Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by distinctive motor and non-motor features (Ye et al., 2023). It is currently the second most prevalent neurological disease globally. According to the World Health Organization, the number of individuals with PD has doubled over the past 25 years, reaching over 8.5 million cases in 2019 with an expected projection of 20 million cases by 2050 (WHO, 2023). The average number of PD cases per 100,000 people between the ages of 40 and 80 is estimated to be approximately 379 with a higher prevalence in males (Pringsheim, 2014). PD is pathologically diagnosed by the presence of Lewy bodies which contains alpha-synuclein aggregates, and the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain substansia nigra, leading to motor symptoms such as tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia (Ye et al., 2023). Although the precise cause of Parkinson's disease is still unknown, increasing evidence points to a complex interaction of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors in its development (Ye et al., 2023).

Currently, the available treatment options for PD fail to address the underlying causes of the disease. These treatments merely seem to manage the symptoms associated with PD (Perdigão et al., 2023). Also, severe side effects are related to available chemotherapeutic options such as L-Dopa and anticholinergics (Bhusal, 2023). In recent years, natural phytochemicals have become a promising option for managing Parkinson's disease. Amongst the phytochemicals, phenolic compounds have been most extensively studied for their neuroprotective effects. These bioactive compounds exhibit a range of therapeutic properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and anti-aggregation activities, largely mediated through their influence on kinase signaling pathways (Bhusal, 2023). Critically, they activate pathways that enhance intracellular antioxidant enzymes, effectively neutralizing free radicals responsible for oxidative damage. These compounds modulate kinase activity by increasing the Bcl/Bax ratio, thereby reducing Caspase-3 activity to prevent neuronal apoptosis. Additionally, they inhibit key kinases in the MAPK signaling pathways, specifically reducing the activity of JNK, ERK, and P38, decreasing the production of downstream proinflammatory mediators (Magalingam et al., 2015). Targeting kinases could serve as a potential therapeutic option for neurodegenerative disorders.

A. africana, popularly known as the false Iroko tree in Africa, is used to treat many illnesses including leprosy, diabetes, cancer, respiratory and stomach disorders, mental disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases (Adewunmi et al., 2018; Kuete et al., 2009; Oke, 2017). Despite these documented findings about its remarkable activities, the neuroprotective mechanism remains elusive. It has been shown that leaf extracts from A. africana contain phenolic compounds with neuroprotective properties (Ilesanmi, 2022), indicating the need for further research into its specific effects and potential mechanisms in Parkinson's disease.

The drug design and discovery process is an intricate network that focuses on identifying compounds that are therapeutically effective for treatment. Over the last two decades, the major hurdles that have impacted the drug discovery process are the identification of drugs with high efficacy and minimum toxicity, high cost, and time consumption (Rohan Gupta et al., 2021). To maximize efficiency and minimize the hurdles and challenges, researchers are employing computer-aided drug design (CADD). The advancement in technology and the abundance of multiple omics data provide useful information to improve therapy strategies (Rohan Gupta et al., 2021). Through artificial intelligence, algorithms, and deep machine learning, CADD can be used to screen for novel compounds and predict their targets and potential toxicities. CADD provides an efficient method for virtual screening whiles reducing the time and cost of drug discovery. Molecular docking is a computational technique that predicts the interaction between small molecules and their target proteins, facilitating the identification of potential therapeutic compounds (R. Gupta et al., 2021). This approach has shown promise in various neurodegenerative diseases by identifying compounds that can interact with key pathological targets, such as alpha-synuclein and LRRK2 in PD. Network pharmacology, on the other hand, provides a holistic view of the interactome, allowing researchers to understand the complex interactions within biological systems (Gong et al., 2021). By identifying key nodes and pathways involved in disease mechanisms, network pharmacology can highlight potential multi-target therapeutic strategies that may be more effective in treating complex diseases like PD. Combining molecular docking and network pharmacology offers a synergistic approach to drug discovery, enhancing the prediction of therapeutic effects by integrating target-specific interactions with a broader understanding of the disease network. This study aims to leverage this integrated approach to identify and predict the therapeutic potential of phenolic compounds found in A. africana, potentially contributing to the development of disease-modifying therapies.

Methodology

Parkinson-related targets and compounds target prediction

Genes associated with Parkinsonism were retrieved from GeneCards (

https://www.genecards.org/ accessed on 15 April 2024). The SwissTargetPrediction (

http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/ accessed on 15 April 2024) and STITCH database (

http://stitch.embl.de/ accessed on 15 April 2024) were utilized to predict the putative protein targets for compounds found in the

A. africana extract; Caffeic Acid, Chlorogenic Acid, Catechin, Ellagic Acid, Epigallocatechin, Garlic Acid, Isoquercetin, Kaempferol, Quercetin, Quercitrin, Rutin (Gfeller et al., 2014; Kuhn et al., 2010). Swiss Target Prediction was used to identify all compound targets. STITCH database was used to identify targets of Catechin. Compounds were converted into their respective Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) format and submitted to both SwissTargetPrediction and STITCH database servers, which utilize similar measures and curated databases of known ligand interactions for predictions (Gfeller et al., 2014). Targets were converted to their standardized gene names. In the study, all targets identified by the Swiss Target Prediction and STITCH database web servers were included in the analysis. Identified protein targets were uploaded into the STRING database (

https://string-db.org/ accessed on 18 April 20224), where an interactive network was generated utilizing “

Homo Sapiens” as the screening conditions (Szklarczyk et al., 2023). A graphical representation of the functional and physical interactions between proteins was obtained and saved in the CSV format. The Parkinson-related targets were intersected with the compound’s targets to obtain Parkison-related targets, using venny 2.1.0 (

https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/, accessed on 17 April 2024).

