Introduction

Limitations of Animal Models

Animal models are used to study diseases and their pathways. These models are based on the assumption that the pathways involved in the disease are conserved across different species, which means that the same genes and proteins are involved in the disease in both humans and animals. However, this assumption is not always true, and there may be differences in the pathways between species. Animal model relies on evolutionary conservation of pathway, limited by their inability to recreate human-specific processes. This is because there are many unique processes that contribute to brain development in humans that are not present in animals. For example, the development of the human cerebral cortex is much more complex than that of other animals. Therefore, animal models may not accurately reflect the processes involved in human brain development and disease.This can lead to inaccurate conclusions and hinder the development of effective treatments for human diseases.

2D Models of Psychiatric Disorders

2D models utilizing human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) offer a human-specific framework for investigating neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. These conditions are difficult to analyze using conventional animal models, due to their subjective symptoms and intricate genetic complex backgrounds. Further, patient-derived hiPSCs retain the individual’s genetic profile, allowing researchers to understand how genetic factors contribute to disease phenotypes. 2D hiPSC models have been used to better understand the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie a variety of pyschiatric disorders including ASD, SCZ, and BD [

3].

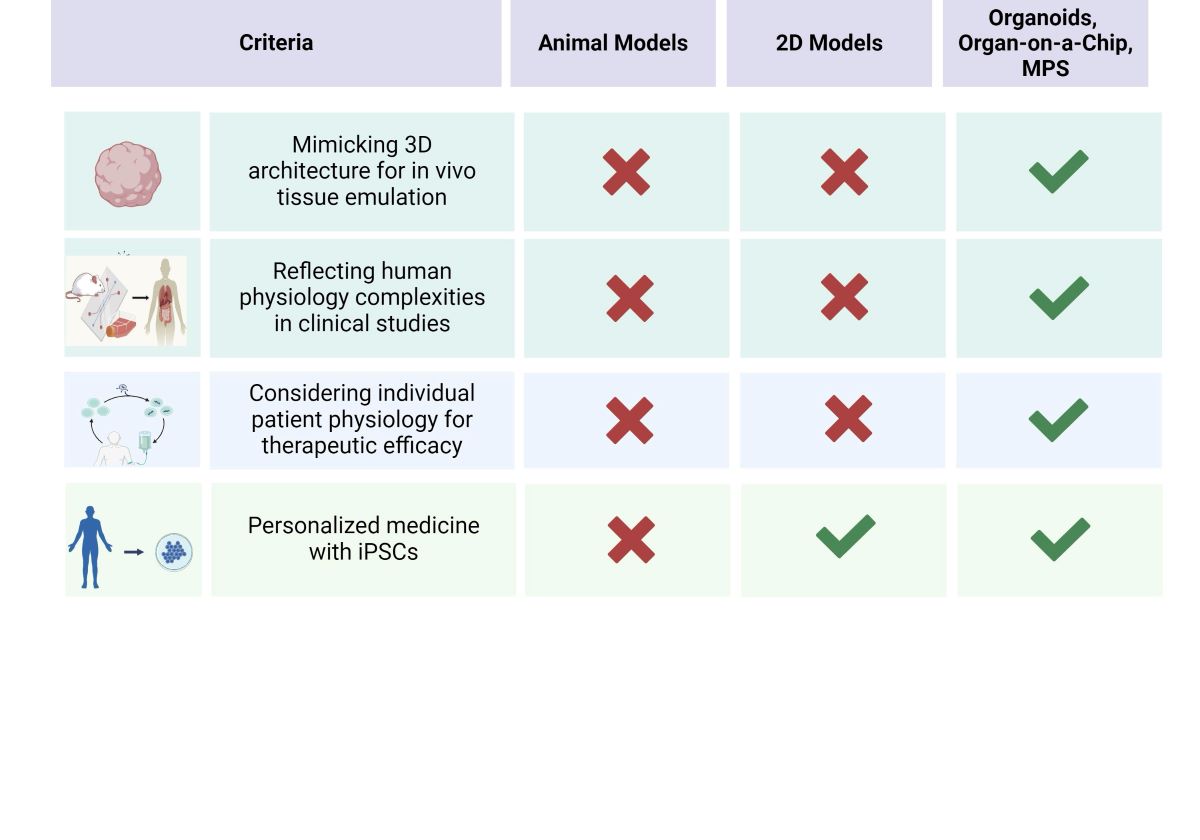

Table 1 summarizes this.

Coculturing, which merges various cell types in a single culture system, can be used to investigate how different cell types influence each other, termed non-cell-autonomous interactions. It also allows for the examination of contact-dependent and independent cell interactions [

4]. This enhances 2D models by more accurately mimicking the underlying mechanisms of neuropsychiatric disorder pathogenesis. Cocultures do have certain limitations, in that they lack tissue architecture, cell-type diversity, dynamic growth expansion, and maturation.

The main benefit of 2D models compared to 3D organoid models lies in their simplicity, reproducibility, and scalability, enabling larger experiments and more extensive high-throughput screening. However, the limitations of 2D cell culture models, including their lack of tissue complexity and inability to replicate key in vivo conditions, significantly limit their effectiveness in elucidating the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. These challenges underscore the critical need for organoid models that offer a more physiologically relevant and complex platform for understanding the intricacies of psychiatric disease mechanisms.

Idiopathic Autism Spectrum Disorder

iPSCs retain the unique genetic background of the individual which is paramount for studying ASD where roughly 80-85 percent of the population is idiopathic in origin. Research shows that neural cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), including both precursor cells and neurons that have undergone maturation, closely mimic the characteristics of human cortical cells during the embryonic stage, specifically between weeks 8 to 24. Therefore, these iPSC-derived neural cells serve as an ideal tool for investigating the initial stages of human neurodevelopment, especially when exploring genetically complex disorders such as autism [

5].

Synaptic Dynamics and Connectivity

In ASD, one of the key cellular phenotypes is altered synaptic formation and pruning. This leads to changes in neuronal connectivity, which are thought to underpin many of the behavioral characteristics of ASD [

6]. A 2021 study exploring the role of the innate immune complement system in ASD found that complement c4 was reduced in iPSC-derived astrocytes from people with ASD. Since astrocytes participate in synapse elimination, diminished c4 levels are associated with defective synaptic pruning, thus leading to atypically enhanced brain connectivity in ASD [

7].

Neuronal Differentiation and Maturation

In general, aberrant neuronal maturation, varied neuronal differentiation, and synaptic formation have been implicated in iPSC models focused on APD [

8]. Given the association between ASD and macrocephaly, excessive neural growth was also proposed to be associated with ASD. This has been demonstrated in iPSC models which showed increased neutral progenitor cell growth compared to controls. Additionally, this increased NPC growth in ASD individuals with macrocephaly was associated with an altered DNA replication program and increased DNA damage [

9]. Increased NPC growth was hypothesized to be due to the dysregulation of a beta-catenin/BRN2 transcriptional cascade. Neural networks formed from ASD-derived neuronal were found to be dysfunctional, characterized by abnormal neurogenesis and reduced synapse formation. Insulin growth factor 1, a drug in clinical trial for ASD, was able to rescue defects in this neural network, demonstrating the potential utility of iPSC models in modeling cellular mechanisms of therapeutic compounds [

10].

Glial Cell Function and Neuron-Glia Interactions

Additionally, there is evidence of increased activation of microglia and astrocytes in the brain, suggesting an inflammatory response. Co culture models investigating the interactions between neurons and astrocytes from individuals with idiopathic ASD using iPSCs have also been illustrative. ASD-derived neurons showed a significant decrease in synaptic gene expression and protein levels, glutamate neurotransmitter release, and reduced spontaneous firing rate. ASD-derived astrocytes interfered with proper neuronal development but this was rescued with control-derived astrocytes. Finally, blocking interleukin-6 secretion from astrocytes resulted in increased synaptogenesis in ASD-derived co cultures [

11].

Molecular and Genetic Signaling Pathways

In 2015, Griesi-Oliveira et al. performed the inaugural iPSC research on non-syndromic ASD, targeting a unique TRPC6 mutation. They discovered that disruption in TRPC6 caused diminished calcium signaling and led to abnormal neuronal development, marked by reduced neurite length and complexity, along with a scarcity of dendritic spines. Correcting these defects was achievable through either activating TRPC6 or enhancing its expression, highlighting TRPC6’s significance in ASD’s neurodevelopmental mechanisms [

12].

