Submitted:

09 January 2024

Posted:

11 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse Models

2.2. Intra-Peritoneal Glucose Tolerance Test (ipGTT)

2.3. Hematoxylin-eosin staining

2.4. Extracellular Vesicles isolation

2.5. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (Nanosight)

2.6. Protein quantification

2.7. Nano-LC-MS/MS analysis

2.8. Database Search

2.9. Proteomic functional enrichment analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

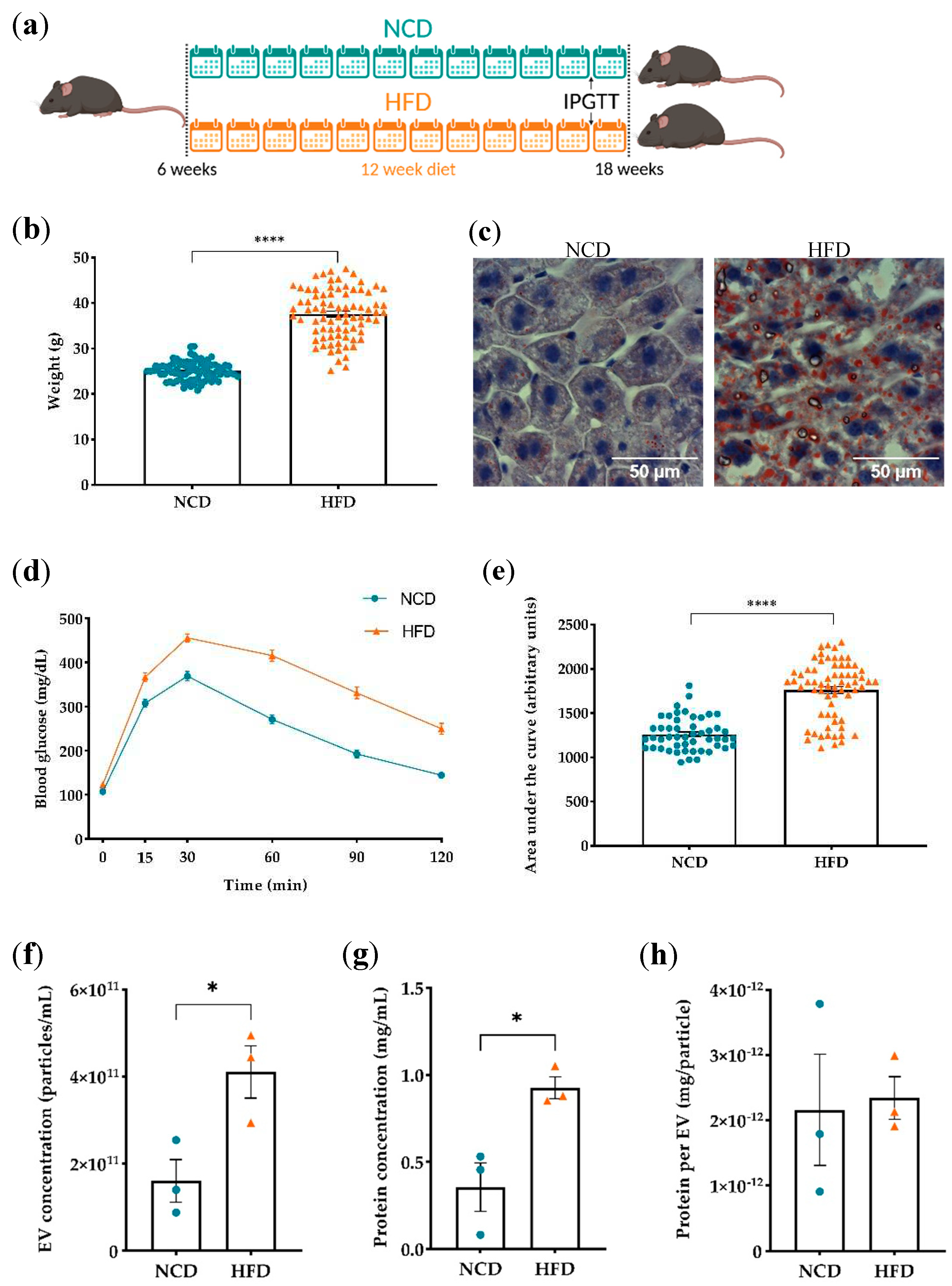

3.1. Evaluation of diet-induced obesity’s effects on plasma derived EVs

