Submitted:

11 September 2024

Posted:

13 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

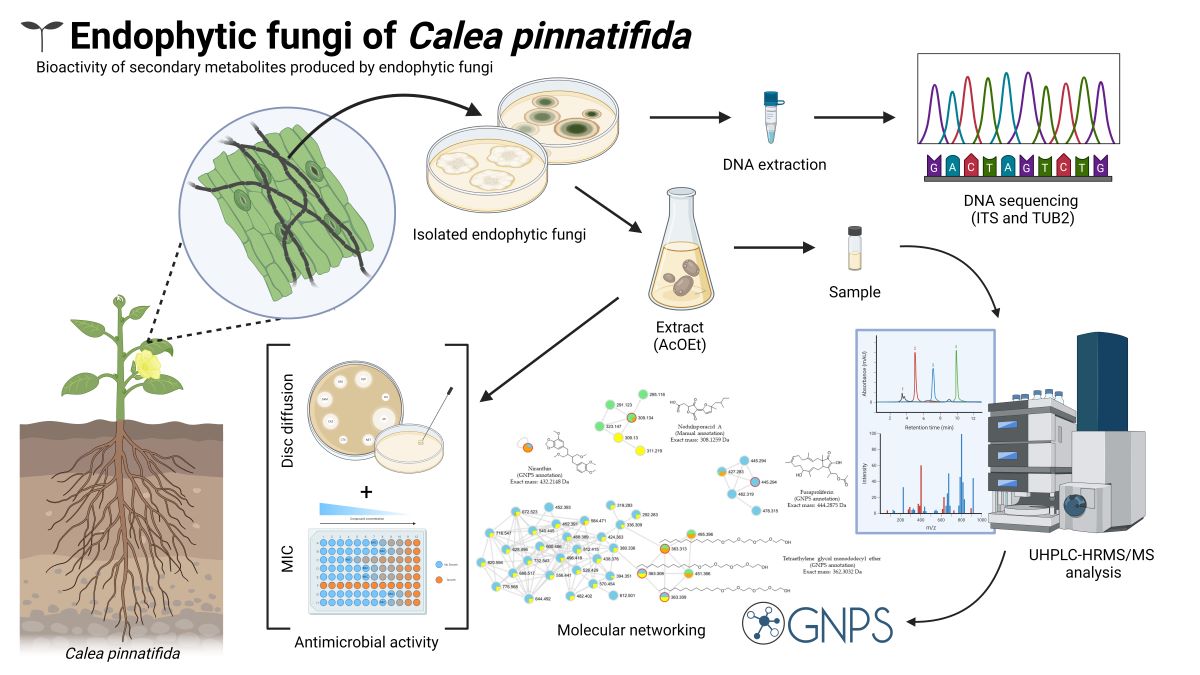

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Experimental Procedures

2.2. Plant Material, Isolation, and Cultivation of Endophytic Fungi

2.3. Identification of Endophytic Fungi

2.4. Data Acquisition by UHPLC-HRMS/MS and Molecular Networking

2.5. Chromatographic Fractionation and ISOLATION of compounds

2.6. Antimicrobial Activity Assay - Strains and Growth of Microorganisms in Solid Culture

2.7. Disc Diffusion Method

2.8. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

3. Results

3.1. Endophytic Fungi Obtained from Leaves

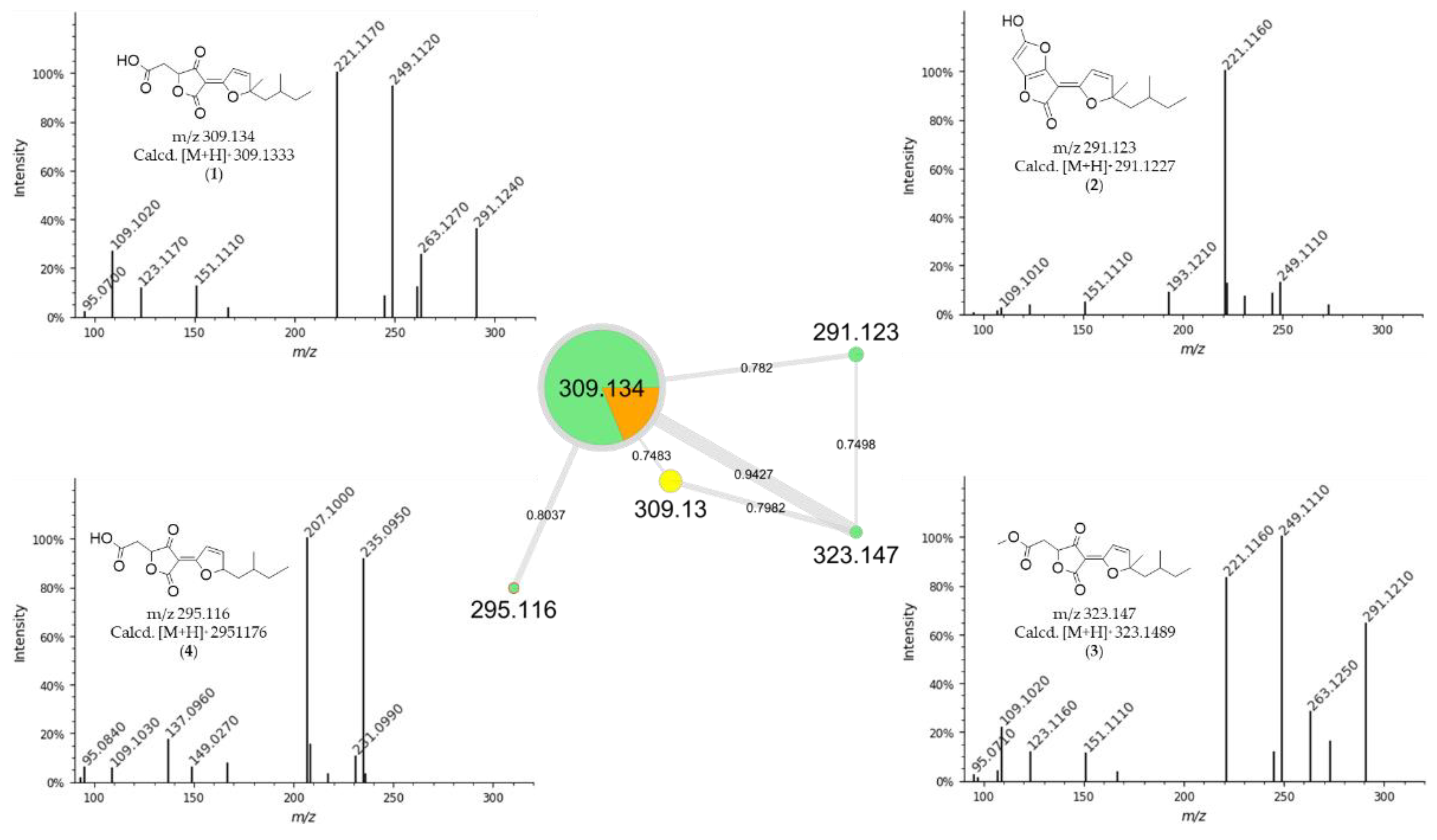

3.2. Dereplication Based on Molecular Networking Organization from HRMS-MS Data