Neuroinflammatory Responses and Immune System Interactions

Emerging research into ASD points to neuroinflammation and immune system dysregulation as pivotal factors in understanding the disorder’s causes and progression. Research utilizing iPSC-derived neurons highlights the critical role of interferon-

(IFN-

) signaling in neurodevelopmental disorders. IFN-

influences neurite outgrowth by up-regulating MHCI genes via mediation by promyelocytic leukemia protein nuclear bodies. Additionally, it alters gene expression associated with autism and schizophrenia, underscoring the interaction between genetic and environmental factors [

13].

Neurotransmitter Systems and Imbalances

Imbalances in the excitatory-inhibitory neurotransmitter systems, particularly involving glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons, are also commonly observed in ASD. These imbalances can affect neural network functioning and are linked to the sensory and behavioral symptoms characteristic of the disorder. In a study utilizing co-cultures of iPSC-derived glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons, the focus was on Cadherin-13’s (CDH13) pivotal role in regulating the excitation/inhibition (E/I) balance. Findings indicate that a lack of CDH13 in GABAergic neurons leads to a disrupted E/I balance, primarily through enhanced inhibition [

14].

Transcriptomic and Proteomic Profiling

An examination of the transcriptome analysis was performed between normal controls and iPSC-derived neuronal cells from normocephalic ASD. Researchers identified dysregulation in gene modules associated with protein synthesis in neuronal progenitor cells (NPC), synapse/neurotransmission, and translation in neurons. Proteomic analysis of NPCs showed potential molecular links between these dysregulated modules in NPCs and neurons. A synapse-related module was consistently upregulated in iPSC-derived neurons (similar to fetal brain expression) and downregulated in postmortem brain tissues of ASD patients, pointing to its potential as an ASD biomarker and therapeutic target due to its varying dysregulation across developmental stages in ASD individuals. This research demonstrates that traditional 2D models, when integrated with newer technologies such as RNA-seq, transcriptomic analysis, differential gene expression profiling, and the prediction of temporal and regional identity of iPSC-derived neurons through machine learning algorithms, can still provide valuable insights into complex biological processes [

15].

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is characterized by significant disruptions in neuro-transmitter systems, particularly the overactivity of dopamine pathways in the brain. This over activity, especially in regions associated with reward and motivation, is believed to contribute to symptoms like hallucinations and delusions. Another critical aspect of schizophrenia is the dysregulation of glutamate neurotransmission. This involves particularly the NMDA receptors, which play a significant role in synaptic plasticity and memory. Structurally, schizophrenia is often associated with reductions in the volume of the cerebral cortex and alterations in the structure of specific brain regions, including the thalamus and hippocampus [

16].These changes may underlie many of the cognitive impairments observed in schizophrenia. iPSC models of schizophrenia have revealed alterations in neurogenesis, neuronal maturation, neuronal connectivity, synaptic impairment, mitochondrial dysfunction, glial cell dysfunction, and developmental impairments mediated by miRNAs [

17].

Aberrant activation of inflammasomes, dysregulation of glial cells, and brain inflammation have been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (SCZ) [

18]. Astroglia and microglia, as the brain’s resident immunocompetent cells, are central to ongoing research into immune abnormalities associated with SCZ. Notably, iPSC-derived astrocyte and astroglia studies [

18,

19,

20] highlight the critical involvement of these cell types in SCZ’s underlying mechanisms. This research highlights the importance of glial cells in mediating the inflammatory responses that may contribute to the disorder’s development and progression. Using SCZ iPSCs differentiated into atrocytes, researchers identified genes that were differentially expressed during development in SCZ-astocytes compared to controls. Then, they confirmed that these genes were up-regulated in the medial prefrontal cortex, striatum, and temporal lobes which have been previously implicated in SCZ. Additionally, SCZ astrocytes showed altered calcium signaling, decreased glutamate uptake, and metalloproteinase activity [

20].

Additionally, research has shown that inflammatory modulation, specifically through IL-1B exposure, affects iPSC-derived astrocytes differently in SCZ patients compared to healthy controls [

18]. IL-1B exposure altered pathways related to innate immune responses, cell cycle regulation, and metabolism in both SCZ and control astrocytes. However, significant differences were found in the expression of HILPDA and CCL20 genes which exhibited reduced up-regulation after IL-1B treatment in SCZ astrocytes compared to healthy controls. This implies that the dysregulated immune activation and inflammation in SCZ could be, in part, related to a possible disruption in the astroglia-CCL20-CCR6-Treg axis [

18].

Another study conducted a comparative analysis of miRNA expression in iPSC-derived astrocytes from SCZ patients and healthy controls, both at baseline and after inflammatory stimulation. They identified several miRNAs that exhibited significantly lower baseline expression relative to controls [

19]. These findings were validated by analyzing gene expression in blood samples from a large group of SCZ patients and controls. After screening for the expression of specific gene targets of the miRNAs, they found several genes that were down regulated in the blood of SCZ patients compared to controls. These findings highlight the critical role of astrocytes and astroglia in mediating synaptic and inflammatory processes in SCZ, presenting new avenues for understanding and potentially treating the complex pathobiology of this disorder [

18,

19,

20].

Studies involving cultured interneurons differentiated from iPSCs of SCZ patients both showed mitrochondrial dysfunction, altered synaptic structure, and oxidative stress. Additionally, both these studies showed that these neuronal deficits could be rescued with therapeutics which target oxidative stress or mitochondrial dysfunction [

21,

22].

Cortical interneurons (cINs) derived from patient iPSCs exhibited lower levels of the enzyme glutamate decarboxylase 67 and synaptic proteins, including gephyrin and neuroligin-2 (NLGN2). When these interneurons were co-cultured with excitatory cortical pyramidal neurons also derived from SCZ patient iPSCs, a notable reduction in synaptic puncta density and a decrease in action potential frequency was observed. Crucially, the reduction in NLGN2 was identified as a key factor in diminishing puncta density, as its overexpression successfully reversed these deficits. Furthermore, treatment with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine not only increased NLGN2 expression levels but also improved synaptic deficits and signs of oxidative stress [

21]. In a related study, cortical cINs derived from iPSCs from both healthy controls and individuals with SCZ were co-cultured with activated microglia to examine the effects of prenatal immune activation, a known SCZ risk factor. The interaction with activated microglia led to disrupted metabolic pathways, impaired mitochondrial function, reduced arborization, and decreased synapse formation and synaptic GABA release in cINs. Mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced branching in neurons, induced by activated microglia, could be reversed with alpha lipoic acid and acetyl-L-carnitine. While healthy control neurons were affected by the activated microglia, neurons from individuals with SCZ were not, suggesting a unique interaction between SCZ genetics and environmental factors. Even after removing the microglia, SCZ neurons exhibited lasting metabolic issues, demonstrating a potential vulnerability specific to SCZ [

22]. These studies identify synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction in cortical interneurons as key mechanisms in SCZ, suggesting potential avenues for future therapeutic intervention [

23].

Finally, recent studies showed that SCZ-related deficits in dendritic spine density are associated with altered gene expression, particularly the NRXN3 204 isoform, in iPSC-derived cortical neurons. The findings align with postmortem analyses and suggest that modulating NRXN3 204 expression, potentially with treatments like clozapine, could address synaptic abnormalities in SCZ.

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder (BD) presents a complex picture involving neurotransmitter imbalances and neural plasticity dysfunctions. Neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine play a crucial role, similar to their involvement in anxiety disorders. Fluctuations in these neurotransmitter levels are thought to contribute to the mood swings experienced in bipolar disorder. Additionally, abnormalities in neural plasticity are a key feature, often indicated by altered levels of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor). These changes can affect neuronal growth and survival, impacting mood regulation and cognitive functions [

24].

Dysfunctions in ion channels, particularly those involved in calcium signaling, are also linked to bipolar disorder, influencing neuronal excitability and neurotransmitter release. Store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) is a mechanism for regulating intracellular calcium levels and is crucial for central nervous system development and many aspects of neuroplasticity [

25]. Calcium and developmental dysregulations related to SOCE were noted in BD-NPC and cortical-like glutamatergic neurons derived from BD-iPSC’s. Additionally, RNA-sequencing identified a unique transcriptome profile in BD-NPCs, suggesting that BD resulted in accelerated neurodifferentiation. The researchers also identified high expression of microRNAs let-7 and miR-34a in BD NPCs and BD neurons, respectively. Both have been implicated in BD etiology and neurodevelopmental deviations [

26].

