1. Introduction

Injuries to the genital area in women are common due to various factors, including trauma during sexual activity and menopause [

1]. According to Segars M. et al. [

2], most local trauma to the lower genital tract results from consensual sexual intercourse, particularly tearing of the posterior fornix. These injuries typically occur in women aged 16 to 25 and those over 45. Other causes of genital trauma include childbirth, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), recurrent urinary tract infections, foreign objects, tampon use, traumatic accidents, and sexual assault [

3,

4,

5]. Approaches to addressing STI’s vary among research groups. For instance, Notario-Perez’s group focuses on prevention [

6], while Mishra’s group targets symptom management [

7]. Treatment procedures depend on the type of infection, with different drugs loaded into carrier systems for conditions such as Candidiasis [

8], HIV [

9], HPV [

10], or microbial infections [

11]. Many of these conditions and traumas result in lacerations to the vaginal tissue, necessitating active molecules that can promote cell growth, particularly in epithelial cells, such as retinol [

12]. Retinol (Vitamin A) is present in the bloodstream through the ingestion of carotenoids [

13] and is stored for use when needed. It plays a crucial role in the expression of several proteins, overall lung health, vision, and fetal development [

14].

Due to its anti-aging effects when applied to the skin and its importance as a nutrient for vision and lung health, many research groups and companies are exploring retinol for epithelial tissue regeneration [

15]. Various conditions, such as low intake, inflammation, prenatal periods, or infections, can lead to low levels of retinol in the blood, resulting in imbalances in epithelial tissue and an increased risk of infections [

16]. It has been demonstrated that using retinol for cervicovaginal treatment can reverse metaplasia and promote cell proliferation [

17].

The earliest recorded use of vaginal administration for therapeutic purposes dates back to ancient Egyptian papyrus, where remedies were applied to address women’s health issues and aid recovery from pelvic trauma following accidents or childbirth [

18]. Since then, many treatments have been administered via this route due to its high blood supply, which promotes both local and systemic responses. This method offers numerous benefits, such as allowing lower doses, less frequent administration, and steady drug levels, while also avoiding the first-pass effect, which means it does not impact the gastrointestinal system [

19].

Various forms of intravaginal drug delivery have been introduced, including ovules, sponges, tablets, creams, gels, vaginal rings, and films [

20]. Recently, an additional feature has been incorporated into these systems: mucoadhesiveness. This characteristic helps reduce leaks and the loss of active molecules by adhering to the mucosal surface [

21]. Consequently, many research groups are now developing mucoadhesive systems for intravaginal delivery to treat or prevent various conditions, especially STIs [

22]. For a mucoadhesive system to effectively deliver and release active molecules, it must be made from biocompatible, biodegradable, and flexible materials, which is why polymers are often used [

23]. Polymers are versatile macromolecules commonly found in nature, interacting with DNA, polypeptides, and cellulose, and they have excellent compatibility with living systems [

24]. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) is one of the most widely used polymers for drug delivery. Its hydrophilic properties allow it to swell upon contact with human fluids, leading to controlled release as the matrix degrades [

25,

26]. HPMC is often used in mucoadhesive polymeric films for controlled drug release in mucosal areas, such as the vagina [

22]. HPMC is typically combined with an enhancer like Polyethylene Glycol (PEG 400), a low molecular weight, low-toxicity, highly hydrophilic molecule. PEG enhances the absorption of active molecules [

27].

The goal of this investigation was to develop a mucoadhesive polymeric film made with HPMC and PEG 400, loaded with retinol for intravaginal administration.

