Submitted:

19 September 2024

Posted:

20 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

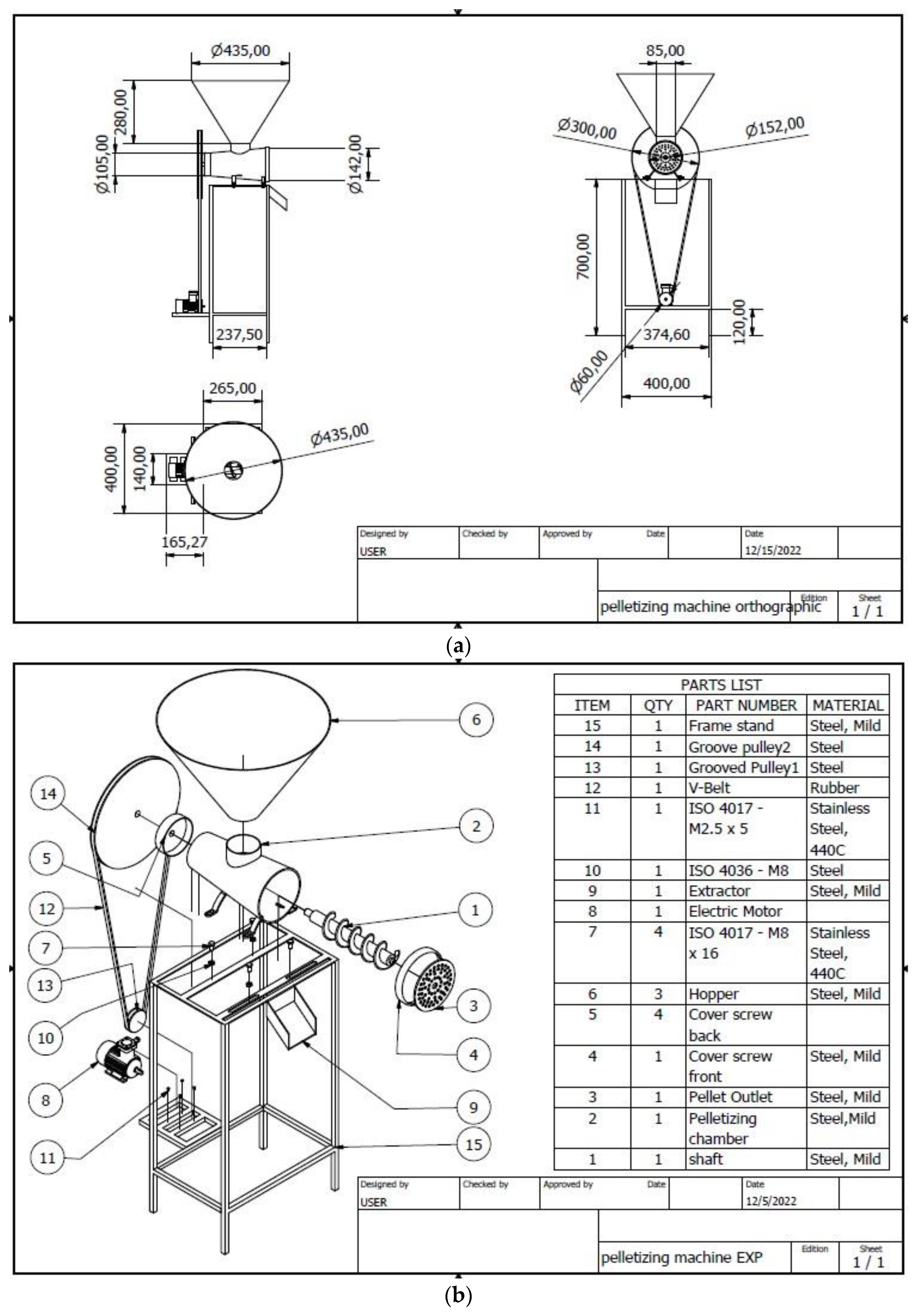

2.1. Description of the Pelleting Machine

2.2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results

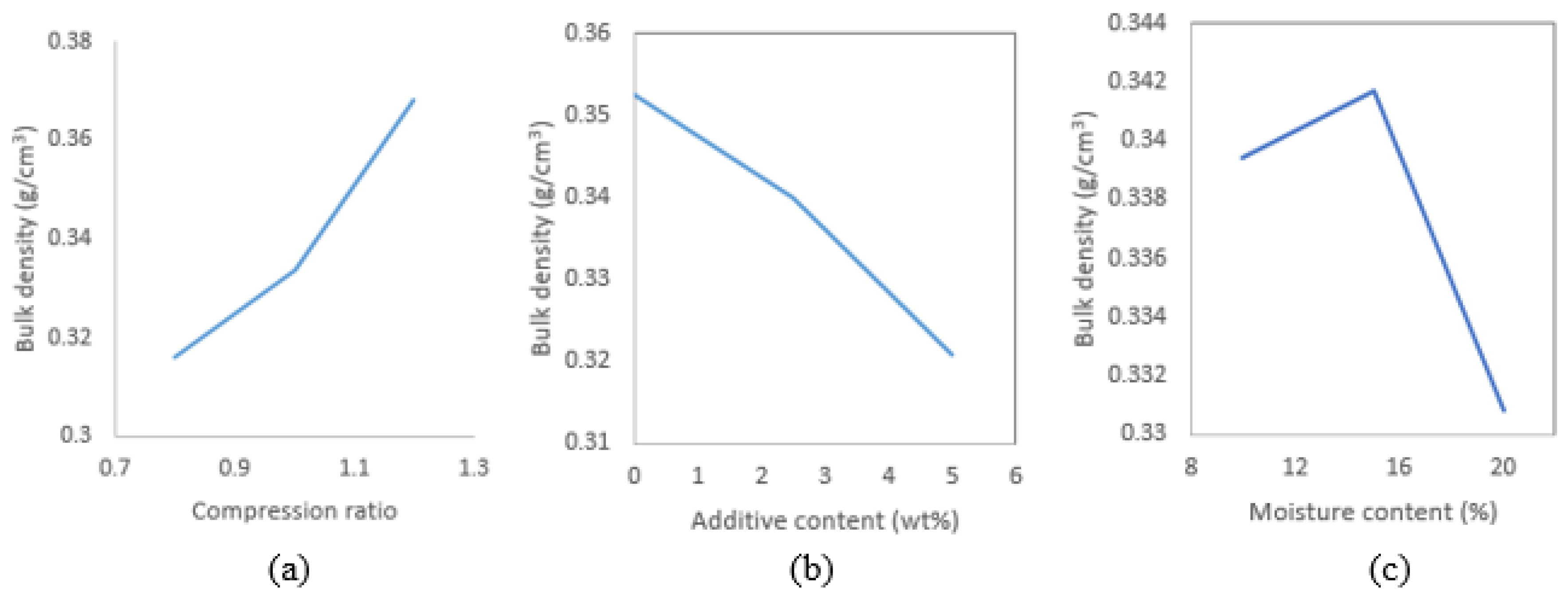

3.1. Bulk Density

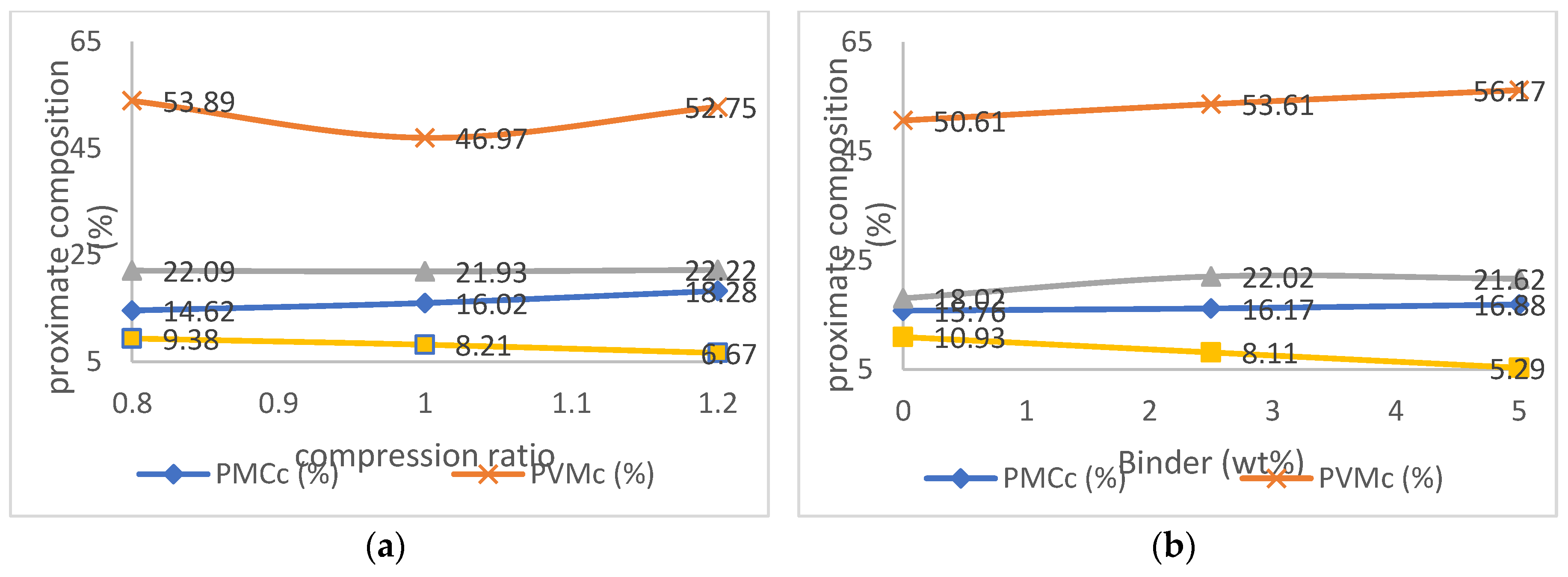

3.2. Proximate Composition

3.2.1. Proximate Composition as Affected by Compression Ratio

3.2.2. Proximate Composition as Affected by Binder Content

