Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

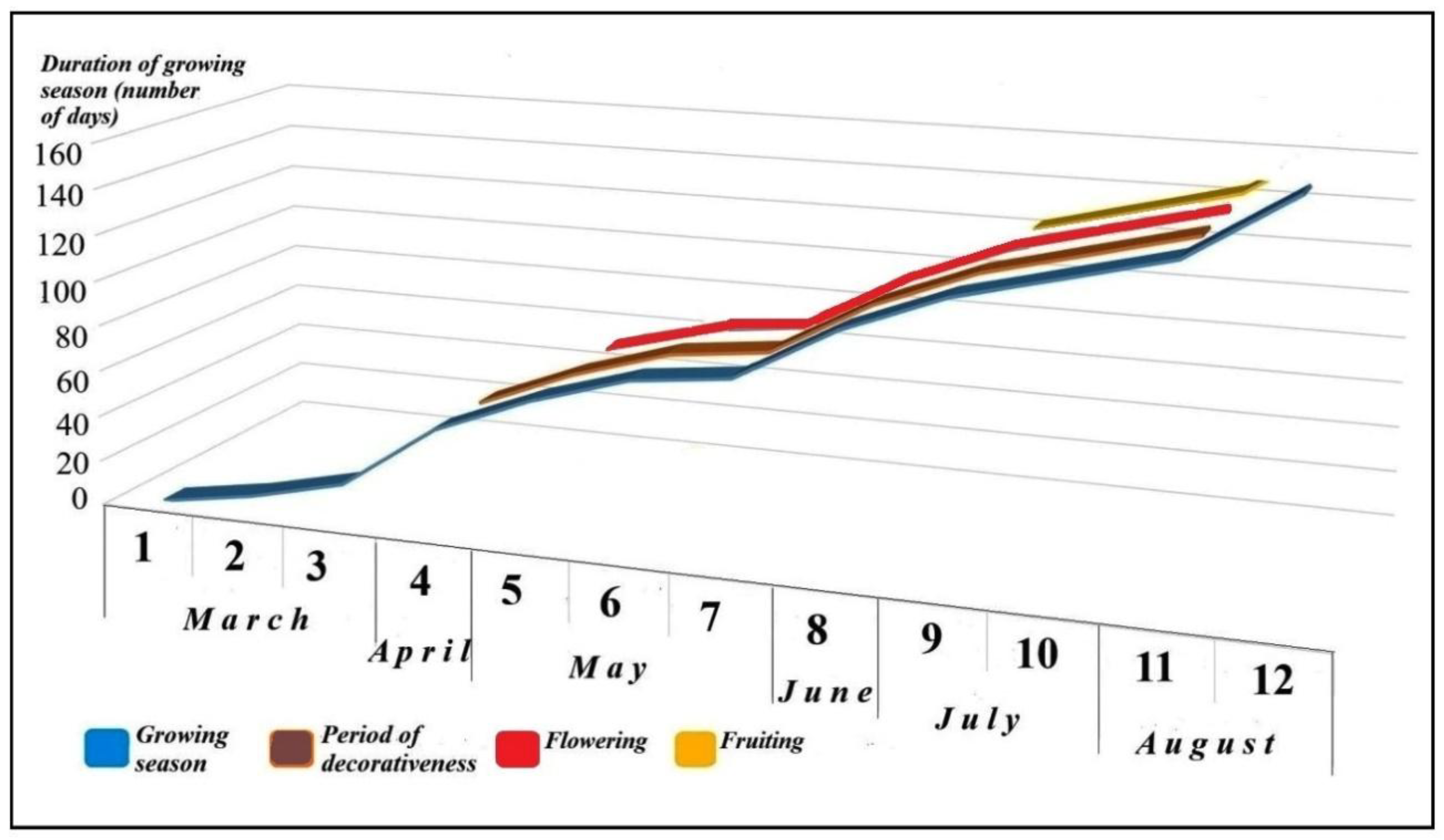

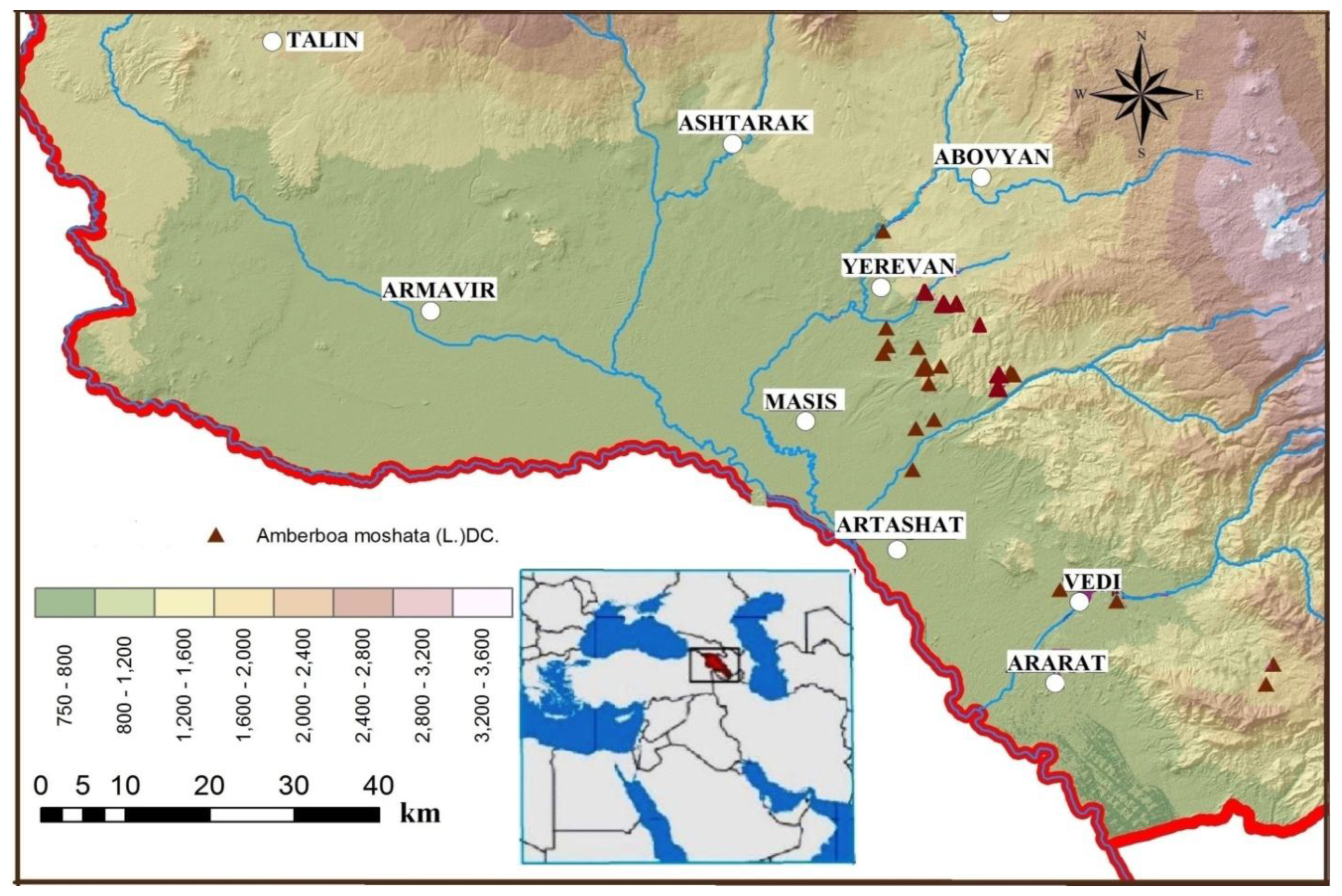

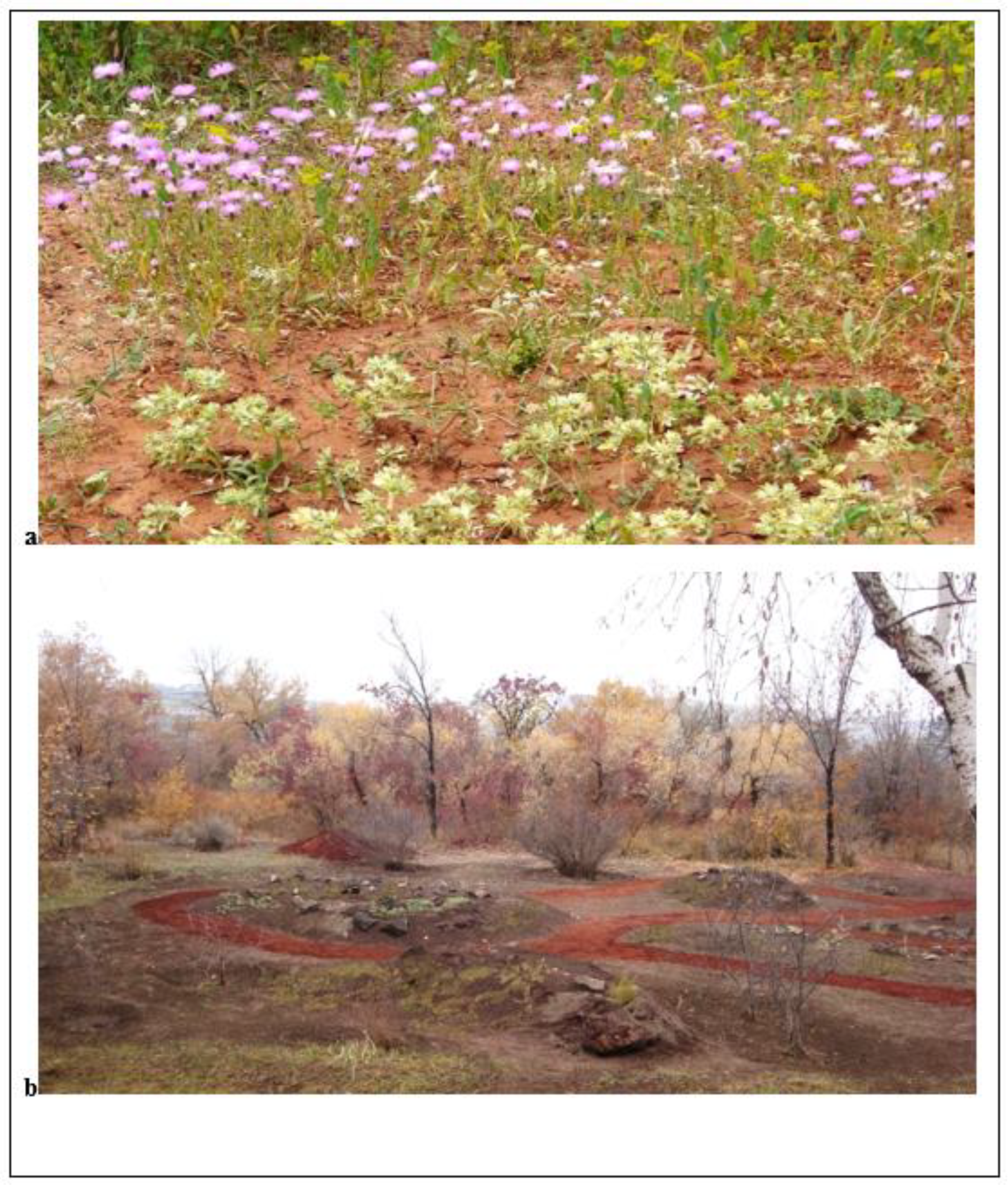

The article presents data on morpho-phenological, karyological, palynological, some eco-physiological and ornamental features of the Armenian flora endangered species Amberboa moschata (L.) DC. (Asteraceae). According to conducted exploration, the plants cultivated in the Yerevan Botanical Garden have satisfactory adaptive capacity, a complete development cycle, the ability to form mature seeds and self-renewal by seeds, and higher parameters of total moisture, transpiration intensity and photosynthesis compared to natural ones. The diploid cytotype has been found for the species to be 2n=32, the karyotype is asymmetric, with chromosomes, 0.77–1.91µm in size. The average pollen fertility of A. moschata is high, 96.7–96.9% in both natural and cultivated samples. A scale of ornamental properties of A. moschata has been compiled, including 15 characteristics of the