2. Results

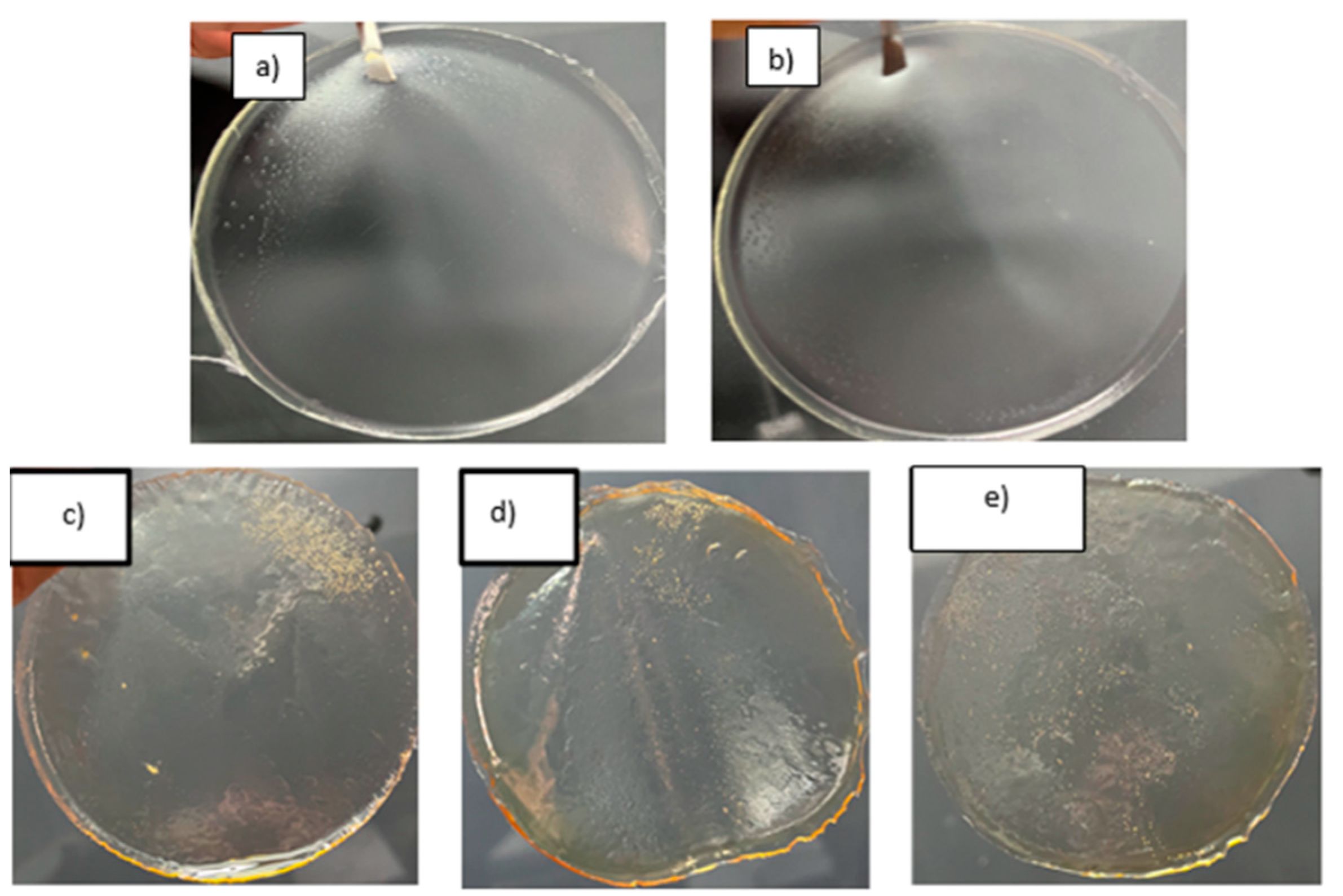

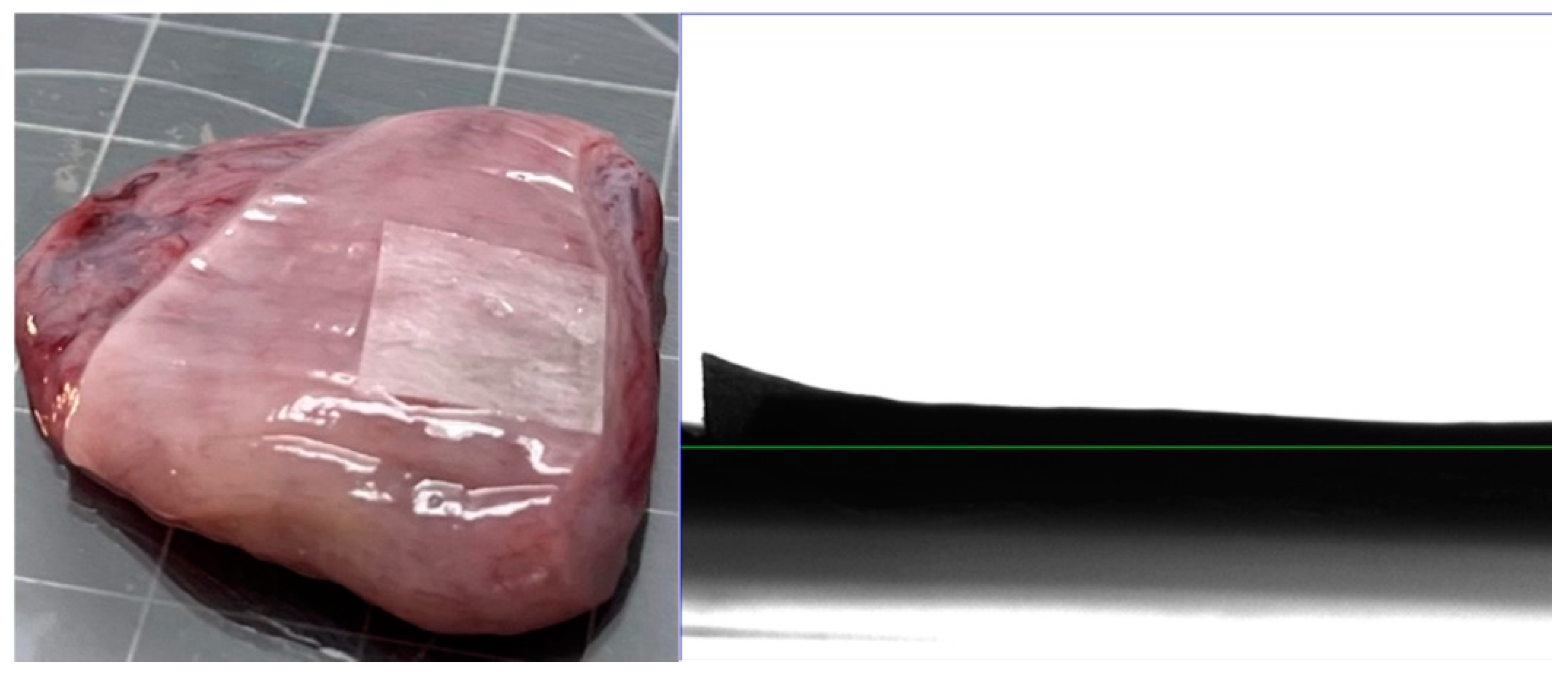

First, polymeric films were obtained, exhibiting various colors and textures depending on the concentration of HPMC and retinol. Increasing the amount of HPMC resulted in the formation of larger bubbles when retinol was added (

Figure 1). The films also displayed increased humidity and yellowness, with larger bubbles or pores visible. This can enhance the adhesion of the film to the vaginal tissue.

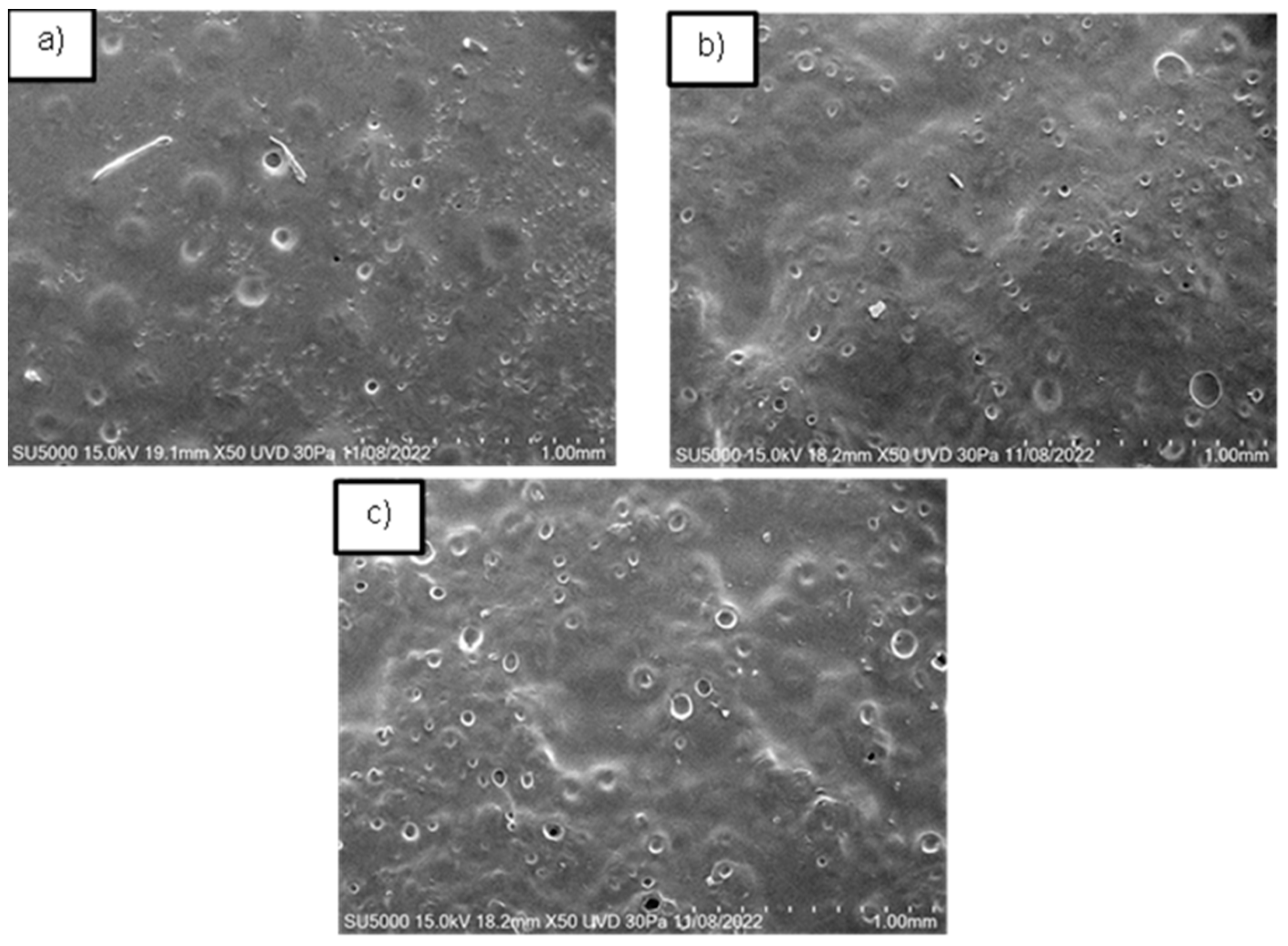

The films demonstrated a porous topography with varying dimensions, from micro to macro pores, both closed and open, as observed using the FESEM technique. Our findings align with Sampath et al., indicating that the variety of pores can influence the material’s success in application [

28]. In contrast to previous reports [

22], the pores in our films were smaller than 100 µm. The pore size and shape varied with the HPMC concentration (

Figure 2). For films with 0.2 g of HPMC, pore sizes ranged from 5 µm to 11 µm, with most pores being closed. In films with 0.3 g of HPMC, most pores were open, ranging from 1 to 42 µm. Thus, it is possible to obtain films with both micro and macro pores. Additionally, the second film had a higher porosity percentage (over 80%) compared to the first film.

