Submitted:

20 May 2024

Posted:

21 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Plant Collection and Preparation

2.1.2. Experimental Animals

2.1.3. Preparation of the Neocarya macrophylla (Nm) Fractions

2.1.4. Preparation of High Fat Diet

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Induction of High Fat Diet/Streptozotocin (HFD/STZ) Diabetes

2.3. Determination of Minimum Effective Dose

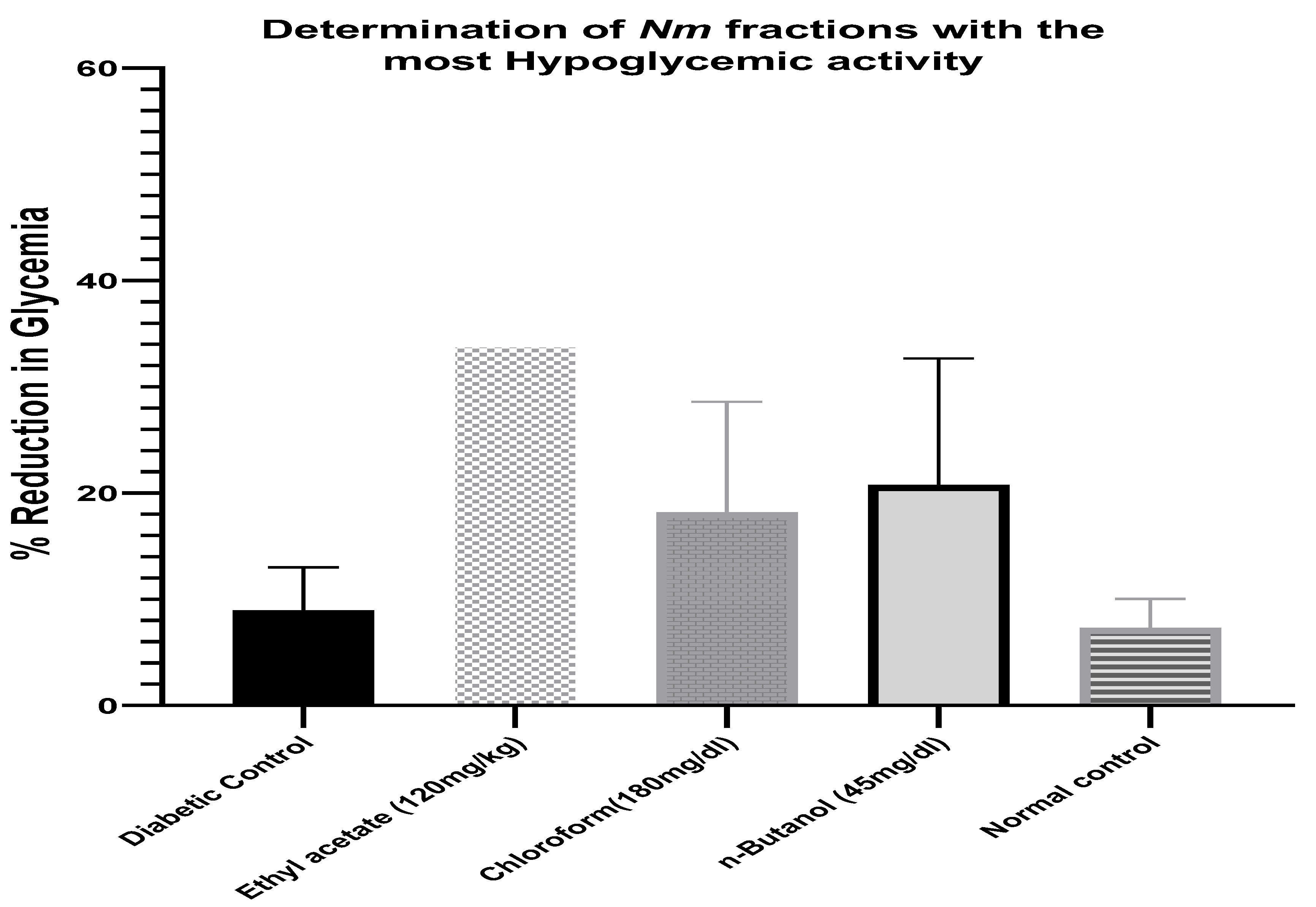

2.4. Determination of Neocarya macrophylla Fraction with Most Hypoglycemic Activity

2.5. Experimental Design

2.6. Determination of Fasting Blood Glucose

2.7. Body Mass Index Measurement (BMI)

2.8. Basic Biochemical Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Determination of Minimum Effective Dose and the Most Active Fraction from Neocarya macrophylla (Nm) Leaves

