1. Introduction

The dynamics surrounding small and medium enterprises (SMEs) continue to be a compelling area of research, particularly in the context of increasingly competitive market environments. SMEs constitute a critical pillar in national economic structures. Ensuring their sustainability in producing innovative products requires strong resource capabilities. Decision-making under pressure and within limited resources is a common challenge for entrepreneurs. Often, they must respond rapidly by developing or modifying business plans to accelerate internal growth [1]. As such, planning and improvisation play a key role in addressing these challenges.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2022), Indonesia’s economy is projected to reach USD 8.89 trillion by 2045, becoming the world’s fourth largest. This projection aligns with the national development agenda known as Indonesia Emas 2045, which aims to empower SMEs to “move up the ladder” while supporting the creation of new employment opportunities. Despite global economic turbulence, the country remains optimistic due to opportunities in export markets. However, SMEs still face persistent internal issues such as limited organisational capacity and constrained access to facilities, both of which affect production performance. These conditions call for strategic interventions from policymakers and scholars to enhance SME resilience—not only through regulatory frameworks but also through evidence-based models that support business sustainability.

The growth of SMEs in West Java Province has been dynamic, with a significant increase recorded in 2022: 667,795 business units across various SME groups. According to Statistics Indonesia (2024), the leather, leather goods, and footwear sector is the fifth largest SME industry in West Java, with 29,739 business units recorded in 2022. Garut Regency stands out as a key contributor in this sector. It is known for its vertically integrated leather industry, encompassing the entire value chain from sheep farming and tanning to the production of finished leather goods. Garut’s leather industry holds historical significance nationally and internationally, having developed since the 1920s. Increasing demand from both domestic and international markets has prompted leather craft entrepreneurs in Garut to adapt more rapidly to meet evolving consumer needs. This suggests that leather SMEs in the region possess entrepreneurial characteristics and strong potential for sustaining competitive advantage.

Preliminary observations were conducted to identify practical challenges aligned with the research variables. In-depth interviews using unstructured instruments revealed that most leather craft SMEs in Garut experienced declining profits over the past five years. This was attributed to falling sales turnover due to the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, rising raw material costs and price competition placed SME owners in a difficult position. Setting competitive prices was constrained by product quality, consumer purchasing power, and external threats. Products in this sector are easily imitated and mass-produced, increasing vulnerability to market pressures. As a counterstrategy, SMEs began targeting niche markets through custom product offerings. Competitors were found to come not only from outside the city but also from international markets.

Over the past decades, Indonesian SMEs have increasingly pursued innovation as a strategic response to market competition. Many have shifted from traditional to digital marketing approaches [2]. This transformation has become a necessity, as business environments are now interconnected through the internet. SMEs that successfully implement digital transformation can seize market opportunities more rapidly and enhance their entrepreneurial capacity. In the leather craft industry of Garut, business owners are required to innovate continuously and maximise the benefits of digital marketing to achieve improved performance and competitive advantage.

Digital marketing has had a profound impact on the business world by leveraging internet connectivity and modern technologies. It has reshaped the flow of communication and information, eliminating geographical barriers. This digitalisation process has facilitated entrepreneurial growth by enabling businesses to operate online. Network effects—defined as value creation driven by increasing users, digital interaction, and feedback—offer significant potential for digital entrepreneurs [5]. Beyond information access, the wide user base of digital platforms can generate powerful network effects. In the leather craft sector, digital information enables business actors to analyse customer needs more precisely. This offers a distinct advantage compared to traditional entrepreneurs who lack access to such tools. As such, digital information and its management are not merely inputs but must be viewed as key enablers of sustainable entrepreneurship In the context of globalised and hypercompetitive markets, strategic resources have become critical determinants of competitive advantage. Firms are expected to build entrepreneurial processes based on valuable, rare, and inimitable internal resources [7,8]. Traditional competitive strategies such as cost leadership, market differentiation, and niche orientation [9] are becoming less relevant due to their replicability. Instead, unique resources and capabilities are seen as crucial for sustaining business advantage over time. This study investigates the effect of digital marketing and entrepreneurial orientation on competitive advantage, mediated by product innovation. The research focuses on leather craft SMEs in Garut Regency as entrepreneurial firms and applies the Resource-Based View (RBV) theory [13], which posits that sustainable competitive advantage stems from effective management of strategic internal resources [13,14,15].

2. Literature Review

The theoretical foundation of this research is grounded in the Resource-Based View (RBV), a widely accepted extension of strategic management theory [14,16,17,18,19]. Several scholars have argued that the core objective of strategic management is to attain competitive advantage [20,21,22,23,24]. This conceptualisation is process-oriented and manifests through various behavioural models across organisational levels, including entrepreneurs acting within firms [25].

2.1. Resource Based View

The RBV is fundamentally concerned with taking entrepreneurial action from a strategic perspective [26]. Competitive actions are viewed as an integration of entrepreneurial efforts and competitive advantage within the RBV framework [27,28,29]. The theoretical foundations of competitive action are derived from economics, sociology, and organisational theory [21,30], aiming to develop business strategies that shape competitive markets. Strategic governance is necessary to exploit firm resources in line with market opportunities—a view consistent with the principles of strategic management [16,17,18,21,28].

RBV focuses primarily on internal firm environments as drivers of competitive advantage, emphasising resource deployment in dynamic contexts. Its early development stemmed from strategic thinking, with an internal focus on firm-specific factors [21]. Foundational work by scholars such as [31,32] shifted academic attention in the 1980s away from industry structure theories (e.g., Structure–Conduct–Performance paradigm and Porter’s Five Forces) toward the firm’s internal configuration of resources and capabilities as key sources of advantage [23].

The origins of RBV are often attributed to the perspective that firm-owned, managed, and utilised resources are more critical than industry structure in determining success [33]. The term “Resource-Based View” was coined by [19], who described firms as bundles of semi-permanently bound assets or resources [34]. Later developments led to the emergence of the “core competence” concept [35], which emphasises strategically critical resources. Scholars such as [13] also assert that internal resources are the primary drivers of competitive advantage.

According to [36,37,38,39,40,41], competitive advantage rooted in firm-specific resources and capabilities tends to be more sustainable than that based solely on product or market positioning. These resources may be tangible (e.g., financial or physical assets) or intangible (e.g., human capital or knowledge). The RBV posits that only resources which are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable can be considered sources of sustainable competitive advantage.

RBV-oriented scholars argue that only strategically valuable and relevant resources should be regarded as sources of competitive edge [13]. Such resources are often referred to as core competencies [13,42], distinctive competencies [43], or strategic infrastructure assets [44,45]. Strategic assets have been defined as “the set of difficult-to-trade and imitate, scarce, appropriable, and specialised resources and capabilities that bestow the firm’s competitive advantage” [46]. These resources underpin a firm’s ability to manipulate internal capabilities for strategic advantage. Core competencies are resources that are distinctive, rare, and valuable, and which competitors cannot easily imitate, substitute, or reproduce [13,42]. In this research, the emphasis lies in identifying how these resources enable competitive success in the context of digitalisation among SMEs.

