1. Introduction

Obesity can be considered as an abnormal state of lipid metabolism. The number of obese people is increasing in developed and even developing countries day-by-day. Numerous fatal illnesses, including ischemic heart disease, hypertension, stroke, type 2 diabetes, cancer, hyperlipidaemia, and osteoarthritis, can be brought on by obesity [

1,

2,

3]. The etiology of obesity is multi-factorial. The body mass index, estimated by measuring weight of body in kilograms and then dividing by the square meter of height of that person, correlates highly with the amount of body fat. Persons having BMI value between 25 and 30 kg/m

2 are defined as overweight and those having BMI more than 30 kg/m

2 are considered obese. This condition is treated with a variety of ways, including nutritional counseling, lifestyle changes, medications, and, in extreme cases, stomach surgery [

4]. Treatment of the obese condition by pharmacological means or surgical interventions, though used in some cases, is not always appropriate. Unfortunately, despite the short-term benefits, drug treatment for obesity is frequently associated with rejuvenating weight gain after halting the medication, medication side effects and the possibility of drug misuse. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 80 percent people in the world currently consume herbal medications made from plant extracts for some aspect of routine medical care [

1]. One of the cutting-edge methods for the treatment of obesity is the exploitation of natural components from medicinal plants as plant extracts or functional foods. For a long time, the extract of

Piper longum.L, Vitis vinifera, Lagerstroemia speciosa, Citrus aurantium, Piper nigrum, Phyllanthus emblica, Zingiber officinale, Allium cepa are used for traditional remedy preparation for the treatment of obesity [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The anti-obesity effect by different plant extract proceeds by an increase of energy expenditure [

12,

13,

14], suppression of appetite [

15,

16,

17] or interference of digestive lipase enzyme in the gastrointestinal tract [

18,

19]. The mechanism of induction of obesity is highly regulated by the adipogenic process of the fat cells. Different mechanisms are involved in the adipogenic process of adipocytes [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The anti-obesity action of some of the plants has been published in several articles [

25,

26] while the detailed mechanism of action has not been explored in many cases.

In folk medicine, extracts of

Syzygium cumini and

Dioscoria bulbifera plants are used

as anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, anti-bacterial, antioxidant, anti-allergic, and anticancer in traditional medicine. Traditionally, they have been used for the cure of skin diseases, itching, scabies, and eczema [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Polyphenols are an important class of compounds that act as an antioxidant, anti-cancer, and anti-obese agents [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Different types of phenolic compounds have been reported in these plants [

27,

38,

39,

40]. Literature review indicates that

Syzygium cumini but not

Dioscoria bulbifera shows the antioxidant and anti-obesity effect [

41,

42] though the inhibitory mechanism of the lipase enzyme by the phytochemicals of these plants has not been explored. With a credible assessment of their mechanism of action, we are particularly interested in evaluating the anti-obesity effect of these plant extracts by integrating the pharmacological response with molecular docking approach.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Extraction of the Plants

After collection, the fruits of the Syzygium cumini and the whole plant, Dioscoria bulbifera were identified by the Department of Botany, University of Dhaka, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh. The seeds of Syzygium cumini were chopped, sun-dried, crushed into powder, and steeped (600 grams) for 7 days in 2 L of ethanol at room temperature with intermittent shaking. The roots of Dioscoria bulbifera was, on the other hand, also chopped into small pieces, dried in the sun, ground into powder, soaked (650 gm) for 7 days in 2.5 L ethanol with infrequent shaking at RT. The extracts were filtered with cotton filter with subsequent filtration by paper filter. The filtrates were vaporized to dryness with the help of rotary evaporator at reduced pressure, and the dry extracts were stored at 4 °C.

