Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Aspects

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Vesicle Isolation and Purification

2.4. EV Sample Preparation for MS-Based Proteomics Analysis

2.5. EV Identification of Metabolites with GC-MS

3. Results

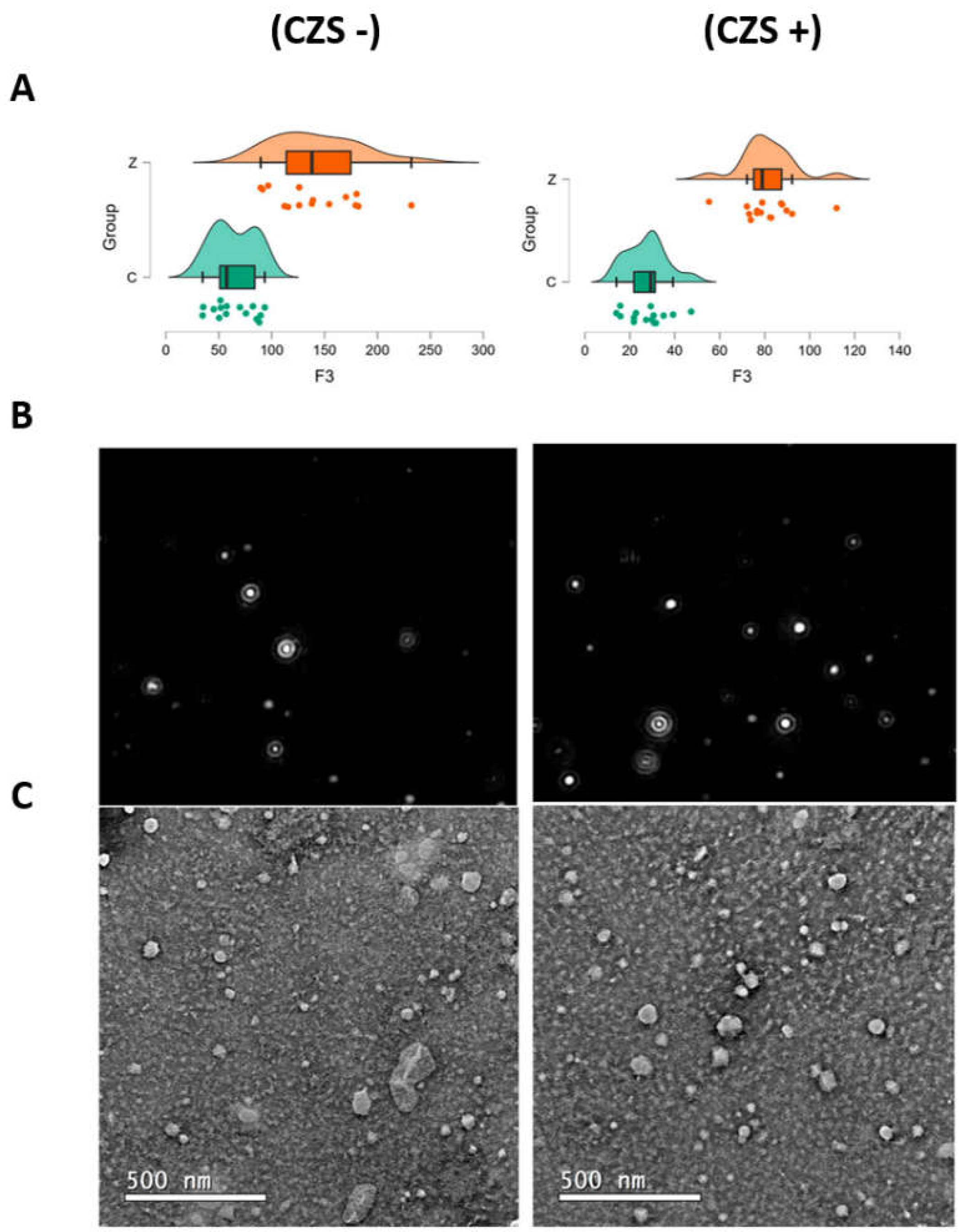

3.1. EV Characterization

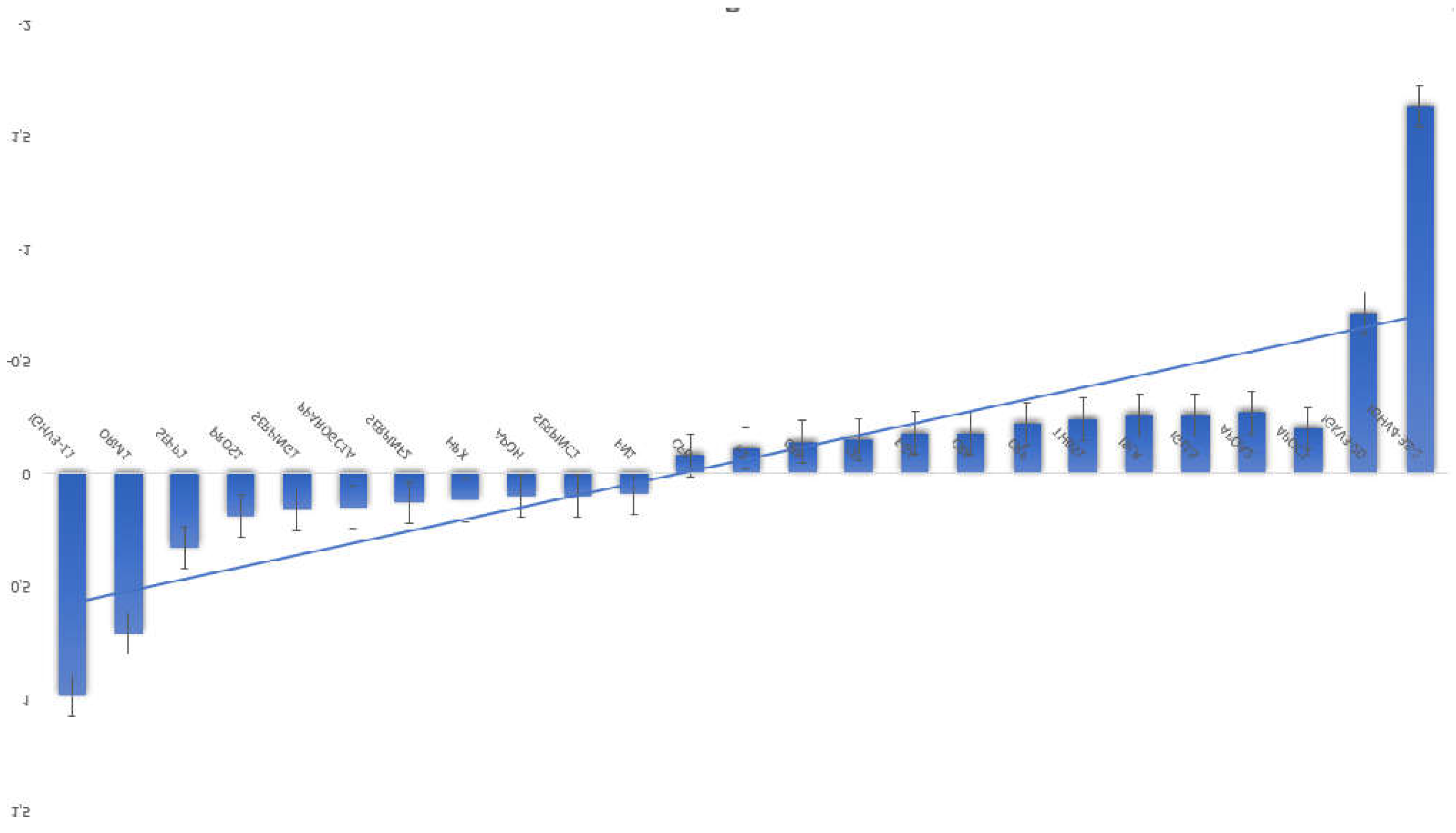

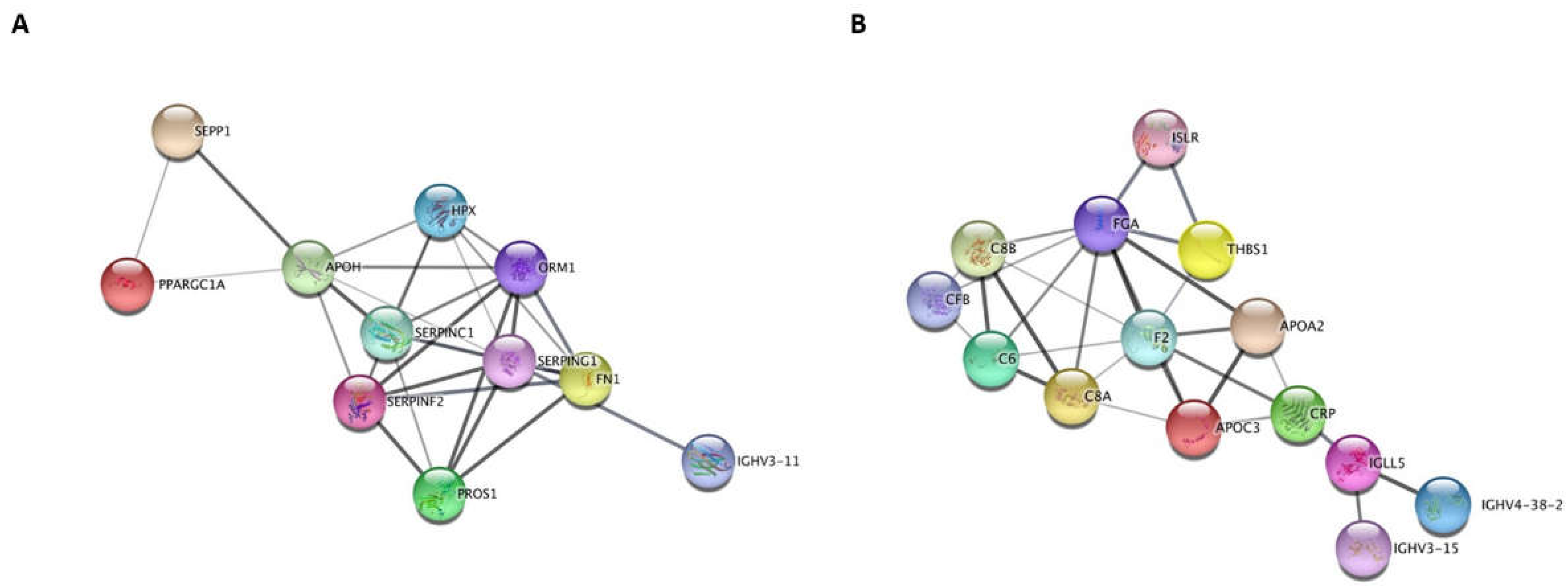

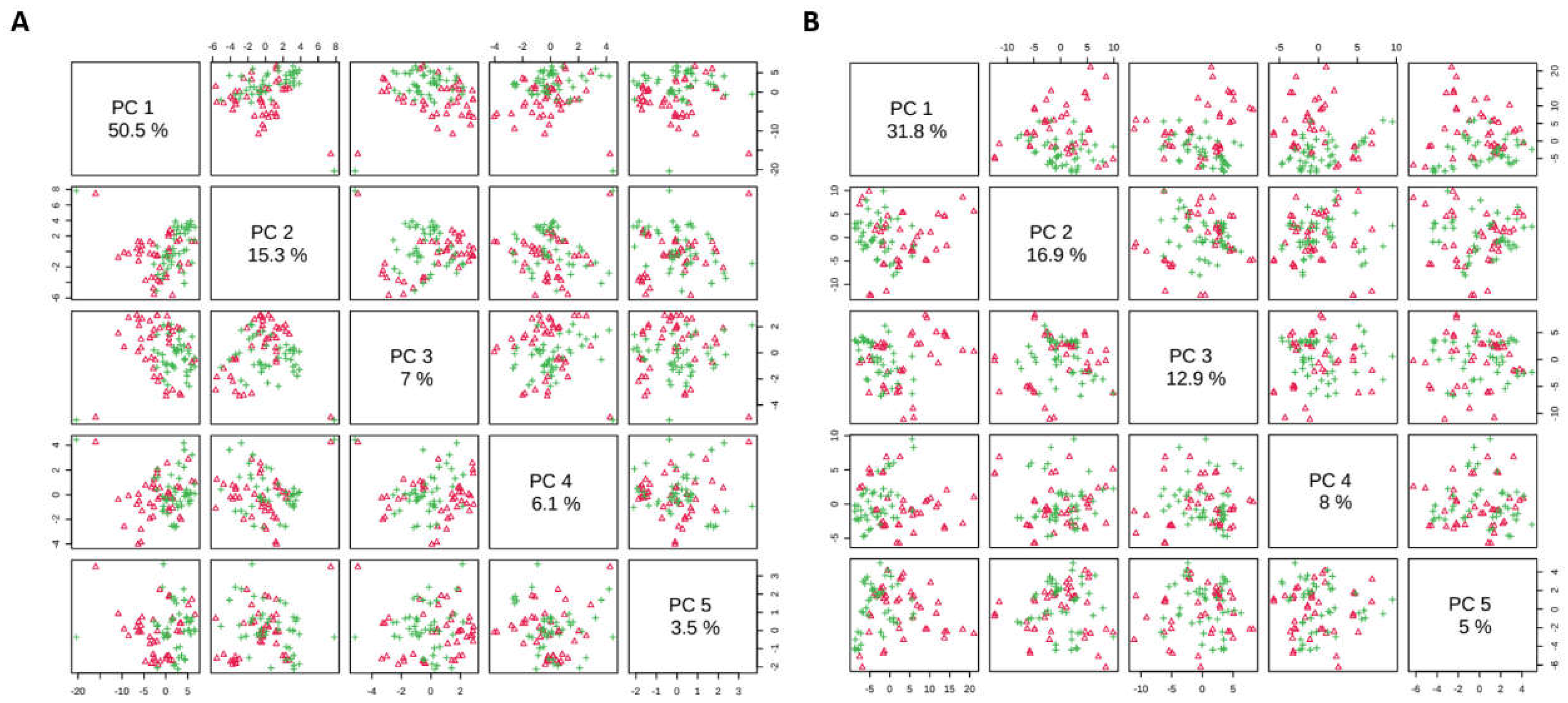

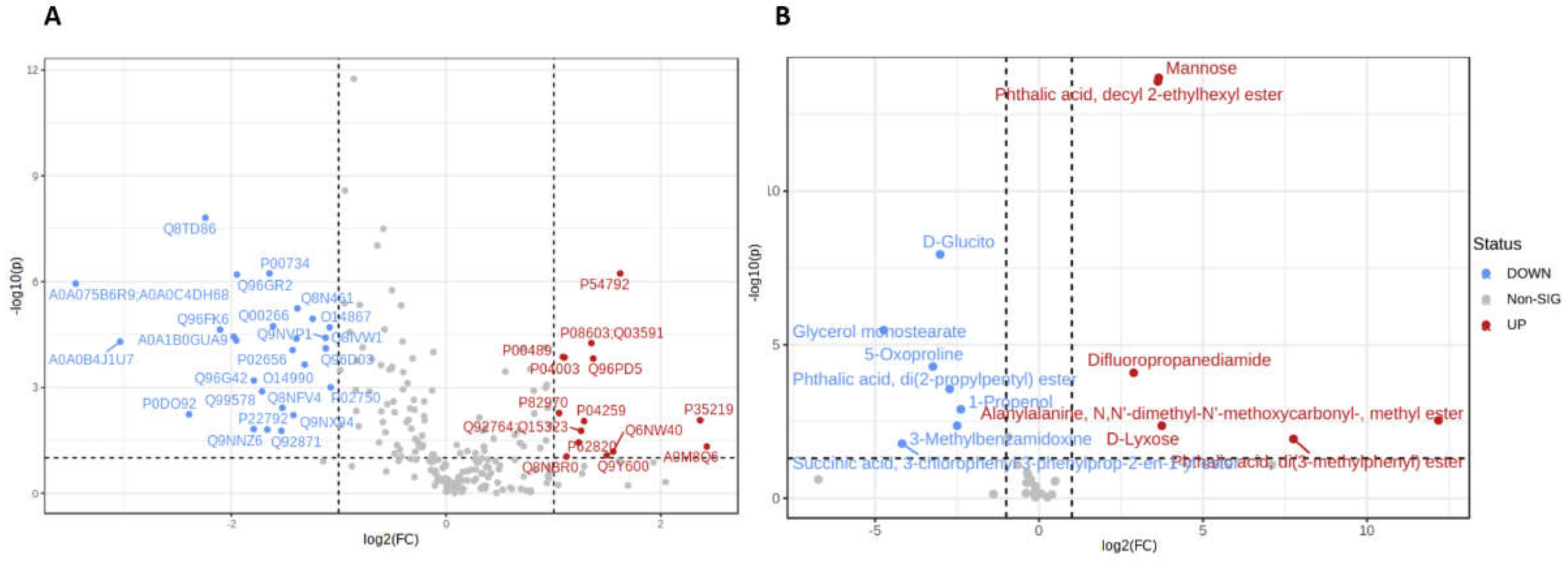

3.2. Proteomic Analysis

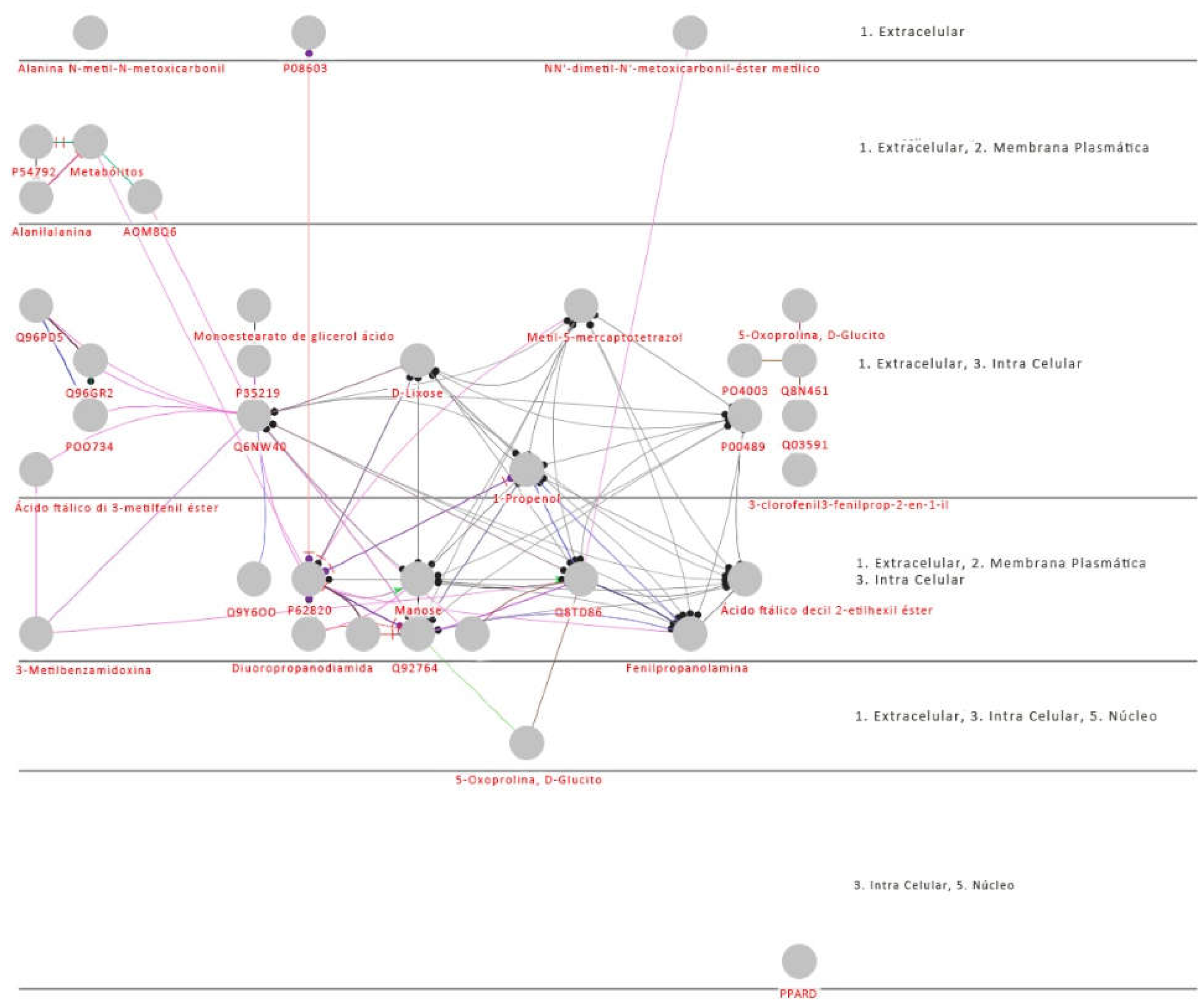

3.1. Proteomics and Metabolomics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dick, G.W.A.; Kitchen, S.F.; Haddow, A.J. Zika Virus (I). Isolations and Serological Specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1952, 46, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oehler, E.; Watrin, L.; Larre, P.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Lastère, S.; Valour, F.; Baudouin, L.; Mallet, H.P.; Musso, D.; Ghawche, F. Zika Virus Infection Complicated by Guillain-Barré Syndrome – Case Report, French Polynesia, December 2013. Eurosurveillance 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozé, B.; Najioullah, F.; Fergé, J.-L.; Apetse, K.; Brouste, Y.; Cesaire, R.; Fagour, C.; Fagour, L.; Hochedez, P.; Jeannin, S.; et al. Zika Virus Detection in Urine from Patients with Guillain-Barré Syndrome on Martinique, January 2016. Eurosurveillance 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman, M.G.; Harris, E. Dengue. The Lancet 2015, 385, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, M.N.; Marten, A.D.; Moore, G.A.; Tree, M.O.; McBrayer, S.P.; Conway, M.J. Extracellular Vesicles Restrict Dengue Virus Fusion in Aedes Aegypti Cells. Virology 2020, 541, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvet, G.; Aguiar, R.S.; Melo, A.S.O.; Sampaio, S.A.; de Filippis, I.; Fabri, A.; Araujo, E.S.M.; de Sequeira, P.C.; de Mendonça, M.C.L.; de Oliveira, L.; et al. Detection and Sequencing of Zika Virus from Amniotic Fluid of Fetuses with Microcephaly in Brazil: A Case Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.F.; Voon, G.Z.; Lim, H.X.; Chua, M.L.; Poh, C.L. Innate and Adaptive Immune Evasion by Dengue Virus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The Biology, Function, and Biomedical Applications of Exosomes. Science (1979) 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conzelmann, C.; Groß, R.; Zou, M.; Krüger, F.; Görgens, A.; Gustafsson, M.O.; El