1. Introduction

Historically, cancer treatment strategies, encompassing surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy, have encountered considerable constraints, such as systemic toxicity, a lack of tumor specificity, and the emergence of drug resistance [

1,

2]. These limitations underscore the imperative to explore alternative strategies for cancer therapy.

Cancer therapy faces substantial challenges due to various characteristics of cancer cells, necessitating effective delivery systems [

3]. The intricacies of cancer, including heterogeneity, aggressive growth, and resistance to treatment, emphasize the indispensability of developing precise and efficient therapeutic strategies [

3,

4]. In this context, drug delivery systems play a pivotal role in enhancing therapeutic outcomes by facilitating targeted and controlled delivery of therapeutic agents to cancerous tissues while minimizing damage to healthy cells.

Targeted drug delivery systems, tailored to transport specific drugs with precision to target tissues or cells, play a pivotal role in various medical applications, offering more effective cancer treatment compared to traditional chemotherapy [

5,

6]. The use of an appropriate drug delivery system holds the promise of achieving cancer cell targeting effects. A crucial element in successful cancer treatment is the specific targeting of cancer cells [

7]. Moreover, drug delivery systems can maintain the stability of these drugs and safely transport them to the target tissues, ultimately leading to enhanced therapeutic effects and reduced side effects. In the absence of an appropriate delivery system, issues may arise, such as anticancer agents failing to precisely target the intended site, affecting surrounding normal cells, and causing severe side effects [

8,

9]. Additionally, anticancer drugs may degrade or be eliminated rapidly, limiting therapeutic efficacy and necessitating frequent administrations, increasing patient discomfort [

10]. Hence, the development and utilization of suitable drug delivery systems are critical in the quest for effective anticancer agents.

A promising approach involves the use of cancer cell-derived liposomes, exhibiting a homologous targeting effect [

11]. These liposomes, originating from cancer cell membranes, share surface characteristics with their parent cells, resulting in a higher affinity for interactions with the same or similar cancer cells [

12,

13]. This homologous targeting effect enhances the specificity and efficiency of drug delivery to cancerous tissues, potentially revolutionizing cancer therapy [

14].

Although numerous studies have explored the homologous targeting effect of cancer cell-derived liposomes, the precise factors driving this phenomenon remain unclear [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Notably, cadherin family proteins and integrins have been implicated as significant contributors [

19,

20,

21]. Consequently, we hypothesized that E-cadherin, known for its role in homophilic adhesion within cell-cell adhesion molecules, could be a key protein in mediating the homologous targeting effect of liposomes.

To test this hypothesis, we selected various types of cancer cells and assessed the expression patterns of cadherin family proteins, including E-cadherin. Subsequently, liposomes were derived from these cancer cells and used to treat all selected cancer cells to evaluate their binding affinity. Our findings revealed that E-cadherin can induce a more pronounced homologous effect compared to other cadherins. In other words, cancer cells expressing higher levels of E-cadherin demonstrated a greater specificity in binding with liposomes derived from those same cells.

This study sheds light on the significant impact of cell-cell adhesion molecules, particularly E-cadherin, on the homologous targeting effect of liposomes. Furthermore, through various characterization experiments, we optimized the physicochemical properties of liposomes, reaffirming their potential as effective drug delivery carriers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Cell Culture

HEPES buffer solution was purchased from Gibco Inc. (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Potassium Chloride was purchased from JENSEI Inc. (Seongnam, Korea). Saccharose was purchased from DUKSAN Inc. (Ansan, Korea). EGTA Buffer was purchased from Bio World Inc. (Ohio, USA). 0.5M EDTA, pH 8.0 was purchased from USB Inc. (Ohio, USA). Xpert protease Inhibitor Cocktail Solution was purchased from genDEPOT Inc. (Texas, USA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) purchased from Sigma Aldrich Inc. (Missouri, USA). Vybranttm DIO cell-labeling solution was purchased from Invitrogen Inc. (California, USA). Nucleporetm Track-Etch Membrane 0.4um and 0.1um, were purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences Inc. (Seoul, Korea). Avanti polar lipid Extruder kit and 10mm Filter supports was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabama, USA).

Rosewell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium, Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) high glucose and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from WelGENE Inc. (Daegu, South Korea). Penicillin-streptomycin (PS) was purchased from Hyclone-GE Healthcare Bio-Science (Utah, USA). H292, A549, MCF7 and MDAMB231 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA).

H292 andA549 were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PS. MCF7 and MDAMB231 were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PS. The cells were maintained in an incubation chamber with a humidified atmosphere at 37℃ and 5% CO2.

2.2. Characterization of Cells

Western blotting analysis was performed to investigate the composition of cell adhesion molecules. Briefly, the cell lysate was prepared using the RIPA lysis buffer, after which equal amounts of the proteins from different samples were quantified by BCA protein assay kit. All the samples with the sample buffer were heated to 90℃ for 10 min. Samples (30ug/well) were loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and run at 100V for 2h. The proteins on the gel were transferred to the PVDF membrane; then the membrane was blocked and incubated with the primary antibodies of anti-E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and b-actin at 4℃ overnight. The secondary antibodies, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG, were incubated with corresponding primary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h before imaging with an ECL Western Blotting Substrate.

