1. Introduction

Non-communicable diseases are the leading cause of global deaths, including cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes [

1]. Poor countries face higher mortality from communicable diseases like HIV and malaria [

2,

3], with African countries accounting for 95% of malaria cases, primarily affecting children under 5 years old [

3]. The increasing global incidence and mortality of diseases such as cancers [

4], coupled with drug resistance [

3,

5], necessitates the search for new treatments to fight these diseases, some of which still remain incurable.

Research continues to explore biodiversity, particularly in the marine environment, to discover new natural products which are well-known sources of biologically active compounds [

6,

7]. Within this biological diversity, actinobacteria represent one of the most important microbial class for the discovery of new bioactive molecules [

8,

9,

10]. Actinobacteria can be found in diverse sources such as sediments or holobionts [

8]. Some of these microorganisms are exclusively isolated from marine habitats [

11] highlighting their adaptability to various environments. They are able to produce a wide variety of specialized metabolites, traditionally referred to as “secondary metabolites, and are considered as the major source of naturally occurring antibiotics [

12,

13]. They also produce molecules with various activities such as anticancer, antiviral or antifungal [

12,

13,

14]. The obligate marine genus

Salinispora produces a multitude of bioactive compounds [

10,

15], among them staurosporine and its analogues demonstrated various antitumor activities [

16,

17].

Despite the large number of bioactive microbial metabolites currently isolated, advances in microbial genomics demonstrated a significant difference between the number of specialized metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) and the number of metabolites chemically isolated by researchers [

18]. For example, the

Aspergillus. nidulans fungi has an estimated production capacity of over 40 metabolites, of which only 50% have been identified [

19,

20]. This difference comes from silent or cryptic BGCs, not always expressed under laboratory culture conditions. This is probably due to the lack of stimuli that are difficult to identify and reproduce, in comparison with the original environment [

18,

21]. The investigation of microbial specialized metabolites is therefore limited. In order to explore the maximum potential of microorganisms, researchers have developed various techniques based on molecular or cultural approaches to express these silent BGCs [

22,

23]. Among these, the OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds) method is one of the most frequently used. It aims at modifying various parameters, which can be physical (type of culture support or time), or chemical (composition of the medium or pH) or which can be the use of chemical or biological elicitors [

22,

23]. These changes induced the production of a higher number of microbial metabolites [

22,

23] and have led to the discovery of new bioactive molecules [

24,

25]. A study on marine derived fungi cultivated under different conditions (different media and culture support) proved their influence on the chemical profile and anticancer activity of microbial extracts [

26].

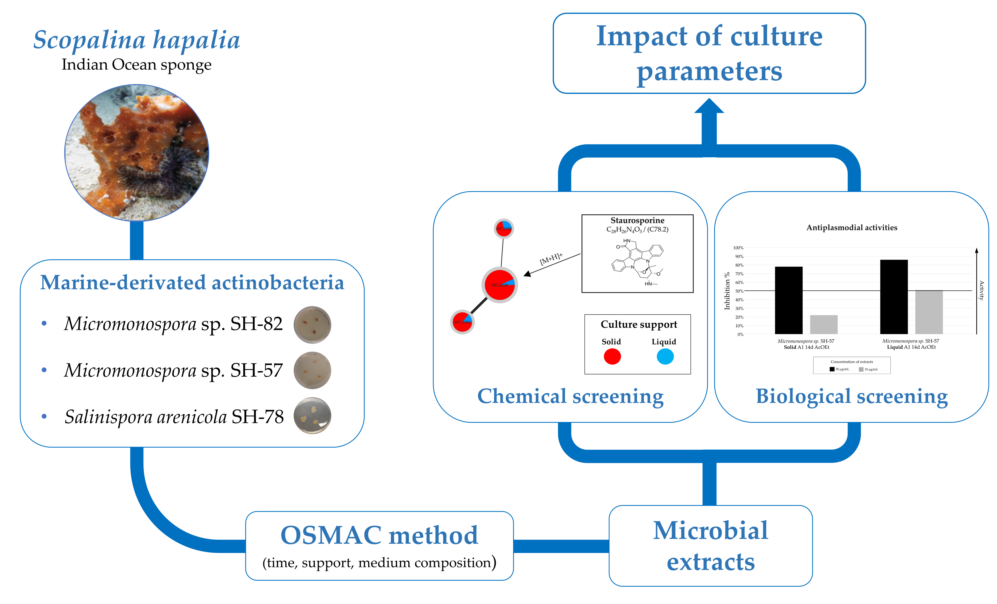

This article presents the impact of culture parameters on the metabolic diversity of microbial extracts and their associated biological activities. Three microbial strains,

Salinispora arenicola (SH-78), and two

Micromonospora sp. (SH-82 and SH-57), isolated from the microbiota of the marine sponge

Scopalina hapalia ML-263 [

27] were studied. The work focused on a microbial group known for its production of specific and bioactive metabolites: actinobacteria [

8,

10,

12]. An OSMAC culture strategy was set up to evaluate the impact of culture parameters such as time, support for growth or culture medium composition on the production of microbial metabolites. The extracts obtained from the cultures were chemically analyzed by LC-HRMS/MS and the data were processed by a workflow allowing the creation of ion identity molecular networks (IIMN) [

28]. Using Cytoscape 3.9.1 software [

29], these networks enabled the influence of culture parameters to be visualized graphically. Bioinformatics tools such as the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform [

30], SIRIUS 5.7.2 software [

31,

32] and the ISDB-DNP tool (In Silico DataBase-Dictionary of Natural Products) [

33] refine with timaR package [

34] were used to annotate the microbial metabolites detected in the extracts. A selection of extracts was tested for their cytotoxic and antiplasmodial activities in order to assess the impact of culture conditions on biological activity and correlate them with chemical diversity. The results of the study indicate that the impact of culture parameters depended on the species studied and varied in relation to the microbial metabolites targeted. In the case of the

Micromonospora sp. SH-57 strain, liquid culture showed greater potential for the discovery of new bioactive molecules. For

Micromonospora sp. SH-82, the A1 medium allowed the detection of a higher number of specialized metabolites, and the longer culture time was also of superior interest.

3. Discussion

Researchers are continuing their efforts to discover novel bioactive molecules in response to numerous public health challenges [

3,

4,

5]. Among the potential sources, microorganisms, particularly actinobacteria, offer a wide range of molecules with unique structures and remarkable biological activities [

8,

9,

10]. However, the search for new molecules of microbial origin can be complex and costly, partly due to certain biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) not being expressed under laboratory conditions [

18,

21] and the predominant compounds already identified are often re-isolated [

23,

38]. To overcome these challenges, scientists have adapted various molecular and cultural approaches to express these “silent” BGCs [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. One of these methods, known as OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds), involves varying different culture parameters, to express the full metabolic potential of microorganisms [

23]. This method has already demonstrated its effectiveness in discovering promising new molecules [

22]. In this study, the impact of culture parameters such as culture duration, support culture, and medium composition on the metabolic diversity and biological activity of extracts from three marine-derived actinobacteria isolated from an Indian Ocean sponge,

Scopalina hapalia (ML-263) was evaluated. By analyzing these factors, the aim is to identify the optimal culture parameters to discover new bioactive molecules with significant therapeutic potential.

Different chemical and biological analyses were conducted to assess the impact of culture parameters on the metabolic diversity and biological activity of the microbial extracts. HPLC-DAD-CAD chemical analyses revealed a significant presence of compounds originating from the culture medium. The initial use of amberlite aimed to increase the proportion of microbial metabolites in the extracts, thereby facilitating the identification of major compounds and future isolation work of metabolites [

39]. Subsequently, HRMS/MS analyses were performed, enabling the construction of an Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) [

28] and the annotation of detected microbial metabolites. These potential identifications were achieved using various bioinformatic tools, including the GNPS platform [

30], the SIRIUS software [

31], and the ISDB tool coupled with timaR [

33,

34], by comparing the spectral data of the extracts to various databases. Annotations were considered relevant when multiple tools converged towards the same identification, corroborated by the literature. The impact of culture parameters on the bioactivity of microbial extracts was evaluated through two activity tests: cytotoxicity on HCT-116 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines (colon and breast cancer models [

36,

40]) and antiplasmodial activity against the

Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 strain. Detecting biological activities in these crude extracts would be even more promising, considering the low proportion of microbial metabolites compared to the compounds originating from the culture medium.