3.2.3. Proximate Composition as Affected by Moisture Content

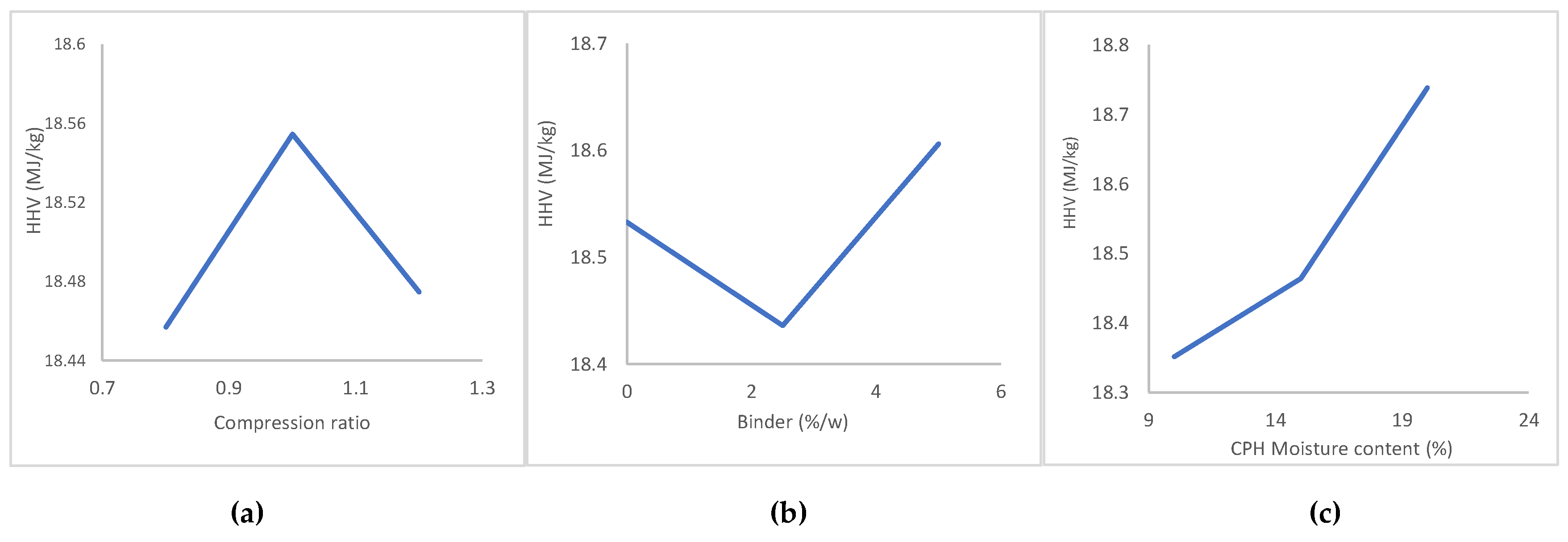

3.2. Higher Heating Value

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jekayinfa, S.O., Linke, B., and Pecenka, R. Biogas production from selected crop residues in Nigeria and estimation of its electricity value. Int J Renew Energy Technol. 2015;6(2):101–18. [CrossRef]

- Jekayinfa, S.O., Orisaleye, J.I., and Pecenka, R. An Assessment of Potential Resources for Biomass Energy in Nigeria. Resources. 2020;9(8):43–92. [CrossRef]

- Ola, F.A. and Jekayinfa, S.O. Pyrolysis of sandbox (Hura crepitans) shell: effect of pyrolysis parameters on biochar yield. Res Agric Eng. 2015;61(4):170–6. [CrossRef]

- Jekayinfa, S.O. and Scholz, V. Assessment of availability and cost of energetically usable crop residues in Nigeria. Nat gas. 2007;24(8):25.

- Beg, M.S., Ahmad, S., Jan, K., and Bashir, K. Status, supply chain and processing of cocoa-A review. Trends food Sci \& Technol. 2017;66:108–16. [CrossRef]

- Kehinde, A.D., Adeyemo, R., and Ogundeji, A.A. Does social capital improve farm productivity and food security? Evidence from cocoa-based farming households in Southwestern Nigeria. Heliyon. 2021;7(3):e06592. [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, A.O. and Sridhar, M.K.C. Effects of Composting on Three CPH Based Fertilizer Materials Used for Cocoa Nursery. Int J Sci Technoledge. 2015;3(12):53.