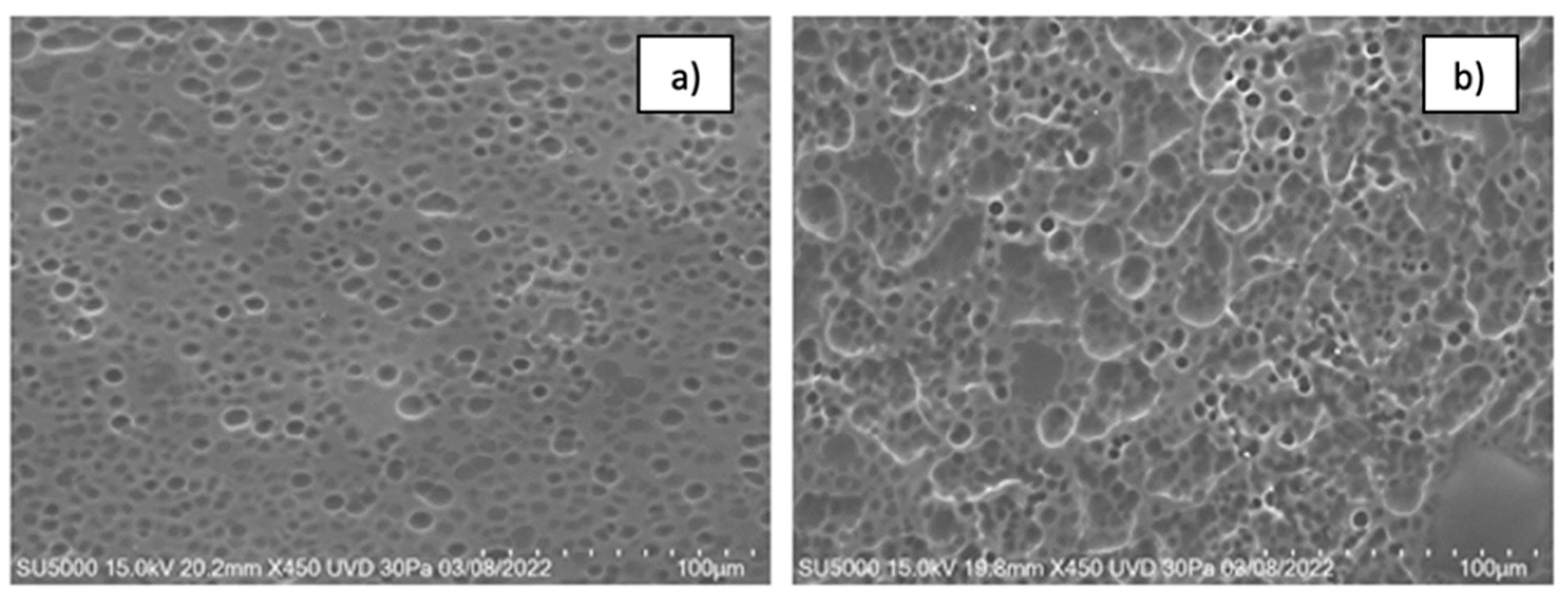

When retinol was added to the films, some pores were filled with retinol (

Figure 4). Increasing the concentration of retinol resulted in larger pores and topographical changes, making the system lumpier. This change in topography could improve the system’s adhesion to the vaginal epithelium. In

Figure 4a, the pores had an average diameter of 24 µm, while the lumps ranged from 100 to 200 µm. For 2.5 mL of retinol, the pores were approximately 46 µm, and the lumps were 445 µm. For 3 mL of retinol, the pores measured 70 µm, and the lumps ranged from 1,500 to 3,000 µm. This data indicates that increasing the concentration of retinol alters the pore size and topography, making the system lumpier.

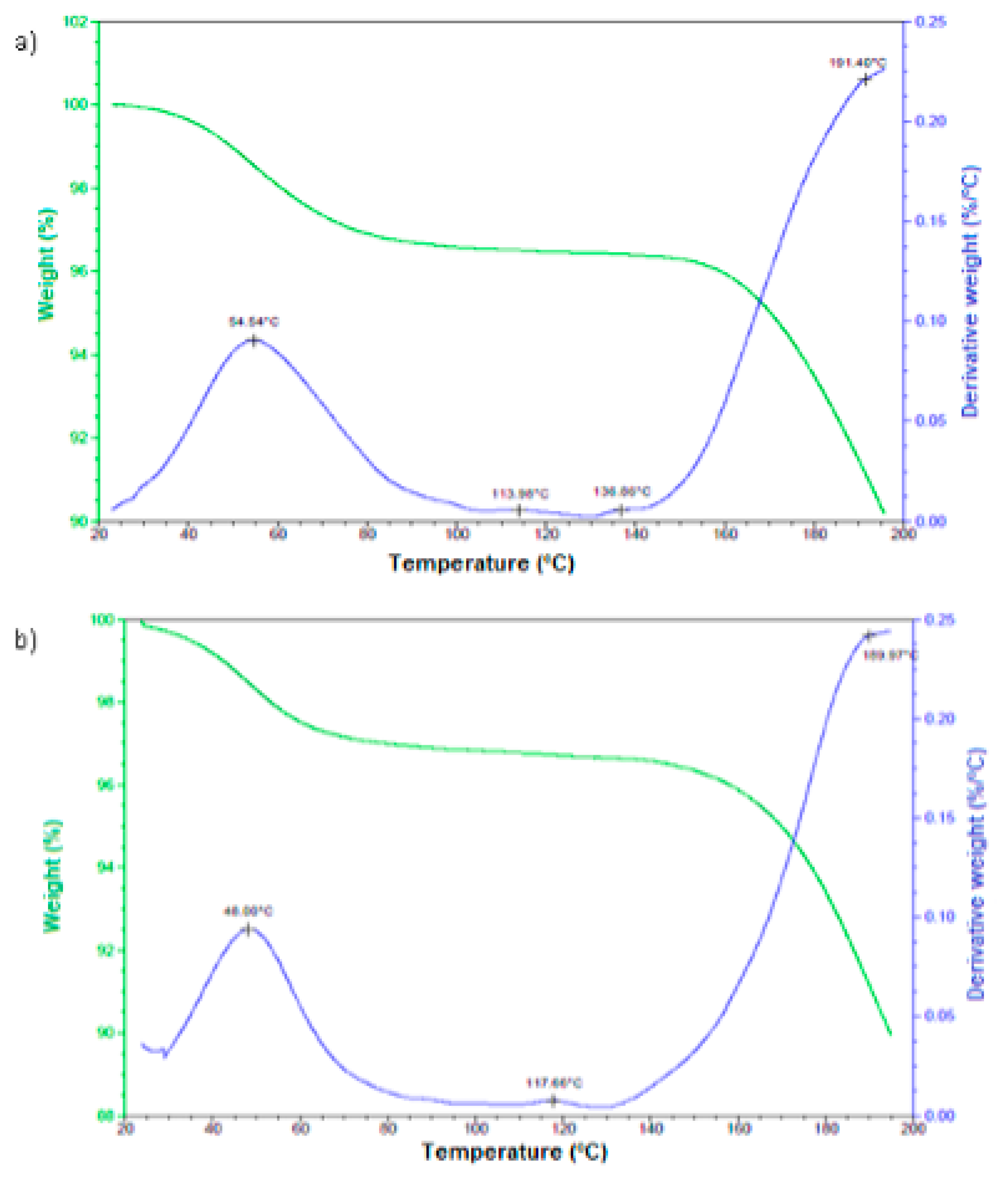

The analysis of the films’ behavior with and without retinol under controlled temperature increase is shown in

Figure 4. Both signals are quite similar, starting with a weight loss between 40 and 60°C, which is related to the evaporation of unevaporated dichloromethane during the film’s drying process. The next transition, from 80 to 140°C, is likely due to dehydration. Although water was not part of the synthesis, the film’s high hydrophilicity could have led to water absorption. Finally, the weight loss at 150°C is attributed to the evaporation of methanol, which is part of the synthesis process.