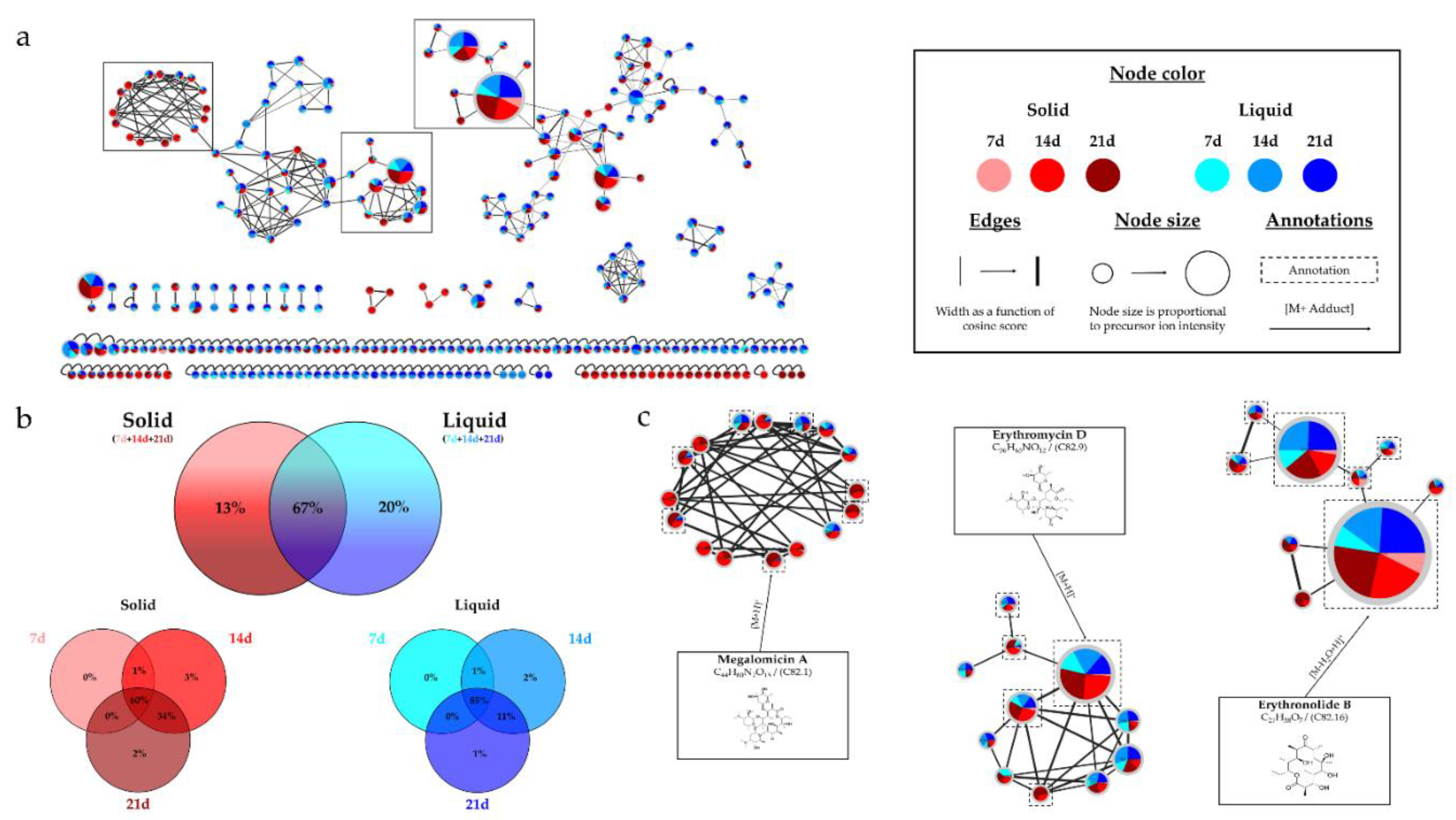

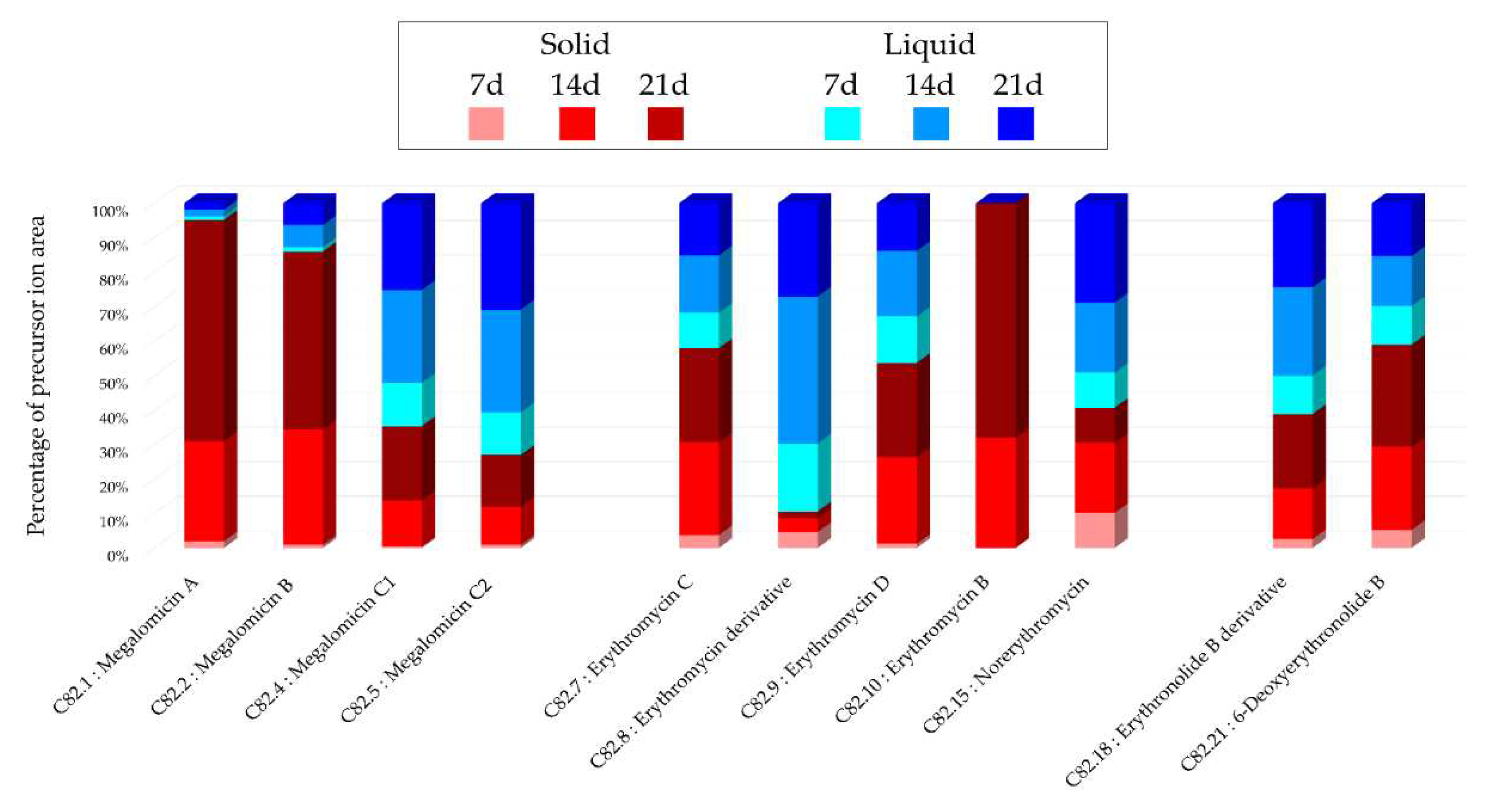

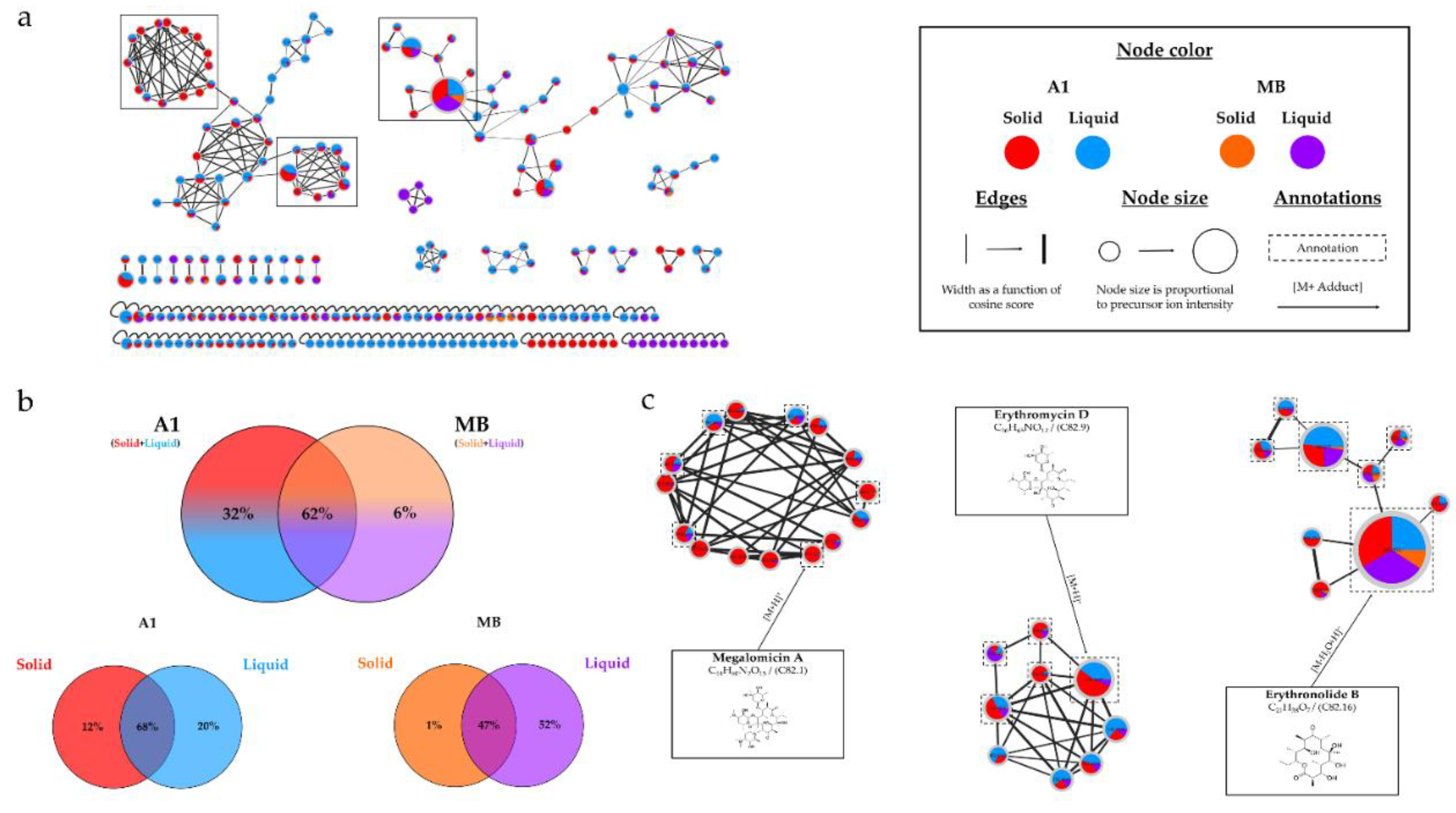

The strain Micromonospora sp. SH-82 was the first to be studied to assess the impact of culture conditions on the production of microbial metabolites. The parameters studied included the incubation time, the culture support, and the composition of the medium. HPLC-CAD analyses showed that the culture time increased the number of compounds, especially those considered major (>30 pA) in the extracts from both culture supports on medium A1. This trend was more pronounced for the extracts from solid culture on medium A1 after 14 days. Regarding the impact of the support, the visible peaks on the chromatogram were relatively close, but table S.2 detailing the observed peaks showed higher values for the solid support, indicating a greater quantity of microbial metabolites. Conversely, the culture in liquid MB medium appeared more favorable for this strain than solid culture.

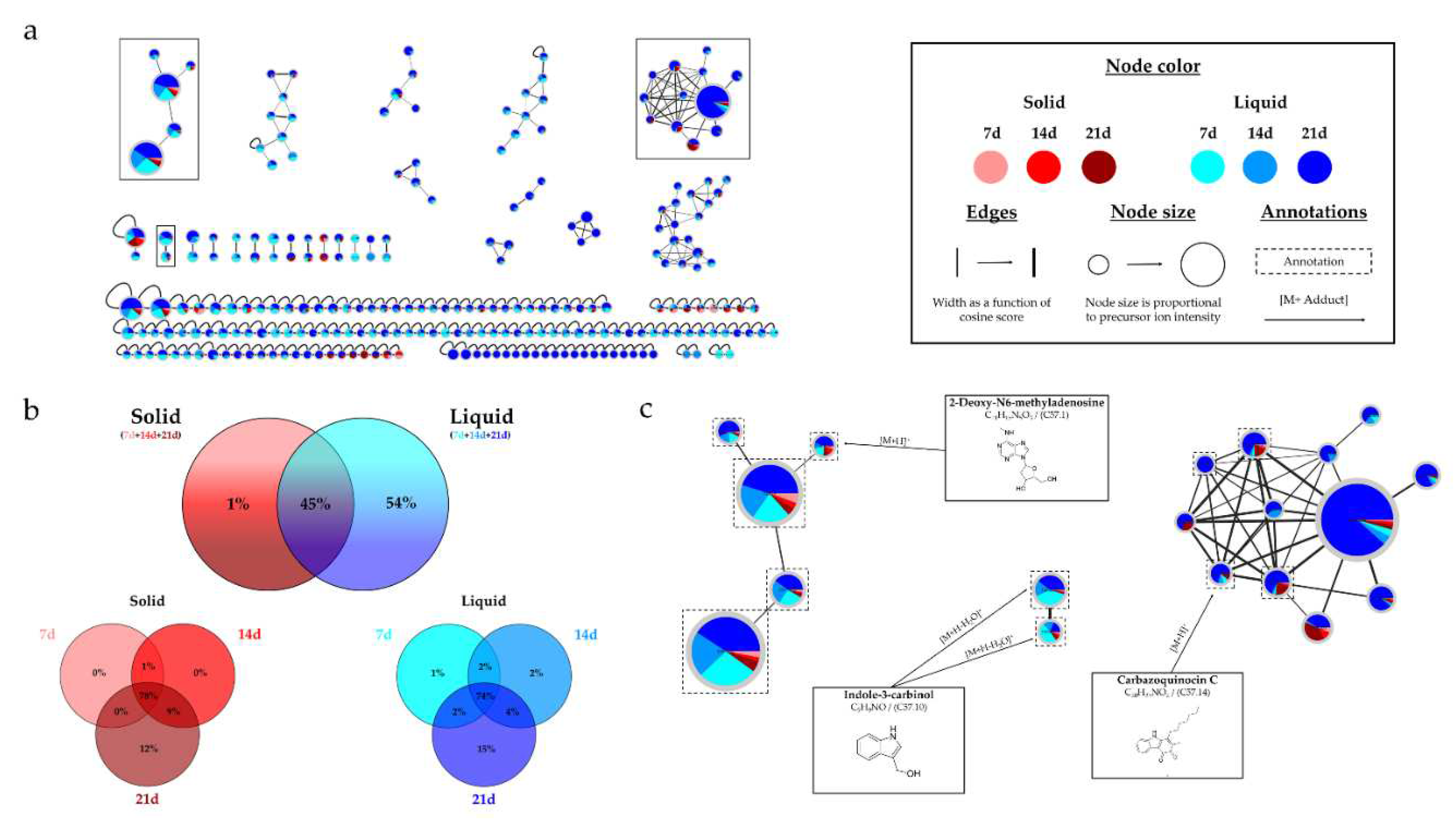

HRMS/MS analyses confirmed the culture time influenced the metabolic diversity, with an increase in the number of nodes, potentially representing microbial metabolites, over time. For extracts from solid A1 cultures, the percentage of nodes exceeded 90% after 14 days, whereas it was only 60% for 7 days. These results demonstrate the importance of extending the culture time for

Micromonospora sp. SH-82. A relatively homogeneous distribution of nodes was observed for extracts from both types of culture supports on medium A1. Each support culture presented unique nodes, representing 13% for the solid support and 20% for the liquid support of the total nodes in the IIMN (

Figure 1.a). Therefore, it is interesting to test both culture supports to cover a maximum of potential metabolites. Regarding the influence of the medium composition, extracts from medium A1 showed the majority of nodes in IIMN (

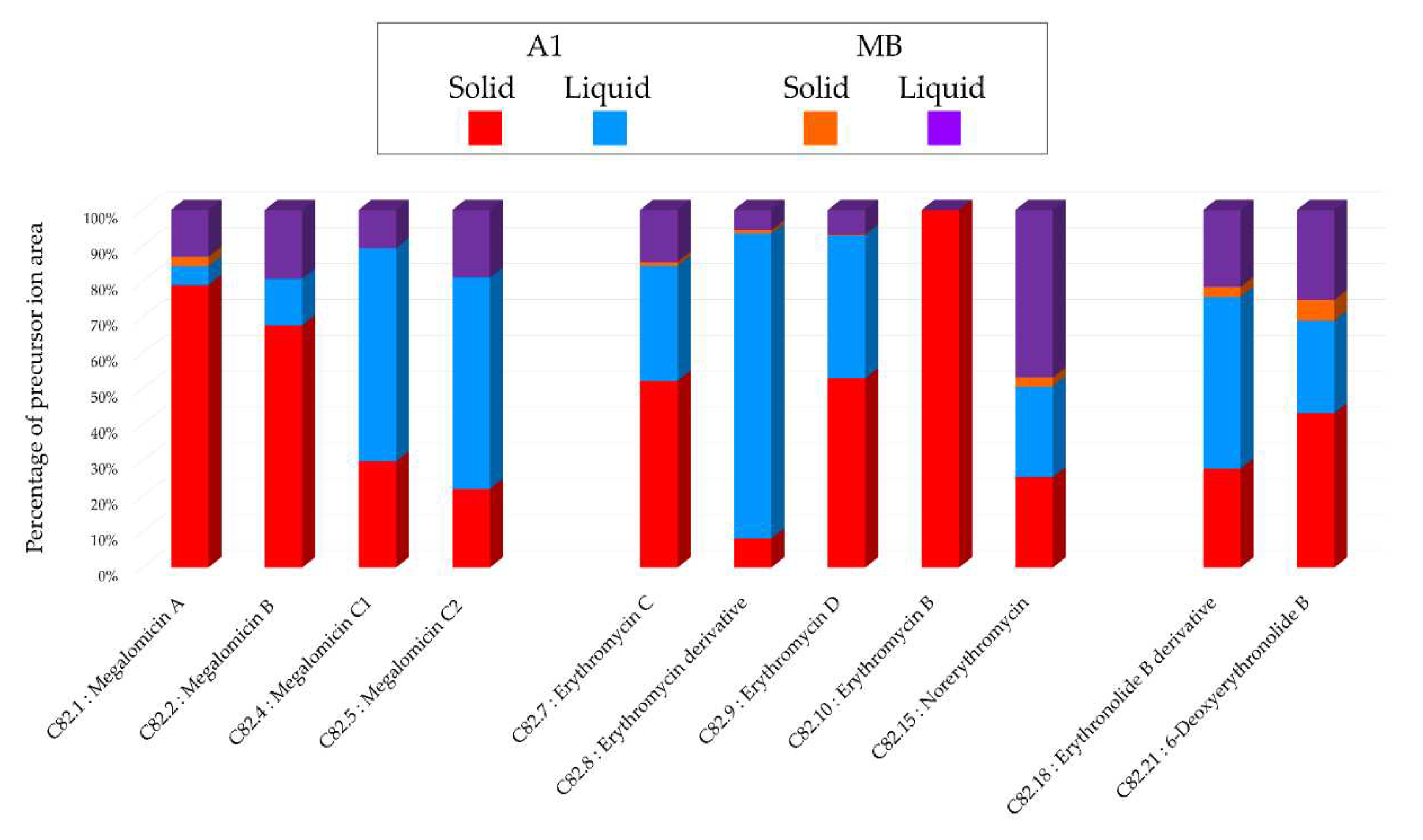

Figure 5), with 32% of unique nodes specific to this medium, suggesting a better chemical diversity for this medium. The annotations obtained for this strain highlighted the presence of three major families of molecules: megalomicins, erythromycins, and erythronolides. Among the 21 annotations made, 7 of them were identified using two distinct bioinformatic tools, leading to the same identification. This concordance reinforces the reliability of these annotations, and among them, 4 correspond to megalomicins. This family of macrolide antibiotics was isolated in 1969 from

Micromonospora megalomicea [

41]. The study conducted by Useglio et al. (2010) on the

in vivo bioconversion of erythromycin C to megalomicin A [

42], and the description of biosynthetic pathways like erythromycin D from the METACYC® database [

43], confirm the annotations presented in

Figure 2. The precursors identified in these previous studies support the annotations made, such as the detection of 6-deoxyerythronolide B. This concordance of information, including consensus annotations, the presence of these molecules in biosynthetic pathways, and the source species, strengthens the identification of these microbial metabolites. The majority of annotations are visible in all extracts (

Table 1) but with different precursor ion areas intensities. The extract derived from the solid A1 culture at 21 days exhibits the majority of maximal intensities, suggesting more favorable conditions for the detection of specialized metabolites. This extract also includes unique annotations and numerous unannotated nodes present in the megalomicin cluster, potentially corresponding to unknown derivatives. However, the cluster presented in

Figure S2 shows ions mainly originating from extracts derived from liquid cultures, highlighting the importance of conducting both types of cultures to increase the diversity of produced metabolites. The chemical analyses revealed the combined impact of culture support and culture duration present on the chemical diversity of therefore microbial extracts.