Similar to SCZ, astrocytes and their impact on the inflammatory state of the brain have been implicated in BD. BD-iPSC derived astrocytes exhibited altered transcriptional activity and were less supportive of neuronal activity both at baseline and with inflammatory stimulation compared to controls. Additionally, neuronal activity decreased during co-culture with IL-1

-stimulated astrocytes Administration of an IL-6 blocking antibodies rescued this neuronal activity, suggesting that IL-6 paritially mediated the effects of activated astrocytes on neuronal activity [

27].

iPSCs derived from patients with bipolar disorder have been utilized to better understand the cellular behaviors and differential gene expression between lithium responders (LR) and non-responders (NR) [

3,

28,

29]. This research has generated novel insights into the molecular mechanisms of mood stabilizer function with focal adhesion, oxidative phosphorylation, and spliceosome modifications being implicated in therapeutic response.

In 2023, researchers used a network-based multi-omics approach to analyze iPSC-derived neurons from LR and NR which revealed significant differential gene expression related to focal adhesion and ECM. They posit that disrupted focal adhesions could impact axon guidance and neuronal circuits which may underpin mechanisms of response to lithium and underlying BD [

28].

BD iPSC derived hippocampal dentate gyrus neurons have been shown to be electrophysiologically hyperexcitable. Functional analysis showed that there are significant differences in intrinsic cell parameters between LR and NR patients, suggesting the existence of BD subtypes. One discovery across both groups is the presence of a large, fast after-hyperpolarization, underscoring its potential role in BD’s neurobiology. Furthermore, lithium’s ability to modulate this hyperexcitability in LR patients reaffirms its therapeutic relevance, offering insights into BD’s underlying mechanisms and treatment responsiveness [

3].

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders are characterized by a complex interplay of neurotransmitter imbalances and structural brain alterations. Neurotransmitters such as serotonin, GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), and norepinephrine are central to the development of these disorders. Serotonin, often linked to feelings of well-being, is typically found to be dysregulated in anxiety conditions. GABA, the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, plays a crucial role in managing neuronal excitability and, when imbalanced, can lead to heightened anxiety states. Norepinephrine, which is involved in the body’s stress response, is also often dysregulated [

30].

From a structural perspective, anxiety disorders are frequently associated with changes in the hippocampus and amygdala, key regions for processing fear and stress. The hippocampus, vital for memory and emotional regulation, may undergo functional and structural modifications, while the amygdala, central to the fear response, can exhibit hyperactivity. Chronic stress, a common trigger for anxiety disorders, can lead to the dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, influencing cortisol levels and further contributing to the symptomatology of these disorders [

30].

Animal models of anxiety, compared to all the other mental disorders, are generally the most amenable to translation because fear and anxiety are highly tractable in the laboratory [

31]. However, the differences between human and animal biology has limited their effectiveness in identifying psychopharmacological treatments and limited the ability to test more novel treatments like neurostimulation. Furthermore, nonhuman animal models fall short due to the dubious nature of ascribing human psychiatric diagnosis criteria to a nonhuman animal and the inability to observe complex cognitive processes in animal test subjects that cannot self-report their mental state.

Depression

In depression, a notable reduction in hippocampal volume is a common observation. This reduction is critical, as the hippocampus plays a significant role in emotional processing and memory formation. The prefrontal cortex, integral for mood regulation and decision-making, also shows altered activity and, in some cases, atrophy in individuals with depression. These structural changes are thought to contribute to the cognitive and emotional symptoms characteristic of depression [

32].

Neurotransmitter systems involving serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine are frequently implicated in depression. Imbalances in these neurotransmitters can disrupt mood regulation and lead to depressive symptoms. Moreover, depression is often associated with a reduction in neuroplasticity. This includes decreased neurogenesis, particularly in the hippocampus, and a reduction in synaptic plasticity, which can affect learning, memory, and mood regulation [

32].

While iPSC models for depression are less commonly employed than for bipolar, autism, or schizophrenia, their application in exploring the differential effects of therapeutics for major depressive disorder has already proven valuable. For instance, prefrontal cortical neurons from depression patient iPSC’s were cultured and subsequently used to screen for the effectiveness of bupropion, a commonly used antidepressant. Biomarkers specific for response to the medication were discovered including specific gene expression alterations, synaptic connectivity and morphology changes [

33]. In another study, serotonergic neurons from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) iPSCs in both SSRI-remitters and non-remitters were generated. Then, their resistance to selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) was studied. Non-remitters were found to have altered neurite growth and morphology downstream of lowered expression of protocadherin alpha genes compared to controls and remitters. Knockdown of protocadherin alpha genes improved iPSC-derived neurite length and morphology further implicating its role in SSRI resistance [

34]. A related study using iPSC derived neurons from MDD SSRI NRs displayed serotonin-induced hyperactivity downstream of up-regulated serotonergic receptors compared to SSRI-Rs [

35]. This result implies that differences in serotonergic neuron morphology and the resulting circuitry may impact SSRI resistance in MDD patients [

35].

These studies show how iPSC depression models can be utilized to predict patient response to psychiatric medications and probe MDD’s molecular phenotype. Another related avenue of research is the relationship between chronic stress and MDD. To model this interaction, iPSC-derived astrocytes were treated with cortisol for 7 days to mimic chronic stress exposure in vitro. Then, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between MDD-iPSCs astrocytes and control astrocytes in response to stress were identified. The researchers found that genes related to GPCR ligand binding, synaptic signaling, and ion homeostasis were differentially expressed. This modelling approach, alongside the pinpointed DEGs, warrant future study to further elucidate the cellular and molecular mechanisms that mediate the impact of stress in the brain [

36]. Similar research looking at the importance of glucocorticoid signaling in iPSC-derived cortical neurons identified the gene CDH3 as being critically implicated in the cellular response to chronic stress [

37]. Overall, iPSC models hold potential in unraveling the mechanisms behind MDD, offering insights into antidepressants effectiveness, SSRI resistance, and the relationship between chronic stress and MDD.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD shares some cellular phenotypes with depression, such as a reduced volume of the hippocampus. This reduction may contribute to the memory disturbances typically observed in PTSD. The amygdala, crucial for processing fear and emotional responses, often exhibits heightened activity in PTSD, correlating with the heightened vigilance and fear responses characteristic of this disorder. Another key feature of PTSD is the dysregulation of the HPA axis, which leads to abnormal cortisol patterns [

38]. Glucocorticoid dysregulation can affect the body’s stress response system, contributing to the persistence of PTSD symptoms and impacting other bodily systems. To simulate glucocorticoid dysregulation seen in PTSD, iPSCs were differentiated into cortical neurons under dexamethasone (DEX) treatment, activating glucocorticoid receptors to mimic stress responses. This method also involved tracking gene expression changes through the stages of differentiation from iPSCs into neural stem cells, immature neurons, and finally cortically neurons. The analysis identified DEGs among the DEX treated neurons including canonical glucocorticoid receptors genes like FKBP5 and non-glucocorticoid genes like the serotonergic gene TPH2. Additionally, the expression of glucocorticoid-related genes, crucial for understanding PTSD, showed greater sensitivity in mature neural cells compared to their immature counterparts. This suggests that mature neural cells provide a more effective model for studying PTSD in vitro [

39]. In 2022, a study demonstrated that glutaminergic neurons derived from iPSC lines from PTSD patients exhibit a heightened sensitivity to levels of glucocorticoids in the body, especially at low levels [

40]. A similar study found that glucocorticoid signaling pathways were differentially enriched in PTSD in iPSC-derived cortical neurons compared to MDD, especially in excitatory neurons [

37]. As the majority of trauma survivors do not develop clinically diagnosed PTSD, these findings may support the diathesis-stress model of many psychiatric disorders in which certain individuals are born with cellular phenotypes that predispose them to developing a disorder when exposed to a certain environmental trigger.

Limitations of Modeling Psychiatric Disorders in 2D

While studies of 2D in vitro iPSC models of psychiatric disorders have yielded valuable findings, they face the fundamental limitation of failing to capture the full complexity of cell-cell interactions that exist in 3D, in vivo settings. In 2D culture, neurons can only form connections in 2D planar space, due to being restricted by the surface of the culture plate below them. The removal of the third dimension not only greatly reduces the number of possible connections between the cultured neurons, but also causes every cell to be in contact with an unnatural, stiff, and flat surface. Most psychiatric disorders display some degree of alterations to cell phenotype in the form of abnormal growth and development of neuronal connections and abnormal neurotransmitter signaling, and 2D conditions cannot fully capture these complexities due to the aforementioned restrictions on growth and cell-cell communication.