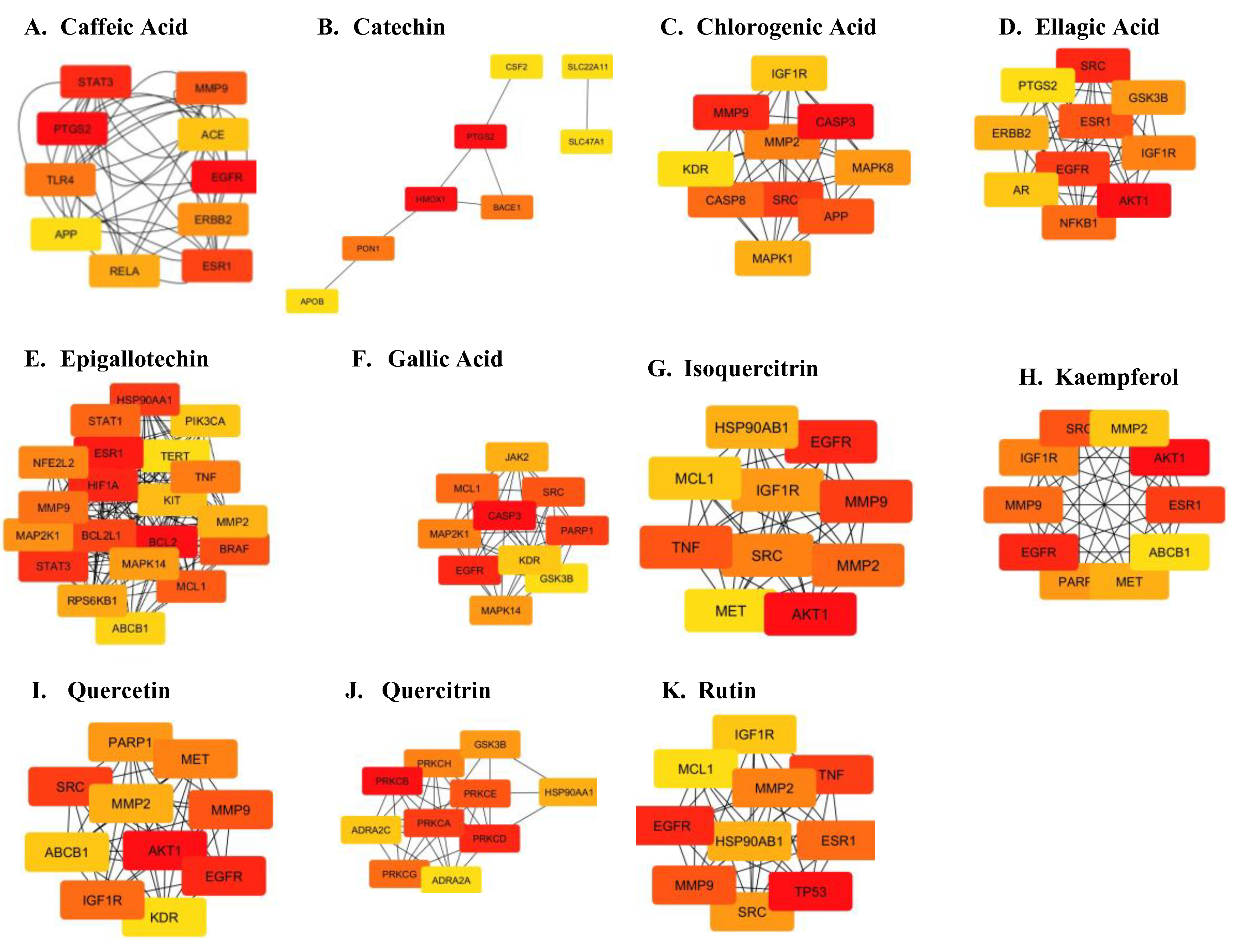

Hub Gene Identification

PPI data was imported into Cytoscape version 3.10.0, and the core targets of compounds were identified using the CytoHubba plugin (Chin et al., 2014; Doncheva et al., 2019). The PPI network was analyzed using algorithms in Cytohubba, arranging genes based on their degree of association with other genes from highest to lowest using the Degree method. The network was visualized using the 'Organic Layout' in Cytoscape to highlight key hubs and clusters. The top ten ranked targets for all compounds were used for analysis.

Functional enrichment analysis and diseased genes Identification

The METAscape webserver ((

https://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1 accessed on 20 April 2024) was used to analyze Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) clusters, identifying pathways significantly enriched with our genes of interest (Zhou et al., 2019). The KEGG database provides a curated collection of pathways representing molecular interaction, reaction, and relation networks for various biological processes. Using statistical analysis, we identified pathways significantly enriched with the mapped genes. Subsequently, a KEGG pathway plot was created through enrichment analysis. The functional analysis incorporated the DisGeNET database to identify disease-related genes, primarily focusing on parkinsonism (Pinero et al., 2021). A list of all protein targets implicated in Parkinsonism was curated for each compound in a table.

PPI Network of Parkinson-related targets in Compounds

A PPI network of the Parkinson related-targets of compounds was constructed in the STRINGS database (

https://string-db.org/ accessed on 20 April 2024). Similarly, an interactive network was generated utilizing “

Homo Sapiens” as the screening conditions, and a graphical representation of the functional and physical interactions between proteins was obtained.

Virtual Screening

Virtual screening was conducted to identify potential molecular targets using molecular docking techniques. Ligand structures were sourced from the PubChem database (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ accessed on 21 April 2024), while crystal structures of proteins were modeled using SWISS-MODEL (

https://swissmodel.expasy.org/ accessed on 21 April 2024) (Waterhouse et al., 2018). Protein structures were prepared using PyRx software by removing water molecules and adding polar hydrogen atoms to ensure proper interaction modeling (Dallakyan & Olson, 2015). Ligands were prepared using Open Babel, including steps for energy minimization and conformer generation to ensure accurate docking results. PyRx utilizes the AutoDock Vina molecular docking engine, a well-known software for predicting ligand-receptor interactions. PyRx enhances the usability of AutoDock Vina through an intuitive interface and additional features (Trott & Olson, 2010). Docking parameters were set with a grid box size and center adjusted to cover the active site, and the exhaustiveness parameter was optimized for a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. The top ten poses of each ligand were generated based on their docking scores. From these, the pose with the lowest binding affinity score was chosen for further analysis, indicating the strongest predicted interaction. BioDiscovery Studio was employed to analyze the results, focusing on identifying the types of ligand interactions present at the active sites, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic interactions. Docking binding energy was used to evaluate the potential of molecules to bind to target proteins associated with disease-related genes, specifically assessing their suitability as potential therapeutic agents.

Methodology

Compound targets and Parkinson’s-related target prediction

Genes associated with Parkinsonism were retrieved from GeneCards (

https://www.genecards.org/ accessed on 15 April 2024). The SwissTargetPrediction (

http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/ accessed on 15 April 2024) and STITCH database (

http://stitch.embl.de/ accessed on 15 April 2024) were utilized to predict the putative protein targets for compounds found in the A. Africana extract; Caffeic Acid, Chlorogenic Acid, Catechin, Ellagic Acid, Epigallocatechin, Gallic Acid, Isoquercetin, Kaempferol, Quercetin, Quercitrin, Rutin (Gfeller et al., 2014; Kuhn et al., 2010). Swiss Target Prediction was used to identify all compound targets. STITCH database was used to identify targets of Catechin. Compounds were converted into their respective Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) format and submitted to both SwissTargetPrediction and STITCH database servers, which utilize similar measures and curated databases of known ligand interactions for predictions (Gfeller et al., 2014). Targets were converted to their standardized gene names. In the study, all targets identified by the Swiss Target Prediction and STITCH database web servers were included in the analysis. Identified protein targets were uploaded into the STRING database (

https://string-db.org/ accessed on 18 April 20224), where an interactive network was generated utilizing “

Homo Sapiens” as the screening conditions (Szklarczyk et al., 2023). A graphical representation of the functional and physical interactions between proteins was obtained and saved in the CSV format. The Parkinson-related targets were intersected with the compound’s targets to obtain Parkison-related targets, using venny 2.1.0 (

https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/, accessed on 17 April 2024).

Hub Gene Identification

PPI data was imported into Cytoscape version 3.10.0, and the core targets of compounds were identified using the CytoHubba plugin (Chin et al., 2014; Doncheva et al., 2019). The PPI network was analyzed using algorithms in Cytohubba, arranging genes based on their degree of association with other genes from highest to lowest using the Degree method. The network was visualized using the 'Organic Layout' in Cytoscape to highlight key hubs and clusters. The top ten ranked targets for all compounds were used for analysis. For Epigallocatechin the top 20 ranked targets were used

