1. Introduction

The digital transformation model has radically transformed competitive dynamics via what Winter, (1984)called "creative destruction," wherein technology-led innovations upset the existing business model paradigms and generate new competitive pushes, with especial impact upon smaller enterprises that need to manage the pull of digital opportunities against the push of resource-based limits theorized in Resource-Based View (RBV) scholarship as VRIN resource limits (valuable, rare, inimitable, non-substitutable) defining smaller firms (Barney, 1991; A. Bharadwaj et al., 2013). Digital marketing technologies constitute strategy assets allowing smaller enterprises to counter the scale disadvantages of the past via what Porter, (1985)theorized as the strategies of differentiation and cost leadership, utilizing inexpensive mechanisms of customer engagement and data-based decision capabilities generating competitive parity with the larger firms, but the adoption processes involve intricate interactions of the technological attributes, organizational capabilities, and environmental settings extending outside the limits of rational choice Theory's cost-benefit calculations to the limits of institutional Theory's coercive, mimetic, and normative pushes (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; El-Rayes et al., 2023; Venkatesh, 1999). The Technology-Organizations-Environment (TOE) model integrates these theoretical insights by combining Rogers, (2003)Innovation Diffusion Theory (technological setting), Resource-Based View (organisational setting), and Institutional Theory (environmental setting) in order to gain broad-based understanding of innovation adoption processes, tested in breadth across various technological applications but hardly explored in the digital marketing contexts of emerging markets wherein unusual institutional voids along with resource limits can radically transform established relationships as theorized (Tornatzky, 1992).

Systematic theoretical examination identifies three inherent limitations on existing knowledge: first, the geographic bias of TOE framework applications in the context of developed economy settings causes "institutional void" blindness, as theories grounded in mature institutional settings fail to adequately meet emerging market conditions of weak regulatory environments, immature factor markets, and information asymmetry that radically transform adoption decision calculus (Díaz-Arancibia et al., 2024; Oliveira et al., 2011); second, IT system-centric technological concentration omits consideration of integrated digital marketing ecosystems, failing to capture what Teece, (1996) posited as dynamic capabilities the capability of the organization to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies in order to deal with swiftly shifting environments transitionally pertinent for digital marketing's need for continuous capability building and platform integration (Abed, 2020; Winter, 2003); third, adoption research's focus on initial implementation choices ignores what Kohli & Melville, (2019)called the "business value of IT" theoretical model, whereby technology adoption is explained in terms of organizational performance outcomes via complementary resource deployment and capability-building processes, critically important in the context of resource-limited environments in which ROI justification defines investment choices (Almeida et al., 2016; Kohli & Melville, 2019; Zahra et al., 2000). Indonesia provides these theoretical gaps as an emerging economy in which SMEs account for 60% of GDP but experience chronic intention-adoption gaps in the face of government digitalization programs, proposing that mainstream theoretical constructs fail to adequately explain barriers to adoption as well as mechanisms of performance in contexts defined by the presence of archipelagic geography, differential infrastructure improvement, as well as differential institutional enforcement creating natural experiments in the version of TOE relationships as measured in various contexts (Mayer et al., 1995). This study addresses these theoretical limitations through systematic empirical investigation of digital marketing adoption among Indonesian SMEs using an extended TOE framework that incorporates emerging economy institutional theory perspectives, examining how resource constraints and institutional voids moderate established theoretical relationships while investigating adoption-performance linkages through dynamic capabilities and business value of IT theoretical lenses.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Technological and Digital Marketing Adoption

The technological dimension encompasses digital marketing technology characteristics through four Innovation Diffusion Theory attributes: relative advantage (comparative benefits including cost-effectiveness and market reach), compatibility (alignment with existing processes and infrastructure), complexity (implementation difficulty particularly relevant for resource-constrained SMEs), and trialability (experimentation opportunity reducing perceived risk), which become critical for digital marketing adoption given these technologies' inherent complexity involving multiple integrated platforms requiring continuous organizational learning and dynamic capability development (Davison, 1985; Heiens et al., 2015; Nepal & Rogerson, 2020; Venkatesh & Bala, 2008; Yang et al., 2022). Meta-analytical evidence consistently demonstrates technological factors as significant adoption predictors, with Innovation Diffusion Theory and Technology Acceptance Model providing theoretical foundation that perceived technology attributes fundamentally determine adoption intentions through cognitive evaluation processes, while emerging market contexts amplify these relationships due to infrastructural constraints and resource limitations that make technology characteristics particularly deterministic for SME adoption feasibility under challenging institutional conditions (Damanpour, 2010; Tornatzky et al., 1990; Venkatesh & Bala, 2008). Extensive empirical validation confirms that relative advantage, compatibility, reduced complexity, and trial opportunities constitute fundamental innovation adoption determinants across diverse contexts, supporting:

H1: Technology has effected to Digital Marketing Adoption

2.2. Organizational Context and Digital Marketing Adoption

The organizational dimension encompasses internal characteristics that determine a firm's readiness and capacity for technology adoption, grounded in Resource-Based View (RBV) theory which posits that superior internal capabilities enable competitive advantage through effective resource deployment and technology implementation (A. S. Bharadwaj, 2000; Sambamurthy et al., 2003). Four critical organizational factors influence adoption: management support, representing leadership commitment and strategic resource allocation that signals organizational priorities (Jeyaraj et al., 2006; Khazanchi et al., 2007; Numa & Ohnishi, 2023); organizational resources, encompassing financial, human, and technological assets necessary for implementation sustainability (Wade & Hulland, 2004); innovation culture, reflecting organizational openness to change and experimental capacity (Khazanchi et al., 2007; Škerlavaj et al., 2010); and existing IT capability, comprising technological infrastructure and accumulated digital competencies that provide integration foundations (A. S. Bharadwaj, 2000). SME contexts present unique challenges including resource constraints, informal structures, and concentrated decision-making that create distinctive adoption dynamics compared to larger enterprises (Dasgupta et al., 1999).

