Submitted:

23 September 2024

Posted:

24 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

(3)

(3)2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Mn Oxides

2.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Manganese Oxides

2.1. Electrochemical Measurements

2.3.1. Ink Preparation

2.3.2. Ink Deposition on Glassy Carbon Rod

2.3.3. Three-Electrode Cell Set-up

3. Results

3.1. Nitrate-Glycine Synthesis

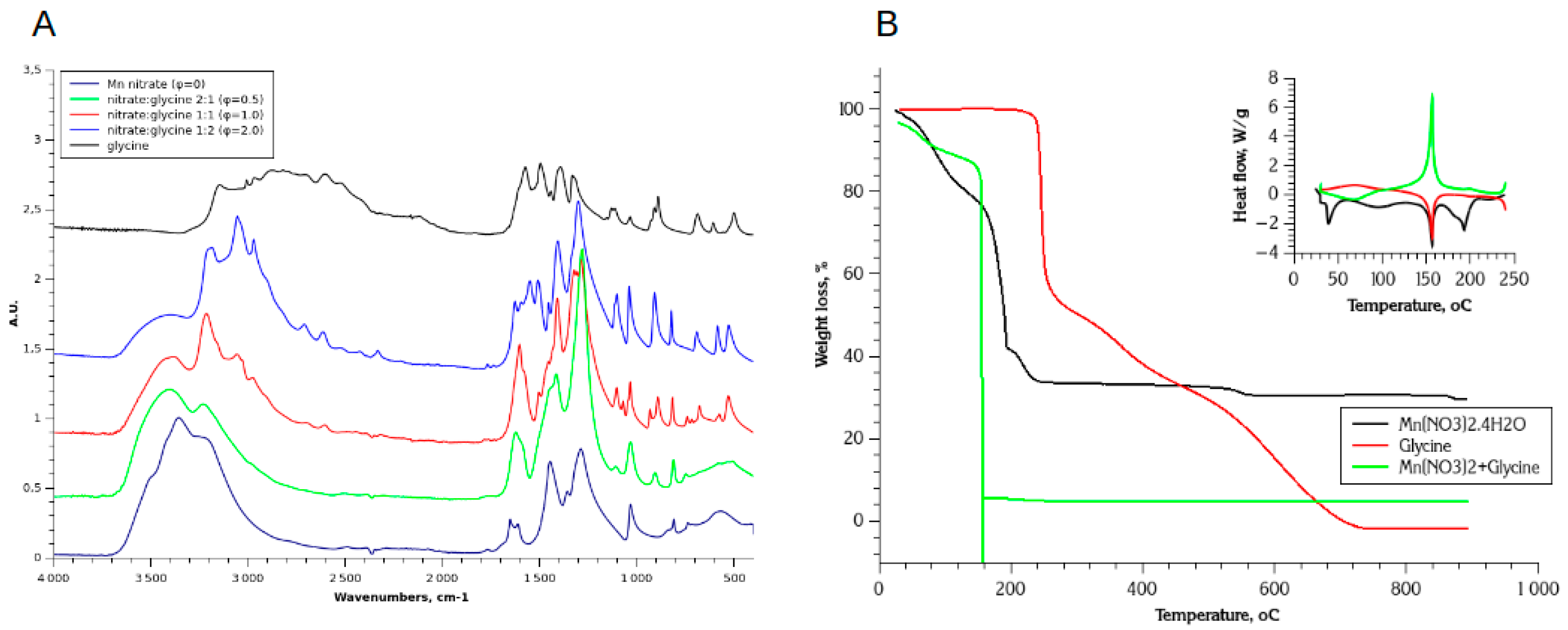

3.1.1. FTIR and TGA Analysis of Decomposition Processes

3.1.2. Mn(II) Nitrate (Figure 2A)

3.1.3. Glycine (Figure 2B)

3.1.3. Nitrate-Glycine Dried Solid Mixture (φ=1) (Figure 2C)

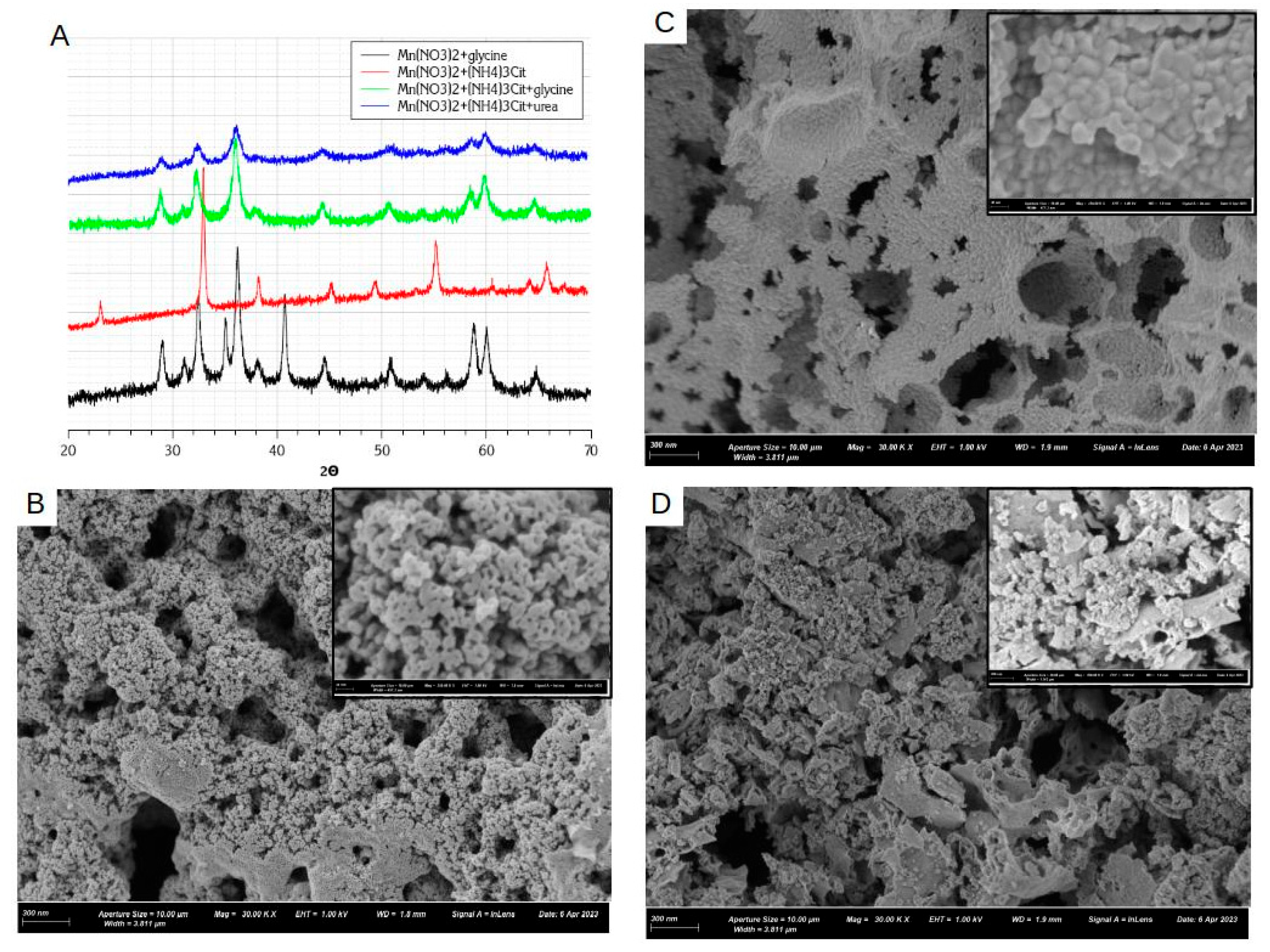

3.2. Analysis of the Products of SCS with Nitrate-Glycine Mixture

- MnO2 :ambient to toC < 461oC

- Mn2O3: 461°C < toC < 755°

- Mn3O4: 755°C < toC < 1292°

- MnO: above 1292oC

3.3. SCS Synthesis with Ammonium Citrate: Nitrate-Citrate, Nitrate-Citrate-Glycine, and Nitrate-Citrate-urea

3.3.1. Thermal Stability Studies with Nitrate-Citrate, Nitrate-Citrate-Glycine, and Nitrate-Citrate-Urea SCS Mixtures

3.3.2. Solution Combustion Synthesis with Ammonium Citrate

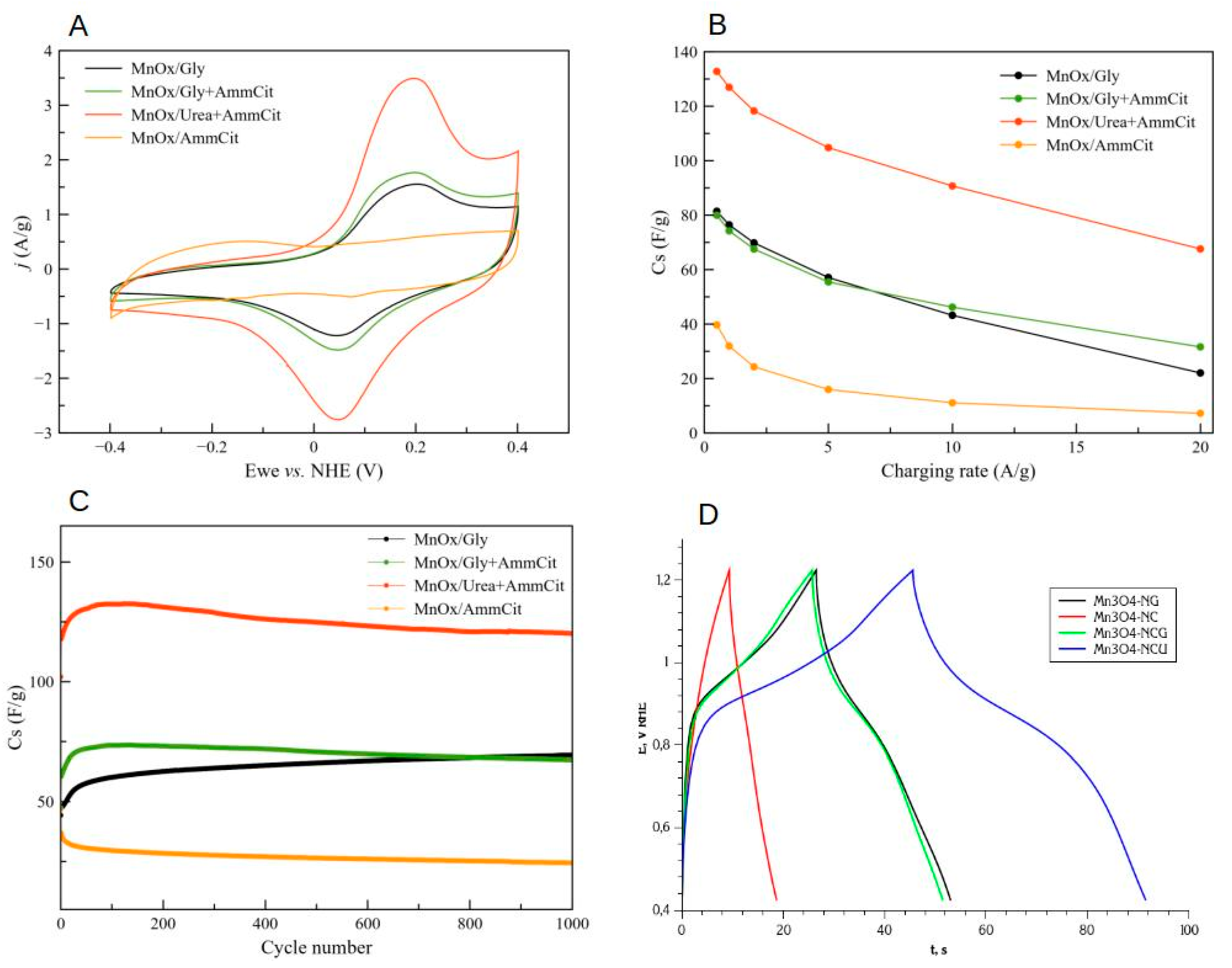

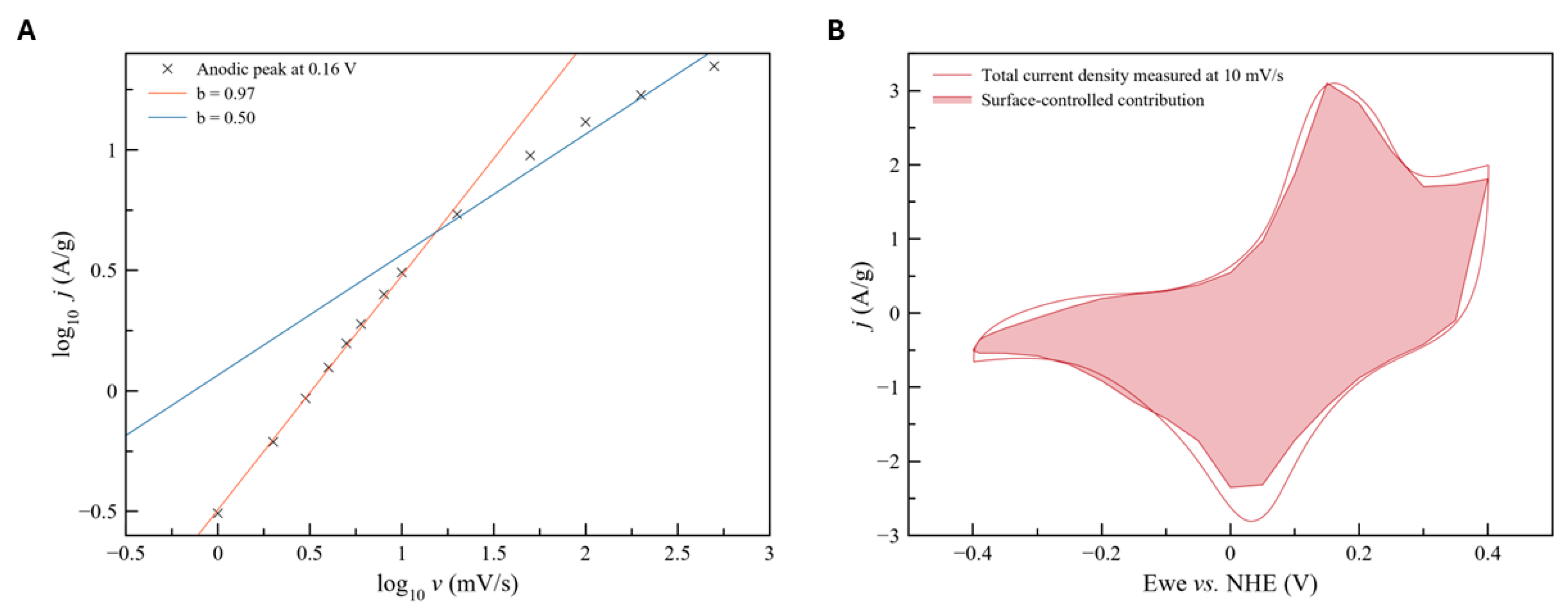