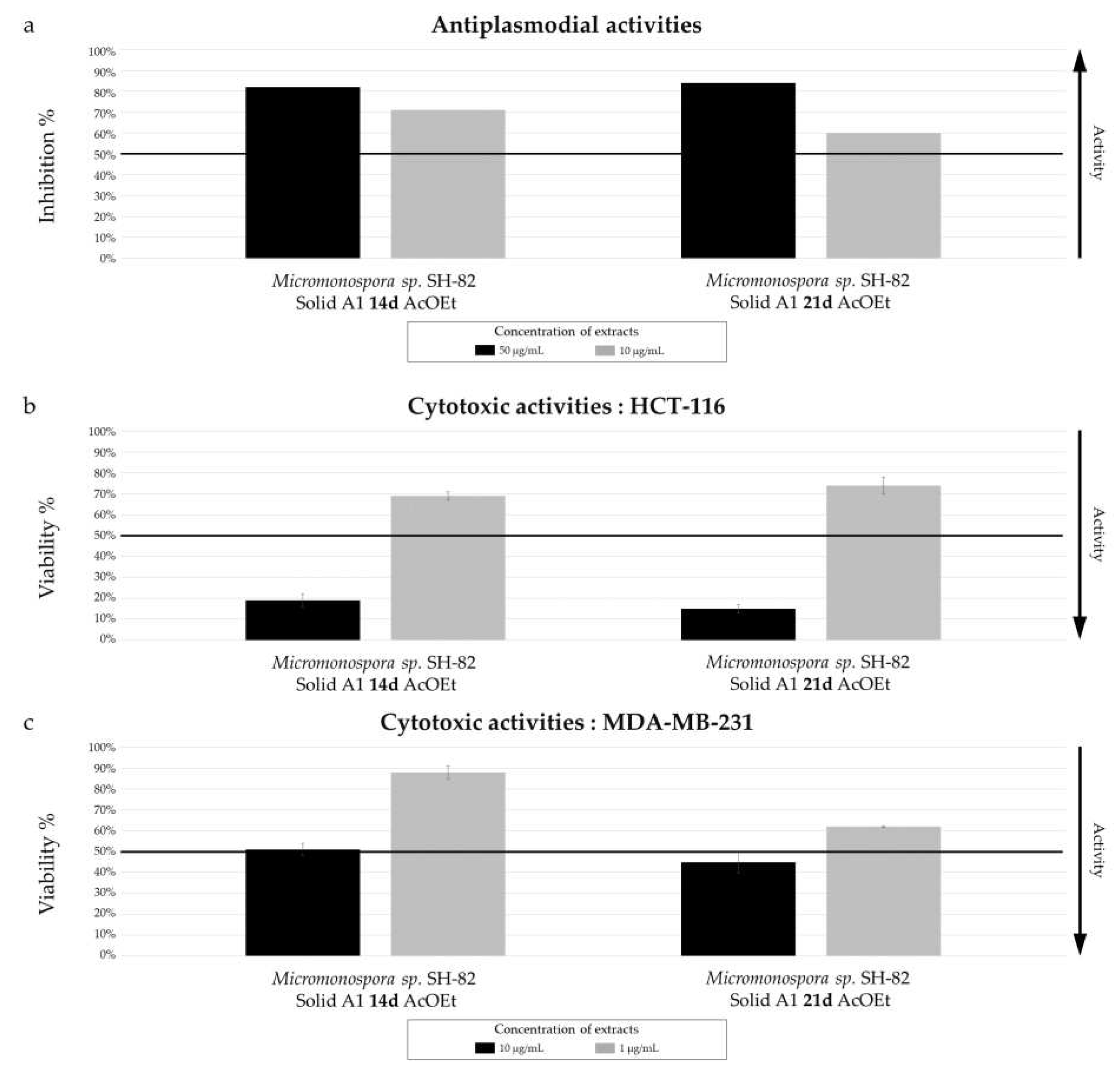

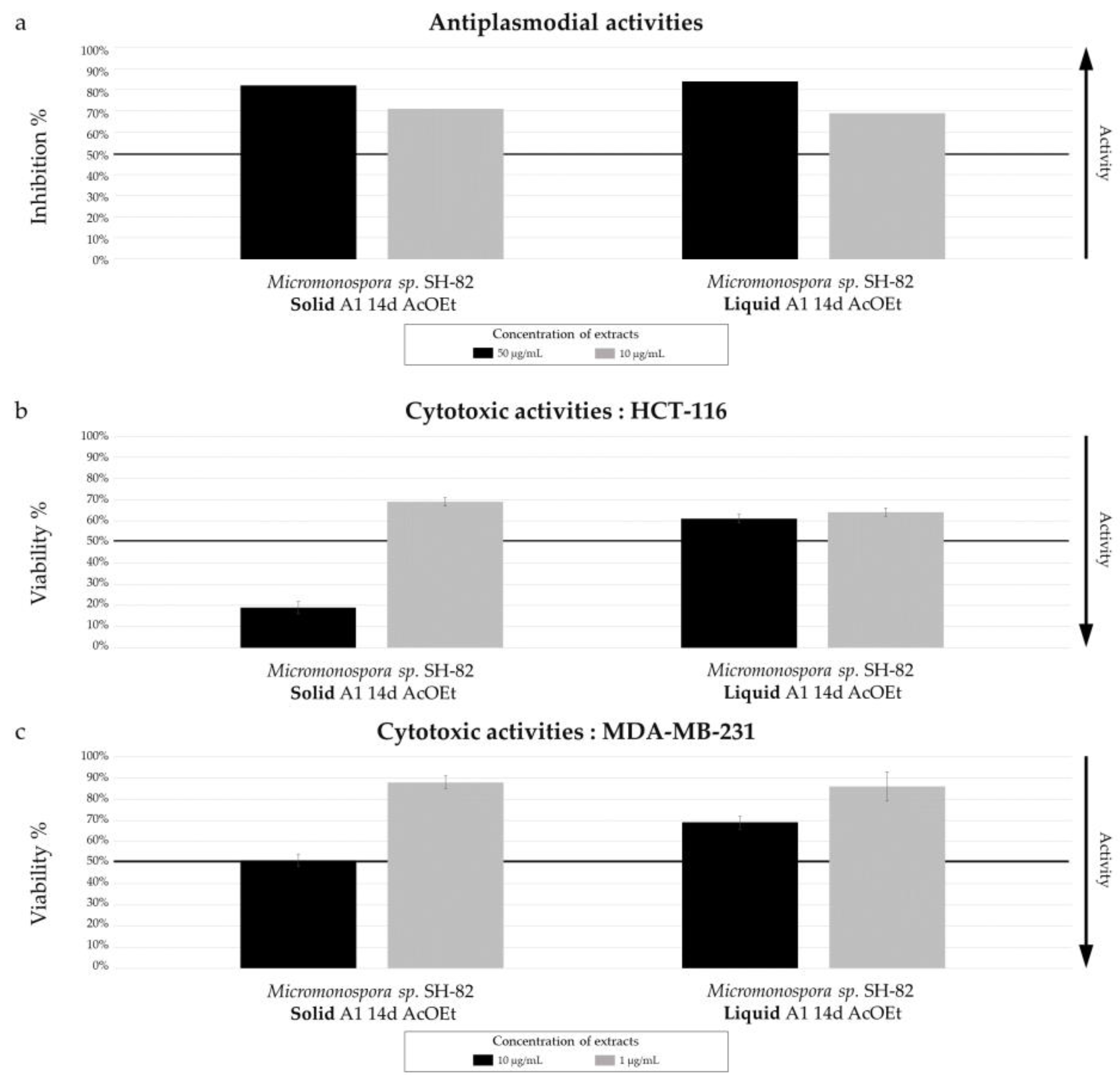

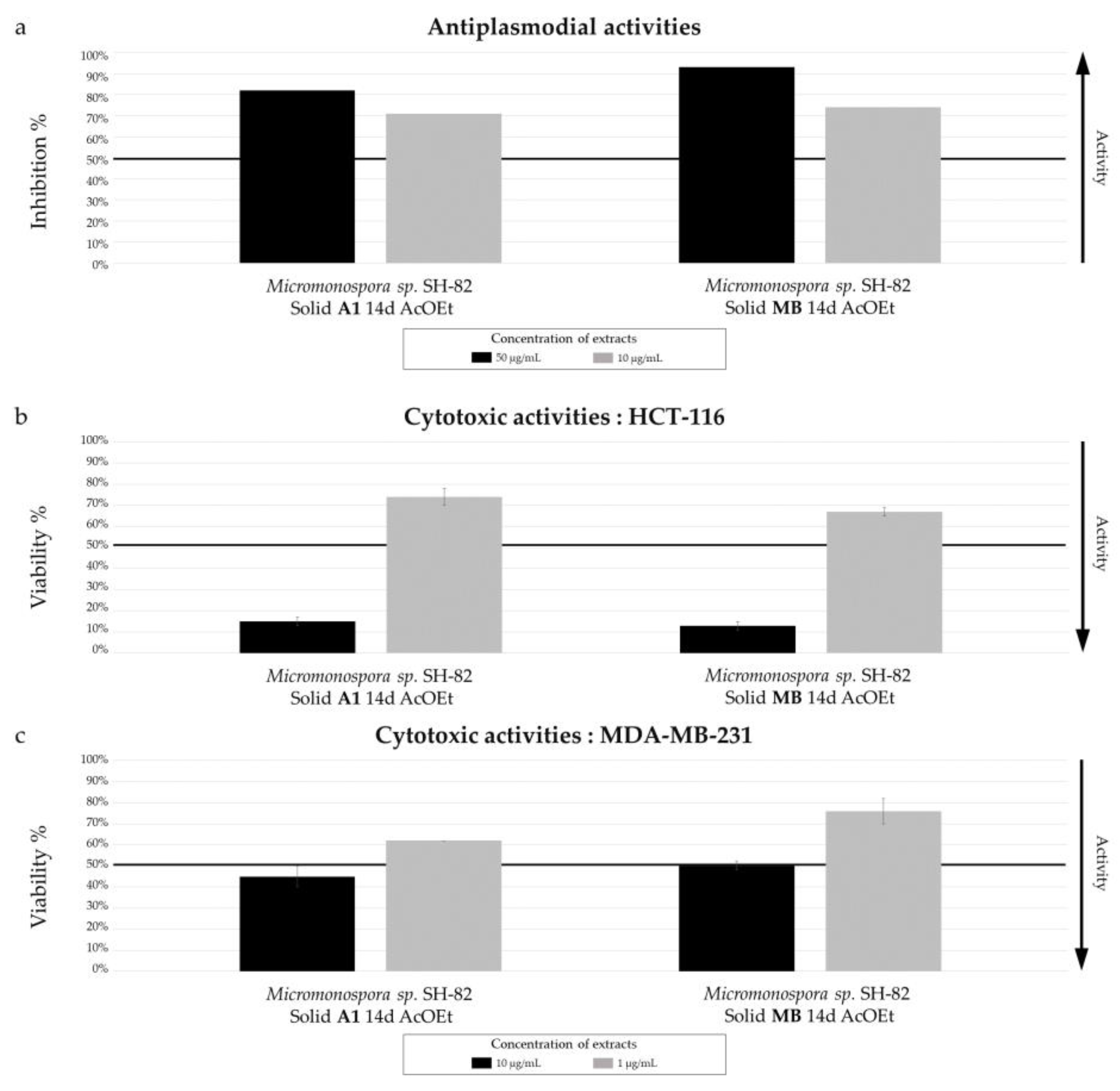

The culture parameters also influenced the bioactivity of the selected microbial extracts, all of which exhibited promising antiplasmodial activity, with variations depending on the parameters. The annotated megalomicins in our samples have previously shown antiplasmodial activity in a study by Goodman et al. (2012) against two strains of

Plasmodium falciparum [

44], which could explain this promising activity. The increase chemical diversity observed in culture time is correlated with an increase biological activity. The IC

50 values of 5.06 ± 0.95 µg/mL and 11.31 ± 1.18 µg/mL were measured for the extracts derived from solide cultures A1 at 14 days and 21 days, respectively. The impact of the culture support on biological activity is less pronounced, which is consistent with the chemical results. Finally, the extract derived from the MB medium culture, with low chemical diversity, exhibits a slightly more interesting IC

50 than the extract from the A1 medium. This discrepancy could be influenced by the proportions of bioactive metabolites, the ionization of molecules, or the influence of components in the culture medium. A previous study conducted by Farinelle et al. (2021) also revealed variability in the biological activities of extracts from fungi cultured in six different media, without necessarily establishing a correlation with the quantity of metabolites [

45]. Regarding cytotoxic activity, the extracts of

Micromonospora sp. SH-82 did not show significant activity. The variations in activity were similar to those observed for antiplasmodial activities, with a slight increase for the 21-day extract, a modest increase for the solid support extract compared to the liquid support extract, and a similar activity observed for both A1 and MB media composition.

Micromonospora sp. SH-57 was also studied to assess the impact of culture conditions on microbial metabolite production. The same parameters were investigated, including incubation time, culture support, and medium composition. The culture time also showed an increase in the number of visible peaks in the HPLC-CAD analyses. The study by Armin et al. (2021) demonstrated the influence of culture time on siderophore production in actinobacteria,

Streptomyces ciscaucasicus [

46], supporting the importance of culture time. The culture support had a significant influence on the number and intensity of observed peaks, with liquid culture being more favorable. The extract derived from 21-day liquid culture on A1 medium exhibited all detected peaks, often at maximum intensities. This favorable support is also confirmed with MB medium, which is less interesting for microbial metabolite production than A1 medium.

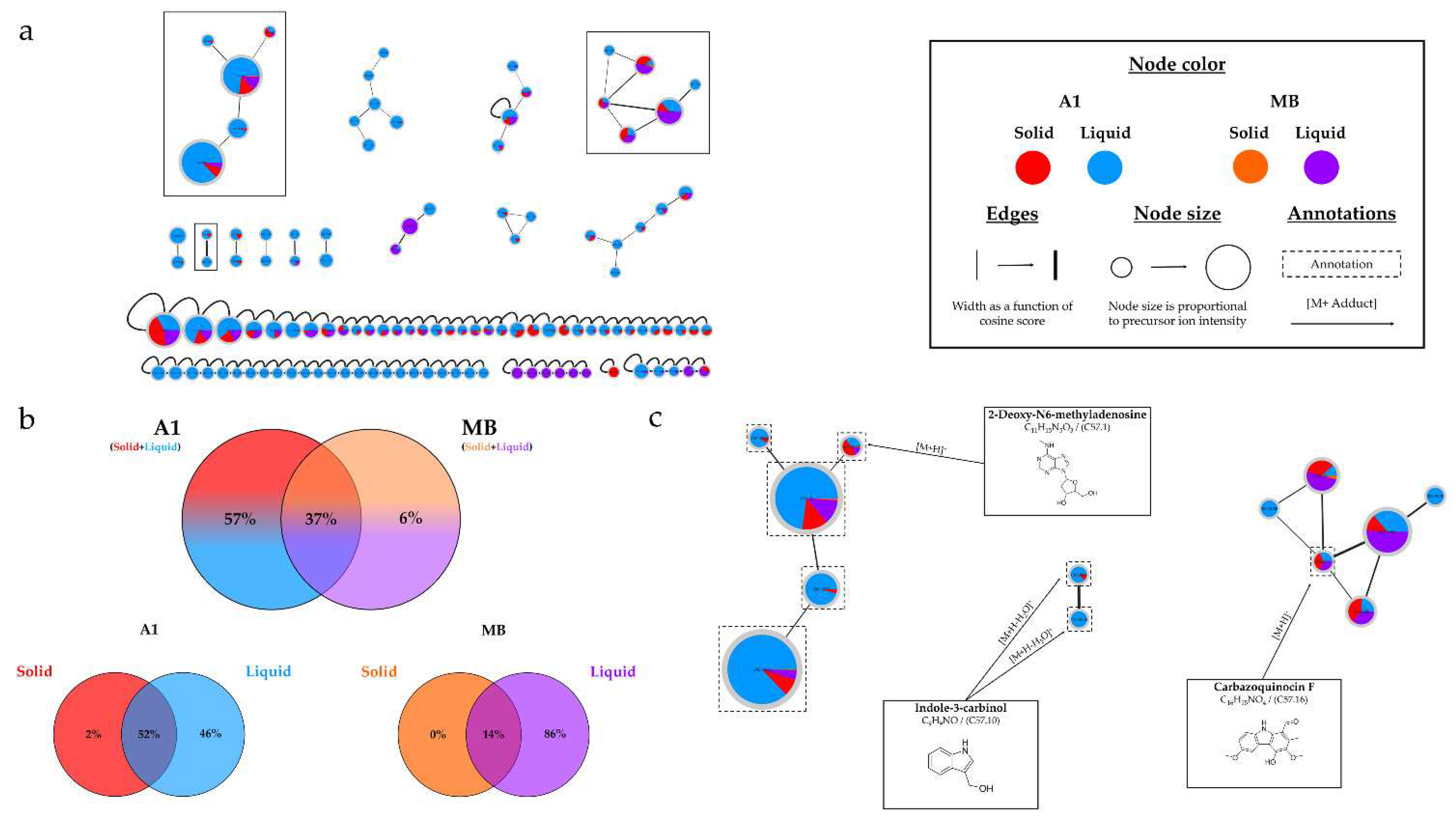

The HRMS-MS analyses corroborated the previous observations, indicating that an increased culture time, along with the use of liquid support and A1 medium, provides the best combination for obtaining a large number of metabolites, consistent with the number of nodes present in the different molecular networks (

