1. Introduction

Buccal and nasal drug delivery can avoid the gastrointestinal tract and first-pass metabolism, it has great potential for both localized and systemic treatments. How-ever, present systems have issues that prevent the best possible therapeutic results, including inconsistent drug release, poor mucosal adherence, and low drug solubility. These drawbacks lessen the therapeutic effectiveness of buccal solutions and emphasize the necessity for cutting-edge materials that can maintain drug release in the oral environment while preserving mechanical integrity [

1].

The anti-Alzheimer medication Rivastigmine, a slowly reversible, centrally selective dual inhibitor of butyrylcholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase that increases acetylcholine availability levels and improves neurotransmission, is used in this work to propose a nano lipid mucoadhesive gel using a novel mucoadhesive polymer [

2]. It has been demonstrated to enhance everyday tasks, including living, cognition, be-haviour, and global function, and it has proven effective in treating the symptoms of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. Studies of cholinesterase inhibitor dose-response relationships support improved enzyme inhibition, which raises efficacy [

3].

Since the constituents, size, structure, physico-chemical characteristics, and synthetic methods of manufacture all affect the functioning and efficacy of SLNs, it is important to clarify the sophisticated production technologies utilized to make SLNs for drug delivery. Newly developed lipid nanoparticles have gradually ad-dressed the drawbacks of earlier SLNs [

4]. As improved SLNs, second-generation nano lipid carriers (NLCs) are superior drug delivery vehicles that get around issues like drug ejection and the abrupt release of active therapeutic ingredients for brain medication delivery. By modifying SLNs to improve medication delivery to the brain, it may be possible to increase the drug’s bioavailability and pass the blood-brain barrier [

5].

A unique drug delivery method that protects the medication from first-pass metabolism, facilitates site-specific drug distribution, and increases overall bioavailability is the mucoadhesive drug delivery system [

6]. Drugs with muco-penetrating and mucoadhesive qualities can be administered by various routes, such as the nasal, ocular, vaginal, rectal, and buccal. Generally speaking, mucoadhesive oral gels retain favorable adherence to the oral mucosa [

7]. Oral mucosal delivery shares many of the same benefits as enteral drug delivery, which is thought to be the principal method of medication ingestion. In addition to its relatively inexpensive prices, administration, and satisfactory patient compliance, it offers other benefits. In addition to being simpler for people who have trouble swallowing, these medications are frequently more convenient because they don’t require liquid to be taken [

8]. Drugs do not break down in the GI tract environment, but they can enter the systemic circulation directly and have a quicker reaction time by avoiding the hepatic first-pass metabolism. Developments in mucoadhesive technology are making it easier to create innovative polymers and bio adhesive materials that can greatly extend the retention duration of medication formulations at mucosal sites. Among these materials are natural polymers made from plant parts such as seeds, gums, leaves, and so forth. This improves the drug’s close contact with the mucosal surface, which promotes improved absorption and therapeutic effectiveness [

9]

.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Ruthenium Red Test and Phytochemical Screening

Ruthenium reagent gives a red color which confirms the presence of mucilage. The phytochemical screening of

Moringa oleifera mucilage are presented in

Table 1. Phytochemical screening of moringa mucilage shows presence of alkaloids, saponins, steroids, flavonoids and carbohydrates with glycosides, protein, lipid and tannins absent. Presence of Carbohydrates, particularly polysaccharides (like mucilage, gums), contain abundant hydroxyl (–OH) and carboxyl (–COOH) groups. These groups form hydrogen bonds with the mucin layer of the mucosa which also swell in water, allowing interpenetration and better adhesion to mucosal surfaces.

