1. Introduction

Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, our lives have undergone significant changes, introducing terms such as distant learning, quarantine, social distancing, and flexible working into our daily routines[

1]. Such events have historically reshaped our environments, compelling us to adapt to new ways of living in response to the challenges posed by pandemics[

2]. Architects and designers face formidable challenges during pandemics, as they must balance the need to prevent physical interactions with the requirements for quarantine [

3]. Before the pandemic, homes primarily served as places for rest and familial interaction. However, with the onset of COVID-19, residences rapidly transformed into multifunctional spaces accommodating work, education, recreation, and commercial activities [

4,

5,

6]. This shift has underscored the importance of adaptable living environments that can meet diverse needs during such crises, necessitating new adaptive and spontaneous typologies to accommodate people’s needs [

3] (p. 6).

Research into housing satisfaction intersects with various scientific disciplines, each offering a unique set of definitions. Fundamentally, this concept is perceived as the discrepancy between what individuals expect and need from their living situations and what they actually experience[

7]. Housing satisfaction is recognized as a multidimensional entity influenced by a mix of ecological and socio-geographic elements [

8]. It necessitates residents’ detailed evaluation of their physical and social environments. The assessment of resident satisfaction crucially hinges on the quality of the interior, a broad term that encompasses different aspects of housing and merges objective with subjective elements [

11]. This idea also pertains to the building’s physical condition and additional amenities and services that enhance a location’s appeal, as well as features particular to the residents [

12]. Liu [

9]described the quality of life as the expression of a set of “wants” which, when supplied together, makes the individual happy or satisfied. This brings forth the question of how these “wants” transformed when people were forced to remain inside for extended periods due to an unprecedented event. In his study [

1] investigated factors that were affecting the residential satisfaction and found that factors such as lacking of a view, presence of a garden, number of bathrooms and living rooms, as well as the size and number of balconies affect the residential satisfaction of the participants. Moreover, the study stated that the lack of a storage area was not affecting the satisfaction of the residents rather factors such as ventilation, privacy with noise isolation, flexible spaces, and need for natural day light were the primary concerns of the residents. Kim and Kim (2023) found similar results regarding the dissatisfaction of residents with their living spaces and their study showed that people were dissatisfied with the home due to the inability of their current space to meet the new and changed functions such as need the need for multiple bathrooms and the study revealed that living room, bedroom, and kitchen were among the spaces that residents spent most of their times and these spaces need to be designed in such a way that supports newly absorbed functions into the indoor space.

Numerous studies have examined apartment and housing satisfaction levels through various quality indicators such as construction quality, furnishing quality, ventilation, room size and additional rooms and spaces [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Hijazi and Attiah [

13] revealed that the lack of an extra space in apartments compelled residents to work from kitchens or reception areas, with multiple individuals inside the house sharing these spaces. Hajjar [

12] found similar results in Lebanon, where people performed work and study activities in living rooms, dining rooms, and reception areas, lacking privacy. Itma and Monna [

15] performed similar research and assessed the suitability of open and closed plans for situations like the COVID-19 pandemic and found that open plan designs are less suited for such situations as compared to traditional closed plan designs since the separated spaces in the closed plans easily allow residents to convert the available spaces to their new needs such as offices or quarantine areas, creating private spaces as well as multi-functional spaces. Concerning isolation and disease prevention during the pandemic, studies have showed the necessity for houses to include separate bathrooms and bedrooms so as an infected individual will be able to safely isolate himself from the healthy occupants during the infection period [

5,

15,

16,

17] Moreover, regarding the size of the isolation rooms, studies claimed that the rooms need to be large enough for the infected individual to be able to set up a temporary workstation in the room and carry out their tasks while safely isolating him/herself from other occupants. (Al-ayash, 2020; Spennemann, 2021; Marcel et al., 2020) One more study [

19] concerning the space usage during the pandemic in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia found that residents disposed of some furniture to adapt to new needs and allocate spaces for other activities and entertainment. Bettaieb and Alsabban [

19] claim that inhabitants incorporated a coffee area in their homes during the pandemic as an alternative to visiting cafes because they were not able to do so in due to strict rules of the pandemic, such adaptation focuses on reconfiguring existing spaces to fulfill new living requirements, illustrating that flexibility often depends more on residents’ perceptions and minor adjustments than on major architectural changes.

The confinement induced by the COVID-19 pandemic has elevated the importance of determining the physical, spatial, social, and urban conditions under which millions of families worldwide choose to live [

20]. Consequently, the demand for higher living standards when purchasing or leasing properties has surged. This shift underscores the growing necessity for rigorously developed assessment methods that can comprehensively evaluate housing by considering its multifaceted, conflicting, and often incompatible aspects [

21]. In Erbil City, like many other cities around the world, the pandemic compelled residents to repurpose their homes to accommodate a wide range of activities, transforming living spaces into multifunctional hubs for work, education, recreation, and self-care. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate apartments resident’s’ satisfaction in Erbil City during three distinct stages—before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic—using five interior space quality indicators: number, area, proportion, privacy, and functional relationship.

4. Discussion

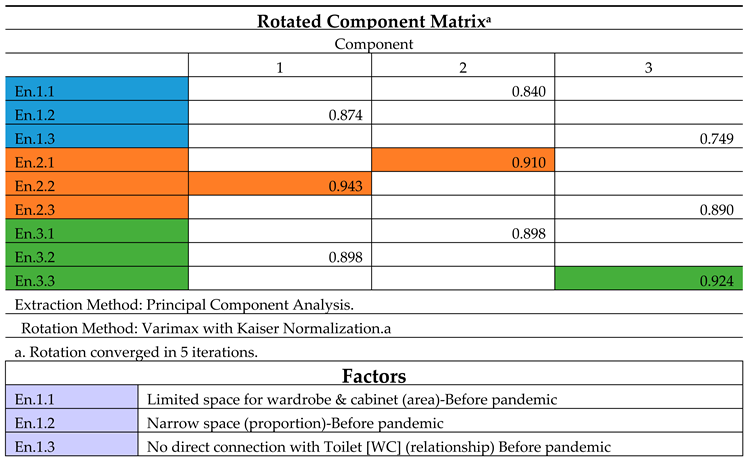

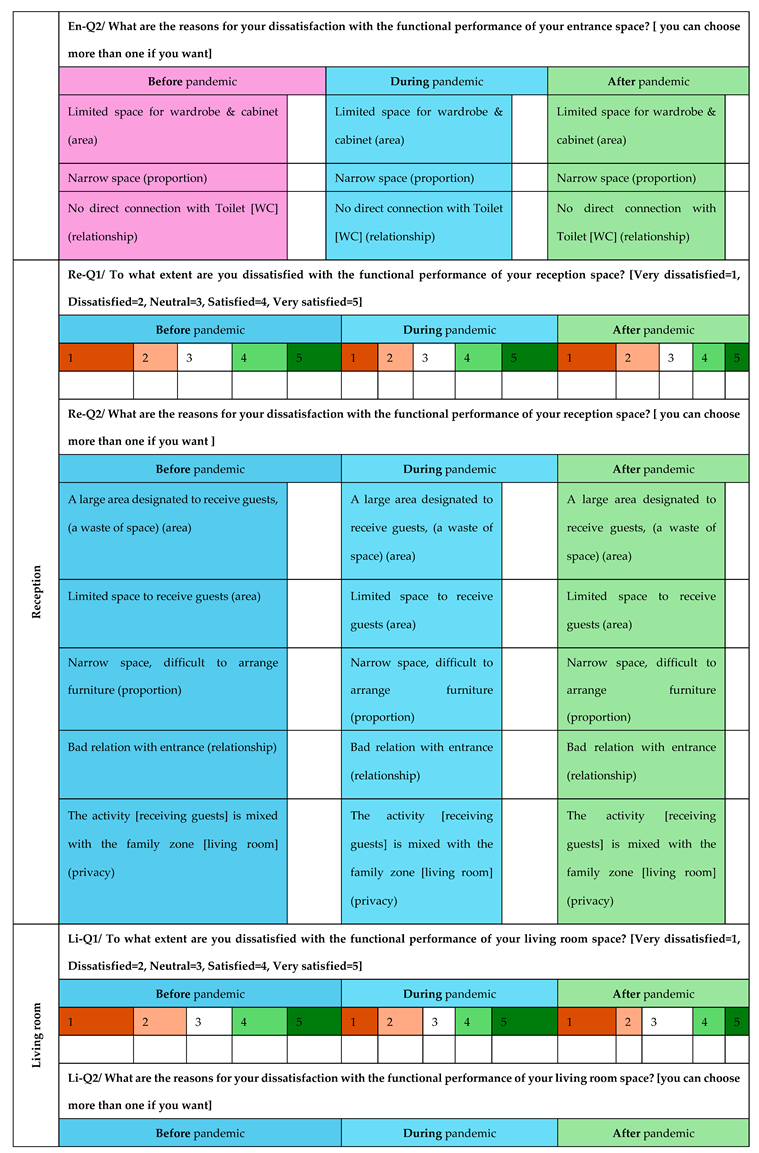

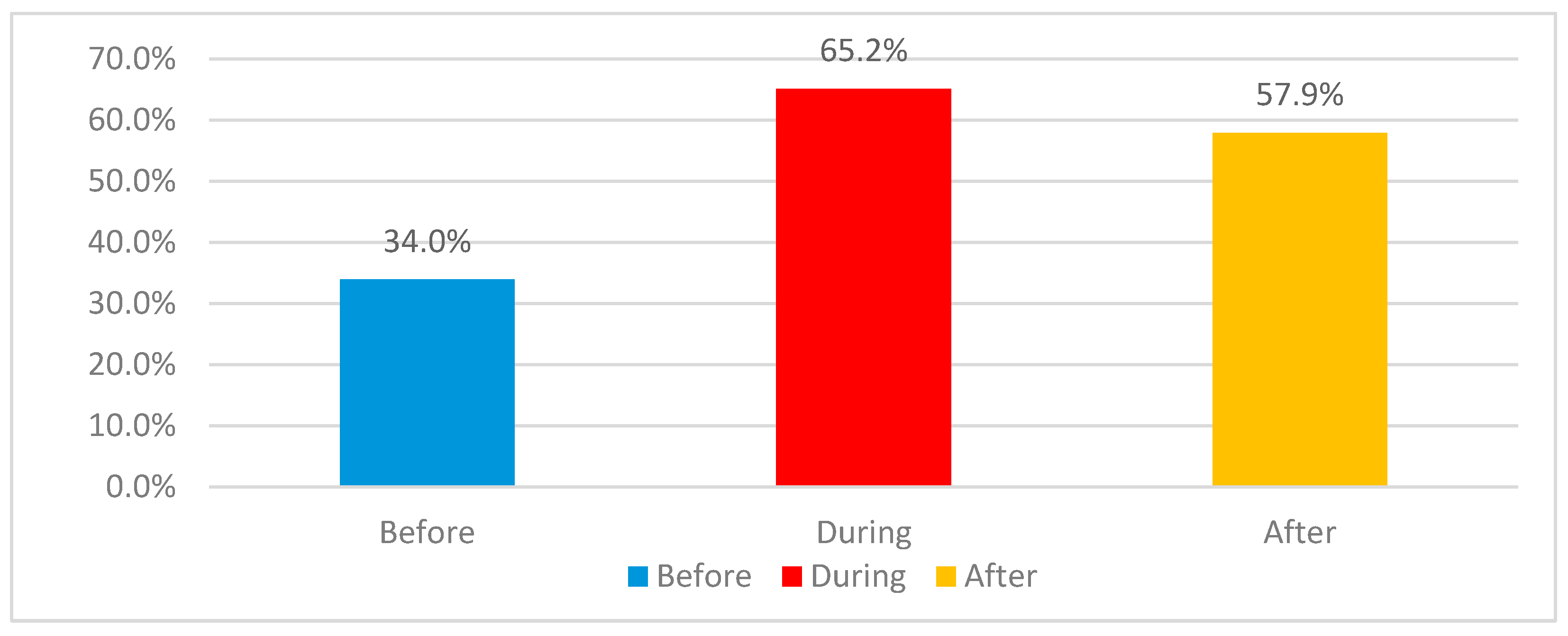

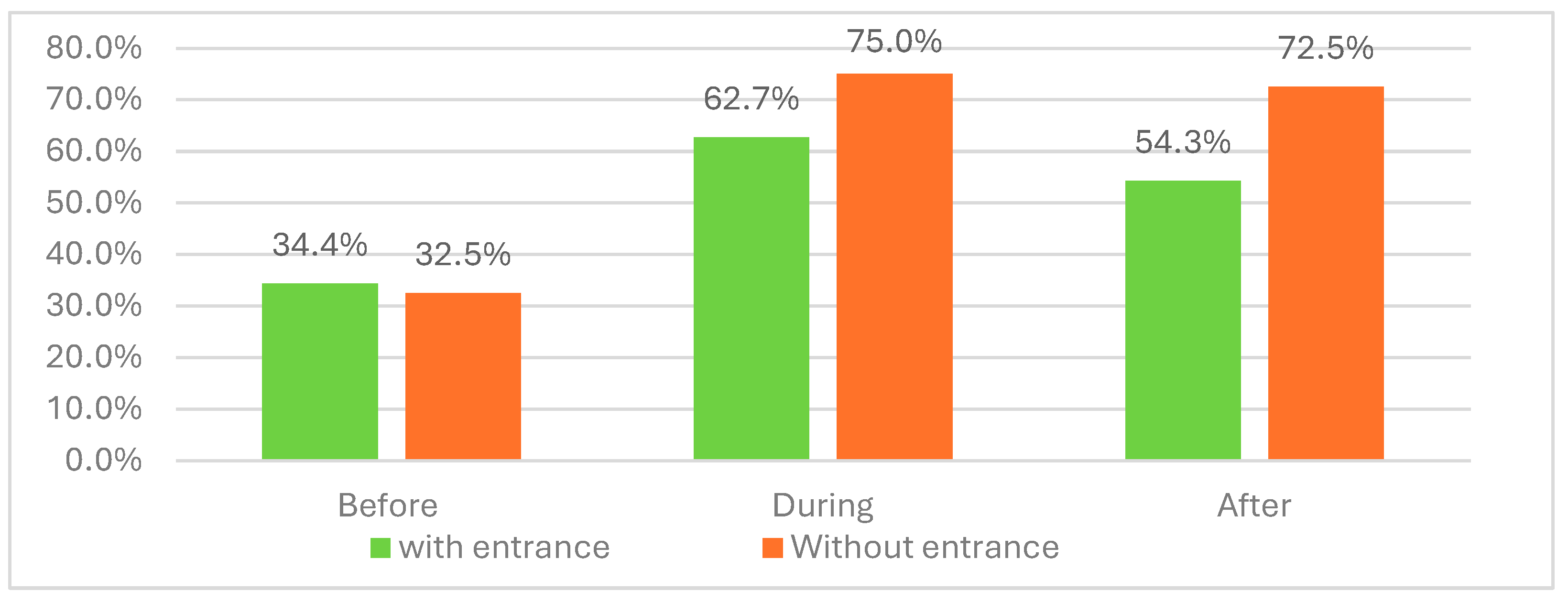

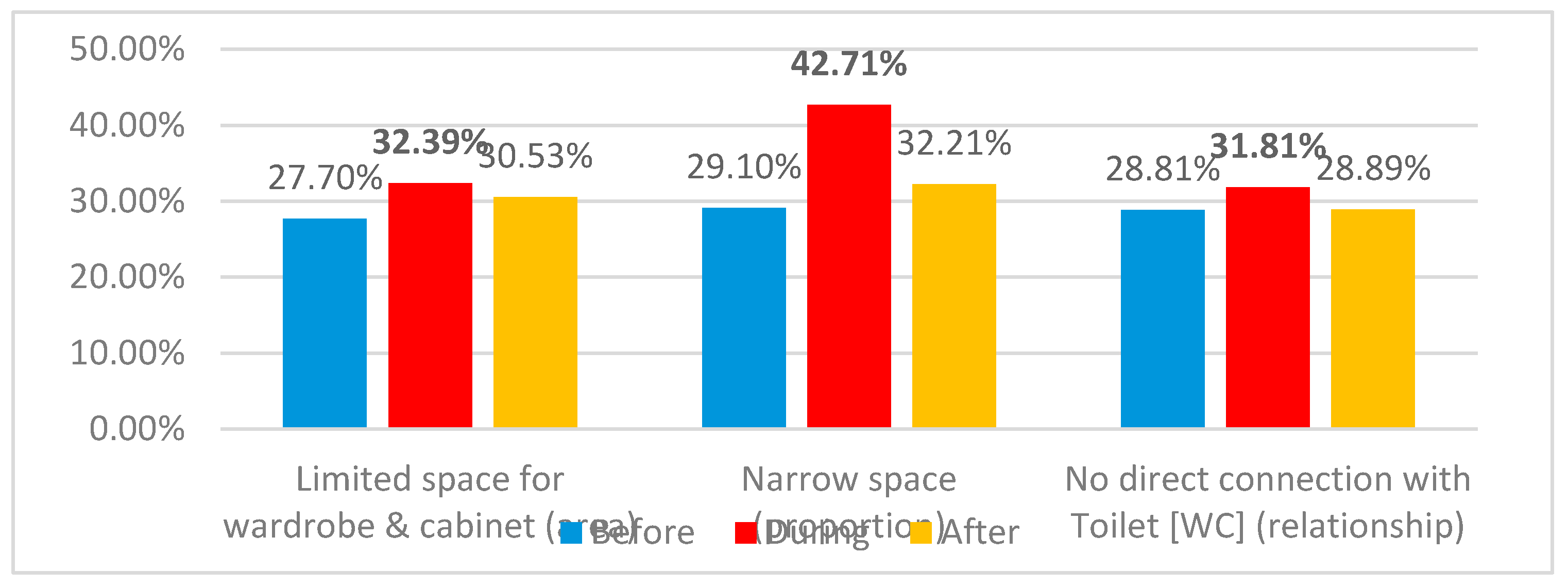

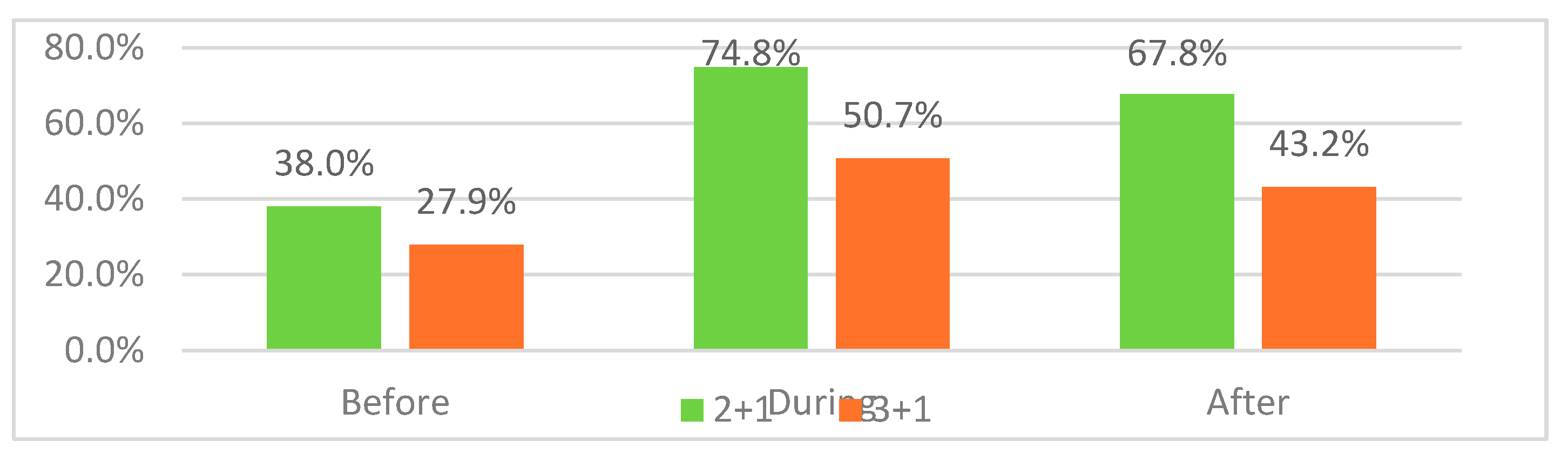

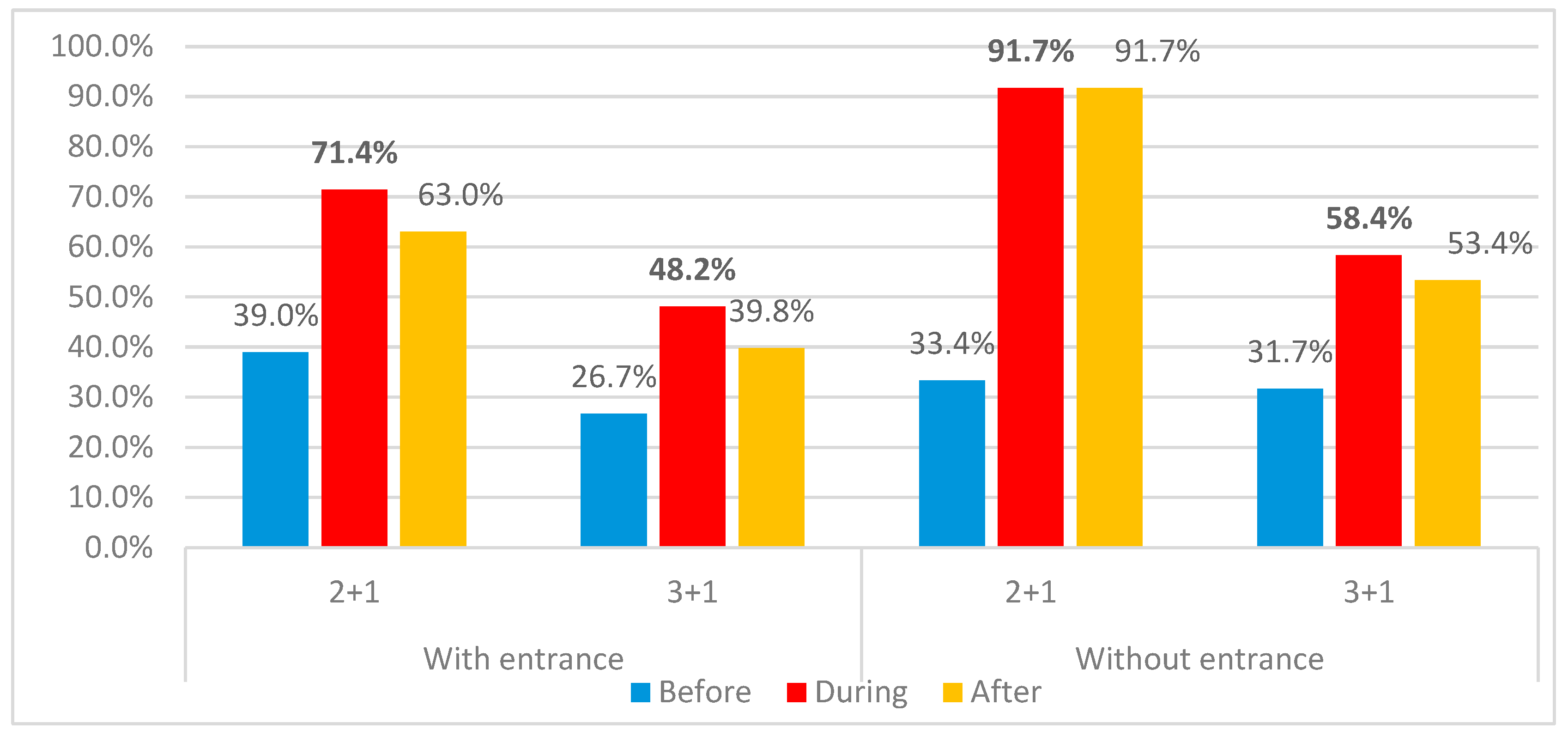

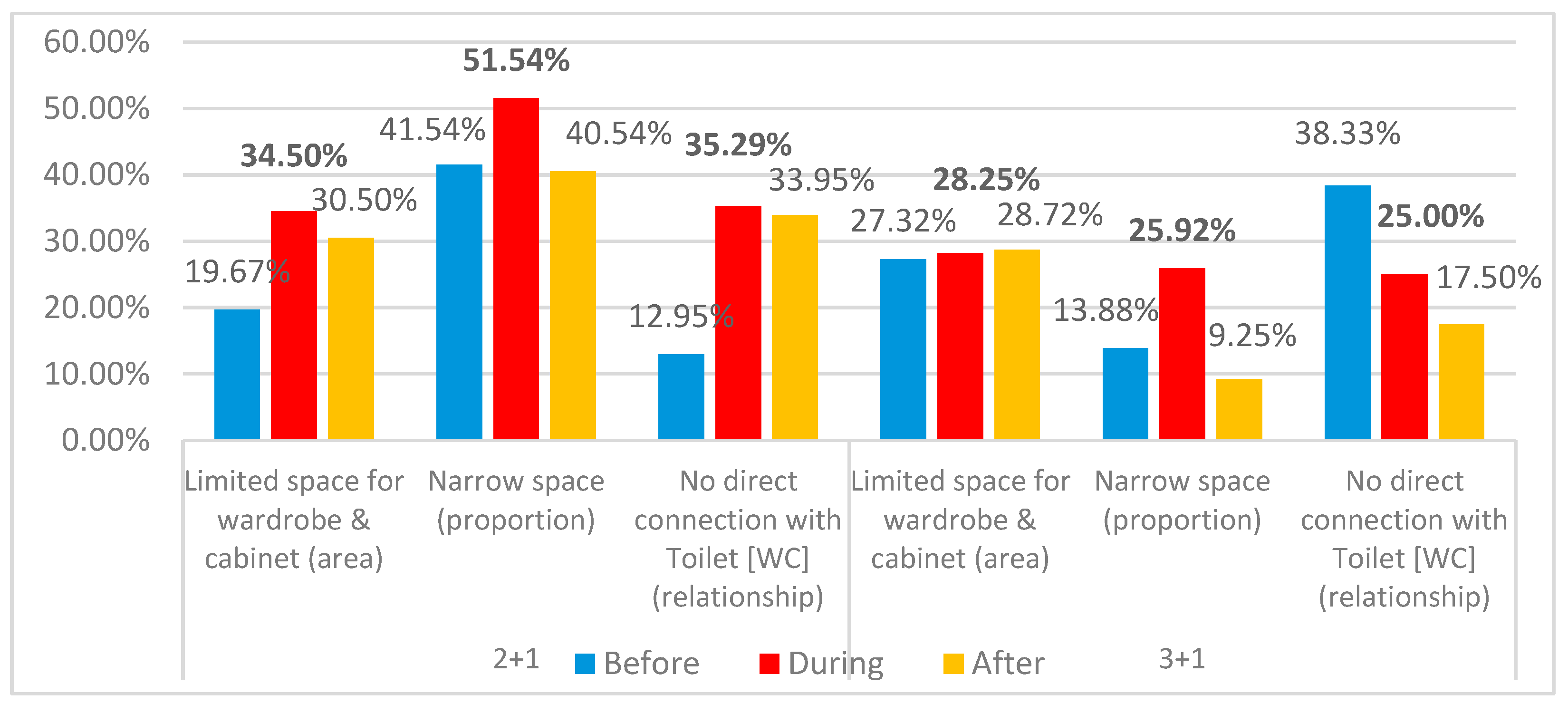

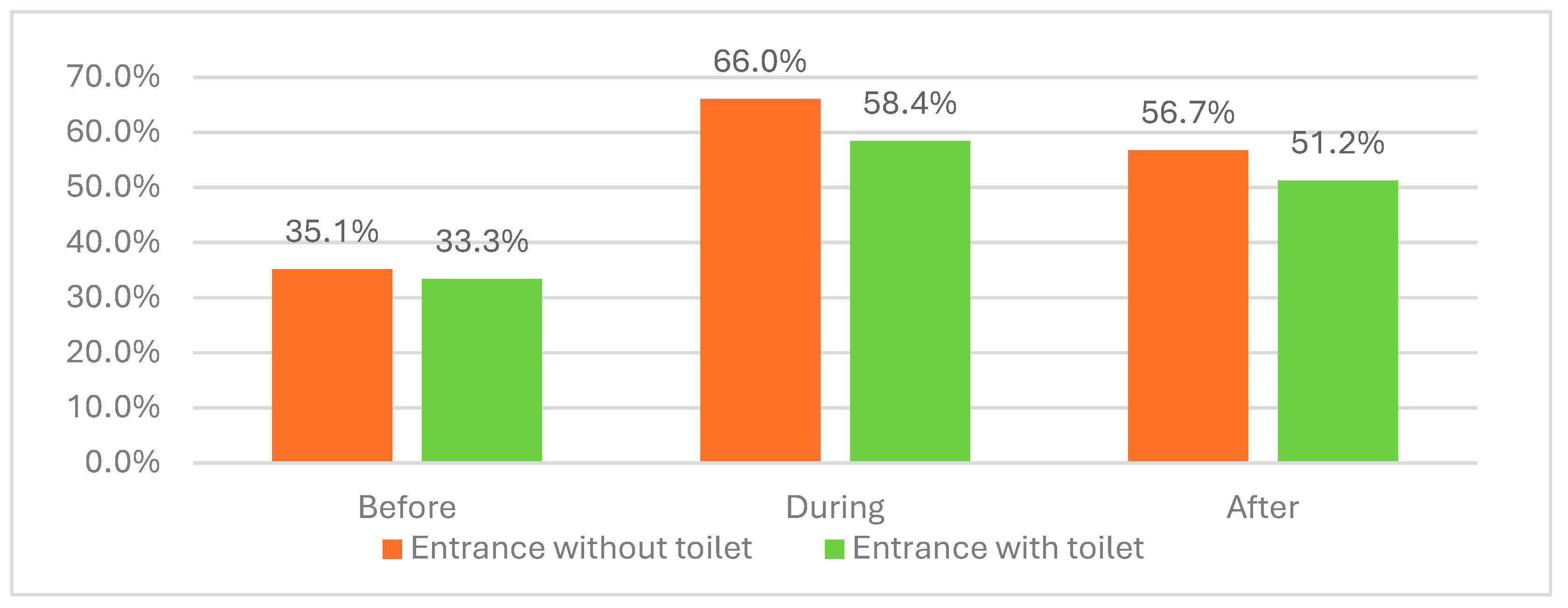

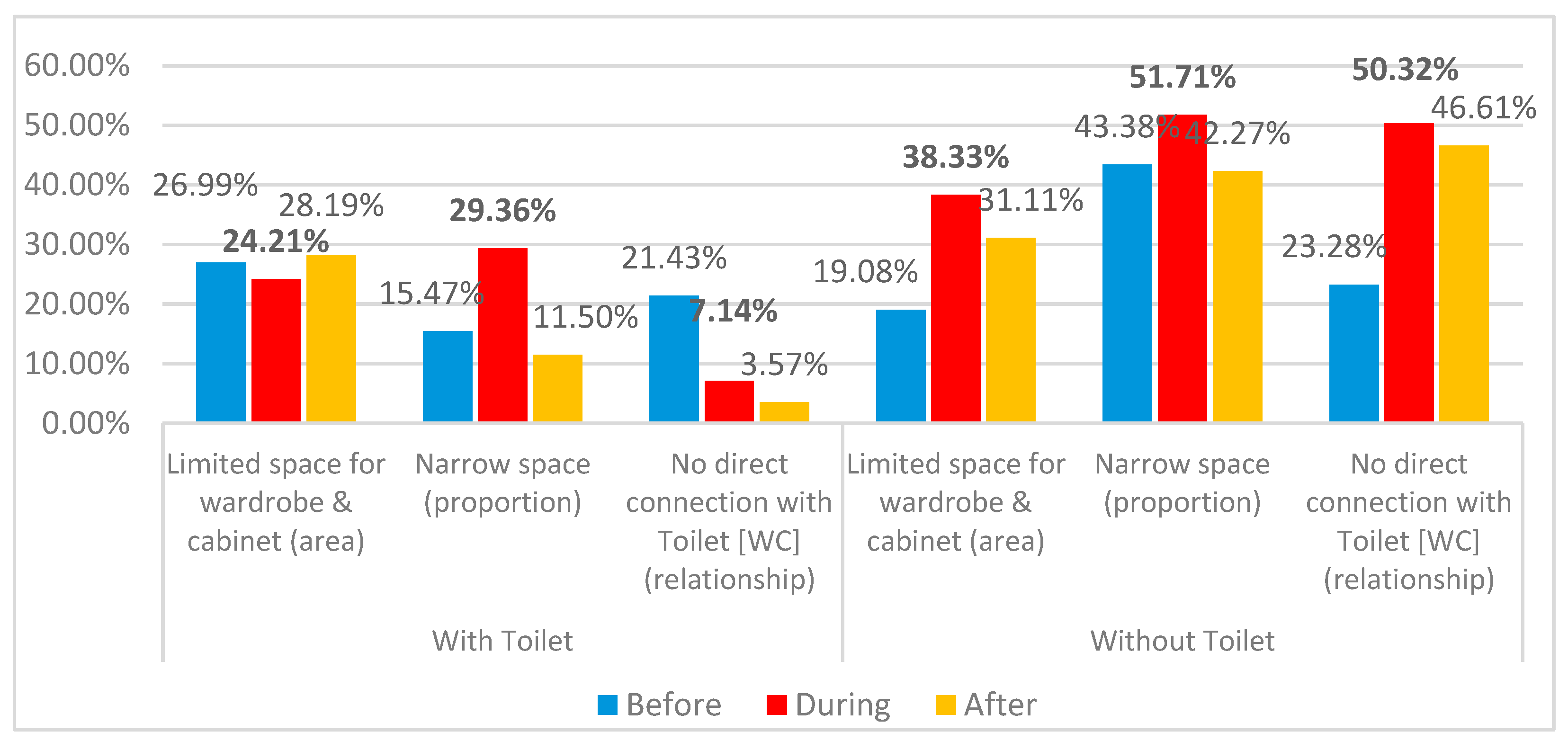

Considering the results, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on apartment satisfaction levels in Erbil City revealed significant insights into the importance of interior space quality. The presence of an entrance lobby significantly influenced resident satisfaction during and after the pandemic. Dissatisfaction was markedly higher among those without an entrance lobby, increasing from 32.5% before the pandemic to 75.0% during it, and slightly reducing to 72.5% afterward. In contrast, apartments with entrance lobbies experienced increased a little lesser dissatisfaction rate, from 34.4% before the pandemic to 62.7% during the pandemic. Key reasons for dissatisfaction included the proportion of the lobby, the area, and the connectivity with an entrance toilet. The analysis also highlighted differences between apartment types with smaller units (2+1) showing greater dissatisfaction compared to larger units (3+1), particularly during the pandemic, with dissatisfaction nearly doubling from pre-pandemic levels and then slightly decreasing post-pandemic. Additionally, the availability of a toilet within the lobby significantly impacted dissatisfaction levels, showing a clear increase during the pandemic for apartments without this feature, and a significant impact related to the distance of the toilet from the entrance. The results go in line with those found by Fakhimi [

18] and Gür [

22] who found out adequate design of entrances and availability of hand washing basins, toilets and dressing rooms close to entrances affects resident satisfaction. These findings underline the critical role of entrance lobbies in enhancing residential satisfaction, especially during health crises, and suggest that both the functionality and design of these spaces are crucial in meeting residents’ expectations and needs.