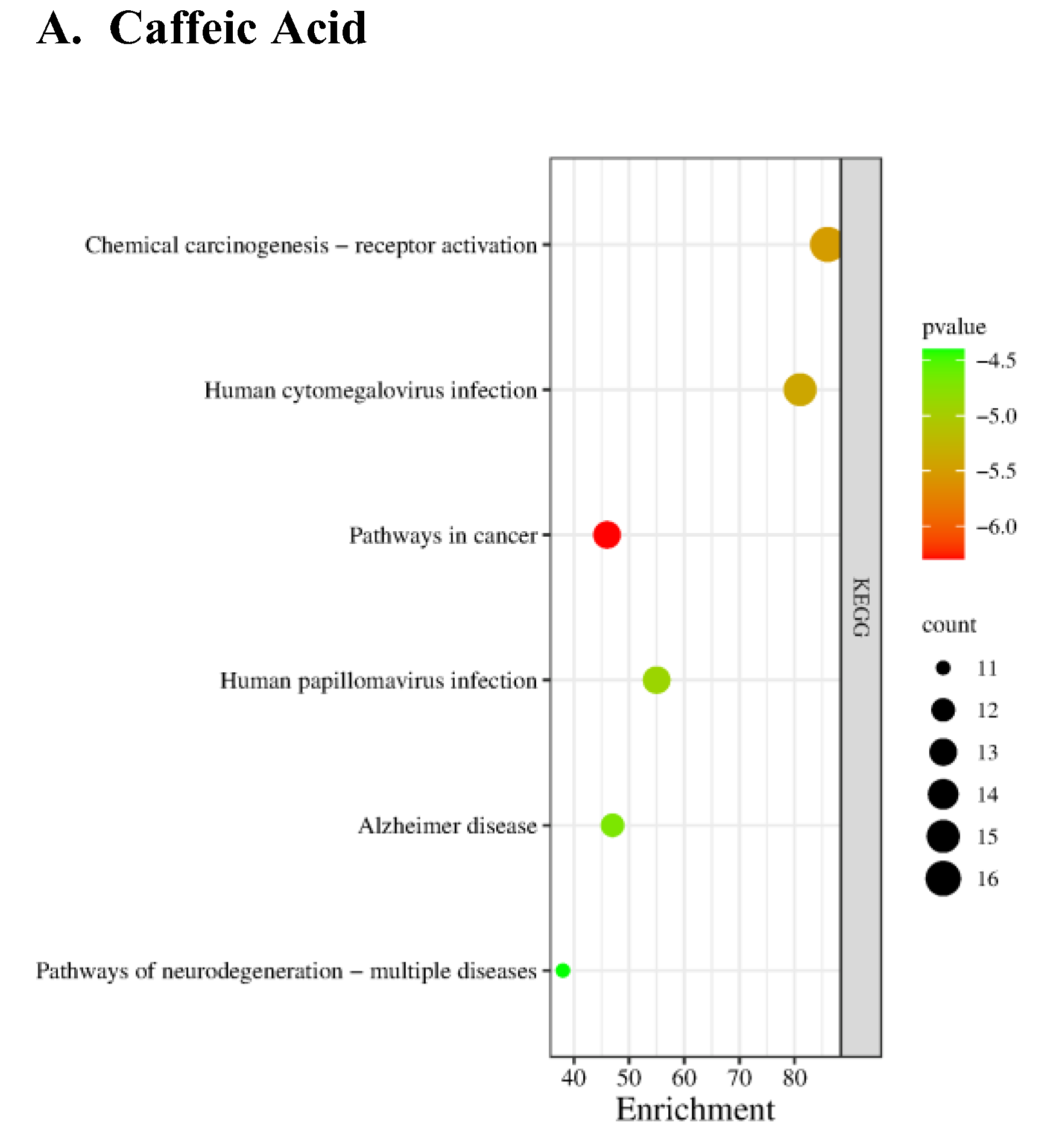

Functional enrichment analysis and diseased genes Identification

The METAscape webserver ((

https://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1 accessed on 20 April 2024) was used to analyze Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) clusters, identifying pathways significantly enriched with our genes of interest (Zhou et al., 2019). The KEGG database provides a curated collection of pathways representing molecular interaction, reaction, and relation networks for various biological processes. Using statistical analysis, we identified pathways significantly enriched with the mapped genes. Subsequently, a KEGG pathway plot was created through enrichment analysis. The functional analysis incorporated the DisGeNET database to identify disease-related genes, primarily focusing on parkinsonism (Pinero et al., 2021). A list of all protein targets implicated in Parkinsonism was curated for each compound in a table.

PPI Network of Parkinson-related targets in Compounds

A PPI network of the Parkinson related-targets of compounds was constructed in the STRINGS database (

https://string-db.org/ accessed on 20 April 2024). Similarly, an interactive network was generated utilizing “

Homo Sapiens” as the screening conditions, and a graphical representation of the functional and physical interactions between proteins was obtained.

Virtual Screening

Virtual screening was conducted to identify potential molecular targets using molecular docking techniques. Ligand structures were sourced from the PubChem database (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ accessed on 21 April 2024), while crystal structures of proteins were modeled using SWISS-MODEL (

https://swissmodel.expasy.org/ accessed on 21 April 2024) (Waterhouse et al., 2018). Protein structures were prepared using PyRx software by removing water molecules and adding polar hydrogen atoms to ensure proper interaction modeling (Dallakyan & Olson, 2015). Ligands were prepared using Open Babel, including steps for energy minimization and conformer generation to ensure accurate docking results. PyRx utilizes the AutoDock Vina molecular docking engine, a well-known software for predicting ligand-receptor interactions. PyRx enhances the usability of AutoDock Vina through an intuitive interface and additional features (Trott & Olson, 2010). Docking parameters were set with a grid box size and center adjusted to cover the active site, and the exhaustiveness parameter was optimized for a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. The top ten poses of each ligand were generated based on their docking scores. From these, the pose with the lowest binding affinity score was chosen for further analysis, indicating the strongest predicted interaction. BioDiscovery Studio was employed to analyze the results, focusing on identifying the types of ligand interactions present at the active sites, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic interactions. Docking binding energy was used to evaluate the potential of molecules to bind to target proteins associated with disease-related genes, specifically assessing their suitability as potential therapeutic agents.

Results

The putative target of compound found in A.Africana and Protein Interaction Network

Hub gene identification and Functional enrichment analysis

To further identify the most crucial targets in each network, all nodes and edges were analyzed using the CytoHubba algorithm. The top ten targets of each network were selected based on Maximal Clique Centrality and degree ranking (

Supplementary Data Sheet 3). KEGG pathway analysis revealed significant involvement of core targets in metabolic, signaling, and cellular processes (

Figure 2;

Supplementary Data Sheet 4). Pathways were ranked based on their p-values, with the most statistically significant pathways listed first.

Parkinson-related Targets and Enrichment analysis

KEGG pathway analysis revealed significant involvement of core targets in metabolic, signaling, and cellular processes (

Figure 3;

Supplementary Data Sheet 4). Pathways were ranked based on their p-values, with the most statistically significant pathways listed first. A total of 5006 Parkinson's disease-related genes were obtained from the GeneCards database (

Supplementary data sheet 1). By cross-referencing 5006 Parkinson's disease-related genes obtained from the GeneCards database with the targets of each compound, we identified several overlapping genes. This overlap was further validated using DisGeNET, which predicted Parkinson’s disease targets for each compound. Our analysis revealed a high similarity between the Parkinson's disease targets identified by both methods, indicating consistency and reliability in our findings. The Parkinson-related targets identified for each compound found in A. Africana are listed in