2.2. Evaluation of RIV-SLNs

2.2.1. Particle Size, Zeta Potential and Morphology of Riv-SLNs

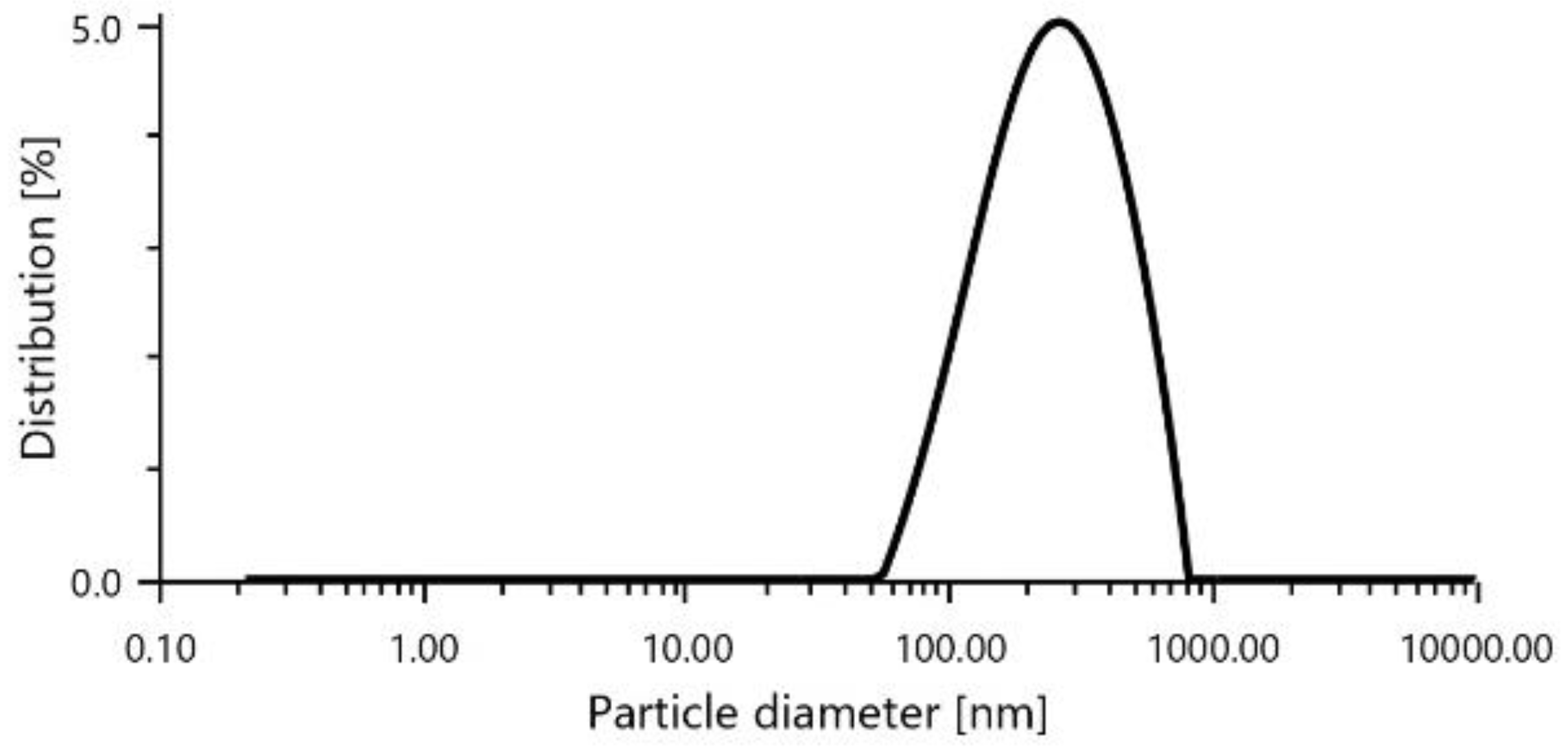

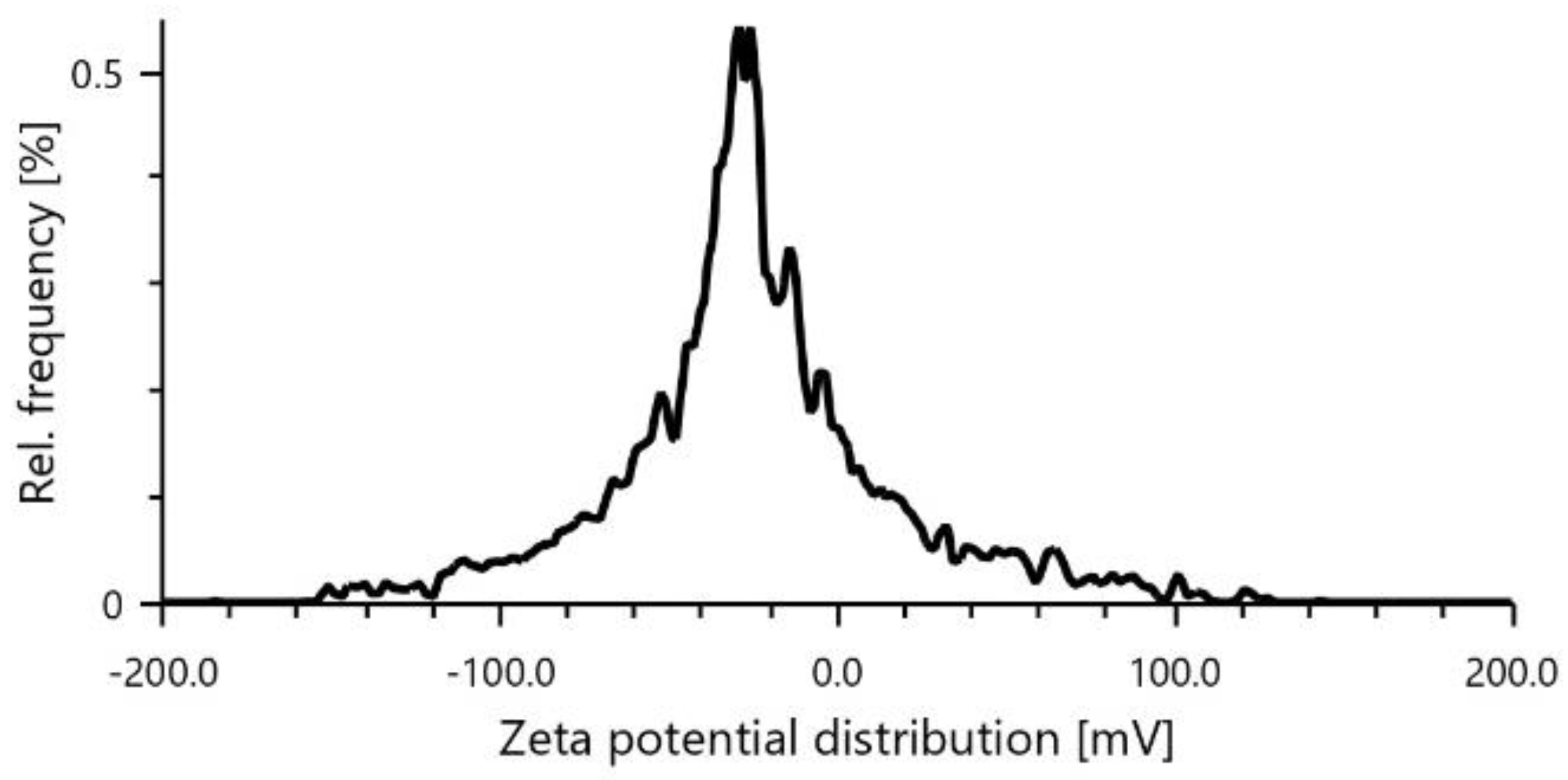

An average diameter of 222.2 nm and a PDI of 20.9,

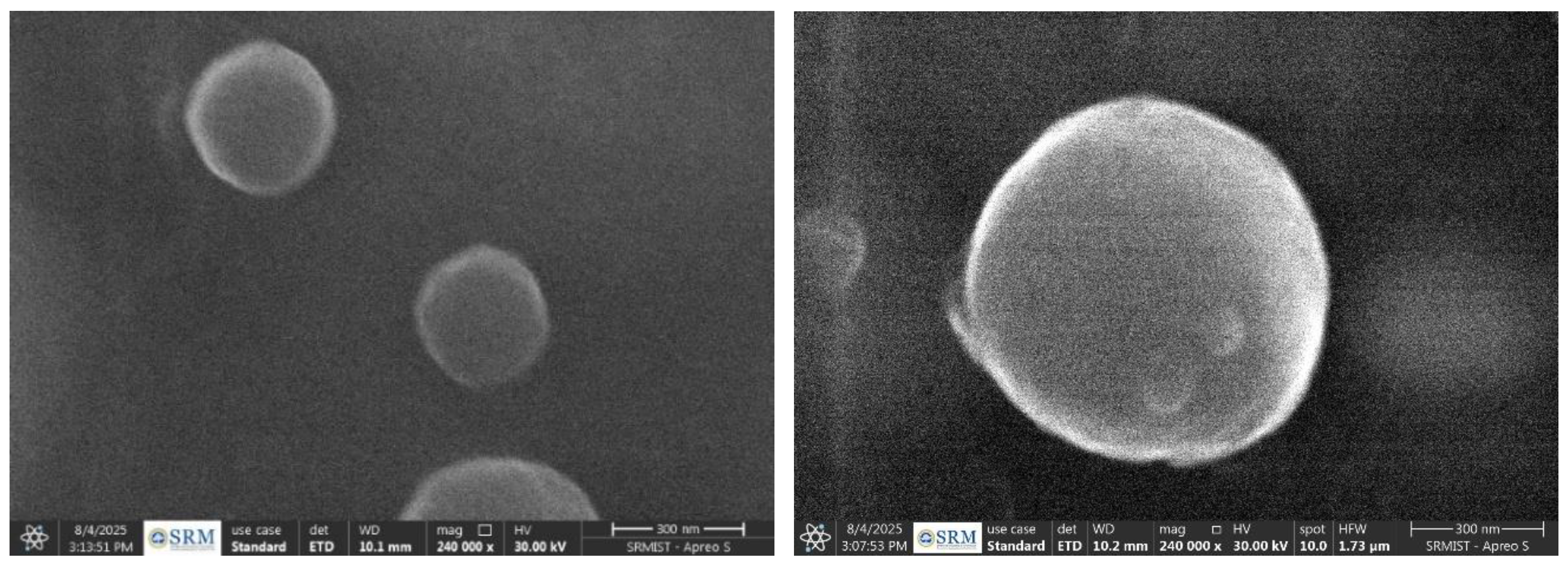

Figure 1 were found by particle size analysis, indicating a uniformly dispersed and consistent particle size. By inhibiting particle aggregation, the zeta potential measurement value of −24.9 mV indicated good colloidal stability. Evaluations of thermal stability, such as heating-cooling and freeze-thaw cycles, showed steady thermodynamic behavior without phase separation, guaranteeing the robustness of the formulation. Uniform droplet production was indicated by the SEM investigation, which revealed primarily spherical morphology with a smooth surface texture. The micrographs’ lack of crystalline structures demonstrated the formulation’s amorphous character, which is essential for improving solubility and bioavailability. Additionally, there was no discernible aggregation or structural abnormalities, demonstrating the nano emulsion’s superior dispersion quality and physical stability.

Three well-formed SLNs with perfect spherical morphology and smooth surface features are shown by the SEM investigation. Based on the 300 nm scale bar, the particles exhibit a consistent size distribution of roughly

Figure 3, suggesting that the nanoparticles were successfully formed within the ideal medicinal size range. The particles exhibit consistent spherical geometry, good dispersion, and little aggregation, indicating stable lipid matrix synthesis and appropriate surfactant stabilization. A successful SLNs synthesis that is appropriate for drug delivery applications with anticipated improved bioavailability and controlled release properties is confirmed by the smooth, defect-free surface topography seen at 240,000x magnification, which shows homogeneous lipid crystallization without polymorphic irregularities.

Figure 1.

Particle diameter of RIV-SLNs.

Figure 1.

Particle diameter of RIV-SLNs.

Figure 2.

Zeta potential of RIV-SLNs.

Figure 2.

Zeta potential of RIV-SLNs.

Figure 3.

SEM image of RIV-SLNs.

Figure 3.

SEM image of RIV-SLNs.

2.2.2. Encapsulation Efficiency

For the optimized formulation, the encapsulation efficiency achieved was 66.72 ± 1.2%, indicating successful incorporation and retention of rivastigmine within the lipid nanoparticle matrix. This corresponds to 6.67 mg of entrapped drug and 3.33 mg of free drug from a total loading of 10 mg, demonstrating effective drug entrapment within the Riv-SLNs structure.

