Submitted:

07 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

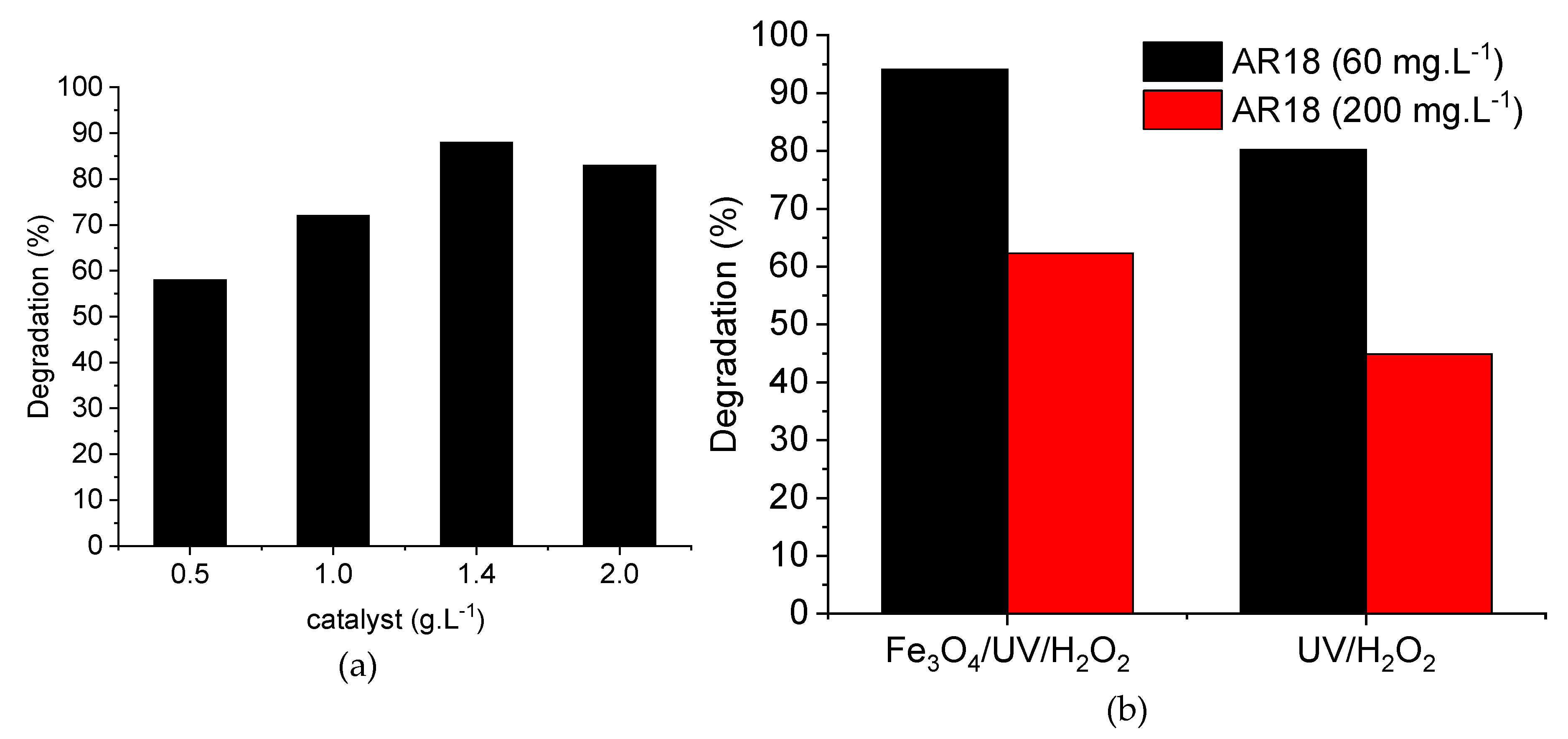

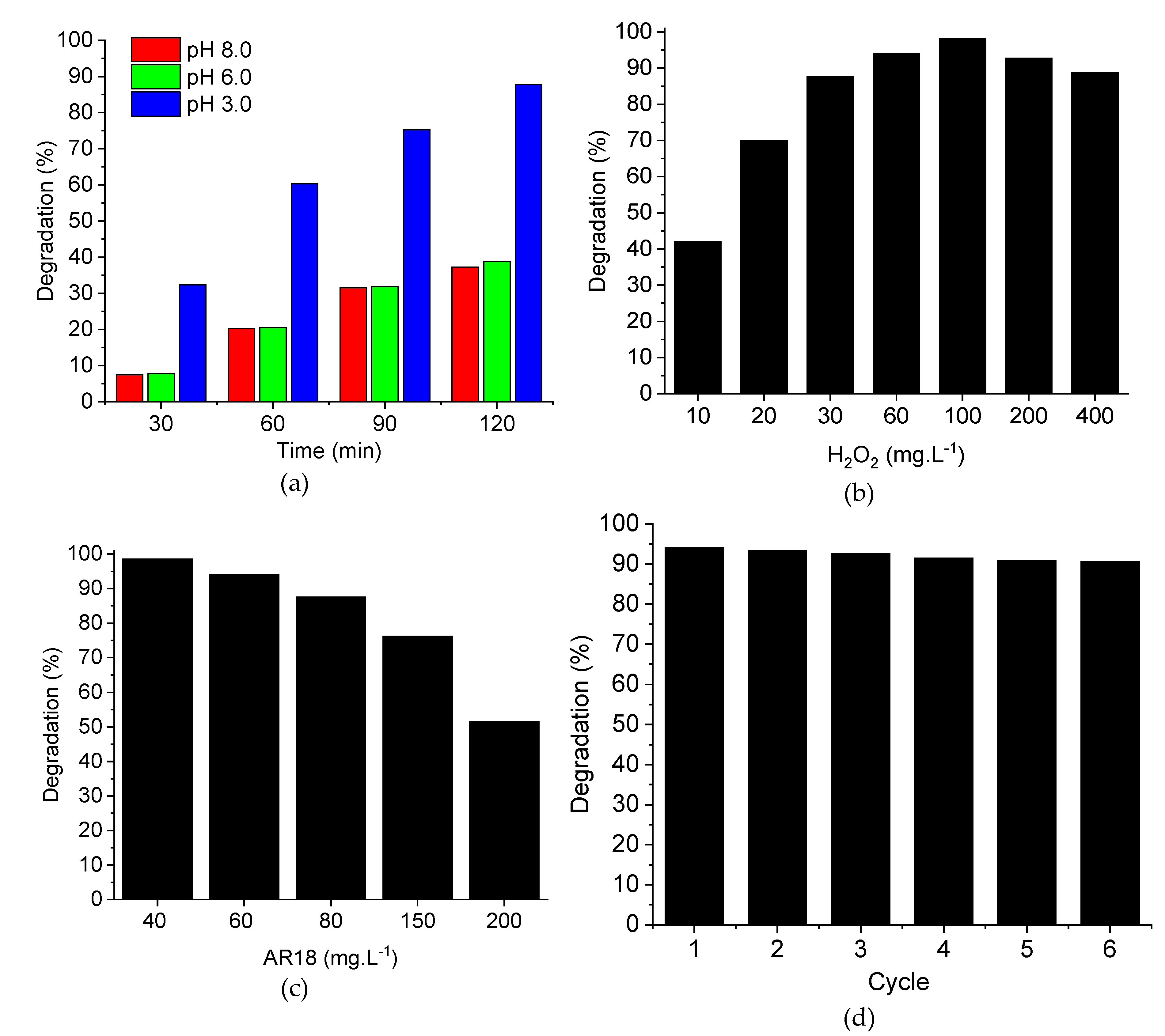