plant. The total duration of plant ornamental period under cultivation is about 98 days, the maximum ornamental effect is observed during the flowering period of 68–70 days. The studied species is recommended for creating living collections in botanical gardens and utilization in ornamental gardening and landscaping as measures for its ex situ conservation. The article is illustrated with a map, original photographs and tables.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Site and Cultivation Techniques

2.2. Morpho-Phenological and Ornamental Traits Assessment

2.3. Chromosome Analysis

2.4. Pollen Fertility Analysis

2.5. Eco-Physiological Features Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morpho-Phenological and Ornamental Characteristics

| Traits of decorativeness | Traits value and score (points) | Trait significance coefficient | Number of points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Inflorescence color and stability | Color is bright, stable or slightly unstable (5) | 3 | 15 |

| Inflorescence shape | Large fringed basket (5) | 2 | 10 |

| Inflorescence size (diameter and height) | Diameter 5–7 cm, height from 3.5–4.5 cm (5) | 2 | 10 |

| Petal quality | Dense, retaining shape under adverse weather conditions (5) | 1 | 5 |

| Number of inflorescences on one generative shoot | Оne inflorescence (5) | 2 | 10 |

| Number of simultaneously open inflorescences on a plant | In the mass flowering phase about 70% (5) and more or about 50% (4) | 3 | 15 |

| Inflorescence density | Dense, compact (5) | 2 | 10 |

| Shoots strength | Not subject to deformation under the influence of external factors (5) | 2 | 10 |

| Shoots coloring | Bright (5) or middle bright (4) | 1 | 4 |

| Leaves color stability | Stable (5) or slightly unstable (4) | 2 | 8 |

| Durability of leaves decorativeness | Most decorative during the phases of budding and flowering (5) | 1 | 5 |

| Fruits decorativeness | Fruits slightly enhance the decorative effect (5) | 3 | 9 |

| General condition of plants during the flowering period | Presence or absence of breaks during flowering (5) | 2 | 10 |

| Plant originality | Habitus attractiveness (5) | 1 | 5 |

| Period of decorativeness | From the phase of formed vegetative habit of the plant until the end of flowering (5) | 1 | 5 |

| Sum of points | 131 | ||

3.2. Karyology

3.3. Pollen fertility of A. moschata

3.4. Eco-Physiological Characteristics

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gabrielian E.T. Amberboa (Pers.) Less. In: Konspekt flory Kavkaza [Caucasian flora Conspectus]. 2008. Vol. 3, Part 1. St. Petersburg; Moscow: KMK Scientific Press Ltd. Pp. 282–285.

- Murtazaliev R.A. A new species of the genus Amberboa (Asteraceae) from Dagestan. Turczaninowia 2024, 27, 1, 81–91 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Tamanyan, K.; Fayvush, G.; Nanagulyan, S.; Danielyan, T. (eds.). The Red Book of Plants of the Republic of Armenia. Higher Plants and Fungi. Second edition. Yerevan. 2010; 592 p.

- Heywood,V.H. (Ed.) The Botanic Gardens Conservation Strategy; IUCN Botanic Gardens Conservation Secretariat: Richmond, UK, 1989, 60 p.

