Data from the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (BRÅ, 2023a) shows that about one third of politically elected representatives at local, regional and national level were targeted by hate and threats during the election year 2022, mainly via social media. Almost 70 % of these were exposed more than once. Women and young people and representatives of MP are targeted more often than others. In most cases the perpetrators were anonymous, but if identifiable, they were usually angry middle-aged men often related to the far-right (extremist) movement. In addition to C and MP politicians as targets, hate and threats targeting climate scientists, climate journalists and particularly climate activists have increased since the Covid-19 pandemic. Several people active in the climate debate testify that hatred and threats have increased even more since the national elections in 2022. Hate crimes related to climate change is not yet a category in Swedish statistics and hate crime surveys (BRÅ, 2023b).

6.1. How is Nasty Rhetoric Used?

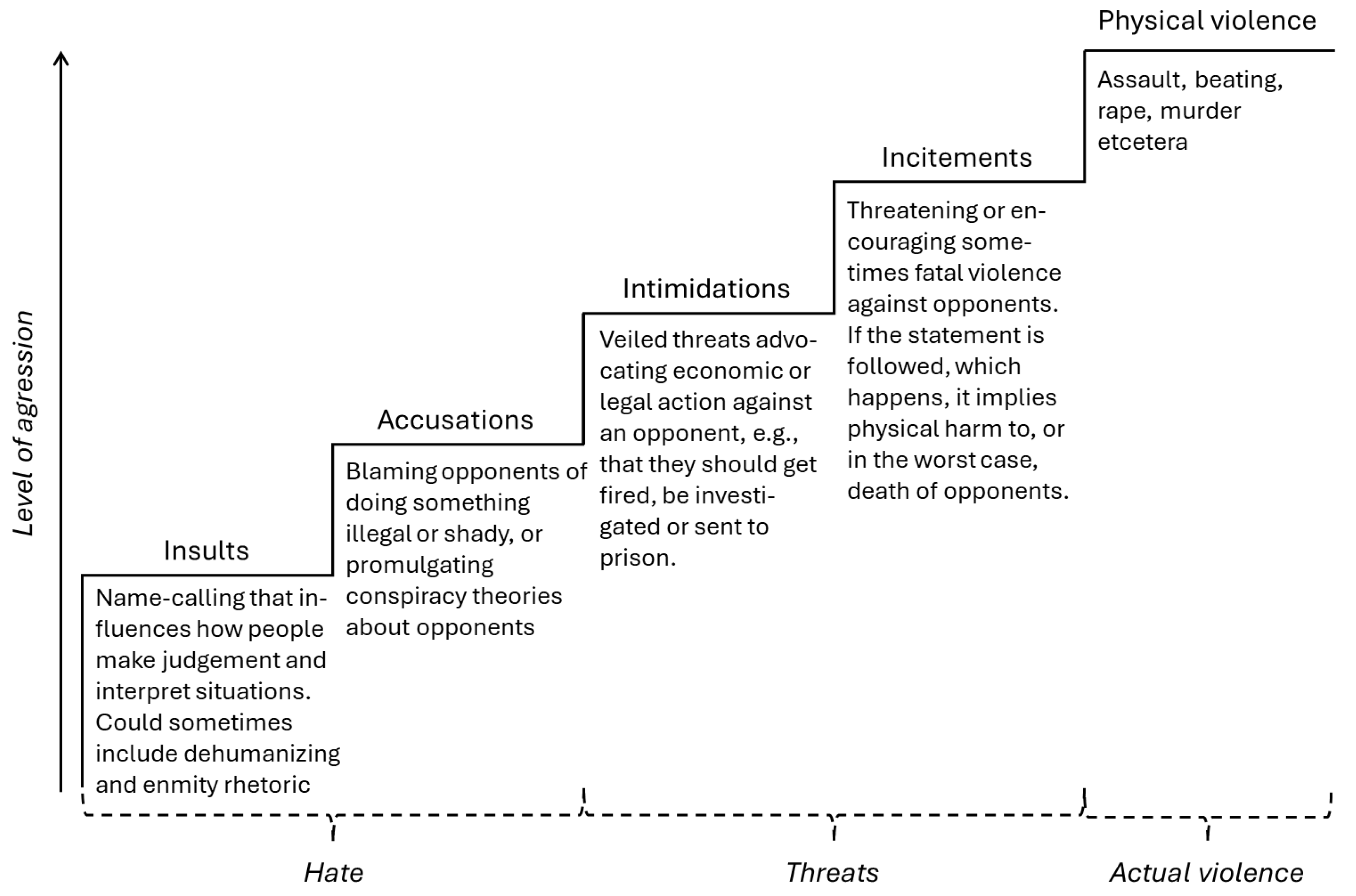

The results reveal that nasty rhetoric is used by members of all parties in the Riksdag but C. Former party leader of C, Annie Lööf, herself a target of far-right hate and threats from 2015 to 2022- when she resigned due to the threats, stood firm in criticizing the use of nasty rhetoric in Swedish politics. Emma Wiesner (C), top candidate in the 2024 EU elections, was the only politician in the final debate in Swedish television that did not use nasty rhetoric. Nasty rhetoric is widely used by party leaders and government ministers, including the PM. It is also used by neoliberal and far-right influencers and climate sceptics, applauding the weakening of Swedish climate policy. The political opposition in the Riksdag, and to a lesser extent scientists and activists, all advocating stronger climate policy based on climate science also use it. While Tidö parties and climate sceptics use all types of nasty rhetoric, from insults to incitements and physical violence, oppositional politicians and climate advocates only use insults and accusations.