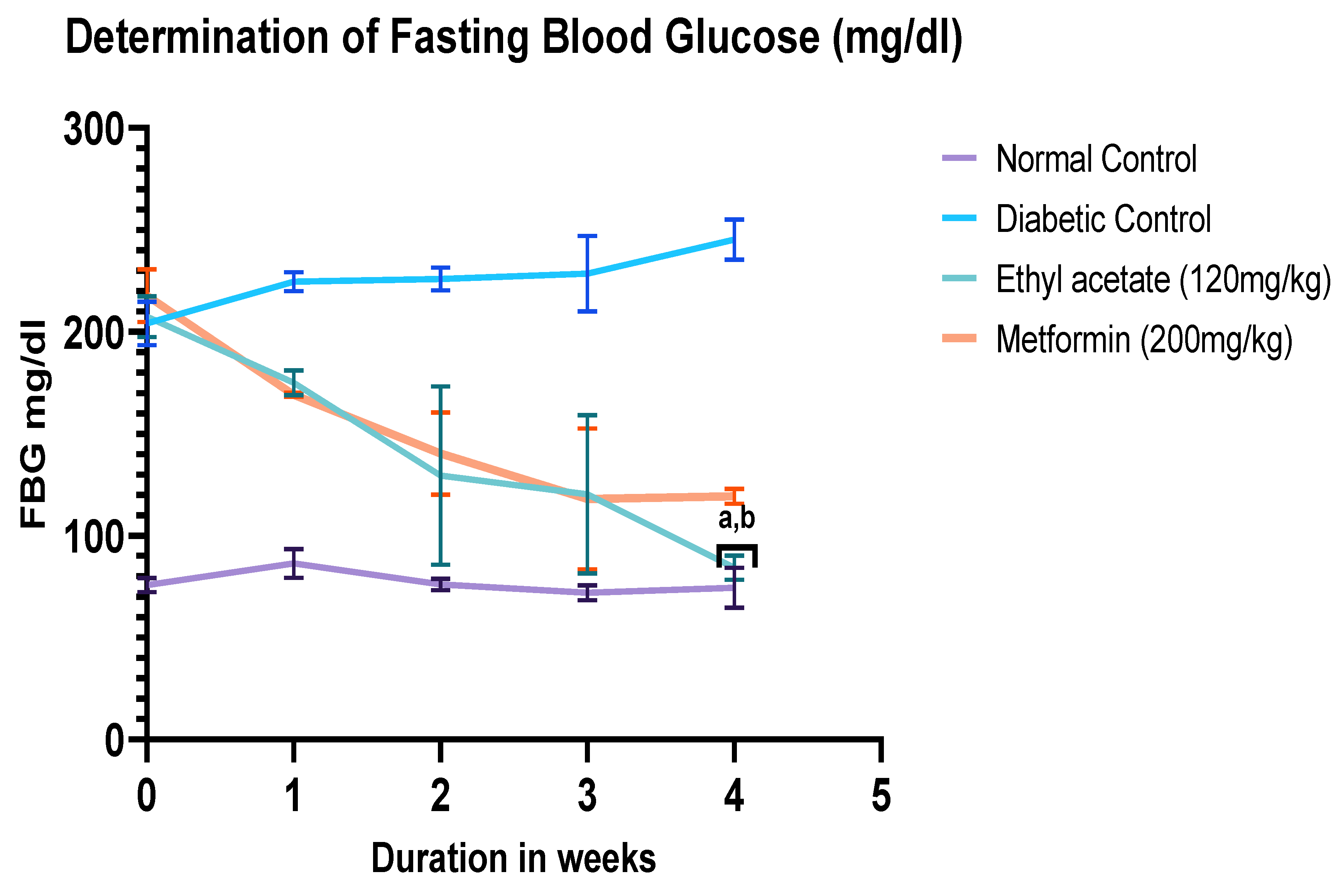

3.2. Determination of Fasting Blood Glucose Level after 4 Weeks of Treatment

3.3. Effect of Ethyl Acetate fraction of Neocarya macrophylla (120 mg/kg) on Body Mass Index (g/cm2)

3.4. Effect of Ethyl Acetate Leaf Fraction of Nm Fraction on Complete Blood Count

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Conflict of Interest:

References

- June CC, Wen LH, Sani HA, Latip J, Gansau JA, Chin LP, et al. Hypoglycemic effects of Gynura procumbens fractions on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats involved phosphorylation of GSK3β (Ser-9) in liver. Sains Malays. 2012;41(8):969–75.

- Banday MZ, Sameer AS, Nissar S. Pathophysiology of diabetes: An overview. Avicenna J Med [Internet]. 2020 Oct 4;10(04):174–88. Available from: http://www.thieme-connect.de/DOI/DOI?10.4103/ajm.ajm_53_20.

- Nain P, Saini V, Sharma S, Nain J. Antidiabetic and antioxidant potential of Emblica officinalis Gaertn. leaves extract in streptozotocin-induced type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012 Jun;142(1):65–71.

- IDF. International Diabetes Federation. Vol. 102, Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2022.

- Mercer T, Chang AC, Fischer L, Gardner A, Kerubo I, Tran DN, et al. Mitigating the Burden of Diabetes in Sub-Saharan Africa through an Integrated Diagonal Health Systems Approach. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019 Oct;Volume 12:2261–72.

