1. Introduction

Cotton (

Gossypium hirsutum) is the most important fibre crop in the world. Approximately 25 million tons of cotton are produced worldwide per annum with an estimated value of 12 billion USD [

1]. In Australia, the cotton industry is primarily based in the inland regions of New South Wales and southern Queensland generating an annual revenue of 1.9 billion AUD [

2].

Two important diseases of cotton in Australia are black root rot (BRR) and Fusarium wilt caused by

Berkeleyomyces rouxiae and

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

vasinfectum (

Fov) respectively [

2,

3]. Both fungal pathogens are considered hemibiotrophic plant pathogens.

B. rouxiae was formerly known as

Thielaviopsis basicola within the family Ceratocystidaceae [

4].

B. rouxiae first colonises living root tissues and then consumes the root cells causing black discolouration, which results in brittle root tissues and reduced water and nutrient uptake by the plants [

5]. Severe black root rot infection typically results in stunted seedlings which can delay flowering of the plants [

6] but it does not often cause plant death in the cotton fields [

3]. Yield losses of up to 10% caused by BRR have been reported in Australia [

3].

Fov is a soil-borne pathogen that colonises the vascular system of the plants. Its proliferation inside the water-conducting vessels causing blockage of water supply to the upper parts of the plant, leads to leaf wilting, chlorosis, necrosis, vascular discolouration, plant stunting, defoliation and plant death [

7]. Globally there are multiple races of

Fov, but isolates originating from Australia belong to their own distinct lineage [

8,

9]. Vegetative compatibility groupings (VCGs) are also used to classify

Fov isolates. Initially, in a study by Fernandez et al. (1994), ten VCGs were identified in

Fov pathogenic to cotton, these being 0111-01110, with the first 3 digits representing

Fov and the last number (1-10) identifying the VCG subgroup. They found that each of the races 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 corresponded to a distinct VCG [

10]. The Australian

Fov isolates were then identified with distinct VCGs, 01111 and 01112 [

11]. Studies showed that most isolates within the same VCG had the same rDNA and mtDNA haplotypes although multiple haplotypes were observed in some cases. Overall, three ancestral lineages of

F. oxysporum pathogenic towards cotton were observed which includes: race 3 which is common in Egypt, Sudan, and Israel and considered a single clone; the Australian biotypes; and the all others including Californian races and race 1 from the Americas, races 7 and 8 from China, and race 4 from India [

7].

In recent years, many isolates of

F. oxysporum from cotton seedlings exhibited atypical that wilt symptoms and that do not phylogenetically conform to the standard Australian biotypes have been identified [

12]. This highlights a need to investigate further the potential of

F. oxysporum to cause disease on cotton plants. There are currently a number of undetermined VCGs within

Fov [

13] as well as the presence of Australian isolates that are not compatible with VCG01111 and VCG0112 but never-the-less showed the ability to infect cotton plants [

2,

12]. This study aims to address whether minor or mildly virulent races of

Fov may be contributing to the overall pathogenicity of the

F. oxysporum populations in cotton growing regions of Australia.

Pathogenicity of black root rot pathogen relied on using naturally or artificially infested soil or commercial potting mix, respectively [

14]. On the other hand, there is an array of methods such as root dip [

15], soil drench [

16], stem puncture, and agar plugs amended potting mix [

17] to assess pathogenicity of cotton-

Fusarium spp. Different inoculation methods also resulted in different implications. Therefore, in this study we sought to assess virulence of both black root rot pathogen and cotton-

Fusarium spp. using a rapid and robust seedling and soil inoculation assay using a spore suspension obtained from unfiltered liquid cultures. Assessing pathogenicity of these important cotton pathogens is critical in understanding not just virulence but also detecting new biotypes that may contribute to the evolution of pathogen populations across the wide cotton growing regions.

4. Discussion

In this study, we successfully employed a simple and robust inoculation method to assess and differentiate virulence of both

B. rouxiae and

Fusarium spp. on cotton. Using unfiltered suspension for root dipping and soil inculcation, virulence of

B. rouxiae was visually detected at 15 dpi in comparison to 19 to 30 dpi using artificially or naturally infested soil [

14]. Similarly, screening for Fusarium wilt typically takes 1 - 3 months for disease phenotypes to be expressed and assessed in different plant species [

29,

30,

31]. In our study, we were able to terminate and assess the aggressiveness of cotton-

Fusarium spp. as soon as 15 dpi. A seedling screening system such as this can be scaled up to provide preliminary assays for pathogen virulence at a high throughput. A reliable screening system is important in determining the host range of specific plant pathogens and genetics of plant and pathogen interactions.

Spores and mycelia were not filtered before being applied to the plants and the soil. Given that spore production varies significantly amongst the different

Fov and

Berkeleyomyces isolates (

Figure S3-S4), a pre-determined number of spores per pot can still lead to variations in the build-up of inoculum for infection. Instead, sufficient spores and mycelia were applied to the soil at a high density. Fine roots and the new root growth in soil saturated with the fungus can achieve good infection rates, thus providing uniformity in infection levels. Furthermore, plant growth under a controlled environment with a set of constant parameters can reduce variability in growth and varied disease expression due to environmental effects. Although varied amount of spores and mycelia in the inoculum applied may also contribute to varied disease severity.

