Submitted:

21 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Ethics Statement

2.2. Animals and Diets

2.3. Data Recording and Samples Collections

2.4. Microbiota Analysis

2.5. Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Animal Performances

3.2. Microbiome

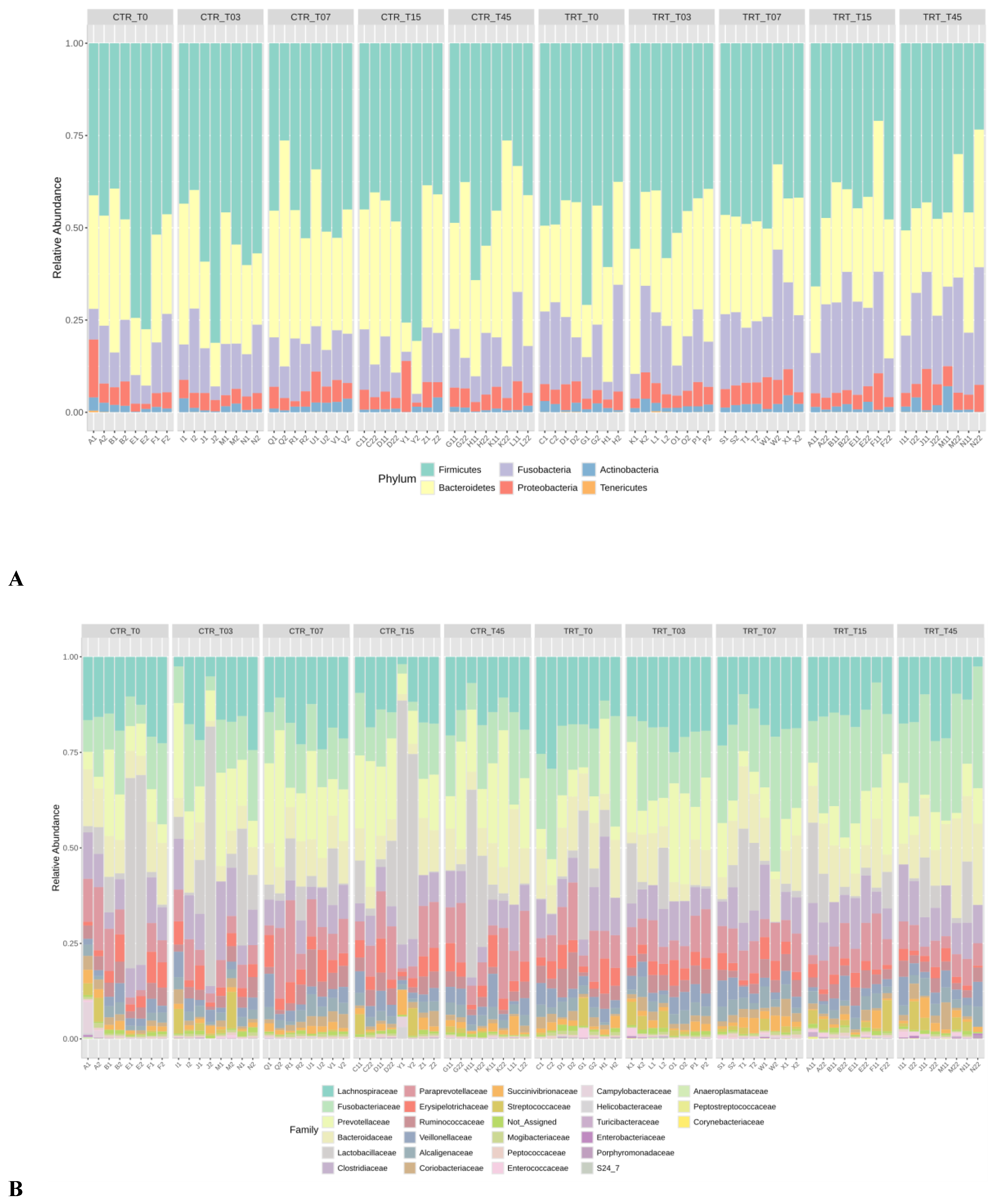

3.2.1. Relative Abundances

