9 to 628 ppm, respectively. Acid curd cheese typically contains higher concentrations of biogenic amines (51.3 to 628 ppm) compared to yogurt (0.5 to 3.2 ppm). Similar levels of biogenic amines are found in fermented soy products, though concentrations vary depending on the food type [

50].

Although spermine levels in fermented dairy products are generally low (0.02 to 0.8 ppm), it is present in higher concentrations in other foods, such as lean beef (27.3 to 36.4 ppm) [

51]. In fermented soy products, spermine levels typically range from 1.3 to 242 ppm [

50]. The biogenic amine content produced by NTU 101 is relatively low compared to that found in fermented or general foods, suggesting a minimal risk of harm [

50,

51]. Thus, it is unlikely that the biogenic amines produced by NTU 101 in fermented foods pose any significant health risk.

3.4. Virulence factor and Hemolysis Activity

We performed a BLAST search of the NTU 101 genome against sequences from the VFDB to identify potential virulence genes. The VFDB dataset is divided into DNA and protein categories, and our analysis utilized the full datasets from both categories. These datasets encompass known and predicted virulence factor genes associated with pathogenicity. To begin, we applied the EFSA criteria (identity >80%, coverage >70%) to analyze the results from both the DNA and protein databases. After screening, no potential virulence genes were detected. Even when the identity threshold was lowered to greater than 70%, with coverage still above 70%, the DNA dataset analysis did not reveal any virulence genes. However, the protein database analysis identified four potential virulence genes. These four protein sequences were further examined using BLASTp in the NCBI RefSeq protein database, revealing that these genes are commonly found in Lacticaseibacillus paracasei (data not shown).

For hemolytic activity, both phenotypic and genotypic methods were employed. Phenotypic analysis showed that NTU 101 and

L. paracasei subsp.

paracasei BCRC 12248

T exhibited α-hemolysis under aerobic conditions. However, no hemolysis (gamma hemolysis) was observed when NTU 101 and BCRC 12248

T were cultured under anaerobic conditions (

Figure 1). Similarly, two other

L. paracasei subsp.

paracasei strains (BCRC 14023 and BCRC 17002) and

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus BCRC 16000 also showed α-hemolysis under aerobic conditions, with no hemolysis under anaerobic conditions (data not shown). This aligns with previous studies that report

Lactobacillus species typically exhibit α-hemolysis on blood agar [

52]. This characteristic has been consistently documented in various reports on

L. paracasei strains, such as

L. paracasei Lpc-37 [

53] and L2 [

54]. These findings suggest that α-hemolysis is a common trait among lactic acid bacteria (LAB), particularly in

L. paracasei strains.

Our VFDB search identified three hemolytic toxin-coding genes in the NTU 101 genome, which may belong to the hemolysin III family (one gene) and the hemolysin family (two genes) (

Table 4). BLASTp searches in the RefSeq protein database indicated that these proteins are highly conserved across

Lacticaseibacillus, encoded by

YafA and

TlyC (

Table 5). Although the

YqfA gene is commonly found in the

Lacticaseibacillus genus [

55], no safety concerns have been reported in relation to this gene. Additionally, BLASTp analysis confirmed that the

TlyC-encoded hemolysin protein family is widely present in

L. paracasei strains (data not shown). Importantly, the phenotypic analysis of NTU 101 on blood agar demonstrated no β-hemolysis. Furthermore, no safety concerns related to hemolysis have been reported in previous studies on

L. paracasei. Thus, we conclude that NTU 101 poses no significant risk of hemolysis.

3.5. Mucin Degradation and Intestinal Mucosal Barrier

Mucin degradation is an undesirable characteristic in probiotics due to its potential to compromise the intestinal mucosal barrier, which plays a crucial role in host defense. Disruption or damage to this protective mucin layer can lead to adverse effects [

27]. To assess whether NTU 101 possesses mucin-degrading activity, we conducted a mucin hydrolysis test. NTU 101 did not grow on PSM-only plates, and no mucin degradation was observed (

Figure 2). In contrast, the positive control strain,

Salmonella enterica subsp.

enterica BCRC 10747, grew normally (

Table 6). Similarly, previous studies of

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium species, which are commonly used probiotic strains, also reported no mucin-degrading activity [

27,

56,

57].

Microbes that degrade mucin typically possess glycosyl hydrolases (GHs), enzymes that cleave specific glycan linkages. According to Glover et al. (2022), the key GHs involved in mucin degradation include GH33, GH29, GH95, and GH20/35 [

58]. Whole-genome analysis of NTU 101 using the CAZy database revealed that it contains genes associated with GH29 and GH20/35 but lacks those for GH33 and GH95 (

Table 7). As a result, NTU 101 does not have the complete genetic capability required for mucin degradation, which aligns with the results of the mucin degradation phenotype experiment. To further evaluate the potential impact of NTU 101 on the intestinal barrier, we utilized the C2BBe1 intestinal epithelial cell line to establish a monolayer membrane model mimicking the intestinal barrier. No translocation of NTU 101 was observed in this model with intact barrier function. In conclusion, NTU 101 does not degrade mucin nor compromise the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier.

