1. Introduction

Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms that provide health benefits to the host when administered in appropriate amounts, have gained significant attention in addressing gastrointestinal disorders (Hill et al., 2014). Among various probiotic strains, Bacillus clausii stands out as a promising agent, particularly for managing and preventing diarrhoea in both infants and adults. Its unique ability to tolerate harsh gastrointestinal environments and produce beneficial metabolites positions it as a vital contributor to gut health and microbial balance (Sanders et al., 2003; Acosta-Rodríguez et al., 2022).

The spore-forming capability of Bacillus clausii is a key factor in its resilience, enabling it to survive exposure to extreme conditions such as high temperatures, gastric juice, and bile salts (Cutting, 2011). Upon reaching the favourable environment of the intestines, these spores germinate into active bacterial cells, where they exert their beneficial effects. As a transient probiotic, B. clausii temporarily colonizes the intestines without permanently altering the composition of the gut microbiota (Sanders et al., 2018). B. clausii is commonly administered in the form of powders or liquid suspensions for therapeutic use for conditions such as malnutrition, immune deficiencies, or chronic gastrointestinal disorders, where recurring or chronic diarrhoea is prevalent. In such cases, B. clausii supports gut health by reducing the frequency and severity of diarrhea episodes. Its immunomodulatory properties are especially useful for managing diarrhea linked to immune dysfunction (Singhi & Kumar, 2016). By replenishing the gut with beneficial microbes, Bacillus clausii helps restore microbial equilibrium as these strains are characterized and distinguished by specific levels of resistance to a wide range of antibiotics (Marseglia et al., 2014).

Frequently, microorganisms in commercially available probiotics have been shown to carry some antibiotic resistance (Gueimonde et al., 2013). Therefore, these probiotic preparations are particularly advantageous when used alongside antibiotic therapy, as the probiotic can mitigate some of the negative impacts of antibiotics that have on the gut microbiota. Additionally, B. clausii produces antimicrobial peptides and enzymes that inhibit the proliferation of harmful bacteria, thereby reducing the risk of infections (Mazzeo et al., 2015).

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) offers a high-resolution approach for confirming microbial identity and detecting contamination. In this study, WGS was used to verify the purity of the Entromax® Bacillus clausii. Genomic analysis can confirm the strain’s identity and rule out the presence of other Bacillus species, ensuring the absence of contamination and supporting the product’s safety and authenticity (Didelot et al., 2012; Claesson et al., 2010).

Entromax® is a commercially available B. clausii spore suspension designed to treat imbalances in intestinal microbial flora. This article presents findings on the antimicrobial susceptibility of four strains of B. clausii spores in Entromax® and highlights the characteristics of B. clausii strains as an effective probiotic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Total Viable Count (TVC), Isolation, and Identification of Bacillus clausii

To determine the Total Viable Count (TVC) of Bacillus clausii, a homogeneous suspension from three independent batches of Entromax® (batch numbers A0NEY001, A0NEX066, and A0NEX070) was prepared and serially diluted using sterile 0.1% peptone water. Aliquots of 0.2 mL from 10⁷ and 10⁸ dilutions were plated onto nutrient agar using the spread plate technique. The plates were incubated in an inverted position at 37°C for 24–48 hours. Post-incubation, visible colonies were enumerated to calculate the TVC. This microbiological assessment follows internationally recognized methodologies and aligns with current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) and WHO guidelines for probiotic manufacturing.

Bacillus clausii spore suspension from Entromax® batch no. A0NEY001 was added to 100 ml of nutrient broth and incubated at 37 °C, 200 RPM for 18 hrs for enrichment. The grown culture was preserved and subsequently used for further studies.

2.2. Biochemical Characterization

2.2.1. Starch Hydrolysis

Starch agar plates were prepared using Luria Bertani (LB) agar with 1% soluble starch, followed by sterilization at 121 °C for 15 minutes. The active culture of Bacillus clausii of Entromax® was spot-inoculated at the center of the Petri plates in a circular pattern and incubated at 37 °C for 24 to 48 hours. After incubation, a few drops of Gram’s iodine were added to the plate, forming a blue or black complex with the starch. The presence of a clear zone of hydrolysis around the bacterial inoculation site indicates a positive result for starch degradation. An uninoculated starch agar plate served as the control (Sanni et al., 2002).

2.2.2. Casein Hydrolysis Activity

Casein agar plates were prepared by supplementing LB agar with 1% skim milk, followed by sterilization at 121 °C for 15 minutes. The active culture of Bacillus clausii of Entromax® was spot-inoculated at the center of the Petri plates in a circular pattern and incubated at 37 °C for 24 to 48 hours. The presence of a clear zone of hydrolysis around the bacterial inoculation site indicates a positive result for casein degradation. An uninoculated casein agar plate served as the control (Sanni et al., 2002).

2.2.3. Resistance to Osmotic Stress

The capacity for resistance to osmotic stress was assessed following the method described by Raj et al. (2023). Different concentrations of sodium chloride (0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%) were prepared in test tubes containing 10 mL of LB broth, followed by sterilization at 121 °C for 15 minutes. A 500 µL aliquot of an active culture of B. clausii of Entromax® was inoculated into the test tubes. The tubes were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours with shaking at 200 rpm in an orbital shaker. The growth was assessed by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm, with LB broth without NaCl serving as the control.

2.2.4. Tolerance to Simulated Gastric Juice

Gastric juice tolerance of the Bacillus clausii of Entromax® was assessed under different pH conditions as previously described (Ahire et al., 2021). Two millilitres of overnight-grown bacterial culture were centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 15 minutes. The resulting pellet was washed with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 300 µL of PBS. Subsequently, 100 µL of the resuspended culture was treated with artificial gastric juice (pepsin 3 g/L, sodium chloride 5 g/L) at pH 2.0 and pH 6.0 separately and incubated at 37 °C for 3 hours. Bacterial survival under different pH conditions was determined by plating on LB agar plates.

2.2.5. Bile Salt Tolerance

Bile salt tolerance was evaluated following the method described by Lenini et al. (2023). Overnight-grown culture of Bacillus clausii of Entromax® was inoculated into LB broth supplemented with 0%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.5%, and 1.0% bile salts (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Bile salt tolerance was assessed by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm after 24 and 48 hours of incubation. Uninoculated LB broth containing the respective concentrations of bile salts served as the control.

