1. Introduction

The Atacama Desert, have substantial deposits of bischofite mineral (MgCl2·6H2O) in a form of magnesium chloride recovery from solar evaporation process used for lithium recovery. The recovery of bischofite in the Atacama Desert involves mining these subterranean deposits. Bischofite mineral is notably found in the Atacama Desert. This mineral is present in the well brine located in the altitude places.

The electrochemical stability of electrodes in water splitting process is essential for ensuring the long-term efficiency and effectiveness of HER-based energy systems. Other oxides with different valence states, such as Mn

3O

4 and Mn

2O

3 are also possible cathodic materials candidates. Mn

2O

3 has generated interest because of its high theoretical specific capacity and energy density formed α- Mn

2O

3 between 500 to 800°C [

2] and forming ternary oxides as Mn

2O

3 [

3,

4,

5]. The family of MnO

2 is characterized by a variety of polymorphs with both open (with tunnels) and laminar structures of α-MnO

2 as hollandite, todorokite, and birnessite [

6]. Mn

2O

3 powder offers significant advantages in terms of cost-effectiveness and abundance compared to traditional noble metal catalysts, where the use of abundant and affordable materials for HER catalysis is essential for promoting large-scale hydrogen production and making it economically viable. Mn

2O

3 powder presents an opportunity to address the cost and availability concerns associated with noble metal catalysts, thereby accelerating the adoption of hydrogen as a clean and sustainable energy carrier. The interaction between the Mg and Mn powder plays a significant role in the HER activity and selectivity during cathodic subprocess. Understanding the structural aspects of Mn

2O

3 powder and its correlation with catalytic performances is crucial for further optimizing the properties and tailoring it for specific applications. Furthermore, Mn

2O

3 powder demonstrates excellent performance not only in the HER but also in other important electrochemical reactions, such as the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) [

7]. However, currently there is a lack of plausible models that accurately describe the electrochemical and oxidation parameters during the mechanisms. Its versatility and multifunctionality make it a valuable candidate for integration into various renewable energy conversion and storage devices, including water electrolyzes and fuel cells. The ability to perform multiple electrochemical reactions with high efficiency further highlights the potential of Mn

2O

3 powder as a versatile catalyst for clean energy technologies.

This manuscript presents pioneering insights into the utilization of Mn2O3 powder as an electrocatalyst for the HER, and ORR mechanisms using natural Bischofite from Atacama Desert. The study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the electrochemical behavior exhibited by Mn2O3 powder electrodes during direct saline water splitting processes. This is performed in an artificial 0.5 M MgCl2 and 0.5 M of natural Bischofite solutions using a superposition model based on mixed potential theory for recovery an electrochemical and kinetics parameter of HER and ORR mechanisms. Additionally, a comprehensive surface analysis is conducted using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (DRX), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) imaging techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Mn2O3

The active material Mn2O3 was prepared by means of the co-precipitation method, from a solution (que se le agrega) containing MgSO4 (sigma-aldrich, 99% purity), MnSO4•H2O (sigma-aldrich, 99% purity) with a ratio of 1:2 respectively. The solution contains dissolved [1M] NaOH (sigma-aldrich, 99% purity) to keep the alkaline media and distilled water with 18.0 mΩ/cm of resistivity. The solution was kept under magnetic stirring (500 rpm) for 20 h to complete the reaction. The product of this reaction is a pink solid powder, which is subsequently filtered and dried at 80°C for 36 h. This last obtained powder is washed 5 times with plenty of deionized water to eliminate the remaining Na+ and SO42- ions remnants present in the precipitate obtained after the reaction). Once the solid is clean, it is introduced into a furnace at a temperature of 800°C for 6 h to form the Mn2O3 material and then allowed to cool to room temperature. The Mg are incorporated into de Mn2O3 dispersed over the spinel.

2.2. Electrochemical Measurements of Mn2O3 Electrode

The electrochemical measurements procedure was designed to examine the kinetic of the partial electrochemical reactions on the Mn

2O

3 spinel electrode immersed in 0.5 M MgCl

2 and 0.5 M of natural Bischofite solutions, focusing the attention on the HER, ORR, and Mn oxidation reaction (MnOR). A modified carbon paste electrode was prepared by mixing 0.2 g of Mn

2O

3 powder, 0.25 g of graphite powder, and 0.2 cm

3 of paraffin wax up to obtain a homogeneous paste. This paste was tightly packed into a plastic Teflon sheath (4 mm in diameter and 10 mm in length) which have with adequate perforations to maintain electrical contact, through a copper wire and the Mn

2O

3 powder, with the rotating disc electrode (RDE) system. Current density vs potential curves were obtained by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurements using a BASI/RDE-2 rotating electrode interphase connected to an Epsilon potentiostat/galvanostat in a conventional 3-electrode cell, in which, the carbon paste electrode with Mn

2O

3 powders acts as working electrode, a platinum wires acts as counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl (4M KCl Sat.) as a reference electrode (RE). All potentials reported are referred to as the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE). The experimental protocol for polarization data was according to a previous work [

8] in a potential range between -1000 to 400 mV/SHE. Before each run the Mn

2O

3 spinel electrode was maintained at -1200 mV/SHE for 30 s.