That high-level politicians in the government and the Riksdag utter insults, accusations and intimidations towards journalists, scientists and activists can be considered an important reason for the increase in threats. Nasty rhetoric has become normalized when the PM and other cabinet ministers and people with leading positions in the Riksdag use it, calling XR “totalitarian”, “security threats”, “terrorists”, “saboteurs” and “a threat to Swedish climate governance and Swedish democracy” that should be “sent to prison”. Insults, accusations, intimidations and incitements are made openly, mainly in social media from official accounts of ministers and other politicians. Intimidations targeting climate activists are also made in national radio, on the streets, and in political debates in the Riksdag.

Politicians rarely humiliate or denigrate other politicians in person, but other political parties. Except for the hate on Greta Thunberg, the same holds true for nasty rhetoric of politicians targeting climate activists or scientists. It is primarily the organizations, not the persons who are targeted. Some exceptions in politicians’ rhetoric are the accusations of (i) former MP party leader Bolund calling the PM a “provoking naked liar”, (ii) former MP party leader Stenevi calling SD party leader Åkesson a “Nazi” and the climate minister a “week minister in a puppet government”, and (iii) S spokesperson Guteland criticizing the climate minister for her “superhero attitude”. Hate and threats sent by anonymous haters are often targeting individual climate activists, scientists, journalists and other outgroups, orchestrated by SD and AfS, who display names, photos, addresses and phone numbers of the ‘enemies’ in far-right extremist web forums.

Nasty rhetoric is an outspoken tactic of SD to entrench the ‘us vs. them’ and the ‘people vs. elite’ narratives. But it has turned out that SD also uses nasty rhetoric through its anonymous troll accounts targeting ministers of M-KD-L for being part of The Cry. The insults and accusations towards the government were condemned by the political opposition and criticized by PM Ulf Kristersson (M), who required an excuse and that posts on social media smearing the government were deleted, but he did not criticize the widespread use of nasty rhetoric in general – he uses it himself. In a statement after the revealing of SD’s troll factory, party leader Åkesson continued to claim that SD represents the ‘people’ and replied: “To you in the Cry...we are not ashamed. It is not us who have destroyed Sweden... It is you who are to blame for it”.