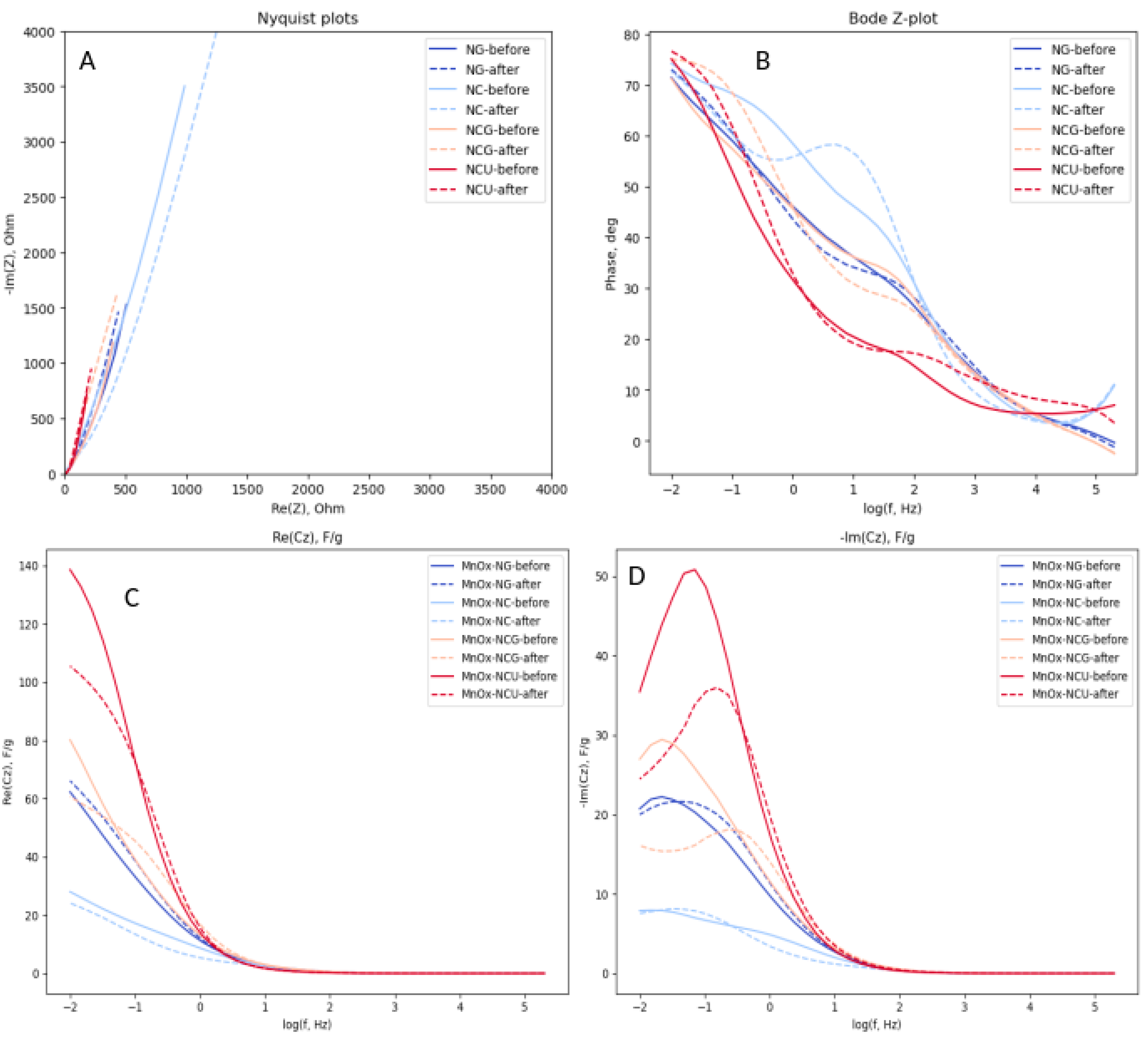

3.4. Electrochemical Properties of Mn Oxides Prepared by SCS

(5)

(5)4. Discussion

4.1. Nitrate-Glycine Synthesis

- During slow evaporation of solvent from nitrate and glycine mixed solution, the glycine complex of Mn(II) is formed, either [Mn(gly)(H2O)2](NO3)2, or [Mn(gly)(H2O)4](NO3)2. Formation of this complex ensures fine and uniform mixing of components of SCS mixture.

- The glycine complexes of Mn(II) are thermodynamically less stable than complexes of other transition metals [43,44] and easily decomposing upon heating [18]. The decomposition of this complex follows up its partial dehydration, and occurs at temperature 160-170 oC, which is below the decomposition of pure glycine (220 oC). It has been previously reported that decomposition of dried Mn nitrate-glycine mixture also occurs at lower temperature comparing to pure glycine under inert atmosphere [38].

- In comparison to a decomposition of pure nitrate and glycine, the first step of decomposition of dried mixture is fast, and results in formation of large amount of gas products. One may assume the “auto-catalytic” mechanism of glycine/nitrate decomposition with formation of glycine complex of