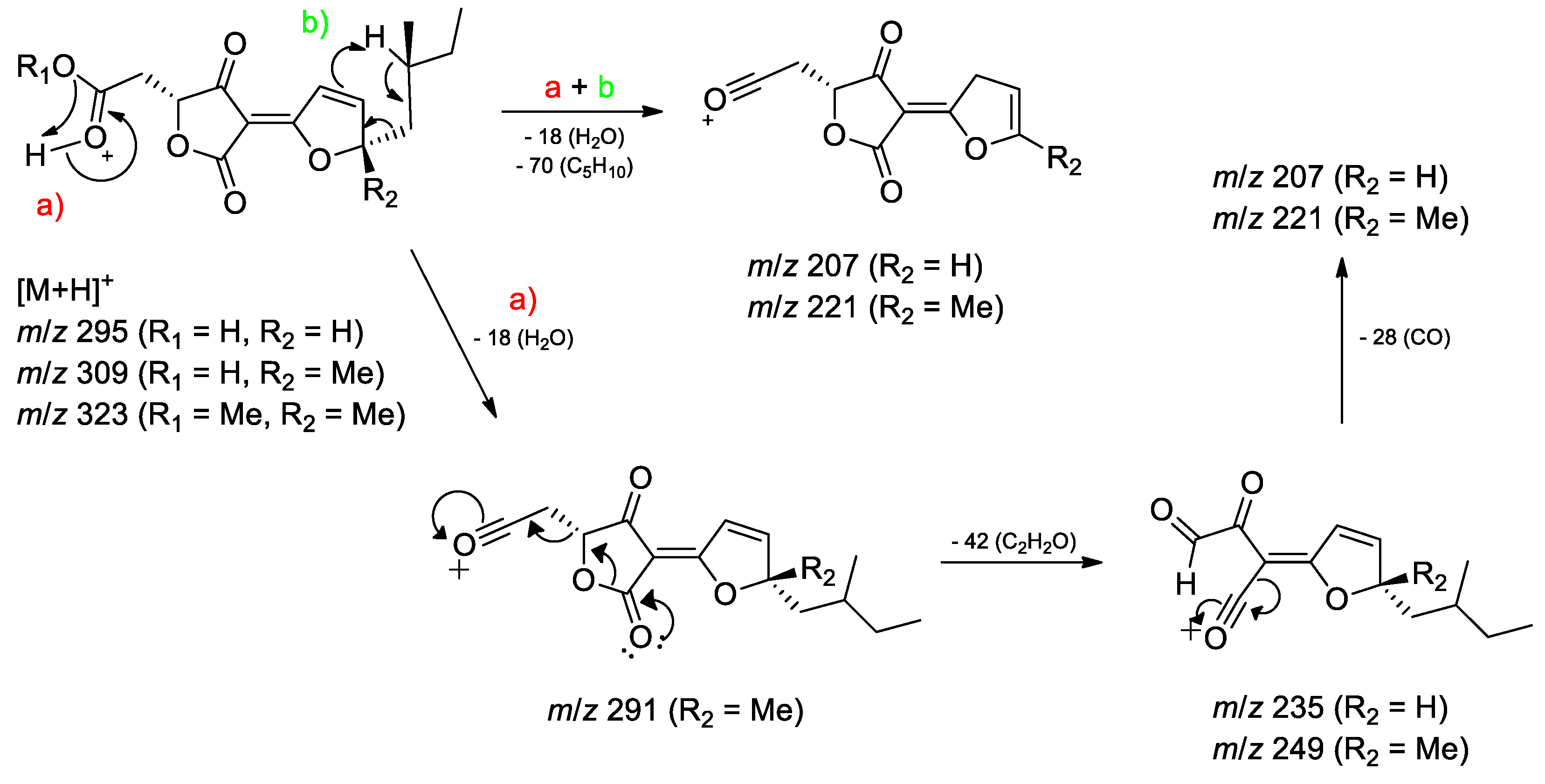

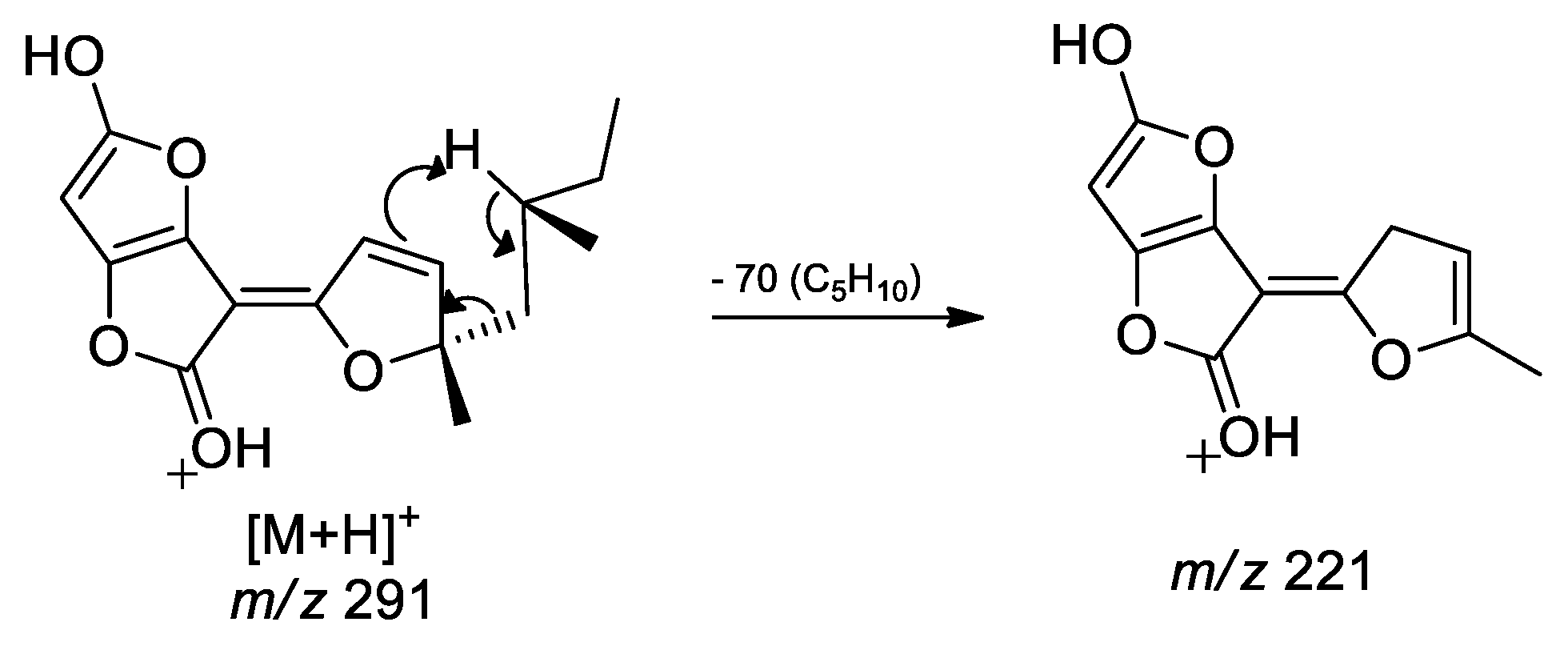

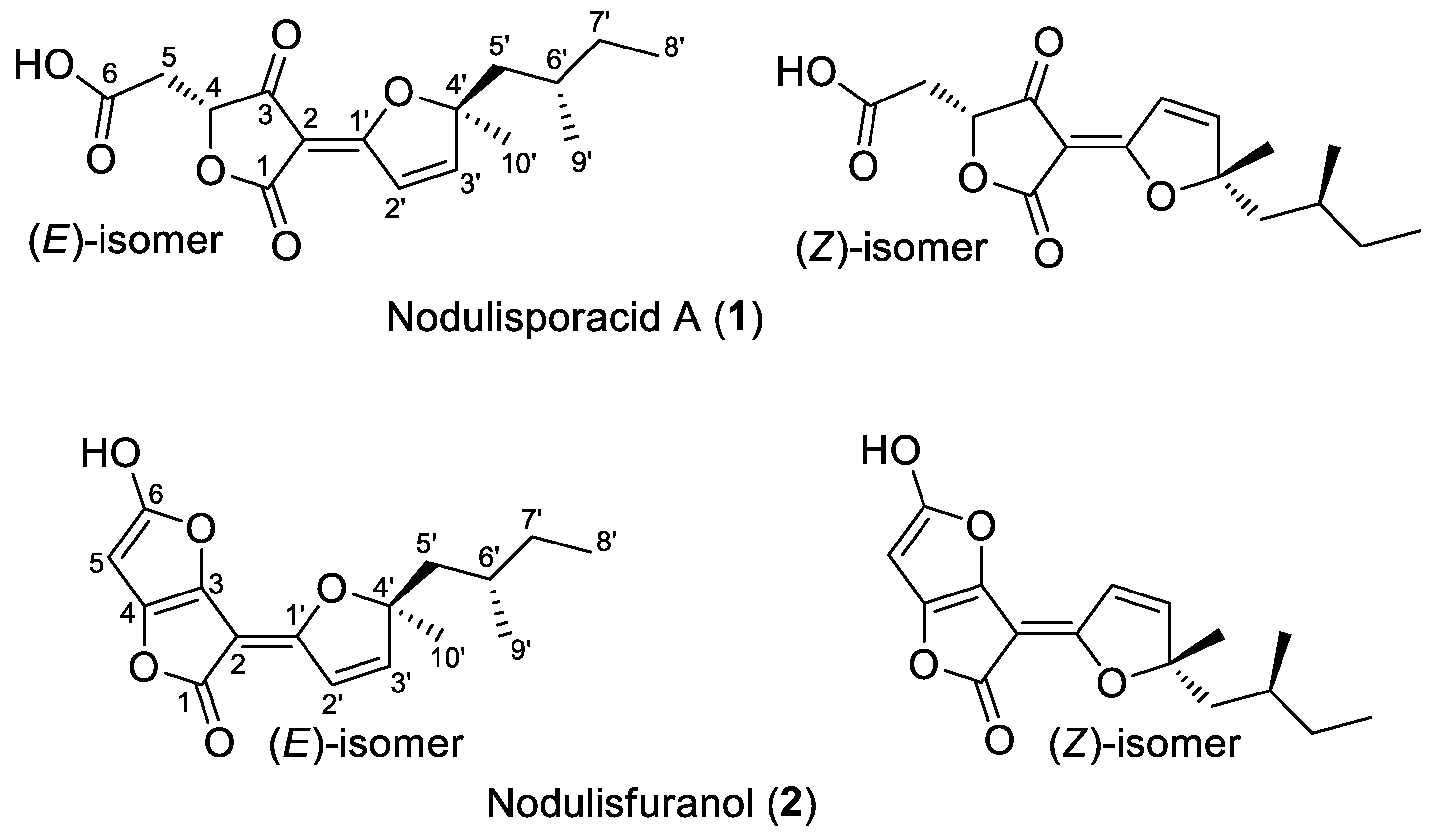

3.3. Identification of Compounds from Fungi Hypomontagnella barbarensis

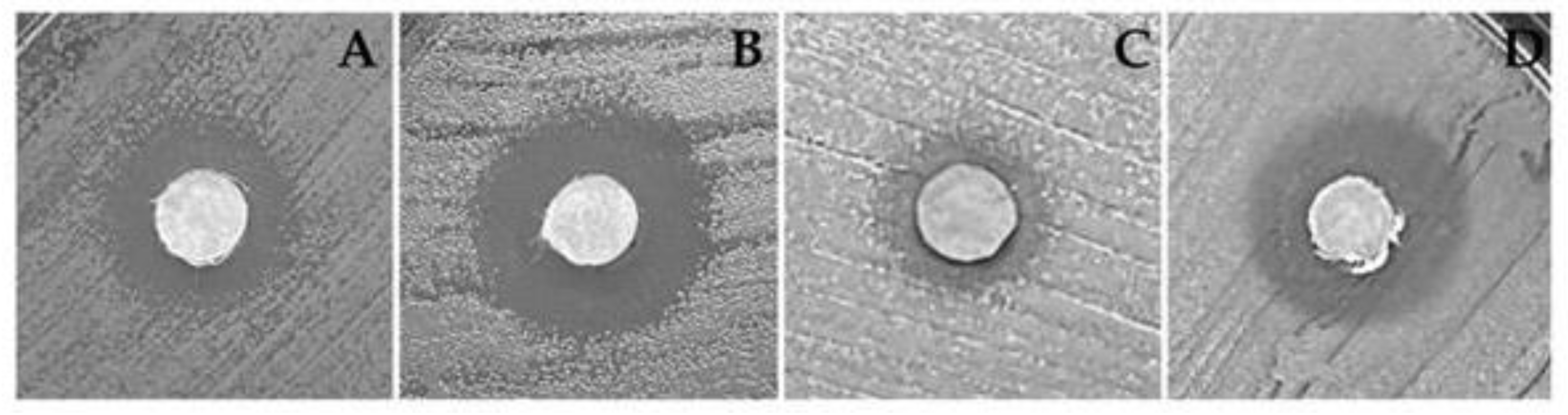

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkatheri AH, Yap PSX, Abushelaibi A, et al (2023) Microbial Genomics: Innovative Targets and Mechanisms. Antibiotics 12:. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (2024) Ten threats to global health in 2019. In: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- Murray CJ, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, et al (2022) Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 399:629–655. [CrossRef]