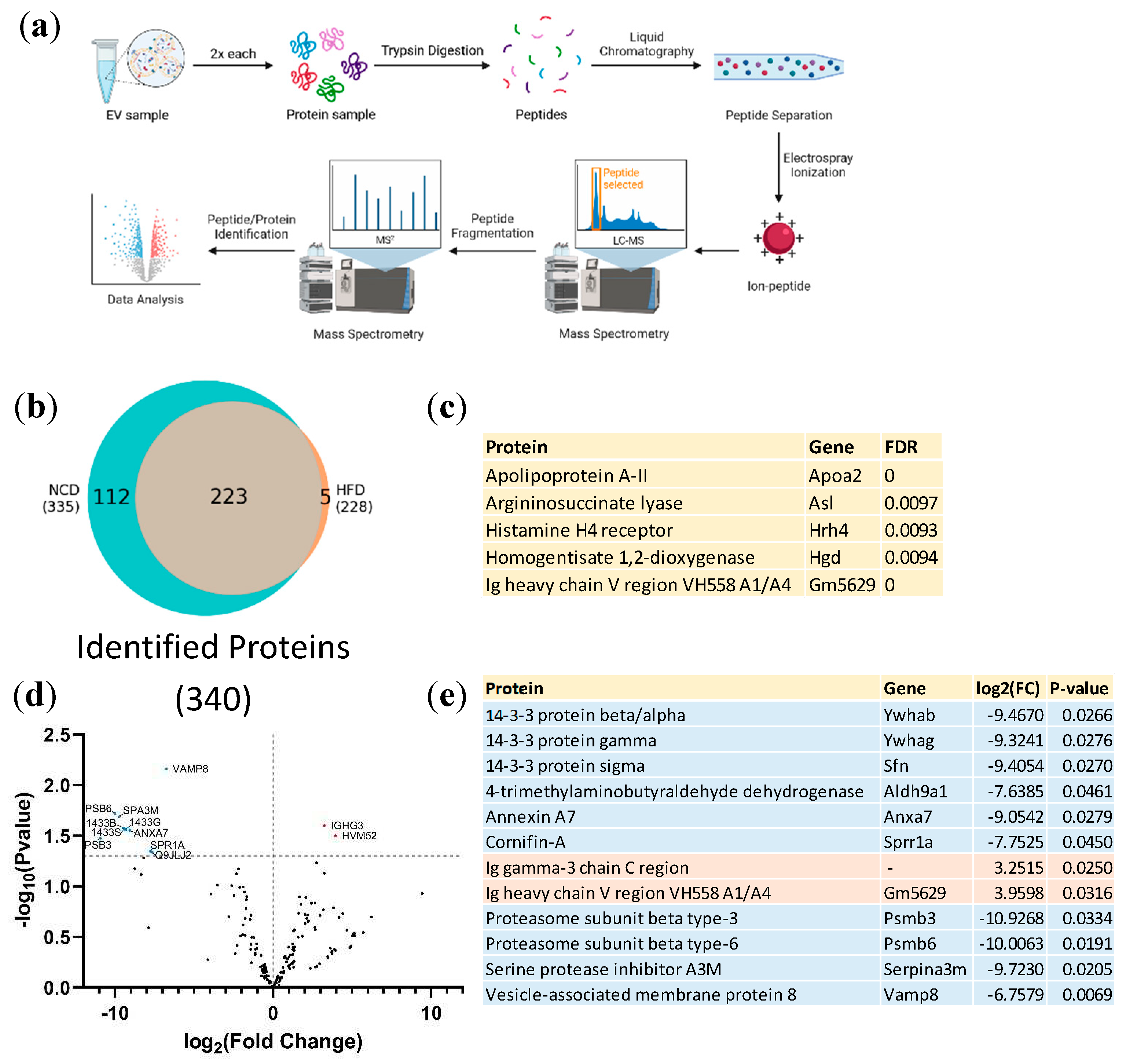

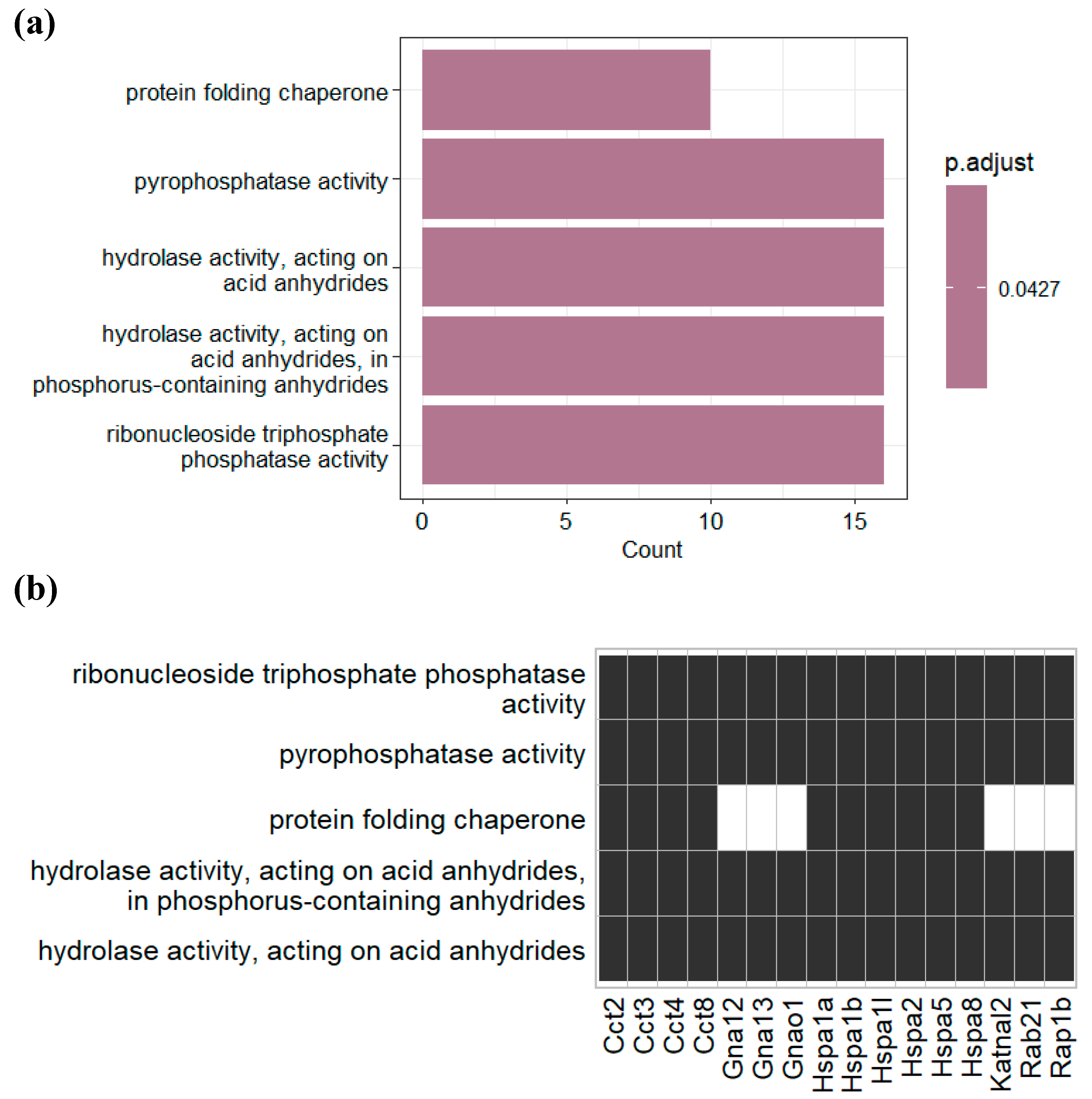

3.2. Proteomic analysis of plasma derived EVs

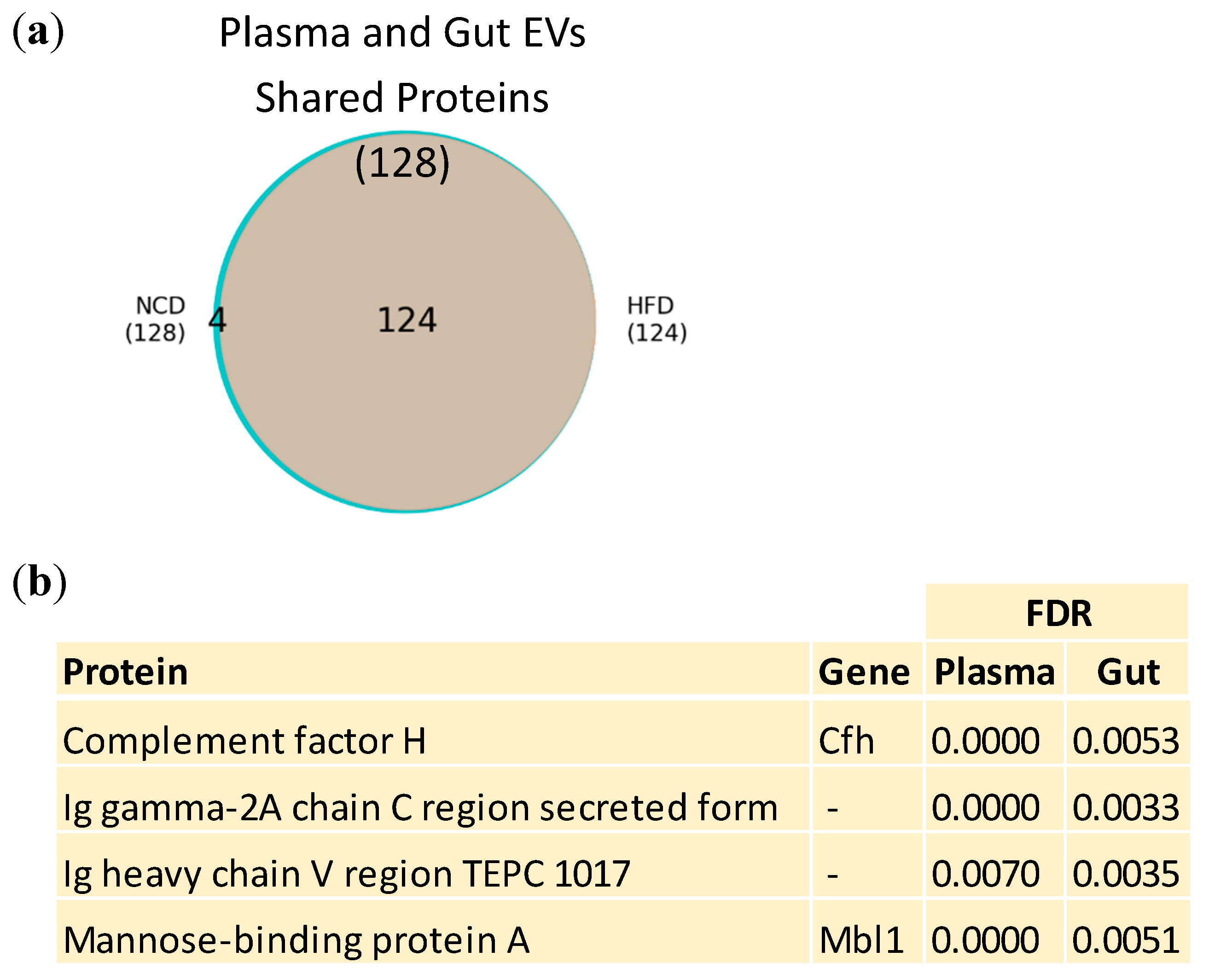