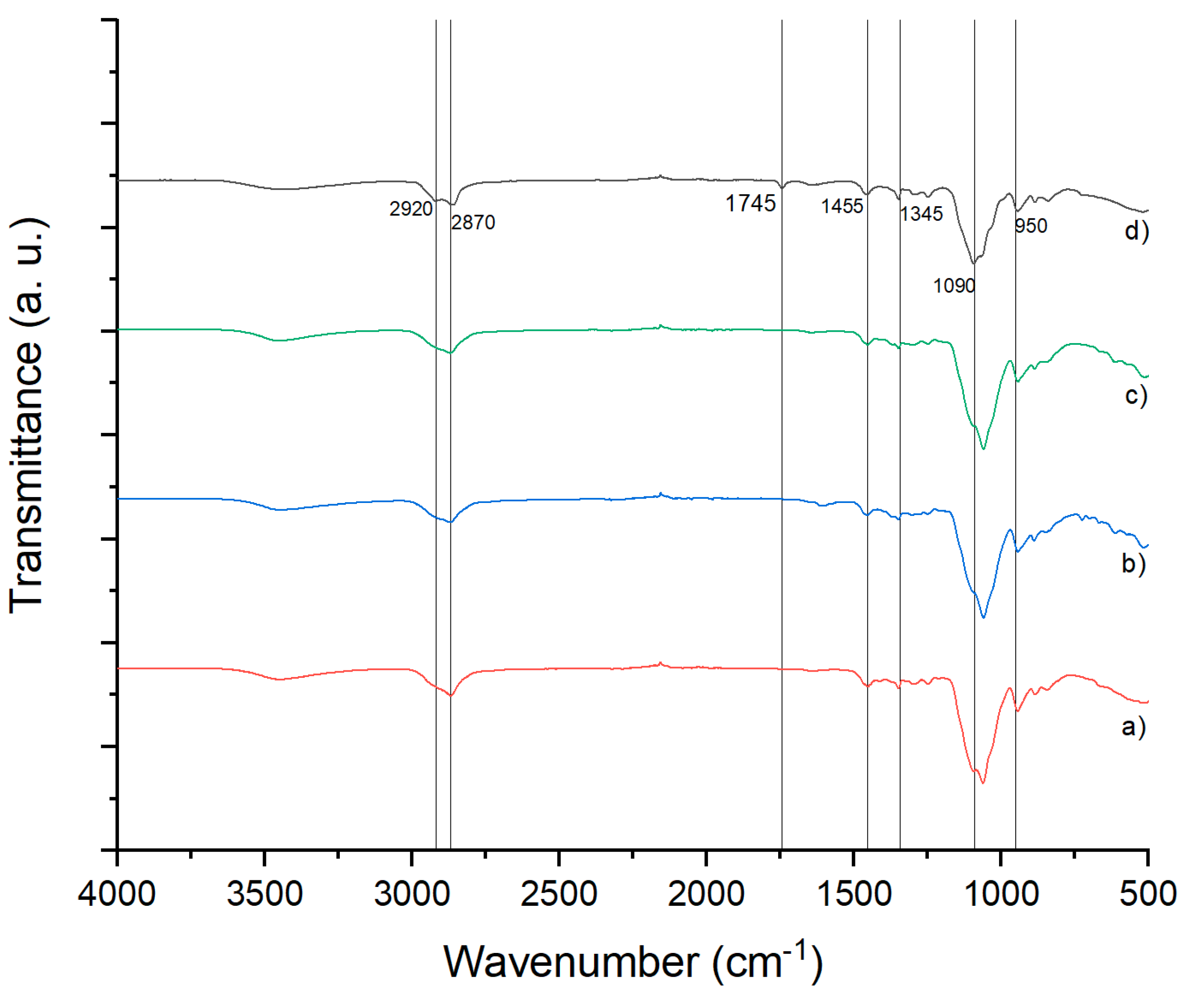

FTIR spectra of the control polymeric films, those loaded with ketorolac, and those with or without retinol are displayed in

Figure 5. The H-C-H group stretching at 2920 cm⁻¹ is present in all molecules, with asymmetrical bending at 1455 cm⁻¹. The C-H group stretching is from the original film, 1745 cm⁻¹ indicates the C=O from the retinol molecule, 1375 cm⁻¹ shows the C-N group from ketorolac, and the C-O-C group displays stretching and bending movements from the original film. The C-O-C stretching is present at 1050 cm⁻¹ in samples a, b, and c, but shifts to 1090 cm⁻¹ in sample d, which can be attributed to intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonds.

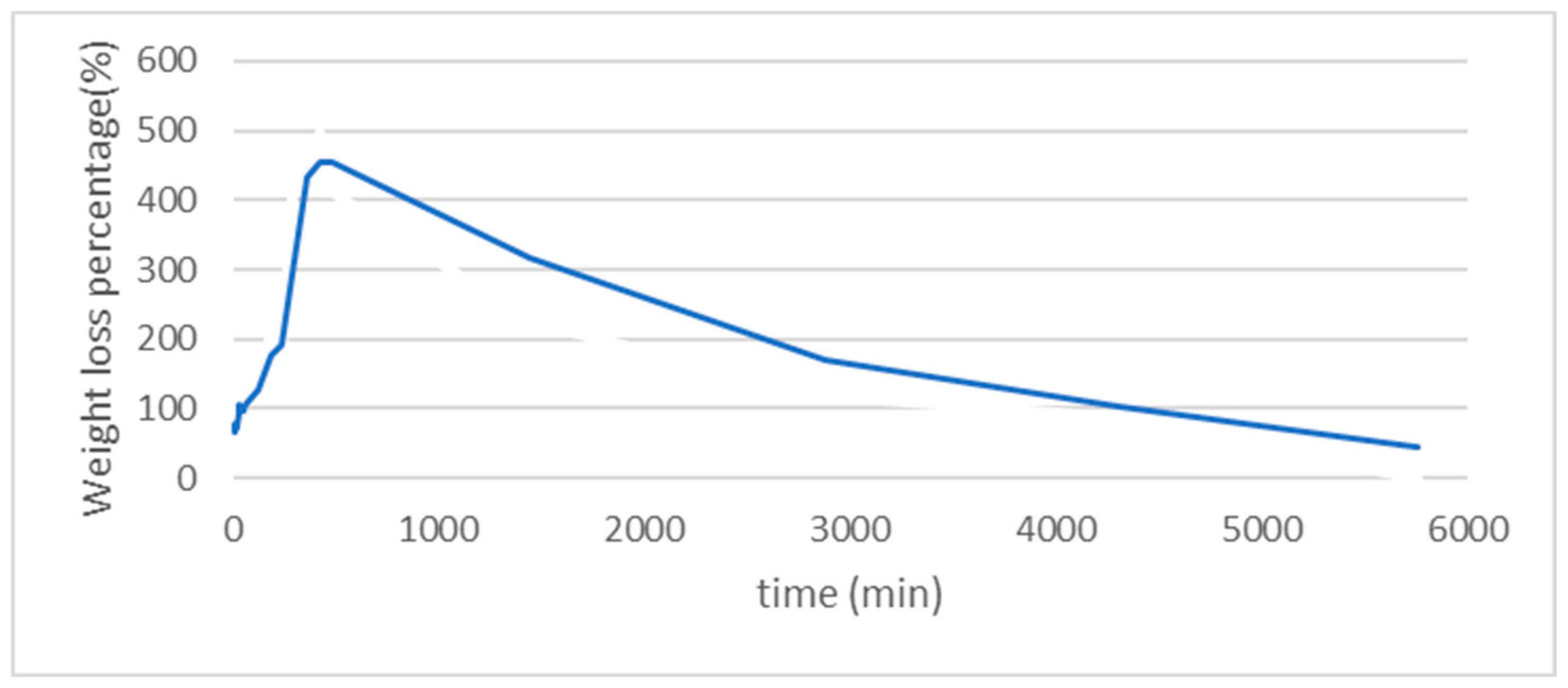

The weight loss and swelling test results are shown in

Figure 6. During the first 100 minutes, the swelling is rapid (more than 500 times) and more effective compared to the following hours. The loss process can extend up to 3 days. This swelling capacity confirms the system’s affinity for biological environments and enhances the interaction between the system and cells. Our findings partially align with previous reports [

22].