- Heywood V.H. Conservation and sustainable use of wild species as sources of new ornamentals. Acta Horticulturae 2003, 598, 43–53. [CrossRef]

- Neves, K.G. Botanic Gardens in Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainability: History, Contemporary Engagements, Decolonization Challenges, and Renewed Potential. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2024, 5, 260–275. [CrossRef]

- Mounce, R.; Smith, P.; Brockington, S. Ex situ conservation of plant diversity in the world’s botanic gardens. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 795–802. [CrossRef]

- Akopian, J.A. Conservation of native plant diversity at the Yerevan Botanic Garden,Armenia. Kew Bulletin 2010, 65, 4, 663–669. [CrossRef]

- Akopian, J.; Hovakimyan, Zh.; Paravyan, Z. Bio-morphological features of somerare and endangered sandy and gypsy desert plant species of Armenia. Biol. Zhurn. of Armenia 2017, 3 (69), 201, 39–46.

- Akopian, J.A. The exhibition of Flora and Vegetation of Armenia of the Yerevan Botanical Garden NAS RA – the principles of collection formation and modeling ofphytocoenoses. Landscape architecture in botanical gardens and dendroparks. Materials of the XI international scientific conference 2019. Yerevan; 46–53.

- Akopian, J.A.; Ghukasyan, A.G.; Elbakyan, A.H.; Martirosyan, L.Yu. Indigenous flora as a source of arid ornamental horticulture in Armenia. Yerevan. Gitutiun NAS RA. 2023. 213 p.

- Gosling, P.G. Viability testing // Seed conservation. Turning science into practice. 2003, 445–481.

- Newton, R. Germination and Dormancy, Part 1 SCT RN final. 2005, 69 p.

- Beydeman, I.N. Methods of studying the phenology of plants and plant communities. Methodical instructions.1974. The science. Novosibirsk. 155 p.

- Bylov, V.N. Fundamentals of Comparative Variety Evaluation of Ornamental Plants. Introduction and selection of ornamental plants.1978. M. Pp. 7–32.

- Pausheva, Z.P. Workshop on plant cytology. 1980. M., Kolos. 304 p.

- Dospekhov, B.A. Field experiment methodology.1973. M. 336 p.

- Wolf, V. G. Statistical data processing. 1966. M. Kolos. 254 p.

- Sheremetyev, S.N. Grasses on a soil moisture gradient. Partnership of scientific publications KMK, 2005. Moscow. 271 p.

- Salnikov, A.I.; Maslov, I.L. Physiology and biochemistry of plants: workshop.2014. Perm, Publishing House of FGBOU VPO Perm State Agricultural Academy, 300 p.

- Mezhunts, B.Kh.; Navasardyan, M.A. Method for determining the content of chlorophylls a, b and carotenoids in plant leaf extracts. Patent for Invention. No. 2439 A., 2010. Yerevan.

- Shlyk, A.A. Definition of Chlorophylls and Carotenoids in Extracts of Green Leaves. In: Biochemical Methods in the Physiology of Plants. 1971. M., Nauka. Pp.154–170.

- Nikolaeva, M.G. Peculiarities of germination of seeds of plants from the subclasses Dilleniidae, Rosidae, Lamiidae and Asteridae. Bot. Zhurn. 1989, 74, 5, 651–668.

- Borisova, I.V. Types of germination of seeds of steppe and semi-desert plants. Bot. Zhurn. 1996, 81, 12, 9–22.

- Wróblewska, A.; Stawiarz, E.; Masierowska, M. Evaluation of Selected Ornamental Asteraceae as a Pollen Source for Urban Bees. Journal of Apicultural Science 2016, 60(2), 179–191. [CrossRef]

- Tonyan, T.R. The chromosome number of some species of the genus Centaurea. Biol. Journ. of Armenia 1968, 21, 8, 86–96.

- Tonyan, T.R. Correlation of some morphological features with ploidy in representatives of the subtribe Centaureinea Less. Biol. Journ. of Armenia 1972, 25, 11, 86–96.

- Tonyan, T.R. The relationship between the number of chromosomes and some morphological characters in representatives of the subtribe Centaureinea Less. Biol. Journ. of Armenia 1980, 33, 5, 522–554.

- Avetisian, E.M. & Tonyan, T.R. Palynomorphology and number of chromosomes of some of the species of the subtribe Centaureinae Less. In: Academy of Sciences of Armenia, ed. Palynology. 1975.Yerevan; pp. 45–49.