3.6. D/L-Lactic Acid Production and Bile Salts Hydrolase Activity

The production of L- and D-lactic acid by NTU 101 was assessed, revealing that 96.3% of the lactate produced was the L-enantiomer. D-lactic acid is generated from pyruvate via the enzyme D-lactate dehydrogenase. Gene annotation results for NTU 101 identified an enzyme with D-lactate dehydrogenase activity, specifically D-2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase, suggesting that the D-lactic acid present in the fermentation broth is produced by NTU 101. D-lactic acidosis, a rare form of lactic acidosis, is most commonly observed in patients with short bowel syndrome. High levels of D-lactate in the bloodstream can lead to neurological symptoms such as delirium, ataxia, and dysarthria [

59]. Although symptomatic patients typically exhibit elevated D-lactate levels, the risk of D-lactic acidosis in healthy individuals is considered low [

60]. Compared to other lactic acid bacteria, NTU 101 produces a relatively low proportion of D-lactate. For example,

Limosilactobacillus reuteri NCIMB 3053 produces 54.5% D-lactate, and

Lactobacillus delbrueckii ATCC 11842 produces 52.2% [

61]. In contrast, NTU 101’s D-lactate proportion is comparable to other GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) strains, such as

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG and

Bifidobacterium animalis subsp.

lactis BB-12, both of which produce less than 5% D-lactate [

62,

63].

Phenotypic experiments on NTU 101 indicated no bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity when compared to the positive control group in TDCA MRS agar plates (

Figure 3). This is consistent with findings from other studies on

Lactobacillus (based on the previous taxonomy), where many species were also found to lack BSH activity [

25,

64]. TDCA is a bile salt conjugate of deoxycholic acid and taurine. Bacterial BSH activity breaks down conjugated bile salts, resulting in free bile acids, which are poorly soluble and form a white precipitate [

30,

65].

Despite the absence of observable BSH activity, a putative gene encoding BSH was identified through a protein sequence analysis of NTU 101. A BLASTp search against the RefSeq protein database revealed that this gene encodes a linear amide C-N hydrolase. Previous research by Zhang et al. (2009) [

66] suggested that the linear amide C-N hydrolase of

Lactobacillus casei Zhang exhibits BSH activity. Sequence alignment of the linear amide C-N hydrolase from NTU 101 with that of

L. casei Zhang (accession no. ACC93573.1) showed 100% similarity, indicating that NTU 101 may possess BSH functionality. Additionally, research by Elkins et al. (2001) [

67] demonstrated that BSH activity in LAB is related to bile salt transporters. However, limited research exists on

Lacticaseibacillus in this context, leading us to speculate that NTU 101's BSH activity may be influenced by bile salt transporter functionality.

3.7. Repeated Dose 90-Day Oral Toxicity Study in Rats

The results of the 90-day oral toxicity study revealed that none of the rats in either the treatment or control groups exhibited any abnormal clinical signs throughout the study period (

Table 8 and

Table 9). All rats in the treatment groups demonstrated normal weight gain (

Table 10). Ophthalmological examinations revealed no abnormalities in any of the rats across both the treatment and control groups.

At the conclusion of the study, clinical pathology assessments, including hematology, clinical biochemistry, and urinalysis were conducted. While some parameters showed statistically significant differences, all values fell within or were close to the normal reference range. All surviving rats were sacrificed, and the absolute weights of major organs were measured (

Table 10). Significant differences were noted in the spleen weight of the male medium-dose group, the brain weight of the male high-dose group, and the liver weight of the female medium-dose group compared to the control group. However, these differences remained within the normal reference range (based on Super Laboratory historical values). No pathological lesions related to the test article were observed in any associated organs, indicating that these changes had no clinical relevance.

Necropsy examinations found no significant abnormalities in rats from either the treatment or control groups. Histopathological analysis also revealed no specific organ toxicity or pathological changes associated with the test article in rats from the high-dose and control groups.

Based on these findings, the no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) of NTU 101 powder for the 90-day repeated-dose oral toxicity study in rats was determined to be 2000 mg/kg body weight, which is 120 times the recommended daily human intake (1000 mg/60 kg body weight).

4. Conclusions

Based on integrated phenotypic and genotypic analysis, NTU 101 poses no risk of antibiotic resistance. This strain does not exhibit β-hemolysis and only demonstrates α-hemolysis under aerobic culturing conditions, which is a typical characteristic of Lactobacillus strains. Additionally, there are no previous reports of pathogenicity associated with NTU 101. While it contains a few genes that encode enzymes capable of producing biogenic amines, only low levels of biogenic amines are produced in certain fermented foods. Importantly, NTU 101 lacks markers for pathogenic or toxigenic gene variants. The primary lactate produced by this strain is L-lactic acid, with D-lactic acid constituting less than 5% of the total lactate content. Although NTU 101 possesses the BSH gene, phenotypic testing showed no activity. Furthermore, phenotypic and genotypic assessments of mucin degradation revealed that NTU 101 cannot degrade mucin. No translocation of NTU 101 across intestinal epithelial cells was observed, suggesting that the strain does not compromise the intestinal barrier. The results of a 90-day repeated-dose oral toxicity study, along with previous human clinical trials, indicated no adverse reactions, even at a dose of 1000 mg/kg. Based on these safety assessment data, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 is considered safe for use in food products. Further studies will build on these findings to analyze the uncharacterized traits of NTU 101 and potential, yet undiscovered, safety risks using transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 under (A) light microscope. (B) scanning electron microscope.; Figure S2: COG functional classification of NTU 101.; Table S1: API 50 CHL panel results of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101.; Table S2: Whole genome sequence information of NTU 101, including basic data and quality evaluation of genome assembly. “Whole genome sequence information of NTU 101, including basic data and quality evaluation of genome assembly, was compared with that of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei JCM 8130T.”.