3.3. Plasma and Gut EVs crosstalk

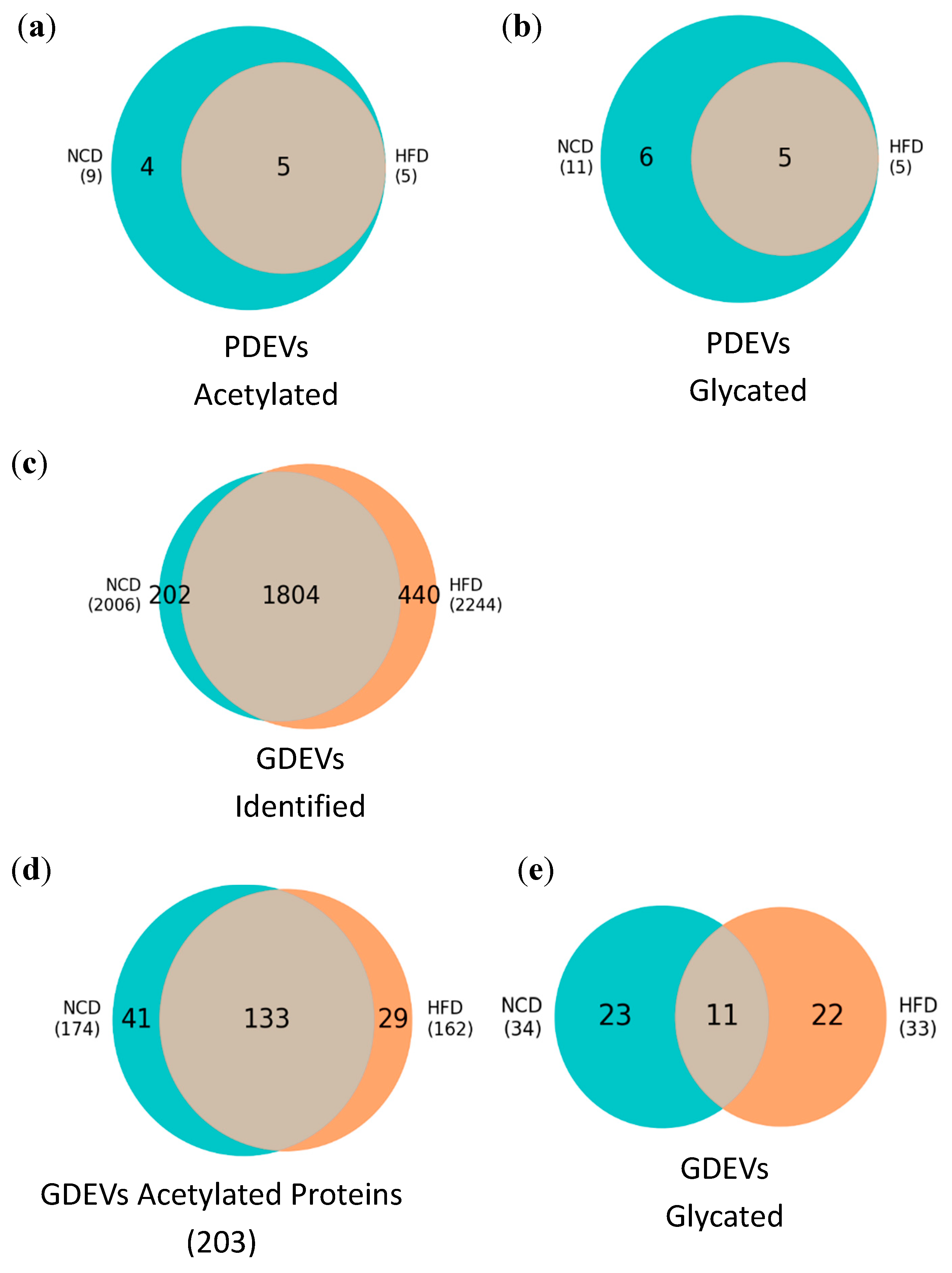

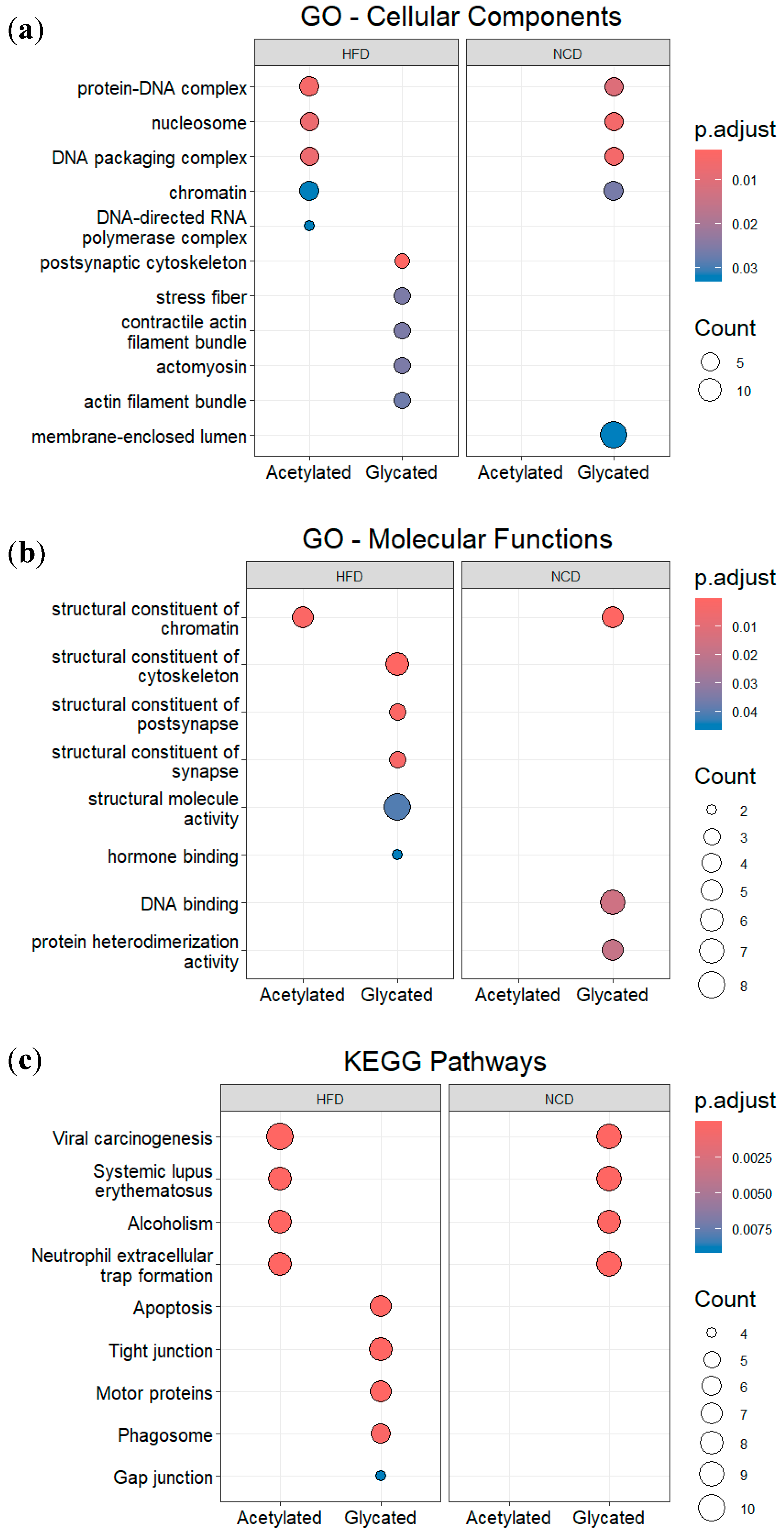

3.4. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) in plasma and gut EVs proteins