Table 1

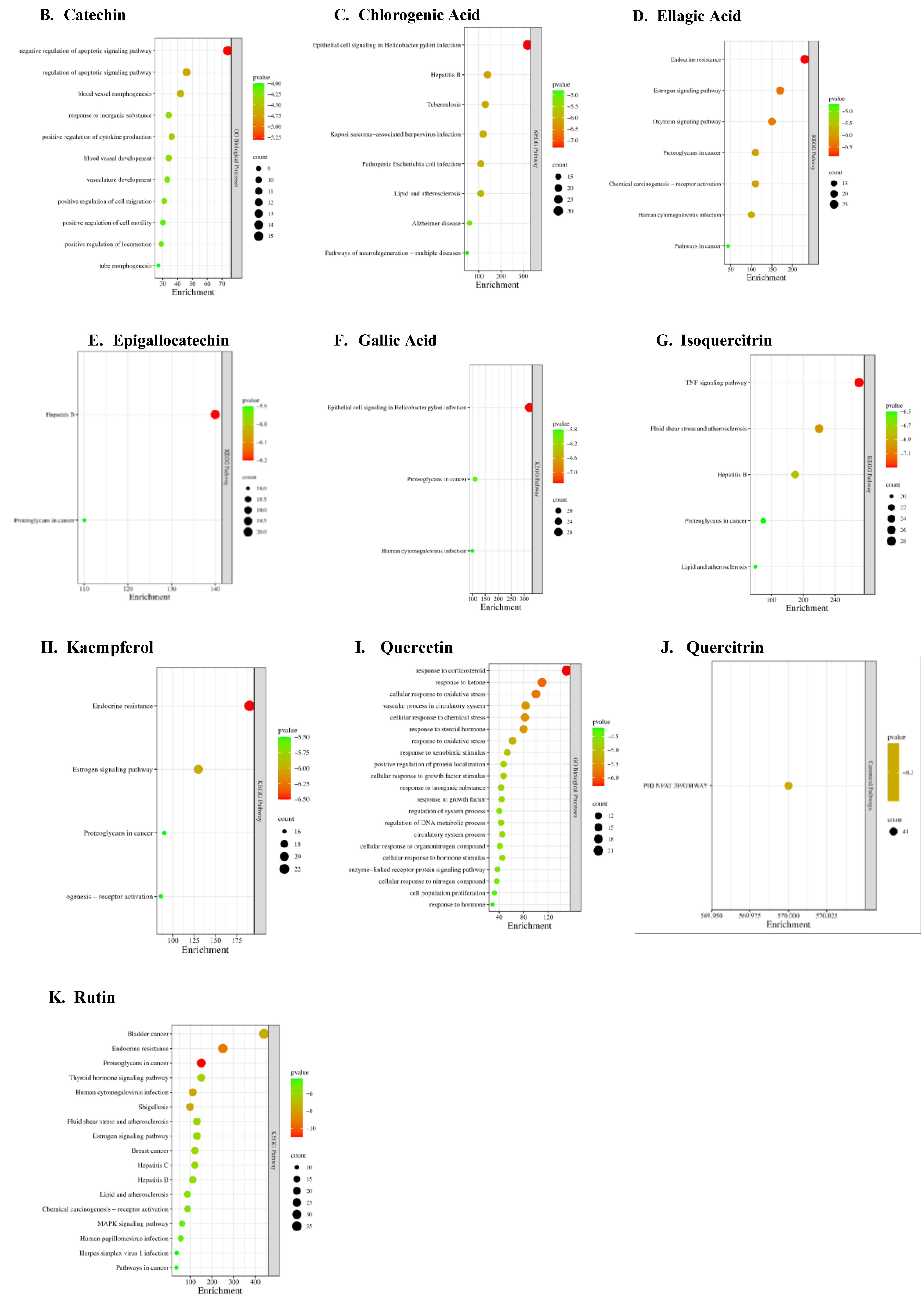

PPI network of Parkinson-related targets

A PPI network of the Parkinson-related targets for each compound found in A. African was constructed in the STRINGS database (

https://string-db.org/ accessed on 20 April 2024) (

Figure 2). The constructed network highlighted a high degree of connectivity between core targets of each compound implicated in Parkinsonism.

Figure 4.

Protein interaction network of targets implicated in Parkinsonism. The black lines between nodes represent genes that are co-expressed across several experiments, the purple line indicates experimentally determined interaction between genes, the yellow lines indicate genes that have been frequently mentioned together and the light blue lines indicate genes that show interaction based on curated data sources.

Figure 4.

Protein interaction network of targets implicated in Parkinsonism. The black lines between nodes represent genes that are co-expressed across several experiments, the purple line indicates experimentally determined interaction between genes, the yellow lines indicate genes that have been frequently mentioned together and the light blue lines indicate genes that show interaction based on curated data sources.

