1.Introduction

Ebola virus disease (EVD), previously known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is a severe and often fatal illness in humans. The RNA viruses of the Ebola genus belong to the Filoviridae family (filoviruses). This family also includes the Marburgvirus and Cuevavirus genera. The introduction of the Ebola virus into human communities occurs through contact with the blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids of infected animals. Ebola virus disease is a highly severe and often fatal hemorrhagic fever in humans. Among the five different subtypes of the virus – Zaire, Sudan, Ivory Coast, Bundibugyo, and Reston – only the first four are pathogenic to humans. Over the years, they have caused epidemics in various African countries[

3,

4]. It is an RNA virus that primarily affects humans and primates, but is also carried by fruit bats. The Ebola virus causes a disease known as hemorrhagic fever and is transmitted through bodily fluids with an incubation period ranging from 2 to 21 days. Mortality is very high if the disease is not promptly treated, with a death rate estimated at 50-90%[

4,

5,

6]. Currently, there is no specific antiviral therapy available, although a range of treatments including blood products, immunotherapies, and pharmacological therapies are under evaluation. The primary treatment focuses on supportive care to sustain the body and alleviate symptoms, with positive effects on survival[

7,

8]. The aim of this short communication is to explore this type of infection using in silico Molecular docking technology with natural molecules targeting the Ebola virus, aiming to identify a molecule theoretically capable of inhibiting this infection. This methodology is currently well-regarded for its efficiency and rapidity, facilitating the screening of numerous molecules against a specific investigative target. This approach provides a preliminary selection of potential molecules before conducting in vitro and in vivo tests, thereby reducing time and costs associated with laboratory research[

9,

10,

11].

2.Material and Methods

- Crystal structure of Ebola virus VP24 structure protein in the postfusion conformation was taken from Protein Data Bank (PDB Code:4M0Q). Docking investigation was performed by Blind Docking methid by Autodock Vina with Pyrx program, using : Grid box Coordinates of binding Center X (-7.0401), Y( -13.5072), Z(-37.1781); size_x = 64.2683218956; size_y = 57.9251213455; size_z = 95.5103299332.

3. Results and Discussion

Ebola virus disease (EVD), previously known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is a severe and often fatal illness caused by the Ebola virus. The virus, belonging to the family Filoviridae, was first identified in 1976 near the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. While primarily affecting humans and nonhuman primates, fruit bats are considered the natural hosts of the virus[

1,

2,

3,

4].

Transmission of Ebola virus occurs through direct contact with the bodily fluids of infected animals, such as bats or primates, or through human-to-human contact with infected individuals or contaminated surfaces. The incubation period ranges from 2 to 21 days, with symptoms including fever, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, and in severe cases, internal and external bleeding[

5,

6,

7].

Currently, there is no specific antiviral treatment for EVD, and supportive care is the mainstay of management. Experimental treatments, such as monoclonal antibodies and antiviral drugs, are undergoing clinical trials. Preventive measures include early detection, isolation of suspected cases, contact tracing, safe burial practices, and vaccination efforts.

Ebola outbreaks have occurred sporadically in Central and West Africa, with the largest outbreak recorded between 2014 and 2016 in West Africa. These outbreaks have significant public health and socioeconomic impacts, necessitating rapid and coordinated response efforts to control spread and minimize the impact on affected communities[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