Andaloussi, S.; Münch, J.; Müller, J.A. Salivary Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Zika Virus but Not SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J Extracell Vesicles 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rojas, P.P.; Quiroz-García, E.; Monroy-Martínez, V.; Agredano-Moreno, L.T.; Jiménez-García, L.F.; Ruiz-Ordaz, B.H. Participation of Extracellular Vesicles from Zika-Virus-Infected Mosquito Cells in the Modification of Naïve Cells’ Behavior by Mediating Cell-to-Cell Transmission of Viral Elements. Cells 2020, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.; Palviainen, M.; Reichardt, N.-C.; Siljander, P.R.-M.; Falcón-Pérez, J.M. Metabolomics Applied to the Study of Extracellular Vesicles. Metabolites 2019, 9, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Guo, M.; Tan, Q.; Zhou, E.; Deng, J.; Li, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Jin, Y. Metabolomics of Extracellular Vesicles: A Future Promise of Multiple Clinical Applications. Int J Nanomedicine 2022, Volume 17, 6113–6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alseekh, S.; Aharoni, A.; Brotman, Y.; Contrepois, K.; D’Auria, J.; Ewald, J.; C. Ewald, J.; Fraser, P.D.; Giavalisco, P.; Hall, R.D.; et al. Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics: A Guide for Annotation, Quantification and Best Reporting Practices. Nat Methods 2021, 18, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okkenhaug, K.; Graupera, M.; Vanhaesebroeck, B. Targeting PI3K in Cancer: Impact on Tumor Cells, Their Protective Stroma, Angiogenesis, and Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 2016, 6, 1090–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castel, P.; Toska, E.; Engelman, J.A.; Scaltriti, M. The Present and Future of PI3K Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy. Nat Cancer 2021, 2, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasan, N.; Cantley, L.C. At a Crossroads: How to Translate the Roles of PI3K in Oncogenic and Metabolic Signalling into Improvements in Cancer Therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022, 19, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França, G.V.A.; Schuler-Faccini, L.; Oliveira, W.K.; Henriques, C.M.P.; Carmo, E.H.; Pedi, V.D.; Nunes, M.L.; Castro, M.C.; Serruya, S.; Silveira, M.F.; et al. Congenital Zika Virus Syndrome in Brazil: A Case Series