2.3. Preparation of Memposomes

The cell membrane was isolated from source cells by subcellular (

Figure 1A). Briefly, the cells were grown in 150mm cell culture dishes to 90% confluency. To harvest the cell membrane, the cells were washed with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) solution twice. Then, we collected the cells and added hypotonic buffer (250nM sucrose, 20nM HEPES pH=7.4, 10nM KCl, 1.5nM MgCL2, 1nM EDTA pH=8.0, 1nM EGTA and 100ul EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail per 10ml). The entire solution was sonicated for 20 min and centrifuged at 720g for 5min, after which we collected the supernatant. Then, the supernatant was centrifuged at 4℃ and 10,000g for 10min. After discarding the pellet, the supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 100,000g for 1.5 h. The resulting pellet containing the plasma membrane material was resuspended with 2M CaCl2 in DPBS. We incubated the mixture at 37℃ for 1h. The mixture was centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min and washed with DPBS 3 times. The plasma membrane fraction was extruded through a polycarbonate membrane with pore sizes of 400nm, 200nm and 100nm to prepare cell membrane-derived liposomes, termed Memposomes (MPs).

2.4. Characterization of MPs

The particle sizes of MPs were measured at a concentration of 100ug/ml using a dynamic light scatter(DLS). H292 MPs, A549 MPs, MCF7 MPs and MDAMB231 MPs were suspended in 3ml DPBS and measurements were performed. The stability of MPs was measured using DLS. For storage stability, 300ug of MPs was suspended in 3ml in DPBS and stored at 4℃, and the size was measured once a day. Serum stability was suspended in 5% FBS at the same concentration and stored at 37℃, and the size was measured 5 times a day.

For the sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis, the cell lysate was prepared using the RIPA lysis buffer. All samples were heated to 90℃ for 10 min. Samples (30ug/well) with equal protein amounts were loaded onto the 10% SDS-PAGE gel and run at 100V for 2h. Subsequently, the gel was stained with Coomassie blue for 2 h, followed by washing with destaining solution overnight. Pictures were taken with a camera for subsequent imaging.

For Western blotting assay, the proteins on the gel were transferred to PVDF membrane, then the membrane was blocked and incubated with the primary antibodies of anti-Na/K ATPase, Histone H3 and b-actin at 4℃ overnight. The secondary antibodies including either horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG were incubated with corresponding primary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h, before imaging with an ECL Wetsern Blotting Substrate. The resulting gel was transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF) for western blot analysis. Membrane and Histone H3 for nucleosome at 4℃ overnight, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labeled (HRP) goat anti rabbit IgG cross-adsorbed secondary antibody (1:2000) for 2 h at 37℃. The improved PICO solution was applied to the membrane and signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) machine.

2.5. Cell Cytotoxicity

For in vitro cytotoxicity assay, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 X 103 cells per well and cultured for 18 h. Then H292 MP, A549 MP, MCF7 MP and MDAMB231 MP at various concentrations (i.e. 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50ug/ml) were added to the cells and the cells were incubated for 24 h. The cells without any particles were used as a control. Each group was repeated in six plicate. At the end of the incubation, 20ul(5mg/ml) Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 4 h. Finally, the solution was replaced by 150ul of the DMSO solution. The absorbance values of the cells per well were determined with a microplate reader at 450nm for analysing the cell viability.

2.6. Targeting Tendency Binding MPs to Cells

We conducted flow cytometry experiments to observe the cell-binding ability of MPs. MPs were first fluorescently labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). FITC-labeled MPs were characterized by measuring the absorbance at 494nm by UV spectroscopy. 1 X 106 live cells were dispersed in 200ul of FACS buffer (2% BSA/PBS), after which 200ul of FITC-labelled MPs (15ug/ml) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 4℃ for 30min. After washing with pre-cooled PBS, flow cytometry measurements were conducted; ten thousand events were collected for each measurement and analyzed by CytoExpert software (Beckman Coulter). The mean intensity of blank H292, A549, MCF7 and MDAMB231 was chosen as control. The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) was measured to quantify the amount of MPs bound to cells and to compare the binding abilities of different MPs.

2.7. Staining MP with DIO to Identify Targeting Tendency

For fluorescence images, the cancer cell membrane was labelled by a cell membrane green fluorescent probe DIO. The cell membrane was Suspend membrane at a density of 500ug/ml in DPBS and added 5ul of the DIO solution. The cell membrane solution with DIO was mixed well by gentle pipetting, followed by incubation for 10 minutes at 37℃. The DIO-cancer cell membrane was washed with PBS three times. For stabilization, the DIO-cancer cell membrane was incubated for 1 h and sonicated for 1 min, followed by extrusion for 15 circles through a 400um, 200um, and 100um polycarbonate porous membrane.

