1. Introduction

Tryptophan (TRP), one of the nine essential amino acids, is metabolized into several bioactive molecules, the best known of which is serotonin. However, up to 95% of TRP is transformed into kynurenine (KYN) and its breakdown products, including KYNA, via the KAT isozymes. An increase in kynurenic acid (KYNA) brain concentration is implicated in schizophrenia and other CNS disorders [

1,

2].Therefore, compounds that target the kynurenic pathway (KP) are of interest in CNS drug development.

In the human brain, KYNA is produced through KATII, making this enzyme an attractive pharmacological target [

1,

3]. Selective KATII irreversible inhibitors such as PF04859989 and BFF-122 were previously developed. PF04859989 can reduce KYNA levels by 50% in the prefrontal cortex of rats and decrease the firing activity of midbrain dopamine neurons [

1,

4]. Because BFF-122 and PF-04859989 also bind to the enzyme cofactor pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP), they have potentially significant adverse effects. This highlights the need for new inhibitors that do not have these drawbacks [

5,

6,

7].

Most enzyme inhibitors are obtained from herbal products, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenoid compounds, which are highly prevalent health-beneficial substrates in nature. These compounds play a vital role in a series of physiological and biochemical processes functioning as inhibitors of enzyme systems.

While several studies have used computational approaches to investigate novel inhibitors against KATII, we aim to identify natural compounds as potential inhibitors of this enzyme, a path less traveled in the field [

5,

8]. We now report new inhibitors of KATII through virtual screening of a small library of natural compounds. These molecules were then subjected to a thorough absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADMET) and molecular dynamic analysis. The lead compounds were evaluated for their safety profile and inhibitory activity in vitro, ensuring their usefulness for future development.

2. Results and Discussion

In the past few years, drug design using computational approaches has become a trend in theoretical chemistry and pharmaceutics. The goal is to quickly and cheaply find compounds likely to show physiological activity against selected biologically active macromolecules.

A few studies have identified safe synthetic potential molecules that are effective against KATII. The challenge is in developing reversible inhibitors for KATII [

1,

15]. In this study, we used a computational approach to find two flavonoids as novel and safe KATII inhibitors from natural compounds. Then, we tested those molecules for their inhibitory potential and cytotoxicity profile using in vitro assays.

2.1. Molecular Docking, MMGBSA and ADMET Study

Virtual screening based on molecular docking, free energy, and calculations like drug-likeness analysis are computational methods that can screen sizeable bioactive compound libraries and identify potential drug molecules. Before the docking procedure, the LigPrep module created all conformations for each ligand, which were then analyzed for virtual screening using the Glide module. For each ligand, the conformer with the lowest energy for the receptor was chosen for further docking analysis using Glide’s XP (Extra Precision) mode.

The docking procedure was validated prior to the virtual screening using XP docking of the co-crystal ligand through the Glide module for evaluating the analogy between the lowest energy state predicted by Glide and the observed binding mode of the co-crystal structure (Figure. S1). The root mean square deviation (RMSD) value, a key validation metric, between the co-crystal ligand and re-docked native ligand position is 1.473 Å. As a result, the docking procedure was validated, given that the RMSD value was less than 2.0Å [

16].

The selected molecules, herbacetin, (-)-Epicatechin, melilotoside, sakakin, and eriodictyol have shown good interactions and binding affinity scores. The lead compound, herbacetin was successfully docked with a best docking score of -8.661 kcal mol

−1 and displayed MM/GBSA binding energy of -50.30 kcal mol

−1 (

Table 1).

Herbacetin interacted with active site residues,Asn202, Ser117, Ser260, Ser262 and Lys263 via hydrogen bond interactions (

Figure 1A). The phytocompounds (-)-Epicatechin, melilotoside, sakakin, and eriodictyol also showed significant binding affinities against KATII with docking score values of -8.160 kcal mol-1, -7.918 kcal mol-1, -7.846 kcal mol-1, and -7.636kcal mol-1, respectively (

Table 1). (-)-Epicatechin exhibited hydrogen bonding with the residues Tyr233, Tyr142, Asp230 and Ser117 (

Figure 1B). Melilotoside made molecular interactions with residues Tyr233, Lys263, Asp230, Ser117, Ser260, and Arg270 through hydrogen bonding (

Figure 1C), while sakakin interacted with Tyr142, Ser117, Ser260, and Ser162 (

Figure 1D). The fifthbestmolecule, eriodictyol, showed hydrogen bonding with Tyr233, Asn202, Ser260, and Ser117 (

Figure 1E). In addition, other types of interactions were observed with the target, such as hydrophobic interactions(Figure 3).

According to the docking poses, the hits bind with key residues at the active site of KATII, such as Asn202 and Tyr142, which would normally interact with the substrate and the cofactor PLP [

7]. Furthermore, the residue Lys263 plays a key role as a catalytically essential side chain because of its interaction with PLP, which is required for KAT activity [

6].

2.2. Drug-Likeness Proprieties and ADMET Analysis

The top five molecules were selected based on docking scores, ligand-receptor interactions, and MMGBSA binding affinity compared with the standard drug, PF-04859989.

The QikProptools of Schrodinger (Release 2021-2) were used to predict drug-likeness, pharmacokinetics, and relevant details like the number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, the percentage of oral absorption, the partition coefficient (QP log Po/w), the proprieties of Lipinski’s rule of five, and Caco2 cellular permeability. The overall human oral absorption percentage ranged from 36.716 to 61.197 % for the studied molecules and the reference inhibitor. Concomitantly, these molecules showed a good partition coefficient (QP log Po/w) values, ranging from -0.814 to 0.416 (

Table 2).

The blood/brain coefficients (Q log B/B) were within an acceptable range, between -2.318 and -0.325. The Caco-2 permeability factor (in nm s−1) ranged from 5.200.141 to 98.591, indicating that the studied molecules had good cell membrane penetration (

Table 2).

The pharmacokinetic parameters fell within the acceptable range specified for human use, except melilotoside, which showed a poor Caco-2 permeability value, as shown in

Table 2. Furthermore, the compounds are expected to satisfy Lipinski’s criteria for drug-likeness, with the majority falling within the range of the rule of five, and therefore are potentially suitable for therapeutic development.