The result shows that

B. rouxiae BRR4 and 22BRR77 were clearly pathogenic towards cotton. The discolourations in the stems were distinct and appeared more severe when compared to the discolouration levels in the roots (

Figure 7). This contrasts the pot trial of another study in which root discolouration appeared to be the most dominant trait associated with the black root rot of cotton [

3]. In that study,

Berkeleyomyces spore culture was mixed with the potting mix and seeds are directly sown into the

Berkeleyomyces-infested soil. This inoculation method mimics the field conditions in which residual Berkeleyomyces spores in the soil provides a natural inoculum for the germinating cotton seeds.

In plants severely affected by 22BRR77, some discolouration was observed in the vascular regions of the stems. However, black root rot infection is commonly observed on the epidermis of below ground hypocotyls and roots. Vascular infection associated with

Berkeleyomyces is rarely detected in Australia. Although it has been shown that in the presence of root-knot nematodes,

B. basicola can induce necrosis within the vascular tissues of cotton plants [

32]. Therefore, open lesions and wounds caused by nematodes or wounds such as those artificially induced during root dipping and washing in our study can potentially lead to the movement of

B. rouxiae through the vasculature in cotton plants. Never-the-less, both BRR2 and 22BRR77 were only recovered at a low level in the arial parts of the plants suggesting that their ability to infect plants is primarily through the roots and lower parts of the plants. The strong discolouration on the stem surface could be used as a trait marker to identify and confirm Berkeleyomyces infections in the cotton field. Despite being identified as

B. rouxiae, RVB4.1 and StrB22 did not have any effects on plant growth, suggesting that there is variability in the ability of

B. rouxiae strains to infect specific plant species. This may potentially be explained by differences in the effector profile of these isolates. Pac-bio sequencing of both RVB4.1 and 22BRR77 are underway. Differences between the genomes of these two isolates will be investigated.

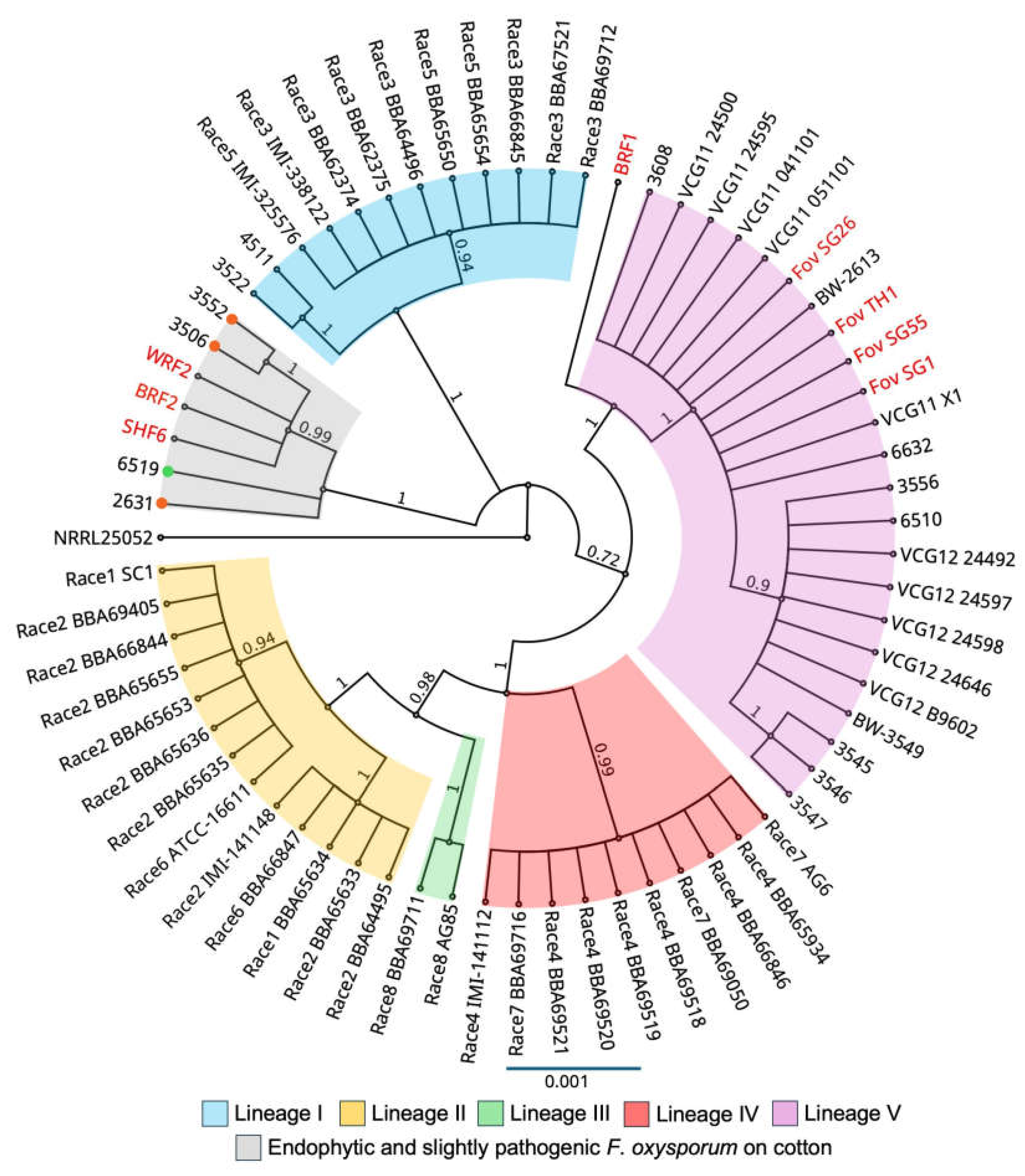

DNA sequences have been used to investigate the evolutionary relationships among the

Fov races. Based on multiple conserved gene sequences, different races of

Fov were separated into five distinct lineages [

7,

9,

16,

33]. In our study, the four

Fov isolates conformed to the other Australian

Fov biotypes in lineage V and the SIX gene analysis further supported their phylogenetic positions within this lineage. Recently, it was shown that non-Australian

Fov isolates are a part of lineage V and can be distinguished phylogenetically from the Australian isolates [

33]. Taken together, these results support the proposal that the different lineages of

Fov are independently evolving [

10], highlighting a need to further investigate the diversity of

Fov isolates beyond the current classification system.