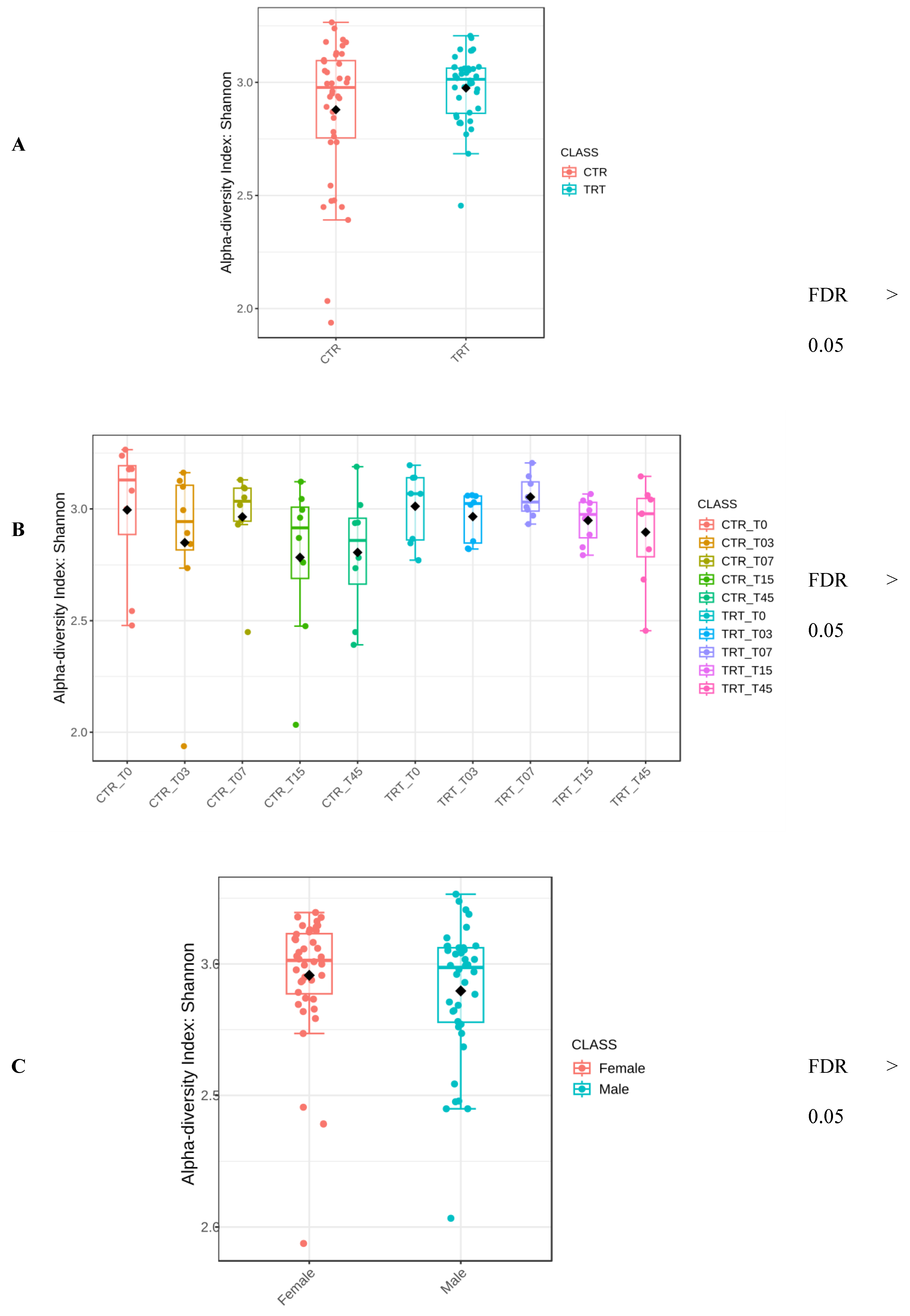

3.2.2. Alpha Diversity

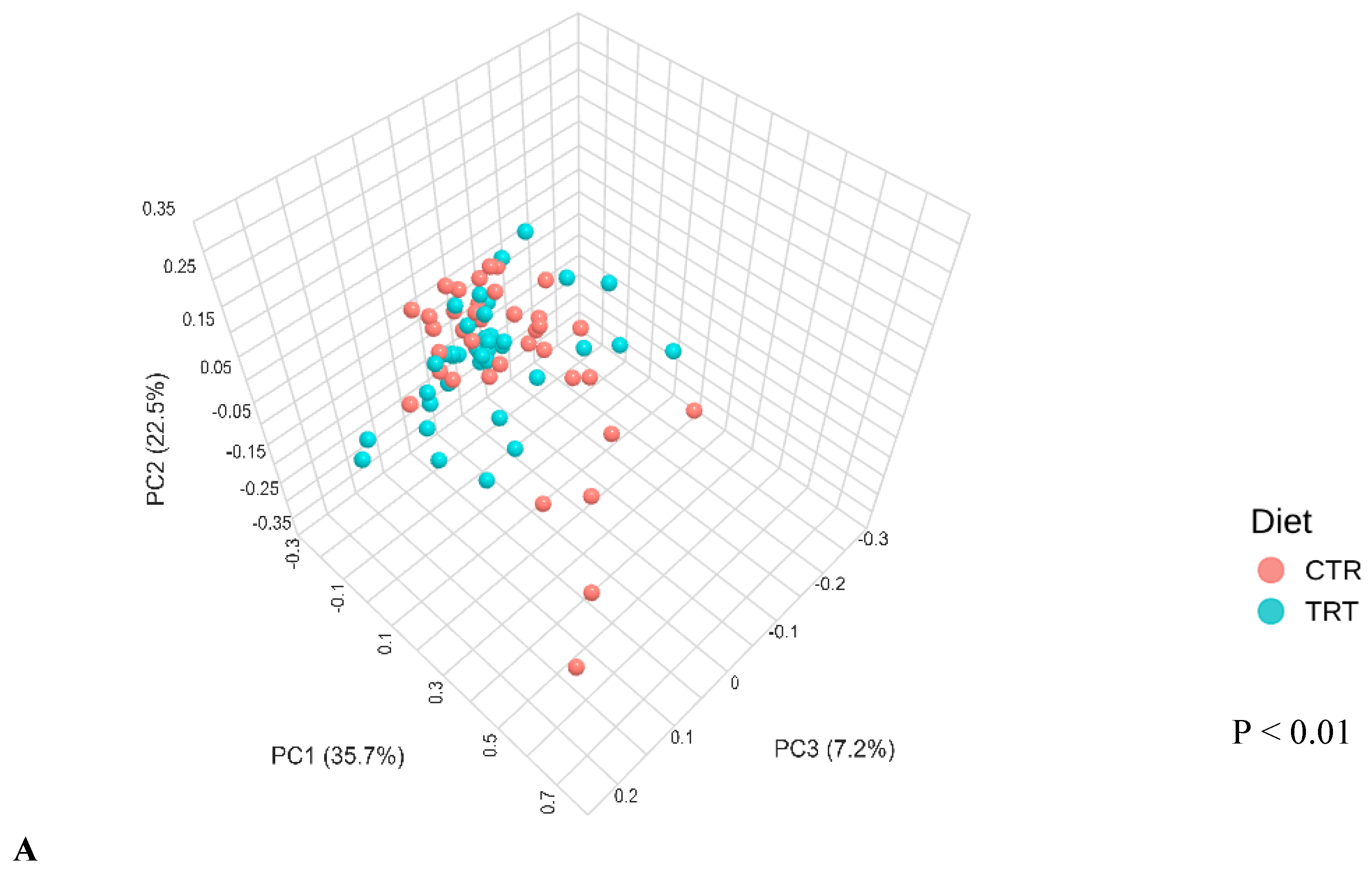

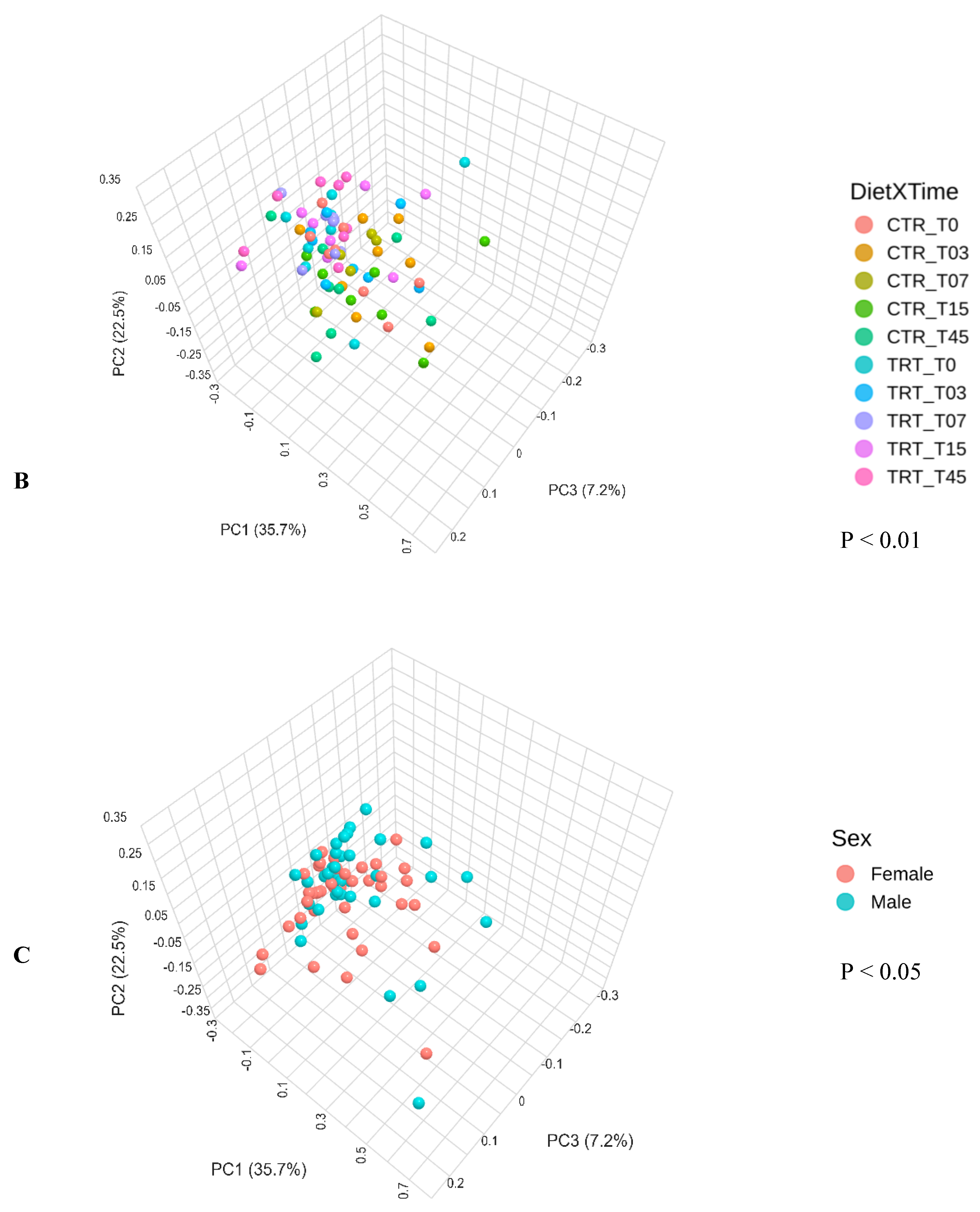

3.2.3. Beta Diversity

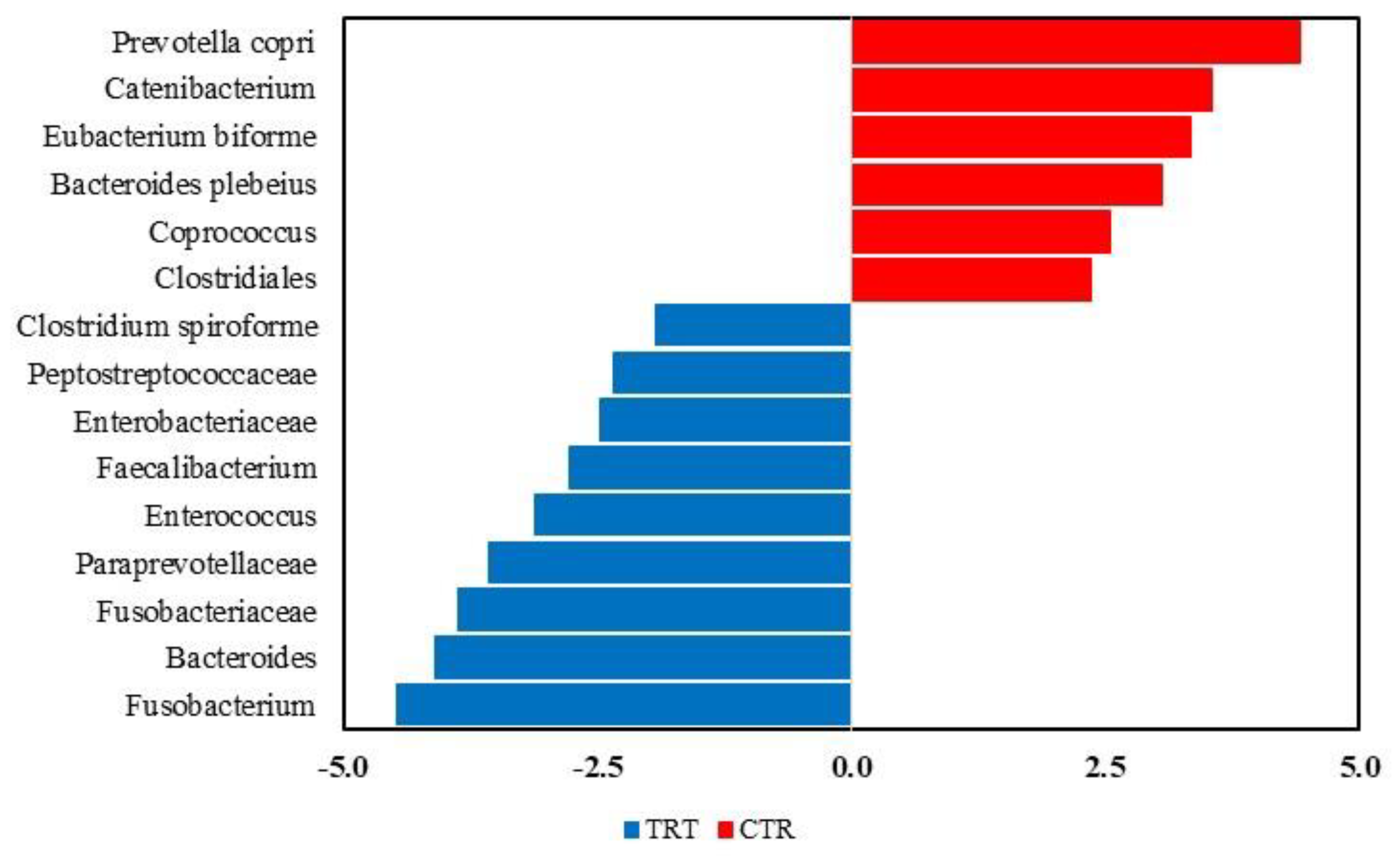

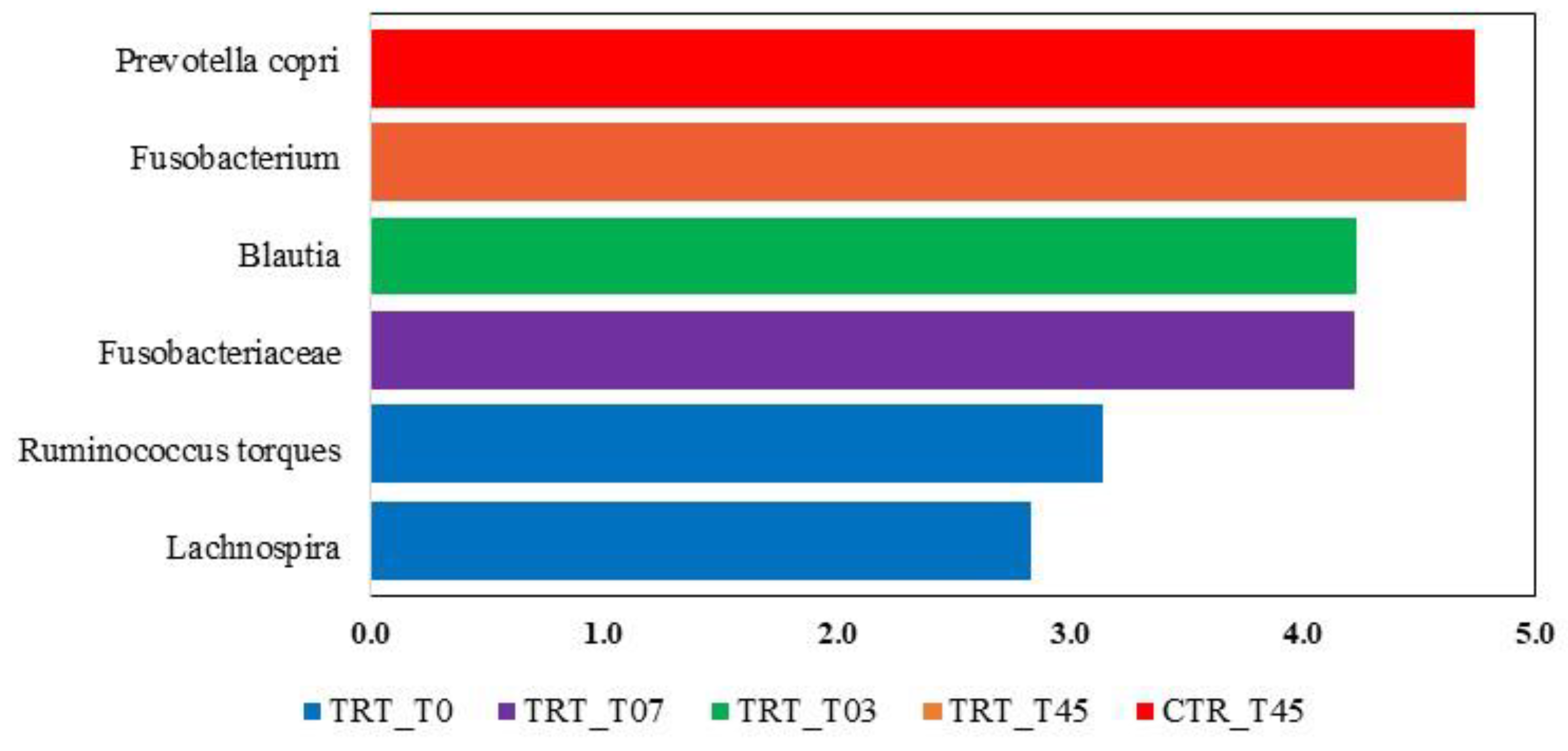

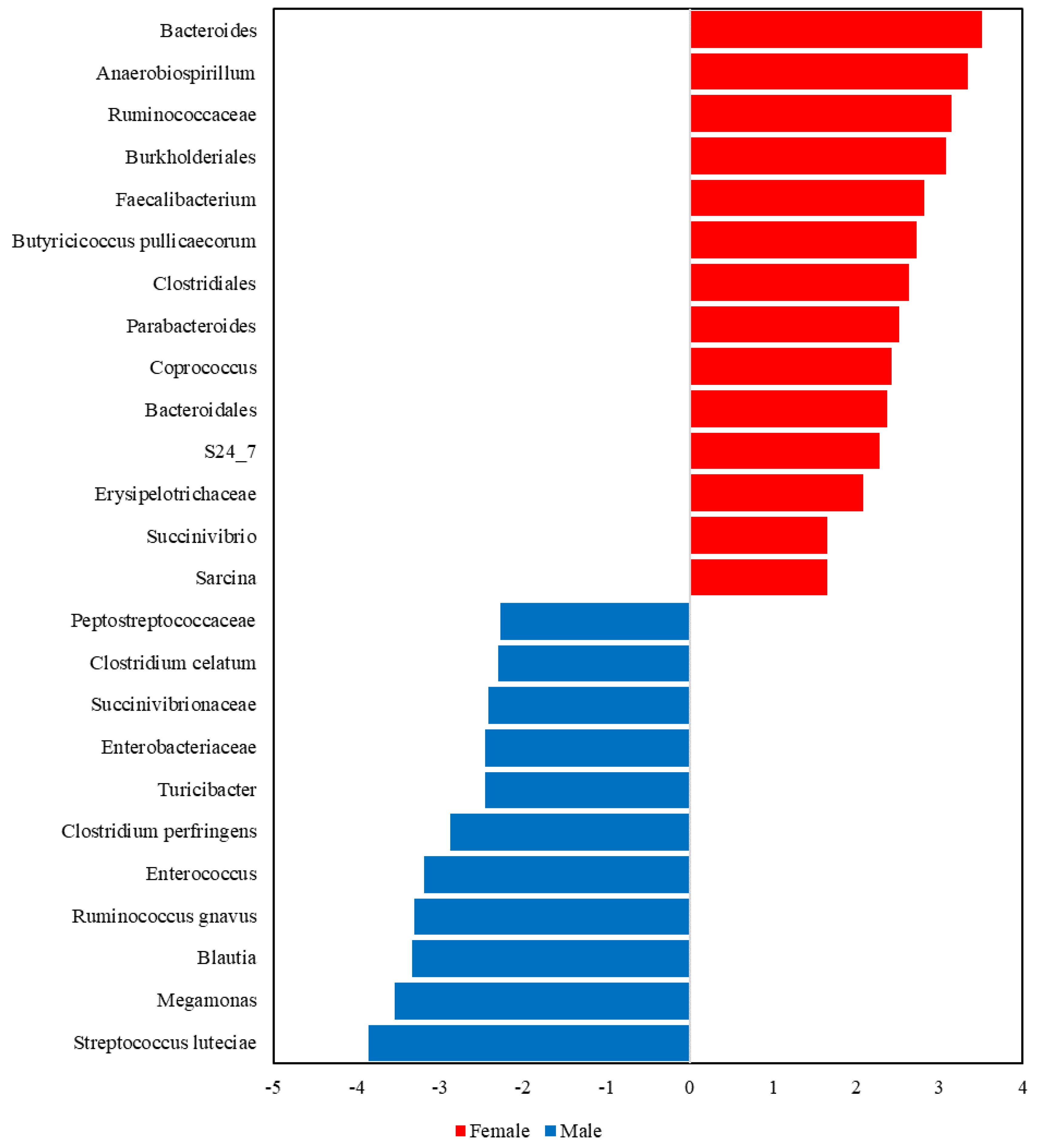

3.2.4. LEfSe Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Animal Performances

4.2. Fecal Microbiome

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; van Hul, M. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Zheng, D.P.; Elinav, E. Diet-microbiota interactions and personalized nutrition. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, C. D.; Young, W.; Maclean, P. H.; Cookson, A. L.; Bermingham, E. N. Metagenomic insights into the roles of Proteobacteria in the gastrointestinal microbiomes of healthy dogs and cats. Microbiologyopen 2018, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A. M.; Walter, J.; Segal, E.; Spector, T. D. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018, 361, k2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phimister, F.D.; Anderson, R.C.; Thomas, D.G.; Farquhar, M.J.; Maclean, P.; Jauregui, R.; Young, W.; Butowski, C.F.; Bermingham, E.N. Using meta-analysis to understand the impacts of dietary protein and fat content on the composition of fecal microbiota of domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris): A pilot study. Microbiologyopen 2024, 13, e1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honneffer, J. B., Steiner, J. M., Lidbury, J. A., & Suchodolski, J. S. Variation of the microbiota and metabolome along the canine gastrointestinal tract. Metabolomics 2017, 13, 26. [CrossRef]