Empirical research consistently demonstrates organizational readiness as the strongest predictor of technology adoption success, with substantial explanatory power across organizational contexts (Hradecky et al., 2022; Zhen et al., 2021). RBV theory suggests that organizations possessing superior internal capabilities management support, adequate resources, innovation-oriented culture, and IT competencies are better positioned to recognize technology benefits, allocate implementation resources, and manage adoption processes effectively(Chen et al., 2021; Kraaijenbrink et al., 2010). Meta-analytical evidence confirms that organizational characteristics consistently predict technology adoption success across various contexts, though SME-specific constraints require context-sensitive investigation for digital marketing adoption (Taherdoost et al., 2024):

H2: Organization has effect to Digital Marketing Adoption

2.3. Environmental Context

The environmental dimension encompasses external pressures and opportunities influencing organizational technology adoption decisions, theoretically grounded in Institutional Theory which explains organizational behavior through three isomorphic pressures: coercive (regulatory requirements and stakeholder expectations), mimetic (imitation of successful competitors under uncertainty), and normative (professional standards and industry best practices) that collectively drive organizational conformity and legitimacy-seeking behavior (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Podsakoff et al., 2009). Four critical environmental factors operationalize these theoretical mechanisms: competitive pressure represents mimetic isomorphism as organizations respond to industry digitalization trends and competitor strategic actions to maintain market position (Dess & Davis, 1984; Liu et al., 2024; M. Porter, 1985); regulatory environment embodies coercive isomorphism through government policies, support programs, and legal frameworks that mandate or incentivize digital adoption (Malope et al., 2021; Rizvi et al., 2024); market characteristics reflect normative isomorphism via customer expectations, supplier capabilities, and industry maturity standards that create stakeholder compliance pressures (Lopes et al., 2022; Madhavaram et al., 2024); and infrastructure availability constitutes structural environmental constraints determining technological feasibility through digital infrastructure quality, connectivity, and support service availability (Boahene Osei, 2024; Tang et al., 2023).

Institutional Theory predicts that environmental pressures drive technology adoption as organizations seek legitimacy and competitive parity within their institutional fields, with empirical evidence demonstrating stronger environmental influence in developing economies where institutional voids and infrastructure limitations create heightened dependency on external support systems compared to mature digital ecosystems (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Ramdani et al., 2007). The theory's core proposition that organizations respond to institutional pressures through adaptive behavior to maintain legitimacy provides theoretical foundation for expecting positive environmental influence on digital marketing adoption, supported by meta-analytical evidence identifying competitive pressure, regulatory support, market characteristics, and infrastructure availability as consistent predictors across organizational contexts (Obiakor et al., 2022; Oliveira-Dias et al., 2022). This theoretical framework suggests that environmental factors create institutional imperatives for digital marketing adoption through legitimacy pressures and resource dependencies (Ali Abbasi et al., 2022):

H3: Environment has effect to Digital Marketing Adoption

2.4. Digital Marketing and Business Performance

Digital marketing involves the systematic implementation of digital platforms and technologies to perform marketing activities through electronic media, distinguishing it from the past practice of marketing based on the potential of digital marketing for instantaneous bidirectional communication, data-informed targeting, as well as performance measurement that informs continuous optimization of related capabilities like social media marketing, search engine optimization, and content marketing. These capabilities function as integrated capability systems as much as distinct tools (Im & Workman, 2004; Kannan & Li, 2016; Workman & Lee, 2022). For small- and medium-sized enterprises, digital marketing is equalizing the playing field by ensuring equal access to sophisticated marketing capabilities that were out of reach based on insufficient resources; however, tangible success requires refined organizational learning processes involving the acquisition of technological capabilities, strategy alignment, as well as skill-building, which is beyond technology implementation (Nadányiová et al., 2021; Neneh, 2022; Neneh & Dzomonda, 2024).

The conceptual foundation linking digital marketing adoption to business performance is based on Resource-Based View (RBV) theory, which explains sustainable competitive advantage through VRIN-based resources (Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, Non-substitutable), as well as capabilities theory, extending RBV by describing the formation, combination, and recombination of internal-external capabilities of firms in swiftly evolving environments (Barney, 1991; Teece, 1996). Digital marketing adoption creates competitive advantage along three mechanisms based on RBV: resource complementarity (in which digital technologies amplify pre-existing marketing assets via complementary interactions), capability growth (in which the processes of adoption develop new customer analytics-relationships-based competencies of the organization), as well as competitive advantage based on positioning (in which technology-assisted marketing capabilities provide uncompetitive differentiation unavailable for non-users of these technologies) (A. S. Bharadwaj, 2000; Kohli & Melville, 2019). Meta-analytic empirical evidence shows numerous positive relationships of various performance outcomes with technology-based adoption, covering operational effectiveness, market performance, as well as financial measures, with the size of the effects supporting theoretical proclamations of RBV that technology-based capabilities, when implemented efficiently, generate tangible competitive advantages when reinforced by complementary investments in the organization's assets (Bindl et al., 2022; Kohli & Melville, 2019).

