Submitted:

14 August 2024

Posted:

14 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

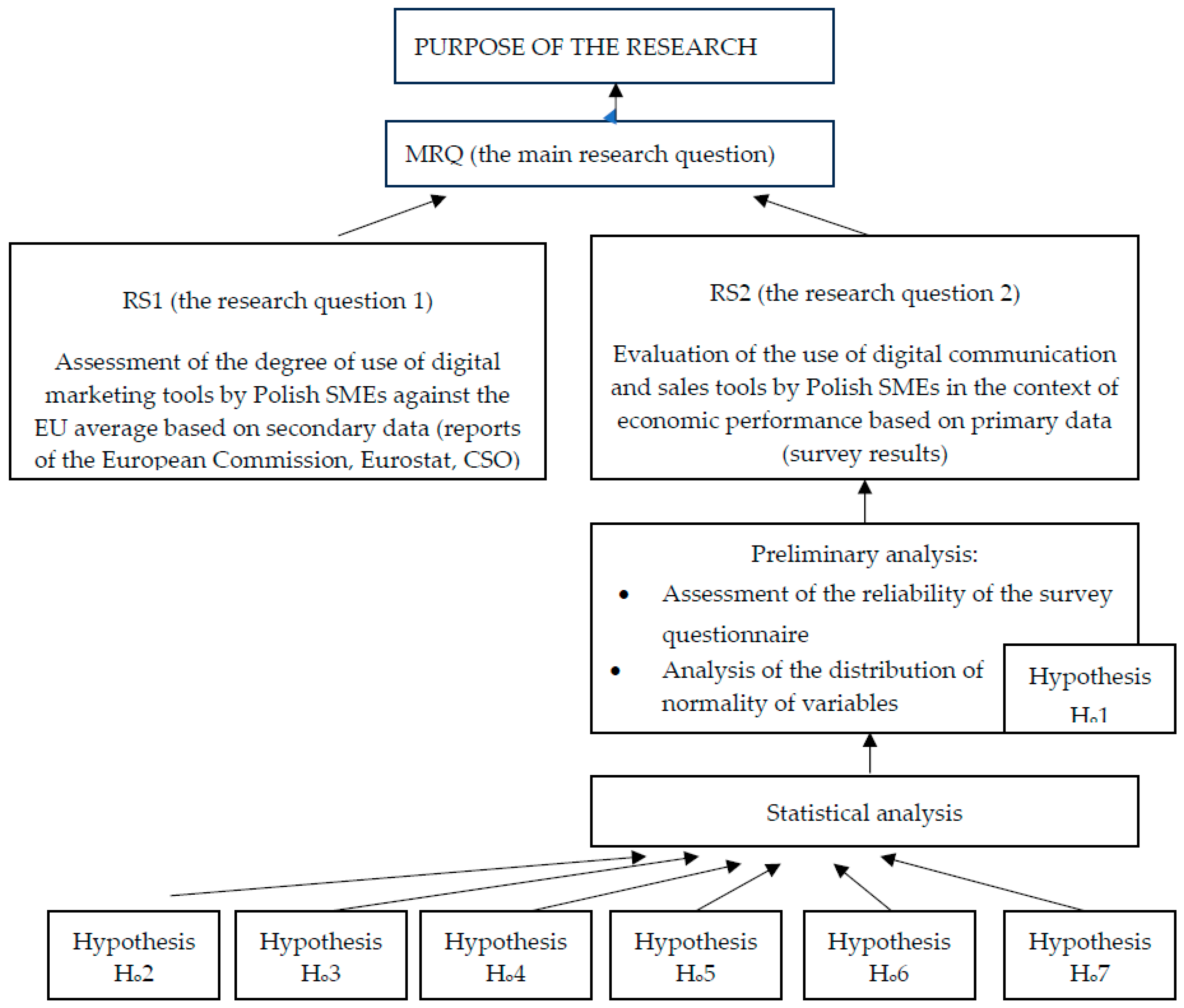

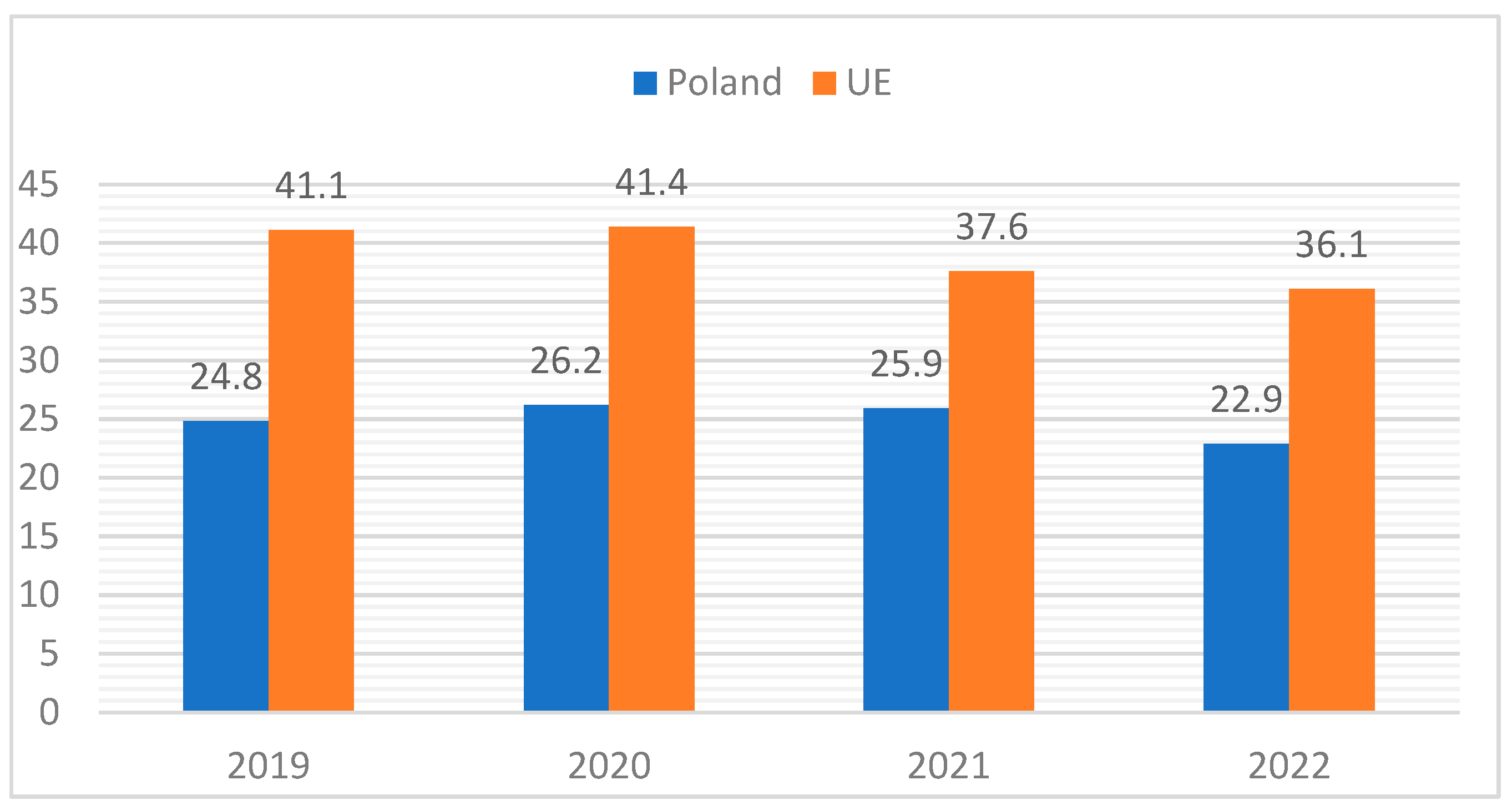

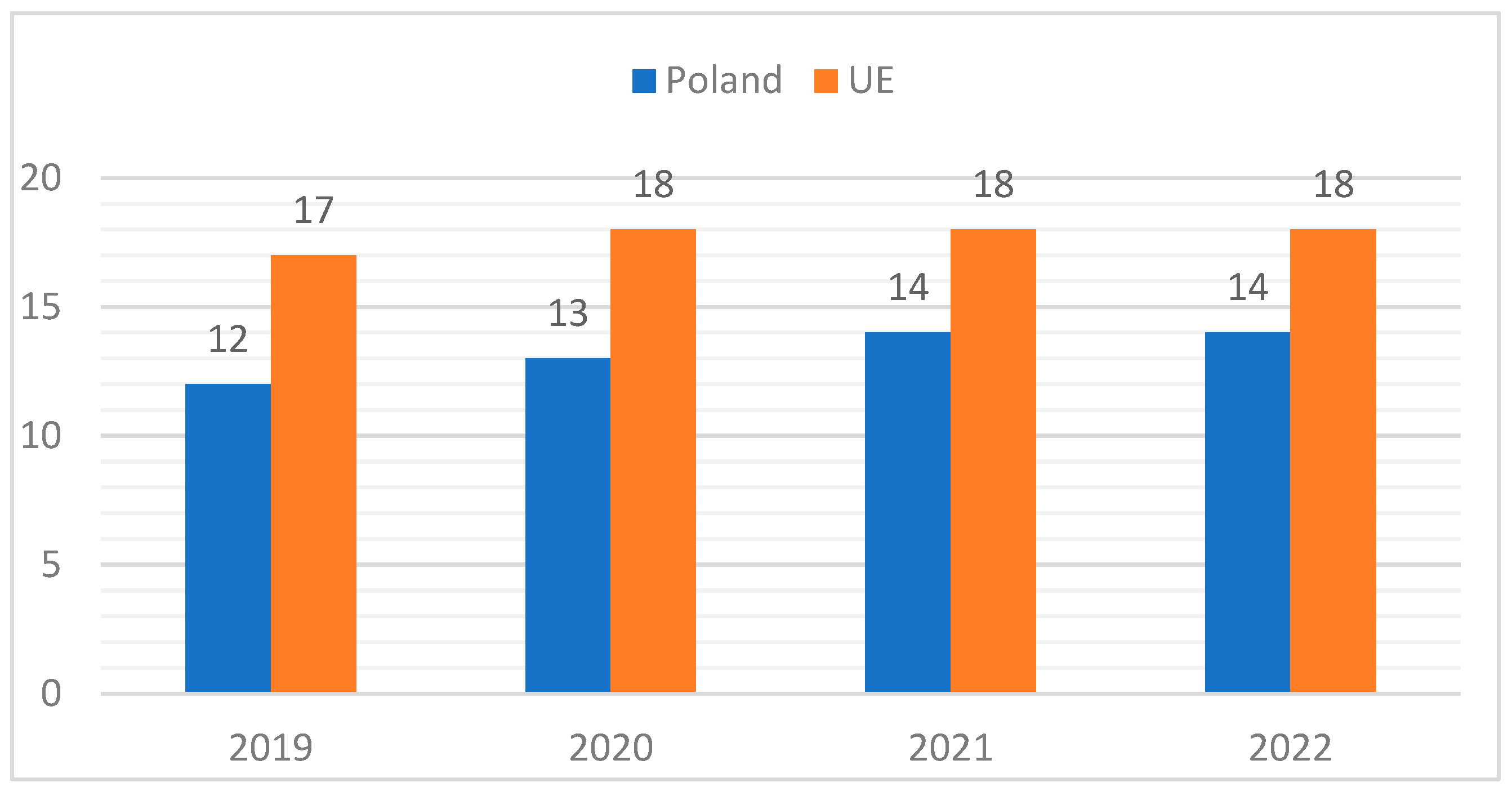

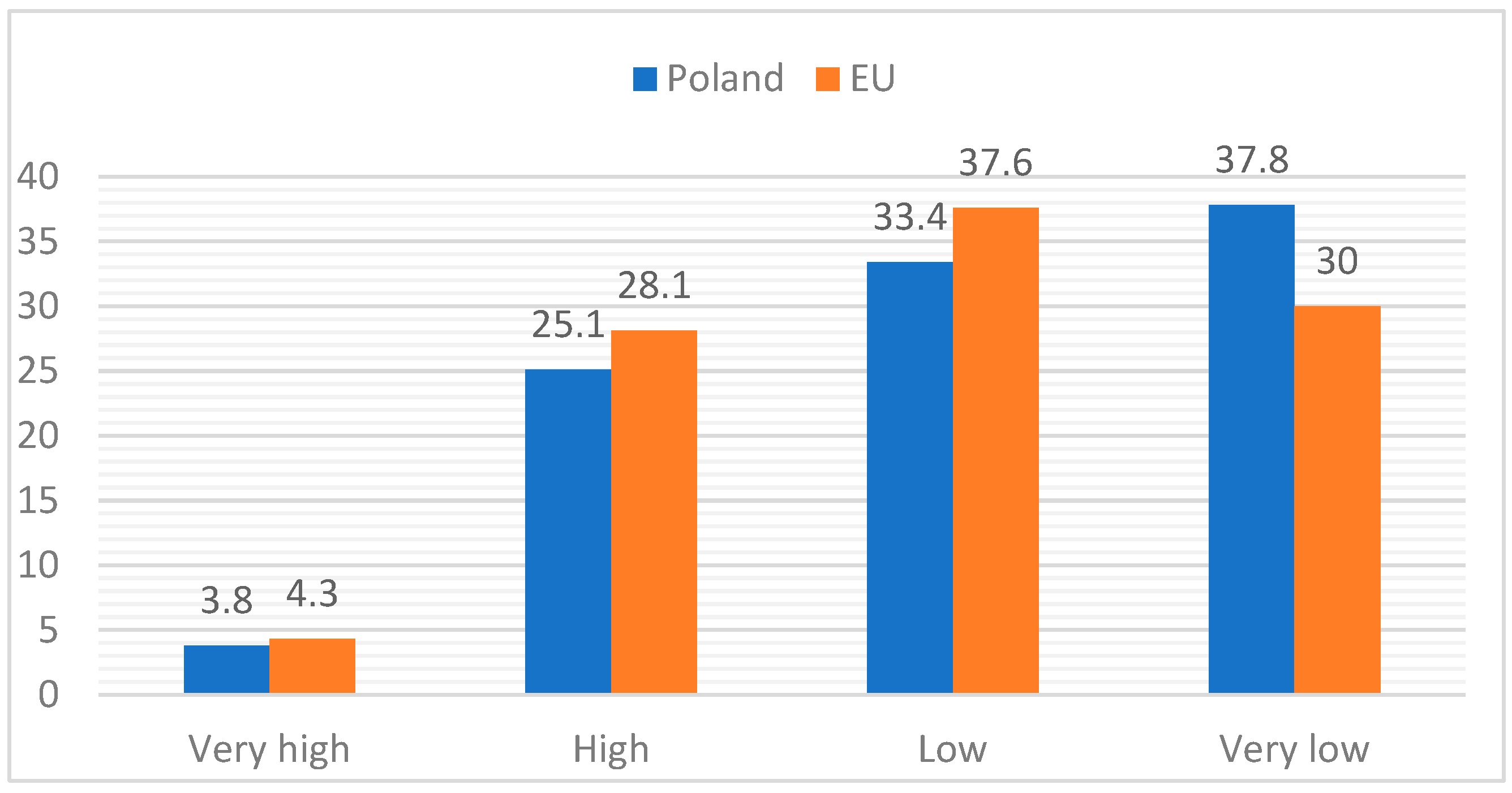

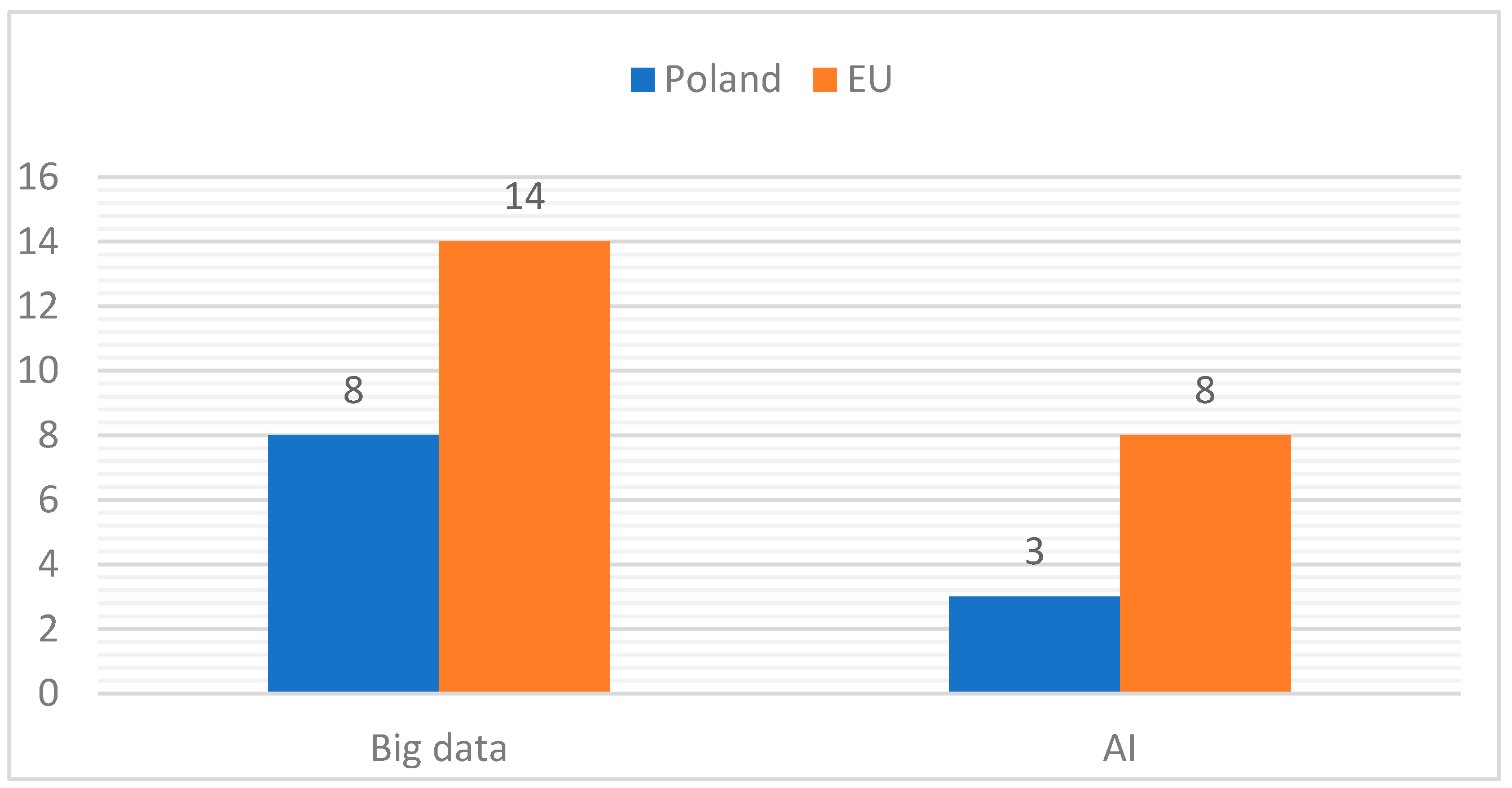

- First step – to assess the degree of use of digital marketing tools by Polish SMEs against the EU average based on secondary data (reports of the European Commission, Eurostat, Statistics Poland),

- Second step - to evaluate the application of the digital communication and sale tools by Polish SMEs in the context of economic results based on primary data (survey results) and statistical methods.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Development of New Technology in Marketing and Customer Service

RS 1: Is the use of the digital communication and sale tools by Polish SMEs at the same level as in the EU?