People from different quarters use nasty rhetoric differently and with different purposes. While Tidö politicians, libertarians, far-right movements and climate sceptics use nasty rhetoric to delegitimize and threaten their enemies to silence, insults and accusations from climate advocates target the government as a collective or the PM and Pourmokhtari directly to delegitimize them in affective response to what they consider to be inferior climate policy in substance and process. They also insult and accuse the PM and the climate minister for lack of leadership. Being climate minister, Pourmokhtari is bound to take the hit, although everyone understands that she is only a “liberal minister in SD’s puppet government”.

Climate activist organizations are a main target of nasty rhetoric of Tidö parties and its supporters. But they are also using it themselves, with a humoristic twist. Adhering to norms of deliberative democracy, sacralizing the good argument, hate and threats have little or no place in the repertoire of climate activists. On the contrary, climate ac-tivists use civil disobedience, are ‘radically kind’ and use humor in digital activism to transform democracy (Pickard et al., 2020; Sloam et al., 2022; Chiew et al., 2024). For in-stance, Greta Thunberg turned insults of then Brazilian president José Bolsonaro and then US president Donald Trump into humor, adding the Portuguese word “pirralha” (Eng. brat) and “A very happy young girl looking forward to a bright and wonderful future” to her X/Twitter profile (Vowles & Hultman, 2021a; White, 2022). The humoristic turn to ‘nasty’ rhetoric was also evident in Greta Thunberg’s insulting response to To-bias Andersson’s (SD) intimidation outside the entrance of the Riksdag – a laughter, saying that he is a looser – and the subtle insults related to the governments “climate meeting” with “civil society organizations”.

Another difference between insults and accusations of Tidö parties, the far-right movement and Timbro compared to the opposition, scientists and activists is that the former are grasped from thin air, based on emotions, while the latter are based on sub-stance and facts. Insults and accusations of the latter are used to enhance the good argument. The PM and the climate minister accused climate activists of being a threat to Swedish democracy, but without factual grounds, only emotions. When S party leader Andersson accused SD of being a threat to democracy, and MP leader Stenevi accused Pourmokhtari of being minister in a “puppet government”, these accusations have concrete bearing on results and conclusions from democracy research (e.g. Silander, 2024; V-Dem Institute, 2024; von Malmborg, 2024b, 2024c). They were not slurs, but well-substantiated accusations. It is ironically symptomatic that SD party leader Åkesson, basing his entire politics and rhetoric on emotional governance, accuses the former S–MP government’s climate policy to be based on emotions, not on facts, while Tidö climate policy is based on false hope and putative will of the people.

6.2. Why is Nasty Rhetoric Used?

Fear of system critique

Obviously, the highest representatives of Tidö parties as well as CSE and Timbro regard strong climate policy, requiring green economic and industrial transition, and climate activists as threats. Climate activists formulate system criticism based on cli-mate science calling for a just transition (Evans & Phelan, 2016; Wang & Lo, 2021). Tidö parties’ response is to demonize and delegitimize non-violent climate activists “a threat to democracy”, “totalitarian forces” or simply “terrorists” to be “sent to prison” and “executed”. Such accusations, intimidations and incitements are not a matter of isolated occasions, and it cannot be considered innocent mistakes. The words come from the highest-ranking politicians, including the PM, whose rhetoric agitates that climate activists really are a threat to democracy.

But when Nazis attacked participants in an antifascist meeting in a Stockholm suburb with fist fights and spray cans, the same politicians were not as sharp in their words. Contrary to the political opposition, Tidö leaders did not take the words Nazi or far-right extremists in their mouths. The PM did not mention the perpetrators at all but spoke sweepingly about how “an attack on a democratic meeting is an attack on our entire democracy”. When another Nazi attack targeting the premises of V occurred in late summer 2024, neither the PM nor any other minister commented the hate crime. They were silent. The situation was similar when it was revealed that SD party leader Åkesson invited the president of a criminal MC gang to his recent wedding. The PM didn’t dare to criticize him, even though the PM as well as Åkesson have stated that the actions of criminal gangs in Sweden can be equated with terrorism.