- Garcia-Jacas, N., Susanna, A. Vilatersana, R.& Guara M. New chromosome counts in the subtribe Centaureinea (Asteraceae, Cardueae) from west Asia, II. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1998. 128, 403–412. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.C. & Gill, B.S. Compositae. 215 p. In: Löve A. (ed.). Chromosome number reports LXXI. Taxon 1981, 30, 507–517.

- Gupta, R.C. & Gill, B.S. Cytopalynology of North and Central Indian Compositae. J. Cytol Genet. 1989, 24, 96–105.

- Moore, D.M. Index to plant chromosome numbers 1967–1971. Regnum Vegetable. 1973; 90 p.

- Kharina, T.G., Pulkina, S.V. Features of the biology of flowering Serratula coronata L. In: Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Dedicated to the 140th Anniversary of the Siberian Botanical Garden of Tomsk State University: “Botanical gardens as centers for the study and conservation of phytodiversity”; 2020, Tomsk, September 28–30, 203–205. [CrossRef]

- Elbakyan, A.H. Pollen fertility in some interspecific hybrids of tomato. Sixth International Solanaceae Conference. Madison, USA, 23–27 July 2006, Abstract ID 218, poster – 119.

- Elbakyan, A.H. Pollen fertility in some species and interspecific hybrids of tomato. Fl., Veget. and Plant Res. of Armenia 2007, 16, 94–95. Yerevan. [CrossRef]

- Yandovka, L.F.; Shamrov, I.I. Pollen fertility in Cerasus vulgaris and C. tomentosa (Rosaceae). Bot. Zhurn. 2006, 91, 2, 206–218.

- Kruglova, N.N. Assessment of the pollen grains quality in flowering plants (overview). Bull. of the State Nikita Botan. Gard. 2020, 135, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Rigamoto, R.R. and Tyagi, A.P. Pollen Fertility Status in Coastal Plant Species of Rotuma Island. The South Pacific Journal of Natural Science 2002, 20(1), 30–33.

- Qureshi, S.J.; Khan, M.A.; Arshad, M.; Rashid, A.; Ahmad, M. Pollen Fertility (Viability) Status in Asteraceae Species of Pakistan. Trakia Journal of Sciences 2009, 7,1, 12–16.

- Belyaeva, T.N.; Leshchuk, R.I. The Pollen Fertility and the Features of Seed Germination of Some Perennial Decorative and Medicinal Plants from Family Asteraceae Dumort. in culture in the Siberian Botanical Garden. Belgorod State University Scientific Bull. Nature Sciences 2011, 187 [IV], 3 (98), 14/1, 188–192.

- Gibson, A.C. Photosynthetic Organs of Desert Plants. BioScience 1998, 48, 11, 911–920. [CrossRef]

| Specimen number | Locality |

| ERE 130754 | Abovyan distr., Zovashen, vicinity of the Azat reservoir, hammada. 14.06.1985, E.Gabrielian |

| ERE 139664 | Abovyan distr., between villages Djrvej and Shorbulakh, on dry clay slopes, 1100-1500 m a.s.l. 27.06.1985, E.Gabrielian |

| ERE 130754 | Abovyan distr., Zovashen, vicinity of the Azat reservoir, hammada. 14.06.1985, E.Gabrielian |

| ERE 139664 | Abovyan distr., between villages Djrvej and Shorbulakh, on dry clay slopes, 1100-1500 m a.s.l. 27.06.1985, E.Gabrielian |

| ERE 145154, 145156 | Nubarashen, on clay slopes. 02.07.1997, E. Gabrielian |

| ERE 151800 | Near Nubarashen, on tertiary red clays. 24.05.2000, E. Gabrielian |

| ERE 153193 | Kotayk province, Abovyan distr., between villages Shorbulakh and Vokhchaberd, 3 km SSW of Vokhchaberd, Erebuni reserve, mountain steppe, 1350 m a.s.l., 01.07.2003. M. Barkworth, F. Smith, E. Gabrielian, A. Nersesyan, M. Oganesyan |