2.3. Molecular Characterization by the 16S Sequencing Method

Genomic DNA was extracted from the culture using the phenol: chloroform: isoamyl alcohol method. The purity of the extracted genomic DNA was assessed by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was performed using a PCR machine. The 20 µL PCR reaction mixture consisted of 10 µL of Takara (Japan) Pre-mix, 2 µL of universal forward primer 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′), 2 µL of universal reverse primer 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′), 4 µL of PCR-grade water, and 2 µL of template DNA. PCR amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 minutes, followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 minute, annealing at 50 °C for 1 minute, and extension at 72 °C for 2 minutes, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 minutes. The PCR product was verified by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and subsequently sequenced using Sanger sequencing. In this method, the amplified 16S rRNA gene fragments were subjected to cycle sequencing reactions using fluorescently labelled dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs) along with the same primers (27F and 1492R). The reaction products were purified to remove unincorporated dyes and salts before being analyzed using a capillary electrophoresis-based DNA sequencer. The bacterial culture of Entromax® was identified at the species level using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) from NCBI. The obtained sequences were aligned using MEGA software version 11.0 to construct phylogenetic trees, establish evolutionary relationships, and confirm taxonomic identification by comparing sequence similarity with reference strains in the databases.

2.4. Whole Genome Sequence

Whole-genome libraries were prepared following standard procedures, and sequencing was performed using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with shotgun sequencing.

Adapter sequences included:

P7 adapter read1 (AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTGAACTCCAGTCA)

P5 adapter read2 (AGATCGGAAGAGCGTCGTGTAGGGAAAGAGTGT)

The sample generated over 5GB of data, corresponding to more than 35 million reads, with a read length of 159 bases. Data processing involved quality filtering, adapter trimming, and removal of low-quality reads using established bioinformatics pipelines. Pre-processing of data included filtering for host contamination and low-complexity sequences. Taxonomic classification was performed using Kraken2 with a comprehensive reference database (Wood et al., 2019), followed by the construction of an Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) table. Whole-genome sequence comparisons were performed using BLAST to identify regions of high nucleotide similarity. The query genome was aligned against the reference database using default parameters.

2.5. In Silico Antibiotic Resistance Gene Identification

Following assembly, the contiguous sequences (contigs), which are continuous stretches of DNA formed by aligning overlapping sequencing reads, were analyzed to identify antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes. The ABRicate tool was used to screen the assembled contigs against the NCBI and ResFinder databases. To ensure the accuracy of AMR gene detection, quality control measures were applied at multiple stages. Read quality was assessed prior to assembly using FastQC, and low-quality reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic. Post-assembly, contig quality was evaluated using QUAST to verify the completeness and accuracy of genome reconstruction. The ABRicate results were further validated by cross-referencing with additional resistance gene databases when necessary.

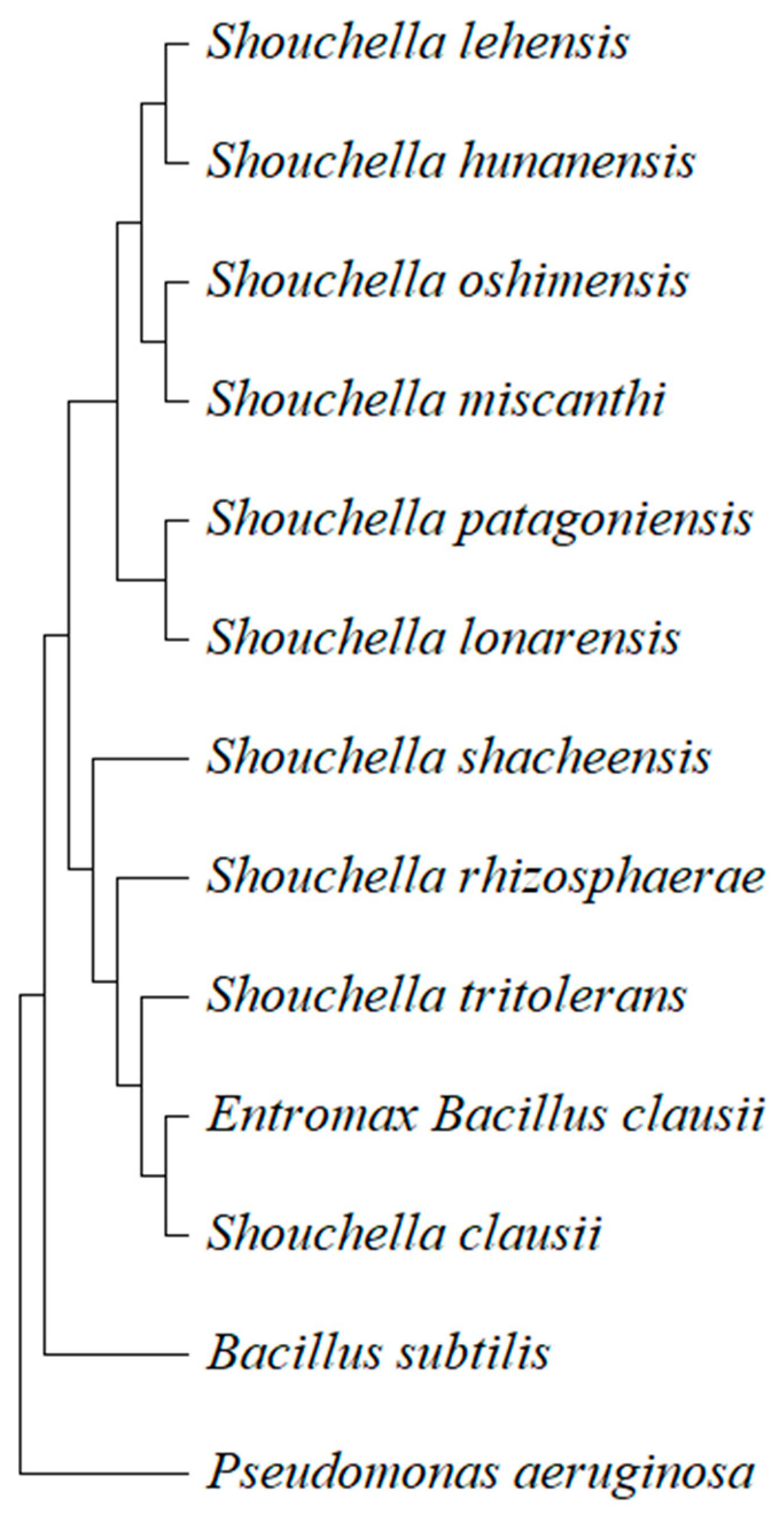

2.6. Evolutionary Relationships of Taxa

The evolutionary history was inferred using the 16S rRNA gene sequence following the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The phylogenetic tree was drawn to scale, with branch lengths representing the same units as the evolutionary distances used to construct the tree. Evolutionary distances were calculated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) method (Tamura et al., 2004), expressed as the number of base substitutions per site. This analysis included 13 nucleotide sequences, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa used as an outgroup to root the tree. Ambiguous positions were eliminated for each sequence pair using the pairwise deletion option. The final dataset comprised a total of 1,460 nucleotide positions. All evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA version 11 (Tamura et al., 2021).