How come that we have a political climate in Sweden where Tidö politicians talk of climate activists as if they were Nazis, but not about Nazis as... Nazis? I want to believe that these politicians know that climate activists are not dangerous to Swedish citizens, that their actions of civil disobedience are not threatening our democracy. The only threat they pose is to expose the failures of Tidö and previous governments to embark on the just transition journey, and to form opinion for what possibly scares politicians and transition averted business more than appearing bad: an economic and political system that must change fundamentally.

That Greta Thunberg has gone from pet peeve to pariah among Tidö parties, CSE and Timbro and other climate sceptics is no coincidence. The change follows a sharpening of the climate activists’ message – economic degrowth (Heikkurinen, 2021). It is about the realization that the whole economic system of today is wrongly inverted (Bailey et al., 2011; Davidson, 2012). An insight transformed into a critique of the neoliberal economic system and its focus on free markets and economic growth (Euler, 2019; Khmara & Kronenberg, 2020). In addition, a critique of the hegemonic (neo)liberal democratic system with its increasing focus on restricted and competitive participation, as opposed to a more deliberative and inclusive ecological democracy (Pickering et al., 2020; von Malmborg, 2024a). Degrowth and a resulting perceived intrusion upon their dominant status in society is what right-wing and far-right politicians painting a threatening picture of climate activists are afraid of. Instead of answering the degrowth narrative with good arguments in a public debate, Tidö politicians use nasty rhetoric to silence the outgroup.

A similar fear of system critique, Olof Palme’s attacks on neoliberal economics and libertarian political philosophy as threats to the welfare state, and Annie Lööf’s socio-liberal views on migration policy, made Swedish right-wing and far-right politicians in M, KD, SD and AfS and their supporters paint pictures that Palme and Lööf stood for something evil. For this, they should be punished – silenced:

“There shall be only One Truth!”

1.1.1. Libertarian and far-right populism

This fear is also why neoliberal and libertarian thinktanks such as

Atlas Network and Timbro have orchestrated lobbying in Sweden and world-wide (The Atlas Network: Big Oil, Climate Disinformation and Constitutional Democracy. Research Seminar, University of Technology Sidney, 8 December 2023.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tlQOw6qpblY), financed by the oil and gas industry, to initiate climate denying movements and cast doubt on climate science and climate policy, influence politicians, and attack climate activists (Ekberg & Pressfeldt, 2022; Walker, 2023). The current Swedish PM and minister of justice, both from M, worked at Timbro when the campaigning started. The former CEO of Timbro, responsible for nasty rhetoric towards climate activists and journalists, was recently appointed Swedish minister of development aid and trade. Eight other Tidö ministers, including the climate minister, were educated at the Sture Academy, Timbro’s cutting-edge education in libertarian ideology, politics and opinion formation. Timbro also approached SD to make them take on a sceptical position on climate change and climate policy.

Initially championing environmentalism, being an important ingredient in ‘blood and soil’ nationalist narratives, SD and other far-right populist parties began to deny climate change a decade or two ago. Based on a combination of anti-establishment rhetoric, knowledge resistance and emotional communication of doubt, industrial/breadwinner masculinities and ethnonationalism, SD is mobilizing a ‘culture war’ on strong climate policies (Hultman et al., 2019; Jylhä et al., 2020; Agius et al., 2021; Vihma et al., 2021; Vowles & Hultman, 2021a). They look back to a great national past during the oil-fueled record years of the 1950s and 60s, when men had lifelong jobs in industry and sole access to society’s positions of power. It is mainly white older men that support SD and are climate sceptics (Vowles & Hultman, 2021a).