3D Models: Organoids

Organoids are 3D structures derived from human stem cells in vitro that mimic the complex biological functions of real organs. This technology represents a significant leap from traditional two-dimensional cell cultures, offering a more accurate and dynamic model for studying patient-specific developments, disease processes, and drug responses. Typical brain organoid models are differentiated from iPSCs in a stepwise manner and grown in Matrigel or other ECM analog using Lancaster’s protocol and the hanging drop method.

In this review, we focus on psychiatric disorders and the advances in integrating cerebral organoids into the disease-modeling research framework. We discuss the typical cellular phenotypes of multiple psychiatric disorders such as ASD, SZ and BD. We aim to identify the advantages of 3D modeling over 2D modeling and discuss the recent studies performed using these models in various neuropsychiatric diseases.

Psychiatric disorders are as such extremely difficult to study and its diagnosis involves components like environment, mood and psychosis. It is very difficult to translate this in an accurate manner to gain complete understanding. The absence of markers like cerebrospinal fluid, brain imaging and EEGs unlike those in neurological disease complicates it further. One way to robustly replicate the disorder is through using 3D models like cerebral organoids as they have the ability to self-organize. These models focus on modelling cellular aspects of the disorder such as cell proliferation, migration, lineage trajectory and differentiation.

Specifically, cerebral organoids have been used by researchers to understand and observe abnormalities in abnormal psychiatric conditions, model brain development, and as frameworks for preclinical drug testing regimens and personalized medicine [

42]. Since commonly highlighted psychiatric disorders such as ASD, SZ, anxiety, depression, PTSD and BD involve multiple brain regions, cerebral organoids specific to particular regions can be cultured using human induce pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and fused to form assembloids. This is a powerful tool for scientists to identify multiregional affects and how the connectivity between them contributes towards the disorder, defects in cellular organization and the underlying biological [

43,

44].

Table 2.

Summary of Cellular Phenotypes in 3D Models.

Table 2.

Summary of Cellular Phenotypes in 3D Models.

| Disease |

Cell Type |

Region |

Observations/Findings |

References |

| BD |

Neural Progenitor Cells |

Cortex |

Store-operated Ca release dysregulated and attenuated in BD NPC lines compared to controls. Thinning of subventricular zone observed in BD organoid lines. |

[26] |

| BD |

Neurons |

Cortex |

Enrichment of genes related to ion storage and homeostasis in BD-derived cortical organoids. Store-operated Ca release dysregulated and attenuated in BD cerebral organoids. BD-derived cortical organoids contain lower proportions of neurons and elevated numbers of radial glial cells. Decreased neuron excitability observed in BD-derived cortex organoids but excitability was rescued by treatment with lithium. DEGs between treated and untreated organoids associated with Na+ homeostasis and regulation of IL-β and TNF-α. |

[26,62,63] |

| BD |

Excitatory Cortical Neurons |

Cortex |

BD Type I-derived organoids display downregulation of cell adhesion associated with abnormal NCAN expression, and downregulation of genes associated with GABA uptake/release. ER-Mitochondria contact sites markedly reduced in BD-derived organoids compared to controls, in both perinuclear region and neurites. |

[61] |

| SCZ |

Neurons |

Cortex (Dorsal Forebrain), Ventricles |

GWAS studies by Kathuria et. al. reveal 23% of genes are differentially expressed in SCZ organoids compared to controls. Significant decreases in mitochondrial activity and cellular respiration are observed in SCZ organoid lines. MEA studies reveal diminished response to stimulation/depolarization in SCZ organoids. BRN2 and PTN are depleted in Scz neurons relative to controls. |

[53,55] |

| SCZ |

Non-Neurons |

Ventricles |

Elevated numbers of cells in ventricular regions of SCZ organoids directed towards myeloid, mural, and endothelial lineages in comparison to controls. |

[53] |

| SCZ |

Neurons |

Thalamus, Cerebellum |

Impaired connection between medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus and cerebellum |

[44] |

| ASD |

Excitatory Neurons |

Cortical Plate |

Elevated numbers of cortical plate excitatory neurons (ENs) in macrocephalic ASD lines at the expense of preplate ENs, which were diminished. Cortical interneurons are also overproduced in comparison with controls due to DLX6 overexpression. |

[49,64] |

| ASD |

Radial Glial Cells |

Cortical Plate |

Lamination of cortical plate is reduced, and cortical projection neuron maturation is accelerated in SYNGAP1 haploinsufficient organoids. Similar findings observed in vivo in mice. |

[49] |

| ASD |

NPCs |

General |

Excessive growth of NPCs due to mutations in genes such as SUV420H1, CHD8, and PTEN associated with ASD risk and macrocephaly. |

[46,47,48] |

| ASD |

GABAergic Neurons |

Cortex |

Overexpression of GABAergic pathways in ASD organoids results in heightened percentages of GABAergic neurons (as high as 50% of all cells in the organoid) compared to controls. |

[46,48] |

Idiopathic Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorders are characterized by an array of symptoms that can range from mild to severe, including repetitive behaviors, social interaction difficulties, and impaired neurodevelopment. This review focuses on idiopathic autism spectrum disorders, which occur spontaneously and have unclear and polygenic causal factors, intriguing scientists. Studying these complexities requires a comprehensive understanding of brain development and the relationship between cellular and molecular results associated with clinical symptoms.

Previous sections have highlighted extensive studies using 2D and animal models, but the limitations of both hinder the clinical translation of findings. Studies have shown that culturing cells in monolayers alters their genetic expressions. In rodent models of ASD, neurons originate from the subventricular zone, whereas in humans, they originate from proliferative regions outside this zone [

45]. To bridge species-specific differences, human brain organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are now being modeled to gain deeper insights into the etiology of autism spectrum disorder.

Macrocephaly is one of the most well-studied phenotypes associated with ASD, leading researchers to use organoids in studying its etiology. Brain organoids derived from individuals with macrocephalic ASD show larger sizes compared to control organoids due to the involvement of tumor suppressors such as PTEN, CHD8, and RAB39B. This increase in organoid size is also attributed to the overexpression of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) caused by impaired maturation during development [

46]. In particular, organoids derived from a cells with shortened form of CHD8 contribute to the increase in organoid size and are implicated in macrocephalic autism, along with abnormal PTEN and SUV420H1 expression, an imbalance of neuronal types and increased differentiation of GABAergic neurons [

46,

47,

48].

Additionally, organoid models have implicated imbalances in neuronal subtypes as possible causes for behavioral symptoms of autism. The overexpression of upper-layer colossal projection neurons, which are responsible for human social behavior, is observed in autism and can be further explored using organoid models. Cortical organoid models were created to illustrate that the expression of SYNGAP1 in human radial glia is reduced in individuals with ASD. This reduction impacts the lamination of the cortical plate and influences the maturation of cortical projection neurons [

49]. Additionally, increased expression of DLX6 leads to the overproduction of cortical interneurons compared to control organoids. Cortical organoids derived from iPSCs affected by idiopathic ASD show upregulated expression of the transcription factor forkhead box G1, leading to shortened cell cycle length, abnormal cell proliferation, and unbalanced neuron differentiation. The imbalance between inhibitory and excitatory neurons during early development suggests accelerated brain growth in the second trimester [

50]. This imbalance is also studied in forebrain organoids, comparing the cellular and molecular profiles of macrocephalic and non-macrocephalic ASD. The analysis concludes that there is an overlap between the two in terms of upregulated genes in transcription, with patient-derived organoids showing decreased cortical area-specific transcripts [

51]. The size of organoids is also assessed using proteomic techniques and time-point assessments [

52].

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia, a neurodevelopmental disorder with an varied molecular origin, was initially modeled in 2011 using patient-derived hiPSCs carrying mutated DISC1 genes. Subsequent research delved into investigating dysregulation in synapse-associated gene transcription, defective synaptic vesicle release, cell cycle regulation, and its impact on cortical size. Progress in this area led to the utilization of 3D modeling techniques, specifically cerebral organoids, to dissect the cellular phenotype of schizophrenia. In 2011, the Gage lab demonstrated neuronal phenotypic changes derived from patient cells, revealing reduced neuronal connectivity, decreased levels of PSD-95 protein, alterations in glutamate expression, and dysregulation in cAMP and Wnt signaling pathways. These advancements transitioned into using organoid models and conducting cell patterning assays, which identified decreased connectivity between the medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus and cerebellum in schizophrenic patients [

44]. Presently, organoid models mimicking neuropathology of schizophrenia are employed to assess risk factors such as amalgamate, PTN, and BRN2 [

53]. Other research has focused on patterning, time-dependent organoid generation, abnormal distribution of proliferating (Ki67+)neural progenitor cells, and the role of genes like FGFR1 in cortical development [

54]. In addition, studies have identified DEGs associated with significant decreases in mitochondrial activity and cellular respiration in SCZ organoid lines [

55,

56].