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization World Obesity Day 2022 – Accelerating Action to Stop Obesity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-03-2022-world-obesity-day-2022-accelerating-action-to-stop-obesity (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Bastías-Pérez, M.; Serra, D.; Herrero, L. Dietary Options for Rodents in the Study of Obesity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.O.; Melanson, E.L.; Wyatt, H.T. Dietary Fat Intake and Regulation of Energy Balance: Implications for Obesity. J Nutr 2000, 130, 284S–288S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jéquier, E. Pathways to Obesity. Int J Obes 2002, 26, S12–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, S.; Robinson, T. Fats and Food Intake. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2003, 6, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losacco, M.C.; de Almeida, C.F.T.; Hijo, A.H.T.; Bargi-Souza, P.; Gama, P.; Nunes, M.T.; Goulart-Silva, F. High-Fat Diet Affects Gut Nutrients Transporters in Hypo and Hyperthyroid Mice by PPAR-a Independent Mechanism. Life Sci 2018, 202, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B. Globalization of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoelson, S.E.; Herrero, L.; Naaz, A. Obesity, Inflammation, and Insulin Resistance. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sánchez, A.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Bautista, M.; Esquivel-Soto, J.; Morales-González, Á.; Esquivel-Chirino, C.; Durante-Montiel, I.; Sánchez-Rivera, G.; Valadez-Vega, C.; Morales-González, J.A. Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Obesity. Int J Mol Sci 2011, 12, 3117–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in Inflammation and Metabolic Disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, F.; Villalobos-Labra, R.; Sobrevia, B.; Toledo, F.; Sobrevia, L. Extracellular Vesicles in Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus. Mol Aspects Med 2018, 60, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Contreras, M.; Shah, S.H.; Tamayo, A.; Robbins, P.D.; Golberg, R.B.; Mendez, A.J.; Ricordi, C. Plasma-Derived Exosome Characterization Reveals a Distinct MicroRNA Signature in Long Duration Type 1 Diabetes. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.C.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Extracellular Vesicles in Metabolic Syndrome. Circ Res 2017, 120, 1674–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Biogenesis, Secretion, and Intercellular Interactions of Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The Biology, Function, and Biomedical Applications of Exosomes. Science (1979) 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, H.; Drummen, G.; Mathivanan, S. Focus on Extracellular Vesicles: Introducing the Next Small Big Thing. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding Light on the Cell Biology of Extracellular Vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, N.; Azzimato, V.; Choudhury, R.P.; Aouadi, M. Extracellular Vesicles in Metabolic Disease. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 2179–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang-Doran, I.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Vidal-Puig, A. Extracellular Vesicles: Novel Mediators of Cell Communication In Metabolic Disease. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2017, 28, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-J.; Fang, Q.-H.; Liu, M.-L.; Lin, J.-N. Current Understanding of the Role of Adipose-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Metabolic Homeostasis and Diseases: Communication from the Distance between Cells/Tissues. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7422–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswad, H.; Forterre, A.; Wiklander, O.P.B.; Vial, G.; Danty-Berger, E.; Jalabert, A.; Lamazière, A.; Meugnier, E.; Pesenti, S.; Ott, C.; et al. Exosomes Participate in the Alteration of Muscle Homeostasis during Lipid-Induced Insulin Resistance in Mice. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 2155–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, S.-Y.; Leng, Y.; Wang, Z.-X.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Wen, T.; Gong, H.-Z.; Hong, A.; Ma, Y. Exosomal Transfer of Obesity Adipose Tissue for Decreased MiR-141-3p Mediate Insulin Resistance of Hepatocytes. Int J Biol Sci 2019, 15, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalabert, A.; Vial, G.; Guay, C.; Wiklander, O.P.B.; Nordin, J.Z.; Aswad, H.; Forterre, A.; Meugnier, E.; Pesenti, S.; Regazzi, R.; et al. Exosome-like Vesicles Released from Lipid-Induced Insulin-Resistant Muscles Modulate Gene Expression and Proliferation of Beta Recipient Cells in Mice. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Dong, T.; Chen, T.; Sun, J.; Luo, J.; He, J.; Wei, L.; Zeng, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; et al. Hepatic Exosome-Derived MiR-130a-3p Attenuates Glucose Intolerance via Suppressing PHLPP2 Gene in Adipocyte. Metabolism 2020, 103, 154006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Du, H.; Wei, S.; Feng, L.; Li, J.; Yao, F.; Zhang, M.; Hatch, G.M.; Chen, L. Adipocyte-Derived Exosomal MiR-27a Induces Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle Through Repression of PPARγ. Theranostics 2018, 8, 2171–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Poliakov, A.; Hardy, R.W.; Clements, R.