Accusing Swedish established media of being “climate alarmist propaganda centers” belonging to a “left-liberal conspiracy”, SD and other nationalist right-wing groups built their own ecosystem of digital media news sites, blogs, video channels and anonymous troll accounts in social media, which did not have to relate to the rules of press ethics. Normalizing knowledge resistance and using nasty rhetoric were central to their strategy of structural policy entrepreneurship (von Malmborg, 2024a). And the tie between Tidö ministers and climate denying SD is tighter and stronger than the Tidö Agreement. At the center is Timbro and CSE, two of few organizations that welcomed Tidö low-ambition climate policies. Tidö climate governance, including nasty rhetoric, adheres not only to populism, but also libertarian neoliberalism. Many strategies and actions of far-right populists around the world ascend from libertarian philosophy and neoliberal economics and the ‘There is no Alternative’ narratives used to support it (Goldwag, 2017; Séville, 2017).

Timbro had a significant role also in the hate and threats targeting Olof Palme. In 1984, they published the book “Who is Olof Palme?” (Östergren, 1984), the most elaborate and offensive attack on Palme as a person and politician.

1.1.1. The emperor is naked

Contrary to nasty rhetoric of Tidö parties and the far-right movement, nasty rhetoric of the political opposition, climate activists and scientists does not aim to silence their opponents. They value pluralism and freedom of speech. Like Kamala Harris and Tim Walz are calling Donald Trump and J.D. Wance “weird”, former party leaders of MP, Per Bolund and Märta Stenevi show with their accusations and the eye of a child that the PM and climate minister are “naked emperors” – that the Tidö quartet lack credible political reforms, no visions of building a climate neutral society. Tidö’s response to the climate emergency is “Tourette-like tirades” about new nuclear power at upfront costs of about USD 30–60 billion and USD 1 000 in annual nuclear taxation per Swedish household. The nasty rhetoric of Bolund and Stenevi, an everyday call to laugh at the emperor’s nakedness, can arouse broad popular engagement. This is indicated by the results of the 2024 EU elections, were Swedish left-wing and green parties more than doubled their votes compared to the national elections in 2022, collecting almost 25 % of the votes in total. SD dropped from 20.5% in the national elections to 13 % in the EU elections, for the first time ever getting reduced support in a nationwide election. The main reason for the success of the red–green parties and decline of SD was the high interest in climate policy among the voters, ranking it as a top three issue in the elections (von Malmborg, 2024a).

6.4. A Threat to Liberal Democracy

According to Zeitzoff (2023), nasty rhetoric is divisive and contentious and includes insults and threats with elements of hatred and aggression that entrenches ‘us vs. them’ polarization, designed to denigrate, deprecate, hurt and delegitimize their target(s). As found in this study, nasty rhetoric is used by climate sceptic right-wing and far-right people to emotionally hurt their enemies, threatening them to silence.

In all, this study confirms but also adds to previous research on nasty politics, focusing on its implications for democracy (see Zeitzoff, 2023). When politicians view their opponents as traitors or illegitimate, they violate a core principle in liberal and deliberative democracy – pluralism of ideas (von Malmborg, 2024a). Uncivil disagreement between political opponents breeds general mistrust in politics (Mutz & Reeves, 2005) Previous studies tell that some politicians make these nasty appeals (i) to grab media attention and attention of targeted groups (Ballard et al., 2022), (ii) to be persuasive and strike an emotional chord and solidify ingroup members (Schulz et al., 2020; Dimant, 2023), and (iii) pave the way for democratic breakdown (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018). Zeitzoff (2023, p. 53) argues that nasty politics bear some positive effects to democracy since it provides a tactic for marginalized groups and politicians to exercise power, but that the negative impacts are more detrimental:

It makes people more cynical of democracy and less willing to vote and participate;

Politicians in power can use nasty politics as a tool to demonize their political rivals and stay in power, eroding the democracy in the process;

An increase in nasty politics leads good politicians to choose not to run and to re-tire, and nastier politicians take their place; and

Heightened nasty politics precedes actual political violence.

The latter three have been identified and described in this study. But the literature primarily focuses on nasty rhetoric between politicians and the silencing of politicians like Annie Lööf, who resigned as party leader and from all political assignments after years of steady-fast resistance against the haters – “They shouldn’t fucking win”. Anxiety and fear eventually made her fed up with politics, crying herself to sleep. It hooks onto what she and many other elected officials have been exposed to for many years by digital online warriors who hide behind their computer screens: “traitor”, “assassinate”, “kill”.

