1. Introduction

In recent decades, the study of extracellular vesicles (EVs) as highly specific mediators of intercellular communication over short and long distances has developed rapidly, involving almost all biomedical fields and emphasizing their crucial role in various physiological and pathological conditions [

1]. EVs are micro- and nanoparticles surrounded by a lipid bilayer and contain a variety of biological molecules, from nucleic acids to small metabolites. EVs are produced by virtually all cells, which use them to “package” various cargoes and release them into the extracellular space. EVs have intrinsic targeting characteristics, natural composition, resistance to harsh environmental conditions, reduced clearance, stability in the bloodstream and the ability to cross biological barriers [

2].

Currently, EVs are categorized into three main groups based on different mechanisms of biogenesis: exosomes (Ex), which arise from multivesicular bodies (MVBs), microvesicles (MVs), which bud directly from the plasma membrane, and apoptotic bodies (ABs), which originate from dying cells. EVs exert their functions by releasing cargo into target cells through membrane fusion or by interacting with surface receptors on target cells [

3].

The increasing interest in EVs is due to their potential in the biomedical field. Many studies have shown that they can be used as diagnostic markers for various diseases, from cancer to neurological disorders [

4,

5]. In addition, their potential use as nanocarriers for the release of therapeutic molecules is generating great excitement in the research field of drug delivery, which is rapidly moving from the micro- to the nanoscale [

6]. By engineering suitable parental cells, it may be possible to transform them into natural bioreactors and produce EVs with known content and well-defined functions [

7]. To this end, several research groups have explored strategies to engineer the surface of EVs with ligands that target the tissue and modify their cargo. EVs used as carriers of small drugs showed high biocompatibility and a good pharmacokinetic profile in vivo [

8]. More recently, EVs have also been investigated as carriers for large biomolecules such as proteins and RNA [

9,

10]. Protein-containing EVs could be very interesting as protein-based therapies have an increasing impact on healthcare. However, their instability, short half-life and immunogenicity often limit their safety and efficacy. To overcome these limitations, nanoscale delivery methods are currently being investigated.

In recent decades, only a few reports have been published on the successful loading of functional proteins. This suggests that the mechanisms regulating the transport and loading of biomolecules into EVs are still relatively unexplored and that new methods for tailoring EVs cargo to the target tissue need to be investigated. ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) was the main system investigated [

11]. Alternative mechanisms were explored by Trajkovic and colleagues, who described ESCRT-independent, ceramide-mediated biogenesis of EVs [

12]. Van Niel and colleagues described a different pathway in which CD63 regulates EV biogenesis without the involvement of ESCRT [

13].

Recently, the number of research groups investigating the biogenesis, transport and internalization of EVs by cell engineering has greatly increased. Most of them use CD63 tagged with different reporter systems such as GFP [

14], HaloTag [

15] and pHluorin [

16].

The choice of the right donor cell is another key element in the development of genetically engineered EVs to be used as biocarriers. Ideally, the selected cell type should produce EVs without immunostimulatory activity that are stable in the bloodstream and can preferentially reach the target. The use of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) seems attractive and feasible. MSCs are a population of stromal cells whose therapeutic potential is being extensively studied in both human and veterinary medicine [

17]. MSCs can be isolated from various tissues and biological fluids. Adipose tissue is a strategic source of MSCs as it is abundant, easy to obtain and rich in MSCs. Originally classified as “stem cells”, they are now considered “medical signaling cells”, as their therapeutic effect is achieved through the paracrine secretion of bioactive principles rather than through their engraftment and differentiation properties [

18]. The paracrine activity of MSCs is related to the release of soluble factors and EVs [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In addition, many reports have shown that MSCs can be safely used in animal models and clinical trials as well as in allogeneic recipients [

23].

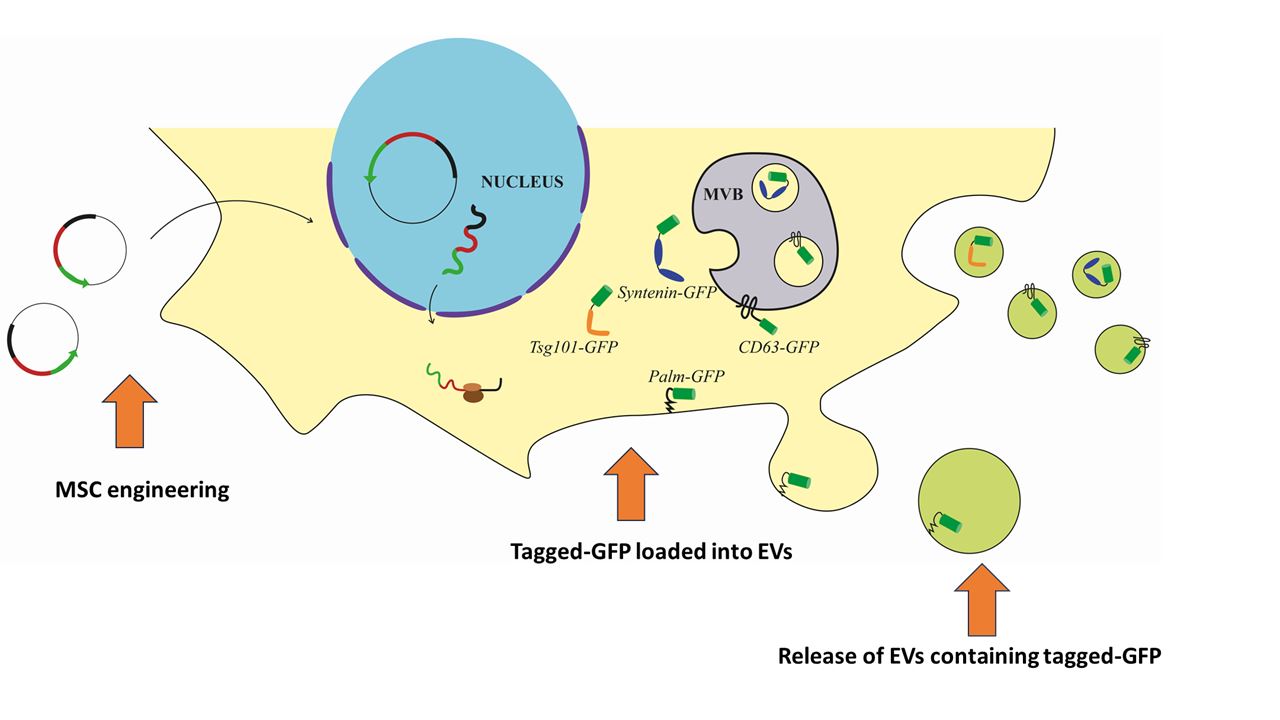

The aim of this study was to engineer canine adipose-derived MSCs (c-Ad-MSCs) to release EVs carrying a specific protein in order to investigate the transport of molecules in EVs and provide the basis for possible future functionalization with proteins of interest. Specifically, we induced overexpression of the reporter protein GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) tagged with molecules that concentrate in EVs based on specific motifs or localization signals, some of which are associated with the lipid membrane and others with intra-luminal localization. The selected tags were CD63, syntenin-1, TSG101 and the palmitoylation signal of Lck. CD63 proved to be a highly efficient tag with a robust loading and delivery capability. This suggests its potential use in engineering approaches aimed at loading therapeutic biomolecules into c-Ad-MSC-EVs.

2. Materials and Methods

Isolation, Culture and Characterization of Canine MSC

c-Ad-MSCs were isolated from the subcutaneous adipose tissue of a 5-year-old dog that had died because of trauma and was referred to the OVUD (Veterinary University Hospital) of the University of Perugia. The adipose tissue was removed within 2 hours of death with the consent of the owners, who made the cadaver available for teaching and research purposes. The tissue sample was washed three times with DPBS (Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline) supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and amphotericin B (2.5 μg/ml) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The tissue was then minced with sterile scissors and digested for 70 minutes in a 0.075% collagenase I solution (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ) at 37°C in a water bath with gentle agitation. After digestion, collagenase activity was blocked by addition of DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The stromal vascular fraction (SVF) obtained by collagenase digestion was centrifuged at 600 g for 10 minutes to remove the fat fraction and collagenase solution and seeded in cell culture flasks containing DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. After 48 hours, the unattached material was removed. The medium was changed every 2-3 days, and the cells were passed when they had reached 80-90% confluence. Passage 3 c-Ad-MSCs were characterized using the International Society for Cell and Gene Therapy (ISCT) criteria to assess the ability to differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts and chondroblasts and to confirm the expression of characteristic c-Ad-MSC surface markers. For trilineage differentiation, cells were seeded in 24-well plates, stimulated with differentiation media for 3 weeks and then stained with Oil-O-Red, Alizarin or Alcian Blue as described by Neupane and colleagues [

24]. The immunophenotype of c-Ad MSCs was determined by FACS analysis (for CD14, CD29, CD44, CD45, CD90 and MHCII as described by Ivanovska and colleagues [

25].

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from 3rd passage c-Ad MSCs with Trizol and purified using the PureLink MiniKit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated RNA was quantified with NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The first strand of cDNA was then obtained by reverse transcription of total RNA (1μg per sample) using SuperScript Vilo IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in a final volume of 20 ml (thermal cycling conditions: 25 °C for 10 min, 42 °C for 60 min, 85 °C for 5 min).