- Ouattara, L.Y., Kouassi, E.K.A., Soro, D., Soro, Y., Yao, K.B., Adouby, K., et al. Cocoa pod husks as potential sources of renewable high-value-added products: A review of current valorizations and future prospects. BioResources. 2021;16(1):1988–2020. [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I., Jekayinfa, S.O., Braimoh, O.M., and Edhere, V.O. Empirical models for physical properties of abura (Mitragyna ciliata) sawdust briquettes using response surface methodology. Clean Eng Technol. 2022;7:100447. [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I., Abiodun, Y.O., Ogundare, A.A., Adefuye, O.A., Ojolo, S.J., and Jekayinfa, S.O. Effects of Manufacturing Parameters on the Properties of Binderless Boards Produced from Corncobs. Trans Indian Natl Acad Eng. 2022;7(4):1311–25. [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I., Jekayinfa, S.O., Adebayo, A.O., Ahmed, N.A., and Pecenka, R. Effect of densification variables on density of corn cob briquettes produced using a uniaxial compaction biomass briquetting press. Energy Sources, Part A Recover Util Environ Eff. 2018;40(24):3019–28. [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I., Jekayinfa, S.O., Pecenka, R., and Onifade, T.B. Effect of densification variables on water resistance of corn cob briquettes. Agron Res. 2019;17(4):1722–34. [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I., Jekayinfa, S.O., Pecenka, R., Ogundare, A.A., Akinseloyin, M.O., and Fadipe, O.L. Investigation of the effects of torrefaction temperature and residence time on the fuel quality of corncobs in a fixed-bed reactor. Energies. 2022;15(14):5284. [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I., Jekayinfa, S.O., Dittrich, C., Obi, O.F., and Pecenka, R. Effects of feeding speed and temperature on properties of briquettes from poplar wood using a hydraulic briquetting press. Resources. 2023;12(1):12. [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I., Jekayinfa, S.O., Ogundare, A.A., Shittu, M.R., Akinola, O.O., and Odesanya, K.O. Effects of Process Variables on Physico-Mechanical Properties of Abura (Mitrogyna ciliata) Sawdust Briquettes. Biomass. 2024;4(3):671–86. [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I., Ogundare, A.A., Oloyede, C.T., Ojolo, S.J., and Jekayinfa, S.O. Effect of preconditioning and die thickness on pelleting of livestock feed. Aust J Multi-Disciplinary Eng. 2024;20(1):13–25. [CrossRef]

- Jekayinfa, S.O., Ola, F.A., Akande, F.B., Adesokan, M.A., and Abdulsalam, I.A. Modification and Performance Evaluation of a Biomass Pelleting Machine. AgriEngineering. 2024;6(3):2214–28. [CrossRef]

- ASTM E871. Standard test method for moisture analysis of particulate wood fuels. American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) Philadelphia; 2013.

- Ogunlade, C.A. and Aremu, A.K. Energy consumption Pattern as affected by machine operating parameters in mechanically expressing oil from Pentaclethra macrophylla: Modeling and optimization. Clean Eng Technol. 2021;5:100300. [CrossRef]

- Ogunlade, C.A. and Aremu, A.K. Modeling and optimisation of oil recovery and throughput capacity in mechanically expressing oil from African oil bean (Pentaclethra macrophylla Benth) kernels. J Food Sci Technol. 2020;57(11):4022–31. [CrossRef]

- Ogunlade, C.A. and Aremu, A.K. Influence of processing conditions on some physical characteristics of vegetable oil expressed mechanically from Pentaclethra macrophylla Benth kernels: Response surface approach. J Food Process Eng. 2019;42(2):e12967. [CrossRef]

- EN 14961-2. Solid biofuels-Fuel specifications and classes-Part 2: Wood pellets for non-industrial use. European Union; 2011.

- ASTM E873-82. Standard test method for bulk density of densified particulate biomass fuels. Am Soc Test Mater. 2014;

- Japhet, J.A., Tokan, A., and Muhammad, M.H. Production and characterization of rice husk pellet. Am J Eng Res. 2015;4(12):112–9.

- ASTM D1102. standard test method for ash in wood. ASTM International West Conshohocken; 2013.

- Ismail, B. Ash Content Determination. Food analysis laboratory manual. Springer, Cham; 2017. 117–119 p. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. Effects of sample size, dry ashing temperature and duration on determination of ash content in algae and other biomass. Algal Res. 2019;40:101486. [CrossRef]

- ASTM E872. Standard test method for volatile matter in the analysis of particulate wood fuels. Annual Book of ASTM Standard, American Society for Testing and Materials. 2013.

- García, R., Pizarro, C., Lavín, A.G., and Bueno, J.L. Biomass proximate analysis using thermogravimetry. Bioresour Technol. 2013;139:1–4. [CrossRef]

- ASTM E870. Standard Test Methods for Analysis of Wood Fuels. American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) Philadelphia.; 2019.

- Imran, A.M., Widodo, S., and Irvan, U.R. Correlation of fixed carbon content and calorific value of South Sulawesi Coal, Indonesia. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2020. p. 012–106. [CrossRef]

- Acar, S., Ayanoglu, A., and Demirbas, A. Determination of higher heating values (HHVs) of biomass fuels. Uluslararasi Yakitlar Yanma Ve Yangin Derg. 2016;(3):1–3.