But Zeitzoff and other scholars do not analyze and problematize nasty rhetoric targeting activists, scientists and journalists. These groups have important roles in a liberal democracy. As argued below, nasty rhetoric leads good scientists, journalists and non-violent activists to silence, giving space to nastier people to take their place, eroding the democracy in the process.

1.1.1. Silencing climate activists

Some climate activists use civil disobedience to protest governments’ lack of action to reduce GHG emissions (Berglund & Schmidt, 2020). Failure to understand such cli-mate actions as a right to demonstrate is a mistake, in an antiliberal democratic direction where constitutional rights are at stake. The right to demonstrate is a central building block in every democratic society. It is protected in Swedish constitution and through several international conventions. Even civil disobedience is covered by the right to demonstrate if violence is not used.

Since 2020, 310 persons have been prosecuted in Swedish district courts for different crimes related to civil disobedience, some of them several times. Of these, 200 persons were convicted, mainly to fines or suspended sentence. In 2022, without change of legislation, prosecutors around Sweden suddenly began to charge climate activists performing roadblocks at demonstrations for sabotage. Between summers 2022 and 2023, 25 persons were convicted for sabotage, some of which were sentenced to prison, but most were later acquitted in the Court of Appeal. Several climate activists felt that this change in the judicial system was an act of political commissioning following the campaigning and nasty rhetoric of leading SD and M politicians.

The new legal praxis in lower courts, cheered by the minister of justice, can be seen as a threat to human rights and freedom of demonstration. Swedish law professor Anna-Sara Lind considers, in an interview in Swedish newspaper Dagens Arena, the criminal classification of roadblocks as sabotage to be disproportionate. “Limitations of constitutional rights may only take place in the manner specified in the constitution”, Lind says and specify that a “restriction may not extend so far that it constitutes a threat to the free formation of opinion”. Categorizing roadblocks as sabotage gives the police the right to preventive interception of people without concrete criminal suspicions, and a person can be charged of sabotage for just planning a roadblock. This happened in the UK in July 2024, when several climate activists were sentenced to four years in prison for planning a roadblock in a Zoom meeting.

A similar development of increased state repression of climate activists is seen in other European countries, e.g. Austria, France, Germany, Spain and the UK. UN special rapporteur on environmental organizations’ rights under the Aarhus Convention, Michel Forst, claims that “by categorizing environmental activism as a potential ter-rorist threat, by limiting freedom of expression and by criminalizing certain forms of protests and protesters, these legislative and policy changes contribute to the shrinking of the civic space and seriously threaten the vitality of democratic societies” (Forst, 2024, p. 11). But not all who perform roadblocks are considered terrorists. Think of farmers blocking highways in Europe and burning hay bales in Brussels months before the EU elections in June 2024. Some even destroy public buildings. They were not treated as terrorists but hailed as heroes by far-right populist politicians such as Marine le Pen and Victor Orbán. It’s a matter of money and political clout.

In relation to state repression of climate activists in Sweden, Michel Forst recently criticized the Tidö government for its handling of a case where a person engaged in Mother Rebellion was fired from her job at the Swedish Energy Agency due to accusations and intimidations of her predecessor, right-wing media and minister for civil defence that she was a threat to Swedish national security. In a letter to the Swedish government, Forst states:

“She appears to have been subjected to punishment, persecution and harassment because of her climate commitment and participation in peaceful environmental demonstrations. /…/ In this time of climate emergency, I am gravely concerned that the government has deemed her participation in peaceful environmental protests a threat to national security. /…/ I am also deeply concerned about minister Bohlin’s public statements. Bohlin, as a minister in the Swedish government, has a responsibility under the Aarhus Convention to protect citizens' right to be active in environmental issues.”