2.7. Antibiotic Susceptibility Studies

The antibiotic susceptibility test was performed using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar (Nassar et al., 2019). A total of 200 µL of

Bacillus clausii of Entromax

® active culture was uniformly spread onto MH agar plates. Commercially available antibiotic discs (n = 46), each containing an appropriate concentration of antibiotics (

Table 2), were aseptically placed on the agar surface. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours, and the zones of inhibition were measured to assess antibiotic susceptibility. This allowed for the precise evaluation of strain’s resistance or sensitivity to various antibiotics.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Total Viable Count, Isolation of Probiotic Strains, and Morphological Characterization

Bacillus clausii was isolated from the spore suspension of Entromax®. Following isolation, the culture was subjected to morphological characterization to confirm its identity and observe specific features. The colonies were initially assessed based on their macroscopic characteristics, such as colony shape (irregular), margin (undulate), elevation (flat), surface texture (smooth), color (creamy white), and opacity (translucent). The Total Viable Count (TVC) of the tested Entromax® Bacillus clausii batches was determined to be 0.42 ± 0.2 billion CFU/mL, corresponding to approximately 2 billion CFU per 5 mL dose. The consistent colony growth on the selected dilution plates confirmed the accuracy of the dilution and plating process.

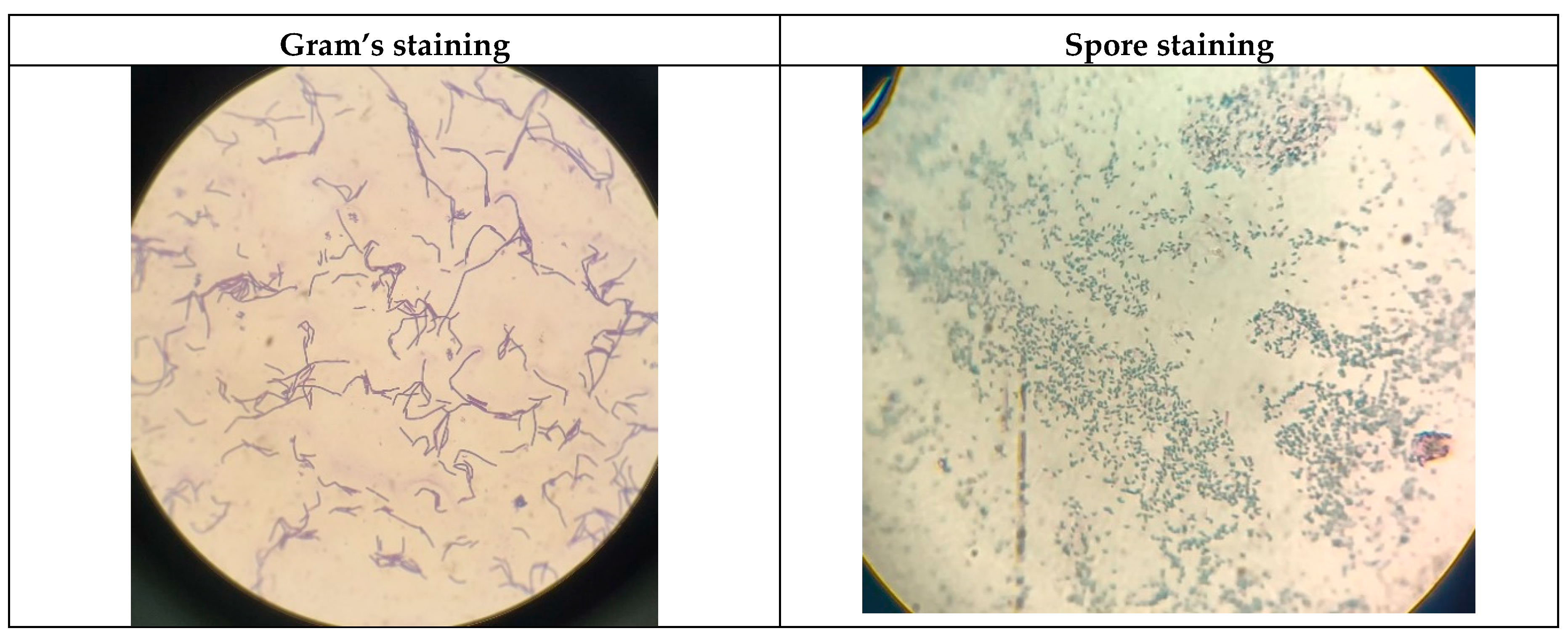

Microscopic examination was conducted using the Gram staining technique, which revealed that the culture was Gram-positive, exhibiting the characteristic rod-shaped morphology with the presence of endospores, typical of the

Bacillus genus (

Figure 1). Under high magnification, the cells appeared as single rods of varying lengths and were also observed forming short chains to long filamentous structures, depending on the growth stage. These dynamic arrangement patterns provided foundational evidence supporting the identification of the isolate as

Bacillus clausii, serving as a precursor for further biochemical, molecular, and probiotic characterization (Nielsen et al., 1995).

3.2. Biochemical Characterization

Bacillus clausii of Entromax

® was subjected to a series of biochemical assays to evaluate its probiotic potential, including tests for osmotic stress tolerance, enzymatic activities, bile salt tolerance, and gastric juice resistance. The results were compared with respective controls to validate the observed phenotypic traits (

Table 1).