- Okewole, O.T. and Igbeka, J. Effect of some operating parameters on the performance of a pelleting press. Agric Eng Int CIGR J. 2016;18(1):326–38.

- Jekayinfa, S.O., Abdulsalam, I.A., Ola, F.A., Akande, F.B., and Orisaleye, J.I. Effects of binders and die geometry on quality of densified rice bran using a screw-type laboratory scale pelleting machine. Energy Nexus. 2024;100275. [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, D., Shahi, C., and Leitch, M. Effect of Additives on Wood Pellet Physical and Thermal Characteristics: A Review. ISRN For. 2013;2013:1–6. [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S. and Wright, C.T. A review on biomass densification technologie for energy application. 2010; [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E.A., Pasache, M.B., and Garcia, M.E. Development of briquettes from waste wood (sawdust) for use in low-income households in Piura, Peru. In: Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering. 2014. p. 2–4.

- Ikelle, I.I. and Anyigor, C. Comparative thermal analysis of the properties of coal and corn cob briquettes. IOSR J Appl Chem. 2014;7(6):93–7.

- Čolović, R., Vukmirović, Dj., Matulaitis, R., Bliznikas, S., Uchockis, V., Juškienie, V., et al. Effect of die channel press way length on physical quality of pelleted cattle feed. Food Feed Res. 2010;37(1):1–6.

- Jamradloedluk, J. and Lertsatitthanakorn, C. Influences of Mixing Ratios and Binder Types on Properties of Biomass Pellets. In: Energy Procedia. Elsevier B.V.; 2017. p. 1147–52. [CrossRef]

- González, W.A., López, D., and Pérez, J.F. Biofuel quality analysis of fallen leaf pellets: Effect of moisture and glycerol contents as binders. Renew Energy. 2020;147:1139–50. [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, M., Asghar, A., Ramzan, N., Sajjadi, B., and Chen, W. yin. Biomass densification: Effect of cow dung on the physicochemical properties of wheat straw and rice husk based biomass pellets. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2019;122:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G., Brito, T.M., Da Silva, J.G.M., Minini, D., Dias Júnior, A.F., Arantes, M.D.C., et al. Wood waste pellets as an alternative for energy generation in the Amazon Region. BioEnergy Res. 2023;16(1):472–83. [CrossRef]

| Run | A | B (%/w) | C (%) | BD (g/cm3) | PMC (%) | PVM (%) | PFC (%) | ASH (%) | HHV (MJ/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 15 | 0.360 | 18.02 | 50.82 | 22.31 | 8.44 | 18.492 |

| 2 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 20 | 0.290 | 16.45 | 55.75 | 21.50 | 5.88 | 18.894 |

| 3 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 10 | 0.337 | 15.50 | 51.74 | 21.85 | 10.45 | 18.402 |

| 4 | 0.8 | 5.0 | 15 | 0.291 | 15.77 | 55.45 | 21.30 | 6.86 | 18.831 |

| 5 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 20 | 0.360 | 16.28 | 48.61 | 22.82 | 11.85 | 18.592 |

| 6 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 10 | 0.409 | 16.67 | 54.14 | 21.25 | 7.44 | 18.284 |

| 7 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 15 | 0.354 | 13.22 | 51.26 | 23.10 | 12.99 | 18.647 |

| 8 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 15 | 0.354 | 16.00 | 53.97 | 22.03 | 8.00 | 18.437 |

| 9 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 15 | 0.323 | 16.13 | 54.52 | 21.94 | 7.41 | 18.419 |

| 10 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 20 | 0.340 | 15.67 | 52.76 | 22.03 | 9.04 | 18.437 |

| 11 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 10 | 0.332 | 16.19 | 57.83 | 21.35 | 4.91 | 18.304 |