2.3. Kinetic Analysis

The kinetic analysis was performed by applying non-linear fitting to experimental polarization curves obtained from LVS measurements. The superposition model based on the mixed potential theory was considered according to the methodology described in our previous work concerning mass diffusion, charge transfer, and passivation mechanism controls [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The following set of kinetic expressions (Eqs. 1–4) is used as part of the non-linear fitting methodology, which considers the total current density (

) as a function of the partial current densities for the ORR (

), and HER (

) and MnOR (

):

Where, , and are the exchange current densities for ORR, HER, and MnOR respectively, is the limiting current density for ORR, , and are the overpotentials for ORR, HER, and MnOR respectively, is the electrochemical potential, , and are the equilibrium potentials for ORR, HER, and MnOR, respectively, , and are Tafel slopes for ORR, HER, and MnOR respectively, and is the kinetic order for the ORR is equal to 1. The kinetic parameters were calculated from the fitting of Eqs. 1-4 to the experimental data.

2.4. Mn2O3 Electrode Surface Characterization

The morphological characterization of the samples was performed by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) using the following instruments, a Zeiss EVO MA 10 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and SEM Hitachi model SU-5000 (Tokyo, Japan). The products layer was studied by X-ray diffraction (XRD) in a Shimadzu XRD-600 diffractometer (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) using Cu Kα radiation at an angular step of 0.02° (2θ) and counting time per step of 4s.