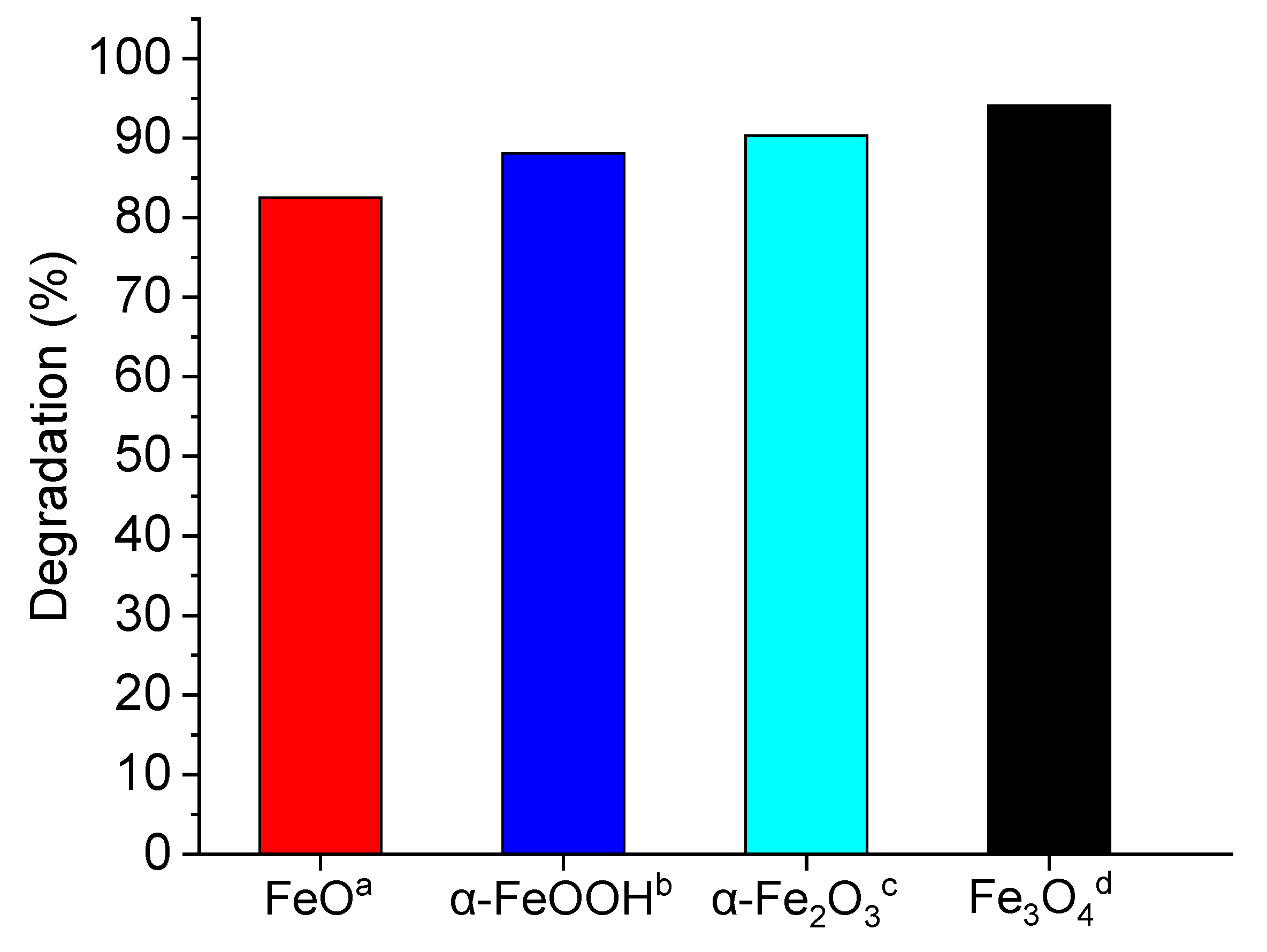

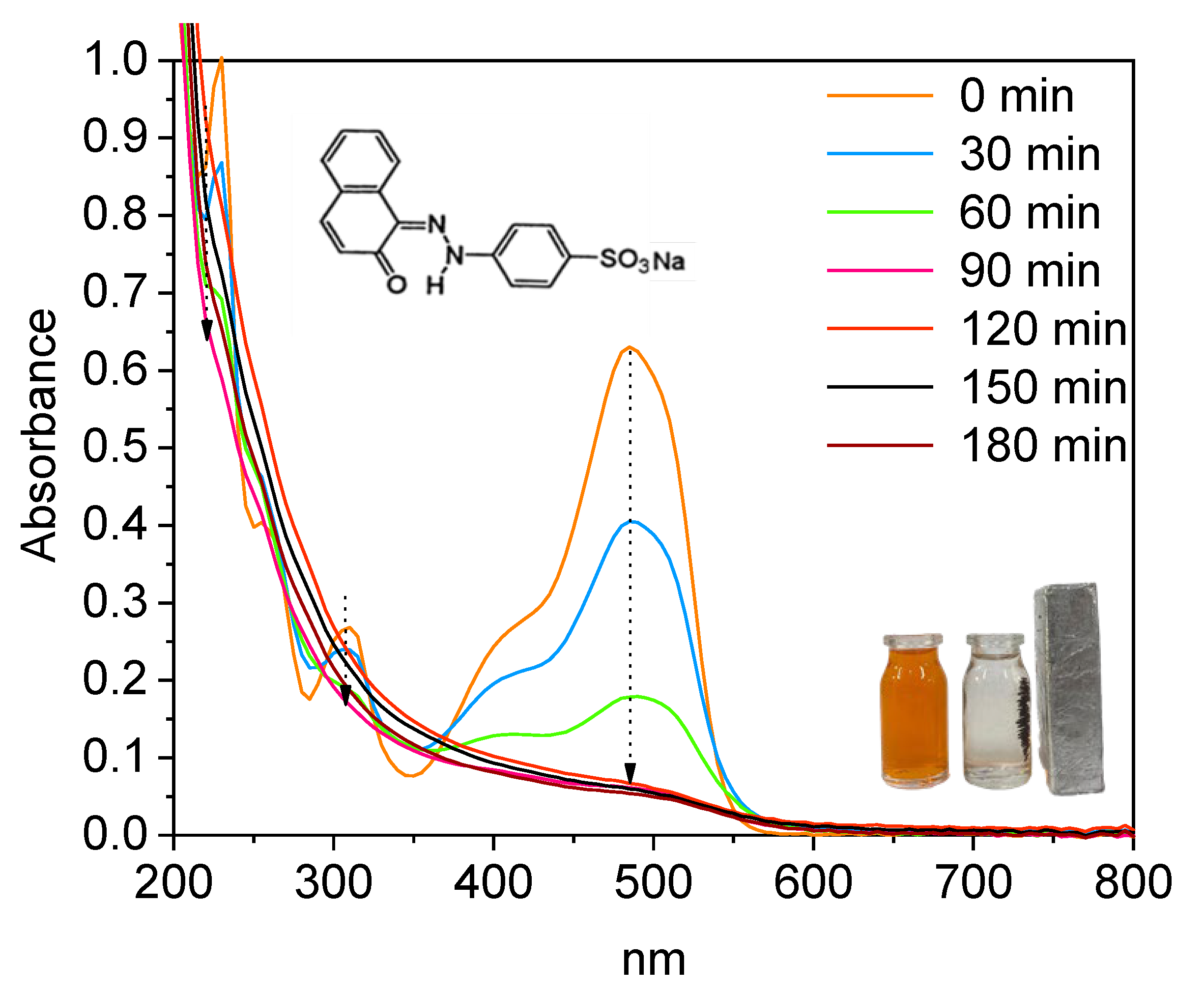

2.1. Heterogeneous Photo-Fenton-Like Reaction