2.2. Measurable Benefits of Modern Tool Implementation

RS 2: What impact have the use of traditional and digital marketing communication and sale tools of Polish SMEs on economic performance?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Basis and Justification for the Choice of Research Methodology

- -

- Cronbach's alpha test- a test used to assess the reliability of surveys, and required for survey design,

- -

- Kolmogorov-Smirnov test- the test used to assess the normality distri-bution of the variables and required to determine the selection of further statistical tools,

- -

- Mann-Whitney U test- the test is suitable to test differences of 2 groups for ordi-nal dependent variable (Likert scale),

- -

- ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis tests and Dunn's post-hoc tests - test is suitable for the number of samples exceeding 2, for ordinal dependent variable (Likert scale),

- -

- Kendall's rank correlation coefficient- a coefficient used in socioeconomic research to examine the relationship between variables that are rated in a Likert scale survey,

- -

- MARSplines (Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines)-a non-parametric statistical regression me-method used to establish model predictors.

3.2. Sample

3.3. Procedure

- H0 2 Companies use traditional and modern customer communication methods to the same extent

- H0 3 Companies use traditional and modern sale methods to the same extent

- H0 4 Obstacles on the part of the company and of the customers limit modern technology implementation to the same extent

- H0 5 Companies use traditional and modern customer service tools to the same extent

- H0 6 Using particular communication and sale methods and obstacles to their implementation do not influence the economic results of the company

- H0 7 The implementation of modern technologies in the area of sale and customer service affects the individual economic effects to the same extent

3.4. Research Tools

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Data Analysis

4.2. Summary of Survey Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Polish SMEs make lower use of modern digital tools for communication and sales compared to companies in the EU,

- the studied companies use modern communication and sale tools to a low extent as they mostly employ traditional channels and methods;

- the obstacles to implementing modern communication and sale methods referring to the limitations on the company’s part decrease economic results. These are: the absence of sufficient funds, insufficient expertise and employees’ competence;

- the studied companies perceive the positive effect of the modern solutions on the financial results but see also that this entails future investment expenditure.

Theoretical Implications:

- deepening the concept of Schultz Integrated Marketing Communications - IMC [108],

- basis for international comparisons in the use of digital marketing tools by SMEs in different economies,

- basis for cross-industry comparisons.

Practical Implications

- organization of training and providing advice to micro-, small and medium-sized enterprise managers relating to the adaptation of human resources and innovation processes to the digital era challenges;

- development of intensive courses developing digital skills of SME employees relating to artificial intelligence, cybersecurity and blockchain;

- financial support for SMEs in their efforts to increase the advanced technology use, e.g. for buying license and software enabling to implement digital solutions;

- informing SMEs and encouraging them to create start-up ecosystems, increase the number of digital innovation hubs (DIH) in connection with the Startup Europe initiative and the European Network;

- activities oriented toward the development and improvement of the Enterprise Europe Network offering services adapted to SME’s needs.

Research Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question no. |

Question |

|---|---|

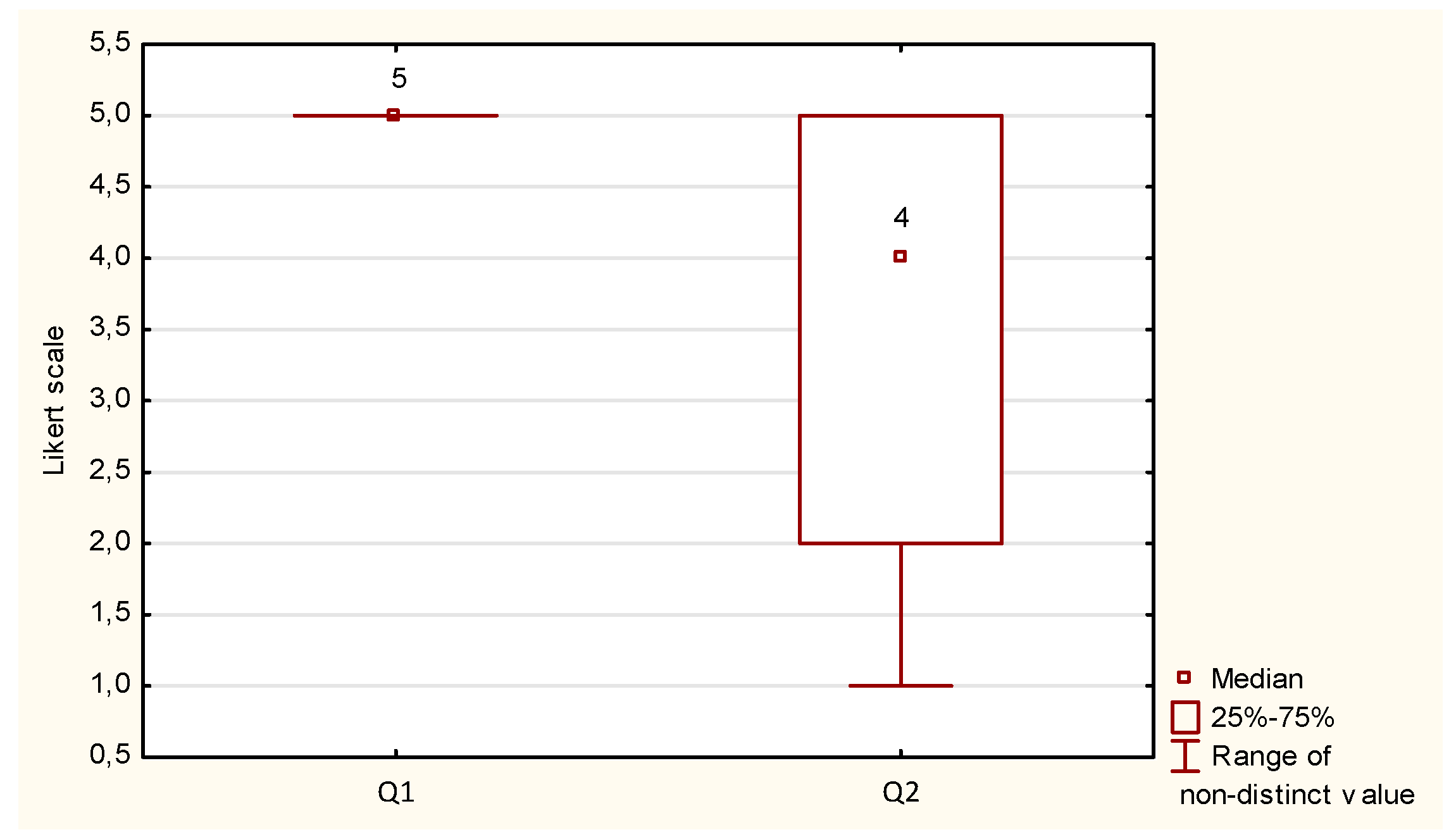

| Q1 | In our company, we communicate with our customers using traditional methods (meeting in the company seat, phone, traditional mail, email etc.) |

| Q2 | In our company, we communicate with our customers using modern communication methods (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger, livechat, mobile application) |

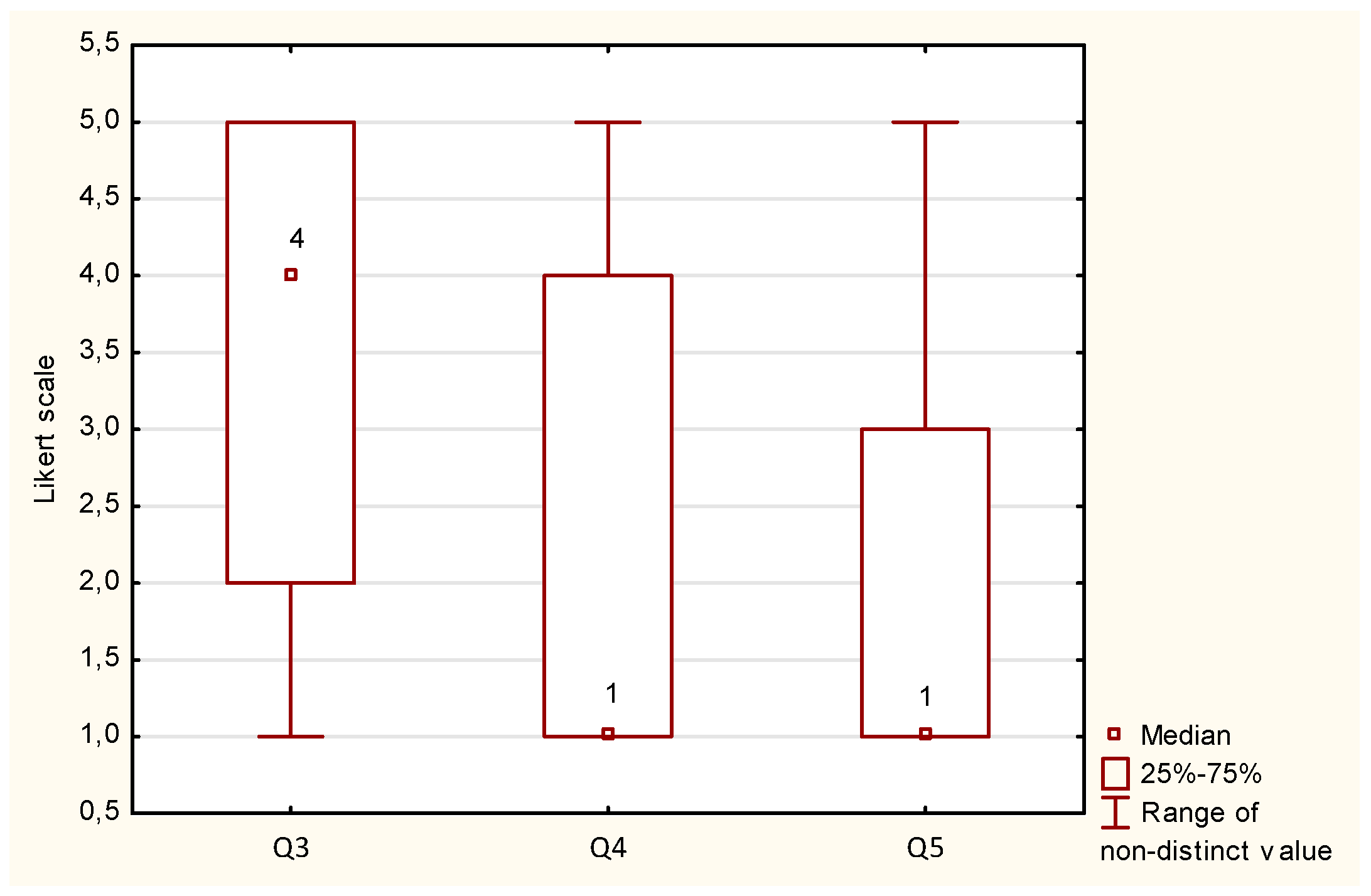

| Q3 | Our company customers most often buy using traditional methods in the company seat |

| Q4 | Our company customers most often buy from our e-shop |

| Q5 | Our company customers most often buy from other e-shops offering our products |