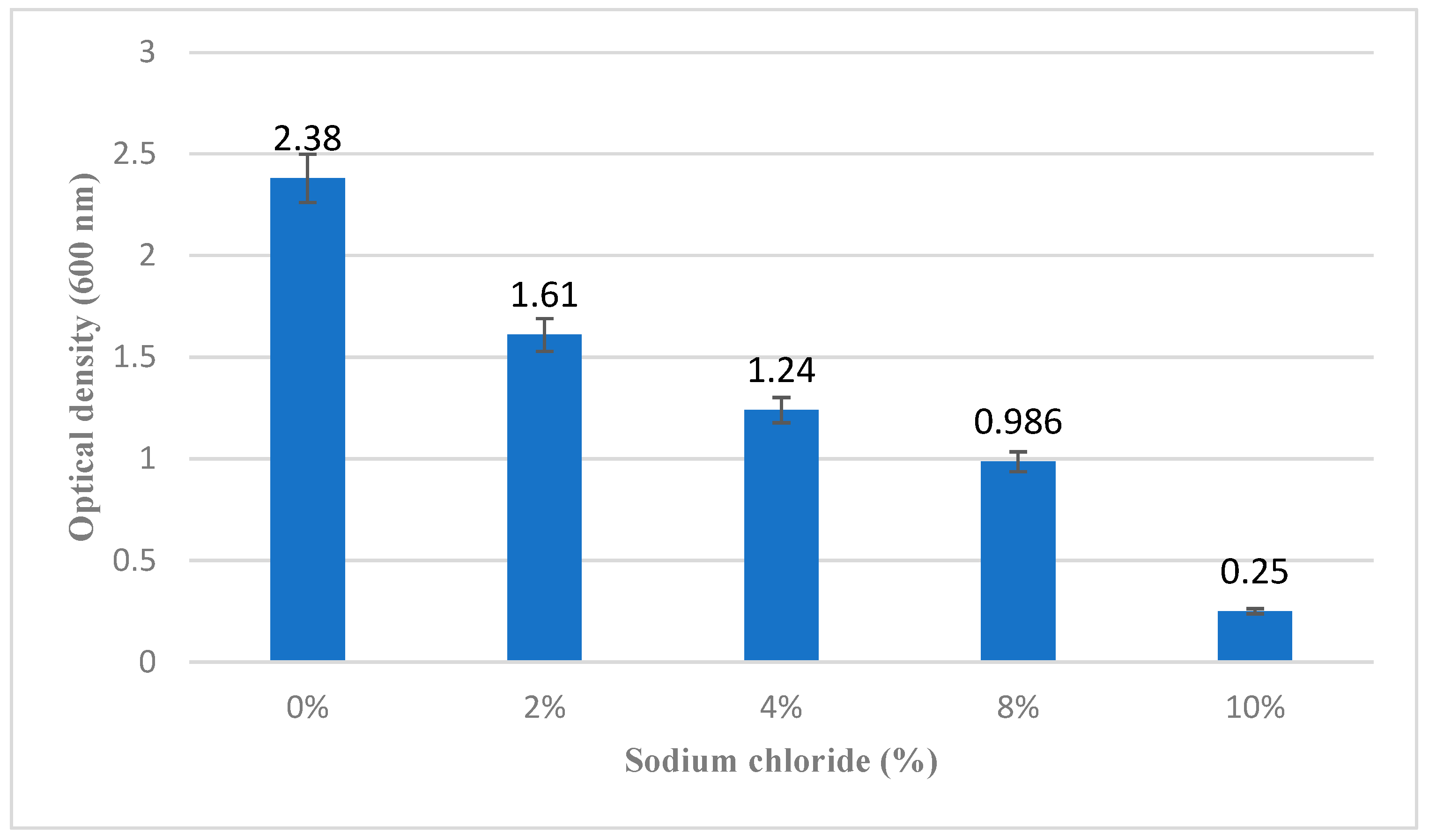

3.2.1. Osmotic Stress Tolerance

Bacillus clausii of Entromax

® demonstrated significant tolerance to osmotic stress, with consistent growth observed in LB broth supplemented with sodium chloride concentrations ranging from 2% to 8%. This indicates a strong tolerance to hyperosmotic conditions, which is an important characteristic for probiotic strains to survive in variable environments, including the human gastrointestinal tract. Growth was reduced at concentrations beyond 8% (

Figure 2), suggesting a threshold for salt tolerance.