- Pastakia S, Pekny C, Manyara S, Fischer L. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa – from policy to practice to progress: targeting the existing gaps for future diabetes care. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017 Jun;Volume 10:247–63.

- Abu-Odeh AM, Talib WH. Middle East Medicinal Plants in the Treatment of Diabetes: A Review. Molecules [Internet]. 2021 Jan 31;26(3):742. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/26/3/742.

- Babiker A, Dubayee M. Anti-diabetic medications: How to make a choice? Sudan J Paediatr [Internet]. 2017;11–20. Available from: https://www.ejmanager.com/fulltextpdf.php?mno=287497.

- Cefalu WT, Stephens JM, Ribnicky DM. Diabetes and Herbal (Botanical) Medicine [Internet]. 2011. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92755/?report=printable.

- Aloke C, Egwu CO, Adelusi OA, Chinaka N, Kanu SC, Ogbodo PN, et al. Medicinal plants: A promising source of anti-diabetic agents in sub-Sahara Africa. Current Issues in Pharmacy and Medical Sciences. 2023 Jun 1;36(2):65–76.

- Salehi, Ata, V. Anil Kumar, Sharopov, Ramírez-Alarcón, Ruiz-Ortega, et al. Antidiabetic Potential of Medicinal Plants and Their Active Components. Biomolecules. 2019 Sep 30;9(10):551.

- Mohammed, A. Hypoglycemic Potential of African Medicinal Plants in Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Human Subjects: A Review. Clinical Complementary Medicine and Pharmacology. 2023 Jun;3(2):100081.

- Aloke C, Egwu CO, Adelusi OA, Chinaka N, Kanu SC, Ogbodo PN, et al. Medicinal plants: A promising source of anti-diabetic agents in sub-Sahara Africa. Current Issues in Pharmacy and Medical Sciences. 2023 Jun 1;36(2):65–76.

