Submitted:

29 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Molecular identification of the studied isolates of Beauveria

2.2. Antagonistic activity of B. bassiana isolates

2.3. Antimicrobial activity of Exo- and Endo- diffusible metabolites

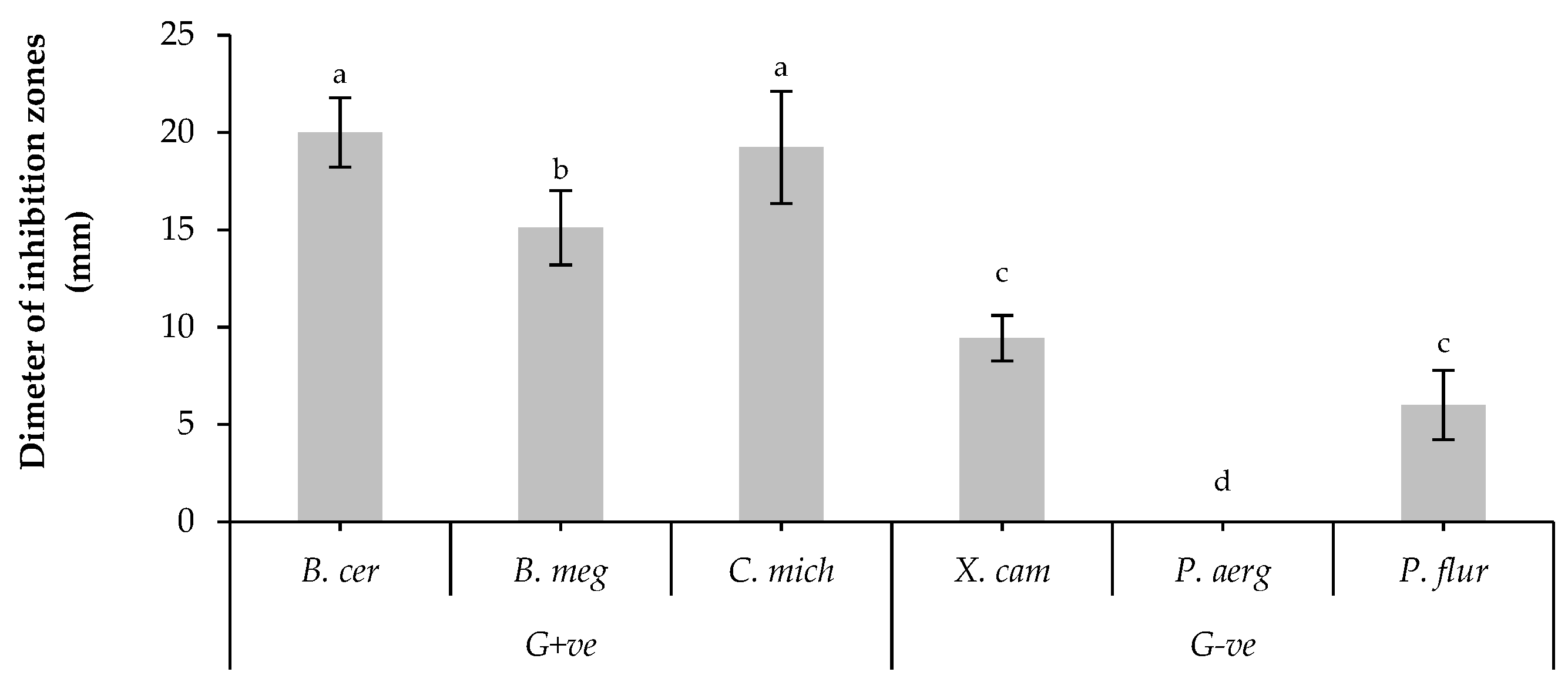

2.4. Antibacterial activity of volatiles metabolites

2.5. SPME-GC/MS analysis of VOCs

| RT (min) |

Area (%) |

Name | M.Wt (g/mol) |

Formula | CAS | Probability of identification (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.576 | 4.69 | Ethanol | 46,07 | C2H5OH | 000064-17-5 | 90 |

| 2.834 | 0.44 | Butanal, 2-methyl | 86 | C5H10O | 000096-17-3 | 90 |

| 5.372 | 00.63 | 2,4-Dimethyl-1-heptene | 126.24 | C9H18 | 019549-87-2 | 90 |

| 5.660 | 1.99 | Octane, 4-methyl | 128.25 | C9H20 | 002216-34-4 | 93 |

| 10.459 | 6.98 | β-elemenea | 204.35 | C15H24 | 000515-13-9 | 96 |

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation, culturing and identification