3. Results

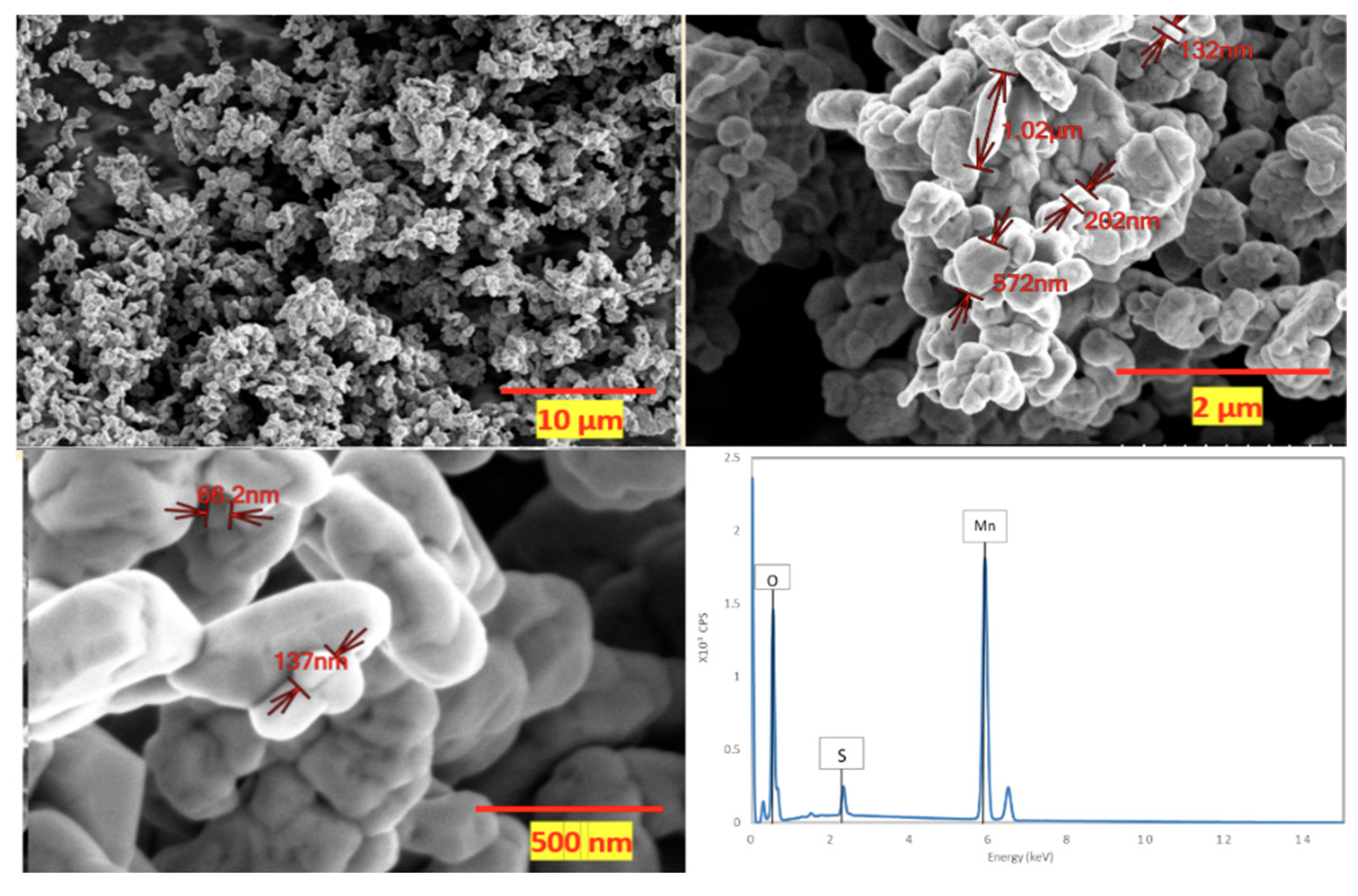

Figure 1 show a sequence of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images portraying the synthesized Mn

2O

3 material. These images were captured at varying magnifications: 3000x, 20,000x, and 70,000x. Accompanying these images is the EDS spectrum extracted from the sample. These micrographs offer a comprehensive view of the material’s morphology and structure, highlighting the characteristics of the granules present within the sample. Notably, the Mn

2O

3 granules exhibit a self-limiting growth pattern. The uniformity in their size is readily apparent; the average kernel size is determined to be 598, with a standard deviation of approximately 334.33. While this standard deviation signifies the presence of granules spanning diverse sizes, it is evident that most of these granules tend to cluster around the mentioned average size.

Moreover, the EDS spectrum, acquired utilizing secondary electrons at an energy of 30 keV, furnishes an intricate depiction of the elemental constitution of the material. The EDS analysis revealed a composition of 57.53±2.7% manganese (Mn), 31.29±10.36% oxygen (O), and 2.1±4.82% sulfur (S) within the material. Considering the anticipated composition of Mn2O3, we would anticipate a manganese (Mn) weight percentage of 69.6% and an oxygen (O) weight percentage of 30.4%. When contrasting these anticipated values with our EDS findings, deviations become evident. The EDS assessment showed a manganese (Mn) proportion of 57.53±2.7%, slightly lower than the projected theoretical value. Correspondingly, the oxygen (O) content measured at 31.29±10.36% is marginally higher, yet this discrepancy falls within the range accounted for by the standard deviation, relative to the theoretical estimate. Numerous factors might contribute to this disparity, ranging from the inherent nature of the synthesis process, which could yield a non-pure Mn2O3 product, to potential anomalies or interferences encountered during the EDS analysis. These values underscore that while the sample predominantly comprises manganese (Mn) and oxygen, aligning with the Mn2O3 expectation, the presence of sulphur, although in a diminished ratio, raises the prospect of a potential impurity originating from the raw materials employed in the synthesis process. This insight leads to the inference that the synthesis of Mn2O3 has been achieved with a noteworthy level of purity.