All 4

F. oxysporum isolates were isolated from the hypocotyls of cotton seedlings displaying the collar rot disease [

12]. They were not initially identified as

Fov due to the fact that the plants the isolates were obtained from did not display Fusarium wilt symptoms. Effector gene profiling based on the presence or absence of SIX genes has been used to differentiate the different pathogen forms of

F. oxysporum as well as

F. oxysporum endophytes in a previous study [

19]. By using this diagnostic system, it was determined that none of the 4

F. oxysporum isolates used in this study possessed any SIX genes. Despite not having any SIX genes, these isolates were able to colonise the vascular tissues within the stems and cause disease on cotton plants. These results suggest that they behave in a manner characteristic of a vascular wilt pathogen.

Fo BRF1 share the same evolutionary descent as lineage V but appeared to form a lineage that is independent of lineage V. Similarly,

Fo BRF2,

Fo SHF6 and

Fo WRF2 were clustered within a lineage that is independent of the Fov lineages. This lineage was previously defined by

F. oxysporum isolates that were endophytic or slightly pathogenic on cotton cultivars [

21]. Despite having reduced virulence on cotton cultivars, the authors observed that these isolates were highly pathogenic on a wild relative of cotton, therefore suggesting that these cotton hosts could serve as inoculum reservoir for the co-occurrence of these 'wild'

Fov populations in the field [

21]. Moreover, selection pressures exerted by the changing environment and

Fov resistance in cotton cultivars may have favoured the selection of the 'wild'

Fov populations with enhanced pathogenicity. The 4

F. oxysporum isolates used in this study were part of a collection consisting of 186

F. oxysporum isolates recovered from cotton seedlings showing the collar rot disease [

12]. Fusarium wilt symptoms were not observed on these plants. Out of this collection, only 21.5% of the isolates grouped with the Australian biotypes lineage V while 78.5% of the isolates clustered with the other lineages [

12]. Our results are consistent with these findings. Taken together, these results collectively suggests that under disease inducive conditions,

F. oxysporum strains can act opportunistically on cotton plants and their ability to colonise and exert virulence on hosts are dependent on host genotypes. The specificity of the Fusarium-cotton interactions may have been encoded by the cotton hosts. Thus, the

F. oxysporum populations may have been enriched for mildly virulent strains that are capable of causing

Fov-like symptoms on cotton plants in the field. They apparently lack the SIX gene effectors and are part of lineages that are independent of the

Fov phylogroups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., E.A.B.A. and D.M.G.; methodology, A.C.; software, A.C.; validation, A.C., E.A.B.A. and D.M.G.; formal analysis, A.C.; investigation, A.C.; resources, D.P.L., L.J.S., D.K.; data curation, A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.C., D.P.L., L.J.S., D.K., E.A.B.A. and D.M.G.; supervision, A.C., E.A.B.A. and D.M.G.; project administration, E.A.B.A and D.M.G.; funding acquisition, E.A.B.A. and D.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