- Aloke C, Egwu CO, Adelusi OA, Chinaka N, Kanu SC, Ogbodo PN, et al. Medicinal plants: A promising source of anti-diabetic agents in sub-Sahara Africa. Current Issues in Pharmacy and Medical Sciences. 2023 Jun 1;36(2):65–76.

- Haruna A, A M, M A, Z I, M H, Odiba O, et al. Phytochemical and antimicrobial evaluations of the methanol stem bark extract of Neocarya macropylla. J Chem Pharm Res. 2015;7(1):477–48.

- Halilu M, JO A, NL A, M A. Phytochemical screening and mineral element analysis of the root bark of Parinari macrophylla Sabine (Chrysobalanaceae) and its effect on microorganisms. Cont J Biol Sci. 2010; 3:46–50.

- Shehadeh MB, Suaifan GARY, Abu-Odeh AM. Plants Secondary Metabolites as Blood Glucose-Lowering Molecules. Molecules. 2021 Jul 17;26(14):4333.

- Rahman MdA, Chowdhury JMKH, Aklima J, Azadi MA. Leea macrophylla Roxb. leaf extract potentially helps normalize islets of β-cells damaged in STZ-induced albino rats. Food Sci Nutr. 2018 Jun 30;6(4):943–52.

- Muhammad S, Umar KJ, Sani NA, Muhammad S. Evaluation of nutritional and anti-nutritional profiles of gingerbread plum (Neocarya Macrophylla) seed kernel from Sokoto State, Nigeria. International Journal of Science and Technology. 2015; 4:361-367.

- Audu OT, Oyewale AO, Amupitan JO. The biological activities of secondary metabolites of Parinari macrophylla Sabine. ChemClass Journal. 2005;19–21.

- Jega Yusuf A, Ismail Abdullahi M, Alhaji Muhammad A, Ghandi Ibrahim K. Neocarya macrophylla (Sabine) Prance: Review on taxonomy, ethnobotany, phytochemistry and biological activities. 2021; Available from: www.preprints.

- Gheibi S, Kashfi K, Ghasemi A. A practical guide for induction of type-2 diabetes in the rat: Incorporating a high-fat diet and streptozotocin. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2017 Nov; 95:605–13.

- Mebratie W, Tekuar S, Alemayehu K, Dessie T. Body weight and linear body measurements of indigenous goat population in Awi Zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Acta Agric Scanda Anim Sci. 2022 Oct 2;71(1–4):89–97.

- Okoduwa S, Umar I, James D, Inuwa H. Anti-Diabetic Potential of Ocimum gratissimum Leaf Fractions in Fortified Diet-Fed Streptozotocin Treated Rat Model of Type-2 Diabetes. Medicines. 2017 Oct 11;4(4):73.

- Oguanobi NI, Ghasi S, Chijioke CP. Anti-diabetic effect of crude leaf extracts of Ocimum gratissimum in neonatal streptozotocin-induced type-2 model diabetic rats. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012; 4:77–88.

- Ramdath DD, Renwick S, Hawke A, Ramdath DG, Wolever TMS. Minimal Effective Dose of Beans Required to Elicit a Significantly Lower Glycemic Response Than Commonly Consumed Starchy Foods: Predictions Based on In Vitro Digestion and Carbohydrate Analysis. Nutrients. 2023 Oct 24;15(21):4495.

- Sanni O, Nkomozepi P, Islam MdS. Ethyl Acetate Fractions of Tectona Grandis Crude Extract Modulate Glucose Absorption and Uptake as Well as Antihyperglycemic Potential in Fructose–Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Dec 19;25(1):28.

- Nevoret C, Gervaise N, Delemer B, Bekka S, Detournay B, Benkhelil A, et al. The Effectiveness of an App (Insulia) in Recommending Basal Insulin Doses for French Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Longitudinal Observational Study. JMIR Diabetes. 2023 Mar 1;8: e44277.

- Martinez M, Santamarina J, Pavesi A, Musso C, Umpierrez GE. Glycemic variability and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021 Mar 24;9(1): e002032.