The toxicity profile of the top co”poun’s was further investigated using the ProToxIII online tool, and their toxicity parameters, including LD50 value, toxicity class, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, immunotoxicity, and mutagenicity, were evaluated (

Table 3). Except for herbacetin,which exhibited weak (likely insignificant) mutagenic activity compared I reference inhibitor, none of the phytochemicals identified were anticipated to have hepatotoxic, carcinogenic, cytotoxic, immunotoxic, or mutagenic effects.

2.3. Induced Fit Docking Analysis

Induced fit docking (IFD) is undeniably one of drug design’s most complex and crucial aspects. In this study, IFD was conducted on the two top molecules, the main compounds, and PF-04859989 was used as a reference inhibitor. The results showed that herbacetin showed the best IFD score of -843.89 kcal mol-1, followed by (-)-Epicatechin, with an IFD score of -842.20 kcal mol-1.The IFD scores of the two previous compounds are greater when compared to that of PF-04859989, which recorded an IFD score of -839.26 kcal mol-1.

The conformations generated from t”e IF’ exhibited minimal differences compared to the docked poses achieved through rigid receptor docking. On the other hand, new interactions were created or eliminated based on the interactions previously observed during XP docking. Some ligand interactions remained consistent after IFD docking studies. For the herbacetin compound, a new hydrogen bond was formed with Ser267, but the hydrogen bond with Ser260 was lost after IFD. Hydrophobic interactions and other hydrogen bonds were keptas in XP docking (

Figure 4A). (-)-Epicatechin showed new hydrogen bonds with Asn202, Ser263, Arg270 and Arg399, hydrophobic interactions with Met354 and positive charged interactions with Arg399. Concomitantly, this compound lost its hydrogen bond with Asp230 and negatively charged interaction with the same residue (

Figure 4B). The standard inhibitor PF-04859989 showed different interaction patterns than XP docking, two new hydrogen bonds with Ser117 and Gln118, and a positively charged amino acid interaction with Arg399 (

Figure 4C). Based on these findings, the two lead compounds have a more potent inhibitory effect than PF-04859989, which indicates a better interaction with the binding site of KATII.

2.4. Molecular Dynamic Analysis

MD simulation of the top two docked complexes, herbacetin and (-)-epicatechin, and the standard drug (PF-04859989) during a 100 ns time scale was performed in the current study to check for stability in the active site of KATII. The expected binding mode and the types of interactions were investigated using Glide XP docking. The root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and protein-ligand contacts were used to evaluate the molecular dynamic simulations.

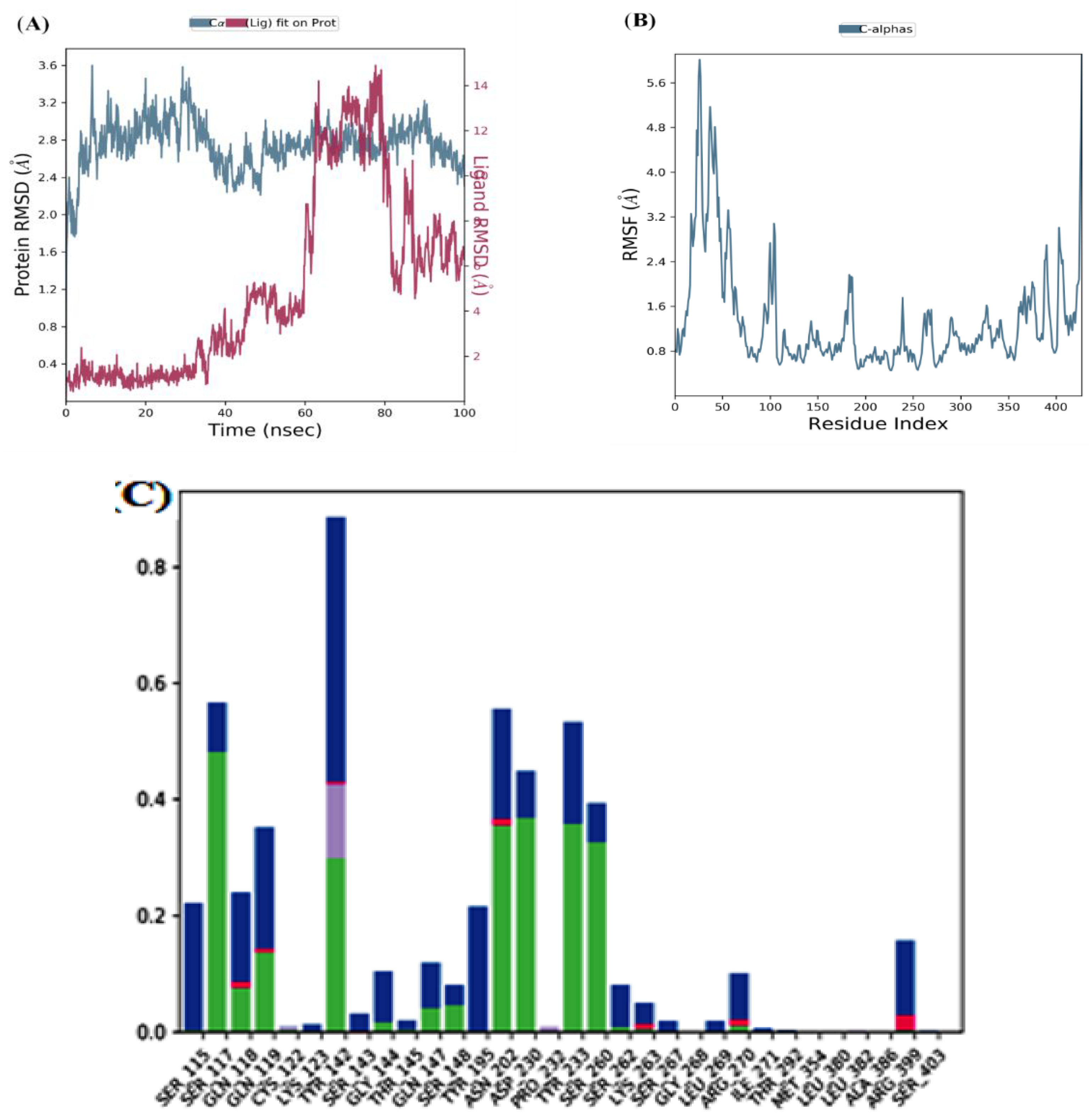

The RMSD is used to investigate the conformational stability of a structure during simulation by evaluating the average change in atom displacement compared to a reference.