- Lewis K (2013) Platforms for antibiotic discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12:371–387. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (2024) Antimicrobial resistance. In: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance.

- Loureiro RJ, Roque F, Teixeira Rodrigues A, et al (2016) Use of antibiotics and bacterial resistances: Brief notes on its evolution. Revista Portuguesa de Saude Publica 34:77–84. [CrossRef]

- Bessada SMF, Barreira JCM, Oliveira MBPP (2015) Asteraceae species with most prominent bioactivity and their potential applications: A review. Ind Crops Prod 76:604–615. [CrossRef]

- Caldas LA, Rodrigues MT, Batista ANL, et al (2020) Sesquiterpene lactones from Calea pinnatifida: Absolute configuration and structural requirements for antitumor activity. Molecules 25:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Caruso G, Abdelhamid MT, Kalisz A, Sekara A (2020) Linking endophytic fungi to medicinal plants therapeutic activity. A case study on Asteraceae. Agriculture (Switzerland) 10:1–23. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh SK, Gupta MK, Prakash V, Saxena S (2018) Endophytic fungi: A source of potential antifungal compounds. Journal of Fungi 4:. [CrossRef]

- Golinska P, Wypij M, Agarkar G, et al (2015) Endophytic actinobacteria of medicinal plants: Diversity and bioactivity. International Journal of General and Molecular Microbiology 108:267–289. [CrossRef]

- Kharwar RN, Mishra A, Gond SK, et al (2011) Anticancer compounds derived from fungal endophytes: Their importance and future challenges. Nat Prod Rep 28:1208–1228. [CrossRef]

- Mousa WK, Raizada MN (2013) The Diversity of Anti-Microbial Secondary Metabolites Produced by Fungal Endophytes: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Front Microbiol 4:. [CrossRef]

- Aly AH, Edrada-Ebel RA, Indriani ID, et al (2008) Cytotoxic metabolites from the fungal endophyte Alternaria sp. and their subsequent detection in its host plant Polygonum senegalense. J Nat Prod 71:972–980. [CrossRef]

- Dai J, Krohn K, Draeger S, Schulz B (2009) New naphthalene-chroman coupling products from the endophytic fungus, Nodulisporium sp. From erica arboreal. European J Org Chem 1564–1569. [CrossRef]

- WFO Plant list (2024) Familia Asteraceae. In: https://wfoplantlist.org/taxon/wfo-7000000146-2023-12?page=1.