- Marcela Aragon Novoa D, Regina Mena Barreto Silva F. The Role of Natural Products on Diabetes Mellitus Treatment.

- Ríos J, Francini F, Schinella G. Natural Products for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Planta Med. 2015 Jul 1;81(12/13):975–94.

- Nguyen PTM, Ngo Q Van, Nguyen MTH, Quach LT, Pyne SG. Hypoglycemic activity of the ethyl acetate extract from Smilax glabra Roxb in mice: Biochemical and histopathological studies. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2020 Dec;23(12):1558–64.

- Nevoret C, Gervaise N, Delemer B, Bekka S, Detournay B, Benkhelil A, et al. The Effectiveness of an App (Insulia) in Recommending Basal Insulin Doses for French Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Longitudinal Observational Study. JMIR Diabetes. 2023 Mar 1;8: e44277.

- Ibrahim AA, Abdussalami MS, Appah J, Umar AH, Ibrahim AA, Dauda KD. Antidiabetic effect of aqueous stem bark extract of Parinari macrophylla in alloxan-induced diabetic Wistar rats. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2021;7(1).

- Muhammad S, Umar KJ, Sani NA, Sokoto MA. Analysis of Nutrients, Total Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity of Gingerbread Plum (Neocarya Macrophylla ) Fruits from Sokoto. 2015;29(1):20–5.

- Almustapha N, Achor M, ME H, Abah JO. Phytochemical screening and mineral element analysis of the root bark of Parinari macrophylla Sabine (Chrysobalanaceae) and its effect on microorganisms. Cont J Biol Sci. 2010; 3:46–50.

- Melissa Rohman. https://news.feinberg.northwestern.edu/2023/11/08/study-finds-antidiabetic-drug-effective-for-weight-loss/. 2023. Study Finds Antidiabetic Drug Effective for Weight-Loss.

- Elebiyo TC, Oluba OM, Adeyemi OS. Anti-malarial and haematological evaluation of the ethanolic, ethyl acetate and aqueous fractions of Chromolaena odorata. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023 Dec 1;23(1).

- Ujah FO, Y. Mohammad Y, E. Audu-War V. Effect of Ethyl Acetate Fraction of P. amarus Leaf on Hematological and Biochemical Parameters in Albino Rat with Arsenic Induced Toxicity. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Development. 2021 Jun 15;9(3):11–5.

- Ofem O, Ani E, Eno A. Effect of aqueous leaves extract of Ocimum gratissimum on hematological parameters in rats. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2012;2(1):38.

- Sunmonu TO, Afolayan AJ. Evaluation of Antidiabetic Activity and Associated Toxicity of Artemisia afra Aqueous Extract in Wistar Rats. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013; 2013:1–8.

- Otunola GA, Afolayan AJ. Antidiabetic effect of combined spices of Allium sativum, Zingiber officinale and Capsicum frutescens in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Front Life Sci. 2015 Oct 2;8(4):314–23.

- Taiwo IA, Oboh BolaO, Francis-Garuba PenielN. Haematological Properties of Aqueous Extracts of Phyllantus amarus (Schum and Thonn.) and Xylopia aethiopica (Dunal) A. Rich in Albino Rats. Studies on Ethno-Medicine. 2009 Jul 2;3(2):99–103.

- Fazelipour S, Hadipour Jahromy M, Tootian Z, Goodarzi N. Antidiabetic effects of the ethanolic extract of Allium saralicum R.M. Fritsch on streptozotocin-induced diabetes in a mice model. Food Sci Nutr. 2021 Sep 18;9(9):4815–26.