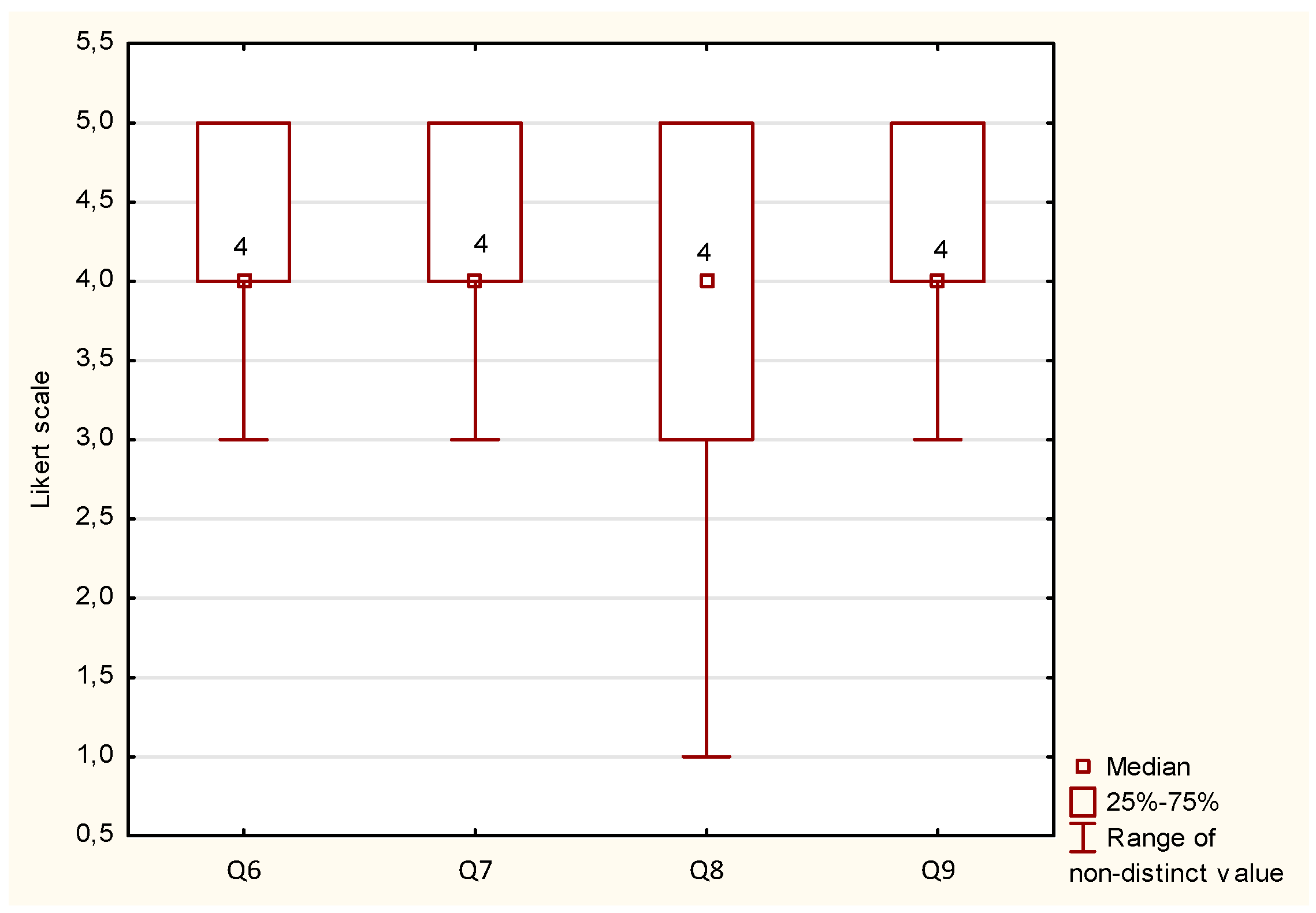

| Q6 | Modern technology implementation in customer service area contributes to improved service speed and effectiveness |

| Q7 | Modern technology implementation in customer service area contributes to increased customer satisfaction |

| Q8 | Modern technology implementation in customer service area contributes to improved financial results |

| Q9 | Modern technology implementation in customer service area contributes to improved company image |

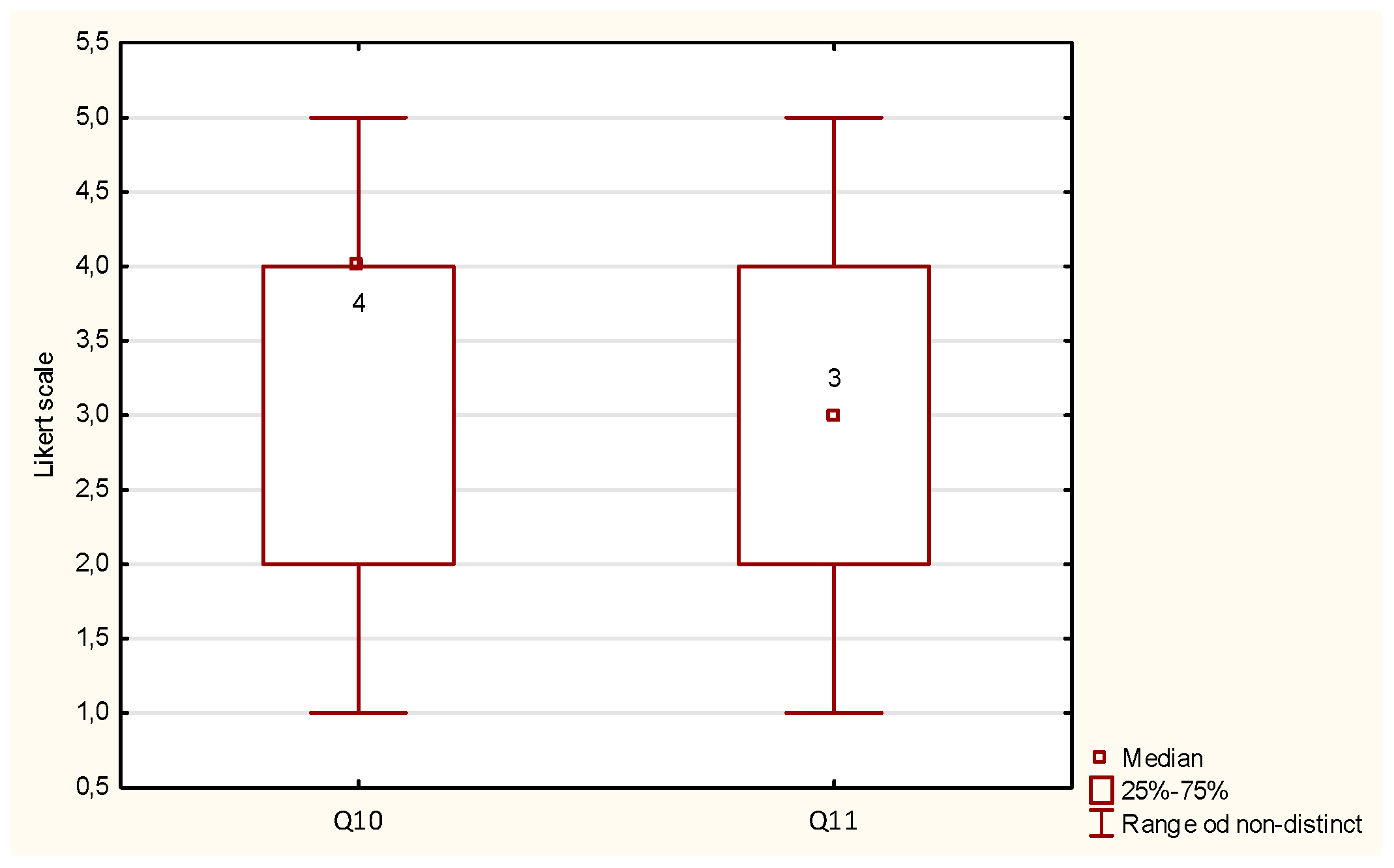

| Q10 | Major obstacles to implementing cutting-edge technology in the customer service area are the ones on the company’s part (e.g. absence of funds, low employee competences, absence of expertise). |

| Q11 | Major obstacles to implementing cutting-edge technology in the customer service area are the ones on the customers part (unwillingness to use new technology, no expertise, no trust in mobile devices and artificial intelligence) |