Resources alone, however, do not directly translate into competitive advantage. Firms must engage in entrepreneurial actions to mobilise these resources effectively [41]. This aligns with findings by [47], which suggest that competitive action, competitive advantage, and performance are extensively examined within strategic management literature [9,13,16,48,49,50]. Competitive actions across categories may have varied impacts on firm performance, particularly when studied as independent variables influencing competitive advantage [51,52,53].

2.2. Research Framework

This study is theoretically driven by two key developments. First, the emergence of digitalisation as a strategic resource among SMEs has become a central theme in research on competitive advantage [39,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. The concept of IT infrastructure as a firm resource in SMEs was introduced by [29] in Journal of Management and remains closely aligned with the Resource-Based Theory of the Firm [33], especially regarding competitive advantage development [27,63,64].

The second impetus stems from the rise of entrepreneurial perspectives in the pursuit of competitive advantage [26]. The presence of entrepreneurial behaviour within organisations is consistent with the view that markets function as platforms for firms to experiment with entrepreneurial actions [25]. Some firms proactively engage to lead the market, while others act as followers and imitators [47,49]. If entrepreneurial behaviour is excluded from organisational models aimed at achieving strategic objectives, the representation becomes incomplete.

This conceptualisation is process-oriented and is often manifested in behavioural models ranging from the firm level to individual entrepreneurs [25]. Digitalisation enables firms to leverage both external and internal information as the foundation for entrepreneurial action. Once this limited information is transformed into action, entrepreneurs naturally utilise cognitive functions (i.e. knowledge) to identify and exploit new opportunities [65,66].

Competitive advantage refers to a firm's ability to achieve superior performance relative to rivals within the same market or industry [67]. This research adopts the framework introduced by [68] in Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (1985), which built on Porter’s earlier work Competitive Strategy (1980) [69].

Digitalisation serves as a crucial enabler of entrepreneurial activity in SMEs. Infrastructure systems—defined as foundational facilities, structures, tools, and installations—support this function [70]. In contemporary economic theory, digital infrastructure is often considered a form of public capital, supported by government investment in assets such as roads and bridges [71].

A prior study by [54] demonstrated that digitalisation and innovation constitute strategic resources. Innovation-driven digitalisation is vital for SMEs seeking to achieve sustainable performance and gain a competitive edge. The view is supported by [54], who contended that innovation-based digital tools are increasingly crucial for SMEs in responding to external pressures such as competition, globalisation, and market shifts driven by larger firms adopting RBV-based strategies.

Product innovation plays a decisive role in shaping firm competitiveness, performance, and growth—both for goods and service-based businesses [72]. Therefore, this study investigates the factors influencing competitiveness among leather SMEs by examining the role of digital marketing and entrepreneurial orientation in promoting product innovation and, ultimately, competitive advantage through the lens of the Resource-Based View.

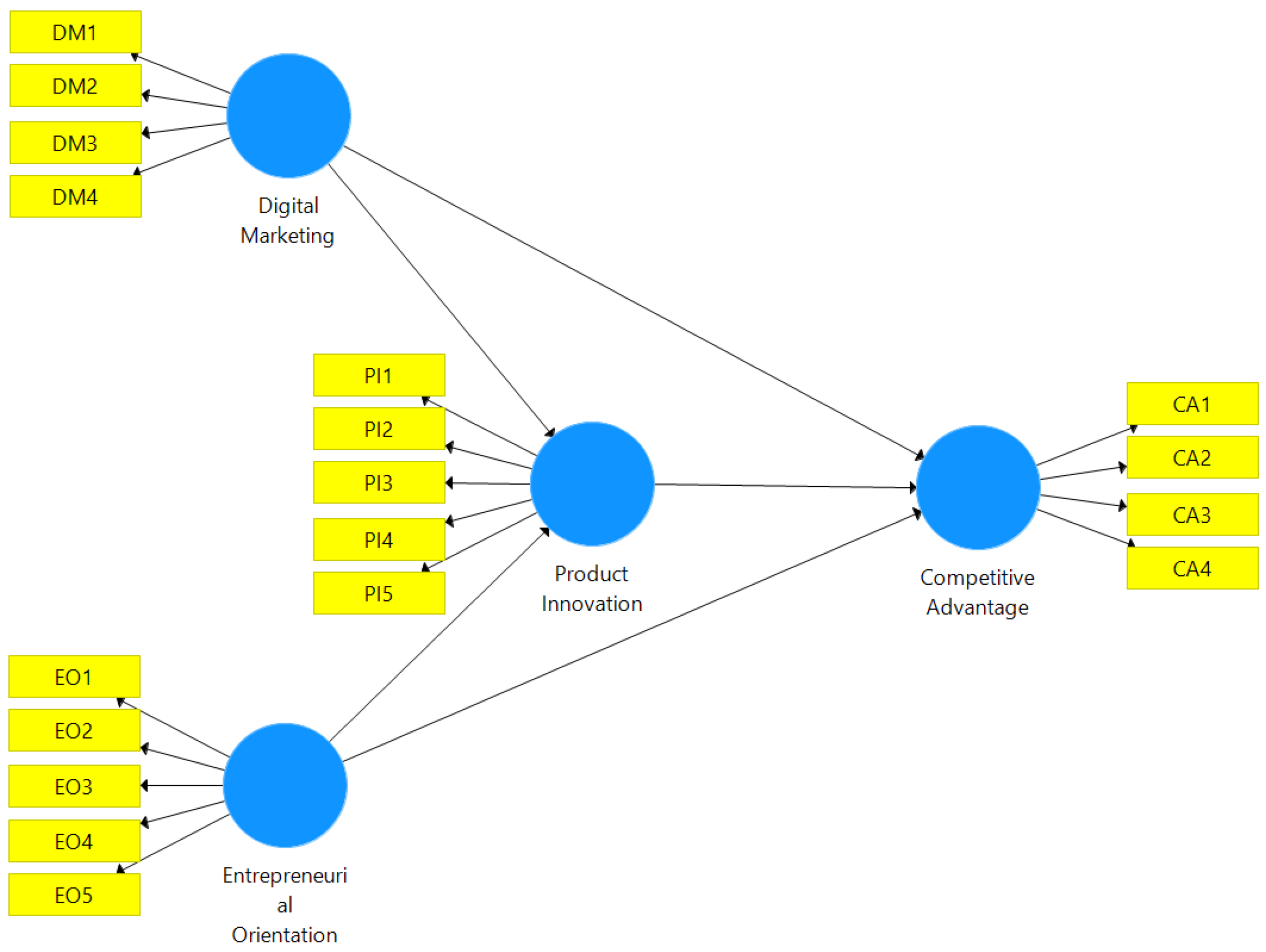

This study proposes a conceptual framework integrating Digital Marketing and Entrepreneurial Orientation as exogenous variables, with Product Innovation and Competitive Advantage as mediating and outcome variables. The model is empirically tested to evaluate the direct and indirect relationships among these constructs, as depicted in

Figure 1.

