Submitted:

06 April 2023

Posted:

07 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

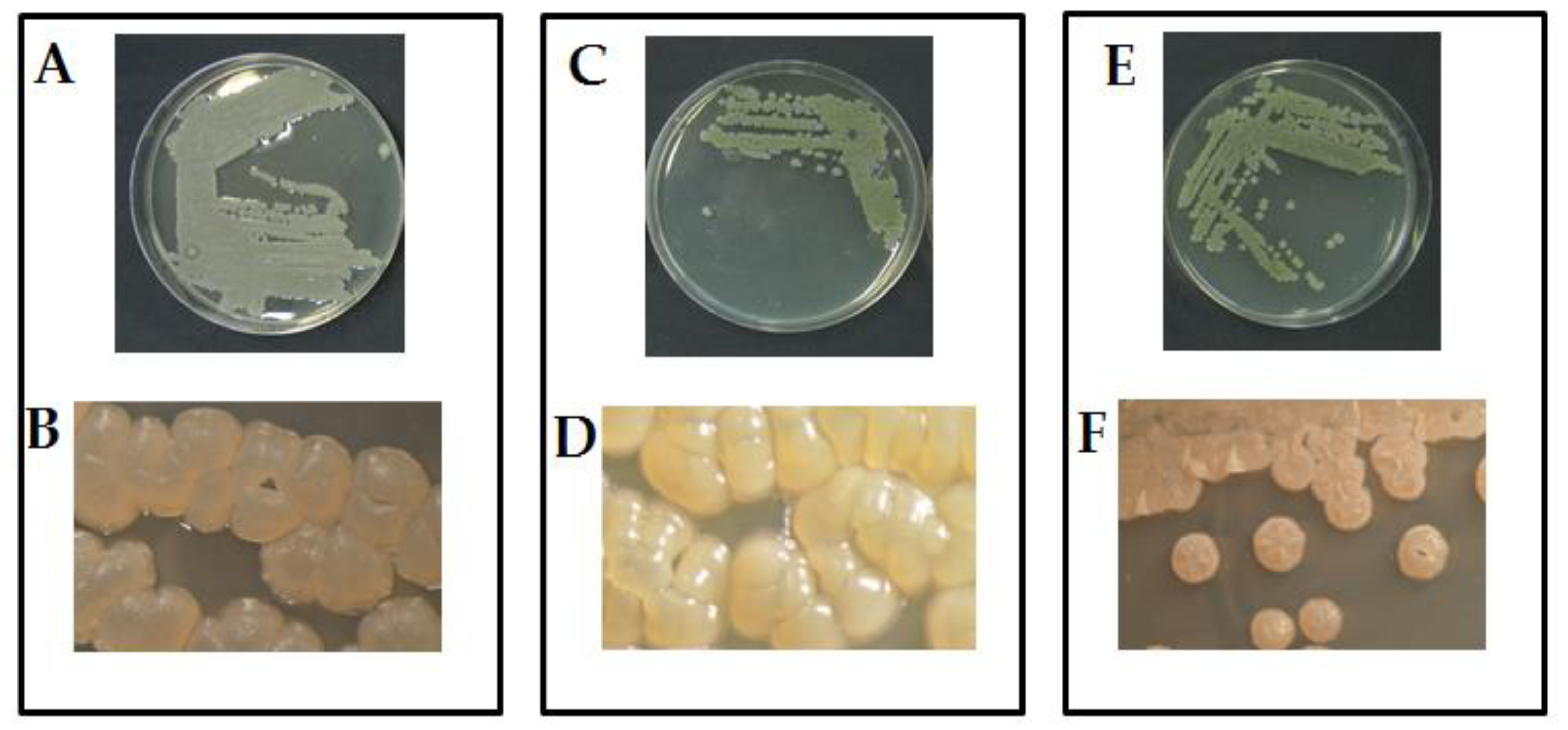

2.1. Actinomycetes isolation and indentification

2.2. Growth-promoting and disease-control effects

2.2.1. Eco-physiological characteristics

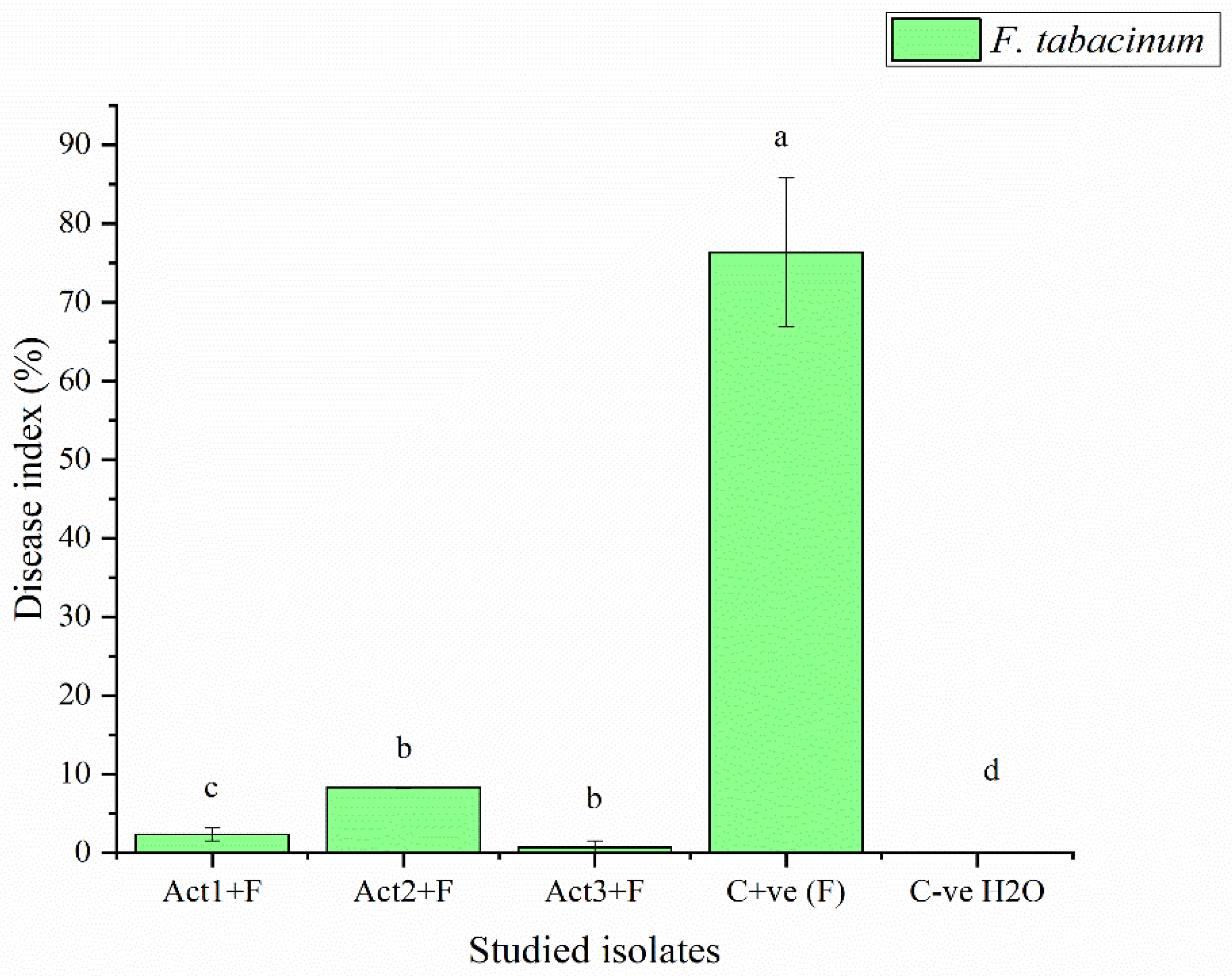

2.2.2. Disease-control effect

2.3. Antimicrobial assay of metabolites

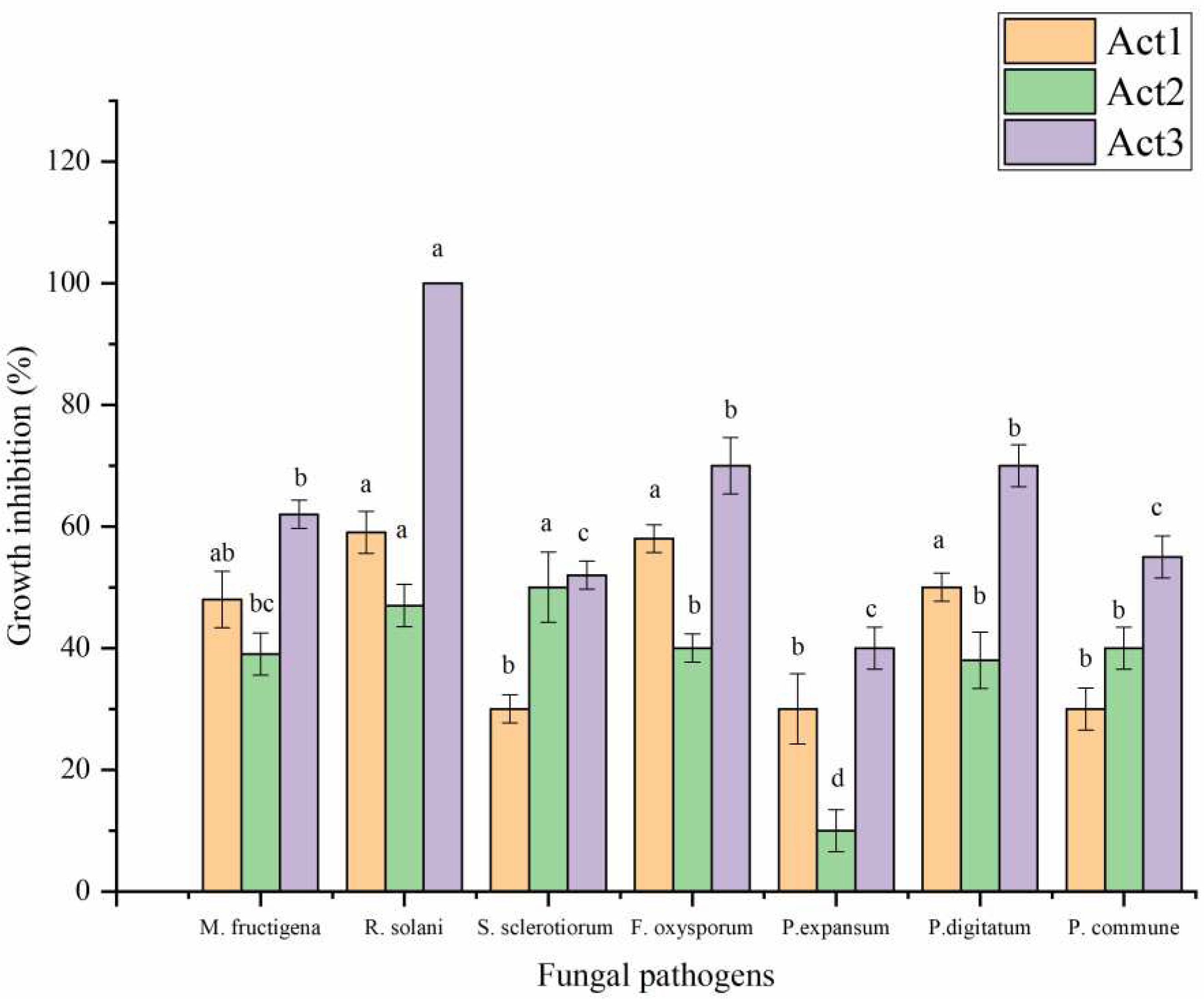

2.3.1. Antifungal activity

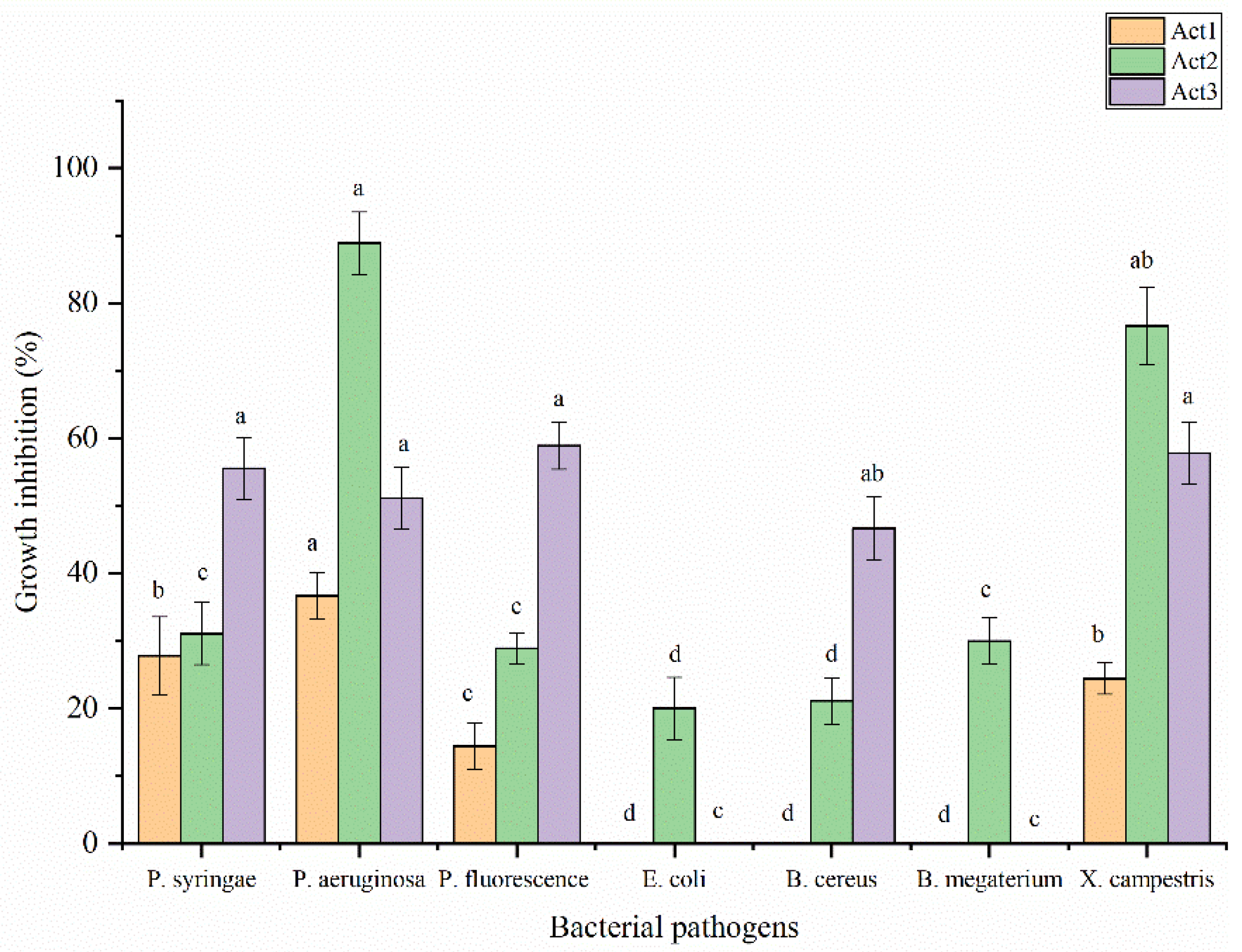

2.3.2. Antibacterial activity

2.4. ESI/(HR)orbitrap/MS metabolic profiles

| No. | Retention time (min) | Measured m/z |