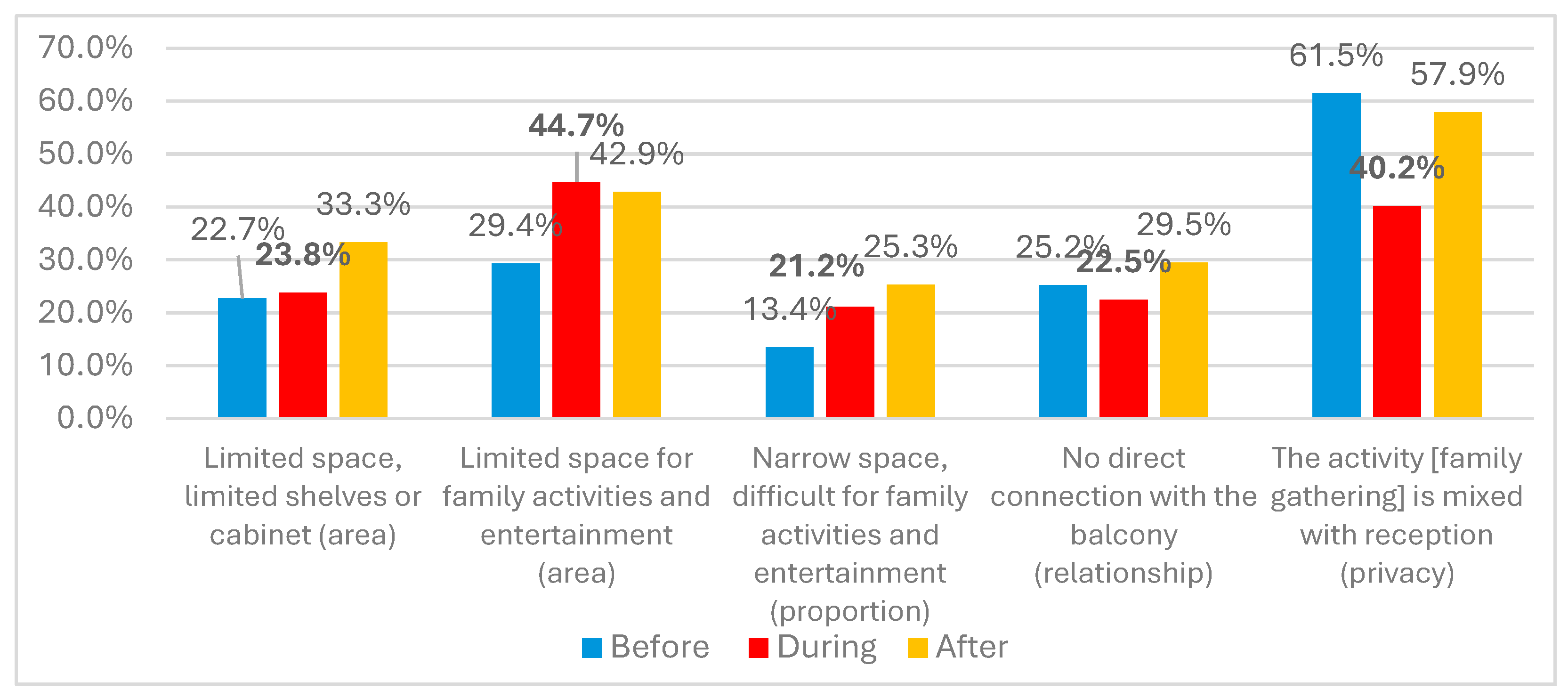

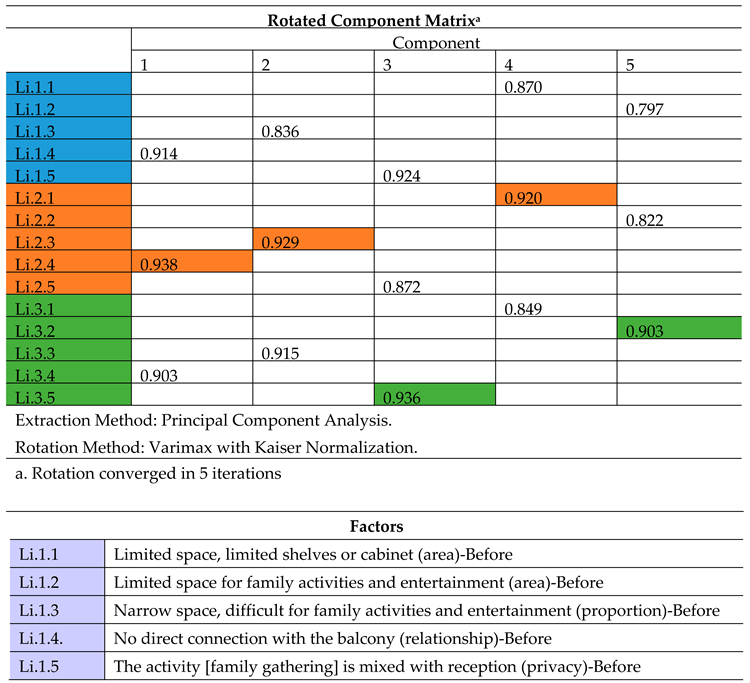

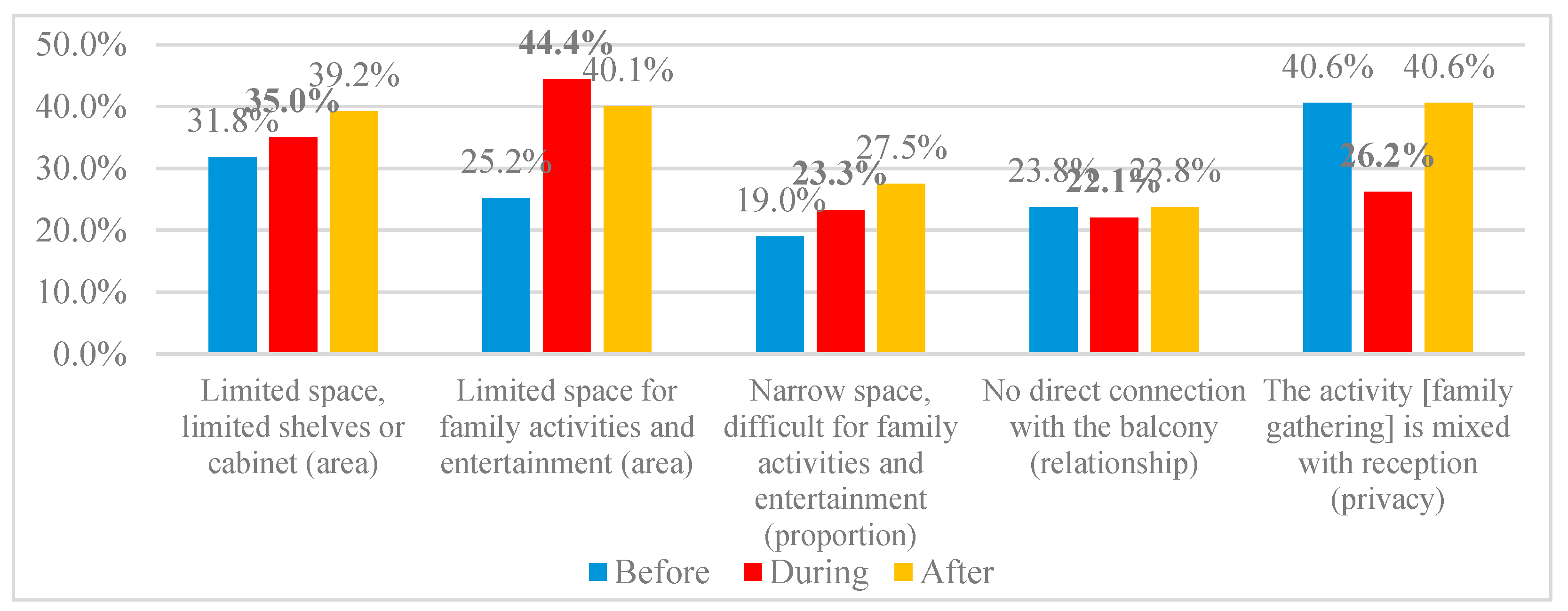

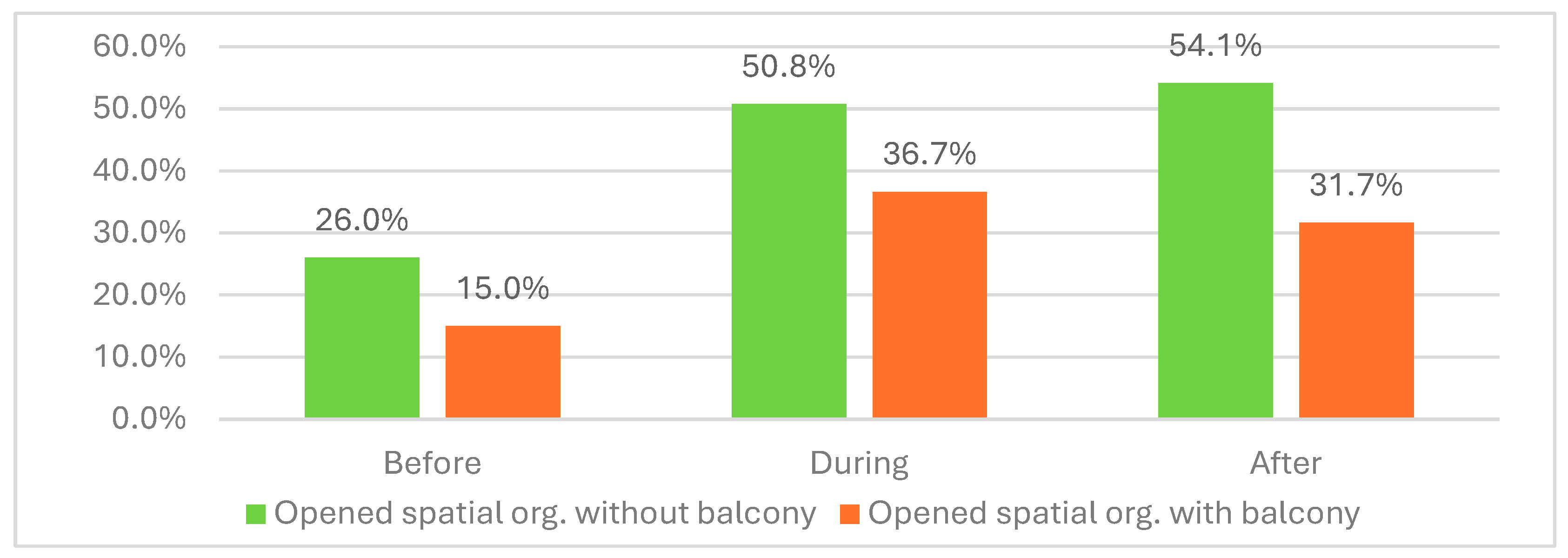

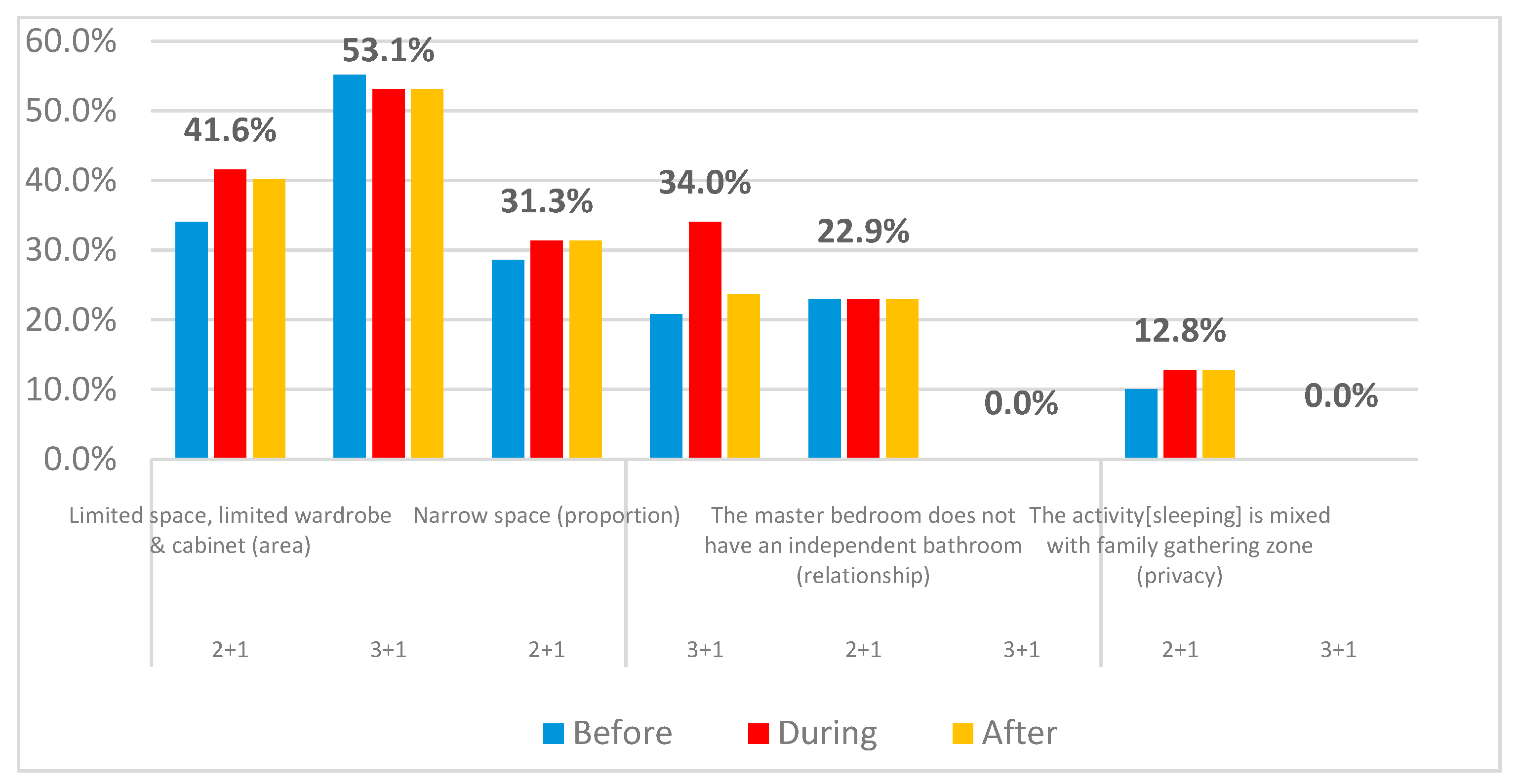

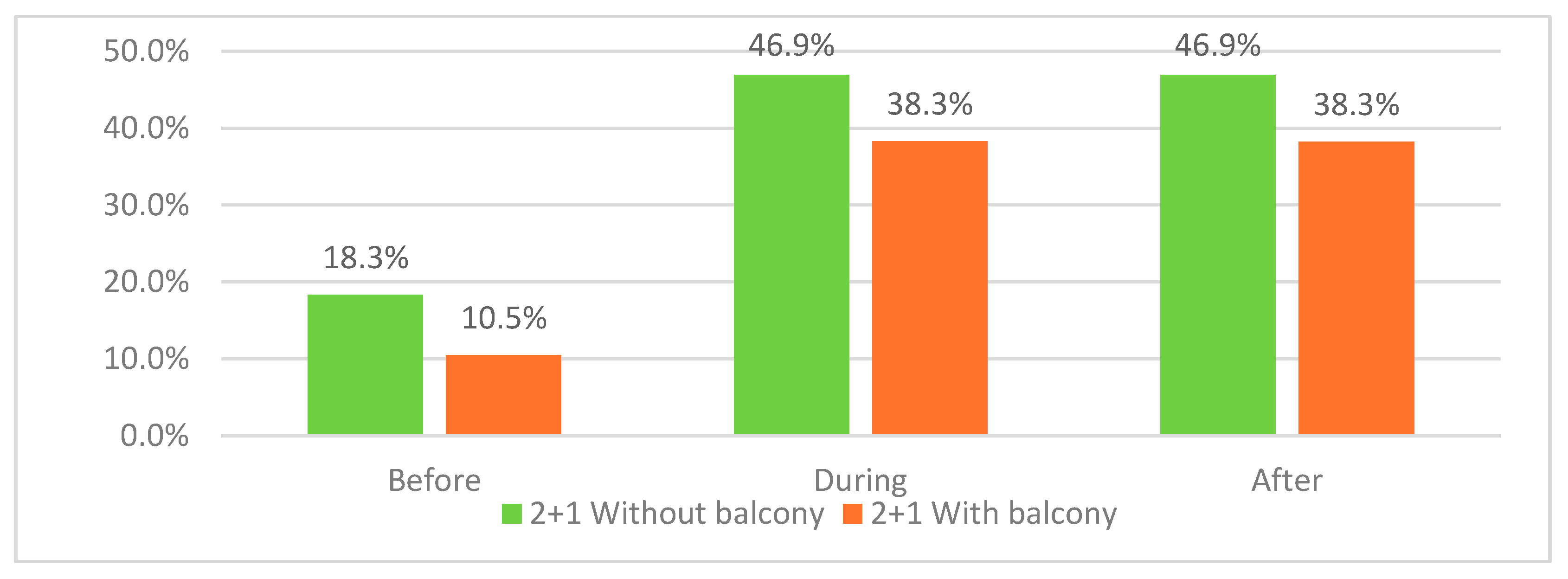

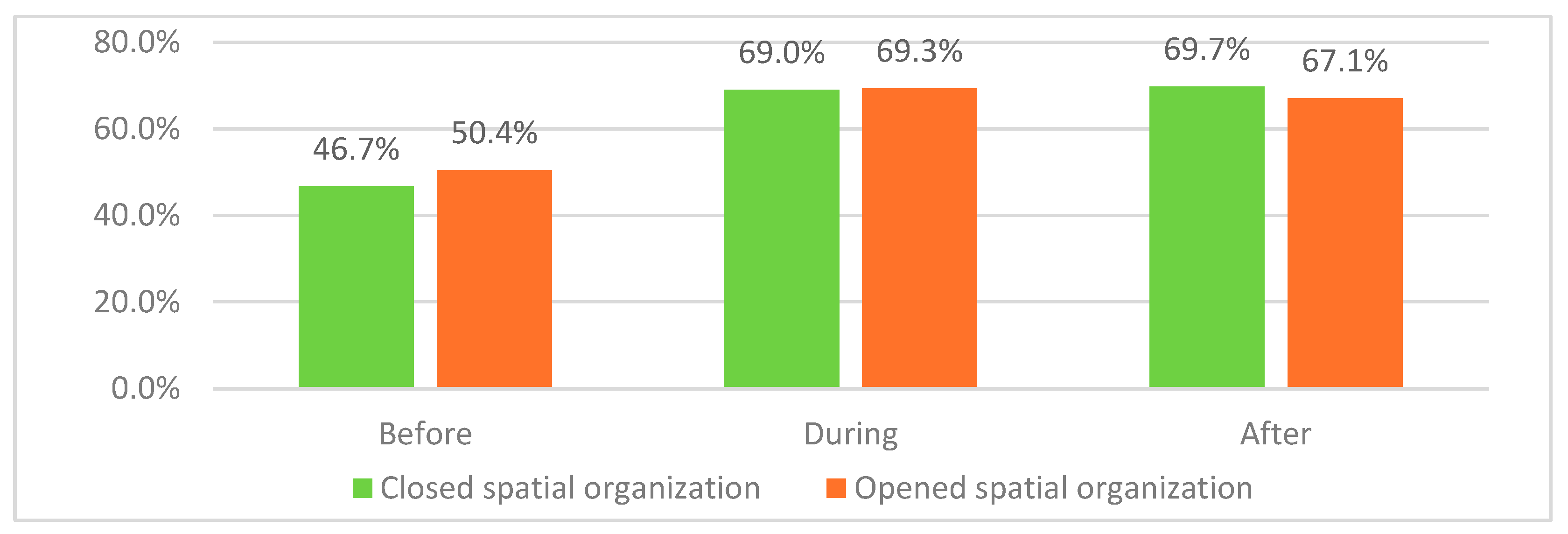

Living room satisfaction was significantly affected by spatial organization and privacy needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dissatisfaction increased notably in living rooms due to limited area and narrow space, especially in closed spatial organizations. This was intensified by the pandemic’s restrictions, which heightened the need for privacy and adequate space. These findings go in line with the findings from Yang et al. [

23] who explored satisfaction and residential demand during COVID-19 pandemic and found out that space and area of living rooms are crucial during situations like the pandemic and claims that since activities would more likely be transformed into such as spaces, they have to be designed optimally in relation to space and functions per the residential demands in the long run. Interestingly, dissatisfaction decreased during the pandemic due to a reduced need for gathering but increased again post-pandemic as normal activities resumed. Smaller dwellings (2+1 configurations) experienced higher dissatisfaction levels compared to larger ones (3+1 configurations), suggesting that space limits played a critical role. Furthermore, the availability of a balcony significantly impacted dissatisfaction levels, with an increase from 6.5% pre-pandemic to 21.4% during and after the pandemic. This suggests that balconies became more valued as extensions of living space, providing necessary relief and a connection to the outdoors during lockdowns. The findings are supported by Duarte et al.’s [

24] research on home balconies during COVID-19 who found out balconies to be resident’s primary means of connecting with outdoor spaces during COVID-19 restrictions and enable the residents to perform various activities there and it significantly enhance mental and physical well-being. Both closed and open spatial organizations saw different dissatisfaction impacts related to the availability of balconies, with closed systems benefiting more post-pandemic. These findings highlight the need for future living room designs to consider factors such as space proportion, privacy, and the integration of elements like balconies to enhance resident satisfaction, especially in light of potential future lockdowns and restrictions similar to those of COVID-19.

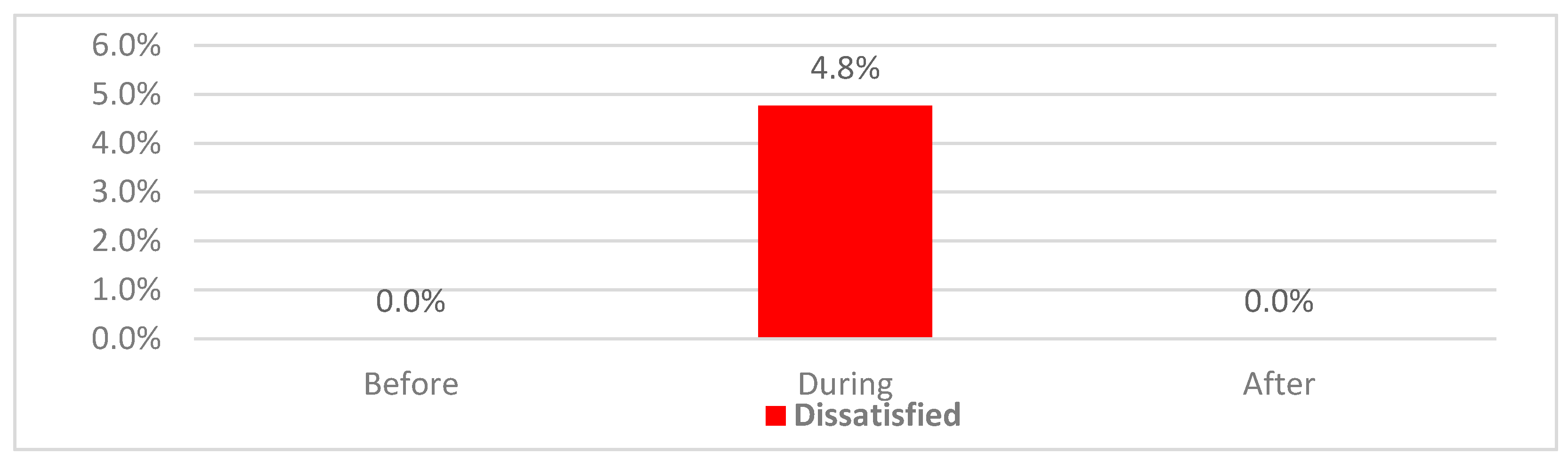

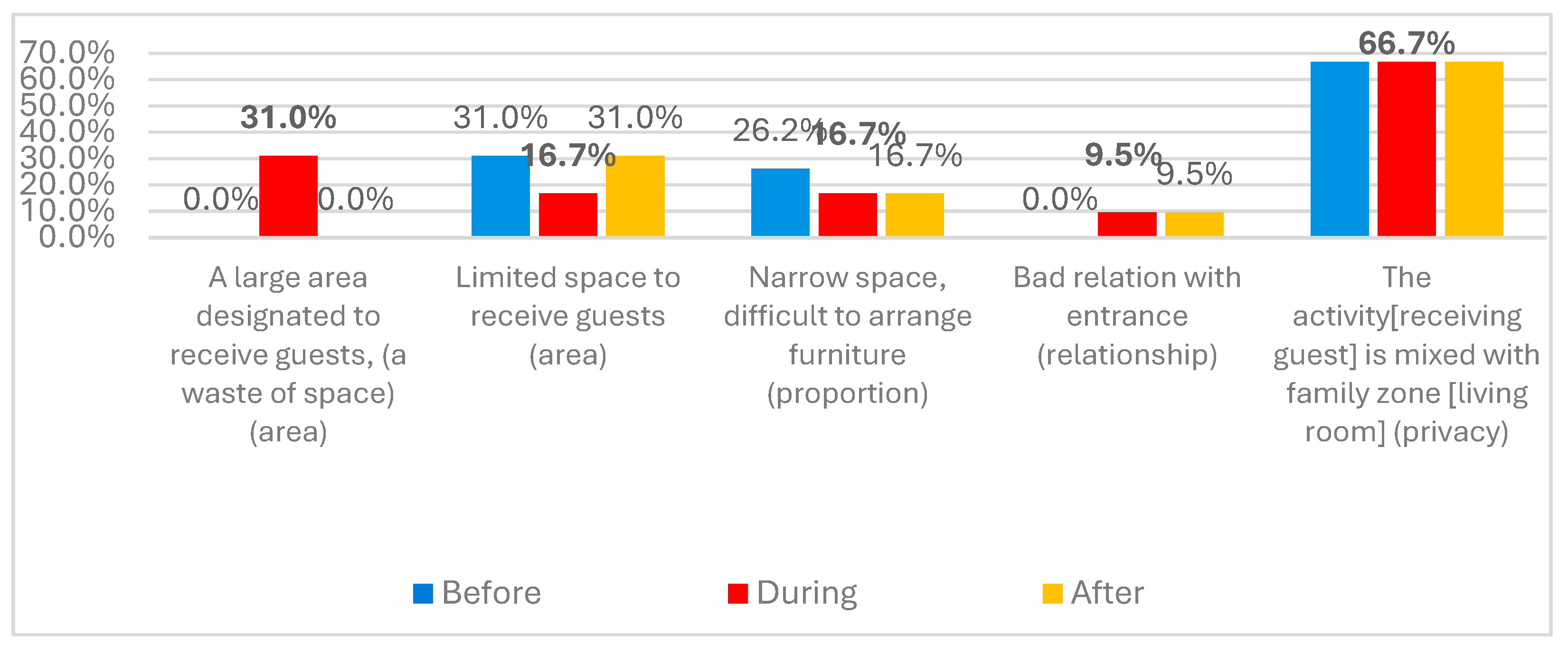

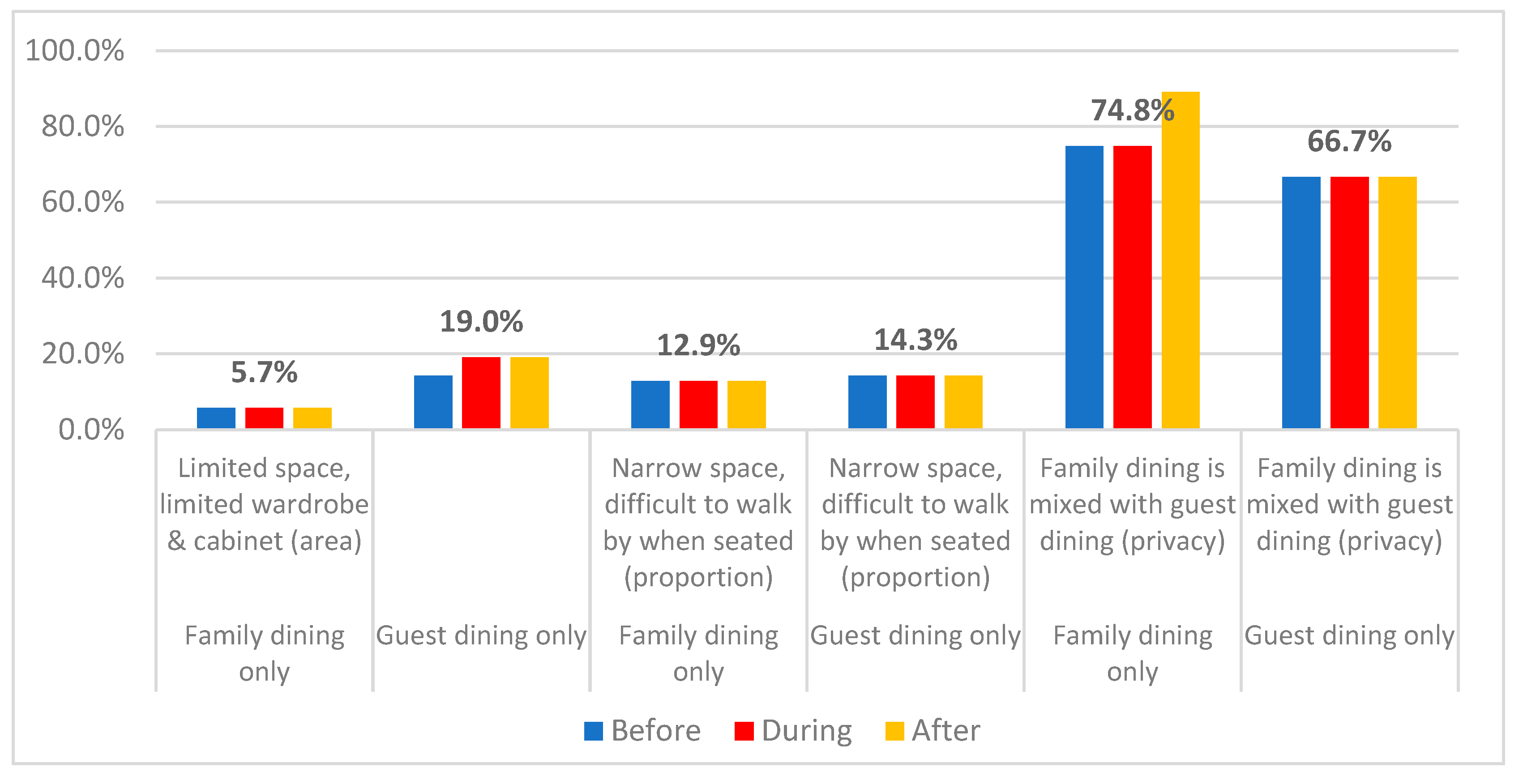

The presence of a dedicated reception room impacted resident satisfaction both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Initially, dissatisfaction between dwellings with and without reception rooms increased from 8.3% pre-pandemic to 12.5% during the pandemic. This increase is attributed to the adaptation of reception areas for study, recreational activities, and isolation due to the lack of visitors and social distancing measures. Post-pandemic, this dissatisfaction gap narrowed back to 8.2% as traditional uses of reception rooms resumed. The multifunctional use of the space, rather than visitor frequency, primarily drove dissatisfaction during the pandemic. Residences raised privacy concerns across all the three stages with dissatisfaction rates reach 66.7% which stemmed primarily due the mixing of the family living room and guest reception area. The findings call for better arrangements in designing receptions considering the residential privacy needs.

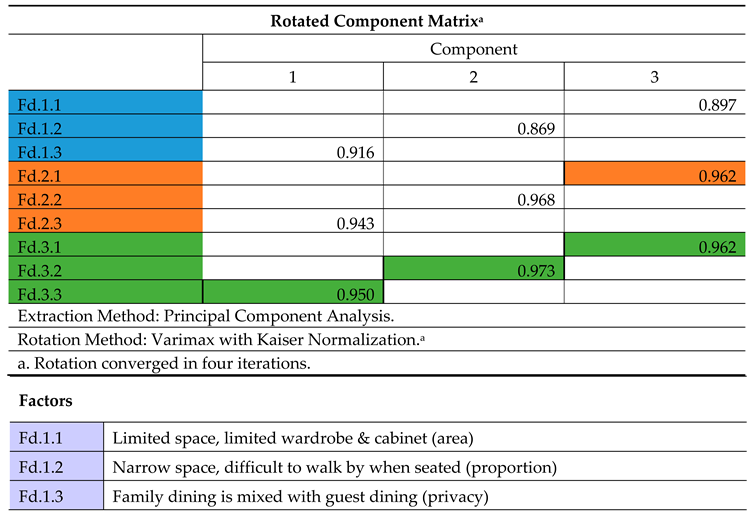

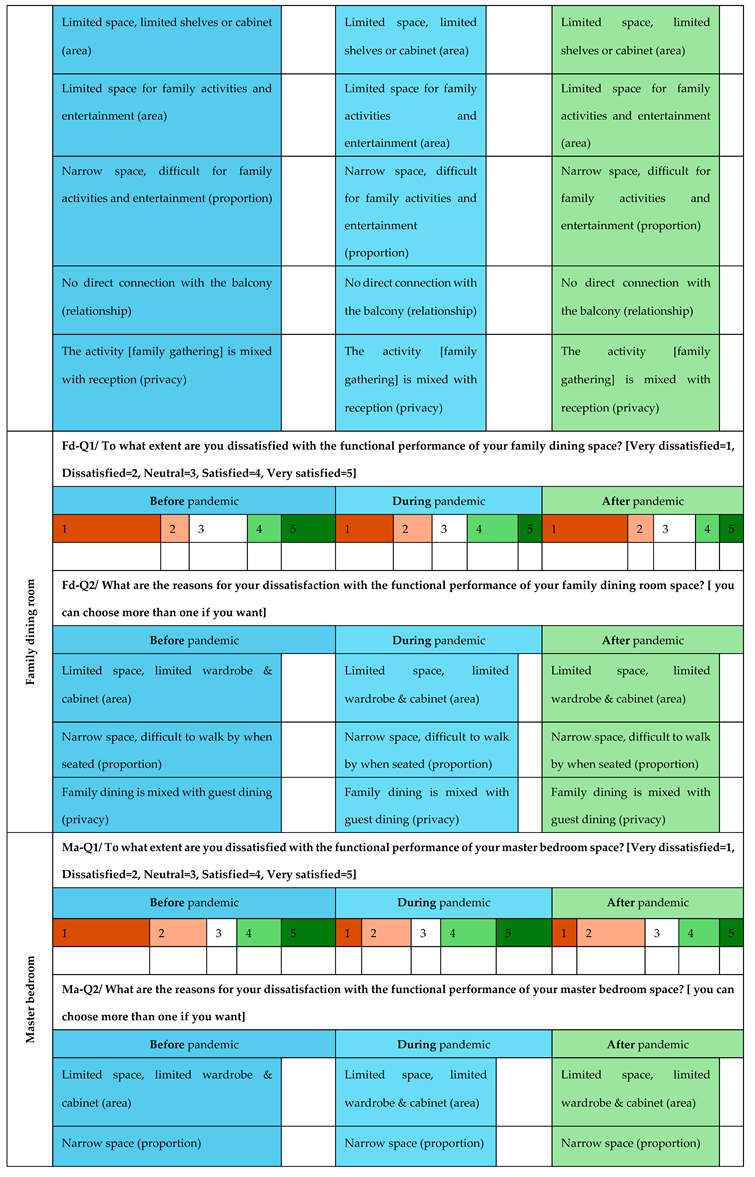

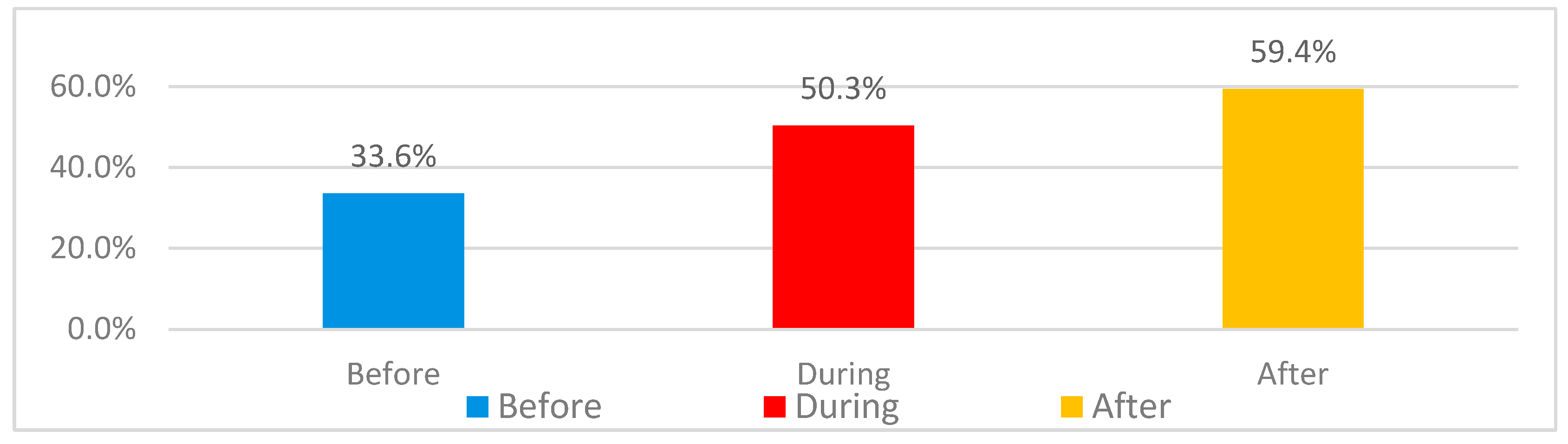

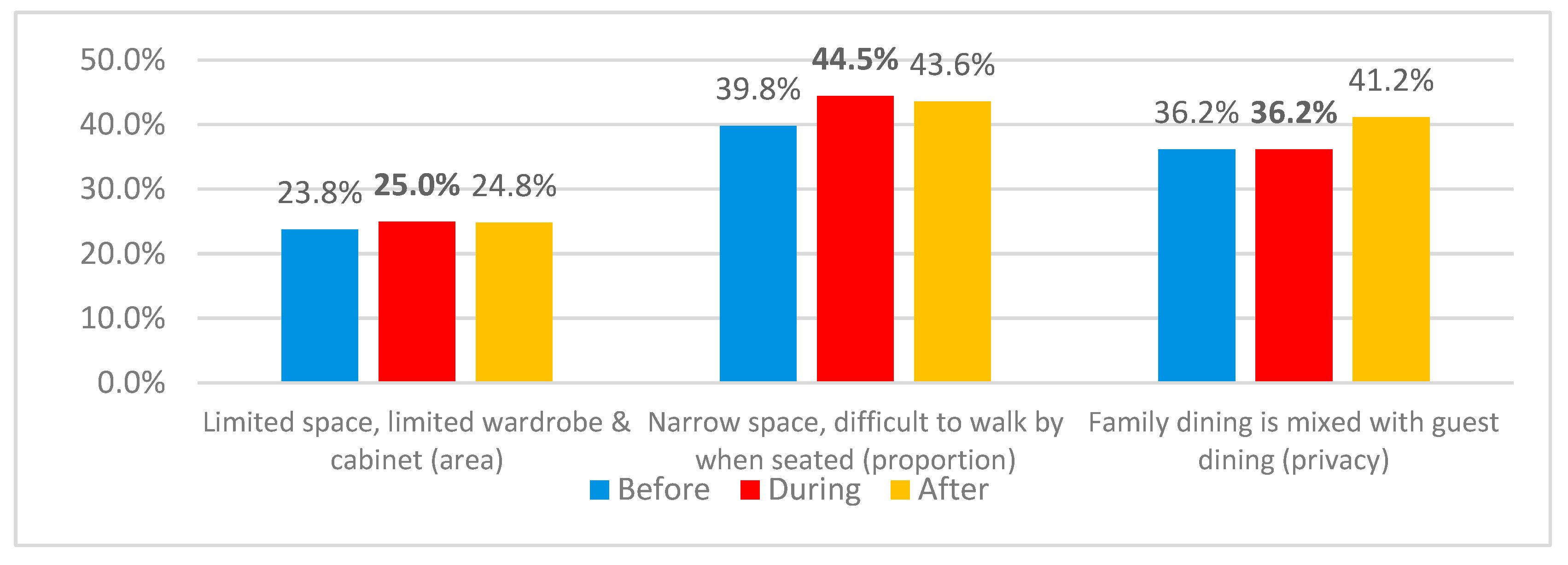

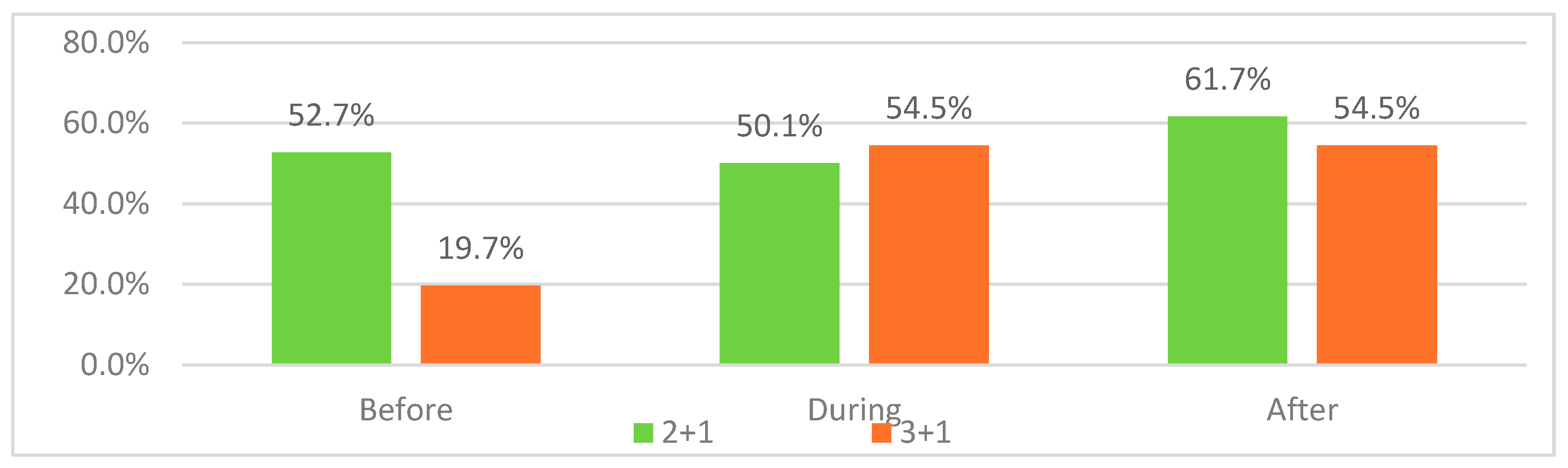

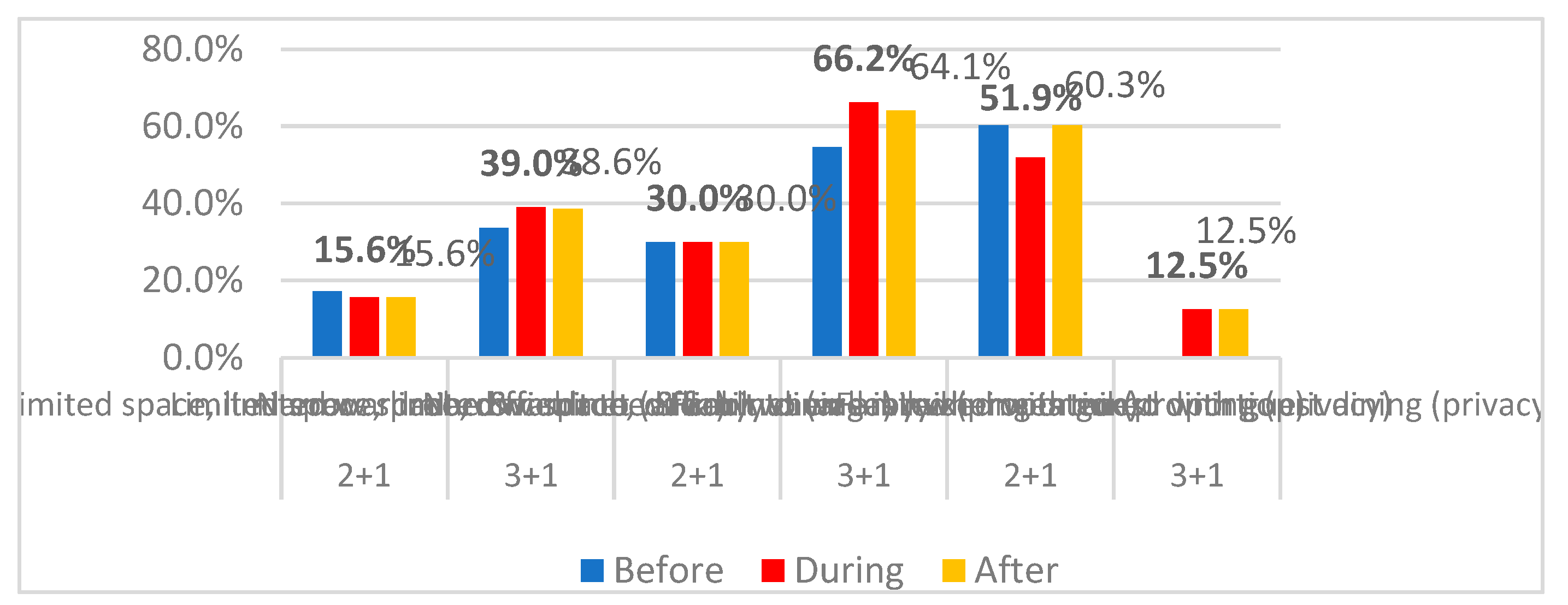

Family dining spaces which were the main gathering areas for family members before the pandemic experienced a significant dissatisfaction during and after the pandemic 50.3% and 59.4% respectively compared the time before the pandemic which was only 33.6%. findings indicate that residents were primarily dissatisfied with the narrow space of the dining areas and felt difficulty in passing through them when seated and maxing it with guest dining increased dissatisfaction of the residents due to privacy concerns. Dissatisfaction was observed with close values in both 2+1 and 3+1 apartment configurations 50.1% and 54.5% respectively during the pandemic while increasing to 61.7% after the pandemic in small apartments suggesting residents changed needs and reconsideration for more adequate designs considering better spacing and having separate dining spaces for family members and guests. The results go parallels with the findings from other studies [

25,

26] calling for thoughtful design consideration in designing dining spaces considering residential privacy concerns especially in smaller apartments.

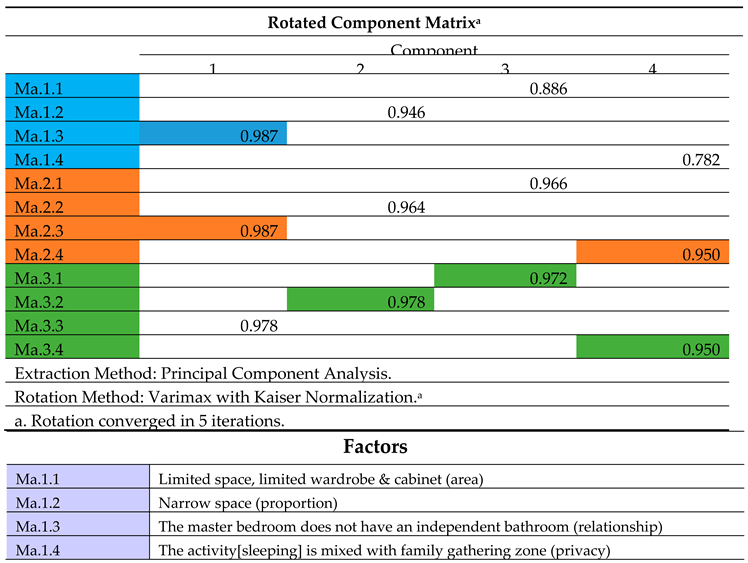

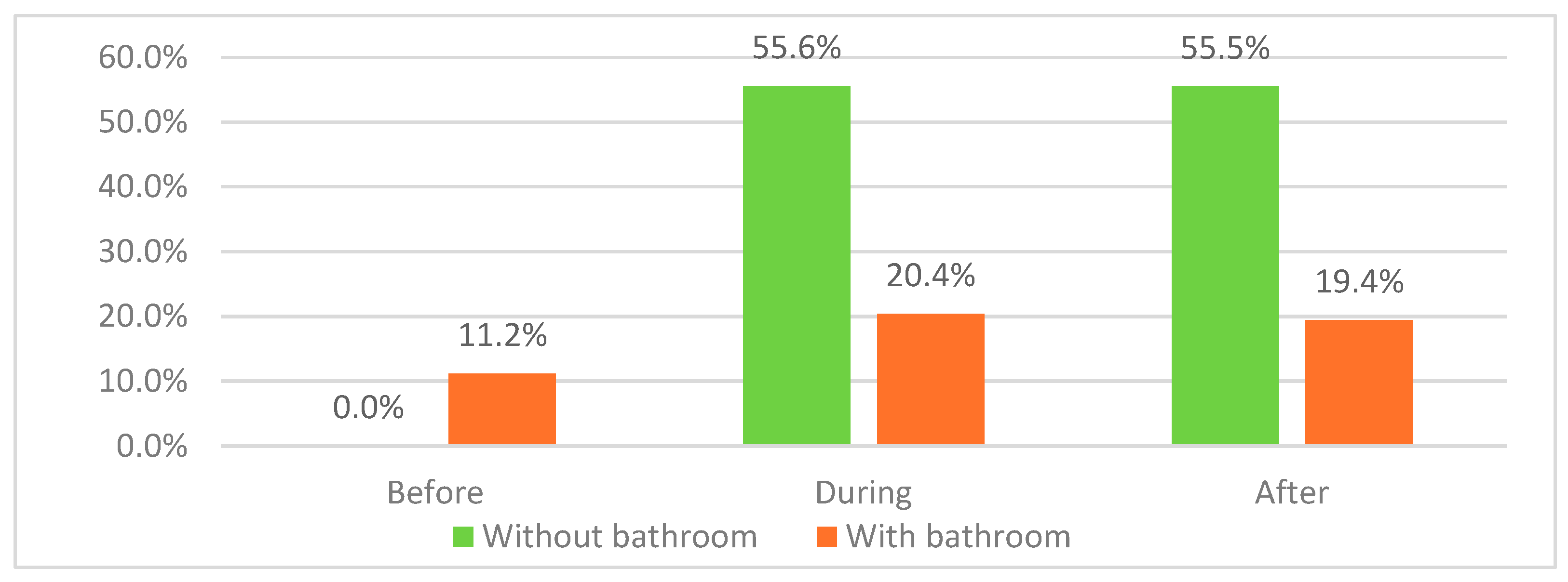

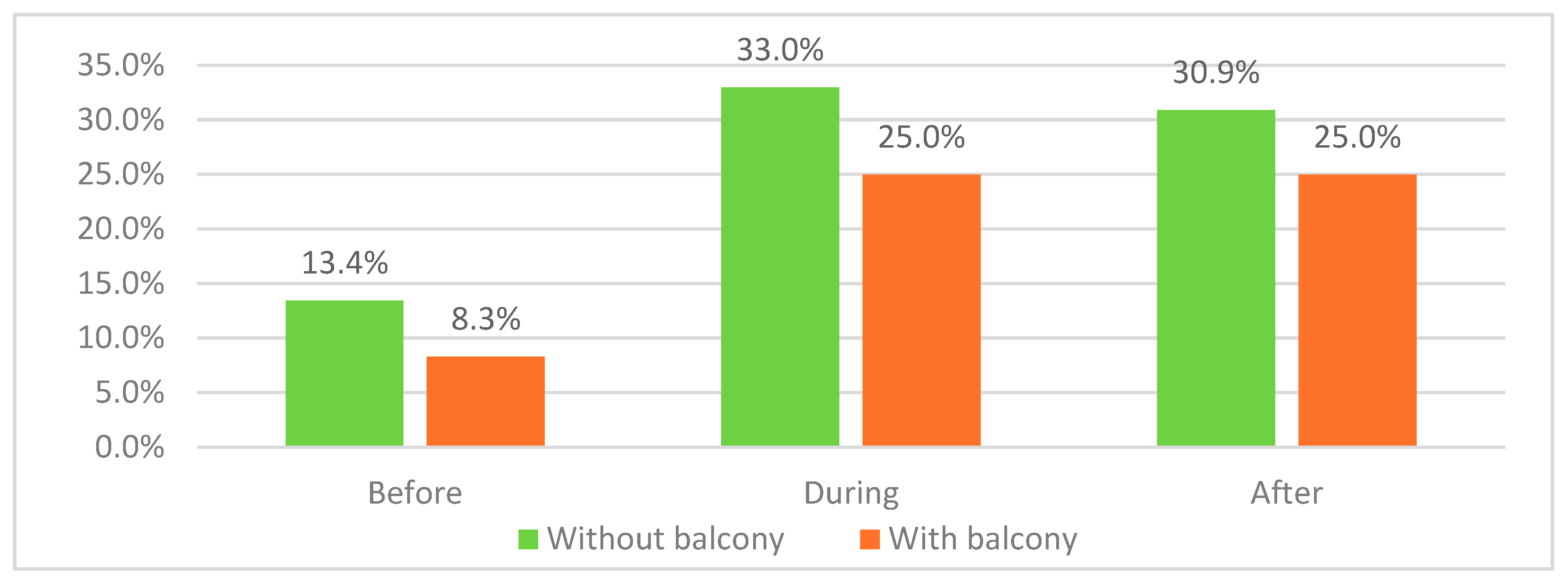

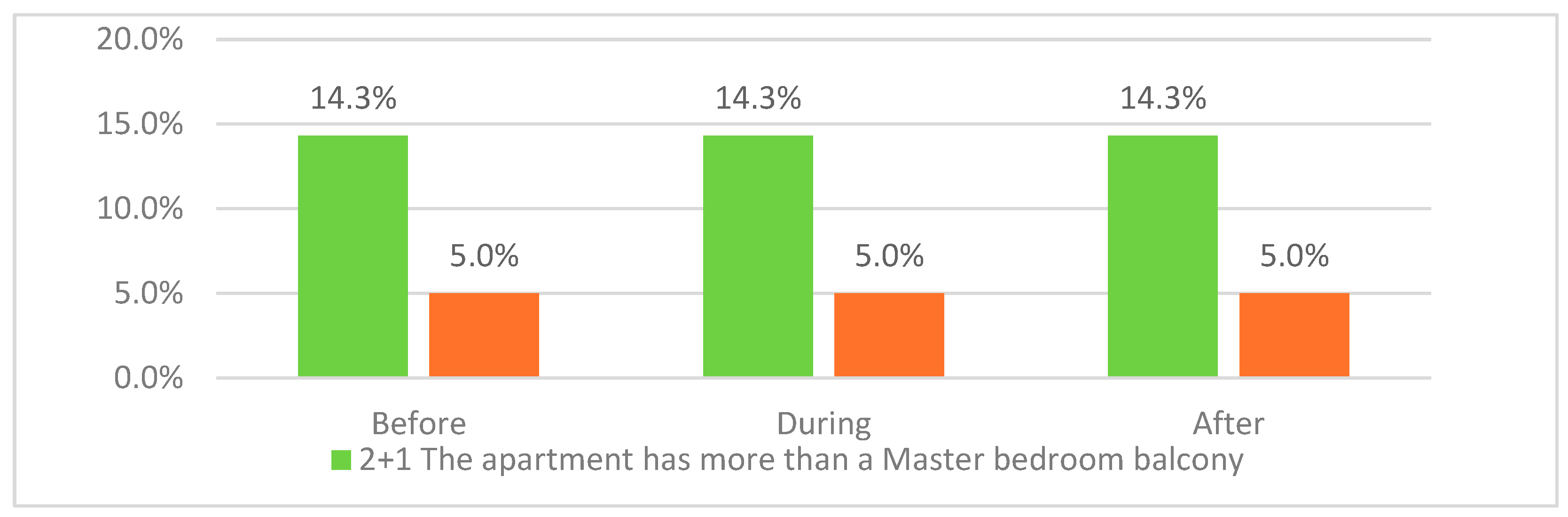

Master bedrooms being the primary resting place of the apartment heads observed significant dissatisfaction with larger apartment categories observing lesser dissatisfaction compared to the smaller ones across all stages. The lack of a private bathrooms in the master bedroom served to be the primary factor behind the high dissatisfaction levels during the pandemic it can be particularly attributed to the fact that the pandemic increased the need for private spaces. Primary factors leading the reduced dissatisfaction levels in the master bedroom was found to be the presence of balconies through which residents were able to get a view of outside and practice several different activities there. Duarte et al. [

24] and Yang et al. [

23] both support the fact that the presence of balconies and bathrooms within master bedrooms are essential criterions affecting the satisfaction of residents. These findings suggest the critical need for well-designed master bedrooms with adequate space, privacy, and essential amenities like bathrooms and balconies to enhance resident satisfaction, particularly in compact living conditions.