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder (BD), a neuropsychiatric condition, remains poorly understood in terms of its structural, cellular, and circuit-level characteristics. The absence of clear diagnostic biomarkers and the complexity of its behavioral traits pose significant challenges for treatment [

57]. Given its involvement in higher-order brain functions and the presence of multiple cell types across various brain regions like the thalamus, cortex, and basal ganglia, utilizing 3D models such as cerebral organoids offers a potent strategy for analysis. Studies on patient-derived samples have revealed dysregulated genes and signaling pathways such as the Wnt pathway, which has also been observed in other neuropsychiatric disorders. BD-derived organoids exhibit reduced neuron count, resulting in decreased excitability and network activity, along with smaller size. Additionally, there is evidence of overexpression of genes related to membrane receptors and calcium channels [

58]. Lithium has been used as a treatment in bipolar disorder for its mood-stabilizing properties; however, its mechanism was not completely understood until studies were performed using brain organoids. In patient derived organoids, the administration of lithium increases excitability, neuroprotection, mitochondrial reverse capacity and regulated pro-inflammatory cytokine secretions. This helped to identify Li-associated DEGs (differentially expressed genes) which can serve as targets for drug delivery [

59]. iPSC-derived cerebral organoids from patients serve as a valuable model to understand aberrations in ER biology and electrophysiological responses, as well as the dysregulation of cell adhesion, upregulation of immune signaling genes, and neurodevelopmental aspects in bipolar disorder [

60,

61].

Limitations of 3D Models

Despite their numerous advantages over 2D models, 3D models of psychiatric diseases face a number of limitations that must be addressed before they can become more widely used in basic and clinical research. The small size of organoids means that there is still a significant discrepancy between the behavior of organoid cultures and the complex electrophysiology of the human brain. Notably, the existing body of research concerning cerebral organoids and their applications has focused primarily on cortex neurons. As dysfunctional circuits involving multiple non-cortical brain regions have been theorized to contribute to the etiology of many psychiatric disorders, we speculate that the use of assembloids of both cortical and non-cortical brain regions would improve the similarities to physiological conditions.

Furthermore, organoid models often display a greater degree of structural similarities to fetal organs rather than their adult counterparts, as a consequence of being grown from naive iPSC cultures over the span of only a few months. Specifically, this can be problematic for the prospects of using organoid models in psychiatric research, as most mental disorders have an onset between adolescence and young adulthood.

Finally, because the body of research using 3D models is relatively small compared to that concerning 2D iPSC models, there exist fewer methods for characterization and analysis. For example, 2D iPSC neuron cultures are commonly analyzed using microelectrode arrays (MEAs). These systems which are designed for recording electrical potentials of flat monolayer cultures are not suitable for doing the same with 3D organoids. However, some recent research such as that of Huang and Gracias et al. (2022) [

65] has explored multistep microfabrication methods for microscale Shell MEA devices that can wrap around a single organoid, transmitting measurements from multiple spatial directions in a limited capacity. The group demonstrated that this device could be used to measure the signals from a single cerebral organoid, both before and after treatment with glutamate.

Future of 3D Models

Drug Testing and Personalized Medicine

In the academic realm, brain organoids are employed to investigate the genotype and phenotype of complex neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric conditions. By comparing control organoids with disease organoids, researchers aim to identify new drug targets for these disorders. Utilizing 3D models enables the examination of drug components, with the goal of potentially replacing the need for animal models in drug testing.

For instance, the effects of lithium on mechanisms and pathways implicated in bipolar disorder have been explored using patient-derived brain organoids. Similarly, CRISPR technology is utilized to suppress entry receptors of the Zika virus in cerebral organoids. Neurotherapeutic companies utilize iPSC-derived cerebral organoids for phenotypic-based drug discovery targeting psychiatric diseases. Collaborations between institutes like IMBA and academia fund studies on loss-of-function mutations in SCN1A, a sodium channel gene associated with epilepsy in Dravet syndrome [

66].

The complex nature of idiopathic autism spectrum disorder presents challenges in using patient-derived organoids for drug testing. However, for syndromic ASDs, cerebral organoids serve as useful platforms. Drug testing on organoids has shown promising results, such as the reduction in tumor size with mTOSR complex inhibitor and EGFR kinase inhibitors, Everolimus and Afatinib respectively. Additionally, experiments administering topoisomerase inhibitors to cerebral organoids have revealed reduced expression of UBE3A-ATS, indicating potential implications for autism spectrum pathology. Investigations into IGF treatments for ASD are also underway using these models [

47].

Transcriptomic profiling of iPSC-derived telencephalic organoids from pediatric bipolar disorder patients has identified dysregulated PLXNB1 gene signaling as a contributing factor [

67]. Furthermore, leaky channels implicated in bipolar disorder have been studied using patient-derived models [

68]. Wolfram syndrome is a neuropsychiatric disorder caused due to WFS1 deficiency in astrocytes, this causes delayed neuronal differentiation, disrupted synapse formation, hampers neurite growth. Cerebral organoids from hESC patient cells are used to study Riluzole, a drug which induces EAAT2 restoration in astrocytes and reverse disorder effect [

69]. However, further examination is required to fully assess the utility of these models in drug testing and discovery.

Brain organoids derived from patient-specific iPSCs offer a valuable platform for personalized medicine. As previously mentioned, they represent a potent tool for drug development targeting conditions like Zika virus-associated microcephaly, autism spectrum disorder, and glioblastoma. Glioblastoma, an unresectable brain cancer characterized by high genetic diversity, can be better understood by isolating glioma stem cells from patients and cultivating glioma organoids. These organoids mimic key features of gliomas in vivo, including cell types and hypoxic gradients [

70]. Additionally, the introduction of the HRas oncogene through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homogenous recombination has been utilized to generate glioma organoids. These models have been instrumental in studying factors influencing the tumor microenvironment [

70]. Besides brain organoids, 3D models derived from other tissues like the colon, liver, and prostate have also demonstrated promising applications in personalized medicine [

71]. Establishing biobanks of these organoids is crucial for enabling high-throughput screening, epigenomic analysis, and transcriptional profiling. However, the creation of biobanks specifically for patient-derived organoids remains a pending task [

72].

Neural Toxicology

The resemblance of 3D brain organoids to the architecture of the human brain offers potential for their utilization in drug development. However, ethical considerations limit the accessibility of human embryos for research purposes, making organoids crucial in mimicking pathophysiology and enabling scientists to evaluate the toxic effects of chemicals, new drugs, and other substances. These toxins are directly administered into brain organoid cultures, and their effects on function, morphology, and transcription are subsequently analyzed. Drugs prescribed during pregnancy can directly impact fetal neural development, increasing chemical exposure and the risk of neurological disorders [

73,

74].

A study in 2019 investigated the dose-dependent effects of vincristine on brain organoids, concluding neurotoxicity and inhibition of tubulin and fibronectin development in cerebral organoids [

75]. Another study in 2020 assessed the neurotoxic effects of the common food contaminant acrylamide using brain organoids, revealing increased NRF2 activity, promotion of tau hyperphosphorylation, and reduced neuronal differentiation upon prolonged exposure [

76]. In 2021, a comparative study evaluated the impact of 4-hydroxybenzophenone on brain organoids derived from iPSCs versus rodents, demonstrating reduced proliferation rates and induced necrosis in the organoids, while postnatal exposure to 4HBP in animal models caused apoptosis in hippocampal neural stem cells and cognitive dysfunction [

77].

Additionally, researchers investigated the effects of maternal alcohol exposure on fetal development using an in vitro system of brain organoids to study fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). Patient-derived cells were used to form organoids for pathophysiological studies, revealing alcohol-induced dysfunction in mitochondria and metabolic stress in the organoids, along with alterations in the expression of 199 genes out of 17,195 involved in neurodevelopment [

78]. Organoids also act as tools to study the effects of other compounds such as morphine on early development of brain [

79]. Prolonged exposure to cadmium, an environmental pollutant, led to reduced cerebral organoid size, damaged GFAP expression, decreased CTIP2 expression, reduced production of SOX2 neural progenitor cells, increased production of immature neurons, and impaired copper and zinc ion levels, ultimately affecting synaptogenesis [

80]. As organoids replicate neural networks, using multielectrode assays, these networks can be studied to understand neurotoxic effects of compounds [

81].