Molecular formula | Identification | Act1 | Act2 | Act3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.87 | 184.1075 | C8H13N3O2 | N-Acetyl-L-histidinol | X | X | |

| 2 | 1.17 | 247.12834 | C10H18N2O5 | N,N′-Diacetyl-2-deoxystreptamine | X | ||

| 3 | 1.18 | 324.16592 | C17H23N3O | Indolactam V | X | ||

| 4 | 1.19 | 155.11748 | C8H14N2O | Hexahydro-2H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(4H)-one | X | ||

| 5 | 2.30 | 275.15955 | C12H22N2O5 | Valyldetoxinine | X | ||

| 6 | 7.11 | 654.2653 | C23H45N5O14 | Paromomycin | X | ||

| 7 | 7.28 | 332.18118 | C12H22N6O4 | Guanidine, N-[3-[5-(2-methylpropyl)-3,6-dioxo-2-piperazinyl]propyl]-N′-nitro-, (2S-cis) | X | X | |

| 8 | 7.73 | 265.16544 | C12H24O6 | n-Hexyl-β-D-glucoside | X | X | |

| 9 | 7.88 | 203.12737 | C10H18O4 | Nonactinic acid | X | ||

| 10 | 8.47 | 247.10730 | C13H14N2O3 | (11aS)-1,2,3,11a-Tetrahydro-8-hydroxy-7-methoxy-5H-pyrrolo[2,1-c][1,4]benzodiazepin-5-one | X | X | |

| 11 | 8.61 | 217.14296 | C11H20O4 | Homononactinic acid | X | ||

| 12 | 8.81 | 307.16461 | C16H22N2O4 | phthoxazolins B, C and D | X | ||

| 13 | 9.43 | 301.08112 | C15H12 N2O5 | Chandrananimycin D | X | ||

| 14 | 9.75 | 299.06592 | C15H10N2O5 | Carboxyexfoliazone | X | ||

| 15 | 10.52 | 283.07053 | C15H10O4N2 | Phencomycin | X | ||

| 16 | 11.32 | 288.2889 | C16H33NO3 | 2-Amino-3-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid | X | ||

| 17 | 11.45 | 269.14923 | C13H20N2O4 | 1,1-Dimethylethyl 2-[2-(ethoxycarbonyl)-1-cyclopenten-1-yl]diazenecarboxylate | X | ||

| 18 | 12.36 | 346.2220 | C17H31O6N | Maoxianamide A or B | X | ||

| 19 | 12.20 | 352.30490 | C11H22N5O6P | Rhizocticin A | X | X | |

| 20 | 14.09 | 399.24997 | C20H34N2O6 | Eponemycin | X | X | X |

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Actinomycetes isolation and indentification