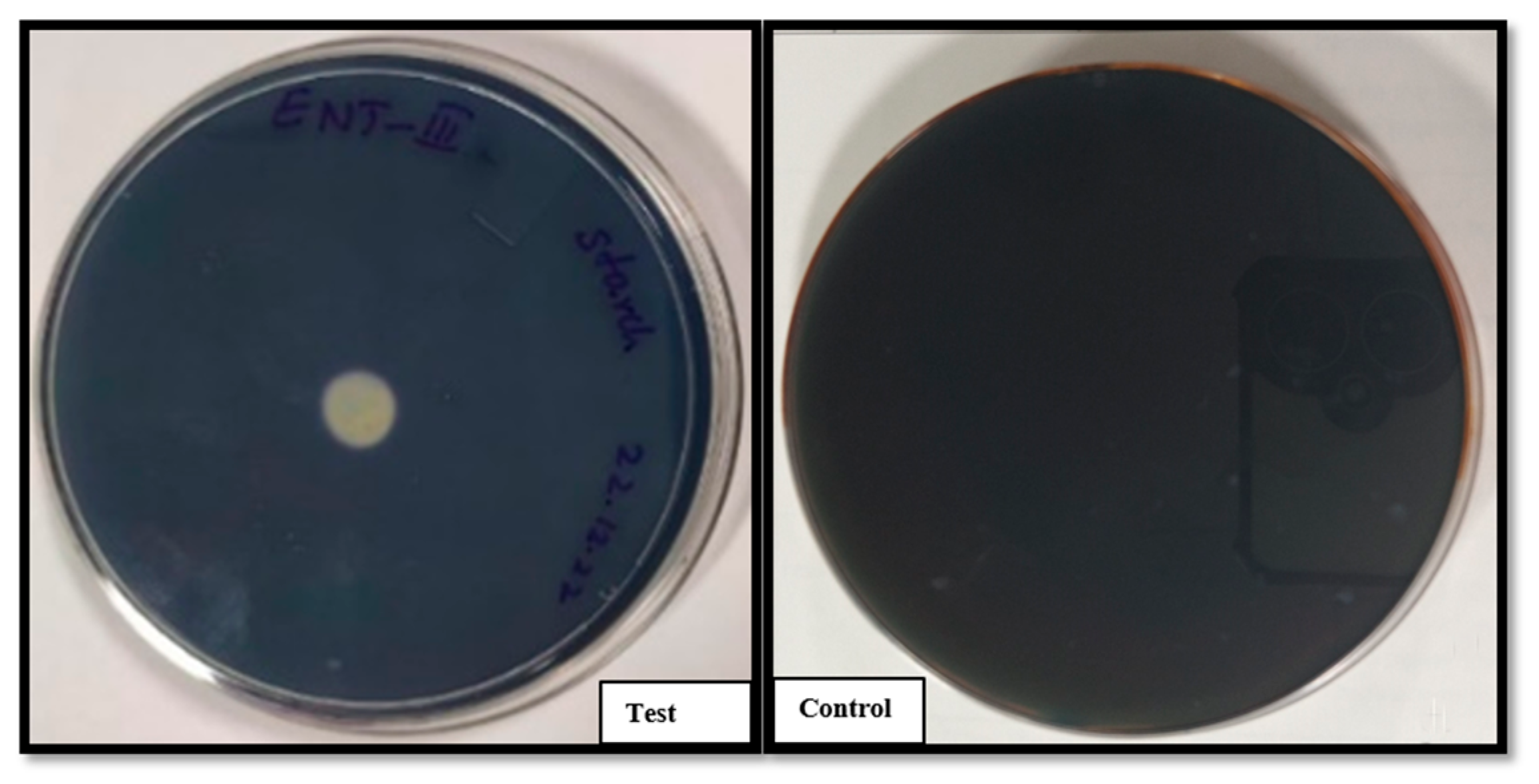

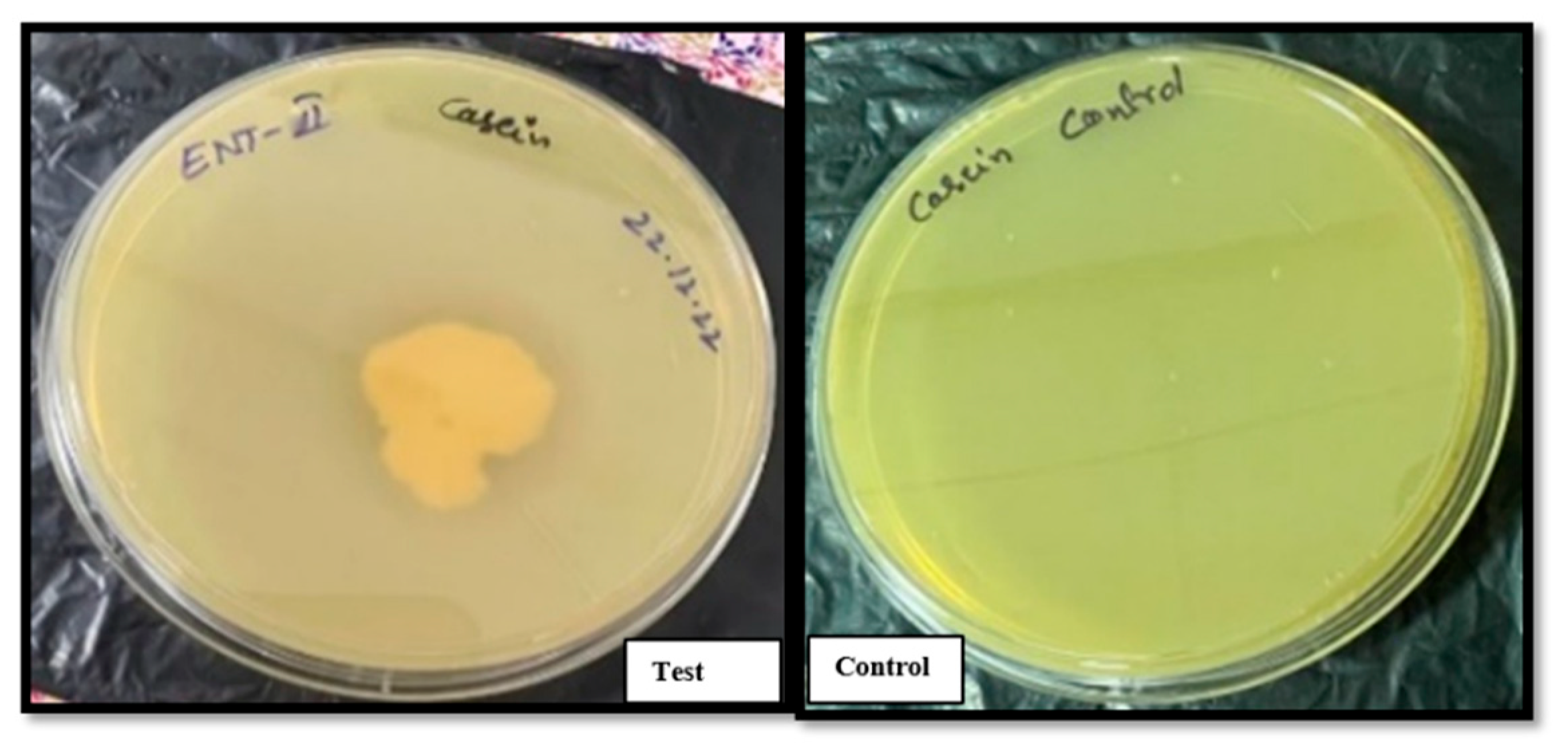

3.2.2. Enzymatic Activity: Starch and Casein Hydrolysis

Bacillus clausii of Entromax

® exhibited robust amylolytic and proteolytic activities, as evidenced by the formation of clear halo zones around the colonies on starch (

Figure 3) and casein agar plates (

Figure 4), respectively. This halo formation indicates effective hydrolysis of starch and casein, confirming the production of amylase and protease enzymes. These enzymatic activities are crucial for nutrient digestion and metabolic functionality in probiotic applications. The positive results were compared against control plates to ensure assay accuracy.

