Submitted:

30 August 2024

Posted:

02 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Plant Material

2.2 Flour Production

2.3 Preparation of Spaghetti-Type Pasta

2.4 Characterization of P. aculeata and P. grandifolia Flour and Spaghetti-Type Pasta

2.4.1. Physical and Physicochemical Analyses and Antioxidant Activity of the Flours

2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG)

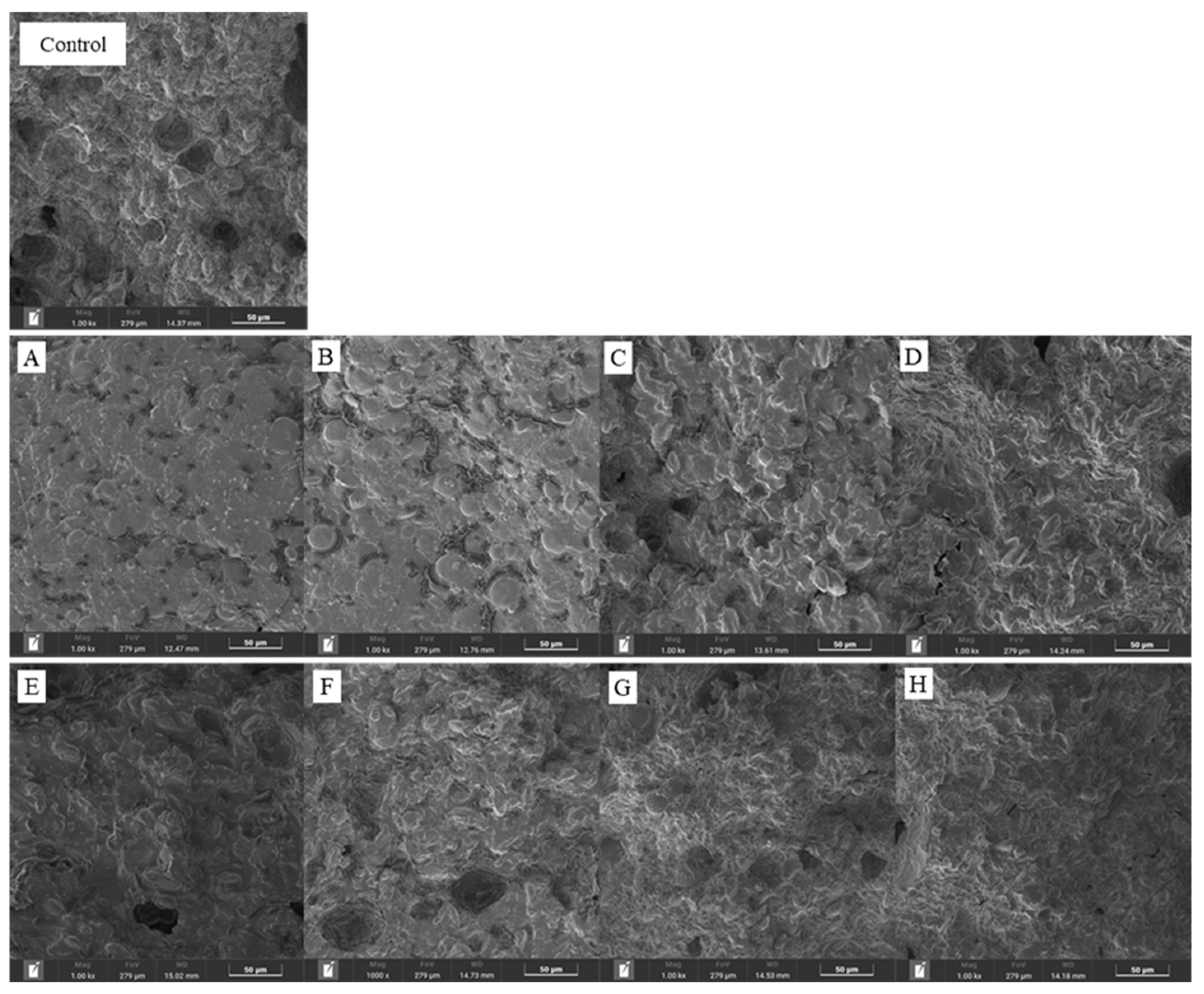

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Analysis of P. aculeata and P. grandifolia Flours