Figure 8 and

Figure 11). Among the annotations made for this strain, 5 were obtained using two distinct bioinformatic tools, including carbazoquinocin. These molecules were isolated in 1995 from

Streptomyces violaceus [

47], and several nodes within the cluster were annotated to this same family, reinforcing their identifications. Another consensus annotation was Aloesol, a chromone isolated from rhubarb [

48], and a compound with similar structure was also isolated from a

Micromonospora sp. [

49]. The annotated compound as 2-Deoxy-N6-methyladenosine, showed a similarity percentage of 93% (Table S.5) with the SIRIUS annotation tool, and a similar compound isolated from a

Streptomyces, Aristeromycin [

50], was also proposed by the tool. The annotations obtained for this strain are less precise and not strongly correlated with the literature, unlike the

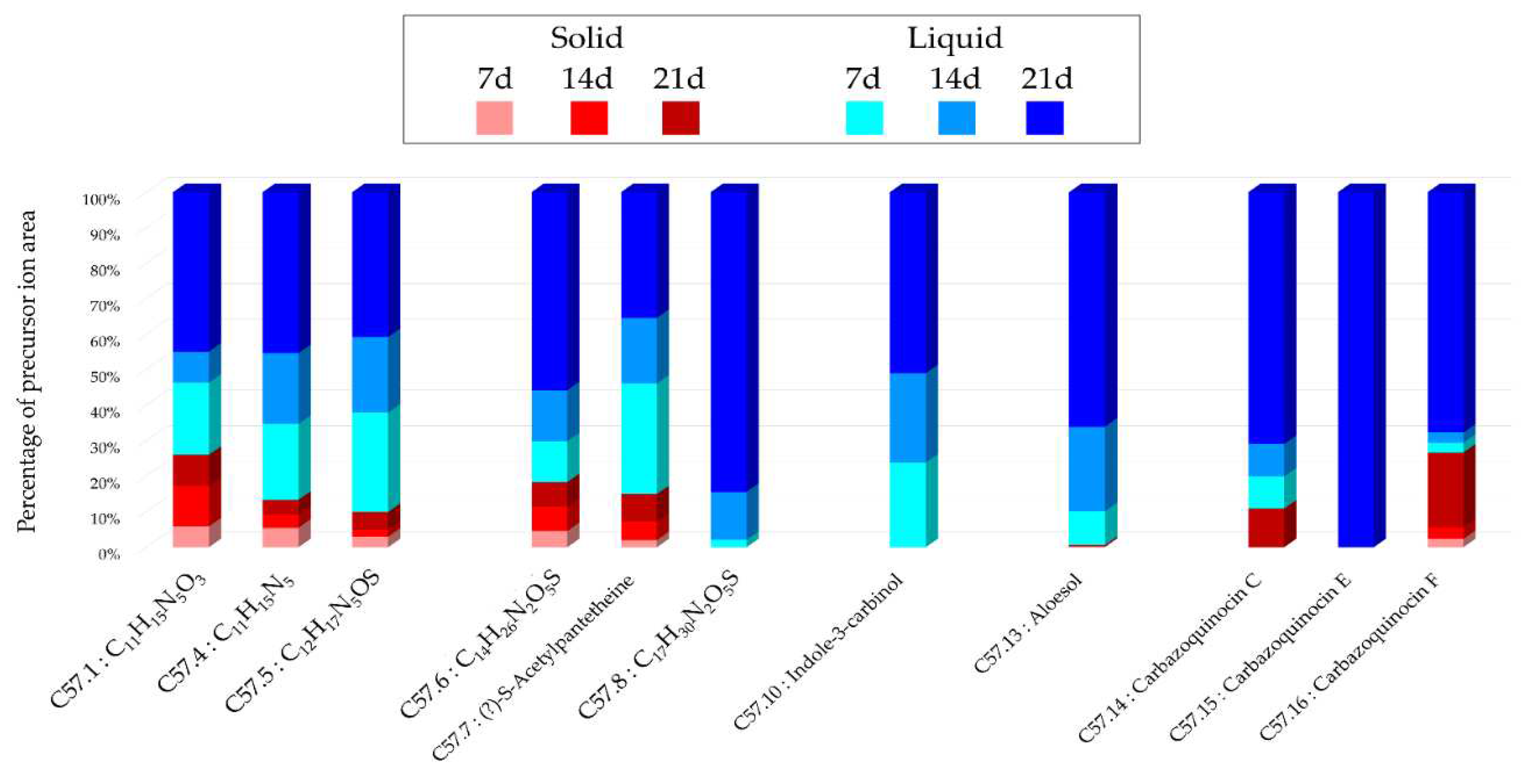

Micromonospora sp. SH-82 strain. Considering the potential identifications made and the challenges related to annotation, isolating the metabolites from this strain would be very interesting to discover new structures and improve the overall network annotations. The variations in intensity of the precursor ion areas used for these annotations are consistent with the HPLC-CAD analyses. An increase in intensity is observed over time, particularly in the case of liquid support and medium A1. The extract from the 21-day culture in liquid A1 contains all annotations with maximum intensities and sometimes unique peaks, highlighting its major interest compared to other conditions.

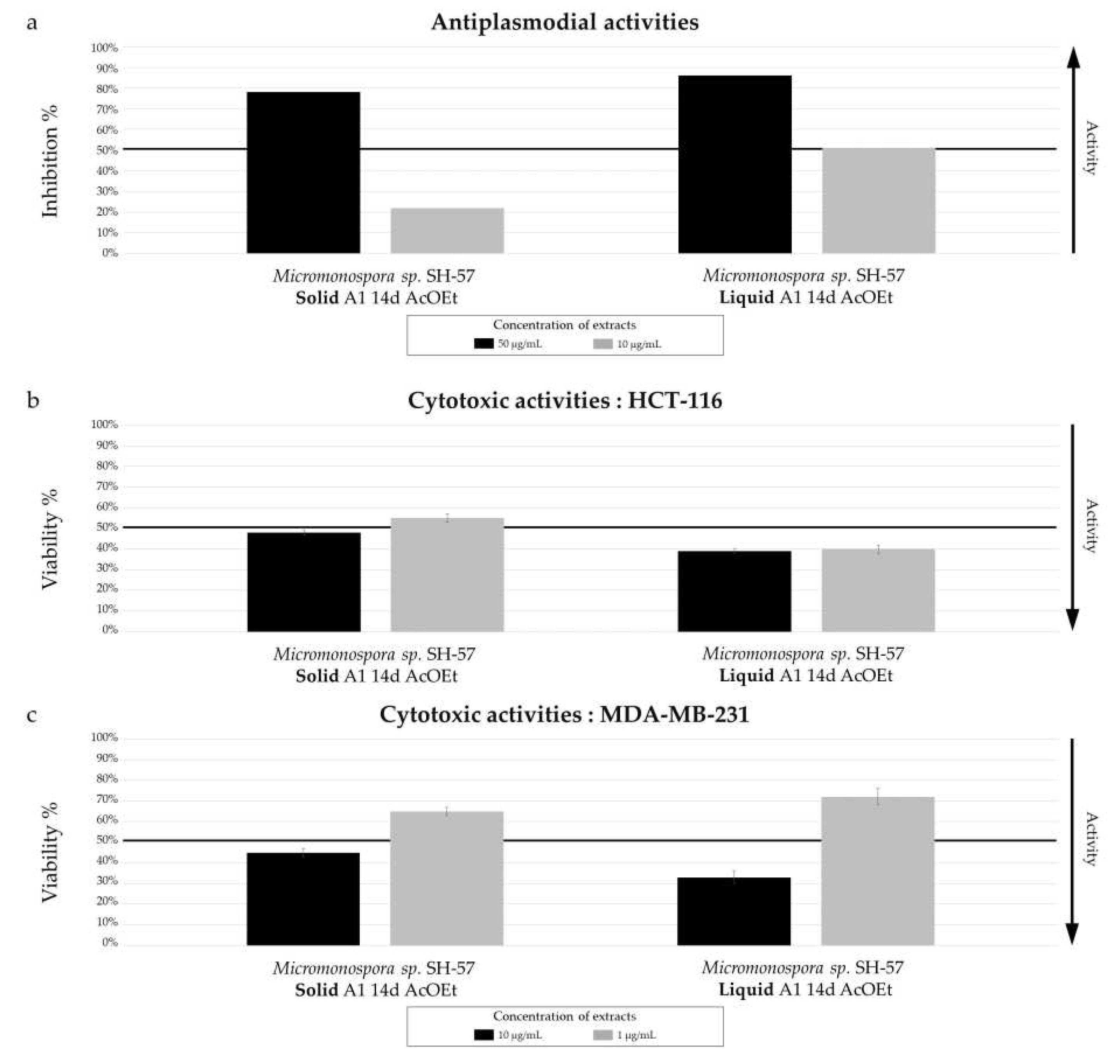

The biological activity tests conducted on two extracts from solid and liquid cultures at 14 days on medium A1 reveal a correlation between chemical diversity and biological activity. The extract from the liquid culture shows promising antiplasmodial activity compared to the solid culture, with a measured IC

50 of 12.06 ± 1.93 µg/mL. However, the anticancer activity is not very promising for both extracts, though an increase in activity is observed in the liquid culture, especially against the MDA-MB-231 cell line. Despite the limitation of a low quantity of microbial metabolites revealed by the HPLC-CAD analysis, observable biological activities suggest potential promise for the pure molecules. The described biological activities may originate from various annotated molecules, such as chromones [

51] , carbazoquinocins [

52], or purine derivatives [

53], which exhibit known biological activities.

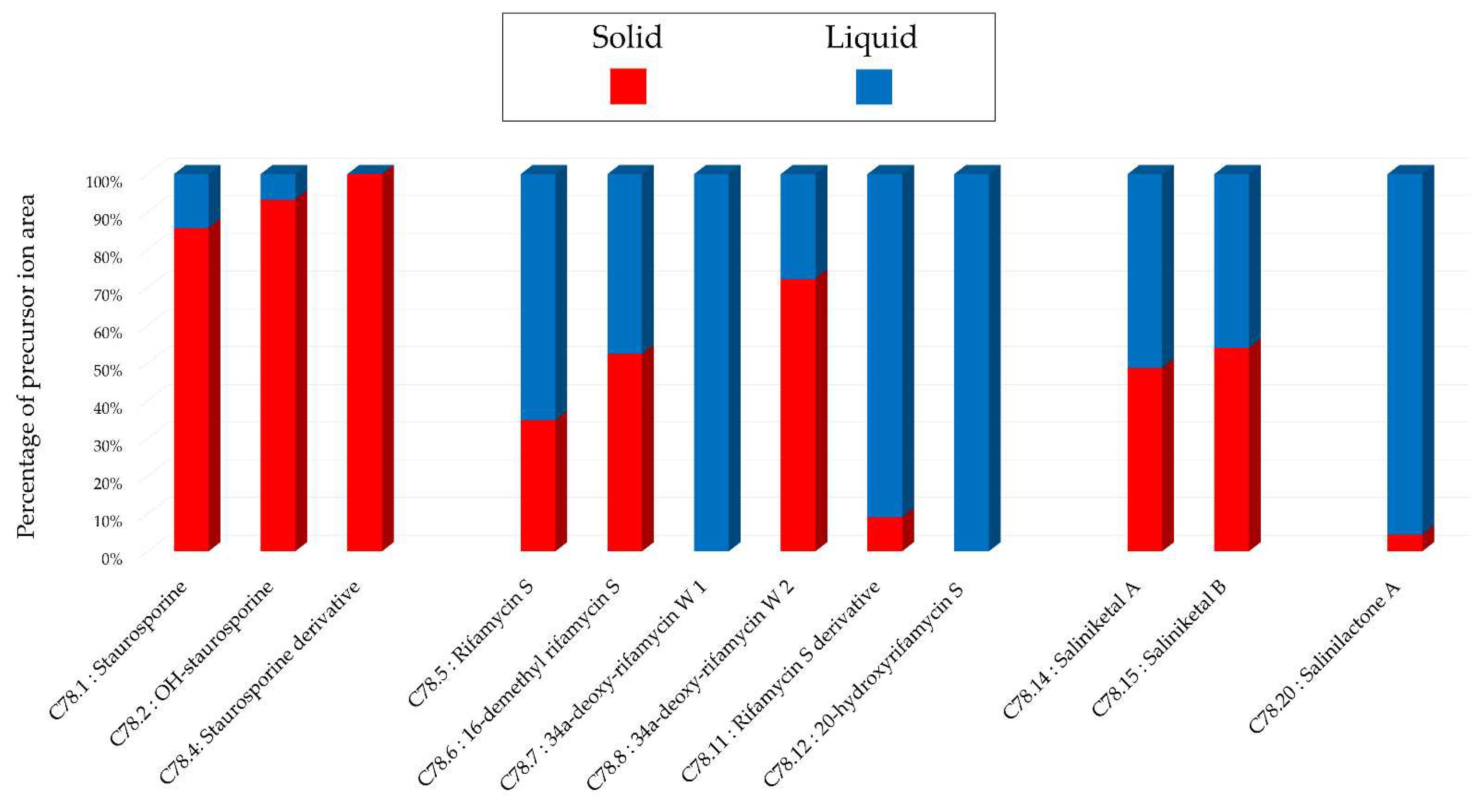

The last studied strain was

Salinispora arenicola SH-78, described in the literature as a model microorganism for its of production original and bioactive metabolites [

15]. The culture parameters studied included incubation times of 7, 14, and 21 days for solid cultures in A1 medium, culture support (liquid or solid) cultures in A1 medium for 14 days, and the use of two successive solvents, ethyl acetate and methanol, for extracting the metabolites from the latter. HPLC-CAD analyses did not show significant differences in the number of visible peaks for the different solid cultures. However, a slight increase in peak intensity was observed in the extract from the liquid culture compared to the solid culture.