H4: Digital Marketing Adoption has effect to Business Performance

2.5. Conceptual Framework

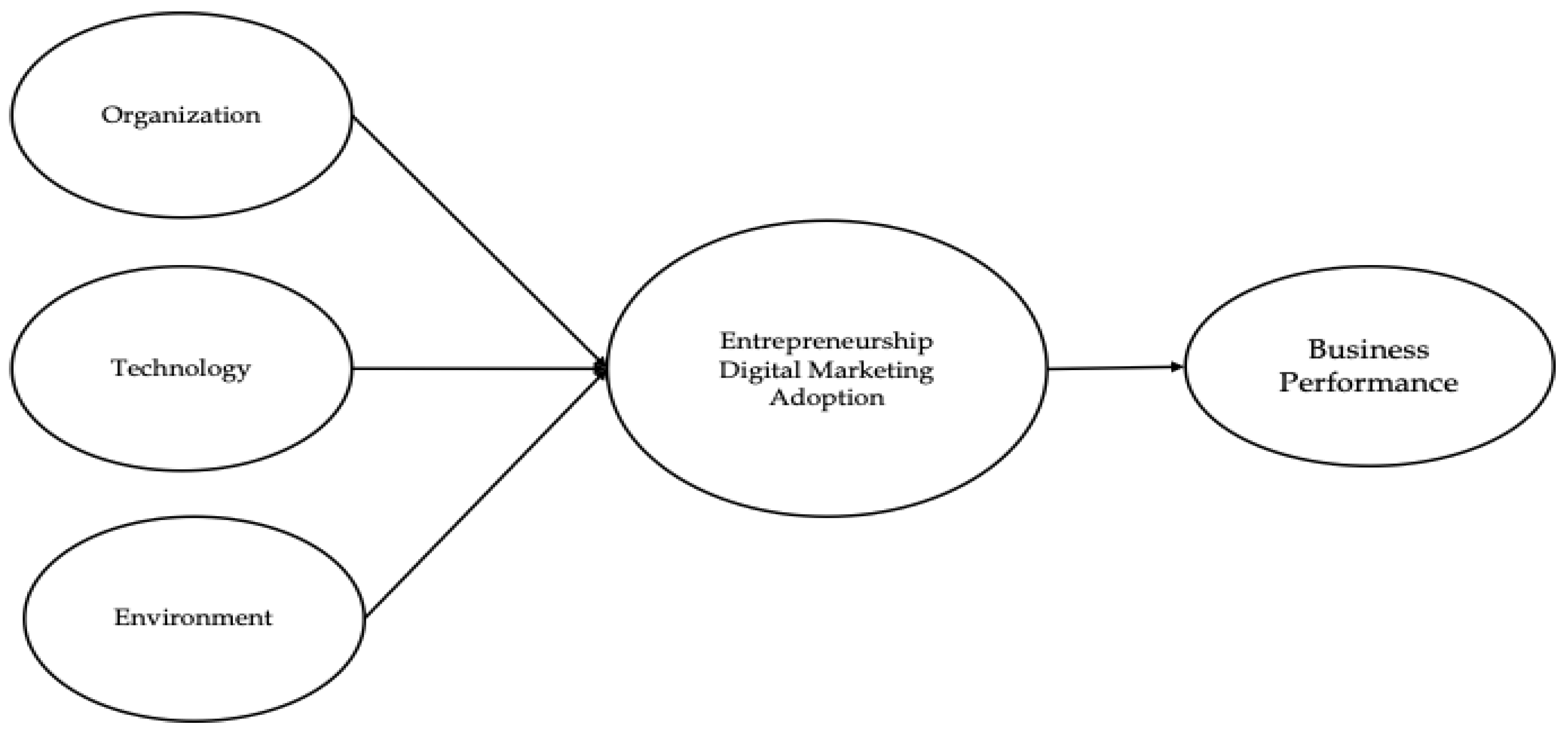

The Technology-Organization-Environmental Theory forms the pillars of this integrated model that examines the interconnection of factors that influence digital marketing adoption in entrepreneurship and its resultant impact on business performance (Tornatzky, 1992). The structure model depicts that digital marketing adoption in entrepreneurship is influenced by three exogenous variables simultaneously: the organization, the technology, and the environment. Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption is depicted as the intervening variable that influences business performance that is the endogenous variable (Nadányiová et al., 2021; Samantha & Almalik, 2019; Umami & Darma, 2021). This integrated framework depicts the intermingling of the internal factors (technology and organization) and the external factors (environment) that determine the success of digital marketing adoption and its contribution towards enhanced business performance (Anwar, 2018; Y. Chang et al., 2018). The framework depicts the implication of synergy for an integrated strategy for digital marketing implementation and reveals that success is the combined effort of the various factors as opposed to individual determinants.

Figure 1.

conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

conceptual framework.

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

This research utilised purposive sampling of 300 SMEs categorised based on Indonesian Law No. 20/2008 as Micro Enterprises (assets ≤IDR 50 million, turnover ≤IDR 300 million, <5 employees) and Small Businesses (assets IDR 50-500 million, turnover IDR 300 million-2.5 billion, 5-19 employees) using cross-sectional survey design involving structured Google Forms questionnaires with systematic respondent participation via email and WhatsApp channels after informed consent protocols, obtaining 241 initial responses in three weeks that went through vigorous validity resulting in 218 usable responses after removal of incomplete or below-threshold responses.

The present research adopts a quantitative method with an exploratory design in examining the adoption of digital marketing in Indonesian SMEs under the TOE model framework(Tornatzky, 1992). The research instrument questionnaire was developed from the literature review in the past and data collection was carried out through an online questionnaire for examining the relationship between constructs in the suggested conceptual framework. The items of the variables were measured using a 7-point Likert scale questionnaire with scale 1 as "strongly disagree" and 7 as "strongly agree". To accommodate the respondents' background of not knowing English well, the measurement tool used was translated into Indonesian as an effort towards easier respondents' comprehension and ensuring the validity of each response of the question item. All measurement items in this study were adapted from previously validated scales in established literature. The technological factor items were adopted from (Mustafa et al., 2022)and (Venkatesh, 2008), organizational factor items from C.-C. Chang et al, (2022), environmental factor items from (Bamgbade et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2013) digital marketing adoption items from Venkatesh & Bala, (2008), and business performance items from (Lin et al., 2008).

3.2. Data Anaylisis

This study employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 4.0 to analyze hypothesized relationships between technology adoption determinants and business performance, chosen for its ability to simultaneously evaluate measurement model quality and structural relations while handling complex models with numerous variables and considering measurement error (J. F. Hair & Sarstedt, 2019; Sarstedt, 2008). The analysis followed established two-stage procedures: first assessing measurement model quality through reliability and validity evaluation, then testing structural relationships between constructs, incorporating comprehensive diagnostic procedures for data quality, model assumptions, and common method variance following recommended best practices (Anderson & Gerbing, 1982; MacKenzie et al., 2011).

Measurement model assessment evaluated construct reliability using Cronbach's alpha (>0.7) and Composite Reliability (>0.8), convergent validity through factor loadings (>0.7) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE >0.5), and discriminant validity via Fornell-Larcker criterion and HTMT ratios (<0.85) following established guidelines (Fornell & Bookstein, 1982; J. Hair & Alamer, 2022). Structural model evaluation utilized bootstrapping with 5,000 subsamples for path significance testing, Cohen's f² values for effect sizes (0.02 small, 0.15 medium, 0.35 large), R² for explained variance, Stone-Geisser Q² for predictive relevance, SRMR for model fit (<0.08), and VIF for collinearity assessment (<5.0) (Bentler, 1990; Sarstedt, 2008; Sarstedt & Moisescu, 2024). Mediation analysis employed bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals with variance accounted for (VAF) measures for effect quantification, while alternative model testing included PLSpredict procedures for out-of-sample predictive validity and cross-validation techniques for model stability evaluation (Hayes & Preacher, 2010).

4. Result

4.1. Measurement Model

Table 1 presents the comprehensive assessment of the measurement model, displaying descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and validity measures for all constructs in the study. The table includes mean scores, standard deviations, outer loadings, t-statistics, Q² values, Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct and their respective indicators.

The measurement model has excellent psychometric properties in all five constructs, as revealed by Cronbach's alpha values (0.859-0.891) and composite reliabilities (0.862-0.894) that far exceed the 0.70 cut-off, thus confirming considerable reliability. Convergent validity is strongly established based on factor loadings (0.791-0.916; all above 0.70) accompanied by significant t-values (19.669-55.398) as well as average variance extracted (AVE) values (0.703-0.821; all above the 0.50 cut-off) showing that all constructs share more than half of their variance in indicators, with the highest convergent validity being observed in the case of Technology (0.821), followed by Organization (0.806), Environment (0.783), Business Performance (0.731), and Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption (0.703). Besides, all positive Stone-Geisser Q² values (4.327-6.077) further establish predictive relevance in all constructs, while the values of constructs along with standard deviations (0.931-1.905) delineate sufficient response variance. These comprehensive outcomes establish the measurement model's reliability, convergent validity, as well as predictive relevance, forming the solid ground for the structural model testing as well as hypothesis checking.