3.1.1. Analysis of Total Extractable Polyphenols, Antioxidants, and Toxicity

3.2. Physical Analyses of P. aculeata and P. grandifolia Flours

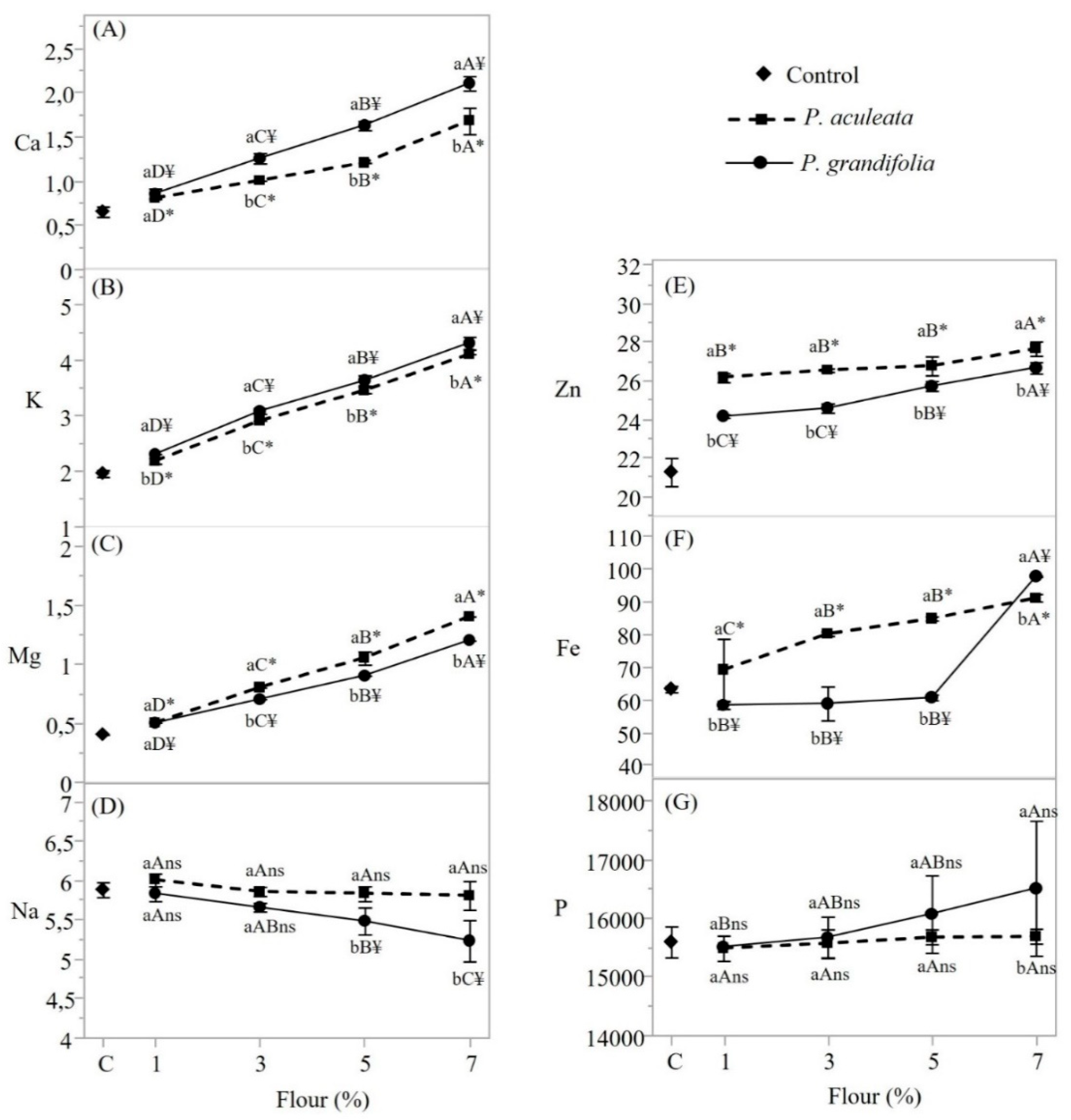

3.3. Analysis of Mineral Content in Pereskia spp. Flours.

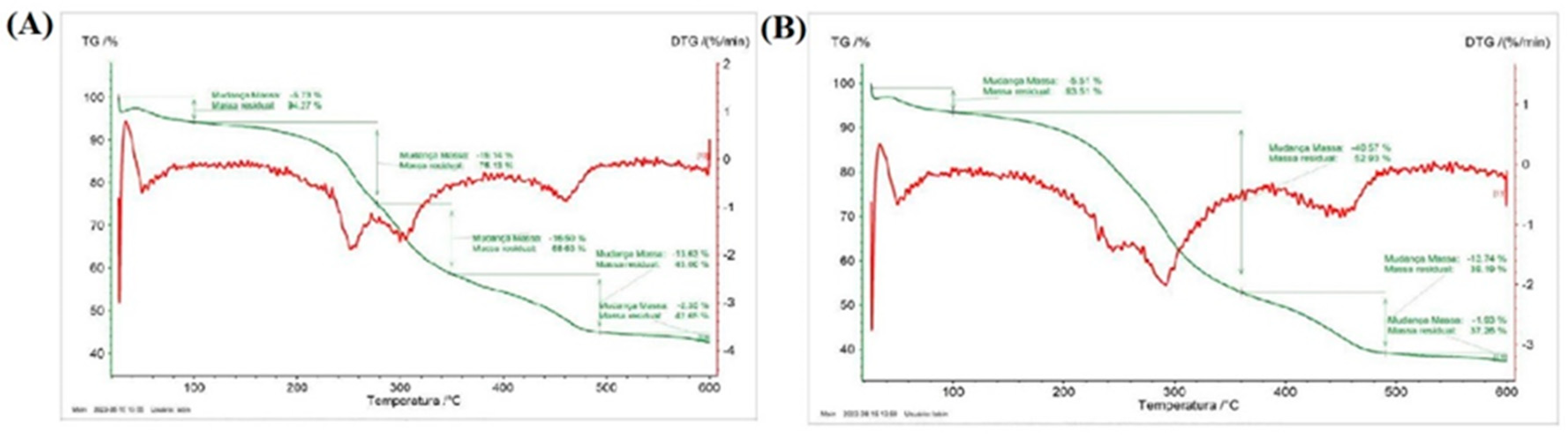

3.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Derivative Thermogravimetry (DTG)