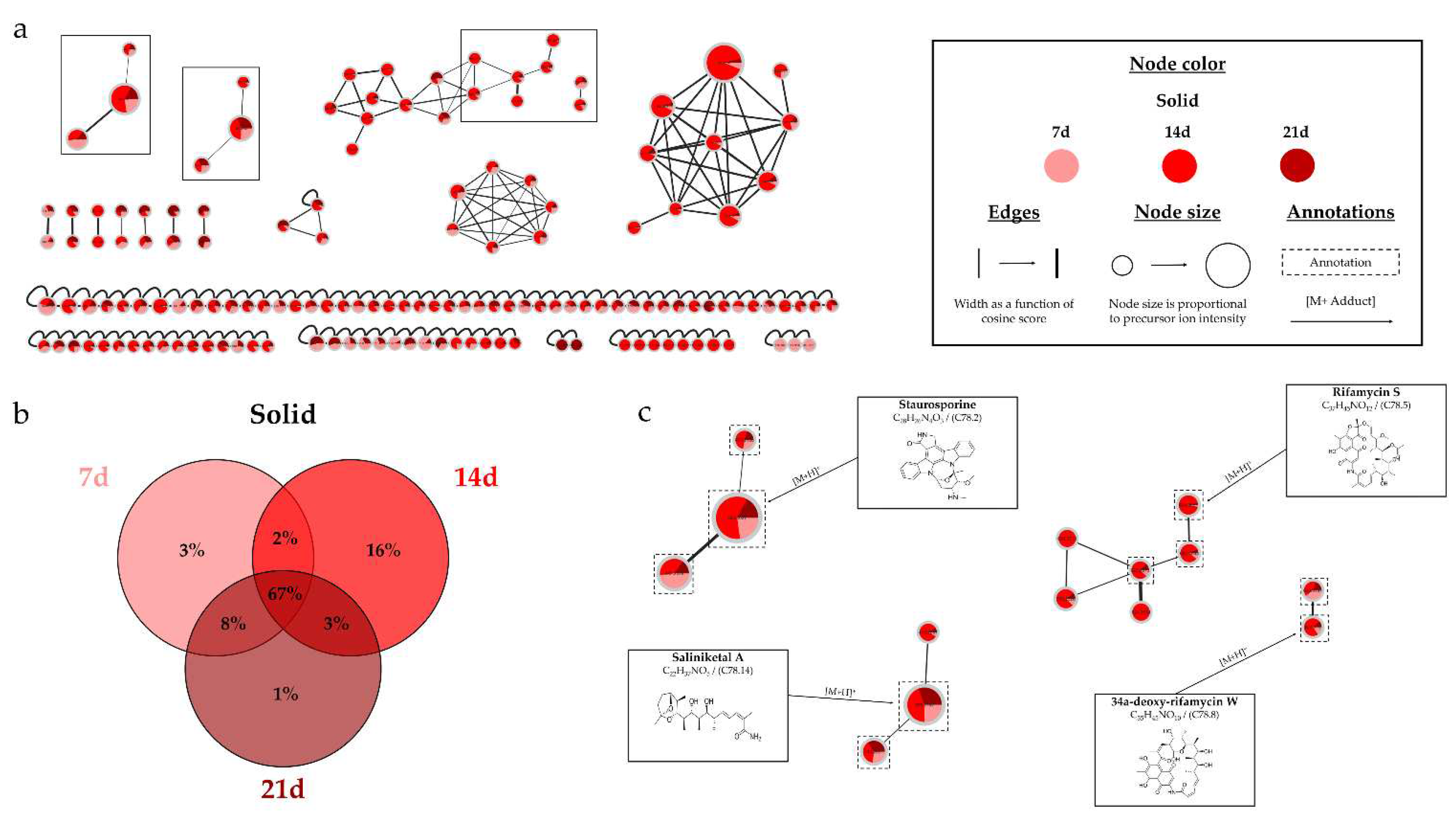

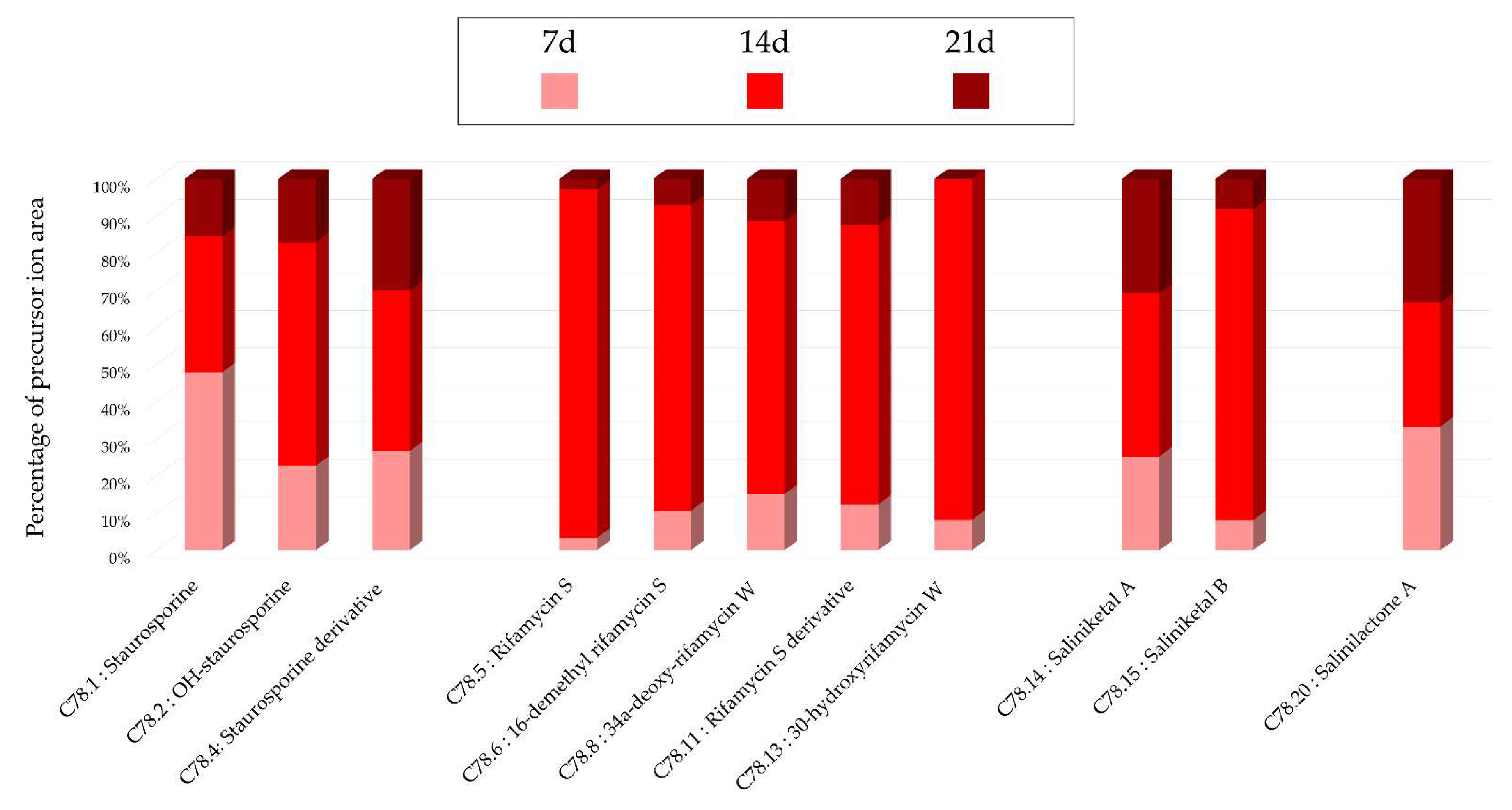

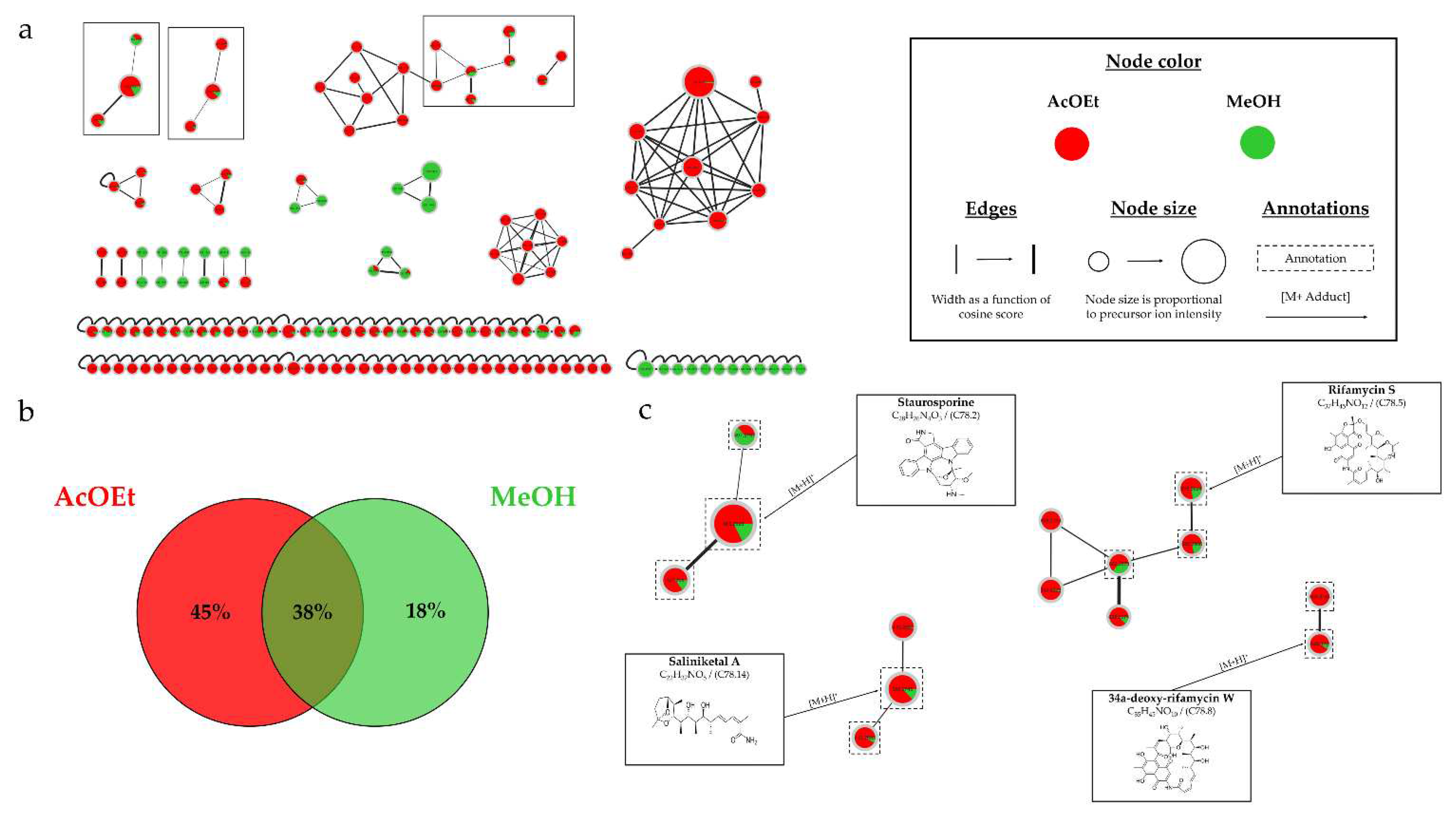

HRMS-MS analyses confirmed the culture support influenced the metabolic diversity, with an increase in the number of nodes for the extract derived from the liquid culture.

Figure 13.b demonstrates that 95% of the nodes are found in the liquid culture extract, with 26% being unique. This impact of the culture support was also demonstrated in the study by Crüsemann et al. (2017), which compared 35

Salinispora strains on solid and liquid A1 medium [

54]. In their study, the solid support appeared to be more favorable for the production of a large number of microbial metabolites. The divergence from our results could be attributed to the study of different

Salinispora species, which have significant interspecific differences [

55], or the use of amberlite resin, which influences the production of microbial metabolites [

39]. The results demonstrated a significant increase in the number of nodes over time, particularly from 14 days, with 98% of nodes detected compared to only 61% at 7 days. This impact is supported by the study of Crüsemann et al. (2017), which demonstrated an increase in the number of nodes up to 28 days for liquid cultures of

Salinispora arenicola CNH-877 in ISP2 medium [

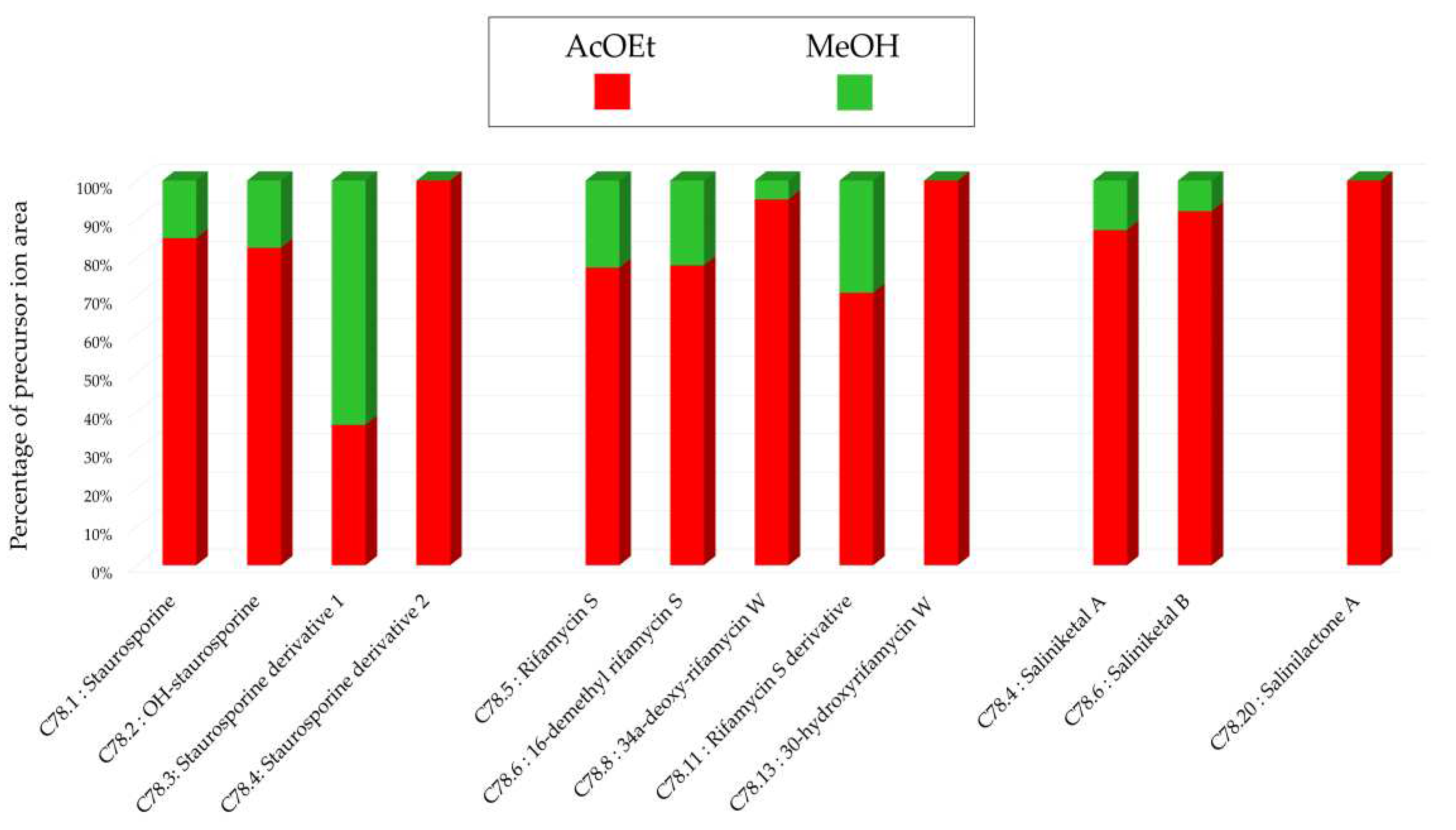

54]. The study of using two successive solvents, ethyl acetate and methanol, demonstrated that the first solvent extracted the majority of metabolites. However, 55% of the nodes were also present in the second extract, with 17% being unique, illustrating the benefit of using two different solvents to increase the quantity and diversity of metabolites. Crüsemann et al. (2017) also showed the advantage of using 3 different solvents to broaden the range of extracted molecules [

54]. The annotations revealed the presence of several metabolites from different families, some of which are well-known in the literature as being produced by

Salinispora sp., such as staurosporines, saliniketals, ryfamicins, and salinilactones [

11,

15,

56]. Three annotations led to the same identification by the different bioinformatics tools, namely OH-staurosporine, staurosporine, and rifamycin S. The consensus annotations, the study of biosynthetic pathways [

57], and the literature reinforce the identification of these microbial metabolites. Despite thorough investigation, the two main clusters (

Figure S3) could not be clearly identified. Therefore, it would be relevant to proceed with the isolation and identification of these compounds due to the promising potential of

Salinispora sp. [

15]. Within the cluster of staurosporines (

Figure 1.c), a stronger intensity of precursor ion peaks is observed for the extract derived from solid support culture. Among this family, the node annotated as 4'-demethyl-Af-formyl-7V-hydroxy-staurosporine exhibits its highest intensity in the methanolic extract, reinforcing the relevance of using different solvents. For other annotations, the maximum intensity is predominantly derived from the extract originating from liquid culture, as indicated by the nodes annotated as salinilactones. These results demonstrate that the optimal parameters may vary depending on the type of targeted molecules.