Based on the conceptual framework, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H1. Digital marketing has a positive effect on competitive advantage

H2. Entrepreneurial orientation has a positive effect on competitive advantage

H3. Digital marketing has a positive effect on product innovation

H4. Entrepreneurial orientation has a positive effect on product innovation

H5. Competitive advantage has a positive effect on product innovation

H6. Digital marketing, entrepreneurial orientation, and competitive advantage simultaneously affect product innovation

3. Materials and Methods

This research employed a deductive approach, involving theory verification through hypothesis testing to draw conclusions. The purpose was to assess pre-established hypotheses in order to reinforce or refute existing theoretical propositions. Such a study design is typically categorised as explanatory research [73]. The research adopted a positivist paradigm, consistent with the quantitative approach, aiming to uncover facts and social phenomena by developing hypotheses, collecting data from defined populations and samples, applying statistical analysis, and drawing general conclusions [74].

3.1. Population and Sample

The target population was identified based on data obtained from the Garut Regency Department of Industry and Trade and the Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) of Garut Regency (2023). This study focused specifically on all business actors within the leather craft subsector in Garut Regency. A total of 318 business units were verified to have adopted digital marketing practices during the research period in 2024.

Sampling was conducted using a probability sampling technique, a method commonly applied in quantitative research to ensure representativeness [75]. The chosen method was simple random sampling, selected for two primary reasons: (1) every member of the population had an equal chance of being included in the sample, and (2) the scope of the study was strictly limited to the leather craft subsector in Garut Regency.

Respondents were selected based on the following criteria: they must be owners or operators of SMEs (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises) in the leather craft subsector of Garut Regency, officially verified by the Garut Department of Industry and Trade, currently utilising digital marketing for product promotion, employing between 5 and 8 workers, earning monthly revenues between IDR 5 to 10 million, operating for at least four years, and qualifying as business units under Government Regulation No. 7 of 2021 concerning the Facilitation, Protection, and Empowerment of Cooperatives and MSMEs. The sample size was calculated using Slovin’s formula, resulting in a total of 177 respondents with a confidence level of 95%.

While covariance-based SEM typically requires large samples in the hundreds or thousands, Partial Least Squares SEM (SEM-PLS) is more suitable for studies with smaller sample sizes. SEM-PLS requires a minimum sample size equivalent to ten times the maximum number of formative indicators for any single latent variable, or ten times the number of structural paths directed at a particular latent construct in the model [76]. Based on this criterion, a sample of 177 respondents was deemed sufficient for this study.

3.2. Data Types, Sources, and Collection Techniques

The study utilised both primary and secondary data. Primary data were collected directly from business owners in the leather craft SME sector of Garut. Secondary data consisted of indirect sources such as books, e-books, peer-reviewed journals, and reputable international publishers (e.g., Scopus, Emerald, Springer, Elsevier), as well as statistical reports related to the development of leather craft SMEs in Garut Regency.

Data collection was conducted through a combination of questionnaires and interviews. The questionnaire included items regarding respondent characteristics and perceptions related to digital marketing, entrepreneurial orientation, product innovation, and competitive advantage. In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted with all 177 leather craft entrepreneurs who had implemented digital marketing strategies in their businesses

3.3. Definisi Operasional Variabel

This study employed four key constructs: Digital Marketing, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Product Innovation, and Competitive Advantage. The operationalisation of these variables is outlined in

Table 1, which includes the conceptual basis, dimensions, indicators, and scale type.

3.4. Structural Equation Model (SEM)-Partial Least Square (PLS)

To examine the influence of Digital Marketing and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Product Innovation through Competitive Advantage, this study utilised Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) with a Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach. Data were analysed using SmartPLS version 3.0. PLS-SEM is a variance-based statistical method suitable for complex regression models, particularly when challenges such as small sample size, missing values, and multicollinearity are present [77].

Unlike covariance-based SEM, PLS does not require strict assumptions about data distribution. It is primarily designed for prediction purposes and estimation of causal relationships within research models [78]. SEM allows simultaneous testing of multiple dependent relationships and is therefore ideal for studies involving complex, multi-dimensional models. Due to the complexity of managerial decision-making and the multidimensional nature of the constructs under investigation, SEM offers an integrated analytical framework that combines factor analysis, path analysis, and structural modelling [79]. The SEM analysis involves several stages, including theoretical model development, creation of a path diagram, and conversion of the path diagram into structural equations.

PLS analysis involves two main stages: outer model evaluation and inner model evaluation. The outer model (measurement model) assesses the validity and reliability of the measurement instruments. Indicators for assessing the outer model include convergent validity, average variance extracted (AVE), and Cronbach’s alpha. The inner model (structural model) is evaluated to determine the robustness and accuracy of the proposed relationships. Key indicators include the coefficient of determination (R²), predictive relevance (Q²), and the goodness-of-fit index.

4. Results

This section presents the results of the analysis examining the influence of Digital Marketing and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Product Innovation and its impact on Competitive Advantage in the leather craft subsector of Garut Regency. The collected data were coded and processed using descriptive statistical analysis to identify respondent perceptions of each research variable. This was followed by the application of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) using the Partial Least Squares (PLS) technique, based on responses from a sample of 177 participants.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to explore respondent perceptions regarding the four core variables: Digital Marketing, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Product Innovation, and Competitive Advantage. The analysis was based on frequency distribution and percentage for each item in the questionnaire. To aid interpretation, the data were organised using a continuum line method, and the percentage scores were categorised into interpretation ranges based on criteria adapted from Umi Narimawati (2010:85). The following subsections present the results for each variable.

4.1.1. Respondents’ Perceptions of Digital Marketing

Table 2 presents a summary of respondents’ perceptions of the Digital Marketing variable, which was measured using four dimensions and twelve indicator items. Based on the table, the highest percentage score was observed for the Interactivity dimension (88.06%), while the lowest scores were found in both Site Design and Cost dimensions (85.12%). The overall average percentage for the Digital Marketing variable was 86.25%, which falls into the “Very Good” category.

These results indicate that the application of digital marketing within SMEs in the leather craft sector has been positively perceived by business actors. This aligns with the findings of [80], which define digital marketing as the implementation of digital technology to manage online marketing channels—including websites, email, databases, digital television, and innovative tools such as blogs, RSS feeds, podcasts, and social media—to support marketing activities aimed at generating profits and retaining customers..

4.1.2. Respondents’ Perceptions of Entrepreneurial Orientation

Table 3 presents a summary of responses related to the Entrepreneurial Orientation variable, which was measured using five dimensions and fifteen statement items. The highest score was recorded for the Autonomy dimension (88.78%), while the lowest was found in the Risk-Taking dimension (85.31%). The overall percentage score for this variable was 86.34%, which falls within the “Very Good” category, based on the criteria by Umi Narimawati (2010:85). These findings are consistent with a study by Renita Helia (2021) on Batik SMEs in Laweyan, Solo, which concluded that entrepreneurial orientation has both partial and simultaneous effects on business performance. This highlights the strategic importance of entrepreneurial traits such as innovation, proactivity, and calculated risk-taking in sustaining SME growth.