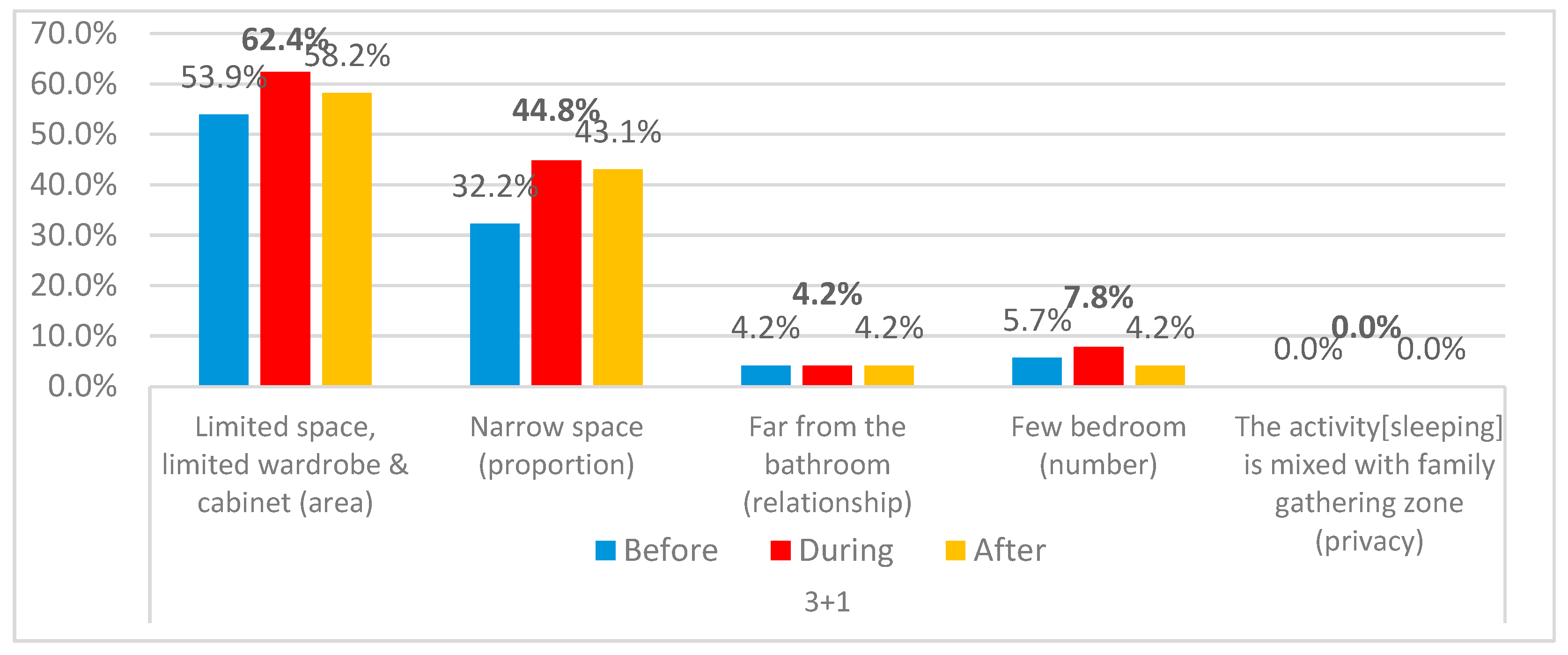

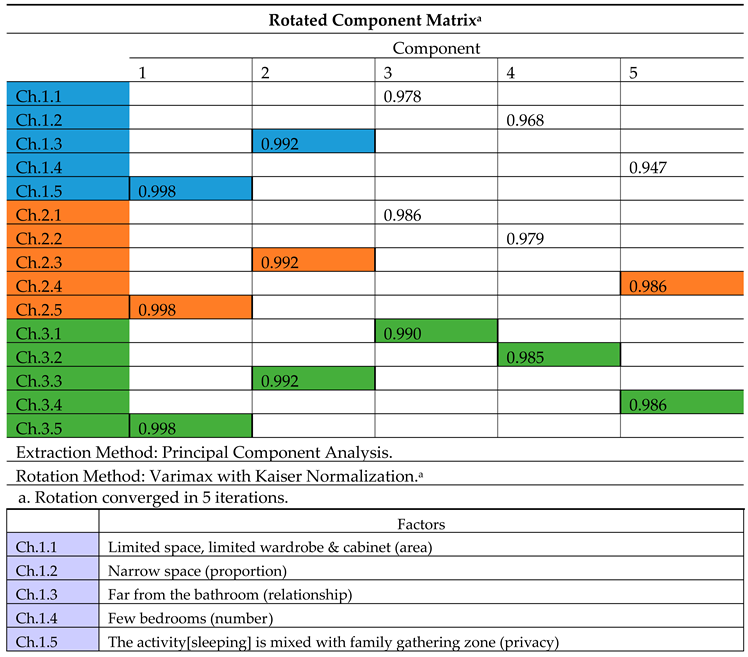

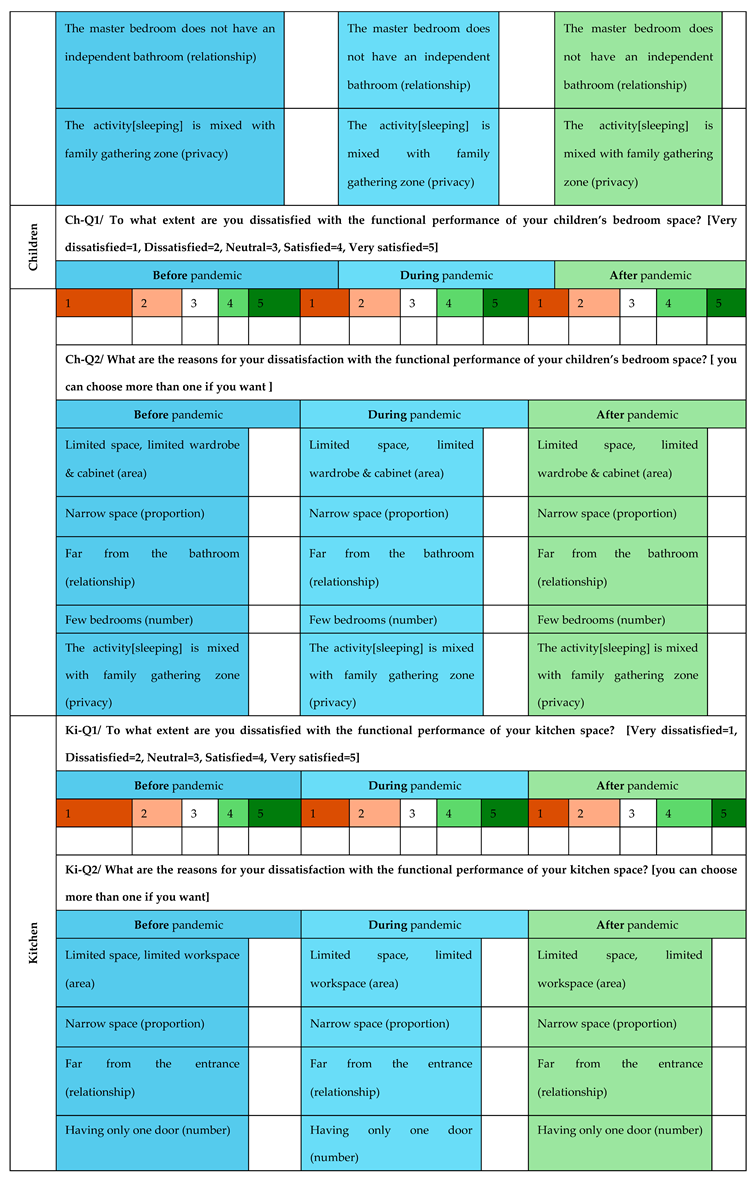

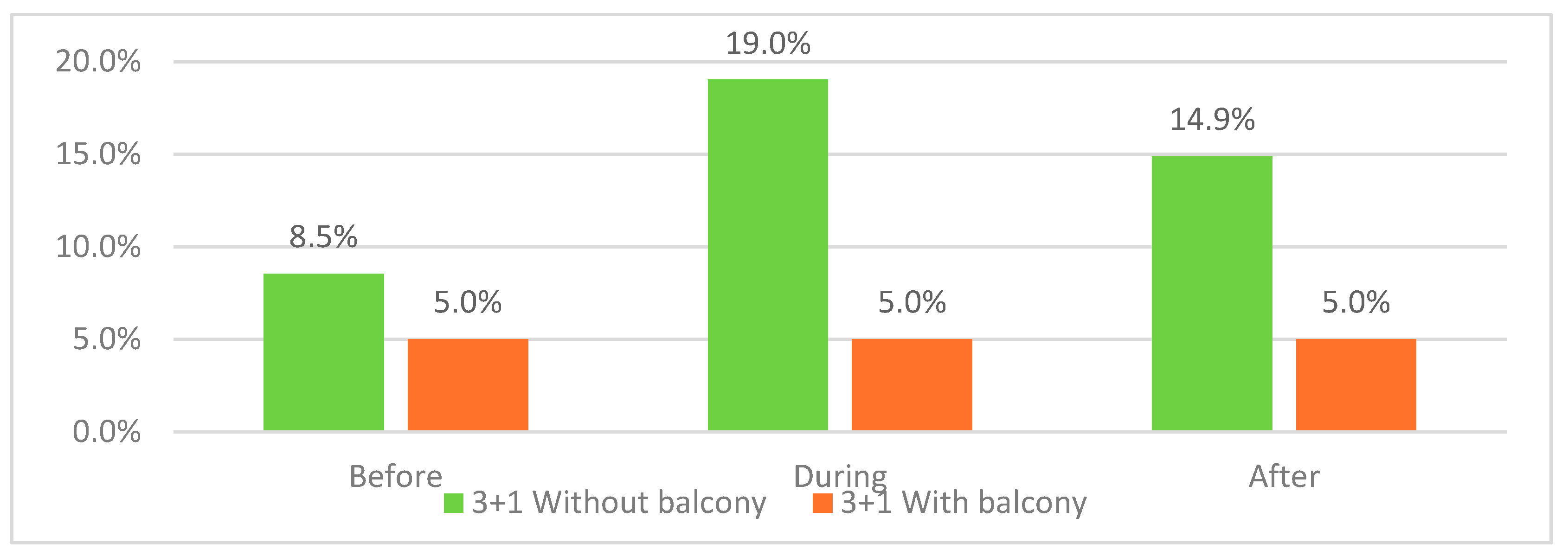

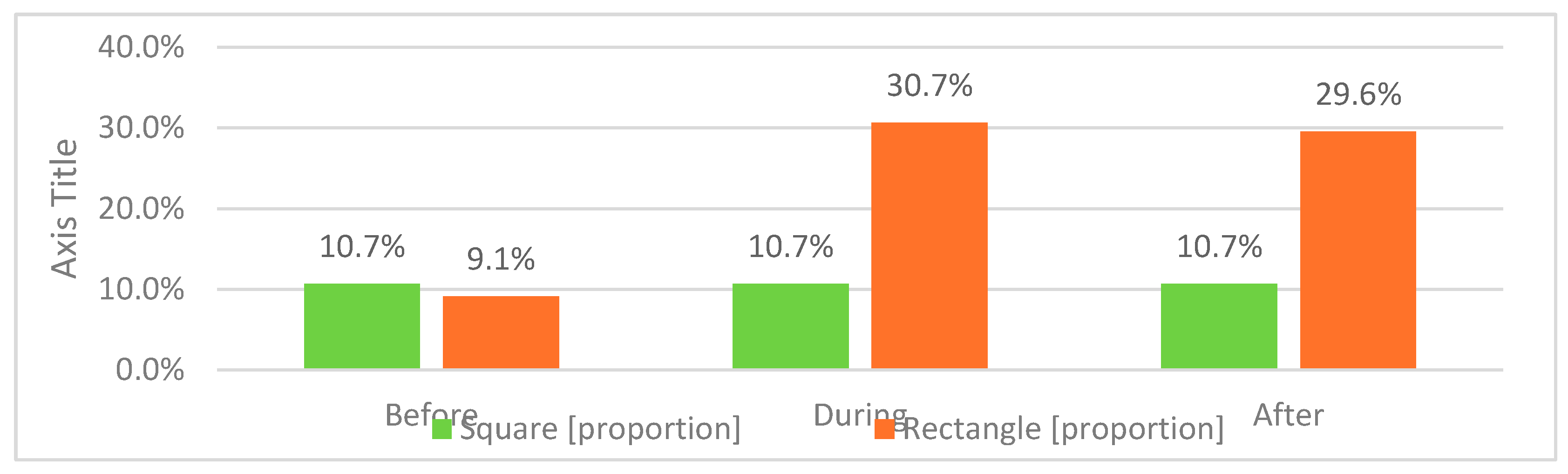

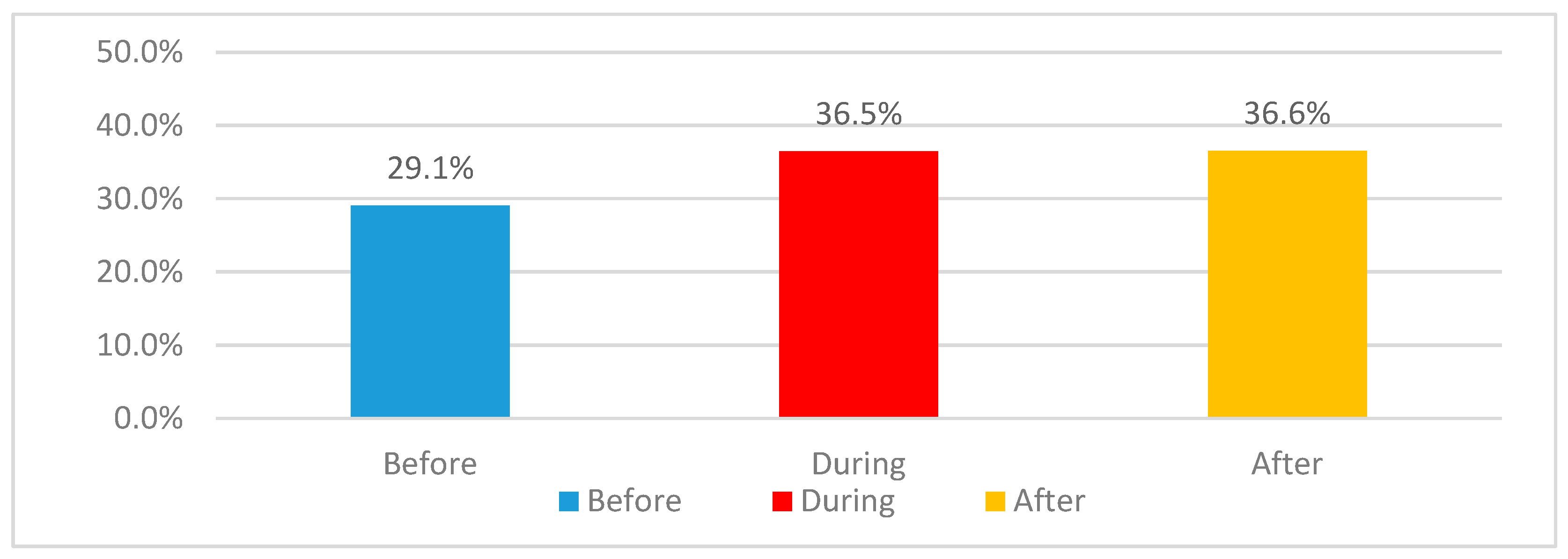

Children bedroom due to their multipurpose uses along being resting place also serving as a study room observed dissatisfaction rates increasing from 29.1% to 36.5%. As the small increase in the dissatisfaction rate shows smaller increase compared to other spaces in which dissatisfaction rates were increased more than 25% and increasing more in smaller apartment configuration compared to larger ones.The main reasons for dissatisfaction were limited space and inadequate room proportions, particularly in 3+1 apartments, where space deficits were cited by 53.9%-58.2% of respondents. Additionally, rectangular room shapes received more negative feedback than square rooms throughout the pandemic, with dissatisfaction rates for rectangular rooms being substantially higher post-pandemic. The presence of a balcony in children’s bedrooms significantly improved satisfaction during and after the pandemic. Open spatial organization resulted in less dissatisfaction compared to closed layouts, and this trend intensified during and after the pandemic, showing a clear preference for more open living arrangements in children’s bedrooms. The findings from other studies [

27,

28,

29] also highlight the critical role of children bedroom and their effects on residential satisfaction as these spaces were not only used for sleeping and resting alone during the pandemic, rather they were used as study and work spaces as well, hence adequate design considering such unexpected conditions like the COVID-19 pandemic shall be come necessary considerations when designing such spaces in the future.

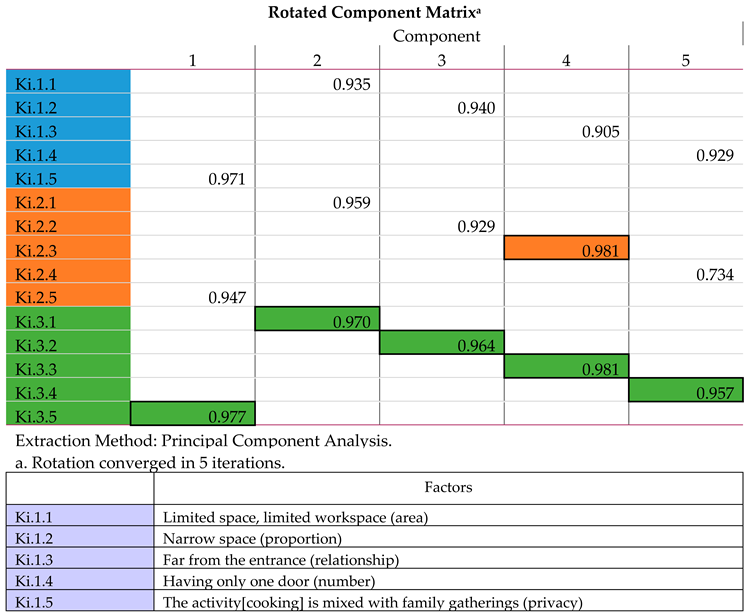

Dissatisfaction with kitchen spaces significantly increased during the pandemic, with a 20.7% rise in dissatisfaction levels, and remained relatively stable afterward with only a minor decrease of 0.6%. This dissatisfaction was primarily due to limited space and narrow proportions of the kitchen, which worsened during the pandemic due to the increased usage of the kitchen for multiple purposes, including family gatherings. The lack of a family dining area within the kitchen also contributed to this dissatisfaction. The study found that smaller apartments (2+1 category) reported higher dissatisfaction compared to larger ones (3+1 category), likely due to more acute space constraints in smaller kitchens. Additionally, the presence of balconies in kitchen areas slightly mitigated dissatisfaction, particularly before the pandemic, but this benefit was less pronounced during and after the pandemic. Other studies highlight that kitchens during the pandemic were merely used for cooking purposes only, rather they were used more of like an office and study rooms [

1,

29] The findings suggest that improving spatial proportions and providing dedicated areas for dining within the kitchen could enhance resident satisfaction, particularly in smaller apartments.

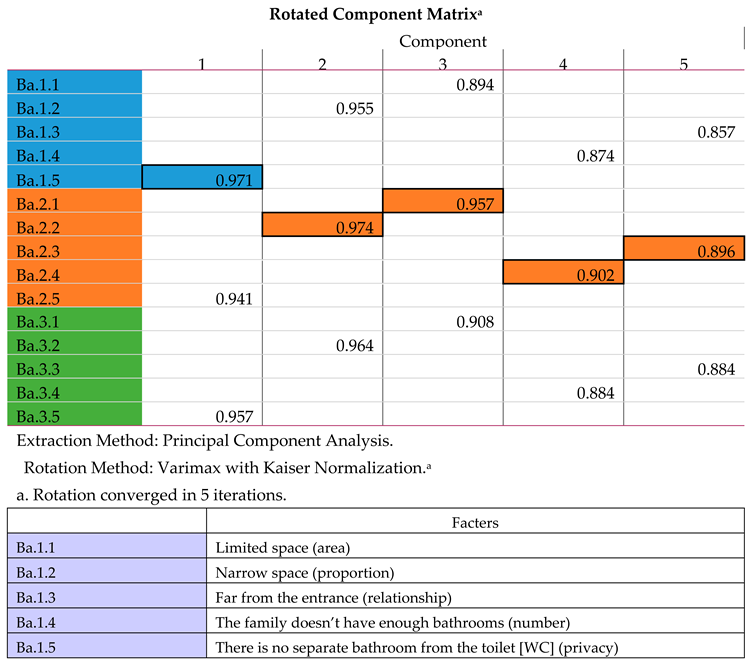

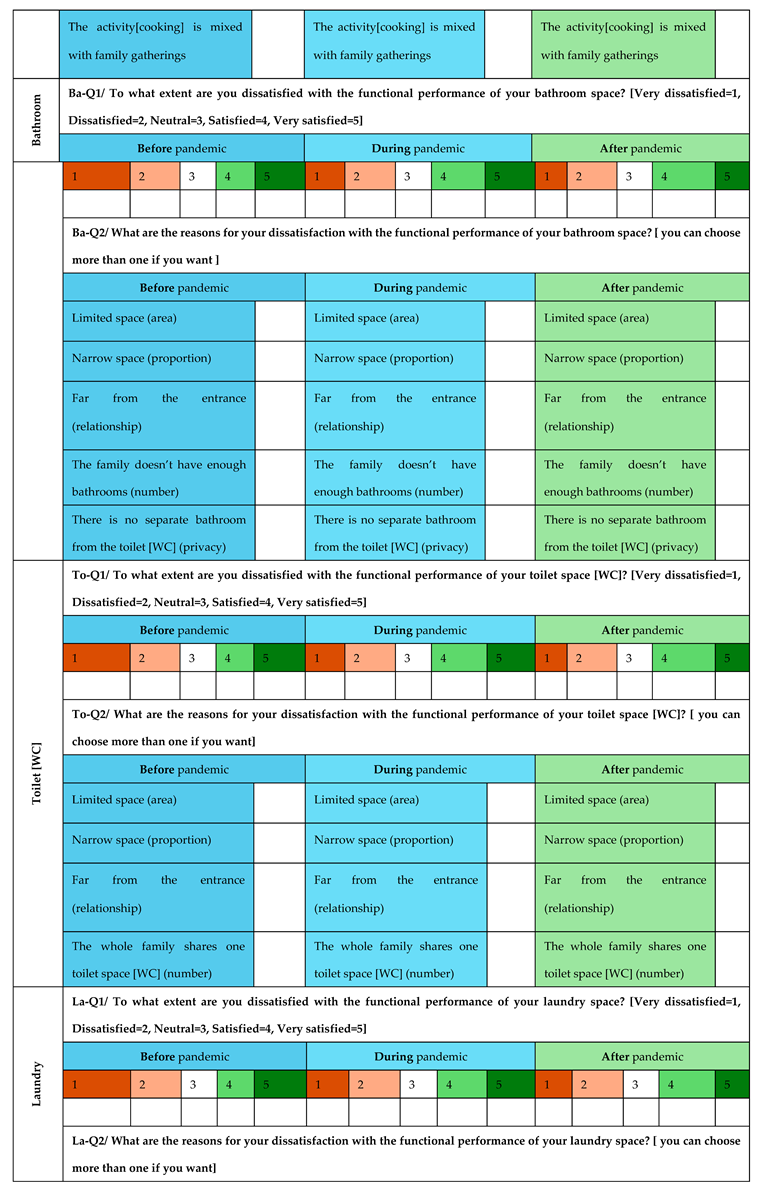

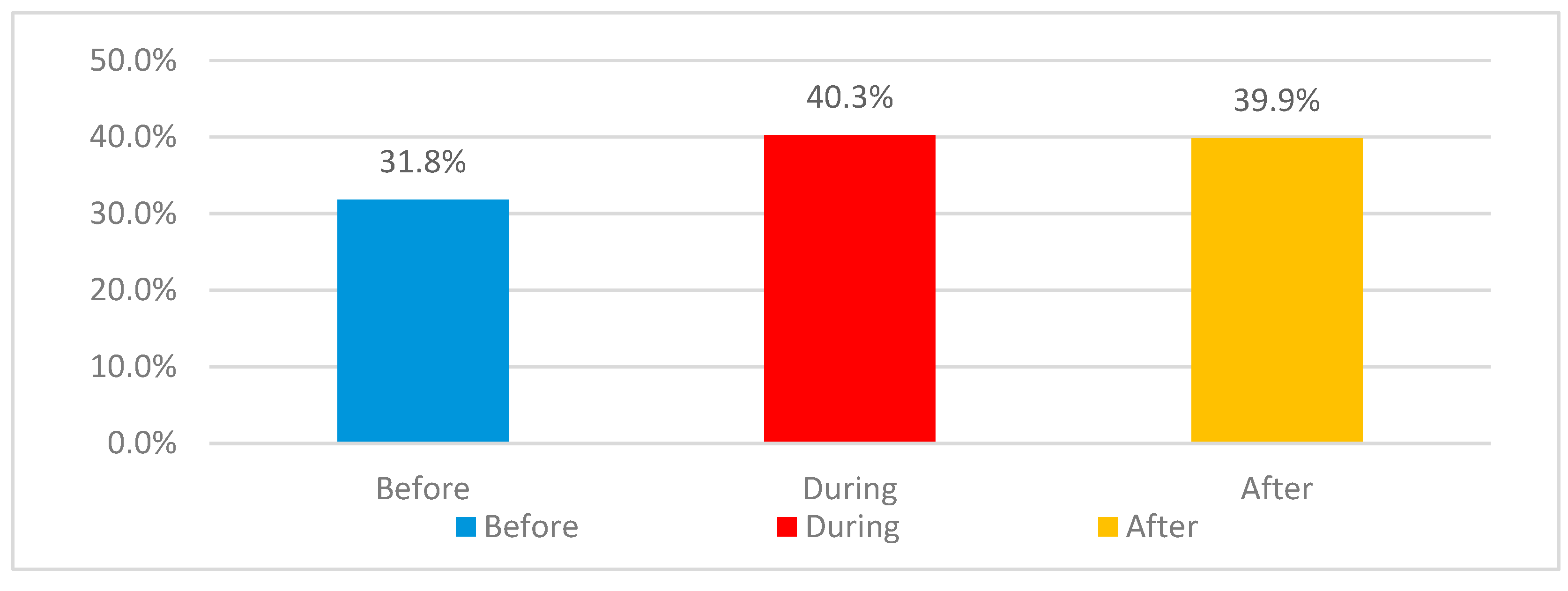

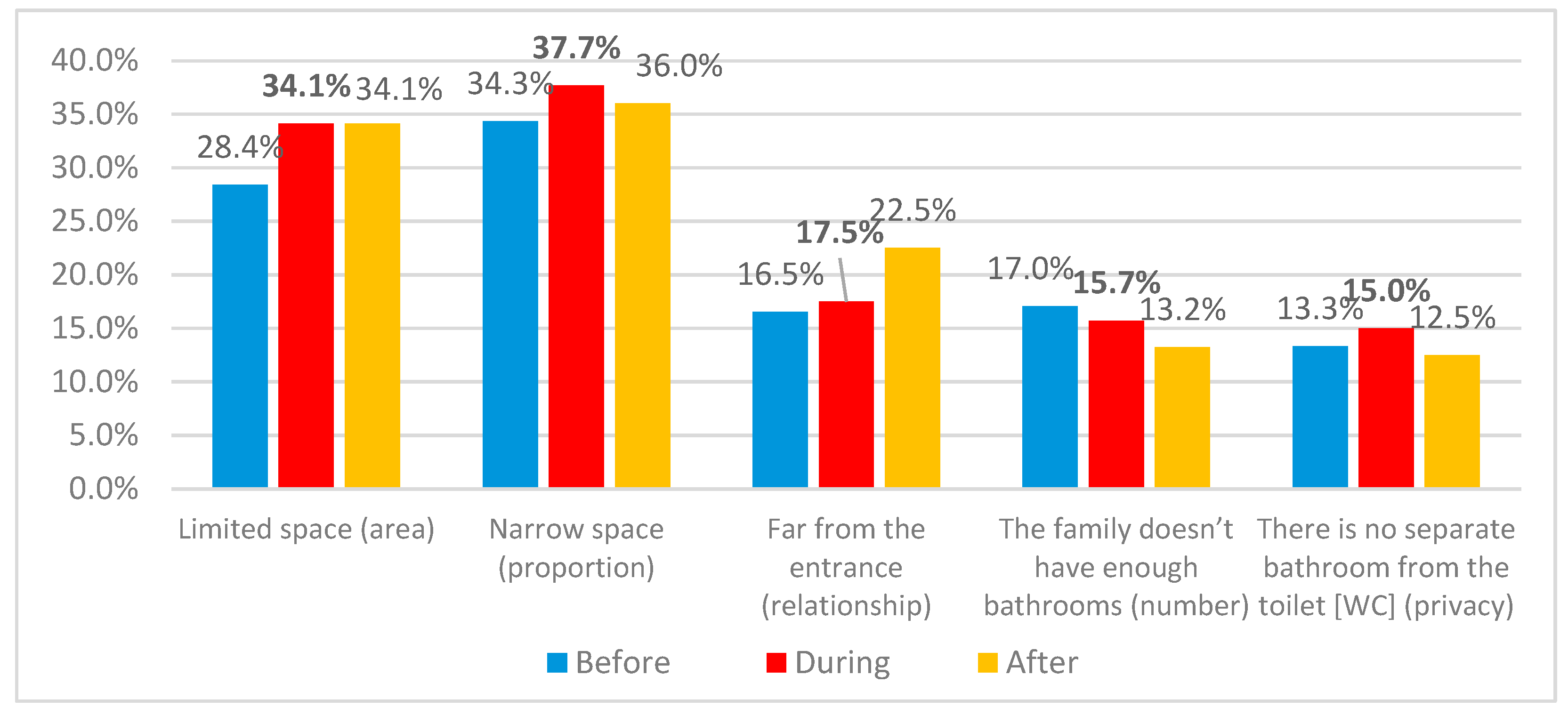

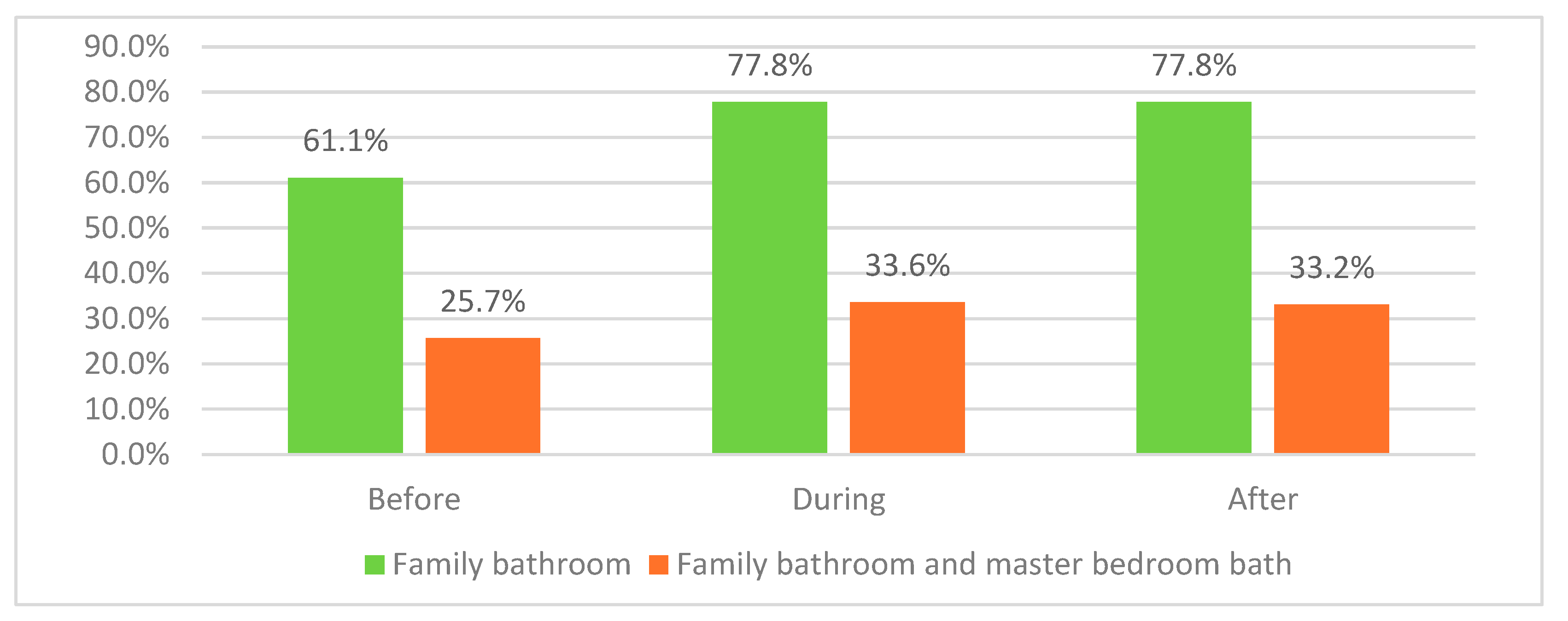

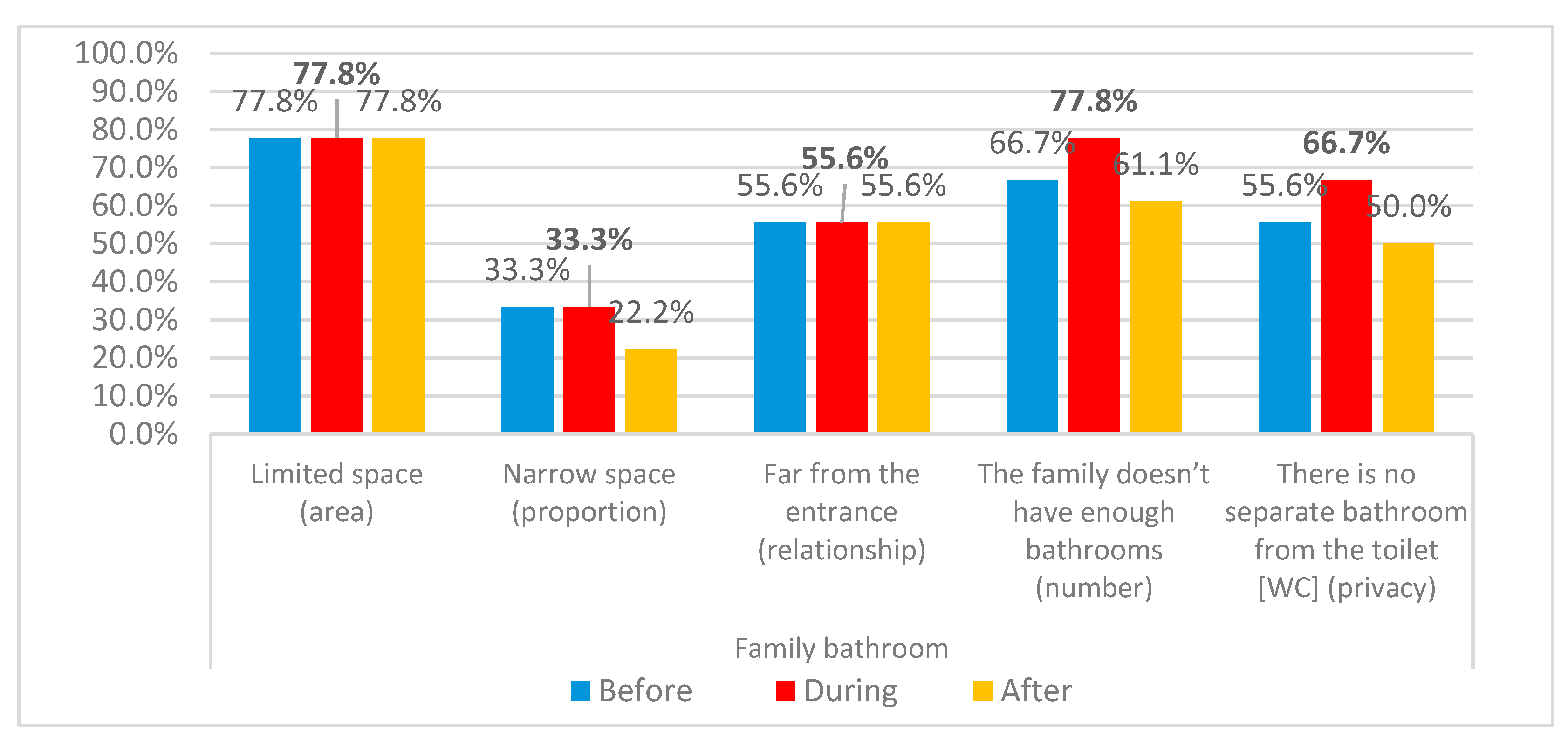

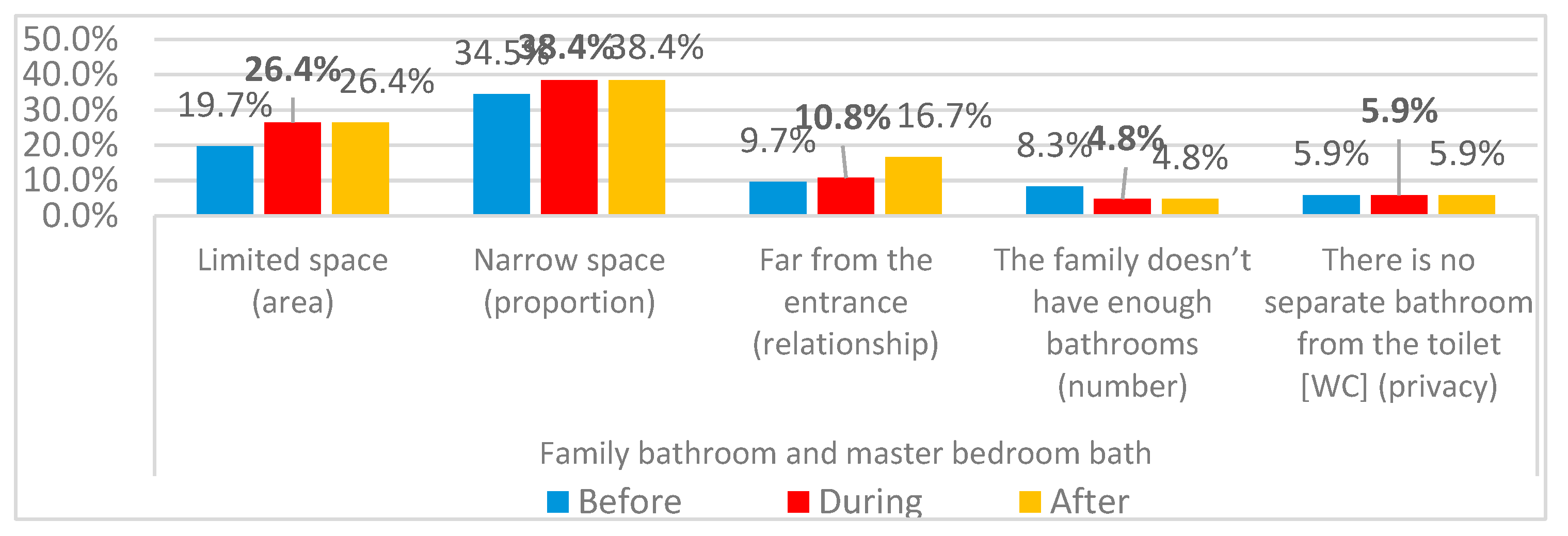

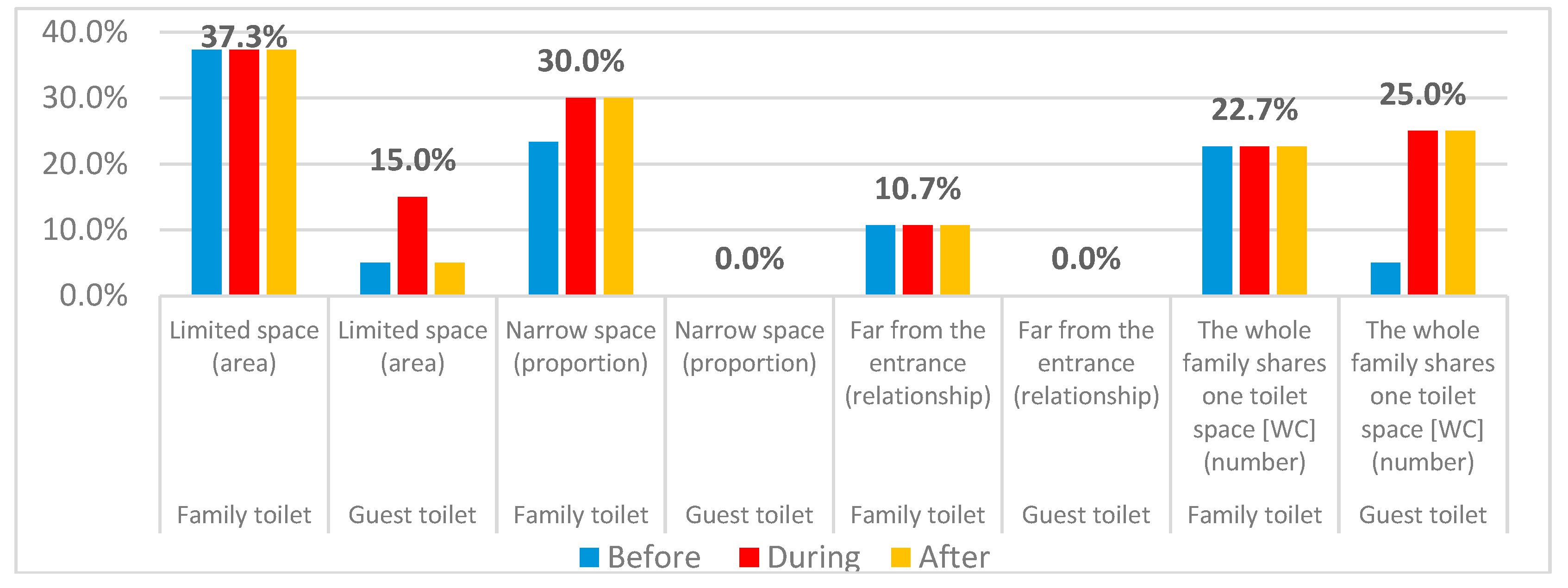

Dissatisfaction with family bathrooms, used commonly by all family members, showed a typical increase during the pandemic, rising by 8.5% from the pre-pandemic stage, then slightly decreasing post-pandemic. Proportion, area sufficiency, and distance from the entrance were identified as the main reasons for dissatisfaction, with proportion showing the highest increase during the pandemic. The presence of an additional master bathroom significantly reduced dissatisfaction, highlighting the benefits of having more than one bathroom in reducing congestion and enhancing privacy. Apartments with both a family and a master bathroom reported markedly lower dissatisfaction levels, emphasizing the importance of multiple bathrooms in larger dwellings (3+1 categories) compared to those with only one bathroom (2+1 categories). The findings are in parallel with findings from Elrayies [

30] and İslamoğlu [

1] who found that bathrooms significantly influenced the satisfaction of residents as they were used more than often for the hygiene purposes and apartments having more than one bathroom showed lesser dissatisfaction compared to smaller ones having a single bathroom. This suggests that adequate bathroom designs are crucial for meeting the needs of residents, particularly in larger households or during periods requiring increased isolation, such as a pandemic.