Author Contributions

Chieh-Ting Chen: responsible for data analysis, interpretation, writing the manuscript. Wen-Yu Chao: conducted the experiments and interpreted the data. Chih-Hui Lin: design analytical methods and conducted the analysis. Tsung-Wei Shih: research advice and discussed the research framework. Tzu-Ming Pan: research advice, project administration, conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this study are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Food Industry Research and Development Institute (Hsinchu, Taiwan) and Super Laboratory Co., Ltd. (New Taipei City, Taiwan) for their technical support and assistance in the phenotypic analysis and the oral toxicity study in rats, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

C. T. Chen, W. Y. Chao, T. W. Shih. and T. M. Pan are employed by SunWay Biotech Co., LTD. The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Naidu, A.S.; Bidlack, W.R.; Clemens, R.A. Probiotic spectra of lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1999, 39, 13–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxelin, M.; Rautelin, H.; Salminen, S.; Mäkelä, P.H. Safety of commercial products with viable Lactobacillus strains. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 1996, 5, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Klaenhammer, T.R.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Pot, B.; Johansen, E.; Heimbach, J.T.; Marco, M.L.; Tennilä, J.; Ross, R.P.; Franz, C.; et al. Effects of genetic, processing, or product formulation changes on efficacy and safety of probiotics. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1309, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariza, M.W.; Gillies, K.O.; Kraak-Ripple, S.F.; Leyer, G.; Smith, A.B. Determining the safety of microbial cultures for consumption by humans and animals. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 73, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization (FAO/WHO). Probiotics in food. Health and nutritional properties and guidelines for evaluation. Guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food. report of a joint FAO/WHO working group on drafting guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food. 2002. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/382476b3-4d54-4175-803f-2f26f3526256/content.

- Marteau, P. Safety aspects of probiotic products. Näringsforskning 2001, 45, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. EFSA statement on the requirements for whole genome sequence analysis of microorganisms intentionally used in the food chain. EFSA Journal 2021, 19, 6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesco, R.; Trujillo, M.E. Update on the proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.M.; Chiu, C.H.; Pan, T.M. Fermentation of a milk–soymilk and Lycium chinense Miller mixture using a new isolate of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 and Bifidobacterium longum. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 31, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.F.; Hu, C.L.; Chiang, S.S.; Tseng, K.C.; Yu, R.C.; Pan, T.M. Beneficial preventive effects of gastric mucosal lesion for soy−skim milk fermented by lactic acid bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 4433–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.C.; Tseng, W.T.; Pan, T.M. Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 ameliorates impaired glucose tolerance induced by a high-fat, high-fructose diet in Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 24, 472–481. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Lo, Y.H.; Pan, T.M. Anti-obesity activity of Lactobacillus fermented soy milk products. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.Y.; Dai, R.Y.; Tsai, W.L.; Sun, Y.C.; Pan, T.M. Effect of fermented milk produced by Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 on blood lipid. Taiwan J Agric Chem Food Sci 2012, 50, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.T.; Cheng, P.C.; Fan, C.K.; Pan, T.M. Time-dependent persistence of enhanced immune response by a potential probiotic strain Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 128, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Na, G.H.; Yim, D.J.; Liu, C.F.; Lin, T.H.; Shih, T.W.; Pan, T.M.; Lee, C.L.; Koo, Y.K. Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 prevents obesity by regulating AMPK pathways and gut microbiota in obese rat. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 731, 150279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.F.; Shih, T.W.; Lee, C.L.; Pan, T.M. The beneficial role of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 in the prevention of atopic dermatitis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 2236–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.L.; Liou, J.M.; Lu, T.M.; Lin, Y.H.; Wang, C.K.; Pan, T.M. Effects of Vigiis 101-LAB on a healthy population’s gut microflora, peristalsis, immunity, and anti-oxidative capacity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.H.; Shih, T.W.; Lin, C.H. Effects of Lactocaseibacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 on gut microbiota: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.T.; Shih, T.W.; Liu, S.H.; Pan, T.M. Safety and mutagenicity evaluation of Vigiis 101 powder made from Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Guidance on the characterisation of microorganisms used as feed additives or as production organisms. EFSA Journal 2018, 16, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murigneux, V.; Roberts, L.W.; Forde, B.M.; Phan, M.D.; Nhu, N.T.K.; Irwin, A.D.; Harris, P.N.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Schembri, M.A.; Whiley, D.M.; et al. MicroPIPE: validating an end-to-end workflow for high-quality complete bacterial genome construction. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, X.; Li, K.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, X.; Hao, H.; Bi, J.; Zhang, G.; Hou, H. The impact of microbial diversity on biogenic amines formation in grasshopper sub shrimp paste during the fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Bi, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, G.; Hao, H.; Hou, H. Contribution of microorganisms to biogenic amine accumulation during fish sauce fermentation and screening of novel starters. Foods 2021, 10, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerola, S.; Hinkkanen, R.; Lindfors, E.; Hirvi, T. Liquid chromatographic determination of biogenic amines in dry sausages. J. AOAC Int. 1993, 76, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casarotti, S.N.; Carneiro, B.M.; Todorov, S.D.; Nero, L.A.; Rahal, P.; Penna, A.L.B. In vitro assessment of safety and probiotic potential characteristics of lactobacillus strains isolated from water buffalo mozzarella cheese. Ann. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, R. American Society for Microbiology. Blood Agar Plates and Hemolysis Protocols. 2005. https://asm.org/getattachment/7ec0de2b-bb16-4f6e-ba07-2aea25a43e76/protocol-28.