2.2.3. The In Vitro Drug Release Study

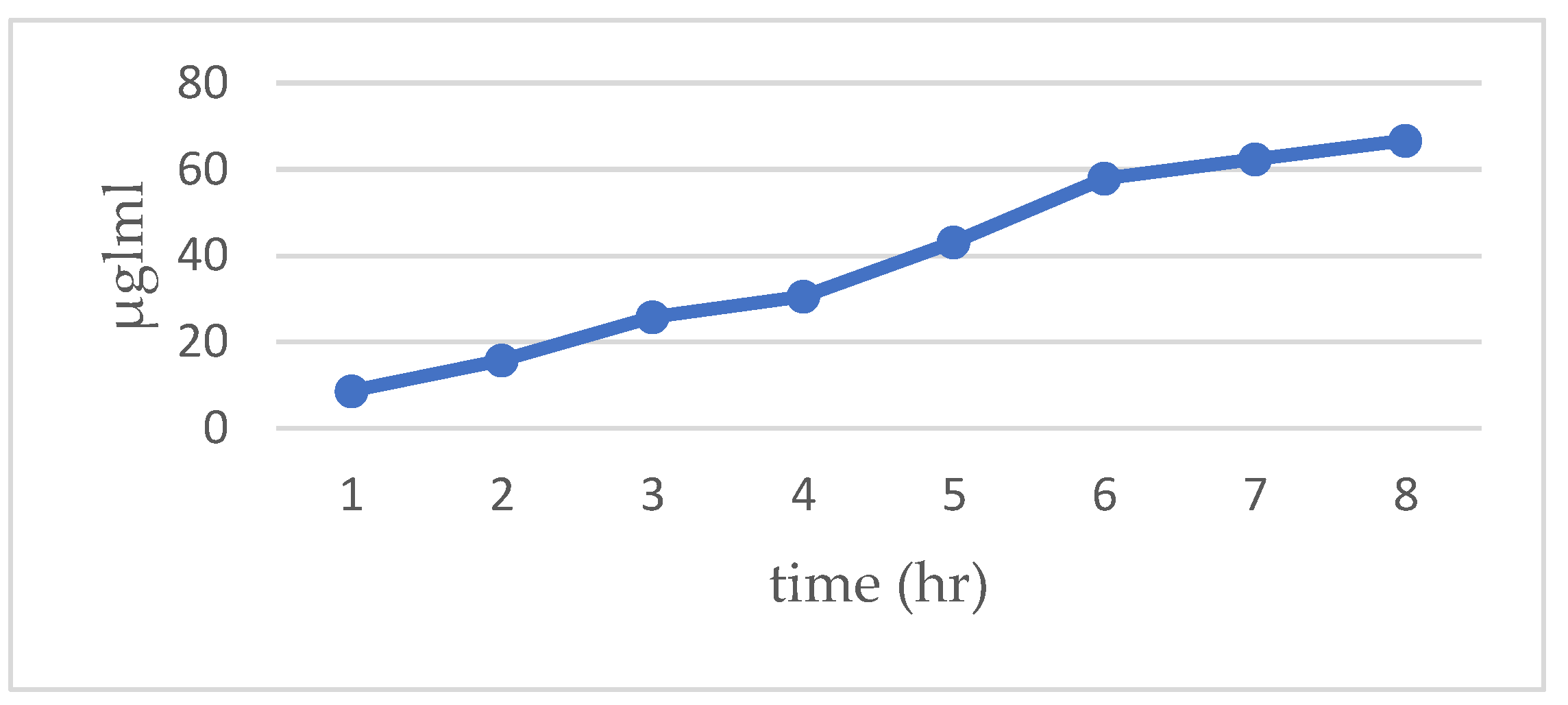

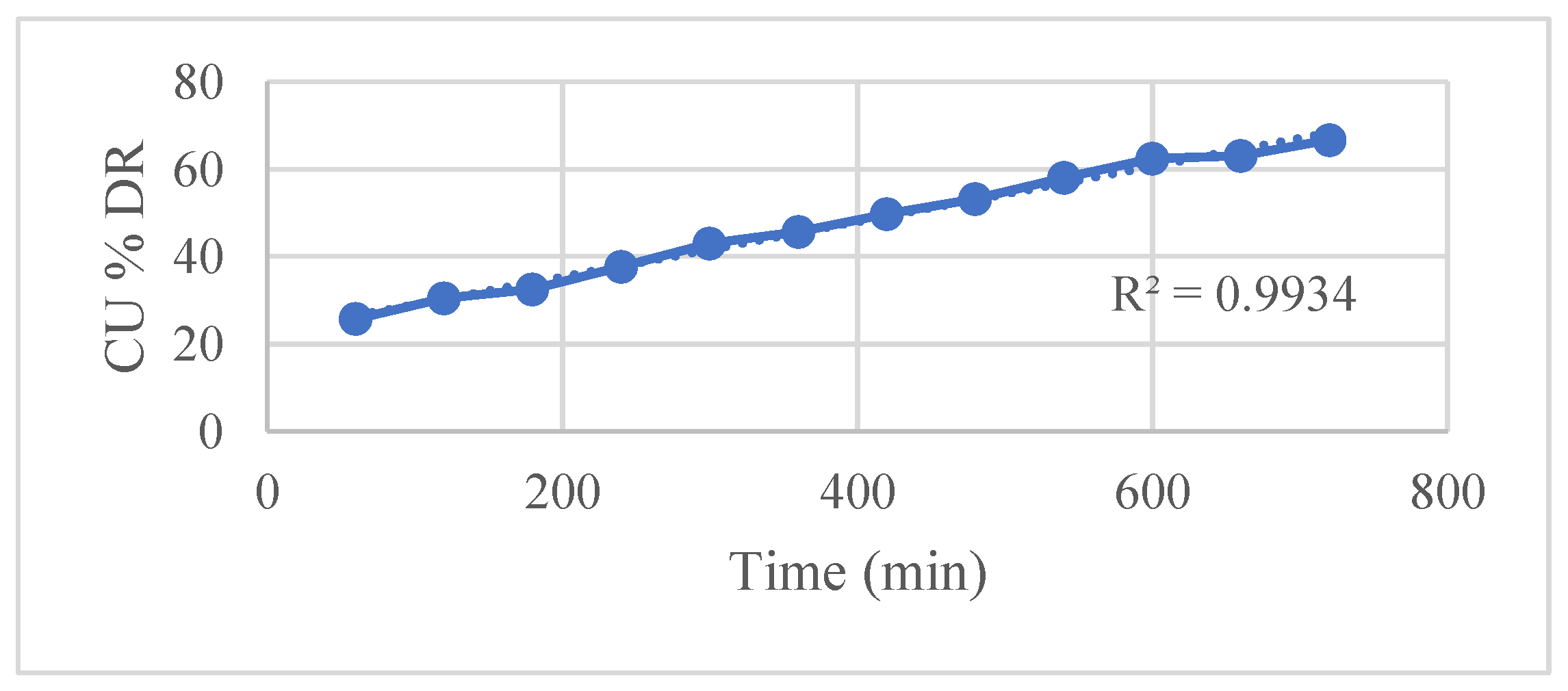

The in vitro drug release study of the formulation demonstrated a sustained release profile over 8 hours, with cumulative drug release reaching approximately 66.7% by the end of the period as shown in

Figure 4. Spectrophotometric measurements coupled with a validated calibration curve ensured accurate determination of drug concentrations at each time point.

