1. Introduction

Escherichia coli (

E. coli) is one of the most important pathogens causing diarrhea in neonatal and weaned piglets. Piglet diarrhea leads to substantial economic losses in the swine industry due to increased morbidity and mortality, reduced growth performance, and higher veterinary costs [

1]. Prevention is generally more effective than treatment, yet traditional control strategies have relied heavily on antibiotics [

2]. This dependence has raised serious concerns about antibiotic residues in meat and the global spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [

3]. As regulatory authorities and consumers increasingly demand reductions in antibiotic use, there is a growing need for sustainable alternatives that can maintain animal health and productivity without contributing to AMR [

4]. Several alternative approaches have been proposed, including organic acids, copper sulfate, zinc oxide, prebiotics, herbal supplements, and probiotics. Among these, probiotics have attracted particular attention for their ability to promote intestinal health, reduce the incidence and severity of enteric diseases, and support growth performance in pigs, while reducing the need for antibiotics [

5]. Probiotic supplementation has been shown to modulate the gut microbiota, enhance immune function, and improve nutrient utilization in swine. Recent studies have confirmed that probiotics can serve as viable antibiotic alternatives for preventing bacterial diarrhea in piglets, with benefits extending to improved feed efficiency and overall health [

6]. Moreover, probiotic use aligns with the One Health framework by mitigating AMR risks at the animal–human–environment interface [

7].

At birth, the gastrointestinal tract of animals is sterile but rapidly colonized by microorganisms from the mother and the surrounding environment. This early colonization plays a critical role in the development of the digestive system, metabolic functions, and immune competence of neonates [

8]. The gut microbiota’s composition is shaped by factors such as delivery mode, maternal microbiota, diet, and environmental exposure [

9]. In pigs, a diverse and balanced gut microbiota supports resistance to pathogens, adaptation to dietary changes, and improved physiological functions [

10]. The porcine gastrointestinal tract is anatomically compartmentalized, with the small intestine—particularly the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum—being the main site for nutrient digestion and absorption. Maintaining a healthy microbiota in these regions is critical for growth and disease prevention, especially in intensive swine production systems.

Probiotics are defined as live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer health benefits to the host by improving the microbial balance in the gastrointestinal tract (FAO/WHO, 2002). Effective probiotics must survive exposure to gastric acid and bile salts, adhere to intestinal epithelial cells, and exhibit antagonistic effects against pathogens [

11]. In swine production, probiotics are used both to support growth and to prevent colonization by enteric pathogens such as Salmonella spp.,

E. coli, and Clostridium perfringens [

12]. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are among the most widely studied probiotic groups due to their non-pathogenic nature, acid and bile tolerance, and ability to produce antimicrobial substances such as organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins [

13]. These antimicrobial compounds are considered safe and, in some cases, have been linked to reduced pathogen load and improved gut health in pigs [

14].

The probiotic properties of LAB are highly strain-specific, even among isolates belonging to the same species [

15]. Only a limited number of strains with strong acid and bile tolerance, adhesion ability, and potent antimicrobial activity have been identified, and their functional properties often vary depending on the host and environmental context. Recent advances in microbiome analysis and targeted isolation techniques have enabled the discovery of novel LAB strains from indigenous pig breeds and different rearing environments, some of which show promise for improving gut integrity, modulating immunity, and reducing pathogenic

E. coli colonization [

16]. However, further research is needed to characterize these strains comprehensively and assess their potential as antibiotic alternatives in commercial pig production.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to isolate and characterize LAB with probiotic potential from fecal samples of pigs at different ages raised without antibiotics or probiotics. The focus was on identifying strains that could survive under gastrointestinal conditions, exhibit inhibitory activity against pathogenic E. coli, and demonstrate other desirable probiotic traits. The findings of this work provide a basis for selecting promising LAB strains for development as feed additives to promote swine gut health, reduce reliance on antibiotics, and contribute to the global effort to mitigate AMR in livestock production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

Since fecal samples were collected without handling or restraining the animals, specific approval for animal use was not required. However, the experimental procedures involved the use of microbial isolates. Therefore, all microbiological work was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) of Chiang Mai University (Approval No. CMUIBC A-0763004).