Brain-Computer Interfaces

Research has explored the similarity in cell types between 6-month-old self-assembling brain organoids derived from patient iPSC lines and those found in human brains by detecting protein markers characteristic of these cell types [

55]. The subsequent phase involves assessing the functionality of the cells, typically done by examining their electrophysiological activity. A 12-month-old organoid exhibits comparable features such as extensive electrophysiological activity, cell density, axonal myelination, and gene expression related to memory and learning. With these properties in place, there is potential to integrate brain organoids with artificial intelligence using bioengineering techniques like microfluidics and biosensing [

82]. In 2023, Cai H. et al. developed Brainoware, a living AI hardware based on the computational capabilities of 3D biological neural networks within brain organoids [

83]. This demonstrates how 3D organoids can help address artificial intelligence bottlenecks. Brain organoids can undergo training by interfacing with computers, gauging their responses to complex sensory inputs and outputs through sensors, computers, and machine interfaces. This emerging field is termed organoid intelligence [

82].

Tissue Engineering and BioMEMS Applications

Humanized brain organoids can be bioengineered using methods such as scaffolding, 3D bioprinting, and organ-on-chip techniques. Scaffolds, synthetic structures designed to support cell growth into functional tissues, can be made from various biomaterials, both natural (e.g., agarose, Matrigel, collagen) and synthetic (e.g., PEG, PEO, PVA). Computer-aided processes can generate components using 3D printing, enabling the printing of live cells and biomaterials for tissue construction. This bottoms-up approach is valuable for tissue engineering of structures that replicate living physiology [

84]. Additionally, microfluidic cell culture devices, known colloquially as “organ-on-chips”, can replicate organ-specific functions, allowing detailed studies of vasculature, brain structure, circulation, and their effects. When used in combination with organoids, these systems can integrate sensors for applications such as studying neurotoxicity, neural circuit activity [

85,

86], region-specific diseases, disease modeling, drug development, and personalized medicine [

87].

Conclusion

The inherent subjectivity of neuropsychiatric disorders has driven scientific researchers to develop better models that enhance our understanding of these complex conditions. The absence of standardized outcomes, coupled with unclear mechanisms underlying these disorders, underscores the need for further investigation. Here in this review, we have explored the cellular phenotypes associated with various neuropsychiatric disorders, including idiopathic autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, depression and PTSD. Differences in cellular and molecular pathophysiology between animal models and humans often prevent the direct translation of animal study findings to human applications. To address this limitation, researchers have increasingly turned to utilizing patient-derived iPSCs. These iPSCs can be differentiated into a variety of neuronal cell types and co-cultured, allowing for the observation of alterations in cellular phenotypes. Crucially, iPSCs derived from individuals with neuropsychiatric disorders retain the donor’s unique genetic profile, allowing researchers to explore how genetic predispositions interact with environmental factors to influence brain development. Unfortunately, these 2D models lack the necessary complexity to fully recapitulate the intricate dynamics of neuropsychiatric disorders in vitro. Consequently, the development of 3D models, such as brain organoids, has become crucial. These 3D models are formed based on three fundamental processes—tissue engineering, 3D cell culture, and neural differentiation. Due to their highly level of complexity, these models offer enhanced fidelity in modeling human neuropsychiatric disease.

Clinical Perspective

In severe mental illness, the complex interplay between genetic factors and environmental stressors, including infectious agents and associated immune dysregulation, throughout the developmental trajectory is crucial [

88,

89,

90]. Many critical risk factors for adult-onset mental illness, such as schizophrenia and mood disorders, impact the brain during early development. iPSC-derived 3D organoids offer a unique advantage in studying these interactions from a temporary perspective. More importantly, by using iPSC-derived 3D organoids, we may have an opportunity to assess the impact of genetic factors, environmental stressors, and gene-environmental interaction in a circuitry- and context-specific manner. Environmental factors often affect glial cells, which in turn influence neurons, and these complex interactions can be more effectively studied in the organoids [

91,

92,

93]. Finally, such 3D information will open up an opportunity of linking the molecular/cellular information to human brain imaging data, such as fMRI observations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and COVID-19, Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2022.

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx).

2022.https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd‐results/.

- Stern, S.; Santos, R.; Marchetto, M.C.; Mendes, A.P.D.; Rouleau, G.A.; Biesmans, S.; et al. Neurons derived from patients with bipolar disorder divide into intrinsically different sub-populations of neurons, predicting the patients’ responsiveness to lithium. Mol Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteley, J.T.; Fernandes, S.; Sharma, A.; Mendes, A.P.D.; Racha, V.; Benassi, S.K.; et al. Reaching into the toolbox: Stem cell models to study neuropsychiatric disorders. Stem Cell Reports 2022, 17, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkalj, L.; Mehta, M.; Matteson, P.; Prem, S.; Williams, M.; Connacher, R.J.; et al. Using iPSC-Based Models to Understand the Signaling and Cellular Phenotypes in Idiopathic Autism and 16p11.2 Derived Neurons. In DiCicco-Bloom, E.; Millonig JH (eds). Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Employing iPSC Technologies to Define and Treat Childhood Brain Diseases. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020, pp 79-107.