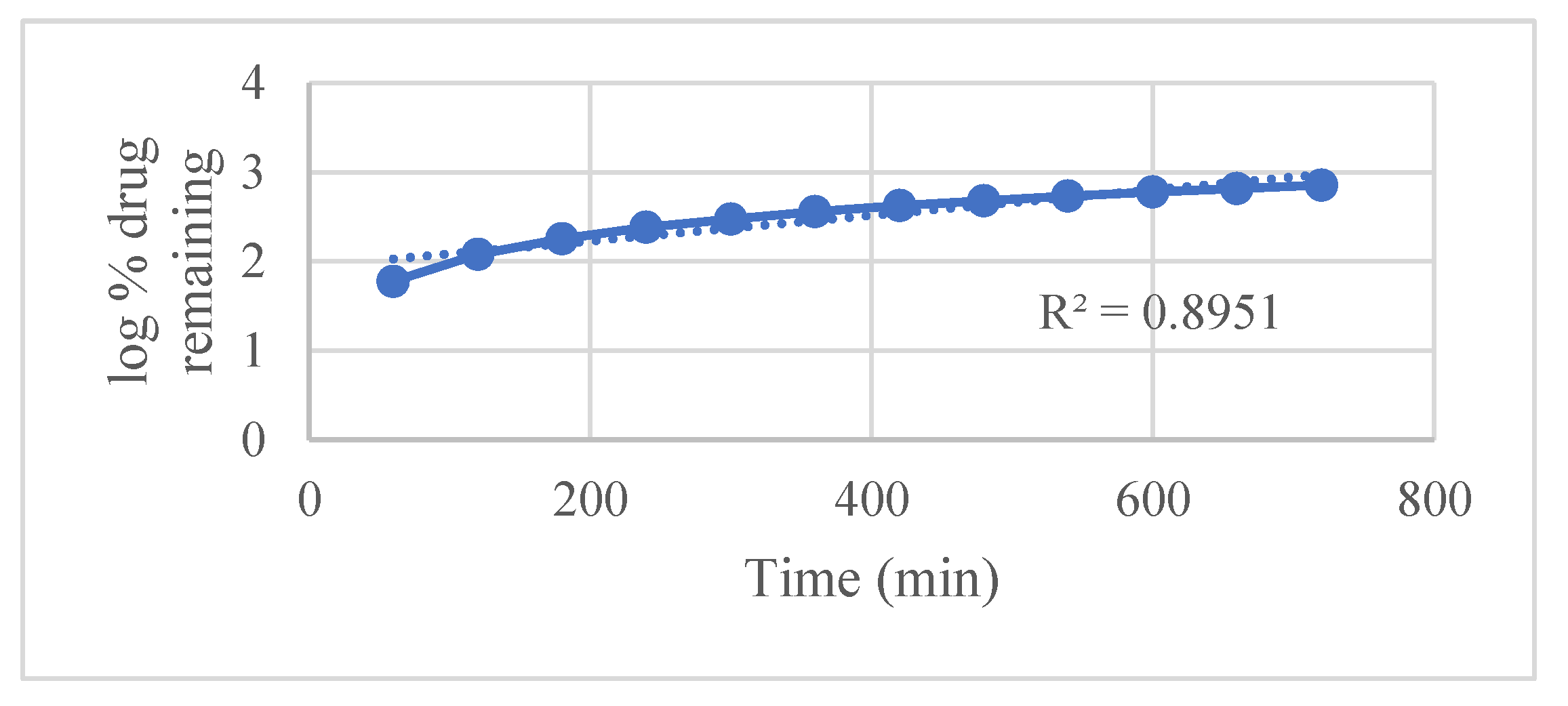

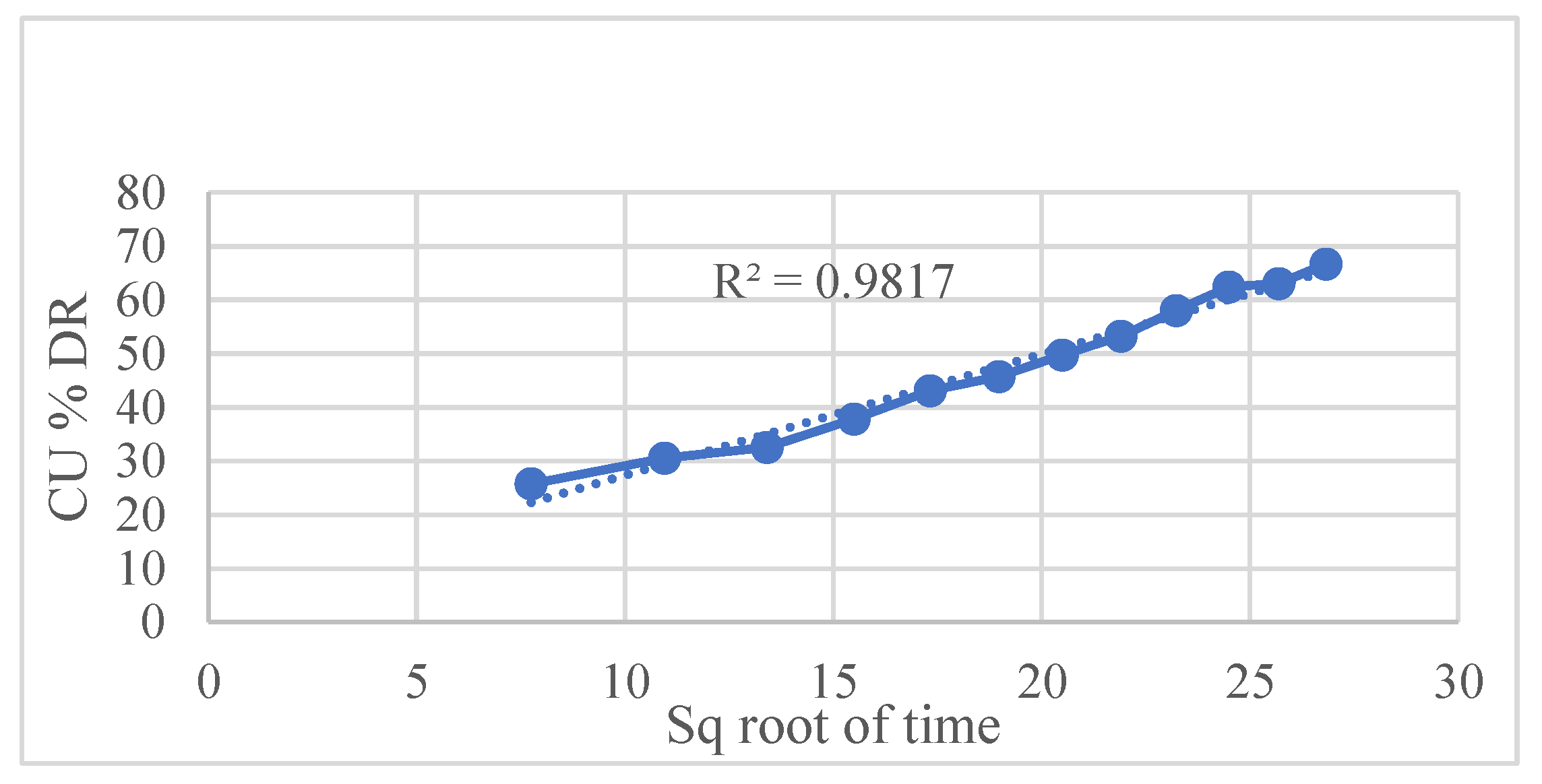

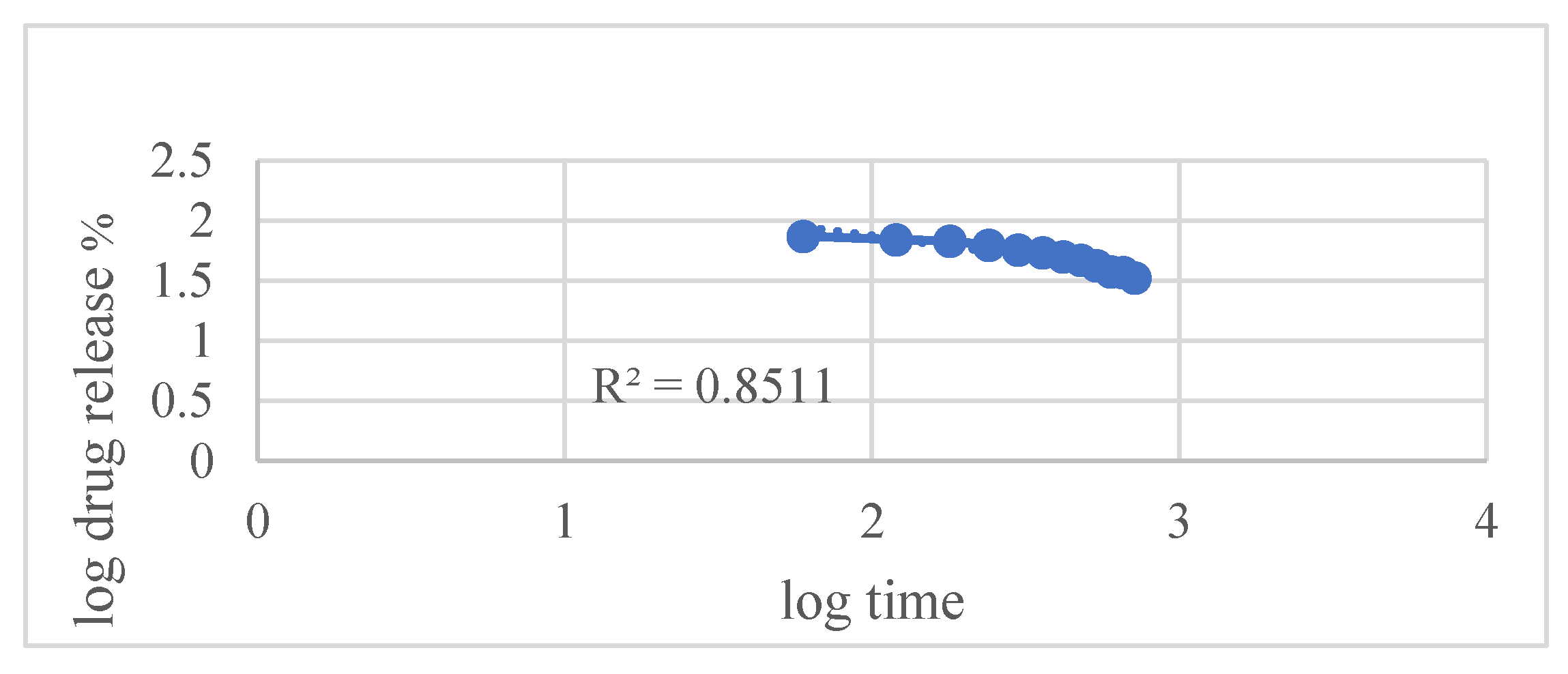

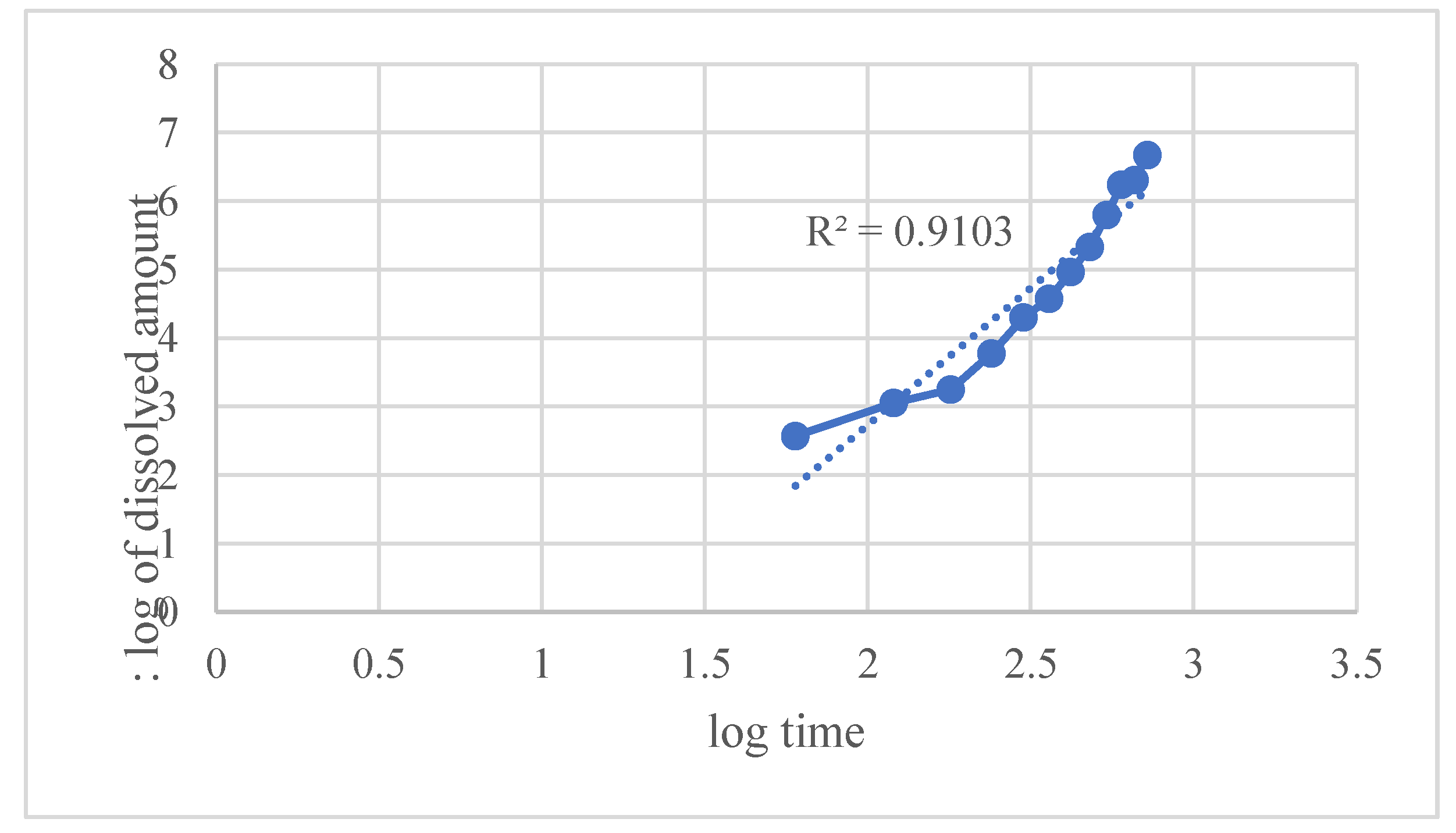

Kinetic modeling using various established release equations revealed that the Hixson–Crowell model best described the drug release mechanism, with an exceptionally high correlation coefficient (R² = 0.9948). This indicates that drug release is predominantly governed by matrix erosion accompanied by a decrease in surface area over time. Other models such as

Figure 5 zero-order,

Figure 6 first-order,

Figure 7 Higuchi, and

Figure 8 Korsmeyer–Peppas also showed good fits but were slightly less correlated compared to Hixson–Crowell.

Figure 9. The Weibull model provided a moderately good empirical fit.

Overall, the release kinetics suggest that the formulation exhibits primarily erosion-controlled sustained release, with some diffusion contribution. This profile is advantageous for maintaining consistent therapeutic drug levels over an extended duration, making the formulation suitable for controlled drug delivery applications.

Table 3.

kinetic drug release models of.

Table 3.

kinetic drug release models of.

| Model |

R² |

| Zero-order |

0.9934 |

| First-order |

0.9918 |

| Higuchi |

0.9817 |

| Hixson–Crowell |

0.9948 |

| Korsmeyer–Peppas |

0.9640 |

| Weibull |

0.9103 |

2.3. Evaluation of Riv-SLNs Loaded Mucoadhesive Gel

2.3.1. Physical Appearance, Homogeneity and pH of Riv-SLNs Loaded Mucoadhesive Gel

Gel form is opaque. It is white in color, no discoloration and no visible particles. It indicate the successful dispersion of the excipients. The prepared mucoadhesive gel exhibited excellent homogeneity, as confirmed by the absence of lumps, phase separation, or air bubbles upon visual and microscopic inspection. This uniform distribution of drug and excipients indicates proper mixing and ensures consistency in each dose of the formulation. The pH of gel is mildly acidic to nearly neutral. 6.1±0.4 It’s compatible with buccal formulations as well as nasal formulation, as the natural buccal and nasal environment is pH 6.8 to 7.