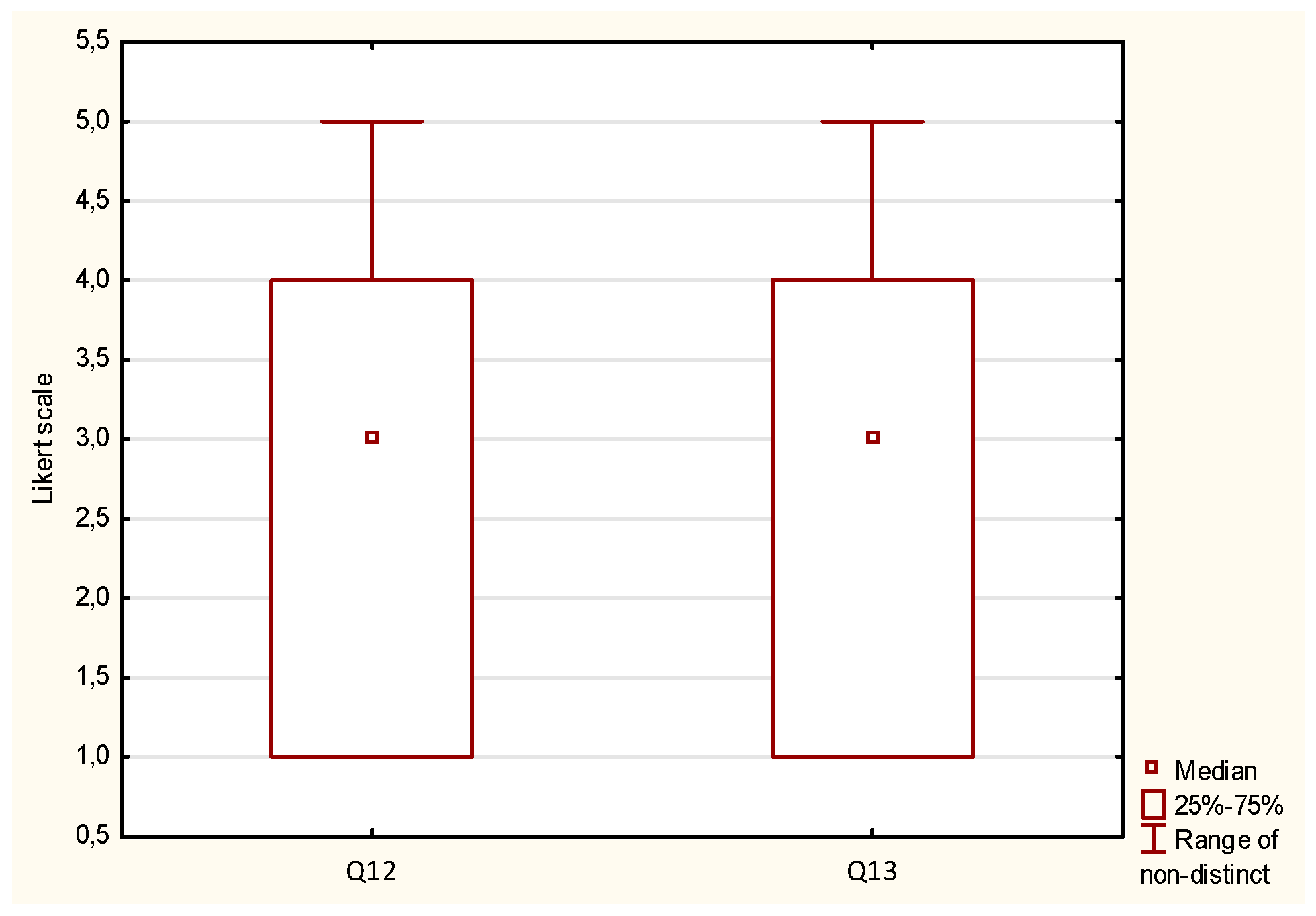

| Q12 | Our website allows to select a product/service meeting specific expectations and needs of customers (customize a product/service). |

| Q13 | We are fully prepared to serve digital customers (customers using mobile devices to do shopping or handle official matters etc.). |

| Q14 | In our company, we have positive return on investment. |

| Q15 | Profitability of our company is higher than that of competitors. |

| Q16 | Revenue increase in our company is higher than that of competitors. |

| variable | Scale summary: Mean=54.5209 St. deviation=8.40565 N valid:574 Cronbach's alpha: 0.690498 Standardized alpha: 0.707787 Average correlation between items: 0.143114 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean when removed | Value when removed | St. deviation when removed | Total item corr. | Alpha when removed | |

| Q1 | 49.82753 | 69.95110 | 8.363677 | 0.013513 | 0.697062 |

| Q2 | 50.94599 | 59.76189 | 7.730582 | 0.341092 | 0.669848 |

| Q3 | 50.94599 | 70.05806 | 8.370070 | -0.077460 | 0.729879 |

| Q4 | 52.37282 | 58.43243 | 7.644111 | 0.405820 | 0.659885 |

| Q5 | 52.41115 | 60.86231 | 7.801430 | 0.309551 | 0.674342 |

| Q6 | 50.39373 | 60.60456 | 7.784893 | 0.516028 | 0.652622 |

| Q7 | 50.45645 | 59.81256 | 7.733858 | 0.598068 | 0.645295 |

| Q8 | 50.64808 | 60.18626 | 7.757980 | 0.516881 | 0.651386 |

| Q9 | 50.33972 | 60.98738 | 7.809442 | 0.541732 | 0.652296 |

| Q10 | 51.15505 | 66.17283 | 8.134668 | 0.118613 | 0.697552 |

| Q11 | 51.41463 | 66.90823 | 8.179745 | 0.115372 | 0.695450 |

| Q12 | 51.59756 | 60.08020 | 7.751142 | 0.338188 | 0.670184 |

| Q13 | 51.70557 | 58.88369 | 7.673571 | 0.435813 | 0.656255 |

| Q14 | 50.67073 | 66.79577 | 8.172868 | 0.147738 | 0.690865 |

| Q15 | 51.39199 | 66.36726 | 8.146610 | 0.260211 | 0.680796 |

| Q16 | 51.53659 | 66.45424 | 8.151947 | 0.251563 | 0.681431 |

| Statistics value | value p | Report | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 0.44421 | p<0.01 | Based on the result of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: p < ,01 at the significance level α = 0.05, the hypothesis of normality of distribution for all variables should be rejected. |

| Q2 | 0.24763 | p<0.01 | |

| Q3 | 0.25666 | p<0.01 | |

| Q4 | 0.35623 | p<0.01 | |

| Q5 | 0.35566 | p<0.01 | |

| Q6 | 0.26014 | p<0.01 | |

| Q7 | 0.24364 | p<0.01 | |

| Q8 | 0.23986 | p<0.01 | |

| Q9 | 0.26711 | p<0.01 | |

| Q10 | 0.23646 | p<0.01 | |

| Q11 | 0.17765 | p<0.01 | |

| Q12 | 0.18604 | p<0.01 | |

| Q13 | 0.16099 | p<0.01 | |

| Q14 | 0.25938 | p<0.01 | |

| Q15 | 0.34096 | p<0.01 | |

| Q16 | 0.32985 | p<0.01 |

| Variable | Mann-Whitney U test (with a continuity correction) Relative to the variable: question Indicated results are significant with p < 0.05000 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank total Q1 | Rank total Q2 | U | Z | p | With corrections | p | N valid Q1 | N valid Q2 | |

| Answer (Likert scale) | 396007.00 | 263519.00 | 98494.00 | 11.79 | p<0.0001 | 13.38 | p<0.0001 | 574.00 | 574.00 |

| Dependent: Answer | ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis rank; Independent (grouping) variable: question Kruskal-Wallis test: H (2, N = 1722) = 279.9311 p = 0.000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | N valid | Rank total | Average rank | |

| Q3 | 1 | 574 | 647578.00 | 1128.18 |

| Q4 | 2 | 574 | 420432.50 | 732.46 |

| Q5 | 3 | 574 | 415492.50 | 723.85 |

| Dependent: Likert scale (answers) |

Value p for multiple (two-way) comparisons; answer Independent (grouping) variable: question Kruskal-Wallis test: H (2, N = 1722) = 279.9311 p = 0.000 |

|||

| Q3 R:1128.2 | Q4 R:732.46 | Q5 R:723.85 | ||

| Q3 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | ||

| Q4 | p<0.0001 | 1.0000 | ||

| Q5 | p<0.0001 | 1.0000 | ||

| Variable | Mann-Whitney U test (with a continuity correction) Relative to the variable: question Indicated results are significant with p < 0.05000 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank total Q10 | Rank total Q11 | U | Z | p | With corrections | p | N valid Q10 | N valid Q11 | |

| Answer (Likert scale) | 351945.50 | 307580.50 | 142555.50 | 3.95 | 0.00 | 4.06 | p<0.0001 | 574.00 | 574.00 |

| Variable | Mann-Whitney U test (with a continuity correction) (Sheet2) Relative to the variable: question Indicated results are significant with p < 0.05000 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank total Q12 | Rank total Q13 | U | Z | p | With corrections | p | N valid Q12 | N valid Q13 | |

| answer | 336138.50 | 323387.50 | 158362.50 | 1.14 | 0.26 | 1.16 | 0.25 | 574.00 | 574.00 |

| Dependent: answer | ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis rank; answer (Sheet2) Independent (grouping): question Kruskal-Wallis test: H (3, N = 2296) = 31.51557 p = 0.0000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | N valid | Rank total | Average rank | |

| Q6 | 1 | 574 | 690001.50 | 1202.09 |

| Q7 | 2 | 574 | 654514.00 | 1140.27 |

| Q8 | 3 | 574 | 592927.50 | 1032.97 |

| Q9 | 4 | 574 | 699513.00 | 1218.66 |

| Dependent: answer | Value p for multiple (bilateral) comparisons; answer (Sheet2) Independent (grouping) variable: question Kruskal-Wallis test: H (3, N = 2296) = 31.51557 p = 0.0000 | |||

| Q6 R:1202.1 | Q7 R:1140.3 | Q8 R:1033.0 | Q9 R:1218.7 | |

| Q6 | 0.6848 | 0.0001 | 1.0000 | |

| Q7 | 0.6848 | 0.0367 | 0.2708 | |

| Q8 | 0.0001 | 0.0367 | p<0.0001 | |

| Q9 | 1.0000 | 0.2708 | p<0.0001 | |

References

- Reddy, S.; Reinartz, W. Digital transformation and value creation: sea change ahead. GfK Marketing Intelligence Review (GFK MIR), 2017, 9(1), 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Delanogare, L.S.; Benitez, G. B.; Ayala, N. F.; Frank, A. G. The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 204, 383-394. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Ch.; Dallasega, P.; Orzes, G.; Sarkis, J. Industry 4.0 technologies assessment: A sustainability perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 229. [CrossRef]

- Taiminen, H.,; Karjaluoto, H. The usage of digital marketing channels in SMEs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2015, 22(4), 633-651. [CrossRef]

- Bacile, T.J. Digital customer service and customer-to-customer interactions: investigating the effect of online incivility on customer perceived service climate. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 31 (3), 441-464. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, C.; Shen, X.-L.; Wang, N. When digitalized customers meet digitalized services: A digitalized social cognitive perspective of omnichannel service usage. Int. J. Inf. Manag, 2020, 54, 102200. [CrossRef]

- Ulas, D. Digital Transformation Process and SMEs. Procedia Comput. 2019, 158, 662–671. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. M. L.; Teoh, S. Y.; Yeow, A.; Pan, G. Agility in responding to disruptive digital innovation: Case study of an SME. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 29(2), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Su, F.; Zhang, W.; Mao, J.-Y. Digital transformation by SME entrepreneurs: A capability perspective. Inf. Syst. J. 2017. 28(6), 1129 – 1157. [CrossRef]

- Matt, D.; Rauch, E. SME 4.0: The Role of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Digital Transformation. In Industry 4.0 for SMEs. Challenges, Opportunities and Requirements. Dominik T. Matt, V. Modrák, H. Zsifkovits Eds., Palgrave Macmillan: London 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cesaroni, F.M.; Consoli, D. Are small businesses really able to take advantage of social media? Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 13(4), 257-268.