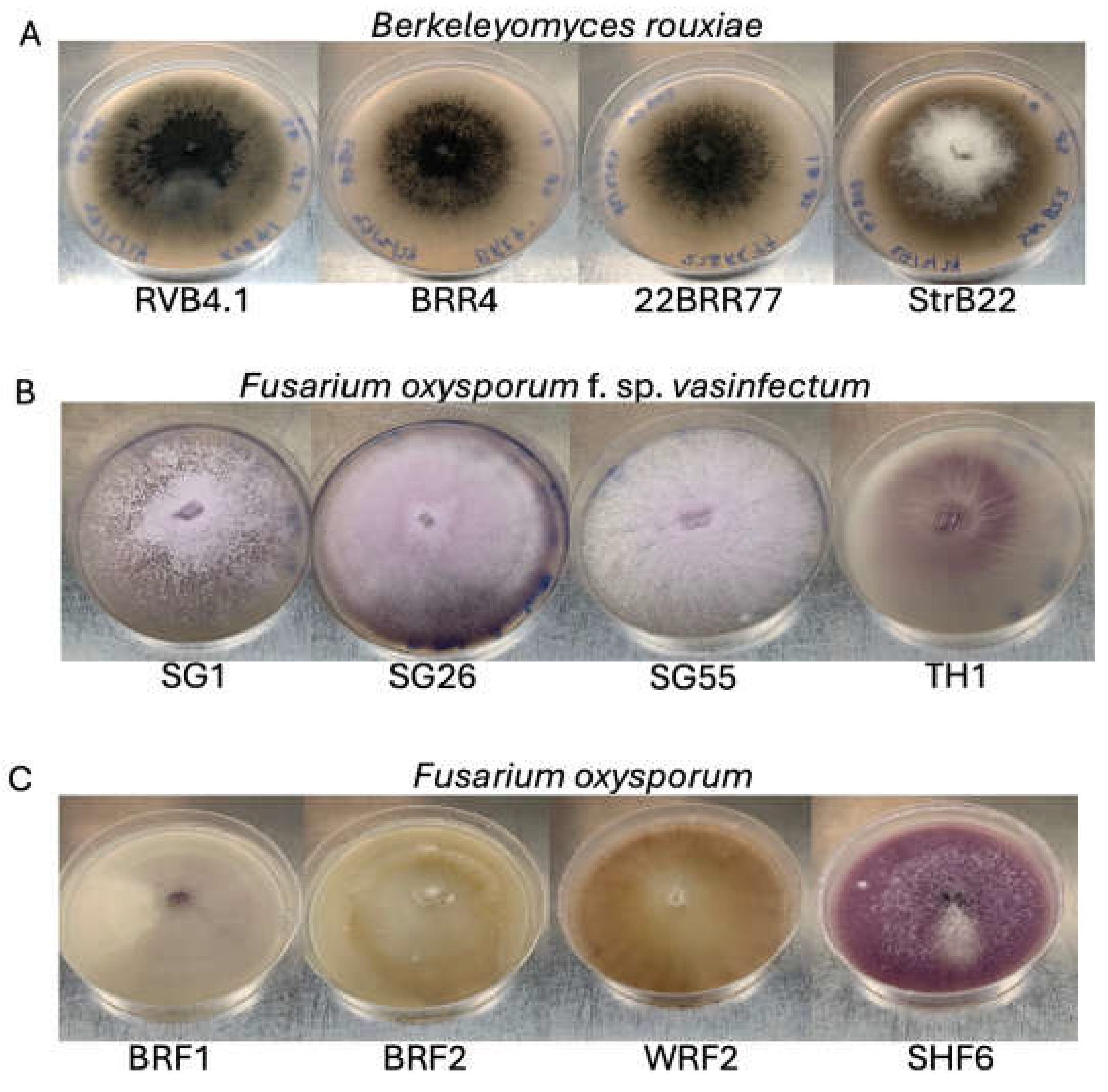

Figure 1.

Colony morphology of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae and Fusarium oxysporum isolates used in this study. A) B. rouxiae isolates RVB4.1, BRR4, 22BRR77, and StrB22 grown for 2 weeks on 10% carrot agar. B) Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum isolates Fov SG1, Fov SG26, Fov SG55, and Fov TH1 grown for 2 weeks on half-strength potato dextrose agar (PDA). (C) Fusarium oxsporum isolates Fo BRF1, Fo BRF2, Fo WRF2, and Fo SHF6 grown for 2 weeks on half-strength PDA.

Figure 1.

Colony morphology of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae and Fusarium oxysporum isolates used in this study. A) B. rouxiae isolates RVB4.1, BRR4, 22BRR77, and StrB22 grown for 2 weeks on 10% carrot agar. B) Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum isolates Fov SG1, Fov SG26, Fov SG55, and Fov TH1 grown for 2 weeks on half-strength potato dextrose agar (PDA). (C) Fusarium oxsporum isolates Fo BRF1, Fo BRF2, Fo WRF2, and Fo SHF6 grown for 2 weeks on half-strength PDA.