- Pilla, R.; Suchodolski, J. S. The role of the canine gut microbiome and metabolome in health and gastrointestinal disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchodolski, J. S.; Camacho, J.; Steiner, M. Analysis of bacterial diversity in the canine duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon by comparative16S rRNAgene analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 66, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; de Hase, E.M.; van Hul, M. Gut microbiota and host metabolism: from proof of concept to therapeutic intervention. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolte, L.A.; Vila, A.V.; Imhann, F. , Long-term dietary patterns are associated with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory features of the gut microbiome. Gut 2021, 70, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasevich, M. R.; Kerr, K. R.; Dilger, R. N.; Fahey, G. C.; Guérin-Deremaux, L.; Lynch, G. L.; Wils, D.; Suchodolski, J. S.; Steer, J. M.; Dowd, S. E.; Swanson, K. S. Modulation of the faecal microbiome of healthy adult dogs by inclusion of potato fibre in the diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menke, S.; Wasimuddin, Meier, M.; Melzheimer, J.; Mfune, J. K. E.; Heinrich, S.; Thalwitzer, S.; Wachter, B.; Sommer, S. Oligotyping reveals differences between gut microbiomes of freeranging sympatric Namibian carnivores (Acinonyx jubatus, Canis mesomelas) on a bacterial species-like level. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 526. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, T. M.; Rogers, T. L.; Brown, M. V. The gut bacterial community of mammals from marine and terrestrial habitats. PLoS One 2013, 8, e83655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Wu, Q.; Deng, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Lu, G.; Wei, F. Adaptive evolution to a high purine and fat diet of carnivorans revealed by gut microbiomes and host genomes. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 1711–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarsella, E.; Stefanon, B.; Cintio, M.; Licastro, D.; Sgorlon, S.; Monego, S.D.; Sandri, M. Learning machine approach reveals microbial signatures of diet and sex in dog. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15, e0237874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouei, F.; Armone, R.; Stefanon, B.; Randazzo, A.; Chiofalo, B. Long-term dietary intervention of the hydrolyzed feather meal on microbiota composition of adult female dogs. Res. Vet. Sci. 2024, 176, 10534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, E.T.; Summers, J.D.; Slinger, S.J. Keratin as a source of protein for the growing chick. 1. Amino acid imbalance as the cause for inferior performance of feather meal and the implication of disulfide bonding in raw feathers as the reason for poor digestibility. Poult. Sci. 1966, 45, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, M.W.; Fritts, C.A.; Waldroup, P.W. Utilization of avizyme 1502 in corn-soyabean meal diets with and without antibiotics. Poult. Sci. 2002, 81, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Odetallah, N.H.; Wang, J.J.; Garlich, J.D.; Shih, J.C.H. Keratinase in starter diets improves growth of broiler chicks. Poult. Sci. 2003, 82, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Yadav, R. Keratinolysis of human hair and chicken feather by nondermatophytic keratinophilic fungi isolated from soil. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2020, 12, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Kumar, J. Chicken feather waste degradation by Alternaria tenuissima and its application on plant growth. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2020, 12, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Kumar, P.; Kushwaha, R.K.S. Recycling of chicken feather protein into compost by Chrysosporium indicum JK14 and their effect on the growth promotion of Zea mays. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2020, 21, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Volik, V.; Ismailova, D.; Lukashenko, V.; Saleeva, I.; Morozov, V. Biologically active feed additive development based on keratin and collagen- containing raw materials from poultry waste. Int. Transact. J. Eng. Manage. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEDIAF. Nutritional Guidelines for Complete and Complementary Pet Food for Cats and Dogs. The European Pet Food Industry Federation. FEDIAF Press (2021).

- Laflamme, D.P. Development and validation of a body condition score system for dogs. Canine Pract. 1997, 22, 10–5. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, K.; Bartges, J.; Buffington, T.; Freeman, L.M., Grabow, M.; Legred, J.; Ostwald, D. Jr. AAHA nutritional assessment guidelines for dogs and cats. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2010, 46, 285–96. [CrossRef]