4.1.3. Respondents’ Perceptions of Product Innovation

Table 4 summarises respondent perceptions of Product Innovation, measured through five dimensions and fifteen items. The highest score was observed in the Technological Fit dimension (86.85%), while the lowest score was in New Marketing Activities (84.11%). The total score percentage for this variable was 85.62%, categorised as “Very Good”. These results align with the findings of Taufiq et al. (2020), who stated that product innovation enables firms to creatively address challenges and capitalise on market opportunities, thus enhancing competitiveness in dynamic environments.

4.1.4. Respondents’ Perceptions of Competitive Advantage

Table 5 outlines respondent assessments of the Competitive Advantage variable, measured using four dimensions and twelve items. The highest score was observed in the Non-Substitutability dimension (88.81%), while the lowest was recorded in Rarity (83.92%). The total score percentage for this variable was 86.37%, also categorised as “Very Good”. These findings support prior research by Zuhdi et al. (2021), which underscores the critical role of competitive advantage in achieving sustainable business performance, especially in response to evolving global market dynamics and intensified competition.

4.2. Verificative Analysis Using SEM-PLS

Verificative analysis was conducted to test the proposed hypotheses through statistical computation. The primary objective was to assess the influence of Digital Marketing, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Product Innovation on Competitive Advantage using the Partial Least Squares - Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) approach, as implemented in SmartPLS version 3.0.

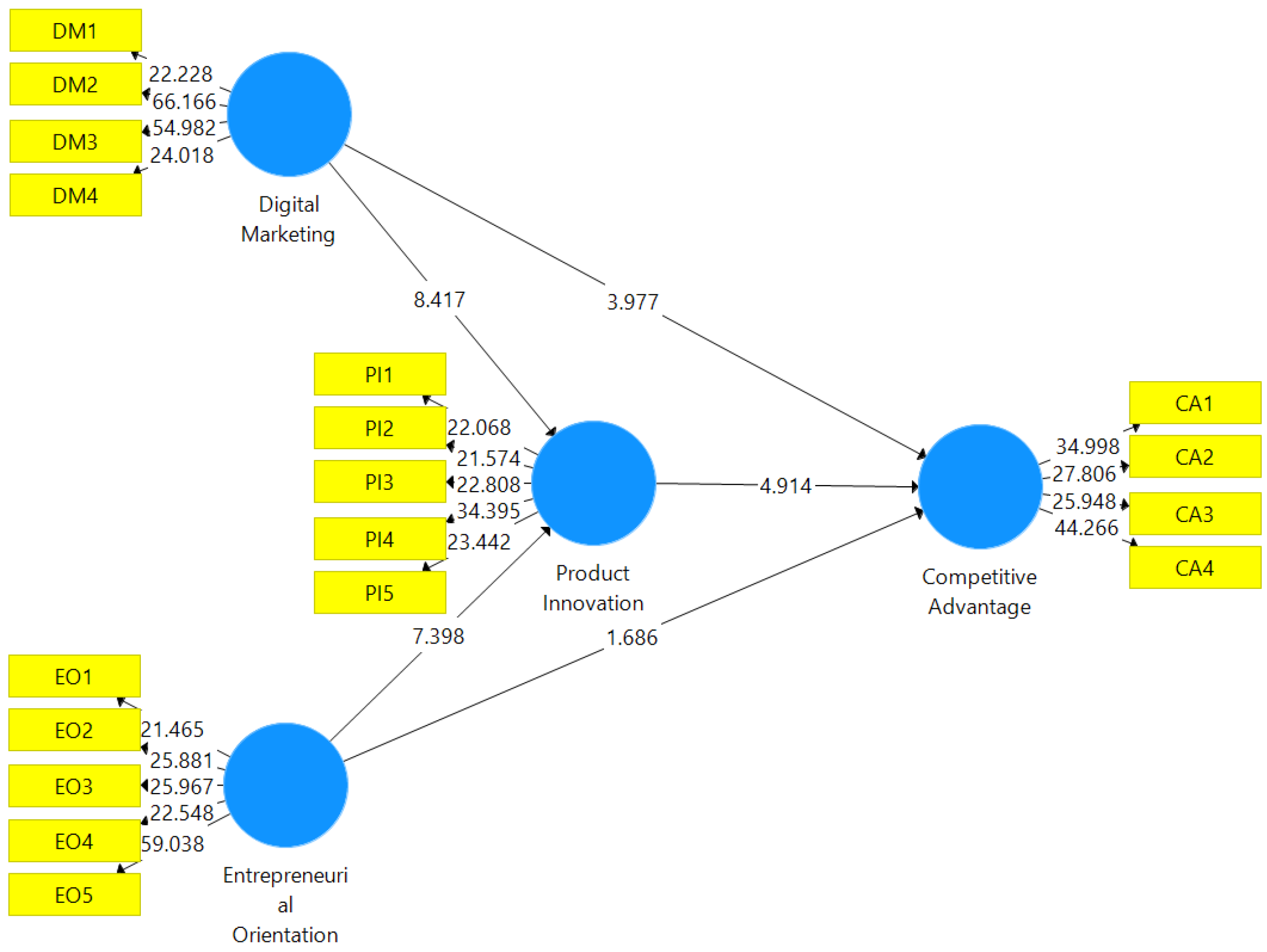

In Structural Equation Modelling, two main types of models are developed: the measurement model (also known as the outer model) and the structural model (also known as the inner model). The measurement model specifies the relationship between each latent variable and its respective manifest (indicator) variables, and evaluates how well these indicators explain the variance of the latent constructs. This step helps to identify which indicators are most representative of each latent variable.

Following the evaluation of the measurement model, the structural model is examined to test the causal relationships between exogenous latent variables (independent variables) and endogenous latent variables (dependent variables). In this study, the SEM model consisted of: Four latent variables: Digital Marketing (X1), Entrepreneurial Orientation (X2), Product Innovation (Y), and Competitive Advantage (Z). Eighteen manifest variables, distributed as follows: Digital Marketing (X1): 4 indicators; Entrepreneurial Orientation (X2): 5 indicators; Product Innovation (Y): 5 indicators; Competitive Advantage (Z): 4 indicators.

Figure 2.

Structural Model of Research Variables.

Figure 2.

Structural Model of Research Variables.

The structural model was evaluated through two main stages: the outer model analysis, followed by the inner model analysis. Each model was tested using the algorithm function in SmartPLS to assess validity and reliability.