2.2. Determination of Total Phenolic Content of the Extract

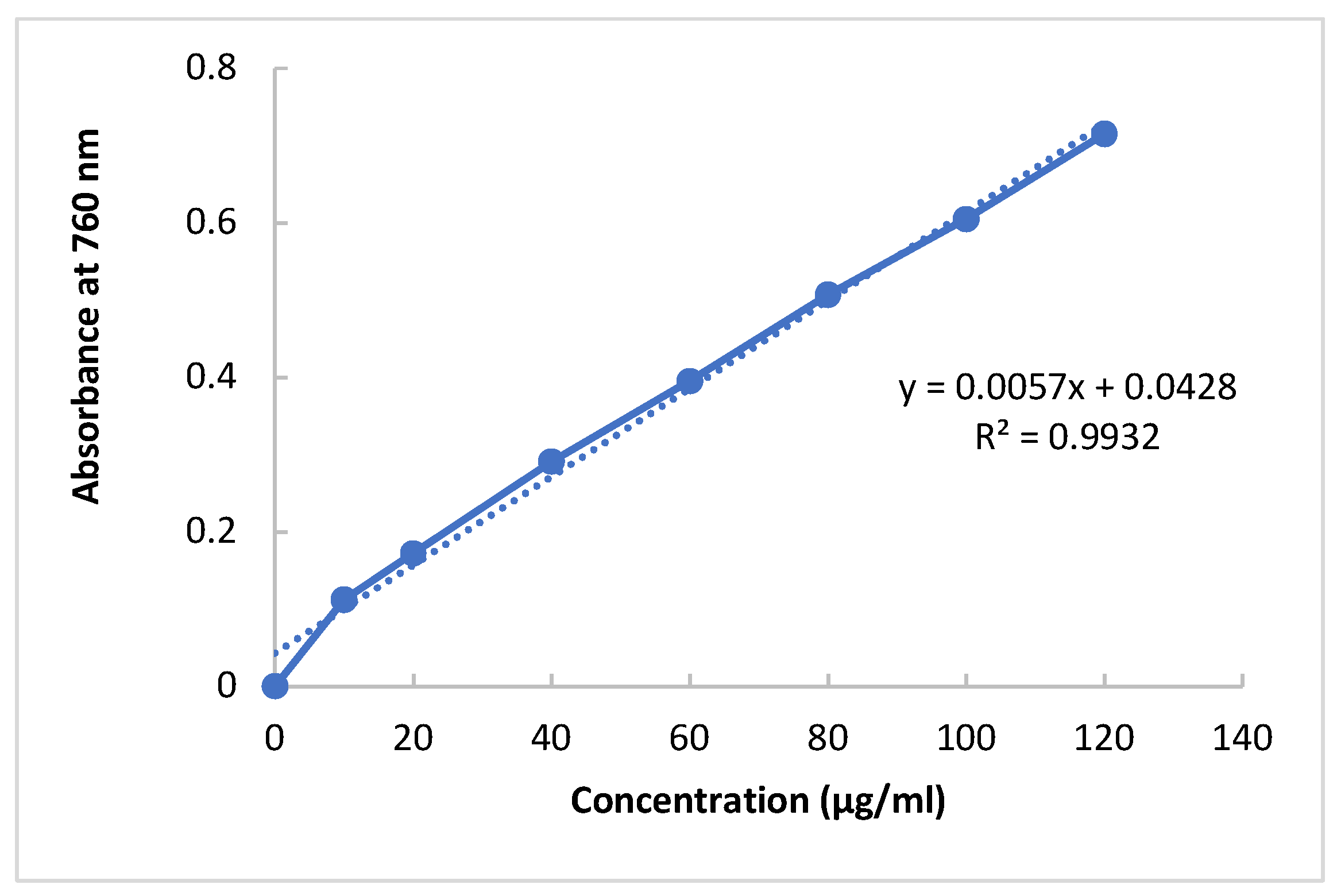

With a few minor adjustments, the prior approach reported by Ainsworth et al. [

43] was used to estimate the content of total phenolic compopounds of the two plant extracts. To prepare the calibration curve, 0.2 ml aliquots of 0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, and 400 μg/ml Gallic acid solutions was blended with one milliliter of 5-fold diluted Folin Ciocalteu reagent. A volume of 0.8 ml of 75 mg/ml sodium carbonate solution was added to each of the above reaction mixture after five minutes. A UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Model: UV2600i) was used to measure the absorbance of the reaction mixture at 760 nm after it was held at room temperature and occasionally stirred in the dark. For sample analysis, 0.2 ml of the ethanolic extract of the plants (1 gm/100 ml) was admixed with the above reagent as described early. The reaction mixture’s absorbance was measured after 30 minutes in order to estimate the total phenolic contents of the plant extracts [

43].

2.3. Determination of the Antioxidant Activity

The in vitro free radical scavenging ability of the plant extracts was assessed using 2,2′- diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) following the previously described method [

44] with some modification. A solution of DDPH having a concentration of 0.1 mM was prepared by dissolving sufficient amount in methanol and was used as scavanging agent. Various concentration of plant extract (0.0078125 – 0.5 mg/ml) was prepared in methanol with serial dilution. One milliliter of DDPH solution was blended with 1 ml of plant extract of each concentration to dilute the DPPH solution twice. The solution was mixed vigorously and kept in a dark place at RT for 20 min. Then the absorbance of all the above solution was estimated at 517 nm using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Model: UV2600i). Without any sample, the control (butylated hydroxytoluene, or BHT) was made as described above. Based on the proportion of DPPH radical scavenged activity (%DRSA), the free radical scavenging activity was computed using the equation described earlier [

44]. The IC

50 value was estimated from the graph from percentage inhibition versus concentration.

2.4. Composition of Foods Used in This Study

For the evaluation of plant extract on high fat diet induced obese rats we used normal laboratory chow food and high fat diet (HFD). The experimental HFD was formulated according to the method described earlier [

45].

2.5. Effect of the Ethanolic Extracts of the Plants on Body Weight of Rat

To check the anti-obese effect of the plant extracts, we collected 30 white albino Wister rats (age 8-9 weeks, average weight 110±8 gm) from the Department of Pharmacy, Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka. The rats were allocated into five groups (each group contained 6 rats) and maintained in a normal environment for 7 days to adapt to the environment with a normal diet. The first group represented the control group fed only normal diet, the second group represented high fat diet (HFD) group fed with HFD. The third, fourth and fifth group were fed with HFD along with S. cumini extract (500 mg/kg bw), D. bulbifera extract (500 mg/kg bw) and orlistat (10 mg/kg), respectively for 12 weeks. The weight of each rat of each group was measured at the starting time of the experiment and every week. All of the rats were sacrificed after 12 weeks, and blood was drawn to analyze various blood parameters. The experimental methods used here were approved by the Institutional Animals Ethics Committee (IEAC) of the State University of Bangladesh.

2.6. Anti-Lipase Activity of the Extract

The in vitro anti-lipase activity of the plant extract was performed following the published method with some modifications [

46,

47]. For bioassays, 0.1 gm of ethanolic extract of each plant was taken and dissolved in a sufficient volume of phosphate buffer having pH 7.2 and diluted to 100 ml to make the concentration at 1 mg/ml. 0.05gm of PPL was dissolved in potassium phosphate buffer (10 mL) having p

H 6.0 and diluted to 50 ml to make the final concentration at 1mg/ml. 495 microliter of potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM) having p

H 7.2 is taken in a clean vial and 5 microliters of PNPB (density 1.19 gm/mL) solution is added to it to make the substrate concentration at 56.9 mM. One milliliter of PPL solution was then blended with one milliliter of plant extract or standard orlistat (1 mg/ml). The reaction mixer was then incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. After 30 min incubation at 37

0C, 20 µl of the substrate (PNPB) solution was mixed to each of the test tube followed by further 10 min incubation. The absorbance of each the solution was taken at 405 nm using a spectrophotometer

(UV-1800, Shimadzu, Japan

). The process was performed in triplicates and the values were used to calculate the antilipase activity using equation described earlier [

47].

2.7. Measurement of Serum Total Cholesterol, Triacylglycerol, LDL and HDL

The rats were sacrificed and their blood was obtained after 12 weeks. The serum was recovered from the blood sample by centrifuging it at 10,000 rpm. Then different lipid parameters such as Triglycerides, Cholesterol, HDL, and LDL level were determined by using different reagents (PLASMA TEC, UK) in Humalyzer 3000. For determination of total cholesterol and TG, 10 µl of serum and 10 µl of standard (cholesterol/TG) were taken in separate test tubes. One milliliter of the cholesterol/TG reagent (R) was taken in each of the above test tube. The reaction mixer was incubated for 5 min at 37 0C. In a separate tube, only one milliliter of Cholesterol/TG working reagent was taken as blank. All the samples, standard and blank were shaken well before taking data using a blood analyzer machine, Humalyzer 3000.

In contrast, for the determination of LDL and HDL, 100 µl of serum and 100 µl of standard (LDL/HDL) were taken in separate test tubes. One milliliter of the LDL/HDL reagent (R) was taken in each of the above test tube. The reaction mixer was incubated for 5 min at 37 0C. In a separate tube, only one milliliter of LDL/HDL working reagent was taken as blank. All the samples, standard and blank were shaken well before taking data using Humalyzer 3000, a blood analyzer machine.

2.8. Molecular Docking Study of Polyphenols and Rat Lipase

The crystal structure of the rat pancreatic lipase was obtained from the protein database (PDB ID: 1BU8). It was cleaned and optimized using PyMol & SWISS Pdb Viewer software respectively. The structures of different reported phenolic compounds reported in the plants extracts were recovered from the PubChem database followed by Geometrical Optimization of polyphenol structures using PM6 method with the help of Gaussian 09 software. Finally AutoDock Vina v1.1.2 software was used to study the molecular docking between the polyphenols and rat lipase [

48]. The active site of the rat pancreatic lipase was designated as the center grid and acquired by eliminating the ligand. The dimensions of the center of grid box was chosen to comprise all the atoms present in the ligand. The grid box in pancreatic lipase was customized at 8.5479, 5.2696, and 33.81A ° (for x, y and z) through a grid line of 68.872911911, 67.1358690262, and 69.8130127585 points (for x, y and z). The interactions between the polyphenols and the amino acids of the lipase enzyme defined as binding affinity (Kcal/- mol) was studied.

3. Result and Discussions

The yield of the dry extracts of Syzygium cumini and Dioscoria bulbifera were 13.5% (w/w) and 10.82% (w/w) respectively. The color of the dry extract of Syzygium cumini was greenish black while that of Dioscoria bulbifera was greenish brown.