After interpreting the RMSD graph, we can confidently predict that the herbacetin-KATII complex will exhibit minimal RMSD fluctuations throughout the simulation. This stability is cleargiven that after 20 ns, the complex remained stable until the end of the simulation, with a maximum value of 2Å(

Figure 5A), well within the acceptable range of fluctuations (1-3 Å). This insight into the stable behavior of the herbacetin-KATII complex provides a significant contribution to our understanding of protein-ligand interactions.

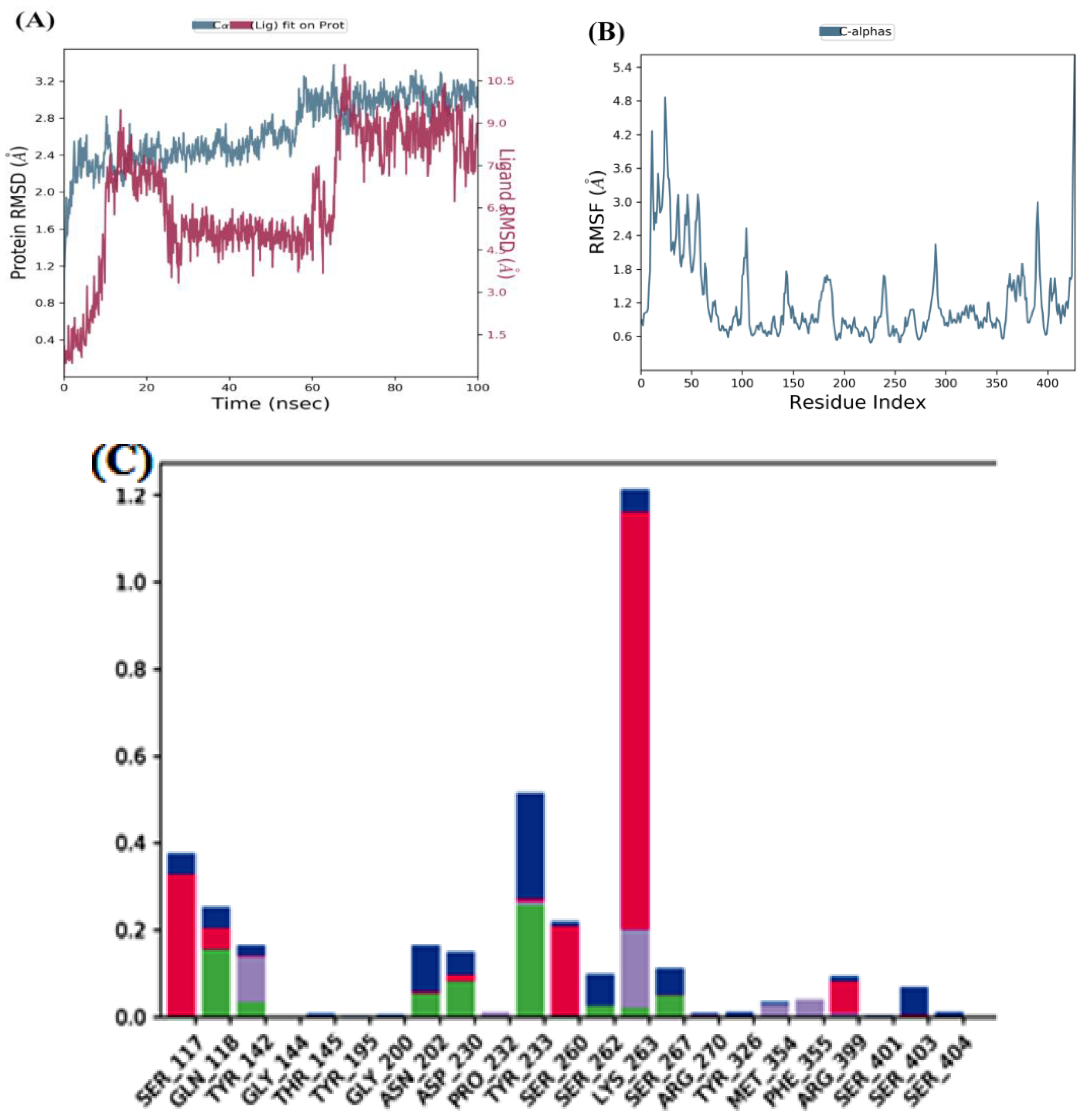

The lower fluctuations seen in the(-)-Epicatechin-KATII complex’s RMSD values show a stable behavior of the conformations during the simulation. Despite an initial RMSD value of 4 Å and ~ 12Å between 0 and 60 ns, the complex’s stability becomes evident after 85 ns (

Figure 6A), with both the receptor and ligand RMSD observed in a stable format.

The RMSD plot of the standard PF-04859989-KATII complex showed fluctuations of 1.6 -5 Å. The complex RMSD stabilized after 60 ns and remained consistent until the end of the simulation, with a slight divergence seen near the end, i.e., 95 ns within the permissible range of 1-3 Å (

Figure 7A).

The RMSF analyses were performed to analyze the flexibility per residue using the docked complex structures.

Figure 5B, and

Figure 6B show that the N and C terminals fluctuate more than any other protein part. Peaks show most protein fluctuations; the lower the fluctuations, the more stable the complexes are during simulation. Low fluctuations show the system is in equilibrium [

16,

17].

RMSF was calculated for KATII and two potential drug candidates. As shown in

Figure 5B and

Figure 6B, the RMSF did not fluctuate much over the 100 ns simulation period, and the average RMSF values were held constant for all complexes.

Investigation of MD showed that the lead compound herbacetin displayed hydrogen bonding with TYR 233, ASN 202, and ASP 230 residues (

Figure 5C). In turn, hydrophobic contacts between the ligand and Tyr142, Ser260, and Arg 399 are seen. The simulation also revealed binding interactions between –(-) Epicatechin and the active site residues of KATII, hydrogen bonding with Ser117, Tyr142, Tyr 233; Asn 202, and ASP 230, and hydrophobic interactions with Ser115 and Tyr195 (

Figure 6C).

The PF-04859989-KATII complex exhibited hydrogen bonds with Asp230 and Tyr233 and one ionic bond with Ser117 (

Figure 7C).

2.5. DFT calculation

The frontier molecular orbitals (

Figure S3) are essential in understanding molecules’ chemical reactivity and stability. These orbitals are commonly used to collect data on optical and electrical properties, conduct pharmacological research, and better understand the biological mechanisms of bioactive compounds.