2.3.2. Swelling Index of Riv-SLNs Loaded Mucoadhesive Gel

The

Table 4 shows the swelling index of the formulation in 24 hrs. Maximum swelling index in 400%. The formulation is having a high swelling index which enhances the mucoadhesiveness. It resulted in the expedited disentanglement of the polymer chains and their interpenetration through the mucus layer.

2.3.3. Spreadability of Riv-SLNs Loaded Mucoadhesive Gel

The formulation showed good spreadability, indicating smooth flow properties and ease of application without undue drag or resistance, which is essential for patient comfort and effective mucosal coverage.

2.3.4. Mucoadhesive Strength of Riv-SLNs Loaded Mucoadhesive Gel

Mucoadhesive strength was tested 3 times and average is calculated. The average Mucoadhesive strength for buccal mucosa is found to 8890±1.1 dyne/cm2 and for nasal mucosa is 8322±1.4 dyne/cm2. Increased mucoadhesive strength correlates with reduced formulation leakage from the nasal cavity, resulting in improved retention and consequently more absorption through the nasal mucosal epithelium. Excessive mucoadhesive strength (i.e., exceeding 10,000 dyne/cm2) of the gel can harm the nasal mucosal membrane. All formulas remained inside the upper limit.

2.3.5. Ex Vivo Permeation Studies

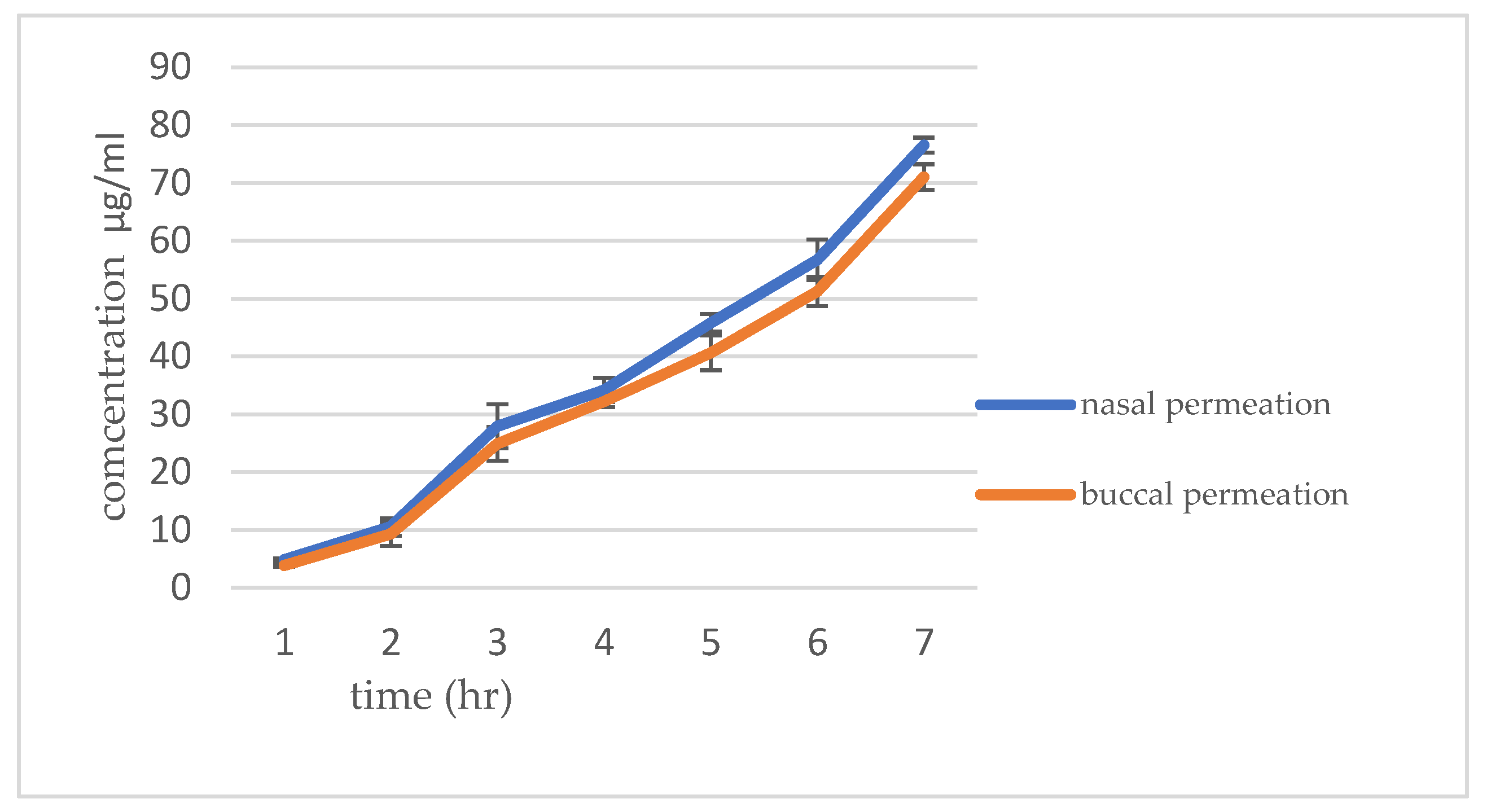

The

Figure 10 shows the ex-vivo permeation study was conducted to see the drug permeation of RIV-SLNPs mucoadhesive gel formulation in buccal and nasal mucosa. The permeation data are presented in

Table 3. and

Figure 4. Results show that the cumulative percentage of drug permeated for 8 hours. It was observed that higher for the Rvi-SLN gel formulation (76.53 ± 0.59%) permeate through nasal mucosa compared to 71.03± 0.43% for buccal mucosa.