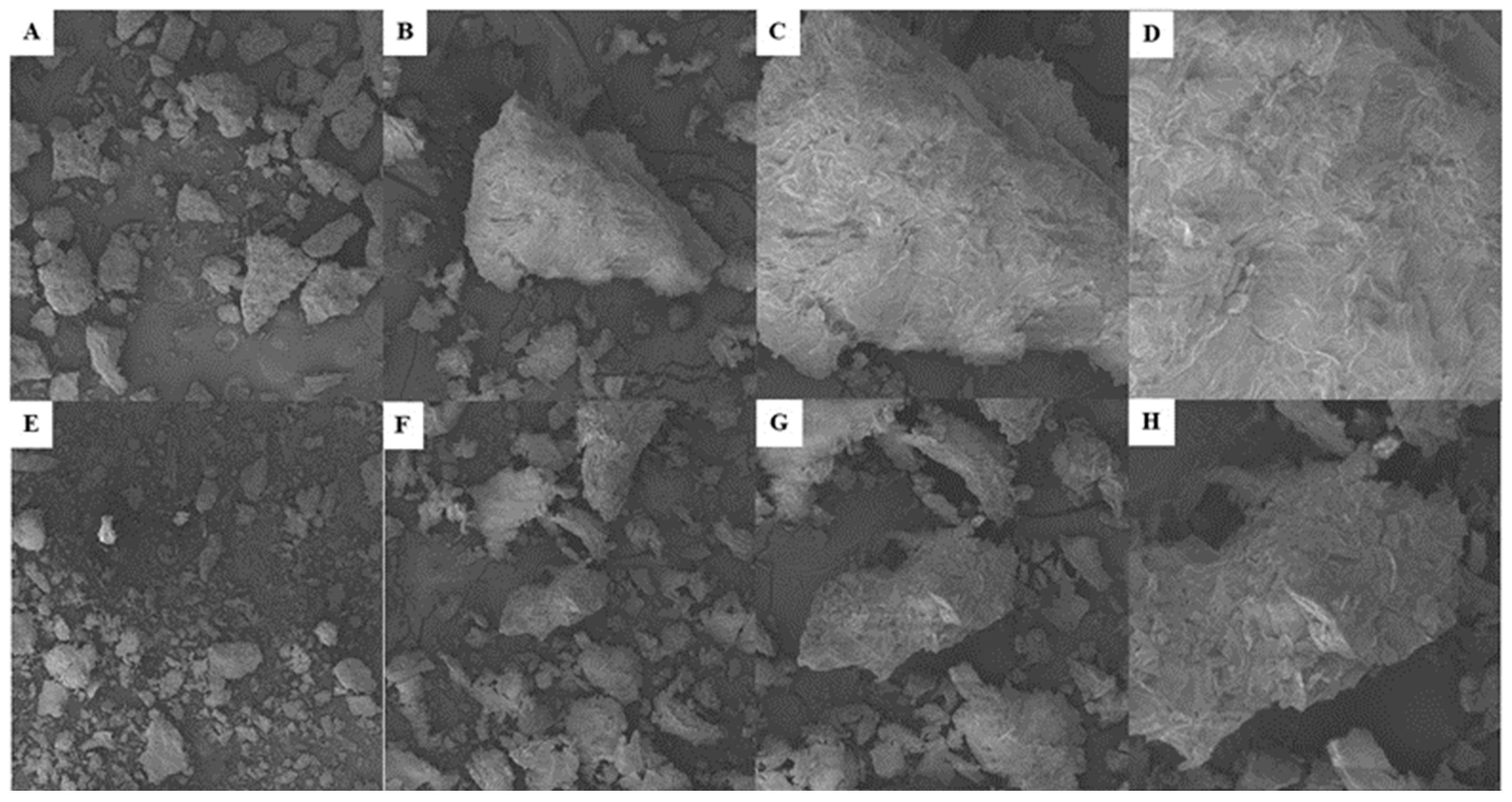

3.5 Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

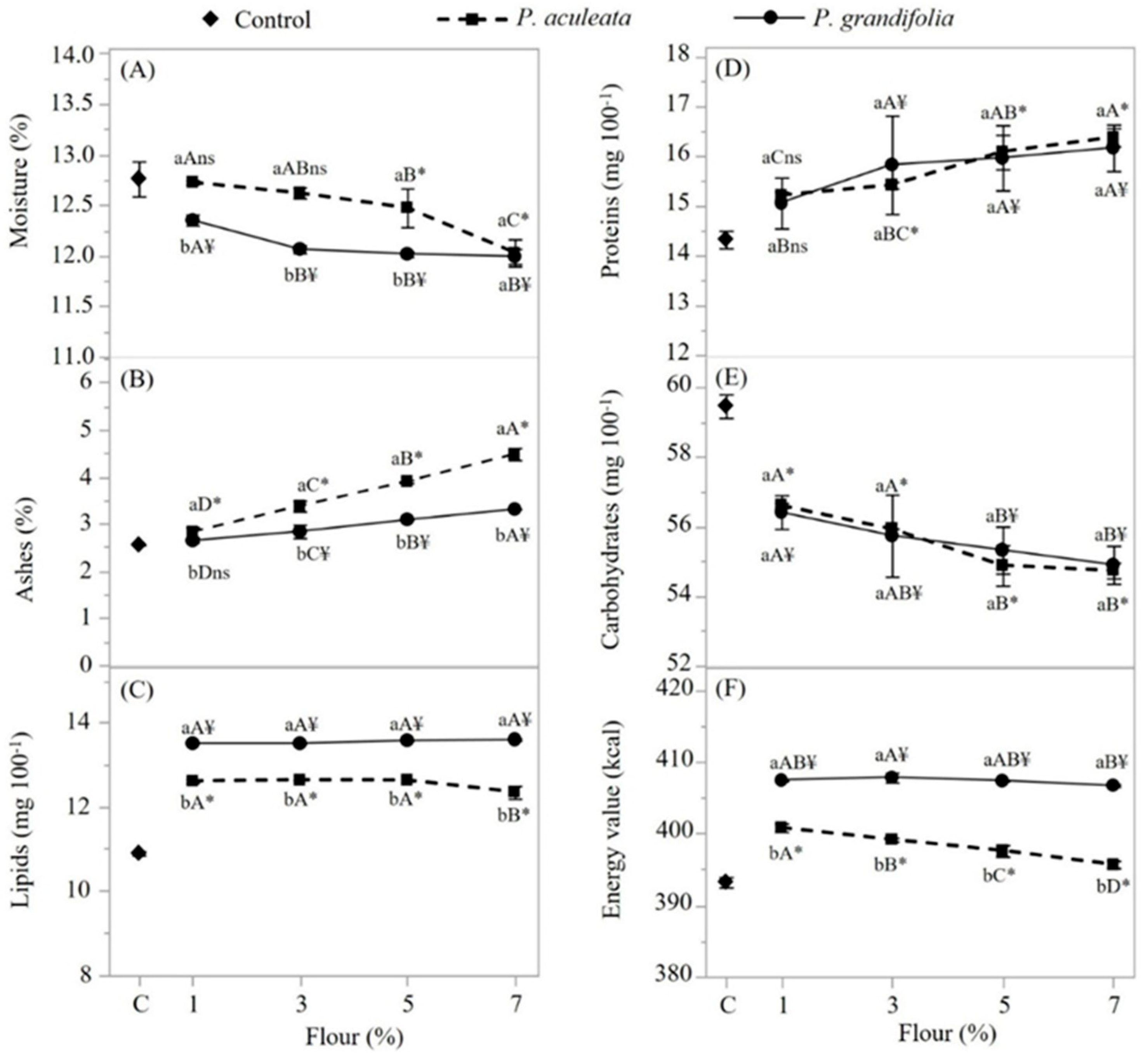

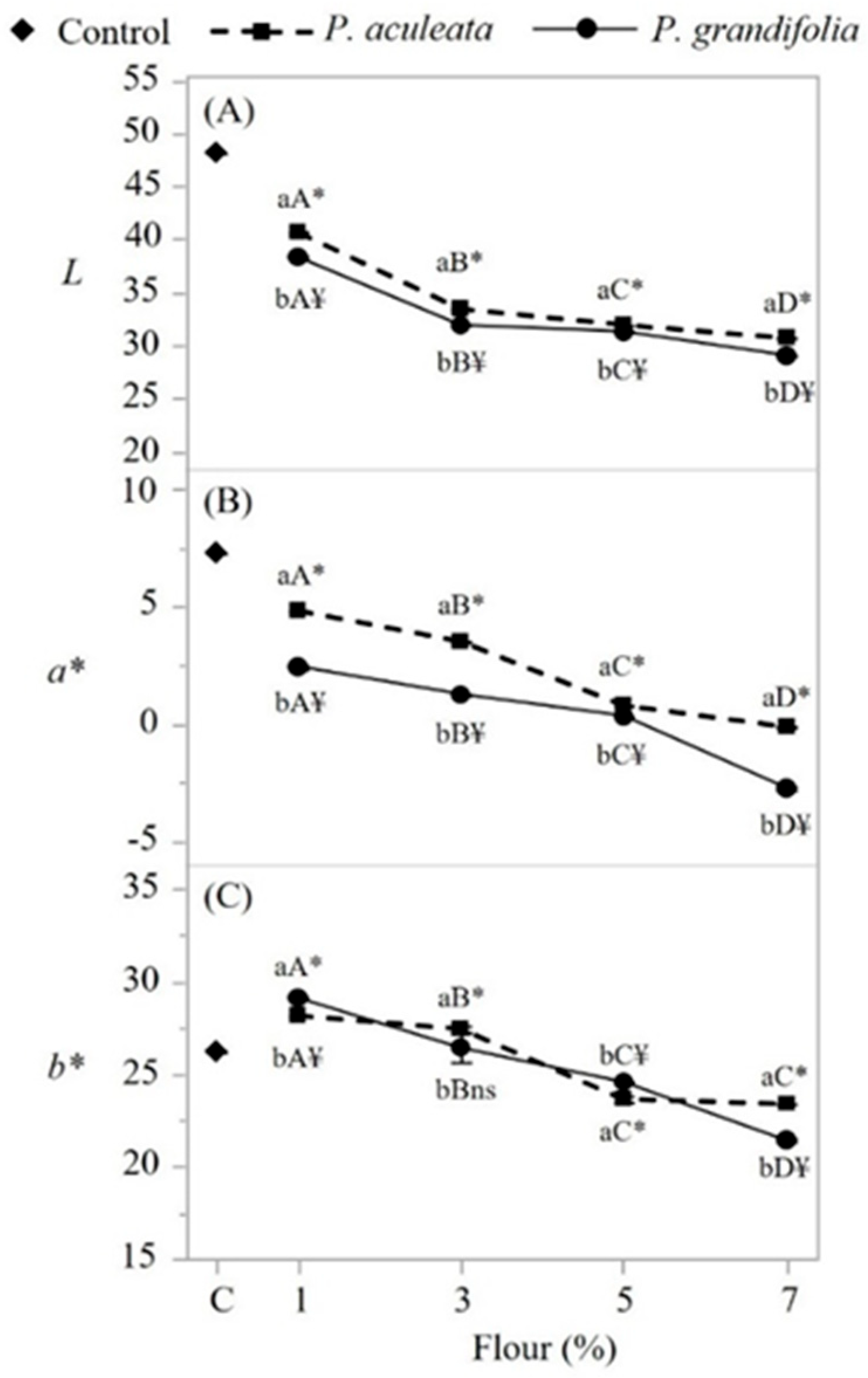

3.6. Characterization of Spaghetti-type Pasta

4. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO; FIDA; OMS; PAM; UNICEF. O estado da segurança alimentar e nutricional no mundo 2023; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Fome no Brasil piorou nos últimos três anos, mostra relatório da FAO. Ministério do Desenvolvimento e Assistência Social, Família e Combate à Fome, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mds/pt-br/noticias-e-conteudos/desenvolvimento-social/noticias-desenvolvimento-social/fome-no-brasil-piorou-nos-ultimos-tres-anos-mostra-relatorio-da-fao(accessed on 2 ago. 2024).