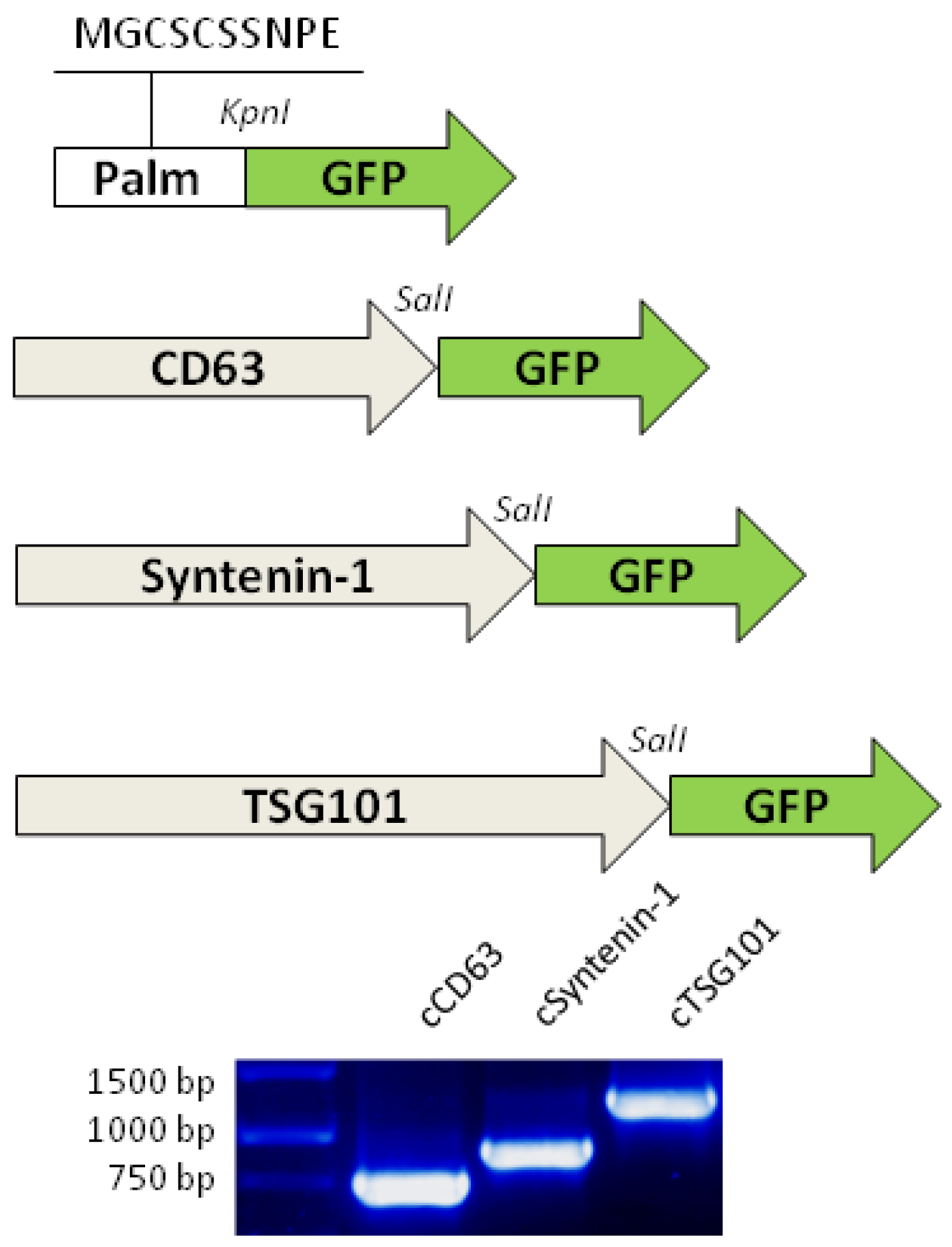

The sequences encoding CD63, TSG101 and syntenin-1 were amplified by PCR with appropriate primers (

Table 2) containing restriction sites for subsequent ligation. A highly purified TaqQ5 enzyme was used for amplification (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA).

Table 1.

List of genes encoding for selected tags and localization site in EVs.

Table 1.

List of genes encoding for selected tags and localization site in EVs.

| Protein name |

GeneID |

Protein size |

EVs localization |

Specific EVs motif/domain |

| Lck (Tyrosine-protein kinase Lck) |

478151 |

509 aa

58 kDa

|

membrane anchor |

Palmitoylation signal in N-term (MGCSCSSNPE) |

| CD63 |

474391 |

238 aa

25,6 kDa

|

transmembrane |

Unknown |

| SDCBP (Syntenin-1) |

482977 |

298 aa

32 kDa

|

luminal |

(LYPXnL) |

| TSG101 (Tumor susceptibility gene 101) |

485406 |

391 aa

44 kDa

|

luminal |

(PTAP) |

Plasmids

PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in TAE 1.2% agarose gel. The amplicons of our interest, corresponding to the expected size, were then excised from the gel and purified using the Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (ZymoResearch, Irvine, CA). The purified PCR products were digested with HindIII/SalI (for CD63 and TSG101) and KpnI/SalI (for syntenin-1) enzymes and ligated into pBlueScript II SK with T4 ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Chemically competent XL1-Blue strains were transformed with the ligation products, and Sanger sequencing was performed on both strands of the purified plasmids to confirm the identity of the amplified sequences, as described by Hedayati et al. [

26].

The CD63, TSG101 and syntenin-1 sequences were subcloned into pTag-GFP2-N (Evrogen, Moskva, Russian Federation) by removing the stop codon and linking to the GFP coding sequence in the SalI restriction site in frame.

Table 2.

List of primers and oligos.

Table 2.

List of primers and oligos.

| Gene of interest |

Sequence expected size (bp) |

Primer sequences |

Thermal conditions |

| CD63 |

740 |

Forward: 5’-GGCAAGCTTCCATGGCGGTGGAAGG-3’

Reverse: 5’-GAGAGTCGACCCCTACATGACTTCATAGCCAC-3’

|

98° x 10’’

65° x 15’’

72° x 1’ |

| TSG101 |

1255 |

Forward: 5’-CCCTAAGCTTGCGGTGACTGGAGTGG-3’

Reverse: 5’-GCTTTAAGTCGACCTCAATCTCCAGCTGAT-3’

|

98° x 10’’

57° x 20’’

72° x 1’10’’ |

| SDCBP (Syntenin-1) |

1021 |

Forward: 5’-AAAAGGTACCTCTGCAAAAATGTCTCTCTACCCA-3’

Reverse: 5’-AAAAGTCGACTGGCTCCTGGAAAGCTTCA-3’

|

98° x 10’’

60° x 15’’

72° x 1’ |

| Gene of interest |

Sequence expected size (bp) |

Primer/oligo sequences for GFP fusion |

Thermal conditions |

| CD63 |

735 |

Forward: 5’-GGCAAGCTTCCATGGCGGTGGAAGG-3’

Reverse: 5’-AAAACGTCGACATGACTTCATAGCC-3’

|

98° x 10’’

65° x 15’’

72° x 1’ |

| TSG101 |

1217 |

Forward: 5’-CCCTAAGCTTGCGGTGACTGGAGTGG-3’

Reverse: 5’-AAAACTCGAGTAGAGGTCACTGAGACC-3’

|

98° x 10’’

57° x 20’’

72° x 1’10’’ |

| SDCBP (Syntenin-1) |

921 |

Forward: 5’-AAAAGTCGACTCTGCAAAAATGTCTCTCTACCC-3’

Reverse: 5’-AAAACGTCGACACCTCAGGAATGGTGTG-3’

|

98° x 10’’

60° x 15’’

72° x 1’ |

| Palm sequence |

45-37 |

Sense: 5’-AGCTTGCCATGGGCTGTAGCTGCAGCTCAAACCCTGAAGCGGTAC-3’

Antisense: 5’-CGCTTCAGGGTTTGAGCTGCAGCTACAGCCCATGGCA-3’

|

N.A. (denaturation at 80°C and slow annealing in cooling water) |

MSC Transfection and Isolation of EVs

c-Ad-MSCs at passage 3 were seeded at 5*103 cells/cm2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml). After 24 hours, the cells were transfected with the desired plasmid using Lipofectamine Stem Transfection Reagent (1:4 ratio, with 250 ng DNA/cm2) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Transfection was performed in the absence of FBS, which was added 12 hours later to restore the normal concentration of 10%. Cells were incubated for 24-48 hours before subsequent analysis.

To isolate EVs, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were washed with DPBS to remove serum proteins. The medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml) and incubated for 48 hours. The conditioned medium was harvested and centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 minutes at 4° C to remove detached cells and cell debris. The supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 minutes at 4°C; the EVs pellet was resuspended in 100 ml DPBS. The protein content was quantified using the Bradford assay.