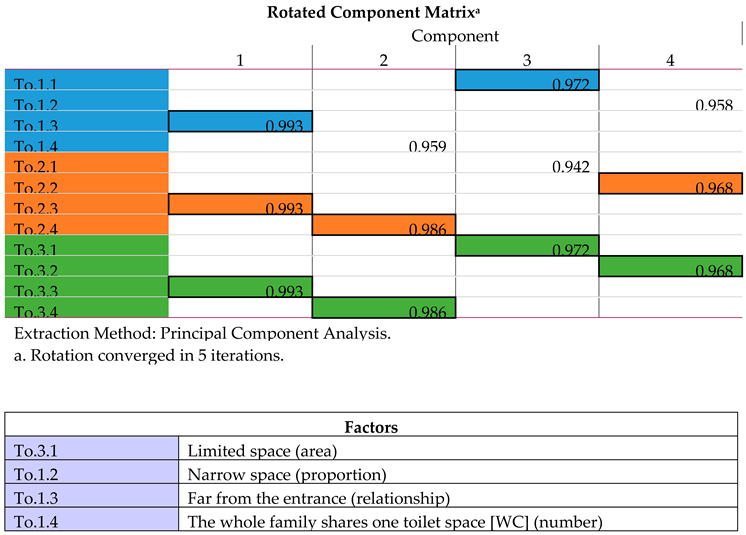

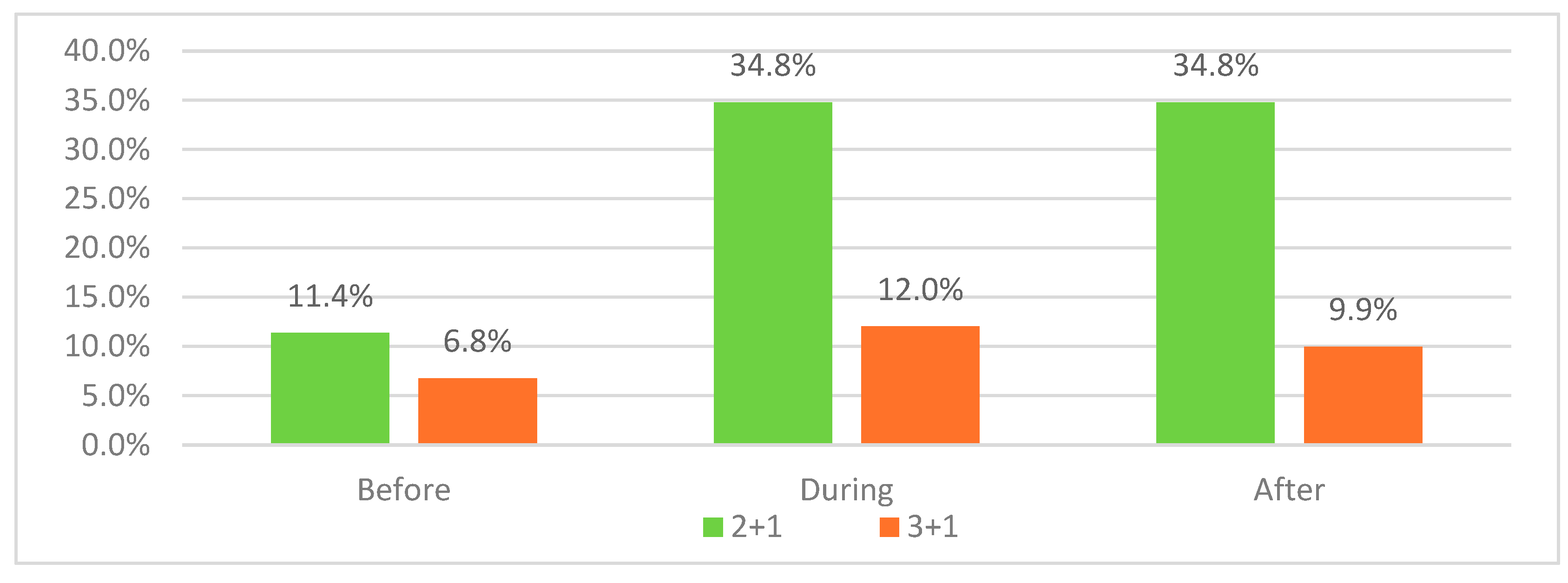

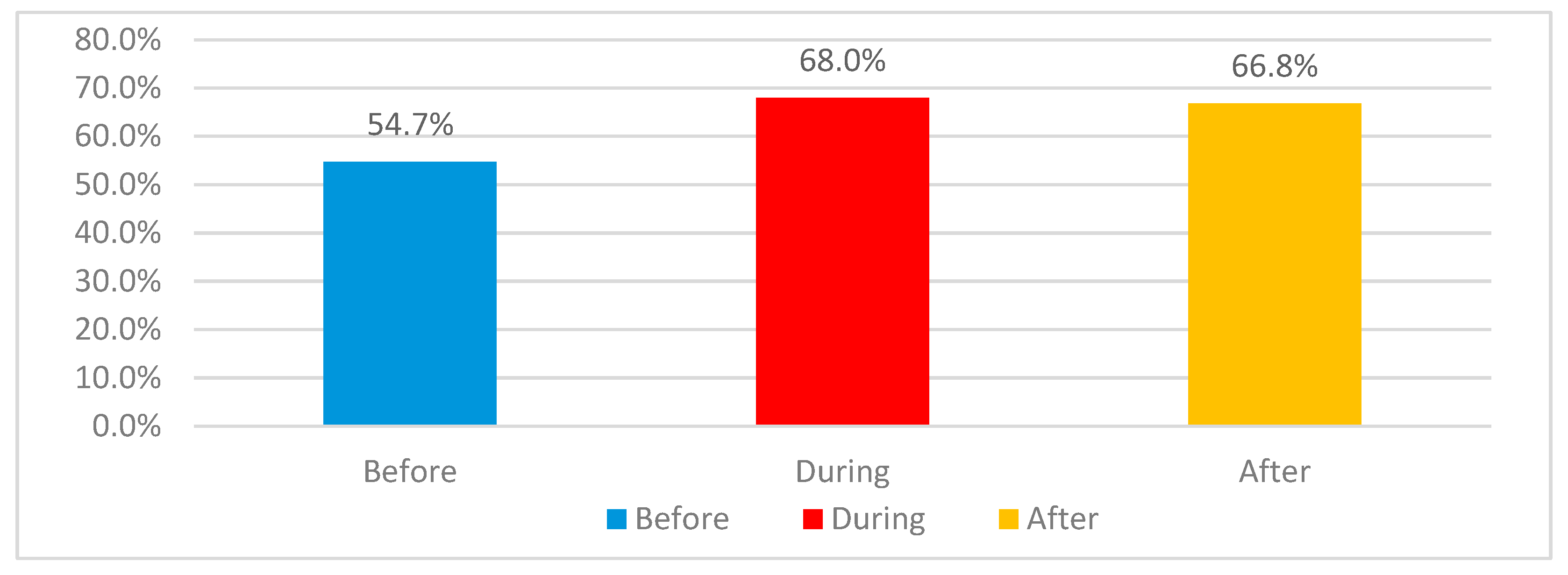

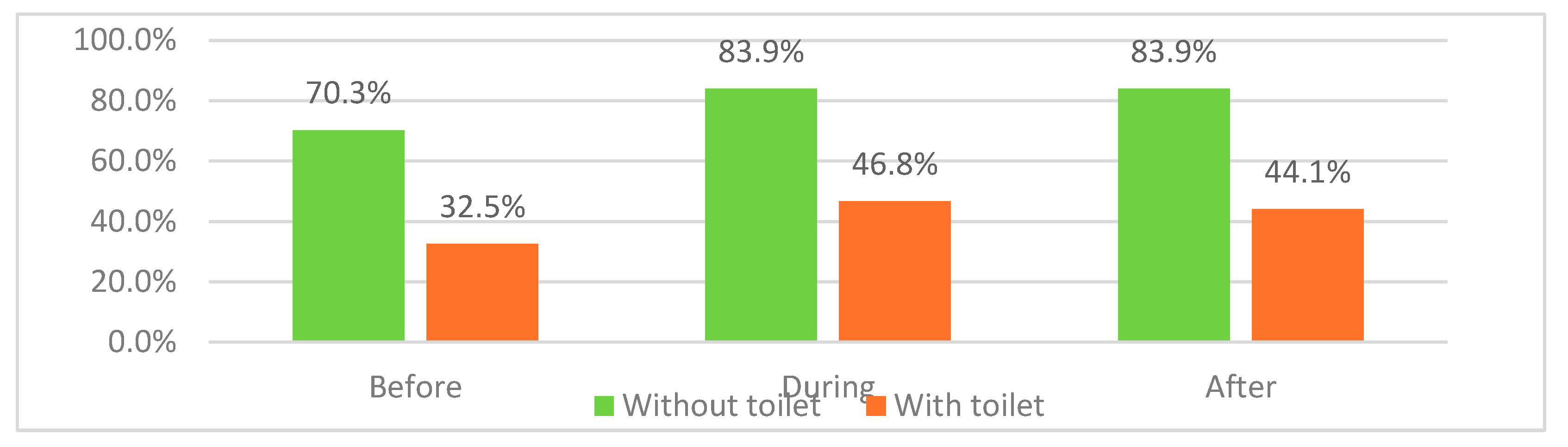

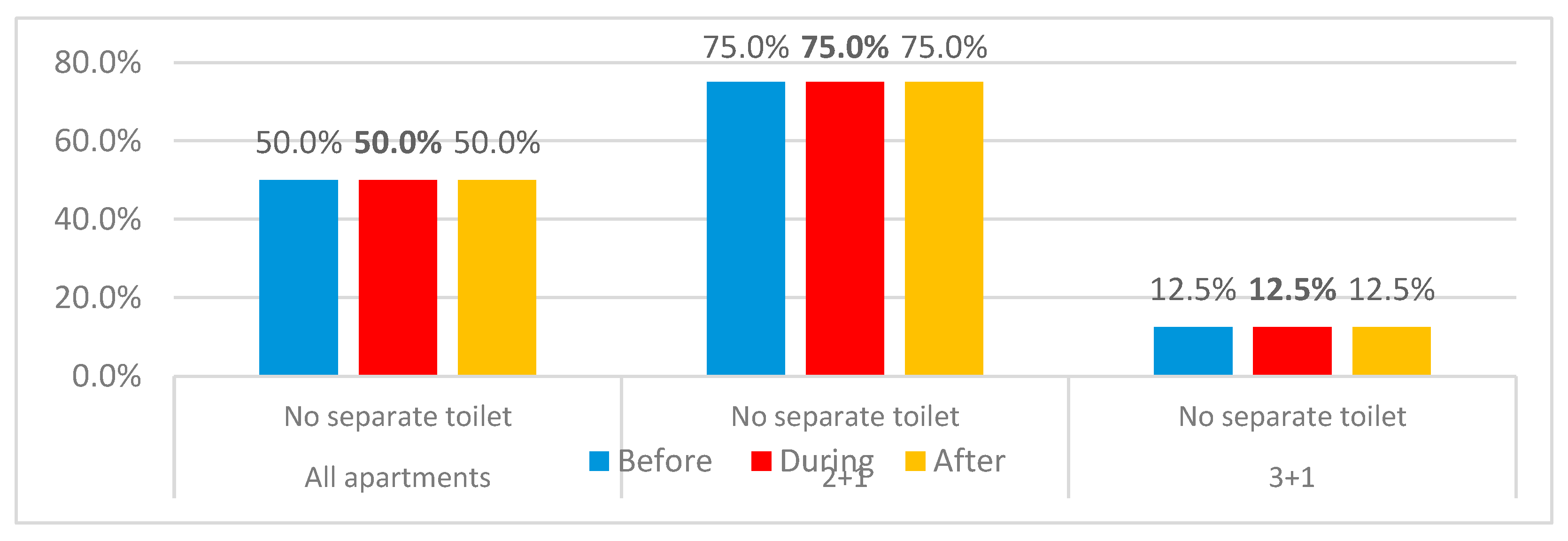

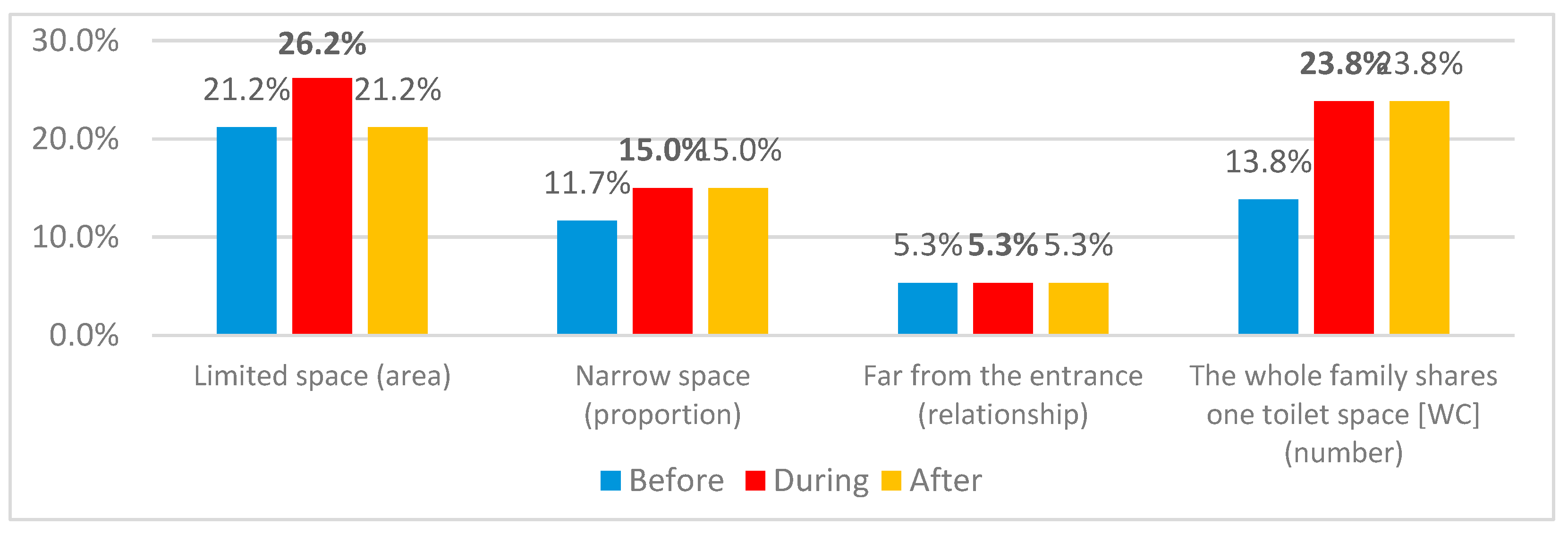

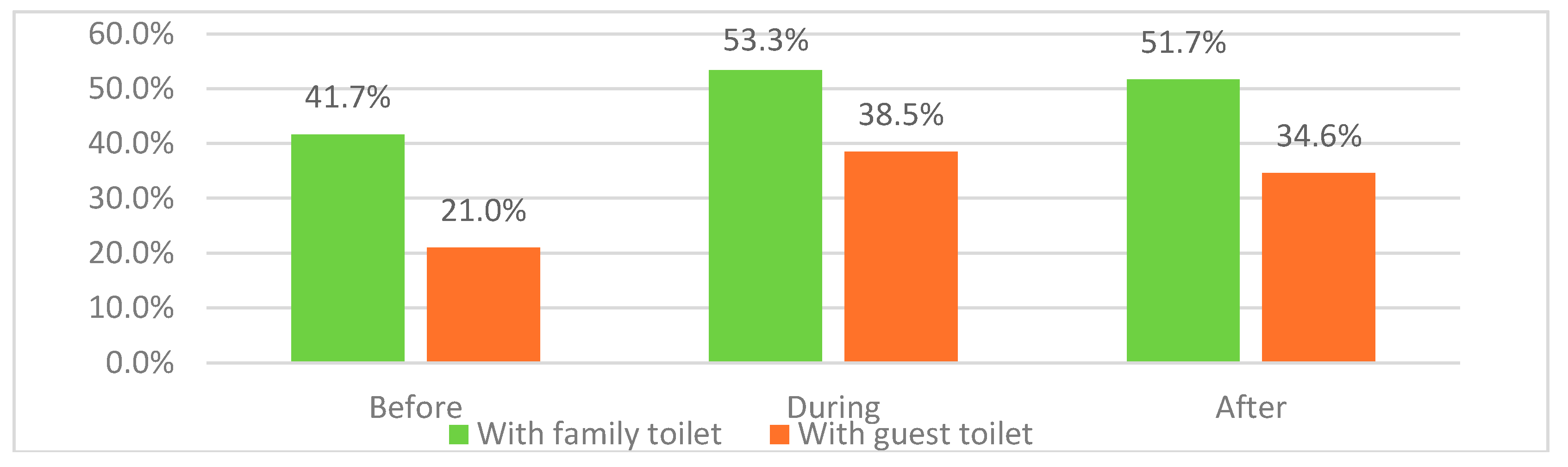

Significant dissatisfaction with toilets was observed, particularly in the pre-pandemic stage, where dissatisfaction exceeded 54%. This dissatisfaction intensified during the pandemic by an additional 13.3%. A deeper analysis revealed that 2+1 apartment categories consistently registered higher dissatisfaction across all stages compared to 3+1 categories, with the disparity growing during the pandemic. The absence of a separate toilet space markedly increased dissatisfaction levels, surging from 70.3% pre-pandemic to 83.9% during the pandemic for apartments lacking separate toilets. In contrast, apartments with separate toilets showed much lower dissatisfaction levels, increasing from 32.5% to 44.1% from pre- to post-pandemic stages. Apartments in the 2+1 category were particularly affected, with 75% of residents citing the lack of a separate toilet space as a primary cause of dissatisfaction, compared to only 12.5% in the 3+1 category, likely due to the latter’s generally higher availability of two bathrooms. Analysis of toilet dissatisfaction reasons for apartments with separate facilities showed that limited space, restricted activity options, and proximity to the entrance were the main concerns, with dissatisfaction percentages ranging modestly from 11.7% to 23.8%, except for the relationship to the entrance which noted only 5.3% dissatisfaction. Similar to the studies concerning bathroom designs Walisinghe [

31] reported that main dissatisfaction concern from the residents during COVID-19 was due to the design and size of toilets, similarly İslamoğlu [

1] reported that the number of toilets affected the satisfaction of the residents and future apartment designs should consider incorporating more than 1 toilet in the designs. These findings highlight the critical importance of thoughtful toilet placement and adequate space allocation in residential design to enhance residential satisfaction.

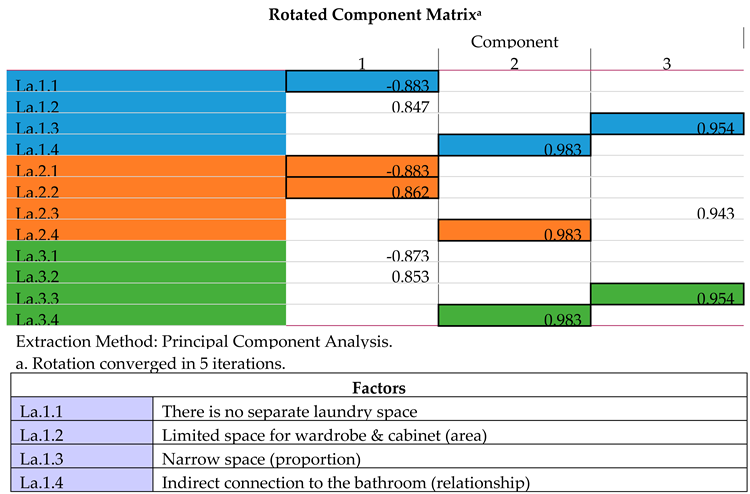

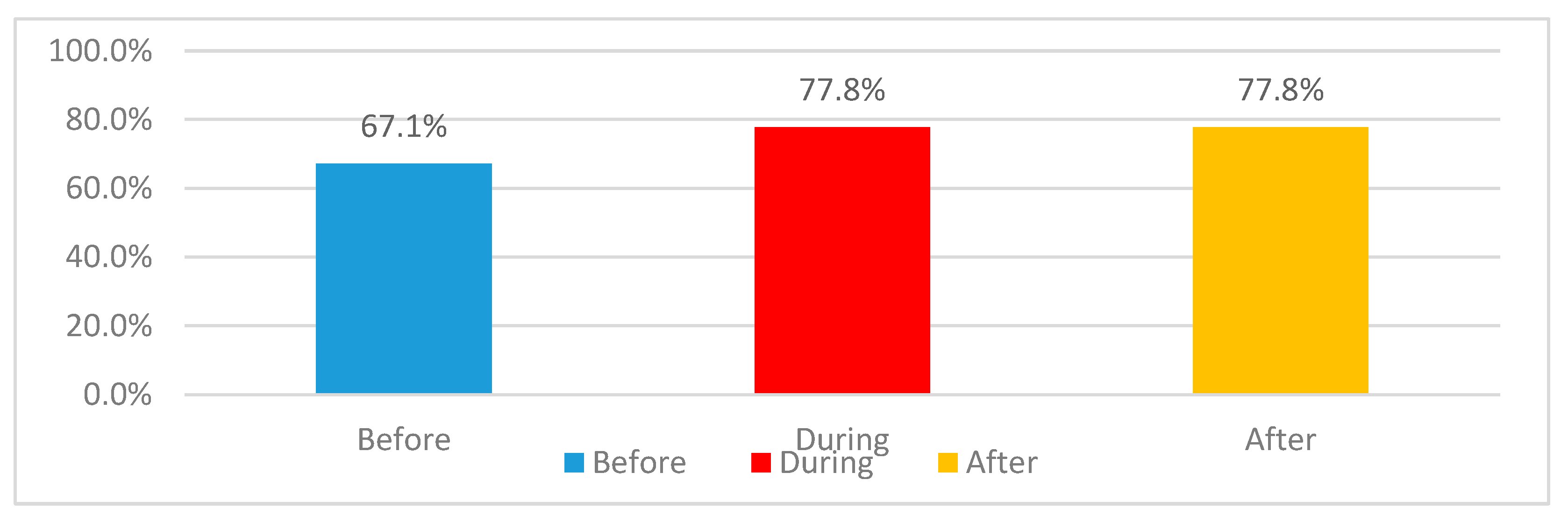

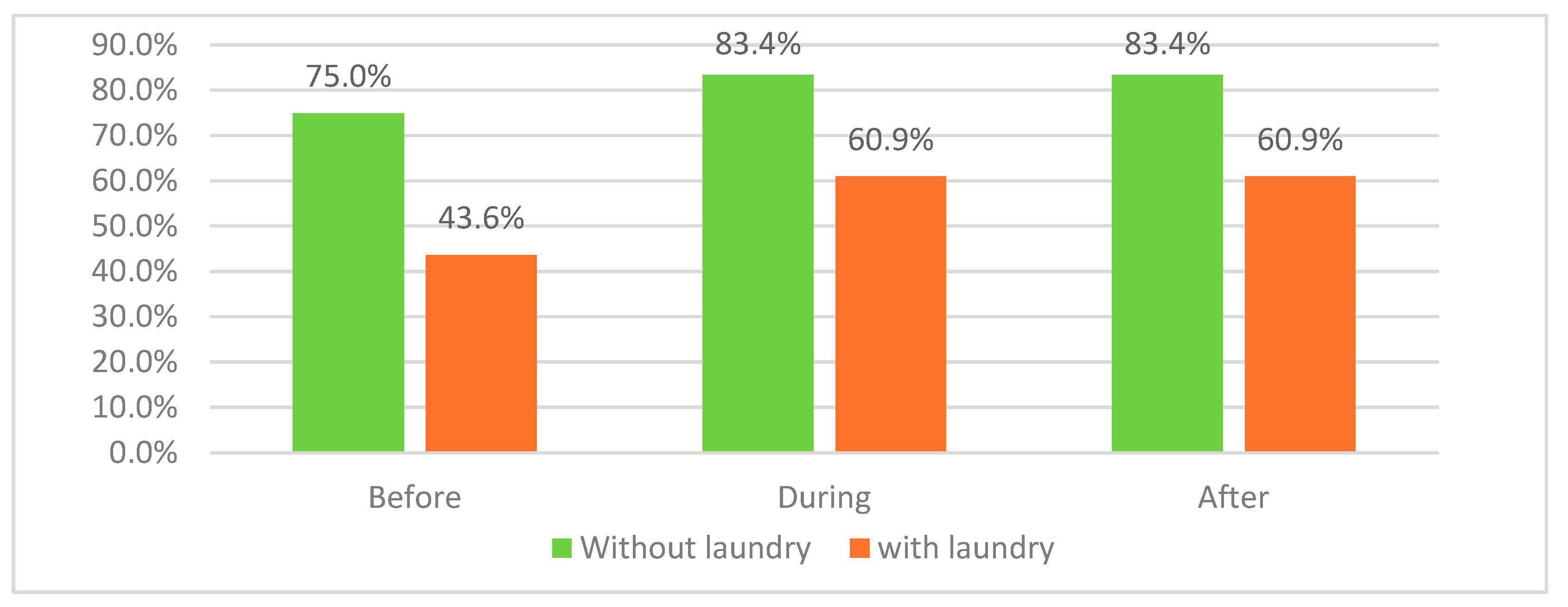

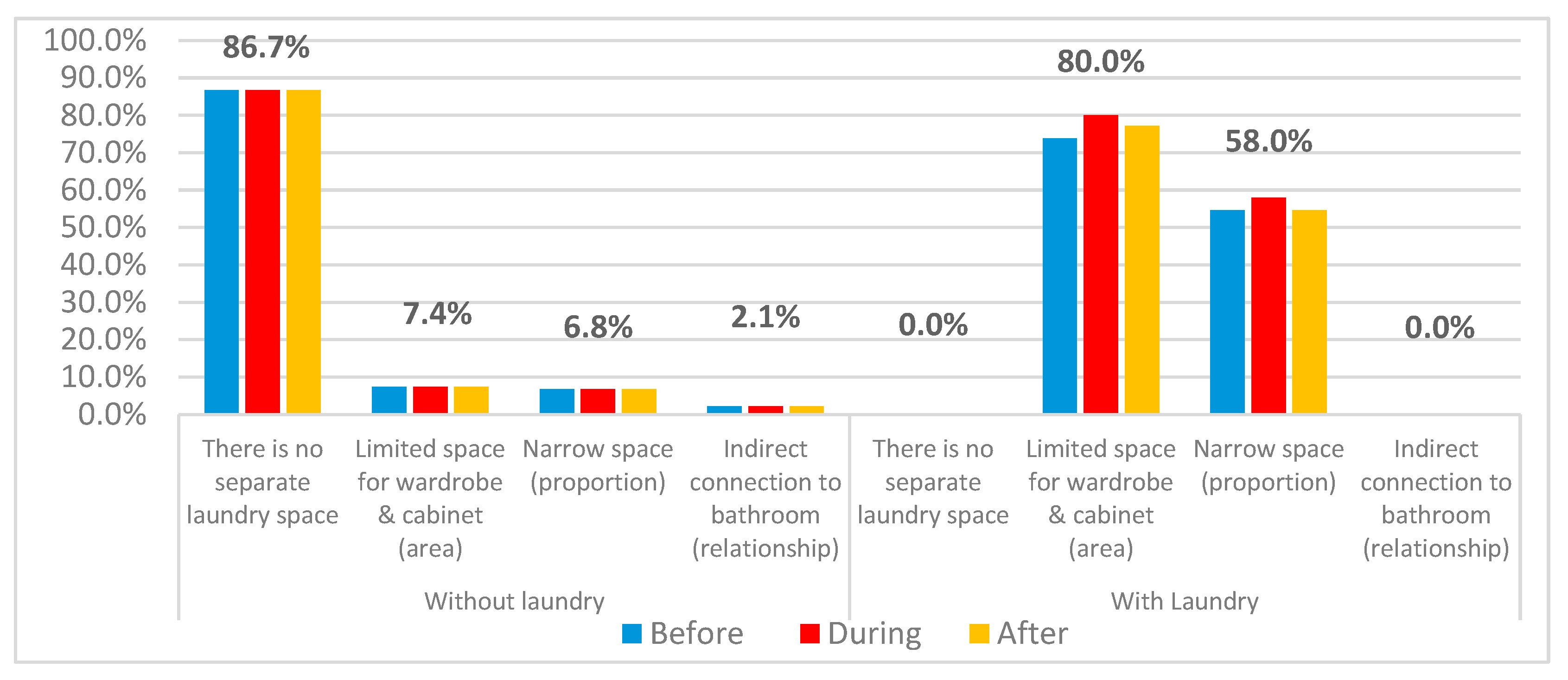

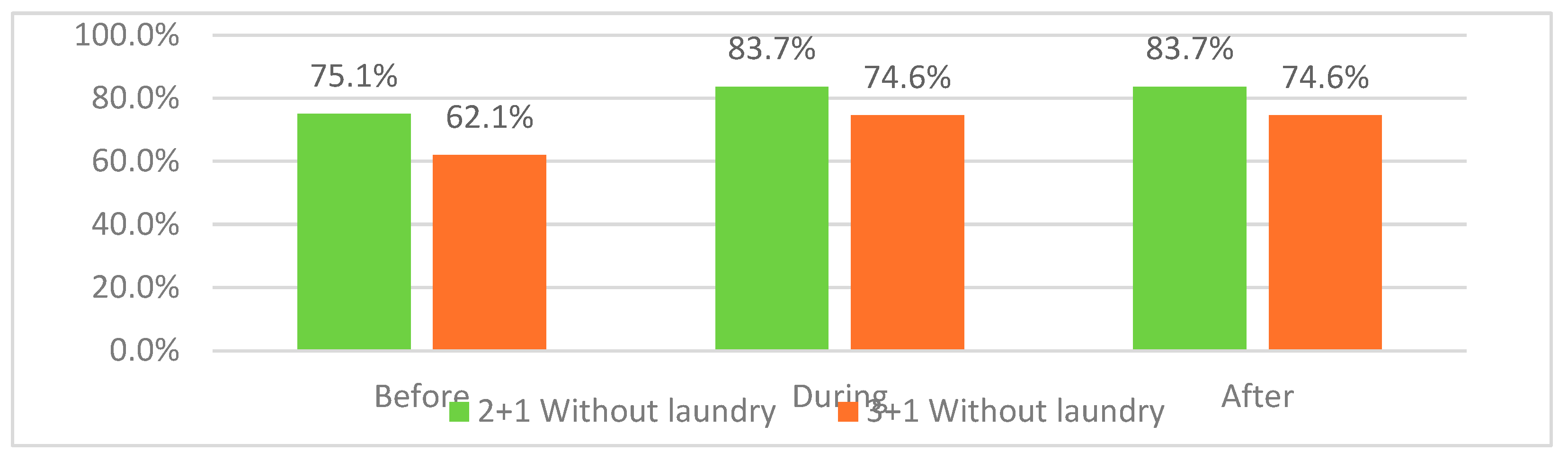

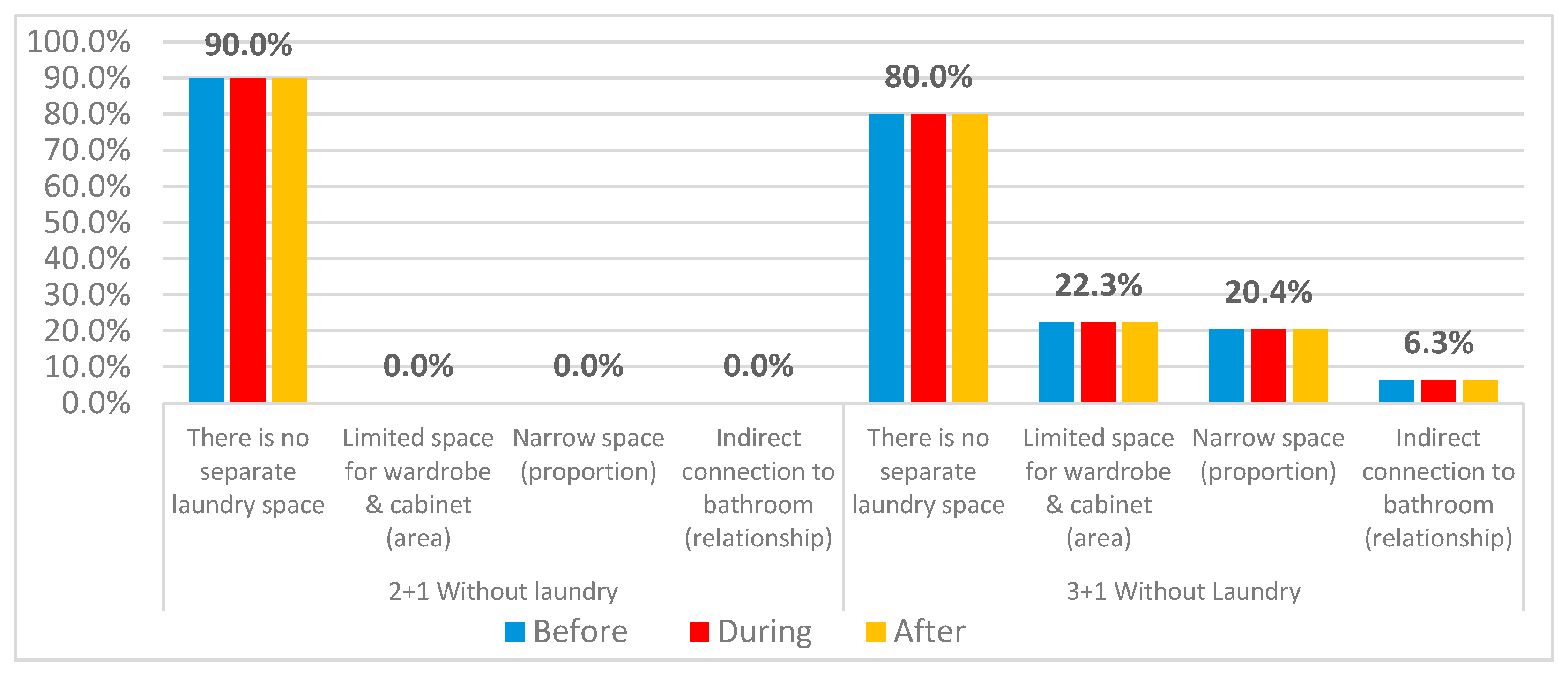

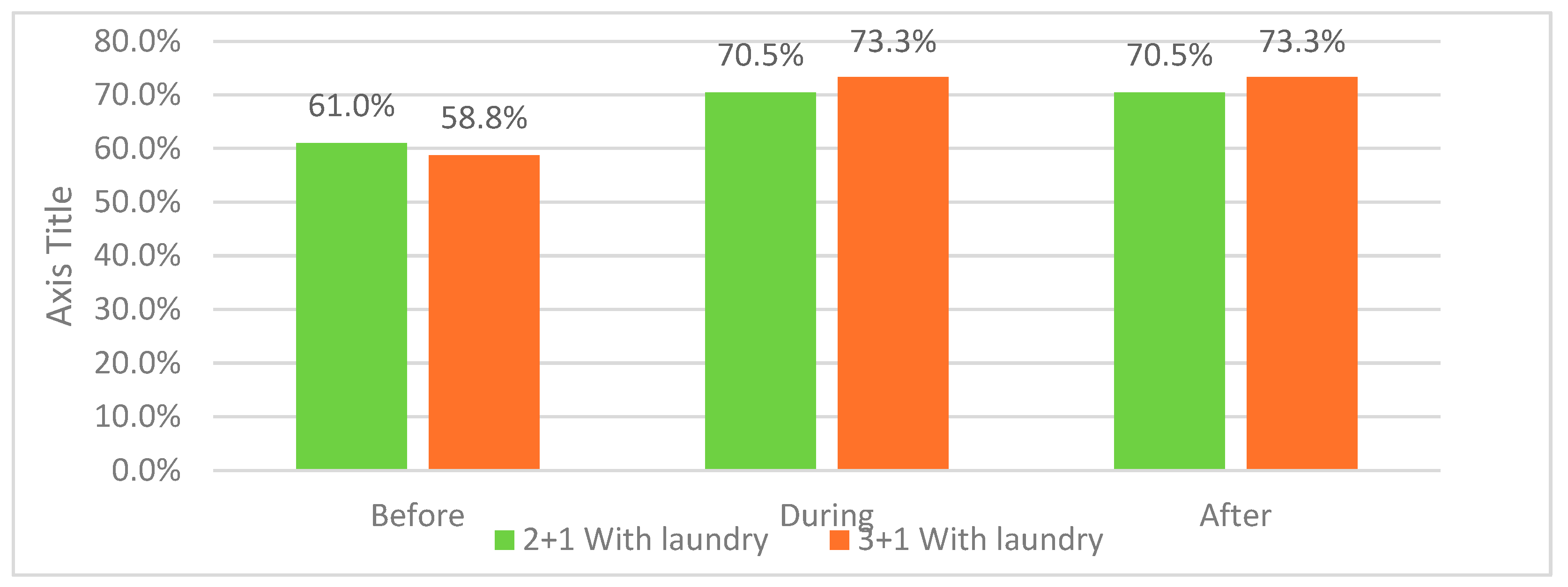

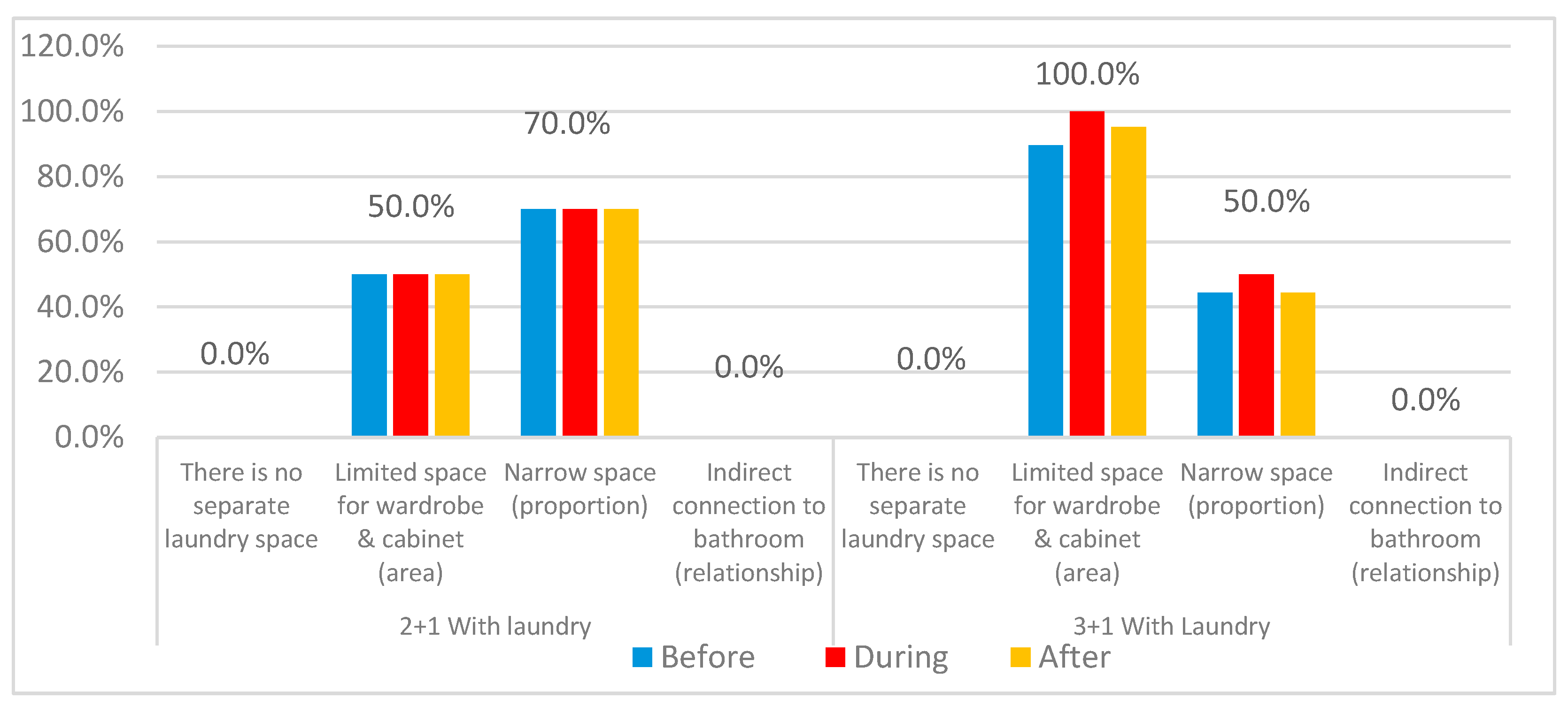

Dissatisfaction with laundry spaces significantly escalated during the pandemic, rising from 67.1% pre-pandemic to 77.8% during the pandemic. This high level of dissatisfaction persisted post-pandemic with a slight decrease. The findings from the results indicated that lack of laundry space in apartments significantly affected the satisfaction rate of the residents and those without a separate laundry space observed higher dissatisfaction compared to those with laundry space in their apartments especially smaller apartments which due limited space lacked laundry space in their apartments. While the satisfaction and dissatisfaction rates are close and main reasons behind dissatisfaction stemmed from limited laundry space and improper proportion of the space, future designs should consider dedicating a specific separate space for laundry activities that is both function and accessible to the residents.