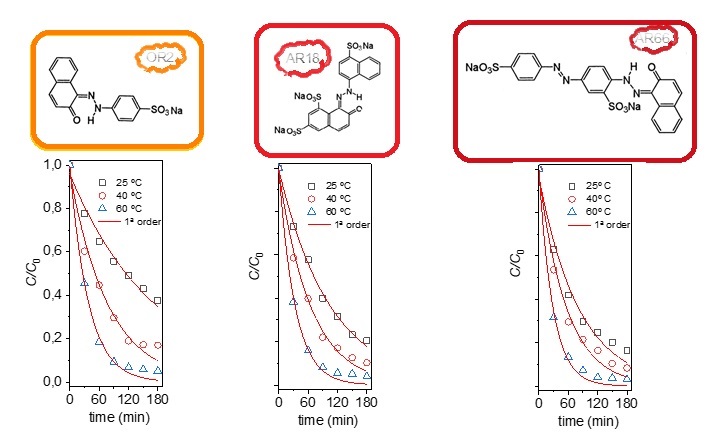

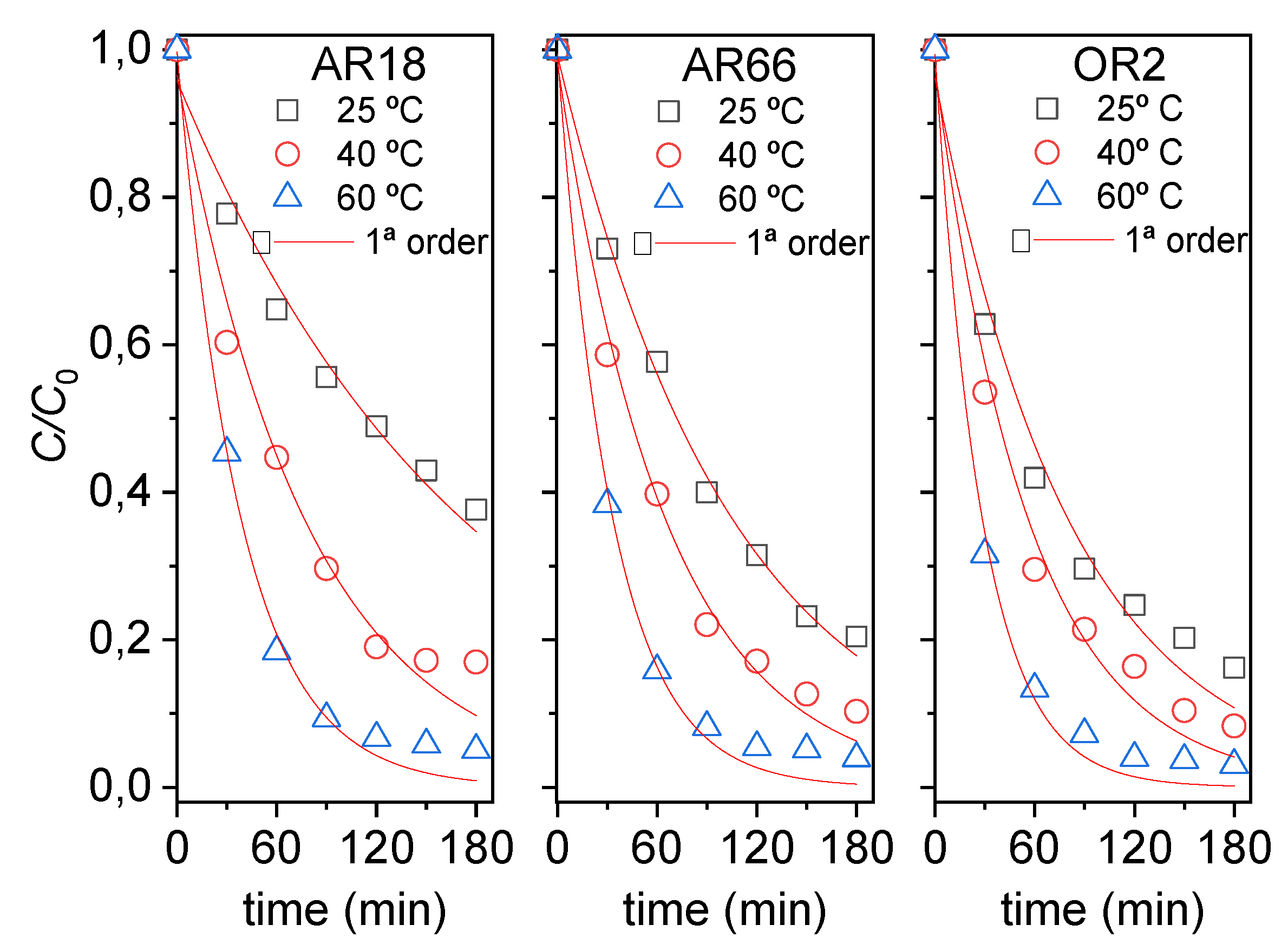

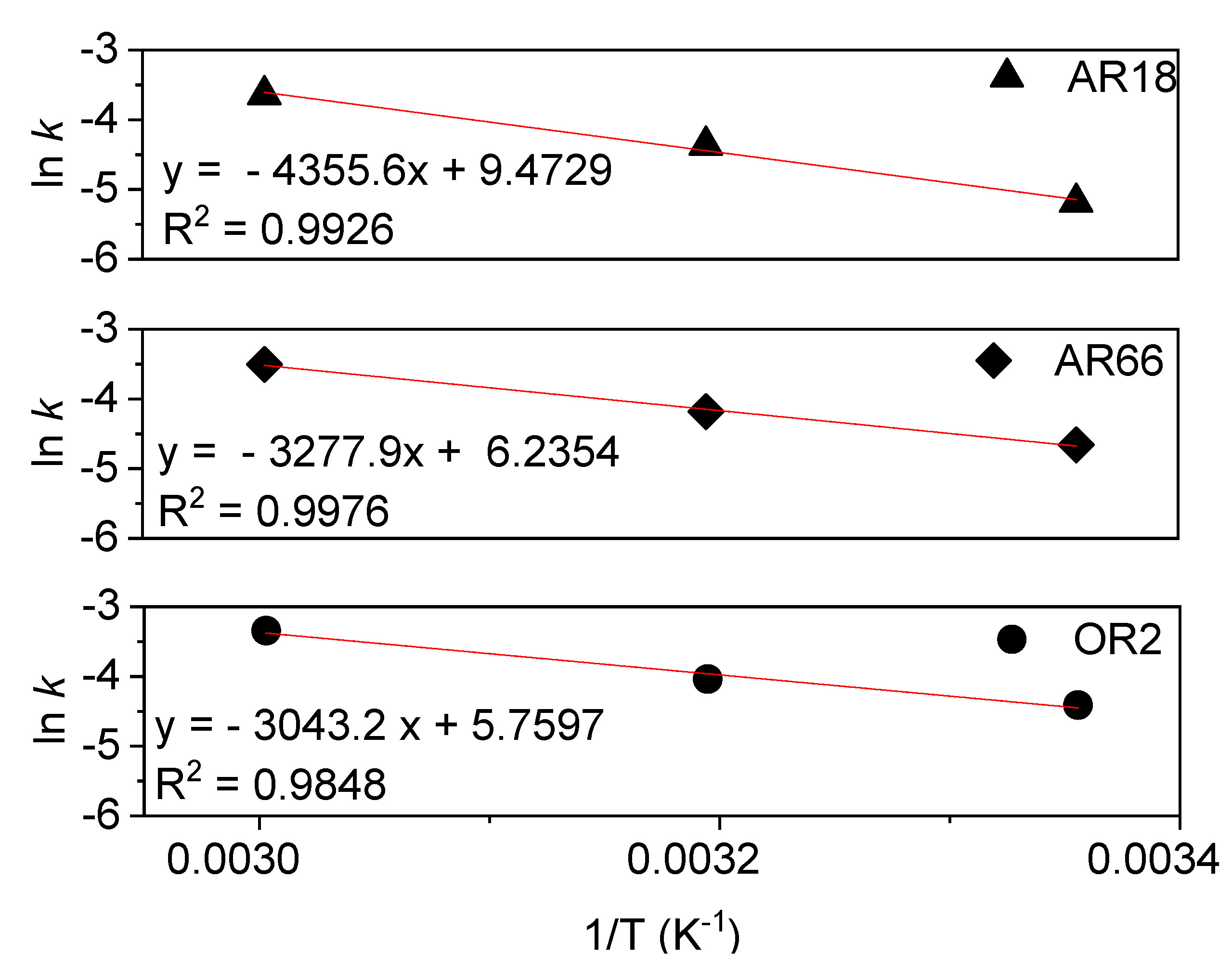

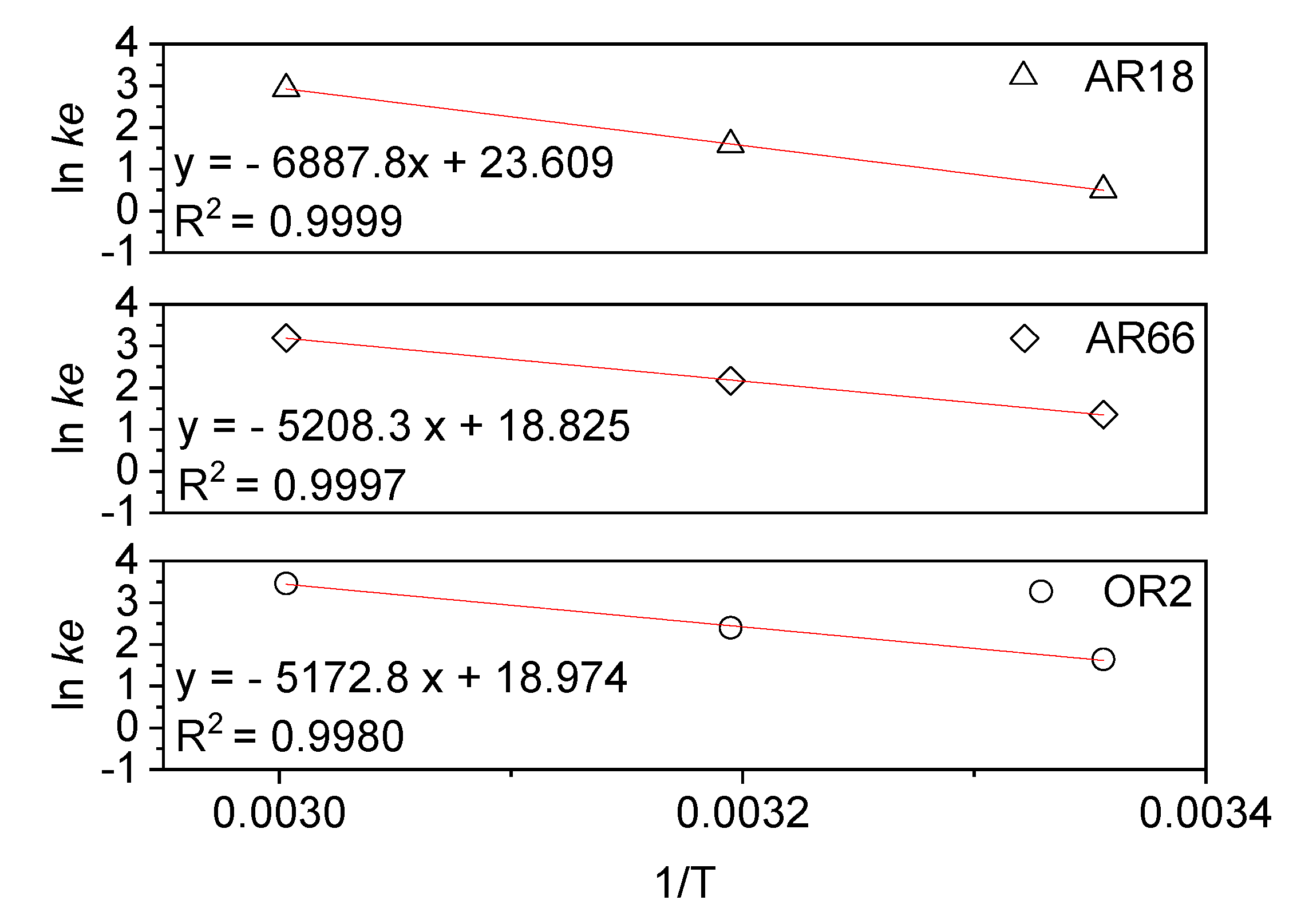