| ERE 202314 | Yerevan, southern border of city at Sovetashen, 1040 m, 40o07'22'' N/ 44o32'36''E 11.07.2003, M. Oganesian, H. Ter-Voskanyan, E. Vitek |

| ERE 161644 | Sovetashen, 1190 m a.s.l. 40º06'100'' N /44º33'25'' E. 26.05.2006. K. Tamanyan, G. Fayvush |

| ERE 190335 | Kotayk marz, vicinity of Vokhchaberd village, on the territory of the Erebuni Nature Reserve, on clays. 05.06.2008. J. Akopian |

| ERE 182109 | Vedy region, near v. Urtcadzor, on dry clay slopes,1100 m. 24.05.2011, E. Gabrielian |

| ERE 202313 | Ararat province, slope between river and road Vedi to Lusashogh, 3.5 km SE of Urtsadzor, 1165 m, 39o53'50''N/ 40º50'58''E 17.05.2017, E.Vitek, M.Oganesian, M.Sargsyan, A.Khachatryan |

| ERE 202334 | Ararat Marz 5.6 km from Lanjasar, near Azat reservoir, 40º05'13'' N/44º38'06'' E, 1110 m to 40º05'17'' N 44º38'05'' E, 1130 m, 2018.06.04, E.Vitek, P.Escobar-Garcia, G.Fayvush |