4.2. Antagonistic activity

| Bacteria name | Author | Collection number | Gram type |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. cereus | Frankland & Frankland | UniB12421 | G+ve |

| B. megaterium | de Bary | UniB12421 | |

| C. michiganensis | (Smith) Davis | UniB3718 | |

| X. campestris | (Pammel) Dowson | UniB7718 | G-ve |

| P. aeruginosa | (Schröter) Migula | UniB02421 | |

| P. fluorescens | (Flügge) Migula | UniB05421 |

4.3. Extraction of secondary metabolites

4.4. Antibacterial activity of diffusible metabolites

4.5. Antibacterial activity of volatiles metabolites

4.6. SPME-GC/MS of VOCs

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vega, F.E.; Goettel, M.S.; Blackwell, M.; Chandler, D.; Jackson, M.A.; Keller, S.; Koike, M.; Maniania, N.K.; Monz´on, A.; Ownley, B.H.; Pell, J.K.; Rangel, D.E.N.; Roy, H.E. Fungal entomopathogens: new insights on their ecology. Fungal Ecol. 2009, 2, 149–159.

- Barbarin, A.M.; Jenkins, N.E.; Rajotte, E.G.; Thomas, M.B. A preliminary evaluation of the potential of Beauveria bassiana for bed bug control. J. Invertebrate Pathol. 2012, 111, 82–85. [CrossRef]

- S.P.Wraight, R.B.Lopes, and M.Faria. Chapter 16: Microbial Control of Mite and Insect Pests of Greenhouse Crops. In: Microbial Control of Insect and Mite Pests, 2017, 237-252.

- Yuan, W.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S. Glycosylation of (–)-maackiain by Beauveria bassiana and Cunninghamella echinulata var. elegans. Biocatal. Biotransformation 2010, 28, 117-121.

- Berestetskiya, A.O.; Ivanovaa, A.N.; Petrovaa, M.O.; Prokof’evab, D.S.; Stepanychevaa, E.A.; Uspanovc, A.M.; Lednev, G R. Comparative analysis of the biological activity and chromatographic profiles of the extracts of Beauveria bassiana and B. pseudobassiana cultures grown on different nutrient substrates. Microbiology 2018, 87, 200–214.

- Begley, C.G.; Waggoner, P. Soft contact lens contamination by Beauveria bassiana. Int. Contact Lens Clinic. 1992, 19, 247‒251. [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.E. The use of fungal entomopathogens as endophytes in biological control: a review. Mycologia 2018, 110, 4–30. [CrossRef]

- Fabrice, D.H.; Elie, D.A.; Kobi, D.O.; Valerien, Z.A.; Thomas, H.A.; Joëlle, T.; Maurille, E.I.A.T.; Dénis, O.B.; Manuele, T. Toward the efficient use of Beauveria bassiana in integrated cotton insect pest management. J. Cotton Res. 2020, 3, 24.

- Wang, Y.; Tang, D.; Duan, D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H. Morphology, molecular characterization, and virulence of Beauveria pseudobassiana isolated from different hosts. J. Inverteb. Pathol. 2020, 72, 107333. [CrossRef]

- Sinno, M.; Ranesi, M.; Di Lelio, I.; Iacomino, G.; Becchimanzi, A.; Barra, E.; Molisso, D.; Pennacchio, F.; Digilio, M.C.; Vitale, S.; et al. Selection of endophytic Beauveria bassiana as a dual biocontrol agent of tomato pathogens and pests. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1242. [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.R.; Wraight, S.P. Biological control of Bemisia tabaci with fungi. Crop Prot. 2001, 20, 767–778. [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.R.; Wraight, S.P. Mycoinsecticides and mycoacaricides: a comprehensive list with worldwide coverage and international classification of formulation types. Biol. Control 2007, 43, 237–256.