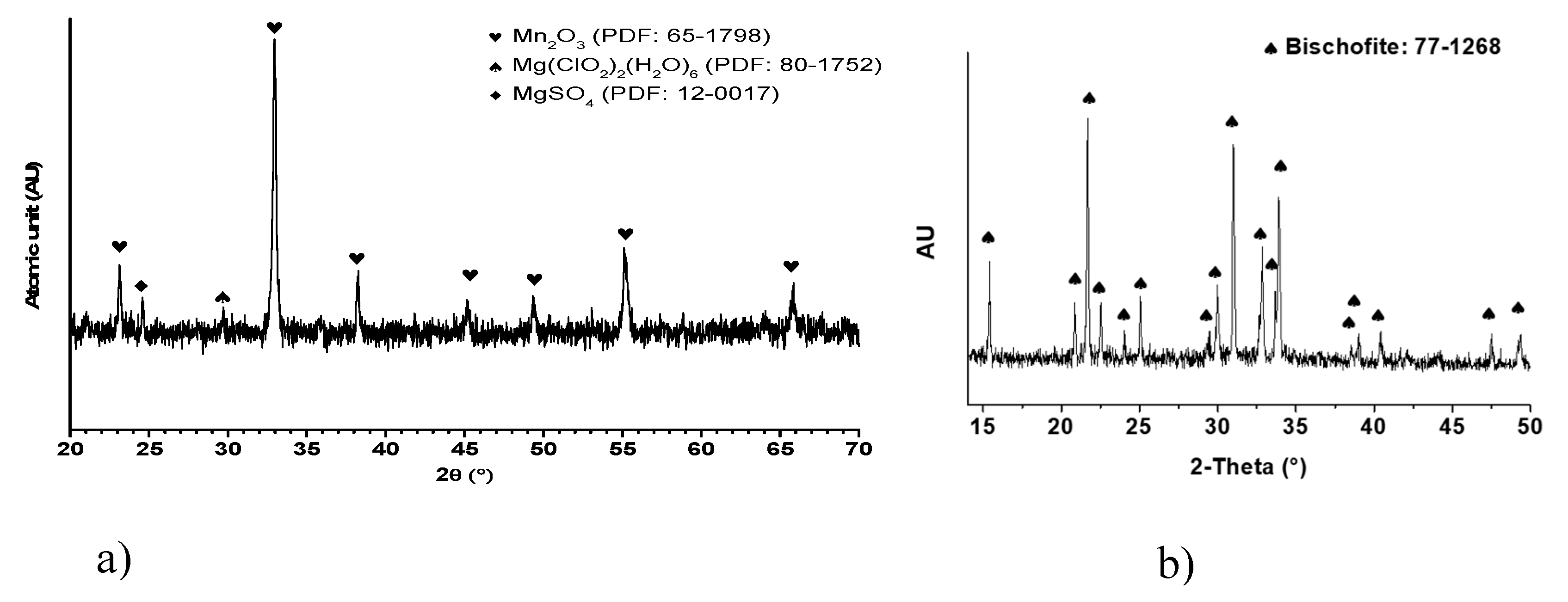

The results derivative from X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the Mn

2O

3 powder are shown in

Figure 2a. Particularly, a discrete peak is distinguished at the 2θ angle of 32.954°, positioning with a crystalline plane of (h, k, l) = 2, 2, 2 and displaying a relative intensity of 100%. This prominent peak assists as a definitive marker for the distinctive crystalline arrangement of Mn

2O

3. By XRD analysis, pivotal visions into the crystalline structure of Mn

2O

3 come to light. At the same time, the results obtained from XRD analysis of the nature bischofite (MgCl₂·6H₂O) salt are presented in

Figure 2b dissimilar peak appears at the 2θ angle closed to 16,32° , corresponding to the crystalline plane with indices (h, k, l) = 0, 0, 1 and showing a relative intensity of 100%. This peak serves as a clear indicator of the unique crystalline structure of bischofite. The XRD analysis reveals crucial details about the crystalline arrangement of bischofite.

The inclusion of Mn3+ within the Mn2O3 structure introduces specific structural distortions that stem from the Jahn-Teller effect. This effect, inherent to certain cations with distinct electronic configurations, can induce asymmetries within the crystalline arrangement. In the context of Mn2O3, these distortions hold the potential to exert an influence over the material’s physical and chemical attributes. Mn2O3 exhibits a propensity for thermal transformations. Notably, under temperatures nearing 550°C, noteworthy alterations in the tetragonal distortion of the spinel structure can arise. This phenomenon is closely intertwined with the Jahn-Teller effect and the concurrent presence of Mn3+ within the structure, signifying a connection between electronic interactions and structural changes.

Through meticulous analysis and comprehensive deliberation of the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) findings, unequivocal validation of the successful Mn2O3 formation via the employed synthesis process has been attained. The SEM images, in conjunction with the granule morphology characterization and the illustration of their self-limiting growth, furnish compelling substantiation of the synthesized Mn2O3 inherent nature and purity. Concurrently, the discernible XRD pattern, showcasing distinctive peaks emblematic of the crystalline Mn2O3 structure, reasserts the compound’s presence and precise crystalline configuration.