4.2. Plant growth-promoting & disease-control effects

| (1) | |

| (2) | |

| (3) |

4.3. Extraction of metabolites

4.4. Microbicidal test

4.4.1. Antifungal

4.4.2. Antibacterial assay

4.5. ESI/(HR)orbitrap/MS metabolic profiles

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhary, H.S.; Yadav, J.; Shrivastava, A.R.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.K. , Gopalan, N. Antibacterial activity of actinomycetes isolated from different soil samples of Sheopur (A city of central India). J. Adv. Pharma. Technol. Res. 2013, 4, 118–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikineswary, S.; Nadaraj, P.; Wong, W.H.; Balabaskaran, S. . Actinomycetes from a tropical mangrove ecosystem – antifungal activity of selected strains. Asia Pac. J. Mol. Biol. Biotechnol. 1997, 5, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, L.S.H.; Norzaimawati, A.N.; Rosnah, H. Prescreening of bioactivities from actinomycetes isolated from forest peat soil in Sarawak. J. Trp. Agric. Fd. Sci. 2011, 39, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Manivasagan, P.; Kang, K.-H.; Sivakumar, K.; Li-Chan, E.C.; Oh, H.M.; Kim, S.K. Marine actinobacteria: an important source of bioactive natural products. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 38, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, I.L.; Gentry, T.J. Chapter 4 – “Earth Environments” in: Environmental Microbiology (Third Edition) – 2015 pp. 59-88.

- Holt, J.G.; Krieg, N.R.; Sneath, P.H.A.; Staley, J.T.; Williams, S.T. Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology (9th ed). Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore. 1994.

- Berdy, J. . Bioactive microbial metabolites. J. 2005Antibiotics 58, 1.

- Girão, M.; Ribeiro, I.; Ribeiro, T.; Azevedo, I.C.; Pereira, F.; Urbatzka, R.; Leão, P.N.; Carvalho, M.F. Actinobacteria Isolated from Laminaria ochroleuca: A Source of New Bioactive Compounds. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 683, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.E. Basil. Center for New Crops & Plant Products, Department of Horticulture, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN. 1998.

- Garibaldi, A.; Minuto, A.; Minuto, G.; Gullino, M.L. First Report of Downy Mildew on Basil (Ocimum basilicum) in Italy. Plant Dis. 2004, 88, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, A. Fusarium tabacinum (Beyma) W. Gams patogeno in natura su basilico e pomodoro. Rivista di Patologia Vegetale, S. 1978, IV, 14, 119-125.

- Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I. Rhizospheric actinomycetes revealed antifungal and plant-growth-promoting activities under controlled environment. Plants 2022, 11, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballio, A.; Russi, S.; Vlasić, D. Isolation and identification of N-acetyl-L-histidinol in cultures of mutants of Streptomyces coelicolor requiring histidine. Annali Dell'istituto Superiore di Sanita 1966, 2(4), 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, SJ. Frequency of resistance to kanamycin, tobramycin, netilmicin, and amikacin in gentamicinresistant gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978, Jan;13(1):70-3. PMID: 626492; PMCID: PMC352186. [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Takahiro, M.; Iori, M.; Hitomi, N.; Miroslava, A.; Shotaro, H.; Takayoshi, A.; Ikuro, A. Molecular basis for the P450-catalyzed C-N bond formation in indolactam biosynthesis. Nature Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithya, K.; Muthukumar, C.; Biswas, B.; Alharbi, N.S.; Kadaikunn, S.; Khaled, J.M.; Dhanasekaran, D. Desert actinobacteria as a source of bioactive compounds production with a special emphasis on Pyridine-2,5-diacetamide a new pyridine alkaloid produced by Streptomyces sp. DA3-7. Microbiol. Res 2018, 207, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.R.; Han, S.Y.; Joullie, M.M. Total synthesis of (+)-valyldetoxinine and (-)-detoxin D1. Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Housseiny, G.S.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Yassien, M.A.; Aboshanab, K.M. Production and statistical optimization Paromomycin by Streptomyces rimosusNRRL 2455 in solid state fermentation. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, R.M.; Kogan, H.V.; Elikan, A.B.; Snow, J.W. Paromomycin Reduces Vairimorpha (Nosema) ceranae Infection in Honey Bees but Perturbs Microbiome Levels and Midgut Cell Function. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.; Akutagawa, T.; Funatani, H.; Uchida, T.; Hotta, Y.; Niwa, M.; Takaya, Y. Cyclic dipeptides exhibit potency for scavenging radicals. Bioorganic & Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 2002–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, G.; Berube, C.; Voyer, N.; Grenier, D. Anti-biofilm and anti-adherence properties of novel cyclic dipeptides against oral pathogens. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chem. 2019, 27, 2323–2331. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuta, K.; Tsuchiya, T.; Umezawa, S.; Naganawa, H.; Umezawa, H. Revised structure for arglecin. J. Antibiotics 1972, 25, 674–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ryan, B.; Henehan, G.T.M. b-Glucosidase from Streptomyces griseus: Nanoparticle immobilization and application to alkyl glucoside synthesis. Protein Exp. Purif. 2017, 132, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Hu, J.; Xie, X.; Zhou, R.; Li, F.; Huang, R.; He, J. Secondary Metabolites with Cytotoxic Activities from Streptomyces sp. BM-8 Isolated from the Feces of Equusquagga. Molecules 2021, 26, 24–7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chen, Y.K.; Wang, J.J.; Hsu, C.C.; Tsai, F.Y.; Sung, P.J.; Lin, H.C.; Chang, L.S.; Hu, W.P. DC-81-enediyne induces apoptosis of human melanoma A375 cells: involvement of the ROS, p38 MAPK, and AP-1 signaling pathways. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2013, 29, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiomi, K.; Arai, N.; Shinose, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Iwabuchi, J.; Tanaka, Y.; Omura, S. New antibiotics phthoxazolins B, C and D produced by Streptomyces sp. KO-7888. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48(7), 714–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.B. : Nett, M.; Dahse, H.M.; Hertweck, C.P. Structural merger of a phenoxazinone with an epoxyquinone antibiotic. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1461–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, M.S. A new bioactive aminophenoxazinone alkaloid from a marine-derived actinomycete. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 2126–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Vijayakumar, E.K.; Franco, C.M.; Maurya, R.; Blumbach, J.; Ganguli, B.N. Phencomycin, a new antibiotic from a Streptomyces species HIL Y-9031725. J. Antibiot. 1995, 8(11), 1353-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidetsugu, N.; Hitoshi, E.; Koji, K.; Okumura, K. Biological method of producing serine and serinol derivatives. U.S. Patent No 3871958A. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. 1975.