of the First 1501 Livebirths with Complete Investigation. The Lancet 2016, 388, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura da Silva, A.A.; Ganz, J.S.S.; Sousa, P. da S.; Doriqui, M.J.R.; Ribeiro, M.R.C.; Branco, M. dos R.F.C.; Queiroz, R.C. de S.; Pacheco, M. de J.T.; Vieira da Costa, F.R.; Silva, F. de S.; et al. Early Growth and Neurologic Outcomes of Infants with Probable Congenital Zika Virus Syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis 2016, 22, 1953–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, L.G. de; Altei, W.F.; Galan, A.; Bilić, P.; Guillemin, N.; Kuleš, J.; Horvatić, A.; Ribeiro, L.N. de M.; Paula, E. de; Pereira, V.B.R.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles in Infectious Diseases Caused by Protozoan Parasites in Buffaloes. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.G.; Choi, Y.Y.; Mo, S.J.; Kim, T.H.; Ha, J.H.; Hong, D.K.; Lee, H.; Park, S.D.; Shim, J.-J.; Lee, J.-L.; et al. Effect of Gut Microbiome-Derived Metabolites and Extracellular Vesicles on Hepatocyte Functions in a Gut-Liver Axis Chip. Nano Converg 2023, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhai, J.; Ma, J.; Chen, P.; Lin, W.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, C.; Wei, H. Melatonin-Primed Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Alleviated Neurogenic Erectile Dysfunction by Reversing Phenotypic Modulation. Adv Healthc Mater 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HOFFMAN, D.E.; JONSSON, P.; BYLESJÖ, M.; TRYGG, J.; ANTTI, H.; ERIKSSON, M.E.; MORITZ, T. Changes in Diurnal Patterns within the Populus Transcriptome and Metabolome in Response to Photoperiod Variation. Plant Cell Environ 2010, 33, 1298–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budzinski, I.G.F.; Moon, D.H.; Morosini, J.S.; Lindén, P.; Bragatto, J.; Moritz, T.; Labate, C.A. Integrated Analysis of Gene Expression from Carbon Metabolism, Proteome and Metabolome, Reveals Altered Primary Metabolism in Eucalyptus Grandis Bark, in Response to Seasonal Variation. BMC Plant Biol 2016, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, P.; Johansson, A.I.; Gullberg, J.; Trygg, J.; A, J.; Grung, B.; Marklund, S.; Sjöström, M.; Antti, H.; Moritz, T. High-Throughput Data Analysis for Detecting and Identifying Differences between Samples in GC/MS-Based Metabolomic Analyses. Anal Chem 2005, 77, 5635–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.; Wishart, D.S.; Xia, J. Using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 