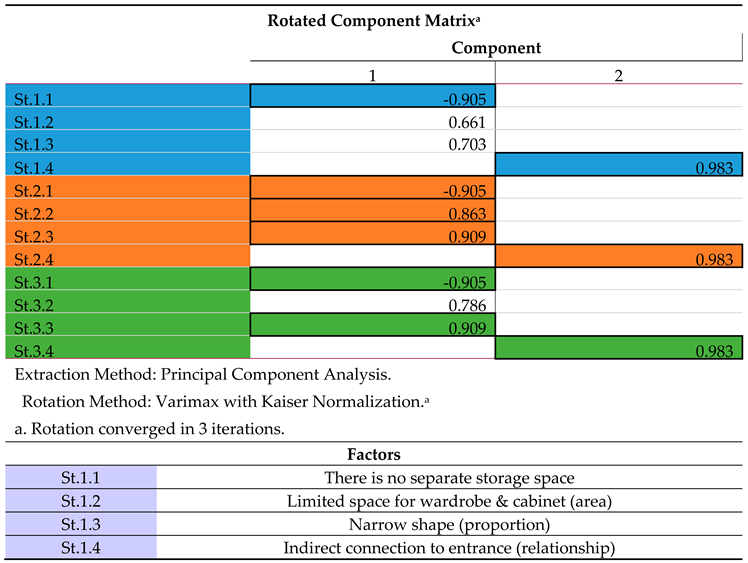

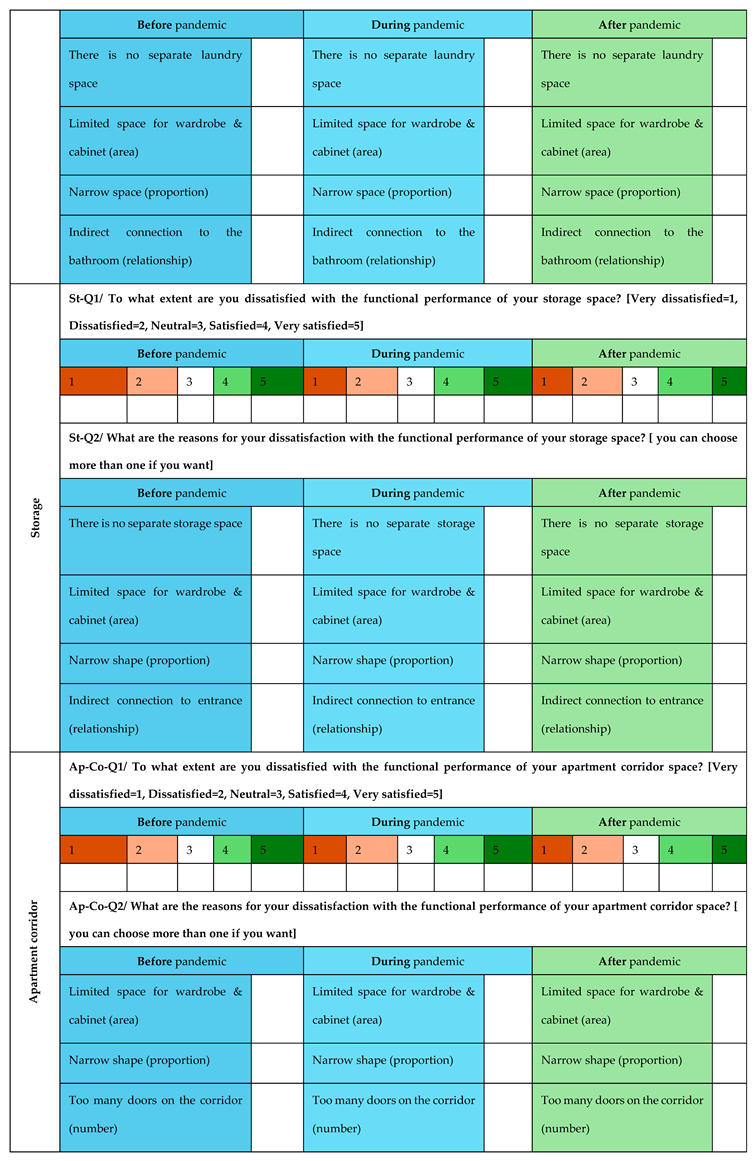

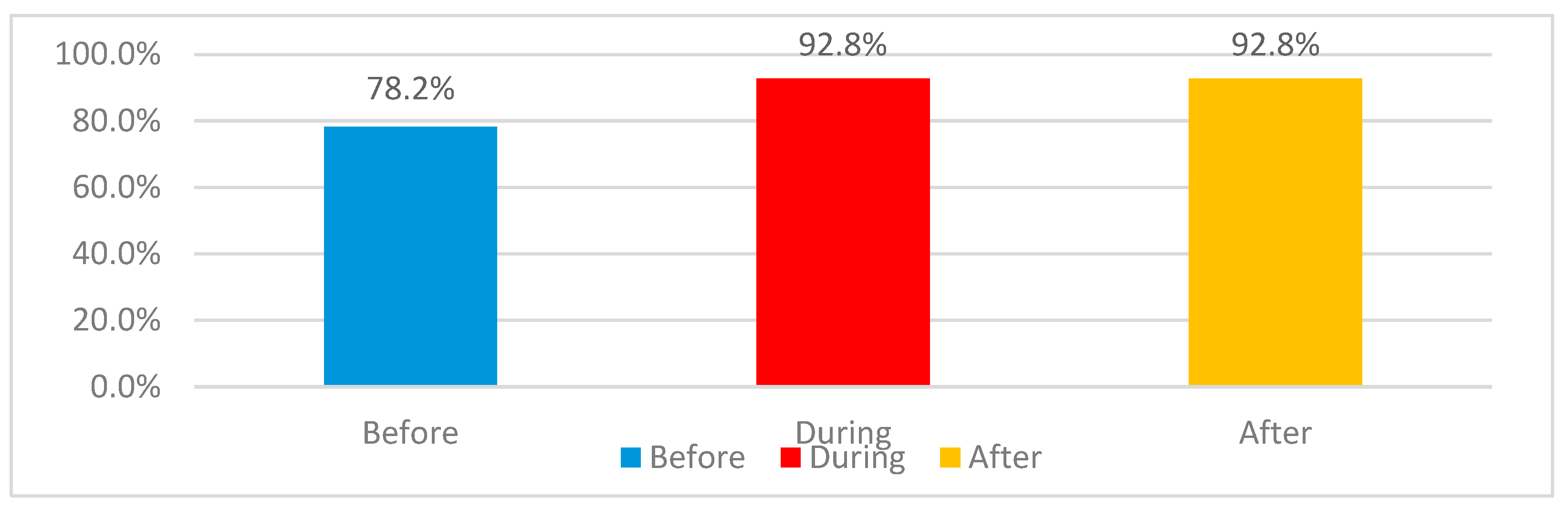

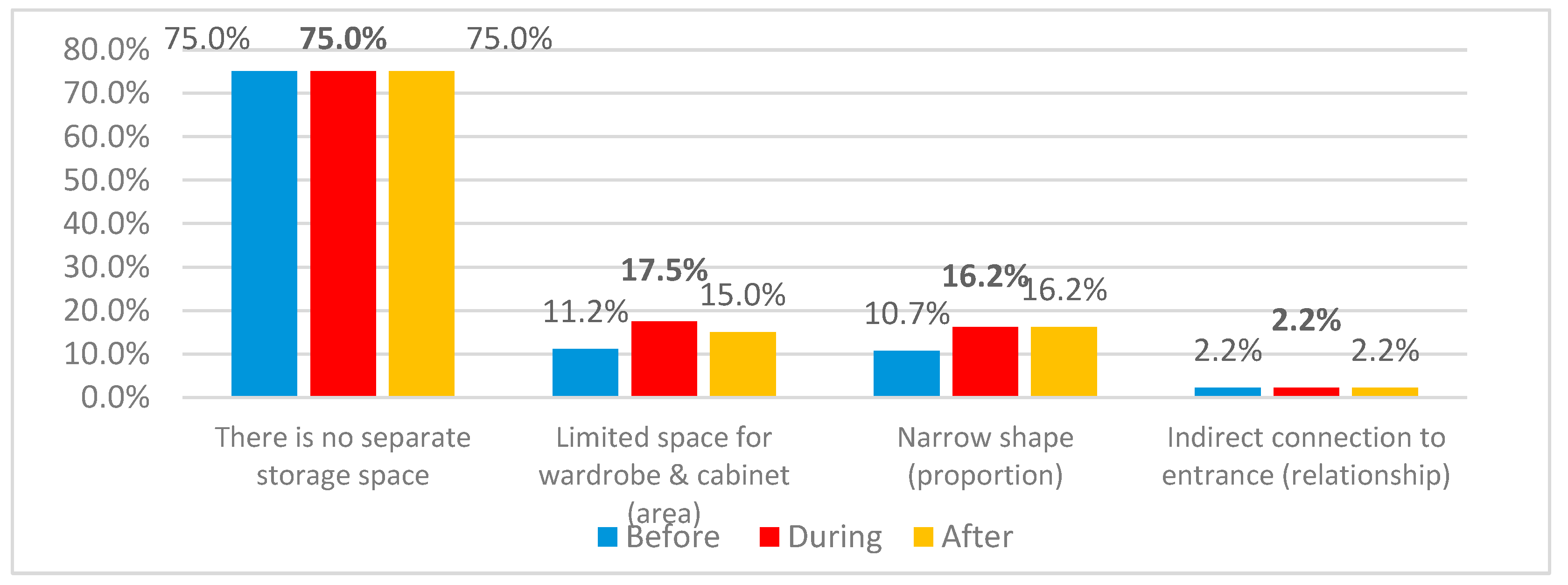

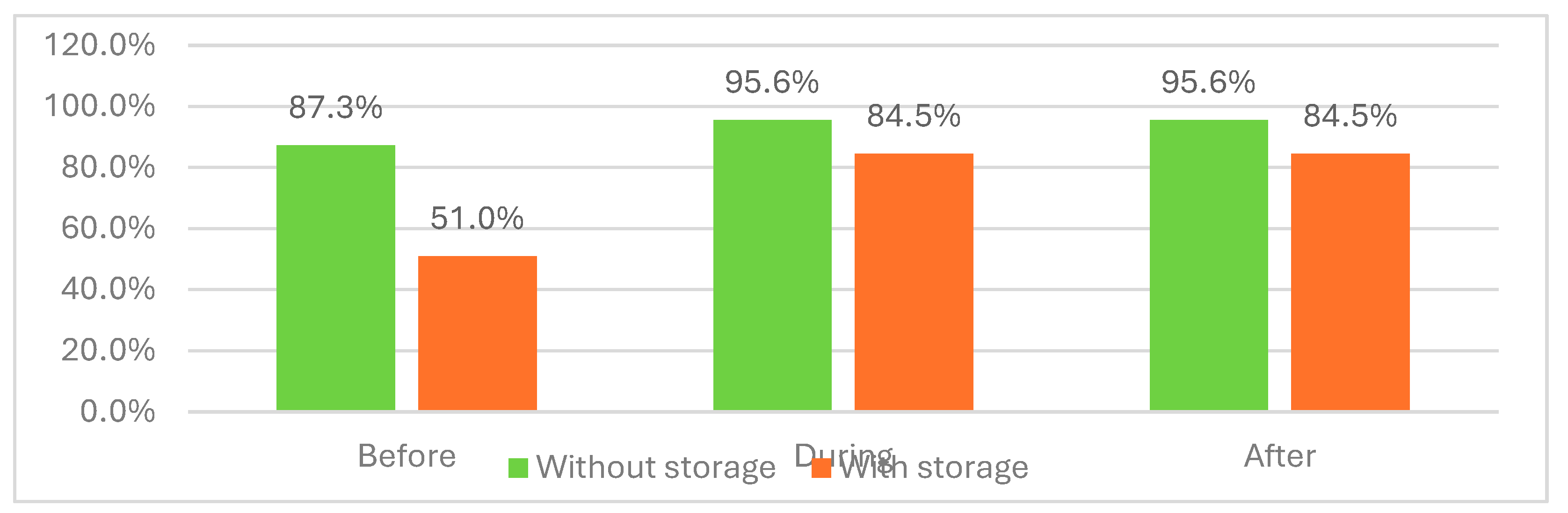

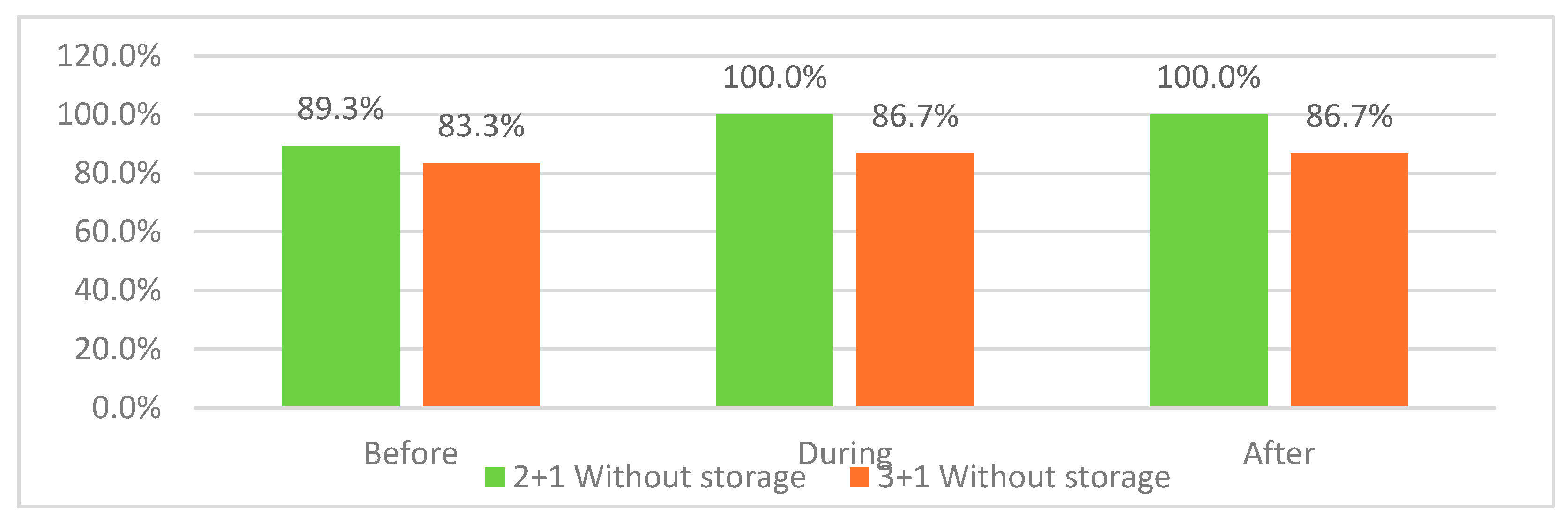

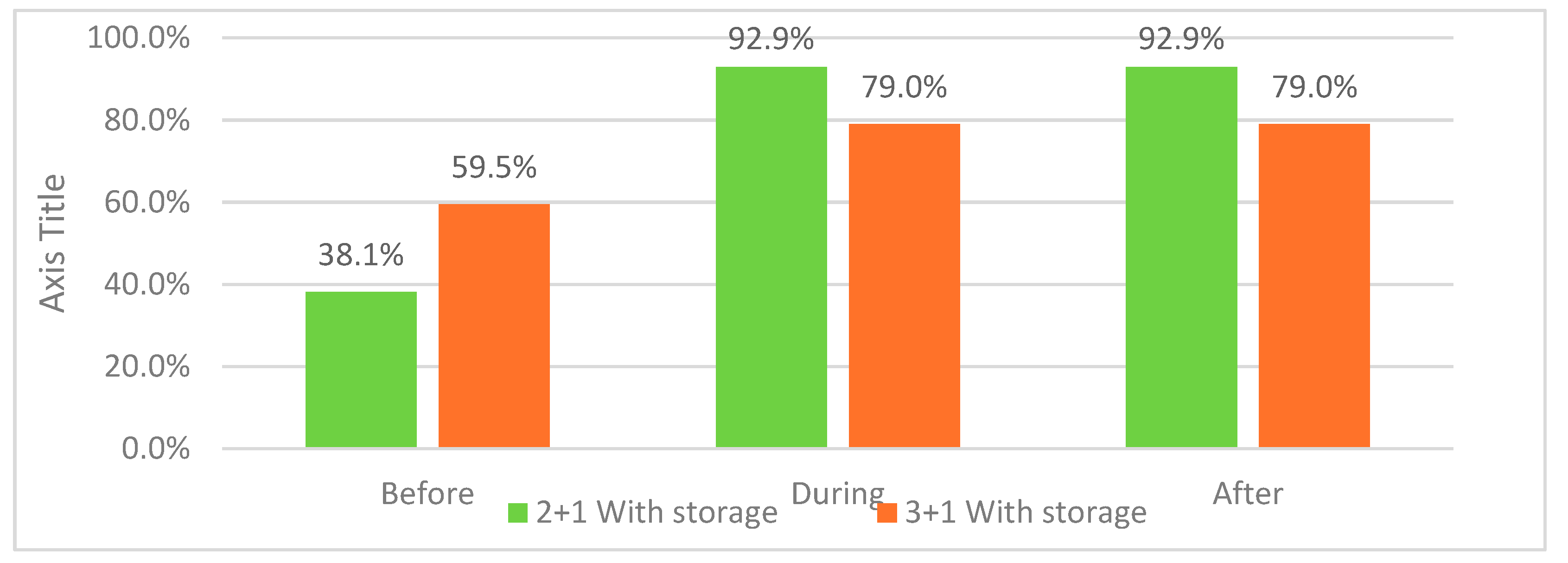

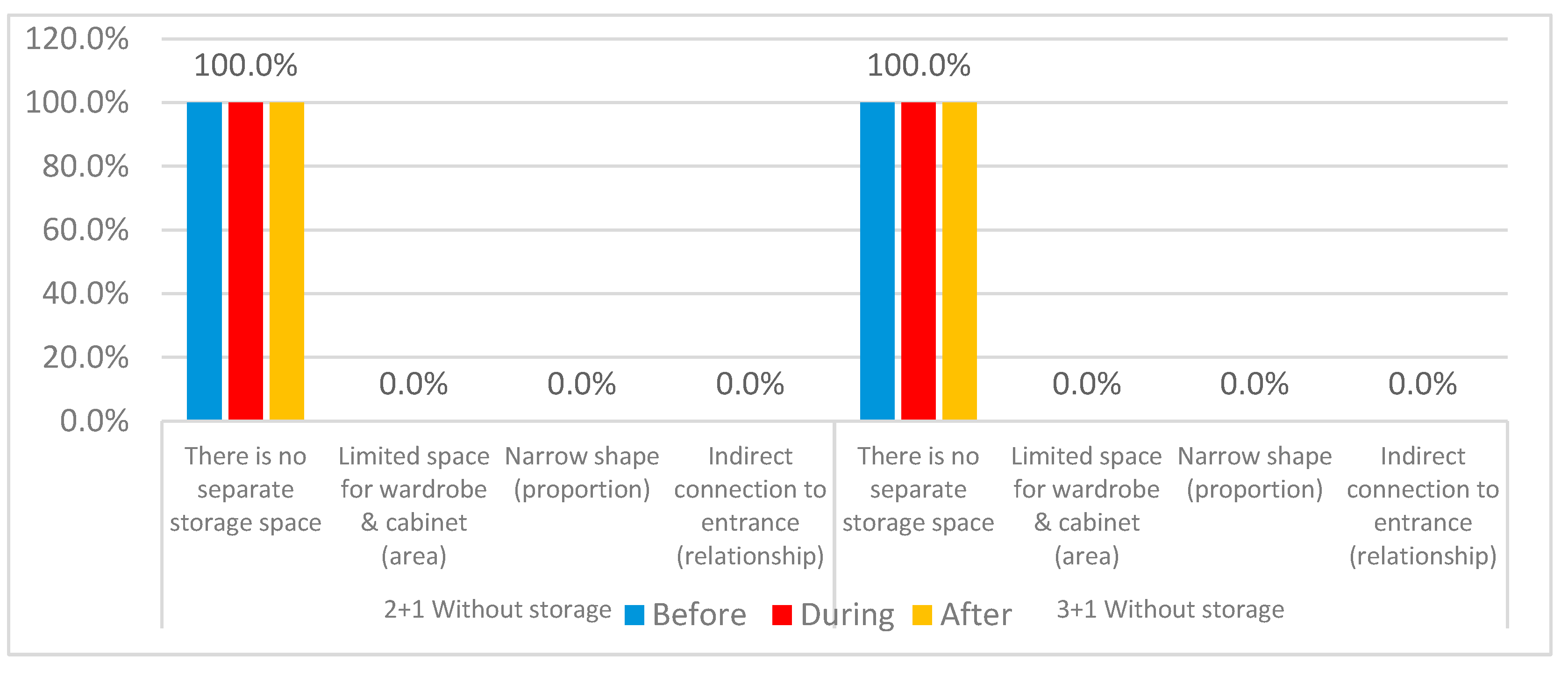

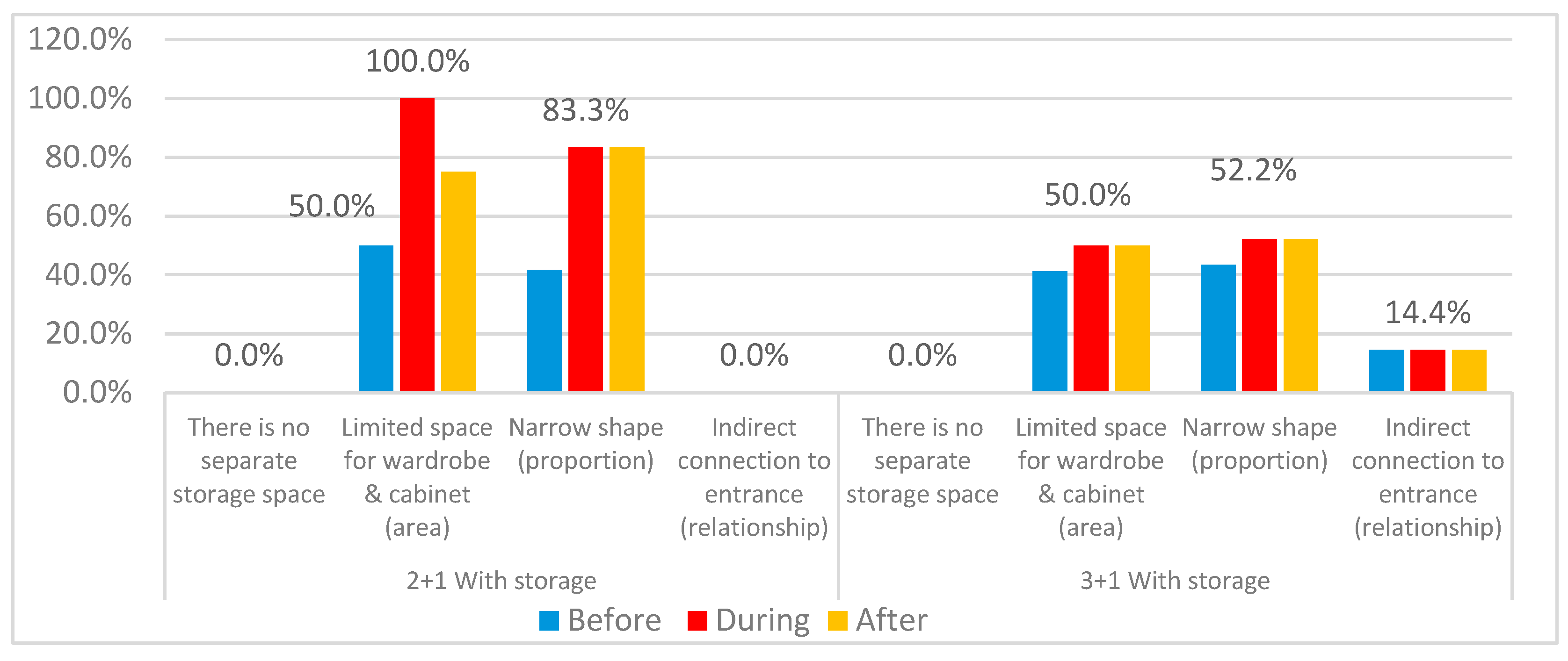

Storage spaced which served many needs of the apartments having it observed a significant dissatisfaction from the residents of the apartments. Before the pandemic dissatisfaction rates were lower compared to the time during and after the pandemic. The rates dissatisfaction rate increased to 92.8% during and after the pandemic from 78.2% before the pandemic. Both residents having storage space and those not having the space report high dissatisfaction rates with those lacking it reporting higher dissatisfaction 95.6% compared to those with storage space reporting 84.5%. Reasons that led to the dissatisfaction of residents having storage space in their apartments can be attributed to limited space and proportion of the space primarily. The analysis indicated that dissatisfaction was notably higher in apartments lacking specific storage spaces. Even in apartments with some form of storage, dissatisfaction persisted due to inadequate space and poor proportions and it was observed more in smaller apartments (2+1 category), where space constraints were more acute. The findings of the study are in parallel with findings from other studies [

18,

19,

21,

22,

23] which highlight the significant role of these space in well-being and comfort of the residents in apartment and residential complexes as the lack sufficient storage area affected the satisfaction level and prevented residents from storing sanitary equipment, exercise equipment, and other appliances. The importance of storage space was underscored, especially during the pandemic, highlighting the need for well-designed storage solutions in future apartment constructions to address these significant dissatisfaction levels effectively.

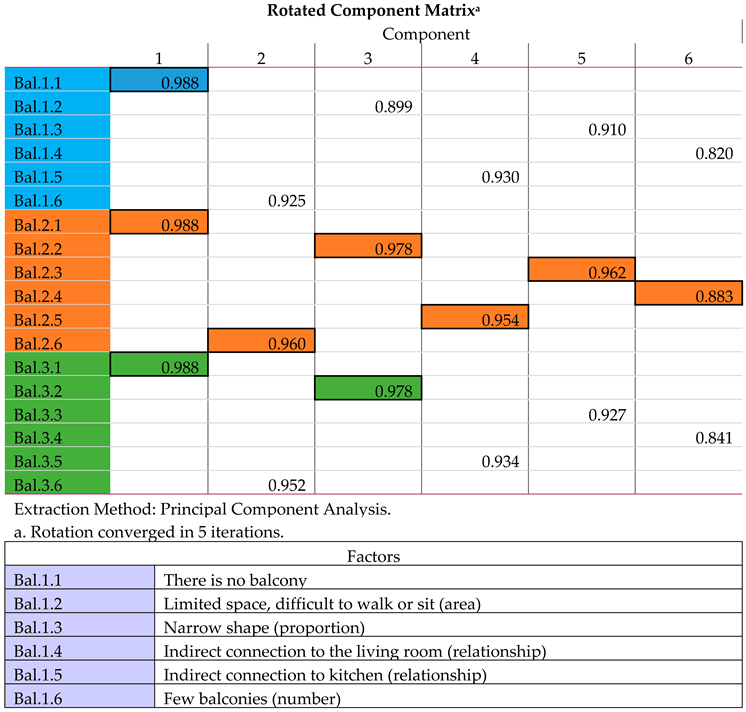

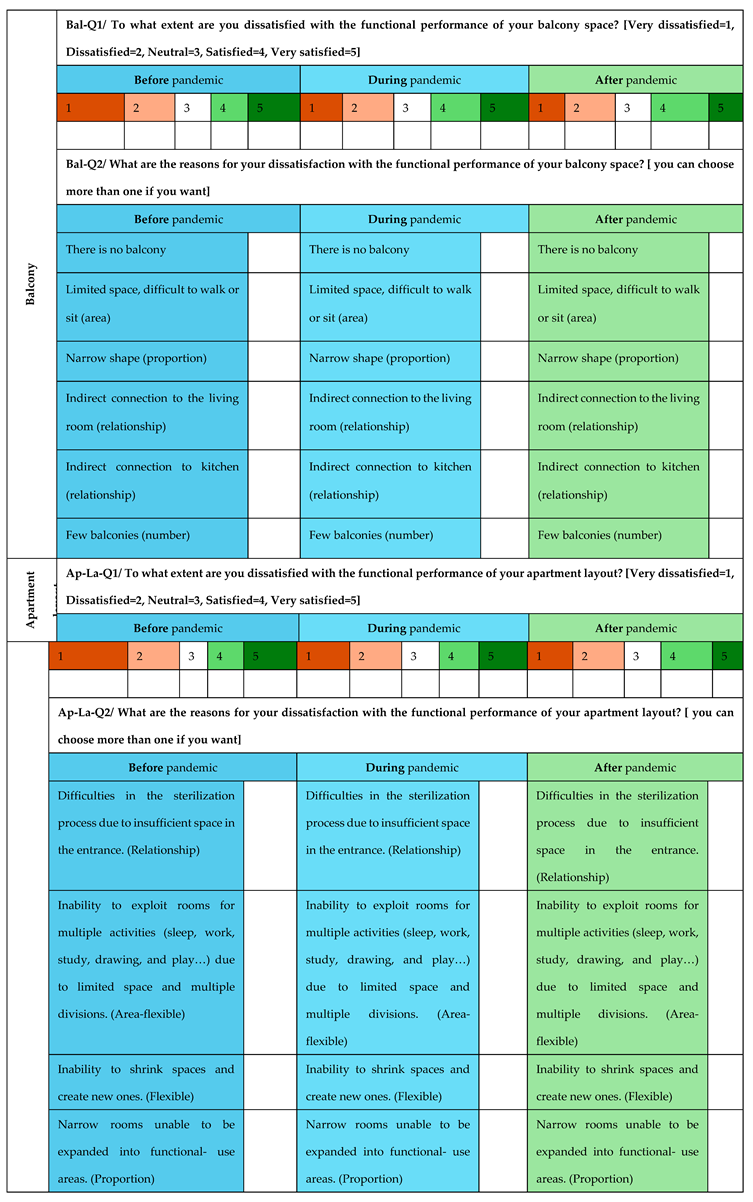

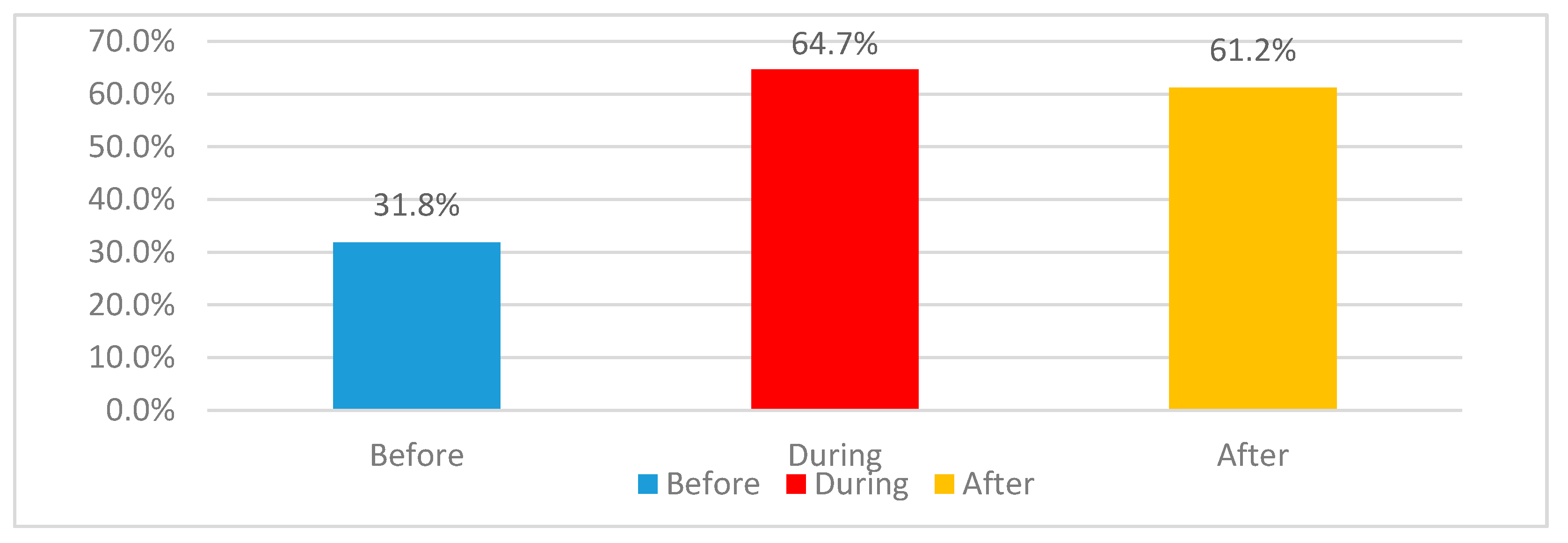

The presence of balconies in apartments significantly influenced resident satisfaction, particularly during the pandemic. Dissatisfaction escalated sharply from 31.8% pre-pandemic to 64.7% during the pandemic, reflecting the heightened importance of balconies as essential extensions of living space. Residents without balconies experienced dissatisfaction rates three times higher than those with balconies pre-pandemic, which intensified during and after the pandemic. Proportion, area, and the number of balconies were identified as primary dissatisfaction factors. Notably, dissatisfaction concerning balcony proportion and area increased post-pandemic. The findings also highlighted a particular demand for multiple balconies, with dissatisfaction decreasing substantially in apartments with more than one balcony. Balcony-related dissatisfaction varied by apartment type, with 2+1 apartments generally showing higher dissatisfaction levels than 3+1 apartments during the pandemic, though this trend did not extend to the pre-pandemic stage. Other researches while not investing in such detail as the presented study does, Aydin et al. [

34] highlights the significant role of balconies during the pandemic and claims that it was recognized as a place for gathering, dancing, playground for children, and eating activities. Peters and Masoudinejad [

35] found that apartments with balconies were more proffered by residents and larger balconies especially those facing green areas and natural views were more preferred compared to small and those facing other apartments rather than facing beautiful greeneries and natural views. The analysis highlights the critical need for satisfactory balcony space in apartment design, emphasizing that multiple and well-proportioned balconies can significantly enhance resident satisfaction by offering vital outdoor access and additional living space.

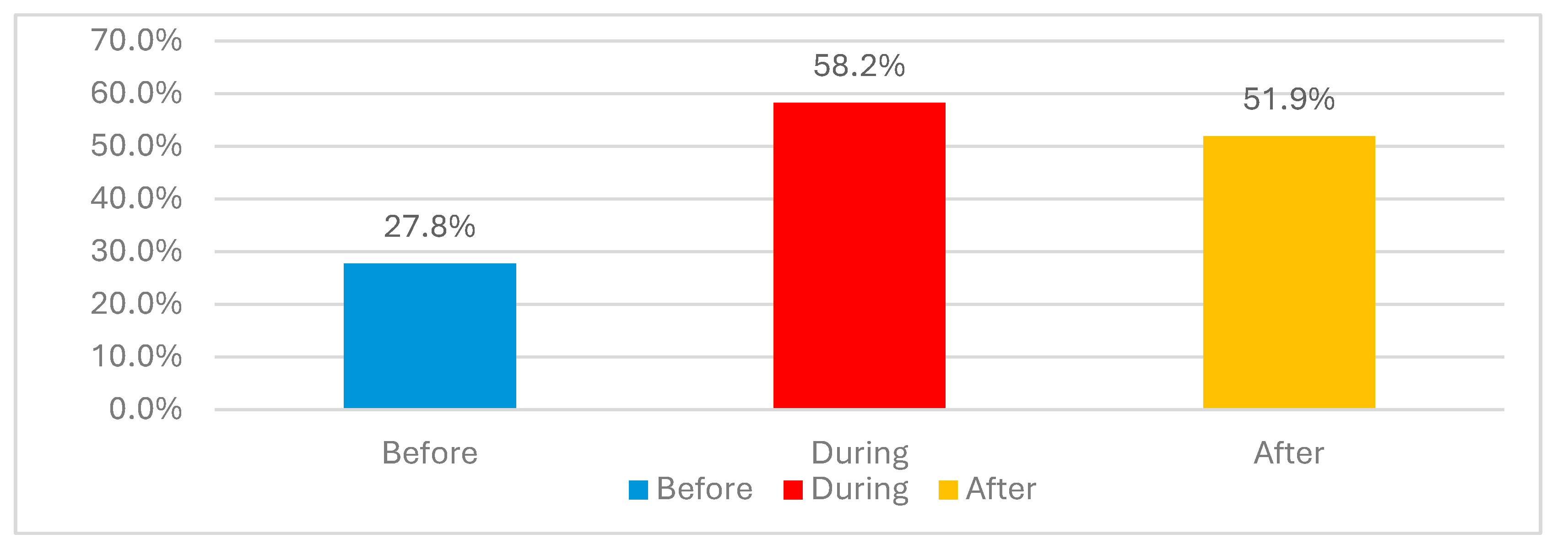

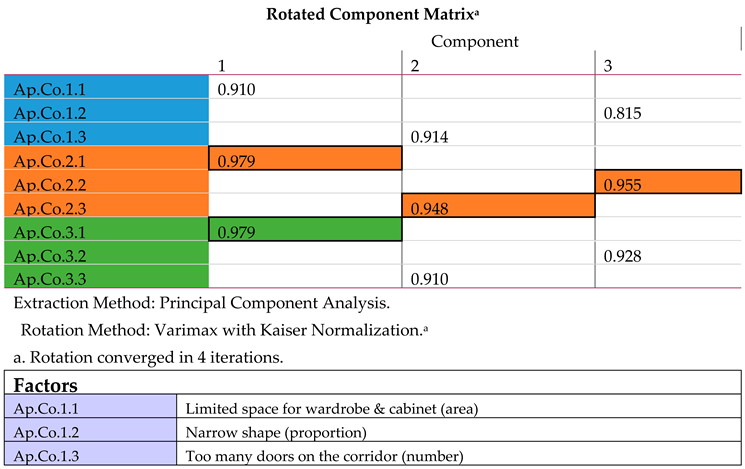

Dissatisfaction with apartment corridors more than doubled during the pandemic, with a slight reduction in the post-pandemic stage. The primary dissatisfaction factors were the narrow space of corridors and inadequate space for other needs beyond movement, such as storage, as well as the confusing layout due to an excessive number of doors. The smaller apartment categories (2+1) due to the small and restricted spaces during the pandemic stage reported higher dissatisfaction compared to larger apartments which significantly affects the proportion of corridor doors and additional space needs. Residents from open and closed designs organizations also reported dissatisfactions with closed designs reporting higher dissatisfactions before the and after the pandemic, and reported lesser dissatisfaction during the pandemic compared to open spatial design due to safety concerns that emerged at that time. The findings highlight the need for future designs to reconsider the design of corridors that serve the functionality and area allocation in unexpected events like the COVID-19 pandemic.

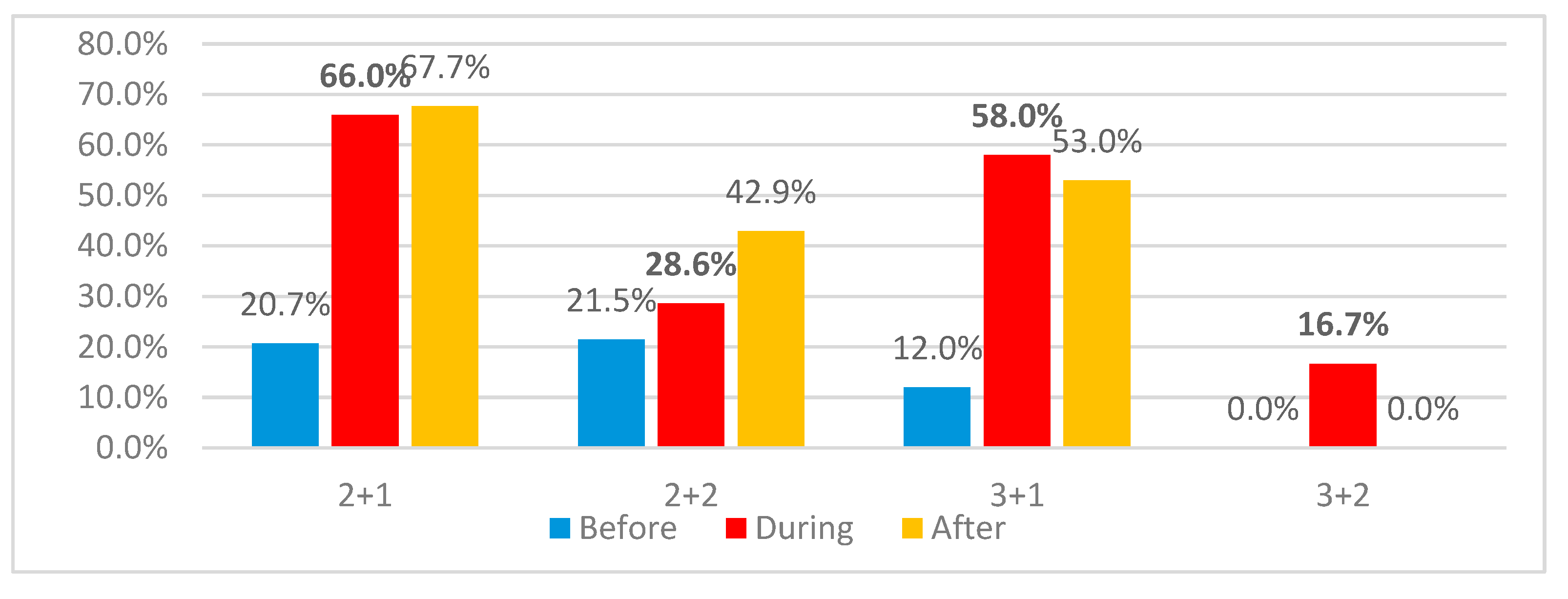

From the results, it was observed that dissatisfaction with the apartment layouts indicated a sharp increase from the pre-pandemic to during-pandemic stages, and it almost rose three time higher compared to the time before the pandemic while it slightly decreased in the post-pandemic stage. Smaller apartments (2+1) showed more dissatisfaction than larger ones (3+1), but additional living space in subcategories (2+2 and 3+2) reduced dissatisfaction levels. Open spatial organizations had higher dissatisfaction during and after the pandemic due to non-welcomed social contact, whereas closed spatial organizations faced inflexibility issues. The presence of balconies was the most significant factor in reducing dissatisfaction, followed by area flexibility, entrance space, and room proportion. Previous studies [

5,

36] have suggested for the presence of partitions or sliding panel partitions that allow for better individual privacy, wider doorways and corridors to be main the concerns for residential satisfaction during COVID-19. The present researches findings and those from the previous studies call for flexible spaces and adequate apartment layout designs in the future that consider the privacy of individuals.

5. Conclusions

Pandemic had a significant effect on residents housing requirements, most of those effects had permanent affect others had been moderated after pandemic.

The main logical finding is the clear increased contact between residents and their dwellings due to quarantine and social distancing obligations that participated in strengthening the resident-house relationship, leading increased focus despite trends and changes of degree of satisfaction.

Main dissatisfaction trends through the three stages according had showed three paths can be derived in assistance with

Table 17 for average percentages pointed out the following conclusions.

There are five spaces, the percentage of dissatisfaction increased during the pandemic, and the percentage were preserved or increased after the pandemic, and this confirms that the pandemic had a clear and stable impact on these spaces [ Living room, Family dining, Children’s bedroom, Laundry, and Storage].

Study found that there are eight spaces [Entrance, Master bedroom, Kitchen, Family bath, Toilet, Apartment corridor, Balcony, and Apartment layout] in which the percentage of dissatisfaction decreased during the pandemic compared to the rate after the pandemic, while maintaining a clear difference in percentage between before and after the pandemic, and this confirms that the effect of the pandemic is still present.

On the other hand, the single space [Reception] where the rate of dissatisfaction before the pandemic was higher than the rate during and after the pandemic, decrease of satisfaction is due to less need for that activity due to quarantine not to alterations in space to minimize dissatisfaction. It is a kind of a shift in residents’ opinions added to non-need for guest reception room.

Out of the 14 spaces and activities tested by this study 9 of them showed dissatisfaction value exceeded 50% of respondents, meaning clear disparity between designs and family needs, results strongly signaled the problem of missing storage and laundry spaces, followed by shortages in requirements belonging to kitchen, separate toilet, balcony, family dining, entrance lobby and apartment corridor with apartment layout configuration.

Less critical cases were agreement in residents’ dissatisfaction been within the range of less than 50% down to 30% are living rooms, bathrooms, children’s bedrooms, reception, followed by master bedrooms.

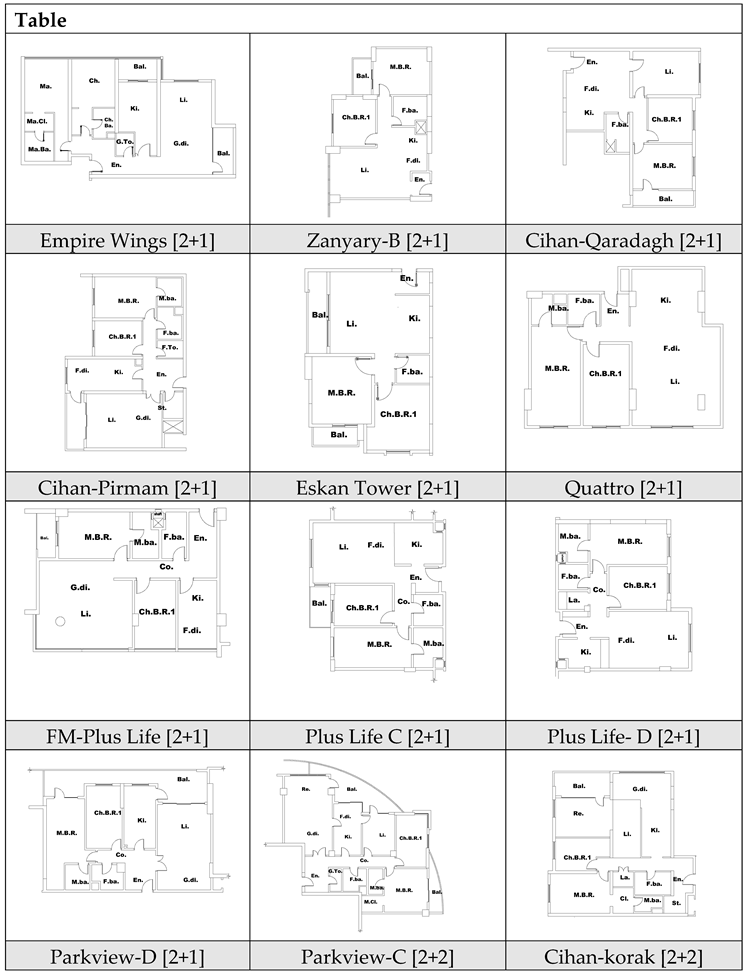

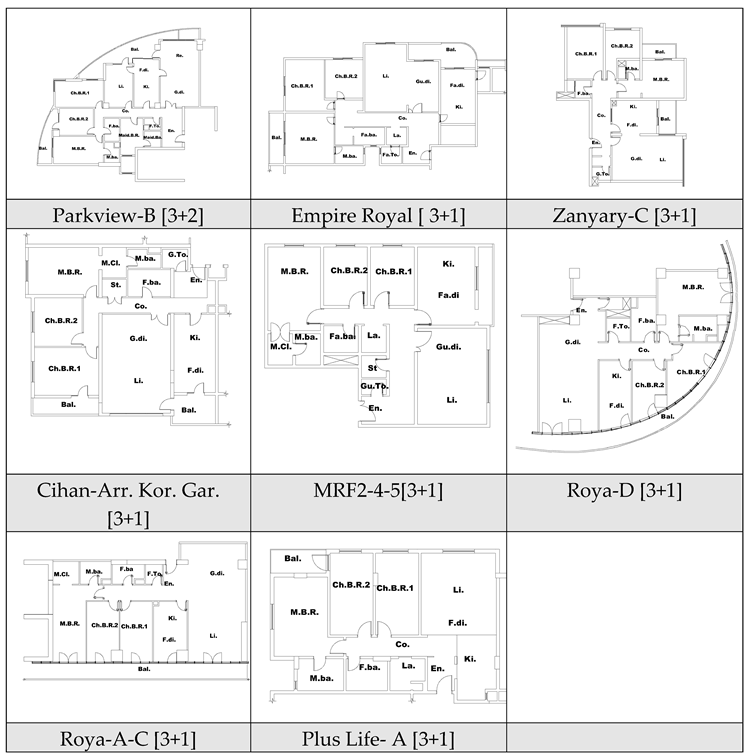

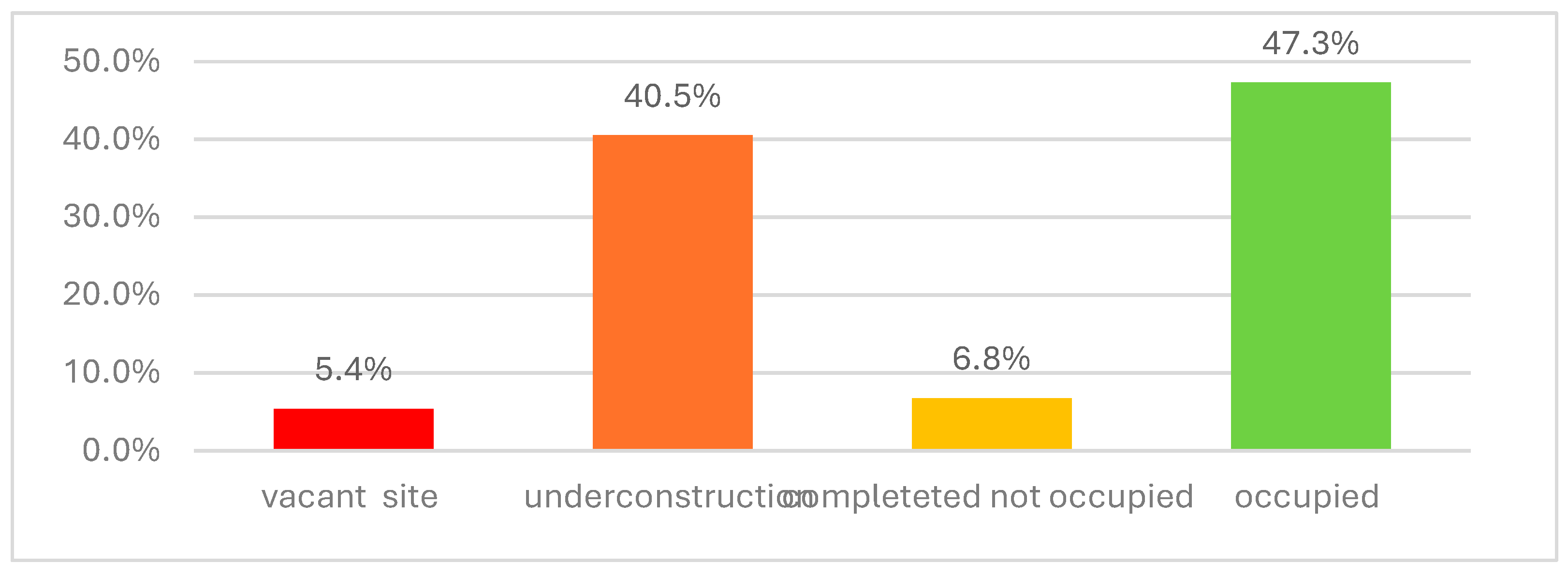

Figure 1.

Distribution of investment projects according to construction status- 2021.

Figure 1.

Distribution of investment projects according to construction status- 2021.

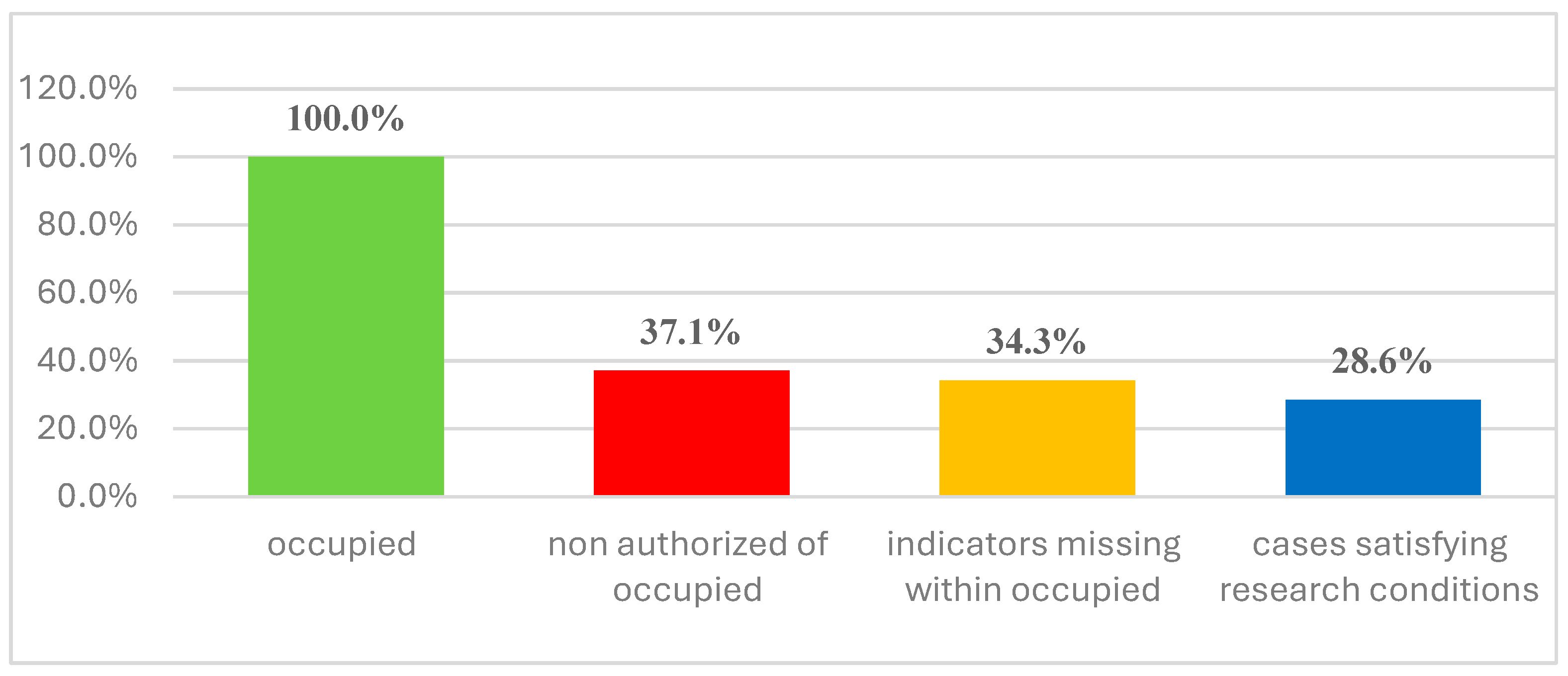

Figure 2.

Distribution of selected projects for study within occupied projects - 2021.

Figure 2.

Distribution of selected projects for study within occupied projects - 2021.

Figure 3.

Change in dissatisfaction percentage of entrance lobby during three stages.

Figure 3.

Change in dissatisfaction percentage of entrance lobby during three stages.

Figure 4.

Change in dissatisfaction percentage due to Entrance lobby availability .

Figure 4.

Change in dissatisfaction percentage due to Entrance lobby availability .

Figure 5.