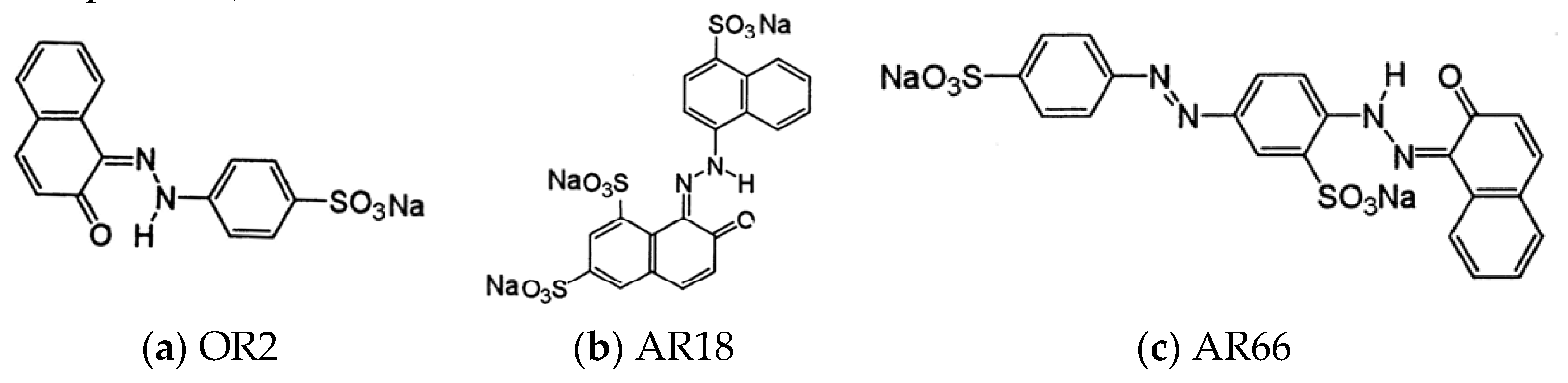

2.2. Kinetic and Thermodynamic of Degradation

2.3. Treated Solution Characterization

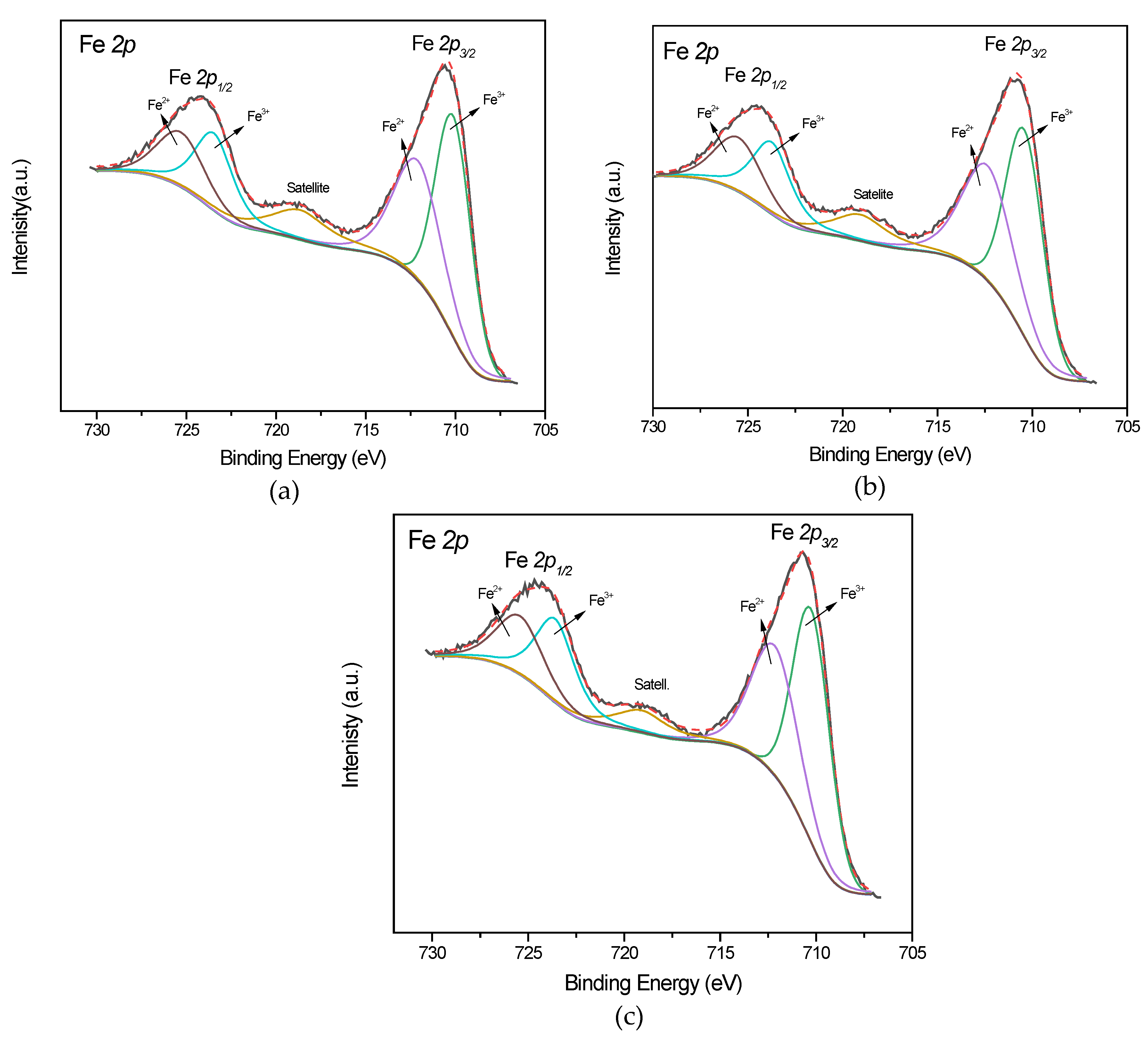

2.4. Spent Magnetite Characterization

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Catalyst Synhesis and Characterizations