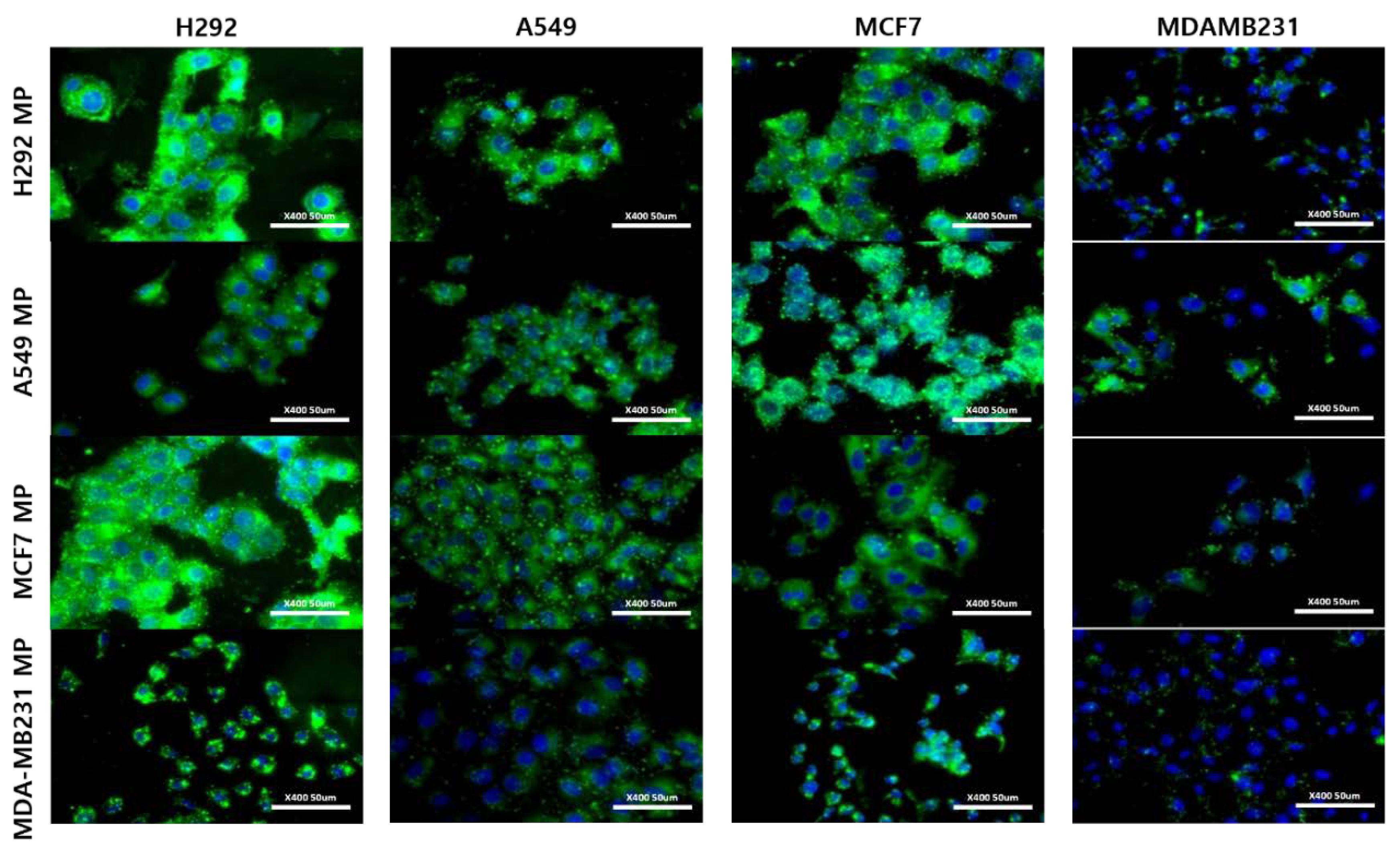

H292, A549, MCF7 and MDAMB231 cells were seeded in 24-well plate for fluorescence microscopy analysis. Then, the medium was replaced with the fresh medium contacting DIO-labelled MPs (15ug/ml) and stained for 2 h. After washed three times with PBS, the cells were fixed and imaged with a fluorescence microscope.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Cells