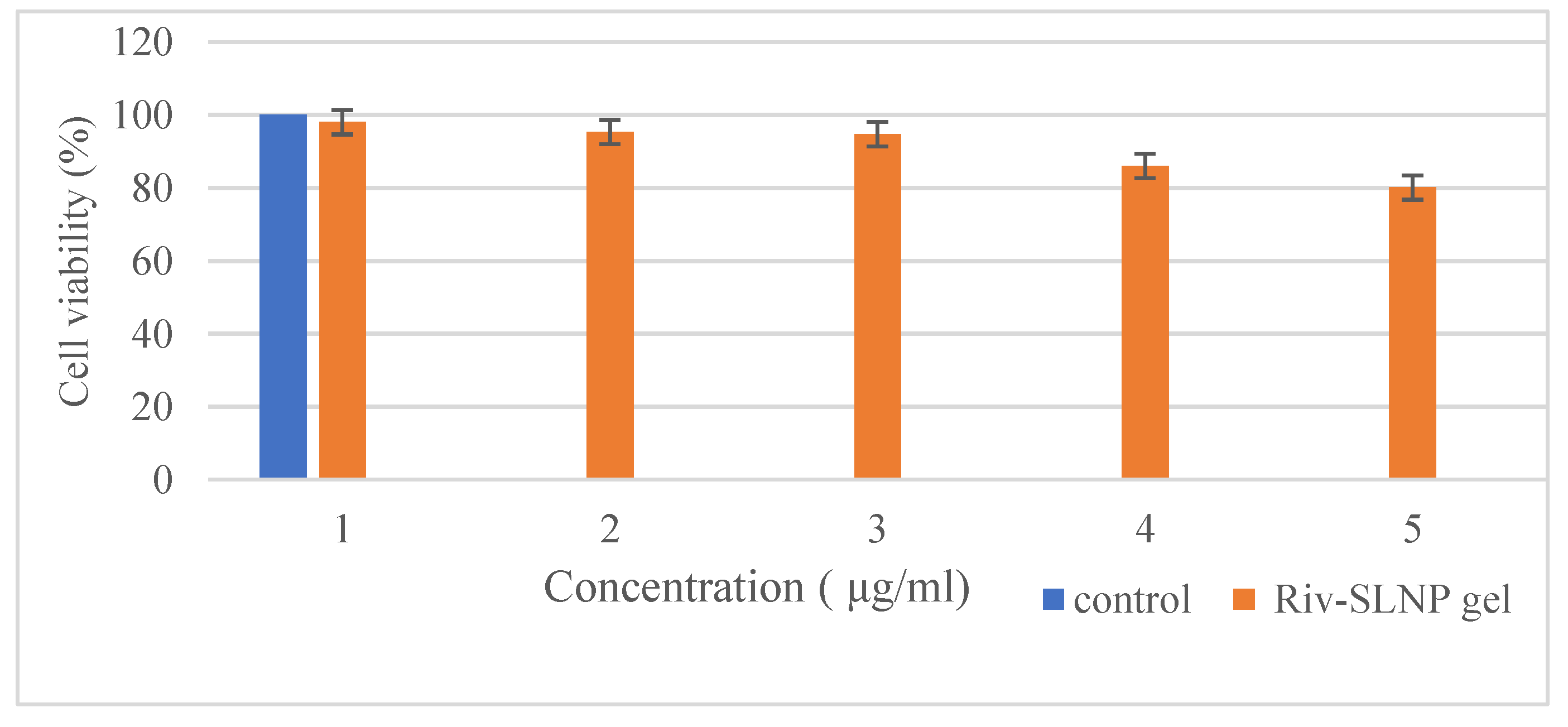

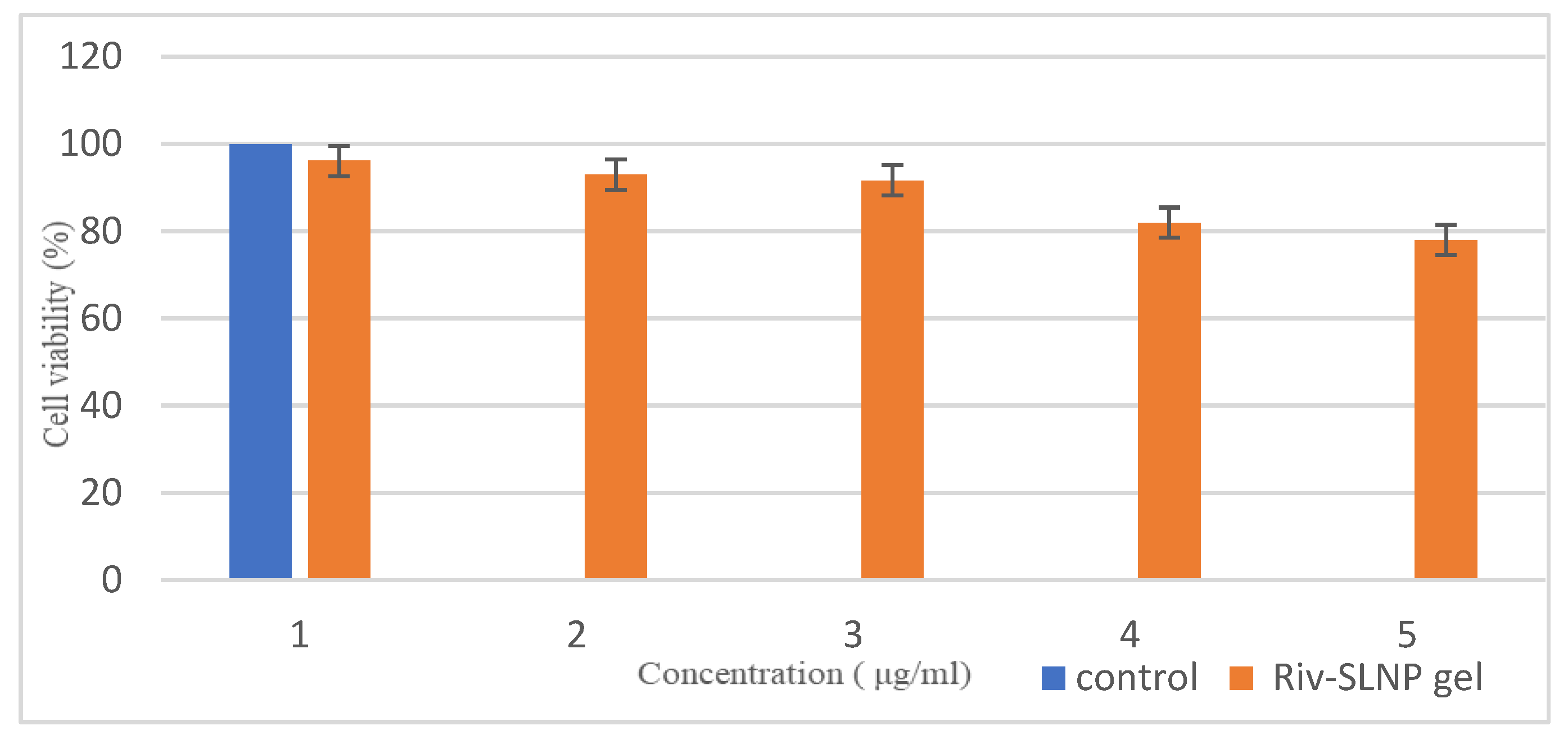

2.3.6. In Vitro Toxicity Using the MTT Assay

The cytotoxicity assay was performed to verify the safety of the prepared RIV-SLNPs gel on TR146 cells for buccal cell toxicity and RPMI 2650 cells for nasal cell toxicity.

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 illustrates that exposure to RIV-SLNPs mucoadhesive gel for 24 hours resulted in significant cell death in both PCS-200-014 cells (human oral epithelial cell line) and RPMI 2650, indicating nasal toxicity, in comparison to the blank gel (without drug) and RIV-SLNPs mucoadhesive gel at escalating dosages. The percentage of cell survival for the formulation above 80% at all tested concentrations, specifically for RPMI 2650 its 80.1% cell viability and for TR146 its 78% cell viability. Its indicates the appropriateness of these Riv-SLNP gel for biological applications and mitigates the potential of adverse effects owing to the biocompatibility of the Riv-SLNP gel.

2.3.7. Stability Studies

The

Table 4 presents the stability research conducted over three months, revealing no drastic or noteworthy changes over this period. No alterations in color, odor, or pH were observed; however, a slight shift in mucoadhesiveness was noted. The formulations produced demonstrated commendable stability and stability studies provide statistics that indicate a RIV-SLNPs relative stability throughout 3 months.

Table 4.

stability study for three months of RIV-SLNs.