The difference between the ELUMO and EHOMO (ΔE = E LUMO – E HOMO) is correlated with the reactivity and stability of the molecules. The lower HOMO and LUMO energy gaps indicate that the molecule has strong chemical reactivity, biological properties, and polarizability.

As shown in

Table 4, the lead compound, herbacetin had the lowest energy gap with a ΔE value of 3.7283 (Ev), with low chemical hardness (1.8711 Ev) and displayed the highest softness value of 0.5344 (Ev). (-)-Epicatechin had the maximum energy gap for all the selected compounds with a value of 5.7006 (Ev). The latter exhibited chemical hardness and chemical softness values of 2.8503 (Ev) and 0.3508 (Ev-

1), respectively (

Table 4). The higher the value of the electrophilicity index of the mentioned molecule, the greater its binding capacity with biomolecules [

18,

19]. The electrophilicity index’s calculated value for herbacetin was 3.7144 Ev. Hence, it was the strongest electrophile, followed by control molecule PF-04859989 with a value of 2.1514 Ev, while (-)-Epicatechin had the lowest value of 1.5362 Ev (

Table 4).

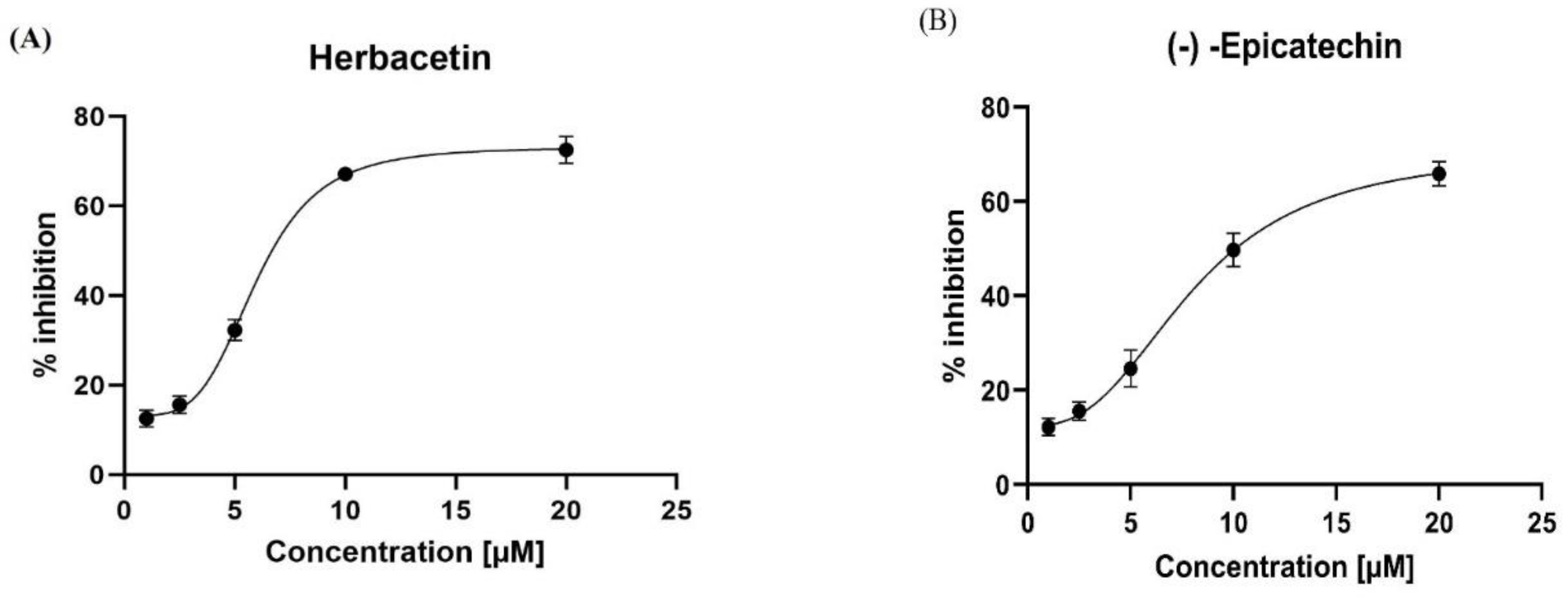

2.5. In Vitro Inhibition Assay of KATII

In the present study, we assessed half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) for the two best molecules, which are the lead compounds. Herbacetin was a good inhibitor of KATII at the concentrations used, displayed good inhibitory capacity, and had an IC50 of 5.98 ± 0.18 µM (

Figure 8A). (-)-Epicatechin also inhibited KAT-II effectively, with an IC50 of 8.76 ± 0.76 µM (Figure. 8B). Moreover, we compared the inhibitory characteristics of these compounds with those of PF-04859989, which bind PLP irreversibly (

Table S1). It was also concluded that herbacetin and (-)-Epicatechin are reversible inhibition. This reversibility was confirmed by changing the PLP concentration in the reaction mixture, leading to decreased inhibition by the studied compounds as the PLP concentration increased, indicating competition [

6].