- Beopoulos, A.; Géa, M.; Fasano, A.; Iris, F. Autism spectrum disorders pathogenesis: Toward a comprehensive model based on neuroanatomic and neurodevelopment considerations. Front Neurosci 2022, 16, 988735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansur, F.; Teles e Silva, A.L.; Gomes, A.K.S.; Magdalon, J.; de Souza, J.S.; Griesi-Oliveira, K.; et al. Complement C4 Is Reduced in iPSC-Derived Astrocytes of Autism Spectrum Disorder Subjects. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, J.; Coppola, G.; Zhang, P.; Abyzov, A.; Provini, L.; Tomasini, L.; et al. FOXG1-Dependent Dysregulation of GABA/Glutamate Neuron Differentiation in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cell 2015, 162, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wei, P.-C.; Lim, C.K.; Gallina, I.S.; Marshall, S.; Marchetto, M.C.; et al. Increased Neural Progenitor Proliferation in a hiPSC Model of Autism Induces Replication Stress-Associated Genome Instability. Cell Stem Cell, 2020; 26, 221–233.e6. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetto, M.C.; Belinson, H.; Tian, Y.; Freitas, B.C.; Fu, C.; Vadodaria, K.; et al. Altered proliferation and networks in neural cells derived from idiopathic autistic individuals. Mol Psychiatry 2017, 22, 820–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, F.B.; Freitas, B.C.; Pignatari, G.C.; Fernandes, I.R.; Sebat, J.; Muotri, A.R.; et al. Modeling the Interplay Between Neurons and Astrocytes in Autism Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Biol Psychiatry 2018, 83, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griesi-Oliveira, K.; Acab, A.; Gupta, A.R.; Sunaga, D.Y.; Chailangkarn, T.; Nicol, X.; et al. Modeling non-syndromic autism and the impact of TRPC6 disruption in human neurons. Mol Psychiatry 2015, 20, 1350–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warre-Cornish, K.; Perfect, L.; Nagy, R.; Duarte, R.R.R.; Reid, M.J.; Raval, P.; et al. Interferon-γ signaling in human iPSC-derived neurons recapitulates neurodevelopmental disorder phenotypes. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eaay9506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hesen, R.; Mossink, B.; Nadif Kasri, N.; Schubert, D. Generation of glutamatergic/GABAergic neuronal co-cultures derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for characterizing E/I balance in vitro. STAR Protoc 2023, 4, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesi-Oliveira, K.; Fogo, M.S.; Pinto, B.G.G.; Alves, A.Y.; Suzuki, A.M.; Morales, A.G.; et al. Transcriptome of iPSC-derived neuronal cells reveals a module of co-expressed genes consistently associated with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1589–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Takata, A. The molecular pathology of schizophrenia: an overview of existing knowledge and new directions for future research. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1868–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubonyte, U.; Asenjo-Martinez, A.; Werge, T.; Lage, K.; Kirkeby, A. Current advancements of modelling schizophrenia using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2022, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkouh, I.A.; Ueland, T.; Hansson, L.; Inderhaug, E.; Hughes, T.; Steen, N.E.; et al. Decreased IL-1β-induced CCL20 response in human iPSC-astrocytes in schizophrenia: Potential attenuating effects on recruitment of regulatory T cells. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 87, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkouh, I.A.; Hughes, T.; Steen, V.M.; Glover, J.C.; Andreassen, O.A.; Djurovic, S.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals disparate expression of inflammation-related miRNAs and their gene targets in iPSC-astrocytes from people with schizophrenia. Brain Behav Immun 2021, 94, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, A.; Akkouh, I.A.; Vandenberghe, M.; Osete, J.R.; Hughes, T.; Heine, V.; et al. A human iPSC-astroglia neurodevelopmental model reveals divergent transcriptomic patterns in schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathuria, A.; Lopez-Lengowski, K.; Watmuff, B.; McPhie, D.; Cohen, B.M.; Karmacharya, R. Synaptic deficits in iPSC-derived cortical interneurons in schizophrenia are mediated by NLGN2 and rescued by N-acetylcysteine. Transl Psychiatry 2019, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G.-H.; Noh, H.; Shao, Z.; Ni, P.; Qin, Y.; Liu, D.; et al. Activated microglia cause metabolic disruptions in developmental cortical interneurons that persist in interneurons from individuals with schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci 2020, 23, 1352–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathuria, A.; Lopez-Lengowski, K.; Watmuff, B.; Karmacharya, R. Morphological and transcriptomic analyses of stem cell-derived cortical neurons reveal mechanisms underlying synaptic dysfunction in schizophrenia. Genome Med 2023, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaini, G.; Valvassori, S.S.; Diaz, A.P.; Lima, C.N.; Benevenuto, D.; Fries, G.R.; et al. Neurobiology of bipolar disorders: a review of genetic components, signaling pathways, biochemical changes, and neuroimaging findings. Braz J Psychiatry 2020, 42, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.S.; Spitzer, N.C. Calcium signaling in neuronal development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011, 3, a004259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, T.; Alural, B.; Tilak, M.; Wang, J.; Becke, N.; Chartley, E.; et al. Bipolar disorder-iPSC derived neural progenitor cells exhibit dysregulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry and accelerated differentiation. Mol Psychiatry 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadodaria, K.C.; Mendes, A.P.D.; Mei, A.; Racha, V.; Erikson, G.; Shokhirev, M.N.; et al. Altered Neuronal Support and Inflammatory Response in Bipolar Disorder Patient-Derived Astrocytes. Stem Cell Reports 2021, 16, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemsiri, V.; Rosenthal, S.B.; Nievergelt, C.M.; Maihofer, A.X.; Marchetto, M.C.; Santos, R.; et al. Focal adhesion is associated with lithium response in bipolar disorder: evidence from a network-based multi-omics analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osete, J.R.; Akkouh, I.A.; de Assis, D.R.; Szabo, A.; Frei, E.; Hughes, T.; et al. Lithium increases mitochondrial respiration in iPSC-derived neural precursor cells from lithium responders. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 6789–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, M.; Navidhamidi, M.; Rezaei, F.; Azizikia, A.; Mehranfard, N. Anxiety and hippocampal neuronal activity: Relationship and potential mechanisms. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2022, 22, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillon, C.; Robinson, O.J.; Cornwell, B.; Ernst, M. Modeling anxiety in healthy humans: a key intermediate bridge between basic and clinical sciences. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 1999–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.E.; Lobo, M.K. The molecular and cellular mechanisms of depression: a focus on reward circuitry. Mol Psychiatry 2019, 24, 1798–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avior, Y.; Ron, S.; Kroitorou, D.; Albeldas, C.; Lerner, V.; Corneo, B.; et al. Depression patient-derived cortical neurons reveal potential biomarkers for antidepressant response. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadodaria, K.C.; Ji, Y.; Skime, M.; Paquola, A.C.; Nelson, T.; Hall-Flavin, D.; et al. Altered serotonergic circuitry in SSRI-resistant major depressive disorder patient-derived neurons. Mol Psychiatry 2019, 24, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadodaria, K.C.; Ji, Y.; Skime, M.; Paquola, A.; Nelson, T.; Hall-Flavin, D.; et al. Serotonin-induced hyperactivity in SSRI-resistant major depressive disorder patient-derived neurons. Mol Psychiatry 2019, 24, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heard, K.J.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Becronis, C.; Fredlender, C.; Zahid, N.; Le, A.T.; et al. Chronic cortisol differentially impacts stem cell-derived astrocytes from major depressive disorder patients. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzinakos, C.; Pernia, C.D.; Morrison, F.G.; Iatrou, A.; McCullough, K.M.; Schuler, H.; et al. Single-Nucleus Transcriptome Profiling of Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex: Mechanistic Roles for Neuronal Gene Expression, Including the 17q21.31 Locus, in PTSD Stress Response. Am J Psychiatry, 2023; 180, 739–754. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, C.R.; Cordell, E.; Sobin, S.M.; Neumeister, A. Recent progress in understanding the pathophysiology of post-traumatic stress disorder: implications for targeted pharmacological treatment. CNS Drugs 2013, 27, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernia, C.; Chatzinakos, C.; Al Zoubi, O.; Ressler, K.; Daskalakis, N. Testing Glucocorticoid Mediated Differential Gene Expression in IPSC Derived Neural Cultures as a Model for PTSD. Biol Psychiatry 2021, 89, S307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seah, C.; Breen, M.S.; Rusielewicz, T.; Bader, H.N.; Xu, C.; Hunter, C.J.; et al. Modeling gene × environment interactions in PTSD using human neurons reveals diagnosis-specific glucocorticoid-induced gene expression. Nat Neurosci 2022, 25, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Noh, H.; Park, G.-H.; Shao, Z.; Guan, Y.; Park, J.M.; et al. iPSC-derived homogeneous populations of developing schizophrenia cortical interneurons have compromised mitochondrial function. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 25, 2873–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.; Meng, X.; Liu, Y.; Song, D.; Jiang, C.; Cai, J. Applications of brain organoids in neurodevelopment and neurological diseases. J Biomed Sci 2021, 28, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.Y.; Song, H.; Ming, G.-L. Modeling neurological disorders using brain organoids. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2021, 111, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urenda, J.-P.; Del Dosso, A.; Birtele, M.; Quadrato, G. Present and Future Modeling of Human Psychiatric Connectopathies With Brain Organoids. Biol Psychiatry 2023, 93, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tsai, J.-W.; LaMonica, B.; Kriegstein, A.R. A new subtype of progenitor cell in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Nat Neurosci 2011, 14, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, B.; Velasco, S.; Kedaigle, A.J.; Pigoni, M.; Quadrato, G.; Deo, A.; et al. Human brain organoids reveal accelerated development of cortical neuron classes as a shared feature of autism risk genes. bioRxiv. 2020, 2020.11.10.376509.