- Lösgen S, Magull J, Schulz B, et al (2008) Isofusidienols: Novel chromone-3-oxepines produced by the endophytic fungus Chalara sp. European J Org Chem 698–703. [CrossRef]

- Hussain H, Tchimene MK, Ahmed I, et al (2011) Antimicrobial chemical constituents from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. from Notobasis syriaca. Nat Prod Commun 6:1905–1906. [CrossRef]

- Amaral CR do, Mazarotto EJ, Gregório PC, Favretto G (2023) Identification of endophytic fungi in Hamelia patens Jacq. and evaluation of the antimicrobial potential of fungal extracts. Research, Society and Development 12:e23012541767. [CrossRef]

- Hatamzadeh S, Rahnama K, Nasrollahnejad S, et al (2020) Isolation and identification of L-asparaginase-producing endophytic fungi from the Asteraceae family plant species of Iran. PeerJ 8:e8309. [CrossRef]

- Lu H, Zou WX, Meng JC, et al (2000) New bioactive metabolites produced by Colletotrichum sp., an endophytic fungus in Artemisia annua. Plant Science 151:67–73.

- Aron AT, Gentry EC, McPhail KL, et al (2020) Reproducible molecular networking of untargeted mass spectrometry data using GNPS. Nat Protoc 15:1954–1991. [CrossRef]

- Santos AL, Ionta M, Horvath R, et al (2021) Molecular network for accessing polyketide derivatives from Phomopsis sp., an endophytic fungus of Casearia arborea (Salicaceae). Phytochem Lett 42:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Xiao J, Zhang Q, Gao YQ, et al (2014) Secondary metabolites from the endophytic Botryosphaeria dothidea of Melia azedarach and their antifungal, antibacterial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities. J Agric Food Chem 62:3584–3590. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira CM, Regasini LO, Silva GH, et al (2011) Dihydroisocoumarins produced by Xylaria sp. and Penicillium sp., endophytic fungi associated with Piper aduncum and Alibertia macrophylla. Phytochem Lett 4:93–96. [CrossRef]

- Catellani A (1967) A Maintenance and Cultivation of the common pathogenic fungi of man in sterile distilled water. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 70:181–184.

- Neufeld PM, Oliveira PC de (2008) Preservation of dermatophyte fungi by sterile distilled water technique. Revista Brasileira de Análises Clínicas 40:167–169.

- Abreu MMV, Tutunji VL (2008) Implantation and maintenance of microbial culture collection in UniCEUB. Universitas: Ciências da Saúde 2:236–251.

- Aparecido CC, Rosa EC, Costa IAM, Jorge CM (2018) Avaliação de diferentes métodos para preservação de fungos fitopatogênicos. Biológico 80:1–7.

- Pires GCC, Aparecido CC, Finatti D (2012) Divulgação técnica de preservação em laboratório de fungos filamentosos por longos períodos de tempo. Biológico 74:9–16.

- Negri CE, Gonçalves SS, Xafranski H, et al (2014) Cryptic and Rare Aspergillus species in Brazil: Prevalence in clinical samples and in Vitro susceptibility to Triazoles. J Clin Microbiol 52:3633–3640. [CrossRef]

- Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD (2018) MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform 20:1160–1166. [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T (2009) trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25:1972–1973. [CrossRef]

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, et al (2020) IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol Biol Evol 37:1530–1534. [CrossRef]

- Letunic I, Bork P (2021) Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 49:W293–W296. [CrossRef]

- Hoog GS, Guarro J, Gené J (2020) The Ultimate Benchtool for Diagnostics. In: Atlas of Clinical Fungi:, 4th ed. Foundation Atlas of Clinical Fungi, p 776.

- Gonçalves SS, Cano JF, Stchigel AM, et al (2012) Molecular phylogeny and phenotypic variability of clinical and environmental strains of Aspergillus flavus. Fungal Biol 116:1146–1155. [CrossRef]

- Silva WC, Gonçalves SS, Santos DWCL, et al (2017) Species diversity, antifungal susceptibility and phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Exophiala spp. infecting patients in different medical centers in Brazil. Mycoses 60:328–337. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Carver JJ, Phelan V V., et al (2016) Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat Biotechnol 34:828–837. [CrossRef]

- Frank AM, Bandeira N, Shen Z, et al (2008) Clustering millions of tandem mass spectra. J Proteome Res 7:113–122. [CrossRef]

- Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al (2003) Cytoscape: A software Environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13:2498–2504. [CrossRef]

- 2003; 42. Costa SF, Gales A, Machado AM de O (2003) Padronização dos testes de sensibilidade a antimicrobianos por disco-difusão.