2.2. Sample Collection

The study population comprised suckling piglets aged 7–30 days. The required sample size was estimated based on an assumed Lactobacillus detection prevalence of 50%, a total piglet population of 2,800, an effect size of 0.3, statistical power (1 – β) of 0.98, and an alpha error probability of 0.02, using G*Power software (version 3.1). The minimum calculated sample size was 40; therefore, 42 fecal samples were collected to ensure adequate statistical power. Samples were obtained from a commercial pig farm in Lamphun province where no antibiotics or probiotics had been used. To maximize diversity, no more than five samples were taken from any single farrowing pen. Freshly voided feces with normal consistency and yellow to brown coloration were collected from the pen floor, placed in sterile 5 mL microcentrifuge tubes (≥2 g each), and transported at 4 °C to the laboratory for processing.

2.3. Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB)

One gram of fecal sample was homogenized in 9 mL of 0.85% sterile saline and serially diluted (10

−4 to 10

−8). Aliquots (100 µL) were spread onto de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) agar supplemented with 0.5% CaCO

3. Plates were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 48 h. Colonies producing clear zones were subcultured in MRS broth to obtain pure isolates. Gram-positive, non-spore-forming bacteria were retained and tested for catalase activity; only catalase-negative isolates were preserved at –20 °C in MRS broth with 20% (v/v) sterile glycerol [

17].

2.4. Evaluation of Probiotic Properties

2.4.1. Acid Tolerance

Colonies grown on MRS agar were suspended in 5 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) and adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard (~1.5 × 10

8 CFU/mL). One milliliter of suspension was mixed with 9 mL sterile PBS adjusted to pH 2.0 or pH 3.1 using 1 N HCl. The mixtures were vortexed for 10 s and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Viable cell counts before and after incubation were determined by plate counting on MRS agar. Acid tolerance was expressed as the reduction in bacterial counts (log CFU/mL) compared with the initial value [

17].

2.4.2. Bile Salt Tolerance

Bacterial suspensions prepared as above were inoculated (1 mL) into 9 mL MRS broth supplemented with 0.3%, 0.5%, or 1% (w/v) bile salts (Sigma-Aldrich). Control cultures contained no bile salts. Tubes were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 24 h. Viable cell counts were determined at 0 and 24 h, and tolerance was evaluated based on survival relative to controls. Each strain was tested in duplicate [

18].

2.4.3. Adhesion Ability to Intestinal Epithelium (Surface Hydrophobicity)

Adhesion potential was assessed by the microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons (MATH) method. Bacteria grown on MRS agar were suspended in 5 mL PBS (pH 7.2) and adjusted to 6.0 McFarland standard. Optical density at 600 nm (OD

600) was adjusted to 0.6. Three milliliters of suspension was mixed with 1 mL of xylene in a glass tube, vortexed for 90 s, and left at room temperature for 30 min to allow phase separation. The aqueous phase was carefully removed, and OD

600 was measured again. Surface hydrophobicity (%H) was calculated as:

Controls consisted of PBS and xylene without bacteria. All assays were performed in duplicate [

19].

2.4.4. Hemolytic Activity

For safety evaluation, isolates were streaked on tryptic soy agar (TSA) supplemented with 5% (w/v) sheep blood and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Hemolysis type was determined visually: β-hemolysis (clear zone), α-hemolysis (green/brown discoloration), and γ-hemolysis (no change). Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 was used as a β-hemolysis positive [

20].

2.4.5. Antimicrobial Activity Against E. coli and S. aureus ATCC 6538

The agar well diffusion method was used. LAB cultures grown in MRS broth at 37 °C for 24 h were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 5 min, and supernatants were filtered through 0.45 µm membranes to obtain cell-free supernatants (CFS). Indicator strains—pathogenic

E. coli (from diarrheic piglets) and

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538—were adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard in PBS and spread onto nutrient agar plates. Wells (7 mm) were bored aseptically, and 80 µL CFS was added per well. Lactic acid (2% v/v) served as the positive control. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and inhibition zones were measured in millimeters. All tests were performed in duplicate [

21].

2.5. Data Interpretation

Probiotic Properties

Acid Tolerance

Survival at acidic pH was assessed by comparing bacterial counts (log CFU/mL) before and after incubation at pH 2.0 and pH 3.1. A reduction of less than 1 log CFU/mL at pH 3.1 was considered acceptable for acid tolerance [

22].

Bile Salt Tolerance

Bacterial counts (log CFU/mL) at 0 h and 24 h in MRS broth containing bile salts were compared. Strains were classified as tolerant if no significant reduction in viable counts was observed over the incubation period.

Surface Adhesion Ability

Adhesion potential was expressed as surface hydrophobicity (%H) calculated by the MATH assay. Higher %H values indicated stronger cell surface adhesion capabilities.