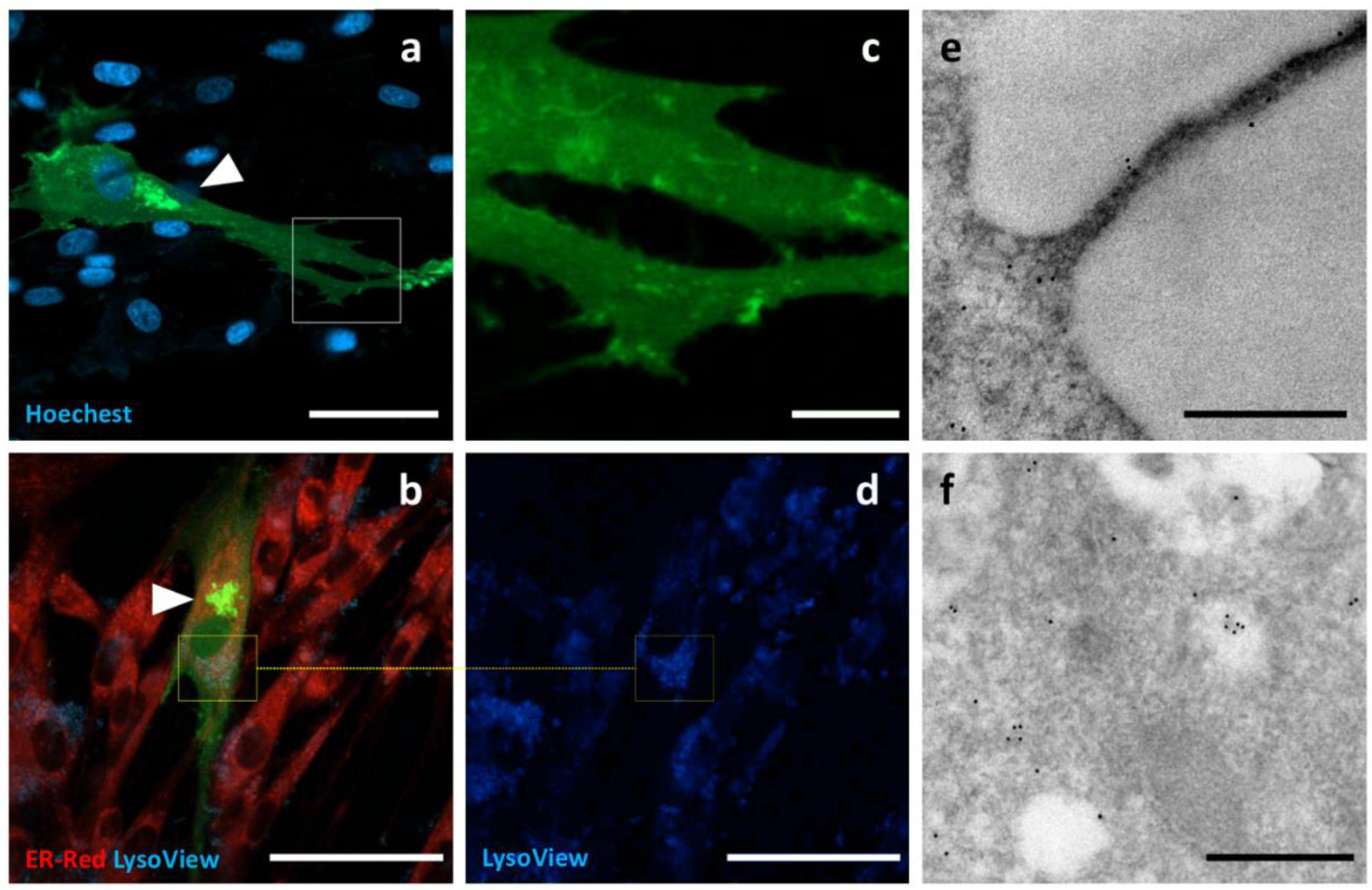

Confocal Microscopy of Living Cells

t-GFP were seeded in 96-well black/clear plates (Corning, NY) and transfected as previously described to study their localization in c-Ad-MSCs. After 48 hours, the cells were stained with fluorescent probes to better localize the different intracellular compartments: ER-ID Red Assay (Enzo Life Science, Farmingdale, NY) for the endoplasmic reticulum, Hoechst 33342 for the nuclei, LysoView 405 (Biotium, Fremont, CA) for lysosomes as well as for other acidic compartments in the cell, including early and late endosomes, MitoView 650 (Biotium, Fremont, CA) for mitochondria. Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope with a Plan Apochromat 63x/1.40 Oil DIC M27 objective. The excitation wavelength was 488nm for GFP, 353nm for Hoechest and LysoView, 592nm for the ER-Red stainer and 650 nm for Mitoview. The original images are 1024x1024 pixels in size, the pixel size is 187x187 nm.

Immunoelectron Microscopy of Transfected c-Ad-MSCs

Transfected c-Ad MSCs were fixed in Karnovsky modified solution (4% paraformaldehyde, 0.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer 0.1M pH 7.4). Cells were dehydrated to 70% in a graded ethanol series and embedded in LR White resin (Agar scientific, Essex, UK). Ultrathin sections mounted on Formvar-coated nickel grids (Agar scientific, Essex, UK) were incubated in a blocking solution (2% BSA and 2% normal goat serum in DPBS) for 60 minutes. The anti-GFP antibody (Life Technologies Carlsbad, CA) was incubated overnight at room temperature in a blocking solution. A 12 nm gold-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Baltimora, MD) was used to detect the primary antibody. The grids were contrasted for 2 minutes in 2% uranyl acetate solution and observed using a Philips EM208 provided with a digital camera.

Western Blotting

The expression and localization of t-GFP was detected by Western blotting in cell lysates and isolated EVs. Transfected cells and EVs were lysed in RIPA buffer and 10 μg of total proteins were treated in Laemmli buffer at 95°C for 5 minutes and separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide, 120 V for 2 hours). The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked in 5% non-fat milk for 60 minutes. The primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. Incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies was carried out for 60 minutes at room temperature. The immune complexes were detected with ImageQuant LAS 500 (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA) after the addition of the ECL solution. The area density of the bands was analyzed using Chemidoc Imagequant TL software. Antibody list: anti-GFP diluted 1:7500 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), anti-TSG 101 diluted 1:500 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-Alix diluted 1:500 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-bTubulin diluted 1:10000 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-mitofilin diluted 1:10 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