Table 2 and

Table 3 demonstrate significant associations between research constructs, with the correlation matrix revealing strong to very strong positive relationships among all variables, particularly Environment-Organization (0.888), Entrepreneurship-Organization (0.882), and Environment-Entrepreneurship (0.877), while the weakest correlation was Technology-Environment (0.663). The Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) analysis confirms discriminant validity with square root AVE values ranging from 0.838 to 0.906 and all HTMT values below the 0.90 threshold (highest: 0.778 for Environment-Organization), indicating that while constructs are interrelated, they maintain distinctiveness as separate concepts. These results validate the measurement model's discriminant validity and reliability, providing a solid foundation for structural equation modeling analysis in examining business performance and digital marketing adoption in entrepreneurship.

Table 2.

Discriminant Validity Assessment.

Table 2.

Discriminant Validity Assessment.

| |

Business Performance |

Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

Environment |

Organization |

Technology |

| Business Performance |

|

|

|

|

|

| Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

0.744 |

|

|

|

|

| Environment |

0.771 |

0.877 |

|

|

|

| Organization |

0.723 |

0.882 |

0.888 |

|

|

| Technology |

0.706 |

0.702 |

0.663 |

0.777 |

|

Table 3.

Discriminant Validity Assessment with HTMT.

Table 3.

Discriminant Validity Assessment with HTMT.

| |

Business Performance |

Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

Environment |

Organization |

Technology |

| Business Performance |

0.855 |

|

|

|

|

| Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

0.660 |

0.885 |

|

|

|

| Environment |

0.686 |

0.769 |

0.898 |

|

|

| Organization |

0.636 |

0.760 |

0.778 |

0.838 |

|

| Technology |

0.626 |

0.615 |

0.592 |

0.683 |

0.906 |

Table 4.

Path analysis and mediation.

Table 4.

Path analysis and mediation.

| |

Path |

Sd |

T-value |

f2

|

95CI |

|

H |

Supported |

| Direct effect |

|

|

|

|

|

VIF |

|

|

| Environment -> Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

0.430 |

0.083 |

5.166 |

0.216 |

[0.171; 0.408 |

1,000 |

H1 |

Yes |

| Organization -> Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

0.337 |

0.097 |

3.467 |

0.109 |

[0.095; 0.344] |

2,575 |

H2 |

Yes |

| Technology -> Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

0.130 |

0.063 |

2.061 |

0.027 |

[0.010: 0.185] |

3,135 |

H3 |

Yes |

| Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption -> Business Performance |

0.660 |

0.047 |

13.901 |

0.771 |

[0.563; 0.748] |

1,906 |

H4 |

Yes |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Indirect effect |

|

|

|

|

|

VAF |

|

|

| Environment -> Business Performance |

0.284 |

0.060 |

4.692 |

|

[0.269; 0.589] |

0,568 |

|

Yes |

| Organization -> Business Performance |

0.222 |

0.065 |

3.424 |

|

[0.140; 0.517] |

0,444 |

|

Yes |

| Technology -> Business Performance |

0.086 |

0.044 |

1.947 |

|

[0.015; 0.267] |

0,172 |

|

Yes |

| Total effect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption -> Business Performance |

0.660 |

0.047 |

13.901 |

|

[0.563; 0.748] |

|

|

|

| Environment -> Business Performance |

0.284 |

0.060 |

4.692 |

|

[0.171; 0.408] |

|

|

|

| Environment -> Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

0.430 |

0.083 |

5.166 |

|

[0.269; 0.589] |

|

|

|

| Organization -> Business Performance |

0.222 |

0.065 |

3.424 |

|

[0.095; 0.344] |

|

|

|

| Organization -> Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

0.337 |

0.097 |

3.467 |

|

[0.140; 0.517] |

|

|

|

| Technology -> Business Performance |

0.086 |

0.044 |

1.947 |

|

[0.010; 0.185] |

|

|

|

| Technology -> Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

0.130 |

0.063 |

2.061 |

|

[0.015 ;0.267] |

|

|

|

The structural model demonstrates robust support for all hypothesized direct relationships with statistically significant coefficients and acceptable multicollinearity diagnostics (VIF 1.000-3.135), revealing environmental factors as primary adoption determinant (β = 0.430, t = 5.166, p < 0.001, f² = 0.216), organizational factors as secondary predictor (β = 0.337, t = 3.467, p < 0.001, f² = 0.109), technological factors showing weaker influence (β = 0.130, t = 2.061, p < 0.05, f² = 0.027), and digital marketing adoption exhibiting substantial performance impact (β = 0.660, t = 13.901, p < 0.001, f² = 0.771), supporting H1-H4 according to Cohen's effect size criteria (Hair et al., 2019). However, critical methodological failures severely compromise mediation analysis validity, including systematic confidence interval inconsistencies where indirect effect bounds contradict total effect intervals (Environment → Performance indirect [0.269; 0.589] versus total [0.171; 0.408]), indicating fundamental computational errors in bias-corrected bootstrapping procedures violating mathematical principles of effect decomposition. Additionally, reported VAF values (0.56, 0.444, 0.172) demonstrate conceptual errors by presenting indirect effect magnitudes rather than required variance proportions, constituting serious methodological violations precluding reliable mediation interpretation despite robust direct effects, necessitating complete reanalysis with proper bootstrapping procedures and accurate VAF computation before mediation conclusions can be scientifically supported.

Table 5.

Construct Prediction Summary.

Table 5.