3.1. Total Phenolic Content of the Plant Extracts

Naturally approximately 8,000 phenolic compounds have been reported [

49]. Among them, many phenolic compounds show antioxidants or free radical scavengers activity [

27,

28,

29,

31,

32]. Consequently, it is logical to estimate the total phenolic compounds available in the ethanol extracts of

Syzygium cumini and

Dioscoria bulbifera. Despite the availability of different techniques, Folin-Ciocalteu method has been considered more acceptable method for the determination of phenolic compounds in plant extracts compared to other methods. In the present experiment, due to the reaction between polyphenolics available in the extracts and Folin-Ciocalteau reagent, a blue-colored solution of complex phospho-molybdic-phosphotungstic-phenol is formed that absorbance is measured at 760 nm. Ethanolic extracts of

Syzygium cumini and

Dioscoria bulbifera were examined at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL each. The phenolic contents of the plant extract were computed usng the regression equation obtained from the calibration line (R

2 =0.9932,

y = 0.0057

x + 0.0428) in GAE as mg/g of the extrac). The total phenolic compounds available in the ethanolic extracts of

Syzygium cumini and

Dioscoria bulbifera are 103.79±3.45 and 69.31 ± 2.99 mg GAE/g dry fraction, respectively.

Figure 1.

Calibration curve of gallic acid.

Figure 1.

Calibration curve of gallic acid.

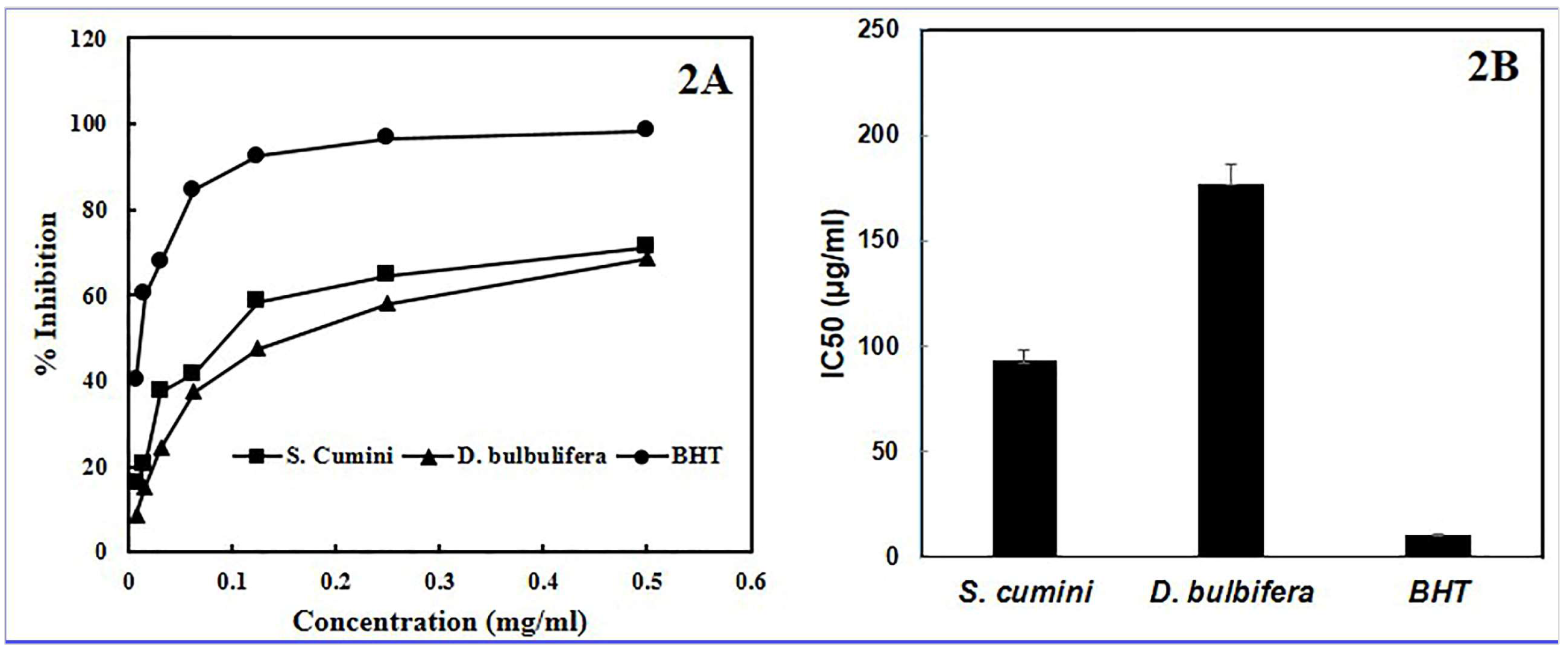

3.2. Antioxidant Activity of the Plant Extracts

For the measurement of antioxidant effect of different plant extracts and purified substances, organic radical DPPH has been extensively used [

28,

29,

31,

32,

44]. The antioxidant capacity to scavenge DPPH radicals is considered to be related to their ability to donate hydrogen [

50]. Following the receiving of a hydrogen atom or an electron, a more stable diamagnetic molecule produced that shows absorption at at 517 nm. The radical scavenging capacity of sample is inversely proportional to the residual DPPH [

44]. In the present study, both the extracts exhibited moderate to good antioxidant activity while comparing the activity with that of DPPH radical. The IC

50 value of ethanol extract of

S. cumini,

D. bulbifera and BHT was 93.03±6.23, 177.13±7.52, and 10.84±0.92 µg/mL, respectively.

Figure 2.

Anti-oxidant activity (A) and IC50 value (B) of S. cumini, D. bulbifera extract and BHT.

Figure 2.

Anti-oxidant activity (A) and IC50 value (B) of S. cumini, D. bulbifera extract and BHT.