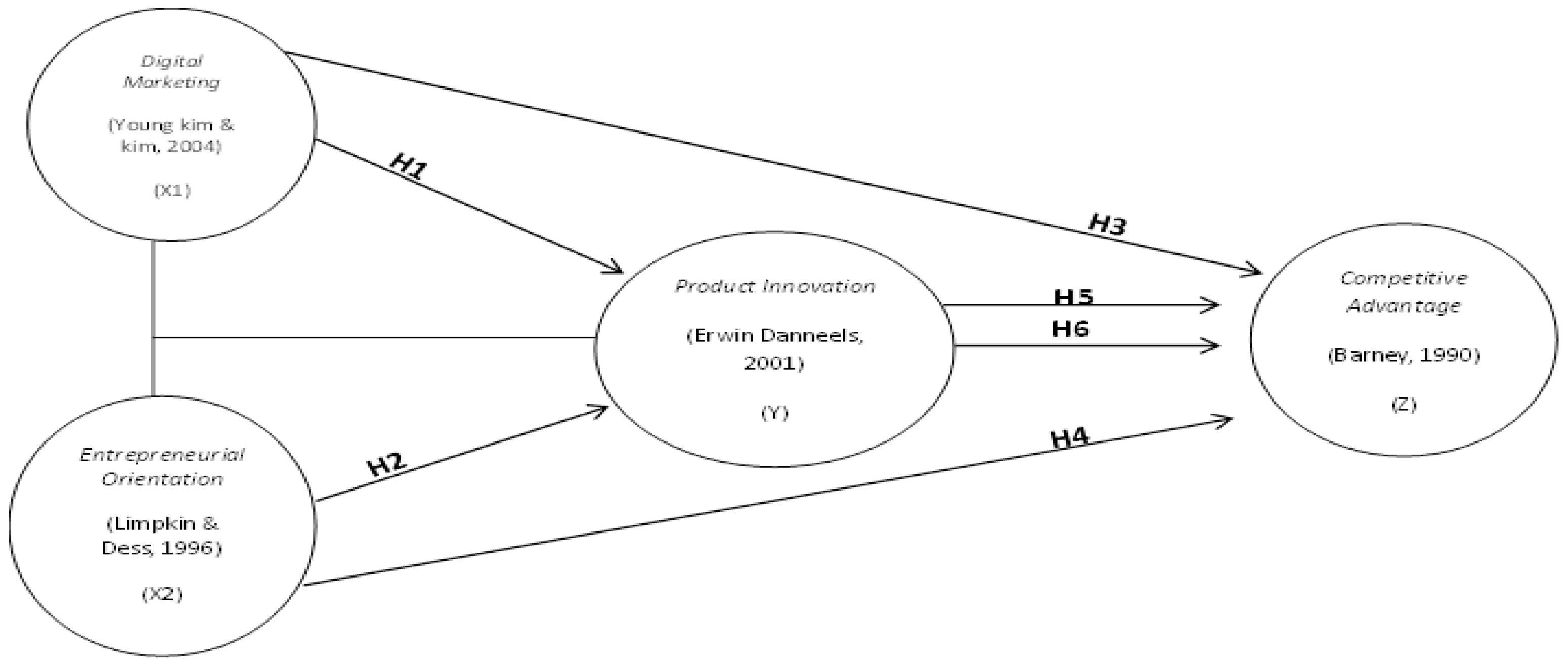

4.2.1. Measurement Model Evaluation (Outer Model)

The outer model evaluation aims to determine the relationship specifications between each latent variable and its corresponding manifest variables. The analysis included the following components: Convergent Validity; Discriminant Validity; Reliability Testing. The results of the outer model analysis—generated via the Algorithm function in SmartPLS—are illustrated in

Figure 3.

Convergent validity refers to the extent to which indicators of a latent construct share a high proportion of variance. According to established thresholds, convergent validity is considered adequate if the outer loading of each indicator exceeds 0.70 and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is above 0.50. As shown in

Table 6, all indicators meet these criteria, indicating that each manifest variable is a valid representation of its corresponding latent construct.

These results confirm that all indicators have strong convergent validity and are appropriate for inclusion in the model. Discriminant validity ensures that each construct is empirically distinct from the others. Two methods were applied to assess this: Cross Loadings and the Fornell–Larcker Criterion. Cross Loadings are presented in

Table 7. Each indicator’s loading is higher on its assigned latent variable than on other constructs, satisfying the discriminant validity requirement.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion further validates discriminant validity by comparing the square root of AVE values with the inter-construct correlations. As shown in

Table 8, each construct's AVE square root exceeds its correlations with other constructs, confirming adequate discriminant validity.

Construct reliability evaluates the internal consistency of each latent variable, using Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s Alpha. Both values should exceed 0.60 to indicate sufficient reliability [78]. As shown in

Table 9, all constructs exceed this threshold, confirming that the indicators consistently measure their respective latent variables.:

The results of the measurement model evaluation indicate that all constructs in this study satisfy the requirements for convergent validity, discriminant validity, and construct reliability. Thus, the measurement model is deemed valid and reliable for further structural analysis.