for Comprehensive and Integrative Metabolomics Data Analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2019, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeannin, P.; Chaze, T.; Giai Gianetto, Q.; Matondo, M.; Gout, O.; Gessain, A.; Afonso, P. V. Proteomic Analysis of Plasma Extracellular Vesicles Reveals Mitochondrial Stress upon HTLV-1 Infection. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guha, D.; Lorenz, D.R.; Misra, V.; Chettimada, S.; Morgello, S.; Gabuzda, D. Proteomic Analysis of Cerebrospinal Fluid Extracellular Vesicles Reveals Synaptic Injury, Inflammation, and Stress Response Markers in HIV Patients with Cognitive Impairment. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanelli, L.; Buratta, S.; Tancini, B.; Sagini, K.; Delo, F.; Porcellati, S.; Emiliani, C. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Viral Infection and Transmission. Vaccines (Basel) 2019, 7, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeone, P.; Bologna, G.; Lanuti, P.; Pierdomenico, L.; Guagnano, M.T.; Pieragostino, D.; Del Boccio, P.; Vergara, D.; Marchisio, M.; Miscia, S.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles as Signaling Mediators and Disease Biomarkers across Biological Barriers. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askeland, A.; Borup, A.; Østergaard, O.; Olsen, J. V.; Lund, S.M.; Christiansen, G.; Kristensen, S.R.; Heegaard, N.H.H.; Pedersen, S. Mass-Spectrometry Based Proteome Comparison of Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Methods: Comparison of ME-Kit, Size-Exclusion Chromatography, and High-Speed Centrifugation. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rojas, P.P.; Quiroz-García, E.; Monroy-Martínez, V.; Agredano-Moreno, L.T.; Jiménez-García, L.F.; Ruiz-Ordaz, B.H. Participation of Extracellular Vesicles from Zika-Virus-Infected Mosquito Cells in the Modification of Naïve Cells’ Behavior by Mediating Cell-to-Cell Transmission of Viral Elements. Cells 2020, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, L.E.; Garcia, G.; Contreras, D.; Gong, D.; Sun, R.; Arumugaswami, V. Zika Virus Mucosal Infection Provides Protective Immunity. J Virol 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallal, S.; Tűzesi, Á.; Grau, G.E.; Buckland, M.E.; Alexander, K.L. Understanding the Extracellular Vesicle Surface for Clinical Molecular Biology. J Extracell Vesicles 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedikter, B.J.; Bouwman, F.G.; Vajen, T.; Heinzmann, A.C.A.; Grauls, G.; Mariman, E.C.