- Li, J.M.; Yan, K.; Zhang, H.; Qi, H.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, W.S.; Wang, J.D.; Wang, X.J. New aliphatic acid amides from Streptomyces maoxianensis sp. nov. J. Antibiotics 2017, 70, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahungu, M.; Arguelles-Arias, A.; Fickers, P.; Zervosen, A.; Joris, B.; Damblon, C.; Luxen, A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of potential threonine synthase inhibitors: Rhizocticin A and Plumbemycin A. Bioorganic & Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 4958–4967. [Google Scholar]

- Fredenhagen, A.; Angst, C.; Peter, H.H. Digestion of rhizocticins to (Z)-L-2-amino-5-phosphono-3-pentenoic acid: revision of the absolute configuration of plumbemycins A and B. J. Antibiotics 1995, 48, 1043–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara; K. ; Hatori M.; Nishiyama, Y.; Tomita, K.; Kamei, H.; Konishi, M., Oki, T. Eponemycin, a new antibiotic active against B16 melanoma. I. Production, isolation, structure and biological activity. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 1990, 43(1), 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fitri, L.E.; Cahyono, A.W.; Nugraha, R.Y.B.; Alkarimah, A.; Ramadhani, N.N.; Laksmi, D.A.; Trianty, L.; Noviyanti, R. Analysis of eponemycin (α'β' epoxyketone) analog compound from Streptomyces hygroscopicus subsp Hygroscopicus extracts and its antiplasmodial activity during Plasmodium berghei infection. Biomed. Res. 2017, 28, 164–172. [Google Scholar]

- Suwan, N.; Wassamon, B.; Sarunya, N. Antifungal activity of soil actinomycetes to control chilli anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. J. Agric. Technol. 2012, 8, 725–737. [Google Scholar]

- Sacramento, D.R.; Coelho, R.R.R.; Wigg, M.D.; Wigg, M.D. , Linhares, L.F.T.; Santos, M.G.M.; Semêdo, L.T.A.; Silva, A.J.R. Antimicrobial and antiviral activities of an actinomycete (Streptomyces sp.) isolated from a Brazilian tropical forest soil. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 20, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prapangdee, B.; Kuekulvong, C.; Mongkolsuk, S. Antifungal Potential of Extracellular Metabolites Produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus against Phytopathogenic Fungi. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2008, 4, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solans, M.; Vobis, G.; Cassa´n, F.; Luna, V.; Wall, L.G. Production of phytohormones by root-associated saprophytic actinomycetes isolated from the actinorhizal plant Ochetophila trinervis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 2195–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odumosu, B.T.; Buraimoh, O.M.; Okeke, C.J.; Ogah, J.O.; Michel, Jr. F.C. ; Antimicrobial activities of the Streptomyces ceolicolor strain AOBKF977550 isolated from a tropical estuary. J. Taibah Univer. Sci. 2017, 11, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacret, R. , Oves-Costales, D.; Gómez, C.; Díaz, C.; de la Cruz, M.; Pérez-Victoria, I.; Vicente, F.; Genilloud, O.; Reyes, F. New ikarugamycin derivatives with antifungal and antibacterial properties from Streptomyces zhaozhouensis. Mar. Drugs 2014, 13, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Tian, Z.H.; Xie, W.D. Viridobrunnines A B, antimicrobial phenoxazinone alkaloids from a soil associated Streptomyces sp. Heterocycles 2015, 91(9), 1809–1814. [Google Scholar]