- Zhou, J.S.; Gopal, P.K.; Gill, H.S. Potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus rhamnosus (HN001), Lactobacillus acidophilus (HN017) and Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019) do not degrade gastric mucin in vitro. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 63, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatmawati, N.N.D.; Goto, K.; Mayura, I.P.B.; Nocianitri, K.A.; Ramona, Y.; Sakaguchi, M.; Matsushita, O.; Sujaya, I.N. Caco-2 cells monolayer as an in-vitro model for probiotic strain translocation. Bali Med. J. 2020, 9, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Mondal, S.C.; Jeong, C.R.; Kim, S.R.; Ban, O.H.; Jung, Y.H.; Yang, J.; Kim, S.J. Safety evaluation of Lactococcus lactis IDCC 2301 isolated from homemade cheese. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashkevicz, M.P.; Feighner, S.D. Development of a differential medium for bile salt hydrolase-active Lactobacillus spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1989, 55, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Waite, D.W.; Rinke, C.; Skarshewski, A.; Chaumeil, P.A.; Hugenholtz, P. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciufo, S.; Kannan, S.; Sharma, S.; Badretdin, A.; Clark, K.; Turner, S.; Brover, S.; Schoch, C.L.; Kimchi, A.; DiCuccio, M. Using average nucleotide identity to improve taxonomic assignments in prokaryotic genomes at the NCBI. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 2386–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.; Paek, J.J.; Lee, Y. Antimicrobial resistance of seventy lactic acid bacteria isolated from commercial probiotics in Korea. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.F.; Hsia, K.C.; Kuo, Y.W.; Chen, S.H.; Huang, Y.Y.; Li, C.M.; Hsu, Y.C.; Tsai, S.Y.; Ho, H.H. Safety assessment and probiotic potential comparison of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis BLI-02, Lactobacillus plantarum LPL28, Lactobacillus acidophilus TYCA06, and Lactobacillus paracasei ET-66. Nutrients 2024, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Guidance on the assessment of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials of human and veterinary importance. EFSA Journal 2012, 10, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Raphenya, A.R.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Tsang, K.K.; Bouchard, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Huynh, W.; Nguyen, A.L.V.; Cheng, A.A.; Liu, S.; et al. CARD 2020: antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, D517–D525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerushalmi, H.; Lebendiker, M.; Schuldiner, S. EmrE, an Escherichia coli 12-kDa multidrug transporter, exchanges toxic cations and H+ and is soluble in organic solvents. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 6856–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, F.; Montanari, C.; Gardini, F.; Tabanelli, G. Biogenic amine production by lactic acid bacteria: a review. Foods 2019, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA GRN 429. Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota, 2012. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20171031055001/https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/GRAS/NoticeInventory/ucm309143.pdf.

- Markusková, B.; Lichvariková, A.; Szemes, T.; Koreňová, J.; Kuchta, T.; Drahovská, H. Genome analysis of lactic acid bacterial strains selected as potential starters for traditional Slovakian bryndza cheese. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Chen, T.Y.; Wu, C.C.; Cheng, S.H.; Chang, M.Y.; Cheng, W.H.; Chiu, S.H.; Chen, C.C.; Tsai, Y.C.; Yang, D.J.; et al. Safety evaluation and anti-inflammatory efficacy of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei PS23. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, R.; Kume, A.; Nishiyama, C.; Honda, R.; Shirasawa, H.; Ling, Y.; Sugiyama, Y.; Nara, M.; Shimokawa, H.; Kawada, H.; et al. Putrescine production by Latilactobacillus curvatus KP 3-4 isolated from fermented foods. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaal, S.; Al Safadi, R.; Osman, D.; Hiron, A.; Gilot, P. Investigation of the polyamine biosynthetic and transport capability of Streptococcus agalactiae: the non-essential PotABCD transporter. Microbiology 2021, 167, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wen, X.; Wen, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Wei, X. Evaluation of the biogenic amines formation and degradation abilities of Lactobacillus curvatus from chinese bacon. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zou, D.; Ruan, L.; Wen, Z.; Chen, S.; Xu, L.; Wei, X. Evaluation of the biogenic amines and microbial contribution in traditional chinese sausages. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanovic, E.; McAuliffe, O. Comparative genomic and metabolic analysis of three Lactobacillus paracasei cheese isolates reveals considerable genomic differences in strains from the same niche. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific opinion on risk based control of biogenic amine formation in fermented foods. EFSA Journal 2011, 9, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, J.H.; Park, Y.K.; Jin, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, H.J. Bacterial production and control of biogenic amines in Asian fermented soybean foods. Foods 2019, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiya, A.M.; Eric, P.; Roger, S.; Agneta, Y. Polyamines in foods: development of a food database. Food Nutr. Res. 2011, 55, 5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, E.J.C.; Tyrrell, K.L.; Citron, D.M. Lactobacillus species: taxonomic complexity and controversial susceptibilities. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, S98–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA GRN 736. Lactobacillus casei subsp. paracasei Lpc-37, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/media/125422/download. 1254.

- M’hamed, A.C.; Ncib, K.; Merghni, A.; Migaou, M.; Lazreg, H.; Snoussi, M.; Noumi, E.; Mansour, M.B.; Maaroufi, R.M. Characterization of probiotic properties of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei L2 isolated from a traditional fermented food “lben”. Life 2023, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokesajjawatee, N.; Santiyanont, P.; Chantarasakha, K.; Kocharin, K.; Thammarongtham, C.; Lertampaiporn, S.; Vorapreeda, T.; Srisuk, T.; Wongsurawat, T.; Jenjaroenpun, P.; et al. Safety assessment of a nham starter culture Lactobacillus plantarum BCC9546 via whole-genome analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, F.; Muto, M.; Yaeshima, T.; Iwatsuki, K.; Aihara, H.; Ohashi, Y.; Fujisawa, T. Safety evaluation of probiotic bifidobacteria by analysis of mucin degradation activity and translocation ability. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.; Singh, R.; Tyagi, A.; Rashmi, H.M.; Batish, V.K.; Grover, S. Assessing safety of Lactobacillus plantarum MTCC 5690 and Lactobacillus fermentum MTCC 5689 using in vitro approaches and an in vivo murine model. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 101, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, J.S.; Ticer, T.D.; Engevik, M.A. Characterizing the mucin-degrading capacity of the human gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowlgi, N.G.; Chhabra, L. D-lactic acidosis: an underrecognized complication of short bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2015, 2015, 476215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, W.Y.; Chae, S.A.; Ban, O.H.; Oh, S; Park, C.; Lee, M.; Shin, M.; Yang, J.; Jung, Y.H. The in vitro and in vivo safety evaluation of Lactobacillus acidophilus IDCC 3302. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 49, 39–44. [CrossRef]

- Sulemankhil, I.; Parent, M.; Jones, M.L.; Feng, Z.; Labbé, A.; Prakash, S. In vitro and in vivo characterization and strain safety of Lactobacillus reuteri NCIMB 30253 for probiotic applications. Can. J. Microbiol. 2012, 58, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA GRN 1013. Lactobacillus rhamnosus DSM 33156. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/155445/download.