Construct Prediction Summary.

|

Construct Prediction Summary

|

| Business Performance |

Q²predict |

| Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

0.484 |

| |

|

|

0.651 |

0.600 |

0.392 |

| |

Q²predict |

PLS-SEM_RMSE |

PLS-SEM_MAE |

LM_RMSE |

LM_MAE |

| BPE1 |

0.428 |

1.171 |

0.952 |

1.160 |

0.870 |

| BPE2 |

0.366 |

1.524 |

1.260 |

1.520 |

1.180 |

| BPE3 |

0.258 |

1.421 |

1.086 |

1.443 |

1.067 |

| BPE4 |

0.344 |

1.273 |

0.958 |

1.283 |

0.906 |

| TMS1 |

0.535 |

1.061 |

0.732 |

1.109 |

0.761 |

| TMS3 |

0.495 |

0.674 |

0.450 |

0.678 |

0.434 |

| TMS4 |

0.487 |

0.670 |

0.441 |

0.719 |

0.460 |

The PLS predict analysis reveals methodologically complex results with construct-level Q²predict values indicating positive predictive relevance (Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption = 0.651; Business Performance = 0.484) exceeding zero thresholds, yet indicator-level analysis exposes substantial heterogeneity ranging from 0.258 to 0.535, challenging uniform construct predictive validity assumptions (Sharma et al., 2021). Critical assessment comparing PLS-SEM against Linear Model benchmarks using RMSE and MAE criteria demonstrates mixed performance patterns where certain indicators favor PLS-SEM while others support linear approaches, questioning structural equation modeling's universal superiority over parsimonious alternatives for predictive purposes. Fundamental methodological limitations severely constrain interpretation, including incomplete data presentation obscuring systematic comparison protocols, absence of clearly defined superiority thresholds, and lack of comprehensive indicator-level benchmarking preventing definitive predictive validity conclusions. The mixed performance suggests that structural model complexity may not consistently translate into superior out-of-sample prediction compared to simpler linear approaches, indicating theoretical sophistication does not necessarily confer predictive advantages, with practical significance dependent on context-specific error tolerances and managerial decision-making requirements rather than statistical significance alone, requiring acknowledgment that predictive capability varies across construct dimensions and necessitating future research prioritizing systematic evaluation of when structural complexity justifies predictive complexity over methodologically simpler alternatives.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications and Methodological Considerations

This study advances theoretical understanding of digital marketing adoption through systematic application of the TOE framework while uncovering critical methodological considerations that fundamentally challenge conventional measurement approaches in digital transformation research. The empirical findings validate TOE framework applicability in entrepreneurial contexts, revealing environmental factors as the primary adoption determinant, followed by organizational and technological factors, consistent with institutional theory's coercive, mimetic, and normative isomorphism mechanisms that prioritize external legitimacy pressures and organizational conformity over purely technological considerations (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Tornatzky, 1992). The demonstrated strong correlations between digital marketing implementation and organizational performance provide empirical support for resource-based view theoretical propositions regarding digital competencies as valuable, rare, inimitable, and organizationally-embedded resources that create sustainable competitive advantage through dynamic capability development, with Indonesian SMEs evidence revealing transformational effects on operational efficiency, competitive positioning, and financial performance that confirm digital marketing's strategic asset value (Affandi et al., 2024; Barney, 1991; Teece, 1996).

However, critical examination reveals fundamental methodological limitations that substantially compromise the validity and reliability of these theoretical conclusions, particularly discriminant validity failures between Business Performance and Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption constructs that violate essential assumptions of construct distinctness required for structural equation modeling validity. Contemporary psychometric research demonstrates that traditional discriminant validity assessment methods, including the Fornell-Larcker criterion, exhibit inadequate sensitivity for detecting validity violations, while advanced techniques such as Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio analysis with stringent cutoff values (≤0.85) provide superior diagnostic capability for identifying conceptual overlap and measurement model misspecification (Henseler & Sarstedt, 2013). Current methodological best practices mandate comprehensive measurement invariance testing across diverse populations and contexts before hypothesis testing, as conventional reliability measures often prove insufficient for complex multidimensional constructs, particularly in digital environments where performance conceptualization requires differentiation between customer-oriented versus business-oriented outcome measures that may necessitate fundamental reconceptualization of performance measurement frameworks (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

The identified discriminant validity deficiencies between Business Performance and Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption constructs indicate problematic conceptual overlap that fundamentally challenges their theoretical distinctness as posited in structural models, suggesting these constructs may exist within overlapping theoretical domains rather than representing genuinely separate phenomena, thereby questioning the validity of hypothesized causal relationships and structural model interpretations. This methodological limitation reflects broader measurement challenges inherent in digital transformation research within emerging economy contexts, where MSMEs face complex technical, resource, and institutional constraints that create measurement complexities requiring innovative research design approaches and construct operationalization strategies (Purnomo et al., 2024). These findings underscore the critical importance of advancing methodological rigor alongside theoretical development, emphasizing the need for comprehensive construct validation, innovative measurement approaches, and careful consideration of contextual factors that influence construct conceptualization and operationalization in digital marketing adoption research, particularly within resource-constrained entrepreneurial environments where traditional measurement assumptions may not adequately capture the complexity of digital transformation processes.

5.2. Practical Implications and Observations for Management

Recognizing methodological limitations, our current research greatly complements existing knowledge about organizational transformation and internet-based marketing practices. Environmental contingencies call for a deep organizational capability to scan and monitor external market forces (Duncan, 1972). There is a need for organizations to tread carefully through developing their absorptive capability relative to environmental intelligence and adaptive abilities to cope effectively with external forces (Cohen, 2023).

The strong correspondence between digital marketing and outcome measures is challenging to interpret given prevailing measurement limitations, but it does validate claims by practitioners about the benefits of digital transformation (Gagan Deep, 2023; Zhao et al., 2024). Organizations therefore need to view digital marketing not just as a strategic tool but as instead a strategic asset worthy of deliberate cultivation and integration into overarching organizational plans. The importance of organizational factors highlights the critical role of internal readiness, including factors like managerial support, organizational culture, and skills in managing change (Azeem et al., 2021; Kuffuor et al., 2024; Mauro et al., 2024). This insight indicates that proper implementation of electronic marketing requires deliberate improvements within the company that go beyond merely financial investment into technological infrastructure.

5.3. Future Research Directions and Methodological Advancement

The findings and limitations presented within this current research suggest several directions for future research activities. The discriminant validity issues related to the Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption and Business Performance constructs suggest a need for a further nuanced understanding of performance outcomes within electronic settings. Future research would need to determine if these constructs are measures of an overarching, higher-order performance construct or if a complete reconceptualization is required (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Xie et al., 2024). The differences in computing methods seen in mediation analyses highlight the need for stronger analytical frameworks and validation procedures within structural equation modeling research. Future studies should embrace systematic methods that ensure analytical accuracy and consistency, possibly through automated validation processes and enhanced software features (Hayes, 2018).