Hemolytic Activity

Hemolysis was classified into three types: β-hemolysis, indicating complete lysis of red blood cells and the presence of a clear zone around the colony; α-hemolysis, representing partial lysis with a green or brown discoloration surrounding the colony; and γ-hemolysis, showing no lysis or visible change in the medium. According to safety criteria for probiotic use, LAB strains exhibiting α- or β-hemolysis were considered unsuitable, whereas only γ-hemolytic strains were deemed acceptable [

23].

Antimicrobial Activity Against E. coli and S. aureus ATCC 6538

The antimicrobial potential of the cell-free supernatants (CFS) was assessed by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zones against

Escherichia coli and

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538. The results were interpreted according to the criteria summarized in

Table 1. This approach allowed for a comparative evaluation of the inhibitory effects of different CFS preparations on the selected pathogenic strains.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Means and standard deviations were calculated where appropriate to summarize the results.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) from Swine Feces

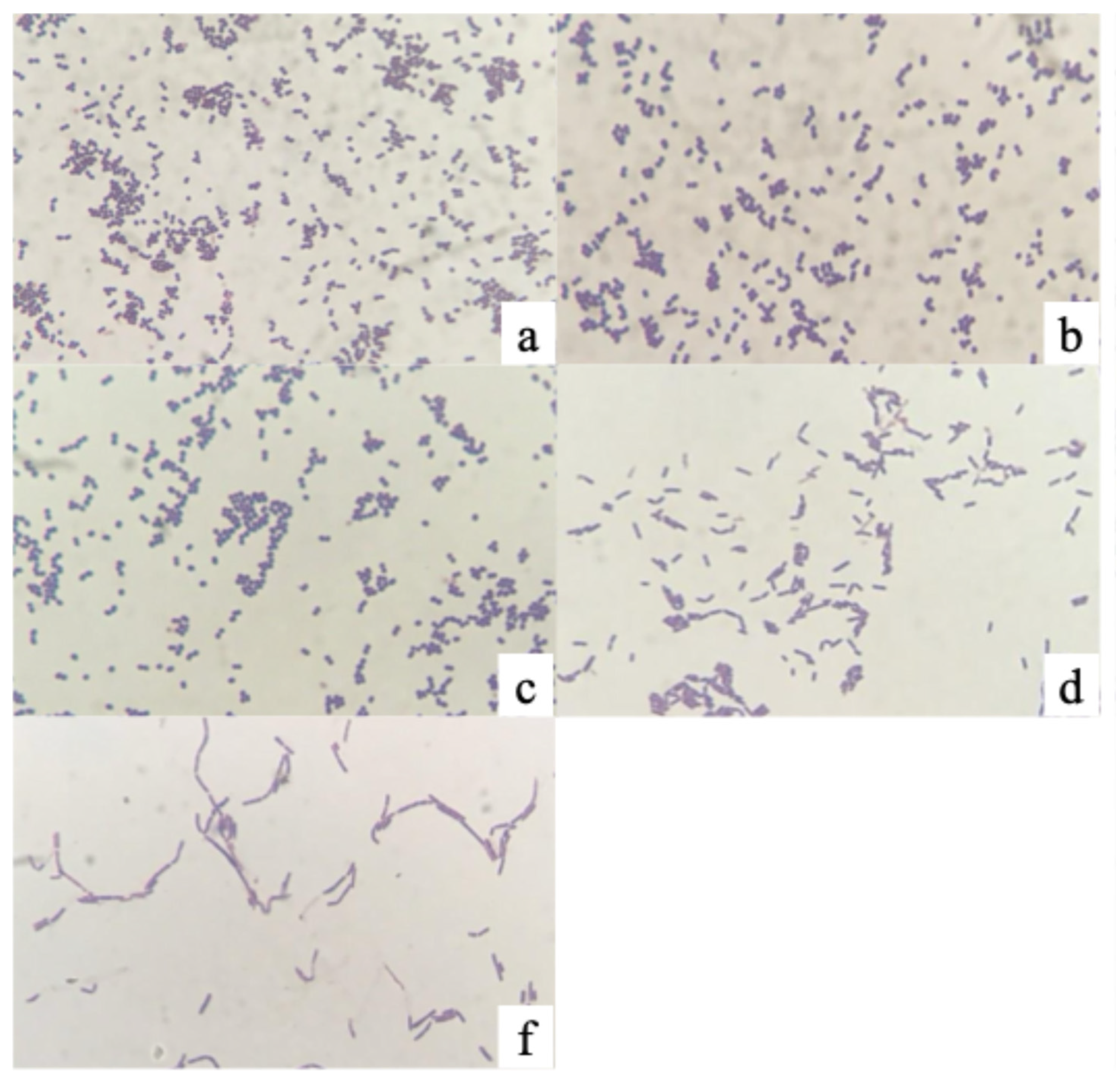

From 42 individual fecal samples collected from pigs of different ages, a total of 318 bacterial colonies producing clear zones on MRS agar supplemented with 0.5% CaCO3 under anaerobic incubation at 37 °C for 48 h were initially obtained. These colonies were preliminarily considered as potential lactic acid bacteria. Gram staining revealed that 296 isolates were Gram-positive, of which 146 were rod-shaped (bacilli), 136 were cocci, and 14 were coccobacilli. Nineteen isolates were identified as yeasts based on morphology, and three isolates could not be maintained during subculturing; both groups were excluded from further analysis.

Catalase testing of the 296 Gram-positive isolates showed that 296 were catalase-negative, consistent with typical LAB characteristics, whereas 19 were catalase-positive and thus removed from subsequent screening. Consequently, 135 isolates were confirmed as Gram-positive, rod-shaped, catalase-negative bacteria and retained for probiotic property evaluation. For five isolates with ambiguous Gram-staining results, the test was repeated. Among these, isolates PMvet120, PMvet151, and PMvet183 exhibited budding cells and pleomorphic shapes, which were consistent with yeast morphology rather than bacteria (