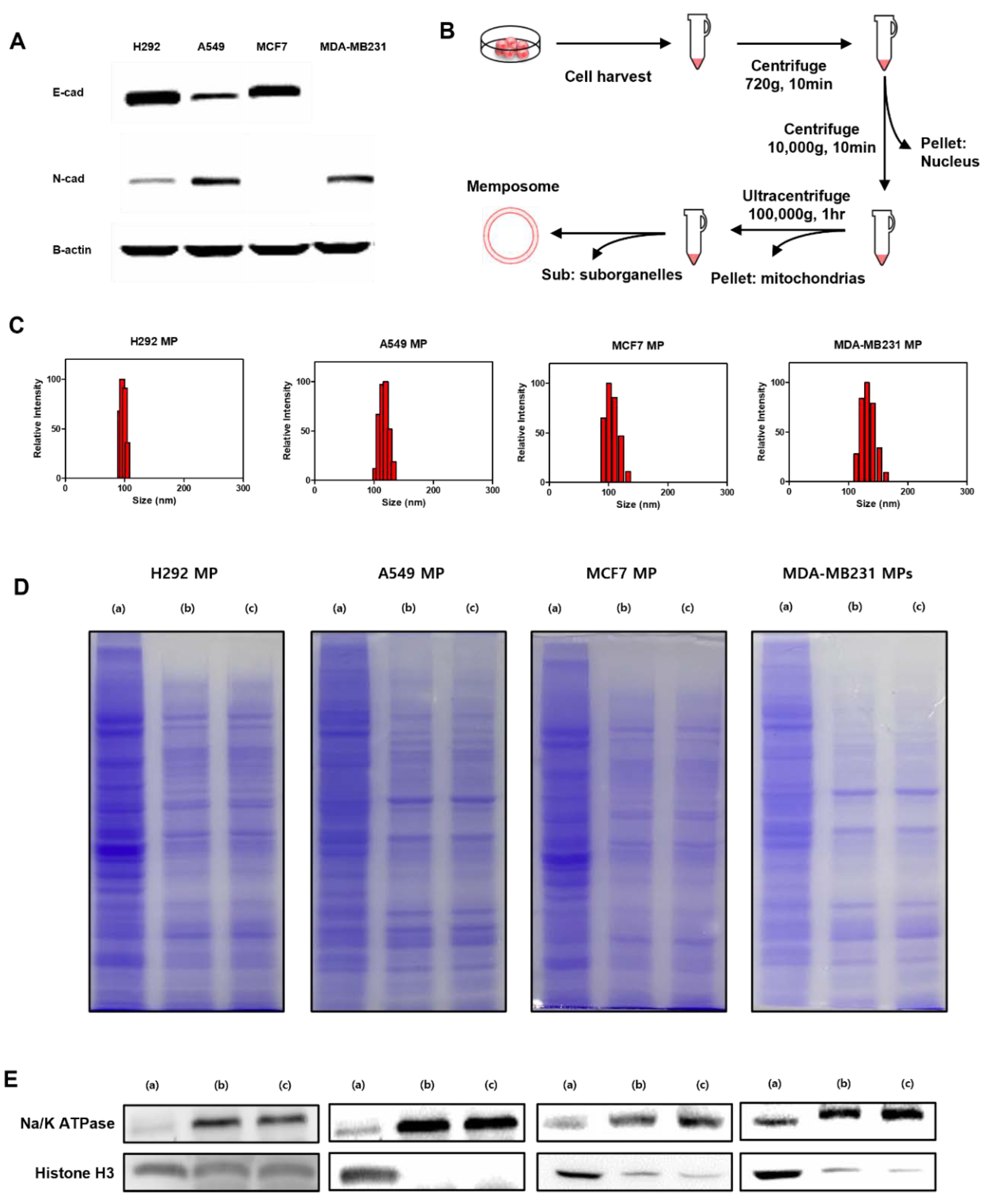

We conducted Western blot experiments to assess the protein profile of the cells that will be used for MP production. In the Western blot experiment (

Figure 1B), it was observed that H292 and MCF7 cells expressed significantly higher levels of E-cadherin compared to N-cadherin. On the other hand, A549 cells exhibited both E-cadherin and relatively higher expression of N-cadherin compared to other cell lines. Notably, MDA-MB231 cells lacked E-cadherin expression, which aligns with their known status as an E-cadherin negative control cell line. Based on the Western blot results, we classified H292 and MCF7 as having an abundance of E-cadherin, A549 as having a moderate level of E-cadherin, and MDA-MB231 as lacking E-cadherin. Subsequently, we proceeded with the experiments using these classifications.

3.2. Preparation and Characterization of MPs

To produce the MPs, we utilized the subcellular fractionation technique to isolate the plasma membrane fraction from the cell lysate. This method involves lysing the cells using a hypotonic buffer and then separation the cellular organelles through centrifugation. The obtained plasma membrane fraction contained membrane proteins. To convert this fraction into liposomes with a unilamellar structure, we subjected it to an extrusion process. Through the extrusion process, we were able to create uniform structures known as cell plasma membrane-derived liposomes or MPs. Using these cancer cell lines, we produced MPs and evaluated their physicochemical properties. To assess particle size of MPs, we measured the diameter of the MPs and observed that all four types of MPs had particles of approximately 100nm in size (

Figure 1C). The size and polydisperse index of MPs were summarised in

Table 1.

Additionally, to determine if proteins other than cell membrane proteins were effectively separated and if membrane proteins were well preserved, we conducted SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis (

Figure 1D and E). The results showed that the plasma membrane proteins were effectively separated from the cell lysate, and the MPs exhibited a similar protein composition with the plasma membrane fraction. This indicates that the MPs preserve the protein composition of the membrane fraction. Furthermore, we observed a significant reduction of the nuclear protein marker, histone H3, in both the membrane fraction and MPs compared to the whole cell lysate. However, the plasma membrane protein marker, Na/K ATPase, was detected in both the membrane fraction and MPs. This result indicated that other cellular organelles, apart from the plasma membrane, were effectively removed, and there was no significant loss of the plasma membrane fraction. Therefore, it was confirmed that the MPs were well composed of cell plasma membrane and membrane-associated proteins.