4.2.2. Structural Model Evaluation (Inner Model)

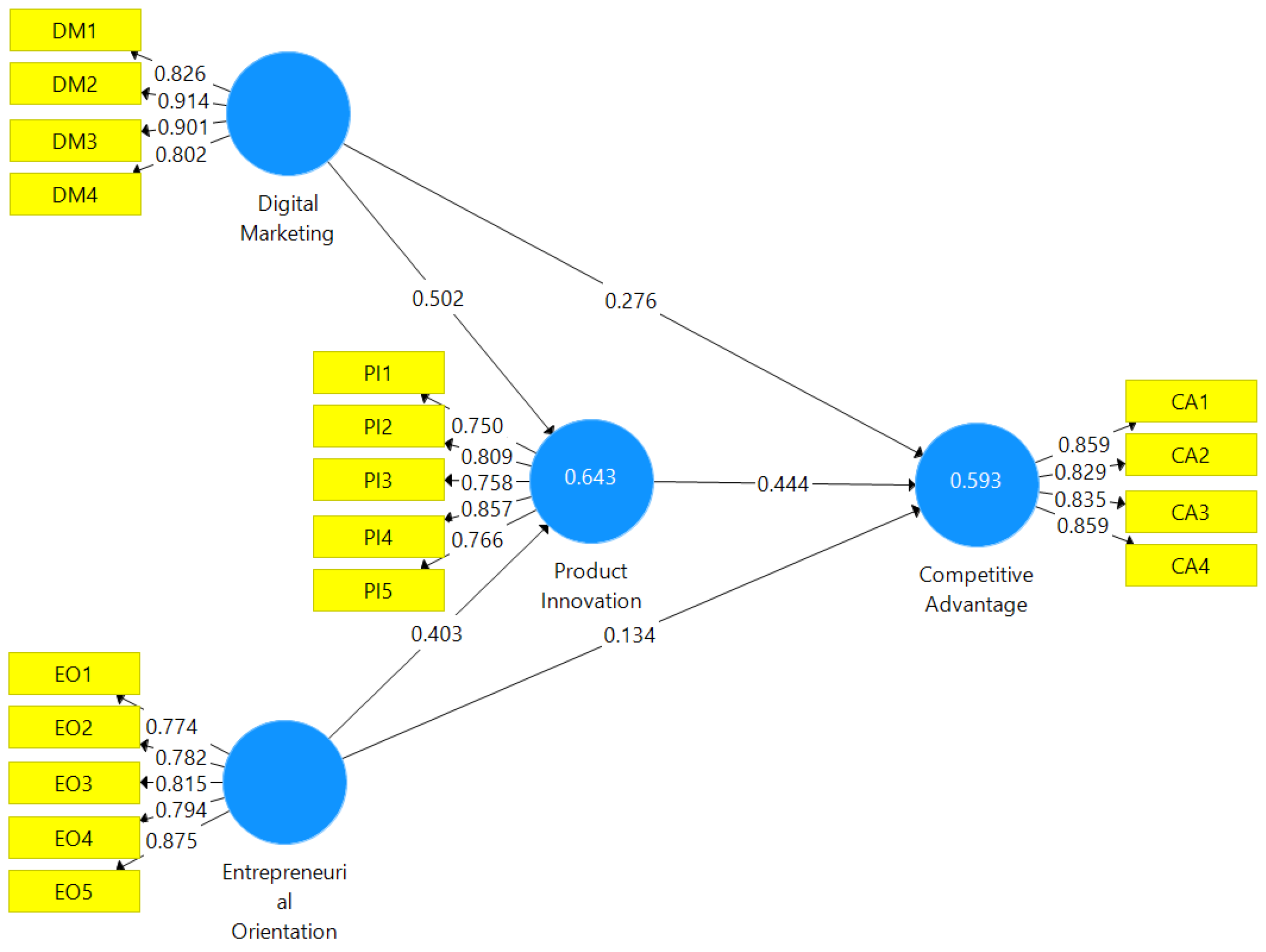

The structural model, or inner model, was evaluated to assess the hypothesised causal relationships between the latent variables. This evaluation involved the analysis of path coefficients, coefficient of determination (R²), predictive relevance (Q²), and Goodness of Fit (GoF). The significance of each relationship was determined using the bootstrapping procedure in SmartPLS 3.0, which generates t-statistics and p-values for hypothesis testing.

Figure 4.

Full Structural Model with Bootstrapping Results.

Figure 4.

Full Structural Model with Bootstrapping Results.

The R² value represents the degree to which variance in the endogenous variable is explained by its predictors. According to Chin (2013), the thresholds for R² interpretation are: 0.67 (strong), 0.33 (moderate), and 0.19 (weak). As shown in

Table 10, the first endogenous construct, Product Innovation (Y), is explained by Digital Marketing (X1) and Entrepreneurial Orientation (X2) with an R² value of 0.643, indicating a moderate explanatory power. The second endogenous construct, Competitive Advantage (Z), is explained by Digital Marketing (X1), Entrepreneurial Orientation (X2), and Product Innovation (Y) with an R² value of 0.593, also indicating moderate explanatory strength.

The Q² value, obtained through blindfolding, assesses the model’s predictive relevance. A Q² value greater than zero indicates that the model has predictive relevance for the corresponding endogenous construct. As shown in

Table 11, all Q² values exceed the threshold of zero, confirming that the model has sufficient predictive capability.

The Goodness of Fit (GoF) index integrates the performance of both the measurement and structural models. It is calculated as the square root of the product of the average AVE and average R². According to Latan and Ghozali (2012), the GoF thresholds are: 0.10 (small), 0.25 (medium), and 0.36 (large).

4.3. Pengaruh Langsung

Direct path relationships are considered statistically significant if the t-statistic exceeds 1.96 and the p-value is below 0.05 (Yamin, 2011). The analysis results show that all hypothesised direct effects are significant:

Digital Marketing → Product Innovation: Path coefficient = 0.502, p < 0.001

Entrepreneurial Orientation → Product Innovation: Path coefficient = 0.403, p < 0.001

- 2.

Sub-Structure 2: Competitive Advantage Model

Digital Marketing → Competitive Advantage: Path coefficient = 0.499, p < 0.001

Entrepreneurial Orientation → Competitive Advantage: Path coefficient = 0.313, p < 0.001

Product Innovation → Competitive Advantage: Path coefficient = 0.444, p < 0.001,4%.

4.4. Indirect Effects

The mediating role of Product Innovation was examined to determine whether it significantly transmits the effects of Digital Marketing and Entrepreneurial Orientation to Competitive Advantage. Mediation via Product Innovation:

Indirect effect: 0.223, t-statistic: 4.651, p-value: 0.000. Interpretation: The effect is significant. Product Innovation mediates and strengthens the influence of Digital Marketing on Competitive Advantage.

- 2.

Entrepreneurial Orientation → Product Innovation → Competitive Advantage

Indirect effect: 0.179, t-statistic: 3.809, p-value: 0.000. Interpretation: The effect is significant. Product Innovation acts as a mediator in the relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Competitive Advantage.

5. Discussion

Based on the findings of this study, which examined the influence of Digital Marketing and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Competitive Advantage through Product Innovation within the leather craft sub-sector in Garut Regency, it can be concluded that product innovation plays a central role in strengthening competitive advantage. The relationship is complex and multidimensional, indicating that both digital marketing and entrepreneurial orientation contribute positively to competitive advantage, particularly when mediated by product innovation.

The results demonstrate that leather craft SMEs in Garut have demonstrated the capacity to incorporate digital marketing into their business management practices effectively. The agility of these entrepreneurs in responding to environmental changes is largely attributed to their high level of entrepreneurial orientation. This orientation represents an important intangible resource that enables firms to remain flexible and responsive in a dynamic market environment. Furthermore, entrepreneurial orientation fosters an organisational climate conducive to both exploration and exploitation of new business opportunities.

These findings reinforce the relevance of competitive advantage for SMEs in the leather craft industry. While the conceptualisation of competitive advantage remains a topic of academic debate, this study aligns with the perspective of [81], which defines competitive advantage in small businesses as a unique attribute that distinguishes one firm from its competitors, enabling it to succeed in the marketplace.

From an empirical standpoint, innovation facilitates an organisation's ability to explore and exploit novel ideas while adapting to change [82,83,84]. As innovation and technological advancement increasingly become core components of competitive strategy [85], the ability to sustain entrepreneurial efforts and embed innovation into organisational routines emerges as a significant source of long-term advantage. When innovation processes or outcomes are difficult to imitate, firms can leverage these unique capabilities to sustain their competitive positions.

Furthermore, [86] highlighted that product attributes such as form, function, price, and distribution can help reduce reliance on imitation by competitors. Beyond product innovation, managerial innovation—such as strategic human resource management (Schuler & Jackson, 1989)—and information-based innovation—such as novel market research techniques—can also provide more sustainable competitive positions compared to product-centric innovation alone.

In this context, product innovation reflects an organisation’s ability to perceive change as opportunity. The presence of entrepreneurial orientation enhances the firm’s perceptual capacity to frame environmental shifts as business potential. This reflects a proactive attitude, characterised by anticipation and vigilance in responding to market dynamics [87], and positions firms as pioneers in adopting new methods, technologies, and products [88,89].