- Hisatomi, C.M.; Gorgen, D.K.; Roginski, G.S.; Hoffmann, L.F.; da Silva, T. M.; Carnitatto, I.; Garcia, J.R.N. Utilização da planta alimentícia não convencional ora pro nobis em educação nutricional. Brazilian Journal of Animal and Environmental Research 2020, 3, 3846–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.F.N.; Silva, S.H.; Baron, D.; Oliveira Neves, I.C.; Casanova, F. Pereskia aculeata Miller as a Novel Food Source: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição, M. C.; Junqueira, L. A.; Guedes Silva, K. C.; Prado, M. E. T.; de Resende, J. V. Thermal and Microstructural Stability of a Powdered Gum Derived from Pereskia aculeata Miller Leaves. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 40, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A. F. O. F. Produção de massas alimentícias isentas de glúten a partir de subprodutos da indústria alimentar. Dissertação (Mestrado), Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Takeiti, C.Y.; Antonio, G.C.; Motta, E.M.P.; Collares-Queiroz, F.P.; Park, K.J. Nutritive Evaluation of a Non-Conventional Leafy Vegetable (Pereskia aculeata Miller). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrinho, J. H. B.; Oliveira, J. F. S.; Fernandes, J. S.; Oliveira, A. S.; Paula, H. C. B.; Feitosa, J. P. A. Characterization of a Powdered Gum Derived from Pereskia aculeata Miller Leaves. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 51, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cazagranda, C.; Amancio, R.; Feiten, M. C.; Gilioli, A.; Gonzalez, S. L.; Fagundes, C. Obtenção de farinha de ora-pro-nóbis (Pereskia aculeata Miller) e sua aplicação no desenvolvimento de biscoitos tipo cookie. Cadernos de Ciência & Tecnologia 2022, 39, 27148. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M. C.; Araújo Ribeiro, P. F.; Kaminski, T. A. Obtenção e caracterização físico-química da farinha de ora-pro-nóbis. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2022, 5, 6878–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciríaco, A. C. A.; Mendes, R. M.; Carvalho, V. S. Antioxidant activity and bioactive compounds in ora-pro-nóbis flour (Pereskia aculeata Miller). Braz. J. Food Technol. 2023, 26, e2022054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R. L. A.; Oliveira, L. S. C.; Silva, F. L. H.; Amorim, B. C. Caracterização da poligalacturonase produzida por fermentação semi-sólida utilizando-se resíduos de maracujá como substrato. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2010, 14, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, R.V.; Brabet, C.; Hubinger, M.D. Aplicação da secagem por atomização para a obtenção de produtos funcionais com alto valor agregado a partir do açaí. Inclusão Social 2013, 6, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hausner, H.H. Friction conditions in a mass of metal powder. Powder Metall 1967, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, J.E.; Moore, C.O. Cold water soluble granular starch for gelled food composition. U. S. Patent 4465702, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Chauca, M.; Stringheta, P.C.; Ramos, A.M.; Cal-Vidal, C. Effect of the carriers on the microstructure of mango powder obtained by spray drying and its functional characterization. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2005, 6, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSTITUTO ADOLFO LUTZ (IAL). Normas Analíticas do Instituto Adolfo Lutz: Métodos Químicos e Físicos para Análise de Alimentos, 4th ed.; IAL: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008; p. 1020. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obanda, M.; Owuor, P.O. Flavanol Composition and Caffeine Content of Green Tea as Quality Potential Indicators of Kenya Black Teas. J. Food Agric. 1997, 74, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, M.S.M.; Alves, R.E.; Brito, E.S.; Morais, S.M.; Sampaio, C.G.; Jiménez, J.P.; Calixto, F.D.S. Metodologia Científica: Determinação da Atividade Antioxidante Total em Frutas pela Captura do Radical Livre ABTS+; Comunicado Técnico 128; EMBRAPA Agroindústria Tropical: Fortaleza, CE, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B.N.; Ferrigni, N.R.; Putnam, L.B.; Jacobsen, L.B.; Nichols, D.E.; McLaughlin, J.L. Brine Shrimp: A Convenient General Bioassay for Active Plant Constituents. J. Med. Plant Nat. Prod. Res. 1982, 45, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, S. M. D. Obtenção da farinha de ora-pro-nóbis (Pereskia aculeata Miller e Pereskia grandifolia Haw) e sua aplicação em massas de pão sem glúten; Monografia (Tecnologia em Alimentos), Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná: Londrina, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, D.B.; Dias, T.J.; Rocha, V.C.; Chaves, A.C.T. Determinação do Teor de Cinzas em Alimentos e sua Relação com a Saúde. Rev. Ibero-Am. Humanid. Ciênc. Educ. 2021, 7, 3041–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEPA—UNICAMP. Tabela Brasileira de Composição de Alimentos, 4th ed.; NEPA—UNICAMP: Campinas, Brazil, 2011; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada - RDC Nº 272, de 22 de setembro de 2005. Aprova o Regulamento Técnico para Produtos Vegetais, Produtos de Frutas e Cogumelos Comestíveis. Diário Oficial da União, Poder Executivo, 23 de setembro de 2005.