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhuang, X.; et al. Ad-ipose Tissue Exosome-Like Vesicles Mediate Activation of Macrophage-Induced Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2498–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranendonk, M.E.G.; Visseren, F.L.J.; van Balkom, B.W.M.; Nolte-’t Hoen, E.N.M.; van Herwaarden, J.A.; de Jager, W.; Schipper, H.S.; Brenkman, A.B.; Verhaar, M.C.; Wauben, M.H.M.; et al. Human Adipocyte Extracellular Vesicles in Re-ciprocal Signaling between Adipocytes and Macrophages. Obesity 2014, 22, 1296–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, F.; Villalobos-Labra, R.; Sobrevia, B.; Toledo, F.; Sobrevia, L. Extracellular Vesicles in Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus. Mol Aspects Med 2018, 60, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaño, C.; Kalko, S.; Novials, A.; Párrizas, M. Obesity-Associated Exosomal MiRNAs Modulate Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 12158–12163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Riopel, M.; Bandyopadhyay, G.; Dong, Y.; Birmingham, A.; Seo, J.B.; Ofrecio, J.M.; Wollam, J.; Hernan-dez-Carretero, A.; Fu, W.; et al. Adipose Tissue Macrophage-Derived Exosomal MiRNAs Can Modulate In Vivo and In Vitro Insulin Sensitivity. Cell 2017, 171, 372–384e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, I.; Machado de Oliveira, R.; Carvalho, A.S.; Teshima, A.; Beck, H.C.; Matthiesen, R.; Costa-Silva, B.; Macedo, M.P. Messages from the Small Intestine Carried by Extracellular Vesicles in Prediabetes: A Proteomic Portrait. J Proteome Res 2022, 21, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, D.M.; Rasmussen, B.A.; Côté, C.D.; Jackson, V.M.; Lam, T.K.T. Nutrient-Sensing Mechanisms in the Gut as Therapeutic Targets for Diabetes. Diabetes 2013, 62, 3005–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, M.; Li, Z.; You, H.; Rodrigues, R.; Jump, D.B.; Morgun, A.; Shulzhenko, N. Role of Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetes Pathophysiology. EBioMedicine 2020, 51, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, S.S.; Sandoval, D.A.; Seeley, R.J. The Physiology and Molecular Underpinnings of the Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Obesity and Diabetes. Annu Rev Physiol 2017, 79, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareek, M.; Schauer, P.R.; Kaplan, L.M.; Leiter, L.A.; Rubino, F.; Bhatt, D.L. Metabolic Surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 71, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HILLYER, R.; SULLIVAN, T.; CHRIST, K.; HODARKAR, A.; HODGE, M.B. 2117-P: Biomarkers Isolated from Extracellular Vesicles Prior to Bariatric Surgery May Be Associated with Postoperative Resolution of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2019, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, N.; Coelho, I.C.; Patarrão, R.S.; Almeida, J.I.; Penha-Gonçalves, C.; Macedo, M.P. How Inflammation Impinges on NAFLD: A Role for Kupffer Cells. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, D.W.; Noren Hooten, N.; Eitan, E.; Green, J.; Mode, N.A.; Bodogai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lehrmann, E.; Zonderman, A.B.; Biragyn, A.; et al. Altered Extracellular Vesicle Concentration, Cargo, and Function in Diabetes. Diabetes 2018, 67, 2377–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eguchi, A.; Lazic, M.; Armando, A.M.; Phillips, S.A.; Katebian, R.; Maraka, S.; Quehenberger, O.; Sears, D.D.; Feldstein, A.E. Circulating Adipocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are Novel Markers of Metabolic Stress. J Mol Med 2016, 94, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, T.; Horigome, H.; Tanaka, K.; Nakata, Y.; Ohkawara, K.; Katayama, Y.; Matsui, A. Impact of Weight Reduction on Production of Platelet-Derived Microparticles and Fibrinolytic Parameters in Obesity. Thromb Res 2007, 119, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanian, A.; Bourguignat, L.; Hennou, S.; Coupaye, M.; Hajage, D.; Salomon, L.; Alessi, M.-C.; Msika, S.; de Prost, D. Microparticle Increase in Severe Obesity: Not Related to Metabolic Syndrome and Unchanged after Massive Weight Loss. Obesity 2013, 21, 2236–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campello, E.; Zabeo, E.; Radu, C.M.; Spiezia, L.; Foletto, M.; Prevedello, L.; Gavasso, S.; Bulato, C.; Vettor, R.; Simioni, P. Dynamics of Circulating Microparticles in Obesity after Weight Loss. Intern Emerg Med 2016, 11, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocks, B.; Zierath, J.R. Post-Translational Modifications: The Signals at the Intersection of Exercise, Glucose Uptake, and Insulin Sensitivity. Endocr Rev 2022, 43, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, M.; Geng, M.; Chen, S.; Little, P.J.; Xu, S.; Weng, J. Targeting Protein Modifications in Metabolic Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms and Targeted Therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wei, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Song, M.; Mi, J.; Yang, X.; Tian, G. Regulation of Insulin Secretion by the Post-Translational Modifications. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterich, I.A.; Lawton, A.J.; Peng, Y.; Yu, Q.; Rhoads, T.W.; Overmyer, K.A.; Cui, Y.; Armstrong, E.A.; Howell, P.R.; Burhans, M.S.; et al. Acetyl-CoA Flux Regulates the Proteome and Acetyl-Proteome to Maintain Intracellular Metabolic Crosstalk. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maessen, D.E.M.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Schalkwijk, C.G. The Role of Methylglyoxal and the Glyoxalase System in Diabetes and Other Age-Related Diseases. Clin Sci 2015, 128, 839–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, K.J.; Zhang, H.; Katsyuba, E.; Auwerx, J. Protein Acetylation in Metabolism — Metabolites and Cofactors. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016, 12, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.T.; Workman, J.L. Introducing the Acetylome. Nat Biotechnol 2009, 27, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Suttapitugsakul, S.; Xiao, H.; Wu, R. Comprehensive Analysis of Protein Glycation Reveals Its Potential Impacts on Protein Degradation and Gene Expression in Human Cells. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2019, 30, 2480–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessoa Rodrigues, C.; Chatterjee, A.; Wiese, M.; Stehle, T.; Szymanski, W.; Shvedunova, M.; Akhtar, A. Histone H4 Lysine 16 Acetylation Controls Central Carbon Metabolism and Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, X.; Yang, P.; Li, Z. Acetylation Modification Regulates GRP78 Secretion in Colon Cancer Cells. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 30406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, A.; Fairlie, D.P.; Brown, L. Lysine Acetylation in Obesity, Diabetes and Metabolic Disease. Immunol Cell Biol 2012, 90, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrob, O.A.; Sankaralingam, S.; Ma, C.; Wagg, C.S.; Fillmore, N.; Jaswal, J.S.; Sack, M.N.; Lehner, R.; Gupta, M.P.; Mi-chelakis, E.D.; et al. Obesity-Induced Lysine Acetylation Increases Cardiac Fatty Acid Oxidation and Impairs Insulin Signalling. Cardiovasc Res 2014, 103, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, A.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Acetylation Control of Cardiac Fatty Acid β-Oxidation and Energy Metabolism in Obesity, Diabetes, and Heart Failure. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2016, 1862, 2211–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Gu, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, C. Protein Acetylation: A Novel Modus of Obesity Regulation. J Mol Med 2021, 99, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, N.; Thornalley, P.J. Glycation Research in Amino Acids: A Place to Call Home. Amino Acids 2012, 42, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twarda-Clapa, A.; Olczak, A.; Białkowska, A.M.; Koziołkiewicz, M. Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs): Formation, Chemistry, Classification, Receptors, and Diseases Related to AGEs. Cells 2022, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengstie, M.A.; Chekol Abebe, E.; Behaile Teklemariam, A.; Tilahun Mulu, A.; Agidew, M.M.; Teshome Azezew, M.; Zewde, E.A.; Agegnehu Teshome, A. Endogenous Advanced Glycation End Products in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Diabetic Complications. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R.; Augé, N.; Pamplona, R.; Portero-Otín, M. Hyperglycemia and Glycation in Diabetic Complications. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009, 11, 3071–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Gaglia, J.L.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; et al. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S19–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Mann, M. MaxQuant Enables High Peptide Identification Rates, Individualized p.p.b.-Range Mass Accuracies and Proteome-Wide Protein Quantification. Nat Biotechnol 2008, 26, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.S.; Ribeiro, H.; Voabil, P.; Penque, D.; Jensen, O.N.; Molina, H.; Matthiesen, R. Global Mass Spectrometry and Transcriptomics Array Based Drug Profiling Provides Novel Insight into Glucosamine Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics 2014, 13, 3294–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A Universal Enrichment Tool for Interpreting Omics Data. Innovation 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundgren, D.H.; Hwang, S.-I.; Wu, L.; Han, D.K. Role of Spectral Counting in Quantitative Proteomics. Expert Rev Pro-teomics 2010, 7, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanhüusser, B.; Busse, D.; Li, N.; Dittmar, G.; Schuchhardt, J.; Wolf, J.; Chen, W.; Selbach, M. Global Quantification of Mammalian Gene Expression Control. Nature 2011, 473, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-Sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, e47–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E.I.; Weng, S.; Gollub, J.; Jin, H.; Botstein, D.; Cherry, J.M.; Sherlock, G. GO::TermFinder - Open Source Software for Accessing Gene Ontology Information and Finding Significantly Enriched Gene Ontology Terms Associated with a List of Genes. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 3710–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology. Nat Genet 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksander, S.A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.M.; Drabkin, H.J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N.L.; Hill, D.P.; et al. The Gene Ontology Knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; 2000; Vol. 28.

- Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the Origin and Evolution of Cellular Organisms. Protein Science 2019, 28, 1947–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for Taxonomy-Based Analysis of Pathways and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D587–D592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noren Hooten, N.; Evans, M.K. Extracellular Vesicles as Signaling Mediators in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2020, 318, C1189–C1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).