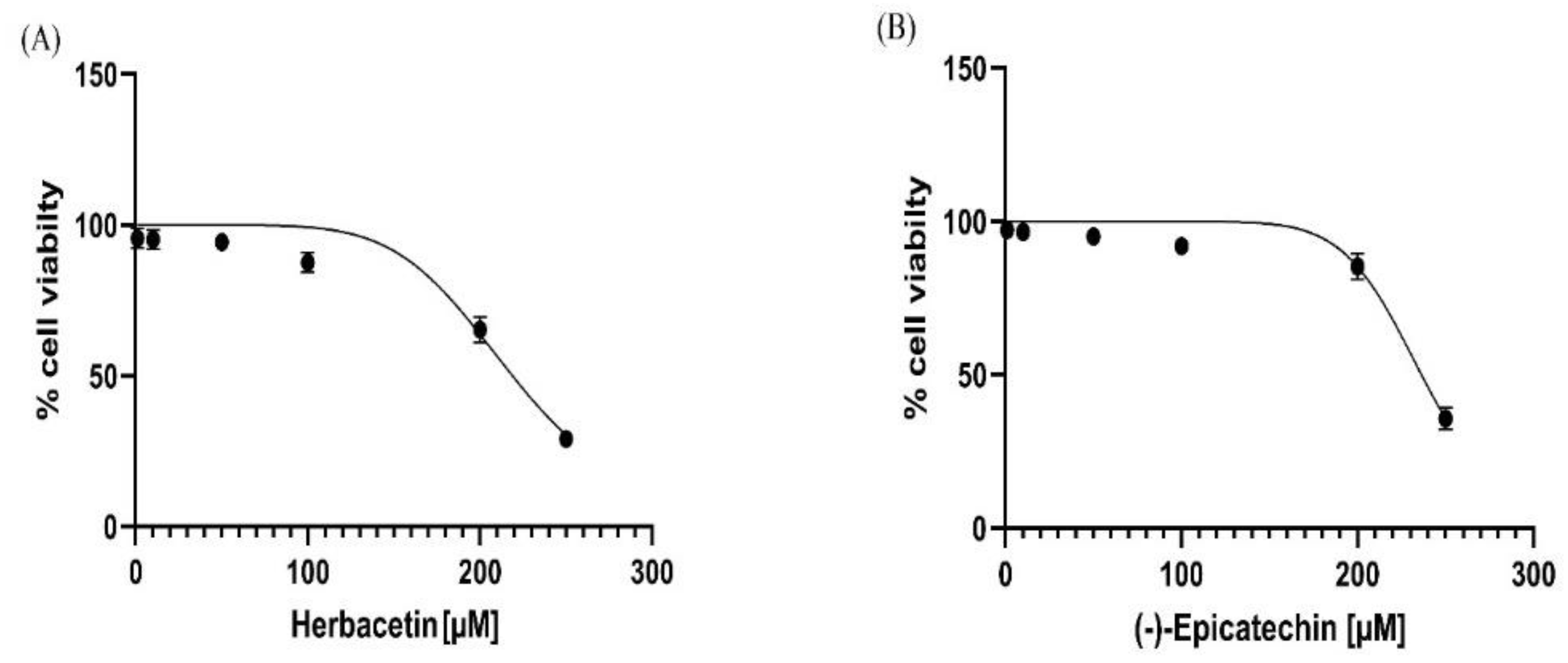

2.6. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

The MTT assay was used to assess cell viability in the presence of the experimental drug. The top two compounds were evaluated for in vitro hepatotoxicity against human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. These cells were exposed to a solution containing either herbacetin or (-) -Epicatechin at various concentrations (1-250 µM) for 72 h according to the standard protocol. The results showed that the earlier compounds had weak cytotoxic activity against the HepG2 cell line, which was seen only at higher concentrations (> 200 µM)(

Figure 9). It was noted that herbacetin and (-) -Epicatechin exhibits a low cell growth inhibition impact, with IC50 values of 218.90 µM ± 4.53 and 236.40 ± 2.53, respectively.

Ultimately, the in silico and in vitro test results suggest potential interactions between the studied compounds and the target protein but require extensive experimental validation to confirm their pharmacological relevance. These computational findings serve as hypotheses rather than definitive evidence of therapeutic efficacy. To go from computer simulations to clinically useful KAT II inhibitors, in vivo studies are needed to check the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

The recombinant KATII protein and buffers were bought from R&D Systems, Bio-Techne. HepG2 cell line, solvents and other chemicals, including herbacetin, (-)-Epicatechin and PF-04859989, were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. LLC (Germany).

3.2. Computational Methods

3.2.1. Protein Preparation and Receptor Grid Generation

The crystal structure of human KATII (resolution: 2.89 Å; PDB ID: 4GDY) was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB); the protein sequence length is 439 amino acids, linked with a small molecule inhibitor (co-crystal ligand). Prior to molecular docking, Protein Preparation Wizard in Maestro Schrödinger was used to optimize the KATII structure; the PLP cofactor was removed because it was suspected of competing with the active site ligands [

6]. Also, water molecules not involved in these interactions were removed, and hydrogen atoms were added. The partial charges were assigned using the OPLS-3e force field in Maestro.

The position of the existing (co-crystal ligand) inhibitor in the PDB structure determined the active site and receptor grid generation was implemented with the site’s default settings.

3.2.2. Ligands Preparation

Before molecular docking, we filtered all compounds using the Lipinski and Veber rule [

9,

10]; those that did not follow this criterion and contained reactive functional groups were removed. The Ligprep module in Maestro Schrödinger was executed to prepare the ligands. The ionization states at pH 7.0 ± 2.0 and tautomeric forms of each moleculewere generated.

3.2.3. Molecular Docking Based Virtual Screening

The selected moleculeswere screened against KATII using a virtual screening workflow with default parameters using the Glide program of Schrödinger. All phytocompounds were docked with Glide XP (extra precision) mode. Then, the five top moleculesretaining only best scoring states were obtained as output and selected for further analysis based on docking score and molecular interactions with the target protein. Finally, pose viewer was used to analyze the interactions of various ligand and protein complexes.

3.2.4. MMGBSA Calculation

The MMGBSA (molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area) technique was used as a post-docking validation to provide the relative binding free energy (ΔG bind) for each docked pose of ligand that were taken as inputs for the energy minimization of the protein-ligand complexes. The binding free energy (ΔGbind) of the six best molecules (hits) was estimated according to the following equation:

ΔG (binding affinity) = ΔG (solvation energy) + ΔE (minimized energy) + ΔG (surface area energies)

Where ΔG (solvation energy) is the difference between the solvation energy of the GBSA of the inhibitor-KATII complex and the sum of the solvation energies for unligated KATII and the respective inhibitor. ΔE (minimized energy) is the difference in energy between the complex structure and the sum of the energies of the KATII with and without inhibitor, and (ΔG Surface area) is the difference in the energy of the surface area for the inhibitor-KATII complex and the sum of the surface area energies for the inhibitor and unbound protein.

3.2.5. Drug Likeness Predictions and ADMET Analysis

The QuikPro module of the Schrodinger suite (Schrodinger, LLC, New York, 2021.2) was used to analyze ADME and drug-likeness properties of selected molecules along with the standard inhibitor by checking for any violation of Lipinski’s rule of five (ROF) and several pharmacological parameters including human oral absorption, predicted octanol/water partition coefficient. The toxicity parameters were estimated via the ProTox-II web tool(

https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/).

3.2.6. Induced Fit Docking (IFD)

The IFD method was used to effectively simulate the flexibility of the receptor and the ligand using the induced fit docking function in Maestro v12.8. (Schrodinger, LLC). Removing false negative bonds almost produces an exact binding state comparable to biological ligand-receptor binding.