| 12 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 15 | 0.340 | 15.60 | 53.41 | 22.00 | 8.94 | 18.431 |

| 13 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 20 | 0.333 | 19.30 | 50.40 | 23.00 | 7.30 | 18.627 |

| 14 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 10 | 0.280 | 13.83 | 56.08 | 21.93 | 8.63 | 18.418 |

| 15 | 1.2 | 5.0 | 15 | 0.370 | 19.12 | 55.63 | 22.33 | 3.49 | 18.496 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.0145 | 6 | 0.0024 | 17.04 | 0.0004 | significant |

| A-CR | 0.0053 | 1 | 0.0053 | 37.65 | 0.0003 | significant |

| B-additive | 0.0020 | 1 | 0.0020 | 14.32 | 0.0054 | significant |

| C-MC | 0.0001 | 1 | 0.0001 | 1.04 | 0.3384 | not significant |

| AB | 0.0013 | 1 | 0.0013 | 9.30 | 0.0158 | significant |

| AC | 0.0046 | 1 | 0.0046 | 32.53 | 0.0005 | significant |

| BC | 0.0011 | 1 | 0.0011 | 7.44 | 0.0260 | significant |

| ABC | 0.0000 | 0 | ||||

| Pure Error | 0.0005 | 2 | 0.0002 | |||

| Cor Total | 0.0157 | 14 | ||||

| Fit Statistics | Std. Dev. | 0.0119 | R² | 0.9274 | ||

| Mean | 0.3382 | Adj. R² | 0.8730 | |||

| C.V.% | 3.52 | Pred. R² | 0.7426 | |||

| Adeq Prec. | 15.2426 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 33.80 | 6 | 5.63 | 12.01 | 0.0013 | Significant |

| A-CR | 26.72 | 1 | 26.72 | 56.93 | < 0.0001 | Significant |

| B-additive | 2.54 | 1 | 2.54 | 5.42 | 0.0483 | Significant |

| C-MC | 3.80 | 1 | 3.80 | 8.09 | 0.0217 | Significant |

| AB | 0.5256 | 1 | 0.5256 | 1.12 | 0.3208 | not significant |

| AC | 0.1560 | 1 | 0.1560 | 0.3325 | 0.5801 | not significant |

| BC | 0.0676 | 1 | 0.0676 | 0.1440 | 0.7142 | not significant |

| ABC | 0.0000 | 0 | ||||

| Pure Error | 0.1526 | 2 | 0.0763 | |||

| Cor Total | 37.56 | 14 | ||||

| Moisture cocoa | Std. Dev. | 0.6851 | R² | 0.9000 | ||

| Mean | 16.25 | Adjusted R² | 0.8251 | |||

| C.V.% | 4.22 | Predicted R² | 0.5232 | |||

| Adeq Precision | 11.6832 | |||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 83.61 | 6 | 13.93 | 17.85 | 0.0003 | Significant |

| A-CR | 2.60 | 1 | 2.60 | 3.33 | 0.1055 | not significant |

| B-additive | 61.77 | 1 | 61.77 | 79.11 | < 0.0001 | significant |

| C-MC | 18.82 | 1 | 18.82 | 24.10 | 0.0012 | significant |

| AB | 0.0961 | 1 | 0.0961 | 0.1231 | 0.7348 | not significant |

| AC | 0.0441 | 1 | 0.0441 | 0.0565 | 0.8181 | not significant |

| BC | 0.2756 | 1 | 0.2756 | 0.3530 | 0.5688 | not significant |

| ABC | 0.0000 | 0 | ||||

| Pure Error | 0.6161 | 2 | 0.3080 | |||

| Cor Total | 89.85 | 14 | ||||

| VM cocoa | Std. Dev. | 0.8836 | R² | 0.9305 | ||

| Mean | 53.49 | Adjusted R² | 0.8783 | |||

| C.V.% | 1.65 | Predicted R² | 0.6899 | |||

| Adeq Precision | 14.2882 | |||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 4.74 | 9 | 0.5264 | 36.90 | 0.0005 | significant |