3.3. Stability of MPs

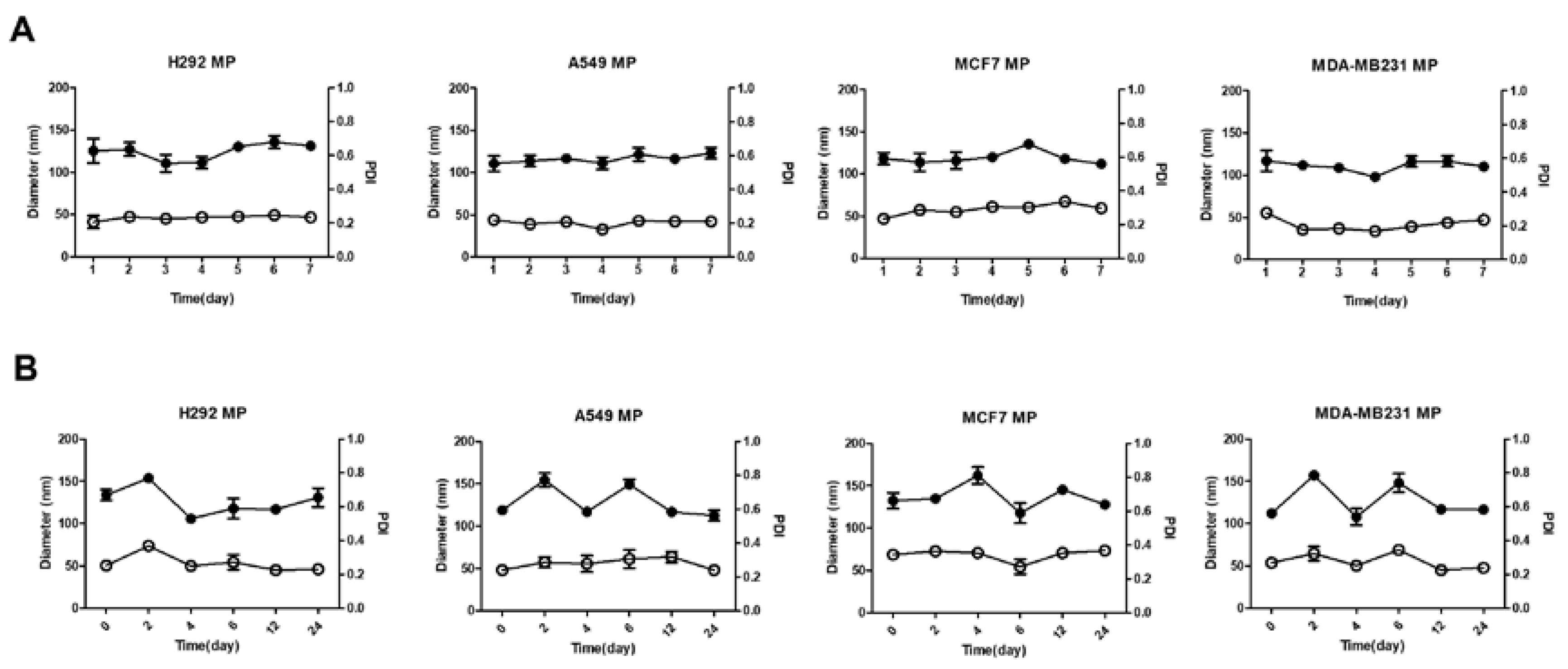

We conducted storage stability tests and serum stability tests to assess the stability of the MPs. In the storage stability test, the particle size of the MPs was measured at 24-hour intervals for one week. Throughout the entire week, the polydispersity index (PDI) value remained consistently around 0.2 to 0.3, indicating good stability over time (

Figure 2A). The researchers concluded that the particle size of the MPs remained stable over the course of the week, without any noticeable aggregation or significant changes. Additionally, the researchers tested the stability of the MPs in the presence of serum. They dispersed the MPs in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing serum and measured the particle size at regular intervals over a 24-hour period. The results showed that the particle size remained stable throughout the day, indicating that the MPs maintained their size stability even when exposed to serum (

Figure 2B). However, compared to the storage stability test, the particle size and PDI value exhibited relatively less stability, suggesting some degree of variability. Nevertheless, the researchers noted that noticeable aggregation of the MPs did not occur, indicating that they maintained their overall size stability in the presence of serum over the course of 24 hours. Overall, based on the experiments conducted, the researchers found that the MPs demonstrated good stability in terms of size and aggregation both during storage over a one-week period and when exposed to serum over a 24-hour period.