Based on the on the XP-docking score, ligand interactions and binding free energy, The two top molecules, were passed through the induced fit docking (IFD) module in the Schrodinger suite to improve docking accuracy and allowconformationalflexibility of ligands and proteins, which is restricted in docking studies.

A standard protocol in the first step of IFD was employed to create the box in the centroid of the ligand at the 0X1 native ligand and 4GDY receptor binding site, then generate for each ligand up to 20 docked poses for refinement by Prime within 5, with receptor and ligand van der Waals radii of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively. After prime side-chain prediction and minimization, the final docked poses for each ligand were returned to Glide SP for redocking.

3.2.7. Molecular Dynamic (MD)

The binding stability of protein-ligand docking complexes is investigated using MD simulation, which also provides information on intermolecular interactions within a reference time. Protein Wizard was used to prepare the protein-ligand complex structure of KATII and the three top candidate molecules for MD simulation. Desmond-2018 version was used to conduct 100 ns simulations using the OPLS force field. The complex protein-ligand interaction was placed in an SPC (single point charge) water box shape under orthorhombic periodic boundary conditions for a 10 Å buffer region. The System Builder tool was used to prepare the buffer, which was then neutralized by adding 0.15 M NaCl ions. Also, the NPT ensemble was applied to maintain the system’s temperature (K) and pressure (bar) at 300 K and 1.01325 bar, respectively, throughout the MD experiment.

3.2.8. DFT Calculations

The DFT method is crucial for examining the relationship between the geometry and electrical characteristics of bioactive molecules to evaluate the molecular properties of the selected molecules by the Jaguar program. We chose 6-31G** as the basis set and B3LYP as the level of theory as it is the most used basis set for small organic molecules. The energy calculation was performed with a Poisson Boltzmann Finite (PBF) solvation state in which water was selected as a solvent [

11,

12].

DFT calculations involving HOMO and LUMO energies, and numerous other parameters, such as chemical hardness, softness, electronegativity, and electrophilicity, were performed on hebacetin, (-)-Epicatechin and PF-04859989 (reference inhibitor) using their optimized structures.

3.2. In Vitro Inhibition Assay of KATII

The KATII inhibition test was conducted following the method reported by [

13], with a slight modification. We conducted the essay on the two best molecules using a microplate fluorescent test for kynurenine aminotransferase. The reaction mixture (20 μL) contained 20 nM recombinant human KATII, 1 mM of L-KYN, 0.3 mM of L-α-aminoadipic acid (AAD), 50 µM of α-ketoglutaric acid, 3 mM of NAD+ and 88 µg/mL of glutamic dehydrogenase.

The inhibitory activity of the two molecules, herbacetin and (-) -Epicatechin, was tested at six different concentrations after being diluted in DMSO. These moleculeswere pre-incubated with the enzyme for 30 min at room temperature. This was done in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.5 containing 5 µM of PLP. After that, kinetic data was collected over 30 min. The percentage of inhibition was determined for each inhibitor concentration, and IC50 value was calculated through non-linear regression (four parameters). Validation of the assay was done using of the reference inhibitor PF-04859989.

The percentage of inhibition was calculated at each concentration of inhibitor, and the IC50 value was determined using non-linear regression (four parameters). The reference inhibitor PF-04859989 was used to validate the assay, and its IC50 (IC50 = 27.91 ± 1.83nM) was consistent with the value reported by [

8].

3.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

MTT assay was conducted to assess cell cytotoxicity using the method described by [

14], with slight modifications. The HepG2 cell line was obtained from ECACC (European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, Sigma-Aldrich (Germany)). Initially, the cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 250 μg/mL fungizone, in a humidified incubator at standard conditions of temperature (37 ˚C), CO2 (5%). Cells were rinsed with 2.5 mL PBS and treated with 1.5 mL 0.25% trypsin-EDTA for 5 min at 37 °C. Cell pellets were collected by spinning at 1500 rpm for 6 min at 4 °C, then resuspending in fresh culture media and replacing the supernatant; the culture medium was refreshed with fresh media every other day. Three wells were used in the 96-well plates for each molecule, with repetitions carried out three times.

Cell viability was determined using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) tetrazolium reduction assay. The cells were dispensed at 8000 cells/well in 0.1 mL medium. Cells were treated with herbacetin and (-) -Epicatechin (dissolved in DMSO) with variable concentrations from 1-250 µM and incubated at 37 for 72h.Then, 10 microliters of MTT solution at a concentration of 5 mg/mL were introduced into every well, followed by an incubation of the plates at 37 ˚C for a duration of 4 h. The reduced MTT’s absorbancewas recorded at 570 nm using a VERSA max microplate reader.

Cell viability data of the studied moleculeswas plotted against concentrations of derivatives, and The IC50 values were determined graphically using the curve-fitting algorithm.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted utilizing GraphPad Prism 8.4.0. Experimental procedures were performed in triplicate (n = 3). The results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