Mn(II) as a catalytic intermediate. The fast kinetics of glycine-nitrate decomposition may be an indication of lowering of activation energy of this reaction, which is otherwise relatively high for both nitrate (210 kJ/mol) and glycine (155 kJ/mol) decompositions.

4.2. Analysis of the Products of SCS with Nitrate-Glycine Mixture

- The formation of mixture of oxides can be attributed to the partial reduction of Mn3O4 to MnO, indicating high temperature generated during the SCS decomposition reaction : at p(O2)=1 bar, MnO formation is detected only above 820 oC (Figure 1B). MnO remains a minor product due to effective evacuation of generated heat by formed gaseous products. However, if Mn2O3 or Mn3O4 oxide reduction to MnO is the main source of this oxide, one would expect its systematically higher content formed with higher φ value (due to higher reaction temperature), which was not experimentally observed.

- The alternative explanation of formation of MnO as an SCS product is the precipitation of Mn(OH)2 hydroxide due to the hydrolysis of Mn(II) nitrate during the solution evaporation. The pH of the solution of Mn(II) nitrate is slightly acidic (pH=4.6), both in the absence and in the presence of glycine, and thus no precipitation of Mn(OH)2 (pKb=12.7) is expected from nitrate solution. However, Mn(II) hydroxide may be precipitated during the evaporation of solvent due its much lower solubility comparing to nitrate (0.34 mg/100 mL and 118 g/100 mL respectively). The precipitated Mn(OH)2 hydroxide is then decomposed during the SCS reaction to MnO. The latter is not oxidized to higher oxides due to the oxygen lean atmosphere within the SCS reaction.

4.3. SCS Synthesis with Ammonium Citrate: Nitrate-Citrate, Nitrate-Citrate-Glycine, and Nitrate-Citrate-urea Mixtures

- In all 3 cases (Mn nitrate-citrate, nitrate-citrate-glycine, and nitrate-citrate-urea) only one crystalline oxide phase was detected, despite slower kinetics of decomposition and less uniform conditions of reaction propagation, comparing to nitrate-glycine synthesis. This observation support the assumption that the main source of inhomogeneity in the final products of SCS is formation of various forms of Mn precursors, such as metal complexes, dried salt, and hydroxide, during slow step of solvent evaporation. In the presence of citrate in the solution, Mn forms strong and stable complex with citrate ligands, which uniformly precipitates after solvent evaporation.