Figure 1). These isolates also showed poor growth in MRS broth and were therefore excluded.

3.2. Probiotic Properties of Selected LAB Isolates

3.2.1. Acid Tolerance

Among the 135 LAB isolates confirmed as Gram-positive, rod-shaped, and catalase-negative, only five strains—PMvet120, PMvet151, PMvet183, PMvet212, and PMvet318—demonstrated acid tolerance, with a reduction in viable counts of approximately 1.00 log CFU/mL or less after incubation at pH 3.1 for 3 h. No isolates survived exposure to pH 2.0 under the same conditions. The survival rates of these five isolates at pH 3.1 are summarized in

Table 2.

3.2.2. Bile Salt Tolerance

The five acid-tolerant isolates were subsequently evaluated for their ability to survive in the presence of bile salts. After 24 h of anaerobic incubation at 37 °C, all isolates maintained viable counts above 6.00 log CFU/mL in MRS broth containing 0.3% bile salts. However, when the concentration was increased to 0.5%, only isolate PMvet212 retained a viable count of 6.56 ± 0.04 log CFU/mL, indicating substantial bile tolerance. In contrast, isolates PMvet151, PMvet183, and PMvet318 exhibited counts below the detection limit (<3.00 log CFU/mL) at 0.5% bile concentration, while PMvet120 showed partial survival. At 1.0% bile salts, none of the isolates survived above the detection threshold. The survival profiles are presented in

Table 3.

3.2.3. Cell Surface Hydrophobicity (MATH Assay)

The hydrophobicity of the five selected LAB isolates was assessed using the microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons (MATH) assay with xylene as the hydrophobic phase. The results revealed considerable variation among isolates. PMvet318 exhibited the highest hydrophobicity (12.38 ± 0.03%), suggesting a relatively better ability to adhere to the intestinal epithelium. This was followed by PMvet212 (7.85 ± 0.02%), while the remaining isolates demonstrated values below 7%, indicating weaker adhesion potential. The hydrophobicity profiles are summarized in

Table 4.