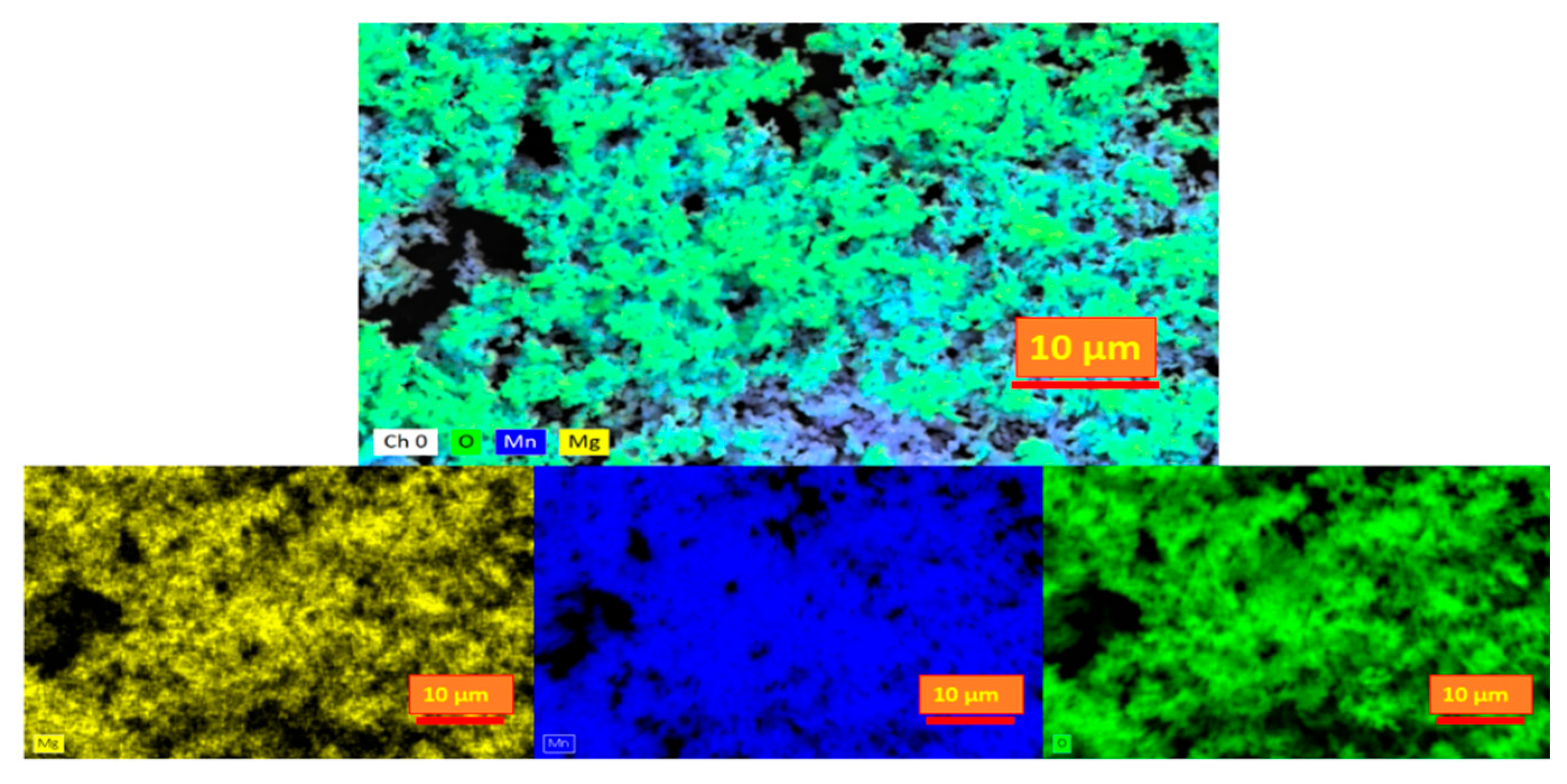

Figure 3.

Elemental mapping by EDS analysis for Mn2O3 powder.

Figure 3.

Elemental mapping by EDS analysis for Mn2O3 powder.

The confluence of these analytical techniques fortifies the confidence in the acquired outcomes, affirming the unequivocal attainment of Mn2O3 formation throughout the synthesis effort. This assurance assumes paramount significance, as the purity and accurate formation of Mn2O3 wield direct influence over its properties and potential applications within both research and industrial contexts.

The kinetic study was accomplished by applying non-linear fitting to experimental polarization data, considering the superposition model and mixed potential theory according to the methodology described in our previous works in terms of charge transfer, mass diffusion, and passivation mechanism controls [

8,

14,

15,

16,

17].