3. Results

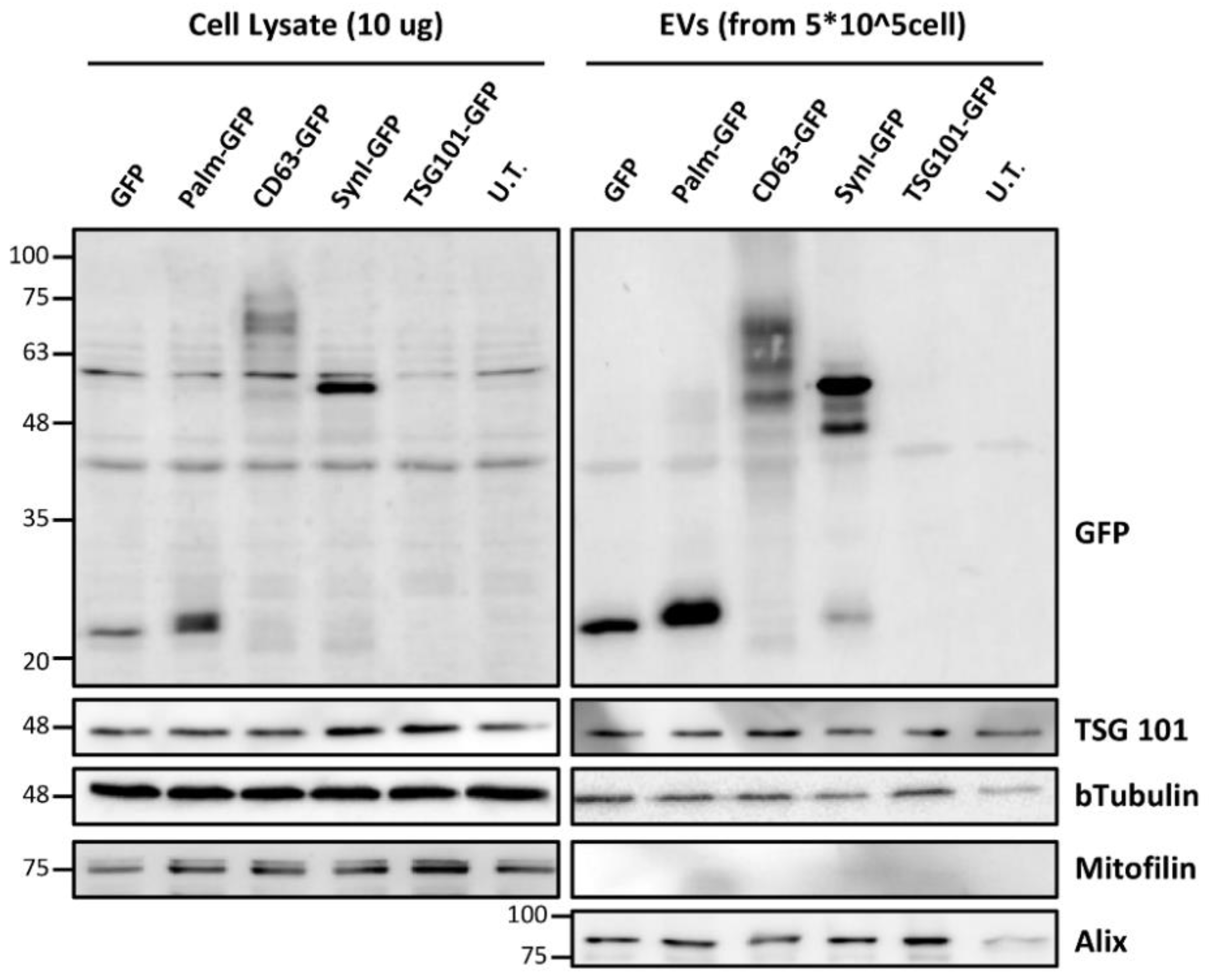

Transfected Canine MSCs Express GFP

Untagged GFP and palmitoylated GFP showed the expected molecular weight (27 kDa and 29-30 kDa, respectively). CD63-GFP showed several bands with different molecular weights. The theoretical size of the chimeric protein is 54.8 kDa (516 amino acids), but due to the abundant ubiquitylation of CD63 the molecular weight increases. A small amount of untagged GFP was detected in CD63-GFP-transfected cells. Syn-GFP (syntenin-1-GFP) showed a strong signal at an expected weight of 60 kDa (550 amino acids); as with CD63-GFP, a small amount of untagged GFP was also present. Western blotting on cell lysates confirmed the low expression of TSG101-GFP in c-Ad-MSCs.

Figure 2.

Western blotting for the detection of GFP-tagged proteins in c-Ad-MSC lysate and c-Ad-MSC-derived EVs. The anti-GFP immunoblotting assay in the upper panels shows the different molecular sizes of the chimeric proteins. Control markers for TSG101 and Alix (positive markers for EVs), mitofilin (negative marker for EVs) and b-tubulin (as loading control) are shown in the lower panels (Palm-GFP: Palmitoylated GFP, Syn-GFP: Syntenin-1-GFP, UT: not transfected, Mw: molecular weight).

Figure 2.

Western blotting for the detection of GFP-tagged proteins in c-Ad-MSC lysate and c-Ad-MSC-derived EVs. The anti-GFP immunoblotting assay in the upper panels shows the different molecular sizes of the chimeric proteins. Control markers for TSG101 and Alix (positive markers for EVs), mitofilin (negative marker for EVs) and b-tubulin (as loading control) are shown in the lower panels (Palm-GFP: Palmitoylated GFP, Syn-GFP: Syntenin-1-GFP, UT: not transfected, Mw: molecular weight).

EVs from Transfected MSCs Contain GFP-Tagged Proteins

Western blotting on EVs showed the presence of tagged (tGFP) and untagged GFP. As in cell lysates, GFP and palmitoylated GFP showed a single band with the expected weight. For CD63-GFP, there were three discrete high molecular weight signals compatible with different ubiquitylated forms, while a weak signal of the expected weight (55 kDa) was seen for the ubiquitylated form and another (27 kDa) for untagged GFP. Syn-GFP showed a strong signal with the expected molecular weight. In addition, several bands were detected that were brighter than the full-length bands. They could indicate the expression of clivated proteins.

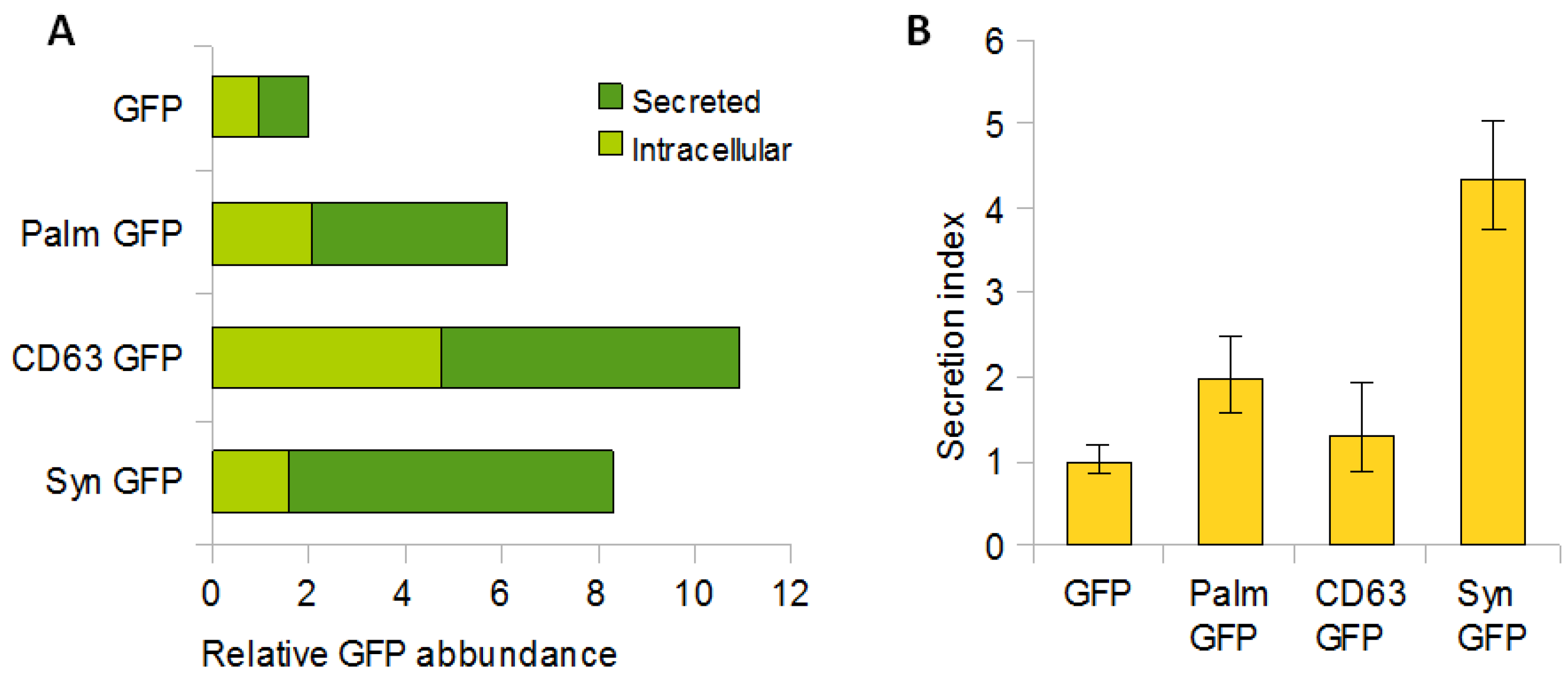

Palmitoylation Signal, CD63 and Syntenin-1 Confer Different Loading Efficiencies in EVs

The loading efficiency of the reporter protein in EVs was estimated from the ratio of GFP-EVs and GFP cell lysates. The total amount of differentially labelled tGFP, both intracellular and secreted, was higher than that of untagged tGFP. Palm GFP was 3-fold higher, CD63 GFP 5-fold higher and Syn GFP 4-fold higher than untagged GFP (

Figure 3A). The ratio between intracellular tGFP and tGFP released from EVs showed a different efficiency depending on the tags. Palm-GFP was released 2-fold, Syn-GFP 4.5-fold and CD63-GFP 1.5-fold compared to untagged GFP (

Figure 3B). These data confirm that a protein of interest enters EVs more efficiently when tagged with EVs-related proteins.