| Fractions of Nm (mg/kg) |

Blood Glucose Level (mg/dL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 hour | 1 hour | 2 hours | 4 hours | |

| Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM (%) | Mean±SEM (%) | Mean±SEM (%) | |

| HXG60 | 236 | 2323.3 (1.7) | 235 (0.4) | 225(4.7) |

| HXG120 | 248 | 245(1.2) | 240(3.2) | 230(7.3) |

| HXG180 | 250 | 240(4.0) | 236(5.6) | 230(8.0) |

| CLG60 | 254±4.8 | 249±6.6(2.1) | 243±6.2(4.5) | 239±5.3(5.9) |

| CLG120 | 249±3.6 | 243±3.6(2.4) | 237±4.3(4.8) | 231±4.6(7.2) |

| CLG180 | 225±8.6 | 208±10.4(7.7) | 193±20.4(23.2) | 166± 12.2(34.7) |

| ETG60 | 249 | 237 (4.8) | 239 | |

| ETG120 | 234 | 199 | 180 | 166 |

| ETG180 | 270 | 249 | 194 | 159 |

| BTG15 | 250 | 241(3.6) | 239(4.2) | 236(5.1) |

| BTG30 | 235 | 228(3.8) | 225(4.2) | 216(8.5) |

| BTG45 | 242 | 238(5.0) | 2061.3(14.1) | 180(25.0) |

| DC | 247 | 242 | 239 | 236 |

| Body Mass Index (g/cm2) | Normal control | Diabetic control |

Ethyl acetate (120 mg/kg) |

Metformin (200 mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration(weeks) | Mean ±SEM | Mean ±SEM | Mean ±SEM | Mean ±SEM |

| Week 0 | 24.89±0.53 | 61.21±1.45 | 61.71±2.06 | 57.01±2.04 |

| Week 1 | 28.39±0.64 | 62.59±1.61 | 59.62±2.66 | 57.64±1.59 |

| Week 2 | 27.06±0.77 | 63.83±1.72 | 59.14±2.38 | 60.29±2.77 |

| Week 3 | 28.51±0.48 | 65.43±1.82 | 56.46±2.81 | 57.94±1.56 |

| Week 4 | 29.01±0.81 | 67.28±1.86 | 55.56±1.89a | 61.82±2.24 |

| Variables | Normal Control | Diabetic Control |

Metformin (200 mg/kg) |

Ethyl acetate (120 mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEM | SEM | SEM | SEM | |

| RBC (1012/L) | 5.41 ± 0.2 | 2.95 ± 0.1 | 4.62 ± 0.1 | 3.32 ± 1.4 a**,b***,c** |

| Hb (g/dl) | 9.85 ± 0.2 | 5.62 ± 0.6 | 8.71 ± 0.5 | 8.32± 1.5a**,b*** |

| PCV (%) | 31.35 ± 1.4 | 17.24 ± 1.4 | 24.23 ± 0.5 | 20.72 ± 0.6 a,***b** |

| MCV (fL) | 53.50 ± 0.7 | 52.51 ± 0.7 | 51.16 ± 1.4 | 51.23 ± 1.4 |

| MCH (pg) | 20.24 ± 1.4 | 18.25 ± 0.2 | 19.26 ± 0.9 | 18.21 ± 0.3 |

| MCHC(g/L) | 32.52 ± 0.7 | 34.15 ± 0.2 | 34.51 ± 0.7 | 33.52 ± 0.6 |

| WBC (109/L) | 6.12 ± 0.2 | 9.24 ± 0.1 | 7.81 ± 0.9 | 5.22 ± 0.1 b**,c* |

| Neutrophil (%) | 4.72 ± 0.4 | 10.61 ± 2.7 | 7.53 ± 1.5 | 9.82 ± 2.2 a***,b*** |

| Monocyte (%) | 2.15 ± 0.4 | 5.51 ± 3.4 | 3.52 ± 1.9 | 3.32 ± 1.9 b* |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 55.23 ± 1.3 | 75.15 ± 2.6 | 66.15 ± 0.7 | 66.24 ± 0.8 a***,b*** |

| Eosinophil (%) | - | - | 1.52 ± 1.6 | 1.14 ± 0.3 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 39.21 ± 2.1 | 41.24 ± 0.3 | 36.52 ± 0.7 | 34.75±0.4 a**,b*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).