- Ogita, T.; Seto, H.; Ōtake, N.; Yonehara, H. The Structures of Minor Congeners of the Detoxin Complex. Agricul. Biol. Chem. 1981, 45, 2605–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Lee, S.W. , Balaraju, K.; Kim, C.J.; Park, K. Chili - Pepper Protection from Phytophthora capsici and Pectobacterium carotovorum SCC1 by Encapsulated Paromomycin Derived from Streptomyces sp. AMG-P1. J. Pure & Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 6, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Jizba, J.; Pfukrylova, V.; Ujhelyova, L.; Varkonda, S. Insecticidal properties of nonactic acid and homononactic acid, the precursors of macrotetrolide antibiotics. Folia Microbiol. 1992, 37, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizba, J.; Skibova, I. Regulation of biosynthesis of pesticidal metabolic complexes in Streptomyces griseus. Folia Microbiologica 1994, 39, 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, M.; Loeffler, W.; Rapp, C.; Kern, A.; Jung, G. Rhizocticin A, an antifungal phosphono-oligopeptide of Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633: biological properties. Arch Microbiol. 1990, 153(3), 276–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njenga, W.P.; Mwaura, F.B.; Wagacha, J.M.; Gathuru, E.M. Methods of Isolating Actinomycetes from the Soils of Menengai Crater in Kenya. Arch Clin Microbiol. 2017, 8, 3:45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Sakr, S.; Bufo, S.A.; Camele, I. An attempt of biocontrol the tomato-wilt disease caused by Verticillium dahliae using Burkholderia gladioli pv. agaricicola and its bioactive secondary metabolites. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2017, 8, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.J.; Kamala-Kannan, S.; Sub, H.S.; Seong, C.K.; Lee, G.W. World J. Microbiol. Biotecnol. 2008, 24, 1139–1145. [CrossRef]

- Lavermicocca, P.; Iacobellis, N.S.; Simmaco, M.; Graniti, A. Biological properties and spectrum of activity of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae toxins. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1997, 50, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Viggiani, L.; Mostafa, M.S.; El-Hashash, M.A.; Bufo, S.A.; Camele, I. Biological activity and chemical identification of ornithine lipid produced by Burkholderia gladioli pv. agaricicola ICMP 11096 using LC-MS and NMR analyses. J. Biol. Res. 2017, 90, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Amato, M.; De Feo, V.; Camele, I. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Chia (Salvia hispanica l.) Essential oil. Europ. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Gruľová, D.; Baranová, B.; Caputo, L.; De Martino, L.; Sedlák, V.; Camele, I.; De Feo, V. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of essential oil extracted from Solidago canadensis L. growing wild in Slovakia. Molecules 2019, 24, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S. Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA)- Principle, Uses, Composition, Procedure and Colony Characteristics. Microbiol. Info. Com. 2018.

- Zygadlo, J.A.; Guzman, C.A.; Grosso, N.R. Antifungal properties of the leaf oils of Tagetes minuta L. and Tagetes filifolia Lag. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1994, 6, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, A.; Johnson, M.C. , Ray, B. Purification, characterization and antimicrobial spectrum of a bacteriocin produced by Pediococcus acidilactici. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1988, 65, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camele, I.; Elshafie, H.S.; Caputo, L.; Sakr, S.H.; De Feo, V. Bacillus mojavensis: Biofilm formation and biochemical investigation of its bioactive metabolites. J. Biol. Res. 2019, 92, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruľová, D.; Caputo, L.; Elshafie, H.S.; Baranová, B.; De Martino, L.; Sedlák, V.; Camele, I.; De Feo, V. Thymol chemotype Origanum vulgare L. essential oil as a potential selective bio-based herbicide on monocot plant species. Molecules 2020, 25(3), 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E.O.; Ward, M.K.; Raney, D.E. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1954, 44, 301–307. [Google Scholar]

| Actinomycetes isolates |

Eco-Physiological Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL (n) | NT (n) | SL (cm) | TFwS (g) | TDwS (g) | |

| Control | 89±4b | 8±2a | 27±2b | 85±12b | 5±2c |

| Act1: Streptomyces sp. | 113±12a | 4±2b | 39±4a | 114±15a | 23±2a |

| Act2: A. humicola | 105±5a | 7±1a | 41±6a | 99±9b | 18±6a |

| Act3: S. atratus | 85±7b | 3±1b | 27±2b | 111±27a | 14±2b |

| Actinomycetes isolates |

Eco-Physiological Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL (n) | NT (n) | SL (cm) | TFwS (g) | TDwS (g) | |