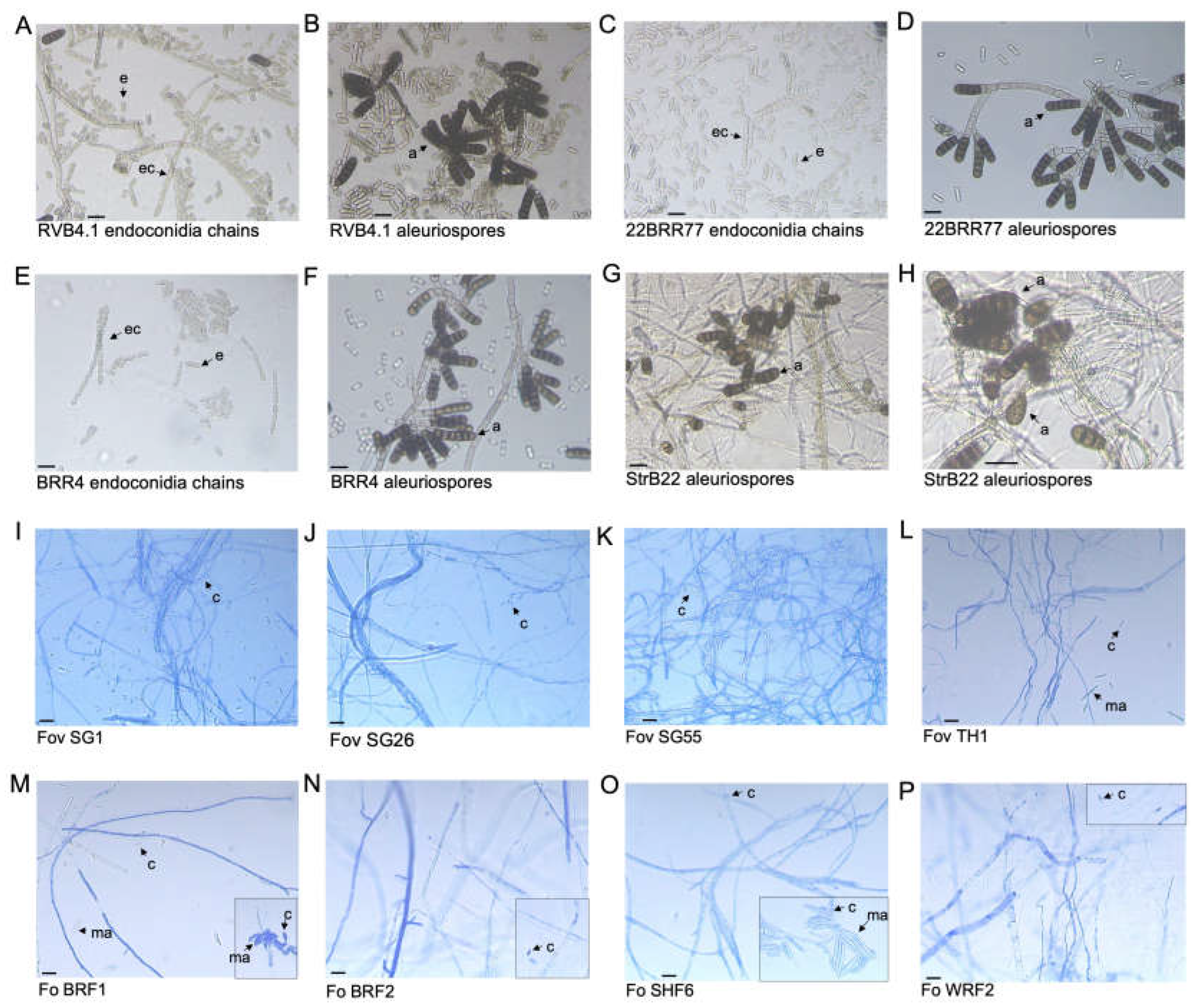

Figure 2.

Compound microscopic images of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae and Fusarium oxysporum isolates used in this study. (A-B) B. rouxiae isolate RVB4.1. (C-D) B. rouxiae isolate 22BRR77. (E-F) B. rouxiae isolate BRR4 (G-H) B. rouxiae isolate StrB22. (I) Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum isolate (Fov) SG1. (J) Fov isolate SG26. (K) Fov isolate SG55. (L) Fov isolate TH1. (M) Fusarium oxsporum (Fo) isolate BRF1. Inset: a cluster of conidia. (N) Fo isolate BRF2. Inset: microconidia. (O) Fo isolate SHF6. Inset: a cluster of macroconidia. (P) Fo isolate WRF2. Inset: microconidia. e = endoconidia; ec = endoconidia chains; a = aleuriospores; c = microconidia; ma = macroconidia. Bars indicate a scale of 15 µm.

Figure 2.

Compound microscopic images of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae and Fusarium oxysporum isolates used in this study. (A-B) B. rouxiae isolate RVB4.1. (C-D) B. rouxiae isolate 22BRR77. (E-F) B. rouxiae isolate BRR4 (G-H) B. rouxiae isolate StrB22. (I) Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum isolate (Fov) SG1. (J) Fov isolate SG26. (K) Fov isolate SG55. (L) Fov isolate TH1. (M) Fusarium oxsporum (Fo) isolate BRF1. Inset: a cluster of conidia. (N) Fo isolate BRF2. Inset: microconidia. (O) Fo isolate SHF6. Inset: a cluster of macroconidia. (P) Fo isolate WRF2. Inset: microconidia. e = endoconidia; ec = endoconidia chains; a = aleuriospores; c = microconidia; ma = macroconidia. Bars indicate a scale of 15 µm.