- FDA GRN 856. Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis BB-12. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/134330/download.

- Solieri, L.; Bianchi, A.; Mottolese, G.; Lemmetti, F.; Giudici, P. Tailoring the probiotic potential of non-starter Lactobacillus strains from ripened parmigiano reggiano cheese by in vitro screening and principal component analysis. Food Microbiol. 2014, 38, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liong, M.T.; Shah, N.P. Bile salt deconjugation ability, bile salt hydrolase activity and cholesterol co-precipitation ability of Lactobacilli strains. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Wu, R.N.; Sun, Z.H.; Sun, T.S.; Meng, H.; Zhang, H.P. Molecular cloning and characterization of bile salt hydrolase in Lactobacillus casei Zhang. Ann. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, C.A.; Moser, S.A.; Savage, D.C. Genes encoding bile salt hydrolases and conjugated bile salt transporters in Lactobacillus johnsonii 100-100 and other Lactobacillus species. Microbiology 2001, 147, 3403–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Hemolysis type test by 5% sheep blood agar assay of each strain, cultured under different anaerobic conditions. The bottom piece of paper with printed text shows the difference in transparency of plates of different strains.

Figure 1.

Hemolysis type test by 5% sheep blood agar assay of each strain, cultured under different anaerobic conditions. The bottom piece of paper with printed text shows the difference in transparency of plates of different strains.

Figure 2.

The results of the mucin degradation activity assay of NTU 101 and reference strains. PSM is the medium with mucin as the sole carbon source. PSMG is the PSM with additional glucose. Each number represents the following strain: 1, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101. 2, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 17002. 3, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 12248T. 4, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 14023. 5, L. rhamnosus BCRC 16000. 6, S. enterica subsp. enterica BCRC 10747 (mucin degradation activity positive strain).

Figure 2.

The results of the mucin degradation activity assay of NTU 101 and reference strains. PSM is the medium with mucin as the sole carbon source. PSMG is the PSM with additional glucose. Each number represents the following strain: 1, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101. 2, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 17002. 3, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 12248T. 4, L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 14023. 5, L. rhamnosus BCRC 16000. 6, S. enterica subsp. enterica BCRC 10747 (mucin degradation activity positive strain).

Figure 3.

The results of BSH activity assay on 5% TDCA containing MRS plates. The white precipitate beneath the colonies is deoxycholic acid produced by BSH hydrolysis of TDCA, indicating that L. acidophilus BCRC 10695T has positive BSH activity. BSH activity of NTU 101 was shown to be negative.

Figure 3.

The results of BSH activity assay on 5% TDCA containing MRS plates. The white precipitate beneath the colonies is deoxycholic acid produced by BSH hydrolysis of TDCA, indicating that L. acidophilus BCRC 10695T has positive BSH activity. BSH activity of NTU 101 was shown to be negative.

Table 1.

Antibiotic resistance results of NTU 101 through genotypic and phenotypic analysis. Antimicrobial minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) results compare to L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 12248T.

Table 1.

Antibiotic resistance results of NTU 101 through genotypic and phenotypic analysis. Antimicrobial minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) results compare to L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 12248T.

| Resistance target |

Phenotypic analysis |

|

Genotypic analysis |

| MIC (mg/L) |

Susceptibility of NTU 101b |

|

CARD |

ResFinder |

AMRfinderPlus |

| Antibiotics |

|

|

| Ampicillin |

4 |

2 |

1 |

S |

|

N.D.d

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Vancomycin |

n.r.c

|

- |

- |

R |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Gentamicin |

32 |

4 |

4 |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Kanamycin |

64 |

64 |

64 |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Streptomycin |

64 |

64 |

64 |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Erythromycin |

1 |

0.5 |

0.25 |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Clindamycin |

4 |

0.5 |

0.25 |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Tetracycline |

4 |

4 |

2 |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Chloramphenicol |

4 |

8 |

8 |

R |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Disinfecting agents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Benzalkonium chloride |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Strict (qacJ) |

N.D. |

- |

Table 2.

Determination of biogenic amines in different fermentation media produced by NTU 101.

Table 2.

Determination of biogenic amines in different fermentation media produced by NTU 101.

| Fermented medium |

Groupa |

|

Biogenic amines (ppm)b |

| |

HIS |

TYR |

PUT |

TRP |

PHE |

CAD |

SPD |

SPR |

| MRS |

B |

|

N.D.c

|

2.76 ± 0.14 |

N.D. |

16.13 ± 0.70 |

3.66 ± 0.67 |

2.49d

|

11.97 ± 0.54 |

3.67 ± 0.17 |

| |

S |

|

N.D. |

2.83 ± 0.05 |

N.D. |

13.83 ± 0.09 |

3.25 ± 0.09 |

4.18 ± 0.17 |

8.41 ± 0.23 |

3.33 |

| Skim milk |

B |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

2.78±0.17 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

3.11±0.36 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Low-fat milk |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sample 1 |

B |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N. D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

2.68 ± 0.08 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Sample 2 |

B |

|

N.D. |

12.09 ± 11.03 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

2.20 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| |

S |

|

N.D. |

25.26 ± 19.19 |

4.54 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

2.85 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Sample 3 |

B |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

2.65 |

N.D. |

2.73 ± 0.12 |

12.42 ± 7.44 |

| |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

3.79 |

N.D. |

2.78 ± 0.02 |

22.47 ± 9.58 |

| Soymilk |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sample 1 |

B |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

5.61 ± 0.60 |

10.68 ± 1.28 |

N.D. |

2.70 ± 0.09 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| |

S |

|

N.D. |

N.D. |

N. D. |

7.36 ± 2.06 |

N.D. |

3.36 ± 0.36 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Sample 2 |

B |

|

6.83 ± 1.04 |

N.D. |

4.91 |

13.60 ± 1.39 |

N.D. |

2.29 ± 0.47 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| |

S |

|

3.07 ± 1.79 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

2.56 ± 0.11 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

| Sample 3 |

B |

|

2.91 ± 0.27 |

4.18 |

N.D. |

6.60 ± 1.97 |

N.D. |

3.11 ± 0.57 |

8.78 ± 5.96 |

N.D. |

| |

S |

|

2.89 ± 0.05 |

12.73 ± 1.44 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

2.57 ± 0.16 |

9.33 ± 4.51 |

N.D. |

| Sample 4 |

B |

|

2.33 |

2.40 ± 0.12 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

9.03 ± 0.20 |

N.D. |

| |

S |

|

2.44 |

2.39 ± 0.16 |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

8.08 ± 0.30 |

N.D. |

Table 3.

Analysis of the corresponding decarboxylase-encoding genes for the generation of biogenic amine by NTU 101.

Table 3.

Analysis of the corresponding decarboxylase-encoding genes for the generation of biogenic amine by NTU 101.

| Biogenic amine |

|

Enzyme of decarboxylation |

|

KEGG entry |

|

Annotated

protein ID |

BLASTp hit

/Putative conserved domain |

| Histamine |

|

histidine decarboxylase |

|

K01590 |

|

Not found |

|

| Tyramine |

|

tyrosine decarboxylase |

|

K01592, K18933, K22329, K22330 |

|

Not found |

|

| Putrescine |

|

L-ornithine decarboxylase |

|

K01581 |

|

PGAP_000721 |

L-ornithine decarboxylase /PRK13578 (ornithine decarboxylase; provisional) |

| |

agmatinase |

|

K01480 |

|

Not found |

|

| Tryptamine |

|

L-tryptophan decarboxylase |

|

K01593, K22433 |

|

Not found |

|

| 2-phenylethylamine |

|

phenylalanine decarboxylase |

|

K22427 |

|

Not found |

|

| |

L-tryptophan decarboxylase |

|

K01593 |

|

Not found |

|

| Agmatine |

|

arginine decarboxylase |

|

K01583, K01584, K01585, K02626 |

|

Not found |

|

| Cadaverine |

|

L-lysine decarboxylase |

|

K01582 |

|

PGAP_000762 |

TIGR00730 family Rossman fold protein (putative lysine decarboxylases) /PpnN (Nucleotide transport and metabolism) |

| |

D-ornithine/D-lysine decarboxylase |

|

K23385 |

|

Not found |

|

| Spermidine |

|

spermidine synthase |

|

K00797, K24034 |

|

Not found |

|

| |

carboxynorspermidine decarboxylase |

|

K13747 |

|

Not found |

|

| Spermine |

|

spermine synthase |

|

K00802 |

|

Not found |

|

Table 4.

The hemolysis type of each strain. Staphylococcus aureus BCRC 12154 acts as β-hemolysis positive strain.

Table 4.

The hemolysis type of each strain. Staphylococcus aureus BCRC 12154 acts as β-hemolysis positive strain.

| |

|

Hemolysis typea

|

| No. |

Strain |

Aerobic condition |

Anaerobic condition |

| 1 |

L. paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 |

α |

γ |

| 2 |

L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 17002 |

α |

γ |

| 3 |

L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 12248T

|

α |

γ |

| 4 |

L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 14023 |

α |

γ |

| 5 |

L. rhamnosus BCRC 16000 |

α |

γ |

| 6 |

S. aureus BCRC 12154 |

β |

β |

Table 5.

Genotypic analysis of the hemolysis-related genes in NTU 101.

Table 5.

Genotypic analysis of the hemolysis-related genes in NTU 101.

| |

|

VFDB Predicted |

|

BLAST result |

| Predicted protein ID |

|

VF category |

Function |

|

BLASTp hitsa/ Putative conserve domain |

| PGAP_000462 |

|

VFG038907 |

hemolysin III |

|

hemolysin III family protein [Lacticaseibacillus paracasei]/ YqfA

|

| PAGP_000832 |

|

VFG038902 |

Hemolysin A |

|

hemolysin family protein [Lacticaseibacillus paracasei]/ TlyC

|

| PAGP_001231 |

|

VFG038900 |

Hemolysin A |

|

hemolysin family protein [Lacticaseibacillus paracasei]/ TlyC

|

Table 6.

Results of mucin degradation ability of each strain, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica BCRC 10747 as a positive strain.

Table 6.

Results of mucin degradation ability of each strain, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica BCRC 10747 as a positive strain.

| |

|

PSM |

PSMG |

| No. |

Strain |

Mucin degradation |

Colony formation |

Mucin degradation |

Colony formation |

| 1 |

L. paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 |

-a

|

-b

|

- |

- |

| 2 |

L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 17002 |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

| 3 |

L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 12248T

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 4 |

L. paracasei subsp. paracasei BCRC 14023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 5 |

L. rhamnosus BCRC 16000 |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

| 6 |

S. enterica subsp. enterica BCRC 10747 |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

Table 7.

Genotypic analysis results of mucin degradation relative genes of NTU 101. A single CAZy family may encompass multiple enzymes with distinct catalytic activities or substrate specificities.

Table 7.

Genotypic analysis results of mucin degradation relative genes of NTU 101. A single CAZy family may encompass multiple enzymes with distinct catalytic activities or substrate specificities.

CAZy

family

|

|

Predicted protein ID |

|

Correspond enzymea

|

| |

|

| GH2 |

|

PGAP_001529 |

|

β-galactosidase [EC 3.2.1.23] |

| GH20 |

|

PGAP_001643 |

|

β-N-acetylhexosaminidase [EC 3.2.1.52] |

| |

|

endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase [EC 3.2.1.96] |

| |

|

β-galactosidase [EC 3.2.1.23] |

| GH29 |

|

PGAP_000883

PGAP_002109 |

|

α-L-fucosidase [EC 3.2.1.51] |

| GH33 |

|

|

|

Not found |

| GH35 |

|

PGAP_001638 |

|

β-galactosidase [EC 3.21.23] |

| |

|

β-fucosidase [EC 3.2.1.-] |

| |

|

glycosidases group [EC 3.2.1.38] |

| GH95 |

|

|

|

Not found |

Table 8.

Changes of hematological parameters in male and female rats treated with NTU 101. powder via gastric gavage for 90 consecutive daysa.

Table 8.

Changes of hematological parameters in male and female rats treated with NTU 101. powder via gastric gavage for 90 consecutive daysa.

| |

|

Dose |

| |

|

Control |

Low Dose

(500 mg/kg) |

Medium dose

(1000 mg/kg) |

High dose

(2000 mg/kg) |

| Male |

|

|

|

|

|

| WBC (103/μL) |

|

11.9 ± 2.3 |

11.4 ± 2.1 |

12.1 ± 1.6 |

11.1 ± 2.2 |

| RBC (106/μL) |

|

9.7 ± 0.5 |

9.8 ± 0.8 |

9.6 ± 0.4 |

9.9 ± 0.6 |

| HB (g/dL) |

|

16.9 ± 0.5 |

16.9 ± 0.9 |

16.6 ± 0.8 |

17.1 ± 1.2 |

| HCT (%) |

|

49.8 ± 1.2 |

49.6 ± 2.8 |

48.8 ± 1.9 |

50.3 ± 3.5 |

| MCV (fL) |

|

51.4 ± 2.2 |

50.7 ± 2.6 |

50.6 ± 1.5 |

50.8 ± 2.7 |

| MCH (pg) |

|

17.4 ± 0.6 |

17.3 ± 0.8 |

17.2 ± 0.4 |

17.3 ± 0.8 |

| MCHC (g/dL) |

|

33.9 ± 0.4 |

34.0 ± 0.5 |

34.1 ± 0.8 |

34.1 ± 0.6 |

| PLT (103/μL) |

|

955.2 ± 118.7 |

1026.1 ± 118.9 |

1040.4 ± 121.8 |

1043.0 ± 121.6 |

| Neutrophil (%) |

|

23.2 ± 7.3 |

24.6 ± 9.4 |

22.9 ± 5.2 |

23.0 ± 8.0 |

| LYMPH (%) |

|

69.1 ± 7.6 |

68.4 ± 10.4 |

69.8 ± 5.4 |

70.5 ± 7.9 |

| Monocyte (%) |

|

6.2 ± 1.1 |

5.3 ± 1.3 |

5.5 ± 1.0 |

5.2 ± 0.7* |

| Eosinophil (%) |

|

1.3 ± 0.3 |

1.6 ± 0.5 |

1.5 ± 0.6 |

1.1 ± 0.4 |

| Basophil (%) |

|

0.2 ± 0.1 |

0.2 ± 0.1 |

0.3 ± 0.1 |

0.2 ± 0.1 |

| PT (sec.) |

|

14.9 ± 3.2 |

14.1 ± 1.5 |

13.0 ± 2.7 |

13.5 ± 2.1 |

| Female |

|

|

| WBC (103/μL) |

|

8.8 ± 2.0 |

8.1 ± 2.2 |

8.6 ± 2.0 |

7.6 ± 1.0 |

| RBC (106/μL) |

|

8.9 ± 0.3 |

9.0 ± 1.1 |

9.0 ± 0.5 |

8.9 ± 0.6 |

| HB (g/dL) |

|

16.2 ± 0.8 |

16.5 ± 1.6 |

16.3 ± 1.0 |

16.4 ± 0.9 |

| HCT (%) |

|

47.6 ± 2.0 |

48.5 ± 4.3 |

48.0 ± 2.5 |

48.3 ± 2.2 |

| MCV (fL) |

|

53.8 ± 2.1 |

53.9 ± 2.4 |

53.4 ± 1.4 |

54.3 ± 2.1 |

| MCH (pg) |

|

18.3 ± 0.7 |

18.3 ± 0.6 |

18.1 ± 0.3 |

18.4 ± 0.5 |

| MCHC (g/dL) |

|

34.0 ± 0.6 |

34.0 ± 0.5 |

33.9 ± 0.6 |

33.8 ± 0.8 |

| PLT (103/μL) |

|

1017.4 ± 91.4 |

1011.8 ± 174.0 |

1026.4 ± 156.6 |

902.6 ± 96.4 |

| Neutrophil (%) |

|

14.0 ± 2.4 |

15.3 ± 3.9 |

13.1 ± 3.1 |

13.3 ± 3.8 |

| LYMPH (%) |

|

79.2 ± 2.6 |

78.4 ± 4.9 |

80.3 ± 5.3 |

80.6 ± 3.7 |

| Monocyte (%) |

|

5.2 ± 1.0 |

4.9 ± 1.3 |

5.0 ± 2.3 |

4.6 ± 1.0 |

| Eosinophil (%) |

|

1.3 ± 0.5 |

1.2 ± 0.4 |

1.2 ± 0.5 |

1.2 ± 0.3 |

| Basophil (%) |

|

0.3 ± 0.1 |

0.3 ± 0.1 |

0.3 ± 0.2 |

0.2 ± 0.1 |

| PT (sec.) |

|

9.7 ± 0.2 |

9.6 ± 0.2 |

9.7 ± 0.1 |

9.6 ± 0.2 |

Table 9.