- Fargues, J.; Remaudiere, G. Consideration on the specificity of entomopathogenic fungi. Mycopathologia 1977, 62, 31–37. [CrossRef]

- Hasaballah, A.I.; Fouda, M.A.; Hassan, M.I.; Omar, G.M. Pathogenicity of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae on the adult housefly, Musca domestica L. Egypt. Acad. J. Biolog. Sci. (A. Entomology) 2017, 10, 79- 86. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N.; Rajotte, E.G.; Jenkins, N.E.; Thomas, M.B. Potential for biocontrol of house flies, Musca domestica, using fungal biopesticides. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 513-524. [CrossRef]

- Barra-Bucarei, L.; Iglesias, A.F.; González, M.G.; Aguayo, G.S.; Carrasco-Fernández, J.; Castro, J.F.; Campos, J.O. Antifungal activity of Beauveria bassiana Endophyte against Botrytis cinerea in Two Solanaceae Crops. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 65. [CrossRef]

- Parine, N.R.; Pathan, A.K.; Sarayu, B.; Nishanth, V.S.; Bobbarala, V. Antibacterial e_cacy of secondary metabolites from entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana. Int. J. Chem. Anal. Sci. 2010, 1, 94–96.

- Ownley, B.H.; Bishop, D.G.; Pereira, R.M. Biocontrol of Rhizoctonia damping off of tomato with Beauveria bassiana. Phytopathol. 2000, 90, S58.

- Della Pepa, T.; Elshafie, H.S.; Capasso, R.; De Feo, V.; Camele, I.; Nazzaro, F.; Scognamiglio, M.R.; Caputo, L. Antimicrobial and phytotoxic activity of Origanum heracleoticum and O. majorana essential oils growing in Cilento (Southern Italy). Molecules 2019, 24, 2576.

- Gruľová, D., Caputo, L., Elshafie, H. S., Baranová, B., De Martino, L., Sedlák, V., Camele I.; De Feo, V. Thymol chemotype Origanum vulgare L. essential oil as a potential selective bio-based herbicide on monocot plant species. Molecules 2020, 25, 595. [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu, M. U., Okoye, R.C. Antimicrobial Activity of Nigerian Medicinal Plants. J. Intercult Ethnopharmacol 2017, 6, 240–259.

- Keifer, M.C.; Firestone, J. Neurotoxicity of pesticides. J. Agromed. 2007, 12, 17–25. [CrossRef]

- Camele I., Elshafie H.S., Caputo L., Sakr S.H., De Feo V. Bacillus mojavensis: Biofilm formation and biochemical investigation of its bioactive metabolites. J. Biol. Res. 2019, 92, 39-45. [CrossRef]

- Wang H., Peng H., Li W., Cheng P., Gong M. The toxins of Beauveria bassiana and the strategies to improve their virulence to insects. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 705343.

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 1; 25, 3389-3402. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ye, W., Qi, Y., Ying, Y.; Xia, Z. Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Bacteria Through Antibiotics Delivery in Surface-Engineered Nano-Cargos: Recent Developments for Future Nano-Antibiotics. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 696514. [CrossRef]

- Soothill, G.; Hu, Y.; Coates, A. Can we prevent antimicrobial resistance by csing antimicrobials better?. Pathogens 2013, 2, 422–435.

- Zimmermann, G. Review on safety of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Beauveria brongniartii. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2007, 17, 553–596.

- Chen, W.H., Liu, M., Huang, Z.X., Yang, G.M., Han, Y.F., Liang, J.D., Liang, Z.Q. Beauveria majiangensis, a new entomopathogenic fungus from Guizhou, China. Phytotaxa 2018, 333, 243–250. [CrossRef]

- Ownley, B.H.; Pereira, R.M.; Klingeman,W.E.; Quigley, N.B.; Leckie, B.M. Beauveria bassiana, a dual purpose biological control with activity against insect pests and plant pathogens. Emerg. Concepts Plant Health Manag. 2004, 2004, 255–269.

- Suzuki, A.; Kanaoka, M.; Isogai, A.; Tamura, S.; Murakoshi, S.; Ichinoe, M. Bassianolide, a new insecticidal cyclodepsipeptide from Beauveria bassiana and Verticillium lecanii. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977, 18, 2167–2170. [CrossRef]

- Wang S., Zhao Z., Yun-Ting S., Zeng Z., Zhan X., Li C., Xie T. A review of medicinal plant species with elemene in China. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 6, 3032–3040.