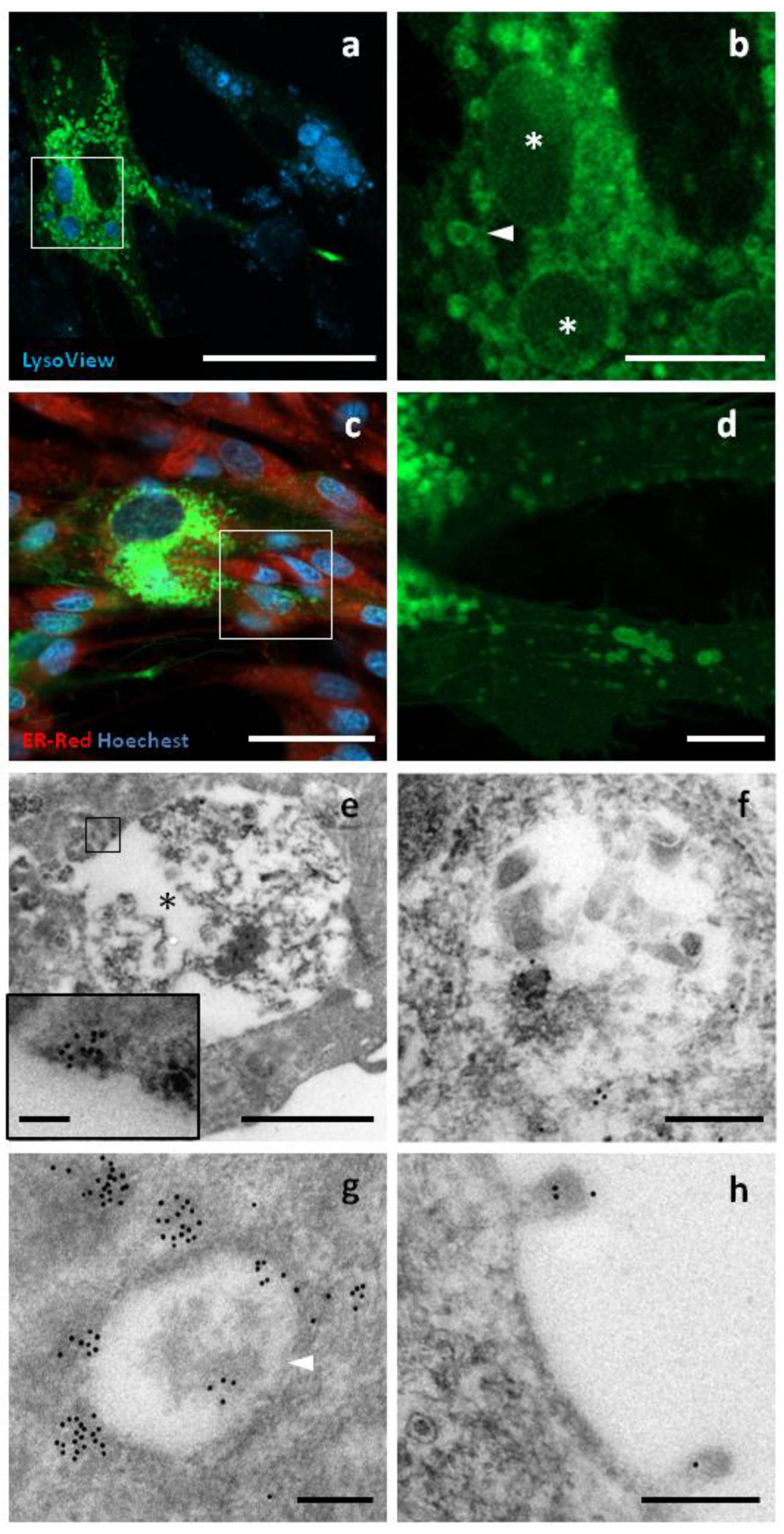

tGFP Shows Different Intracellular Localizations

CD63 belongs to the tetraspanin family, a group of transmembrane proteins with four alpha helices and two extracellular domains. GFP was fused to the C-terminus of canine CD63, a region with cytoplasmic topology. CD63 is usually associated to the cell surface, and to lysosomes, endosomes, multivesicular bodies and EVs membrane. Using confocal microscopy, strong fluorescence was observed in intracellular compartments between 300 nm and 5 mm in size. The largest compartments were mainly positive at the periphery and were strongly stained by LysoView, A weak signal was detected at the level of the cell membrane, where surface structures such as nanotubes and budding vesicles were observed. GFP signal was not detected in the nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum. Similar substructures were observed also by TEM, with the largest having a diameter of up to 5 μm and being heterogeneous in terms of electron density and structure. The immunopositivity for GFP was found in the peripheral regions of these organelles. The small structures were between 300 and 800 nm in size and had a more homogeneous structure and electron density. GFP localization appeared to be focally distributed around and within these compartments (

Figure 4).

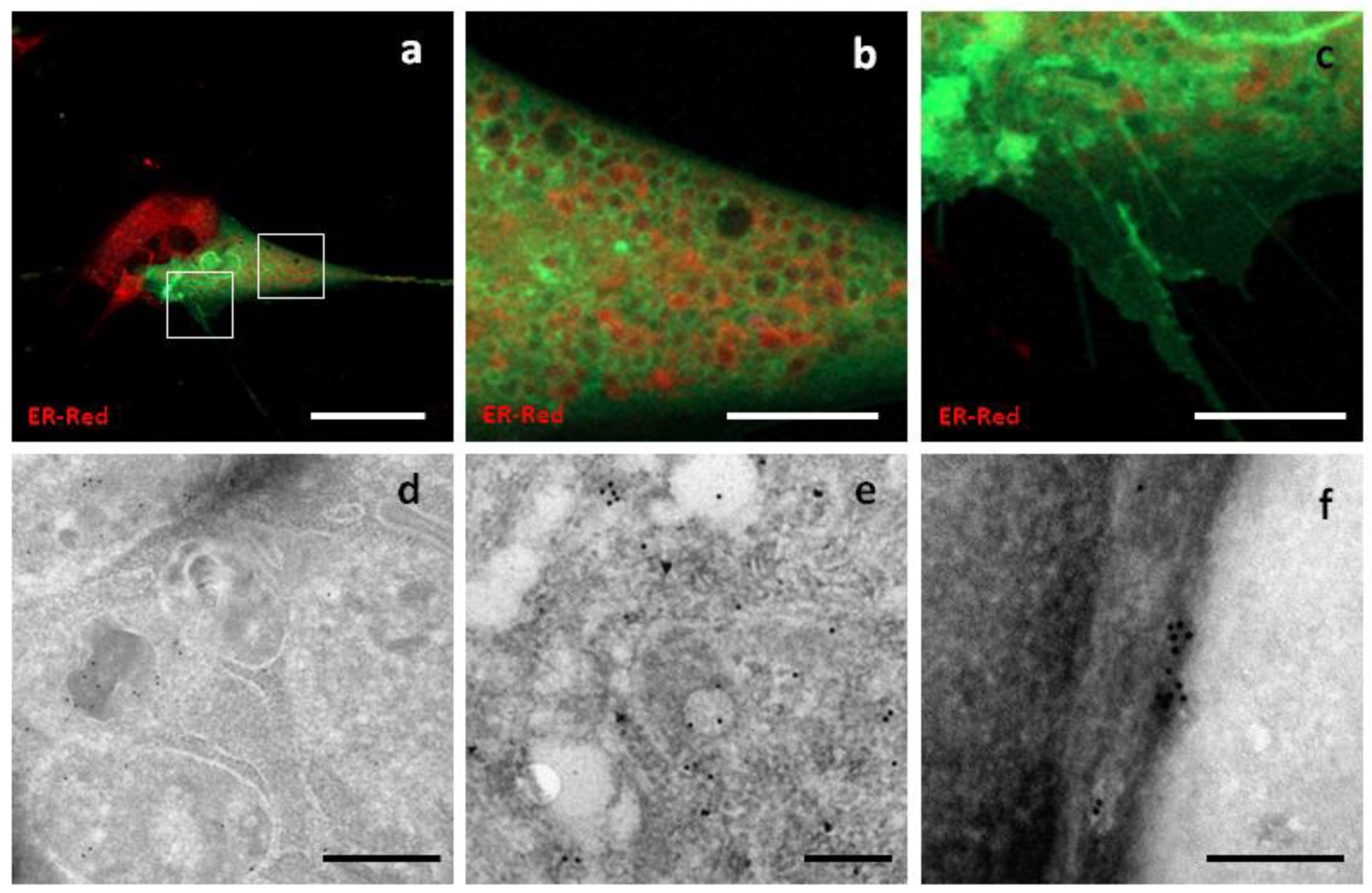

Syntenin-1, or SDBCP, is a cytoplasmic multifunctional adaptor involved in many biological processes. The sequence encoding canine syntenin-1 was cloned into a GFP-encoding vector to obtain GFP fused to the C-terminus of syntenin-1. A highly variable distribution of fluorescence was observed, with diffuse cytoplasmic localization being the most common. In addition, Syn-GFP was observed in the nucleus, at the level of the nuclear membrane, around some intracellular compartments resembling endosomal elements, on the plasma membrane and on surface structures resembling nanotubes and nascent microvesicles (

Figure 5).

Tumour Susceptibility Gene 101 (TSG101) is a cytoplasmic protein involved in the ESCRT complex, the molecular machinery responsible for the biogenesis of EVs. GFP was fused to the C-terminus of TSG101 cloned from canine cDNA. Only a few c-Ad-MSCs showed fluorescence signals. The intracellular localization of TSG101-GFP was focal, in the form of discrete small spots distributed throughout the cell. Due to the low number of positive cells, it was not possible to perform immunogold labelling (

Figure 6).