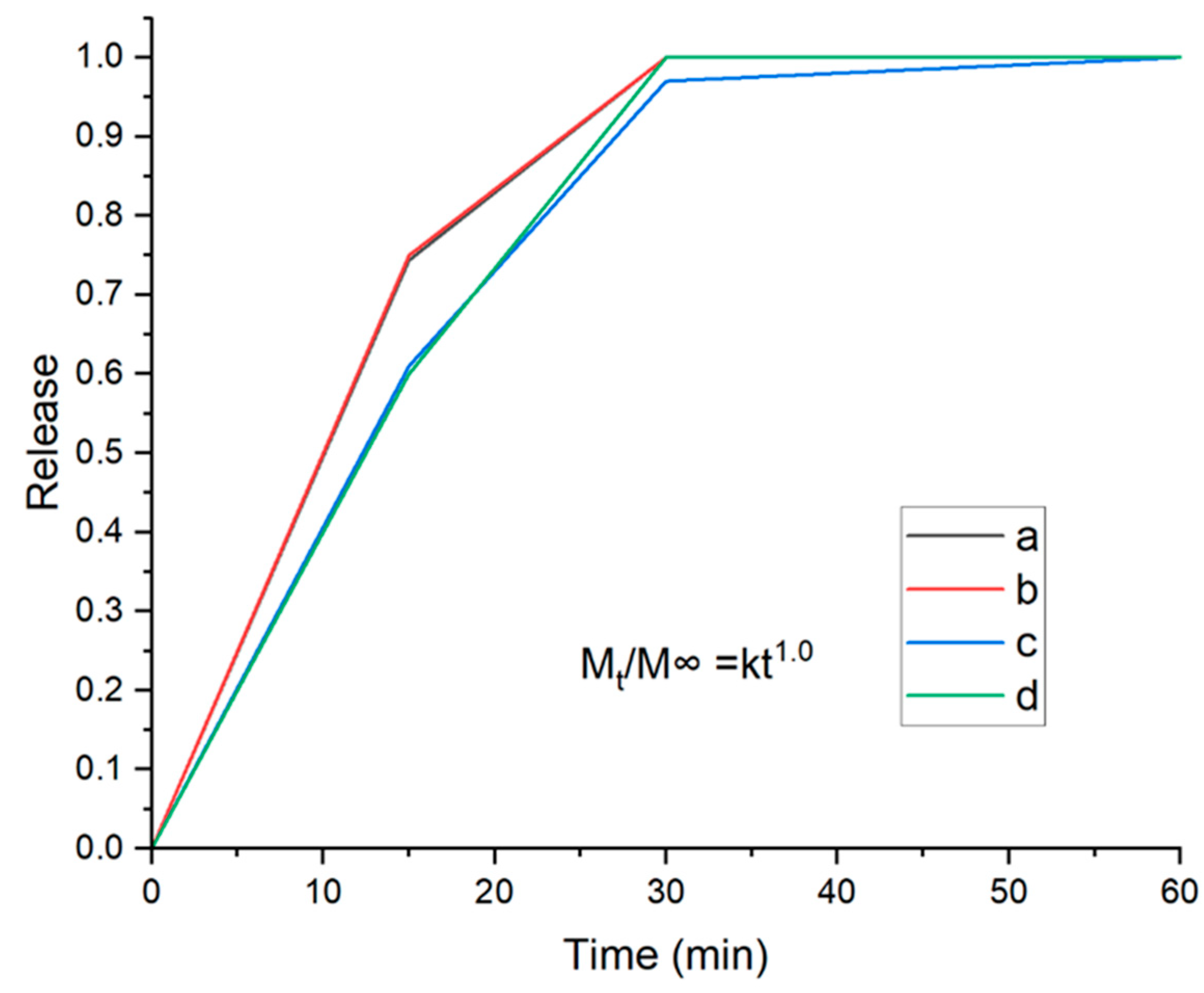

There is a correlation between the drug release process and HPMC concentration, as observed using the UV-VIS test. Reducing the amount of HPMC results in faster drug release. Our current data are supported by previous research [

29]. Increasing the amount of HPMC enhances the system’s swelling, prolonging the dissolving and release period, as shown in

Figure 7.

The theory model was built according to the Higuchi equation, employing the power law for polymeric films [

30]. This leaves the Higuchi equation with values for n between 0.5 and 1.0. Where M∞ refers to the total of the active molecule, Mt is the active molecule released on the time t and k is a constant, which depends on other variables.

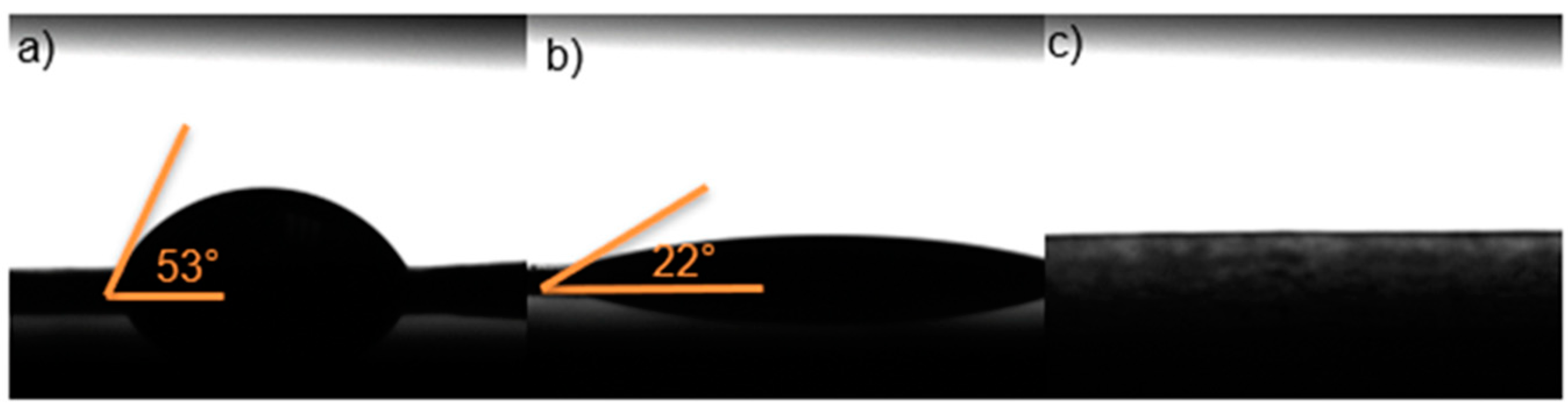

According to the results obtained with the contact angle study (

Figure 8) of the three films, by increasing the amount of HPMC, the contact angle becomes smaller. Because all three samples showed angles smaller than 90°, indicating that the system is hydrophilic. In these tissues (cells)-substrate interaction could permit to be an indicator of biocompatibility. In

Figure 9c the contact angle wasn’t allowed to be measured, because its hyper hydrophilic. This could cause an imbalance to be releasing of the drug. This finding is according with previous report indicating that a viable system should be with a contact angle between 0°-90° [

31].

To confirm the previous results, the

Figure 9 is showing that there was interaction among the polymeric film and the tissue. Because, no separation is present, the film is completely attached; a slight difference can be seen in the corner due to the swelling after applying the vaginal fluid simulant. A transformation takes place after the interaction between the tissue, the polymeric film, and the vaginal fluid simulant, according with Teworte et al, with longer interaction the system loses its original form and becomes a hydrogel [

32].