3.3. Heterogeneous Photo-Fenton-Like Oxidation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Z.; Yan, Y.; Lu, C.; Lin, X.; Fu, Z.; Shi, W.; Guo, F. Photocatalytic self-Fenton system of g-C3N4-Based for degradation of emerging contaminants: a review of advances and prospects. Molecules 2023, 28, 5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Bai, Z.; Yu, S.; Meng, X.; Xiao, S. Photo-Fenton efficient degradation of organic pollutants over S-scheme ZnO@NH2-MIL-88B heterojunction established for electron transfer channel. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 288, 119789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magomedova, A.; Isaev, A.; Orudzhev, F.; Sobola, D.; Murtazali, R.; Rabadanova, A.; Shabanov, N.S.; Zhu, M.; Emirov, R.; Gadzhimagomedov, S.; Alikhanov, N.; Kasinathan, K. Magnetically separable mixed-phase α/γ-Fe2O3 catalyst for photo-Fenton-like oxidation of Rhodamine B. Catalysts 2023, 13, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchimi Nono, K.; Vahl, A.; Terraschke, H. Towards high-performance photo-Fenton degradation of organic pollutants with magnetite-silver composites: synthesis, catalytic reactions and in situ insights. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijoo, S.; González-Rodríguez, J.; Fernández, L.; Vázquez-Vázquez, C.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T. Fenton and photo-Fenton nanocatalysts revisited from the perspective of life cycle assessment. Catalysts 2020, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, G.A.; Sakai, H. Review on effect of different type of dyes on advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for textile color removal. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Fang, W.; Yi, Q.; Zhang, J. A comprehensive review on reactive oxygen species (ROS) in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahbub, P.; Duke, M. Scalability of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) in industrial applications: a review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorontsov, A.V. Advancing Fenton and photo-Fenton water treatment through the catalyst design. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 372, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; He, X.; Ye, J.; Dai, H.; Peng, W.; Cheng, Z.; Yan, B.; Chen, G.; Wang, S. H2O2 activation and contaminants removal in heterogeneous Fenton-like systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, B.O.; Bilici, Z.; Ugur, N.; Isik, Z.; Harputlu, E.; Dizge, N.; Ocakoglu, K. Adsorption and Fenton oxidation of azo dyes by magnetite nanoparticles deposited on a glass substrate. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 32, 100897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunç, S.; Gürkan, T.; Duman, O. On-line spectrophotometric method for the determination of optimum operation parameters on the decolorization of Acid Red 66 and Direct Blue 71 from aqueous solution by Fenton process. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 181–182, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubeenaa, K.K.; Reddy PH, P.; Laiju, A.R.; Nidheesh, P.V. Iron impregnated biochars as heterogeneous Fenton catalyst for the degradation of Acid Red 1 dye. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 226, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Tyagi, V.V.; Chopra, K.; Kothari, R.; Singh, H.M.; Pandey, A.K. Advancement in solar energy-based technologies for sustainable treatment of textile wastewater: reuse, recovery and current perspectives. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 56, 104241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusevova, K.; Kopinke, F.D.; Georgi, A. Nano-sized magnetic iron oxides as catalysts for heterogeneous Fenton-like reactions-influence of Fe(II)/Fe(III) ratio on catalytic performance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 241-242, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minella, M.; Marchetti, G.; De Laurentiis, E.; Malandrino, M.; Maurino, V.; Minero, C.; Vione, D.; Hanna, K. Photo-Fenton oxidation of phenol with magnetite as iron source. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 154–155, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Zhang, H.; Ye, Z. Recent advances in the application of natural iron and clay minerals in heterogeneous electro-Fenton process. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2024, 46, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzenda, C.; Arotiba, O.A. Improved magnetite nanoparticle immobilization on a carbon felt cathode in the heterogeneous electro-Fenton degradation of Aspirin in wastewater. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 19261–19269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Yang, L.; Qian, L.; Han, L.; Chen, M. Nano-magnetite supported by biochar pyrolyzed at different temperatures as hydrogen peroxide activator: synthesis mechanism and the effects on ethylbenzene removal. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 261, 114020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.W.; Hwang, K.Y. Effects of reaction conditions on the oxidation efficiency in the Fenton process. Water Res. 2000, 34, 2786–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbusiński, K.; Majewski, J. Discoloration of azo dye Acid Red 18 by Fenton reagent in the presence of iron powder. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2003, 12, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Malakootian, M.; Moridi, A. Efficiency of electro-Fenton process in removing Acid Red 18 dye from aqueous solutions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 111, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Karaca, C.; Karaca, S.; Khataee, A.; Açisli, Ö.; Yilmaz, B. Enhanced removal of Basic Violet 10 by heterogeneous sono-Fenton process using magnetite nanoparticles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 42, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Shen, W. FeOOH quantum dot decorated flower-like WO3 microspheres for visible light driven photo-Fenton degradation of Methylene Blue and Acid Red-18. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 643, 128754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulštáková, A. Removal of pharmaceutical micropollutants from real wastewater matrices by means of photochemical advanced oxidation processes – a review J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 53, 103727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergendahl, J.A.; Thies, T.P. Fenton's oxidation of MTBE with zero-valent iron. Water Res. 2004, 38, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, A.; Moghaddam MR, A.; Maknoon, R.; Kowsari, E. Investigation of enhanced Fenton process (EFP) in color and COD removal of wastewater containing Acid Red 18 by response surface methodology: evaluation of EFP as post treatment. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 57, 1944–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Segura, S.; Brillas, E. Combustion of textile monoazo, diazo and triazo dyes by solar photoelectro-Fenton: Decolorization, kinetics and degradation routes. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2016, 181, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaghani, M.A.; Dehdarirad, A.; Mahdizadeh, H.; Hashemi, H.; Nasiri, A.; Samaei, M.R.; Mohammadpour, A. Photocatalytic degradation of Acid Red 18 by synthesized AgCoFe2O4@Ch/AC: Recyclable, environmentally friendly, chemically stable, and cost-effective magnetic nano hybrid catalyst. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 131897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Vélez, E.; Martínez, H.; Castillo, F. Degradation of Acid Red 1 catalyzed by peroxidase activity of iron oxide nanoparticles and detected by SERS. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, A.; Khattak, R.; Khan, M.S.; Begum, B.; Khan, S.; Han, C. Synthesis, characterization, and solar photo-activation of chitosan-modified nickel magnetite bio-composite for degradation of recalcitrant organic pollutants in water. Catalysts 2022, 12, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.; Hameed, B.H. Oxidative decolorization of Acid Red 1 solutions by Fe-zeolite Y type catalyst. Desalination 2011, 276, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.R.; Mengelizadeh, N.; Aghdavodian, G.; Zare, F.; Ansari, Z.; Hashemi, F.; Moradalizadeh, S. Adsorption of Acid Red 18 from aqueous solutions by GO-COFe2O4: Adsorption kinetic and isotherms, adsorption mechanism and adsorbent regeneration. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 317, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, C.S.; Ramos MD, N.; Velloso CC, V.; Aguiar, A. Kinetic evaluation of dye decolorization by Fenton processes in the presence of 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, P.; He, H.; Zhang, J. The decolorization of Acid Orange II in non-homogeneous Fenton reaction catalyzed by natural vanadium–titanium magnetite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 181, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Tong, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, Y.; Wei, F. Fe3O4-NPs/orange peel composite as magnetic heterogeneous Fenton-like catalyst towards high-efficiency degradation of methyl orange. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, X.S.; Ngo, K.D. The role of metal-doped into magnetite catalysts for the photo-Fenton degradation of organic pollutants. J. Surf. Eng. Mater. Adv. Technol. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Byun, J.Y.; Kim, S.H. An electro-Fenton system with magnetite coated stainless steel mesh as cathode. Catal. Today 2021, 359, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Gamra, Z.M. Kinetic and thermodynamic study for Fenton-like oxidation of Amaranth Red dye. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2014, 4, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuchi, S.B.; Suhan, M.B.K.; Humayun, S.B.; Haque, M.E.; Islam, M.S. Heat-activated potassium persulfate treatment of Sudan Black B dye: Degradation kinetic and thermodynamic studies. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 39, 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, P.; Nicholls, C.H. Azo-hydrazone tautomerism of hydroxyazo compounds-a review. Dyes Pigm. 1982, 3, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, T.; Kayane, Y.; Tezuka, Y. Design of chlorine-fast reactive dyes: Part 1: The role of sulphonate groups and optimization of their positions in an arylazonaphthol system. Dyes Pigm. 1992, 20, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, S. Quantitative structure-activity relationship in the photodegradation of azo dyes. J. of Environmental Sci. 2020, 90, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, R.G. Hard and soft acids and bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3533–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Xu, S.; Chen, J.; Miao, X.; Zhu, J. Oxalate enhanced degradation of Orange II in heterogeneous UV-Fenton system catalyzed by Fe3O4@g-Fe2O3 composite. Chemosphere 2018, 199, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, C.B.; Araújo, R.S.; Oton, L.F.; Oliveira, A.C.; Soares, J.M.; Medeiros, S.N.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Rodríguez-Aguado, E. Acid Red 66 dye removal from aqueous solution by Fe/C-based composites: Adsorption, kinetics and thermodynamic studies. Mater. 2020, 13, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurushankar, K.; Chinnaiah, K.; Kannan, K.; Gohulkumar, M.; Periyasamy, P. Synthesis and characterization of FeO nanoparticles by hydrothermal method. Rasayan J. Chem. 2021, 14, 1985–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, M.R.; Zoli, L.; Sani, E. Synthesis and characterization of goethite (α-FeOOH) magnetic nanofluids. Int. J. Thermofluids 2022, 15, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Farha, S.A. Comparative study of oxidation of some azo dyes by different advanced oxidation processes: Fenton, Fenton-Like, photo-Fenton and photo-Fenton-like. J. Am. Sci. 2010, 6, 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, M.S.; Algarra, M.; Jiménez-Jiménez, J.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Peres, J.A. Catalytic activity of porous phosphate heterostructures-Fe towards Reactive Black 5 degradation. Int. J. Photoenergy 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, G.; Li, W.; Wan, D.; Hu, Q.; Lu, L. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of Orange II removal by heterogeneous Fenton-like process using Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2014, 25, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Wang, Q.; Tang, B. Effective degradation of C.I. Acid Red 73 by advanced Fenton process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 174, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, A.J.M.; Silva, A.N.; Oliveira, A.C.; do Carmo, J.V.C.; Saraiva, G.D.; Juca, R.F.; Morales, M.A.; Lang, R.; Jiménez, J.J.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E. Catalytic performances of the nano FeCo solids for biofuel additives production: Incorporation of promoters effects on the stability of the catalysts. Energy & Fuels 2023, 37, 22–17328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, A.; Sharma, M.; Sahu, N.S. Assessing magnetic and inductive thermal properties of various surfactants functionalised Fe3O4 nanoparticles for hyperthermia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Yu, L.; Chen, Z.-F.; He, H.; Ye, F.; Cheng, G.; Zha, Q. Microwave-assisted synthesis of Fe3O4 nanocrystals with predominantly exposed facets and their heterogeneous UVA/Fenton catalytic activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 29203–29212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Huang, R.; Yang, C.; Jiang, G.; Xiong, J.; Huang, Z.; Yuan, S. One-pot co-precipitation synthesis of Fe3O4 nanoparticles embedded in 3D carbonaceous matrix as anode for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 4212–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Hayes, P. Analysis of XPS spectra of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions in oxide materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, N.V.; Marchington, D.; McGowan, H.C.E. H2O2 determination by the I3- method and by KMnO4 titration. Analytical Chem. 1994, 66, 2921–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, T.; Liu, P.; Cui, P.; Hu, P. Manufacture of nano graphite oxides derived from aqueous glucose solutions and in-situ synthesis of magnetite graphite oxide composites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 153, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Murillo, D.H.; Ariza-Reyes, A.A.; Ardila-Vélez, L.J. Some kinetic and synergistic considerations on the oxidation of the azo compound Ponceau 4R by solar–mediated heterogeneous photocatalytic ozonation. Desalin. Water Treat. 2019, 170, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, S. Fenton-like oxidation of Malachite Green Solutions: Kinetic and thermodynamic study. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T (°C) | AR18 | AR66 | OR2 | ||||||