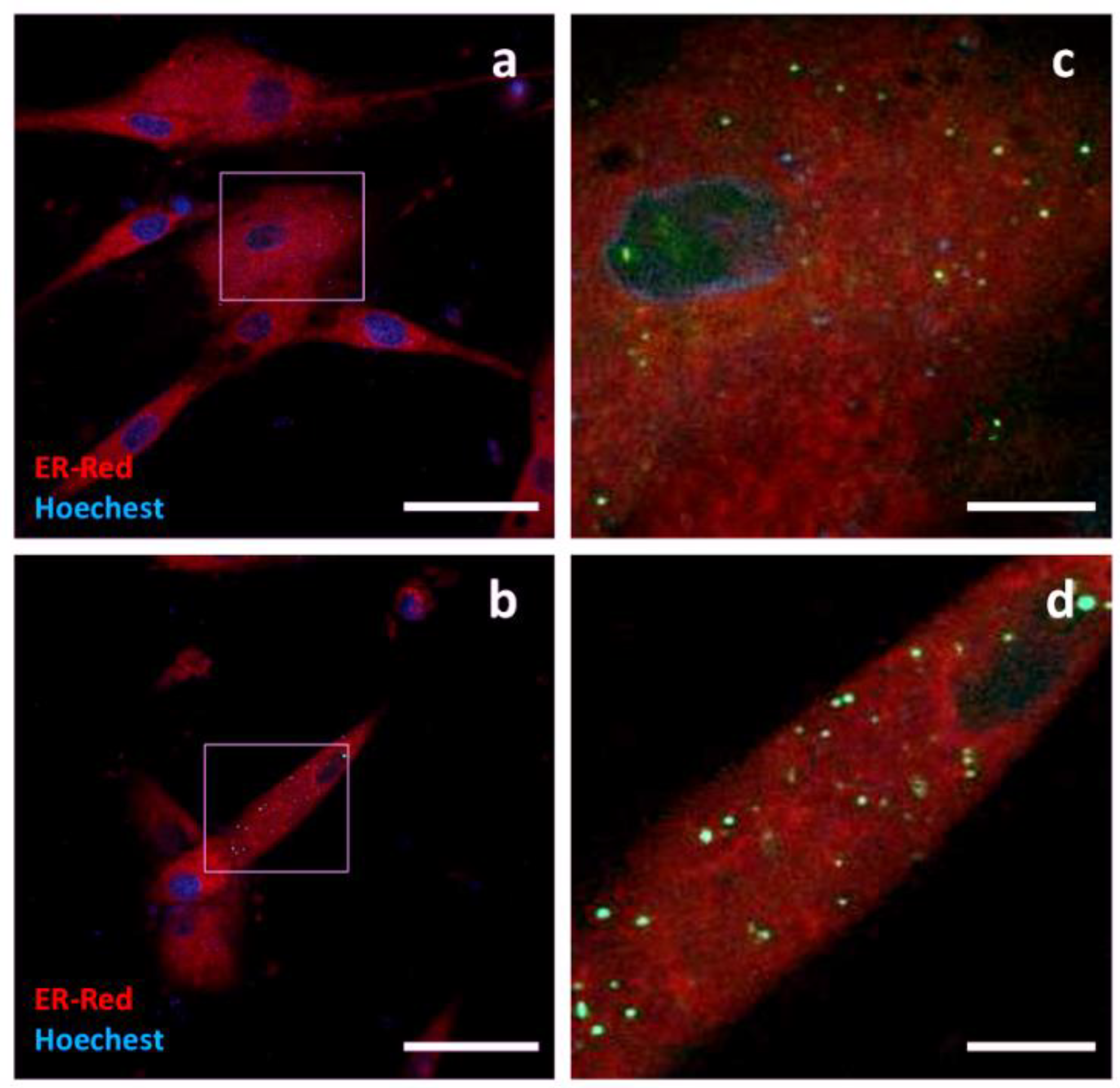

Palmitoylated GFP, a synthetic oligo encoding the N-terminus of canine Lck was ligated into the GFP-encoding plasmid to obtain a fluorescent probe with a palmitoylation signal in the N-terminus of GFP. Canine MSCs overexpressing palm GFP showed diffuse slight fluorescence and immunoreactivity at TEM. Positive surface events could also be detected at TEM. Recurrent strong signals from intracellular compartments were observed; they appeared paranuclear, condensed and negative for ER or lysosome staining (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

EVs mediate intercellular crosstalk under normal and pathological conditions. As cell-derived nanostructures, they are living vehicles that hold promise for the transfer of functional and therapeutic molecules between cells.

Several studies have investigated the possibility of functionalizing EVs with exogenous biomolecules using tags normally involved in EV biogenesis [

9,

10,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

In this study, we engineered MSCs from canine adipose tissue to overexpress GFP tagged with molecules specific to EVs. The aim was to investigate the mechanisms of protein transport into EVs and the possibility of protein delivery into EVs.

For this purpose, CD63, syntenin-1 and TSG101 cDNAs were cloned to obtain the chimeric reporter proteins. Sequencing confirmed the identity of the transcripts and, in the case of syntenin-1, led to the identification of the splice variant lacking glutamine at position 81 (Δ Q81). The specific functions of this variant are not yet known so it was not considered in this study. In addition, the palmitoylation signal of Lck was investigated.

TSG101-GFP gave the worst quantitative result. The minimal number of transfected c-Ad-MSCs only allowed detection by fluorescence microscopy. Western blotting was performed, but no signal could be detected. The low expression efficiency could depend on a variety of factors, including an insufficiently strong Kozak sequence or the presence of repression systems in the cell. Although further evidence is required, the well-defined multifocal pattern suggests a possible localization in multivesicular bodies, as observed by Nabhan and colleagues [

37]. TSG101 has never been used as a tag for EVs engineering but it has been extensively studied in other research areas such as virology. In all these cases, the molecule of interest was bound to the N-terminus of TSG101 [

37,

38,

39]. In our study, GFP was bound to the C-terminus of TSG to make it comparable to the other tags used. It is likely that the different topology between TSG101 and the reporter tags had significant effects on protein expression and stability.

As for the palmitoylation signal, we observed that it can lead to a two-fold enrichment of GFP in EVs compared to untagged GFP. Confocal microscopy revealed that palm-GFP has a pronounced affinity for the cell membrane. C-Ad-MSCs expressing palm-GFP also showed diffuse fluorescence at the cytoplasmic level. In addition, juxta-nuclear fluorescent substructures were detected that topographically corresponded to the Golgi apparatus, where a high concentration of the chimeric protein was expected. Post-translational modifications of proteins by adding hydrophobic groups, the so-called lipidation of proteins, have the main function of ensuring stable interaction with cell membranes. So far, various lipidations have been shown to favor protein loading in EVs [

40]. Palmitoylation is a reversible modification: the lipid anchor is attached to the cysteine residue in the N-term (position 2 or 3) by the enzymes of palmitoyl acyltransferase mainly at the Golgi level and removed by enzymes with esterase activity elsewhere in the cell. For these reasons, the process is considered reversible and can therefore reduce the loading efficiency of EVs. At the same time, it may have the advantage of ensuring cargo detachment from the membrane in recipient cells and subsequent diffusion into the cytoplasm. Lipid anchors are common tags used for EV engineering, especially in EV labelling strategies [

41]. Shen and colleagues compared the “budding ability” of different lipid anchors in combination with reporter proteins. By overexpression in Jurkart cells, they found that myristoylation was the most efficient signal among the markers tested. Lai and colleagues used the palmitoylation signal for engineering EVs and showed the good performance of the tag used and its distribution in different cell membrane structures (exosomes, microvesicles, nanotubes and membrane protrusions) [

42].

Syntenin-1 is a 32 kDa cytoplasmic globular protein with multiple functions. Together with Alix and Sindecan, it is involved as a protein adaptor in the uptake of proteins into exosomes [

43]. By binding various proteins of the cytoskeleton, it modulates the adhesion processes of cells and is involved in the internalization of some membrane receptors [

44]. Due to its multiple functions, it is not possible to determine its exact intracellular localization. Indeed, depending on the interaction and context, syntenin-1 can be localized at the level of the cytoskeleton, in the nucleus, in the perinuclear space and in association with endosomes and multivesicular bodies [

45]. To date, only a few researchers have used syntenin-1 to engineer EVs. Corso et al. confirmed the efficiency of full-length syntenin-1 to incorporate a reporter protein into EVs [

9], Conceição and colleagues used the N-terminal domain of syntenin-1 to generate EVs from Hek293 and human MSCs [

46]. In both papers, many elements and processes, such as EV composition, EV uptake and more, were analyzed in detail, but biogenesis in parental cells was not described.

In our study, cloning of the cDNA encoding syntenin-1 from canine MSC RNA allowed the identification of two different splice variants: Variant 1 (the main variant with a sequence of 298 amino acids) and Variant 2 (which lacks glutamine codon at position 81). Overexpression of Syn-GFP in c-Ad MSCs confirmed the widespread localization in the cytoplasm and revealed small compartments where the chimeric protein was more concentrated, probably indicating multivesicular bodies. Microscopic observation revealed also the presence of numerous fluorescent structures protruding from the cell membrane. WB showed that the full-length chimeric protein (approximately 60 kDa) was mainly concentrated in the cell lysates, while EVs contained lower molecular weight components along with the full-length protein, possibly due to post-translational processing or chimeric proteins generated by alternative start codons. A relatively high loading efficiency of the chimeric protein in the EVs was observed, estimated to be 4.5-fold compared to untagged GFP.