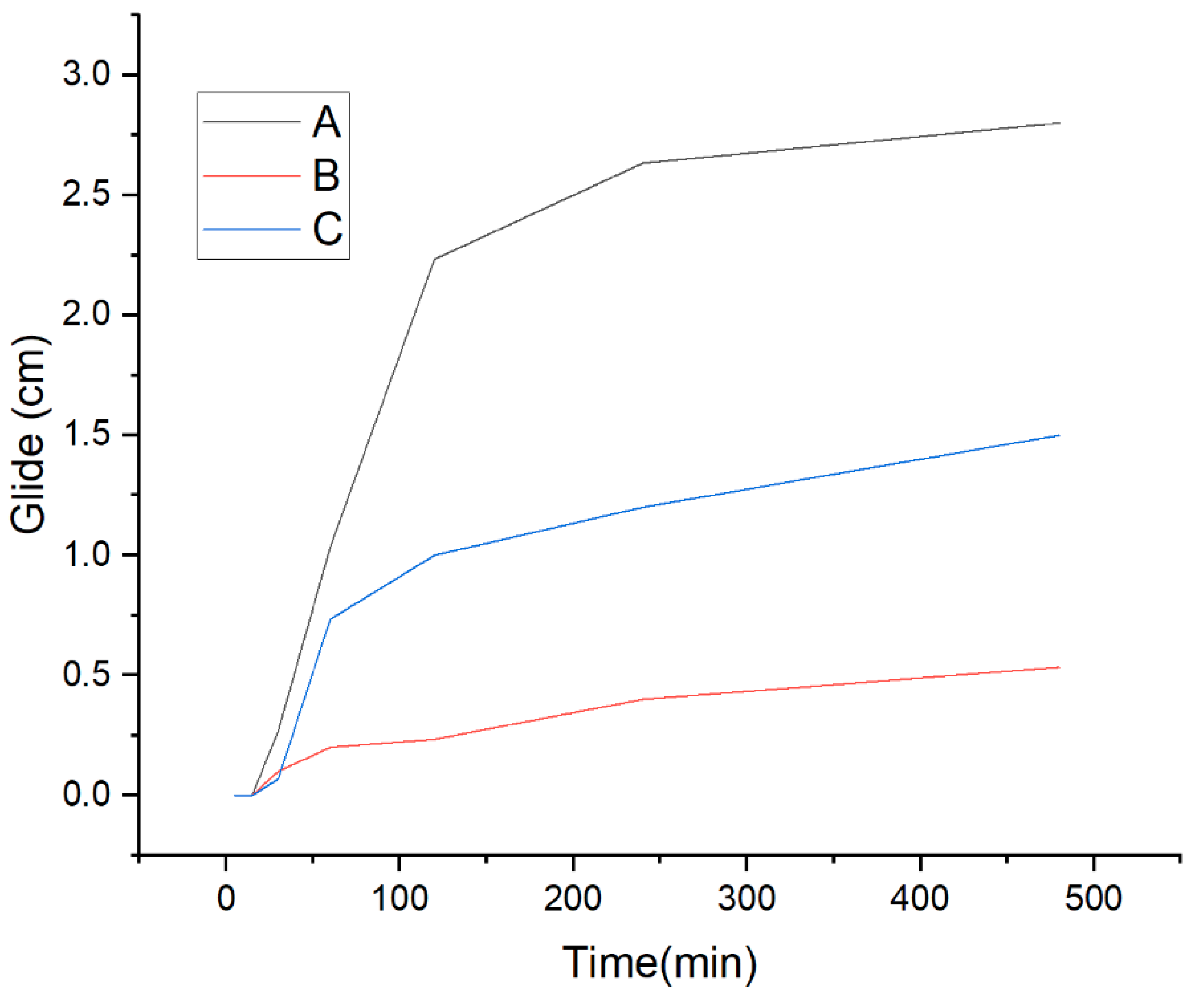

Figure 10 shows the glide within the time of the polymeric films loaded with active molecules or on their own. The retinol film had less glide in comparison to the others. This can be related to the lumpy topography that it showed in the FESEM characterization (see

Figure 4). In the case of ketorolac loaded films, it glided half the unloaded film. Even though the film by itself has many pores that according to Gyarmati may help to reach a determined compressive force, which when in contact with the mucus layer will transform into interfacial interactions and result in a deformation [

33], when it loses its original form and becomes a mucoadhesive gel [

32]. As can be seen, the lumpy topography helps to maintain the adhesion to the mucus barrier better than the porous, but overall, all three films glided less than 4 cm, less than half the average longitude of the vaginal canal which is 9 cm [

34].

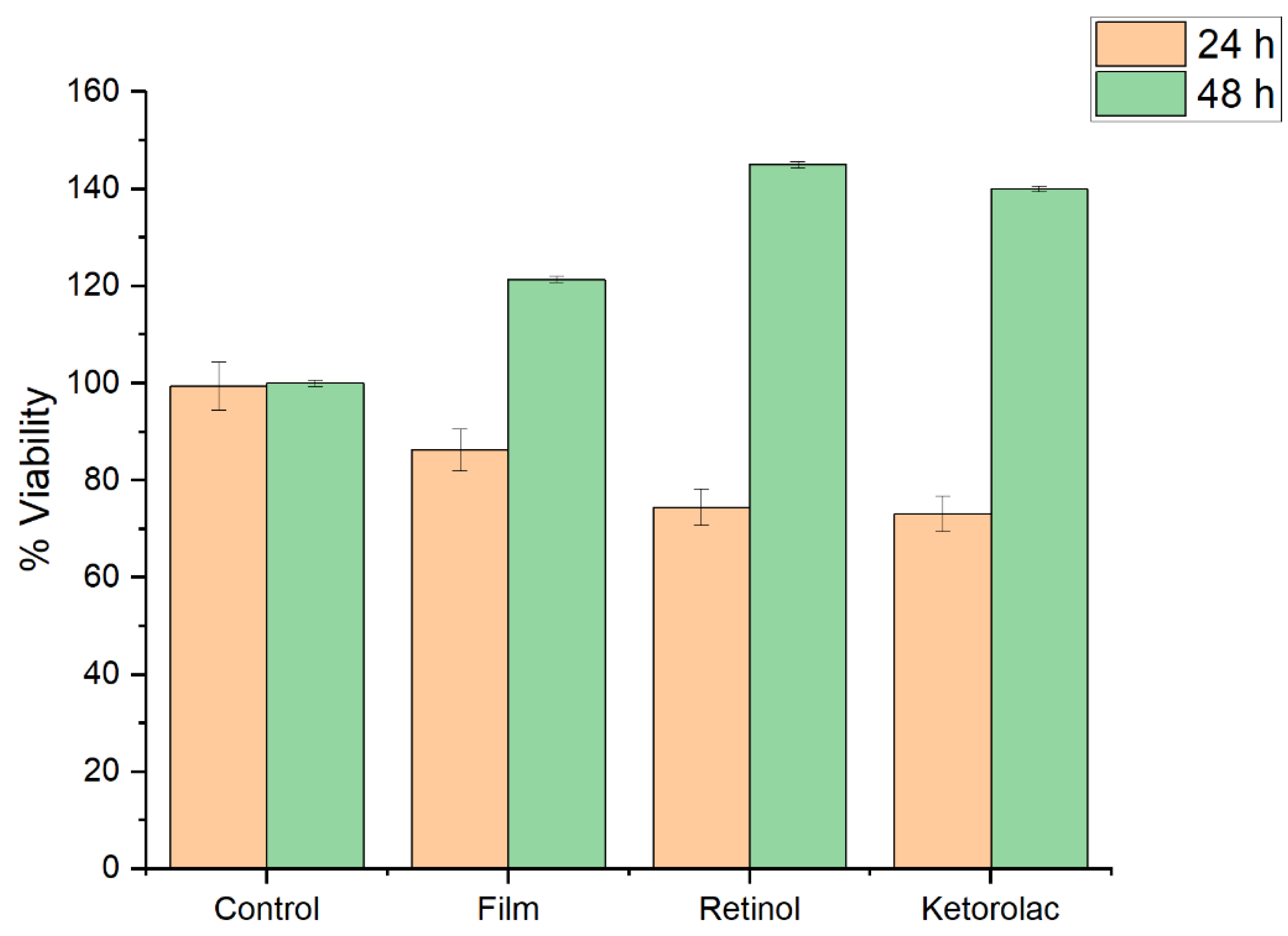

The cellular viability was evaluated for films harboring retinol, or ketorolac, at 24 and 48 h.