- In the case of ammonium citrate being the only fuel of SCS process, the only product of the reaction is Mn2O3 (Figure 6A), while in the presence of glycine and urea in the mixture, only Mn3O4 is formed. It can be argued that the presence of glycine or urea allows to reach higher temperature during the SCS reaction; alternatively, the decomposition of the intermediates of glycine or urea decomposition consumes oxygen resulting in lower local partial pressure p(O2). Both factors favorize formation of more reduced oxide, namely Mn3O4.

- Both XRD estimation of crystallite size, measurements of specific surface area, and SEM images points to smaller particles size in the case of nitrate-citrate-urea comparing to nitrate-citrate-glycine mixture. We attribute this effect to faster kinetics of second step of decomposition of nitrate-citrate-urea mixture, in which case formation of larger amount of smaller particles is favored, while particles are less sintered due to shorter reaction time. In both nitrate-citrate-glycine and nitrate-citrate-urea synthesis the particles are more sintered than in the case of nitrate-glycine synthesis, due to much faster reaction propagation and heat dissipation in the latter case.

4.4. Electrochemical Properties of Mn Oxides Prepared by SCS

- MnOx-NG sample consists of relatively large (ca. 20 nm) particles, which are not strongly sintered because of explosive character of SCS reaction. The explosive character of SCS process is related to the formation of a weak complex between Mn(II) nitrate and glycine, which is easily decomposed upon heating and provide significant exothermic effect for instantaneous self-propagation of the reaction. The final oxide product contains ca. 20%mol. of MnO and 80% of Mn3O4, and the presence of MnO is related to the hydrolysis of Mn nitrate during the slow evaporation of solvent before SCS reaction. The MnOx-NG electrode shows moderate charge capacitance (70 F/g at 2 A/g discharge) and very stable performance. MnO oxide is not stable in 1M NaOH and forms hydroxide, which does not contribute to the charge capacitance; however its presence allows to prevent dissolution of Mn3O4 oxide upon reduction in the form of Mn hydroxide, which is the main mechanism of this material degradation. The capacitance can be further significantly improved by forming a composite with carbon materials, as it is demonstrated in previous studies [8].

- MnOx-NC sample consists of Mn2O3 oxide particles of ca. 20 nm, slightly sintered. Citrate forms stronger complex with Mn(II), and its decomposition is not sufficiently exothermic to generate temperature sufficient for Mn3O4 formation, which requires ca. 950 oC at p(O2)=0.3 bar. MnOx-NC oxide demonstrate low charge capacitance in 1M NaOH (initially 22 F/g at 2 A/g), which is fast degrading upon galvanostatic cycling. The degradation cannot be explained only by possible dissolution of Mn oxide, but suggests changes in surface structure or composition, which my results in strong increase in contact interparticle resistance.

- Addition of an equimolar amount of a fuel, either glycine (MnOx-NCG) or urea (MnOx-NCU), to Mn(II) nitrate - ammonium citrate mixture allows to increase an exothermic effect of the reaction and obtain Mn3O4 oxide nanoparticles. Formation of MnO is suppressed by the presence of citrate. The SCS reaction in these cases are slower than in the case of MnOx-NG, and take few seconds. The reaction is slower in the case of nitrate-citrate-glycine mixture in comparison with nitrate-citrate-urea mixture, which is explained by possible interactions between the intermediates of citrate and glycine decomposition. The slower rate of reaction results in more sintered particles in comparison to MnOx-NG synthesis. Nevertheless, MnOx-NCU oxide demonstrate highest charge capacitance due to strong and fast pseudocapacitance phenomena (130 F/g at 2 A/g). The high capacitance of this oxide can be explained by its relatively high SSA, providing fast charging rate, and moderate sintering of particles, decreasing the interparticle contact resistance. Upon cycling the capacitance of both MnOx-NCG and MnOx-NCU after initial increase within first 100 cycles, slowly decays, resulting from the dissolution of Mn3O4 upon reduction in the form of Mn(II) hydroxide. Further study of the mechanism of dissolution of Mn3O4 particles upon their electrochemical performance is needed to develop the strategy to avoid its degradation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tarascon, J.M.; Armand, M. Issues and Challenges Facing Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. Nature 2001, 414, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poizot, P.; Laruelle, S.; Grugeon, S.; Dupont, L.; Tarascon, J.M. Nano-Sized Transition-Metal Oxides as Negative-Electrode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nature 2000, 407, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Goikolea, E.; Balducci, A.; Naoi, K.; Taberna, P.L.; Salanne, M.; Yushin, G.; Simon, P. Materials for Supercapacitors: When Li-Ion Battery Power Is Not Enough. Materials Today 2018, 21, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, M.M. Manganese Oxides for Lithium Batteries. Progress in Solid State Chemistry 1997, 25, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, M.M. Exploiting the Spinel Structure for Li-Ion Battery Applications: A Tribute to John B. Goodenough. Advanced Energy Materials 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.U.; Wang, F.; Toufiq, A.M.; Khattak, A.M.; Iqbal, A.; Ghazi, Z.A.; Ali, S.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. Electrochemical Properties of Single-Crystalline Mn3O4 Nanostructures and Their Capacitive Performance in Basic Electrolyte. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2016, 11, 8155–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.U.; Wang, F.; Toufiq, A.M.; Ali, S.; Khan, Z.U.H.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; He, K. Electrochemical Properties of Controlled Size Mn3O4 Nanoparticles for Supercapacitor Applications. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2018, 18, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerangueven, G.; Faye, J.; Royer, S.; Pronkin, S.N. Electrochemical Properties and Capacitance of Hausmannite Mn3O4 - Carbon Composite Synthesized by in Situ Autocombustion Method. Electrochimica Acta 2016, 222, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-G.; Jin, D.; Zhou, R.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Shen, C.; Xie, K.; Li, B.; Kang, F.; Wei, B. Highly Flexible Graphene/Mn3O4 Nanocomposite Membrane as Advanced Anodes for Li-Ion Batteries. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 6227–6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cui, L.-F.; Yang, Y.; Sanchez Casalongue, H.; Robinson, J.T.; Liang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Dai, H. Mn3O4−Graphene Hybrid as a High-Capacity Anode Material for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13978–13980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosaev, K.A.; Istomin, S.Ya.; Strebkov, D.A.; Tsirlina, G.A.; Antipov, E.V.; Savinova, E.R. AMn2O4 Spinels (A - Li, Mg, Mn, Cd) as ORR Catalysts: The Role of Mn Coordination and Oxidation State in the Catalytic Activity and Their Propensity to Degradation. Electrochimica Acta 2022, 428, 140923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.C.; Aruna, S.T.; Mimani, T. Combustion Synthesis: An Update. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science 2002, 6, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chick, L.A.; Pederson, L.R.; Maupin, G.D.; Bates, J.L.; Thomas, L.E.; Exarhos, G.J. Glycine-Nitrate Combustion Synthesis of Oxide Ceramic Powders. Materials Letters 1990, 10, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.J.; Suresh, K.; Patil, K.C. Combustion Synthesis of Fine-Particle Metal Aluminates. J Mater Sci 1990, 25, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, S.S.; Patil, K.C. Combustion Synthesis of Metal Chromite Powders. J American Ceramic Society 1992, 75, 1012–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul Dhas, N.; Patil, K.C. Combustion Synthesis and Properties of Fine Particle Spinel Manganites. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 1993, 102, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Mukasyan, A.S.; Rogachev, A.S.; Manukyan, K.V. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Nanoscale Materials. Chemical Reviews 2016, 116, 14493–14586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozek, R.; Rz, Z. Thermal Analysis of Manganese(II) Complexes With Glycine. 2001.