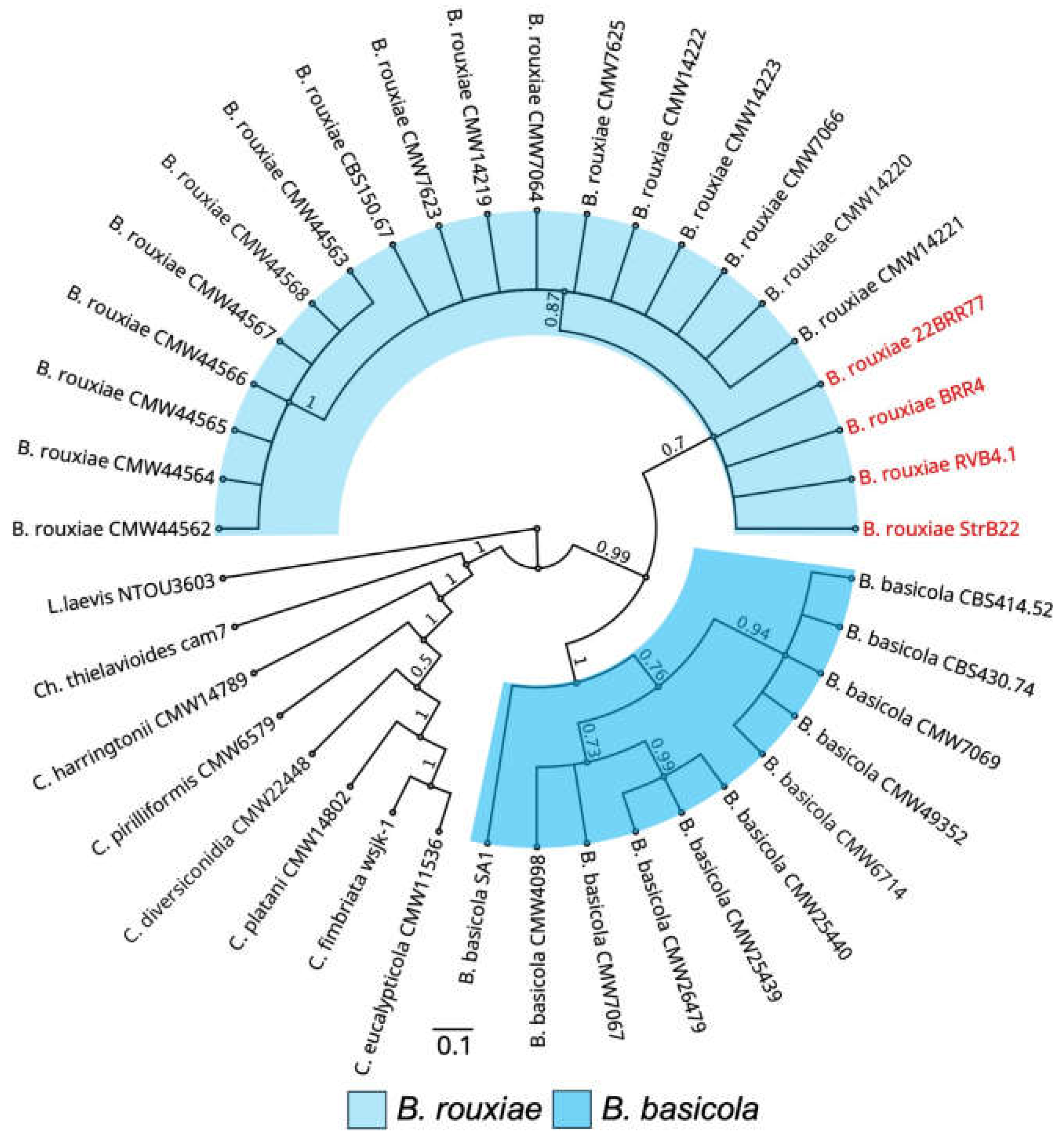

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic positions of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae isolates within the genus Ceratocystidaceae determined using Bayesian inference. Phylogenetic relationships reconstructed using concatenated sequences of MCM7 and RPB2 genes. Bars indicate a scale range of 0.05. Node values show the posterior probability. Genus is abbreviated as Ch. for Chalaropsis, C. for Ceratocystis, B. for Berkeleyomyces, L. for Lignincola.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic positions of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae isolates within the genus Ceratocystidaceae determined using Bayesian inference. Phylogenetic relationships reconstructed using concatenated sequences of MCM7 and RPB2 genes. Bars indicate a scale range of 0.05. Node values show the posterior probability. Genus is abbreviated as Ch. for Chalaropsis, C. for Ceratocystis, B. for Berkeleyomyces, L. for Lignincola.

Figure 4.

Bayesian phylogeny of the

Fusarium oxysporum isolates inferred from combined analysis of translation elongation factor, mitochondrial small subunit rDNA, nitrate reductase, and phosphate permease gene sequences.

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

vasinfectum isolates are classified into lineages I-V [

7,

9]. The endophytic and slightly pathogenic

F. oxysporum isolates from cotton were classified as a distinct lineage [

21] and these isolates were characterised to be either non-pathogenic (green circle) or slightly pathogenic (orange circles) on cotton plants. VCG01111 and VCG01112 are abbreviated as VCG11 and VCG12, respectively. Bars indicate a scale range of 0.05. Node values show the posterior probability.

Figure 4.

Bayesian phylogeny of the

Fusarium oxysporum isolates inferred from combined analysis of translation elongation factor, mitochondrial small subunit rDNA, nitrate reductase, and phosphate permease gene sequences.

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

vasinfectum isolates are classified into lineages I-V [

7,

9]. The endophytic and slightly pathogenic

F. oxysporum isolates from cotton were classified as a distinct lineage [

21] and these isolates were characterised to be either non-pathogenic (green circle) or slightly pathogenic (orange circles) on cotton plants. VCG01111 and VCG01112 are abbreviated as VCG11 and VCG12, respectively. Bars indicate a scale range of 0.05. Node values show the posterior probability.

Figure 5.

Bayesian inference phylogenetic reconstruction of Secreted In Xylem 6 gene (SIX6) in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum isolates and isolates from other formae speciales of Fusarium oxysporum. Focuc = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum; Fol = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici; Fopas = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. passiflora; Fon = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum; Fop = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. pisi; Foradc = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-cucumerinum; Foses = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. sesami. Bars indicate a scale range of 0.05. Node values show the posterior probability.

Figure 5.

Bayesian inference phylogenetic reconstruction of Secreted In Xylem 6 gene (SIX6) in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum isolates and isolates from other formae speciales of Fusarium oxysporum. Focuc = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum; Fol = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici; Fopas = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. passiflora; Fon = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum; Fop = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. pisi; Foradc = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-cucumerinum; Foses = Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. sesami. Bars indicate a scale range of 0.05. Node values show the posterior probability.

Figure 6.

Pathogenicity testing of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae isolates on cotton cv. Sicot746 B3F. (A) Plants at harvest (15 — 20 days post inoculation). (B) Total (above and below ground) plant weight. (C) Plant height. (D) Percentage of roots discoloured. (E) Total stem discoloured. (F) Percentage of leaves wilted or dropped. (G) Reisolations of B. rouxiae-like colonies on half-strength potato dextrose agar from the roots, stems and petioles of uninoculated plants and plants inoculated with the B. rouxiae isolates. Numbers indicate the number of samples assayed per tissue type. Letters indicate a significant separation of means by Tukey's range test at p = 0.05. Error bars indicate a 95% confidence interval.