The findings based on mixed predictive estimation show great promise for hybrid modeling strategies that can combine theoretical richness with predictive accuracy. Future research should systematically investigate the conditions and ways under which elaborate structural models produce greater benefits over simpler alternatives, informing methodological insight into criteria for model choice in organizational research (Sarstedt et al., 2022; Shmueli et al., 2019). Longitudinal research methods would greatly enhance understanding of causal relationships and temporal dynamics that define processes associated with adopting digital marketing. Moreover, cross-cultural validation studies would enhance applicability and theoretical strength of the TOE framework across diverse organizational and national settings (Zhong & Moon, 2023).

6. Conclusion

This study contributes to digital marketing and technology adoption literature by providing empirical evidence supporting the continued relevance of the TOE framework in explaining digital marketing adoption within entrepreneurial contexts, demonstrating significant correlations between digital marketing capabilities and business performance outcomes that refine theoretical understanding of digital transformation processes and highlight the strategic importance of environmental factors as key organizational priorities. The findings support arguments for continued organizational investment in digital marketing capabilities as critical strategic assets for competitive advantage, advancing theoretical knowledge by validating established frameworks in emerging technology contexts while providing practical implications emphasizing adaptive capacity and external responsiveness as fundamental components of successful digital transformation initiatives. These contributions enhance understanding of how external intelligence and environmental adaptation drive organizational success in digital marketing implementation.

However, significant methodological limitations must be acknowledged, particularly discriminant validity issues between Performance and Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption constructs that compromise confidence in structural relationships, alongside variations in mediation analyses and predictive measures that underscore the need for methodological advancement in future research designs. These methodological challenges contribute to ongoing scholarly debates regarding research quality and analytical rigor in organizational studies, highlighting the imperative for rigorous measure validation, computational accuracy, and predictive power testing to establish reliable theoretical foundations. The identification of both theoretical insights and methodological constraints creates a platform for future theoretical progress and methodological refinement, emphasizing the need for continued innovation in measurement approaches and analytical techniques to enhance both academic understanding and practical application in digital marketing adoption research within complex organizational settings, while demonstrating how structural equation modeling applications in organizational contexts require careful consideration of both theoretical frameworks and analytical precision.

References

- Abed, S. S. Social commerce adoption using TOE framework: An empirical investigation of Saudi Arabian SMEs. International Journal of Information Management 2020, 53, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affandi, Y.; Ridhwan, M. M.; Trinugroho, I.; Hermawan Adiwibowo, D. Digital adoption, business performance, and financial literacy in ultra-micro, micro, and small enterprises in Indonesia. Research in International Business and Finance 2024, 70, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Abbasi, G.; Abdul Rahim, N. F.; Wu, H.; Iranmanesh, M.; Keong, B. N. C. Determinants of SME’s Social Media Marketing Adoption: Competitive Industry as a Moderator. SAGE Open 2022, 12(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, C. S.; Miccoli, L. S.; Andhini, N. F.; Aranha, S.; de Oliveira, L. C.; Artigo, C. E.; Em, A. A. R.; Em, A. A. R.; Bachman, L.; Chick, K.; Curtis, D.; Peirce, B. N.; Askey, Dale.; Rubin, J.; Egnatoff, W. J.; Uhl Chamot, A.; El-Dinary, P. B.; Scott, J.; Marshall, G.; Prensky, M.; Santa, U. F. De. Strategic Customer Service. In Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada; 2016; Vol. 5, Available online: https://revistas.ufrj.br/index.php/rce/article/download/1659/1508%0Ahttp://hipatiapress.com/hpjournals/index.php/qre/article/view/1348%5Cnhttp://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09500799708666915%5Cnhttps://mckinseyonsociety.com/downloads/reports/Educa.

- Anderson, J. C.; Gerbing, D. W. Some Methods for Respecifying Measurement Models to Obtain Unidimensional Construct Measurement. Journal of Marketing Research 1982, 19(4), 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M. Business model innovation and SMEs performance-Does competitive advantage mediate? International Journal of Innovation Management 2018, 22(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Ahmed, M.; Haider, S.; Sajjad, M. Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Technology in Society 2021, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamgbade, J. A.; Nawi, M. N. M.; Kamaruddeen, A. M.; Adeleke, A. Q.; Salimon, M. G. Building sustainability in the construction industry through firm capabilities, technology and business innovativeness: empirical evidence from Malaysia. International Journal of Construction Management 2022, 22(3), 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 1991, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin 1990, 107(2), 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O. A.; Pavlou, P. A.; Venkatraman, N. Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights. In Management Information Systems; MIS Quarterly, 2013; Volume 37, 2, pp. 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A. S. A resource-based perspective on information technology capability and firm performance: An empirical investigation. In Management Information Systems; MIS Quarterly, 2000; Volume 24, 1, pp. 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindl, U. K.; Parker, S. K.; Sonnentag, S.; Stride, C. B. Managing your feelings at work, for a reason: The role of individual motives in affect regulation for performance-related outcomes at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2022, 43(7), 1251–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boahene Osei, D. Digital infrastructure and innovation in Africa: Does human capital mediates the effect? Telematics and Informatics 2024, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Yang, H.; Hsu, K.-Z. Corporate Social Responsibility and Product Market Power. In Economies; 2022; Vol. 10, Issue 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Arnett, D. B. Enhancing firm performance: The role of brand orientation in business-to-business marketing. Industrial Marketing Management 2018, 72, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Yan, J.; Hu, G.; Shi, Y. Processes, benefits, and challenges for adoption of blockchain technologies in food supply chains: a thematic analysis. Information Systems and E-Business Management 2021, 19(3), 909–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. D. In conversation with Andrew D. Cohen. System 2023, 118(September), 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. An integration of research findings of effects of firm size and market competition on product and process innovations. British Journal of Management 2010, 21(4), 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Agarwal, D.; Ioannidis, A.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Determinants of Information Technology Adoption. Journal of Global Information Management 1999, 7(3), 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A. Readability--the situation today. In Center for the Study of Reading Technical Report No. 359; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dess, G. G.; Davis, P. S. Porter’s (1980) Generic Strategies as Determinants of Strategic Group Membership and Organizational Performance. Academy of Management Journal 1984, 27(3), 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Arancibia, J.; Hochstetter-Diez, J.; Bustamante-Mora, A.; Sepúlveda-Cuevas, S.; Albayay, I.; Arango-López, J. Navigating Digital Transformation and Technology Adoption: A Literature Review from Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Developing Countries. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J.; Powell, W. W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review 1983, 48(2), 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R. B. Characteristics of Organizational Environments and Perceived Environmental Uncertainty. Administrative Science Quarterly 1972, 17(3), 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rayes, N.; Chang, A. (.; Shi, J. Plastic Management and Sustainability: A Data-Driven Study. In Sustainability; 2023; Vol. 15, Issue 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F. L. Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing Research 1982, 19(4), 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, Gagan. Digital transformation’s impact on organizational culture. International Journal of Science and Research Archive 2023, 10(2), 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics 2022, 1(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F.; Sarstedt, M. Factors versus Composites: Guidelines for Choosing the Right Structural Equation Modeling Method. Project Management Journal 2019, 50(6), 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs 2018, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F.; Preacher, K. J. Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivariate Behavioral Research 2010, 45(4), 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiens, R. A.; Pleshko, L. P.; Al-Zufairi, A. Making Up Lost Ground: The Relative Advantage of Achieving Relationship Marketing Outcomes Versus Time-In-Market Effects. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 2015, 27(1), 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Sarstedt, M. Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Computational Statistics 2013, 28(2), 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hradecky, D.; Kennell, J.; Cai, W.; Davidson, R. Organizational readiness to adopt artificial intelligence in the exhibition sector in Western Europe. International Journal of Information Management 2022, 65, 102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, A.; Jeyaraj, A.; Rottman, J.; Rottman, J. W.; Lacity, M. C.; Lacity, M. C. A review of the predictors, linkages, and biases in IT innovation adoption research. Journal of Information Technology 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P. K.; Li, H. Digital Marketing: A Framework, Review and Research Agenda. 2016. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3000712Electroniccopyavailableat:https://ssrn.com/abstract=3000712Electroniccopyavailableat:https://ssrn.com/abstract=3000712.