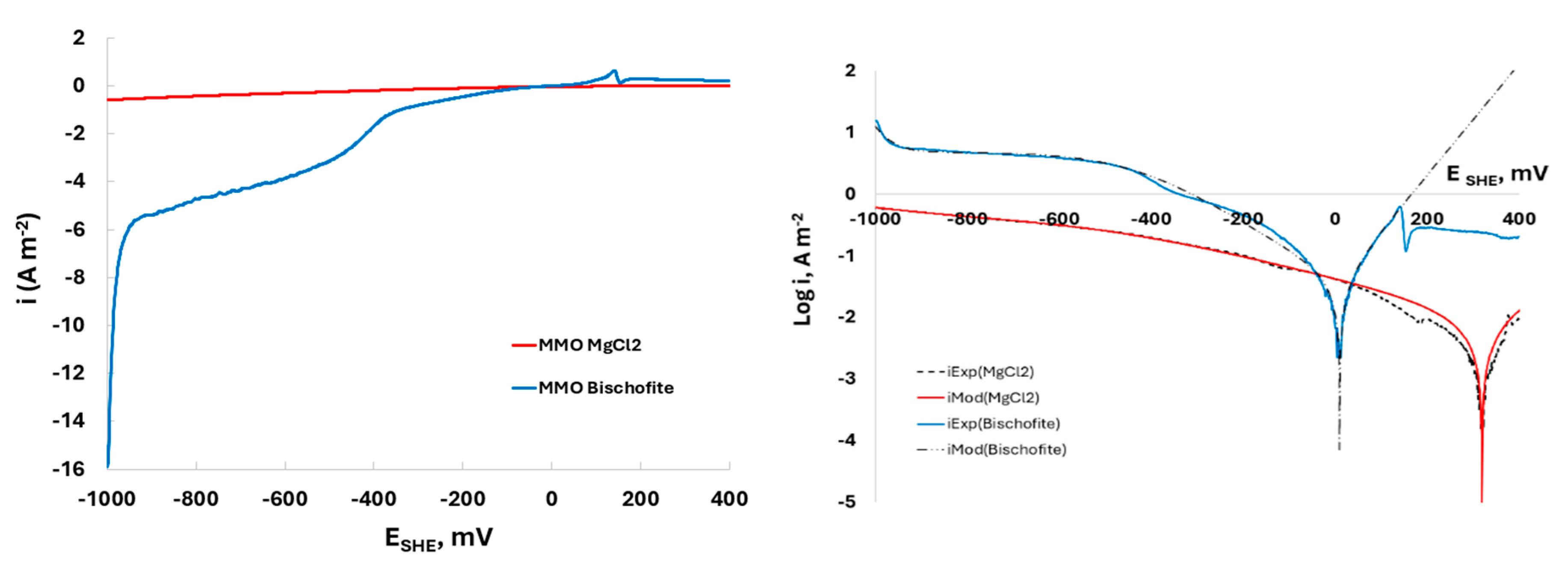

Figure 4 provides important information about the electrochemical–kinetic performance of Mn

2O

3 powder during the sub cathodic process in contact with a 0.5 M MgCl

2 and 0.5M of Bischofite solutions.

Figure 4a displays the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) results, where the potential window applied during the experiments ranged from -1000 to 400 mV/SHE.

When comparing the performance of Mn2O3, where H2 evolution is predominant, using bischofite solutions shows a slightly higher variation compared to using pure MgCl2 solution during the HER mechanism. This could be due to the presence of natural impurities in the bischofite that might act as co-factors promoting the charge transfer process. As for the cathodic potential range where the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) mechanism occurs, in the range of -1200 to -1000 mV the Tafel slope () were about -471 and -68 mV/dec for pure MgCl2 and nature bischofite, respectively.

4. Discussion

A higher Tafel slope suggests slower kinetics and lower efficiency for the HER mechanism. This is observed when using pure MgCl2 as the electrolyte in contact with the Mn2O3 electrode, where achieving a higher current density requires a significantly larger increase in overpotential, indicating less effective charge transfer processes. In contrast, when using natural bischofite as the electrolyte, the lower Tafel slope indicates faster kinetics and higher efficiency for the HER mechanism. The smaller increase in overpotential required for higher current densities suggests more effective charge transfer processes and better catalytic performance in the HER range. Higher slope observed for natural bischofite solution indicates that is a more efficient medium for the HER compared to pure MgCl2 electrolyte, due to the presence of natural impurities in bischofite that enhance the catalytic activity of the Mn2O3 electrode.

During ORR, the

were -0.351 and -4.810 A/m

2 for pure MgCl

2 and nature bischofite, respectively. For nature bischofite, the higher value of

indicates limitations in the mass transport, suggesting better performance in facilitating the oxygen-related process. The

for both electrolytes were negligible that implies the intrinsic rate of the oxygen-related electrochemical reaction is too much low in both cases. These low

recommends that the kinetics are slow at equilibrium [

18,

19,

20].

The resistance of Mn

2O

3 powder electrode in contact with pure MgCl

2 and nature Bischofite solutions reveals values of E

corr and i

corr equals 324 and 9 mV/SHE and 5.66·10

-3 and 3.89·10

-2 A/m

2, respectively. The E

corr and i

corr values indicate a high resistance of corrosion during HER mechanims, which is supported by the performance of the Evans curve shown in

Figure 4b and the electrochemical kinetic parameters for HER, ORR, and MnOR, tabulated in

Table 1.

Table 1, presents the key corrosion and kinetic parameters obtained from the application of the superposition model, utilizing Equations 1 to 4. The parameters are presented in relation to their respective controls, including charge transfer, mass diffusion, and dissolution mechanisms. This comprehensive analysis provides valuable insights into the governing factors and mechanisms influencing the corrosion behaviour in the studied system.

The Tafel slope for HER using Mn2O3 in bischofite solutions is -68 mV/dec, indicates that exist a stronger linear relationship between the logarithm of the current density and the overpotential, with a negative slope representing a decrease in overpotential as the current density increases. For other way, the Tafel slope for MgCl2 solutions is -472 mV/dec suggests efficient HER kinetics.

Numerous electrode materials have shown promise for HER mechanims in seawater or brine, it is important to note that the H

2 Tafel slope, represents the rate of the HER, and depend on specific experimental conditions and electrode preparation methods [

25,

26]. In seawater the Pt is often considered the standard for HER due to its excellent catalytic activity with Tafel slope typically ranges from around -30 to -40 mV/dec [

27]. The Tafel slope of Ni-Fe alloys fluctuate from -91 to -149 mV/dec and depending on the specific Ni-Fe alloy composition and the surface modifications [

28]. On the other way, Ni-Mo has Tafel slopes in a range from -40 to -60 mV/dec. The Tafel slope for CoP material is typically between -40 to -50 mV/dec in 1 M KOH [

29,

30,

31].