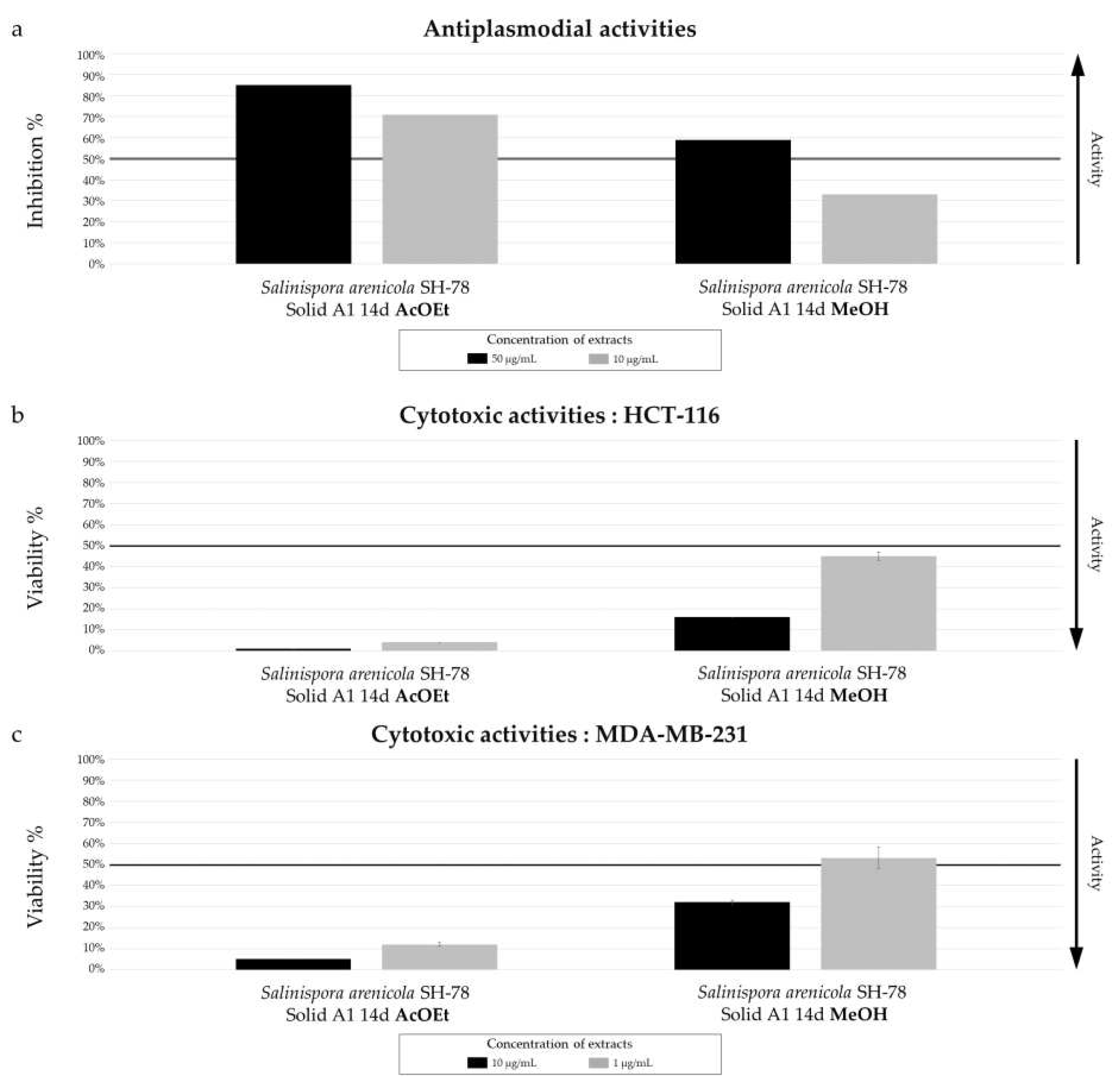

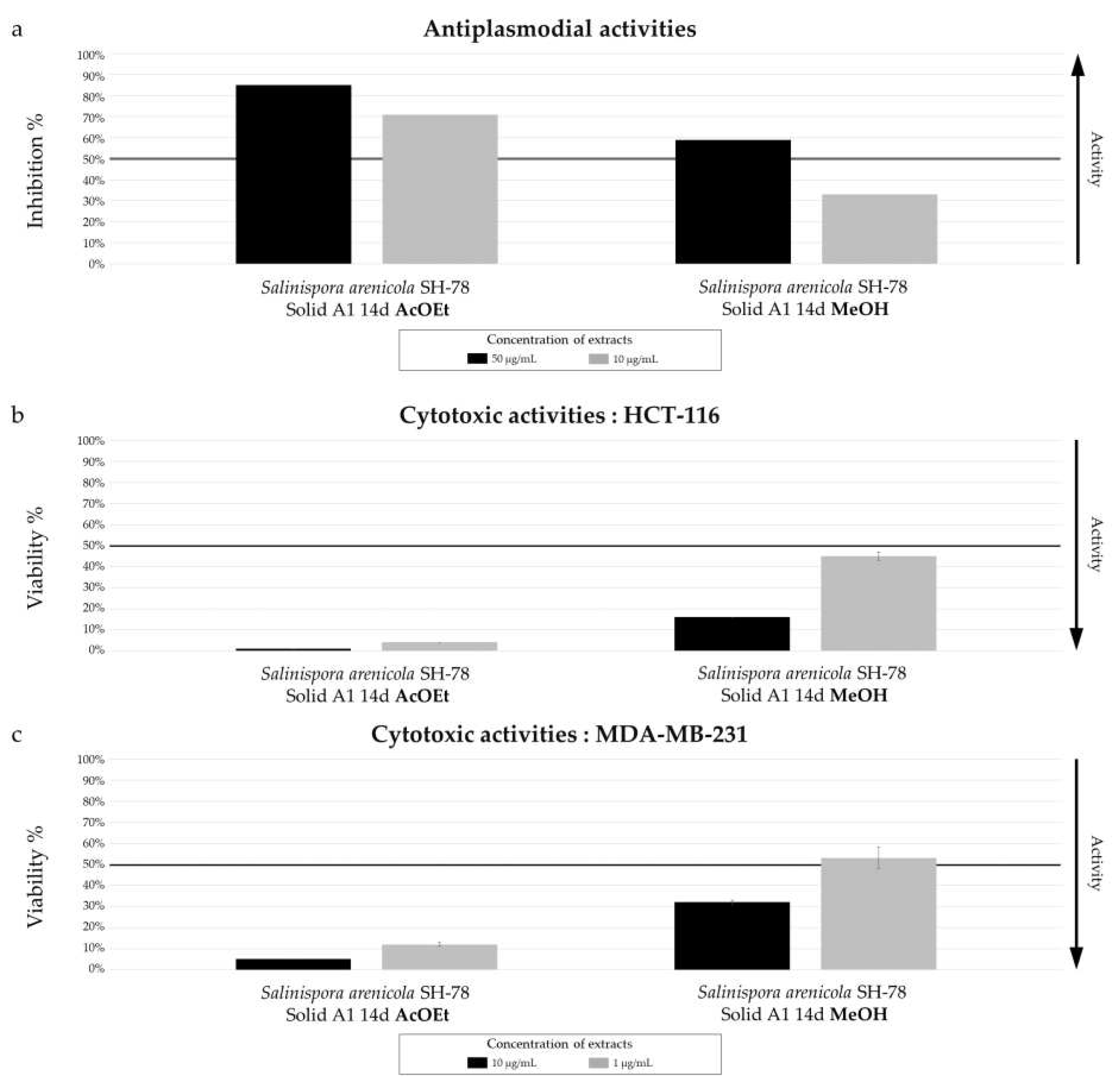

The biological activities described in this study were conducted on the extracts obtained through successive extraction with ethyl acetate and methanol from cultures on A1 medium for 14 days. Both extracts feature remarkable activities, especially the cytotoxic activity against the two cell lines. This activity may be attributed to the presence of staurosporine and its derivatives, present in both extracts, as demonstrated by Jimenez et al. (2012) [

58] and Xiaol et al. (2018) [

16].

The present study has highlighted the impact of culture parameters on the metabolic diversity and biological activity of different marine-derived actinobacteria. Despite their similarity, differences in the influence of culture conditions have been observed among each strain, and variations in intensity have also been demonstrated depending on the specific metabolite families. Among the parameters studied, the culture medium is already well known to be a major factor influencing the production of specialized metabolites [

24]. Additionally, less studied parameters such as incubation time and culture support have also shown significant effects. This study could be combined with a strain prioritization approach to select the most promising bacteria from a large strain collection. Prioritization can be achieved using genomic, chemical, or biological approaches [

59,

60,

61]. To optimize the selection of strains and culture parameters, microplate cultures offer the advantage of working with a large number of microorganisms and rapidly evaluating the effects of various parameters, such as the culture medium [

54]. This approach would allow combining the selection of promising microorganisms with the identification of optimal culture conditions, while facilitating rapid biological and chemical screening. After culturing the selected strains under the best conditions, more precise adjustments of parameters could be considered to enhance the chemical diversity or targeted metabolite production, as demonstrated in the study by Jezkova et al. (2021) [

62]. These combined approaches could accelerate the discovery of new bioactive molecules and optimize their production for therapeutic or industrial purposes.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. (a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from solid cultures at 7

(pink), 14 (red) and 21 days (maroon) and from liquid cultures of 7 (sky blue), 14 (standard blue) and

21 days (dark blue) of Micromonospora sp. SH-82. (b) Venn diagrams showing the percentage of nodes

as a function of culture parameters, depending on the culture support at the top and time details at

the bottom. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. (a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from solid cultures at 7

(pink), 14 (red) and 21 days (maroon) and from liquid cultures of 7 (sky blue), 14 (standard blue) and

21 days (dark blue) of Micromonospora sp. SH-82. (b) Venn diagrams showing the percentage of nodes

as a function of culture parameters, depending on the culture support at the top and time details at

the bottom. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts

from the solid and liquid culture of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 at different times (7, 14, 21 days).

Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion

area intensities. Red gradient represents extract from solid culture. Pink: 7 days; Red: 14 days; Brown:

21 days. Blue gradient represents extract from solid culture. Sky blue: 7 days; Standard blue: 14 days;

Dark blue: 21 days.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts

from the solid and liquid culture of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 at different times (7, 14, 21 days).

Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion

area intensities. Red gradient represents extract from solid culture. Pink: 7 days; Red: 14 days; Brown:

21 days. Blue gradient represents extract from solid culture. Sky blue: 7 days; Standard blue: 14 days;

Dark blue: 21 days.

Figure 3.

Biological activity of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 extracts from culture A1 solid medium for 14 days and 21 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL (grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL (grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.

Figure 3.

Biological activity of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 extracts from culture A1 solid medium for 14 days and 21 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL (grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL (grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.

Figure 4.

Biological activity of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 extracts from culture on A1 solid and liquid medium for 14 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL(grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL (grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.

Figure 4.

Biological activity of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 extracts from culture on A1 solid and liquid medium for 14 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL(grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL (grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.

Figure 5.