- El Kichaoui, A.; Elnabris, K.; Shafie, A.; Fayyad, N.; Arafa, M.; El Hindi, M. Development of Beauveria bassiana based bio-fungicide against Fusarium wilt pathogens for Capsicum annuum. IUG J. Nat. Stud. 2017, 183-190.

- Vining, L.C.; Kelleher, W.J.; Schwarting, A.E. Oosporein production by a strain of Beauveria bassiana originally identified as Amanita muscaria. Can. J. Microbiol. 1962, 8, 931–933. [CrossRef]

- Hamill, R.L.; Higgens, C.E.; Boaz, H.E.; Gorman, M. The structure of beauvericin, a new depsipeptide antibiotic toxic to Artemia salina. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 10, 4255–4258.

- Zimmermann, G. Review on safety of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Beauveria brongniartii. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2007, 17, 553-596.

- Logrieco, A.; Moretti, A.; Castella, G.; Kostecki, M.; Golinski, P.; Ritieni, A.; Chelkowski, J. Beauvericin production by Fusarium species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 3084–3088. [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, T.; Nakata, K.; Kouno, K. Antifungal activity of oosporein from an antagonistic fungus against Phytophthora infestans. Z. Naturforschung C 2004, 59, 302–304. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, L. Beauvericin, a bioactive compound produced by fungi: A short review. Molecules 2012, 17, 2367–2377. [CrossRef]

- Manning, R.O.; Wyatt, R.D. Comparative toxicity of Chaetomium contaminated corn and various chemical forms of oosporein in broiler chicks. Poultry Sci. 1984, 63, 251-259. [CrossRef]

- Golembiovska, O.; Tsurkan, A.; Vynogradov, B. Components of Prunella vulgaris L. Grown in Ukraine J. Pharmacognosy Phytochem. 2014, 2, 140-146.

- Bernotienë, G.; Nivinskienë O.; Butkienë, R.; Mockutë, D. Chemical composition of essential oils of hops (Humulus lupulus L.) growing wild in Aukštaitija. Chemija 2004, 15, 31-36.

- Fischedick, J.T.; Hazekamp, A.; Erkelens, T.; Choi, Y.H.; Verpoorte, R. Metabolic fingerprinting of Cannabis sativa L., cannabinoids and terpenoids for chemotaxonomic and drug standardization purposes. Phytochem. 2010, 71, 2058-2073. [CrossRef]

- Sieniawska, E.; Sawicki, R.; Golus, J.; Swatko-Ossor, M.; Ginalska, G.; Skalicka-Wozniak, K. Nigella damascena L. essential Oil—a valuable source of β-Elemene for antimicrobial testing. Molecules 2018, 23, 256. [CrossRef]

- Mendanha, S.A.; Alonso, A. Effects of terpenes on fluidity and lipid extraction in phospholipid membranes. Biophys. Chem. 2015, 198, 45–54. [CrossRef]

- Barrero, A.F.; Quilez del Moral, J.F.; Lara, A.; Herrador, M.M. Antimicrobial activity of sesquiterpenes from the essential oil of Juniperus thurifera Wood. Planta Med. 2005, 71, 67–71. [CrossRef]

- Drage, S.; Mitter, B.; Tröls, C.; Muchugi, A.; Jamnadass, R.H.; Sessitsch, A.; Hadacek, F. Antimicrobial drimane sesquiterpenes and their effect on endophyte communities in the medical tree Warburgiau gandensis. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 13.

- Monga A.; Sharma A. 2020. Chapter 9 - Natural products encompassing antituberculosis activities. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. 2020, 64, 263-301.

- Zhai, B.; Zhang, N.; Han, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, R.; Chen, P.; Wang, W.; Li, C.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, S.; Duan, T.; Lou, J.; Xie, T.; Sui, X. Molecular targets of β-elemene, a herbal extract used in traditional Chinese medicine, and its potential role in cancer therapy: A review. Biomed. Pharmacoth. 2019, 14, 108812. [CrossRef]

- T. Dong, Y. Yan, H. Chai, S. Chen, X. Xiong, D. Sun, Y. Yu, L. Deng, F. Cheng, Pyruvate kinase M2 affects liver cancer cell behavior through up-regulation of HIF-1α and Bcl-xL in culture. Biomed. Pharmacother. 69 (2015) 277–284.