5. Conclusions

The use of Mn2O3 powder as electrodes for hydrogen evolution reactions (HER) in contact with solutions of pure MgCl2 and natural bischofite salt shows significant differences in electrochemical performance and kinetic parameters. The kinetic analysis using non-linear fitting proved efficient. This superposition model, based on mixed potential theory, effectively described the controls of mass diffusion, charge transfer, and oxidation mechanisms during saline water splitting. The Tafel slopes from Evans curves indicate that natural bischofite salt is more efficient for the HER mechanism, with a Tafel slope of -68 mV/dec compared to -471 mV/dec for pure MgCl2. This lower Tafel slope for natural bischofite suggests faster kinetics and higher efficiency, requiring a smaller increase in overpotential to achieve higher current densities, indicating more effective charge transfer processes and better catalytic performance. The limiting current densities () for the electrolytes were -0.351 A/m² for pure MgCl2 and -4.810 A/m² for natural bischofite salt from the Atacama Desert. The significant increase in the absolute value of the limiting current density for bischofite shows its superior performance in supporting faster oxygen-related processes before mass transport limitations occur. However, the negligible exchange current densities () for both electrolytes indicate slow intrinsic reaction kinetics at equilibrium, highlighting a common limitation in both systems. Natural bischofite is a superior electrolyte for HER due to its lower Tafel slope and higher limiting current density for oxygen-related processes, suggesting enhanced efficiency and catalytic performance compared to pure MgCl2. These findings demonstrate that bischofite can be an effective and efficient medium for electrochemical applications, particularly in hydrogen evolution and potentially other related electrochemical processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.G.M, S.SA, and A.S.; methodology, F.M.G.M, S.SA, C.P, L.C., and A.S.; software, F.M.G.M, S.SA, L.C., A.S.; validation, F.M.G.M, S.SA. and L.C.; formal analysis, F.M.G.M, S.SA, S.LG, L.C., A.S, F.S, I.B, J.A.CM, O.F.RM, V. and E.S, .; investigation, F.S, I.B, J.A.CM, S. LG, O.F.RM, V.J, and E.S.; resources, F.M.G.M, S.SA, and L.C.,.; data curation, S.SA F.S, I.B, J.A.CM, O.F.RM, V.J, and E.S,.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.G.M, S.SA, L.C., A.S, S.SA F.S, I.B, J.A.CM, O.F.RM, V.J, and E.S,.; writing—review and editing, F.M.G.M, S.SA, L.C., A.S, S.SA F.S, I.B, J.A.CM, O.F.RM, V.J, and E.S, .; visualization, F.M.G.M, and S.SA.; supervision, F.M.G.M.; project administration, F.M.G.M.; funding acquisition, F.M.G.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of ANID through research grant FONDECYT N° 11230550, and the Project DIUDA N° 22430 from the Universidad de Atacama. The authors would like to thank the Programa de Doctorado en Energía Solar of the Universidad de Antofagasta, Chile and ANID/ FONDAP 1522A0006 Solar Energy Research Center SERC-Chile.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- D. Eberhardt, E. Santos, and W. Schmickler, “Hydrogen evolution on silver single crystal electrodes — first results 1,” vol. 461, pp. 76–79, 1999.

- W. Wei, X. Cui, W. Chen, and D. G. Ivey, “Manganese oxide-based materials as electrochemical supercapacitor electrodes,” Chem Soc Rev, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 1697–1721, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. N. Sinha and N. Munichandraiah, “Electrochemical conversion of LiMn2O4 to MgMn2O4 in aqueous electrolytes,” Electrochemical and Solid-State Letters, vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 3–6, 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. Ling and F. Mizuno, “Phase stability of post-spinel compound AMn2O4 (A = Li, Na, or Mg) and its application as a rechargeable battery cathode,” Chemistry of Materials, vol. 25, no. 15, pp. 3062–3071, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Rahman and D. Gerosa, “Preparation of Cathode Material for Rechargeable Magnesium Battery Application,” in Global Engineering, Science and Technology Conference, 2015, pp. 2–6.

- C. Miralles and R. Gómez, “Proving insertion of Mg in Mn2O3 electrodes through a spectroelectrochemical study,” Electrochem commun, vol. 106, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Mokkath, M. Jahan, M. Tanaka, S. Tominaka, and J. Henzie, “Temperature-dependent electronic structure of bixbyite α-Mn2O3 and the importance of a subtle structural change on oxygen electrocatalysis,” Sci Technol Adv Mater, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 141–149, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Cáceres, Y. Frez, F. Galleguillos, A. Soliz, B. Gómez-silva, and J. Borquez, “Aqueous dried extract of skytanthus acutus meyen as corrosion inhibitor of carbon steel in neutral chloride solutions,” Metals (Basel), vol. 11, no. 12, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Cáceres, L. Herrera, and T. Vargas, “Corrosion kinetics studies of AISI 1020 carbon steel from dissolved oxygen consumption measurements in aqueous sodium chloride solutions,” Corrosion, vol. 63, no. 8, pp. 722–730, 2007. [CrossRef]