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Savelkoul, P.H.; Lopez-Iglesias, C.; Koenen, R.R.; et al. Ultrafiltration Combined with Size Exclusion Chromatography Efficiently Isolates Extracellular Vesicles from Cell Culture Media for Compositional and Functional Studies. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 15297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fialho, E.M.S.; Veras, E.M.; Jesus, C.M. de; Gomes, L.N.; Khouri, R.; Sousa, P.S.; Ribeiro, M.R.C.; Batista, R.F.L.; Costa, L.C.; Nascimento, F.R.F.; et al. Maternal Th17 Profile after Zika Virus Infection Is Involved in Congenital Zika Syndrome Development in Children. Viruses 2023, 15, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosthuizen, D.; Sturrock, E.D. Exploring the Impact of ACE Inhibition in Immunity and Disease. Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaviano, A.; Foo, A.S.C.; Lam, H.Y.; Yap, K.C.H.; Jacot, W.; Jones, R.H.; Eng, H.; Nair, M.G.; Makvandi, P.; Geoerger, B.; et al. PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling Transduction Pathway and Targeted Therapies in Cancer. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersahin, T.; Tuncbag, N.; Cetin-Atalay, R. The PI3K/AKT/MTOR Interactive Pathway. Mol Biosyst 2015, 11, 1946–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ersahin, T.; Tuncbag, N.; Cetin-Atalay, R. The PI3K/AKT/MTOR Interactive Pathway. Mol Biosyst 2015, 11, 1946–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michlmayr, D.; Kim, E.-Y.; Rahman, A.H.; Raghunathan, R.; Kim-Schulze, S.; Che, Y.; Kalayci, S.; Gümüş, Z.H.; Kuan, G.; Balmaseda, A.; et al. Comprehensive Immunoprofiling of Pediatric Zika Reveals Key Role for Monocytes in the Acute Phase and No Effect of Prior Dengue Virus Infection. Cell Rep 2020, 31, 107569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Sirohi, D.; Miller, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lu, H.; Xu, J.; Kuhn, R.J.; et al. Chemical Proteomics Tracks Virus Entry and Uncovers NCAM1 as Zika Virus Receptor. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatara, J.M.; Santi, L.; Beys-da-Silva, W.O. Proteome Alterations Promoted by Zika Virus Infection. In Zika Virus Biology, Transmission, and Pathology; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 307–317.