- Santos NO, Mariane B, Lago JHG, et al (2015) Assessing the chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from Brazilian plants - Eremanthus erythropappus (Asteraceae), Plectrantuns barbatus, and P. amboinicus (Lamiaceae). Molecules 20:8440–8452. [CrossRef]

- Lambert C, Wendt L, Hladki AI, et al (2019) Hypomontagnella (Hypoxylaceae): a new genus segregated from Hypoxylon by a polyphasic taxonomic approach. Mycol Prog 18:187–201. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Chen Z, Huang M, et al (2023) Cytotoxic tetronic acid derivatives from the mangrove endophytic fungus Hypomontagnella monticulosa YX702. Fitoterapia 170:. [CrossRef]

- Sumiya T, Ishigami K, Watanabe H (2010) Determination of the absolute configuration of nodulisporacid A by the concise synthesis of four stereoisomers via three-component reaction and one-pot construction of the framework. Tetrahedron Lett 51:2765–2767. [CrossRef]

- Vieira MLA, Johann S, Hughes FM, et al (2014) The diversity and antimicrobial activity of endophytic fungi associated with medicinal 1 plant Baccharis trimera (Asteraceae) from the Brazilian savannah 2 3. Canadian Jornal of Microbiology 60:847–856.

- Nicoletti R, Fiorentino A (2015) Plant bioactive metabolites and drugs produced by endophytic fungi of Spermatophyta. Agriculture (Switzerland) 5:918–970.

- Pamphile JA, Costa AT, Rosseto P, et al (2017) Biotchnological applications of secondary metabolites extracted from endophytic fungi: The case of Colletotrichum sp. Revista UNINGÁ 53:113–119.

- García-Pajón CM, Collado IG (2003) Secondary metabolites isolated from Colletotrichum species. Nat Prod Rep 20:426–431. [CrossRef]

- Wang KL, Wu ZH, Wang Y, et al (2017) Mini-review: Antifouling natural products from marine microorganisms and their synthetic analogs. Mar Drugs 15:266. [CrossRef]

- Yang XL, Zhang JZ, Luo DQ (2012) The taxonomy, biology and chemistry of the fungal Pestalotiopsis genus. Nat Prod Rep 29:622–641. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Dong Z, Wen J, et al (2016) A New Sesquiterpene from the Endophytic Fungus Nigrospora sphaerica #003. Natural Product 10:307–310.

- Fukushima T, Tanaka M, Gohbara M, Fuworzl T (1998) Phytotoxicity of three lactones sacchari from Nigrospora. Phytochemistry 48:625–630.

- Meepagala KM, Becnel JJ, Estep AS (2015) Phomalactone as the Active Constituent against Mosquitoes from Nigrospora spherica. Agricultural Sciences 06:1195–1201. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim D, Chai Lee C, Yenn TW, et al (2015) Effect of the extract of endophytic fungus, Nigrospora sphaerica cl-op 30, against the growth of ethicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Mrsa) and Klebsiella pneumonia cells. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 14:2091–2097. [CrossRef]

- Aly AH, Debbab A, Proksch P (2011) Fungal endophytes: Unique plant inhabitants with great promises. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 90:1829–1845. [CrossRef]

- Jalgaonwala RE, Vishwas Mohite B, Mahajan RT (2011) A review: Natural products from plant associated endophytic fungi. J Microbiol Biotechnol 1:21–32.

- Strobel G, Daisy B (2003) Bioprospecting for Microbial Endophytes and Their Natural Products. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 67:491–502. [CrossRef]

- Ćeranić A, Svoboda T, Berthiller F, et al (2021) Identification and functional characterization of the gene cluster responsible for fusaproliferin biosynthesis in fusarium proliferatum. Toxins (Basel) 13:. [CrossRef]

- 2012; 61. Canuto KM, Rodrigues THS, Oliveira FSA, Gonçalves FJT (2012) Fungos endofíticos.

- Sumiya T, Ishigami K, Watanabe H (2010) Determination of the absolute configuration of nodulisporacid A by the concise synthesis of four stereoisomers via three-component reaction and one-pot construction of the framework. Tetrahedron Lett 51:2765–2767. [CrossRef]

- Kasettrathat C, Ngamrojanavanich N, Wiyakrutta S, et al (2008) Cytotoxic and antiplasmodial substances from marine-derived fungi, Nodulisporium sp. and CRI247-01. Phytochemistry 69:2621–2626. [CrossRef]

- 1996; 64. Logrieco A, Moretti A, Fornelli F, et al (1996) Fusaproliferin Production by Fusarium subglutinans and Its Toxicity to Artemia salina, SF-9 Insect Cells, and IARC/LCL 171 Human B Lymphocytes.