3.4. Cytotoxicity of MPs

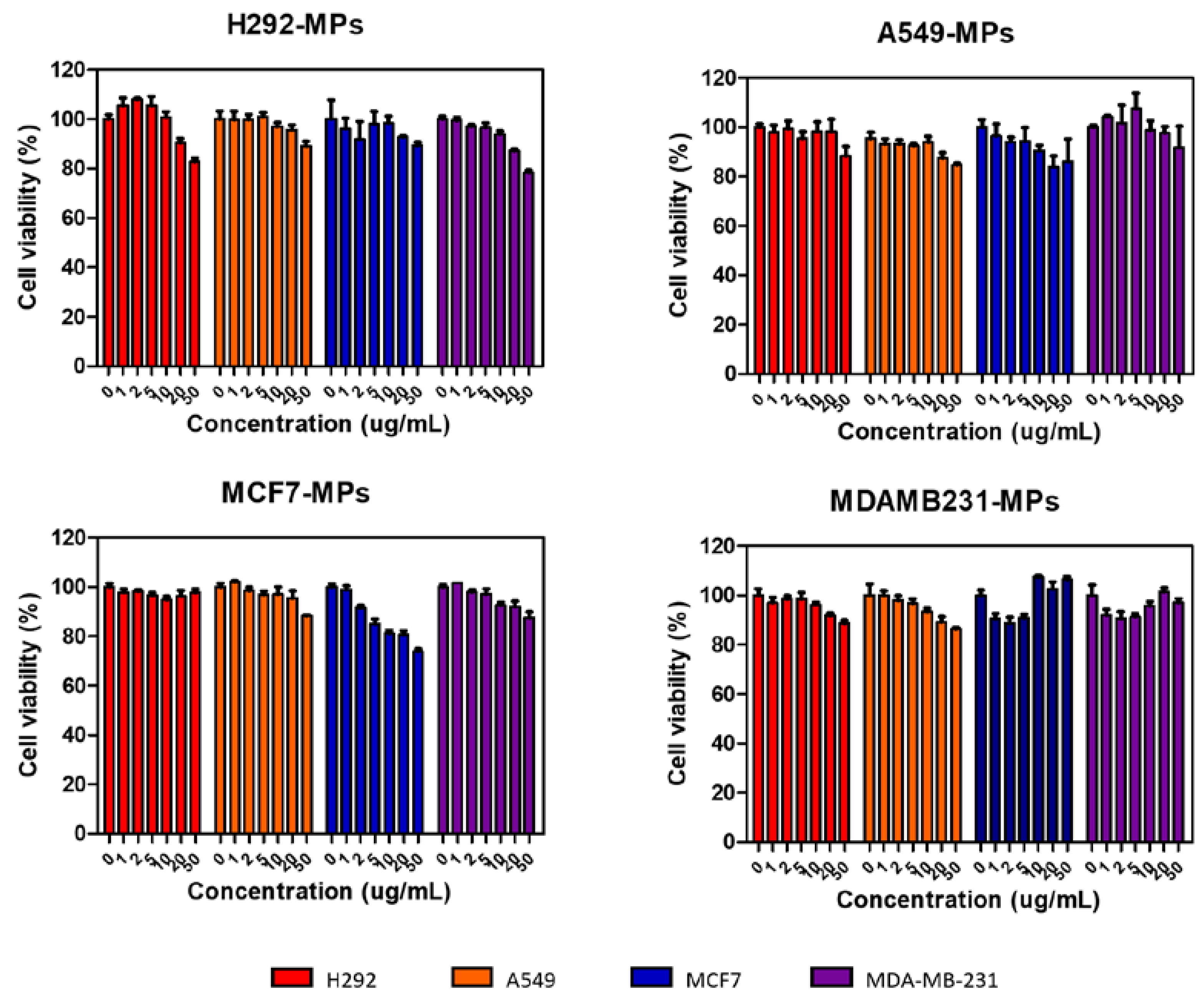

In the given study, we performed a cell viability assay to assess the cytotoxicity of different types of MPs were derived from the cell membranes of specific cells. The purpose was to investigate their potential for cell binding while ensuring that they do not induce cytotoxicity. To conduct the assay, we treated each type of MP with a predetermined concentration and exposed them to four different cell lines. After a 24-hour incubation period, they examined the cell viability to determine if the MPs had any detrimental effects on the cells (

Figure 3). The results of the assay revealed that even at high concentrations of all types of MPs, the cell viability remained above 80%. This finding is significant as it indicates that the MPs derived from cancer cell plasma membranes do not induce cytotoxicity. Moreover, not only did they not show cytotoxic effects on the source cells of the MPs but also on heterotypic cancer cell lines, suggesting their biocompatibility. This observation of high cell viability implies that the MPs possess favorable biocompatibility characteristics, making them suitable candidates for further investigation in biomedical applications. The lack of cytotoxicity effects broadens their potential utility, as it suggests they could potentially be employed without causing harm to cells in various therapeutic or diagnostic contexts.