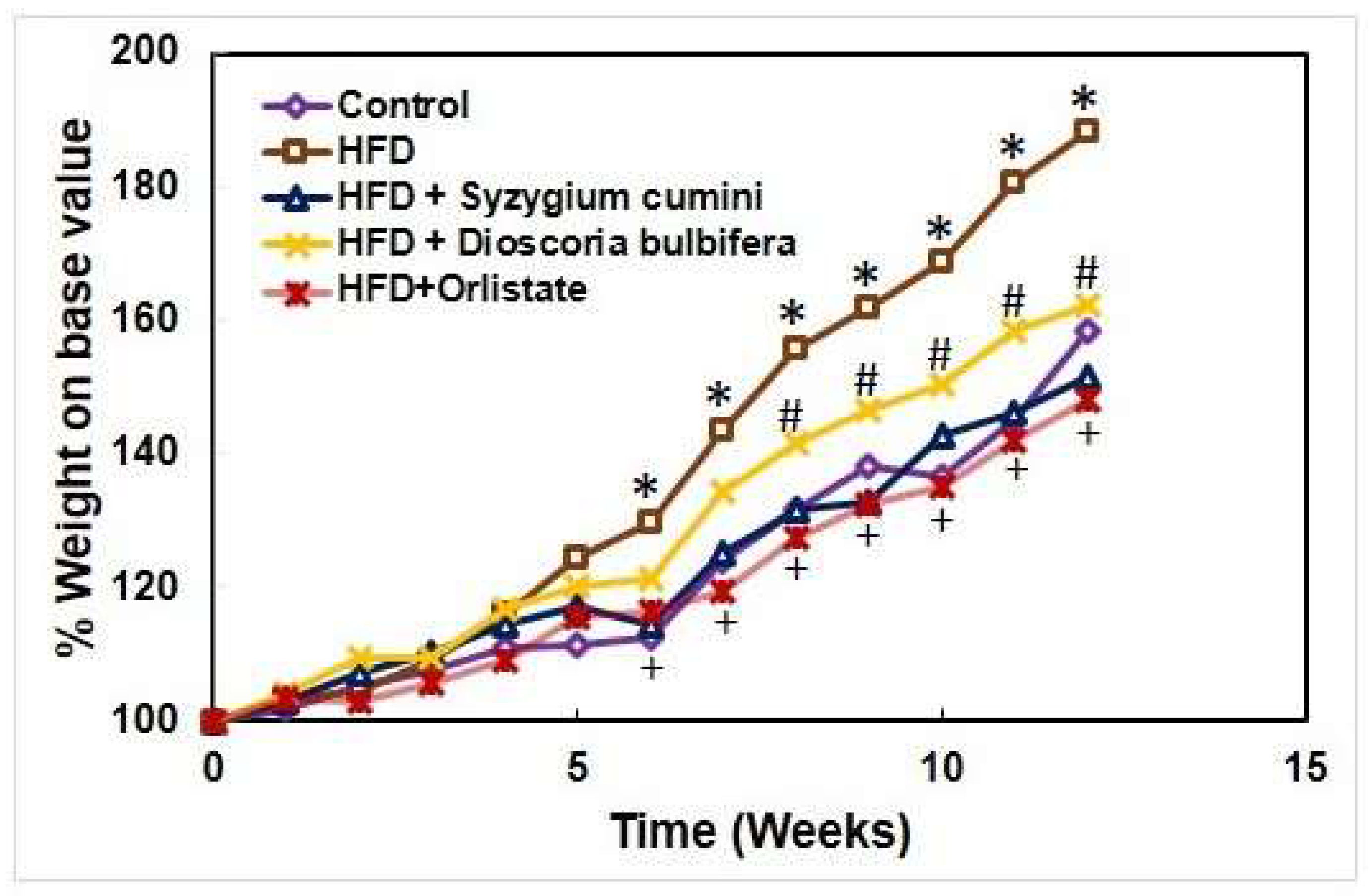

3.3. Effect of the Ethanolic Extracts of the Plants on Body Weight on High Fat Diet Induced Rat

To evaluate the anti-obesity effect of ethanolic extracts of

S. cumini,

D. bulbifera, rats were fed with diet containing high amount of fat in the presence or absence of the plant extract with a dose of 500 mg per kg body weight. The body weight of individual rat in each group was measured every week for a total period of 12 weeks. As shown in

Figure 4, the body weight gained by the HFD fed group was substantially higher after 5 weeks compared to the control group. However, the body weight gained was markedly decreased by

S. cumini ethanolic extract fed rats from 6 weeks while

D. bulbifera ethanolic extract was also able to decrease the body weight significantly from 8 weeks. On the other hand, Orlistat at a dose of 10 mg per kg body weight was highly efficient to reduce the total body weight of the rats from 6 weeks.

Figure 3.

Effect of the ethanolic extracts of S. cumini, D. bulbifera and Orlistat on body weight on high fat diet induced rat.

Figure 3.

Effect of the ethanolic extracts of S. cumini, D. bulbifera and Orlistat on body weight on high fat diet induced rat.

Figure 4.

Effect of the ethanolic extracts of S. cumini, D. bulbifera, and Orlistat on body weight on high fat diet induced rat.

Figure 4.

Effect of the ethanolic extracts of S. cumini, D. bulbifera, and Orlistat on body weight on high fat diet induced rat.

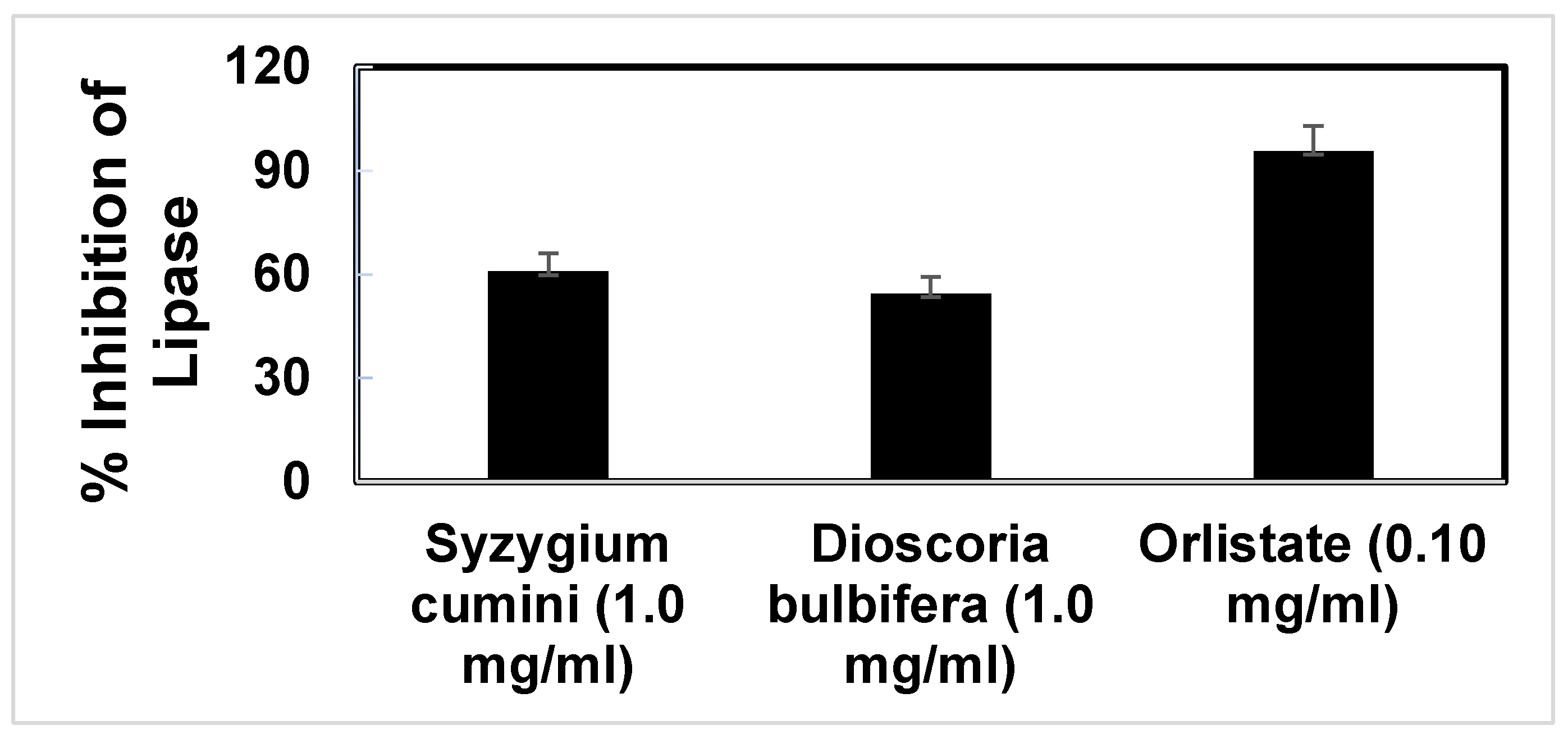

3.4. Anti-Lipase Activity of the Extract

The pancreatic lipase enzyme, efficient in the digestion of lipids, is produced and secreted as digestive juice from the pancreas. It is known to hydrolyze 50 to 70 percent of the total ingested nutritional lipids. As a result, anti-lipase induced anti-obesity effect is a widely used tool for the evaluation of natural products as anti-obesity agents [