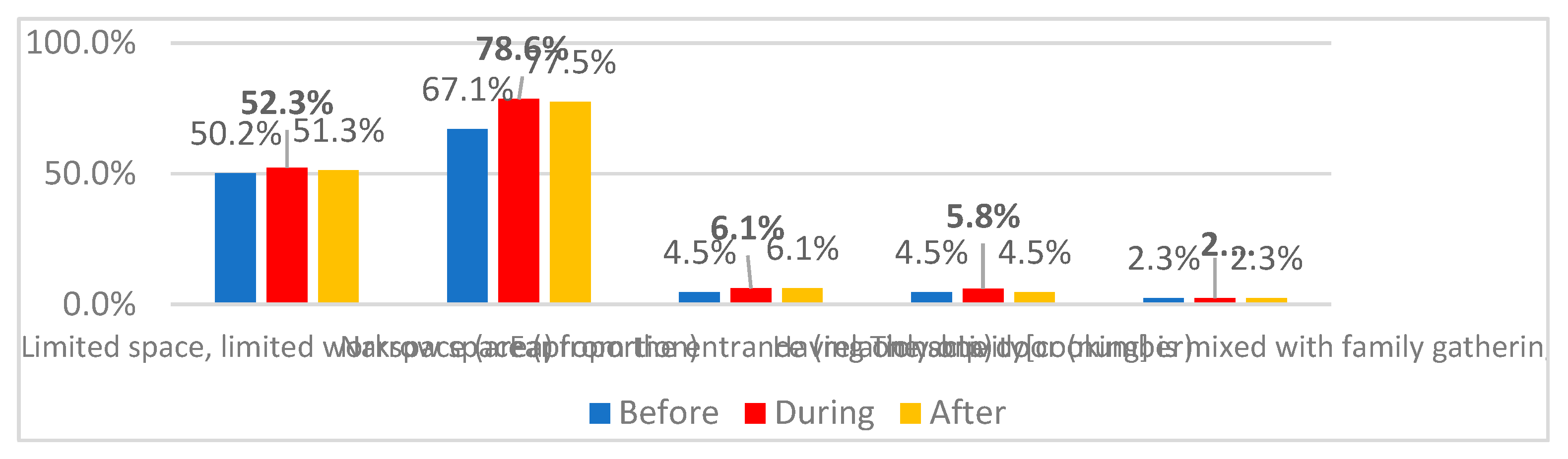

Reasons for variations in dissatisfaction percentage regarding entrance lobby.

Figure 5.

Reasons for variations in dissatisfaction percentage regarding entrance lobby.

Figure 6.

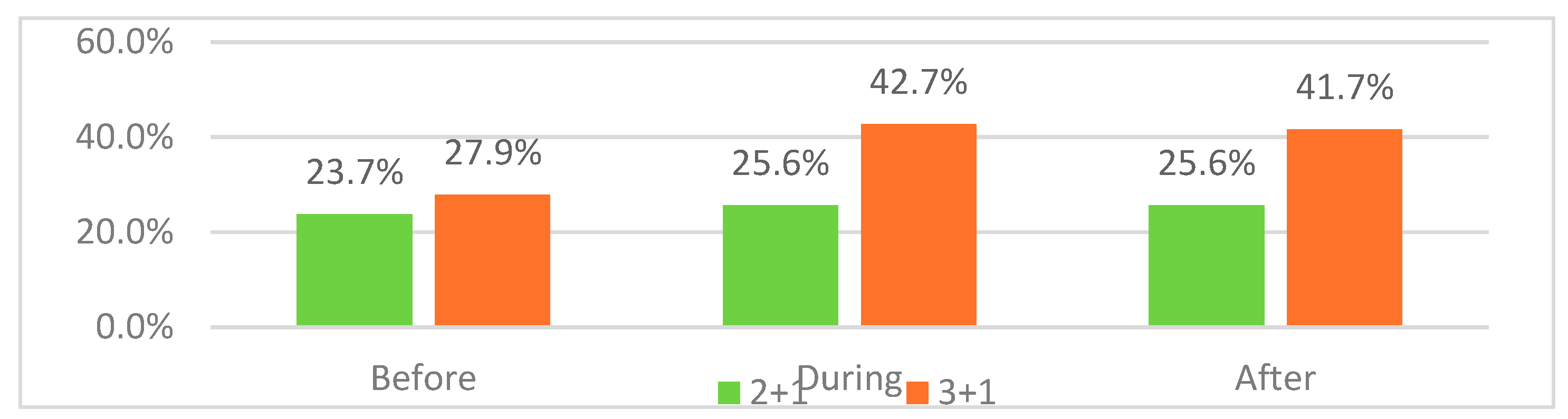

Variations in dissatisfaction percentage for Entrance lobby availability between 2+1 and 3+1 apartment categories.

Figure 6.

Variations in dissatisfaction percentage for Entrance lobby availability between 2+1 and 3+1 apartment categories.

Figure 7.

Variations in dissatisfaction percentages for Entrance lobby due to combined effect of availability and apartment categories.

Figure 7.

Variations in dissatisfaction percentages for Entrance lobby due to combined effect of availability and apartment categories.

Figure 8.

Reason of variations in dissatisfaction concerned with Entrance lobby for all categories.

Figure 8.

Reason of variations in dissatisfaction concerned with Entrance lobby for all categories.

Figure 9.

Change in dissatisfaction percentage due to Entrance toilet availability.

Figure 9.

Change in dissatisfaction percentage due to Entrance toilet availability.

Figure 10.

Reasons of variations in dissatisfaction percentages concerned with Entrance lobby between cases having toilets and those who missed that space .

Figure 10.

Reasons of variations in dissatisfaction percentages concerned with Entrance lobby between cases having toilets and those who missed that space .

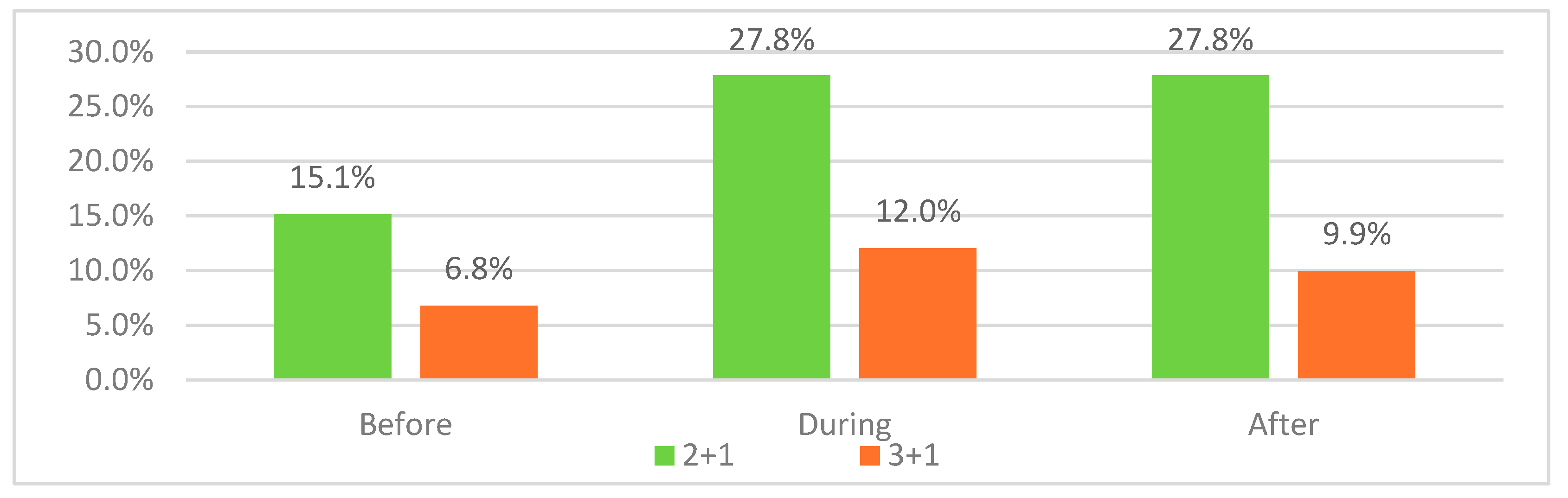

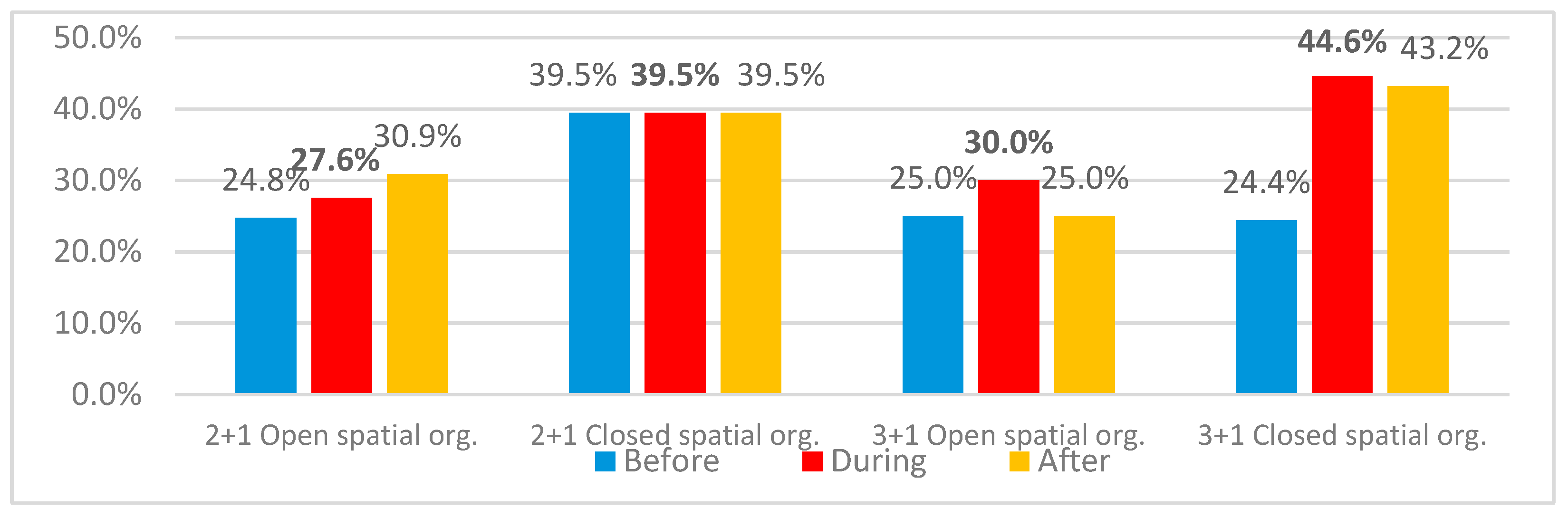

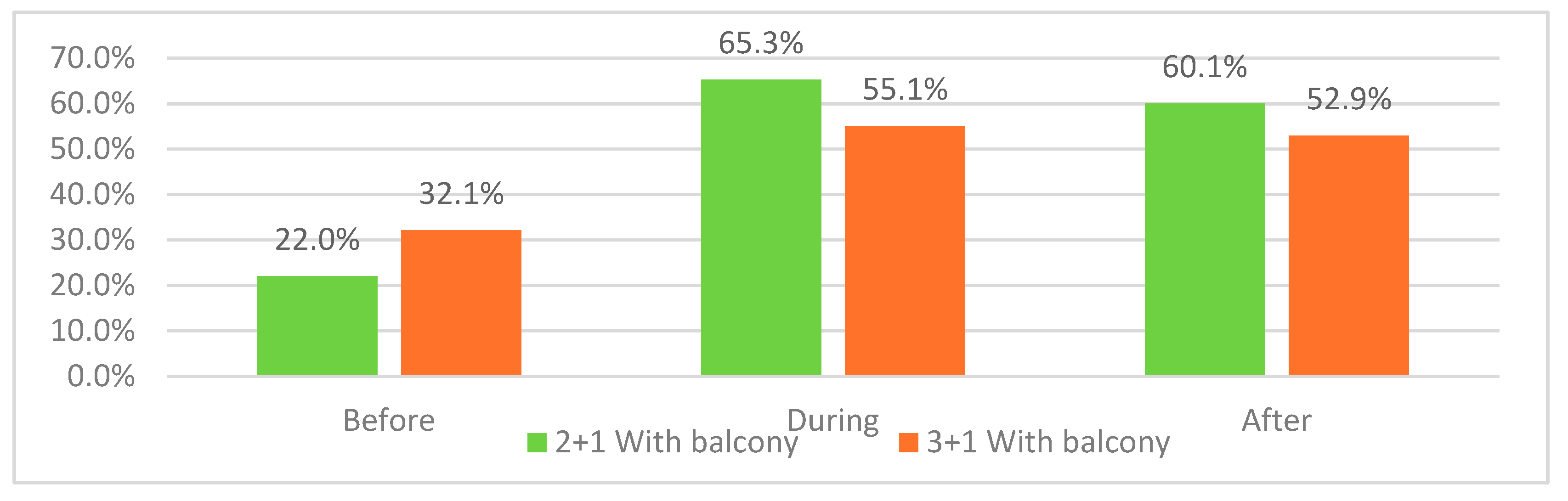

Figure 13.

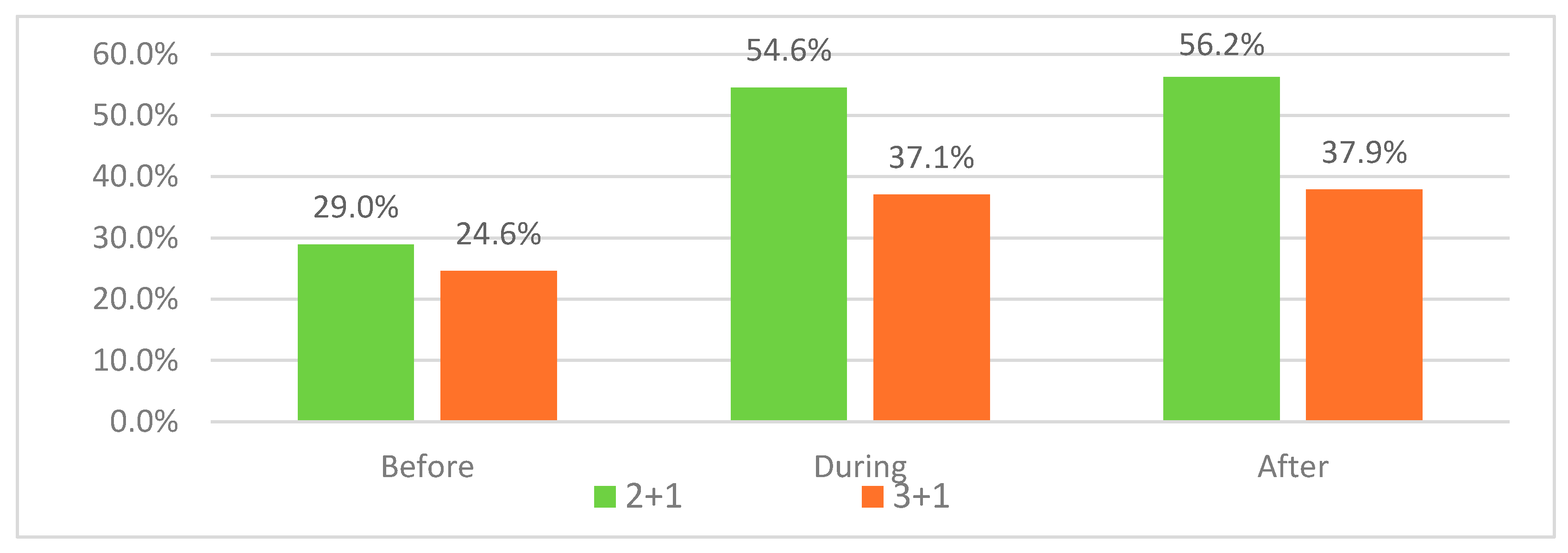

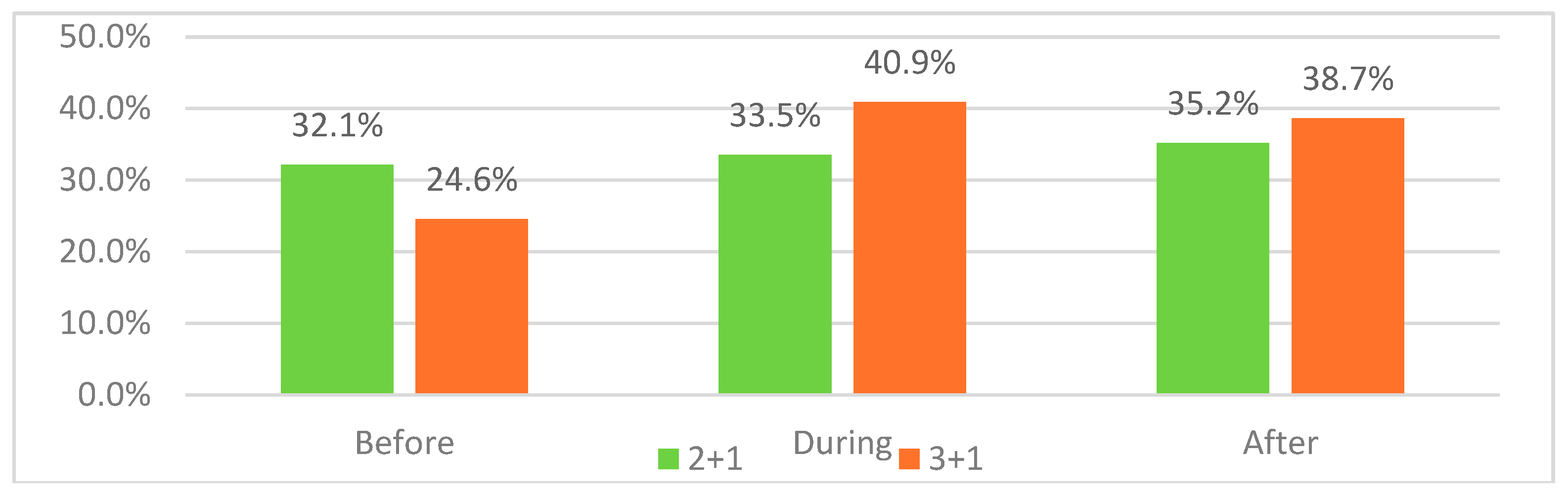

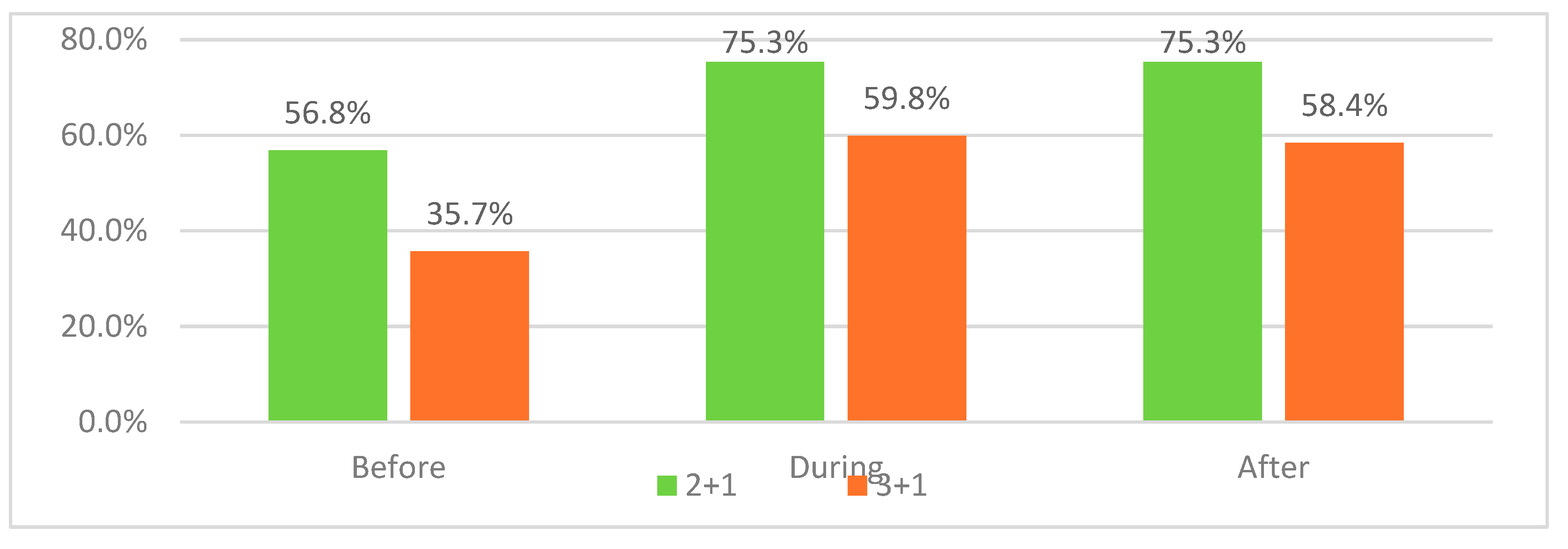

Differences in dissatisfaction of living rooms for different apartment sizes.

Figure 13.

Differences in dissatisfaction of living rooms for different apartment sizes.

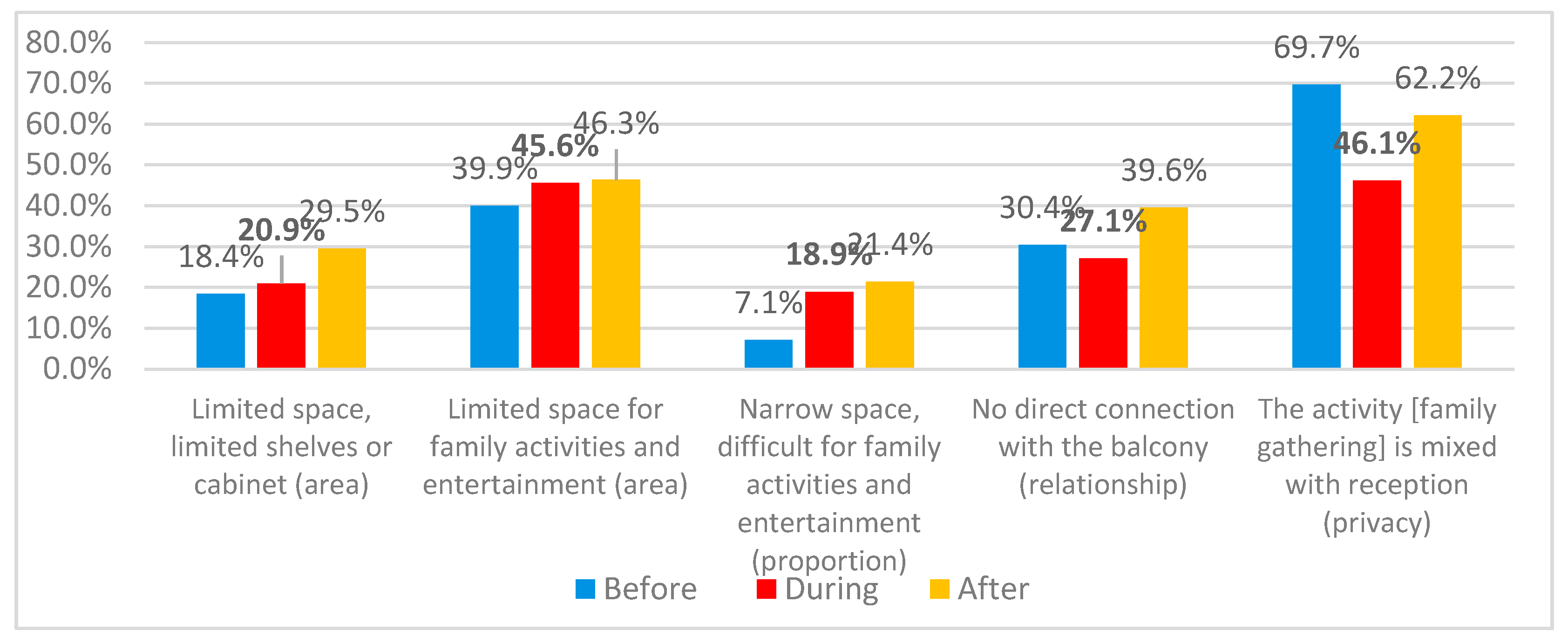

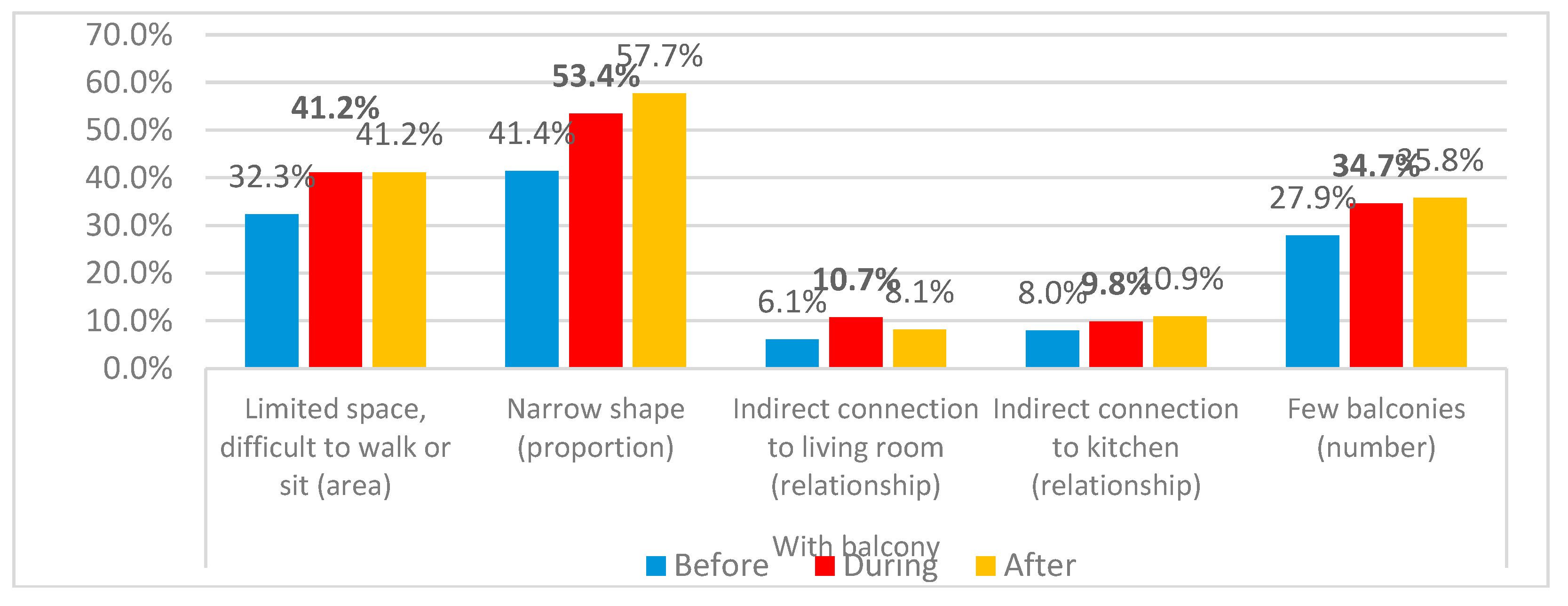

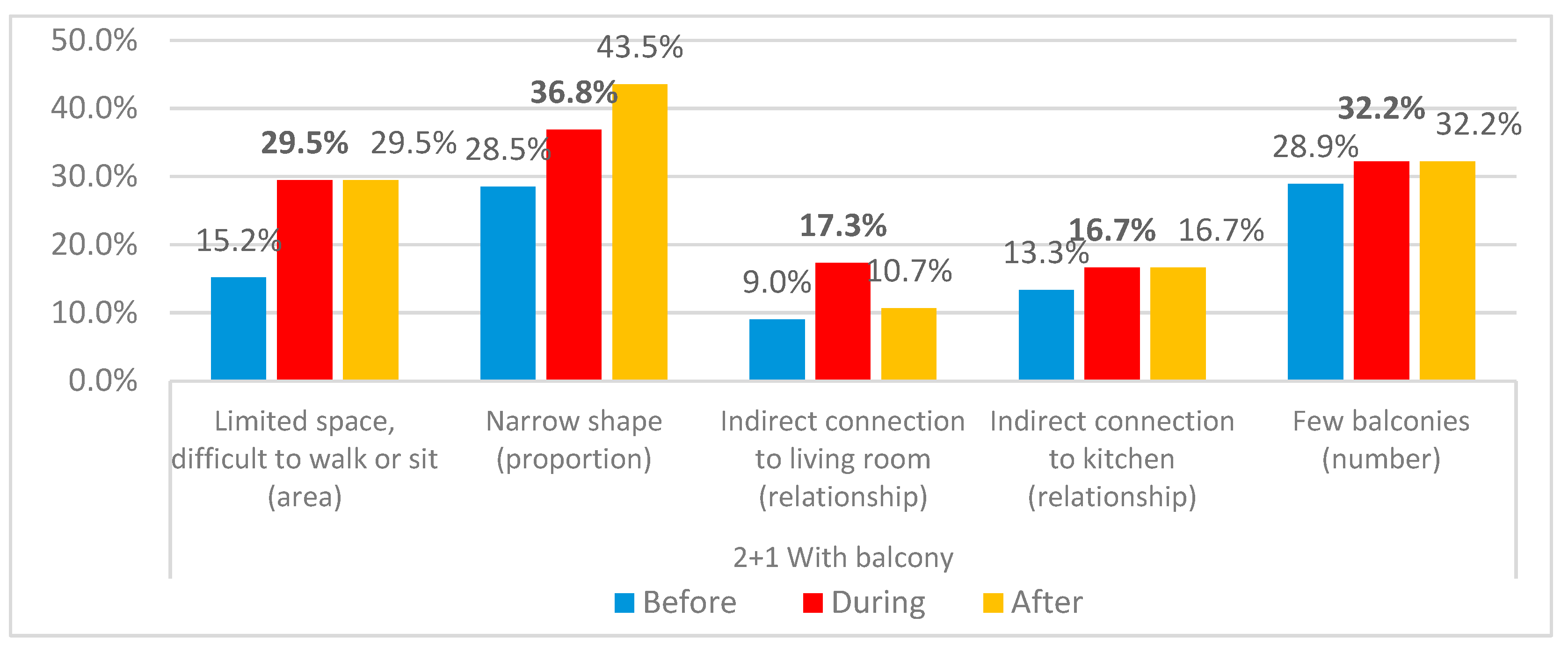

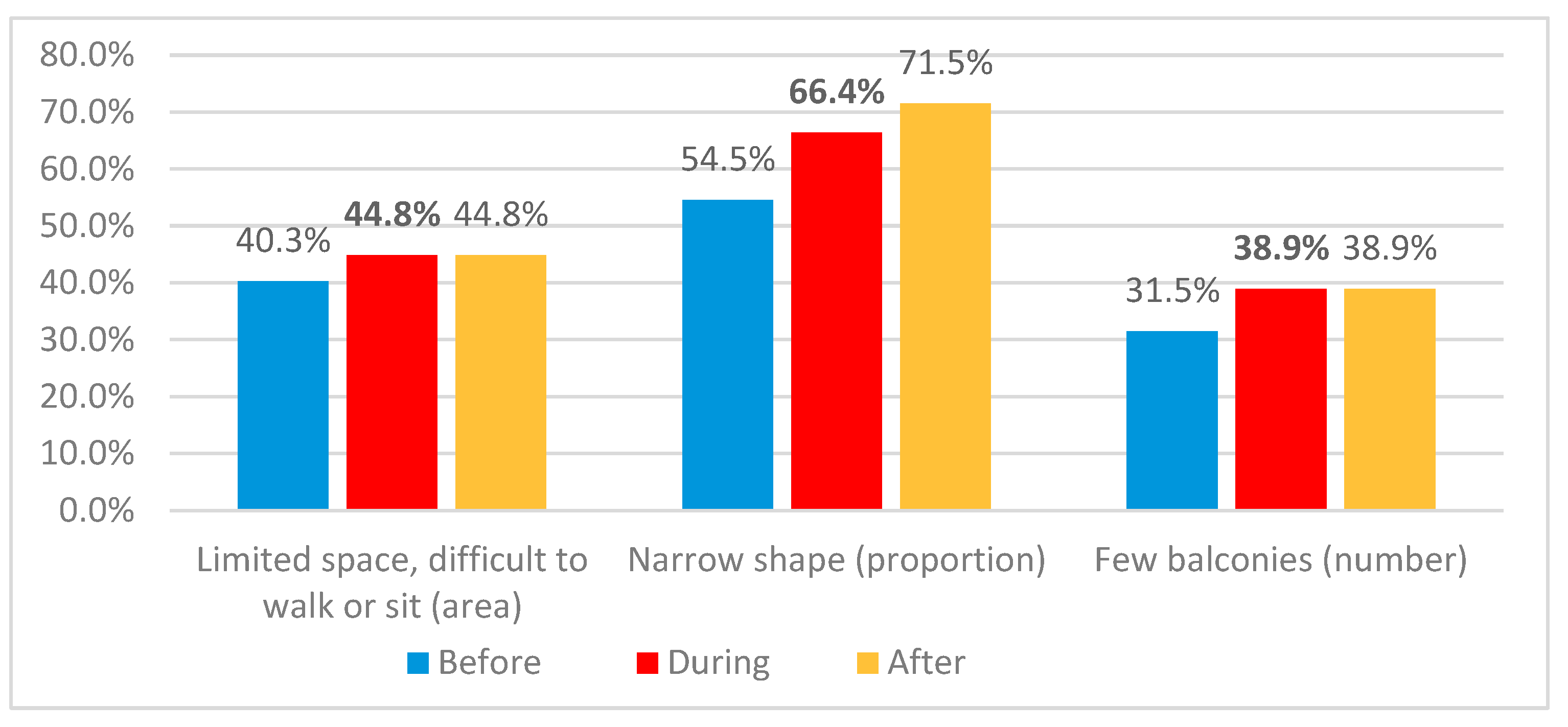

Figure 14.