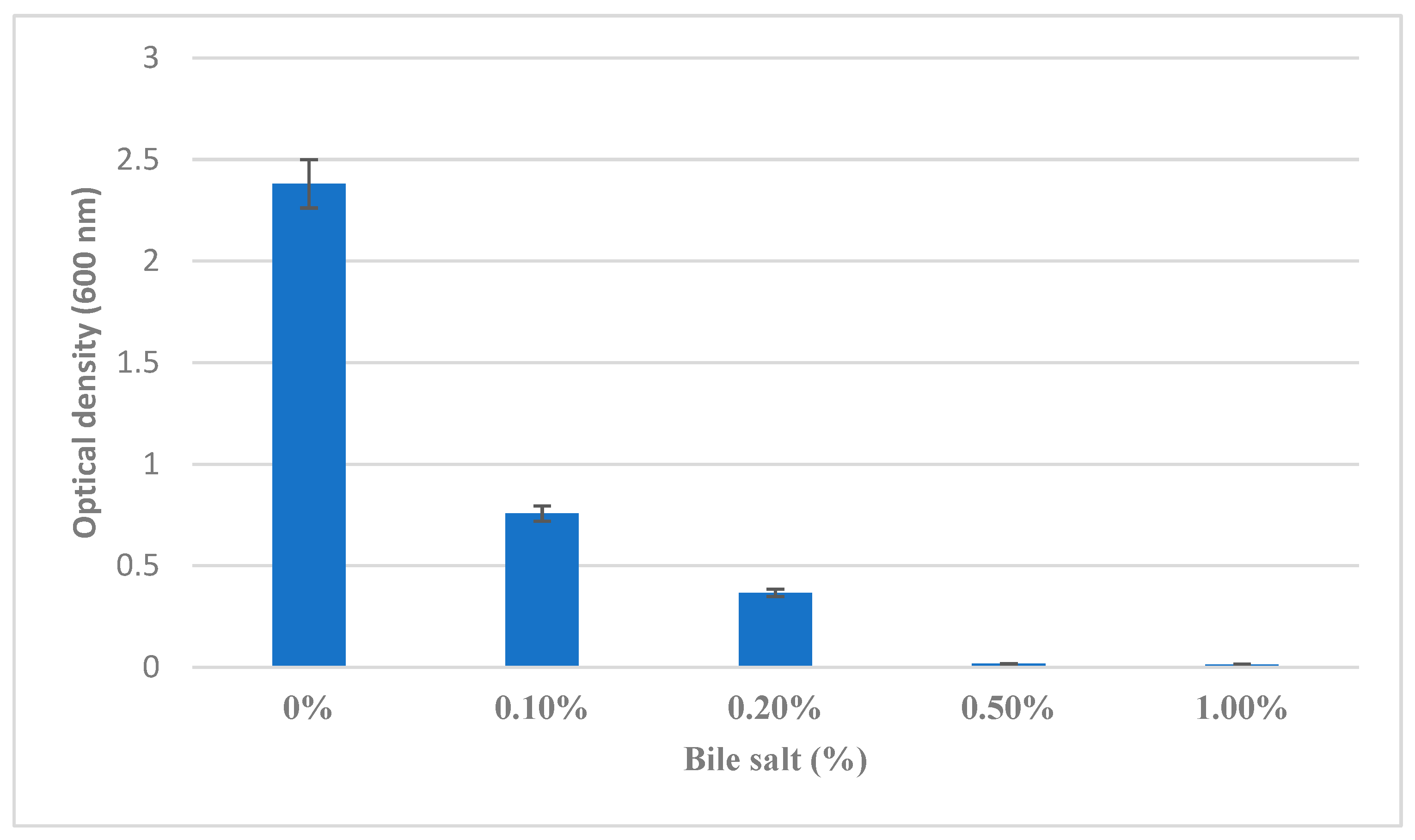

3.2.3. Bile Salt Tolerance

Bile salt tolerance, a key determinant of probiotic survivability in the small intestine, was assessed across varying concentrations. The

B. clausii demonstrated good growth in LB broth supplemented with 0% to 0.5% bile salts (

Figure 5), indicating effective tolerance to physiological bile concentrations typically encountered in the gastrointestinal tract. However, no growth was observed at 1.0% bile salt concentration, suggesting a threshold beyond which bile salts exert inhibitory effects on bacterial viability and growth.

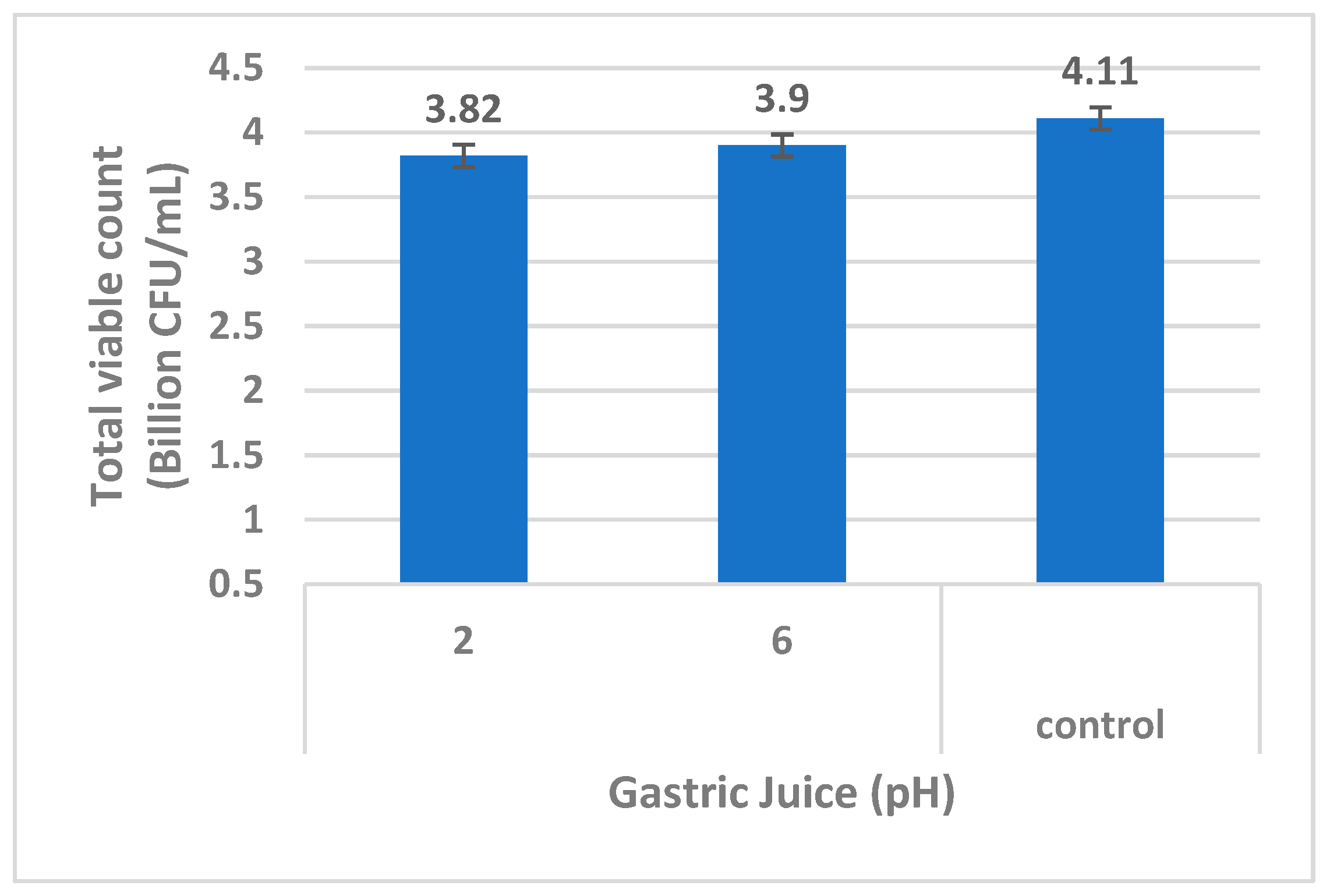

3.2.4. Gastric Juice Resistance Test

The ability of the

B. clausii of Entromax

® to withstand gastric juice conditions was evaluated at pH 2.0 (mimicking stomach acidity) and pH 6.0 (near-neutral conditions). After exposure, the culture was serially diluted and plated on LB agar. The presence of viable colonies on both pH conditions confirmed the strains’ resistance to acidic environments, particularly at pH 2.0, demonstrating their potential to survive the harsh gastric environment

in vitro (

Figure 6). This characteristic is vital for ensuring the strains’ passage through the stomach to reach the intestines, where they exert probiotic effects (Sundararaman

et al., 2021).

3.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility

The antibiotic sensitivity of

B. clausii of Entromax

® was assessed using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method, and the results were interpreted based on the zone of inhibition (ZOI) measurements, classifying the culture as either susceptible (S) or resistant (R). The sensitivity levels towards different antibiotics were varied in terms of ZOI diameters; however, the culture showed resistance to chloramphenicol, rifampicin, streptomycin, and tetracycline, as indicated by the absence or minimal formation of inhibition zones around the respective antibiotic discs. Additionally, the strain exhibited consistent resistance to cephaloridine, erythromycin, and metronidazole.