51,

52]. Orlistat, a potent pancreatic lipase enzyme inhibitor, is extensively used for the treatment of obesity by interfering the lipid digestion in gastrointestinal tract [

53]. Our experimental study showed that Orlistat could be able to inhibit 95.71% activity of the Porcine pancreatic lipase when the concentration of the drug was 0.1 mg/ml. On the other hand, the ethanolic extract of

S. cumini,

D. bulbifera showed 60.84% and 54.59% of anti-lipase activity against Porcine pancreatic lipase.

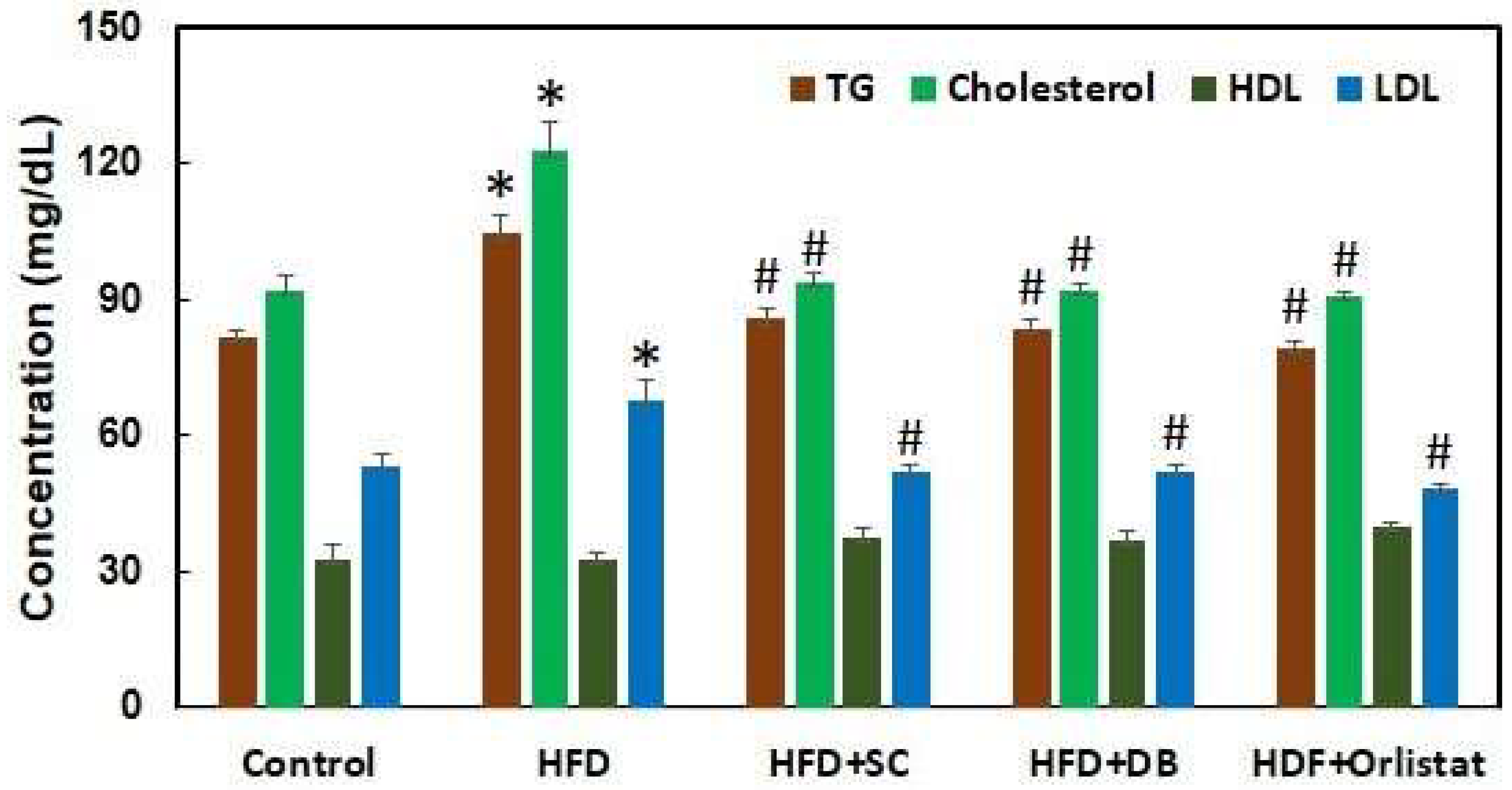

3.5. Lipid Profiling of the Extract Treated Rats

Figure 6 illustrates the plasma cholesterol, triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels in various groups of rats: control, high-fat diet (HFD)-induced, S. cumini-treated, D. bulbifera-treated, and Orlistat-treated rats following 12 weeks of treatment. Rats in the HFD-induced group exhibited significant increases in plasma cholesterol, TG, and LDL levels, while HDL levels remained unchanged. Specifically, after 12 weeks, HFD-fed rats showed a notable 51.03% increase in cholesterol, a 28.34% increase in TG, and a 28.69% increase in LDL compared to the control group. In contrast, treatment with extracts from S. cumini and D. bulbifera at a dose of 500 mg/kg body weight, as well as Orlistat at 10 mg/kg body weight, significantly reduced plasma cholesterol, TG, and LDL levels in HFD-induced rats, effectively bringing these levels back to those of the control rats. This outcome strongly suggests that the plant extracts and Orlistat exerted lipid-lowering effects comparable to standard treatment, possibly through the inhibition of lipase activity responsible for fat digestion in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT).

These results underscore the potential therapeutic efficacy of S. cumini and D. bulbifera extracts in mitigating lipid abnormalities associated with HFD-induced obesity. By restoring lipid profiles to normal levels akin to those seen in non-obese rats, these plant extracts demonstrate promise as natural alternatives for managing dyslipidemia and related cardiovascular risks. Further investigation into the underlying mechanisms and long-term effects of these extracts could pave the way for their development into clinically validated treatments for obesity-related disorders, offering a holistic approach to combating metabolic disturbances and promoting cardiovascular health.

Figure 5.

Effect of ethanolic extract of Syzygium cumini and Dioscoria bulbifera extract on high fat diet induced obese rat.

Figure 5.

Effect of ethanolic extract of Syzygium cumini and Dioscoria bulbifera extract on high fat diet induced obese rat.