- Manetta, G.B.; Romano, B.C.; Costa, T.M.B.; Triffoni-Melo, A.T. Utilização de farinha de Ora-Pro-Nobis (Pereskia aculeata Miller) em preparação de biscoito de polvilho. Braz. J. Dev. 2023, 9, 1494–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.E.F.; Corrêa, A.D. Utilização de cactáceas do gênero Pereskia na alimentação humana em um município de Minas Gerais. Ciênc. Rural 2012, 42, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, V.B.V.; Bezerra, R.Q.; Chagas, E.G.L.; Yoshida, C.M.P.; Carvalho, R.A. Ora-pro-nobis (Pereskia aculeata Miller): A Potential Alternative for Iron Supplementation and Phytochemical Compounds. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2021, 24, e2020180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Lagnika, C.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Jiang, N.; Song, J.; Zhang, M. Comparative Evaluation of Nutritional Properties, Antioxidant Capacity and Physical Characteristics of Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata L.) Subjected to Different Drying Methods. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, T.M.S.; Mendiola, J.A.; Rivera, G.Á.; Mazzutti, S.; Ibáñez, E.; Cifuentes, A.; Ferreira, S.R.S. Protein Valorization from Ora-Pro-Nobis Leaves by Compressed Fluids Biorefinery Extractions. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 76, 102–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.I.O.; Costa, F.; Paulino, C.G.; Almeida, M.J.O.; Damaceno, M.N.; Santos, S.M.L.; Farias, V.L. Effect of Pasteurization on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Ziziphus joazeiro Mart. Fruit Pulp. Res. Soc. Dev. 2020, 9, e135953245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.O.; Santos, D.N.S.; Cosenza, G.P.; Melo, J.C.S.; Monteiro, M.R.P.; Araújo, R.L.B. Determinação da Atividade Antioxidante de Polifenóis Extraíveis, Macromoleculares e Identificação de Lupanina em Tremoço Branco (Lupinus albus). Sci. Electron. Arch. 2019, 12, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.A.A.; Corrêa, R.C.G.; Barros, L.; Pereira, C.; Abreu, R.W.V.; Alves, M.J.; Calhelha, R.C.; Peralta, R.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phytochemical Profile and Biological Activities of ‘Ora-Pro-Nobis’ Leaves (Pereskia aculeata Miller), an Underexploited Superfood from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Food Chem. 2019, 294, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, V.; Yoshida, C.; Boesch, C.; Goycoolea, F.; Carvalho, R. Iron Uptake by Caco-2 Cells from a Brazilian Natural Plant Extract Loaded into Chitosan/Pectin Nano-and Micro-Particles. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, E45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.C.; Gonçalves, F.F.; Castanheira, C.R.; Ferreira, K.A. Desenvolvimento de Kit para Determinação e Visualização de Fluidez de Pós para Aplicação em Aulas Práticas de Farmacotécnica, Operações Unitárias e Estágio de Manipulação. Braz. J. Dev. 2022, 8, 16488–16498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhalakshmy, S.; Bosco, S.J.D.; Francis, S.; Sabeena, M. Effect of Inlet Temperature on Physicochemical Properties of Spray-Dried Jamun Fruit Juice Powder. Powder Technol. 2015, 274, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanova, J.C.O.; Lima, T.H.; Patrício, P.S.; Pereira, F.V.; Ayres, E. Síntese e Caracterização de Beads Acrílicos Preparados por Polimerização em Suspensão Visando Aplicação como Excipiente Farmacêutico para Compressão Direta. Quím. Nova 2012, 35, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.E.F.; Junqueira, A.M.B.; Simão, A.A.; Corrêa, A.D. Caracterização Química das Hortaliças Não-Convencionais Conhecidas como Ora-Pro-Nobis. Biosci. J. 2014, 30 (Suppl. 1), 431–439. [Google Scholar]