Table 4.

stability study for three months of RIV-SLNs.

| Month |

Color/odor |

Mucoadhesive |

pH |

| 1st |

No change |

8889 dyne/cm2 |

6.2 |

| 2nd |

No change |

8885 dyne/cm2 |

6.3 |

| 3rd |

No change |

8884 dyne/cm2 |

6.3 |

3. Conclusions

This study successfully developed mucoadhesive gel using Moringa oleifera and encapsulate rivastigmine solid lipid nanoparticles which direct towards a novel approach to deliver the low bioavailable drug through buccal as well as nasal route. The formulation shows desirable physicochemical characteristics, including a particle size 222.2 nm with a PDI of 20.9 and -24.9 mV zeta potential indicating good colloidal stability. The in vitro drug release study of the formulation demonstrated a sustained release profile over 12 hours, with cumulative drug release reaching approximately 66.7%. It also has good permeability in both buccal and nasal mucosa with a suitable mucoadhesive property which enhance the retention time hence improving the delivery of drug. It also shows less cell viability which indicate a suitable candidate for drug delivery. The findings indicate that Riv-SLNPs possess significant potential as a safe and effective mucoadhesive delivery system for improving the bioavailability of Rivastigmine. However, additional in-vivo studies are necessary to ascertain the comprehensive toxicity and pharmacokinetic assessments to confirm its long-term safety and economic viability.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Moringa oleifera was collected from local vendors of Chennai, Tamil nadu.Rivestigmine,tartrate, steric acid and acetone was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. carbopol 934 is purchased from Analab Fine Chemicals Mumbai. All the other chemical used in this research are analytical grade.

4.2. Extraction of Mucilage

Moringa oleifera mucilage was extracted according to the methodology of L.A. Silva et al. (2022). Moringa was cleaned and dried. After completely drying it was crushed into powder. The powder was soaked in water for 24 hours. After it was filter with a muslin cloth, water and ethanol in a 1:4 ratio was added, and left overnight. The precipitate is gathered and dried. For later usage, the dried mucilage was kept in an airtight container in a desiccator [

10].

Ruthenium Red Test and Phytochemicals Screening of Mucilage

Few drops ruthenium red dye solution is added into the mucilage and confirm the presence of mucilage [

11]. After confirmation of the mucilage phytochemical screening of mucilage is done. Presence of alkaloids is check by Mayer-Wagner reagent test. It was done by dissolving the 10mg mucilage extract in 50 ml of water and filtering it. To 2ml of filtrate three drops of 1% HCl is added. Then, 6 mL of the Mayer-Wagner reagent was mixed with 1 mL of mixture and check the color of the precipitation. Test for flavonoids and glycosides is tested by dissolving 200 mg of the plant extract in 10 mL of ethanol, and the mixture was filtered to check for flavonoids and glycosides. Magnesium ribbon, concentrated HCl, and 2 ml of the filtrate were combined. The presence of flavonoids is indicated by the formation of a pink or red tint. When 0.5 mL of crude extract was mixed with 1 mL of distilled water and NaOH, a yellowish tint formed, signifying the presence of glycosides. For Saponins test 0.5 ml of the extract were mixed with 5 ml of distilled water and shaken. The presence of saponins was then confirmed by the foam formed. To check the presence of approximately 200 mg of tannin mucilage were cooked in 10 mL of distilled water, and 0.1% ferric chloride was added; the liquid was then examined for blue-black coloration.For phenols,1 mg of the extract was mixed with 1 ml of K₂Fe(CN₆) and three drops of FeCl₃. The existence of phenols was verified by the development of greenish-blue forms. In the terpenoids test,0.5 mg of mucilage is added in 2 mL of chloroform and 3 mL of sulfuric acid and observe the color change. To check the presence of carbohydrate molich test is performed. In this test is a general indicator for all carbohydratesMolisch’s reagent, a solution of α-naphthol in ethanol, is introduced to the sample, subsequently followed by the addition of strong sulfuric acid. A positive result is signified by the emergence of a purple ring at the interface of the two layers [

12].

4.3. Formulation of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles of Rivastigmine

Rivastigmine-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (Riv-SLNs) were prepared by hot-emulsification and probe sonication. Steric acid (350 mg) was chosen as lipid after visual solubility screening, Rivastigmine tartrate (10 mg) was dissolved in 2 mL acetone and added to molten lipid at 70 °C under stirring for 10 min. Stirring continued 30 min to evaporate acetone, then added dropwise into lipid phase over 20 min at 1,000 rpm to form a hot emulsion. The emulsion was homogenized 5 min at 10,000 rpm, then probe-sonicated 10 min (50% amplitude, 30 s on/10 s off) at 70 °C. The nano emulsion was cooled to room temperature under stirring (500 rpm, 30 min) to yield SLNs. Formulation was stored at 4 °C in amber vials. This method produces Riv-SLNs, suitable for incorporation into mucoadhesive gels for enhanced buccal or nasal delivery [

13].

4.3.1. Riv-SLNPs’ Particle Size and Shape

Using the Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS 90 (Mumbai, India), photon correlation spectroscopy was used to evaluate the generated Riv-SLNPs for zeta potential, particle size, and polydispersity index (PDI). Size and PDI measurements were made in disposable polystyrene cells at 25°C, and zeta potential analysis was performed using omega cuvettes. Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), morphological characterization was carried out by analyzing samples at different magnifications while maintaining an ideal accelerating voltage of 5 kV. The form and surface properties of the dispersed phase were assessed using automated image analysis techniques. These analyses offer important new information about the structural integrity of Riv-SLNPs [

14].

4.3.2. Assessment of Riv-SLNPs’ Percent Drug Entrapment Efficiency

To separate the supernatant and pellets, the formulations were put into vials and centrifuged for 25 minutes at 10,000 rpm using an ultracentrifuge (Remi Motors, Mumbai, India). After dissolving the pellets in methanol, HPLC was used to determine the drug’s concentration. The following formula was used to determine drug loading and entrapment efficiency [

15].

Entrapment efficacy = (total drug added)/ (entrapped drug in pellet) ×100

4.4. Formulation of Riv-SLNPs Mucoadhesive Gel

To formulate the mucoadhesive gel loaded with Riv-SLNPs 20mg of powdered polymer is used. In order to create the mucoadhesive gel, powdered polymer was dissolved in warm water and thoroughly hydrated while being stirred constantly for 2 hours. 10ml of Riv-SLNPs solution was then added along with 2 mg of hydrated Carbopol 934 and mixed under a propeller homogenizer at 400 rpm [

16].

4.4.1. The Physical Appearance, Homogeneity and pH Evaluation of Riv-SLNPs Gel

Visual inspection was used to verify the color, odor and homogeneity of the formed gel formulation. It was examined to check the appearance of any aggregates. The pH of the gel formulation was determined by using a digital pH meter [

17].

4.4.2. Mucoadhesive Strength

The mucoadhesion strength of the formulation was check using a modified weighing balance method. Fresh goat nasal mucosal tissue was procured from a local slaughterhouse. The right pan of the weight balance was designated for the addition of weight, and the left pan of the weight balance was designated for holding the slide (upper support). Below the upper support of the left panel, there was an glass slide. The mucosa was initially affixed to the upper support slide and hydrated with SNF at pH 5. The gel was positioned between the mucosa and permitted to adhere for few minutes. Subsequently, weight was incrementally applied until the mucosa became detached from one another. The mucoadhesive force, was calculated based on the minimum weight required to remove the mucosal tissue from the surface of each RIV-SLNs gel formulation [

18].

Mucoadhesive strength is calculated as

Mucoadhesive strength= (g)/a×m

Where m = weight required for detachment in grams,

g = acceleration due to gravity (980 cm/s2)

A = area of mucosa exposed.

4.4.3. Viscosity Riv-SLNPs

The viscosity of the prepared gel was measured using a Brookfield viscometer [

19].

4.4.4. Spreadability of Riv-SLNPs

The therapeutic efficacy of the formulations was also assessed based on their spreadability. The duration required for two slides to slide off the gel positioned between them, under a specified load, was articulated. It was calculated using the following formula:

S = M*L/t

where M denotes the weight attached to the upper slide, L denotes the length of the glass slide, and T denotes the time required to separate the slides [

20].

4.4.5. Drug Content of Riv-SLNPs

1 g of prepared gel was dissolved in 100 mL of pH 6.8 phosphate buffer. The solution was filtered and spectrophotometrically measured at 263 nm, utilizing phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) as a blank [

21].

4.4.6. In Vitro Drug Release Solid Lipid Nanoparticles

A Franz cell was utilized to conduct in vitro drug release tests. 2.5 mL of Riv-gel was administered into the donor chamber. The receptor chamber held 10 mL of PBS. The donor temperature was sustained at 34 ± 0.5°C using a water bath. The donor and receptor chambers were separated by a synthetic cellulose membrane, which had been pre-soaked in PBS at pH 5.5 for 6 hours. At designated, aliquots (400 μL) were withdrawn from the receptor chambers and replaced with an equal volume of fresh PBS (pH 5.5) to maintain sink conditions. The aliquots were analysed for drug concentration using an HPLC technique as previously described. The drug release mechanism was investigated by several mathematical models, including the Korsmeyer–Peppas model. After evaluating the model fit for linear regression, the chosen model was employed to illustrate the drug release mechanism. The results indicated a predominance of diffusion-controlled release, suggesting that the drug was primarily released through passive diffusion processes. Additionally, the data were further analysed to identify any potential influence of polymer characteristics on the release kinetics, providing insights into optimizing the formulation for enhanced therapeutic efficacy [

22].