Sentence to prison and getting fired are not the only retributions of climate activists. A young female climate activist being intimidated by SD at a FFF demonstration testifies how the hatred affected her:

“They never said who they were but wanted to ask a few questions. I had no idea that they had evil intent. It was very naïve. /.../ They had put on clown music and cut the interview so that I appeared stupid and ignorant. I felt extremely humiliated. The video had over 2,000 comments and the tone was very harsh and mocking. From fear that right-wing extremists would start harassing me, I didn’t dare to respond to the comments.”

1.1.1. Silencing climate journalists

Independent media plays an important role to raise awareness in societies, which is why the first actions of autocratizers are often directed against established media (Laebens & Lührmann, 2021). Attacks on public service and independent media can discourage critical scrutiny of power. When journalists are hated and threatened, it risks that investigations are not carried out and important facts are never published. Consequently, citizens loose important information. In Sweden, Tidö parties, the far-right movement and other climate sceptics consider climate journalists in established media to belong to a left-liberal conspiracy censoring the climate debate and being climate alarmist propaganda centers. Public service journalists have experienced an increase of insults and incitement since 2019 when financing of Swedish public service changed from a license fee to taxation.

A widespread culture of silence and self-censorship has taken hold. In a recent survey by the Swedish Union of Journalists, as many as 39 % state that they engage in self-censorship to avoid hate and threats, 48 % that they have adapted their reporting for the same reason (Swedish Union of Journalists,

https://www.sjf.se/yrkesfragor/yttrandefrihet/hot-och-hat-mot-journalister). A long-since female climate journalist testifies how the hate and threats affected here:

“At the same time as I have carried out my assignment as a climate journalist, I have been in a storm of hatred, threats and insults. Lies about my person and alleged political affiliation have been glued to me. My feeling of powerlessness has been paralyzing at times. I have, to use an old-fashioned word, felt dishonored. Therefore, I have now resigned as a journalist.”

Besides hate and threats targeting journalists, Tidö parties have recently reviewed the guidelines for public service, proposing that public service journalism in the future must be evaluated by external reviewers, and adapt the content to a certain type of populist political opinion, which goes against basic journalistic principles of impartial-ity, neutrality of consequences and truth-seeking (Bjereld, 2024). As a response, Swedish public service television and radio have decided not to keep their climate correspond-ents, effectively reducing the dissemination of information and knowledge about cli-mate change and climate policy to Swedish citizens.

1.1.1. Silencing climate journalists

Nasty rhetoric attacks on climate scientists are made to delegitimize individual researchers, but also to cast doubts on the scientific community and the role of science in providing knowledge for citizens, businesses, public authorities and politicians to make informed decisions. After being attacked, many researchers refrain from researching in areas that have become politically charged, and those who conduct research in such areas are often afraid to communicate their research results to the public. When scientists feel attacked and pressured by the far-right, it risks leading to perspectives that are considered controversial being weeded out. A Swedish professor of climate policy testifies how hatred and threats affected him:

“I’ve received hate and threats for long. Being criticized in substance is part of being a re-searcher, that is what brings science forward. But being criticized in person, often related to conspiracy theories, is detrimental. Once, haters threatened to send a death squad to the university. The hatred and threats drain me of energy and to avoid it, I refrain from participating in the public discussion on climate policy.”

Claims that climate science is “just an opinion” and that science based climate activism is “undermining public trust in science” invokes knowledge resistance (Strömbäck et al., 2022), that poses grave challenges for the functioning of liberal democracy, e.g. (i) citizens ability to evaluate public policy, hold politicians accountable and make informed votes (Wikforss, 2021), (ii) undermining democratic processes by corrupting political discussions (Gutmann & Thompson, 1996; Dahl, 1998), and (iii) undermine the legitimacy of the democratic system as such (Lago & Coma, 2017).