- Barreira, T.F.; Paula Filho, G.X.; Priore, S.E.; Santos, R.H.S.; Pinheiro-Sant’Ana, H.M. Nutrient Content in Ora-Pro-Nóbis (Pereskia aculeata Mill.): Unconventional Vegetable of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41 (Suppl. 1), 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, G.O. Desenvolvimento Tecnológico e Caracterização Físico-Química da Farinha de Carnaúba (Copernicia prunifera (Mill.) H.E. Moore); Monografia (Curso de Tecnologia em Alimentos), Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Piauí, Campus Teresina Central, 2022; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Navaf, M.; Sunooj, K.V.; Aaliya, B.; Sudheesh, C.; George, J. Physico-Chemical, Functional, Morphological, Thermal Properties and Digestibility of Talipot Palm (Corypha umbraculifera L.) Flour and Starch Grown in Malabar Region of South India. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2020, 14, 1601–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinaud, B.E.R.; Monteiro, P.L.; Pires, C.R.F.; Santos, V.F.; Kato, H.C.A.; Sousa, D.N. Elaboration and Nutritional Characterization of Enriched Food Pasta with Soybean Waste. Res. Soc. Dev. 2020, 9, e718974724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; Cilli, L.P.D.L.; Oliveira, B.E.D.; Maciel, V.B.V.; Venturini, A.C.; Yoshida, C.M.P. Nutritional Improvement of Pasta with Pereskia aculeata Miller: A Non-Conventional Edible Vegetable. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 39, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.L.; Gonçalves, V.G.O.; Maradini Filho, A.M.; Carneiro, J.C.S.; Francisco, C.L. Caracterização do Pó de Ora-Pro-Nóbis e Utilização em Massas Alimentícias. Ed. Cient. Dig. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Alcorta, A.; et al. Foods for Plant-Based Diets: Challenges and Innovations. Foods 2021, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.A.; Naseem, Z.; Wani, S.M. Development of Composite Cereal Flour Noodles and Their Technological, Antioxidant and Sensory Characterization During Storage. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 100650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernaza, M.G.; Chang, Y.K. Resistant Starch and Soy Protein Isolate in Instant Noodles Obtained by Conventional and Vacuum Frying. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2020, 23, e2018239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Formulation | Wheat Flour (%) | Pereskia Flour (%) |

Salt (%) |

Olive Oil (%) |

Egg (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC PA 1 PA 3 PA 5 PA 7 PG 1 PG 3 PG 5 PG 7 |

63 62 60 58 56 62 60 58 56a |

0 1 3 5 7 1 3 5 7 |

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 |

6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 |

30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 |

| Variáveis | Flours | |

|---|---|---|

| Pereskia aculeata | Pereskia grandifolia | |

| Water content (%) Aw Ash content (%) Proteins (%) Lipids (%) Carbohydrates (%) TEV(Kcal) L -a* b* |

5.7 ± 0.23 0.243 ± 0.005 14.2 ± 0.22 17.48 ±0.01 6.18 ± 0.31 56.44 ± 0.03 351.32 ± 0.1 14.54 ± 0.01 -0.23 ± 0.01 7.14 ± 0.01 |

4.8 ± 0.14 0.230 ± 0.005 15.9 ± 0.1 21.86 ± 0.13 8.78 ± 0.13 48.66 ± 0.1 361.08 ± 0.1 30.91 ± 0.01 -5.78 ± 0.01 29.92 ± 0.01 |

| Variables | Flours | |

|---|---|---|

| Pereskia aculeata | Pereskia grandifolia | |

| TEP ABTS DPPH Cytotoxicity DL50 |

485.61 ± 0.32 38.97 ± 1.18 21.24 ± 1.21 2417.32 ± 0.01 |

1129.59 ± 0.43 19.41 ± 0.80 15.78 ± 1.26 971.49 ± 0.01 |

| Physical parameters | Pereskia aculeata | Pereskia grandifolia |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk density (g mL-1) | 2.54±0.03 | 2.52±0.01 |

| Compacted density (g mL-1) | 4.12±0.05 | 3.71±0.55 |

| Carr Index (%) | 38.00±0.63 | 32.17±0.55 |

| Hausner Factor | 0.62±0.01 | 0.68±0.01 |

| Solubility (%) | 94.62±0.51 | 91.76±0.73 |

| Parameters | Pereskia aculeata | Pereskia grandifolia |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium (mg/g) | 23.91±0.20 | 23.6±1.35 |

| Magnesium (mg/g) | 14.32±0.21 | 22.60±1.08 |

| Potassium (mg/g) | 43.91±0.58 | 33.81±0.23 |

| Sodium (mg/g) | Nd | 7.15±0.46 |

| Copper (mg/g) | 0.02±0.0005 | 0.01±0.0003 |

| Zinc (mg/g) | 0.01±0.001 | 0.03±0.0003 |

| Iron (mg/g) | 0.13±0.02 | 0.19±0.04 |

| Manganese (mg/g) | 0.16±0.008 | 0.14±0.02 |

| Sample | Stages | T (°C) | Mass Loss (%) | Residue at 600°C (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aculeata flour | 1st | 25 – 100 | 5.73 | 42.65 |

| 2nd | 100 – 280 | 19.14 | ||

| 3rd | 280 – 349 | 16.50 | ||

| 4th | 350 – 498 | 13.63 | ||

| 5th | 498 - 600 | 2.35 | ||

| P. grandifolia flour | 1st | 25 – 100 | 5.51 | 37.26 |

| 2nd | 100 – 360 | 40.57 | ||

| 3rd | 360 – 490 | 13.74 | ||

| 4th | 490 – 600 | 1.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).