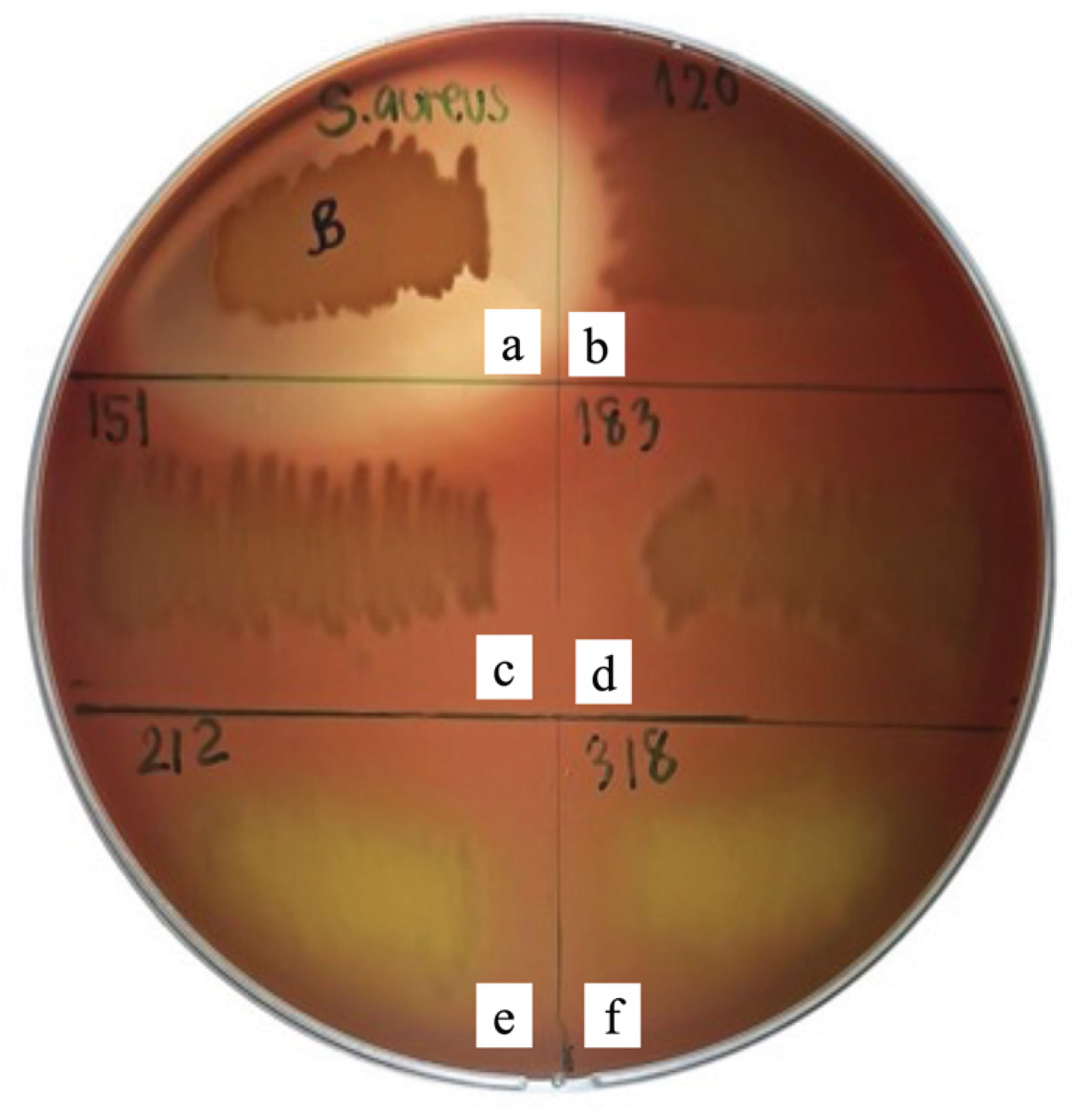

3.2.4. Hemolytic Activity (Safety Evaluation)

Hemolytic activity of the five LAB isolates was assessed on tryptic soy agar (TSA) supplemented with 5% sheep blood. The results indicated that isolates PMvet120, PMvet151, and PMvet183 exhibited γ-hemolysis, characterized by the absence of any clear or discolored zones around colonies, thereby suggesting a non-hemolytic and potentially safe profile for probiotic application. In contrast, isolates PMvet212 and PMvet318 displayed α-hemolysis, evidenced by greenish discoloration surrounding the colonies, which indicates partial red blood cell lysis (

Figure 2). The presence of α-hemolysis in these isolates raises potential safety concerns and suggests that they may not be suitable candidates for direct probiotic use without further safety evaluation.

3.2.5. Antimicrobial Activity Against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus

The antimicrobial activity of the cell-free supernatants (CFS) from the five selected LAB isolates was evaluated using the agar well diffusion assay against

E. coli (field isolate from diarrheic piglet) and

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538. Among the tested isolates, only PMvet212 and PMvet318 produced distinct and measurable inhibition zones against both target pathogens. In contrast, isolates PMvet120, PMvet151, and PMvet183 demonstrated incomplete or weak inhibition against E. coli and showed no detectable inhibition against S. aureus. The measured diameters of inhibition zones are summarized in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

The present study identified two lactic acid bacteria (LAB) isolates of the Bacilli group from fecal samples of suckling piglets (7–30 days old) that demonstrated probiotic potential. These findings are in line with earlier reports by Buasai Petsuriyawong (2011) [

22] and Dowarah et al. (2018) [

24], who successfully isolated LAB from piglet feces collected around weaning age (28–35 days). The detection of LAB at this early stage supports the well-established observation that piglet intestines are naturally colonized by Lactobacillus spp. before weaning, which are among the most prevalent beneficial microbes in the small intestine [

25]. Colonization is strongly influenced by maternal sources, particularly sow feces, the environment, and milk, consistent with evidence from both human and porcine milk showing the transfer of probiotic microorganisms to offspring [

26]. Recent investigations further confirm that maternal microbial transfer plays a vital role in shaping early-life gut microbiota composition and disease resilience in piglets [

6].