- Cenamor, J.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. (2019). How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability, and ambidexterity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 196-206. [CrossRef]

- Kavoura, A.; Maris, G.; Masouras, A. Entrepreneurial Development and Innovation in Family Businesses and SMEs. Business Science Reference, IGI Global: Hershey, USA 2020.

- Masouras, A.; Pistikou, V.; Komodromos, M. Innovation Analysis in Cypriot Small and Medium-sized Enterprises and the Role of the European Union. In Entrepreneurship, Institutional Framework and Support Mechanisms in the EU, Apostolopoulos, N., Chalvatzis, K. and Liargovas, P. Eds., Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley 2021. [CrossRef]

- Report on the state of small and medium-sized enterprises in Poland, 2023. PARP. Warsaw 2023, pp. 6-7.

- Di Bella, L.; Katsinis, A.; Laguera Gonzalez, J.; Odenthal, L.; Hell, M.; Lozar, B. Annual Report on European SMEs 2022/2023, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg 2023. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. T. Mobile advertising to Digital Natives: preferences on content, style, personalization, and functionalityJ. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27(1), 67-80. [CrossRef]

- Szwajca, D. Digital Customer as a Creator of the Reputation of Modern Companies. FoM, 2019, 11(1), 255–266. [CrossRef]

- Jain, G.; Paul, J.; Shrivastava, A. Hyper-personalization, co-creation, digital clienteling and transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 12-23. [CrossRef]

- Olson, E. M.; Olson, K. M.; Czaplewski, A. J.; Key, T. M. Business strategy and the management of digital marketing. Bus. Horizons 2021, 64(2), 285-293. [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, S.; Saniuk, S. Modern Marketing for Customized Products Under Conditions of Fourth Industrial Revolution. In Industry 4.0. A global perspective. Duda, J., Gąsior, A. Eds. Routledge: New York 2021a.

- Barbier, E. B.; Burgess, J. C. The Sustainable Development Goals and the systems approach to sustainability, Economics, 17, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Lemańska-Majdzik A;, Okręglicka M. Wykorzystanie technologii informacyno-komunikacyjnych jako determinanta rozwoju przedsiębiorstw sektora MSP – wyniki badań. Przegląd Organizacji, 2017, 6, 44-50. [CrossRef]

- Ziółkowska, M. J. Digital Transformation and Marketing Activities in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13(5), 2512. [CrossRef]

- Witek-Hajduk, M.K.; Grudecka, A.M.; Napiórkowska, A. E-commerce in the internet-enabled foreign expansion of Polish fashion brands owned by SMEs. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2022, 26(1), 51-66. [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Marketing activities on the Internet in the era of the first wave of the pandemic COVID-19 in the SME sector in Poland. Zbliżenia Cywilizacyjne 2023, XIX (1), 87-105).

- Hebbert, L. Digital Transformation: Build your Organization’s Future for the Innovation. Bloomsburry Publishing Plc: London 2017.

- Bouwman, H.; Nikou, S.; Molina-Castillo, F. J.; De Reuver, M. The impact of digitalization on business models. Digit. Policy Regul. G. 2018. 20(2), 105–124. [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, S.; Saniuk, S. Challenges of business model concept of small- and medium-sized enterprise cooperation. In Industry 4.0. A glocal perspective. Eds. Duda, J., Gąsior, A. Eds. Routledge: New York 2021b.

- Moreira F.; Ferreira, M. J.; Seruca, I. 4.0 – the emerging digital transformed enterprise? Procedia Comput. 2018, 138, 525–532. [CrossRef]

- Grube, D.; Malik, A. A.; Bilberg, A. SMEs can touch Industry 4.0 in the Smart Learning Factory. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 31, 219–224. [CrossRef]

- Andriole, S. Five myths about digital transformation. "MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2017, 58(3), 20-22.

- Fabrizi, B.; Lam, E.; Girard, K.; Irvin, V. Digital Transformation Is Not About Technology. Harv. Bus. Rev, 2019, 3, March 13.

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: a review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28(2), 118-144. [CrossRef]

- Peter, M.K.; Kraft, C.; Lindeque, J. Strategic action fields of digital transformation: an exploration of the strategic action fields of swiss SMEs and large enterprises. Journal of Strategy Management (JSM), 2020, 13(1), 160–180. [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, C.; Stephen, A. T. A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: Research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. J. Mark. 2016, 80(6), 146-172. [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P. K.,; Li, H. A. Digital Marketing: A Framework, Review and Research AgendaInt. J. Res. Mark. 2017, 34(1), 22-45. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Kang, S.; Lee, K. H. Evolution of digital marketing communication: Bibliometric analysis and network visualization from key articles. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 552-563. [CrossRef]

- Krishen, A. S.; Dwivedi, Y. K.; Bindu, N.; Kumar, K. S. A broad overview of interactive digital marketing: A bibliometric network analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 183-195. [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T.C.; Nichola, S. The Internet revolution: Some global marketing implications. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2003, 21(6), 363-369. [CrossRef]

- Berthon, P.R.; Pitt, L.F.; Plangger, K.; Shapiro, D. (2012). Marketing meets web 2.0, social media and creative consumers: Implications for international marketing strategy. Bus. Horizons, 2012, 55(3), 261-271. [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, P. E. How digital technologies are enabling consumers and transforming the practice of marketing. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2014, 22(2), 149-150. [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, A. Internet Marketing: A practical approach. Third edition. Routledge: London 2018.

- Fraccastoro, S.; Gabrielsson, M.; Pullins, E. B. The integrated use of social media, digital, and traditional communication tools in the B2B sales process of international SMEs. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30(4), 101776. [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Khan, Z.; Wood, G.; Knight, G. COVID-19 and digitalization: The great acceleration. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 602–611. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.; Clear, F.; Harindranath, G.; Dyerson, R., Harris, L.; Rea, A. Web 2.0 and micro-businesses: an exploratory investigation. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2012, 19(4), 687-711. [CrossRef]

- Cacciolatti. L. A.; Fearne, A. (2013). Marketing intelligence in SMEs: implications for the industry and policy makers. Mark. Intell. Plan, 2013, 31(1), 4-26. [CrossRef]

- Omar, F. I.; Othman, N. A.; Hassan, N. A. Digital inclusion of ICT and its implication among entrepreneurs of small and medium enterprises Int. j. eng. adv. technol. 2019, 8(5), 747-752. [CrossRef]

- Odoom, R.; Anning-Dorson, T.; Acheampong, G. Antecedents of social media usage and performance benefits in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). J. Enterp. Inf. 2017, 30(3), 383-399. [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R., Rohm, A.; Crittenden, V. L. We’re all connected: the power of the social media ecosystem. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54(3), 265-273. [CrossRef]

- Salo, J. Social media research in the industrial marketing field: Review of literature and future research directions. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 66, 115-129. [CrossRef]

- Lacoste, S. Perspectives on social media and its use by key account managers. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 54, 33-43. [CrossRef]

- Itani, O. S.; Agnihotri, R.; Dingus, R. Social media use in B2B sales and its impact on competitive intelligence collection and adaptive selling: Examining the role of learning orientation as an enabler. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 66, 64-79. [CrossRef]

- Bill, F., Feurer, S. & Klarmann, M., Salesperson social media use in business-to-business relationships: An empirical test of an integrative framework linking antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 2020, 48, 734-752. [CrossRef]

- Müller, J. M., Pommeranz, B., Weisser,J. & Voigt, K. I., Digital, Social Media, and Mobile Marketing in industrial buying: Still in need of customer segmentation? Empirical evidence from Poland and Germany. Industrial Marketing Management,2018, 73, 70-83. [CrossRef]

- Tlapana, T. & Dike, A., Social Media Usage Patterns amongst Small and Medium Enterprises (SMMEs) in East London, South Africa. Global Media Journal, 2020, 18(35):212.

- Arnone, L. & Deprince, E., Small firms internationalization: Reducing the psychic distance using social networks. Global Journal of Business Research, 2016, 10(1), 55-63. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2825461.

- Varadarajan, R., Welden, R. B., Arunachalam, S., Haenlein, M. & Gupta, S., Digital product innovations for the greater good and digital marketing innovations in communications and channels: Evolution, emerging issues, and future research directions. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 2021, 39(2), 482-501. [CrossRef]

- van Esch, P. & Black, J. S., Artificial Intelligence (AI): Revolutionizing Digital Marketing. Australasian Marketing Journal, 29(3), 2021, 199-203. [CrossRef]

- Chmielarz, W., The Usage of Smartphone and Mobile Applications from the Point of View of Customers in Poland. Information, 11 (4),2020, 220. [CrossRef]

- Szumski, O., Digital payment methods within Polish students - leading decision characteristics. Procedia Computer Science, 2020, 176, 3456-3465. [CrossRef]

- Taiminen, H., Ensio Karjaluoto, H. & Nevalainen, M., Digital channels in the internal communication of a multinational Corporation. Corporate Communications An International Journal, 2014, 19(3), 275-286. [CrossRef]

- Styvén, M. E., Wallström, Å., Benefits and barriers for the use of digital channels among small tourism companies. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2019, 19(1), 27-46. [CrossRef]

- Taiminen, H.M., Karjaluoto, H., The usage of digital marketing channels in SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 2015, 22(4), pp. 633-651.