CD63 or TSPAN 30 is a protein belonging to the tetraspanin family, a group of biomolecules with four transmembrane domains that are specific markers for EVs. CD63 performs numerous functions related to the transport of molecules from outside to inside the cell, including internalization of surface molecules, recycling of substances in the endosomal system, and transport to lysosomes [

47]. The use of CD63 as a tag for the transport of proteins into EVs has been reported in several papers. Koumangoy and colleagues used a CD63-GFP expressing tumour cells to describe the role of exosomes in tumour biology [

31]. Stickney and colleagues investigated the feasibility of using tetraspanin proteins (CD9, CD63 and CD81) to engineer EVs with fluorescent probes and tested different topologies for CD63 [

48]. Similar studies were performed by Corso and colleagues, who concluded that CD63 is the most effective tag that can modify EVs [

9]. Kojima and Bojar developed an ingenious system to produce engineered exosomes with CD63 as a tag [

49]. Sung et al. used a pH-sensitive fluorescent reporter system to label EVs from different tumour cell lines using CD63 as a tag. Using this system, they were able to track the secretion dynamics of EVs in space and time [

16]. Strohmeier et al. engineered Hek293 cells with editing systems to obtain a modification at the genomic level in which CD63 is constitutively tagged with GFP or HaloTag [

15]. McNamara and colleagues described the distribution and co-localization of CD63 and CD81 in lipid rafts and EVs secreted by U-2 osteosarcoma cells [

50]. Jurgielewicz et al. described the development of an HTS method to study EV uptake using CD63-GFP-labeled labelled EVs from Hek293 as study material [

14]. Heusermann et al. analyzed the uptake of CD63-GFP or mCherry-labelled EVs of Hek293 by cultured fibroblasts [

51]. All these authors have shown that CD63-labelled production guarantees significant recovery by recipient cells. In addition, some authors described the increase in production/release of EVs by parental cells overexpressing chimeric CD63 proteins. These properties make CD63 an attractive tool for obtaining engineered EVs.

In view of the results obtained in our study, we demonstrated that CD63-GFP appears to be an efficient tagging system. We do not know whether its relative abundance is due to greater expression of the protein or to greater stability and accumulation. Indeed, a higher number of fluorescent c-Ad-MSCs were observed compared to other tags. This could indicate a high transfection efficiency and/or a strong diffusion of the reporter protein between transfected and non-transfected cells. The second hypothesis is also supported by confocal microscopy analysis, which showed many cells with weak fluorescence, possibly due to the uptake of CD63-GFP labelled EVs (data not shown). The estimation of CD63-GFP loading efficiency in EVs showed a relatively low value compared to the other tags, which contrasts with other published papers. The reason for this could be the different culture conditions, which could lead to greater uptake by the cells in culture, or perhaps the different metabolism of the MSCs used in these experiments compared to the Hek293 used in most other studies.

The intracellular localization of CD63-GFP in c-Ad-MSCs confirms the results of other studies performed on cultured cells from humans and mice. In our study, CD63-GFP was mainly detected in the perinuclear region, in association with membrane-bound intracellular compartments morphologically compatible with endosomal elements and multivesicular bodies typically involved in exosome biogenesis.

Western blotting showed that the chimeric protein has a similar pattern to that frequently observed when blotting against CD63, which is due to the different post-translational modifications [

45]. The small amount of untagged GFP in the cell lysate and in the extract of EVs can be interpreted as a possible product of clivated precursor or another ATG start codon during the translation process.

5. Conclusions

In recent years, interest in EVs has increased thanks to their diverse applications in the biomedical field, from diagnostics to therapy. Currently, great expectations are placed on the use of EVs as drug carriers, especially for therapeutic nucleic acids or proteins.

The aim of this work was to develop a system to produce engineered EVs derived from a primary cell type of therapeutic interest in veterinary medicine. Specifically, we used MSCs from adipose tissue of dogs, a species where cell-based and cell-free therapies are at an advanced stage of application. Their efficacy and safety have therefore been demonstrated in many applications in companion animals with very encouraging results.

Interest in MSC secretome and EVs is the natural progression of advanced therapies, both because of their inherent biological activity and their intriguing potential as drug delivery systems.

More and more studies are demonstrating the efficacy and feasibility of cell-free therapies in veterinary medicine [

52]. Although the road to large-scale production of EVs is still long, many companies are interested in developing EV-based therapeutic products. Engineering of EVs is another rapidly growing area of research resulting from the discovery that EVs can be used to transport therapeutic molecules of various types.

To summarize, the novelties presented in this paper are multifaceted. First, we have used primary cells that are already used in the therapy of dog diseases and for which the efficacy and safety of the derived EVs have been demonstrated. Indeed, many research groups have investigated strategies for engineering human and murine cells to modify the protein content of EVs. However, most of this work has utilized cell lines, mainly HEK293. The development of EV-based delivery systems requires a shift to safer cells for in vivo treatments.

Second, we have shown for the first time in dogs that CD63 is the most effective and specific tag to engineer c-Ad-MSC-EVs, as it has the highest expression efficiency and localization specificity. Further studies aimed at better deciphering its contribution and clarifying which part of the molecule is involved in vesicle trafficking could provide insights into EVs bioengineering. However, it should not be overlooked that the other tags tested, in particular syntenin, have also provided encouraging results regarding the loading of EVs. This confirms that a protein of interest enters EVs more efficiently when tagged with EVs-related proteins and opens the possibility of using different tags in canine EV engineering.

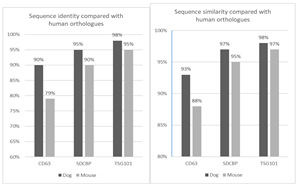

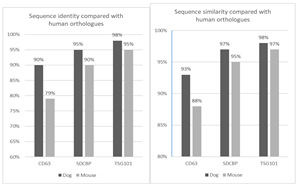

Third, we have used MSCs derived from an animal species that is not only interesting as a target species for potential personalized therapy with functionalized EVs but also represents a model for the development of therapies for humans that is much closer and more reliable than the mouse model.

In this particular case, the human protein sequences of CD63, syntenin 1 and TSG101 show higher identity and similarity to those of dogs than to those of mice (

Appendix B). Last but not least, from a purely technological point of view, we have demonstrated the feasibility of a method to obtain GFP-tagged MSC-EVs that could be useful for the study of vesicle biogenesis and for experiments on EV trafficking.

Our long-term goal is to produce therapeutic MSC-EVs that can be used in animals with spontaneous diseases and serve as reliable models for human pathologies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S. and L.P.; methodology, G.S., L.A., O.B., L.P., T.B.; validation, L.P. and T.B.; investigation, G.S., G.P., S.C., MR.C., S.M., L.M., P.CP., A.S.; resources, A.B., R.G., S.C.; data curation, G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S.; writing—review and editing, L.P. and T.B.; supervision, L.P. and T.B.; project administration, L.P.; funding acquisition, L.P.” All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University of Perugia Grant FONDO D’ATENEO PER LA RICERCA DI BASE 2019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required as the cells used in this study were isolated from adipose tissue harvested, after the owner’s consent, from animals that died of traumatic causes.

Data Availability Statement

Animals’ owners gave their written informed consent to the sampling of tissues for didactic and research purposes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Cristina Gasparri for her careful proofreading of this paper and Dr. Stefano Petrini from Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Umbria e delle Marche “Togo Rosati” for the assistance in EVs isolation procedure.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following main abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EVs |

Extracellular vesicles |

| Ex |

Exosomes |

| MVBs |

Multivesicular bodies |

| MVs |

Microvesicles |

| ABs |

Apoptotic bodies |

| ESCRT |

Endosomal sorting complex required for transport |

| MSCs |

Mesenchymal Stromal Cells |

| c-Ad-MSCs |

Canine adipose-derived MSCs |

| GFP |

Green Fluorescent Protein |

| OVUD |

Veterinary University Hospital |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle Medium |

| SVF |

Stromal Vascular Fraction |

| FBS |

Fetal Bovine Serum |

| ISCT |

International Society for Cell and Gene Therapy |

| DPBS |

Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Comparison of identity and similarity of CD63, Syntenin and TSG101 among humans, dog and mouse species.

Table A1.

Comparison of identity and similarity of CD63, Syntenin and TSG101 among humans, dog and mouse species.

| Sequence ID |

DOG |

HUMAN |

MOUSE |

| CD63 (Tspan30) |

XP_038534846.1 |

NP_001244318.1 |

NP_001036045.1 |

| SDCBP (Syntenin1) |

XP_038297152.1 |

NP_001091697.1 |

NP_001007068.1 |

| TSG101 |

XP_038286593.1 |

NP_006283.1 |

NP_068684.1 |

CD63

| |

Identity |

Similarity |

| Canine vs Human |

214/238 (90%) |

223/238 (93%) |

| Human vs Murine |

189/238 (79%) |

210/238 (88%) |

SDCBP (Syntenin 1)

| |

Identity |

Similarity |

| Canine vs Human |

282/298 (95%) |

292/298 (97%) |

| Human vs Murine |

270/299 (90%) |

287/299 (95%) |

TSG101

| |

Identity |

Similarity |

| Canine vs Human |

382/391 (98%) |

384/391 (98%) |

| Human vs Murine |

370/391 (95%) |

381/391 (97%) |

Appendix B

References

- J. Meldolesi, ‘Exosomes and Ectosomes in Intercellular Communication’, Apr. 23, 2018, Cell Press. [CrossRef]