Figure 6.

Pathogenicity testing of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae isolates on cotton cv. Sicot746 B3F. (A) Plants at harvest (15 — 20 days post inoculation). (B) Total (above and below ground) plant weight. (C) Plant height. (D) Percentage of roots discoloured. (E) Total stem discoloured. (F) Percentage of leaves wilted or dropped. (G) Reisolations of B. rouxiae-like colonies on half-strength potato dextrose agar from the roots, stems and petioles of uninoculated plants and plants inoculated with the B. rouxiae isolates. Numbers indicate the number of samples assayed per tissue type. Letters indicate a significant separation of means by Tukey's range test at p = 0.05. Error bars indicate a 95% confidence interval.

Figure 7.

Symptomatology of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae and Fusarium oxysporum isolates on cotton cv. Sicot746 B3F at harvest. Red vertical bars indicate a scale of 10 cm.

Figure 7.

Symptomatology of Berkeleyomyces rouxiae and Fusarium oxysporum isolates on cotton cv. Sicot746 B3F at harvest. Red vertical bars indicate a scale of 10 cm.

Figure 8.

Pathogenicity testing of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (Fov) isolates on cotton cv. Sicot746 B3F. (A) Plants at harvest (27 — 34 days post inoculation). (B) Total (above and below ground) plant weight. (C) Plant height. (D) Percentage of roots discoloured. (E) Total stem discoloured. (F) Percentage of leaves wilted or dropped. (G) Reisolations of F. oxysporum-like colonies on half-strength potato dextrose agar from the roots, stems and petioles of uninoculated plants and plants inoculated with the Fov isolates. Numbers indicate the number of samples assayed per tissue type. Letters indicate a significant separation of means by Tukey's range test at p = 0.05. Error bars indicate a 95% confidence interval.

Figure 8.

Pathogenicity testing of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (Fov) isolates on cotton cv. Sicot746 B3F. (A) Plants at harvest (27 — 34 days post inoculation). (B) Total (above and below ground) plant weight. (C) Plant height. (D) Percentage of roots discoloured. (E) Total stem discoloured. (F) Percentage of leaves wilted or dropped. (G) Reisolations of F. oxysporum-like colonies on half-strength potato dextrose agar from the roots, stems and petioles of uninoculated plants and plants inoculated with the Fov isolates. Numbers indicate the number of samples assayed per tissue type. Letters indicate a significant separation of means by Tukey's range test at p = 0.05. Error bars indicate a 95% confidence interval.