Serum biochemistry parameters in male and female rats treated with NTU 101 powder via gastric gavage for 90 consecutive daysa.

Table 9.

Serum biochemistry parameters in male and female rats treated with NTU 101 powder via gastric gavage for 90 consecutive daysa.

| |

|

Dose |

| |

|

Control |

Low Dose

(500 mg/kg) |

Medium dose

(1000 mg/kg) |

High dose

(2000 mg/kg) |

| Male |

|

|

|

|

|

| Glucose (mg/dL) |

|

242.5 ± 27.2 |

242.9 ± 51.3 |

229.5 ± 39.8 |

259.8 ± 51.3 |

| BUN (mg/dL) |

|

15.6 ± 2.1 |

14.1 ± 1.7 |

14.8 ± 1.1 |

15.4 ± 1.2 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) |

|

0.70 ± 0.07 |

0.67 ± 0.05 |

0.67 ± 0.05 |

0.68 ± 0.04 |

| AST (U/L) |

|

97.4 ± 21.4 |

83.1 ± 8.3 |

90.1 ± 18.5 |

111.7 ± 50.0 |

| ALT (U/L) |

|

44.2 ± 22.0 |

34.7 ± 4.3 |

36.5 ± 7.8 |

58.2 ± 42.8 |

| Total protein (g/dL) |

|

6.7 ± 0.3 |

6.9 ± 0.2 |

6.6 ± 0.2 |

6.8 ± 0.4 |

| Albumin (g/dL) |

|

4.6 ± 0.2 |

4.6 ± 0.1 |

4.5 ± 0.1 |

4.6 ± 0.2 |

| ALP (U/L) |

|

95.5 ± 21.0 |

93.0 ± 20.8 |

94.6 ± 21.7 |

105.9 ± 25.1 |

| γ-GT (U/L) |

|

<2.0 |

<2.0 |

<2.0 |

<2.0 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

|

67.4 ± 11.0 |

72.4 ± 13.3 |

61.9 ± 11.3 |

64.6 ± 12.2 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) |

|

49.8 ± 15.2 |

61.6 ± 26.4 |

47.1 ± 22.9 |

61.0 ± 28.5 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) |

|

12.3 ± 0.7 |

13.4 ± 0.3* |

13.1 ± 0.4* |

13.6 ± 0.6* |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) |

|

10.7 ± 0.8 |

10.3 ± 0.7 |

10.8 ± 0.9 |

11.7 ± 1.8 |

| Sodium (meq/L) |

|

145.5 ± 1.0 |

146.2 ± 1.2 |

146.1 ± 1.4 |

144.3 ± 3.0 |

| Potassium (meq/L) |

|

7.1 ± 0.9 |

6.7 ± 0.7 |

7.3 ± 1.3 |

8.0 ± 2.3 |

| Chloride (meq/L) |

|

102.6 ± 1.3 |

101.0 ± 1.4* |

101.9 ± 1.7 |

100.0 ± 0.9* |

| Globulin (g/dL) |

|

2.1 ± 0.2 |

2.2 ± 0.2 |

2.1 ± 0.2 |

2.2 ± 0.2 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) |

|

<0.04 |

<0.04 |

<0.04 |

<0.04 |

| Female |

|

|

| Glucose (mg/dL) |

|

206.6 ± 52.6 |

206.8 ± 44.5 |

183.5 ± 55.4 |

203.0 ± 71.6 |

| BUN (mg/dL) |

|

15.3 ± 1.5 |

15.0 ± 2.1 |

15.4 ± 1.2 |

16.4 ± 1.7 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) |

|

0.83 ± 0.05 |

0.77 ± 0.05* |

0.76 ± 0.05* |

0.77 ± 0.05* |

| AST (U/L) |

|

108.2 ± 38.0 |

130.4 ± 91.6 |

97.8 ± 26.5 |

116.1 ± 40.9 |

| ALT (U/L) |

|

36.9 ± 11.1 |

36.2 ± 15.2 |

37.2 ± 20.2 |

38.7 ± 12.7 |

| Total protein (g/dL) |

|

7.9 ± 0.4 |

7.8 ± 0.6 |

7.6 ± 0.5 |

7.8 ± 0.5 |

| Albumin (g/dL) |

|

6.0 ± 0.4 |

5.8 ± 0.5 |

5.7 ± 0.6 |

5.9 ± 0.5 |

| ALP (U/L) |

|

30.6 ± 7.8 |

32.7 ± 5.1 |

36.0 ± 11.2 |

29.2 ± 4.3 |

| γ-GT (U/L) |

|

<2.0 |

<2.0 |

<2.0 |

<2.0 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

|

80.0 ± 19.7 |

81.1 ± 9.0 |

70.2 ± 13.4 |

78.6 ± 15.2 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) |

|

43.2 ± 13.8 |

49.7 ± 23.0 |

32.0 ± 15.7 |

39.8 ± 18.7 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) |

|

13.4 ± 0.6 |

14.0 ± 0.5* |

13.7 ± 0.3 |

14.2 ± 0.6* |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) |

|

9.9 ± 0.8 |

10.3 ± 1.4 |

10.0 ± 1.2 |

10.3 ± 1.1 |

| Sodium (meq/L) |

|

145.0 ± 0.9 |

145.7 ± 1.3 |

145.6 ± 1.5 |

144.9 ± 1.4 |

| Potassium (meq/L) |

|

9.2 ± 1.3 |

8.7 ± 2.0 |

9.3 ± 1.7 |

9.0 ± 1.3 |