In addition to bacterial isolates, three yeast strains were also identified from the piglet feces in this study. Their ability to withstand acidic pH and bile salts is noteworthy, as yeasts are increasingly recognized as effective probiotics due to their ability to survive harsh gastrointestinal conditions. Previous works have identified

Saccharomyces boulardii and related yeast genera as promising candidates due to their acid tolerance, bile salt resistance, and ability to inhibit pathogens [

27,

28]. More recently, novel yeast strains from livestock sources have been shown to modulate immune responses and protect against enteric infections, reinforcing their potential in animal health management [

29,

30]. This suggests that while LAB remain the dominant focus of probiotic studies, cocci-shaped LAB such as Enterococcus and yeast isolates should not be overlooked in future investigations.

The acid and bile salt tolerance assays conducted here further confirmed strain-specific variability. Out of 135 confirmed LAB isolates, only five survived prolonged exposure at pH 3.1, although none survived at pH 2.0. This is consistent with earlier findings that probiotic survival in gastric conditions is highly strain-dependent [

31]. Among these five isolates, PMvet212 demonstrated superior tolerance to 0.5% bile salt, a concentration comparable to the physiological levels encountered in the small intestine. Such tolerance is crucial for probiotic viability after oral administration, as bile salts are known to disrupt microbial membranes [

32]. Recent studies have reinforced the role of bile-tolerant LAB in reducing diarrhea incidence and supporting intestinal health in weaning piglets [

33,

34]. Thus, the resilience of PMvet212 under bile stress highlights its potential as a candidate strain for feed supplementation in piglets facing post-weaning stress.

Other functional traits, including adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells and hemolytic activity, were also investigated. Surface hydrophobicity testing revealed that PMvet318 exhibited the highest percentage adhesion capacity (12.38%), although this was lower than the threshold suggested in some earlier reports (>40%). This finding underscores the complexity of adhesion mechanisms, as hydrophobicity alone does not fully explain epithelial colonization. Instead, multiple attributes such as auto-aggregation, extracellular polysaccharide production, and interactions with mucins contribute to successful colonization [

35]. Regarding safety, PMvet120, 151, and 183 were non-hemolytic (γ-hemolysis), while PMvet212 and 318 showed partial α-hemolysis. Although α-hemolysis is often considered less harmful than β-hemolysis, comprehensive genetic and phenotypic evaluations remain essential, as hemolysin genes have been reported in some Lactobacillus strains [

36]. Current safety guidelines strongly recommend further in vivo testing, including antibiotic resistance profiling and toxin gene screening, prior to commercial application [

37,

38].

Finally, antimicrobial activity was detected in isolates PMvet212 and 318, which inhibited both

Escherichia coli and

Staphylococcus aureus. These results are significant, as

E. coli is a primary cause of piglet diarrhea worldwide, and antibiotic-resistant strains remain a pressing concern in swine production. The inhibitory effect observed in this study is consistent with earlier work demonstrating that LAB produce antimicrobial compounds, including organic acids and bacteriocins, which reduce the growth of pathogenic bacteria [

21,

31]. More recently, studies have confirmed that piglet-derived LAB strains can effectively reduce pathogen colonization, improve intestinal barrier integrity, and enhance host immunity [

39,40]. The moderate inhibition zones observed here suggest that while PMvet212 and 318 are promising, further characterization of their antimicrobial metabolites and verification under in vivo conditions are necessary. These findings open future research directions focusing on multi-strain formulations or co-cultures combining LAB and yeast for synergistic effects in piglet health management.

5. Conclusions

In this study, only two bacilli-shaped LAB isolates obtained from piglet feces demonstrated promising probiotic potential, with tolerance to acidic and bile conditions, moderate antimicrobial activity, and partial adhesion ability. While these results indicate their potential role as feed additives in swine production, the overall efficacy of the isolates remains moderate when compared to the broader functional properties expected of commercially viable probiotics.