| Cont -ve | 85±9c | 2±1ab | 34±4b | 75±4c | 15±2b |

| Act1: Streptomyces sp. | 146±7a | 7±1a | 45±5a | 241±13a | 40±4a |

| Act2: A. humicola | 111±10b | 5±1a | 47±3a | 246±7a | 31±4ab |

| Act3: S. atratus | 109±9b | 3±1ab | 34±4b | 191±5b | 20±3b |

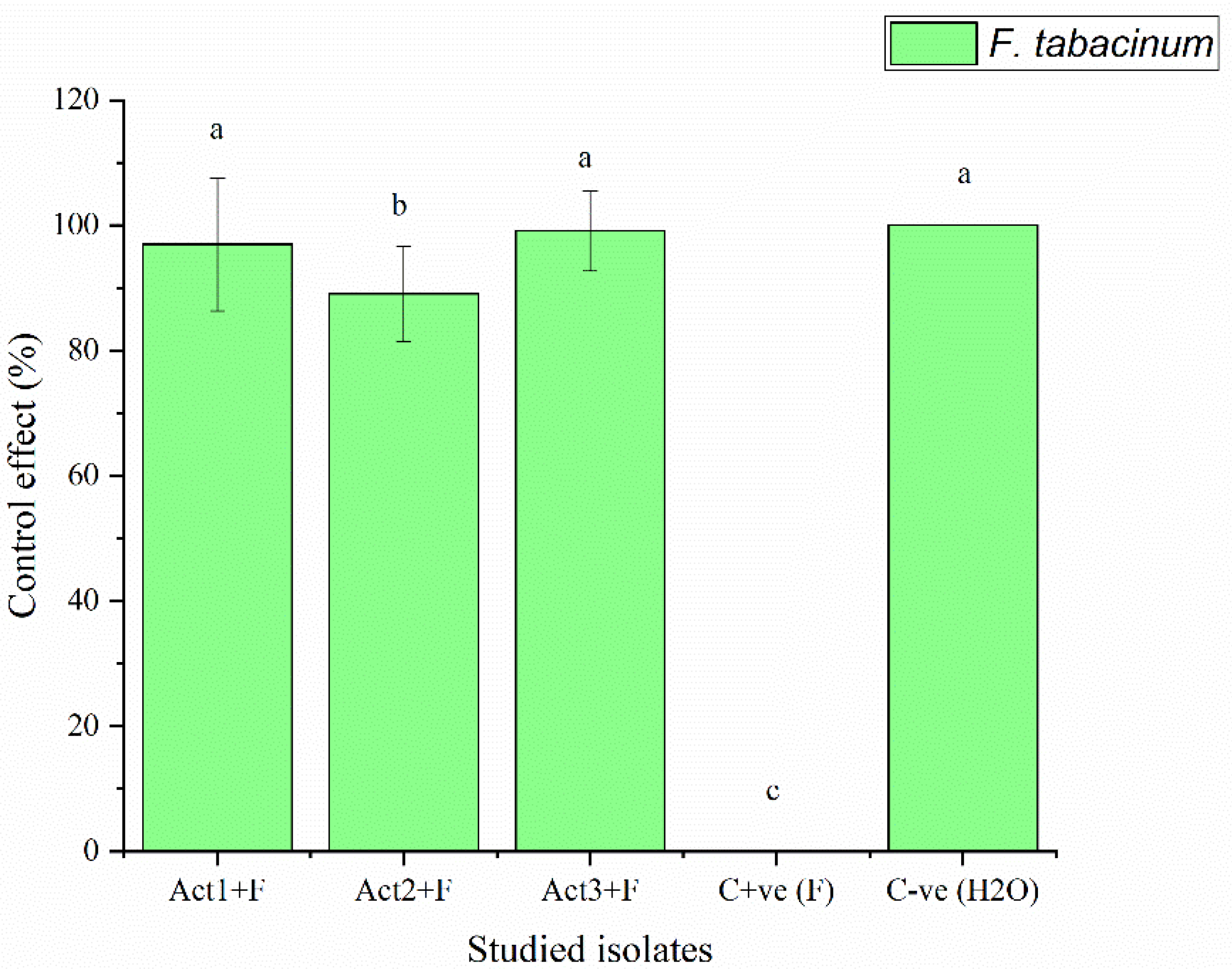

| Treatments | Disease-index | Control-effect |

|---|---|---|

| DI % | CE % | |

| Act1: Streptomyces sp. | 2.3±0.8c | 96.9±10.6a |

| Act2: A. humicola | 0.7±0.1d | 99.1±7.6a |

| Act3: S. atratus | 8.3±0.9b | 89.1±6.4ab |

| Cont. +ve (F) | 76.4±9.5a | 0.0±0.0c |

| Cont. -ve (H2O) | 0.0±0.0e | 100.0±0.0a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).