3.5. Targeting Ability of MPs

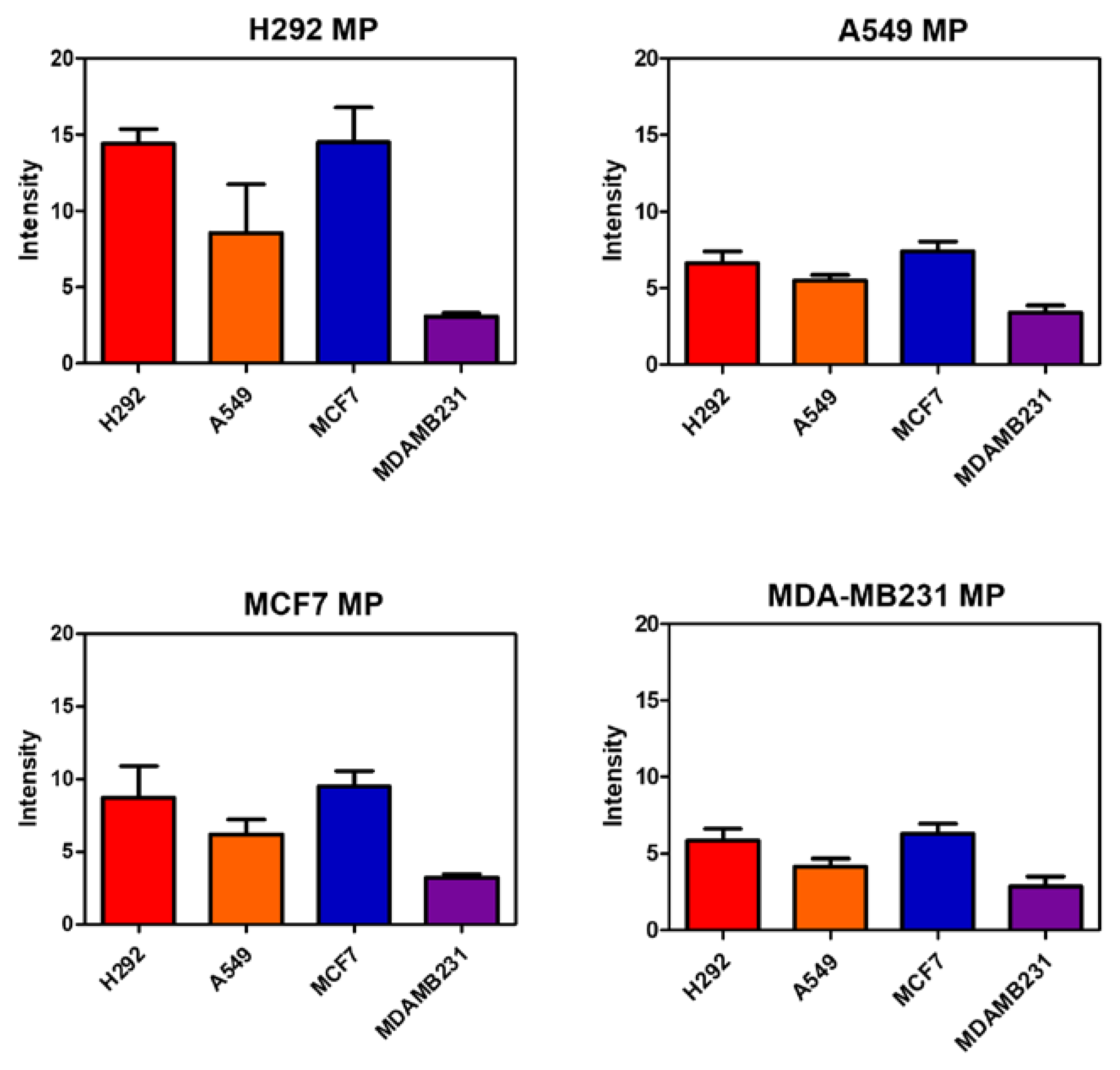

In the provided text excerpt, we conducted a series of experiments to assess the composition, stability, and safety of microparticles (MPs) for potential utilization as drug delivery carriers. To delve further into the cell binding characteristics of the synthesized MPs, the researchers conducted flow cytometry experiments with a specific emphasis on the quantification of E-cadherin, a cell adhesion molecule. In the flow cytometry experiment, the researchers labeled the MPs with FITC fluorescent dye, resulting in MP-FITC. Subsequently, they exposed four distinct cell lines to MP-FITC and subjected them to agitation at 4°C for 30 minutes. Following this treatment, the measurement of bound MP-FITC on the cells allowed the determination of the extent to which the MPs had successfully adhered to the cells. The outcomes of the experiment unveiled a discernible correlation between the quantity of E-cadherin and the binding affinity of the MPs to the cells (

Figure 4). Notably, the H292 cell line, characterized by the highest E-cadherin levels, exhibited a heightened propensity for binding the MPs compared to the other cell lines. This observation implies that cells expressing higher levels of E-cadherin possess an increased inclination to bind to the same type of MPs. Conversely, the MDA-MB231 cell line, lacking E-cadherin expression (E-cadherin negative), demonstrated a diminished affinity for binding the MPs relative to the other cell lines. This finding aligns with the established understanding that E-cadherin plays a pivotal role in facilitating cell-cell adhesion and binding interactions. Therefore, the researchers verified the composition, stability, and safety of the synthesized MPs, and the results from the flow cytometry experiments underscored the impact of E-cadherin on the cell binding propensity of these particles. These insights contribute significantly to our comprehension of the factors influencing the interaction between MPs and cells, particularly in the context of drug delivery applications.

In addition to conducting flow cytometry analysis, we employed fluorescent imaging to visually validate the obtained results. For this experiment, we employed a lipophilic fluorescent dye known as DIO (DIO-MP) to labelled MPs. Subsequently, the cells were treated with the labeled MPs, and fluorescent images were captured using the appropriate wavelength. The results obtained from the fluorescent imaging validated the trends observed in the flow cytometry data (

Figure 5). Specifically, the H292 cell line demonstrated a robust binding affinity with nearly all types of MPs, surpassing the other cell lines in terms of binding strength. In contrast, the MDA-MB231 cell line exhibited considerably lower levels of binding with the MPs compared to the rest of the cell lines. The A549 and MCF7 cell lines displayed intermediate levels of MP binding. Thus, by integrating fluorescent imaging with flow cytometry, we were able to visually confirm the binding characteristics of the labeled MPs and gain further insights into the differential binding patterns exhibited by various cell lines.