- De Bruijn, T.J.W.; De Ruiter, G.M.J.; De Jong, W.A.; Van Den Berg, P.J. Thermal Decomposition of Aqueous Manganese Nitrate Solutions and Anhydrous Manganese Nitrate. Part 2. Heats of Reaction. Thermochimica Acta 1981, 45, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohman, A.K.H.; Ismail, H.M.; Hussein, G.A.M. Thermal and Chemical Events in the Decomposition Course of Manganese Compounds. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 1995, 34, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yablokov, V.Ya.; Smel’tsova, I.L.; Zelyaev, I.A.; Mitrofanova, S.V. Studies of the Rates of Thermal Decomposition of Glycine, Alanine, and Serine. Russ J Gen Chem 2009, 79, 1704–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, I.M.; Muth, C.; Drumm, R.; Kirchner, H.O.K. Thermal Decomposition of the Amino Acids Glycine, Cysteine, Aspartic Acid, Asparagine, Glutamic Acid, Glutamine, Arginine and Histidine. BMC Biophys 2018, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaliullin, Sh.M.; Zhuravlev, V.D.; Bamburov, V.G. Solution-Combustion Synthesis of Oxide Nanoparticles from Nitrate Solutions Containing Glycine and Urea: Thermodynamic Aspects. Int. J Self-Propag. High-Temp. Synth. 2016, 25, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y. Solution-Combustion Synthesis of ε-MnO2 for Supercapacitors. Materials Letters 2010, 64, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puértolas, B.; Smith, A.; Vázquez, I.; Dejoz, A.; Moragues, A.; Garcia, T.; Solsona, B. The Different Catalytic Behaviour in the Propane Total Oxidation of Cobalt and Manganese Oxides Prepared by a Wet Combustion Procedure. Chemical Engineering Journal 2013, 229, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piumetti, M.; Fino, D.; Russo, N. Mesoporous Manganese Oxides Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis as Catalysts for the Total Oxidation of VOCs. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2015, 163, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kéranguéven, G.; Faye, J.; Royer, S.; Pronkin, S.N. Electrochemical Properties and Capacitance of Hausmannite Mn3O4 – Carbon Composite Synthesized by in Situ Autocombustion Method. Electrochimica Acta 2016, 222, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kéranguéven, G.; Bouillet, C.; Papaefthymiou, V.; Simonov, P.A.; Savinova, E.R. How Key Characteristics of Carbon Materials Influence the ORR Activity of LaMnO3- and Mn3O4-Carbon Composites Prepared by in Situ Autocombustion Method. Electrochimica Acta 2020, 353, 136557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Sun, M.; Hu, H. One-Step Combustion Synthesis of C-Mn3O4/MnO Composites with High Electrochemical Performance for Supercapacitor. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 6, 035511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, M.; Einaga, H.; Shangguan, W. Catalytic Activity of Porous Manganese Oxides for Benzene Oxidation Improved via Citric Acid Solution Combustion Synthesis. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2020, 98, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaei, Z.; Kermani, F.; Moosavi, F.; Kargozar, S.; Khakhi, J.V.; Mollazadeh, S. In Silico Study and Experimental Evaluation of the Solution Combustion Synthesized Manganese Oxide (MnO2) Nanoparticles. Ceramics International 2022, 48, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vratny, F. Infrared Spectra of Metal Nitrates. Appl Spectrosc 1959, 13, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laulicht, I.; Pinchas, S.; Samuel, D.; Wasserman, I. The Infrared Absorption Spectrum of Oxygen-18-Labeled Glycine. J. Phys. Chem. 1966, 70, 2719–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Rai, A.K.; Singh, V.B.; Rai, S.B. Vibrational Spectrum of Glycine Molecule. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2005, 61, 2741–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov, D.; Herak, R.; Prelesnik, B.; Ribar, B. The Crystal Structure of Manganese Nitrate Tetrahydrate Mn(NO3)2 · 4H2O. Zeitschrift für Kristallographie - Crystalline Materials 1973, 137, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K. Applications in Coordination Chemistry. In Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008; pp. 1–273 ISBN 978-0-470-40588-8.