Therefore, further comprehensive evaluations are warranted. Future studies should expand the characterization of these isolates to include pathogen inhibition against a wider spectrum of enteric microbes, immunomodulatory activity, antibiotic resistance profiling, and in vivo performance trials. Additionally, integrating LAB with other probiotic candidates such as yeast may provide synergistic effects on gut health and growth performance in piglets. Such efforts would not only support the reduction of antibiotic use in livestock but also contribute to sustainable swine production by mitigating antimicrobial resistance and enhancing animal welfare.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—review and editing, Panuwat Yamsakul; Sample collection, Investigation, Data curation, Promporn Inyoo and Matsarina Kongton; Methodology, Laboratory, Montira Intanon and Nattakarn Awaiwanont. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Faculty of veterinary medicine, Chiang Mai university, Thailand.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank the faculty of veterinary medicine, Chiang Mai univer- sity, Thailand for supporting the budget.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fairbrother, J.M.; Nadeau, É.; Gyles, C.L. Escherichia coli in postweaning diarrhea in pigs: an update on bacterial types, pathogenesis, and prevention strategies. Animal Health Research Reviews 2005, 6, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppi, A. Swine enteric colibacillosis: diagnosis, therapy and antimicrobial resistance. Porcine Health Manag 2017, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.E.; Maxwell, C.V.; Brown, D.C.; de Rodas, B.Z.; Johnson, Z.B.; Kegley, E.B.; Hellwig, D.H.; Dvorak, R.A. Effect of dietary mannan oligosaccharides and(or) pharmacological additions of copper sulfate on growth performance and immunocompetence of weanling and growing/finishing pigs. Journal of Animal Science 2002, 80, 2887–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moredo, F.A.; Piñeyro, P.E.; Márquez, G.C.; Sanz, M.; Colello, R.; Etcheverría, A.; Padola, N.L.; Quiroga, M.A.; Perfumo, C.J.; Galli, L.; Leotta, G.A. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Subclinical Infection in Pigs: Bacteriological and Genotypic Characterization and Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 2015, 12, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, H.; Gong, M.; Yu, H.; Cottrill, M.; de Lange, C. Impact of feeding blends of organic acids and herbal extracts on growth performance, gut microbiota and digestive function in newly weaned pigs. Canadian Journal of Animal Science 2004, 84, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. Supplementation with probiotics as an alternative to antibiotics for prevention of bacterial diarrhea in piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; et al. Probiotics in swine production: A sustainable strategy for antimicrobial resistance mitigation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1523678. [Google Scholar]

- Boaventura, C.; Azevedo, R.; Uetanabaro, A.; Nicoli, J.; Braga, L. The Benefits of Probiotics in Human and Animal Nutrition. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Binns, N., 2013. ILSI Europe Concise Monograph Series Probiotics. Probiotics, Prebiotics and the Gut MicrobiotaBelgium.Fouhse, J., Zijlstra, R.T., Willing, B., 2016. The role of gut microbiota in the health and disease of pigs. Animal Frontiers 6, 30. [CrossRef]

- Kontula, P.; Jaskari, J.; Nollet, L.; De Smet, I.; von Wright, A.; Poutanen, K.; Mattila-Sandholm, T. The colonization of a simulator of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem by a probiotic strain fed on a fermented oat bran product: effects on the gastrointestinal microbiota. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 1998, 50, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Siragusa, S.; Berloco, M.; Caputo, L.; Settanni, L.; Alfonsi, G.; Amerio, M.; Grandi, A.; Ragni, A.; Gobbetti, M. Selection of potential probiotic lactobacilli from pig feces to be used as additives in pelleted feeding. Research in Microbiology 2006, 157, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojgani, N.; Hussaini, F.; Vaseji, N. Characterization of indigenous lactobacillus strains for probiotic properties. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2015, 8, e17523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; et al. Lactic acid bacteria-derived antimicrobial compounds and their application in pig production. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 87105. [Google Scholar]