- van Niekerk, G.; Engelbrecht, A.M. Role of PKM2 in directing the metabolic fate of glucose in cancer: a potential therapeutic target, Cell Oncol. (Dordr.) 2018, 41, 343–351.

- Sun, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xie, Z.; Lei, X.; Tang, G. Discovery and development of tumor glycolysis rate-limiting enzyme inhibitors. Bioorganic Chem. 2021, 112, 104891. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, W.; Huang, S.; Ni, W.; Wei, Z.; Cao, Y.; Yu, S.; Jia, Q.; Wu, Y.; Chai, C.; Zheng, Q., Zhang, L.; Wang, A., Sun, Z.; Huang, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Lu, Y. Beta-elemene inhibits breast cancer metastasis through blocking pyruvate kinase M2 dimerization and nuclear translocation. J. Cell Mol. Med., 2019, 23, 6846–6858. [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.M.; White, R.L.; Pereira, R.M.; Geden, C.J. Beauveria bassiana culturing and harvesting for bioassays with house flies. J. Insect Sci. 2020, ,, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Racioppi, R.; Bufo, S.A.; Camele, I. In vitro study of biological activity of four strains of Burkholderia gladioli pv. agaricicola and identification of their bioactive metabolites using GC–MS. Saudia J. Biol Sci. 2017, 24, 295–301. [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Viggiani, L.; Mostafa, M.S.; El-Hashash, M.A.; Bufo, S.A.; Camele; I. Biological activity and chemical identification of ornithine lipid produced by Burkholderia gladioli pv. agaricicola ICMP 11096 using LC-MS and NMR analyses. J. Biol. Res. 2017, 90, 96-103. [CrossRef]

- Sofo, A.; Elshafie, H.S.; Scopa, A.; Mang, S.M.; Camele, I. Impact of airborne zinc pollution on the antimicrobial activity of olive oil and the microbial metabolic profiles of Zn-contaminated soils in an Italian olive orchard. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2018, 49, 276–284. [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.G.; Li, G.Q.; Zhang, J.B.; Jiang, D.H.; Huang, H.C. Effect of volatile substances of Streptomyces platensis F-1 on control of plant fungal diseases. Biol. Cont. 2008, 46, 552–559.

- Camele, I.; Grul’ová, D.; Elshafie, H.S. Chemical composition and antimicrobial properties of Mentha _ piperita cv. ‘Kristinka’ essential oil. Plants 2021, 10, 1567.

- Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I.; Racioppi, R.; Scrano, L.; Iacobellis, N.S.; Bufo, S.A. In vitro antifungal activity of Burkholderia gladioli pv. agaricicola against some Phytopathogenic fungi. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 16291-16302.

| Tested bacteria | Diameter of inhibition zones (mm) | |||

|

Exo-ME 16 mg/mL |

Endo-ME 20 mg/mL |

Tetracycline 1600 µg/mL |

||

| G+ve | B. cereus | 8.5±1.0ab | 0.0±0.0c | 20.8±1.1b |

| B. megaterium | 10.0±1.9ab | 4.0±1.7b | 25.9±2.3ab | |

| C. michiganensis | 12.5±2.2a | 0.0±0.0c | 39.5±2.5a | |

| G-ve | X. campestris | 9.5±2.5ab | 9.0±1.9a | 23.5±1.7ab |

| P. aeruginosa | 0.0±0.0c | 6.5±2.8ab | 10.6±0.7c | |

| P. fluorescens | 6.5±1.5b | 4.5±1.7b | 12.3±0.9c | |

| Tested bacteria | Bacterial growth inhibition (%) | |||

| GVC | AQS |

Tetracycline 1600 µg/mL |

||

| G+ve | B. cereus | 35.0±5.8c | 60.0±5.8c | 20.8±1.1b |

| B. megaterium | 77.5±2.9a | 92.0±3.5a | 25.9±2.3ab | |

| C. michiganensis | 55.0±5.8b | 77.5±2.9b | 39.5±2.5a | |

| G-ve | X. campestris | 27.5±2.9d | 77.5±8.7b | 23.5±1.7ab |

| P. aeruginosa | 37.5±2.9c | 87.5±2.9a | 10.6±0.7c | |

| P. fluorescens | 52.5±2.9b | 72.5±2.9b | 12.3±0.9c | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).