- Devereux, M.; Jackman, M.; McCann, M.; Casey, M. Preparation and Catalase-Type Activity of Manganese(II) Amino Acid Complexes. Polyhedron 1998, 17, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komova, O.V.; Mukha, S.A.; Ozerova, A.M.; Odegova, G.V.; Simagina, V.I.; Bulavchenko, O.A.; Ishchenko, A.V.; Netskina, O.V. The Formation of Perovskite during the Combustion of an Energy-Rich Glycine–Nitrate Precursor. Materials 2020, 13, 5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedüs, A.J.; Horkay, K.; Székely, M.; Stefániay, W. Thermogravimetrische Untersuchung der Mangan(II)-oxid-Pyrolyse. Mikrochim Acta 1966, 54, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.; Hallgren, L.J. Infrared Absorption Spectra of Alkali Metal Nitrates and Nitrites above and below the Melting Point. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1960, 33, 900–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, P.K.; Schrey, F.; Prescott, B. The Thermal Decomposition of Aqueous Manganese (II) Nitrate Solution. Thermochimica Acta 1971, 2, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Lv, S.; Zhou, C. Thermal Decomposition Kinetics of Glycine in Nitrogen Atmosphere. Thermochimica Acta 2013, 552, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, A.; De Robertis, A.; De Stefano, C.; Gianguzza, A.; Patanè, G.; Rigano, C.; Sammartano, S. Thermodynamic Parameters for the Formation of Glycine Complexes with Magnesium(II), Calcium(II), Lead(II), Manganese(II), Cobalt(II), Nickel(II), Zinc(II) and Cadmium(II) at Different Temperatures and Ionic Strengths, with Particular Reference to Natural Fluid Conditions. Thermochimica Acta 1995, 255, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H.; Nozaki, T.; Fukuda, Y.; Kabata, T. A Polarographic Study of the Glycine Complexes of Copper(II), Lead(II), Cadmium(II), and Manganese(II). BCSJ 1991, 64, 697–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Wu, J.-M. Nanomaterials via Solution Combustion Synthesis: A Step Nearer to Controllability. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 58090–58100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, S.; Navrotsky, A. Thermodynamic Properties of Manganese Oxides. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 1996, 79, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzapetakis, M.; Karligiano, N.; Bino, A.; Dakanali, M.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Tangoulis, V.; Terzis, A.; Giapintzakis, J.; Salifoglou, A. Manganese Citrate Chemistry: Syntheses, Spectroscopic Studies, and Structural Characterizations of Novel Mononuclear, Water-Soluble Manganese Citrate Complexes. Inorganic Chemistry 2000, 39, 4044–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.F.; Zhou, Z.H. Manganese Citrate Complexes: Syntheses, Crystal Structures and Thermal Properties. Journal of Coordination Chemistry 2009, 62, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strouse, J.; Layten, S.W.; Strouse, C.E. Structural Studies of Transition Metal Complexes of Triionized and Tetraionized Citrate. Models for the Coordination of the Citrate Ion to Transition Metal Ions in Solution and at the Active Site of Aconitase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, F.; Ma, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, Q.; Liao, D.; Li, L. Homo- and Hetero-Metallic Manganese Citrate Complexes: Syntheses, Crystal Structures and Magnetic Properties. Polyhedron 2005, 24, 1656–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feick, G.; Hainer, R.M. On the Thermal Decomposition of Ammonium Nitrate. Temperatures and Reaction Rate. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1954, 698, 5860–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Dave, P.N. Review on Thermal Decomposition of Ammonium Nitrate. Journal of Energetic Materials 2013, 31, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babrauskas, V.; Leggett, D. Thermal Decomposition of Ammonium Nitrate. Fire and Materials 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybowski, A.K.; Tate, S.S.; Datta, S.P. Magnesium and Manganese Complexes of Citric and Isocitric Acids. J. Chem. Soc. A 1970, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, A.M.; Kaduk, J.A. Crystal Structures of Ammonium Citrates. Powder Diffr. 2019, 34, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbooti, M.M.; Dhoaib, A.-S.A. Thermal Decomposition of Citric Acid. Thermochimica Acta 1986, 98, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrzykowski, D.; Hebanowska, E.; Nowak-Wiczk, G.; Makowski, M.; Chmurzyński, L. Thermal Behaviour of Citric Acid and Isomeric Aconitic Acids. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2011, 104, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valletta, R.M.; Pliskin, W.A. Preparation and Characterization of Manganese Oxide Thin Films. THIN FILMS 1967, 114, 944–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleckiene, R.; Sviklas, A.; Slinksiene, R. Reaction of Urea with Citric Acid. Russ J Appl Chem 2005, 78, 1651–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaber, P.M.; Colson, J.; Higgins, S.; Thielen, D.; Anspach, B.; Brauer, J. Thermal Decomposition (Pyrolysis) of Urea in an Open Reaction Vessel. Thermochimica Acta 2004, 424, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, S.; Mitchell, J.B.; Wang, R.; Zhan, C.; Jiang, D.; Presser, V.; Augustyn, V. Pseudocapacitance: From Fundamental Understanding to High Power Energy Storage Materials. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 6738–6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabova, A.S.; Napolskiy, F.S.; Poux, T.; Istomin, S.Ya.; Bonnefont, A.; Antipin, D.M.; Baranchikov, A.Ye.; Levin, E.E.; Abakumov, A.M.; Kéranguéven, G.; et al. Rationalizing the Influence of the Mn(IV)/Mn(III) Red-Ox Transition on the Electrocatalytic Activity of Manganese Oxides in the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Electrochimica Acta 2016, 187, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcês Gonçalves, P.R.; De Abreu, H.A.; Duarte, H.A. Stability, Structural, and Electronic Properties of Hausmannite (Mn3O4) Surfaces and Their Interaction with Water. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2018, 122, 20841–20849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, Q.; Li, J. Review And Prospect of Mn 3 O 4 -Based Composite Materials For Supercapacitor Electrodes. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 10407–10423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Oh, S.M. Complex Capacitance Analysis of Porous Carbon Electrodes for Electric Double-Layer Capacitors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, A571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Reactions | Conditions | Heat effect (kJ/mol) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn(II) nitrate, Mn(NO3)2 | Mn(NO3)2 → [MnONO3] + NO2 → MnO2 + 2NO2 | ca.240 oC | 155±12 | [19,20] |