- Sun, X.; Hua, S.; Gao, C.; Blackmer, J.E.; Ouyang, Z.; Ard, K.; Ciaranello, A.; Yawetz, S.; Sax, P.E.; Rosenberg, E.S.; et al. Immune-Profiling of ZIKV-Infected Patients Identifies a Distinct Function of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells for Immune Cross-Regulation. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michlmayr, D.; Kim, E.-Y.; Rahman, A.H.; Raghunathan, R.; Kim-Schulze, S.; Che, Y.; Kalayci, S.; Gümüş, Z.H.; Kuan, G.; Balmaseda, A.; et al. Comprehensive Immunoprofiling of Pediatric Zika Reveals Key Role for Monocytes in the Acute Phase and No Effect of Prior Dengue Virus Infection. Cell Rep 2020, 31, 107569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobino, C.; Canta, M.; Fornaguera, C.; Borrós, S.; Cauda, V. Extracellular Vesicles and Their Current Role in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-H.; Cerione, R.A.; Antonyak, M.A. Extracellular Vesicles and Their Roles in Cancer Progression. In; 2021; pp. 143–170.

- Akhmerov, A.; Parimon, T. Extracellular Vesicles, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Reiter, R.J.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Ren, J. Extracellular Vesicles in Cardiovascular Diseases: From Pathophysiology to Diagnosis and Therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2023, 74, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, C.; Pu, Q.; Deng, X.; Lan, L.; Liang, H.; Song, X.; Wu, M. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Pathogenesis, Virulence Factors, Antibiotic Resistance, Interaction with Host, Technology Advances and Emerging Therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peregrino, E.S.; Castañeda-Casimiro, J.; Vázquez-Flores, L.; Estrada-Parra, S.; Wong-Baeza, C.; Serafín-López, J.; Wong-Baeza, I. The Role of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in the Immune Response to Pathogens, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzas, E.I. The Roles of Extracellular Vesicles in the Immune System. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Flores, V.; Romero, R.; Xu, Y.; Theis, K.R.; Arenas-Hernandez, M.; Miller, D.; Peyvandipour, A.; Bhatti, G.; Galaz, J.; Gershater, M.; et al. Maternal-Fetal Immune Responses in Pregnant Women Infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuberger, D.M.; Schuepbach, R.A. Protease-Activated Receptors (PARs): Mechanisms of Action and Potential Therapeutic Modulators in PAR-Driven Inflammatory Diseases. Thromb J 2019, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Tato, C.M.; Davis, M.M. How the Immune System Talks to Itself: The Varied Role of Synapses. Immunol Rev 2013, 251, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixson, A.C.; Dawson, T.R.; Di Vizio, D.; Weaver, A.M. Context-Specific Regulation of Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Cargo Selection. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023, 24, 454–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, P.D.; Morelli, A.E. Regulation of Immune Responses by Extracellular Vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol 2014, 14, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P.; Wright, S.S.; Rathinam, V.A. Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Immunity and Host Defense. Immunol Invest 2024, 53, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, T.; Sun, X.; Wu, C.; Yao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y. PROS1, a Clinical Prognostic Biomarker and Tumor Suppressor, Is Associated with Immune Cell Infiltration in Breast Cancer: A Bioinformatics Analysis Combined with Experimental Verification. Cell Signal 2023, 112, 110918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busatto, S.; Morad, G.; Guo, P.; Moses, M.A. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in the Physiological and Pathological Regulation of the Blood–Brain Barrier. FASEB Bioadv 2021, 3, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, T.K.J.B.; Fraser, M. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in the Developing Brain: Current Perspective and Promising Source of Biomarkers and Therapy for Perinatal Brain Injury. Front Neurosci 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, Y.; Cai, Y.; Lin, J.; Ma, L.; Han, H.; Li, F. Advancement in Modulation of Brain Extracellular Space and Unlocking Its Potential for Intervention of Neurological Diseases. Med-X 2024, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding Light on the Cell Biology of Extracellular Vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltarelli, V.A.; Alves de Souza, R.W.; Miyauchi, K.; Hauser, C.J.; Otterbein, L.E. Heme: The Lord of the Iron Ring. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mense, S.M.; Zhang, L. Heme: A Versatile Signaling Molecule Controlling the Activities of Diverse Regulators Ranging from Transcription Factors to MAP Kinases. Cell Res 2006, 16, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis-Guardiola, K.; Soule, J.; Clubb, R. Methods for the Extraction of Heme Prosthetic Groups from Hemoproteins. Bio Protoc 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandu, R.; Oh, J.W.; Kim, K.P. Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteome Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Roles in Cancer Biology. Exp Mol Med 2019, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Oh, I.; Lee, N.; Lee, K.; Yoon, Y.J.; Lee, E.Y.; Kim, B.; Kim, D. Integrating Cell-free Biosyntheses of Heme Prosthetic Group and Apoenzyme for the Synthesis of Functional P450 Monooxygenase. Biotechnol Bioeng 2013, 110, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallejo, M.C.; Sarkar, S.; Elliott, E.C.; Henry, H.R.; Powell, S.M.; Diaz Ludovico, I.; You, Y.; Huang, F.; Payne, S.H.; Ramanadham, S.; et al. A Proteomic Meta-Analysis Refinement of Plasma Extracellular Vesicles. Sci Data 2023, 10, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-J.; Huang, Y.-N.; Lu, Y.-B.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, P.-H.; Huang, J.-S.; Yang, W.; Chiang, T.-Y.; Hsieh, H.-S.; Chung, W.-H.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Serum Extracellular Vesicles from Biliary Tract Infection Patients to Identify Novel Biomarkers. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badosa, C.; Roldán, M.; Fernández-Irigoyen, J.; Santamaria, E.; Jimenez-Mallebrera, C. Proteomic and Functional Characterisation of Extracellular Vesicles from Collagen VI Deficient Human Fibroblasts Reveals a Role in Cell Motility. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 14622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, B.; Ocansey, D.K.W.; Xu, W.; Qian, H. Extracellular Vesicles: A Bright Star of Nanomedicine. Biomaterials 2021, 269, 120467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soloveva, N.; Novikova, S.; Farafonova, T.; Tikhonova, O.; Zgoda, V. Proteomic Signature of Extracellular Vesicles Associated with Colorectal Cancer. Molecules 2023, 28, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barouch-Bentov, R.; Neveu, G.; Xiao, F.; Beer, M.; Bekerman, E.; Schor, S.; Campbell, J.; Boonyaratanakornkit, J.; Lindenbach, B.; Lu, A.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus Proteins Interact with the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) Machinery via Ubiquitination To Facilitate Viral Envelopment. mBio 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillemin, A.; Kumar, A.; Wencker, M.; Ricci, E.P. Shaping the Innate Immune Response Through Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Gene Expression Mediated by RNA-Binding Proteins. Front Immunol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Cao, X. Cellular and Molecular Regulation of Innate Inflammatory Responses. Cell Mol Immunol 2016, 13, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medjeral-Thomas, N.R.; Lomax-Browne, H.J.; Beckwith, H.; Willicombe, M.; McLean, A.G.; Brookes, P.; Pusey, C.D.; Falchi, M.; Cook, H.T.; Pickering, M.C. Circulating Complement Factor H–Related Proteins 1 and 5 Correlate with Disease Activity in IgA Nephropathy. Kidney Int 2017, 92, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yang, W.; Tong, Y.; Sun, M.; Quan, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, Z.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Integrative Proteomics and Metabolomics Study Reveal Enhanced Immune Responses by COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Shot against Omicron SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J Med Virol 2023, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, S.M.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Ni, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Huang, X.; Mo, L.; Li, J.; Lee, B.; et al. A Multi-Omics Investigation of the Composition and Function of Extracellular Vesicles along the Temporal Trajectory of COVID-19. Nat Metab 2021, 3, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Yao, F.; Yin, Y.; Wu, C.; Xia, D.; Zhang, K.; Jin, Z.; Liu, X.; He, J.; Zhang, Z. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Immune Cells: Role in Tumor Therapy. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 133, 112150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Xu, Y.; Liu, N.; Lv, D.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jin, X.; Xiao, M.; Lavillette, D.; Zhong, J.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Zika Virus-infected Cells Display Viral E Protein That Binds ZIKV-neutralizing Antibodies to Prevent Infection Enhancement. EMBO J 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fikatas, A.; Dehairs, J.; Noppen, S.; Doijen, J.; Vanderhoydonc, F.; Meyen, E.; Swinnen, J. V.; Pannecouque, C.; Schols, D. Deciphering the Role of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from ZIKV-Infected HcMEC/D3 Cells on the Blood–Brain Barrier System. Viruses 2021, 13, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Kodidela, S.; Tadrous, E.; Cory, T.J.; Walker, C.M.; Smith, A.M.; Mukherjee, A.; Kumar, S. Extracellular Vesicles in Viral Replication and Pathogenesis and Their Potential Role in Therapeutic Intervention. Viruses 2020, 12, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majowicz, S.A.; Narayanan, A.; Moustafa, I.M.; Bator, C.M.; Hafenstein, S.L.; Jose, J. Zika Virus M Protein Latches and Locks the E Protein from Transitioning to an Immature State after PrM Cleavage. npj Viruses 2023, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo-da-Silva, J.; Santiago, V.F.; Rosa-Fernandes, L.; Marinho, C.R.F.; Palmisano, G. Protein Glycosylation in Extracellular Vesicles: Structural Characterization and Biological Functions. Mol Immunol 2021, 135, 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smelik, M.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Loscalzo, J.; Sysoev, O.; Mahmud, F.; Mansour Aly, D.; Benson, M. An Interactive Atlas of Genomic, Proteomic, and Metabolomic Biomarkers Promotes the Potential of Proteins to Predict Complex Diseases. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Takeuchi, T.; Takeda, A.; Mochizuki, H.; Nagai, Y. Comparison of Serum and Plasma as a Source of Blood Extracellular Vesicles: Increased Levels of Platelet-Derived Particles in Serum Extracellular Vesicle Fractions Alter Content Profiles from Plasma Extracellular Vesicle Fractions. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0270634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher-Schuh, A.; Bieger, A.; Borelli, W. V.; Portley, M.K.; Awad, P.S.; Bandres-Ciga, S. Advances in Proteomic and Metabolomic Profiling of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Neurol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakelyan, A.; Fitzgerald, W.; Zicari, S.; Vanpouille, C.; Margolis, L. Extracellular Vesicles Carry HIV Env and Facilitate Hiv Infection of Human Lymphoid Tissue. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyster, J.G.; Allen, C.D.C. B Cell Responses: Cell Interaction Dynamics and Decisions. Cell 2019, 177, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierson, T.C.; Diamond, M.S. The Emergence of Zika Virus and Its New Clinical Syndromes. Nature 2018, 560, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanetti, M.; Pereira, L.A.; Adelino, T.É.R.; Fonseca, V.; Xavier, J.; de Araújo Fabri, A.; Slavov, S.N.; da Silva Lemos, P.; de Almeida Marques, W.; Kashima, S.; et al. A Retrospective Overview of Zika Virus Evolution in the Midwest of Brazil. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.; Hwang, K.