4. Conclusions

Through the conducted experiments, it became evident that the homologous targeting effect of memposomes, which are liposome-like structures created from cell membranes, varies based on the characteristics of the source cell membrane. Notably, when memposomes were derived from cancer cell membranes characterized by high E-cadherin expression, they exhibited a remarkable homologous targeting effect. Conversely, memposomes originating from cancer cell membranes lacking E-cadherin displayed a less pronounced homologous targeting effect. This observation implies that memposomes effectively mimic the functionality of cancer cell membranes. By considering the protein profile expressed on cell membranes, we have the capability to design memposomes with diverse functionalities. The roles of membrane proteins vary depending on the cell type, and a comprehensive understanding of these roles could pave the way for targeted therapies utilizing memposomes. This research underscores the utility of memposomes as effective drug delivery vehicles and establishes their physicochemical stability. We confirmed that cell membrane proteins are well-preserved in memposomes, and effective separation is achieved from proteins originating from other cellular organelles. Furthermore, the stable maintenance of particle size for over a week was observed. Consequently, memposomes exhibit both safety and stability as drug delivery vehicles. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the potential of memposomes for targeted drug delivery applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and J.H.K.; methodology, H.C., H.K., S.L. and J.H.K.; validation, H.C., H.K., H.J.L., Y.C. and H.S.; formal analysis, H.C., H.K. and H.J.L.; investigation, H.C., H.K., Y.C. and H.S.; data curation, H.C., H.K., H.J.L., Y.C. and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C. and H.K.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and J.H.K.; visualization, H.C., H.K. and H.J.L.; supervision, S.L. and J.H.K.; project administration, S.L. and J.H.K.; funding acquisition, S.L. and J.H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (21153MFDS601) from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2024, the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2022R1F1A1076216, and Korea Drug Development Fund funded by Ministry of Science and ICT, Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy, and Ministry of Health and Welfare (RS-2022-DD128953).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bayat Mokhtari, R.; Homayouni, T.S.; Baluch, N.; Morgatskaya, E.; Kumar, S.; Das, B.; Yeger, H. Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38022–38043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debela, D.T.; Muzazu, S.G.; Heraro, K.D.; Ndalama, M.T.; Mesele, B.W.; Haile, D.C.; Kitui, S.K.; Manyazewal, T. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE Open Med 2021, 9, 20503121211034366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Allela, O.Q.B.; Pecho, R.D.C.; Jayasankar, N.; Rao, D.P.; Thamaraikani, T.; Vasanthan, M.; Viktor, P.; Lakshmaiya, N.; et al. Progressing nanotechnology to improve targeted cancer treatment: overcoming hurdles in its clinical implementation. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Wang, D.C.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, M.; Zhang, M.; Shen, Q.; Wang, X. Roles of tumor heterogeneity in the development of drug resistance: A call for precision therapy. Semin Cancer Biol 2017, 42, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L.F.; Campos, E.V.R.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.D.P.; Acosta-Torres, L.S.; Diaz-Torres, L.A.; Grillo, R.; Swamy, M.K.; Sharma, S.; et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology 2018, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shao, A. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy and Its Role in Overcoming Drug Resistance. Front Mol Biosci 2020, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Yang, L.; Chen, G.; Xu, F.; Yang, F.; Yu, H.; Li, L.; Dong, X.; Han, J.; Cao, C.; et al. A Review on Drug Delivery System for Tumor Therapy. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 735446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyanani, V.; Haley, J.C.; Goswami, R. Challenges of Current Anticancer Treatment Approaches with Focus on Liposomal Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Li, Y.; Xiong, L.; Wang, W.; Wu, M.; Yuan, T.; Yang, W.; Tian, C.; Miao, Z.; Wang, T.; et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, S.; Mahanta, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Maiti, P. Controlled drug delivery vehicles for cancer treatment and their performance. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2018, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Sun, X.; Wu, B.; Shang, Y.; Huang, X.; Dong, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Gui, R.; Li, J. Construction of homologous cancer cell membrane camouflage in a nano-drug delivery system for the treatment of lymphoma. J Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, P.; Luo, Z.; Zheng, M.; Tian, H.; Gong, P.; Gao, G.; Pan, H.; Liu, L.; Ma, A.; et al. Cancer Cell Membrane-Biomimetic Nanoparticles for Homologous-Targeting Dual-Modal Imaging and Photothermal Therapy. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 10049–10057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, R.H.; Hu, C.M.; Luk, B.T.; Gao, W.; Copp, J.A.; Tai, Y.; O'Connor, D.E.; Zhang, L. Cancer cell membrane-coated nanoparticles for anticancer vaccination and drug delivery. Nano Lett 2014, 14, 2181–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Deng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, P.; Fu, X.; Lei, X.; Qin, A.; Yu, X. Homotypic Targeting Delivery of siRNA with Artificial Cancer Cells. Adv Healthc Mater 2020, 9, e1900772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Miao, C.; Tang, L.; Liu, Y.; Ni, P.; Gong, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, F.; Feng, S. Homotypic Cancer Cell Membranes Camouflaged Nanoparticles for Targeting Drug Delivery and Enhanced Chemo-Photothermal Therapy of Glioma. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, X.; Pan, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, X.; Huang, H.; Wu, Z.; Qi, X. 4T1 cell membrane fragment reunited PAMAM polymer units disguised as tumor cell clusters for tumor homotypic targeting and anti-metastasis treatment. Biomater Sci 2021, 9, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapeinos, C.; Tomatis, F.; Battaglini, M.; Larranaga, A.; Marino, A.; Telleria, I.A.; Angelakeris, M.; Debellis, D.; Drago, F.; Brero, F.; et al. Cell Membrane-Coated Magnetic Nanocubes with a Homotypic Targeting Ability Increase Intracellular Temperature due to ROS Scavenging and Act as a Versatile Theranostic System for Glioblastoma Multiforme. Adv Healthc Mater 2019, 8, e1900612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Zheng, D.W.; Zhang, M.K.; Yu, W.Y.; Qiu, W.X.; Hu, J.J.; Feng, J.; Zhang, X.Z. Preferential Cancer Cell Self-Recognition and Tumor Self-Targeting by Coating Nanoparticles with Homotypic Cancer Cell Membranes. Nano Lett 2016, 16, 5895–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, T.D.; Nelson, W.J. Cadherin adhesion: mechanisms and molecular interactions. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2004, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, C.Y.; Chai, J.Y.; Tang, T.F.; Wong, W.F.; Sethi, G.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Chong, P.P.; Looi, C.Y. The E-Cadherin and N-Cadherin Switch in Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition: Signaling, Therapeutic Implications, and Challenges. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, R.B.; Qiao, R.; Keren, R.; Badano, I.; Suyama, K. Cadherin switch in tumor progression. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004, 1014, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).