Bacillus clausii showed intermediate or partial resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics, including β-lactams (Amoxiclav, Cefalexin, Cefazolin, Piperacillin), quinolones (Nalidixic acid, Ofloxacin), aminoglycosides (Neomycin), tetracyclines (Oxytetracycline), streptogramins (Quinupristin), and ketolides (Telithromycin) (

Table 2). This distinct antibiotic resistance profile highlights both strain-specific resistance mechanisms and a common pattern of susceptibility, which is crucial for evaluating the safety and clinical applicability of this probiotic strain. The observed resistance may enhance the strains' survival potential in antibiotic-rich environments, while their susceptibility to a broad spectrum of antibiotics ensures effective management if required, thereby supporting their probiotic efficacy and safety for therapeutic applications.

Table 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility test results.

Table 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility test results.

| S. No |

Antibiotic |

Concentration (µg/disk) |

Zone of inhibition

(mm)

|

Result |

| 1 |

Amikacin |

30 |

30 |

Susceptible |

| 2 |

Amoxycillin |

25 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 3 |

Amoxiclav |

30 |

17 |

Partial Resistance |

| 4 |

Ampicillin |

10 |

11 |

Resistant |

| 5 |

Azithromycin |

15 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 6 |

Cefaclor |

30 |

31 |

Susceptible |

| 7 |

Cefalexin |

30 |

14 |

Partial Resistance |

| 8 |

Cefazolin |

30 |

14 |

Partial Resistance |

| 9 |

Cefepime |

30 |

12 |

Resistant |

| 10 |

Cefotaxime |

30 |

12 |

Resistant |

| 11 |

Cefprozil |

30 |

30 |

Susceptible |

| 12 |

Ceftriaxone |

30 |

12 |

Resistant |

| 13 |

Cefuroxime |

30 |

12 |

Resistant |

| 14 |

Cephaloridine |

10 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 15 |

Chloramphenicol |

50 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 16 |

Ciprofloxacin |

5 |

20 |

Susceptible |

| 17 |

Clarithromycin |

15 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 18 |

Clindamycin |

10 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 19 |

Doxycycline |

30 |

22 |

Susceptible |

| 20 |

Erythromycin |

30 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 21 |

Gentamicin |

50 |

27 |

Susceptible |

| 22 |

Imipenem |

10 |

28 |

Susceptible |

| 23 |

Kanamycin |

30 |

12 |

Resistant |

| 24 |

Levofloxacin |

5 |

28 |

Susceptible |

| 25 |

Lincomycin |

15 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 26 |

Linezolid |

30 |

27 |

Susceptible |

| 27 |

Meropenem |

10 |

23 |

Susceptible |

| 28 |

Metronidazole |

50 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 29 |

Minocycline |

30 |

18 |

Susceptible |

| 30 |

Nalidixic acid |

30 |

16 |

Partial Resistance |

| 31 |

Neomycin |

30 |

14 |

Partial Resistance |

| 32 |

Norfloxacin |

10 |

28 |

Susceptible |

| 33 |

Ofloxacin |

2 |

15 |

Partial Resistance |

| 34 |

Oxacillin |

5 |

11 |

Resistant |

| 35 |

Oxytetracycline |

30 |

14 |

Partial Resistance |

| 36 |

Piperacillin |

100 |

16 |

Partial Resistance |

| 37 |

Quinupristin |

15 |

16 |

Partial Resistance |

| 38 |

Rifampicin |

30 |

11 |

Resistant |

| 39 |

Rifampin |

15 |

12 |

Resistant |

| 40 |

Spiramycin |

100 |

0 |

Resistant |

| 41 |

Streptomycin |

25 |

11 |

Resistant |

| 42 |

Teicoplanin |

30 |

18 |

Susceptible |

| 43 |

Telithromycin |

15 |

16 |

Partial Resistance |

| 44 |

Tetracycline |

10 |

12 |

Resistant |

| 45 |

Tigecycline |

15 |

25 |

Susceptible |

| 46 |

Vancomycin |

30 |

24 |

Susceptible |

3.4. Molecular characterization

3.4.1. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

The 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis of the isolated strain revealed a high degree of sequence similarity with

Shouchella clausii, with a similarity percentage exceeding 99%, confirming its taxonomic identity, specifically, showing a close phylogenetic relationship with

Bacillus clausii exhibiting 99.8% sequence similarity (

Table 3). The high sequence similarity observed supports its classification within the

Shouchella clausii clade formerly known as

Bacillus clausii, providing a strong molecular basis for its identification and subsequent phylogenetic analysis (Joshi et al., 2021).

3.4.2. Whole Genome-Based Taxonomical Classification

Taxonomic classification based on the genomic analysis confirmed that the organism belongs to the Kingdom

Bacteria. At the phylum level, it was classified under

Bacillota. Further classification revealed that the organism belongs to the class

Bacilli and the order

Bacillales. Within this order, the family

Bacillaceae was identified. At the genus level,

Shouchella was confirmed, with

Shouchella clausii identified as the species. These results provide a precise taxonomic placement of

Shouchella clausii based on its genomic data, supporting its distinct classification within the

Bacillaceae family. The whole genome BLAST analysis showed that the microbial culture isolated from Entromax

® is 100% similar to

Shouchella clausii (

Table 4).

3.4.3. Evolutionary Relationships of Taxa

The phylogenetic analysis of the

B. clausii of Entromax

® showed that it is closely related to the genus

Souchella (reclassified from

Alkalihalobacillus sp.) and forms a clade with

Souchella clausii (

Figure 7) (Patel & Gupta, 2020).

3.4.4. Antibiotic Resistance Genes

The genomic analysis of the B. clausii of Entromax® identified a diverse array of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) associated with multiple antibiotic classes. These ARGs exhibit varying levels of sequence identity and coverage, reflecting both highly conserved and moderately divergent resistance elements. Mapping these genes to established resistance databases confirmed their functional roles in antimicrobial resistance. B. clausii of Entromax® carried genes linked to resistance against β-lactams (blaBCL-1, 100% similarity), aminoglycosides (ant(4')-Ib, 100%; aph(6)-Id, 98.86%), macrolides (erm(34), 95.47%; clbB, 100%), chloramphenicol (catA10, 100%), and rifampicin (rphC, 81.43%). The high sequence similarity observed (predominantly 100%) suggests strong conservation of key resistance genes across strains, supporting the presence of a robust multidrug resistance profile. These genomic findings align with phenotypic resistance patterns observed in susceptibility tests. The table below summarizes the detected antibiotic resistance genes, including their sequence identity percentages, associated resistance functions, and corresponding database accession numbers.