4. Conclusions

This study has identified herbacetin and (-)-Epicatechin as new natural inhibitors of KATII. Both inhibitors showed good binding affinity and stability in the computational methods. The findings also revealed acceptable ADME properties and a safe molecule toxicity profile. Furthermore, the in vitro assays showed potent inhibitory activity against KATII and a non-toxic effect on cell viability and proliferation. We consider these compounds excellent candidates for the effective treatment of schizophrenia, but further preclinical trials are needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: validation of docking study; Figure S2: 2D structure of lead compounds and the standard inhibitor; Figure S3: HOMO and LUMO plot of (A): herbacetin, (B) :(-)-Epicatechin and (C): PF-04859989; Table S1: Inhibition type of herbacetin, (-)-Epicatechin and PF-04859989 on KAT-II.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.; methodology, A.B.; software, R.R.; validation, R.R., L.J. and A.B.; formal analysis, A.B. and L.J.; resources, A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R., A.B. and L.J.; writing—review and editing, L.J, R.R, and A.B.; visualization, L.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Barazorda-Ccahuana, H.L.; Zevallos-Delgado, C.; Valencia, D.E.; B. Gómez. Molecular dynamics simulation of kynurenine aminotransferase type II with nicotine as a ligand: A possible biochemical role of nicotine in schizophrenia. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, A.F.; Vasupanrajit, A.; Tunvirachaisakul, C.; Al-Hakeim, H.K.; Solmi, M.; Verkerk, R.; Maes, M. The tryptophan catabolite or kynurenine pathway in schizophrenia: meta-analysis reveals dissociations between central, serum, and plasma compartments. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 3679–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotina, L.; Seo, S.H.; Kim, C.W.; Lim, S.M.; Pae, A.N. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening of novel competitive inhibitors of the neurodegenerative disease target Kynurenine-3-Monooxygenase. Molecules 2021, 26, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linderholm, K.R.; Alm, M.T.; Larsson, M.K.; Olsson, S.K.; Goiny, M.; Hajos, M.; Erhardt, Engberg, S.G. Inhibition of kynurenine aminotransferase II reduces activity of midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuropharmacology 2016, 102, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dounay, A.B.; Anderson, M.; Bechle, B.M. Campbell, B.M.; Claffey, M.M.; Evdokimov, A.; Verhoest, P.R. Discovery of brain-penetrant, irreversible kynurenine aminotransferase II inhibitors for schizophrenia. ACS Med. Chem. Lett, 2012, 3, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickrama, G.S.; Nematollahi, A.; Sun, G.; Gorrell, M.D.; Church, W.B. Inhibition of human kynurenine aminotransferase isozymes by estrogen and its derivatives. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 17559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorbakhsh, A.; Hosseininezhadian Koushki, E.; Farshadfar, C.; Ardalan, N. Designing a natural inhibitor against human kynurenine aminotransferase type II and a comparison with PF-04859989: a computational effort against schizophrenia. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2021, 40, 7038–7051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maryška, M.; L. Svobodová, L.; Dehaen, W.; Hrabinová, M.; Rumlová, M.; Soukup, O.; Kuchař, M. Heterocyclic cathinones as inhibitors of kynurenine aminotransferase II, design, synthesis, and evaluation. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods, 2000, 44, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.Y.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbadwi, F.A.; Khairy, E.A.; Alsamani, F.O.; Mahadi, M.A.; Abdalrahman, S.E.; Ahmed, Z.A.M.; Alzain, A.A. Identification of novel transmembrane Protease Serine Type 2 drug candidates for COVID-19 using computational studies. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2021, 26, 100725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzain, A.A.; Elbadwi, F.A.; Alsamani, F.O. Discovery of novel TMPRSS2 inhibitors for COVID-19 using in silico fragment-based drug design, molecular docking, molecular dynamics, and quantum mechanics studies. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2022, 29, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Kopcho, L.; Ghosh, K.; Witmer, M.; Parker, M.; Gupta, S.; Abell, L.M. Development of a Rapid Fire mass spectrometry assay and a fluorescence assay for the discovery of kynurenine aminotransferase II inhibitors to treat central nervous system disorders. Anal. Biochem 2016, 501, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fettach, S.; Thari, F.Z.; Hafidi, Z.; Karrouchi, K.; Bouathmany, K.; Cherrah, Y.; Faouzi, M.E.A. Biological, toxicological and molecular docking evaluations of isoxazoline-thiazolidine-2, 4-dione analogues as new class of anti-hyperglycemic agents. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn 2023, 41, 1072–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, Y.; Fujigaki, H.; Kato, K.; Yamazaki, K.; Fujigaki, S.; Kunisawa, K.; Saito, K. Selective and competitive inhibition of kynurenine aminotransferase 2 by glycyrrhizic acid and its analogues. Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 10243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebai, R.; Carmena-Bargueño, M.; Toumi, M.E.; Derardja, I.; Jasmin, L.; Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Boudah, A. Identification of potent inhibitors of kynurenine-3-monooxygenase from natural products: In silico and in vitro approaches. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, S.; Das, S.; Iqubal, A.; Ahmed, B. Synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular dynamics studies of oxadiazine derivatives as potential anti-hepatotoxic agents. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 9974–9991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyar, S.; Şen, T.; Özmen, Ü.Ö.; Alyar, H.; Adem, S.; Şen, C. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterizations, enzyme inhibition, molecular docking study and DFT calculations of new Schiff bases of sulfa drugs. J. Mol. Struct 2019, 1185, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumit, M.A.; Pal, T.K.; Alam, M.A.; Islam, M.A.A.A.A.; Paul, S.; Sheikh, M.C. DFT studies on vibrational and electronic spectra, HOMO–LUMO, MEP, HOMA, NBO and molecular docking analysis of benzyl-3-N-(2, 4, 5-trimethoxyphenylmethylene) hydrazinecarbodithioate. J. Mol. Struct 2020, 1220, 128715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

2D and 3D interaction of the lead molecules and the standard inhibitor with KATII binding site residues; (A): Herbacetin, (B): (-)-Epicatechin, (C):Melilotoside, (D): Sakakin, I: Eriodictyol, (F): PF-04859989.

Figure 1.

2D and 3D interaction of the lead molecules and the standard inhibitor with KATII binding site residues; (A): Herbacetin, (B): (-)-Epicatechin, (C):Melilotoside, (D): Sakakin, I: Eriodictyol, (F): PF-04859989.

Figure 5.

MD simulation for the herbacetin–KATII complex, (A) the RMSD plot of the Herbacetin-KATII complex, (B) RMSF of the Herbacetin-KATII complex, (C) histogram of the herbacetin-KATII complex.

Figure 5.

MD simulation for the herbacetin–KATII complex, (A) the RMSD plot of the Herbacetin-KATII complex, (B) RMSF of the Herbacetin-KATII complex, (C) histogram of the herbacetin-KATII complex.

Figure 6.

MD simulation for the (-)-Epicatechin-KATII complex, (A) the RMSD plot of the (-)-Epicatechin-KATII complex, (B) RMSF of the (-)-Epicatechin-KATII complex, (C) histogram of the (-)-Epicatechin-KATII complex.

Figure 6.

MD simulation for the (-)-Epicatechin-KATII complex, (A) the RMSD plot of the (-)-Epicatechin-KATII complex, (B) RMSF of the (-)-Epicatechin-KATII complex, (C) histogram of the (-)-Epicatechin-KATII complex.

Figure 7.

MD simulation for the PF-04859989-KATII complex, (A) the RMSD plot of the PF-04859989-KATII complex, (B) RMSF of the PF-04859989-KATII complex, (C) histogram of the PF-04859989-KATII complex.

Figure 7.