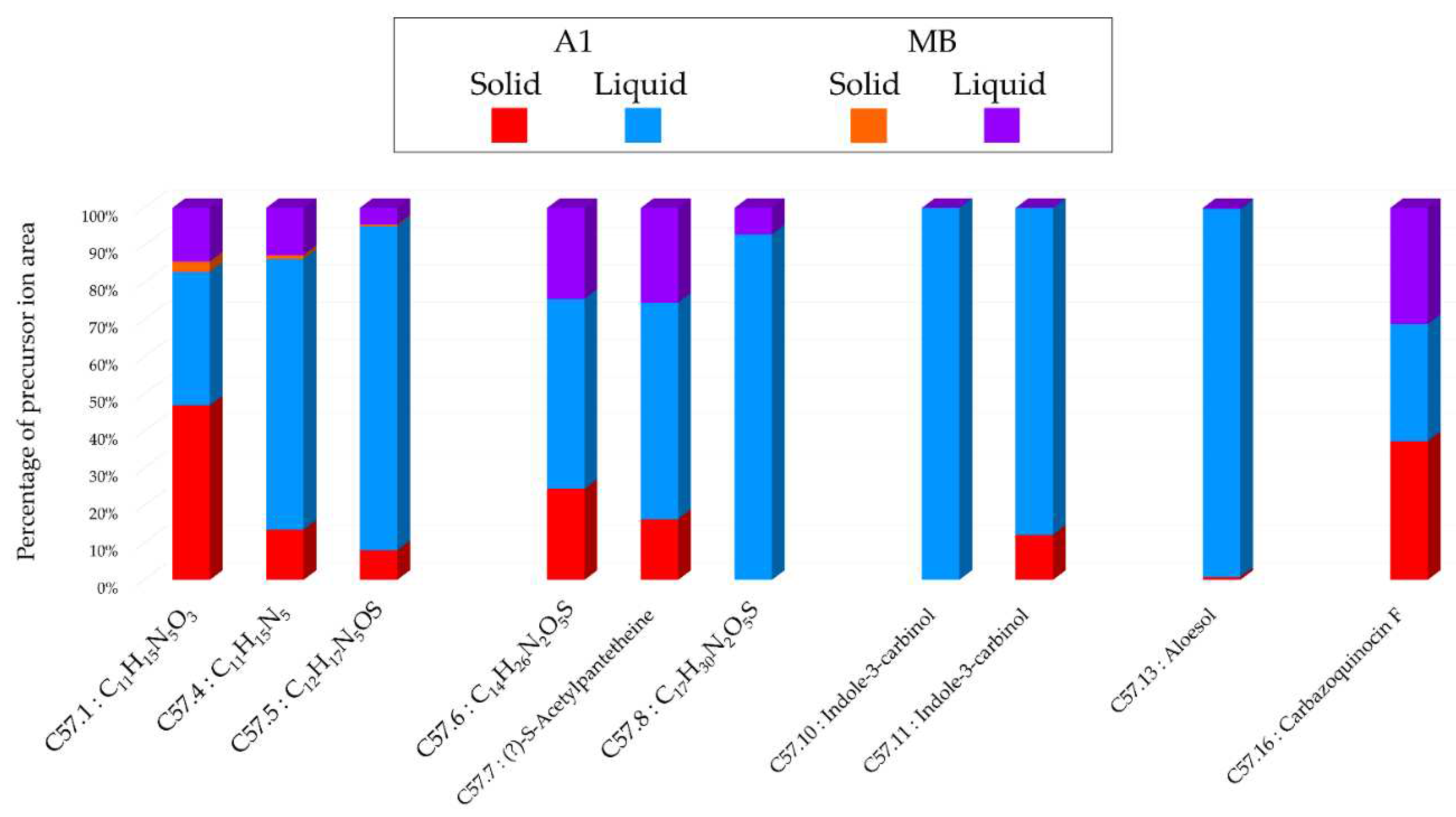

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from cultures of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 on A1 solid (red) and liquid (standard blue) medium and MB solid (orange) and liquid (purple) medium, at 14 days. (b) Venn diagrams showing the percentage of nodes as a function of culture parameters, depending on the culture medium composition at the top and support culture details at the bottom. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 5.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from cultures of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 on A1 solid (red) and liquid (standard blue) medium and MB solid (orange) and liquid (purple) medium, at 14 days. (b) Venn diagrams showing the percentage of nodes as a function of culture parameters, depending on the culture medium composition at the top and support culture details at the bottom. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 6.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from the solid and liquid culture of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 at 14 days on A1 and MB medium. Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red: extracts from solid A1 culture; Blue: extracts from liquid A1 culture; Orange: extracts from solid MB culture; Purple: extracts from liquid A1 culture.

Figure 6.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from the solid and liquid culture of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 at 14 days on A1 and MB medium. Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red: extracts from solid A1 culture; Blue: extracts from liquid A1 culture; Orange: extracts from solid MB culture; Purple: extracts from liquid A1 culture.

Figure 7.

Biological activity of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 extracts from culture on A1 and MB solid medium for 14 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL (grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL(grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.

Figure 7.

Biological activity of Micromonospora sp. SH-82 extracts from culture on A1 and MB solid medium for 14 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL (grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL(grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.

Figure 8.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from solid cultures at 7 (pink), 14 (red) and 21 days (maroon) and from liquid cultures of 7 (sky blue), 14 (standard blue) and 21 days (dark blue) of Micromonospora sp. SH-57. (b) Venn diagrams showing the percentage of nodes as a function of culture parameters, depending on the culture support at the top and time details at the bottom. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 8.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from solid cultures at 7 (pink), 14 (red) and 21 days (maroon) and from liquid cultures of 7 (sky blue), 14 (standard blue) and 21 days (dark blue) of Micromonospora sp. SH-57. (b) Venn diagrams showing the percentage of nodes as a function of culture parameters, depending on the culture support at the top and time details at the bottom. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 9.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from the solid and liquid culture of Micromonospora sp. SH-57 at different times (7, 14, 21 days). Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red gradient represents extract from solid culture. Pink: 7 days; Red: 14 days; Brown: 21 days. Blue gradient represents extract from solid culture. Sky blue: 7 days; Standard blue: 14 days; Dark blue: 21 days.

Figure 9.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from the solid and liquid culture of Micromonospora sp. SH-57 at different times (7, 14, 21 days). Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red gradient represents extract from solid culture. Pink: 7 days; Red: 14 days; Brown: 21 days. Blue gradient represents extract from solid culture. Sky blue: 7 days; Standard blue: 14 days; Dark blue: 21 days.

Figure 10.

Biological activity of Micromonospora sp. SH-57 extracts from culture on A1 solid and liquid medium for 14 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL (grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL (grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.

Figure 10.

Biological activity of Micromonospora sp. SH-57 extracts from culture on A1 solid and liquid medium for 14 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL (grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL (grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.

Figure 11.

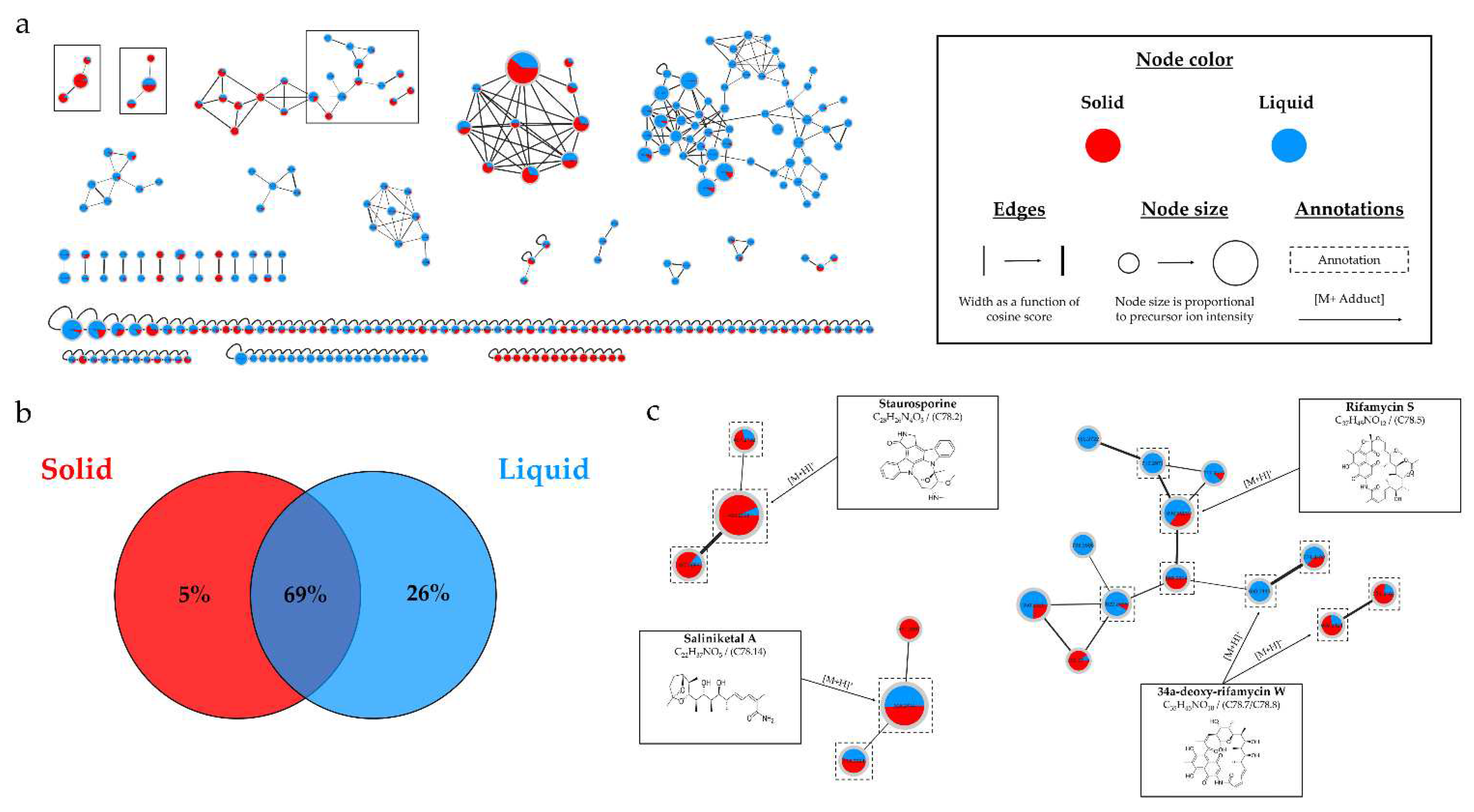

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from cultures of Micromonospora sp. SH-57 on A1 solid (red) and liquid (standard blue) medium and MB solid (orange) and liquid (purple) medium, at 14 days. (b) Venn diagrams showing the percentage of nodes as a function of culture parameters, depending on the culture medium composition at the top and support culture details at the bottom. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 11.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from cultures of Micromonospora sp. SH-57 on A1 solid (red) and liquid (standard blue) medium and MB solid (orange) and liquid (purple) medium, at 14 days. (b) Venn diagrams showing the percentage of nodes as a function of culture parameters, depending on the culture medium composition at the top and support culture details at the bottom. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 12.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from the solid and liquid culture of Micromonospora sp. SH-57 at 14 days on A1 and MB medium. Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red: extracts from solid A1 culture; Blue: extracts from liquid A1 culture; Orange: extracts from solid MB culture; Purple: extracts from liquid A1 culture.

Figure 12.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from the solid and liquid culture of Micromonospora sp. SH-57 at 14 days on A1 and MB medium. Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red: extracts from solid A1 culture; Blue: extracts from liquid A1 culture; Orange: extracts from solid MB culture; Purple: extracts from liquid A1 culture.

Figure 13.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from solid (red) and liquid (blue) culture of Salinispora arenicola SH-78 in A1 medium, at 14 days. (b) Venn diagram showing the percentage of nodes as a function of support culture. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 13.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from solid (red) and liquid (blue) culture of Salinispora arenicola SH-78 in A1 medium, at 14 days. (b) Venn diagram showing the percentage of nodes as a function of support culture. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 14.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from extracts from 14-day A1 solid and liquid cultures of Salinispora arenicola SH-78. Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red: extract from solid culture ; Blue: extract from liquid culture.

Figure 14.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from extracts from 14-day A1 solid and liquid cultures of Salinispora arenicola SH-78. Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red: extract from solid culture ; Blue: extract from liquid culture.

Figure 15.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from solid cultures of Salinispora arenicola SH-78 at 7 (pink), 14 (red) and 21 days (maroon). (b) Venn diagram showing the percentage of nodes as a function of cultivation time. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 15.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of microbial extracts from solid cultures of Salinispora arenicola SH-78 at 7 (pink), 14 (red) and 21 days (maroon). (b) Venn diagram showing the percentage of nodes as a function of cultivation time. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 16.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from the solid cultures of Salinispora arenicola SH-78 at the different times (7, 14, 21 days). Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Pink: extract from solid culture at 7 days; Red: 14 days; Brown: 21 days.

Figure 16.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with extracts from the solid cultures of Salinispora arenicola SH-78 at the different times (7, 14, 21 days). Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Pink: extract from solid culture at 7 days; Red: 14 days; Brown: 21 days.

Figure 17.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of AcOEt (red) and MeOH (green) extracts from 14-day solid A1 culture of Salinispora arenicola SH-78. (b) Venn diagram showing the percentage of nodes as a function of the solvent used. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 17.

(a) Ion Identity Molecular Network (IIMN) of AcOEt (red) and MeOH (green) extracts from 14-day solid A1 culture of Salinispora arenicola SH-78. (b) Venn diagram showing the percentage of nodes as a function of the solvent used. (c) Zoom on clusters of interest with examples of annotations.

Figure 18.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with ethyl acetate (AcOEt) and methanolic (MeOH) extracts from 14-day solid A1 culture of Salinispora arenicola SH-78. Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red: AcOEt extract ; Green: MeOH extract.

Figure 18.

Histograms representing the main annotations made in this network designed with ethyl acetate (AcOEt) and methanolic (MeOH) extracts from 14-day solid A1 culture of Salinispora arenicola SH-78. Histograms presents the proportion attributed to each culture condition relative to the precursor ion area intensities. Red: AcOEt extract ; Green: MeOH extract.

Figure 19.

Biological activity of

Salinispora arenicola SH-78 extracts AcOET and MeOH from culture on A1 solid medium for 14 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against

P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL (grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL (grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.The results demonstrate a significant difference in biological activity between the two extracts. The AcOEt extract shows 70% antiplasmodial inhibition at 10 µg/mL, while the MeOH extract only 32%. The median inhibitory concentration (IC

50) of the AcOEt extract was measured at 2.57 ± 0.90 µg/mL, which is promising for a crude extract. For anticancer activity, both extracts showed very promising results, with very low cell viability tested for the AcOEt extract at a concentration of only 1 µg/mL, with percentages of 2% for HCT-116 (

Figure 19.b) and 5% for MDA-MB-231 (

Figure 19.c). The MeOH extract also showed promising activity, with viability below 50% at 10 µg/mL for both cell lines.

Figure 19.

Biological activity of

Salinispora arenicola SH-78 extracts AcOET and MeOH from culture on A1 solid medium for 14 days. (a) Antiplasmodial activities against

P. falciparum strain 3D7, tested at 50 µg/mL (dark color) and 10 µg/mL (grey color). Cytotoxic activities against (b) HCT-116 cell line and (c) MDA-MB-231 cell line, tested at 10 µg/mL (dark color) and 1 µg/mL (grey color). The black lines indicate the threshold for considering the extract as promising, with different criteria: > 50% inhibition for antiplasmodial activity and < 50% viability for cytotoxic activity.The results demonstrate a significant difference in biological activity between the two extracts. The AcOEt extract shows 70% antiplasmodial inhibition at 10 µg/mL, while the MeOH extract only 32%. The median inhibitory concentration (IC

50) of the AcOEt extract was measured at 2.57 ± 0.90 µg/mL, which is promising for a crude extract. For anticancer activity, both extracts showed very promising results, with very low cell viability tested for the AcOEt extract at a concentration of only 1 µg/mL, with percentages of 2% for HCT-116 (

Figure 19.b) and 5% for MDA-MB-231 (

Figure 19.c). The MeOH extract also showed promising activity, with viability below 50% at 10 µg/mL for both cell lines.

Table 1.

Summary table of annotations from the different extracts of Micromonospora sp. SH-82.

Table 1.