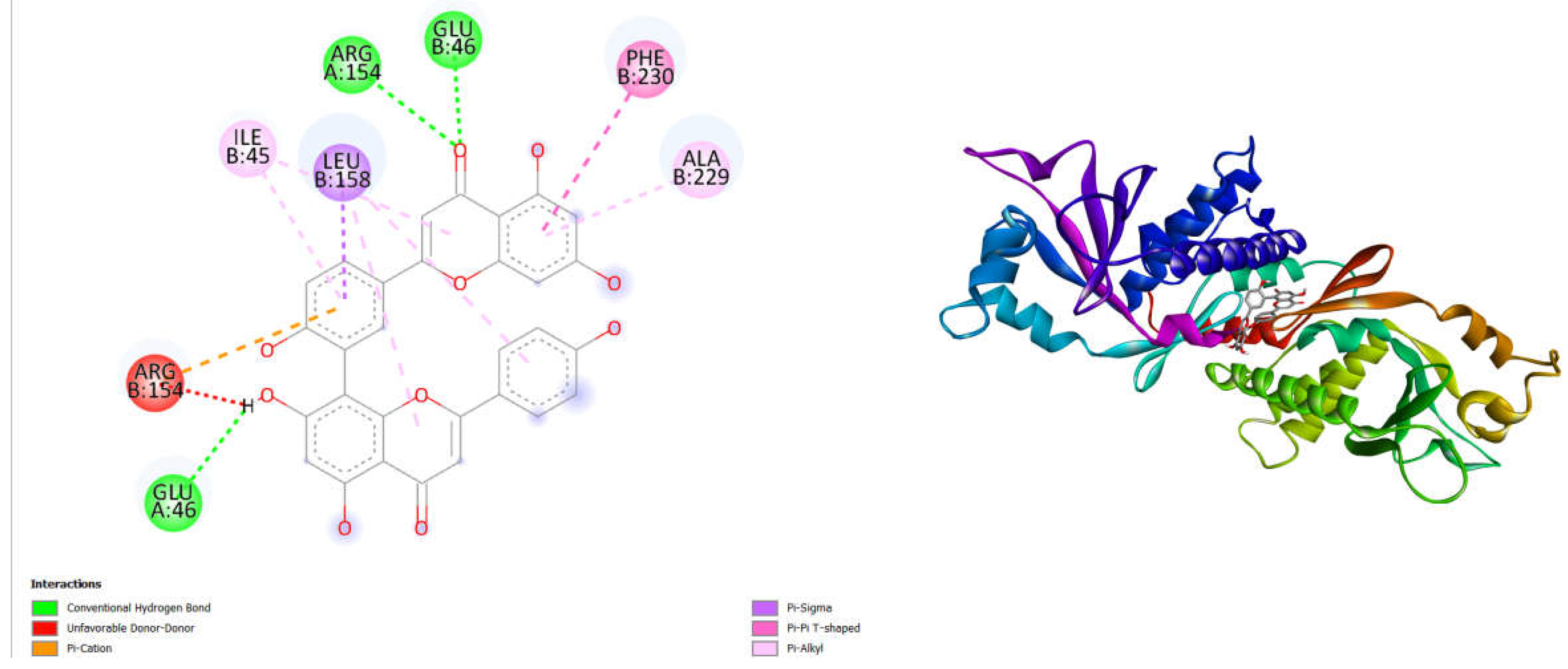

Presently, this methodology is widely recognized for its efficiency and speed, enabling the screening of numerous molecules against a specific investigative target. This process offers a preliminary selection of potential molecules prior to conducting in vitro and in vivo tests, thereby reducing time and costs associated with laboratory research. After conducting several molecular docking experiments, it was observed that Amentoflavone potentially exhibited excellent binding capability with Ebola virus, obtaining a binding energy of -10.1 kcal/mol.

Figure 1.

displays the blind docking outcomes of Structure of Crystal structure of Ebola virus VP24 structure in conjunction with docked Amentoflavone -10.1 kcal mol , within the Ligand Binding Site, as analyzed by Autodock Vina with pyrx program. On the left side, 2D diagrams illustrate the residue interactions between the protein and Amentoflavone . Meanwhile, the right side exhibits the Ligand Binding Site of the protein, highlighting the specific location of Amentoflavone .

Figure 1.

displays the blind docking outcomes of Structure of Crystal structure of Ebola virus VP24 structure in conjunction with docked Amentoflavone -10.1 kcal mol , within the Ligand Binding Site, as analyzed by Autodock Vina with pyrx program. On the left side, 2D diagrams illustrate the residue interactions between the protein and Amentoflavone . Meanwhile, the right side exhibits the Ligand Binding Site of the protein, highlighting the specific location of Amentoflavone .