-K.; Miller, A.S.; Jones, R.L.; Lopez, C.A.; Dulson, S.J.; Giuberti, C.; Gladden, M.A.; Miller, I.; Webster, H.S.; et al. A Zika Virus-Specific IgM Elicited in Pregnancy Exhibits Ultrapotent Neutralization. Cell 2022, 185, 4826–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.-Y.C.; Dondelinger, F.; Schoof, E.M.; Georg, B.; Lu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hannibal, J.; Fahrenkrug, J.; Kjaer, M. Circadian Regulation of Protein Cargo in Extracellular Vesicles. Sci Adv 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebrowska, A.; Jelonek, K.; Mondal, S.; Gawin, M.; Mrowiec, K.; Widłak, P.; Whiteside, T.; Pietrowska, M. Proteomic and Metabolomic Profiles of T Cell-Derived Exosomes Isolated from Human Plasma. Cells 2022, 11, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bludau, I.; Aebersold, R. Proteomic and Interactomic Insights into the Molecular Basis of Cell Functional Diversity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greening, D.W.; Xu, R.; Gopal, S.K.; Rai, A.; Simpson, R.J. Proteomic Insights into Extracellular Vesicle Biology – Defining Exosomes and Shed Microvesicles. Expert Rev Proteomics 2017, 14, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, I.; Vo, T.; Paudel, K.; Wen, X.; Gupta, R.; Kesimer, M.; Patial, S.; Saini, Y. Vesicular and Extravesicular Protein Analyses from the Airspaces of Ozone-Exposed Mice Revealed Signatures Associated with Mucoinflammatory Lung Disease. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 23203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier-Soelch, J.; Mayr-Buro, C.; Juli, J.; Leib, L.; Linne, U.; Dreute, J.; Papantonis, A.; Schmitz, M.L.; Kracht, M. Monitoring the Levels of Cellular NF-ΚB Activation States. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J. NF-ΚB in Biology and Targeted Therapy: New Insights and Translational Implications. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nix, C.; Fillet, M. New Insights into Extracellular Vesicles of Clinical and Therapeutic Interest Using Proteomic Mass Spectrometry Approaches. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 178, 117823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denolly, S.; Stukalov, A.; Barayeu, U.; Rosinski, A.N.; Kritsiligkou, P.; Joecks, S.; Dick, T.P.; Pichlmair, A.; Bartenschlager, R. Zika Virus Remodelled ER Membranes Contain Proviral Factors Involved in Redox and Methylation Pathways. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 8045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, R.G.; Lim, X.N.; Ng, W.C.; Sim, A.Y.L.; Poh, H.X.; Shen, Y.; Lim, S.Y.; Sundstrom, K.B.; Sun, X.; Aw, J.G.; et al. Structure Mapping of Dengue and Zika Viruses Reveals Functional Long-Range Interactions. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MIRZAA, G.M.; RIVIÈRE, J.; DOBYNS, W.B. Megalencephaly Syndromes and Activating Mutations in the PI3K-AKT Pathway: MPPH and MCAP. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2013, 163, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.Y. Roles of MTOR Signaling in Brain Development. Exp Neurobiol 2015, 24, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahane, S.D.; Hellbach, N.; Prentzell, M.T.; Weise, S.C.; Vezzali, R.; Kreutz, C.; Timmer, J.; Krieglstein, K.; Thedieck, K.; Vogel, T. PI3K-p110-alpha-subtype Signalling Mediates Survival, Proliferation and Neurogenesis of Cortical Progenitor Cells via Activation of <scp>mTORC</Scp> 2. J Neurochem 2014, 130, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Dai, Q.; Yang, R.; Duan, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Haybaeck, J.; Yang, Z. A Review: PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling Pathway and Its Regulated Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factors May Be a Potential Therapeutic Target in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; Yao, Q.; Ba, J.; Luan, J.; Zhao, P.; Qin, Z.; Qi, Z. MTOR Signaling Regulates Zika Virus Replication Bidirectionally through Autophagy and Protein Translation. J Med Virol 2023, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, T.F. PI3K/Akt: Getting It Right Matters. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6473–6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.K.; Shin, O.S. Zika Virus Modulates Mitochondrial Dynamics, Mitophagy, and Mitochondria-Derived Vesicles to Facilitate Viral Replication in Trophoblast Cells. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirohi, D.; Kuhn, R.J. Zika Virus Structure, Maturation, and Receptors. J Infect Dis 2017, 216, S935–S944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.E.; Rossignol, E.D.; Chang, D.; Zaia, J.; Forrester, I.; Raja, K.; Winbigler, H.; Nicastro, D.; Jackson, W.T.; Bullitt, E. Complexity and Ultrastructure of Infectious Extracellular Vesicles from Cells Infected by Non-Enveloped Virus. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 7939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaturro, P.; Stukalov, A.; Haas, D.A.; Cortese, M.; Draganova, K.; Płaszczyca, A.; Bartenschlager, R.; Götz, M.; Pichlmair, A. An Orthogonal Proteomic Survey Uncovers Novel Zika Virus Host Factors. Nature 2018, 561, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- York, S.B.; Sun, L.; Cone, A.S.; Duke, L.C.; Cheerathodi, M.R.; Meckes, D.G. Zika Virus Hijacks Extracellular Vesicle Tetraspanin Pathways for Cell-to-Cell Transmission. mSphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Hui, L.; Nie, Y.; Tefsen, B.; Wu, Y. ZIKV Viral Proteins and Their Roles in Virus-Host Interactions. Sci China Life Sci 2021, 64, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A.Y.; Gustin, A.; Newhouse, D.; Gale, M. Viral Protein Accumulation of Zika Virus Variants Links with Regulation of Innate Immunity for Differential Control of Viral Replication, Spread, and Response to Interferon. J Virol 2023, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergadi, E.; Ieronymaki, E.; Lyroni, K.; Vaporidi, K.; Tsatsanis, C. Akt Signaling Pathway in Macrophage Activation and M1/M2 Polarization. The Journal of Immunology 2017, 198, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.J.; Komarasamy, T.V.; Adnan, N.A.A.; James, W.; RMT Balasubramaniam, V. Hide and Seek: The Interplay Between Zika Virus and the Host Immune Response. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).