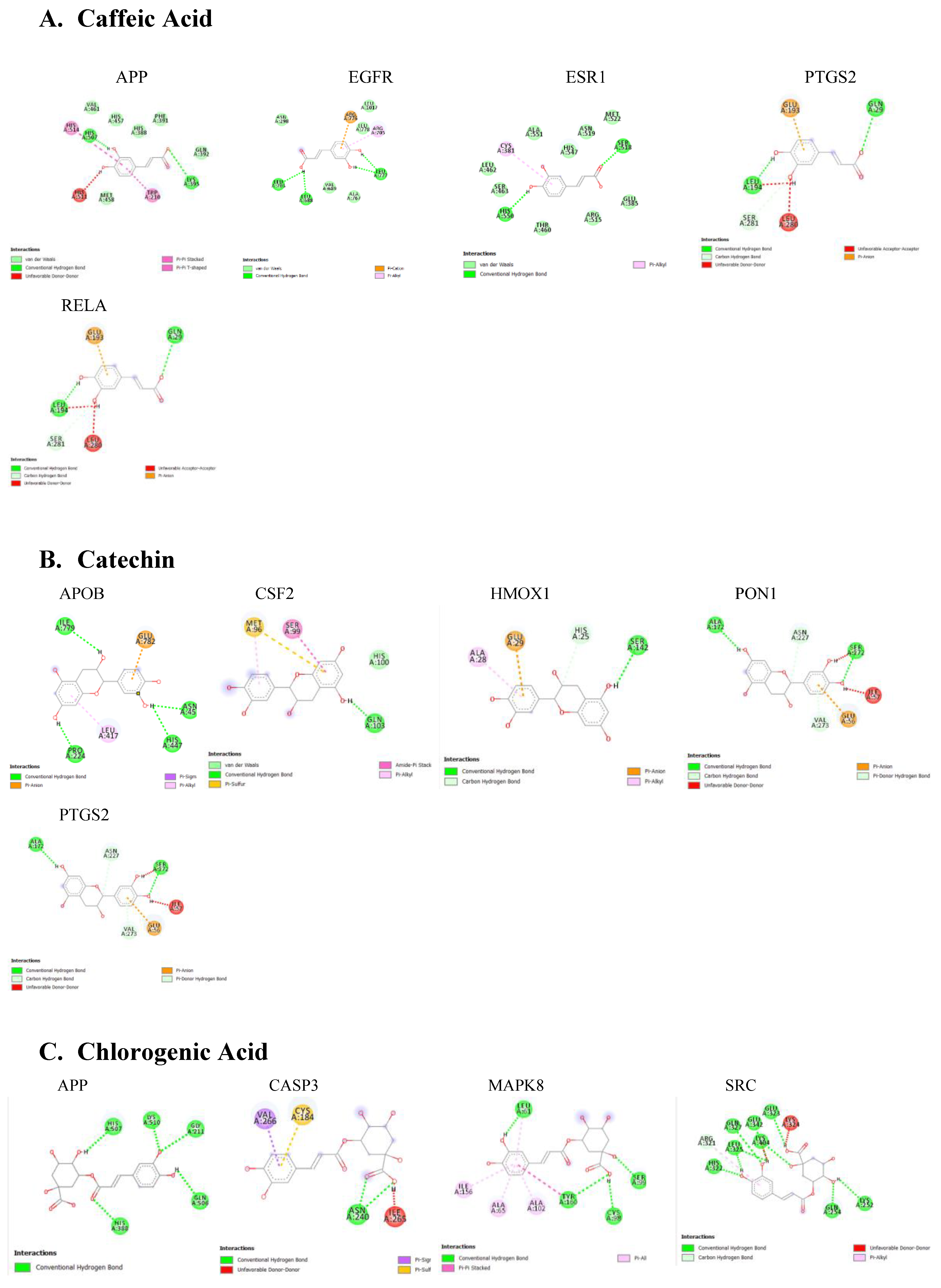

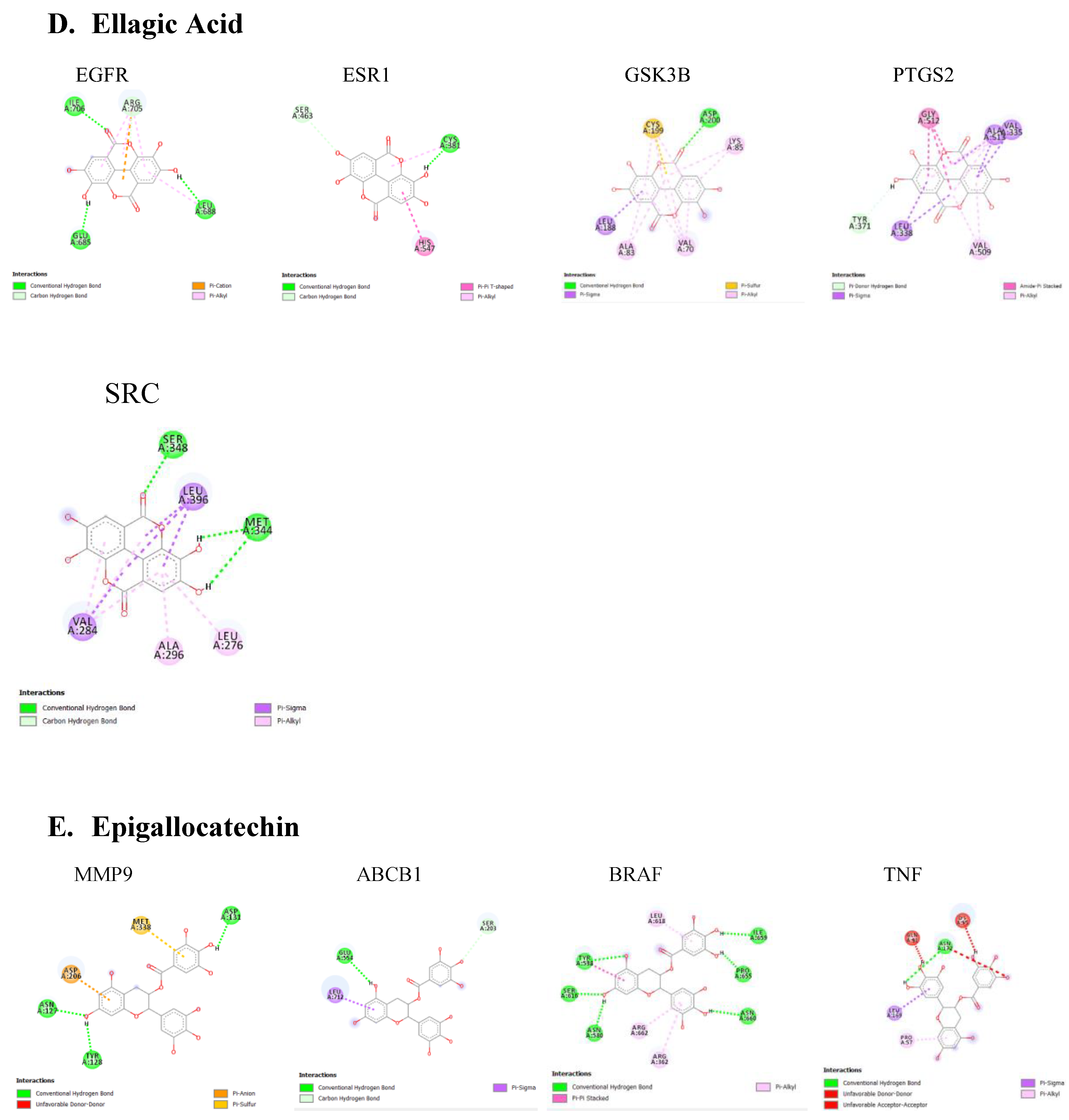

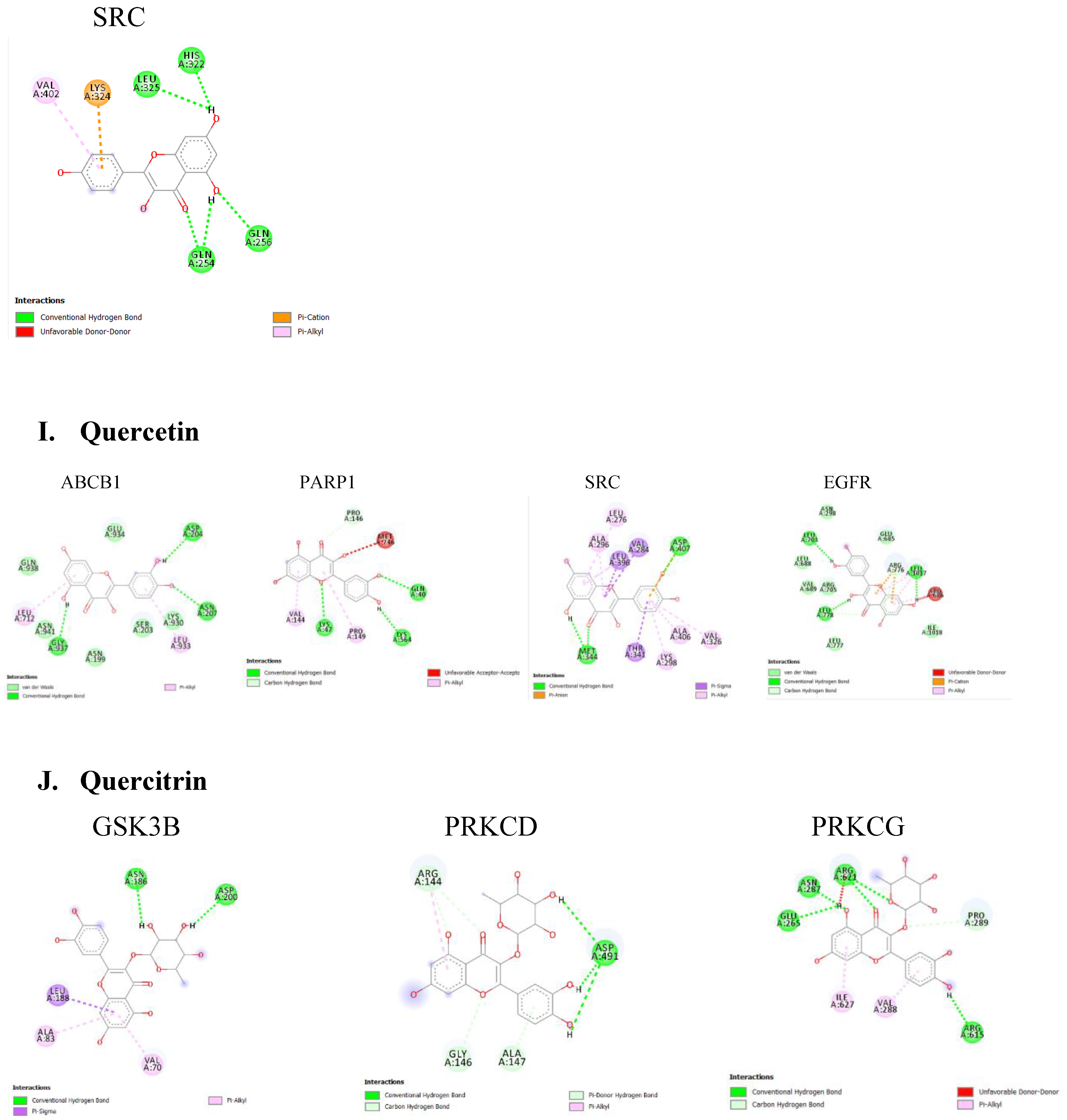

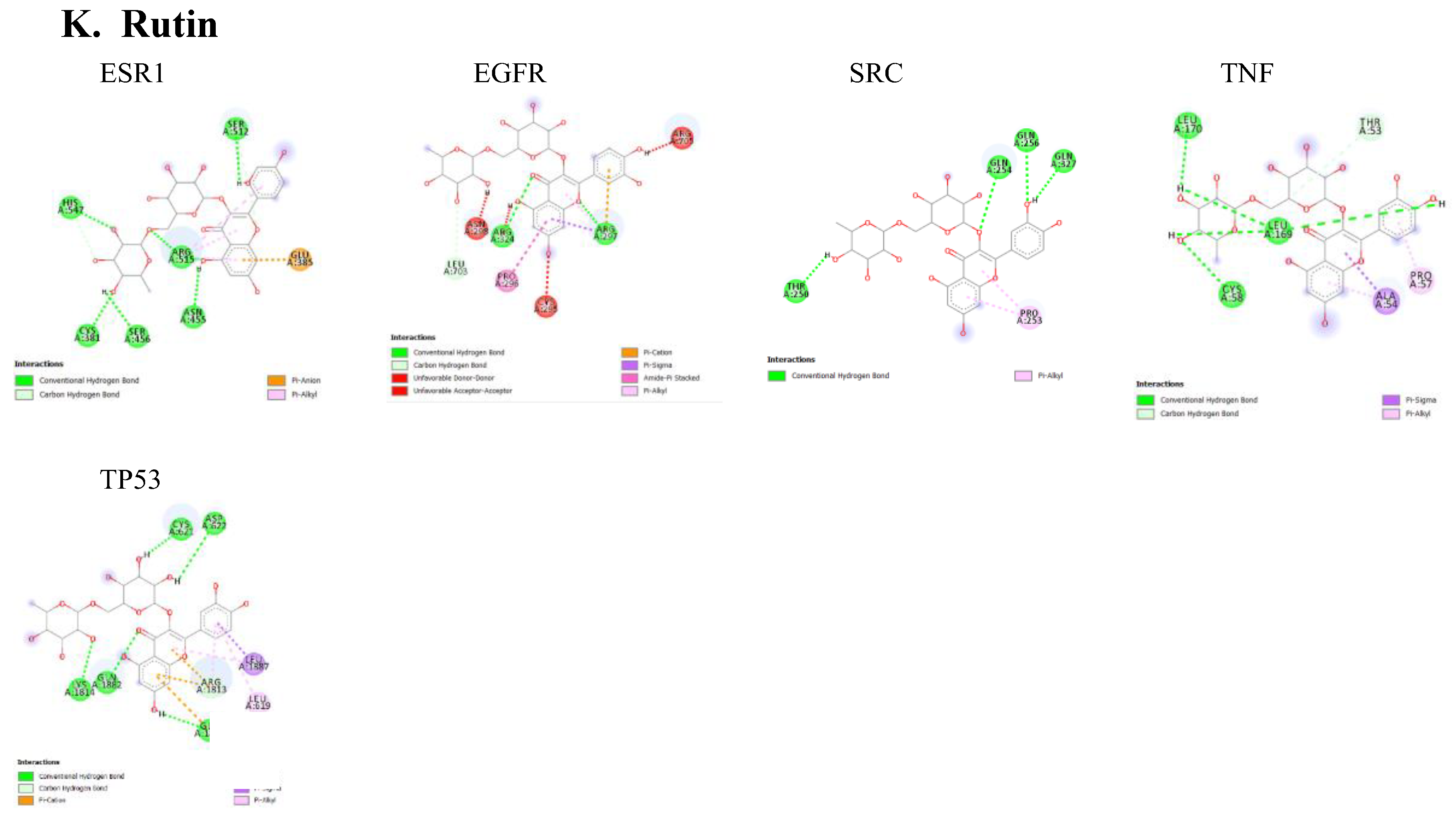

Molecular docking

The protein-ligand docking using PyRx was carried out, which gives the binding energy of the ligand to is active site. The strength of the interactions was quantified by their binding energy (ΔG), measured in kilocalories per mole (kcal/mol)

Table 2. Lower binding energies indicate stronger binding affinities, typically categorized as strong (≤ -8.0 kcal/mol), moderate (-7.0 to -8.0 kcal/mol), or weak (≥ -7.0 kcal/mol). Various type of interactions between ligand and receptor proteins were also observed. These interactions include hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions, π-π stacking, and van der Waals forces. The binding modes and the locations of the plausible binding pockets for the compounds for each target are shown in

Figure 5.

Discussion

Parkinson’s disease is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer’s disease with approximately 6 million cases reported each year with a mean age of 52-70 years (Muangpaisan, 2011; Ye et al., 2023). The considerable morbidity caused by PD and the lack of reliable therapeutic options underscores the necessity of identifying efficient treatment approaches. The article "Unveiling Nature's Potential: Promising Natural Compounds in Parkinson's Disease Management" suggests that natural compounds could represent a crucial shift towards altering the underlying progression of Parkinson's disease, rather than merely managing its symptoms as current treatments do (Bhusal, 2023). Research has shown that crude and fractions of A. Africana leaf extract possesses neuroprotective properties specifically in treating PD (Adewunmi et al., 2018). However, the underlying molecular mechanism remains elusive. This study aims to predict the key targets and pathways through which A. africana exerts its neuroprotective effect in PD.

The in-silico analysis revealed APP as a common target for caffeic acid and catechin. Research has shown that the accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) peptides, cleaved from APP, aggregates to form plaques responsible for neuronal damage, inflammation, and cognitive deficits in elderly individuals with Alzheimer's disease (Hur, 2022; O'Brien & Wong, 2011; Penke et al., 2019). Additionally, recent studies have suggested a link between APP dysregulation and Parkinson's disease. Specifically, the LRRK2 protein, commonly associated with Parkinson’s, has been shown to interact with the amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain (AICD), leading to the phosphorylation of threonine residues. This interaction promotes the dissociation and nuclear translocation of AICD (Lim, 2018). Mutations in LRRK2 can result in increased AICD expression, contributing to the pathology observed in Parkinson’s disease (Schulte, 2015).

Chlorogenic and gallic acids were revealed to bind to CASP3 as a protective mechanism against the pathology of PD. The KEGG analysis revealed CASP3 involvement in neurodegeneration pathways. In the context of PD, CASP3 is activated in the brains of PD patients. This activation correlates with neuronal loss in the substantia nigra, indicating that caspase-3 may contribute to the death of dopaminergic neurons (D'Amelio et al., 2010). Additionally, studies have shown that Parkin protein, crucial in Parkinson's disease pathology, can be cleaved by caspase-3. This cleavage may disrupt Parkin's function, potentially worsening neuronal death in PD (D'Amelio et al., 2010). Inhibiting the over-expression of CASP3 in PD patients with A. africana may be attributed to the neuroprotective effect of this plant.

Our network analysis also revealed ESR1 as a potential PD target for caffeic acid, ellagic acid, kaempferol, and rutin. Among studies investigating the effect of ESR1 on cognition, an association between ESR1 polymorphisms and the onset of dementia has been established. ESR1 functions as the estrogen-binding receptor whose downstream effect protects nigrostriatal pathways and guards against oxidative stress (Sundermann et al., 2010). Single nucleotide polymorphisms observed in the ESR1 coding and non-coding regions have been identified in patients with PD (Chung et al., 2011). Targeting ESR1 to increase its function could serve as an effective strategy for managing PD.

Analysis using DISGeNET revealed that protein kinases, including MAPK8, GSK3B, AKT1, and SRC, are major targets for compounds found in A. africana. These compounds -chlorogenic acid, ellagic acid, gallic acid, kaempferol, quercetin, quercitrin, and rutin- are known to influence kinas activity. Dysfunctional kinase activities and disrupted phosphorylation pathways are strongly implicated in Parkinson's disease (PD).

Specifically, kinases are involved in phosphorylating tau and increasing α-synuclein levels, both of which are critical in the pathogenesis of PD. (Bohush et al., 2018; Guttuso, 2019). MAPK signaling pathways are particularly important, as they play a role in neuroinflammatory responses and neuronal death triggered by α-synuclein aggregates or deficiencies in the parkin or DJ-1 genes, contributing to PD pathogenesis (Bohush et al., 2018). GSK3B, in particular, phosphorylates alpha-synuclein at specific sites, promoting its aggregation and leading to the formation of Lewy bodies (Credle et al., 2015). Isoquercitrin demonstrated a binding energy of -10.7 kcal/mol with AKT1, suggesting a strong and stable interaction. Key residues involved in this binding include Ile290, Leu210, and Val270. AKT1 is involved in signaling pathways that regulate cell survival and apoptosis, indicating that Isoquercitrin may exert neuroprotective effects by modulating these pathways. Additionally, evidence has shown the involvement of AKT1 pathway in autophagy induced neuronal protection (Zhang et al., 2019). Understanding how the levels or activities of these enzymes and their substrates change in brain tissue about pathological states can offer valuable insights into disease pathogenesis. Furthermore, identifying the timing and location of kinase dysfunction is crucial, as modulating some of these signaling pathways could potentially lead to new therapeutic approaches for PD.

(PD) is characterized by Lewy bodies containing aggregated α-synuclein (α-Syn). Polyphosphate can accelerate α-Syn fibril formation, which propagates pathology and triggers inflammation in neurons. Kam et al. found that poly (adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) modulates α-Syn fibril formation, and α-Syn fibrils can activate PARP-1, leading to cell death through parthanatos. It was reported that PARP-1 inhibition blocked these effects, reducing cell death and α-Syn aggregation (Kam et al., 2018). PARP1 was revealed to be targeted by garlic acid, kaempferol, and quercetin indicating a potential inhibition and the protection of PD patients against α-synuclein aggregation.

Also, the majority of the bioactive compounds identified in A. africana, including caffeic acid, ellagic acid, gallic acid, kaempferol, quercetin, and rutin, were shown to have a strong affinity for Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR). EGFR is a transmembrane protein that is activated by the binding of ligands such as EGF and transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-a). This binding leads to a certain conformational change that facilitates the dimerization with other EGFR family members to activate the intrinsic kinase activity of the EGFR proteins leading to autophosphorylation. The phosphorylated tyrosine residues on EGFR serve as docking sites for various adaptor proteins and enzymes containing Src homology 2 (SH2) domains or phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domains. This activated EGFR initiates several downstream signaling cascades, including the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway, JAK-STAT pathway, and PI3K-Akt pathway. These pathways are critical for cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation, and recent research has shown they are often dysregulated in neurodegenerative diseases. The EGFR signaling pathway is crucial for the development and survival of dopaminergic neurons, which are typically lost in the mesencephalic substantia nigra of individuals developing Parkinson’s disease (Jin et al., 2020). Jin et al.'s study highlights a significant correlation between the functional loss of EGFR and the onset of neuroinflammation and dopaminergic neuron degradation. Additionally, a decrease in plasma concentrations of EGF has been observed in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease followed by a significant increase in plasma EGF in advanced PD patients, leading to dysregulated EGFR pathways and subsequent loss of midbrain dopaminergic neurons (Jiang et al., 2015). Chronic neuroinflammation, often linked to the loss of dopaminergic neurons, is a hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases. Research has implicated dysregulated Jak/STAT signaling pathway to the onset of neuronal inflammation and loss of dopaminergic neurons in neurodegenerative diseases (Jain et al., 2021; Rusek et al., 2023). Activation of the Jak/ STAT pathway by EGF or cytokine binding leads to downstream upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators. This inflamed state increases the oxidative stress and leads to the aggregation of alpha-synuclein and the activation of microglia and astrocytes. Reactive astrocytes can therefore produce more pro-inflammatory mediators and this fails to support neuronal health, worsening neuronal dysfunction Subsequently, the chronic neuroinflammatory state marked by the continuous activation of microglia and astrocytes disrupts cellular homeostasis and initiates apoptotic pathways. This toxic environment ultimately leads to the degeneration and loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (Jain et al., 2021). Targeting EGFR signals can be useful for Parkinson's disease (PD) patients. Bioactive compounds of A. africana showing strong affinity with EGFR could help to modulate this path. Given the critical role of EGFR in the survival and function of dopaminergic neurons and its involvement in neuroinflammatory processes, therapeutic strategies aimed at stabilizing or improving EGFR activity could mitigate loss of dopaminergic neurons and reduce neuroinflammatory processes. This approach provides promise for the development of new treatments for PD, potentially improving patients' outcomes by preserving neuronal health and function.

Conclusion

In summary, the in-silico analysis provided a comprehensive approach to determine the plausible targets Phenolic compounds found in A. afriana modulate to offer protection against PD. Major targets including EGFR, ESR1, SRC, AKT1, MAPK8, APP, and PARP1 were identified as key modulators of PD pathology. Consequently, there was sufficient evidence that the neuronal inflammation and aggregation of α-synuclein associated with PD could be reduced by targeting these proteins. Also, the good drug-target relationship implies that A. africana extract may have research and development value in the treatment of PD. The favorable binding of compounds found in A africana to EGFR, ATK1, SRC, ESR1 makes it a candidate for further validation and possible drug development using experimental analysis. It is important to note that this study relies heavily on in-silico analysis, and the exact molecular mechanisms of A. africana’s neuroprotective effects remain to be experimentally validated. Further in vitro and in vivo studies are essential to evaluate the therapeutic potential of A. africana extracts and to validate the predicted drug-target interactions. Addressing these limitations will be crucial in advancing A. africana from a promising natural remedy to a viable therapeutic option for PD treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. This article contains supplementary excel files; S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B.K.A, K.F, J.W.; Methodology and data analysis: J.N.K.A, B.K.A, K.F.; Data Validation: J.W., M.M.S., E.E.N.; Data visualization: J.N.K.A., K.F., B.K.A., E.E.N.; Writing original draft preparation, K.F., B.K.A, J.N.K.A.; Writing-review and editing, M.M.S., E.E.N., J.W., B.K.A.; Funding acquisition, J.W.

Funding

The project was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32161143021, 81271410) and Henan Natural Science Foundation of China (182300410313).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- Adewunmi, R., Ilesanmi, O., Crown, O., Komolafe, K., Akinmoladun, A., Olaleye, T., & Akindahunsi, A. (2018). Attenuation of KCN-induced Neurotoxicity by Solvent Fractions of Antiaris africana Leaf. European Journal of Medicinal Plants, 23(2), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, C. K., Uti, D. E., Mukherjee, D., Alqahtani, T., Alqahtani, S., Bhattacharya, A., & Akash, S. (2023). Unveiling Nature's potential: Promising natural compounds in Parkinson's disease management.

- Bohush, A., Niewiadomska, G., & Filipek, A. (2018). Role of Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase Signaling in Parkinson’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(10), 2973. [CrossRef]

- Chin, C. H., Chen, S. H., Wu, H. H., Ho, C. W., Ko, M. T., & Lin, C. Y. (2014). cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol, 8 Suppl 4(Suppl 4), S11. [CrossRef]

- Chung, S. J., Armasu, S. M., Biernacka, J. M., Lesnick, T. G., Rider, D. N., Cunningham, J. M., & Maraganore, D. M. (2011). Variants in estrogen-related genes and risk of Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders, 26(7), 1234-1242. [CrossRef]

- Credle, J. J., George, J. L., Wills, J., Duka, V., Shah, K., Lee, Y. C., Rodriguez, O., Simkins, T., Winter, M., Moechars, D., Steckler, T., Goudreau, J., Finkelstein, D. I., & Sidhu, A. (2015). GSK-3β dysregulation contributes to parkinson’s-like pathophysiology with associated region-specific phosphorylation and accumulation of tau and α-synuclein. Cell Death & Differentiation, 22(5), 838-851. [CrossRef]

- D'Amelio, M., Cavallucci, V., & Cecconi, F. (2010). Neuronal caspase-3 signaling: not only cell death. Cell Death & Differentiation, 17(7), 1104-1114. [CrossRef]

- Dallakyan, S., & Olson, A. J. (2015). Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol Biol, 1263, 243-250. [CrossRef]

- Doncheva, N. T., Morris, J. H., Gorodkin, J., & Jensen, L. J. (2019). Cytoscape StringApp: Network Analysis and Visualization of Proteomics Data. J Proteome Res, 18(2), 623-632. [CrossRef]

- Gfeller, D., Grosdidier, A., Wirth, M., Daina, A., Michielin, O., & Zoete, V. (2014). SwissTargetPrediction: a web server for target prediction of bioactive small molecules. Nucleic Acids Research, 42(W1), W32-W38. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J., Xu, Z., Hao, S., Chen, B., Zhuang, S., Jiang, G., Bathaie, S., & Wang, P. (2021). Predication of the Underlying Protective Effect of Saffron on Parkinson's Disease via Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R., Srivastava, D., Sahu, M., Tiwari, S., Ambasta, R. K., & Kumar, P. (2021). Artificial intelligence to deep learning: machine intelligence approach for drug discovery. Molecular Diversity, 25(3), 1315-1360. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R., Srivastava, D., Sahu, M., Tiwari, S., Ambasta, R. K., & Kumar, P. (2021). Artificial intelligence to deep learning: machine intelligence approach for drug discovery. Mol Divers, 25(3), 1315-1360. [CrossRef]

- Guttuso, T., Jr., Andrzejewski, K. L., Lichter, D. G., & Andersen, J. K. (2019). Targeting kinases in Parkinson's disease: A mechanism shared by LRRK2, neurotrophins, exenatide, urate, nilotinib and lithium.