| MnO2 → Mn2O3 | 560-570 oC | ≈24 | ||

| Mn2O3 → Mn3O4 | above 800 oC | / | ||

| Glycine, C2H5NO2 | 4C2H5NO2 + 9O2 → 5H2O + 4CO2 + N2 | 210 oC | -972.98±0.12 | [21] |

| 4C2H5NO2 → 6H2O + 2NH3 + 6C + 2HNCO | 250 oC, no O2 | -528 | [22] |

| Precursor | Fuel | Product | Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn(NO3)2 | Glycine | ε-MnO2, 23 m2/g | Heating plate evaporation/ignition; φ=0.5 | [24] |

| ε-MnO2, 43 m2/g | φ=2.0; higher φ results in better crystallinity | |||

| Mn(NO3)2 | Glyoxalic acid | Mn3O4+Mn2O3, 43 m2/g | Oven heating up to 120oC (1h ramp, 1h hold), then annealing at 350oC for 4h | [25] |

| Ketoglutaric acid | Mn2O3+Mn3O4, 23 m2/g | |||

| Mn(NO3)2 | Glycine | Mn2O3; 43 m2/g, 21±4 nm | Oven heating at 600oC for 20 min; φ=0.5 | [26] |

| Mn3O4; 46 m2/g, 17±3 nm | 500oC, 30 min; φ=2 | |||

| Mn2O3+MnO2; 47 m2/g | 350oC, 120 min, φ=2 | |||

| Mn(NO3)2 | Glycine | Mn3O4; 32 m2/g | Slow evaporation in air, then heating plate ignition at 350oC | [27,28] |

| Mn3O4/C; 5-35 nm | + x% of Vulcan | |||

| MnAc2 | Ethanol | Mn3O4(85%) + MnO(15%) | Flame ignition of ethanol | [29] |

| Mn(NO3)2 | Citric acid | MnO2, 6.3 m2/g | Oven evaporation at 150oC for 5h, then annealing at 400oC for 3h in air; φ=0 | [30] |

| Mn3O4 + Mn2O3, 15.3 m2/g | φ=0.5 | |||

| Mn3O4, 31.7 m2/g | φ=1 | |||

| Mn2O3, 55.1 m2/g | φ=2 | |||

| Mn3O4 + Mn2O3, 38.2 m2/g | φ=4 | |||

| Mn(NO3)2 | Urea | 68%MnO2 + 32%Mn2O3, 7.5 m2/g | 330°C evaporation/ignition in ovenφ=0.2 | [31] |

| 32%MnO2 + 68%Mn2O3 | φ=0.3 | |||

| 22%MnO2 + 78%Mn2O3 | φ=0.4 | |||

| Mn2O3, 68±12 nm | φ=1 | |||

| 65%Mn3O4 + 35%MnO | φ=2 | |||

| Glycine | Mn2O3 | φ=0.2 | ||

| Mn2O3 | φ=0.3 | |||

| Mn2O3 | φ=0.5 | |||

| Mn3O4 | φ=1 | |||

| Mn3O4 | φ=2 |

| Name | Fuel | XRD attribution | Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| MnOx-NG-0.5 | Glycine, φ=0.50 | Mn2O3 + [Mn3O4]1 | 23-26 nm(2), 17 m2/g |

| MnOx-NG-0.75 | Glycine, φ=0.75 | Mn2O3 + Mn3O4 | 18-27 nm, 4 m2/g |

| MnOx-NG-1.0 | Glycine, φ=1.00 | Mn3O4 + [MnO] | 19-22 nm, 40 m2/g |

| MnOx-NG-1.25 | Glycine, φ=1.25 | Mn3O4 + [MnO] | 19-20 nm, 18 m2/g |

| MnOx-NG-1.5 | Glycine, φ=1.50 | Mn3O4 + [MnO] | 20-22 nm, 14 m2/g |

| MnOx-NC-1.0 | (NH4)3Cit | Mn2O3 | 20-22 nm, 14 m2/g |

| MnOx-NCG-1.0 | NH4)3Cit + Glycine | Mn3O4 | 11.3 nm, 24 m2/g |

| MnOx-NCU-1.0 | NH4)3Cit + Urea | Mn3O4 | 9.3nm, 35 m2/g |

| Precursor | IR band (position cm-1, observation)3 | Attribution |

|---|---|---|

| Mn(NO3)2.4H2O | 3430, st.br. 3185, s. 2736, m. 2147, m. 1762, st., s. 1601, st., s. 1435, sh. 1367, st. 1055, st. 826, st. |

ν(OH) ν1+ν4 2ν2 ν3 (NO3-) ν3 (NO3-) ν1 (NO3-) ν2 (NO3-) |

| Glycine, NH2CH2COOH | 3165, w, sh. 2820, w 2610, 2120, m 1604 1510 1412 1330 1110 1030 890 690 610 |

νa(NH3+) νs(CH) νs(NH3+) νa(COO-) + τ(NH3+) νa(COO-) δs(NH3+) νs(COO-) δ(CH2) + δ(NH2) ρ(NH3+) tw.(NH2) δ(NH2) + δ(CH2) ρ(COO-) ω(COO-) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).