Summary table of annotations from the different extracts of Micromonospora sp. SH-82.

| Compound ID |

Molecular formula |

Compound name or InChIKey (1,2,3)

|

Precursor ion area observed in MzMine

(with the maximum in bold) according to the culture conditions |

| Medium |

|

A1 |

|

MB |

| Support |

|

Solid |

|

Liquid |

|

Solid |

Liquid |

| Days |

|

7 |

14 |

21 |

|

7 |

14 |

21 |

|

14 |

| C82.1 |

C44H80N2O15

|

Megalomicin A (1,3)

|

|

|

2,0E+02 |

3,0E+03 |

6,6E+03 |

|

1,0E+02 |

2,0E+02 |

2,0E+02 |

|

1,0E+02 |

5,0E+02 |

| C82.2 |

C45H78N2O17

|

Megalomicin B (1,3)

|

|

|

1,4E+02 |

5,2E+03 |

8,1E+03 |

|

2,0E+02 |

1,0E+03 |

1,0E+03 |

|

- |

1,5E+03 |

| C82.3 |

C47H84N2O16

|

4’-Propionylmegalomicin A (1)

|

|

|

1,0E+02 |

1,3E+03 |

2,2E+03 |

|

1,0E+02 |

3,0E+02 |

3,0E+02 |

|

- |

6,0E+02 |

| C82.4 |

C48H84N2O17

|

Megalomicin C1 (1,3)

|

|

|

1,0E+02 |

3,5E+03 |

5,7E+03 |

|

3,3E+03 |

7,1E+03 |

6,7E+03 |

|

- |

1,3E+03 |

| C82.5 |

C49H86N2O17

|

Megalomicin C2 (1,3)

|

|

1,0E+02 |

1,2E+03 |

1,7E+03 |

1,4E+03 |

3,4E+03 |

3,5E+03 |

|

- |

1,1E+03 |

| C82.6 |

C39H69NO14

|

2’-O-Acetylerythromycin A (1)

|

|

5,0E+02 |

8,0E+03 |

5,9E+03 |

6,0E+03 |

9,8E+03 |

1,2E+04 |

|

5,0E+01 |

4,2E+03 |

| C82.7 |

C36H65NO13

|

Erythromycin C (1)

|

|

6,7E+03 |

4,8E+04 |

4,9E+04 |

1,8E+04 |

3,0E+04 |

2,7E+04 |

|

1,0E+03 |

1,3E+04 |

| C82.8 |

C36H65NO13

|

13-Deethyl-13-methylerythromycin (1)

|

|

4,8E+03 |

4,2E+03 |

2,0E+03 |

2,1E+04 |

4,5E+04 |

2,8E+04 |

|

5,0E+02 |

3,0E+03 |

| C82.9 |

C36H65NO12

|

Erythromycin D (1)

|

|

6,0E+03 |

1,3E+05 |

1,4E+05 |

6,8E+04 |

9,5E+04 |

7,0E+04 |

|

5,0E+02 |

1,7E+04 |

| C82.10 |

C37H67NO12

|

Erythromycin B (1,3)

|

|

- |

1,5E+03 |

3,2E+03 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

| C82.11 |

C36H65NO12

|

6-Desmethyl erythromycin D (3)

|

|

7,3E+02 |

4,3E+03 |

3,7E+03 |

1,0E+03 |

5,0E+02 |

5,0E+02 |

|

1,0E+02 |

1,0E+03 |

| C82.12 |

C29H53NO9

|

3-O-De(3-C,3-O-dimethyl-2,6-dideoxy-alpha-L-ribo-hexopyranosyl)-6-deoxyerythromycin (1)

|

|

- |

3,6E+03 |

5,5E+03 |

- |

- |

- |

|

2,0E+02 |

- |

| C82.13 |

C29H53NO9

|

|

- |

8,0E+02 |

1,0E+03 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

| C82.14 |

C36H65NO12

|

6-Deoxy-3'-O-demethylerythromycin (1)

|

|

1,0E+02 |

1,3E+03 |

1,6E+03 |

2,0E+03 |

1,0E+02 |

1,0E+02 |

|

1,0E+01 |

5,0E+01 |

| C82.15 |

C35H63NO13

|

Norerythromycin (1)

|

|

5,0E+02 |

1,0E+03 |

5,0E+02 |

5,0E+02 |

1,0E+03 |

1,4E+03 |

|

1,0E+02 |

1,9E+03 |

| C82.16 |

C21H38O7

|

Erythronolide B (1)

|

|

7,9E+04 |

>2E+05* |

>2E+05* |

8,0E+04 |

1,7E+05 |

>2E+05* |

|

6,2E+04 |

>2E+05* |

| C82.17 |

C20H36O7

|

2-Desmethyl-2-hydroxy-6-deoxyerythronolide B (1)

|

|

1,0E+02 |

1,9E+03 |

1,1E+03 |

2,0E+02 |

7,0E+02 |

5,0E+02 |

|

5,0E+01 |

2,0E+02 |

| C82.18 |

C28H50O10

|

3-O-Alpha-mycarosylerythronolide B (1)

|

|

1,5E+04 |

8,8E+04 |

1,3E+05 |

6,7E+04 |

1,5E+05 |

1,5E+05 |

|

8,8E+03 |

6,9E+04 |

| C82.19 |

C27H48O10

|

3-O-(alpha-L-olivosyl)erythronolide B (1)

|

|

1,7E+03 |

1,2E+04 |

1,6E+04 |

4,2E+03 |

7,9E+03 |

7,3E+03 |

|

5,0E+02 |

4,3E+03 |

| C82.20 |

|

5,0E+02 |

1,1E+03 |

2,0E+03 |

5,0E+02 |

1,7E+03 |

2,0E+03 |

|

5,0E+01 |

3,0E+02 |

| C82.21 |

C21H38O6

|

6-Deoxyerythronolide B (1,3)

|

|

2,5E+04 |

1,2E+05 |

1,4E+05 |

5,3E+04 |

6,9E+04 |

7,3E+04 |

|

1,5E+04 |

6,7E+04 |

Table 2.

Summary table of annotations from the different extracts of Micromonospora sp. SH-57.

Table 2.

Summary table of annotations from the different extracts of Micromonospora sp. SH-57.

| Compound ID |

Molecular formula |

Compound name or InChIKey (1,2,3)

|

Precursor ion area observed in MzMine(with the maximum in bold) according to the culture conditions |

| Medium |

|

A1 |

|

MB |

| Support |

|

Solid |

|

Liquid |

|

Solid |

Liquid |

| Days |

|

7 |

14 |

21 |

|

7 |

14 |

21 |

|

14 |

| C57.1 |

C11H15N5O3

|

2-Deoxy-N6-methyladenosine (1)

|

|

|

5,0E+02 |

9,8E+02 |

7,5E+02 |

|

1,7E+03 |

7,5E+02 |

3,8E+03 |

|

6,0E+01 |

3,0E+02 |

| C57.2 |

C11H15N5O |

SXIDRQQQIPLCTJ (1)

|

|

|

2,0E+02 |

2,0E+02 |

2,0E+02 |

|

2,0E+03 |

2,0E+03 |

6,8E+03 |

|

- |

- |

| C57.3 |

C11H13N5O3

|

UHYRJPGYRFMFLT (1)

|

|

|

9,9E+02 |

4,1E+02 |

1,5E+03 |

|

8,9E+03 |

9,1E+03 |

1,4E+04 |

|

- |

- |

| C57.4 |

C11H15N5

|

9-cyclopentyl-N-methylpurin-6-amine (1)

|

|

|

5,5E+03 |

3,7E+03 |

4,1E+03 |

|

2,1E+04 |

2,0E+04 |

4,5E+04 |

|

2,8E+02 |

3,4E+03 |

| C57.5 |

C12H17N5OS |

INPAYTORGXXLMB (1)

|

|

|

3,7E+03 |

2,4E+03 |

6,4E+03 |

|

3,5E+04 |

2,7E+04 |

5,2E+04 |

|

1,0E+02 |

1,4E+03 |

| C57.6 |

C14H26N2O5S |

JDNYVZBVEBRRCT (1)

|

|

|

2,0E+02 |

3,0E+02 |

3,0E+02 |

|

5,0E+02 |

6,3E+02 |

2,4E+03 |

|

- |

3,0E+02 |

| C57.7 |

C13H24NO5S |

(?)-S-Acetylpantetheine (1)

|

|

|

4,0E+02 |

1,0E+03 |

1,5E+03 |

|

6,2E+03 |

3,7E+03 |

7,0E+03 |

|

- |

1,6E+03 |

| C57.8 |

C17H30N2O5S |

ZCNIMMSEOJFZKZ (1)

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

2,0E+02 |

1,3E+03 |

8,2E+03 |

|

- |

1,0E+02 |

| C57.9 |

C19H28N2O5S |

IXKOTSUCYPEFPP (1)

|

|

|

- |

1,0E+02 |

2,0E+02 |

|

8,0E+02 |

2,0E+03 |

5,1E+03 |

|

- |

2,0E+02 |

| C57.10 |

C9H9NO |

Indole-3-carbinol (1,2)

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

6,0E+02 |

6,3E+02 |

1,3E+03 |

|

- |

- |

| C57.11 |

|

|

1,0E+02 |

1,0E+02 |

1,0E+02 |

|

5,0E+02 |

7,2E+02 |

1,4E+03 |

|

- |

- |

| C57.12 |

C13H12O4

|

Aloesone (1)

|

|

|

- |

5,0E+01 |

1,0E+02 |

|

6,9E+03 |

3,1E+03 |

1,7E+03 |

|

- |

- |

| C57.13 |

C13H14O4

|

Aloesol (1)

|

|

|

5,0E+01 |

5,0E+01 |

5,0E+01 |

|

2,5E+03 |

6,2E+03 |

1,7E+04 |

|

- |

2,0E+01 |

| C57.14 |

C20H23NO2

|

Carbazoquinocin C (1,3)

|

|

|

- |

- |

9,6E+02 |

|

8,0E+02 |

8,0E+02 |

6,2E+03 |

|

- |

- |

| C57.15 |

C21H25NO2

|

Carbazoquinocin E (1,3)

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

1,5E+03 |

|

- |

- |

| C57.16 |

C22H27NO2

|

Carbazoquinocin F (1,3)

|

|

|

5,0E+02 |

7,2E+02 |

4,5E+03 |

|

5,9E+02 |

6,1E+02 |

1,5E+04 |

|

- |

6,0E+02 |

| C57.17 |

C24H31NO2

|

12-Carbazol-9-yldodecanoic acid (1)

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

5,0E+02 |

7,7E+02 |

|

- |

- |

Table 3.

Summary table of annotations from the different extracts of Salinispora arenicola SH-78.

Table 3.

Summary table of annotations from the different extracts of Salinispora arenicola SH-78.

| Compound ID |

Molecular formula |

Compound name or InChIKey (1,2,3)

|

Precursor ion area observed in MzMine

(with the maximum in bold) according to the culture conditions |

| Solvant |

|

AcOEt |

|

MeOH |

| Support |

|

Solid |

|

Liquid |

|

Solid |

| Days |

|

7 d |

14 d |

21 d |

|

14 d |

|

14 d |

| C78.1 |

C28H26N4O4

|

OH staurosporine (1,2,3)

|

|

|

2,4E+04 |

6,2E+04 |

1,8E+04 |

|

4,5E+03 |

|

1,3E+04 |

| C78.2 |

C28H26N4O3

|

Staurosporine (1,2,3)

|

|

|

2,4E+04 |

1,8E+04 |

7,6E+03 |

|

3,0E+03 |

|

3,2E+03 |

| C78.3 |

C29H28N4O4

|

4'-N-methyl-5'-hydroxy-staurosporine (1)

|

|

|

1,3E+03 |

2,5E+03 |

9,6E+02 |

|

9,9E+02 |

|

4,3E+03 |

| C78.4 |

C28H24N4O5

|

4'-demethyl-Af-formyl-7V-hydroxy-staurosporine (1)

|

|

|

4,0E+02 |

6,5E+02 |

4,5E+02 |

|

- |

|

- |

| C78.5 |

C37H45NO12

|

Rifamycin S (1,2,3)

|

|

|

3,0E+02 |

8,4E+03 |

2,5E+02 |

|

1,6E+04 |

|

2,5E+03 |

| C78.6 |

C36H43NO12

|

16-demethyl rifamycin S (3)

|

|

|

4,5E+02 |

3,5E+03 |

3,0E+02 |

|

3,2E+03 |

|

9,9E+02 |

| C78.7 |

C35H45NO10

|

34a-deoxy-rifamycin W (1)

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

2,0E+03 |

|

- |

| C78.8 |

|

|

4,0E+02 |

1,9E+03 |

3,0E+02 |

|

7,5E+02 |

|

1,0E+02 |

| C78.9 |

C34H41NO10

|

Proansamycin B (1,3)

|

|

|

1,0E+03 |

1,0E+03 |

5,0E+02 |

|

3,0E+02 |

|

- |

| C78.10 |

|

|

3,0E+02 |

1,4E+03 |

1,0E+02 |

|

2,5E+03 |

|

- |

| C78.11 |

C34H41NO11

|

Demethyl-desacetyl-rifamycin S (1)

|

|

|

2,0E+02 |

1,2E+03 |

2,0E+02 |

|

1,2E+04 |

|

5,0E+02 |

| C78.12 |

C37H45NO13

|

20-hydroxyrifamycin S (1,3)

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

1,9E+03 |

|

- |

| C78.13 |

C35H42NO12

|

30-hydroxyrifamycin W (1)

|

|

|

5,0E+01 |

5,6E+02 |

- |

|

7,4E+02 |

|

- |

| C78.14 |

C22H37NO5

|

Saliniketal A (1,3)

|

|

|

1,8E+04 |

3,1E+04 |

2,2E+04 |

|

3,3E+04 |

|

4,6E+03 |

| C78.15 |

C22H37NO6

|

Saliniketal B (1,3)

|

|

|

5,4E+03 |

7,7E+03 |

6,9E+03 |

|

6,6E+03 |

|

7,0E+02 |

| C78.16 |

C8H10O3

|

Salinilactone D (3)

|

|

|

8,0E+02 |

3,5E+02 |

6,0E+02 |

|

4,0E+04 |

|

- |

| C78.17 |

C9H12O3

|

Salinilactone E (3)

|

|

|

- |

6,0E+02 |

- |

|

3,4E+04 |

|

- |

| C78.18 |

|

|

9,0E+03 |

7,6E+03 |

7,3E+03 |

|

1,1E+05 |

|

2,0E+02 |

| C78.19 |

C10H14O3

|

Salinilactone A (3)

|

|

|

3,0E+02 |

3,0E+02 |

3,0E+02 |

|

7,0E+03 |

|

- |

| C78.20 |

|

|

4,0E+02 |

4,0E+02 |

4,0E+02 |

|

8,6E+03 |

|

- |

| C78.21 |

|

|

4,0E+02 |

4,0E+02 |

4,0E+02 |

|

1,0E+04 |

|

- |

| C78.22 |

C11H16O3

|

Salinilactone C (3)

|

|

|

3,0E+03 |

3,7E+03 |

2,5E+03 |

|

1,4E+04 |

|

- |

| C78.23 |

C12H18O3

|

Salinilactone H (3)

|

|

|

1,0E+03 |

2,0E+03 |

8,0E+02 |

|

1,5E+04 |

|

- |

Table 4.

: Microbial strains isolated from Scopalina hapalia ML-263 selected for the study.

Table 4.

: Microbial strains isolated from Scopalina hapalia ML-263 selected for the study.

| Class |

Species |

Code strain |

Selected Regions for

Genetic Characterization |

| Actinobacteria |

Micromonospora sp. |

SH-82 |

ADNr 16s (from V1 to V5) |

|

Micromonospora sp. |

SH-57 |

| Salinispora arenicola |

SH-78 |

Table 5.

: Culture parameters studied for the microbial strains cultures (Micromonospora sp. SH-82, Micromonospora sp. SH-57 and Salinispora arenicola SH-78).

Table 5.

: Culture parameters studied for the microbial strains cultures (Micromonospora sp. SH-82, Micromonospora sp. SH-57 and Salinispora arenicola SH-78).

| Microbial strains |

Days |

Support |

Culture Medium |

|

Micromonospora sp. SH-82 Micromonospora sp. SH-57 |

7/14/21 |

Solid/Liquid |

A1BFe+C |

| 14 |

MB |

|

Salinispora arenicola SH-78 |

7/14/21 |

Solid |

A1BFe+C |

| 14 |

Liquid |