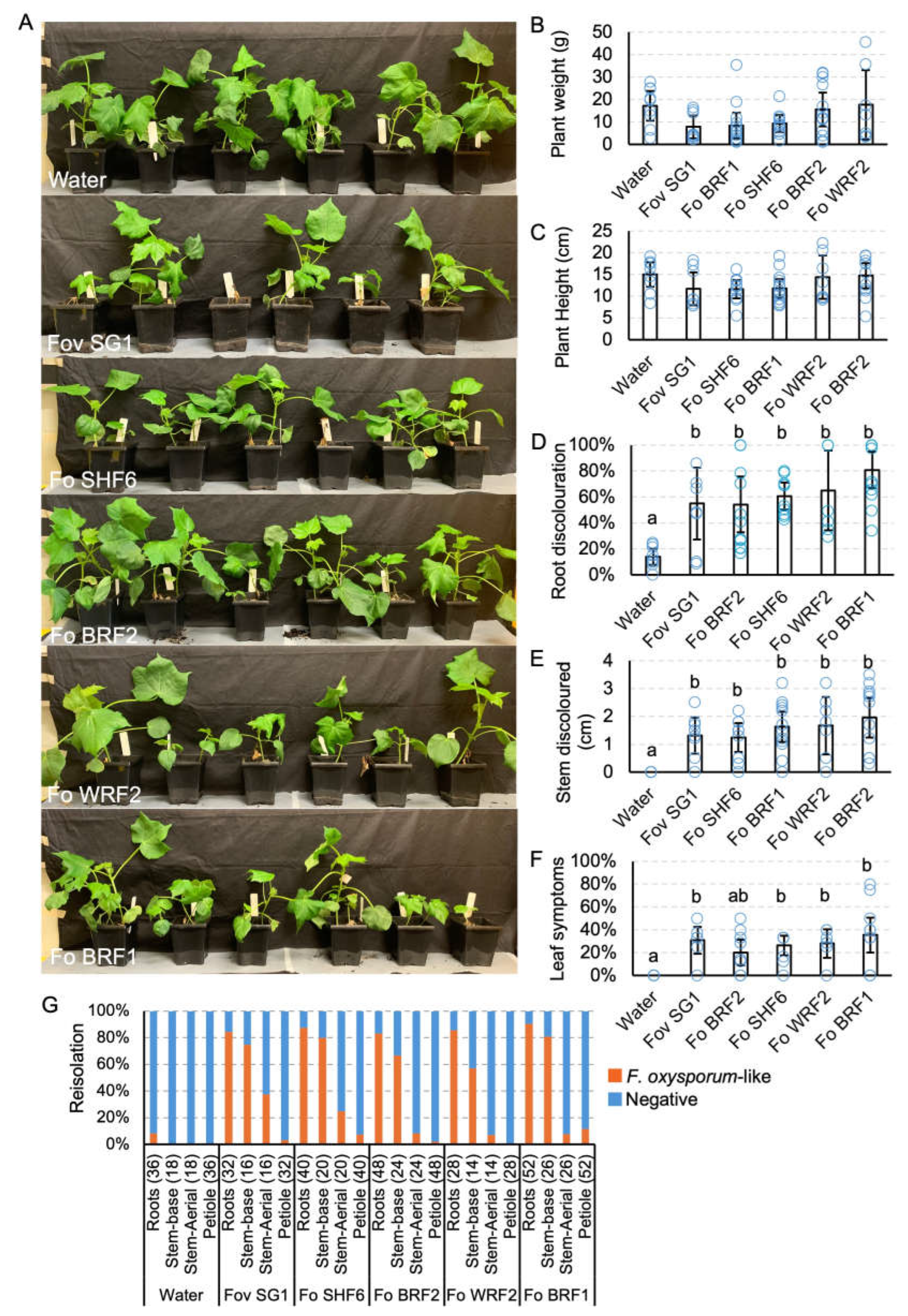

Figure 9.

Pathogenicity testing of Fusarium oxysporum (Fo) isolates on cotton cv. Sicot746 B3F. (A) Plants at harvest (17 — 22 days post inoculation). (B) Total (above and below ground) plant weight. (C) Plant height. (D) Percentage of roots discoloured. (E) Total stem discoloured. (F) Percentage of leaves wilted or dropped. (G) Reisolations of F. oxysporum-like colonies on half-strength potato dextrose agar from the roots, stems and petioles of uninoculated plants and plants inoculated with the Fov isolates. Numbers indicate the number of samples assayed per tissue type. Letters indicate significant a separation of means by Tukey's range test at p = 0.05. Error bars indicate a 95% confidence interval.

Figure 9.

Pathogenicity testing of Fusarium oxysporum (Fo) isolates on cotton cv. Sicot746 B3F. (A) Plants at harvest (17 — 22 days post inoculation). (B) Total (above and below ground) plant weight. (C) Plant height. (D) Percentage of roots discoloured. (E) Total stem discoloured. (F) Percentage of leaves wilted or dropped. (G) Reisolations of F. oxysporum-like colonies on half-strength potato dextrose agar from the roots, stems and petioles of uninoculated plants and plants inoculated with the Fov isolates. Numbers indicate the number of samples assayed per tissue type. Letters indicate significant a separation of means by Tukey's range test at p = 0.05. Error bars indicate a 95% confidence interval.

Table 1.

Fungal isolates used in this study indicating their origins and date of collection.

Table 1.

Fungal isolates used in this study indicating their origins and date of collection.

| Isolates1 |

Species name |

Location |

Cotton tissue sampled2

|

Collection date (d/m/y) |

|

Fov SG1 |

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum

|

Saint George, Queensland |

Stem |

20/04/2022 |

|

Fov SG26 |

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum

|

Saint George, Queensland |

Stem |

20/04/2022 |

|

Fov SG55 |

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum

|

Saint George, Queensland |

Stem |

21/04/2022 |

|

Fov TH1 |

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum

|

Theodore, Queensland |

Stem |

31/12/2022 |

|

Fo BRF1 |

Fusarium oxysporum |

Walgett, New South Wales |

Hypocotyls |

21/12/2017 |

|

Fo BRF2 |

Fusarium oxysporum |

Walgett, New South Wales |

Hypocotyls |

21/12/2017 |

|

Fo SHF6 |

Fusarium oxysporum |

Wee Waa, New South Wales |

Hypocotyls |

21/12/2017 |

|

Fo WRF2 |

Fusarium oxysporum |

Mungindi, New South Wales |

Hypocotyls |

21/12/2017 |

| RVB4.1 |

Berkeleyomyces rouxiae |

Hillston, New South Wales |

Roots |

06/12/2017 |

| StrB22 |

Berkeleyomyces rouxiae |

Mungindi, New South Wales |

Roots |

06/12/2017 |

| BRR4 (DAR85827) |

Berkeleyomyces rouxiae |

Condobolin, New South Wales |

Roots |

06/12/2017 |

| 22BRR77 |

Berkeleyomyces rouxiae |

Wee Waa, New South Wales |

Crown |

02/06/2022 |

Table 2.

SIX gene profiles of the isolates used in this study.

Table 2.

SIX gene profiles of the isolates used in this study.

| Isolate |

SIX1 |

SIX2 |

SIX3 |

SIX4 |

SIX5 |

SIX6 |

SIX6(Fov) |

SIX7 |

SIX8 |

SIX9-1 |

SIX10 |

SIX11 |

SIX12 |

SIX13 |

SIX14 |

|

Fov SG11

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

+ |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

|

Fov SG261

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

+ |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

|

Fov SG551

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

+ |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

|

Fov TH11

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

+ |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

|

Fo BRF11

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Fo BRF21

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Fo SHF61

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Fo WRF21

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| NRRL254332

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

n/t |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

| BRIP636072

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

n/t |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

| BRIP433512

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

n/t |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

| BRIP253742

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

n/t |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

| BRIP433442

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

n/t |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

| BRIP433362

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

n/t |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

| BRIP433392

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

n/t |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

| BRIP433562

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

n/t |

— |

— |

— |

— |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |