1. Introduction

In the last few decades, many researchers have become interested in Nanomaterials(1–4). Most researchers are investigating the thermophysical properties of these materials for various shapes and sizes while analyzing them at high pressure and temperature. These materials find widespread use in solar panels, wear-resistant coatings, tissue engineering, lithium-ion batteries, cancer treatment, and lightweight armor, among other applications. Materials with at least one dimension reduced to the nanoscale range, known as nanomaterials, have newly evolved features that link bulk and single-molecule materials(5–9). The primary focus of nanoscience and nanotechnology study is the unique properties of materials at the nanoscale. Scientists and researchers are drawn to the intriguing behavior of particles at the nanoscale(10)(11). The size and shape-dependent characteristics of nanoparticles have sparked great interest in materials research(12). There are different types of nanoparticles like metallic nanoparticles, semiconductor nanoparticles and other materials nanoparticles. In metal nanoparticles, surface effects become significant due to the high surface area-to-volume ratio(13). These effects can influence the electron density and plasmon resonance. In semiconductor nanoparticles, quantum confinement effects become prominent. The electrons are confined within a small space, leading to discrete energy levels and altered optical properties(14). Semiconducting nanoparticles, with their configurable band gap and high surface-to-volume ratio, are the most promising of the numerous types of nanoparticles for a range of optoelectronic and photovoltaic applications(15,16).

Synthesizing semiconductor nanoparticles with the desired size and shape remains a challenging task. The properties of these nanoparticles are heavily influenced by their size and shape, making it essential to accurately determine their thermal stability for various applications(5,17,18). Cohesive energy is the amount of energy needed to separate the atoms of a solid into separate atomic species. In semiconductor nanomaterials, cohesive energy is one of the most important physical factors determining a material’s thermal stability, along with melting temperature, vibrational frequency, dielectric properties, electrical conductivity, band gap, melting enthalpy, Debby temperature, and Curie temperature. The melting temperature and cohesive energy of nanoparticles with a reasonably free surface are known to decrease with decreasing particle size, both theoretically and empirically(5,8,19)(20) for free nanoparticles. However, we can incorporate these particles into various matrices, as doing so may raise the melting point of the embedded particles to optimize the nanoparticle at high temperatures. Over the past decade, significant theoretical and experimental research has been conducted to explore the unique properties of nanomaterials, resulting in numerous exciting discoveries(21–23). Using the cohesive energy concept, Srivastava et al. (2023)(5) reported the melting temperatures of four significant semiconductor nanomaterials: CdSe, CdTe, ZnSe, and ZnS with different sizes and shapes. In addition to being measured empirically, the cohesive energy can be predicted using a variety of thermodynamic models, including as the Qi and Wang Model(24), the Shi- Jiang Model(25), the Bond Energy Model(26), the Guisbiers’ Model(27), and the universal Liquid Drop Model(28). However, the precise model that can provide a convincing explanation is still lacking. Because these thermodynamic models do not take into account all of the earlier mentioned and applicable parameters, including the packing factor for the atomic packing in the corresponding crystalline structure, the relaxation factor for unsaturated bonds of atoms residing on the surface, and the shape factor’s simultaneous representation of polyhedral shapes. Therefore, by proposing a modified version of the Qi and Wang Model, a generalized formulation of the cohesive energy is created that simultaneously incorporates the two factors: the packing factor, and the shape factor of the nanoparticles which are crucial aspects to study thermophysical properties of semiconductor nanomaterials.

The bond energy of Qi and Wang has been modified to account for the cohesive energy and melting temperature of semiconductor nanomaterials. The size, packing factor, and shape factor of the semiconductor nanoparticles are taken into account in this improved model. The equation for the size-dependent melting temperature of semiconductor nanoparticles was derived based on the relationship between the cohesive energy and other thermophysical parameters of the nanomaterials. The well-known semiconductor nanomaterials InSb, ZnSe, CdS, and CdSe nanoparticles in various shapes (Nanowire, Spherical, octahedral, hexahedral, and tetrahedral) were the particular focus of this study. A graph presents the comparison between the theoretical results with experimental results, simulation data, previously published data, and other theoretical modeling.

2. Theoretical Models

As Qi and Wang Model(24), the cohesive energy of nanomaterials

can be expressed as follows:

where

represents the cohesive energy of bulk material,

denotes the number of atoms in nanomaterial, and

denotes the number of surface atoms.

Melting temperature

shows a linear variation with cohesive energy under the relation(29);

Where

is the Boltzmann constant. The relation in Equation (2) is also done for the nanomaterials as;

Where

is the melting temperature of nanomaterial. By rearranging the Equations (1)–(3) we get the relation;

When accounting for variations in particle shape, the shape factor

is determined by comparing the surface area of nanosolids with a spherical shape of diameter(

to the surface area of nanosolids with any shape(30). Assuming the atoms that make up the nanoparticles are perfect spheres with a specific diameter

, each surface atom contributes a certain area of

to the total surface area of the particle.Therefore, the shape factor can be mathematically represented as;

Where

is the surface area

of the spherical nanoparticle with diameter

,

is the surface area of the nanosolids in any shape whose volume is the same as the spherical nanosolids. From Equation (5), the surface area of a nanoparticle, regardless of its shape, is determined by;

The total number of surface atoms, denoted by N, can be calculated by dividing the nanoparticle’s surface area by the area of a circle with a diameter equal to the nanoparticle’s diameter

. Thus,

The number of total atoms of nanosolid is the ratio of the particle volume to the atomic volume, which may be written as

Because the volume of the nanosolid is the same as the volume of the atom, the atom is an ideal sphere.

The value of varies depending on the shape and size of the nanomaterials. Qi calculated the value of using the concept of the shape factor (α)(31). Using the definition of shape factor, the spherical shape is the volume of the nanosolid given by and the atomic volume will be . Thus the total number of atom is . The surface area is nanosolid given by and the area of a circle of an atom contributing to the surface with a diameter() is given by. Now, the value of the is and is . The shape factor for spherical nanosolids is 1. Based on the definition of the shape factor(Equation 5), the surface area increases as the shape factor rises for a given particle size(24). In the case of a cylindrical nanowire with diameter() and length(), its volume is then the total number of atom is . The surface area of the nanowire is +, then the total surface atom () is . Now, the value of is , this is for any disk like nanosolid. In our calculation, we assume that for nanowire the value of is reduced to and the value of the shape factor will be . As the size of the nanowire decreases, this ratio becomes larger than that of a sphere, resulting in a shape factor less than 1 when compared to the shape factor of the spherical nanoparticle. Thus, nanowires are less efficient in minimizing their surface area relative to their volume than spherical shapes, leading to a shape factor (α) that is less than 1.

The number of atoms in a nanoparticle cannot be precisely determined without considering the packing factor

, which accounts for the gaps between the constituent crystals(32). Thus Equation (8) becomes;

The packing factor(

) determines the maximum proportion of available space that can be occupied by densely packed hard spheres(33):

The fraction of space occupied by atoms in a crystal is measured by the packing factor (

). The kind of crystal structure and the atomic radii of the component atoms determine this. Variations in the atomic radii of the constituent atoms can cause differences in the packing factor for a given crystal structure. The packing factor (

) tabulated in

Table 1 is for the Zinc blende (cubic) crystal structure of InSb, ZnSe, CdSe, and CdS semiconductor nanosolid.

Combining Equations (7) and (9), the ratio of the total number of surface atoms to the number of total atoms within a nanoparticle becomes;

Now, substituting Equation (11) into Equation (1), then the Equation (1) gives the size and shape-dependent cohesive energy of nanosolids with containing the packing factor

;

This also gives the size and shape-dependent melting temperature of nanosolids containing the packing factor

;

The expression in Equation (13) presents the melting temperature for semiconducting nanomaterials depending on their size and shape.

Equations (12) and (13) describe models that depend on the sizes and shapes of nanoscale solids. These equations establish connections for the cohesive energy and the melting temperature of nanosolids, respectively, considering the crystal’s packing efficiency.

3. Result and Discussion

This research aims to develop a single model that can accurately predict the cohesive energy and melting temperature of various semiconductor nanomaterials, such as ZnSe, InSb, CdSe, and CdS. The model is based on the Qui and Wang cohesive energy formula, which is modified to account for the unique properties of these nanomaterials. The study involves calculating the cohesive energy and melting temperature for different shapes and sizes of these semiconductor nanomaterials using Equations (12) and (13). The chosen materials’ atomic diameter (d) and packing factor (

μ) vary based on their crystalline structures, which are listed in

Table 1.

Table 2 provides the shape factor (α) for several popular shapes, including Nanowire, Spherical, Regular octahedral, Regular hexahedral, and Regular tetrahedral, which a low-dimensional solid can also assume.

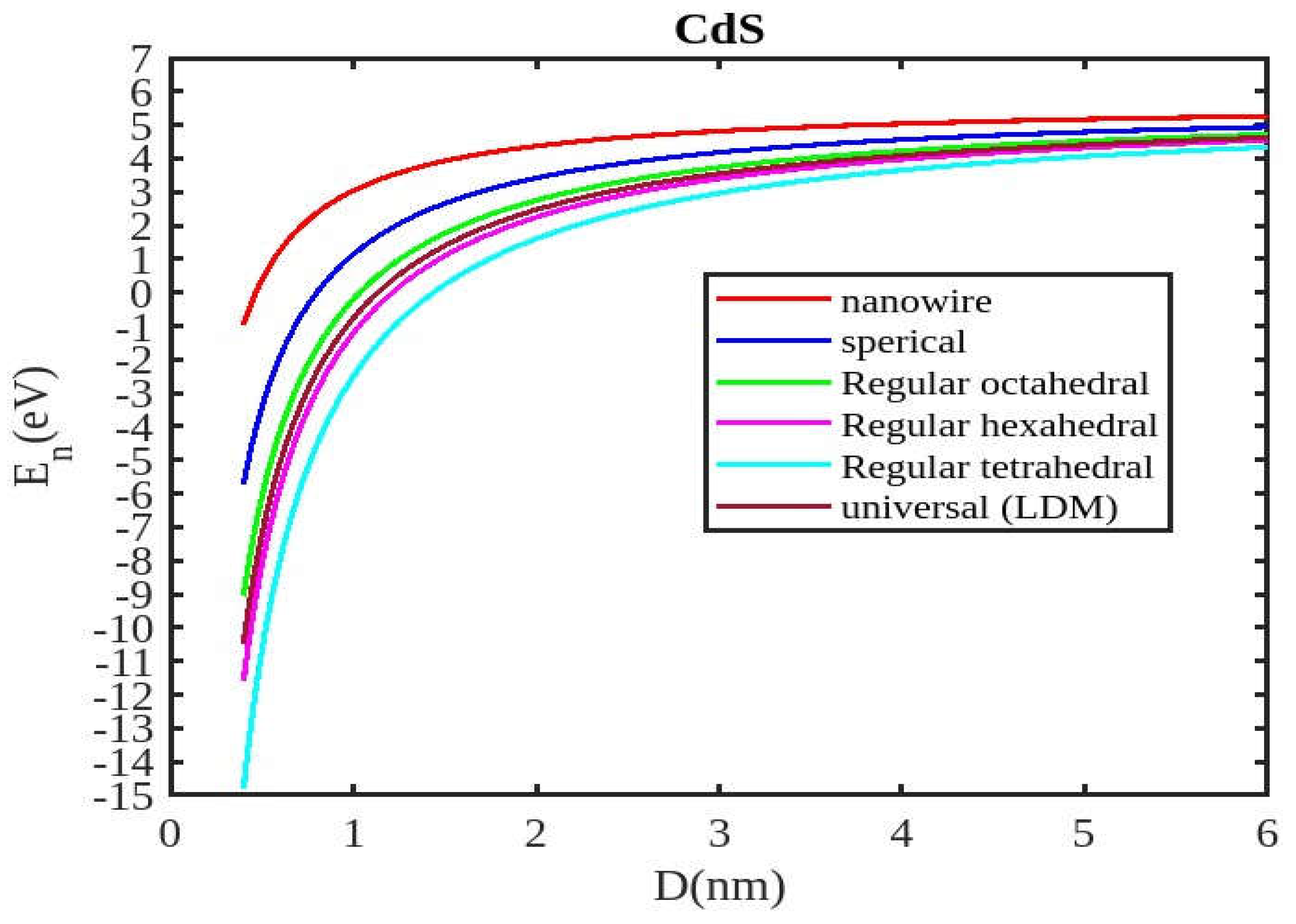

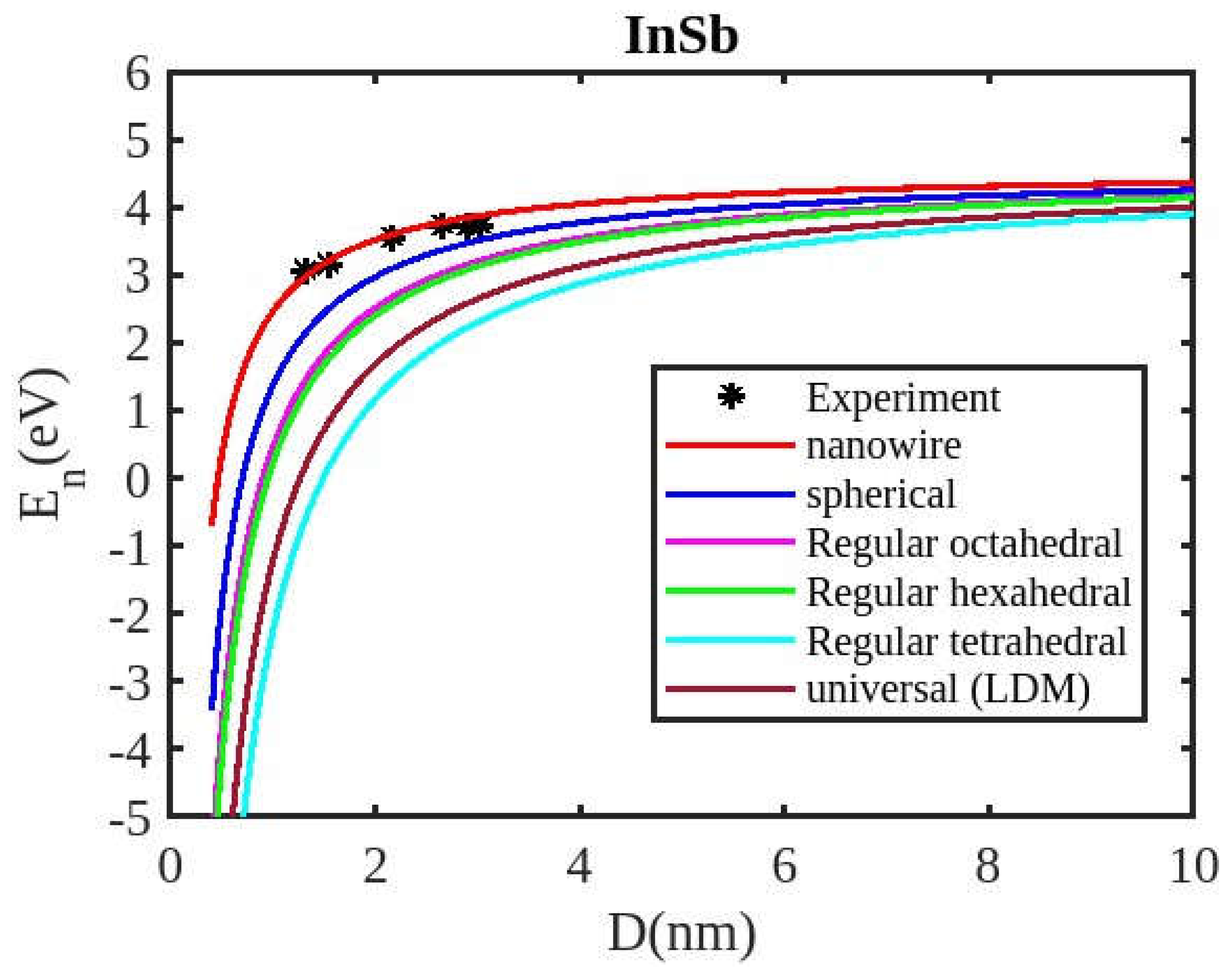

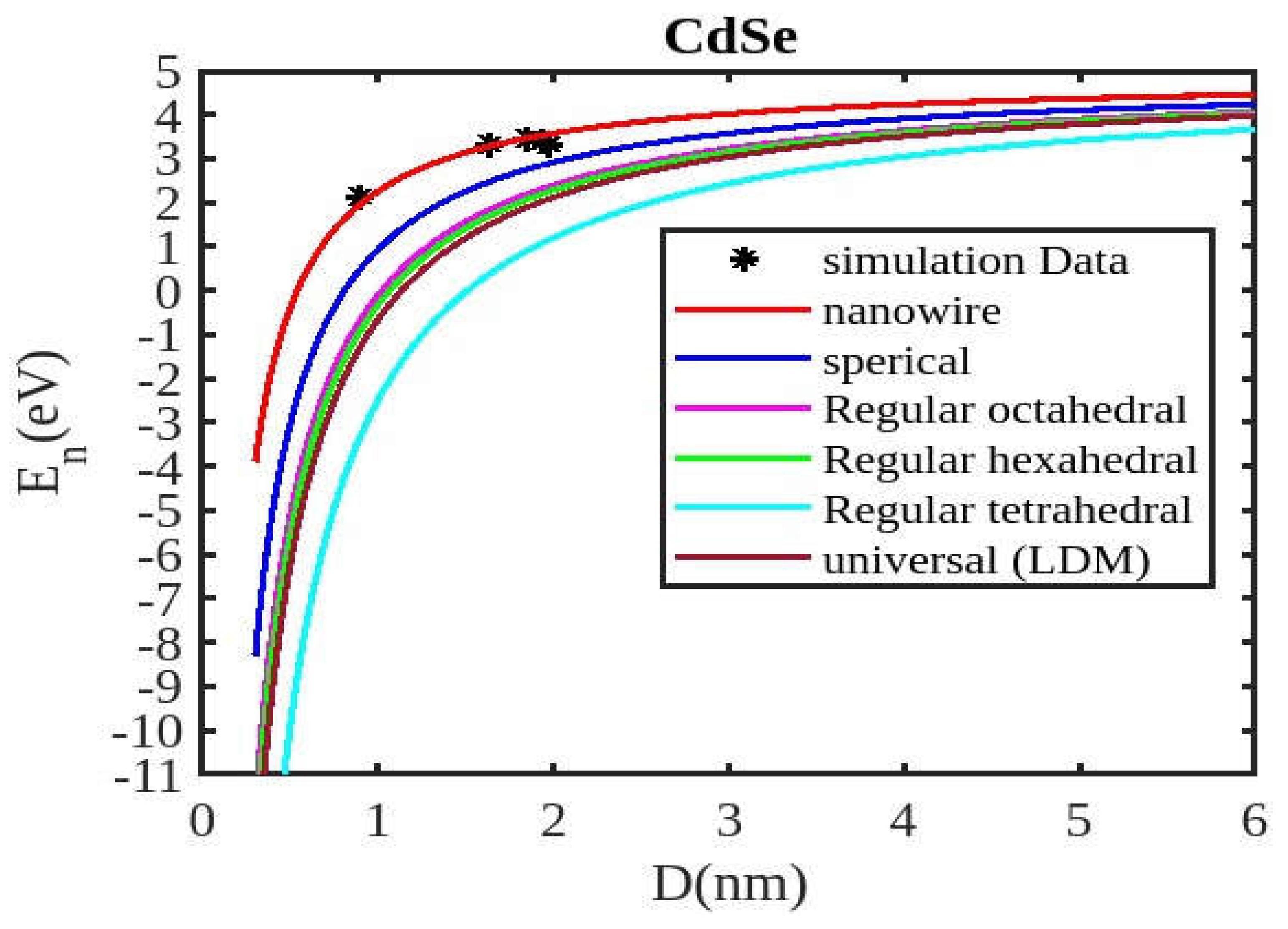

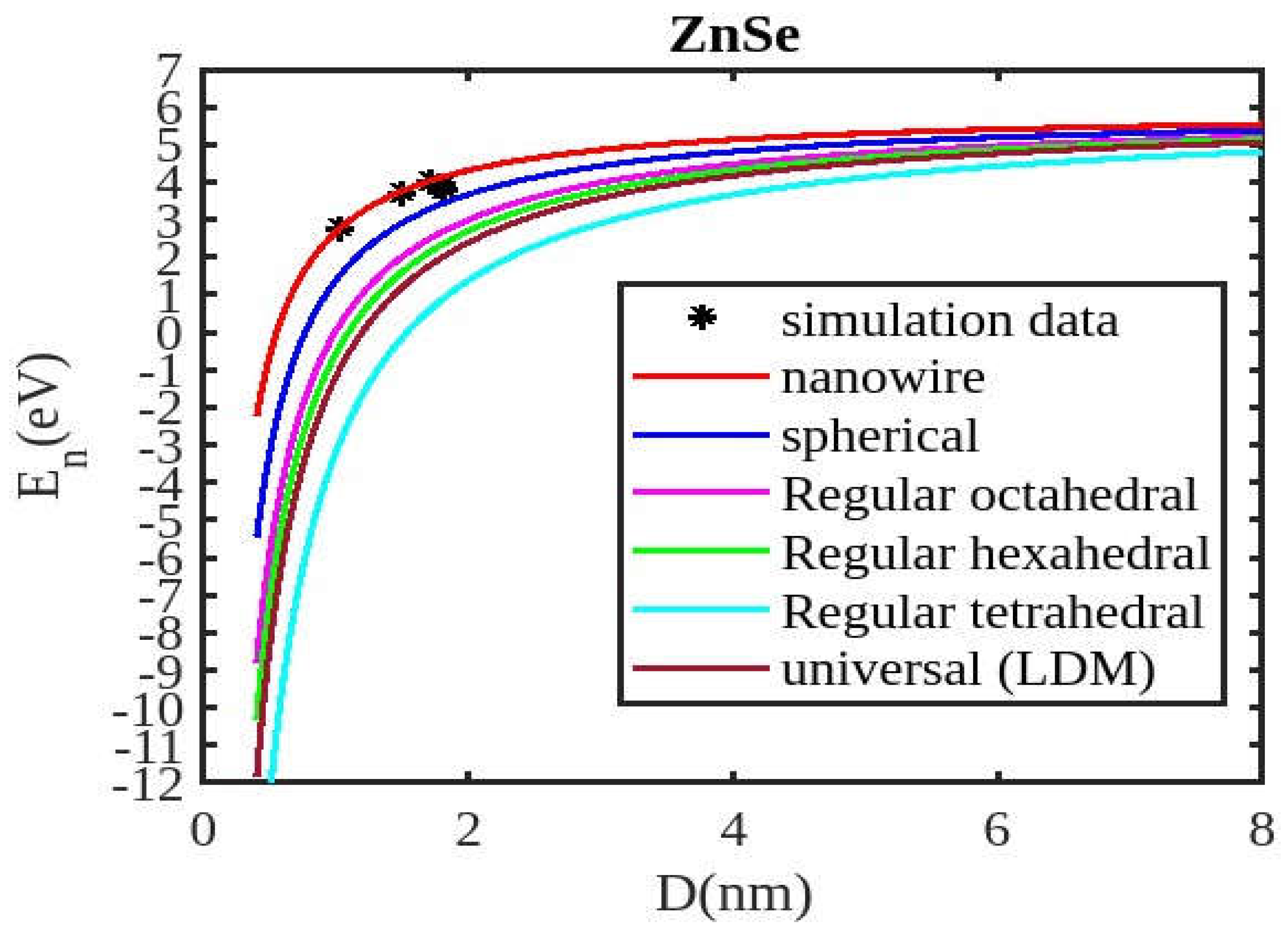

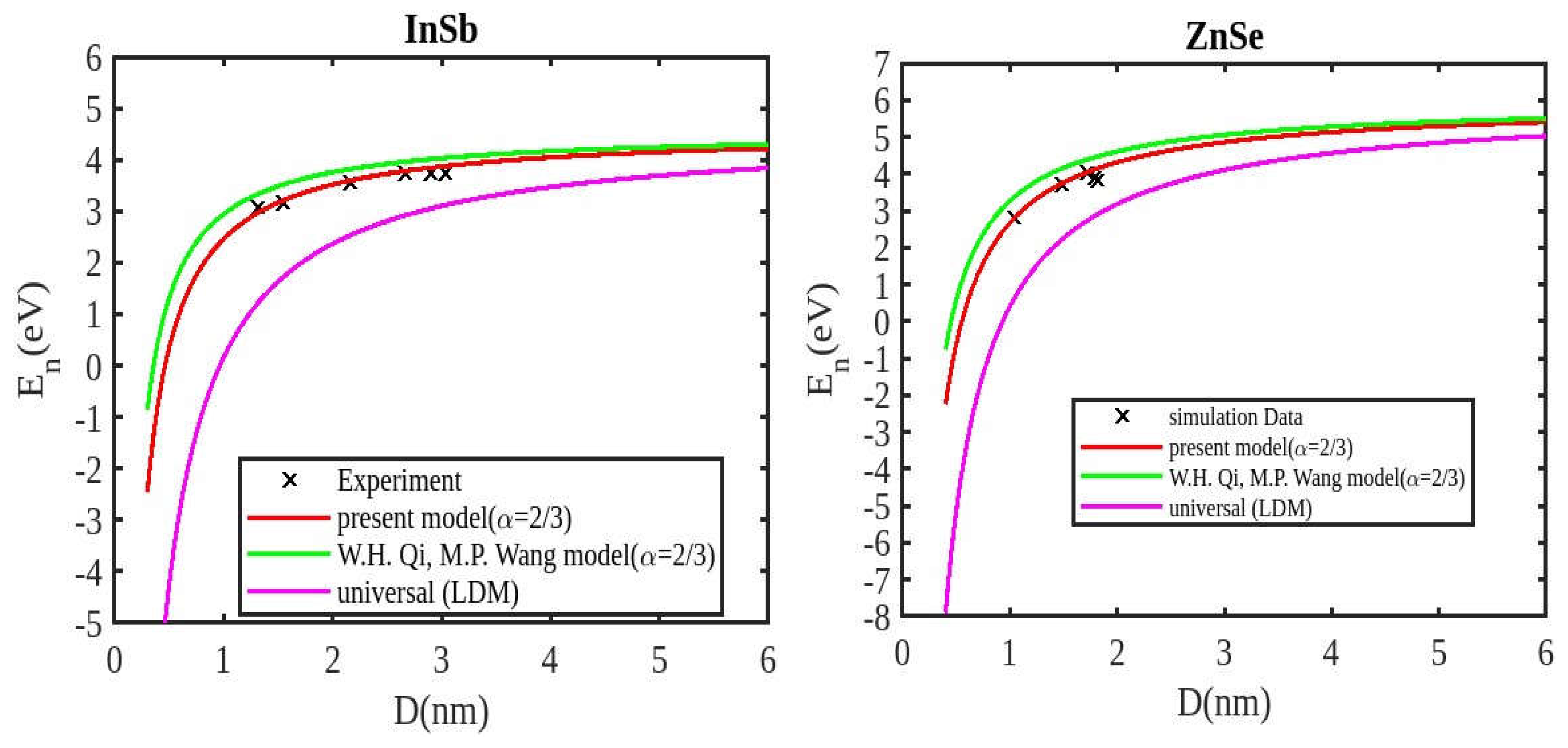

3.1. Cohesive Energy

Equation (12) is used to compute the cohesive energy of the semiconducting nanomaterials for the chosen semiconducting materials, ZnSe, InSb, CdSe, and CdS. The input parameters used for calculations are detailed in

Table 1. The computed results are presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 visually represent the cohesive energy values for various shapes and semiconductor nanomaterials. For comparison, the theoretical results for the cohesive energy of ZnSe, InSb, CdSe, and CdS nanoparticles are presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, along with existing experimental data. The theoretical calculations were performed using both the present model and the universal liquid drop model. The liquid drop model describes the size-dependent cohesive energy using the relation

, where

is the cohesive energy of the nanoparticle,

is the bulk cohesive energy,

is the radius of the nanoparticle, and

is the radius of the one atom(28).

Our unified model demonstrates that the cohesive energy of nanoparticles decreases as their size diminishes, and its results align more closely with experimental values than the universal liquid drop model of shape factor(. The universal liquid drop model tends to underestimate the cohesive energy, whereas our model provides a more accurate prediction. This suggests that our model is more effective in capturing the cohesive energy of nanoparticles. Additionally, the shape of the nano-particle significantly influences this trend, with nanowire shapes showing the least decrement and regular tetrahedral shapes exhibiting the greatest decrement. Furthermore, the cohesive energy of these nano-particles increases with increasing particle size up to approximately below 2nm. The size-dependent behavior of particles below 4 nm is characterized by significant effects of both size and shape. Within this range, the cohesive energy exhibits a strong dependence on particle size and shape. However, as the particle size is above 4nm, the cohesive energy approaches a constant bulk value, indicating that it becomes less sensitive to size and shape variations. The experimental results for the nanowire of InSb nanoparticles in the 2-4 nm region align closely with our theoretical predictions. This suggests that the particles tend to adopt a nanowire shape within this size range. For nanomaterials, CdSe and ZnSe the calculated result for nanowire shape has consistency with previously reported simulation data within the size range of 1-2nm. This also shows that the predicted shape for these nanoparticles is a nanowire in this size range.

Figure 5 displays the theoretical predictions of cohesive energy derived from the proposed model, alongside the existing Qui and Wang model, the universal liquid drop model, experimental data for InSb nanowires, and simulation results for ZnSe nanowires. The findings indicate that the cohesive energy of these nanoparticles reduces as the particle size decreases. The trend observed in our results aligns with those from the Qui and Wang model, as well as with the experimental values. Additionally, our current model’s results are closer to the experimental values, while those from the Qui and Wang model are higher than what was experimentally observed and simulated data. Our model overtakes the Qui and Wang model in accurately predicting the cohesive energy of nanoparticles.

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrates negative cohesive energy, which refers to the energy released when individual atoms or molecules combine to form a nanoparticle structure. In nanoparticles, cohesive energy is typically negative, signifying that energy is generated during their formation rather than consumed. This concept quantifies the bonding strength within a solid material. The negative cohesive energy indicates that the attractive forces between the atoms or molecules in the nanoparticle exceed the energy needed for their assembly, making the nanoparticle structure more stable and energetically favorable compared to isolated atoms or molecules. This phenomenon is partly due to the high surface-to-volume ratio at the nanoscale, where surface atoms experience increased surface energy because they have fewer neighboring atoms. Consequently, this elevated surface energy is reduced, resulting in energy release during nanoparticle formation. The search results show that because of their high surface energy and non-equilibrium conditions, nanoparticles are thermodynamically unstable(34,35). This instability is a basic characteristic of nanoparticles that needs to be taken into account and controlled during their usage and processing.

The figures demonstrate that the cohesive energy predictions from our model for various semiconductor nanoparticles and shapes align with both experimental and simulation results. This suggests that the proposed model, Equation (12), is likely to be accurate in its predictions. The fraction of surface atoms increases dramatically as materials get smaller until they reach the nanoscale relative to bulk materials. There are many unsaturated ionic charges at the surface because of the high number of surface atoms. According to the model, the cohesive energy is lowest for tetrahedral materials and largest for nanowires. Another surface-dependent phenomenon is the cohesive energy’s shape-dependence. The nanowire has a minimal area, while the tetrahedral shape has a somewhat larger surface area. As a result, the tetrahedral surface’s larger atom count causes greater degradation than the nanowire surface’s. The observed behavior supports the validity of our theoretical model, which incorporates voids within the crystal, dangling surface atoms, and the shape factor. This indicates that the cohesive energy of semiconductor nanomaterials is influenced by the combined effects of their packing factor, size, and shape. To effectively design and optimize semiconductor nanomaterials with specific properties, it is crucial to understand how their cohesive energy changes with size.

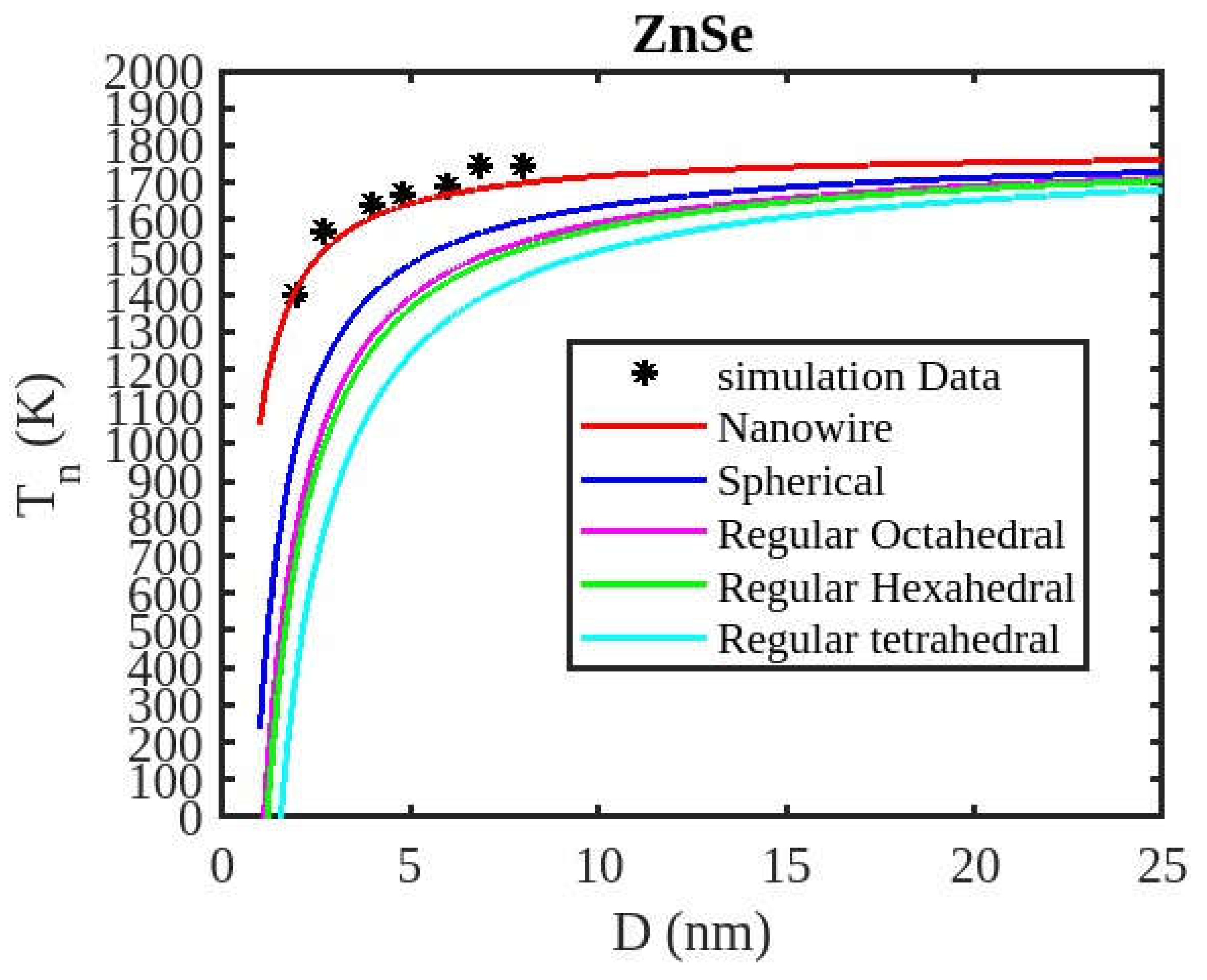

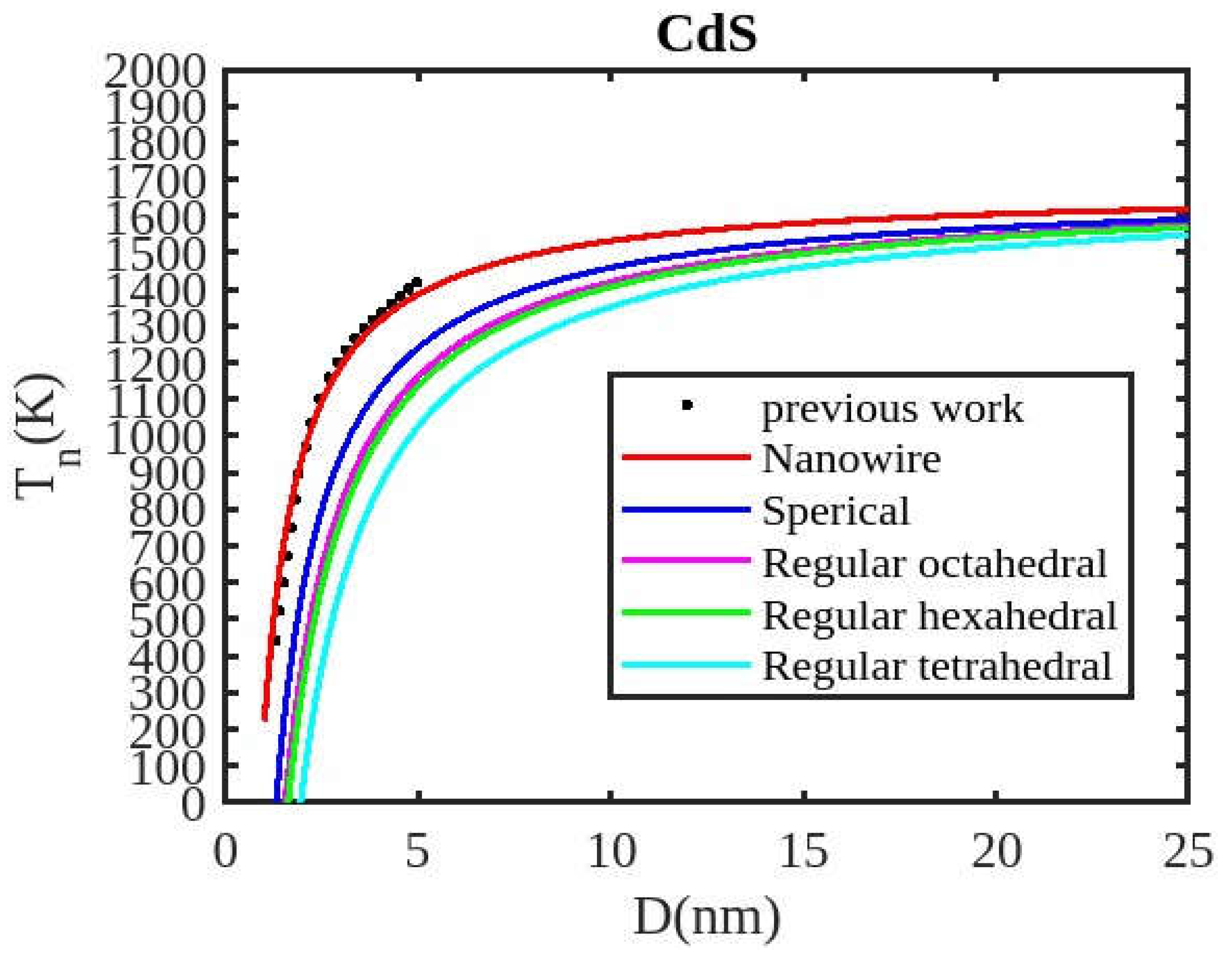

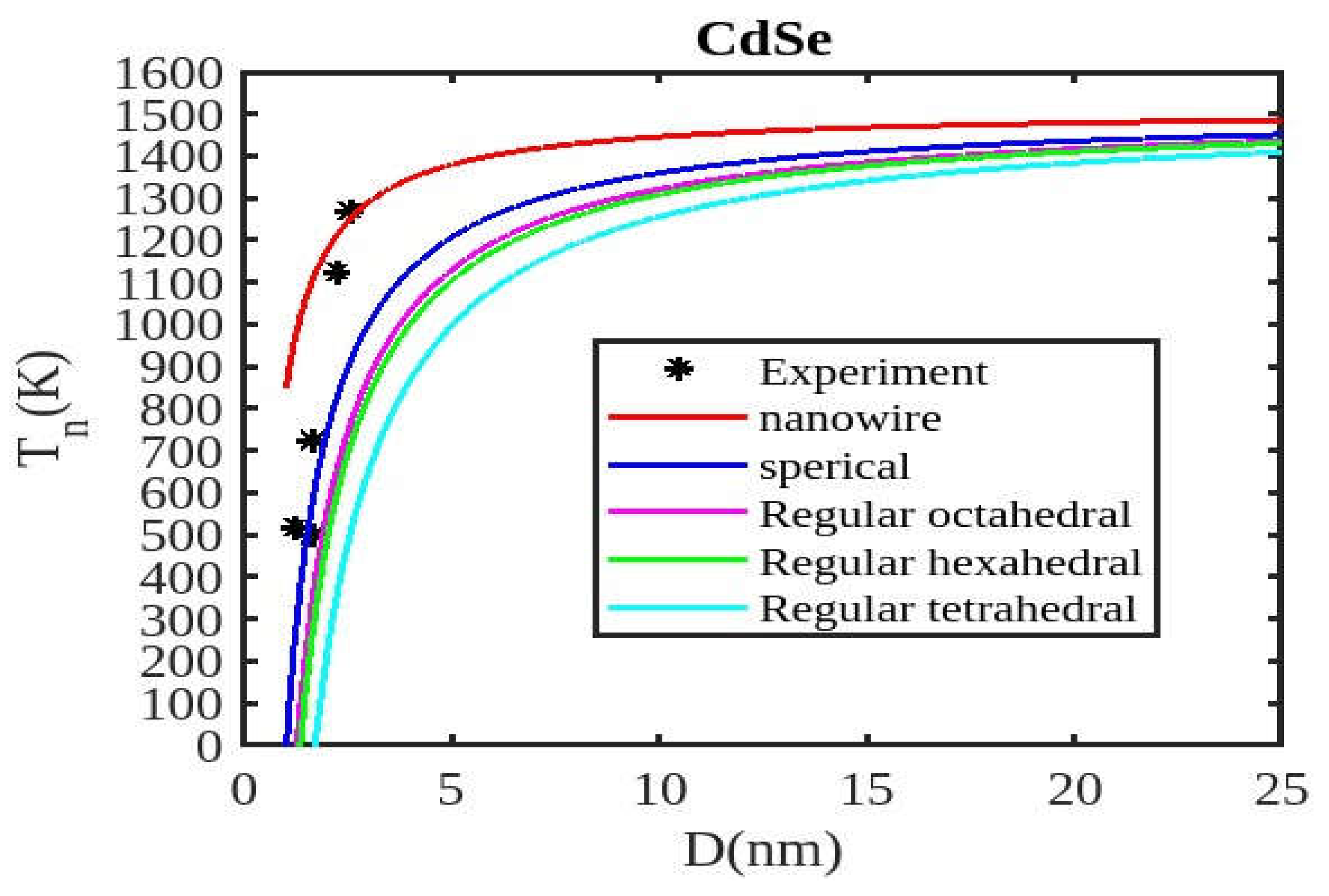

3.2. Melting Temperature

Table 1 lists the bulk material melting temperatures for elements such as ZnSe, CdSe, and CdS. Also, using Equation (13) to calculate the melting temperatures of these materials for various shapes, the results are graphically shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. The presented figures also include available experimental data, modeling data, and previously published data for comparison. The graphs illustrate that as the size of the nanoparticles decreases, their melting temperature also decreases.

Furthermore, it is observed that below a diameter of 5nm, the melting temperature decrease is more marked. At the nanoscale, the shape of a nanoparticle becomes a crucial factor in defining its characteristics. For instance, nanowires exhibit a relatively smaller decrease in melting point compared to tetrahedral nanoparticles, which show a more pronounced decrease. Additionally, the melting points of these nanoparticles increase as the particle size increases up to 10 nm. The size and shape effects are evident in the properties of nanomaterials within the range of less than 5 nm. However, beyond a size of 10 nm, the melting temperature approaches the constant bulk value, indicating that it becomes independent of size and shape. The predicted size-dependent melting point behavior of semiconductor nanomaterials aligns well with experimental findings. Also, it is observed that these materials may exhibit a nanowire structure in the size range of less than 5 nm. The graph in

Figure 7 indicates that for CdS nanoparticles with diameters below 6 nm, the melting temperature variation for nanowires is consistent with previously reported data. The graph in

Figure 8 indicates that for CdSe nanoparticles with diameters below 2 nm, the melting temperature variation for nanowires is consistent with experimental findings.

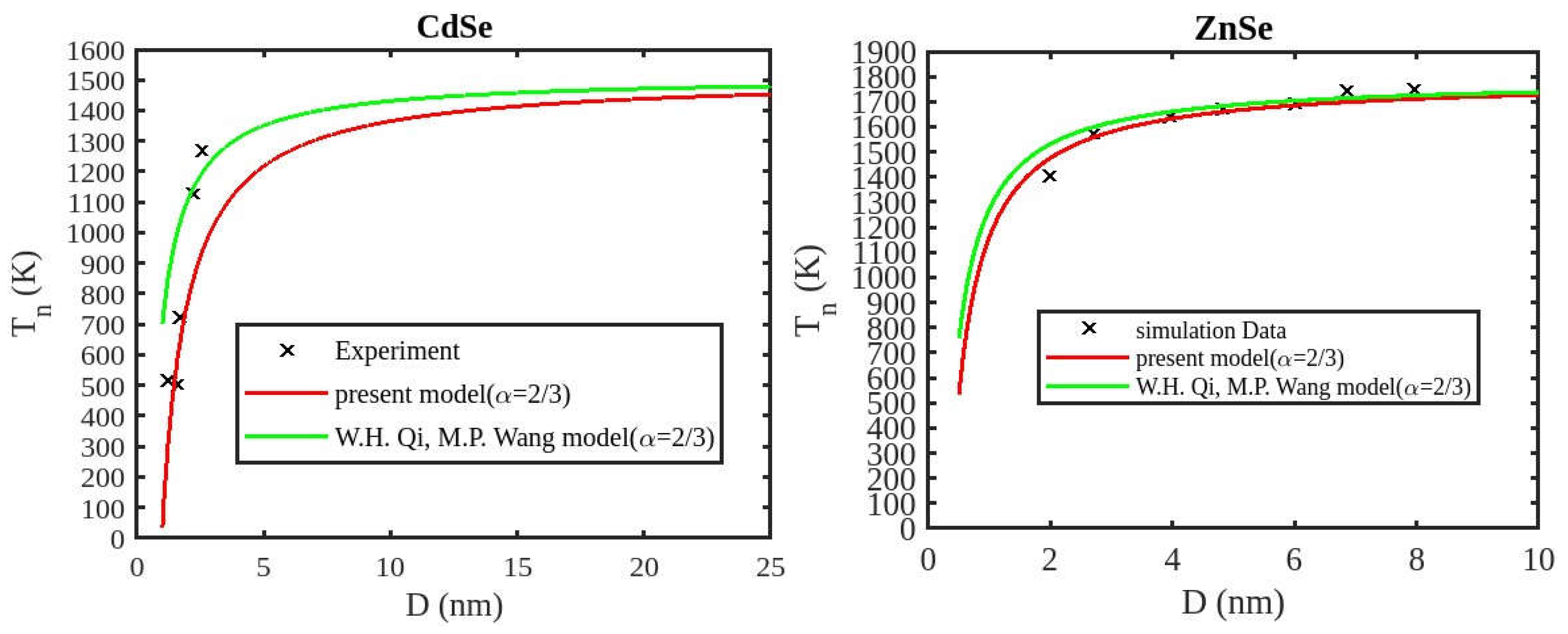

Figure 9 illustrates a comparison between our modified model and the existing theoretical model (Qui and Wang model), along with experimental data for CdSe nanoparticles and simulation results for ZnSe nanoparticles. The findings indicate that the melting temperature of these nanoparticles reduces as the particle size decreases. The trend observed in our results aligns with those from the Qui and Wang model, as well as with the experimental values. Additionally, our present model’s results are closer to the experimental values and simulation data, while those from the Qui and Wang model are higher than the experiment data of the CdSe nanoparticle and simulation data of the ZnSe nanoparticle. The present model overtakes the Qui and Wang model in accurately predicting the cohesive energy of nanoparticles. The relationship between size, shape, and melting point in nanomaterials is readily explained by the direct link between melting point and cohesive energy.

In nanosolids, the surface area is significantly larger compared to bulk materials, resulting in a substantial increase in the number of surface atoms. This high surface-to-volume ratio leads to a distinct change in the energy state of the surface atoms, which in turn affects the cohesive energy. Consequently, a smaller amount of energy is needed for melting, leading to a predicted decrease in the melting point as the size decreases. There also, it is estimated that the nanowire will have the highest melting point, while the tetrahedral shape will have the lowest melting point. The influence of shape can be further understood by considering the relative surface area of different shapes. The tetrahedral shape, in particular, has a relatively larger surface area, while the nanowire shape has the smallest surface area. This means that the tetrahedral shape, with a higher number of atoms on its surface, experiences a greater decrease in comparison to the nanowire shape, which has fewer atoms on its surface. The definition of the shape factor implies that a larger shape factor corresponds to a greater surface area for a given particle size. Thus, the surface effect on the melting temperature of nanoparticles is intensified when the shape factor is larger. This intensification leads to a significant decrease in the melting temperature across a wide range.

Moreover, it has been observed that the impact of particle shape is more pronounced in smaller particles compared to larger ones. Our observation confirms the validity of our model, which considers voids within the crystal, dangling surface atoms, and shape factors simultaneously. Therefore, the thermal stability of a semiconductor nanomaterial is influenced by its packing factor, size, and shape. To effectively design and optimize semiconductor nanomaterials with specific properties, it is crucial to understand how their thermal stability changes with size.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the bond energy model has been expanded comprehensively to include size, shape, and packing efficiency, providing a general approach to investigating thermophysical properties such as cohesive energy and melting point in semiconductor nanoparticles. Our research demonstrates that reducing the size of a material to the nanoscale significantly affects its properties. Furthermore, we observed that the shape of the particle becomes increasingly important for smaller nanoparticles. These changes in behavior are attributed to the dominant influence of surface effects at the nanoscale. Our model’s predictions align well with experimental data, simulations, and existing literature, confirming that the size, shape, surface atom relaxation, and packing efficiency of the crystalline structure influence the physical properties of nanosolids. This consistency demonstrates the model’s ability to predict the thermal stability of semiconductor nanomaterials exactly and the model can be applied to predict thermophysical properties of other nanosolid materials. Gaining insight into how size and shape influence thermophysical properties is vital for efficiently designing and optimizing semiconductor nanomaterials with desired properties.

References

- Nakamura Y, Masada A, Ichikawa M. Quantum-confinement effect in individual Ge1− xSnx quantum dots on Si (111) substrates covered with ultrathin SiO2 films using scanning tunneling spectroscopy. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;91(1). [CrossRef]

- Johnson JC, Yan H, Yang P, Saykally RJ. Optical cavity effects in ZnO nanowire lasers and waveguides. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107(34):8816–28. [CrossRef]

- Ishibe T, Tomeda A, Watanabe K, Kamakura Y, Mori N, Naruse N, et al. Methodology of thermoelectric power factor enhancement by controlling nanowire interface. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(43):37709–16. [CrossRef]

- Zheng N, Stucky GD. A general synthetic strategy for oxide-supported metal nanoparticle catalysts. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(44):14278–80. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava S, Singh P, Pandey AK, Dixit CK. Melting Temperature of Semiconducting Nanomaterials at different Shape and Size. Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects. 2023;36:101067. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal RL, Pandey BK, Mishra D, Fatma H. Thermo-physical Behavior of Nanomaterials with the Change in Size and Shape. Int J Thermodyn. 2021;24(1):1–7. [CrossRef]

- Gharbani P, Mehrizad A, Mosavi SA. Optimization, kinetics and thermodynamics studies for photocatalytic degradation of Methylene Blue using cadmium selenide nanoparticles. npj Clean Water. 2022;5(1):34. [CrossRef]

- Pandey AK, Srivastava S, Dixit CK, Singh P, Tripathi S. Shape and size dependent thermophysical properties of nanomaterials. Iran J Sci. 2023;1–15. [CrossRef]

- Pandey AK, Dixit CK, Srivastava S. Theoretical model for the prediction of lattice energy of diatomic metal halides. J Math Chem. 2023;1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kumari T, Pandey BK, Gupta J, Jaiswal RL, Shukla S. Unified model for the prediction of thermophysical properties of nanometals. Solid State Commun. 2023;371:115254. [CrossRef]

- Sherka GT, Berry HD. Insight into impact of size and shape on optoelectronic properties of InX (X= As, Sb, and P) semiconductor nanoparticles: a theoretical study. Front Phys. 2024;12:1447997. [CrossRef]

- Pandey BK, Jaiswal RL. Dimensional effect on cohesive energy, melting temperature and Debye temperature of metallic nanoparticles. Phys B Condens Matter. 2023;651:414602. [CrossRef]

- Mody V V, Siwale R, Singh A, Mody HR. Introduction to metallic nanoparticles. J Pharm bioallied Sci. 2010;2(4):282–9. [CrossRef]

- Adekoya JA, Ogunniran KO, Siyanbola TO, Dare EO, Revaprasadu N. Band structure, morphology, functionality, and size-dependent properties of metal nanoparticles. Noble Precious Met Nanoscale Eff Appl. 2018;15–42.

- Wei Y, Liu X-P, Mao C, Niu H-L, Song J-M, Jin B-K. Highly sensitive electrochemical biosensor for streptavidin detection based on CdSe quantum dots. Biosens Bioelectron. 2018;103:99–103. [CrossRef]

- Zhu D, Ye H, Zhen H, Liu X. Improved performance in green light-emitting diodes made with CdSe-conjugated polymer composite. Synth Met. 2008;158(21–24):879–82. [CrossRef]

- Nedelcu G. The heating study of two types of colloids with magnetite nanoparticles for tumours therapy. Dig J Nanomater Biostructures. 2008;3(2):99–102.

- Dukes III AD, Pitts CD, Kapingidza AB, Gardner DE, Layland RC. Comparison of the observed size-dependent melting point of CdSe nanocrystals to theoretical predictions. Eur J Chem. 2018;9(1):39–43.

- Bachels T, Güntherodt H-J, Schäfer R. Melting of isolated tin nanoparticles. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;85(6):1250. [CrossRef]

- Kim HK, Huh SH, Park JW, Jeong JW, Lee GH. The cluster size dependence of thermal stabilities of both molybdenum and tungsten nanoclusters. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;354(1–2):165–72. [CrossRef]

- Rui Z, Krivyakin GK, Antonenko AK, Stoffel M, Rinnert H, Vergnat M. On the Formation of IR-Light-Emitting Ge Nanocrystals in Ge: SiO {sub 2} Films. Semiconductors. 2018;52(9). [CrossRef]

- Spesivtsev E V, Rykhlitsky S V, Shvets VA, Chikichev SI, Mardezhov AS, Nazarov NI, et al. Time-resolved microellipsometry for rapid thermal processes monitoring. Thin Solid Films. 2004;455:700–4. [CrossRef]

- Xu Q, Sharp ID, Yuan CW, Yi DO, Liao CY, Glaeser AM, et al. Large melting-point hysteresis of Ge nanocrystals embedded in SiO 2. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97(15):155701. [CrossRef]

- Qi WH, Wang MP. Size and shape dependent melting temperature of metallic nanoparticles. Mater Chem Phys. 2004;88(2–3):280–4. [CrossRef]

- Shi FG. Size dependent thermal vibrations and melting in nanocrystals. J Mater Res. 1994;9:1307–13. [CrossRef]

- Qi WH, Huang BY, Wang MP, Li Z, Yu ZM. Generalized bond-energy model for cohesive energy of small metallic particles. Phys Lett A. 2007;370(5–6):494–8. [CrossRef]

- Guisbiers G, Mendoza-Cruz R, Bazán-Díaz L, Velázquez-Salazar JJ, Mendoza-Perez R, Robledo-Torres JA, et al. Electrum, the gold–silver alloy, from the bulk scale to the nanoscale: synthesis, properties, and segregation rules. ACS Nano. 2016;10(1):188–98. [CrossRef]

- Vanithakumari SC, Nanda KK. A universal relation for the cohesive energy of nanoparticles. Phys Lett A. 2008;372(46):6930–4. [CrossRef]

- Shanker J, Kumar M. Studies on melting of alkali halides. Phys status solidi. 1990;158(1):11–49. [CrossRef]

- Qi WH, Wang MP, Xu GY. Comment on “Size effect on the lattice parameters of nanoparticles.” J Mater Sci Lett. 2003;22:1333–4. [CrossRef]

- Qi WH. Size effect on melting temperature of nanosolids. Phys B Condens Matter. 2005;368(1–4):46–50. [CrossRef]

- Mishra S, Pandey BK, Jaiswal RL, Gupta J. Unified model for the studies of band gap of nanosolids with their varying shape and size. Chem Phys Lett. 2024;141177. [CrossRef]

- Kittel C, McEuen P. Introduction to solid state physics. John Wiley & Sons; 2018.

- Mansouri E, Mesbahi A, Hamishehkar H, Montazersaheb S, Hosseini V, Rajabpour S. The effect of nanoparticle coating on biological, chemical and biophysical parameters influencing radiosensitization in nanoparticle-aided radiation therapy. BMC Chem. 2023;17(1):180. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Kim C, Schmucker D, Lee SSS, Liao S, Cápiro NL, et al. Delineating the role of surface grafting density of organic coatings on the colloidal stability, transport, and sorbent behavior of engineered nanoparticles. Environ Sci Nano. 2024;11(2):578–87. [CrossRef]

- Singh M, Phantsi TD. Bond theory model to study cohesive energy, thermal expansion coefficient and specific heat of nanosolids. Chinese J Phys. 2018;56(6):2948–57. [CrossRef]

- Vogel AT, de Boor J, Becker M, Wittemann J V, Mensah SL, Werner P, et al. Ag-assisted CBE growth of ordered InSb nanowire arrays. Nanotechnology. 2010;22(1):15605. [CrossRef]

- Lockwood DJ, Yu G, Rowell NL. Optical phonon frequencies and damping in AlAs, GaP, GaAs, InP, InAs and InSb studied by oblique incidence infrared spectroscopy. Solid State Commun. 2005;136(7):404–9. [CrossRef]

- Poole CP, Owens FJ. Introduction to nanotechnology. 2003;

- Berry HD, Zhang Q. Theoretical investigation of size and shape dependent melting temperature of transition metal clusters. Solid State Commun. 2023;376:115357. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Tang L-M, Ning F, Wang D, Chen K-Q. Structural stability and electronic properties of InSb nanowires: A first-principles study. J Appl Phys. 2015;117(12). [CrossRef]

- Ovsiannikova LI. Atomic structure and cohesion energy of ZnSe and CdSe clusters. Phys Solid State. 2019;61:673–9. [CrossRef]

- Sengul S, Dalgic SS. Size dependence of melting process of ZnSe nanowires: molecular dynamics simulations. J Optoelectron Adv Mater. 2011;13(November-December 2011):1542–7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).