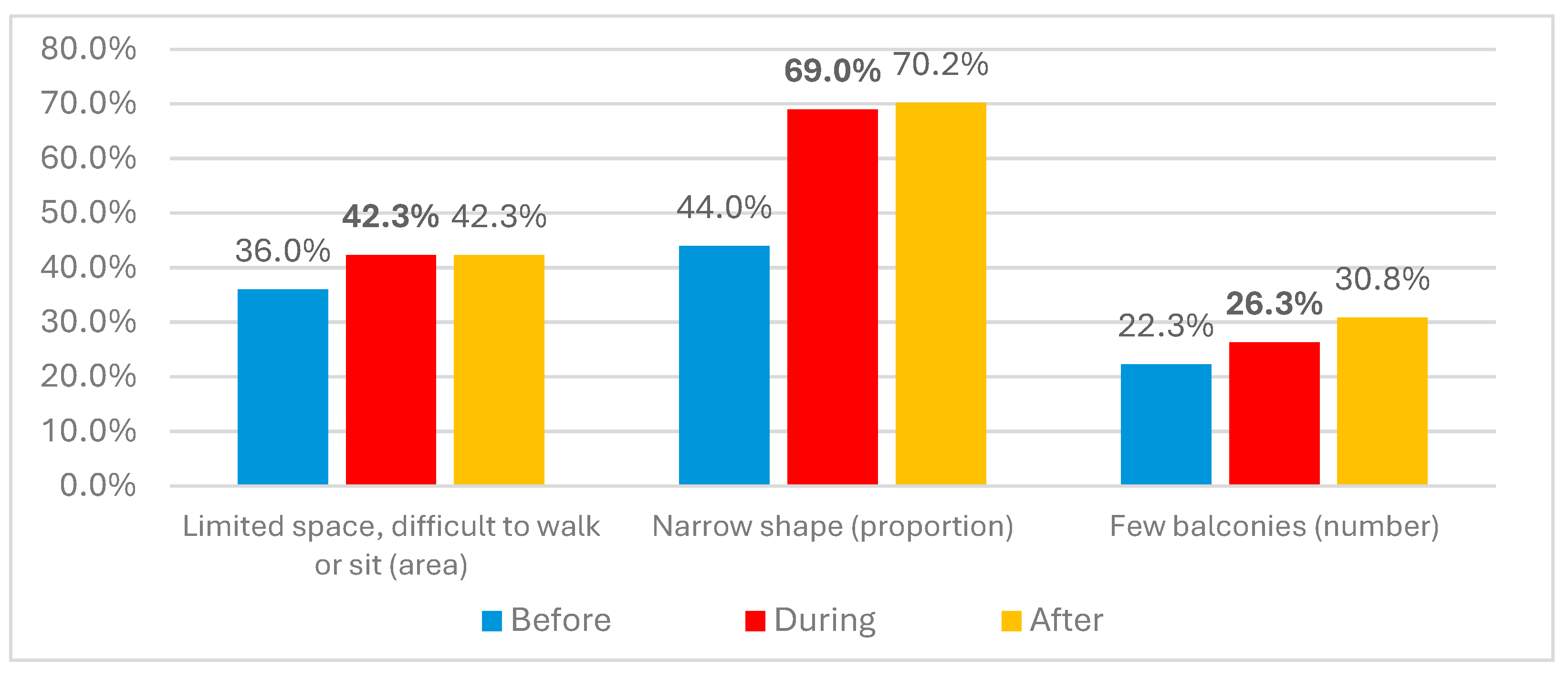

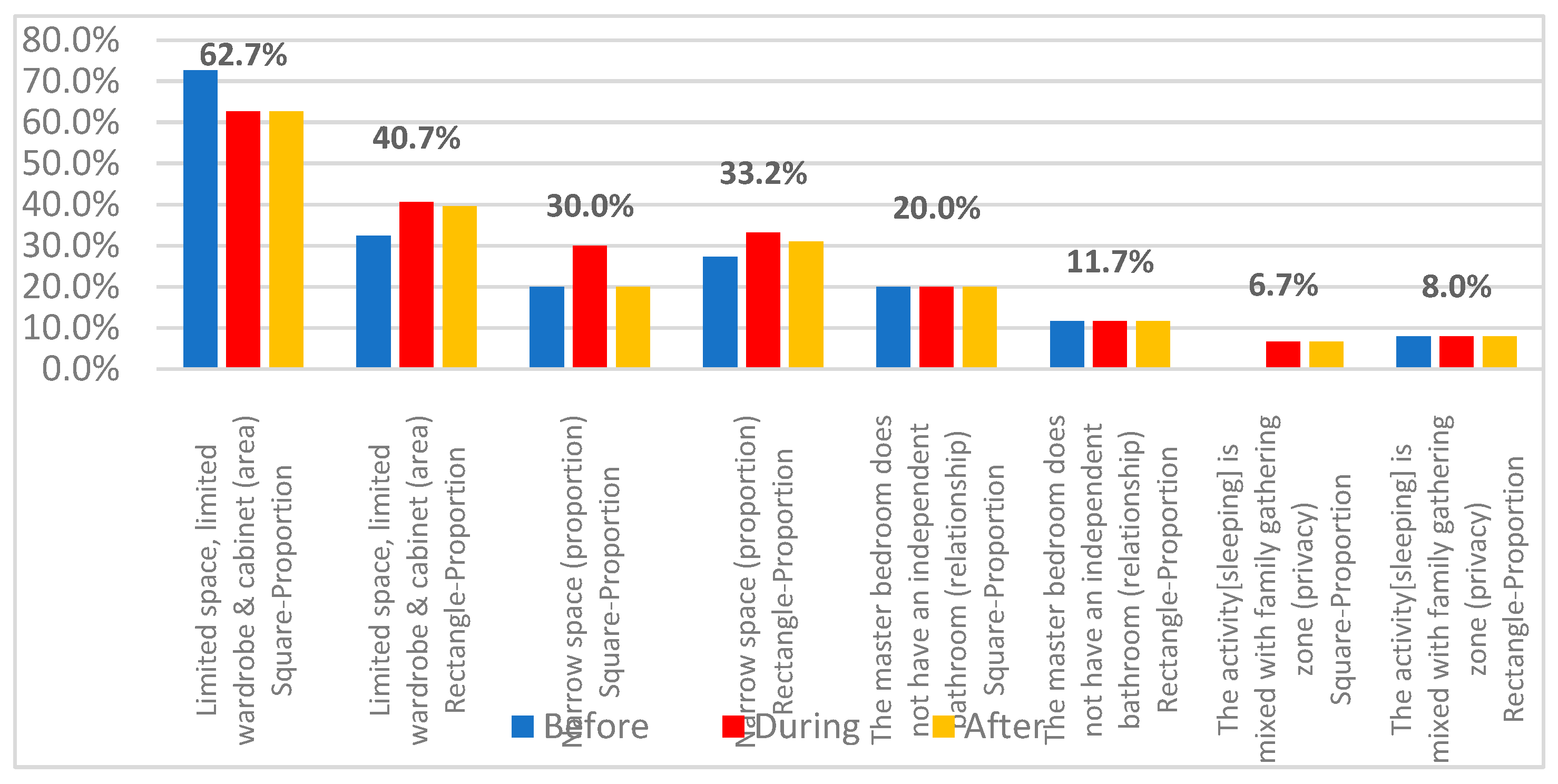

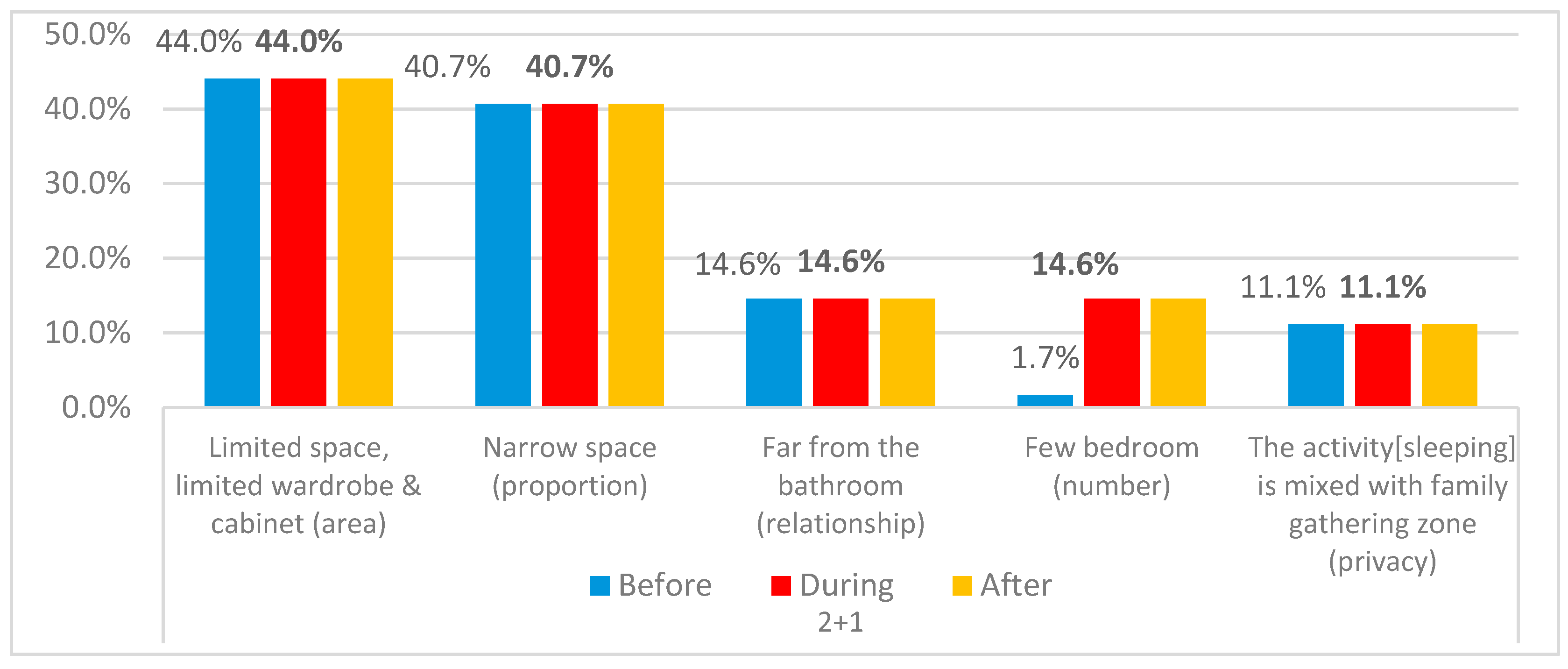

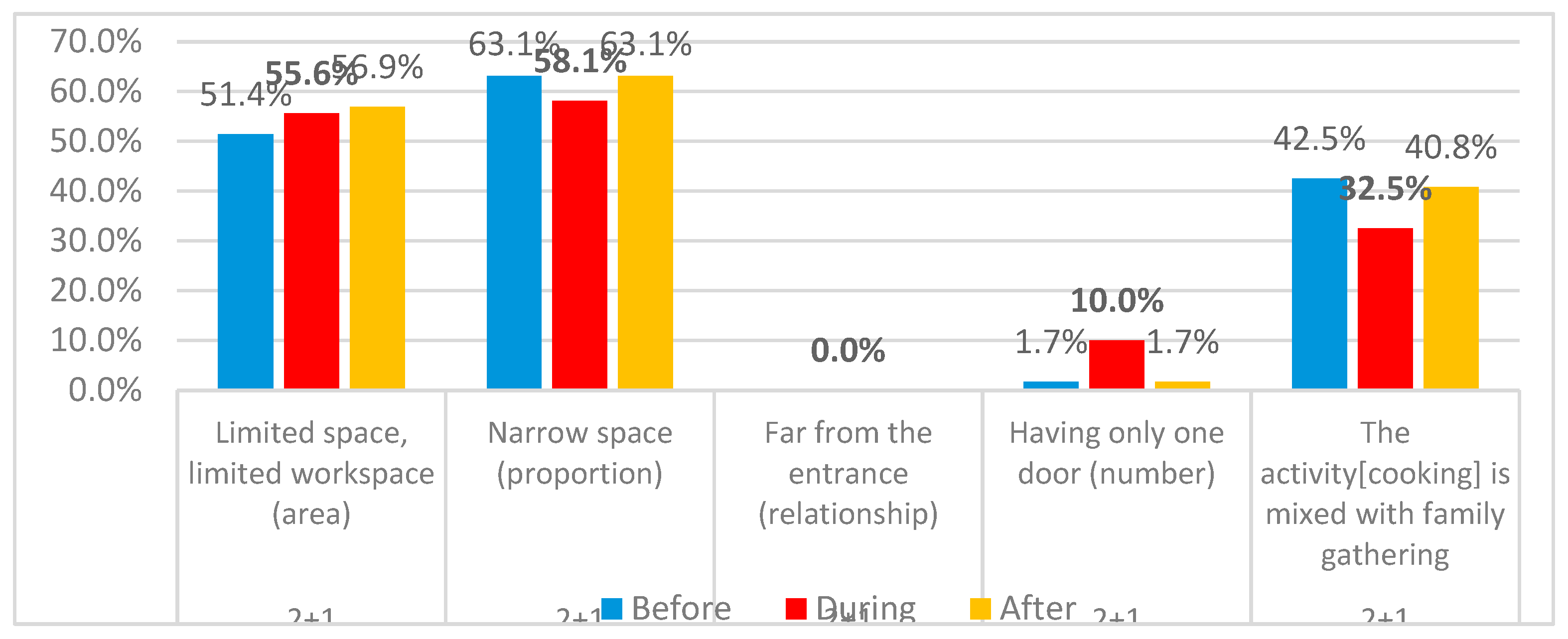

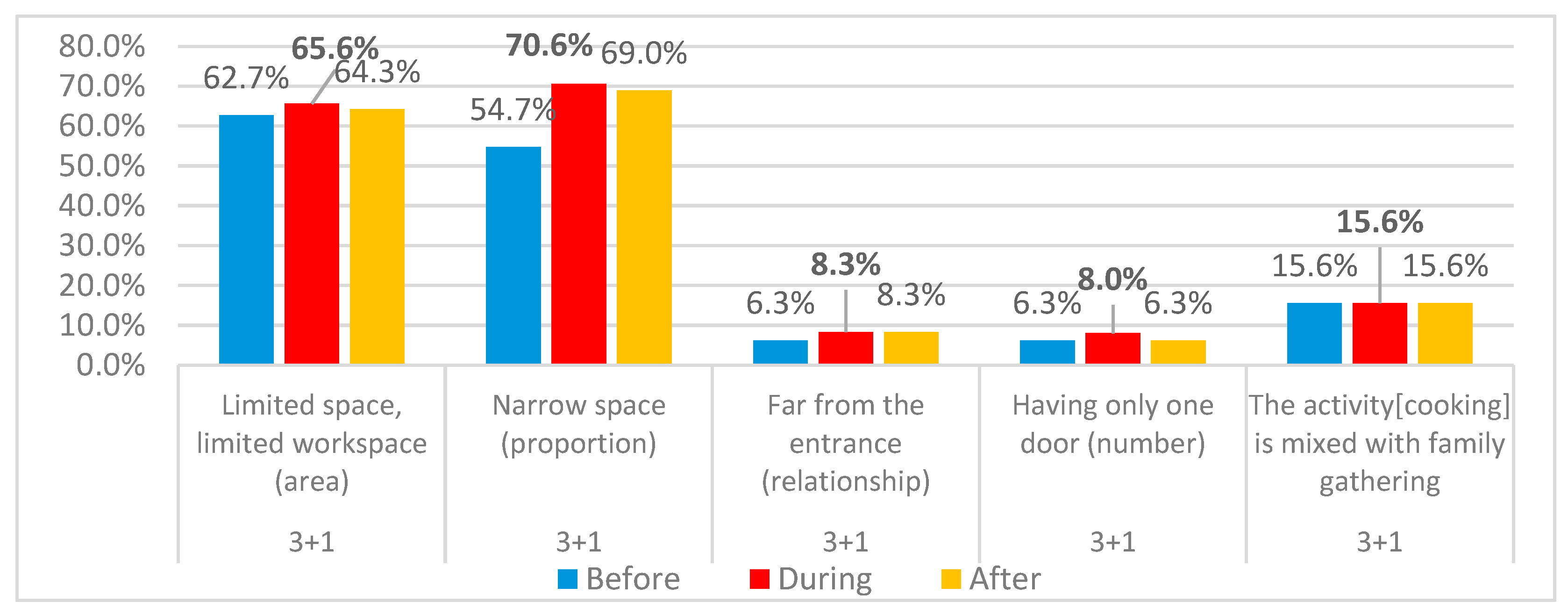

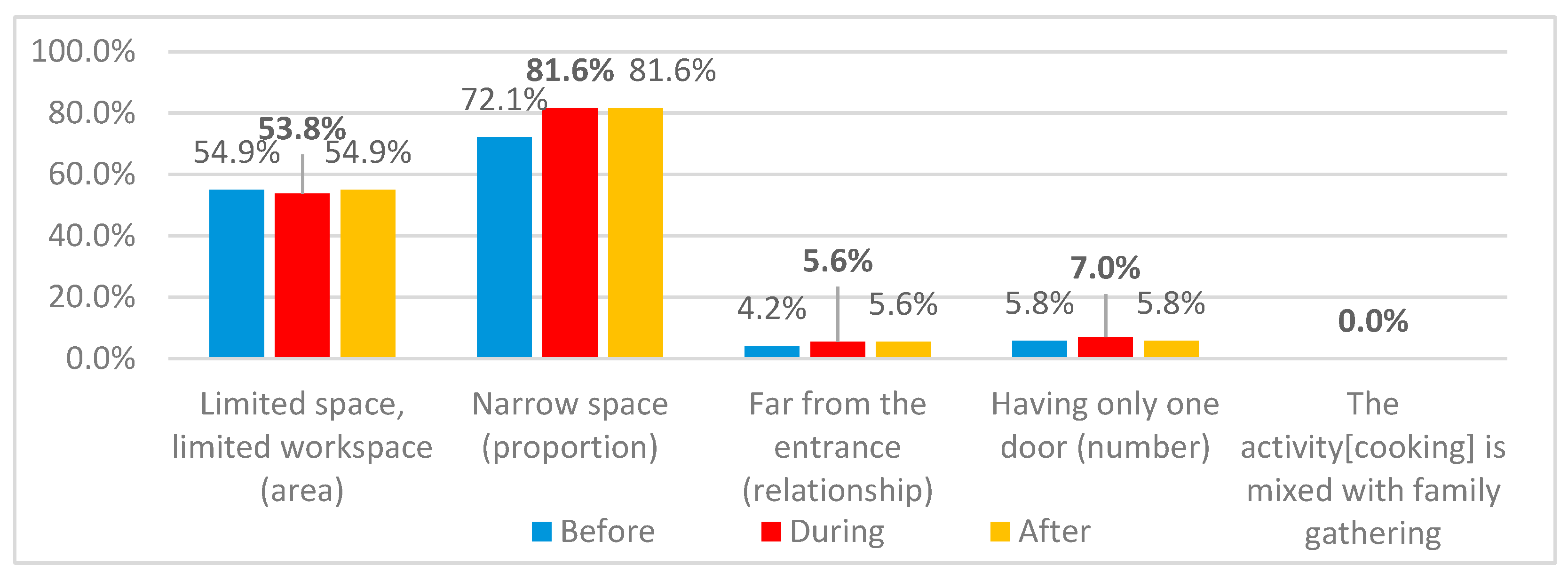

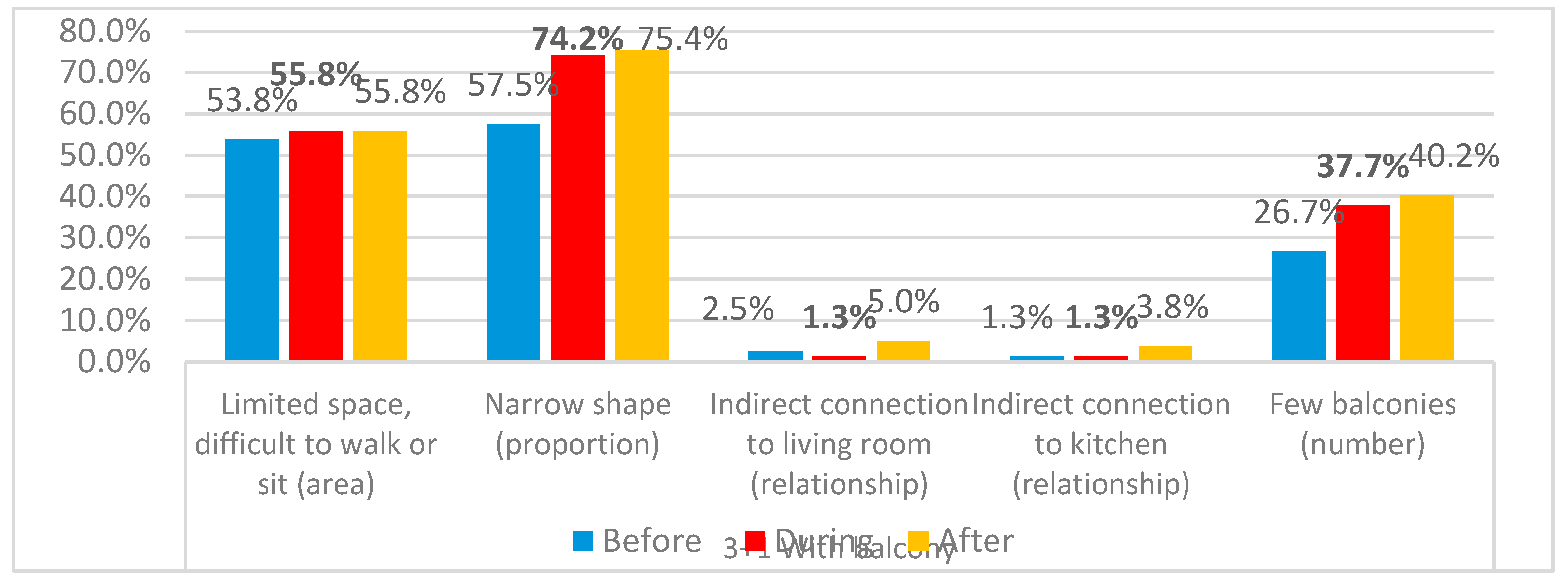

Main Reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of living rooms for both sizes .

Figure 14.

Main Reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of living rooms for both sizes .

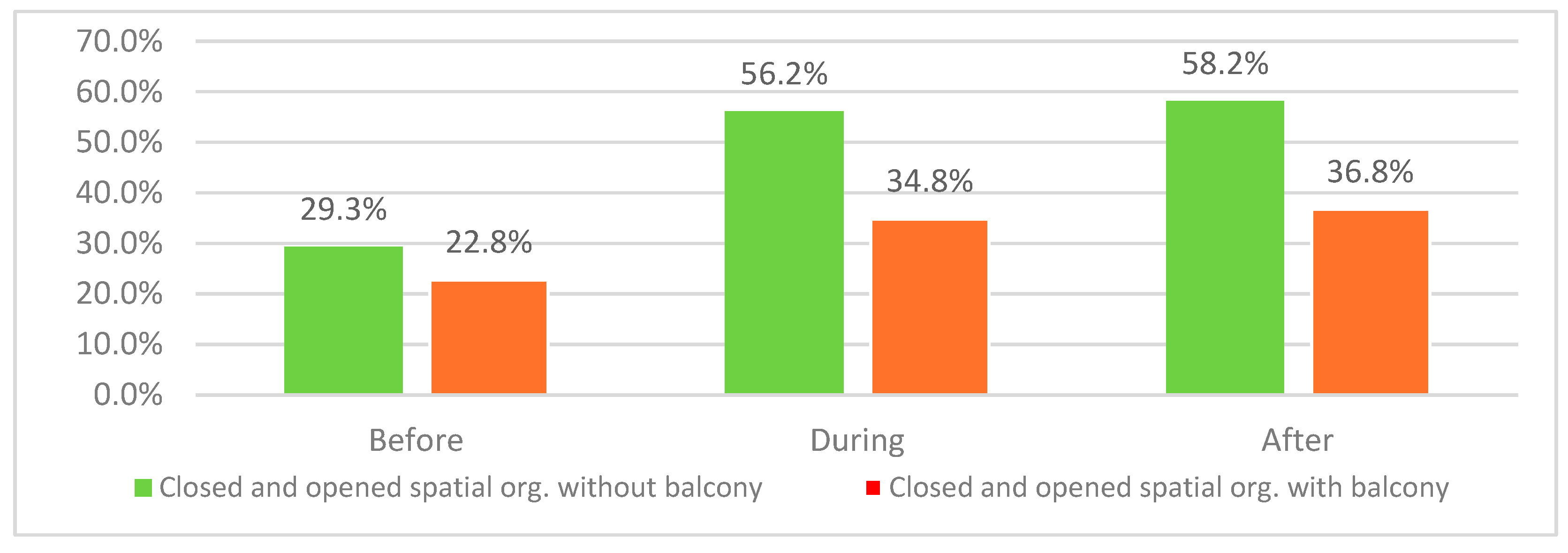

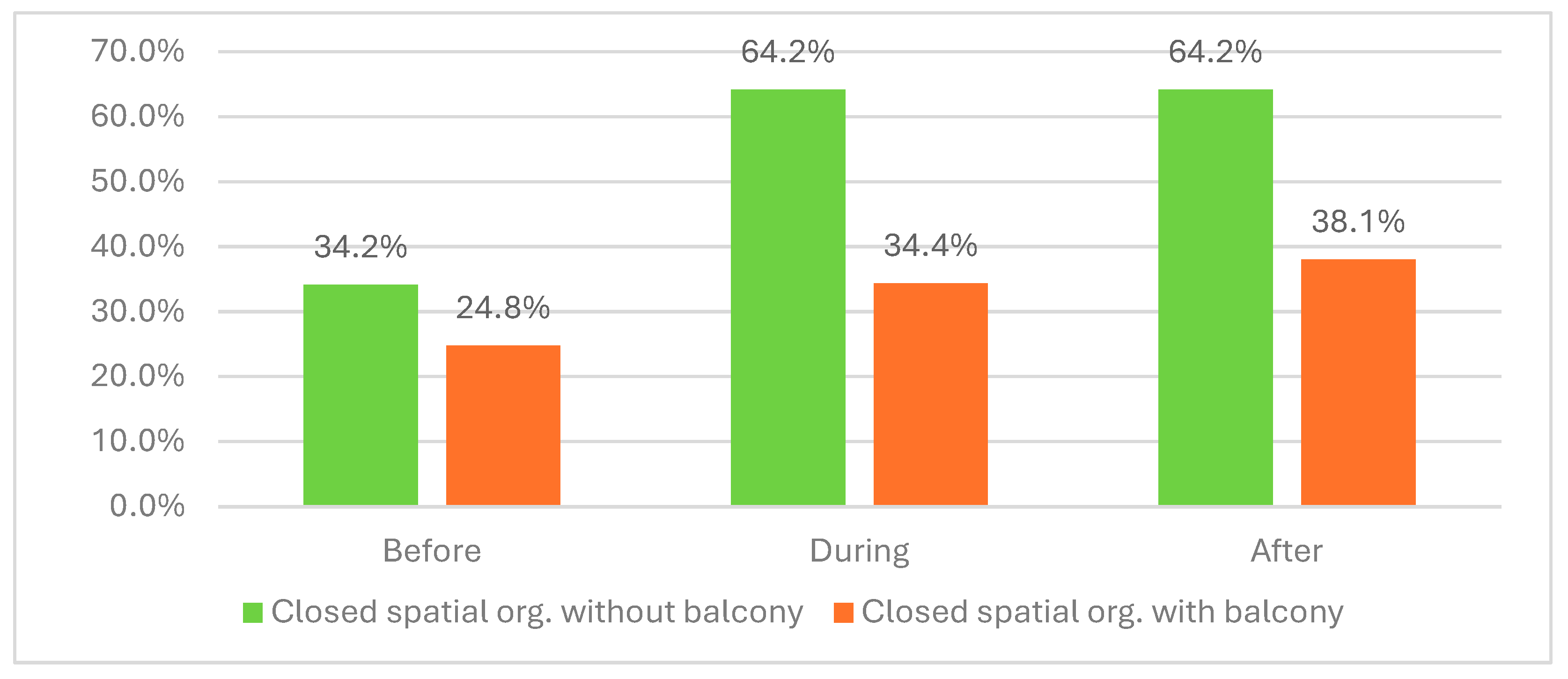

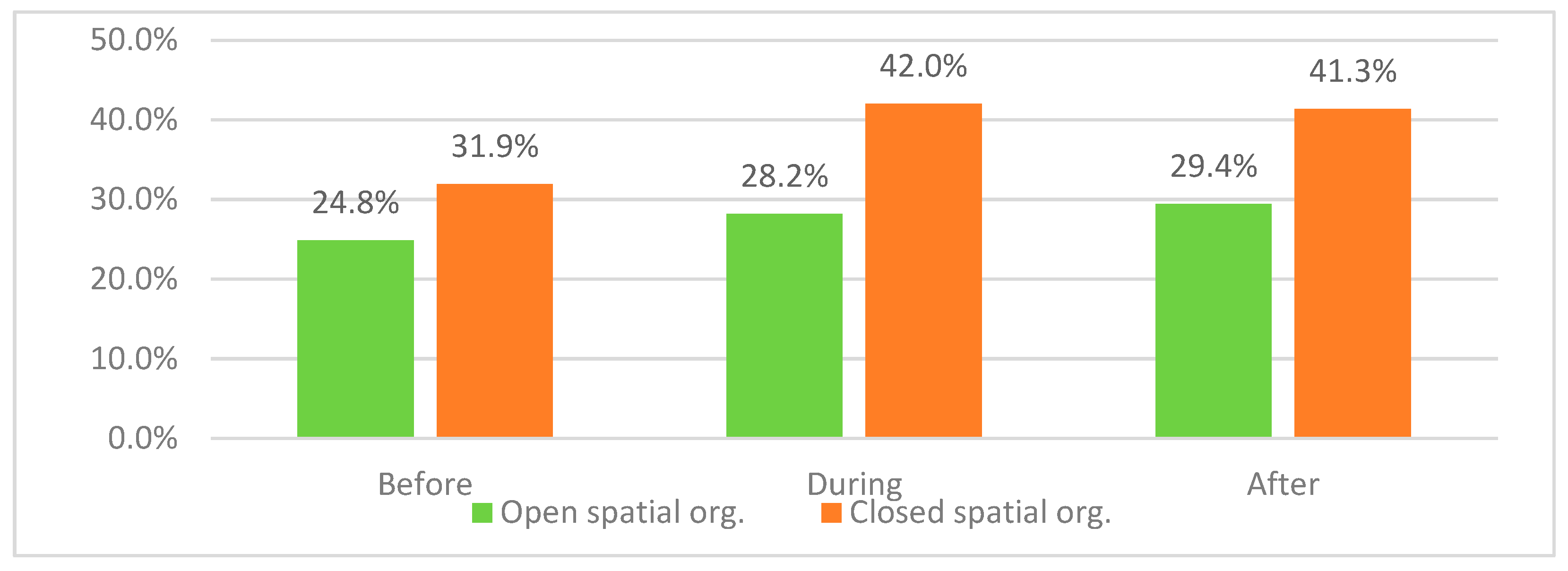

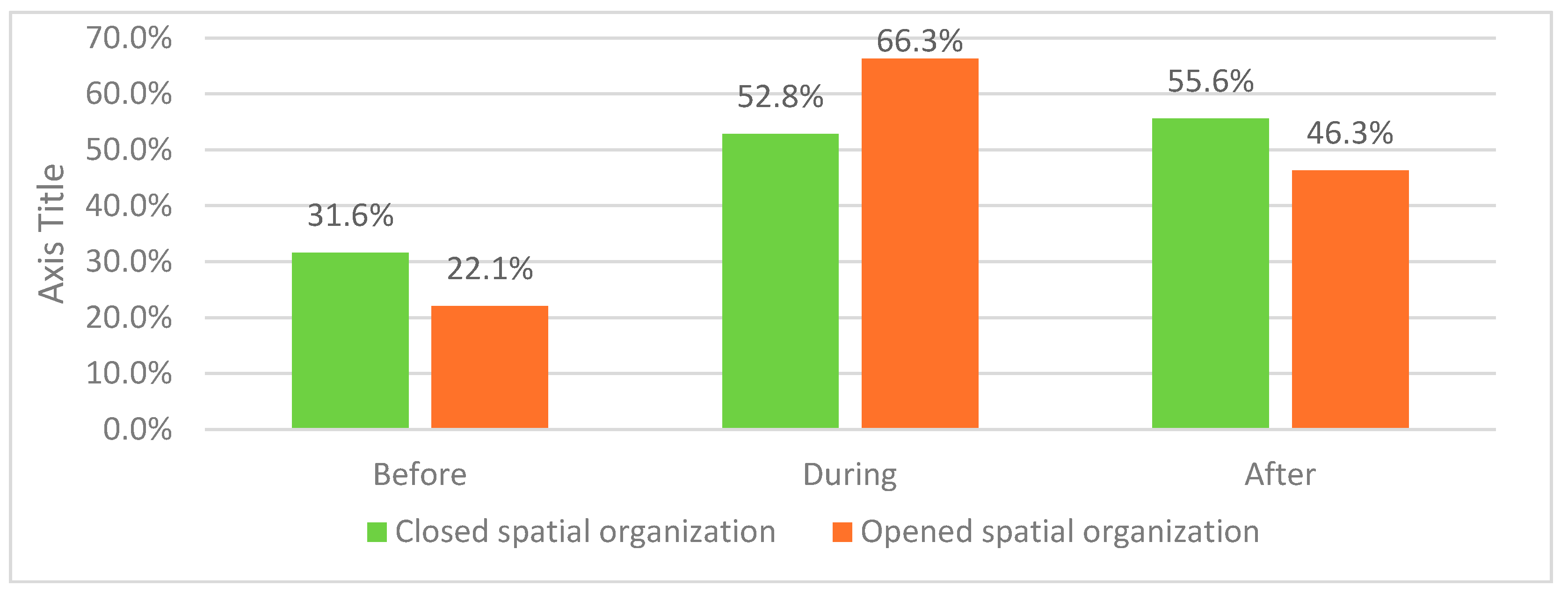

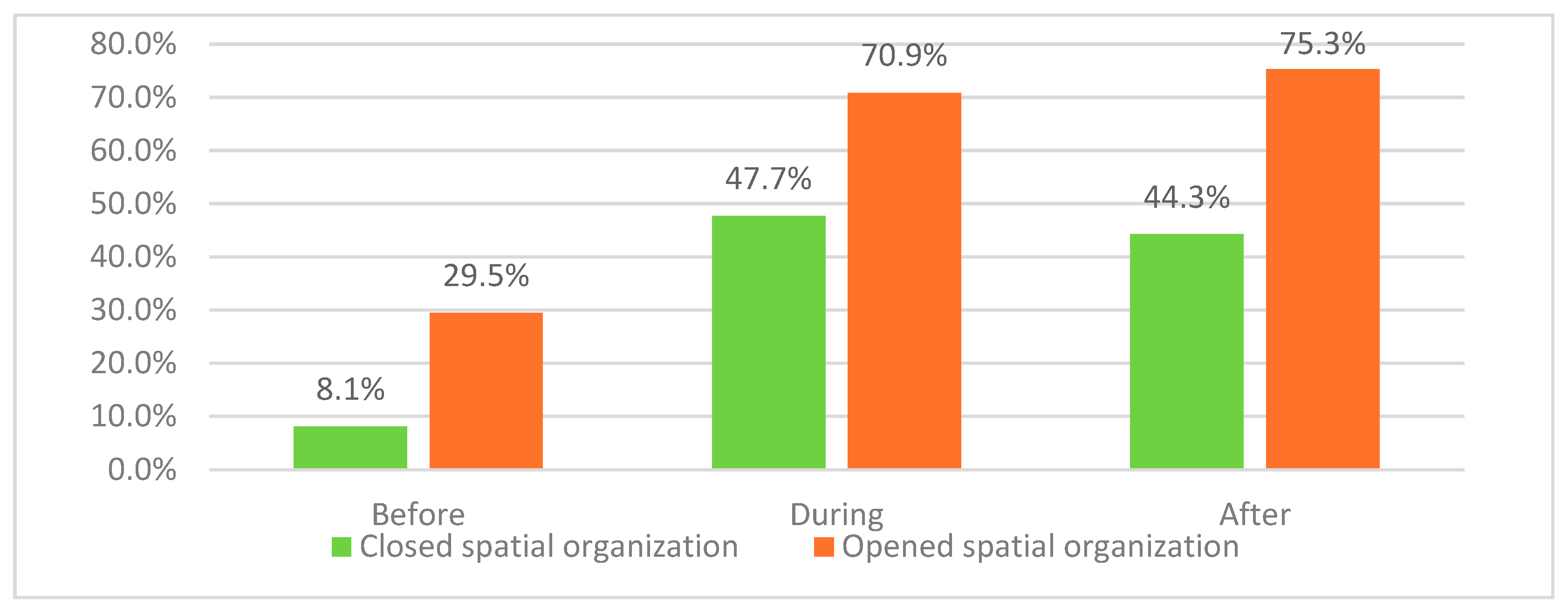

Figure 15.

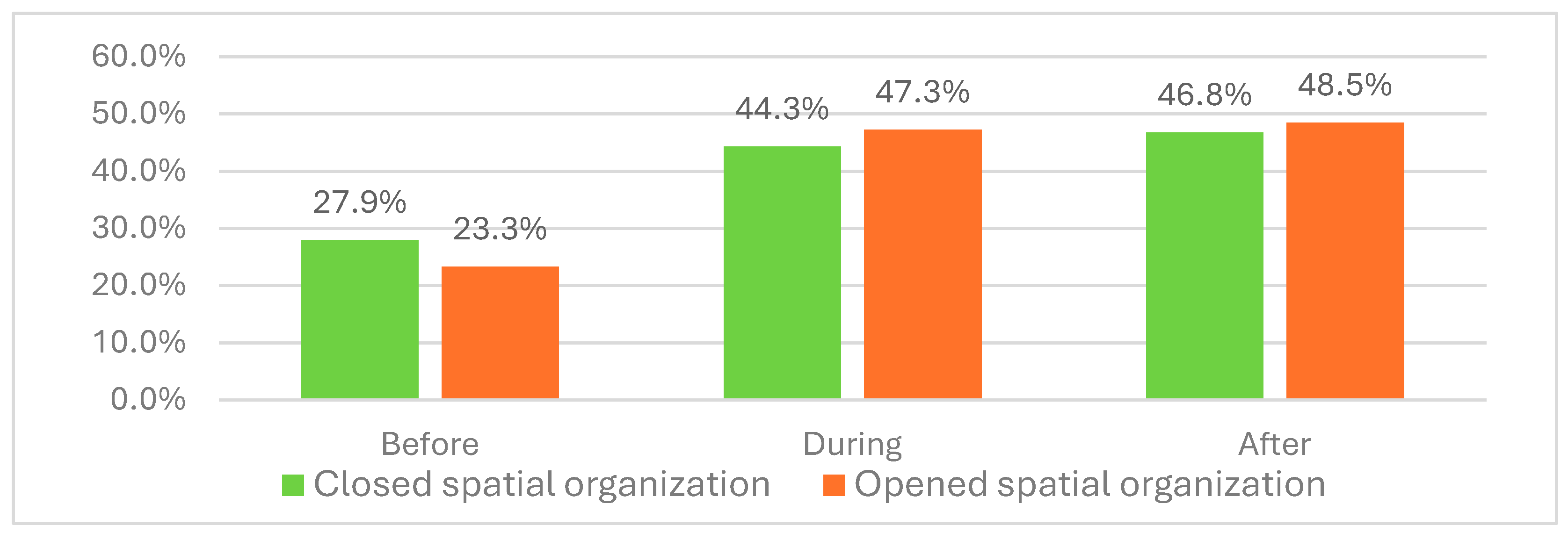

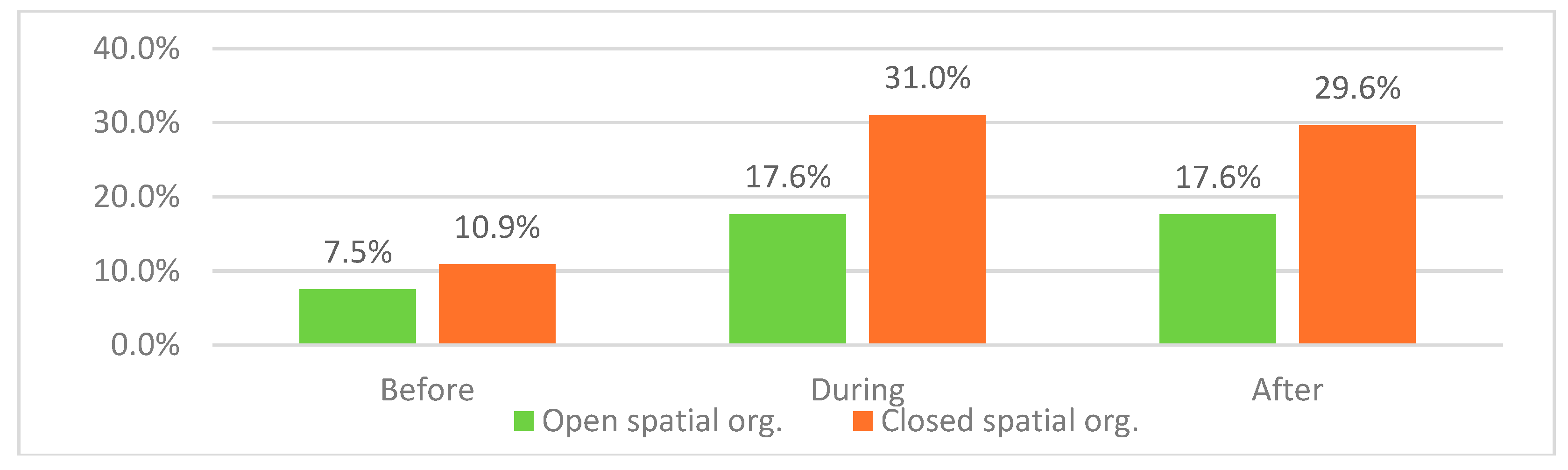

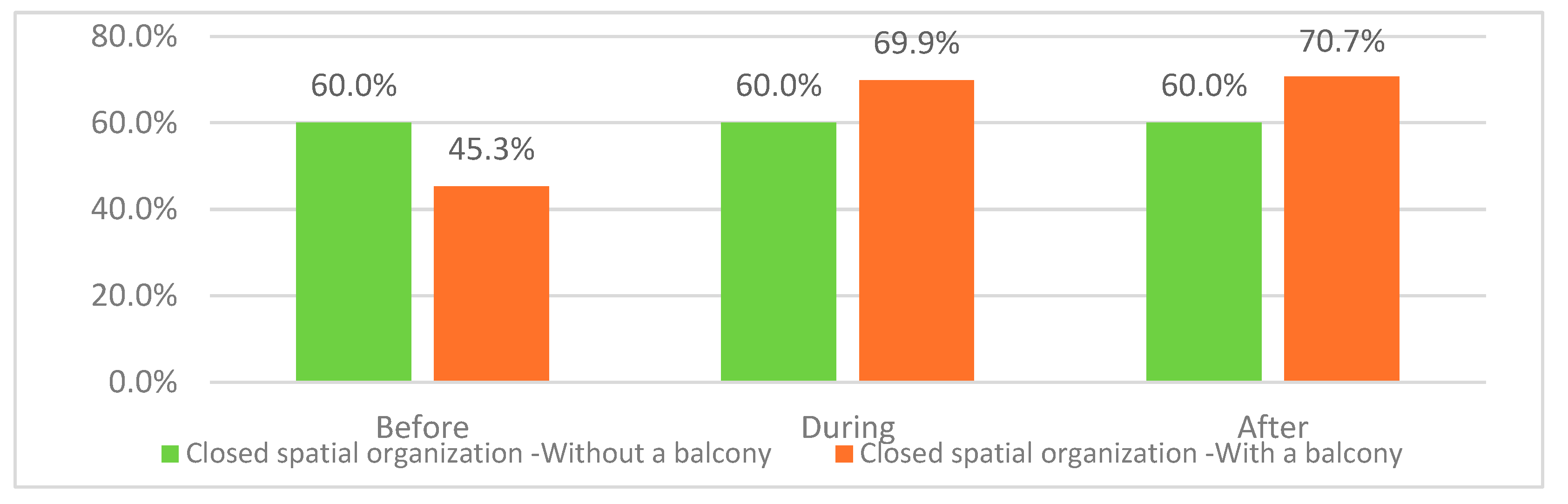

Change in dissatisfaction percentage in living rooms due to spatial organization.

Figure 15.

Change in dissatisfaction percentage in living rooms due to spatial organization.

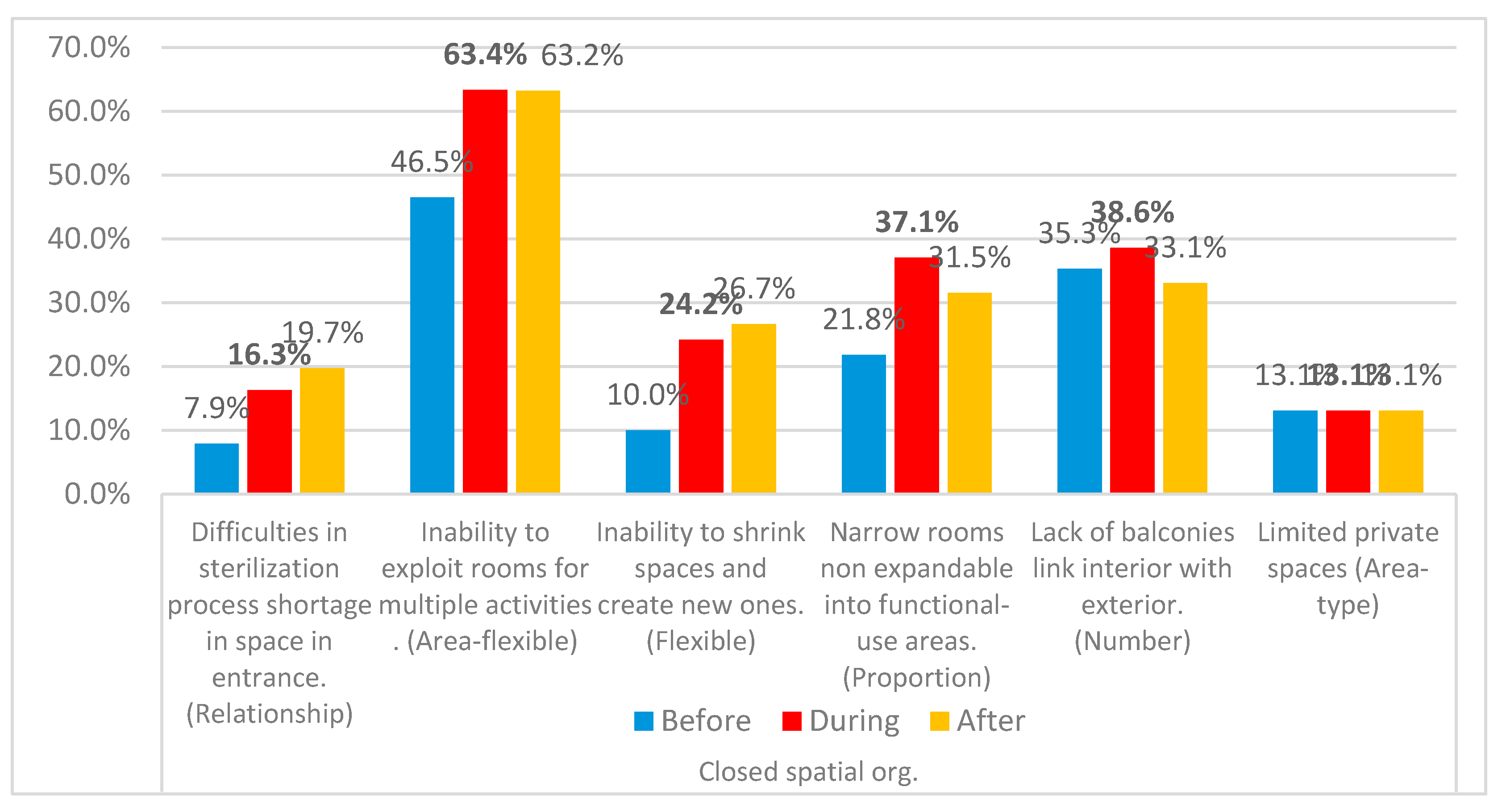

Figure 16.

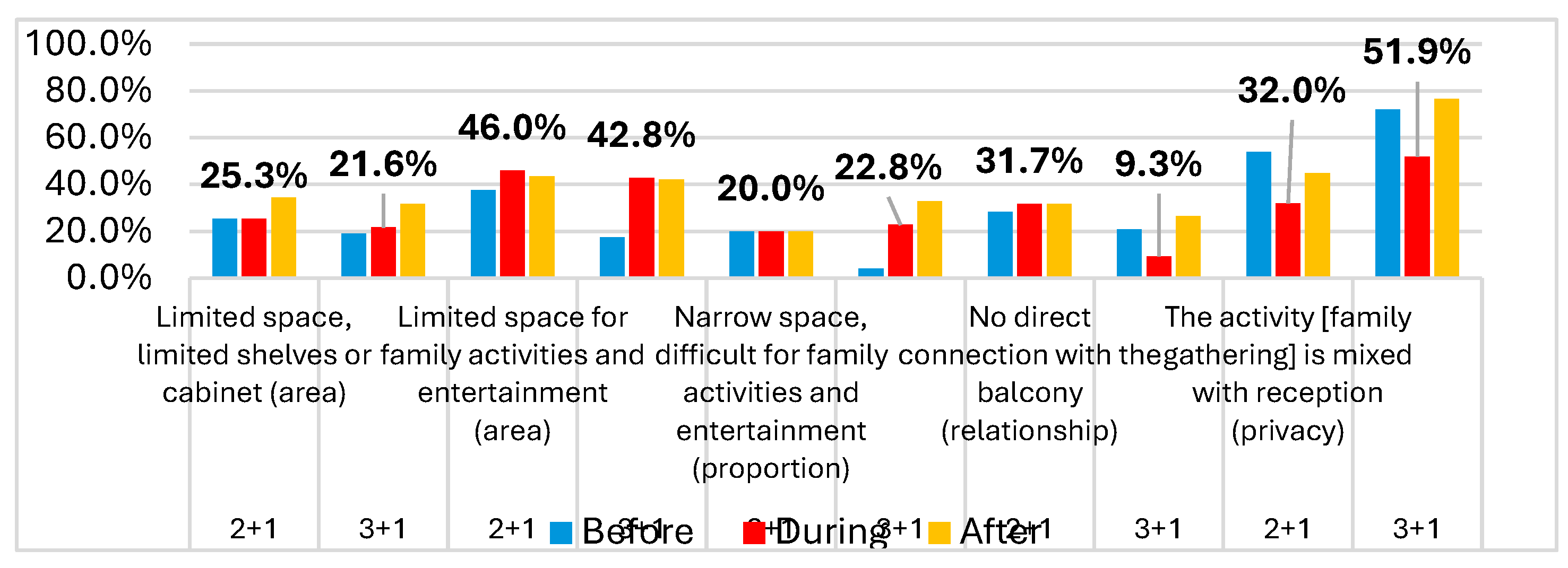

Reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of living rooms for the closed organizing.

Figure 16.

Reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of living rooms for the closed organizing.

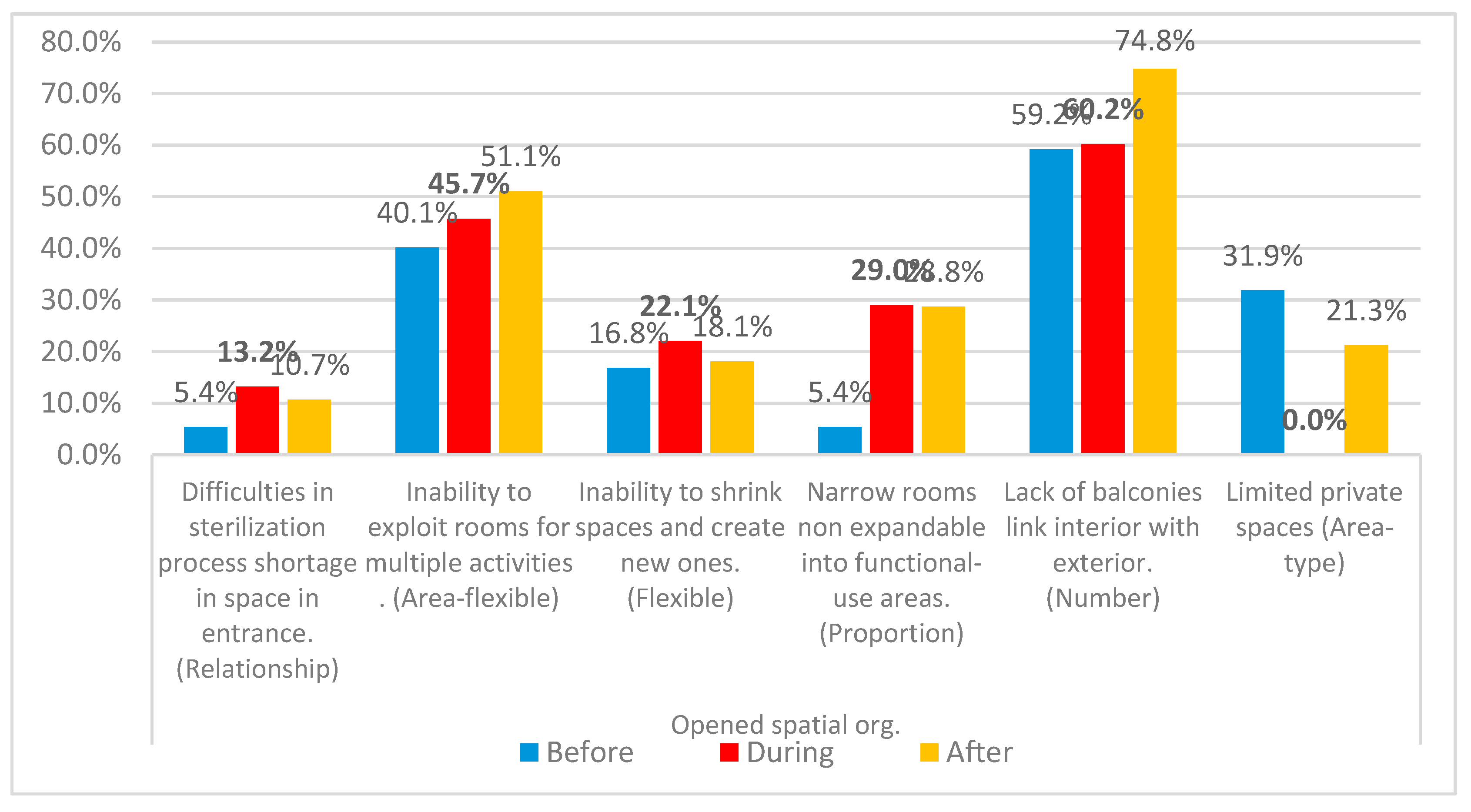

Figure 17.

Reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of living rooms for open organizing.

Figure 17.

Reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of living rooms for open organizing.

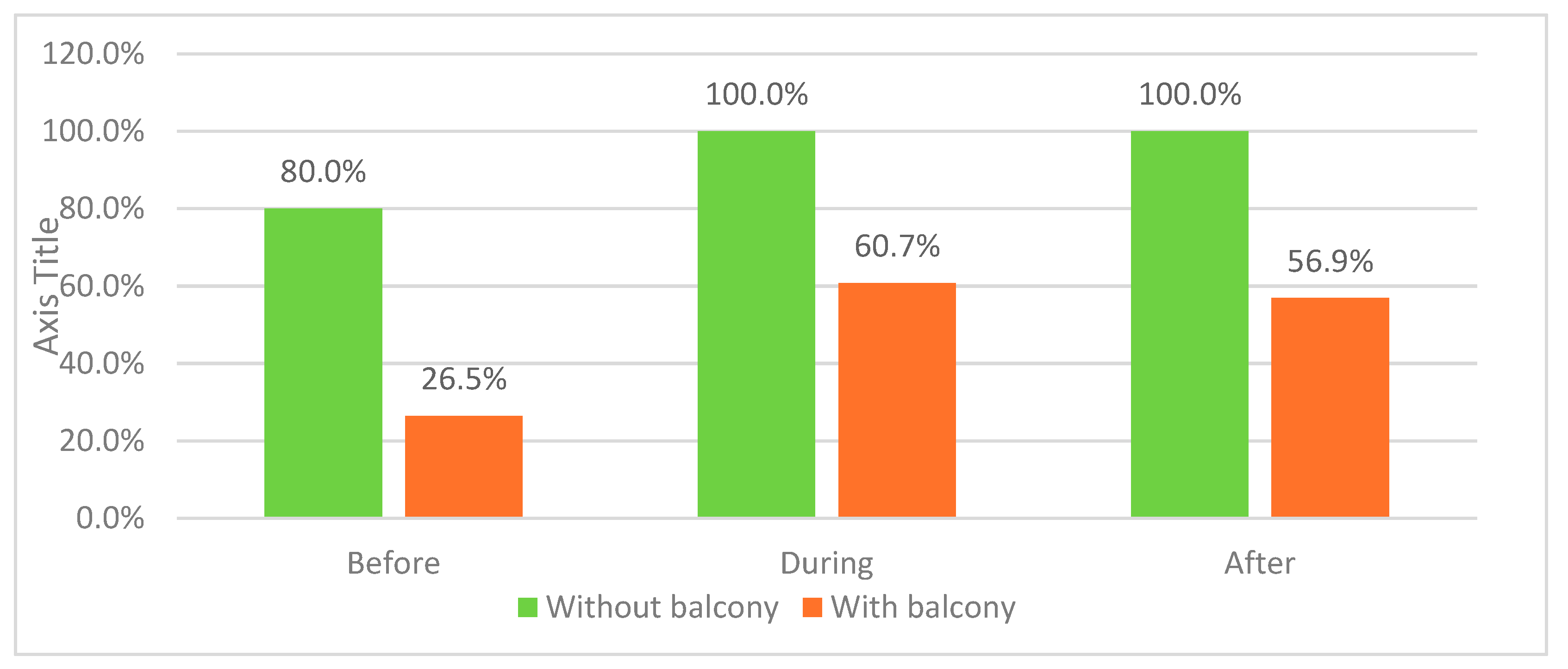

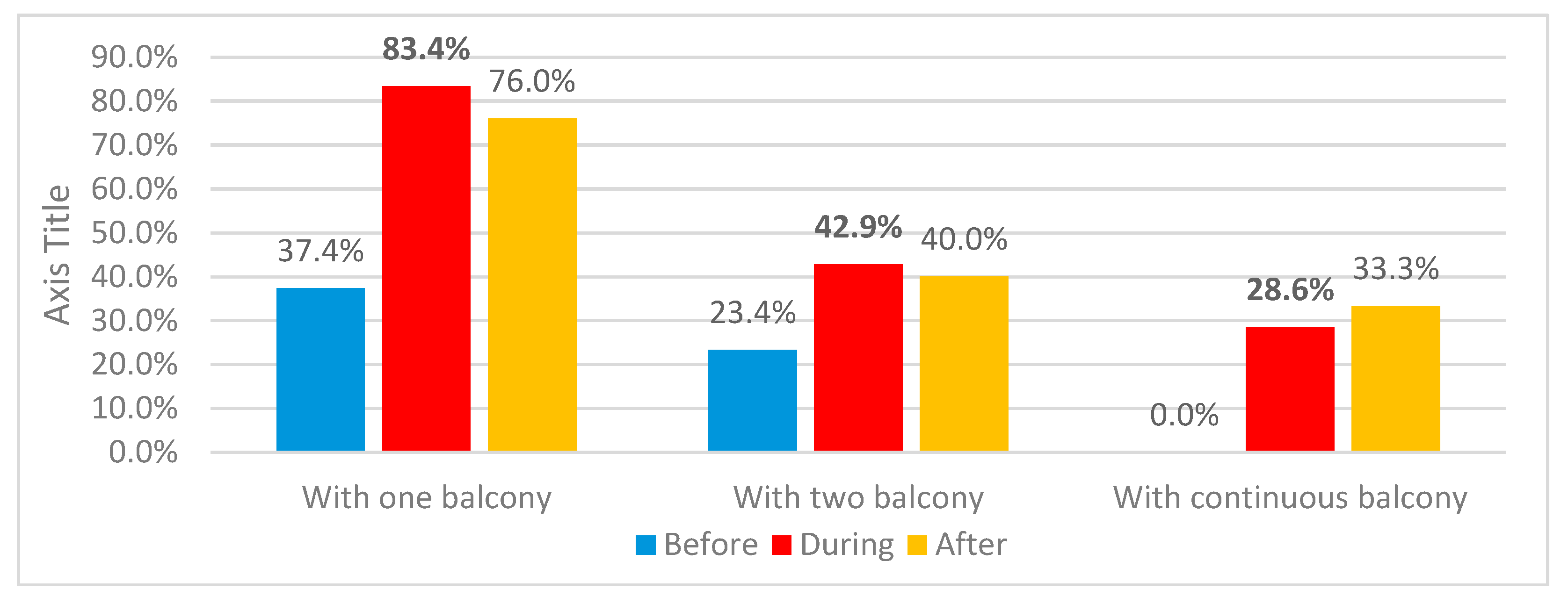

Figure 18.