Figure 11 showed that at 24 h the cell viability has a little impact, but a recovering for the 48 h is observed.

Cervical cancer (CC) poses a significant public health challenge globally, including in Mexico [

1]. Persistent Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection is widely recognized as the primary risk factor for CC development [

2]. Cervicovaginal lesions frequently occur in association with sexual activity. Moreover, it’s well-documented that microabrasions in the cervical epithelium during sexual activity facilitate HPV infections.

Previous reports have highlighted the importance of Cellular Retinol Binding Protein 1 (CRBP1) protein expression and retinoids as crucial molecular mechanisms involved in the basal cell layer of healthy cervical epithelium. However, a lack of CRBP1 expression and low retinol serum levels are more commonly observed in CC [

35]. Recent data from our research team indicate that the administration of retinol alongside cisplatin can eradicate over 80% of cancerous cells (data currently undergoing publication). These findings suggest that utilizing the HPMC-PEG-retinol system could serve as a promising and innovative approach for treating cervicovaginal lesions.

3. Materials and Methods

In the present work, various materials were used, including HPMC, dichloromethane, methanol, albumin from fetal serum, lactic acid, urea (Sigma-Aldrich); PEG 400, glycerol (Alfa Aesar); retinol (Spring Valley); ketorolac (LIOMONT); sodium chlorate, acetic acid, hydrochloric acid (J.T. Baker); potassium hydroxide (MCB); calcium hydroxide (Fermont); and glucose (FAGA LAB).

The synthesis of polymeric films followed the method previously reported by Grameen et al. [

22]. Briefly, a mixture of HPMC, PEG 400, and dichloromethane in methanol at a ratio of 3:1 was stirred at 5,000 rpm for 1 hour using the solvent evaporation technique (see

Table 1). Dichloromethane was poured, and HPMC was slowly added while stirring. PEG 400 and retinol were then added sequentially, with stirring between each addition. Methanol was finally added, and the mixture was stirred until uniform. The system was dried in a Pyrex petri dish for 48 hours at 30°C [

9]. For ketorolac-loaded films, the drug was added to a cut area of 4 cm², with 1 ml for every proportion (

Table 1).

The vaginal fluid simulant was prepared according to Owen’s methodology [

36], consisting of distilled water (900 mL), sodium chlorate (3.5 g), sodium hydroxide (1.4 g), calcium hydroxide (0.22 g), albumin (0.018 g), lactic acid (2 mL), acetic acid (1 mL), glycerol (0.16 mL), urea (0.4 g), glucose (5 g), and hydrochloric acid to adjust the pH to 4.5.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) characterization was performed using a FESEM Hitachi SU5000 with a base of 51 mm and a working distance of 12 mm in low-pressure mode (30 Pa) with a voltage of 15 kV for backscattered and secondary electron imaging.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using a TA Instruments SDT Q600, with the temperature ranging from 20°C to 200°C to monitor the film’s dehydration.

To determine the functional groups in the film, Infrared (IR) spectra were obtained using a Nicolet 6700 instrument. The films were cut and placed on an ATR adapter with a germanium crystal for analysis. All spectra were registered over 100 scans with a resolution of 16 cm⁻¹, and all samples were scanned in the range of 550-4000 cm⁻¹.

To conduct the retinol release test, the first step involved developing a calibration curve, represented by the following equation:

Subsequently, the sample was exposed to a PBS solution with a pH of 4.5 to simulate vaginal fluids. The theoretical calculation of retinol release followed the Higuchi equation, expressed as:

Where M∞ is the total of drug loaded in the system, Mt the active molecule released on the time t y k is a constant that depends on the variables of the system and n varies according to the values of the table that can go from 0.5 to 1.0.

To evaluate cellular metabolic activity, the MTT assay (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) was used. This colorimetric analysis measures enzyme activity, resulting in a variation of the purple color of the MTT dye.

Osteoblasts were obtained from a primary culture and used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the HPMC and PEG 400 polymeric film. The osteoblasts were cultured in DMEM media and distributed at 5,000 cells/well. They were then placed in a humidified incubator with 5% CO

2 at 37°C. The films were sterilized using UV radiation. The cells were deposited in wells containing the film, film with retinol, and film with ketorolac, and subsequently incubated for 24 hours and 48 hours. The MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to the wells and incubated for 4 hours at 37°C. After the MTT was removed, 100 µL of DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals formed. Cell viability (%) was measured at λ=570 nm [

37,

38].

The contact angle and images of adhesion were taken with a Krüss system DSA30. The adhesion of the system was first evaluated through the contact angle measurement and by assessing glide using a system as shown in

Figure 1. Porcine vaginal tissue was obtained post-slaughter, cut into 5 cm pieces, and stored for 6 hours following the Teworte methodology [

39] (

Figure 1). The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

4. Conclusions

The characteristics such as size, shape, and distribution of porosity of the current films can be altered based on HPMC concentrations. The humidity and contact angle may also vary depending on the amount of polymer used. Interestingly, upon contact with fluids, the film transforms into a mucoadhesive gel, swelling for at least 100 minutes and degrading within approximately 3-4 days. When the polymeric film is loaded with different active molecules, intermolecular hydrogen bonds form, with the active molecules occupying the pores, resulting in a lumpier film that adheres better to the mucus barrier. Furthermore, the present film, whether with or without retinol, demonstrates biocompatibility. Drug delivery using this polymeric system is supported by the Higuchi equation.

In summary, this study represents emerging proof-of-concept research utilizing an HPMC-retinol film system to aid in the treatment of cervicovaginal lesions. It is plausible to hypothesize that this system could potentially be extended for the treatment of skin lesions as well.

Author Contributions

Maryel E. Hernández-González: Writing – original draft; Claudia A. Rodríguez-González: Review and editing manuscript; Laura E. Valencia-Gómez: Formal Analysis and review methodology; Juan F. Hernández-Paz: Review methodology; Florinda Jimenez-Vega: Formal analysis; Mauricio Salcedo-Vargas: Review and editing manuscript; Imelda Olivas-Armendáriz: Project administration and writing – Review & Editing.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez, Committee on Ethics in Research (protocol code CEI-2023-2-1076 and October 19, 2023).

Acknowledgments

Maryel E. Hernandez-Gonzalez thanks the National Council of Humanities, Sciences and Technologies (CONAHCYT) for its support of the Doctoral Program in Materials Sciences, the Universidad autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ) working group for the facilities given to developing this investigation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- E. Lara-Torre, F. A. Valea, Pediatric and adolescent gynecology: Gynecologic Examination, Infections, Trauma, Pelvic Mass, Precocious Puberty, in: Comprehensive Gynecology, Elsevier, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Dolan, C. C. Hill, F. A. Valea, Benign gynecologic lesions: Vulva, Vagina, Cervix, Uterus, Oviduct, Ovary, Ultrasound Imaging of Pelvic Structures, in: Comprehensive Gynecology, Elsevier, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Buttaravoli, S. M. Leffler, Foreign Body, Vaginal, in: Minor Emergencies, Elsevier, 2012, pp. 345–346. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Haefner, C. P. Crum, Chapter 11 - Benign Conditions of the Vagina, in: Diagnostic Gynecologic and Obstetric Pathology, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 258–274. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Wright and H. Wessells, Urinary and Genital Trauma, in Penn Clinical Manual of Urology, P. M. Hanno, S. B. Malkowicz, and A. J. Wein, Eds., Elsevier Inc, 2007, pp. 283–309.

- F. Notario-Pérez, R. Cazorla-Luna, A. Martín-Illana, R. Ruiz-Caro, A. Tamayo, J. Rubio, María-Dolores Veiga, Optimization of tenofovir release from mucoadhesive vaginal tablets by polymer combination to prevent sexual transmission of HIV, Carbohydr Polym. 179, (2018) 305–316. [CrossRef]

- R. Mishra, P. Joshi, and T. Mehta, Formulation, development and characterization of mucoadhesive film for treatment of vaginal candidiasis, Int J Pharm Investig. 6, (2016) 47-55. 10.4103/2230-973X.176487.