|

k1 (min-1) |

R2 |

Ea (kJ.mol-1) |

k1 (min-1) |

R2 |

Ea (kJ.mol-1) |

k1 (min-1) |

R2 |

Ea (kJ.mol-1) |

|

| 25 | 0.0056 | 0.980 | 36.2 | 0.0095 | 0.997 | 27.2 | 0.0122 | 0.979 | 25.3 |

| 40 | 0.0127 | 0.981 | 0.0153 | 0.992 | 0.0176 | 0.986 | |||

| 60 | 0.0262 | 0.994 | 0.0301 | 0.994 | 0.0353 | 0.994 | |||

| T (°C) | ΔH (kJ.mol-1) | ΔS (kJ.mol-1K-1) | ΔG (kJ.mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AR18 | |||

| 25 | 57.3 | 0.196 | -1.25 |

| 40 | -4.13 | ||

| 60 | -8.12 | ||

| AR66 | |||

| 25 | 43.3 | 0.157 | -3.37 |

| 40 | -5.64 | ||

| 60 | -8.84 | ||

| OR2 | |||

| 25 | 43.1 | 0.158 | -4.07 |

| 40 | -6.25 | ||

| 60 | -9.58 | ||

| Sample | Binding energy (eV) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe 2p3/2 | Fe 2p1/2 | C 1s | O 1s | S 2p | Fe3+/Fe2+ ratio | |||

| Fe3O4 [46] | 710.0 (18) |

724.9 (17) |

284.7(82) 286.0(12) 288.3(6) | 529.6(63) 531.0(29) 532.7(8) | 2.3 | |||

| Fe3O4/AR18 | 710.3 (17) |

724.8 (23) |

284.8(80) 285.3(12) 288.5(8) | 529.9(63) 531.4(28) 532.7(9) | 2.6 | |||

| Fe3O4/AR66 | 710.2 (19) |

724.7 (21) |

284.8(81) 285.3(13) 288.6(6) | 529.8(56) 531.4(28) 532.8(16) | 168.1 | 2.4 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).