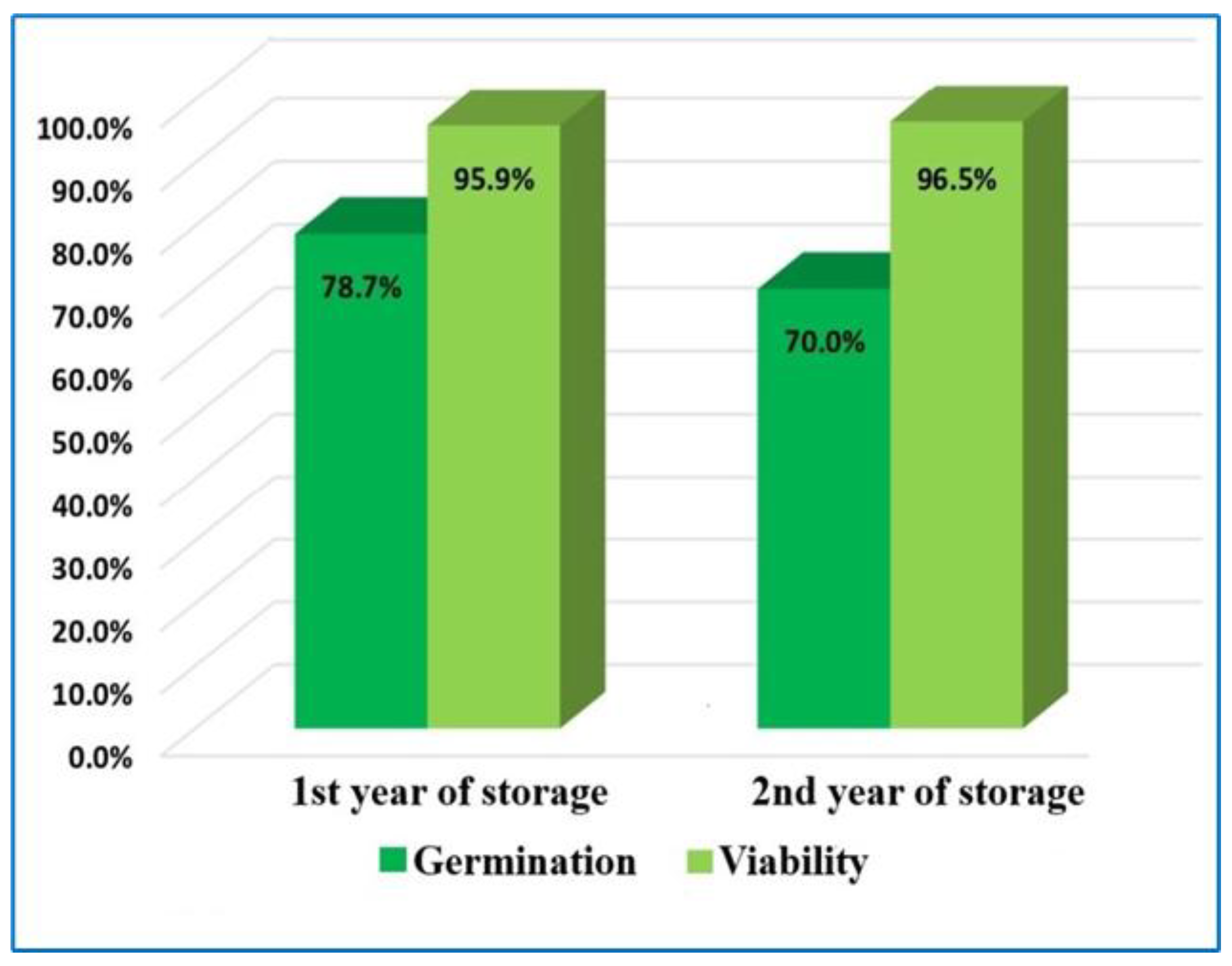

| Experiment repetition number | Seed germination (%) | Seed viability (%) | ||

| Seeds of the 1st year of storage | Seeds of the 2nd year of storage | Seeds of the 1st year of storage | Seeds of the 2nd year of storage | |

| I | 82 | 70.5 | 96 | 94.4 |

| II | 73.3 | 67.6 | 98 | 100 |

| III | 81.3 | 71.8 | 93,8 | 94.8 |

| Average | 78.7 ± 3.22 | 70 ± 1.3 | 95.9±1.2 | 96.5±2.1 |

| Amberboamoschata | Pollen grain size, μm | Average pollen fertility percentage, % |

| Yerevan Botanical Garden | ||

| Cultivated specimens | 61.4–63.2 | 96.7±0.9 |

| Herbarium samples (ERE) collected from natural habitats | ||

| N 130754 | 62.4–67.1 | 96.0±2.2 |

| N 139664 | 60.2–62.8 | 97.8±0.7 |

| N 145154 | 59.8–61.6 | 98.2±1.1 |

| N 151800 | 59.4–62.4 | 97.4±0.9 |

| N 153193 | 62.4–63.6 | 97.6±1.3 |

| N 202314 | 57.4–62.6 | 96.8±1.4 |

| N 161644 | 58.2–62.4 | 99.4±0.5 |

| N 182109 | 58.8–63.0 | 96.6±1.3 |

| N 202313 | 60.2–62.8 | 95.8±1.6 |

| N 202334 | 60.3–64.5 | 98.1±1.2 |

| Plant species and habitat | Total water content,% | Water deficit, % | Intensity of transpiration, mg CO2 dm2/ hour | Photosynthetic productivity, mg/g wet weight, hour |

| Amberboa moschata cultivated in the Yerevan Botanical Garden | 50.02±0.91c | 35.83±0.82d | 135.62±0.92b | 2.13±0.902cd |

| Amberboa moschata in the natural habitat of the “Erebuni” State Reserve | 48.01±1.08d | 37.81±0.81b | 130.43±0.91b | 2.03±0.821d |

| Optical density of chlorophyll “a”, λ 663 | 0.932±0.015d |

| Optical density of chlorophyll “b”, λ 645 | 0.847±0.001c |

| Optical density of carotenoids, λ 440.5 | 1.261±0.014d |

| Chlorophyll “a” content, per wet leaf (mg/g) | 22.308±0.114c |

| Chlorophyll “b” content, per wet leaf (mg/g) | 26.612±0.112c |

| Chlorophyll “a”+”b” | 48.920±0.102cd |

| Chlorophyll “a”/“b” | 0.8±0.022c |

| Carotenoids content, per wet leaf (mg/g) | 6.85±0.271d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).