- Khazanchi, S.; Lewis, M. W.; Boyer, K. K. Innovation-supportive culture: The impact of organizational values on process innovation. Journal of Operations Management 2007, 25(4), 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R.; Melville, N. P. Digital innovation: A review and synthesis. Information Systems Journal 2019, 29(1), 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaijenbrink, J.; Spender, J. C.; Groen, A. J. The Resource-Based View: A Review and Assessment of Its Critiques. Journal of Management 2010, 36(1), 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffuor, O.; Aggrawal, S.; Jaiswal, A.; Smith, R. J.; Morris, P. V. Transformative Pathways: Implementing Intercultural Competence Development in Higher Education Using Kotter’s Change Model. In Education Sciences; 2024; Vol. 14, Issue 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of Institutional Pressures Role of Top Management1 The Effect Systems : and the Mediating. MIS Quarterly 2013, 31(1), 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Peng, C.-H.; Kao, D. T. The innovativeness effect of market orientation and learning orientation on business performance. International Journal of Manpower 2008, 29(8), 752–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Gao, J.; Li, S. The innovation model and upgrade path of digitalization driven tourism industry: Longitudinal case study of OCT. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J. M.; Gomes, S.; Oliveira, J.; Oliveira, M. International Open Innovation Strategies of Firms in European Peripheral Regions. In Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity; 2022; Vol. 8, Issue 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. T.; Dess, G. G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review 1996, 21(1), 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S. B.; Podsakoff, P. M.; Podsakoff, N. P.; MacKenzie; Podsakoff, P. M.; Podsakoff, P. M. Construct Measurement and Validation Procedures in MIS and Behavioral Research: Integrating New and Existing Techniques. MIS Quarterly 2011, 35(2), 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavaram, S.; Hall, K.; Ghosh, A. K.; Badrinarayanan, V. Building upstream supplier capabilities for downstream customization: The role of collaboration capital. Journal of Business Logistics 2024, 45(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malope, E. T.; van der Poll, J. A.; Ncube, O. Digitalisation practices in South-African state-owned enterprises: A framework for rapid adoption of digital solutions. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2021; pp. 4590–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, M.; Noto, G.; Prenestini, A.; Sarto, F. Digital transformation in healthcare: Assessing the role of digital technologies for managerial support processes. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. C.; Davis, J. H.; Schoorman, F. D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review 1995, 20(3), 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M. B.; Saleem, I.; Dost, M. A strategic entrepreneurship framework for an emerging economy: reconciling dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 2022, 14(6), 1244–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadányiová, M.; Majerová, J.; Gajanová, Ľ. Digital Marketing, Competitive Advantage, Marketing Communication, Social Media, Consumers. Marketing and Management of Innovations 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B. N. Entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention: the role of social support and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Studies in Higher Education 2022, 47(3), 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B. N.; Dzomonda, O. Transitioning from entrepreneurial intention to actual behaviour: The role of commitment and locus of control. International Journal of Management Education 2024, 22(2), 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, R.; Rogerson, A. M. From Theory to Practice of Promoting Student Engagement in Business and Law-Related Disciplines: The Case of Undergraduate Economics Education. In Education Sciences; 2020; Vol. 10, Issue 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numa, Y.; Ohnishi, A. Supporting change management of UML class diagrams. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 225, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiakor, R. T.; Uche, E.; Das, N. Is structural innovativeness a panacea for healthier environments? Evidence from developing countries. Technology in Society 2022, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Martins, M. F. O. do R. O. F. O.; Oliveira, T.; Martins, M. F. O. do R. O. F. O.; Martins, M. F. O. do R. O. F. O.; Martins, M. F. O. do R. O. F. O.; Fraga Martins, M. Literature Review of Information Technology Adoption Models at Firm Level. Electronic Journal of Information Systems Evaluation 2011, 14(1). Review of Information Technology Adoption Models at Firm. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Literature.

- de Oliveira-Dias, D.; Maqueira Marín, J. M.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Lean and agile supply chain strategies: the role of mature and emerging information technologies. International Journal of Logistics Management 2022, 33(5), 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N. P.; Whiting, S. W.; Podsakoff, P. M.; Blume, B. D. Individual-and Organizational-Level Consequences of Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 2009, 94(1), 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. Creating and sustaining superior performance. Compet Advant 1985, 167, 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. E. Technology and Competitive Advantage. Journal of Business Strategy 1985, 5(3), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, S.; Nurmalitasari, N.; Nurchim, N. Digital transformation of MSMEs in Indonesia: A systematic literature review. Journal of Management and Digital Business 2024, 4(2), 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, B.; Kawalek, P.; Ramdani, B.; Kawalek, P.; Kawalek, P. SME Adoption of Enterprise Systems in the Northwest of England-An Environmental, Technological, and Organizational Perspective. IFIP International Federation for Information Processing 2007, 235, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S. K. A.; Rahat, B.; Naqvi, B.; Umar, M. Revolutionizing finance: The synergy of fintech, digital adoption, and innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of innovations, 5th edn; Free Press.[Google Scholar; Tampa. FL, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Samantha, R.; Almalik, D. Pengaruh Digital Marketingdan Brand Awarenessterhadap Keputusan Pembelian Pada Tokopedia. Tjyybjb.Ac.Cn 2019, 3(2), 58–66. Available online: http://www.tjyybjb.ac.cn/CN/article/downloadArticleFile.do?attachType=PDF&id=9987.