Lastly, competitive advantage is defined as the ability to outperform rivals by adopting distinctive strategies that are difficult to replicate ([9,90]). Such advantage is achieved when firms can leverage unique internal resources and capabilities—such as expertise and operational efficiency—to deliver superior customer value at a relatively lower cost. Previous studies have also found that firm age contributes to the accumulation of such capabilities and the strengthening of competitive advantage.

6. Conclusions

This study has empirically demonstrated that both digital marketing and entrepreneurial orientation significantly influence product innovation and competitive advantage within the leather craft industry in Garut Regency. Specifically, digital marketing contributes 50.2% to product innovation and 27.6% to competitive advantage. Entrepreneurial orientation exerts an influence of 40.3% on product innovation and 31.3% on competitive advantage. Furthermore, product innovation was found to positively affect competitive advantage, contributing 44.4%. Collectively, the three variables account for 59.3% of the variance in enhancing the competitiveness of the leather craft industry.

In light of these findings, it is recommended that leather craft entrepreneurs continuously adapt to the dynamic nature of digital marketing trends by implementing broader digital marketing strategies, such as the utilisation of websites and search engine optimisation (SEO). Participation in digital marketing training programmes—offered by governmental agencies or online platforms such as Digitademy, HubSpot Academy, and Facebook Blueprint—is also advised. Consistency in content marketing practices is identified as a critical success factor.

From a product innovation perspective, it is advisable for artisans to adopt or adapt product models inspired by established brands to remain aligned with market trends and improve their competitive positioning. This strategy could support sustained product relevance and enhance value perception among consumers. Future research should explore additional factors influencing digital marketing effectiveness, including the types of digital media used, market reach, and consumer targeting strategies. Other dimensions of product innovation—such as pricing, branding, product quality, and consumer psychological factors—also present promising areas for further investigation. Employing more qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews with leather artisans, may provide richer insights into the digital marketing strategies applied and the practical challenges faced in improving product competitiveness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Mochamad Yasin Noer conceptualized the study, conducted the primary research, and performed data collection and analysis as part of his doctoral research. Arianis Chan, as the principal supervisor, provided guidance on research design, methodology, and theoretical framework development. Pratami Wulan Tresna and Ratih Purbasari, as co-supervisors, contributed to refining the research objectives, data interpretation, and structuring the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained all subjects involved in the study to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available upon reasonable request. Due to confidentiality and privacy considerations, data access is restricted but may be granted upon request to the corresponding author. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Mochamad Yasin Noer, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the leather craft SMEs in Garut for their participation and cooperation in this study. We also extend our thanks to Universitas Padjadjaran for providing administrative and technical support throughout the research process. Special appreciation is given to the local government and industry associations for facilitating access to data and resources. Lastly, we acknowledge the valuable feedback from our colleagues and peers, which greatly contributed to the improvement of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Crossan, M.; E Cunha, M.P.; Vera, D.; Cunha, J. Time and Organizational Improvisation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, M.; Ismail, R.; Fooladi, M. Information and Communication Technology Use and Economic Growth. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e48903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feniser, C.; Burz, G.; Mocan, M.; Ivascu, L.; Gherhes, V.; Otel, C.C. The Evaluation and Application of the TRIZ Method for Increasing Eco-Innovative Levels in SMEs. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Davcik, N.S.; Pillai, K.G. Product innovation as a mediator in the impact of R&D expenditure and brand equity on marketing performance. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5662–5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Palmer, C.; Kailer, N.; Kallinger, F.L.; Spitzer, J. Digital entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. [CrossRef]

- Stawicka, E. Sustainable Development in the Digital Age of Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiprasit, S.; Swierczek, F.W. Competitiveness, globalization and technology development in Thai firms. Competitiveness Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2011, 21, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities: Routines versus Entrepreneurial Action. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. New global strategies for competitive advantage. Plan. Rev. 1990, 18, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: a configurational approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stel, A.; Carree, M.; Thurik, R. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Activity on National Economic Growth. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markley, D.M.; Lyons, T.S.; Macke, D.W. Creating entrepreneurial communities: building community capacity for ecosystem development. Community Dev. 2015, 46, 580–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Ebner, D. Corporate sustainability strategies: sustainability profiles and maturity levels. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. J. Teece, G. D. J. Teece, G. Pisano, and A. Shuen, “Dynamic capabilities and strategic management,” Strategic Management Journal, vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelt, R.P.; Schendel, D.; Teece, D.J. Strategic management and economics. Strat. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. R. David and S. Carolina, Strategic Management Concepts and Cases. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Aransyah, M.F.; Hermanto, B.; Muftiadi, A.; Oktadiana, H. Exploring sustainability oriented innovations in tourism: insights from ecological modernization, diffusion of innovations, and the triple bottom line. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.G. security risk, that they have environmental threats, but sible." 10 Here Levy displays his own. Environ. Chang. Secur. Proj. Rep. 1996, 2, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hitt, R. D. M. A. Hitt, R. D. Ireland, and R. E. Hoskisson, Strategic management cases: competitiveness and globalization. Cengage Learning, 2012.

- Hoskisson, R.E.; Hitt, M.A.; Wan, W.P.; Yiu, D. Theory and research in strategic management: Swings of a pendulum. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 417–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, O.; Thomas, H.; Goussevskaia, A. The structure and evolution of the strategic management field: A content analysis of 26 years of strategic management research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Feng, Z.; Chen, J. Microstructures and properties of titanium–copper lap welded joints by cold metal transfer technology. Mater. Des. 2014, 53, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.; Backhaus, U. The Theory of Economic Development; Springer, Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 61–116;

- C. M. Grimm, H. C. M. Grimm, H. Lee, and K. G. Smith, “Strategy as action: Competitive dynamics and competitive advantage,” Management, 2006.

- Mata, F.J.; Fuerst, W.L.; Barney, J.B. Information Technology and Sustained Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based Analysis. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strat. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terziovski, Milé. 2010. Innovation Practice and Its Performance Implications in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the Manufacturing Sector: A Resource Based View. Strategic Management Journal 31 (8): 892–902. [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, “Concept of Strategy,” in Corporate Strategy, 1965.

- Hoskisson, R.E.; Eden, L.; Lau, C.M.; Wright, M. STRATEGY IN EMERGING ECONOMIES. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Penrose, Theory of the growth of the firm. 1959.

- B. Wernerfelt, “Consumers with differing reaction speeds, scale advantages and industry structure,” Eur Econ Rev, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 257–270, 1984.

- C. K. Prahalad and G. Hamel, “The Core Competencies of the Corporation,” Harv Bus Rev, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 1990; 91.

- Tallon, P.P. Inside the adaptive enterprise: an information technology capabilities perspective on business process agility. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2007, 9, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.; Grover, V. Leveraging Information Technology Infrastructure to Facilitate a Firm's Customer Agility and Competitive Activity: An Empirical Investigation. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 28, 231–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Cai, Q. Z. Cai, Q. Huang, H. Liu, R. M. Davison, and L. Liang, “Developing Organizational Agility through IT Capability and KM Capability: The Moderating Effects of Organizational Climate.,” in PACIS, 2013, p. 245.