Many scientists have asked themselves how they can spread awareness about climate science results when political decision-makers are constantly ignoring warnings published in scientific journals, magazines and newspapers. Some have turned to climate activism within Scientists Rebellion. Such activism may be perceived as political. Then minister of education and research Mats Persson (L) claimed, contrary to scientific findings, that scientists' climate activism undermines trust in science and should be stopped. But such activism is based on scientific knowledge and well in line with the third duty of Swedish scientists according to the law on higher education: “Knowledge shall be disseminated about what experience and knowledge has been gained and about how these experiences and knowledge can be applied”. Swedish professor of philosophy of science, Harald A. Wiltsche, argues that passive consent, non-activism, would be contrary to what is expected of Swedish scientists under Swedish law. One does not have to look far at history to see that science-based activism and civil disobedience have been instrumental in ending social injustices such as discrimination, slavery, apartheid, and providing universal suffrage, and thereby in building our modern liberal society.

1.1.1. It is the whole that worries

Swedish scholars of democracy (Rothstein, 2023; Silander, 2024; V-Dem Institute, 2024; von Malmborg, 2024a) as well as CRD and UNAS argue that the current developments in Swedish politics and society risk weakening Sweden’s liberal democracy and may be another step in the process of gradual autocratization overseen by democratically elected but antidemocratic leaders. Tidö parties use democratic institutions to erode democratic functions, e.g. censoring media, imposing restrictions on civil society, harassing activists, protesting, and promoting polarization through disrespect of counterarguments and pluralism (Silander, 2024; V-Dem Institute, 2024; von Malmborg, 2024a). Even the editorial offices of Sweden’s largest newspapers, independent liberal Dagens Nyheter, and Sweden’s largest tabloid, independent social democrat Aftonbladet, are worried of the development, arguing that “Sweden is now taking step after step towards less and less freedom”.

Autocratization is hard to identify since it often takes place gradually in democratic states (Sato et al., 2022). It is the sum of the decisions and the style of governance of il-liberal and anti-democratic actors that leads to defective democracies with increasingly illiberal characteristics (Lührmann et al., 2020; Mudde, 2021; Merkel & Lührmann, 2021). It is this whole that worries, or as stated by Merkel and Lührmann (p. 870), “if the illiberal virus persists long enough, it transforms the liberal dimension, polarizes the political space, and may affect the institutional core of democracies as well”.

This concern of democracy experts made opposition and party leader Magdalena Andersson (S) write a critical op-ed in Dagens Nyheter six months after the Tidö government entered office, accusing the government of showing totalitarian tendencies:

“Instead of a traditional government, we have a right-wing regime led by Sweden Democrats. A regime that uses its position of power to threaten and silence critical voices. /…/ The SD led government destroys what makes Sweden Swedish.”

Following this claim, 18 representatives of labor unions, civil society organizations and left-liberal thinktanks recently called in an op-ed for a commission to (i) appoint an inquiry with proposals to defend and strengthen democracy, (ii) protect the right to freedom of organization and assembly, and (iii) strengthen support for civil society and journalism.

Shortly after, 74 scientists, journalists and writers in Sweden, including myself, made an appeal in Sweden’s largest newspaper that Swedish opinion leaders, including the Tidö government and the Riksdag, must take measures to end nasty rhetoric due its detrimental effects on democracy. The appeal includes 25 emotional testimonies embodying the emotions and vulnerabilities of the targets of nasty rhetoric. Many of us were threatened to silence but chose to raise our voice again in company of others, to stand the grounds for liberal democracy. We spoke also for those who continue to stay silent. those who don’t dare to speak of fear to be hated and threatened again.

Significant for the political climate in Sweden and the self-positioning of libertarians and far-right populists as morally superior, this call was immediately attacked by a leading Swedish libertarian YouTube influencer. Manipulating his 50K followers on Facebook, he claimed that we, the signatories, are “inflated prima donnas” performing a “Princess and the Pea coterie” being sad and call for political action to restrict freedom of speech because “some insults made us loose our privilege of interpretation”. In his post, he ignored the testimonies of incitement, threats of assault and death. Our call for an end to nasty rhetoric was not about our privilege of interpretation, but about our dignity as human beings and more importantly about safeguarding basic norms and institutions in a liberal, pluralistic democracy.