- L. Kumar, M. S. Reddy, R. K. Shirodkar, G. K. Pai, V. T. Krishna, R. Verma, Preparation and characterisation of fluconazole vaginal films for the treatment of vaginal Candidiasis, Indian J Pharm Sci. 75, (2013) 585–590.

- C. Grammen, G. Van den Mooter, B. Appeltans, J. Michiels, T. Crucitti, K. K. Ariën, K. Augustyns, P. Augustijns, J. Brouwers, Development and characterization of a solid dispersion film for the vaginal application of the anti-HIV microbicide UAMC01398, Int J Pharm. 475, (2014) 238–244. [CrossRef]

- K. I. Pappa, G. Kontostathi, V. Lygirou, J. Zoidakis, and N. P. Anagnou, Novel structural approaches concerning HPV proteins: Insight into targeted therapies for cervical cancer (Review), Oncology Reports, 39, (2018) 1547–1554. [CrossRef]

- N. Lupo, B. Fodor, I. Muhammad, M. Yaqoob, B. Matuszczak, A. Bernkop-Schnürch, Entirely S-protected chitosan: A promising mucoadhesive excipient for metronidazole vaginal tablets, Acta Biomater. 64, (2017) 106–115. [CrossRef]

- E. H. Harrison, Vitamin A, in: Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences, Elsevier, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Redel, B. Polsky, Nutriotion, Immunuty, and Infection, in: Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 9th ed., Elsevier, Inc. , 2020, pp. 132–141.

- M. A. de Bittencourt Pasquali, D. Pens Gelain, F. Zeidán-Chuliá, A. Simões Pires, J. Gasparotto, S. Resende Terra, J. C. Fonseca Moreira, Vitamin A (retinol) downregulates the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) by oxidant-dependent activation of p38 MAPK and NF-kB in human lung cancer A549 cells, Cell Signal, 25, (2013) 939–954. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Trifiletti, Vitamin A, in Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences, Elsevier, 2003, pp. 719–721. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Biesalski, D. Nohr, New Aspects in Vitamin A Metabolism: the Role of Retinyl Esters as Systemic and Local Sources for Retinol in Mucous Epithelia 1, J Nutr. 134, (2004) 3453S-3457S. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Biesalski, U. Sobeck, H. Weiser, Topical application of vitamin A reverses metaplasia of rat vaginal epithelium: a rapid and efficient approach to improve mucosal barrier function, Eur J Med Res. 28 (2001) 391-8. PMID: 11591530.2001.

- J. M. Stevens, GYNAECOLOGY FROM ANCIENT EGYPT: THE PAPYRUS KAHUN: A TRANSLATION OF THE OLDEST TREATISE ON GYNAOCOLOGY BAS SURVIVED FROM THE ANCIENT WORLD, Med J Aust. (1975) 949–952, 1975. [CrossRef]

- N. J. Alexander, E. Baker, M. Kaptein, U. Karck, L. Miller, E. Zampaglione, Why consider vaginal drug administration?, Fertil Steril. 82, (2004) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Sahoo, P. Kumar Nayak, D. K. Sarangi, and T. K. Sahoo, Intra Vaginal Drug Delivery System: An Overview, Am J Adv Drug Deliv. 1 (2013) 43–45. http://doi.org/ISSN-2321-547X.

- F. Acarturk, Mucoadhesive Vaginal Drug Delivery Systems, Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 3, (2009) 193–205. [CrossRef]

- F. Notario-Pérez, A. Martín-Illana, R. Cazorla-Luna, R. Ruiz-Caro, L.-M. Bedoya, J. Peña, M.-D. Veiga, Development of mucoadhesive vaginal films based on HPMC and zein as novel formulations to prevent sexual transmission of HIV, Int J Pharm. 570, (2019) 118643. [CrossRef]

- R. Shaikh, T. Raj Singh, M. Garland, A. Woolfson, and R. Donnelly, Mucoadhesive drug delivery systems, J. pharm. bioallied sci. 3, (2011)89–100, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Gad, Polymers, in: Encyclopedia of Toxicology: Third Edition, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 1045–1050. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Escudero, C. Ferrero, and M. R. Jiménez-Castellanos, Compaction properties, drug release kinetics and fronts movement studies from matrices combining mixtures of swellable and inert polymers: Effect of HPMC of different viscosity grades, Int J Pharm. 351, (2008) 61–73. [CrossRef]

- International Journal of Pharmaceutics, “HPMC .” Accessed: Feb. 21, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/search?qs=HPMC&publicationTitles=271189&lastSelectedFacet=publicationTitles.

- DRUGBANK online, “Polyehtylene glycol 400,” Polyethylene glycol 400. Accessed: Feb. 21, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB11077.

- U. G. T. M. Sampath, Y. C. Ching, C. H. Chuah, J. J. Sabariah, and P. C. Lin, Fabrication of porous materials from natural/synthetic biopolymers and their composites, Materials. 9, (2016) 1–32. [CrossRef]

- J. Siepmann, Y. Karrout, M. Gehrke, F. K. Penz, F. Siepmann, Predicting drug release from HPMC/lactose tablets, Int J Pharm. 441, (2013) 826–834. [CrossRef]

- J. Siepmann, N. A. Peppas, Modeling of drug release from delivery systems based on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 64, (2012) 163–174. [CrossRef]

- G. Agrawal, Y. S. Negi, S. Pradhan, M. Dash, S. K. Samal, 3- Wettability and contact angle of polymeric biomaterials. Characterization of Polymeric Biomaterials, 2017 pp. 57-81. [CrossRef]

- S. Teworte, S. Aleandri, J. R. Weber, M. Carone, P. Luciani, Mucoadhesive 3D printed vaginal ovules to treat endometriosis and fibrotic uterine diseases, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.vol. 188 (2023) 106501. [CrossRef]

- B. Gyarmati, G. Stankovits, B. Á. Szilágyi, D. L. Galata, P. Gordon, A. Szilágyi, A robust mucin-containing poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogel model for the in vitro characterization of mucoadhesion of solid dosage forms, Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 213, (2022) 112406. [CrossRef]

- J. López-Olmos, “Vaginal length: a multivariable analysis,” Clin Invest Ginecol Obstet. 32, (2006) 230–243. [CrossRef]

- M. Mendoza-Rodriguez, H. Arreola, A. Valdivia, R. Peralta, H. Serna, V. Villegas, P. Romero, B. Alvarado-Hernández, L. Paniagua, D. Marrero-Rodríguez, M.A. Meraz, M. Salcedo, Cellular retinol binding protein 1 could be a tumor suppressor gene in cervical cancer, Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 15, (2013) 1817-1825. PMID: 24040446.

- D. Pens Gelain, M. A. de Bittencourt Pasquali, A. Zanotto-Filho, L. F. de Souza, R. B. de Oliveira, Fábio Klamt, J. C. Fonseca Moreira, Retinol increases catalase activity and protein content by a reactive species-dependent mechanism in Sertoli cells, Chem Biol Interact. 174, (2008) pp. 38–43. [CrossRef]

- D. H. Owen, D. F. Katz, A Vaginal Fluid Simulant, An international reproductive journal contraception. 59, (1999) 1-95. [CrossRef]

- N. Nematpour, P. Moradipour, M. M. Zangeneh, E. Arkan, M. Abdoli, L. Behbood, The application of nanomaterial science in the formulation a novel antibiotic: Assessment of the antifungal properties of mucoadhesive clotrimazole loaded nanofiber versus vaginal films, Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 110, (2020) 110635. [CrossRef]

- Merck KGaA, “Protocolo del análisis de la viabilidad y la proliferación celulares con MTT.” Accessed: May 28, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/MX/es/technical-documents/protocol/cell-culture-and-cell-culture-analysis/cell-counting-and-health-analysis/cell-proliferation-kit-i-mtt#.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).