- Lee, V.-H.; Foo, A.T.-L.; Leong, L.-Y.; Ooi, K.-B. Can competitive advantage be achieved through knowledge management? A case study on SMEs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 65, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, M.M.; Hamid, A.B.A.; Soltanic, I.; Mardani, A.; Soltan, E.K.H. The Role of Supply Chain Antecedents on Supply Chain Agility in SMEs: The Conceptual Framework. J. Teknol. 2013, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambamurthy; Bharadwaj; Grover Shaping Agility through Digital Options: Reconceptualizing the Role of Information Technology in Contemporary Firms. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 237. [CrossRef]

- G. Hamel and C. K. Prahalad, “Capabilities-based competition,” Harv Bus Rev, 1992.

- Luftman, J.; Papp, R.; Brier, T. Enablers and Inhibitors of Business-IT Alignment. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 1999, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J.H. Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, C.C.; Williamson, P.J. Related diversification, core competences and corporate performance. Strat. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, T.C. Competitive advantage: logical and philosophical considerations. Strat. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-J.; Smith, K.G.; Grimm, C.M. Action Characteristics as Predictors of Competitive Responses. Manag. Sci. 1992, 38, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. M. Grimm, H. C. M. Grimm, H. Lee, and K. G. Smith, Strategy as action: Competitive dynamics and competitive advantage. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, W.J.; Smith, K.G.; Grimm, C.M. THE ROLE OF COMPETITIVE ACTION IN MARKET SHARE EROSION AND INDUSTRY DETHRONEMENT: A STUDY OF INDUSTRY LEADERS AND CHALLENGERS. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahovac, J.; Miller, D.J. Competitive advantage and performance: the impact of value creation and costliness of imitation. Strat. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 1192–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Chen and K. Siau, “Effect of Business Intelligence and IT Infrastructure Flexibility on Organizational Agility,” International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2012, pp. 14–15, 2012.

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Madhavan, R. Cooperative Networks and Competitive Dynamics: a Structural Embeddedness Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannoy, S.A.; Salam, A.F. Managerial Interpretations of the Role of Information Systems in Competitive Actions and Firm Performance: A Grounded Theory Investigation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 496–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, M.; El-Kassar, A.-N.; Tarhini, A. Impact of ICT-based innovations on organizational performance. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2017, 30, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higón, D.A. The impact of ICT on innovation activities: Evidence for UK SMEs. Int. Small Bus. Journal: Res. Entrep. 2011, 30, 684–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, T.V.; A Johnston, K. ICT Utilisation within Experienced South African Small and Medium Enterprises. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 64, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, T.V.; Johnston, K.A. The impacts of ICT utilisation and dynamic capabilities on the competitive advantage of South African SMEs. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2016, 15, 59–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P.; Ramsey, E.; Ibbotson, P. Entrepreneurial marketing in SMEs: the key capabilities of e-CRM. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2012, 14, 40–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadadevaramath, R.S.; Chen, J.C.; Sangli, M. Attitude of small and medium enterprises towards implementation and use of information technology in India - an empirical study. Int. J. Bus. Syst. Res. 2015, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibelushi, C.; Trigg, D. Internal self-assessment for ICT SMEs: a way forward. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2012, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Olatokun and M. Kebonye, “e-Commerce Technology Adoption by SMEs in Botswana e-Commerce Technology Adoption by SMEs in Botswana Introduction,” International Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 42–56, 2010.

- Maguire, S.; Koh, S.; Magrys, A. The adoption of e-business and knowledge management in SMEs. Benchmarking: Int. J. 2007, 14, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A. TRUSTWORTHINESS AS A SOURCE OF COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE IN ONLINE AUCTION MARKETS. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2002, 2002, A1–A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotter, A. Reason in human affairs. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1985, 6, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. A. Simon, “Empirically Grounded Economic Reason,” in Models of Bounded Rationality, vol. 3: Empiric, 1997, pp. 291–298.

- Farag, S.S.; Archer, K.J.; Mrózek, K.; Ruppert, A.S.; Carroll, A.J.; Vardiman, J.W.; Pettenati, M.J.; Baer, M.R.; Qumsiyeh, M.B.; Koduru, P.R.; et al. Pretreatment cytogenetics add to other prognostic factors predicting complete remission and long-term outcome in patients 60 years of age or older with acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 8461. Blood 2006, 108, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. TECHNOLOGY AND COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE. J. Bus. Strat. 1985, 5, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, T. Competitive strategy and strategic agendas. Strat. Chang. 2001, 10, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, T. Creative industries and economic evolution. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2013, 19, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulos, N.L. Principles and Methods of Law and Economics; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- P. Kotler and K. L. Keller, MarkKotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2016). Marketing Management. Global Edition (Vol. 15E). [CrossRef]

- P. D. Leedy and J. E. Ormrod, Practical research. Pearson Custom, 2005.

- Wollenschläger, F. A New Fundamental Freedom beyond Market Integration: Union Citizenship and its Dynamics for Shifting the Economic Paradigm of European Integration. Eur. Law J. 2010, 17, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Teddlie and F. Yu, “Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples,” J Mix Methods Res, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 77–100, 2007.

- S. and Suwarno, Model Persamaan Structural, Teori dan Aplikasinya. Bogor: IPB Press, 2002.

- et al. Hair, A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks. 2017.

- J. F. Hair, W. C. J. F. Hair, W. C. Black, B. J. Babin, and R. E. Anderson, Multivariate Data Analysis 7th Edition - Pearson New International Edition. 2010.

- Hair, F.J., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; G. Kuppelwieser, V. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. S. St. Rukaiyah, Syamsuddin Bidol, “Pengaruh Digitalmarketing Dan Inovasi Produk Terhadap Peningkatan Volume Penjualan Pada Usaha Kecil Di Kota Makassar,” vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 13–27, 2024.

- T. N. Q. Nguyen, “Knowledge management capability and competitive advantage: an empirical study of Vietnamese enterprises,” 2010.

- Aransyah, M.F. How Effective is the Green Financing Framework for Renewable Energy? A Case Study of PT Pertamina Geothermal Energy in Indonesia. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2023, 13, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance: An Assessment of past Research and Suggestions for the Future. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It To Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Gartner, W.B.; Wilson, R. Entry order, market share, and competitive advantage: A study of their relationships in new corporate ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 1989, 4, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, M. Sources of durable competitive advantage in new products. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1990, 7, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.E.; Sinkula, J.M. The Complementary Effects of Market Orientation and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Profitability in Small Businesses. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2009, 47, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X.; Wang, Y. The Impact of AI-Personalized Recommendations on Clicking Intentions: Evidence from Chinese E-Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintal, V.A.; Lee, J.A.; Soutar, G.N. Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldivia, M.; Chowdhury, S. Adapting Business Models in the Age of Omnichannel Transformation: Evidence from the Small Retail Businesses in Australia. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).