- Rabeling, A.; Goolam, M. Cerebral organoids as an in vitro model to study autism spectrum disorders. Gene Ther 2023, 30, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, B.; Velasco, S.; Kedaigle, A.J.; Pigoni, M.; Quadrato, G.; Deo, A.J.; et al. Autism genes converge on asynchronous development of shared neuron classes. Nature 2022, 602, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadrato, G.; Birtele, M. Using 3D Human Brain Organoids to Perform Longitudinal Modeling and Functional Characterization of a Top Risk Gene for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2023, 93, S56–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, M.; Fex Svenningsen, Å.; Thorsen, M.; Michel, T.M. Psychiatry in a Dish: Stem Cells and Brain Organoids Modeling Autism Spectrum Disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2018, 83, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jourdon, A.; Wu, F.; Mariani, J.; Capauto, D.; Norton, S.; Tomasini, L.; et al. Author Correction: Modeling idiopathic autism in forebrain organoids reveals an imbalance of excitatory cortical neuron subtypes during early neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci 2023, 26, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilieva, M.; Aldana, B.I.; Vinten, K.T.; Hohmann, S.; Woofenden, T.W.; Lukjanska, R.; et al. Proteomic phenotype of cerebral organoids derived from autism spectrum disorder patients reveal disrupted energy metabolism, cellular components, and biological processes. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 3749–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notaras, M.; Lodhi, A.; Dündar, F.; Collier, P.; Sayles, N.M.; Tilgner, H.; et al. Schizophrenia is defined by cell-specific neuropathology and multiple neurodevelopmental mechanisms in patient-derived cerebral organoids. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1416–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachowiak, E.K.; Benson, C.A.; Narla, S.T.; Dimitri, A.; Chuye, L.E.B.; Dhiman, S.; et al. Cerebral organoids reveal early cortical maldevelopment in schizophrenia-computational anatomy and genomics, role of FGFR1. Transl Psychiatry 2017, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathuria, A.; Lopez-Lengowski, K.; Jagtap, S.S.; McPhie, D.; Perlis, R.H.; Cohen, B.M.; et al. Transcriptomic landscape and functional characterization of induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cerebral organoids in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, A.; Lopez-Lengowski, K.; McPhie, D.; Cohen, B.M.; Karmacharya, R. Disease-specific differences in gene expression, mitochondrial function and mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum interactions in iPSC-derived cerebral organoids and cortical neurons in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Discov Ment Health 2023, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrato, G.; Brown, J.; Arlotta, P. The promises and challenges of human brain organoids as models of neuropsychiatric disease. Nat Med 2016, 22, 1220–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, R. Advances in the knowledge and therapeutics of schizophrenia, major depression disorder, and bipolar disorder from human brain organoid research. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1178494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osete, J.R.; Akkouh, I.A.; Ievglevskyi, O.; Vandenberghe, M.; de Assis, D.R.; Ueland, T.; et al. Transcriptional and functional effects of lithium in bipolar disorder iPSC-derived cortical spheroids. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3033–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteley, J.T.; Fernandes, S.; Sharma, A.; Mendes, A.P.D.; Racha, V.; Benassi, S.K.; et al. Reaching into the toolbox: Stem cell models to study neuropsychiatric disorders. Stem Cell Reports 2022, 17, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, A.; Lopez-Lengowski, K.; Vater, M.; McPhie, D.; Cohen, B.M.; Karmacharya, R. Transcriptome analysis and functional characterization of cerebral organoids in bipolar disorder. Genome Med 2020, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osete, J.R.; Akkouh, I.A.; Ievglevskyi, O.; Vandenberghe, M.; de Assis, D.R.; Ueland, T.; et al. Transcriptional and functional effects of lithium in bipolar disorder iPSC-derived cortical spheroids. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3033–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdon, A.; Wu, F.; Mariani, J.; Capauto, D.; Norton, S.; Tomasini, L.; et al. Author Correction: Modeling idiopathic autism in forebrain organoids reveals an imbalance of excitatory cortical neuron subtypes during early neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci 2023, 26, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Tang, B.; Romero, J.C.; Yang, Y.; Elsayed, S.K.; Pahapale, G.; et al. Shell microelectrode arrays (MEAs) for brain organoids. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabq5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salick, M.R.; Lubeck, E.; Riesselman, A.; Kaykas, A. The future of cerebral organoids in drug discovery. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2021, 111, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Ullah, H.M.A.; Parker, E.; Gorsi, B.; Libowitz, M.; Maguire, C.; et al. Neurite outgrowth deficits caused by rare PLXNB1 mutation in pediatric bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 2525–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Kim, J.; Park, I.-H.; Blumberg, H.; Jonas, E.A. A novel mitochondrial target as a therapeutic approach to bipolar disorder. Biophys J 2024, 123, 165a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Li, Y.; Hu, R.; Gong, M.; Chai, M.; Ma, X.; et al. Modeling disrupted synapse formation in wolfram syndrome using hESCs-derived neural cells and cerebral organoids identifies Riluzole as a therapeutic molecule. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1557–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.I.; Song, H.; Ming, G.-L. Applications of Human Brain Organoids to Clinical Problems. Dev Dyn 2019, 248, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Cong, L.; Cong, X. Patient-Derived Organoids in Precision Medicine: Drug Screening, Organoid-on-a-Chip and Living Organoid Biobank. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 762184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, S.; Sharan, S.K. Translating Embryogenesis to Generate Organoids: Novel Approaches to Personalized Medicine. iScience 2020, 23, 101485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhibber, T.; Bagchi, S.; Lahooti, B.; Verma, A.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Paul, M.K.; et al. CNS organoids: an innovative tool for neurological disease modeling and drug neurotoxicity screening. Drug Discov Today 2020, 25, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, P.; Wang, Y.; Xu, M.; Han, X.; Liu, Y. The Application of Brain Organoids in Assessing Neural Toxicity. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 799397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z. Vincristine Impairs Microtubules and Causes Neurotoxicity in Cerebral Organoids. Neuroscience 2019, 404, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Dai, Y.; Fang, X.; Chen, K.; et al. Acrylamide exposure represses neuronal differentiation, induces cell apoptosis and promotes tau hyperphosphorylation in hESC-derived 3D cerebral organoids. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 144, 111643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Pan, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, F.; Wang, R.; Zhang, T.; et al. Maternal Benzophenone Exposure Impairs Hippocampus Development and Cognitive Function in Mouse Offspring. Adv Sci 2021, 8, e2102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzua, T.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, C.; Logan, S.; Allison, R.L.; Wells, C.; et al. Modeling alcohol-induced neurotoxicity using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived three-dimensional cerebral organoids. Transl Psychiatry 2020, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, E.F.; Grimm, S.L.; Stertz, L.; Gorski, D.; Movva, S.V.; Najera, K.; et al. A human stem cell-derived neuronal model of morphine exposure reflects brain dysregulation in opioid use disorder: Transcriptomic and epigenetic characterization of postmortem-derived iPSC neurons. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1070556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Guo, X.; Lu, S.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Z.; Lai, L.; et al. Long-term exposure to cadmium disrupts neurodevelopment in mature cerebral organoids. Sci Total Environ 2024, 912, 168923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmentier, T.; LaMarre, J.; Lalonde, J. Evaluation of Neurotoxicity With Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cerebral Organoids. Curr Protoc 2023, 3, e744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirnova, L.; Caffo, B.S.; Gracias, D.H.; Huang, Q.; Morales Pantoja, I.E.; Tang, B.; et al. Organoid intelligence (OI): the new frontier in biocomputing and intelligence-in-a-dish. Frontiers in Science 2023, 1, 1017235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Ao, Z.; Tian, C.; Wu, Z.; Liu, H.; Tchieu, J.; et al. Brain organoid computing for artificial intelligence. bioRxiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Saglam-Metiner, P.; Gulce-Iz, S.; Biray-Avci, C. Bioengineering-inspired three-dimensional culture systems: Organoids to create tumor microenvironment. Gene 2019, 686, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglam-Metiner, P.; Yildirim, E.; Dincer, C.; Basak, O.; Yesil-Celiktas, O. Humanized brain organoids-on-chip integrated with sensors for screening neuronal activity and neurotoxicity. Mikrochim Acta 2024, 191, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambalo, M.; Lodato, S. Brain organoids: Human 3D models to investigate neuronal circuits assembly, function and dysfunction. Brain Res 2020, 2020, 1746, 147028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitz, S.; Bolognin, S.; Brandauer, K.; Füßl, J.; Schuller, P.; Schobesberger, S.; et al. Development of a multi-sensor integrated midbrain organoid-on-a-chip platform for studying Parkinson’s disease. bioRxiv. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Miccoli, B.; Braeken, D.; Li, Y.C.E. Brain-on-a-chip devices for drug screening and disease modeling applications. Curr Pharm Des 2018, 24, 5419–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Os, J.; Rutten, B.P.; Poulton, R. Gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia: review of epidemiological findings and future directions. Schizophr Bull 2008, 34, 1066–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahbeh, M.H.; Avramopoulos, D. Gene-Environment Interactions in Schizophrenia: A Literature Review. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockhart, S.; Sawa, A.; Niwa, M. Developmental trajectories of brain maturation and behavior: Relevance to major mental illnesses. J Pharmacol Sci 2018, 137, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagas L da, S.; Sandre, P.C.; Ribeiro E Ribeiro, N.C.A.; Marcondes, H.; Oliveira Silva, P.; Savino, W.; et al. Environmental Signals on Microglial Function during Brain Development, Neuroplasticity, and Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, C.; Tian, H.; Song, X.; Jiang, D.; Chen, G.; Cai, Z.; et al. Microglia and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: translating scientific progress into novel therapeutic interventions. Schizophrenia (Heidelb) 2023, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, L.N.; An, K.; Carloni, E.; Li, F.; Vincent, E.; Trippaers, C.; et al. Prenatal immune stress blunts microglia reactivity, impairing neurocircuitry. Nature 2022, 610, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Summary of Cellular Phenotypes of Different Disorders in 2D Models.

Table 1.

Summary of Cellular Phenotypes of Different Disorders in 2D Models.

| Disease |

Cell Type |

Region |

Observations/Findings |

References |

| MDD |

Cortical

Neurons |

Cortex |

Mushroom spine dendrites have greatly elevated length in cell lines that respond to bupropion treatment. Non-responsive lines have a non-significant reduction in dendrite length. In MDD cell lines derived from patients that did not respond to SSRIs, lowered expression of protocadherin-α genes resulted in altered neurite growth. Knockdown of protocadherin-α resulted in improved neurite length. |

[33,35] |

| MDD |

Astrocytes |

Cortex |

Differential expression of genes related to GPCR ligand binding, synaptic signaling, and ion homeostasis. |

[36] |

| BD |

NPCs |

Cortex |