- Pereira RG, Garcia VL, Nova Rodrigues MV, Martínez J (2016) Extraction of lignans from Phyllanthus amarus Schum. & Thonn using pressurized liquids and low-pressure methods. Sep Purif Technol 158:204–211. [CrossRef]

- Hemmerling F, Piel J (2022) Strategies to access biosynthetic novelty in bacterial genomes for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 21:359–378.

| Species | Cell line |

|---|---|

| Cryptococcus neoformans | KN99α (serotype A) |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | JEC21 (serotype D) |

| Cryptococcus gattii | NIH312 (serotype C) |

| Cryptococcus gattii | R265 (serotype B) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | BY4647 |

| Candida krusei | Clinical isolate 9602 |

| Candida parapsilosis | Clinical isolate 68 |

| Candida albicans | CBmay 560 |

| Candida tropicalis | ATCC 1303 |

| Candida dubliniensis | ATCC 7876 |

| Species | Cell line |

|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecium | ATCC CCB076 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 27853 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 700603 |

| Escherichia coli | ATCC 25922 |

| Shigella flexneri | ATCC 12022 |

| Salmonella enterica | ATCC 14028 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC25923 |

| Acinetobacter baumanii | ATCC 19606 |

| Strain Number | Species | % Identity* | |||

| ITS | Cod. | TUB2 | Cod. | ||

| CPFF12 | Colletotrichum karstii | 100 | PP831945 | 100 | PP840075 |

| CPFF14 | Colletotrichum karstii | 99.39 | PP829193 | 99.72 | PP840076 |

| CPFF16 | Colletotrichum siamense | 100 | PP829196 | 99.60 | PP840077 |

| CPFF41 | Hypomontagnella barbarensis | 99.23 | PP829195 | 93.24 | PP840078 |

| CPFF42 | Neopestalotiopsis clavispora | 100 | PP829194 | 99.09 | PP942538 |

| CPFF52 | Nigrospora sacchari-officinarum | 99.08 | PP832015 | 100.00 | PP840079 |

| CPFC2 | Annulohypoxylon moriforme | 98.50 | PP834406 | 98.09 | PP840080 |

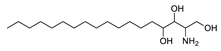

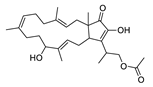

| Compound name |

Molecular formula |

Calculated mass |

Precursor | Error (ppm) | Sample | Structural formula |

|

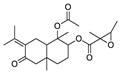

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-Acetoxy-7-isopropylidene-1,4a-dimethyl-6-oxodecahydro-2-naphthalenyl 2,3-dimethyl-2-oxiranecarboxylate | C22H32O6 | 415.2097 [M+Na]+ |

415.2097 | 0.1 | CPFF12 CPFF16 |

|

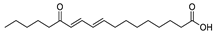

| 2 | 13-keto-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid | C18H30O3 | 295.2273 [M+H]+ |

295.2275 | 0.7 | CPFF41 CPFF42 |

|

| 3 | Alismol | C15H24O | 203.1799 [M+H]+ |

203.1797 | 1.0 | CPFF14 CPFF52 |

|

| 4 | Phytosphingosine | C18H39NO3 | 318.3008 [M+H]+ |

318.3000 | 2.6 | CPFF12 CPFF16 CPFF52 |

|

| 5 | Fusaproliferin | C27H40O5 | 445.2954 [M+H]+ |

445.2949 | 1,1 | CPFF12 CPFF14 |

|

|

Extract (400 μg) |

Species (lineage) | ||

|

S. cerevisiae (BY4647) |

C. albicans (CBmay 560) |

S. aureus (ATCC 25923) |

|

| CPFF12 | 1.4 ± 0.26 | 1.23 ± 0.25 | n/a |

| CPFF14 | n/a | n/a | 0.73 ± 0.23 |

| CPFF41 | n/a | n/a | 1.37 ± 0.32 |

| Control* | 2.07 ± 0.12a | 2.07 ± 0.12b | 2.5 ± 0.0b |

| Specie | Extract - MIC90 (mg/mL) | Control* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPFF12 | CPFF14 | CPFF41 | ||

| S. aureus (ATCC25923) | n/a | 0.20 (91.6±1.5) | 0.05 (92.0±1.0) | 0.004a |

| C. albicans (CBmay 560) | 0.01 (92.0±1.9) | n/a | n/a | 0.025b |

| S. cerevisiae (BY4647) | 0.02 (90.3±1.5) | n/a | n/a | 0.013c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).