- L. Cáceres, T. Vargas, and M. Parra, “Study of the variational patterns for corrosion kinetics of carbon steel as a function of dissolved oxygen and NaCl concentration,” Electrochim Acta, vol. 54, no. 28, pp. 7435–7443, 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Cáceres, T. Vargas, and L. Herrera, “Influence of pitting and iron oxide formation during corrosion of carbon steel in unbuffered NaCl solutions,” Corros Sci, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 971–978, 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Cáceres, T. Vargas, and L. Herrera, “Determination of electrochemical parameters and corrosion rate for carbon steel in un-buffered sodium chloride solutions using a superposition model,” Corros Sci, vol. 49, no. 8, pp. 3168–3184, 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. Luis, Y. Frez, F. Galleguillos, A. Soliz, G. Benito, and J. Borquez, “Aqueous Dried Extract of Skytanthus acutus Meyen as Corrosion Inhibitor of Carbon Steel in Neutral Chloride Solutions,” Metals (Basel), vol. 11, no. 12, pp. 1–23, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Cáceres, T. Vargas, and M. Parra, “Study of the variational patterns for corrosion kinetics of carbon steel as a function of dissolved oxygen and NaCl concentration,” Electrochim Acta, vol. 54, no. 28, pp. 7435–7443, 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Cáceres, T. Vargas, and L. Herrera, “Influence of pitting and iron oxide formation during corrosion of carbon steel in unbuffered NaCl solutions,” Corros Sci, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 971–978, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Soliz and, L. Cáceres, “Corrosion behavior of carbon steel in LiBr in comparison to NaCl solutions under controlled hydrodynamic conditions,” Int J Electrochem Sci, vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 5673–5693, 2015.

- Soliz, D. Guzmán, L. Cáceres, and F. M. G. Madrid, “Electrochemical Kinetic Analysis of Carbon Steel Powders Produced by High-Energy Ball Milling,” Metals (Basel), vol. 12, no. 4, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Cao et al. Mn2O38, no. 9, pp. 6040–6050, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Mokkath, M. Jahan, M. Tanaka, S. Tominaka, and J. Henzie, “Temperature-dependent electronic structure of bixbyite α-Mn2O3 and the importance of a subtle structural change on oxygen electrocatalysis,” Sci Technol Adv Mater, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 141–149, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Jahan, S. Tominaka, and J. Henzie, “Phase pure α-Mn2O3 prisms and their bifunctional electrocatalytic activity in oxygen evolution and reduction reactions,” Dalton Transactions, vol. 45, no. 46, pp. 18494–18501, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. V. Rybalka, L. A. Beketaeva, N. G. Bukhan’ko, and A. D. Davydov, “Dependence of corrosion current on the composition of titanium-nickel alloy in NaCl solution,” Russian Journal of Electrochemistry, vol. 50, no. 12, pp. 1149–1156, 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Cheng, J. Shen, W. Ji, Z. Tao, and J. Chen, “Selective synthesis of manganese oxide nanostructures for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction,” ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 460–466, Feb. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Roche, E. Chaînet, M. Chatenet, and J. Vondrák, “Carbon-supported manganese oxide nanoparticles as electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) in alkaline medium: Physical characterizations and ORR mechanism,” Journal of Physical Chemistry C, vol. 111, no. 3, pp. 1434–1443, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, J. Geng, L. Kuai, M. Li, and B. Geng, “Porous Mn2O3: A Low-Cost Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Alkaline Media with Comparable Activity to Pt/C,” Chemistry - A European Journal, vol. 22, no. 29, pp. 9909–9913, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. E. Badea, I. Maior, A. Cojocaru, and I. Corbu, “The cathodic evolution of hydrogen on nickel in artificial seawater,” 2007.

- T. Shinagawa, A. T. Garcia-Esparza, and K. Takanabe, “Insight on Tafel slopes from a microkinetic analysis of aqueous electrocatalysis for energy conversion,” Sci Rep, vol. 5, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Xiu et al., “Multilevel Hollow MXene Tailored Low-Pt Catalyst for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution in Full-pH Range and Seawater,” Adv Funct Mater, vol. 30, no. 47, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang et al., “MnOxFilm-Coated NiFe-LDH Nanosheets on Ni Foam as Selective Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysts for Alkaline Seawater Oxidation,” Inorg Chem, vol. 61, no. 38, pp. 15256–15265, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lyu et al.,, “Interfacial electronic structure modulation of CoP nanowires with FeP nanosheets for enhanced hydrogen evolution under alkaline water/seawater electrolytes,” Appl Catal B, vol. 317, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Liu et al., “Porous CoP/Co2P heterostructure for efficient hydrogen evolution and application in magnesium/seawater battery,” J Power Sources, vol. 486, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Ye et al., “Removing the barrier to water dissociation on single-atom Pt sites decorated with a CoP mesoporous nanosheet array to achieve improved hydrogen evolution,” J Mater Chem A Mater, vol. 8, no. 22, pp. 11246–11254, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).