- Senok, A.C.; Ismaeel, A.Y.; Botta, G.A. Probiotics: facts and myths. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2005, 11, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; et al. Indigenous Lactiplantibacillus reuteri improves intestinal health and reduces inflammation in piglets. Animals 2025, 13, 3812. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.-H.; Kim, J.-M.; Nam, H.-M.; Park, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-M. Screening lactic acid bacteria from swine origins for multistrain probiotics based on in vitro functional properties. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, D.; Li, C.; Qin, Y.; Yin, R.; Du, S.; Ye, F.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Tian, M.; Jin, N. In vitro evaluation of the probiotic and functional potential of Lactobacillus strains isolated from fermented food and human intestine. Anaerobe 2014, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmekci, H. B.A.a.S.O. Characterization of vaginal lactobacilli coaggregation ability with Escherichia coli. Microbiol Immunol 2009, 53, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adimpong, D.B.; Nielsen, D.S.; S√∏rensen, K.I.; Derkx, P.M.F.; Jespersen, L. Genotypic characterization and safety assessment of lactic acid bacteria from indigenous African fermented food products. BMC Microbiology 2012, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirichokchatchawan, W.; Pupa, P.; Praechansri, P.; Am-in, N.; Tanasupawat, S.; Sonthayanon, P.; Prapasarakul, N. Autochthonous lactic acid bacteria isolated from pig faeces in Thailand show probiotic properties and antibacterial activity against enteric pathogenic bacteria. Microbial Pathogenesis 2018, 119, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buasai Petsuriyawong, N.K. Screening of Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria from Piglet Feces. Kasetsart J. (Nat. Sci.) 2011, 45, 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, R. Blood Agar Plates and Hemolysis Protocols. 2005. Available online: https://asm.org/getattachment/7ec0de2b-bb16-4f6e-ba07-2aea25a43e76/protocol-2885.pdf.

- Dowarah, R.; Verma, A.K.; Agarwal, N.; Singh, P.; Singh, B.R. Selection and characterization of probiotic lactic acid bacteria and its impact on growth, nutrient digestibility, health and antioxidant status in weaned piglets. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0192978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, D.; Hill, J.E.; Van Kessel, A.G. Microbial succession in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of the preweaned pig. Livestock Science 2010, 133, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustakim, M.; Sinawat, S.; Salleh, S.N.; Purwati, E.; Alias, R.; Mohamad, S.A.; Mat Issa, Z. Human milk as a potential source for isolation of probiotic lactic acid bacteria: a mini review. Food Research 2019, 4, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerucka, D.; Piche, T.; Rampal, P. Review article: yeast as probiotics -Saccharomyces boulardii. Alimentary Pharmacology Therapeutics 2007, 26, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghandour, M.M.Y.; Tan, Z.L.; Abu Hafsa, S.H.; Adegbeye, M.J.; Greiner, R.; Ugbogu, E.A.; Cedillo Monroy, J.; Salem, A.Z.M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a probiotic feed additive to non and pseudo-ruminant feeding: a review. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2020, 128, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y. Yeast-derived probiotics enhance intestinal health and modulate gut microbiota in pigs. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 922134. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Sun, J. Novel yeast probiotics alleviate post-weaning diarrhea in piglets by regulating gut microbiota. Animals 2023, 13, 1783–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, S.; Lee, S.; Park, H.; Shin, H.; Holzapfel, W.; Huh, C.S. Development of putative probiotics as feed additives: validation in a porcine-specific gastrointestinal tract model. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2016, 100, 10043–10054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotcheva, V.; Hristozova, E.; Hristozova, T.; Guo, M.; Roshkova, Z.; Angelov, A. Assessment of potential probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria and yeast strains. Food Biotechnology 2002, 16, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, R.; Zhang, H.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W. Swine gut microbiota and its interaction with host nutrient metabolism. Animal Nutrition 2020, 6, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Deng, Y.; Yu, B. Probiotic supplementation reduces diarrhea and enhances gut health in weaning piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 112. [Google Scholar]

- García-Cayuela, T.; Korany, A.; Bustos, I.; Cadinanos, L.; Requena, T.; Peláez, C.; Martínez-Cuesta, M.C. Adhesion Abilities of Dairy Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains Showing an Aggregation Phenotype. Food Research International 2014, 57, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokesajjawatee, N.; Santiyanont, P.; Chantarasakha, K.; Kocharin, K.; Thammarongtham, C.; Lertampaiporn, S.; Vorapreeda, T.; Srisuk, T.; Wongsurawat, T.; Jenjaroenpun, P.; Nookaew, I.; Visessanguan, W. Safety Assessment of a Nham Starter Culture Lactobacillus plantarum BCC9546 via Whole-genome Analysis. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO 2006. Probiotics in food: health and nutritional properties and guidelines for evaluation. Rome: World Health Organization: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2006.

- Cui, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Li, Y. Safety assessment of probiotic Lactobacillus strains for swine nutrition. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 694203. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Fang, C.; Zhao, L. Probiotic Lactobacillus strains improve intestinal barrier function and immune responses in piglets. Animals 2022, 12, 1895–1906. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Deng, Y.; Yu, B. Probiotic supplementation reduces diarrhea and enhances gut health in weaning piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 112. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).