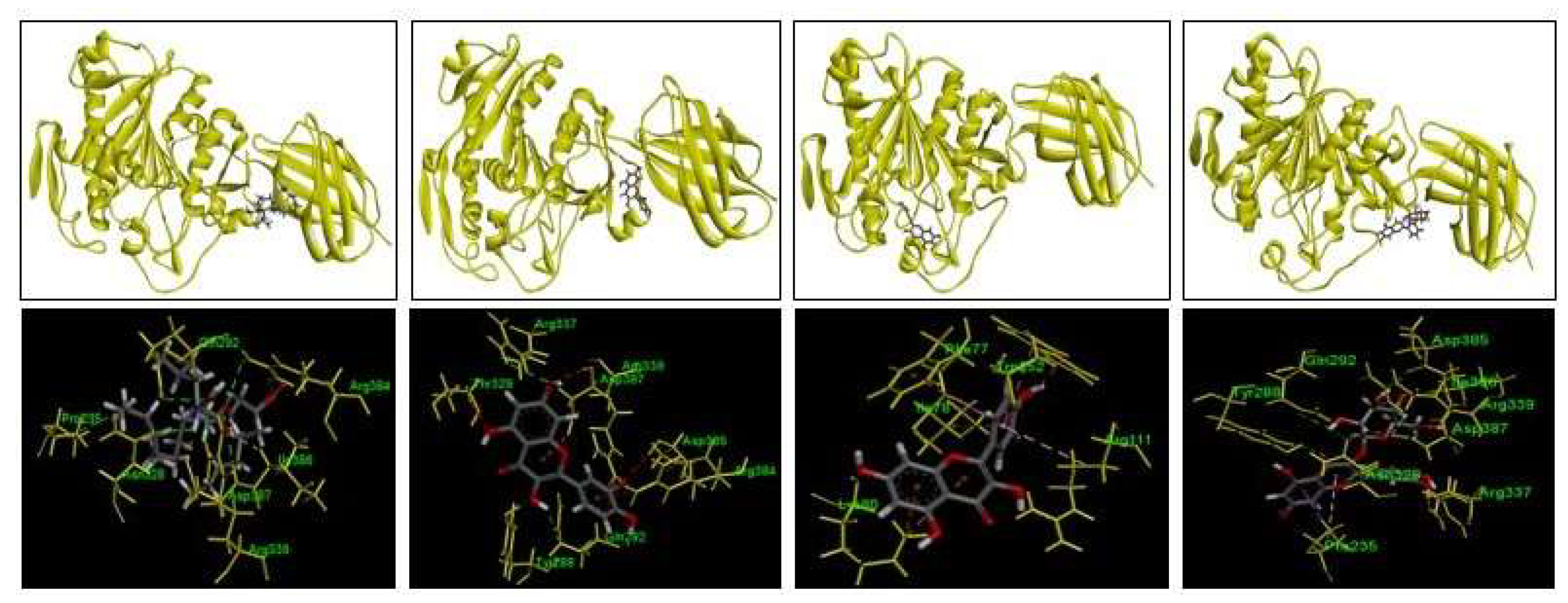

3.6. In-Silico Study of Ligand Effect of Polyphenols on Rat Lipase

Molecular docking is a sophisticated computational technique widely employed to unravel the intricate mechanisms through which phytochemicals from plant extracts interact with specific target proteins [

48,

54,

55,

56]. In the context of this study, the focus was on exploring how polyphenolic compounds found in plants could potentially inhibit pancreatic lipase, a key enzyme involved in lipid digestion. The compounds under investigation—quercetin, kaempferol, isoquercetin, and orlistat—were subjected to molecular docking studies alongside each other to discern their binding affinities and modes of interaction with pancreatic lipase.

Orlistat served as the benchmark in this analysis due to its established role as a pancreatic lipase inhibitor. The docking results revealed that orlistat binds to several critical residues of the rat lipase enzyme, including Pro235, Gln292, Asn328, Arg339, Arg384, Ile386, and Asp387. These interactions were primarily characterized by hydrogen bonds, with a calculated binding affinity of -5.1 kcal/mol. The bond distances observed ranged from 1.84697 to 2.71731 angstroms, indicating stable and specific binding between orlistat and the lipase enzyme. Moving to the polyphenolic compounds, quercetin exhibited a binding affinity of -7.4 kcal/mol with the lipase enzyme, forming hydrogen bonds and Pi-cation interactions with Tyr288, Gln292, Thr329, Arg337, Arg339, Arg384, Asp385, and Asp387. The distances between quercetin and these amino acid residues ranged from 1.03717 to 2.717 angstroms, suggesting strong and specific interactions. This pattern of binding indicates that quercetin, like orlistat, has the potential to inhibit pancreatic lipase through direct interactions at crucial binding sites on the enzyme. Similarly, isoquercetin demonstrated a high binding affinity of -7.8 kcal/mol, engaging in hydrogen bonds, Pi-sigma bonds, and Pi-alkyl interactions with Pro235, Tyr288, Gln292, Asp328, Arg337, Arg339, Asp385, Ile386, and Asp387. The bond distances observed ranged from 1.95931 to 3.09944 angstroms, indicating robust binding between isoquercetin and the lipase enzyme. This molecular interaction profile suggests that isoquercetin could also effectively inhibit pancreatic lipase activity by occupying and obstructing critical functional sites on the enzyme. Kaempferol, with a binding affinity of -7.6 kcal/mol, showed interactions with Phe77, Ile78, Lys80, Trp252, and Arg111 of the lipase enzyme. These interactions involved hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic Pi-Pi bonds, and electrostatic Pi-cation interactions. Despite its high binding affinity comparable to quercetin and isoquercetin, kaempferol exhibited a distinct binding site on the lipase enzyme, indicating potential differences in its inhibitory mechanism compared to the other polyphenolic compounds studied.

The findings from these molecular docking studies provide valuable insights into how polyphenolic compounds from plant extracts can potentially modulate pancreatic lipase activity. By understanding their specific binding modes and affinities, researchers can further explore the therapeutic implications of these natural compounds in managing lipid metabolism and related disorders. The ability of these compounds to inhibit pancreatic lipase activity underscores their potential as functional ingredients in dietary supplements or pharmaceutical formulations aimed at controlling lipid absorption and improving metabolic health. Future research could build upon these findings by conducting in vitro and in vivo studies to validate the inhibitory effects of these polyphenolic compounds on pancreatic lipase and explore their broader implications in clinical settings.

Figure 6.

In silico ligand effect of polyphenols on rat lipase.

Figure 6.

In silico ligand effect of polyphenols on rat lipase.

Table 1.

Binding site, bonds distance and binding affinity of the polyphenols and orlistat with rat lipase.

Table 1.