4.4.7. Ex Vivo Permeation

Ex vivo permeation was investigated in sheep nasal mucosa and goat buccal mucosa. Ex vivo permeation was conducted with Franz-type diffusion cells. Nasal mucosa from healthy sheep, excised immediately post-slaughter, is utilized for ex vivo permeation investigations, while goat buccal mucosa is employed to assess buccal ex vivo permeation. The mucosa was preserved for the designated duration in a PBS (pH 7.4) solution supplemented with heparin. The integrity of the mucosa was assessed by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) before and after the in vitro permeation investigation with a voltmeter. Each mucosal portion was positioned in a Franz diffusion cell with the external face oriented upwards, situated between the donor and receptor compartments. The latter included a hydroalcoholic acceptor solution composed of PBS (pH 7.4) and ethanol in a 60:40 volume ratio. Throughout the tests, the receptor solution was continuously agitated by a tiny magnetic stirring bar and kept at a temperature of 37 ± 0.5°C. The Riv-SLNPs gel was applied to the mucosal surface of the donor compartment of Franz’s cells and sealed with parafilm. 1 ml of the sample was drawn from the receptor compartment at a designated time point and substituted with an equivalent volume of fresh medium. The samples were assessed for the percentage of drug penetration from the formulations using a UV spectrophotometer at 203 nm. The total quantity of medication permeated in mg/cm² was calculated and graphed over time. The steady-state drug flux (mg/hr/cm2) and the permeability coefficient was calculated [

23].

4.4.8. Determination of In Vitro Toxicity RIV-SLNPs Gel

This study evaluated the in vitro cytotoxicity of a blank gel (without drug) and RIV-SLNPs gel utilizing the MTT assay on TR146 cells (a human oral epithelial cell line) to ascertain buccal toxicity, and RPMI 2650 for nasal toxicity. RPMI-1640 medium use to culture the cell augmented with gentamicin (50 µg/mL) and inactivated fetal bovine serum (10%). The cells were sustained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cell lines were allocated in the media on 96-well tissue culture plates and subsequently incubated for 24 hours. The well plates were subsequently populated with the assessed formulations. After 24 hours of incubation, the MTT assay was employed to measure the quantity of viable cells. The media was replaced with 100 µL of fresh RPMI 1640 medium lacking phenol red. Subsequently, a 12 mM MTT stock solution (10 µL) was added to each well, including the untreated controls. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 4 hours. Following the removal of 85 µL of media from each well, 50 µL of DMSO was introduced, mixed, and incubated at 37 ◦C for 10 minutes. The viable cell counts were evaluated using a microplate reader to measure the optical density at 590 nm.

4.4.9. Stability Studies

The SLN formulation was injected into 10 mL ampoules and sealed for storage at room temperature (25°C) for a duration of three months. The organoleptic characteristics, mucoadhesive properties, and pH are assessed [

24].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D. and M.S.U.; methodology, B.D. and M.S.U.; investigation, B.D. and M.S.U.; resources, B.D. and M.S.U.; data curation, B.D. and M.S.U.; writing—original draft preparation, B.D.; writing—review and editing, B.D. and M.S.U.; visualization, B.D. and M.S.U.; supervision, M.S.U.; project administration, B.D. and M.S.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study can be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur and The Nanotechnology Research Centre (NRC) at SRM Institute of Science and Technology (SRMIST) for their valuable support and cooperation in facilitating this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Riv-SLNs |

Rivastigmine Solid lipid nanoparticles |

References

- Subramanian, P. Mucoadhesive Delivery System: A Smart Way to Improve Bioavailability of Nutraceuticals. Foods 2021, 10, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshidnejad-Tosaramandani, T.; Kashanian, S.; Karimi, I.; Schiöth, H.B. Synthesis of a Rivastigmine and Insulin Combinational Mucoadhesive Nanoparticle for Intranasal Delivery. Polymers 2024, 16, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandiah, N.; Pai, M.-C.; Senanarong, V.; Looi, I.; Ampil, E.; Park, K.W.; Karanam, A.K.; Christopher, S. Rivastigmine: the advantages of dual inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase and its role in subcortical vascular dementia and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Bansal, K.K.; Verma, A.; Yadav, N.; Thakur, S.; Sudhakar, K.; Rosenholm, J.M. Solid lipid nanoparticles: Emerging colloidal nano drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preparation and Optimization of In Situ Gel Loaded with Rosuvastatin-Ellagic Acid Nanotransfersomes to Enhance the Anti-Proliferative Activity [Internet]. pp. 1–2. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/12/3/263 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Shaikh, R.; Raj Singh, T.R.; Garland, M.J.; Woolfson, A.D.; Donnelly, R.F. Mucoadhesive drug delivery systems. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011, 3(1), 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuni, I.S.; Sufiawati, I.; Shafuria, A.; Nittayananta, W.; Levita, J. Formulation and Evaluation of Mucoadhesive Oral Care Gel Containing Kaempferia galanga Extract. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bácskay, I.; Arany, P.; Fehér, P.; Józsa, L.; Vasvári, G.; Nemes, D.; Pető, Á.; Kósa, D.; Haimhoffer, Á.; Ujhelyi, Z.; et al. Bioavailability Enhancement and Formulation Technologies of Oral Mucosal Dosage Forms: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khade, A.; Sabale, V.; Gadge, G.; Mahajan, U. AN OVERVIEW ON NATURAL POLYMER BASED MUCOADHESIVE BUCCAL FILMS FOR CONTROLLED DRUG DELIVERY. Indian Res. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 6, 1812–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Sinnecker, P.; Cavalari, A.; Sato, A.; Perrechil, F. Extraction of chia seed mucilage: Effect of ultrasound application. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandravanshi, K.; Sahu, M.; Sahu, R.; Sahu, N.; Lanjhiyana, S.; Chandy, A. Isolation of Mucilage from Herbal plants and its Evaluation as a Pharmaceutical Excipients. Res. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2022, 14, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubale, S.; Kebebe, D.; Zeynudin, A.; Abdissa, N.; Suleman, S. Phytochemical Screening and Antimicrobial Activity Evaluation of Selected Medicinal Plants in Ethiopia. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2023, 15, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Xie, W.; Yuan, L.; Abbas, M.; Chen, D.; Xie, S. Hot melt emulsification shear method for solid lipid-based suspension: from laboratory-scale to pilot-scale production. Anim. Dis. 2023, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetukuri, K.; Umashankar, M.S. Development and Optimization of Kunzea ericoides Nanoemulgel Using a Quality by Design Approach for Transdermal Anti-Inflammatory Therapy. Gels 2025, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamous, Y.F.; Altwaijry, N.A.; Saleem, M.T.S.; Alrayes, A.F.; Albishi, S.M.; Almeshari, M.A. Formulation and Characterization of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Loaded with Troxerutin. Processes 2023, 11, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, C.; Vibha; Pathak, D.; Kulshreshtha, M. Preparation and evaluation of different herbal gels synthesized from Chinese medicinal plants as an antimicrobial agents. Pharmacol. Res. - Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.; Vibha, M.Y.; Wal, P.; Ved, A.; Kumar, P.; et al. Formulation and evaluation of Chinese eucalyptus oil gel by using different gelling agents as an antimicrobial agent. Pharmacological Research - Modern Chinese Medicine 2023, 9, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, S.; Vinayagam, R.; Samivel, R. Thermosensitive Mucoadhesive Intranasal In Situ Gel of Risperidone for Nose-to-Brain Targeting: Physiochemical and Pharmacokinetics Study. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, D.; Bao, W.; Huang, S. Research and Application of Deep Profile Control Technology in Narrow Fluvial Sand Bodies. Processes 2025, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiehzadeh, F.; Mohebi, D.; Chavoshian, O.; Daneshmand, S. Formulation, Characterization, and Optimization of a Topical Gel Containing Tranexamic Acid to Prevent Superficial Bleeding: In Vivo and In Vitro Evaluations. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 20, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, C.; Carlucci, A.M.; Bregni, C. Study of In Vitro Drug Release and Percutaneous Absorption of Fluconazole from Topical Dosage Forms. Aaps Pharmscitech 2010, 11, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, P.; Bicker, J.; Carona, A.; Miranda, M.; Vitorino, C.; Doktorovová, S.; Fortuna, A. Amorphous nasal powder advanced performance: in vitro/ex vivo studies and correlation with in vivo pharmacokinetics. J. Pharm. Investig. 2023, 53, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preparation and Optimization of In Situ Gel Loaded with Rosuvastatin-Ellagic Acid Nanotransfersomes to Enhance the Anti-Proliferative Activity [Internet]. p. 7. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/12/3/263 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- González-González, O.; Ramirez, I.O.; Ramirez, B.I.; O’connell, P.; Ballesteros, M.P.; Torrado, J.J.; Serrano, D.R. Drug Stability: ICH versus Accelerated Predictive Stability Studies. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).