- Hur, J. Y. (2022). gamma-Secretase in Alzheimer's disease. Exp Mol Med, 54(4), 433-446. [CrossRef]

- Ilesanmi, O. B., Akinmoladun, A. C., Elusiyan, C. A., Ogungbe, I. V., Olugbade, T. A., & Olaleye, M. T. . (2022). Neuroprotective flavonoids of the leaf of Antiaris africana Englea against cyanide toxicity.

- Jain, M., Singh, M. K., Shyam, H., Mishra, A., Kumar, S., Kumar, A., & Kushwaha, J. (2021). Role of JAK/STAT in the Neuroinflammation and its Association with Neurological Disorders. Annals of Neurosciences, 28(3-4), 191-200. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q. W., Wang, C., Zhou, Y., Hou, M. M., Wang, X., Tang, H. D., Wu, Y. W., Ma, J. F., & Chen, S. D. (2015). Plasma epidermal growth factor decreased in the early stage of Parkinson's disease. Aging Dis, 6(3), 168-173. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J., Xue, L., Bai, X., Zhang, X., Tian, Q., & Xie, A. (2020). Association between epidermal growth factor receptor gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett, 736, 135273. [CrossRef]

- Kam, T.-I., Mao, X., Park, H., Chou, S.-C., Karuppagounder, S. S., Umanah, G. E., Yun, S. P., Brahmachari, S., Panicker, N., Chen, R., Andrabi, S. A., Qi, C., Poirier, G. G., Pletnikova, O., Troncoso, J. C., Bekris, L. M., Leverenz, J. B., Pantelyat, A., Ko, H. S., . . . Dawson, V. L. (2018). Poly(ADP-ribose) drives pathologic α-synuclein neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Science, 362(6414), eaat8407. [CrossRef]

- Kuete, V., Vouffo, B., Mbaveng, A. T., Vouffo, E. Y., Siagat, R. M., & Dongo, E. (2009). Evaluation ofAntiaris africanamethanol extract and compounds for antioxidant and antitumor activities. Pharmaceutical Biology, 47(11), 1042-1049. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M., Szklarczyk, D., Franceschini, A., Campillos, M., von Mering, C., Jensen, L. J., Beyer, A., & Bork, P. (2010). STITCH 2: an interaction network database for small molecules and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res, 38(Database issue), D552-556. [CrossRef]

- Lim, E. W., Aarsland, D., Ffytche, D., Taddei, R. N., van Wamelen, D. J., Wan, Y.-M., Tan, E. K., & Chaudhuri, K. R. (2018). Amyloid-β and Parkinson’s disease. [CrossRef]

- Magalingam, K. B., Radhakrishnan, A. K., & Haleagrahara, N. (2015). Protective Mechanisms of Flavonoids in Parkinson’s Disease. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2015, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Muangpaisan, W., Mathews, A., Hori, H., & Seidel, D. (2011). A Systematic Review of the Worldwide Prevalence and Incidence of Parkinson’s Disease. 94(6).

- O'Brien, R. J., & Wong, P. C. (2011). Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci, 34, 185-204. [CrossRef]

- Oke, R. F. (2017). NEUROPROTECTIVE ACTIVITY OF Antiaris Africana (FALSE IROKO TREE) LEAF EXTARCT AND FRACTIONS AGAINST MITOCHONDRIAL TOXICANTS. http://196.220.128.81:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/1330.

- Penke, B., Bogar, F., Paragi, G., Gera, J., & Fulop, L. (2019). Key Peptides and Proteins in Alzheimer's Disease. Curr Protein Pept Sci, 20(6), 577-599. [CrossRef]

- Perdigão, J. M., Teixeira, B. J. B., Baia-Da-Silva, D. C., Nascimento, P. C., Lima, R. R., & Rogez, H. (2023). Analysis of phenolic compounds in Parkinson’s disease: a bibliometric assessment of the 100 most cited papers. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 15. [CrossRef]

- Pinero, J., Sauch, J., Sanz, F., & Furlong, L. I. (2021). The DisGeNET cytoscape app: Exploring and visualizing disease genomics data. Comput Struct Biotechnol J, 19, 2960-2967. [CrossRef]

- Pringsheim, T., Jette, N., Frolkis, A., & Steeves, T. D. L. (2014). The prevalence of Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. [CrossRef]

- Rusek, M., Smith, J., El-Khatib, K., Aikins, K., Czuczwar, S. J., & Pluta, R. (2023). The Role of the JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease: New Potential Treatment Target. Int J Mol Sci, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Schulte, E. C., Fukumori, A., Mollenhauer, B., Hor, H., Arzberger, T., Perneczky, R., Kurz, A., Diehl-Schmid, J., Hüll, M., Lichtner, P., Eckstein, G., Zimprich, A., Haubenberger, D., Pirker, W., Brücke, T., Bereznai, B., Molnar, M. J., Lorenzo-Betancor, O., Pastor, P., Peters, A., Gieger, C., Estivill, X., Meitinger, T., Kretzschmar, H. A., Trenkwalder, C., Haass, C., & Winkelmann, J. (2015). Rare variants in β-Amyloid precursor protein (APP) and Parkinson's disease.

- Sundermann, E. E., Maki, P. M., & Bishop, J. R. (2010). A review of estrogen receptor α gene (ESR1) polymorphisms, mood, and cognition. Menopause, 17(4), 874-886. [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D., Kirsch, R., Koutrouli, M., Nastou, K., Mehryary, F., Hachilif, R., Gable, A. L., Fang, T., Nadezhda, Pyysalo, S., Bork, P., Lars, & Christian. (2023). The STRING database in 2023: protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Research, 51(D1), D638-D646. [CrossRef]

- Trott, O., & Olson, A. J. (2010). AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem, 31(2), 455-461. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A., Bertoni, M., Bienert, S., Studer, G., Tauriello, G., Gumienny, R., Heer, F. T., de Beer, T. A. P., Rempfer, C., Bordoli, L., Lepore, R., & Schwede, T. (2018). SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res, 46(W1), W296-W303. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2023). Parkinson disease. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/parkinson-disease.

- Ye, H., Robak, L. A., Yu, M., Cykowski, M., & Shulman, J. M. (2023). Genetics and Pathogenesis of Parkinson's Syndrome. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, 18(1), 95-121. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Guo, H., Guo, X., Ge, D., Shi, Y., Lu, X., Lu, J., Chen, J., Ding, F., & Zhang, Q. (2019). Involvement of Akt/mTOR in the Neurotoxicity of Rotenone-Induced Parkinson’s Disease Models. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3811. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Zhou, B., Pache, L., Chang, M., Khodabakhshi, A. H., Tanaseichuk, O., Benner, C., & Chanda, S. K. (2019). Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun, 10(1), 1523. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).