Binding site, bonds distance and binding affinity of the polyphenols and orlistat with rat lipase.

| |

Orlistat |

Quercetin |

Isoquercetin |

Kempferol |

| ASP387 |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=1.84697) |

Electrostatic bonding (Bond distance=2.92715) |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=1.95931) |

NA |

| ARG384 |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.10484) |

Electrostatic bonding (Bond distance=3.92217) |

NA |

NA |

| ASN328 |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.71731) |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.71731) |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.47433) |

NA |

| GLN292 |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.63724) |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=1.87559) |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.31568) |

NA |

| ARG339 |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.3489) |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=1.03717) |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.254) |

NA |

| ILE386 |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.50999) |

NA |

Hydrogen bonding (Bond distance=2.32557) |

NA |

| Binding Affinity (Kcal/mol) |

-5.1 |

-7.4 |

-7.8 |

-7.6 |

Conclusion

The current study investigated the ethanol extracts from seeds of S. cumini and roots of D. bulbifera, revealing high total phenolic content alongside potent free radical scavenging and pancreatic lipase inhibitory activities. Previous research has highlighted these extracts as rich sources of a complex array of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. Our findings establish a robust positive correlation between the presence of phenolic compounds and the observed antioxidant and anti-lipase activities. Specific bioactive polyphenols identified in these extracts include kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, isoquercetin (quercetin-3-glucoside), myricetin-3-L-arabinoside, quercetin-3-D-galactoside, dihydromyricetin, and eugenol-triterpenoid. These compounds are likely responsible for the potent antioxidant and anti-obesity properties demonstrated by S. cumini and D. bulbifera extracts. The results suggest that both S. cumini and D. bulbifera extracts hold promise in combating obesity through their inhibition of pancreatic lipase activity. This study lays a foundation for future clinical trials aimed at validating these effects and for developing standardized herbal medications. Such advancements could have significant implications in both the prevention and treatment of obesity-related disorders, leveraging natural compounds to tackle metabolic challenges effectively. Thus, these findings underscore the potential of S. cumini and D. bulbifera as therapeutic agents in the fight against obesity, offering a pathway towards the development of novel herbal treatments with clinical relevance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.C., M.B.U and J.A.C.; methodology, M.H.A., S.T., A.A.C.; software, M.H.A., S.T.; validation, M.S.A., J.A.C and M.B.U.; formal analysis, M.H.A. and S.T.; investigation, M.H.A., S.T. and A.A.C.; resources, A.A.C.; data curation, M.H.A., S.T. and A.A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.C., J.A.C. and M.B.U; writing—review and editing, M.S.A.; S.K. F.A.; visualization, A.A.C..; supervision, A.A.C. and M.B.U.; project administration, J.A.C., F.A., M.S.A.; funding acquisition, A.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a financial grant from the University Grants Commission (UGC) of Bangladesh (Grant No. 37.01.0000.073.07.002.20.33/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the by the Research and Ethics Committee of the State University of Bangladesh (ethical approval number 2021-06-01/5UB/A-ERC/004).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Ikhtiar Hossain Sohel, SK+F Pharmaceuticals Ltd. for providing Orlistat powder as a gift sample.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Centre WM (2015) Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization.

- De Pergola, G.; Silvestris, F. Obesity as a major risk factor for cancer. J. Obes. 2013, 291546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abete, I.; Astrup, A.; Martínez, J.A.; Thorsdottir, I.; Zulet, M.A. Obesity, and the metabolic syndrome: The role of different dietary macronutrient distribution patterns and specific nutritional components on weight loss and maintenance. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, M.J.; Yanovski, S.Z.; Wilson, G.T. Obesity: What mental health professionals need to know. Am J Psychiatry. 2000, 157, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.S.; Shah, G.B.; Singh, S.D.; Gohil, P.V.; Chauhan, K.; Shah, K.A.; Chorawala, M. Effect of piperine in the regulation of obesity-induced dyslipidemia in high-fat diet rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011, 43, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Jiao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liang, C.; Yan, K.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, X.; Han, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Zhang, L. Leaf extract from Vitis vinifera L. reduces high fat diet-induced obesity in mice. Food Funct., 2021, 12, 6452–6463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.; Kim, J.; Himmeldirk, K.; Cao, Y.; Chen, X. Antidiabetes and Anti-obesity Activity of Lagerstroemia speciosa. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007, 4, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preuss, H.G. Citrus aurantium as a thermogenic, weight-reduction replacement for ephedra: An overview. J Med. 2002, 33, 247–264. [Google Scholar]

- Balusamy, S.R.; Veerappan, K.; Ranjan, A.; Ju-Kim, Y.; Chellapan, D.K.; Dua, K.; Lee, J.; Perumalsamy, H. Phyllanthus emblica fruit extract attenuates lipid metabolism in 3T3-L1 adipocytes via activating apoptosis mediated cell death. Phytomedicine. 2020, 66, 153129–153137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attari, V.F.; Mahadavi, A.M.; Javadivala, Z.; Mahluji, S.; Vahed, Z.S.; Ostradahimi, A. A systematic review of the anti-obesity and weight lowering effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) and its mechanisms of action. Phytother Res. 2018, 32, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, L.; Yang, L.; Lu, H.; Wang, S.; Sung, G. Anti-obesity and Hypolipidemic effects of garlic oil and onion oil in rats fed a high-fat diet. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2018, 15, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, A.P.; Sousa-Filho, C.P.B.; Marinovic, M.P.; Rodrigues, A.C.; and Otton, R. Polyphenol-rich green tea Extract Induces Thermogenesis in Mice by a Mechanism Dependent on Adiponectin Signaling. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 78, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kishi, H.; and Kobayashi, S. Add-on Therapy with Traditional Chinese Medicine: An Efficacious Approach for Lipid Metabolism Disorders. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 134, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberdi, G.; Rodríguez, V.M.; Miranda, J.; Macarulla, M.T.; Arias, N.; Andrés-Lacueva, C. Changes in white Adipose Tissue Metabolism Induced by Resveratrol in Rats. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, R.-Y.; Lee, H.-I.; Ham, J.R.; Yee, S.-T.; Kang, K.-Y.; and Lee, M.-K. Heshouwu (Polygonum Multiflorum Thunb.) Ethanol Extract Suppresses Pre-adipocytes Differentiation in 3T3-L1 Cells and Adiposity in Obese Mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.-Y.; Choi, J.-H. Korean Curcuma Longa L. Induces Lipolysis and Regulates Leptin in Adipocyte Cells and Rats. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2016, 10, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Jeon, S.-M.; Lee, M.-K.; Jung, U.J.; Shin, S.-K.; and Choi, M.-S. Antilipogenic Effect of green tea Extract in C57BL/6J-Lepob/obmice. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.M.; Tawfek, N.S.; Abo-El Hussein, B.K.; El-Ghany, M.S.A. Anti-Obesity Potential of Orlistat and Amphetamine in Rats Fed on High Fat Diet. Sciences. 2015, 5, 453–461. [Google Scholar]

- Villa-Ruano, N.; Zurita-Vásquez, G.G.; Pacheco-Hernández, Y.; Betancourt-Jiménez, M.G.; Cruz-Durán, R.; Duque-Bautista, H. Anti-Iipase and antioxidant properties of 30 medicinal plants used in Oaxaca, México. Biol. Res. 2013, 46, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, E.D.; Walkey, C.J.; Puigserver, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.A.; Rahman, M.S.; Nishimura, K.; Jisaka, M.; Nagaya, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Shono, F.; Yokota, K. 15-Deoxy-Δ(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) interferes inducible synthesis of prostaglandins E(2) and F(2α) that suppress subsequent adipogenesis program in cultured preadipocytes. Prost. Other Lipid Mediat. 2011, 95, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, X.; Tang, Q.Q. Transcriptional regulation of adipocyte differentiation: A central role for CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) beta. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.D.; MacDougald, O.A. Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Rahman, M.S.; Nishimura, K.; Jisaka, M.; Nagaya, T.; Shono, F.; Yokota, K. Stable expression of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase in cultured preadipocytes impairs adipogenesis program independently of endogenous prostanoids. Exp. Cell Res. 2012, 318, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.N.; Xianga, J.Z.; Qi, Z.; Du, M. Plant extracts in prevention of obesity. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 62, 2221–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azhary, D.B.; Amin, H.M.; Kotb, E.M. Anti-obesity Effects of Some Plant Extracts in Rats Fed with High-Fat Diet 2022, 12, e120122190631. [CrossRef]