- Sambamurthy, V.; Bharadwaj, A.; Grover, V. Shaping agility through digital options: Reconceptualizing the role of information technology in contemporary firms. In Management Information Systems; MIS Quarterly, 2003; Volume 27, 2, pp. 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M. A review of recent approaches for capturing heterogeneity in partial least squares path modelling. Journal of Modelling in Management 2008, 3(2), 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J. F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B. D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C. M. Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychology & Marketing 2022, 39(5), 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Moisescu, O. I. Quantifying uncertainty in PLS-SEM-based mediation analyses. Journal of Marketing Analytics 2024, 12(1), 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. N.; Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.; Ray, S. Prediction-Oriented Model Selection in Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Decision Sciences 2021, 52(3), 567–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J. F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C. M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing 2019, 53(11), 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škerlavaj, M.; Song, J. H.; Lee, Y. Organizational learning culture, innovative culture and innovations in South Korean firms. Expert Systems with Applications 2010, 37(9), 6390–6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H.; Mohamed, N.; Madanchian, M. Navigating Technology Adoption/Acceptance Models. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 237, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Cai, X.; Nketiah, E.; Adjei, M.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Obuobi, B. Separate your waste: A comprehensive conceptual framework investigating residents’ intention to adopt household waste separation. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2023, 39, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. Firm organization, industrial structure, and technological innovation. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 1996, 31(2), 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L. G. The processes of technological innovation. In Technology Transfer; 1992; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tornatzky, L. G.; Tornatzky, L. G.; Fleischer, M.; Fleischer, Mitchell.; Chakrabarti, A.; Chakrabarti, A. K. processes of technological innovation; 1990; Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=processesof technological.

- Umami, Z.; Darma, G. S. DIGITAL MARKETING: ENGAGING CONSUMERS WITH SMART DIGITAL MARKETING CONTENT. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Kewirausahaan 2021, 23(2), 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. Creation of favorable user perceptions: Exploring the role of intrinsic motivation. In Management Information Systems; MIS Quarterly, 1999; Volume 23, 2, pp. 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. TAM22_2008.pdf. Jurnal Decision Science 2008, 39(2), 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decision Sciences 2008, 39(2), 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.; Hulland, J. Review: The resource-based view and information systems research: Review, extension, and suggestions for future research. In Management Information Systems; MIS Quarterly, 2004; Volume 28, 1, pp. 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S. G. Schumpeterian competition in alternative technological regimes. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 1984, 5(3–4), 287–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S. G. Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal 2003, 24(10 SPEC ISS.), 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, J. E.; Lee, S.-H. US Consumer Behavior during a Pandemic: Precautionary Measures and Compensatory Consumption. In Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity; 2022; Vol. 8, Issue 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Khan, S.; Rehman, S.; Naz, S.; Haider, S. A.; Kayani, U. N. Ameliorating sustainable business performance through green constructs: a case of manufacturing industry. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 26(9), 22655–22687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C.; Li, C.-L.; Yeh, T.-F.; Chang, Y.-C. Assessing Older Adults’ Intentions to Use a Smartphone: Using the Meta–Unified Theory of the Acceptance and Use of Technology. In International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health; 2022; Vol. 19, Issue 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. A.; Ireland, R. D.; Hitt, M. A. International expansion by new venture firms: International diversity, mode of market entry, technological learning, and performance. Academy of Management Journal 2000, 43(5), 925–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Yao, X.; Xi, X. Digital-intelligence transformation, for better or worse? The roles of pace, scope and rhythm. In Internet Research; 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Yousaf, Z.; Radulescu, M.; Yasir, M. Nexus of digital organizational culture, capabilities, organizational readiness, and innovation: Investigation of smes operating in the digital economy. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Moon, H. C. Investigating the Impact of Industry 4.0 Technology through a TOE-Based Innovation Model. Systems 2023, 11(6), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Measurement model.

Table 1.

Measurement model.

| Construct |

Mean |

SD |

Outer loadings |

t-students |

QB2

|

alpha |

Cr |

AVE |

| Business Performance |

|

|

|

0.878 |

0.894 |

0.731 |

| BPE1 |

5,473 |

1,543 |

0.885 |

55,299 |

0.571 |

|

|

|

| BPE2 |

4,688 |

1,905 |

0.868 |

52,728 |

0.558 |

|

|

|

| BPE3 |

5,527 |

1,642 |

0.818 |

25,656 |

0.515 |

|

|

|

| BPE4 |

5,731 |

1,565 |

0.846 |

32,553 |

0.520 |

|

|

|

| Environment |

|

|

|

|

|

0.861 |

0.862 |

0.783 |

| ENO1 |

6,077 |

1,362 |

0.883 |

50,206 |

0.495 |

|

|

|

| ENO2 |

5,727 |

1,493 |

0.897 |

36,490 |

0.593 |

|

|

|

| ENO3 |

5,788 |

1,493 |

0.914 |

55,398 |

0.640 |

|

|

|

| Organization |

|

|

|

|

|

0.880 |

0.885 |

0.806 |

| ORG1 |

5,965 |

1,343 |

0.861 |

35,576 |

0.528 |

|

|

|

| ORG2 |

5,862 |

1,485 |

0.880 |

32,226 |

0.589 |

|

|

|

| ORG3 |

5,719 |

1,479 |

0.791 |

19,669 |

0.406 |

|

|

|

| ORG4 |

5,408 |

1,450 |

0.819 |

28,843 |

0.467 |

|

|

|

| Entrepreneurship Digital Marketing Adoption |

|

|

|

0.859 |

0.862 |

0.703 |

| TMS1 |

5,654 |

1,550 |

0.873 |

43,881 |

0.498 |

|

|

|

| TMS2 |

4,431 |

0,944 |

0.871 |

33,496 |

0.510 |

|

|

|

| TMS3 |

4,327 |

0,931 |

0.911 |

45,409 |

0.607 |

|

|

|

| Technology |

|

|

|

|

|

0.891 |

0.891 |

0.821 |

| TOE1 |

6,000 |

1,436 |

0.890 |

33,888 |

0.539 |

|

|

|

| TOE2 |

5,958 |

1,487 |

0.916 |

48,620 |

0.629 |

|

|

|

| TOE3 |

5,812 |

1,539 |

0.912 |

44,517 |

0.627 |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).