- de Vries, L., Gensler, S., & Leeflang, P. S., Effects of traditional advertising and social messages on brand-building metrics and customer acquisition. Journal of Marketing, 2017 81(5), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S., Huang, L., Roth, M. S., & Madden, T. J. ,The influence of social media interactions on consumer–Brand relationships: A three-country study of brand perceptions and marketing behaviors. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 2016, 33(1), 27–41. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Bezawada, R., Rishika, R., Janakiraman, R., & Kannan, P. K., From social to sale: The effects of firm-generated content in social media on customer behavior. Journal of Marketing, 2016, 80(1), 7–25. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A. R., The Influence of Perceived Social Media Marketing Activities on Brand Loyalty: The Mediation Effect of Brand and Value Consciousness. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 2017, 29(1), 129-144. [CrossRef]

- Adam, M., Ibrahim, M., Ikramuddin, I. & Syahputra, H., The Role of Digital Marketing Platforms on Supply Chain Management for Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) at Indonesia. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 2020, 9(3), 1210-1220. [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, S., & Taylor, C. R., Social media and international advertising: Theoretical challenges and future directions. International Marketing Review, 2013, 30(1), 56–71. [CrossRef]

- Alarc´on-del-Amo, M., Rialp-Criado, A., & Rialp-Criado, J., Examining the impact of managerial involvement with social media on exporting firm performance. International Business Review, 2018, 27(2), 355–366. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., Tate, M., Zhang, H., Chen, S., & Liang, B., Social media ties strategy in international branding: An application of resource-based theory. Journal of International Marketing, 2018, 26(3), 45–69. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H., & Hurd, F., Exploring the impact of digital platforms on SME internationalization: New Zealand SMEs use of the Alibaba platform for Chinese market entry. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 2018, 19(2), 72–95. [CrossRef]

- Karjaluoto, H., Mustonen, N. & Ulkuniemi, P., The role of digital channels in industrial marketing communications. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 2015, 30(6), 703-710. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Y., Pauleen, D. J., & Zhang, T., How social media applications affect B2B communication and improve business performance in SMEs. Industrial Marketing Management, 2016, 54, 4–14. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D. L., & Fodor, M., Can you measure the ROI of your social media marketing? MIT Sloan Management Review, 2010, 52(1).

- Mokhtar, N.F., Internet marketing adoption by small business enterprises in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2015, 6(1), 59–65.

- Johnston, D. A., Wade, M. & Mcclean, R., Does e-Business Matter to SMEs? A Comparison of the Financial Impacts of Internet Business Solutions on European and North American SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 2007, 45(3), 354-361. [CrossRef]

- Chong, W. K., Man, K. L. & Kim, M., The impact of e-marketing orientation on performance in Asian SMEs: a B2B perspective. Enterprise Information Systems, 2018, 12(1), 4-18. [CrossRef]

- Deryabina, G., & Trubnikova, N., Digital B2B communications: economic and marketing effect. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 2020, 87. [CrossRef]

- Nobre, H., & Silva, D., Social Network Marketing Strategy and SME Strategy Benefits. Journal of Transnational Management, 2014, 19(2), 138-151. [CrossRef]

- Cepel, M., Stasiukynas, A., Kotaskova, A., & Dvorsky, J., Business environment quality index in the sme segment. Journal of Competitiveness, 2018, 10(2), 21-40. [CrossRef]

- Rydzewska, A., Influence of financialization on the business activity of non-financial enterprises in Poland. Ekonomia i Prawo. Economics and Law, 2023, 22(4), 777–807. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H., Yang, Z. & Huang, R., The digitalization and public crisis responses of small and medium enterprises: Implications from a COVID-19 survey. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 2020, 14, 19. [CrossRef]

- Szwajca D. & Rydzewska A., Digital transformation as a challenge for SMES in POLAND in the context of crisis relating to Covid-19 pandemic. Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology, Organization and Management, 2022, 161, 289-305. [CrossRef]

- Omar, S. I. et al. Digital Marketing: An Influence towards Business Performance among Entrepreneurs of Small and Medium Enterprises, Int. J. Acad. Res. 2020, 10(9), 126-141. [CrossRef]

- Amoah, J.; Jibril, A. B. Inhibitors of social media as an innovative tool for advertising and MARKETING communication: Evidence from SMEs in a developing country. Innovative Marketing, 2020, 16(4), 164-179. [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, R. Does digital marketing adoption enhance the performance of micro and small enterprises? Evidence from women entrepreneurs in Ado-Odo Ota Local Government Area, Ogun State, Nigeria. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2022, 17(1), 160-173. [CrossRef]

- Brzaković, A. et al. Empirical Analysis of the Influence of Digital Marketing Elements on Service Quality Variables in the Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises Sector in the Republic of Serbia. Sustainability 2021, 13(18), 10264. [CrossRef]

- Pollak, F.; Markovic, P. Size of Business Unit as a Factor Influencing Adoption of Digital Marketing: Empirical Analysis of SMEs Operating in the Central European Market. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 71. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, M. A. et al. Utilization of Digital Marketing Channels to Optimize Business Performance Among SMEs In Jakarta, Indonesia. International Journal of Innovation and Business Strategy (IJIBS), 2023, 18(1), 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Cao, G. & Weerawardena, J. (2023). Strategic use of social media in marketing and financial performance: The B2B SME context. Industrial Marketing Management, 2023, Vol. 111, 41-54. [CrossRef]

- Społeczeństwo informacyjne w Polsce w 2022 r. GUS, Warszawa 2022. Retrieved 04.07.2024 from https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/nauka-i-technika-spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne-w-polsce-w-2022-roku,2,12.html.

- Poland in the Digital Economy and Society Index. European Commission. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi-poland.

- Digitalisation in Europe – 2023 edition, Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/digitalisation-2023.

- Cyfryzacja sektora MSP w Polsce. Związek Przedsiębiorców i Pracodawców, październik 2023. https://zpp.net.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/02.11.2023-Raport-Cyfryzacja-sektora-MSP-w-Polsce.pdf.

- Are small businesses ready to compete as consumers move online?, Retrieved 20.11.2023 from https://www.economicsobservatory.com/question/are-small-businesses-ready-compete-consumers-move-online.

- Beheshti,H. M & Sangari, E. S., The benefits of e-business adoption: an empirical study of Swedish SMEs. Service Business 2017, 1(3), 233-346. [CrossRef]

- Skare, M., de las Mercedes de Obesso, M. & Ribeiro-Navarrete, S., Digital transformation and European small and medium enterprises (SMEs): A comparative study using digital economy and society index data. International Journal of Information Management, 2023, 68. 102594. [CrossRef]

- Etim, G.S., James E.E., Nnana, A. N., Okeowo, V. O., E-marketing Strategies and Performance of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises: A New-normal Agenda. Journal of Business and Management Studies, 2021, 3(2), 162-172. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. et al. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 530-535. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Industry 5.0 and Society 5.0—Comparison, complementation and co-evolution. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 64, 424-428.

- Jaiwant, S.V. The Changing Role of Marketing: Industry 5.0 - the Game Changer. In Transformation for Sustainable Business and Management Practices: Exploring the Spectrum of Industry 5.0, Saini, A. and Garg, V. Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, 2023, pp. 187-202. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.M.; Kushwaha, B.P.; Singh, R. Visualisation of global research trends and future research directions of digital marketing in small and medium enterprises using bibliometric analysis. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev, 2023, 30(3), 621-641. [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M., Industry 4.0, digitization, and opportunities for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020, 252. [CrossRef]

- Oláh, J., Novotná, A., Sarihasan, I., Erdei, E., & Popp, J., Examination of The Relationship Between Sustainable Industry 4.0 and Business Performance. Journal of Competitiveness, 2022, 14(4), 25-43. [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A. Creating Superior Customer Value in the Now Economy. J. Creat. Value, 2020, 6(1), 20-33. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, D. E.; Patti, C. H. The evolution of IMC: IMC in a customer-driven marketplace. J. Mark. Commun. 2009, 15(2–3), 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Vrchota,J., Volek, T. and Novotna, M., Factors Introducing Industry 4.0 to SMES, Social Sciences, 2019 8 (5), p. 130.

- Masouras, A., Pistikou, V. and Komodromos, M., Innovation Analysis in Cypriot Small and Medium-sized Enterprises and the Role of the European Union, Apostolopoulos, N., Chalvatzis, K. and Liargovas, P. (Ed.) Entrepreneurship, Institutional Framework and Support Mechanisms in the EU, Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, 2021, pp. 115-131. [CrossRef]

| Analysis type | Research tools |

| Analysis of statistical data Research Questions : RS 1 | |

| Comparative analysis of secondary data derived from reports by the European Commission, Eurostat and Statistics Poland | Deductive reasoning and structural analysis |

| Analysis of the survey results Research Question : RS 2 | |

| Preliminary analysis | |

| Assessment of the reliability of the survey questionnaire | Cronbach’s alpha test |

| Analysis of the distribution of normality of variables Verification of null research hypothesis H0 1 |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test |

| Statistical analysis | |

| Verification of null research hypotheses | |

| H0 2; H0 4; H0 5 | Box-plots, Mann-Whitney U test |

| H0 3; H0 7 | Box-plots, ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis tests and Dunn’s post-hoc tests |