- P. Simeone et al., ‘Extracellular vesicles as signaling mediators and disease biomarkers across biological barriers’, Apr. 01, 2020, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- G. Van Niel, G. D’Angelo, and G. Raposo, ‘Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles’, Apr. 01, 2018, Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- J. Burrello et al., ‘Extracellular Vesicle Surface Markers as a Diagnostic Tool in Transient Ischemic Attacks’, Stroke, pp. 3335–3347, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Tamura, Y. Yoshioka, S. Sakamoto, T. Ichikawa, and T. Ochiya, ‘Extracellular vesicles as a promising biomarker resource in liquid biopsy for cancer’, Extracell Vesicles Circ Nucl Acids, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Simonazzi, A. G. Cid, M. Villegas, A. I. Romero, S. D. Palma, and J. M. Bermúdez, ‘Nanotechnology applications in drug controlled release’, in Drug Targeting and Stimuli Sensitive Drug Delivery Systems, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 81–116. [CrossRef]

- S. Villata, M. Canta, and V. Cauda, ‘Evs and bioengineering: From cellular products to engineered nanomachines’, Sep. 01, 2020, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- B. Crivelli et al., ‘Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell extracellular vesicles: From active principle to next generation drug delivery system’, Sep. 28, 2017, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- G. Corso et al., ‘Systematic characterization of extracellular vesicles sorting domains and quantification at the single molecule–single vesicle level by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and single particle imaging’, J Extracell Vesicles, vol. 8, no. 1, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang, J. Yu, T. Kadungure, J. Beyene, H. Zhang, and Q. Lu, ‘ARMMs as a versatile platform for intracellular delivery of macromolecules’, Nat Commun, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Teng and M. Fussenegger, ‘Shedding Light on Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Bioengineering’, Jan. 01, 2021, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- K. Trajkovic et al., ‘Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes’, Science (1979), vol. 319, no. 5867, pp. 1244–1247, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- G. van Niel et al., ‘The Tetraspanin CD63 Regulates ESCRT-Independent and -Dependent Endosomal Sorting during Melanogenesis’, Dev Cell, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 708–721, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Jurgielewicz, Y. Yao, and S. L. Stice, ‘Kinetics and Specificity of HEK293T Extracellular Vesicle Uptake using Imaging Flow Cytometry’, Nanoscale Res Lett, vol. 15, no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Strohmeier et al., ‘Crispr/cas9 genome editing vs. Over-expression for fluorescent extracellular vesicle-labeling: A quantitative analysis’, Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. H. Sung et al., ‘A live cell reporter of exosome secretion and uptake reveals pathfinding behavior of migrating cells’, Nat Commun, vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Voga, N. Adamic, M. Vengust, and G. Majdic, ‘Stem Cells in Veterinary Medicine—Current State and Treatment Options’, May 29, 2020, Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Caplan, ‘Mesenchymal stem cells: Time to change the name!’, Stem Cells Transl Med, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 1445–1451, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Keshtkar, N. Azarpira, and M. H. Ghahremani, ‘Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: Novel frontiers in regenerative medicine’, Mar. 09, 2018, BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Lopez-Verrilli, A. Caviedes, A. Cabrera, S. Sandoval, U. Wyneken, and M. Khoury, ‘Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes from different sources selectively promote neuritic outgrowth’, Neuroscience, vol. 320, pp. 129–139, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Wu, B. Zhang, H. Shi, H. Qian, and W. Xu, ‘MSC-exosome: A novel cell-free therapy for cutaneous regeneration’, Mar. 01, 2018, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- G. Zheng et al., ‘Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles: regenerative and immunomodulatory effects and potential applications in sepsis’, Oct. 01, 2018, Springer Verlag. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Vonk, T. S. De Windt, I. C. M. Slaper-Cortenbach, and D. B. F. Saris, ‘Autologous, allogeneic, induced pluripotent stem cell or a combination stem cell therapy? Where are we headed in cartilage repair and why: A concise review’, May 15, 2015, BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- M. Neupane, C. C. Chang, M. Kiupel, and V. Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan, ‘Isolation and characterization of canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells’, Tissue Eng Part A, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 1007–1015, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. Ivanovska et al., ‘Immunophenotypical characterization of canine mesenchymal stem cells from perivisceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue by a species-specific panel of antibodies’, Res Vet Sci, vol. 114, pp. 51–58, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Hedayati et al., ‘Polymorphisms in the AOX2 gene are associated with the rooting ability of olive cuttings’, Plant Cell Rep, vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 1151–1164, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Dominici et al., ‘Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement’, Cytotherapy, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 315–317, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- G. Scattini, M. Pellegrini, G. Severi, M. Cagiola, and L. Pascucci, ‘The Stromal Vascular Fraction from Canine Adipose Tissue Contains Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Subpopulations That Show Time-Dependent Adhesion to Cell Culture Plastic Vessels’, Animals, vol. 13, no. 7, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cheng and J. S. Schorey, ‘Targeting Soluble Proteins to Exosomes Using a Ubiquitin Tag’, Biotechnol. Bioeng, vol. 113, pp. 1315–1324, 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Geeurickx et al., ‘The generation and use of recombinant extracellular vesicles as biological reference material’, Nat Commun, vol. 10, no. 1, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Koumangoye, A. M. Sakwe, J. S. Goodwin, T. Patel, and J. Ochieng, ‘Detachment of breast tumor cells induces rapid secretion of exosomes which subsequently mediate cellular adhesion and spreading’, PLoS One, vol. 6, no. 9, 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. P. Lai et al., ‘Visualization and tracking of tumour extracellular vesicle delivery and RNA translation using multiplexed reporters’, Nat Commun, vol. 6, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. Meyer, J. Losacco, Z. Stickney, L. Li, G. Marriott, and B. Lu, ‘Pseudotyping exosomes for enhanced protein delivery in mammalian cells’, Int J Nanomedicine, vol. 12, pp. 3153–3170, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- U. Sterzenbach, U. Putz, L. H. Low, J. Silke, S. S. Tan, and J. Howitt, ‘Engineered Exosomes as Vehicles for Biologically Active Proteins’, Molecular Therapy, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 1269–1278, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. H. Sung et al., ‘A live cell reporter of exosome secretion and uptake reveals pathfinding behavior of migrating cells’, Nat Commun, vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Yamamoto et al., ‘Inflammation-induced endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles modulate the cellular status of pericytes’, Sci Rep, vol. 5, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Nabhan, R. Hu, R. S. Oh, S. N. Cohen, and Q. Lu, ‘Formation and release of arrestin domain-containing protein 1-mediated microvesicles (ARMMs) at plasma membrane by recruitment of TSG101 protein’, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 109, no. 11, pp. 4146–4151, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. P. Horgan, S. R. Hanscom, E. E. Kelly, and M. W. McCaffrey, ‘Tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101) is a novel binding-partner for the class II Rab11-FIPs’, PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 2, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Rauch and J. Martin-Serrano, ‘Multiple Interactions between the ESCRT Machinery and Arrestin-Related Proteins: Implications for PPXY-Dependent Budding’, J Virol, vol. 85, no. 7, pp. 3546–3556, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Y. T. Wu et al., ‘Multiresolution Imaging Using Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer Identifies Distinct Biodistribution Profiles of Extracellular Vesicles and Exomeres with Redirected Tropism’, Advanced Science, vol. 7, no. 19, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Jiang, X. Zhang, X. Chen, P. Aramsangtienchai, Z. Tong, and H. Lin, ‘Protein Lipidation: Occurrence, Mechanisms, Biological Functions, and Enabling Technologies’, Feb. 14, 2018, American Chemical Society. [CrossRef]

- B. Shen, N. Wu, M. Yang, and S. J. Gould, ‘Protein targeting to exosomes/microvesicles by plasma membrane anchors’, Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 286, no. 16, pp. 14383–14395, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Baietti et al., ‘Syndecan-syntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes’, Nat Cell Biol, vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 677–685, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Hwangbo et al., ‘Syntenin regulates TGF-β1-induced Smad activation and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by inhibiting caveolin-mediated TGF-β type i receptor internalization’, Oncogene, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 389–401, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. R. D. Johnson et al., ‘A paradigm in immunochemistry, revealed by monoclonal antibodies to spatially distinct epitopes on syntenin-1’, Int J Mol Sci, vol. 20, no. 23, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Conceição et al., ‘Engineered extracellular vesicle decoy receptor-mediated modulation of the IL6 trans-signalling pathway in muscle’, Biomaterials, vol. 266, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Pols and J. Klumperman, ‘Trafficking and function of the tetraspanin CD63’, May 15, 2009, Academic Press Inc. [CrossRef]

- Z. Stickney, J. Losacco, S. McDevitt, Z. Zhang, and B. Lu, ‘Development of exosome surface display technology in living human cells’, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, vol. 472, no. 1, pp. 53–59, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Kojima et al., ‘Designer exosomes produced by implanted cells intracerebrally deliver therapeutic cargo for Parkinson’s disease treatment’, Nat Commun, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. P. McNamara et al., ‘Imaging of surface microdomains on individual extracellular vesicles in 3-D’, J Extracell Vesicles, vol. 11, no. 3, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Heusermann et al., ‘Exosomes surf on filopodia to enter cells at endocytic hot spots, traffic within endosomes, and are targeted to the ER’, Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 213, no. 2, pp. 173–184, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Saba, M. A. Sandhu, and A. Pelagalli, ‘Canine Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Exosomes: State-of-the-Art Characterization, Functional Analysis and Applications in Various Diseases’, May 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).