Based on the docking results, Amentoflavone has shown a potential role against the Ebola virus, particularly targeting the Ebola virus VP24 structure. This suggests that Amentoflavone may possess the ability to interact with the VP24 protein, potentially inhibiting its function or disrupting its interactions with host factors essential for viral replication or pathogenesis. Further experimental studies are warranted to validate the efficacy and mechanism of action of Amentoflavone against Ebola virus infection, with the aim of developing it as a therapeutic agent for combating this deadly disease.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the docking results suggest that Amentoflavone holds promise as a potential inhibitor against the Ebola virus VP24 protein. The favorable binding affinity observed in the simulations indicates that Amentoflavone may interfere with VP24 function, thereby potentially disrupting viral replication or pathogenesis. These findings highlight the importance of further experimental studies to validate the inhibitory activity of Amentoflavone against Ebola virus infection. Additionally, elucidating the precise mechanism of action underlying Amentoflavone's antiviral effects will be crucial for its development as a therapeutic agent. Overall, this research contributes valuable insights into the potential use of natural compounds like Amentoflavone in combating Ebola virus disease and underscores the importance of continued exploration of novel antiviral strategies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Malik, S., Kishore, S., Nag, S., Dhasmana, A., Preetam, S., Mitra, O., ... & Sah, R. (2023). Ebola virus disease vaccines: development, current perspectives & challenges. Vaccines, 11(2), 268. [CrossRef]

- Letafati, A., Ardekani, O. S., Karami, H., & Soleimani, M. (2023). Ebola virus disease: A narrative review. Microbial Pathogenesis, 106213. [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, K. R., Lobb, A., & Dent, A. E. (2024). Ebola virus disease in children: epidemiology, pathogenesis, management, and prevention. Pediatric Research, 95(2), 488-495. [CrossRef]

- Letafati, A., Ardekani, O. S., Karami, H., & Soleimani, M. (2023). Ebola virus disease: A narrative review. Microbial Pathogenesis, 106213. [CrossRef]

- El Ayoubi, L. E. W., Mahmoud, O., Zakhour, J., & Kanj, S. S. (2024). Recent advances in the treatment of Ebola disease: A brief overview. Plos Pathogens, 20(3), e1012038. [CrossRef]

- Tembo, J., Simulundu, E., Changula, K., Handley, D., Gilbert, M., Chilufya, M., ... & Bates, M. (2019). Recent advances in the development and evaluation of molecular diagnostics for Ebola virus disease. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics, 19(4), 325-340. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G., Sharma, A. R., & Kim, J. C. (2024). Recent Advancements in the Therapeutic Development for Marburg Virus: Updates on Clinical Trials. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Willet, V., Dixit, D., Fisher, D., Bausch, D. G., Ogunsola, F., Khabsa, J., ... & Baller, A. (2024). Summary of WHO infection prevention and control guideline for Ebola and Marburg disease: a call for evidence based practice. bmj, 384. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Ling, M., Lin, Q., Tang, S., Wu, J., & Hu, H. (2023). Effectiveness Analysis of Multiple Initial States Simulated Annealing Algorithm, A Case Study on the Molecular Docking Tool AutoDock Vina. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics. [CrossRef]

- Ding, J., Tang, S., Mei, Z., Wang, L., Huang, Q., Hu, H.,& Wu, J. (2023). Vina-GPU 2.0: Further Accelerating AutoDock Vina and Its Derivatives with Graphics Processing Units. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 63(7), 1982-1998. [CrossRef]

- Houshmand, F., & Houshmand, S. (2023). Potentially highly effective drugs for COVID-19: Virtual screening and molecular docking study through PyRx-Vina Approach. Frontiers in Health Informatics, 12, 150.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).