| H0 6 | Kendall's rank correlation coefficient/ MARSplines |

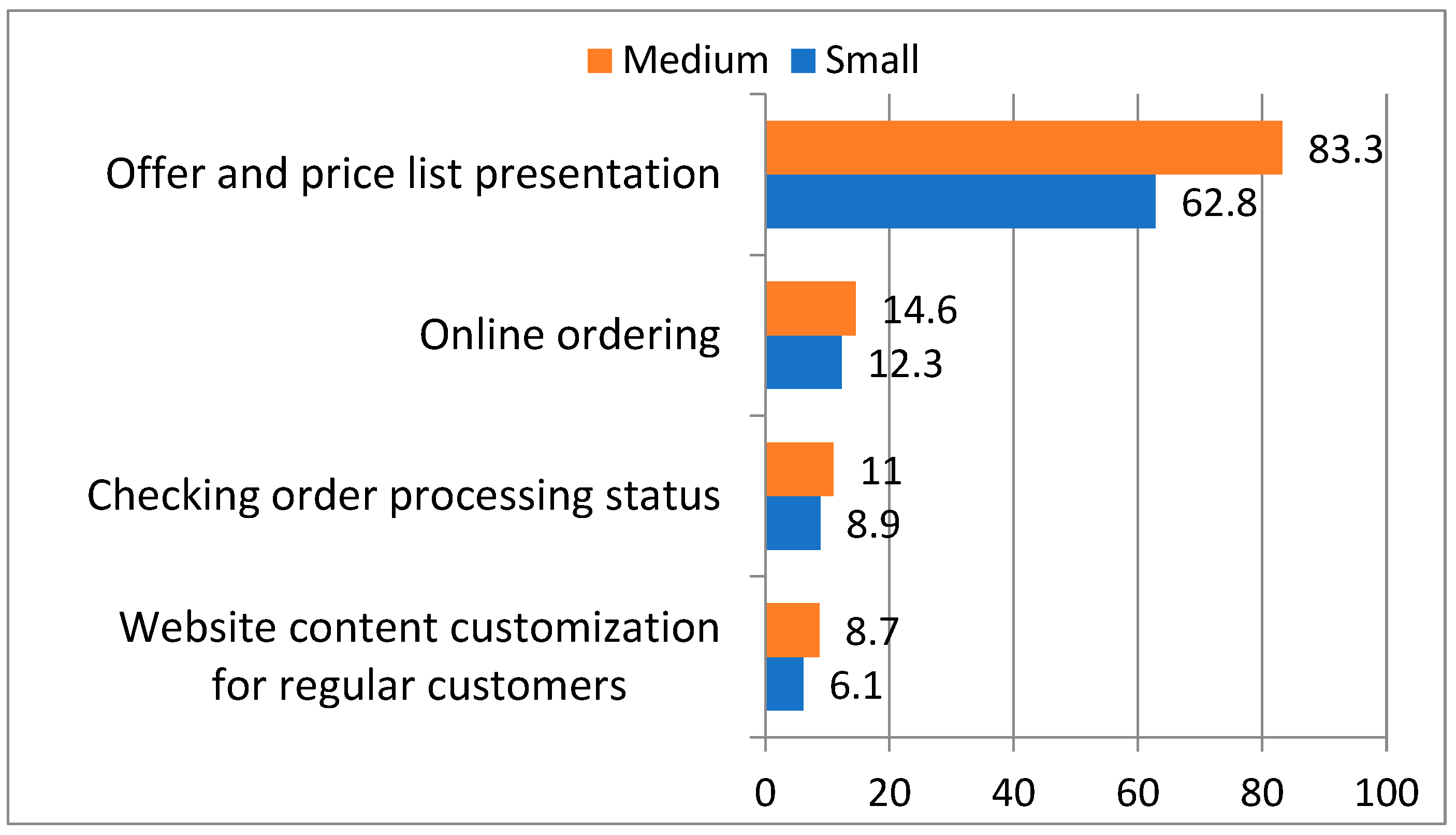

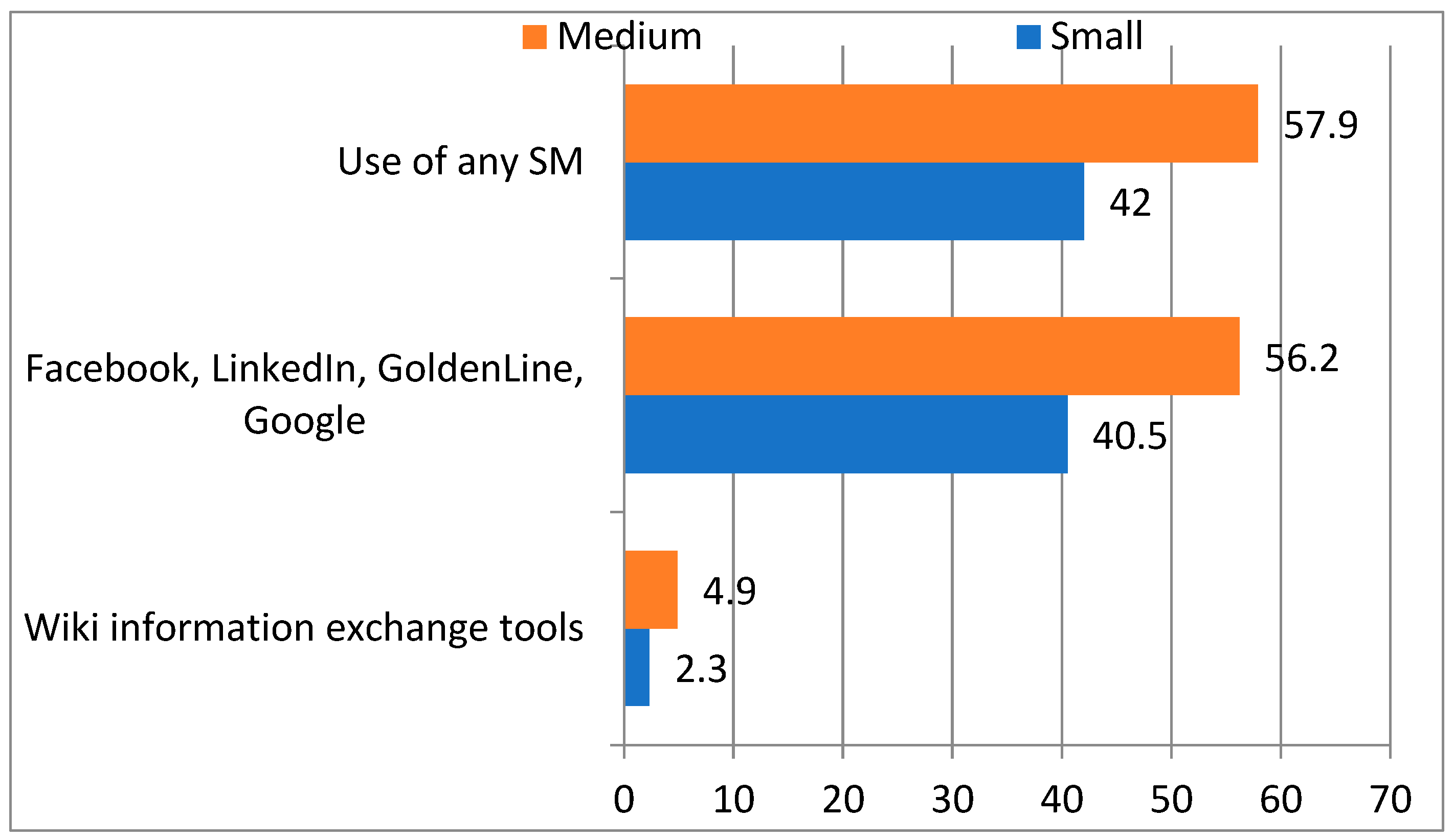

| Industry 4.0 tools | Medium-sized companies | Small companies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloud services | 33.5% | 19.2% | |

| CRM | 7.9% | 3.8% | |

| Internet of things | In general | 31.8% | 14.9% |

| Customer service | 5.1% | 1.7% | |

| Artificial Intelligence | In general | 5.0% | 1.9% |

| Marketing and sale | 1.7% | 0.9% | |

| Variable | Kendall's tau correlation. BD removed in pairs. Marked correlation coefficients are significant with p <0.05000 |

||

| Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | |

| Q1 | 0,081956 | -0,067188 | -0,100356 |

| Q2 | 0,117383 | 0,129314 | 0,103223 |

| Q3 | 0,028331 | 0,016375 | -0,000893 |

| Q4 | 0,002843 | 0,097389 | 0,126442 |

| Q5 | 0,015420 | 0,051675 | 0,074143 |

| Q10 | -0,112189 | -0,070817 | -0,073550 |

| Q11 | -0,024304 | 0,030237 | 0,015573 |

| Q12 | -0,006976 | 0,072175 | 0,052036 |

| Q13 | 0,049448 | 0,068068 | 0,088144 |

| Characteristics | Dependent variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | |

| Model equation | Q14 = 3,98687048471834e+000 - 1,07316216029357e-001*max(0; Q10-1,00000000000000e+000) + 2,72355316354401e-001*max(0; Q2-4,00000000000000e+000) | Q15 = 3,37263580519805e+000 - 1,18537225996519e-001*max(0; 4,00000000000000e+000-Q2) - 6,01555038434376e-002*max(0; Q10-1,00000000000000e+000) | Q16 = 3,51939935571921e+000 - 7,21101480713554e-002*max(0; 4,00000000000000e+000-Q2) + 5,94604120550734e-002*max(0; Q4-1,00000000000000e+000) - 6,01464024944235e-002*max(0; Q10-1,00000000000000e+000) - 1,08129596432386e-001*max(0; Q1-1,00000000000000e+000 |

| Penalty | 2.000000 | 2.000000 | 2.000000 |

| Threshold | 0.000500 | 0.000500 | 0.000500 |

| GCV error | 1.128497 | 0.662174 | 0.675047 |

| Predictors | Number of references to each predictor | ||

| Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | |

| Q1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Q2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q4 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Q5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q10 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Null hypothesis | Method of verification | Result |

|---|---|---|

| H0 1 | Kolmogorov-Smirnov test | The null hypothesis was rejected, the alternative hypothesis was accepted |

| H0 2 | Mann-Whitney U test | The null hypothesis was rejected, the alternative hypothesis was accepted |

| H0 3 | ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis tests and Dunn’s post-hoc tests | The null hypothesis was rejected, the alternative hypothesis was accepted |

| H0 4 | Mann-Whitney U test | The null hypothesis was rejected, the alternative hypothesis was accepted |

| H0 5 | Mann-Whitney U test | The null hypothesis was accepted |

| H0 6 | Kendall's rank correlation coefficient/ MARSplines | Ambiguous results |

| H0 7 | ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis tests and Dunn’s post-hoc tests | The null hypothesis was rejected, the alternative hypothesis was accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).