- Adomeniene, A.; Venskutonis, P.R. Dioscorea spp.: Comprehensive Review of Antioxidant Properties and Their Relation to Phytochemicals and Health Benefits. Molecules 2022, 27, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshwarappa, R.S.B.; Iyer, R.S.; Subbaramaiah, S.R.; Richard, S.A.; Dhananjaya, B.L. Antioxidant activity of Syzygium cumini leaf gall extracts. Bio Impacts, 2014, 4, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainasara, M.M.; Bakar, M.F.A.; Akim, A.M.; Linatoc, A.C.; Bakar, F.I.A.; Ranneh, Y.K.H. Secondary Metabolites, Antioxidant, and Antiproliferative Activities of Dioscorea bulbifera Leaf Collected from Endau Rompin, Johor, Malaysia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021, 8826986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbiantcha, M.; Kamanyi, A.; Teponno, R.B.; Tapondjou, A.L.; Watcho, P.; Nguelefack, T.B. Analgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Extracts from the Bulbils of Dioscorea bulbifera L. var sativa (Dioscoreaceae) in Mice and Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011, e912935. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Ali, S.I.; El-Baz, F.K. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Crude Extracts and Essential Oils of Syzygium cumini Leaves. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8, e60269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajpai, M.; Pande, A.; Tewari, S.K.; Prakash, D. Phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of some food and medicinal plants. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2005, 56, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan M, Mahmoud MM, Tabrez S; et al. Exploring flavonoids for potential inhibitors of a cancer signaling protein PI3Kγ kinase using computational methods. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 4547–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensi M, Ortega A, Mena S; et al. Natural polyphenols in cancer therapy. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2011, 48, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatafora, C.; Tringali, C. Natural-derived polyphenols as potential anticancer agents. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2012, 12, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrios Stagos Antioxidant Activity of Polyphenolic Plant Extracts. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 19. [CrossRef]

- Meydani, M.; Hasan, S.T. Dietary Polyphenols and Obesity. Nutrients 2010, 2, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, M.; Akhtar, S.; Ismail, T.; Wahid, M.; Abbas, M.W.; Mubarak, M.S.; Yuan, Y.; Barnard, R.T.; Ziora, Z.M.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Phytochemical Profile, Biological Properties, and Food Applications of the Medicinal Plant Syzygium cumini. Foods 2022, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; Tariq, M.; Hussain, M.; Andleeb, A.; Masoud, M.S.; Ali IMraiche, F.; Hasan, A. Phenolic contents-based assessment of therapeutic potential of Syzygium cumini leaves extract. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0221318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Tsim, K.W.; Chou, G.X.; Wang, J.M.; Ji, L.L.; et al. Phenolic compounds from the rhizomes of Dioscorea bulbifera. Chem Biodivers 2011, 8, 2110–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, M.; Hamed, Y.S.; Akhtar, H.M.S.; Chen, D.; Mukhtar, S.; Wan, P.; Riaz, A.; Zeng, X. Extraction optimisation, antioxidant activity and inhibition on α-amylase and pancreatic lipase of polyphenols from the seedsof Syzygium cumini Int. J. Food Sci. 2019, 54, 2084–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulla1A; Alam1MA; Sikder, B.; Sum, F.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Zaki Farhad Habib, Z.F.; Mohammed, M.K.; Subhan, N.; Hossain, H.; Reza, H.M. Supplementation of Syzygium cumini seed powder prevented obesity, glucose intolerance, hyperlipidemia and oxidative stress in high carbohydrate high fat diet induced obese rats. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2017, 17, 289. [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Nat Protoc. 2007, 2, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliyan, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, R.P.; Chang, C.M. Determination of Antioxidants by DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity and Quantitative Phytochemical Analysis of Ficus religiosa. Molecules 2022, 27, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arika, W.M.; Kibiti, C.M.; Njagi, J.M.; Ngugi, M.P. Anti-obesity effects of dichloromethane leaf extract of Gnidia glauca in high fat diet-induced obese rats. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02800. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaradat, N.; Zaid, A.N.; Hussein, F.; Zaqzouq, M.; Aljammal, H.; Ayesh, O. Anti-Lipase Potential of the Organic and Aqueous Extracts of Ten Traditional Edible and Medicinal Plants in Palestine; a Comparison Study with Orlistat. Medicines 2017, 4, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Duan, Y.; Gao, J.; Ruan, Z. Screening for Anti-lipase Properties of 37 Traditional Chinese Medicinal Herbs. J Chin Med 2010, 73, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chigurupati, S.; Alharbi, F.S.; Almahmoud, S.; Aldubayan, M.; Almoshari, Y.; Vijayabalan, S.; Bhatia, S.; Chinnam, S.; Venugopal, V. Molecular docking of phenolic compounds and screening of antioxidant and antidiabetic potential of Olea europaea L. Ethanolic leaves extract. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J. Fruits of warm climates. Miami: Julia Morton Winterville North Carolina; p. 1987.

- Reynertson, K.A.; Yang, H.; Jiang, B.; Basile, M.J.; Kennelly, E.J. Quantitative analysis of antiradical phenolic constituents from fourteen edible Myrtaceae fruits. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustanji, Y.; Issa, A.; Mohammad, M.; Hudaib, M.; Tawah, K.; Alkhatib, H.; Almasri, I.; Al-Khalidi, B. Inhibition of hormone-sensitive lipase and pancreatic lipase by Rosmarinus officinalis extract and selected phenolic constituents. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 2235–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.D.; Duan, Y.Q.; Gao, J.M.; Ruan, Z.G. Screening for anti-lipase properties of 37 traditional Chinese medicinal herbs. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010, 73, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996, 20, 933–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahsin, M.R.; Sultana, A.; Khan, M.S.M.; Jahan, I.; Mim, S.R.; Tithi, T.I.; Ananta, M.F.; Afrin, S.; Ali, M.; Hussain, S.; Chowdhury, J.A.; Kabir, S.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Amran, M.S.; Aktar, F. An evaluation of pharmacological healing potentialities of Terminalia Arjuna against several ailments on experimental rat models with an in-silico approach. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescano, C.H.; Freitas de Lima, F.; Mendes-Silvério, C.B.; Justo, A.F.O.; da Silva Baldivia, D.; Vieira, C.P.; Sanjinez-Argandoña, E.J.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Mónica, F.Z.; Pires de Oliveira, I. Effect of Polyphenols From Campomanesia adamantium on Platelet Aggregation and Inhibition of Cyclooxygenases: Molecular Docking and in Vitro Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Tao, Y.; Qu, H.; Wang, C.; Yan, F.; Gao, X.; Zhang, M. Exploration of plant-derived natural polyphenols toward COVID-19 main protease inhibitors: DFT, molecular docking approach, and molecular dynamics simulations. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 5357–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).