MD simulation for the PF-04859989-KATII complex, (A) the RMSD plot of the PF-04859989-KATII complex, (B) RMSF of the PF-04859989-KATII complex, (C) histogram of the PF-04859989-KATII complex.

Figure 8.

Inhibitory activity of (A): herbacetin and (B): (-)-Epicatechin compounds in a dose-dependent manner. All experiments were performed in triplicate using GraphPad Prism v8.4.0.

Figure 8.

Inhibitory activity of (A): herbacetin and (B): (-)-Epicatechin compounds in a dose-dependent manner. All experiments were performed in triplicate using GraphPad Prism v8.4.0.

Figure 9.

Cell viability (%) of HepG2 cells, measured by the MTT assay, after 72 h exposure to (A): herbacetin and (B): (-)-Epicatechin compounds.

Figure 9.

Cell viability (%) of HepG2 cells, measured by the MTT assay, after 72 h exposure to (A): herbacetin and (B): (-)-Epicatechin compounds.

Table 1.

The top five hits from molecular docking along with their structure, Glide docking score and MMGBSA ΔG, number of H-bonds and interaction with essential amino acids of active site.

Table 1.

The top five hits from molecular docking along with their structure, Glide docking score and MMGBSA ΔG, number of H-bonds and interaction with essential amino acids of active site.

| Compounds |

Docking score (kcal mol−1) |

Glide emodel(kcal mol−1) |

MMGBSA

ΔG Bind

(kcal mol−1) |

Number of

H-bond

formation |

Amino acid interactions and H-bond distance (Å) |

| Herbacetin |

-8.66 |

-44.95 |

-50.30 |

5 |

Asn202 and Ser117 (3.0 Å and 2.01Å)

Ser260 and Ser262 (1.98Å and 2.01 Å)

Lys263 (2.54 Å) |

| (-)-Epicatechin |

-8.16 |

-39.32 |

-51.35 |

4 |

Tyr233 and Tyr142 (1.82Å and 2.0 Å)

Asp230 and Ser117 (1.93 Å and 2.02 Å) |

| Melilotoside |

-7.91 |

-51.41 |

-34.34 |

6 |

Tyr233, Lys263 (1.89 and 2.74 Å)

Asp230 and Ser117 (1.77Åand 2.21Å)

Ser260 and Arg270 (1.99 and 1.73Å ) |

| Sakakin |

-7.84 |

-44.76 |

-49.51 |

4 |

Tyr142 and Ser117 (2.12Åand 1.96 Å)

Ser260 and Ser262 (2.07 Å and 1.79 Å)

|

| Eriodictyol |

-7.63 |

-42.53 |

-51.33 |

4 |

Tyr233 and Asn202 (2.02Åand 2.09 Å)

Ser260 and Ser117 (2.33 Å and 2.02 Å)

|

PF-04859989

(reference inhibitor) |

-7.12 |

-28.88 |

-38.41 |

3 |

Tyr233 and Asn202 (2.04 Å and2.73 Å)

Asp230 (1.81 Å)

|

Table 2.

ADME properties of the top five molecules.

Table 2.

ADME properties of the top five molecules.

| Parameters |

Herbacetin |

(-) -Epicatechin |

Melilotoside |

Sakakin |

Eriodictyol |

PF-04859989 |

| HB donor |

4.000 |

5.000 |

5.000 |

5.000 |

3.000 |

3.000 |

| HB acceptor |

5.250 |

5.450 |

11.250 |

10.000 |

4.750 |

5.2000 |

| % of human oral absorption |

53.100 |

61.197 |

36.716 |

56.651 |

62.522 |

59.55 |

| QP log P0/w |

0.416 |

0.454 |

-0.520 |

-0.814 |

0.875 |

-0.525 |

| QplogS |

-2.846 |

-2.518 |

-1.886 |

-1.751 |

-3.930 |

-0.233 |

| QPPCaco |

27.141 |

58.241 |

5.200 |

84.334 |

50.276 |

98.591 |

| QP log B/B |

-2.318 |

-1.815 |

-2.682 |

-1.866 |

-1.797 |

-0.325 |

| Rule of five |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 3.

Toxicity parameters prediction of the lead compounds.

Table 3.

Toxicity parameters prediction of the lead compounds.

| Parameters |

Herbacetin |

(-) -Epicatechin |

Melilotoside |

Sakakin |

Eriodictyol |

PF-04859989 |

LD50

(mg/kg)

|

3919 |

10000 |

1500 |

1380 |

2000 |

500 |

| Prediction class |

Class 5 |

Class 6 |

Class 4 |

Class 4 |

Class 4 |

Class 4 |

| Hepatotoxicity |

Prediction |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

| Probability |

0.69 |

0.72 |

0.82 |

0.92 |

0.67 |

0.53 |

| Neurotoxicity |

Prediction |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Active |

| Probability |

0.89 |

0.90 |

0.88 |

0.92 |

0.88 |

0.57 |

| Immunotoxicity |

Prediction |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Active |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

| Probability |

0.92 |

0.96 |

0.56 |

0.96 |

0.71 |

0.99 |

| Mutagenicity |

Prediction |

Active |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Inactive |

Active |

| Probability |

0.51 |

0.55 |

0.78 |

0.76 |

0.59 |

0.62 |

| Prediction accuracy |

70.97 % |

100 % |

69.26 % |

69.26 % |

69.26% |

68.07 % |

Table 4.

Molecular proprieties of the two lead compounds and the standard inhibitor.

Table 4.

Molecular proprieties of the two lead compounds and the standard inhibitor.

| Parameters |

Herbacetin |

(-)-Epicatechin |

PF-04859989 |

| HOMO Energy (Ev) |

-5.6064 |

-5.8096 |

-5.9566 |

| LUMO Energy (Ev) |

-1.8781 |

-0.1090 |

-0.7422 |

| Energy gap (ΔE) (Ev) |

3.7283 |

5.7006 |

5.2144 |

Electronegativity

(χ) (Ev) |

3.7422 |

2.9593 |

3.3494 |

Chemicalpotential

(µ) (Ev) |

-3.7422 |

-2.9593 |

-3.3494 |

| Global hardness (Ƞ) (Ev) |

1.8711 |

2.8503 |

2.6072 |

| Global softness (S) (Ev)−1

|

0.5344 |

0.3508 |

0.3835 |

Global Electrophilicity index

(ω) (Ev) |

3.7144 |

1.5362 |

2.1514 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).