Table 5.

Antibiotic resistance gene associated with B. clausii of Entromax®.

Table 5.

Antibiotic resistance gene associated with B. clausii of Entromax®.

| Resistance/ Function |

Gene |

Similarity

(%)

|

DATABASE |

Accession No |

| Lincosamide, Macrolide, Streptogramin |

clbB |

100 |

NCBI |

NG_062348.1 |

| Beta-Lactam |

blaBCL-1 |

100 |

NCBI |

NG_051318.1 |

| Amikacin, Kanamycin, Tobramycin |

ant(4')-Ib |

100 |

NCBI |

NG_047392.1 |

| Tetracycline |

tet 42 |

82.9 |

NCBI |

NG_048143.1 |

| Streptomycin |

aph(3)-Id |

99.64 |

NCBI |

NG_047465.1 |

| Rifampicin |

rphC |

81.43 |

NCBI |

NG_063825.1 |

| Macrolide |

erm(34) |

95.47 |

NCBI |

NG_047777.1 |

| Chloramphenicol |

catA10 |

100 |

NCBI |

NG_060532.1 |

4. Conclusion

This study offers detailed insights into the probiotic potential, stress tolerance, and antibiotic resistance profiles of Shouchella clausii (Bacillus clausii) isolated from Entromax®. The strain demonstrates robust adaptability to gastrointestinal environments, possesses enzymatic activities that support host health, and exhibits a complex antibiotic resistance pattern. These attributes emphasize their suitability for probiotic applications in managing antibiotic-associated gastrointestinal dysbiosis. However, further in vivo studies are essential to confirm their probiotic efficacy and ensure clinical efficacy.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific funding from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Data Availability

The genome sequence of the isolated strain has been submitted to the GenBank database NCBI with biosample and Bioproject with accession numbers BioProject PRJNA1248863, Biosample SAMN47869146.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to GenepowerX for providing the genome sequencing and analysis. Mankind Pharma and Virchow Biotech Pvt Ltd., are acknowledged for their invaluable inputs, cooperation, and help to this study. We deeply appreciate their generosity in providing the samples for analysis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors confirm that this article's content has no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahire, J. J., Kashikar, M. S., & Madempudi, R. S. (2021). Comparative accounts of probiotic properties of spore and vegetative cells of Bacillus clausii UBBC07 and in silico analysis of probiotic function. 3 Biotech, 11(3), 116. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Rodríguez-Bueno, C.P., Abreu y Abreu, A.T., Guarner, F. et al. (2022) Bacillus clausii for Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Narrative Literature Review. Adv Ther 39, 4854–4874. [CrossRef]

- Casula, G., & Cutting, S. M. (2002). Bacillus probiotics: Spore germination in the gastrointestinal tract. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 68(5), 2344–2352. [CrossRef]

- Claesson MJ, et al. (2010). Comparative analysis of pyrosequencing and a phylogenetic microarray for exploring microbial community structures in the human distal intestine. PLoS One, 5(1), e6669. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutting, S. M. (2011). Bacillus probiotics. Food Microbiology, 28(2), 214-220. [CrossRef]

- Didelot X, Bowden R, Wilson DJ, Peto TEA, Crook DW. (2012). Transforming clinical microbiology with bacterial genome sequencing. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13(9), 601–612. [CrossRef]

- Gueimonde M, Sanchez B, de Los Reyes-Gavilan CG, Margolles A. Antibiotic resistance in probiotic bacteria. Front Microbiol 2013; 4: 202. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V., & Garg, R. (2009). Probiotics in gastrointestinal diseases. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 24(6), 1070-1080.

- Hill, C., Guarner, F., Reid, G. et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 11, 506–514. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, A., Thite, S., Karodi, P., Joseph, N., and Lodha, T. "Alkalihalobacterium elongatum gen. nov. sp. nov.: An antibiotic-producing bacterium isolated from Lonar Lake and reclassification of the genus Alkalihalobacillus into seven novel genera." Front. Microbiol. (2021) 12:722369. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leñini, C., Rodriguez Ayala, F., Goñi, A. J., Rateni, L., Nakamura, A., & Grau, R. R. (2023). Probiotic properties of Bacillus subtilis DG101 isolated from the traditional Japanese fermented food nattō. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14, 1253480. [CrossRef]

- Marseglia, G. L., et al. (2014). Role of probiotics in pediatric gastrointestinal diseases. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 40, 58.

- Mazzeo, M., et al. (2015). Antimicrobial properties of Bacillus clausii strains. Current Microbiology, 71(1), 66-72.

- Nassar, M. S., Hazzah, W. A., & Bakr, W. M. (2019). Evaluation of antibiotic susceptibility test results: how guilty a laboratory could be?. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 94, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P., Fritze, D., & Priest, F. G. (1995). Phenetic diversity of alkaliphilic Bacillus strains: proposal for nine new species. Microbiology, 141(7), 1745-1761. [CrossRef]

- Patel S, Gupta RS. "A phylogenomic and comparative genomic framework for resolving the polyphyly of the genus Bacillus: Proposal for six new genera of Bacillus species, Peribacillus gen. nov., Cytobacillus gen. nov., Mesobacillus gen. nov., Neobacillus gen. nov., Metabacillus gen. nov. and Alkalihalobacillus gen. nov." Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. (2020) 70(1):406-438. [CrossRef]

- Raj, C. D., Suryavanshi, M. V., Kandaswamy, S., Ramasamy, K. P., & James, R. A. (2023). Whole genome sequence analysis and in-vitro probiotic characterization of Bacillus velezensis FCW2 MCC4686 from spontaneously fermented coconut water. Genomics, 115(4), 110637. [CrossRef]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987 Jul;4(4):406-25.

- Sanni, A. I., Morlon-Guyot, J., & Guyot, J. P. (2002). New efficient amylase-producing strains of Lactobacillus plantarum and L. fermentum isolated from different Nigerian traditional fermented foods. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 72(1-2), 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M. E., et al. (2018). Probiotic use in at-risk populations. Journal of the American Medical Association, 320(15), 1535-1543. [CrossRef]

- Singhi, S., & Kumar, R. (2016). Probiotics in critically ill children. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 19(2), 128-134.

- Sundararaman, A., Bansal, K., Sidhic, J. et al. Genome of Bifidobacterium longum NCIM 5672 provides insights into its acid-tolerance mechanism and probiotic properties. Arch Microbiol 203, 6109–6118 (2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Jul 27;101(30):11030-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021 Jun 25;38(7):3022-3027. [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol 20, 257 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wright MH, Adelskov J, Greene AC. Bacterial DNA extraction using individual enzymes and phenol/chloroform separation. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2017;18(2). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).