- Moxham, G. The WALTHAM faeces scoring system—a tool for veterinarians and pet owners: how does your pet rate? WALTHAM Focus. 2001, 11, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cline, M.G.; Burns, K.M.; Coe, J.B; Downing, R.; Durzi, T.; Murphy, M.; Parker, V. AAHA Nutrition and Weight Management Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2021, 57(4), 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glockner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1-e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F. Reproducible, interactive, scalable, and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greengene Database. Available online: https://greengenes.secondgenome.com (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Ewald, J.; Pang, Z.; Shiri, T.; Xia, J. MicrobiomeAnalyst 2.0: comprehensive statistical, functional and integrative analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 5, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Wahab, A.; Zeiger, A.L.; Chuppava, B.; Visscher, C.; Kamphues, J. Effects of poultry by-products inclusion in dry food on nutrient digestibility and fecal quality in Beagle dogs. PLoS One 2022, 17(11), e0276398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, N.J.; Sumanasekera, N.T.; Raffan, E. Obesity risk factors in British Labrador retrievers: Effect of sex, neuter status, age, chocolate coat colour and food motivation. Vet. Rec. 2023, e3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, G.F.E.; Pezzali, J.G.; Kessler, A.dM.; Trevizan, L. Inclusion of exogenous enzymes to feathers during processing on the digestible energy content of feather meal for adult dogs. R. Bras. Zootec. 2016, 45, 288–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, C.; Humbert, D.; Zentek, J.; Denis, S.; Priymenko, N.; Apper, E.; Blanquet-Diot, S. From Chihuahua to Saint-Bernard: how did digestion and microbiota evolve with dog sizes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5086–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, I.; Kim, M.J. Comparison of Gut Microbiota of 96 Healthy Dogs by Individual Traits: Breed, Age, and Body Condition Score. Animals (Basel) 2021, 18, 11-2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, G.; Xu, X. Influence of stewing time on the texture, ultrastructure and in vitro digestibility of meat from the yellow-feathered chicken breed. Anim. Sci. J. 2018, 89, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Bhat, Z.F., Gounder, R.S., Mohamed Ahmed, I.A., Al-Juhaimi, F.Y., Ding, Y., Bekhit, A.E.A. Effect of Dietary Protein and Processing on Gut Microbiota-A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 2022; 14, 153. [CrossRef]

- Do, S.; Phungviwatnikul, T.; de Godoy, M.R.C.; Swanson, K.S. Nutrient digestibility and fecal characteristics, microbiota, and metabolites in dogs fed human-grade foods. J. Anim. Sci, 2021; 1, 99(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; An., J.U.; Kim, W.; Lee, S.; Cho, S. Differences in the gut microbiota of dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) fed a natural diet or a commercial feed revealed by the Illumina MiSeq platform. Gut Pathog 2021, 21, 9–68. [CrossRef]

- Bermingham, E.N.; Maclean, P.; Thomas, D.G.; Cave, N.J.; Young, W. Key bacterial families (Clostridiaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae and Bacteroidaceae) are related to the digestion of protein and energy in dogs. PeerJ. 2017, 5, e3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, M.; Dal Monego, S.; Conte, G.; Sgorlon, S.; Stefanon, B. Raw meat-based diet influences fecal microbiome and end products of fermentation in healthy dogs. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 28, 13–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankel, J.; Abd El-Wahab, A.; Grone, R.; Keller, B.; Galvez, E.; Strowig, T.; Visscher, C. Fecal Microbiota of Dogs Offered a Vegetarian Diet with or without the Supplementation of Feather Meal and either Cornmeal, Rye or Fermented Rye: A Preliminary Study. Microorganisms 2020, 6, 8–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.R.; Shmalberg, J.; Tanprasertsuk, J.; Perry, L.; Massey, D.; Honaker, R.W. Characterization of gut microbiomes of household pets in the United States using a direct-to-consumer approach. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0227289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.M.; Pinna, C.; Biagi, G.; Stefanelli, C.; Maia, M.R.G.; Matos, E.; Segundo, M.A.; Fonseca, A.J.M.; Cabrita, A.R.J. Supplemental selenium source on gut health: insights on fecal microbiome and fermentation products of growing puppies. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Afflitto, M.; Upadhyaya, A.; Green, A.; Peiris, M. Association Between Sex Hormone Levels and Gut Microbiota Composition and Diversity-A Systematic Review. J Clin. Gastroenterol. 2022, 56, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Org, E.; Mehrabian, M.; Parks, B.W.; Shipkova, P.; Liu, X.; Drake, T.A.; Lusis, A.J. Sex differences and hormonal effects on gut microbiota composition in mice. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BW | BCS | MCS | FCS | ||||||||

| Effects | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Diet | |||||||||||

| CTR | 19.5 | 4.1 | 5.2 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 0.2 | |||

| TRT | 19.6 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.3 | |||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 16.6B | 1.1 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.2 | |||

| Female | 22.6A | 2.5 | 5.2 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 0.3 | |||

| Diet x Time of sampling | |||||||||||

| CTR_T0 | 19.3 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.4a | 0.4 | |||

| CTR_T3 | 19.4 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.5a | 0.2 | |||

| CTR_T7 | 19.6 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.5a | 0.2 | |||

| CTR_T15 | 19.8 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.5a | 0.3 | |||

| CTR_T45 | 19.6 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 2.4a | 0.2 | |||

| TRT_T0 | 19.4 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.2b | 0.3 | |||

| TRT_T3 | 19.5 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.4a | 0.2 | |||

| TRT_T7 | 19.6 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.2b | 0.3 | |||

| TRT_T15 | 19.9 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.2b | 0.3 | |||

| TRT_T45 | 19.7 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.4a | 0.2 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).