| A-CR | 0.0351 | 1 | 0.0351 | 2.46 | 0.1775 | not significant |

| B-additive | 1.62 | 1 | 1.62 | 113.56 | 0.0001 | significant |

| C-MC | 1.10 | 1 | 1.10 | 77.29 | 0.0003 | significant |

| AB | 0.8281 | 1 | 0.8281 | 58.05 | 0.0006 | significant |

| AC | 0.6806 | 1 | 0.6806 | 47.71 | 0.0010 | significant |

| BC | 0.1681 | 1 | 0.1681 | 11.78 | 0.0186 | significant |

| A² | 0.1807 | 1 | 0.1807 | 12.67 | 0.0162 | significant |

| B² | 0.0088 | 1 | 0.0088 | 0.6151 | 0.4684 | not significant |

| C² | 0.0931 | 1 | 0.0931 | 6.52 | 0.0510 | not significant |

| ABC | 0.0000 | 0 | ||||

| Pure Error | 0.0042 | 2 | 0.0021 | |||

| Cor Total | 4.81 | 14 | ||||

| FC cocoa | Std. Dev. | 0.1194 | R² | 0.9852 | ||

| Mean | 22.05 | Adjusted R² | 0.9585 | |||

| C.V.% | 0.5417 | Predicted R² | 0.7747 | |||

| Adeq Precision | 18.8168 | |||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 79.84 | 6 | 13.31 | 20.90 | 0.0002 | significant |

| A-CR | 14.72 | 1 | 14.72 | 23.12 | 0.0013 | significant |

| B-binder | 63.79 | 1 | 63.79 | 100.21 | < 0.0001 | significant |

| C-MC | 0.8712 | 1 | 0.8712 | 1.37 | 0.2757 | not significant |

| AB | 0.3481 | 1 | 0.3481 | 0.5468 | 0.4807 | not significant |

| AC | 0.0756 | 1 | 0.0756 | 0.1188 | 0.7392 | not significant |

| BC | 0.0462 | 1 | 0.0462 | 0.0726 | 0.7944 | not significant |

| ABC | 0.0000 | 0 | ||||

| Pure Error | 1.19 | 2 | 0.5954 | |||

| Cor Total | 84.94 | 14 | ||||

| Std. Dev. | 0.7979 | R² | 0.9400 | |||

| Mean | 8.11 | Adj. R² | 0.8951 | |||

| C.V.% | 9.84 | Pred. R² | 0.7393 | |||

| Adeq Prec. | 15.3383 | |||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.1455 | 9 | 0.0162 | 46.74 | 0.0046 | significant |

| A-CR | 0.0003 | 1 | 0.0003 | 0.9254 | 0.4070 | not significant |

| B-binder | 0.0136 | 1 | 0.0136 | 39.45 | 0.0081 | significant |

| C-MC | 0.0344 | 1 | 0.0344 | 99.32 | 0.0021 | significant |

| AB | 0.0108 | 1 | 0.0108 | 31.35 | 0.0113 | significant |

| AC | 0.0261 | 1 | 0.0261 | 75.58 | 0.0032 | significant |

| BC | 0.0005 | 1 | 0.0005 | 1.35 | 0.3295 | not significant |

| A² | 0.0037 | 1 | 0.0037 | 10.78 | 0.0463 | significant |

| B² | 0.0013 | 1 | 0.0013 | 3.81 | 0.1459 | not significant |

| C² | 0.0016 | 1 | 0.0016 | 4.74 | 0.1177 | not significant |

| ABC | 0.0000 | 0 | ||||

| Pure Error | 0.0002 | 2 | 0.0001 | |||

| Cor Total | 0.1466 | 12 | ||||

| Std. Dev. | 0.0186 | R² | 0.9929 | |||

| Mean | 18.46 | Adjusted R² | 0.9717 | |||

| C.V.% | 0.1008 | Predicted R² | NA⁽¹⁾ | |||

| Adeq Precision | 21.4865 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).