Change in dissatisfaction due to availability of living rooms’ balcony .

Figure 18.

Change in dissatisfaction due to availability of living rooms’ balcony .

Figure 19.

Reasons for Changes in dissatisfaction of living rooms without balconies.

Figure 19.

Reasons for Changes in dissatisfaction of living rooms without balconies.

Figure 20.

Reasons for Changes in dissatisfaction of living rooms with balconies.

Figure 20.

Reasons for Changes in dissatisfaction of living rooms with balconies.

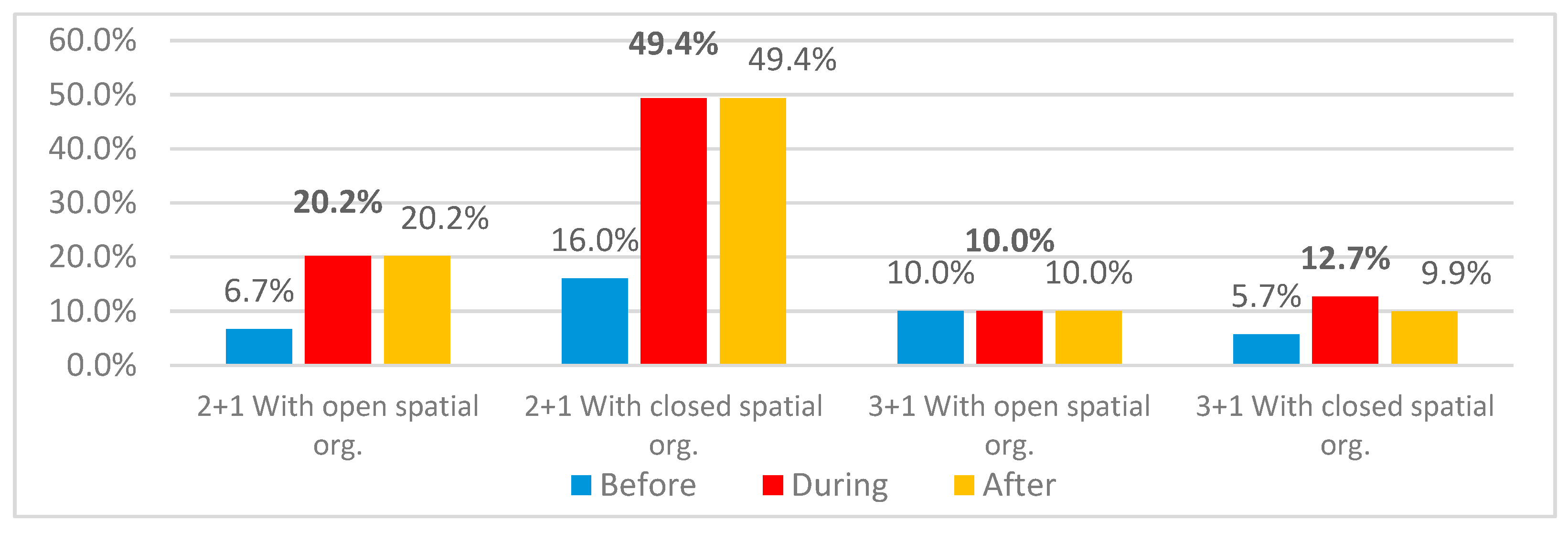

Figure 21.

Change in dissatisfaction due to combined effect of spatial organization and availability of living rooms’ balcony for closed organization. .

Figure 21.

Change in dissatisfaction due to combined effect of spatial organization and availability of living rooms’ balcony for closed organization. .

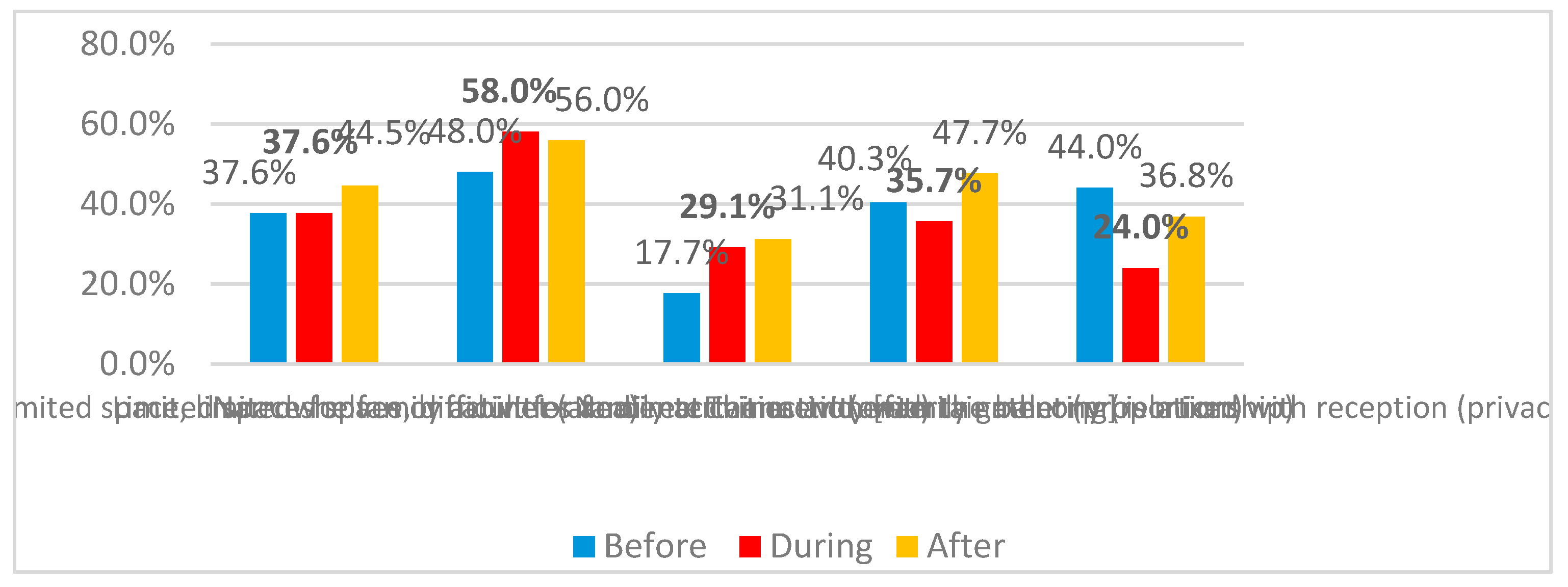

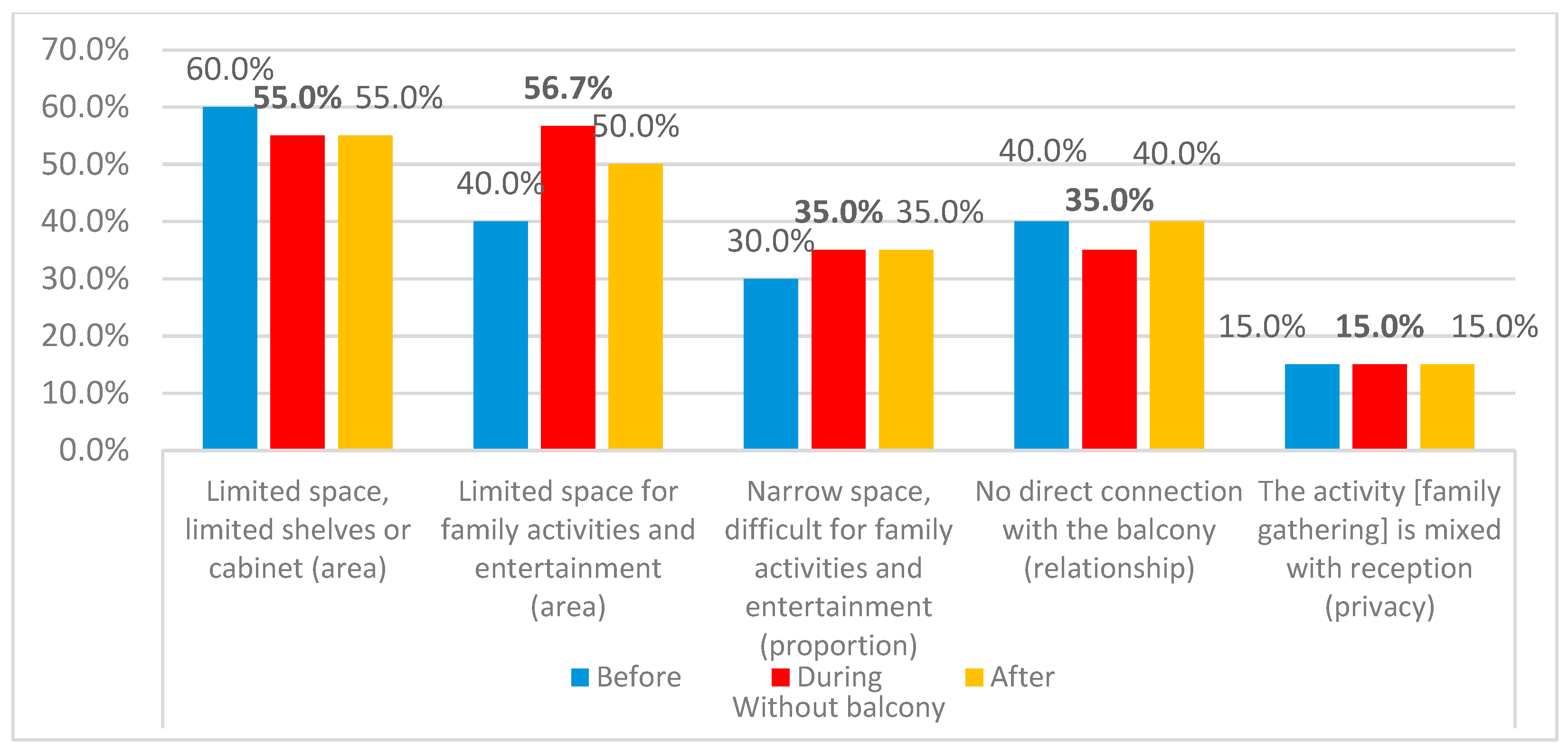

Figure 22.

Reasons for change in dissatisfaction in absence of balconies and closed organization.

Figure 22.

Reasons for change in dissatisfaction in absence of balconies and closed organization.

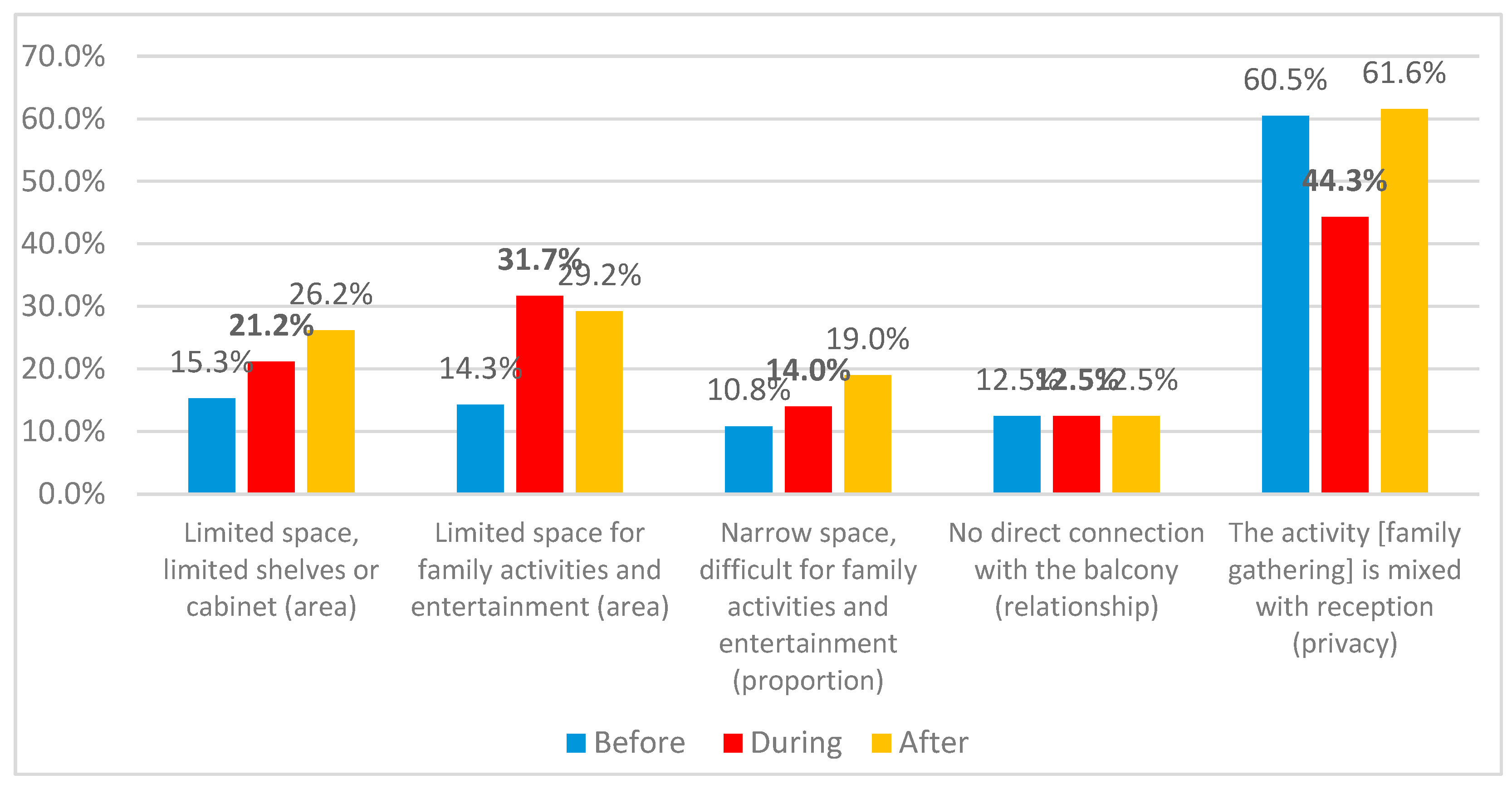

Figure 23.

Reasons for change in dissatisfaction in existence of balconies and closed organization.

Figure 23.

Reasons for change in dissatisfaction in existence of balconies and closed organization.

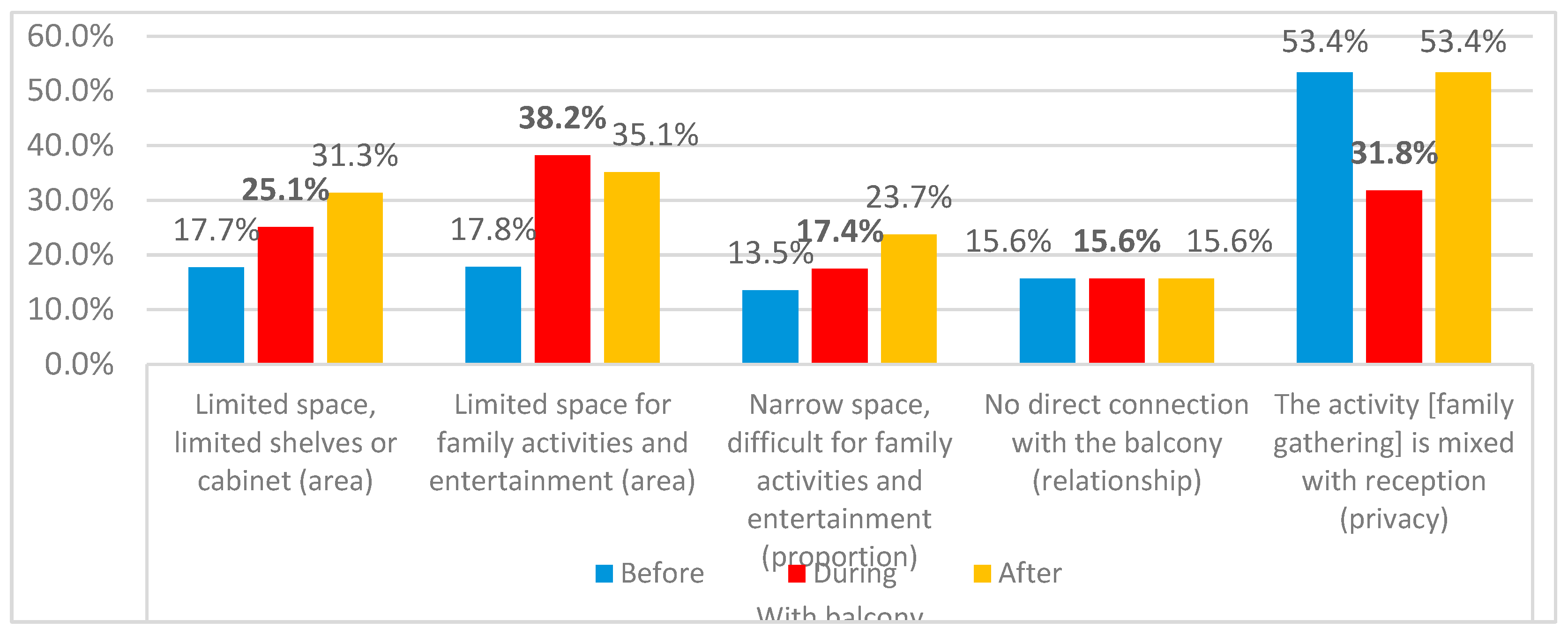

Figure 24.

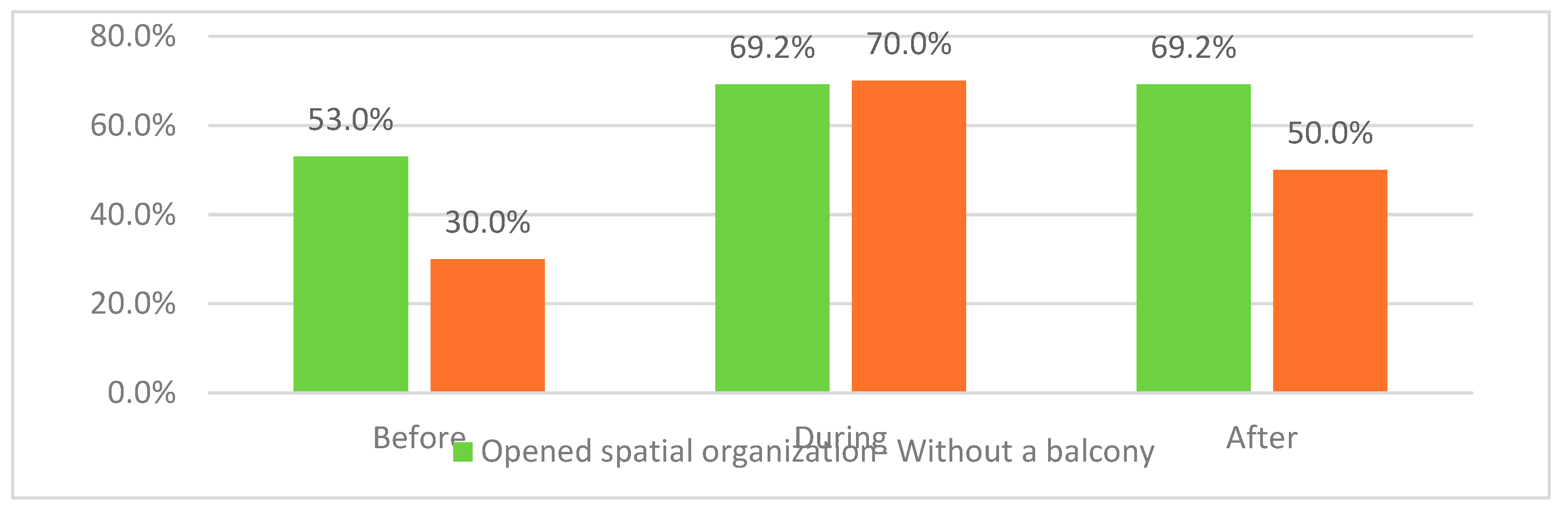

Change in dissatisfaction due to combined effect of spatial organization and availability of living rooms’ balcony for open organization.

Figure 24.

Change in dissatisfaction due to combined effect of spatial organization and availability of living rooms’ balcony for open organization.

Figure 25.

Reasons for change in dissatisfaction due to absence of balconies and opened organization.

Figure 25.

Reasons for change in dissatisfaction due to absence of balconies and opened organization.

Figure 26.

Reasons for change in dissatisfaction due to absence of balconies and opened spatial organization.

Figure 26.

Reasons for change in dissatisfaction due to absence of balconies and opened spatial organization.

Figure 27.

Dissatisfaction regarding the reception activities and needs.

Figure 27.

Dissatisfaction regarding the reception activities and needs.

Figure 28.

Main reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of reception rooms.

Figure 28.

Main reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of reception rooms.

Figure 29.

Change in dissatisfaction percentage of dining activity during the three stages.

Figure 29.

Change in dissatisfaction percentage of dining activity during the three stages.

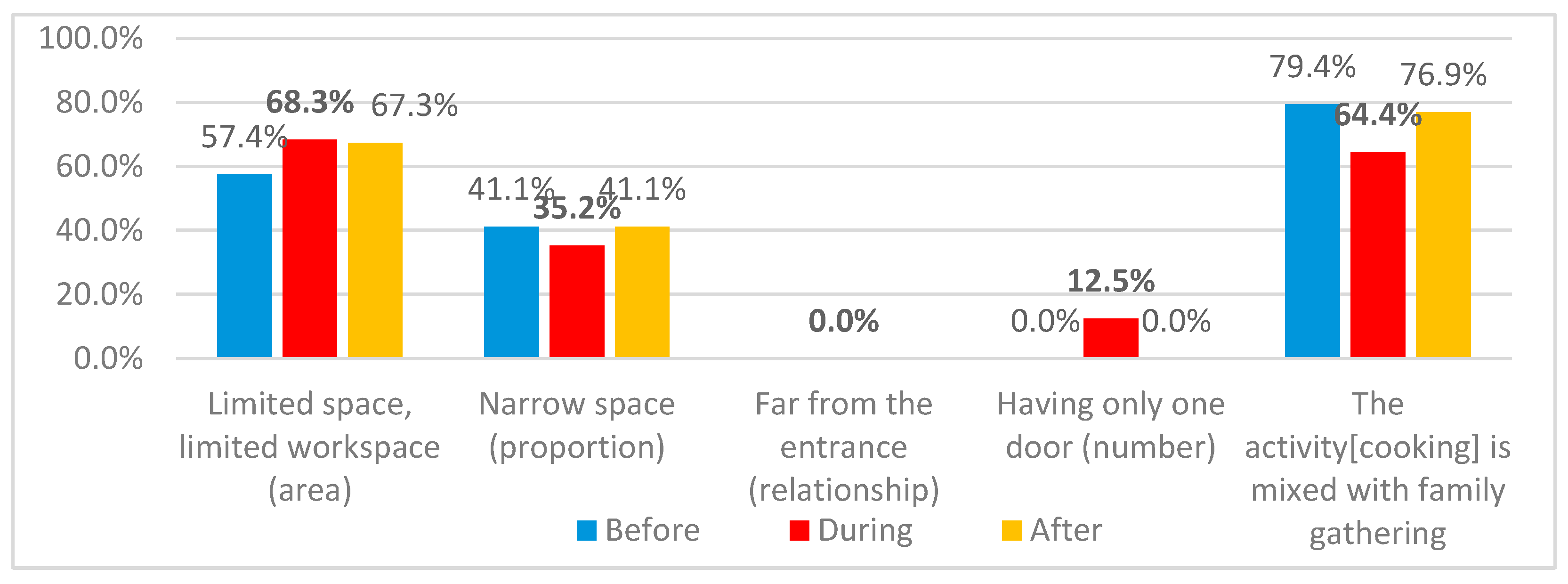

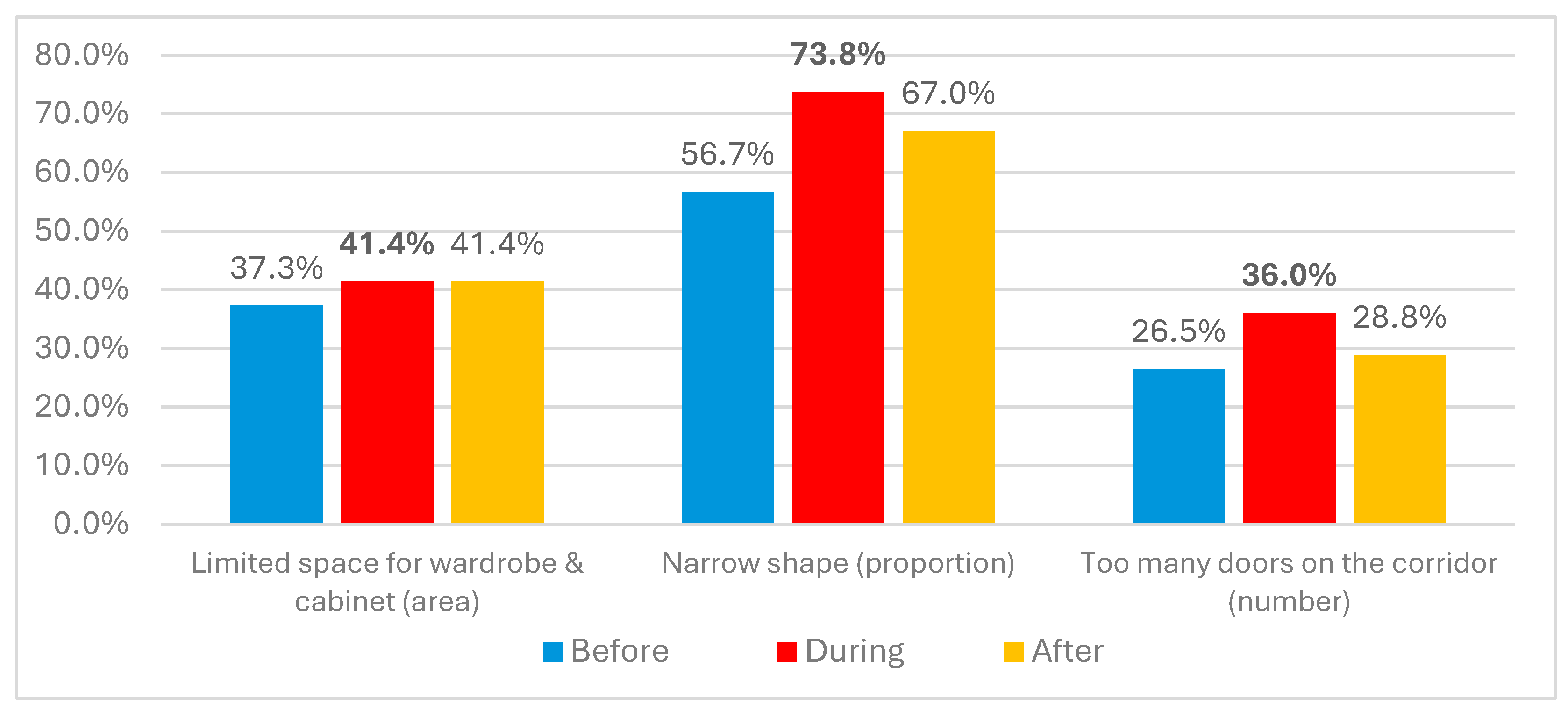

Figure 30.

Main reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of family dining space.

Figure 30.

Main reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of family dining space.

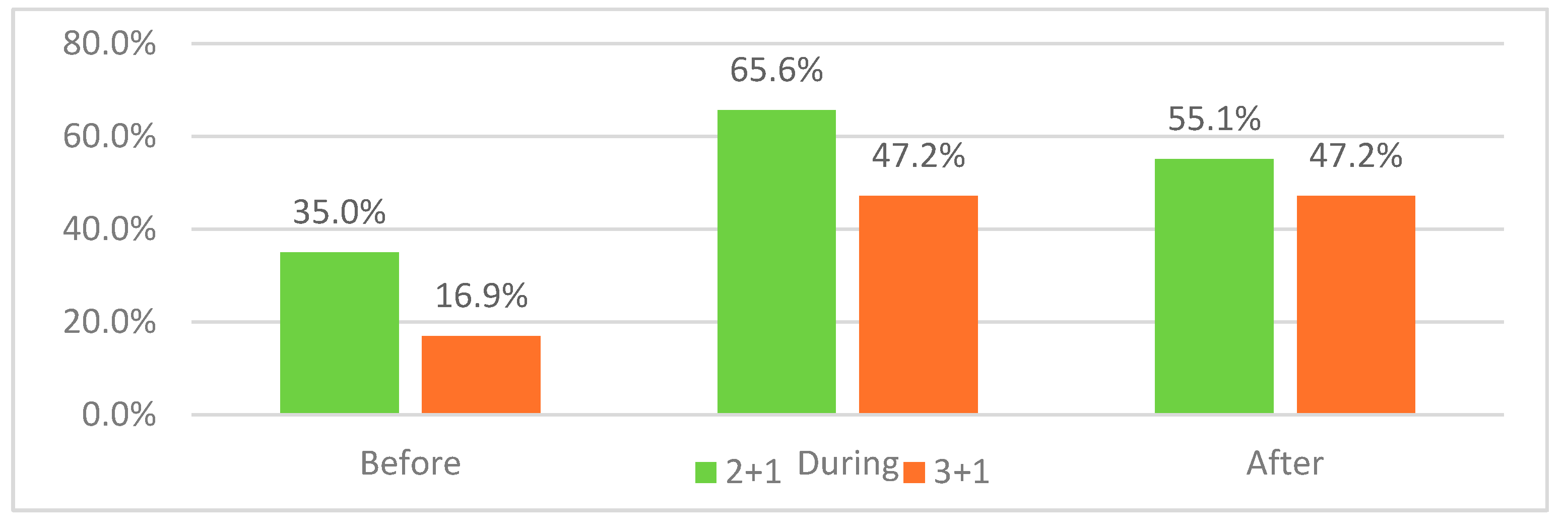

Figure 31.

Dissatisfaction differences for family dining between 2+1 and 3+1 categories.

Figure 31.

Dissatisfaction differences for family dining between 2+1 and 3+1 categories.

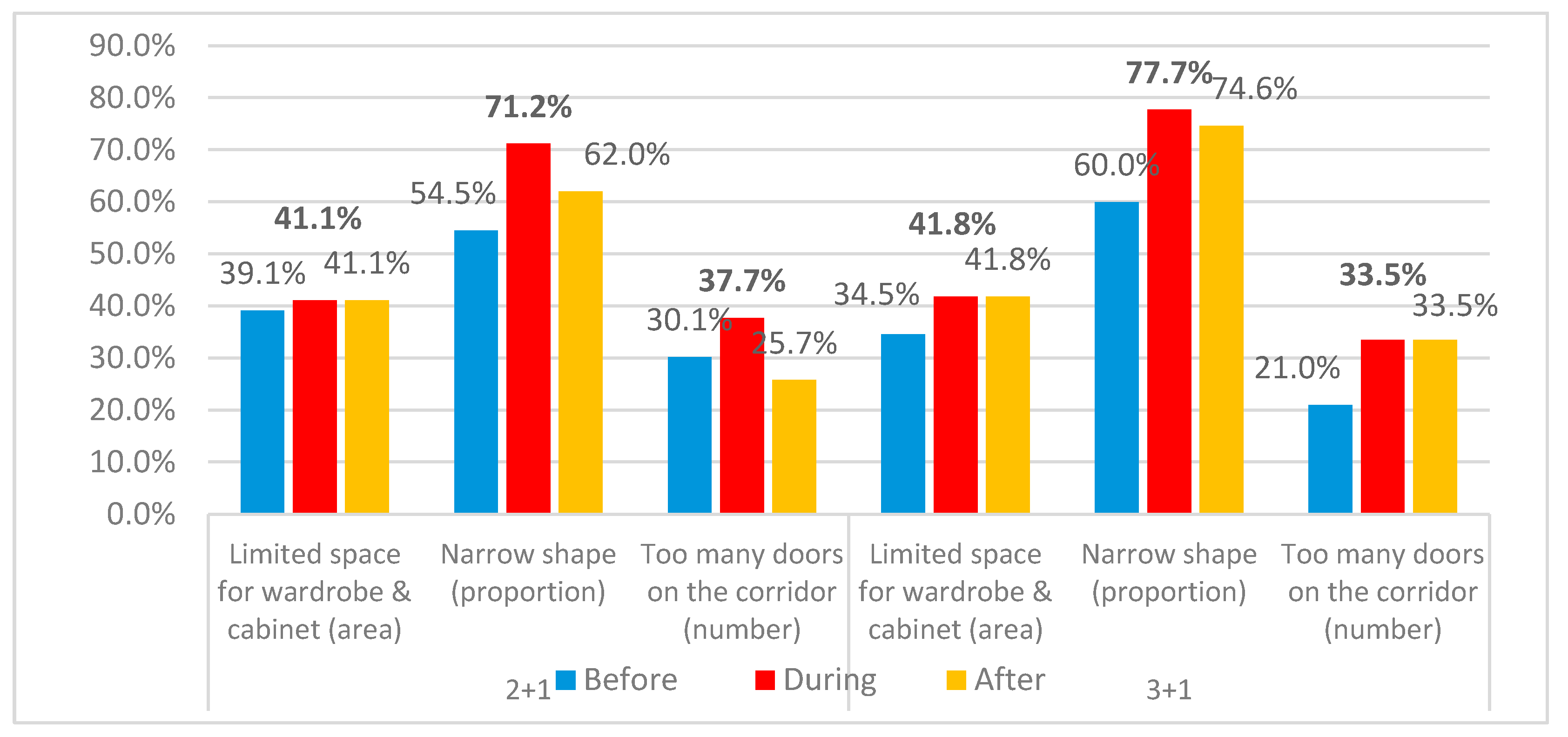

Figure 32.

Reasons for changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of family dining space in both categories.

Figure 32.

Reasons for changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of family dining space in both categories.

Figure 33.

Dissatisfaction of conditions of single or double family dining.

Figure 33.

Dissatisfaction of conditions of single or double family dining.

Figure 34.

Main reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of family dining space between family dining and guest dining.

Figure 34.

Main reasons for Changes in residents’ dissatisfaction of family dining space between family dining and guest dining.

Figure 35.

Dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms for 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 35.

Dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms for 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 36.

Dissatisfaction of only master bedrooms containing bathrooms for 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 36.

Dissatisfaction of only master bedrooms containing bathrooms for 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 37.

main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for only master bedrooms containing bathrooms for 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 37.

main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for only master bedrooms containing bathrooms for 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 38.

Dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms containing or missing bathrooms.

Figure 38.

Dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms containing or missing bathrooms.

Figure 39.

Dissatisfaction differences of master bedrooms with or without balcony.

Figure 39.

Dissatisfaction differences of master bedrooms with or without balcony.

Figure 40.

Apartment 2+1 category Dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms containing or missing bathrooms.

Figure 40.

Apartment 2+1 category Dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms containing or missing bathrooms.

Figure 41.

Apartment 3+1 category Dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms containing or missing bathrooms.

Figure 41.

Apartment 3+1 category Dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms containing or missing bathrooms.

Figure 42.

Dissatisfaction stability due to availability of more than one balcony in both categories.

Figure 42.

Dissatisfaction stability due to availability of more than one balcony in both categories.

Figure 43.

Dissatisfaction variations due to master bedroom proportion.

Figure 43.

Dissatisfaction variations due to master bedroom proportion.

Figure 44.

main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms for both proportions.

Figure 44.

main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for master bedrooms for both proportions.

Figure 45.

Dissatisfaction differences in master bedrooms due to spatial organization .

Figure 45.

Dissatisfaction differences in master bedrooms due to spatial organization .

Figure 46.

Variations in apartments with two categories and two different organizations .

Figure 46.

Variations in apartments with two categories and two different organizations .

Figure 47.

Dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms for all categories.

Figure 47.

Dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms for all categories.

Figure 48.

Dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 48.

Dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 49.

main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms for 2+1 category.

Figure 49.

main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms for 2+1 category.

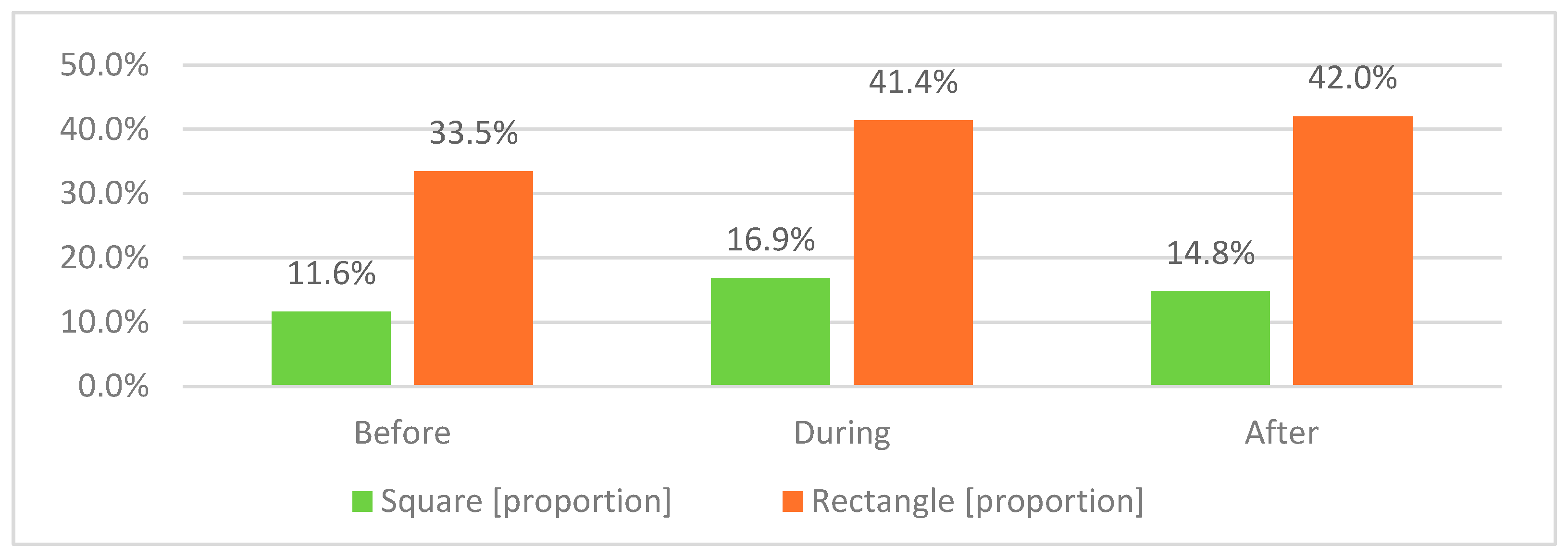

Figure 51.

Dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms due to space proportion variations.

Figure 51.

Dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms due to space proportion variations.

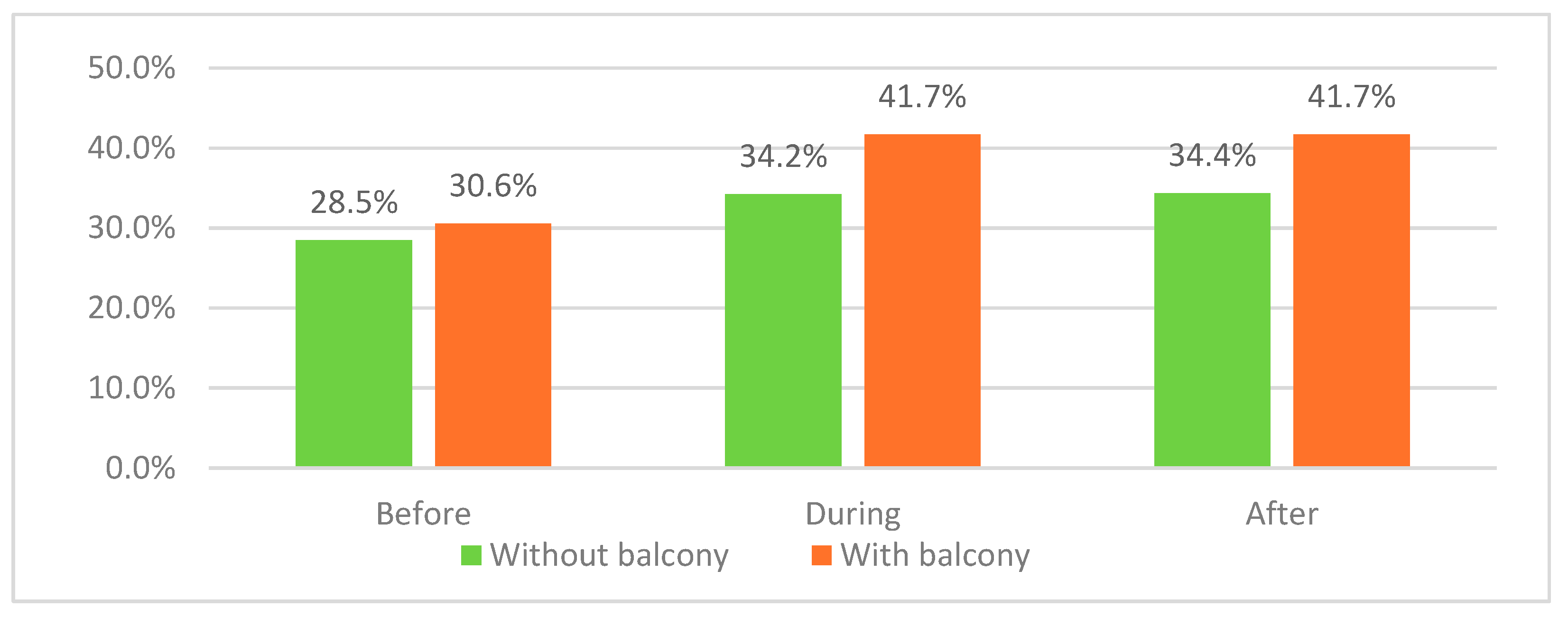

Figure 52.

Dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms due to balcony availability.

Figure 52.

Dissatisfaction differences for children’s bedrooms due to balcony availability.

Figure 53.

Dissatisfaction variations for children’s bedrooms due to spatial organization.

Figure 53.

Dissatisfaction variations for children’s bedrooms due to spatial organization.

Figure 54.

Dissatisfaction variations for children’s bedrooms due to spatial organization and apartment category.

Figure 54.

Dissatisfaction variations for children’s bedrooms due to spatial organization and apartment category.

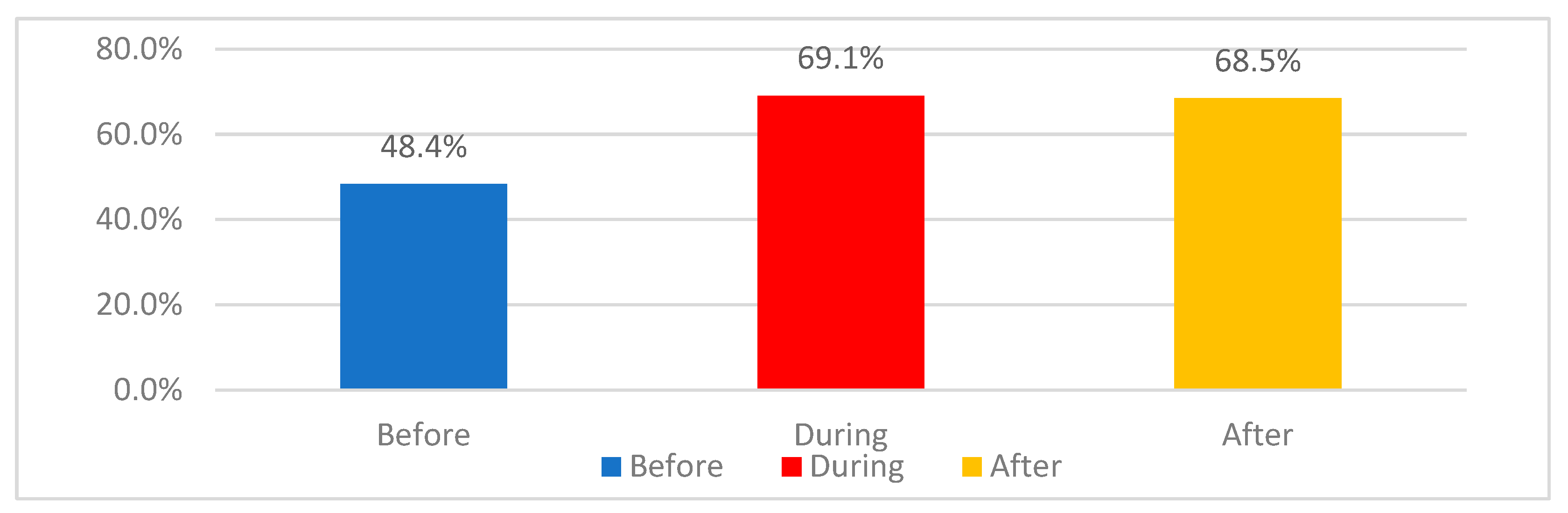

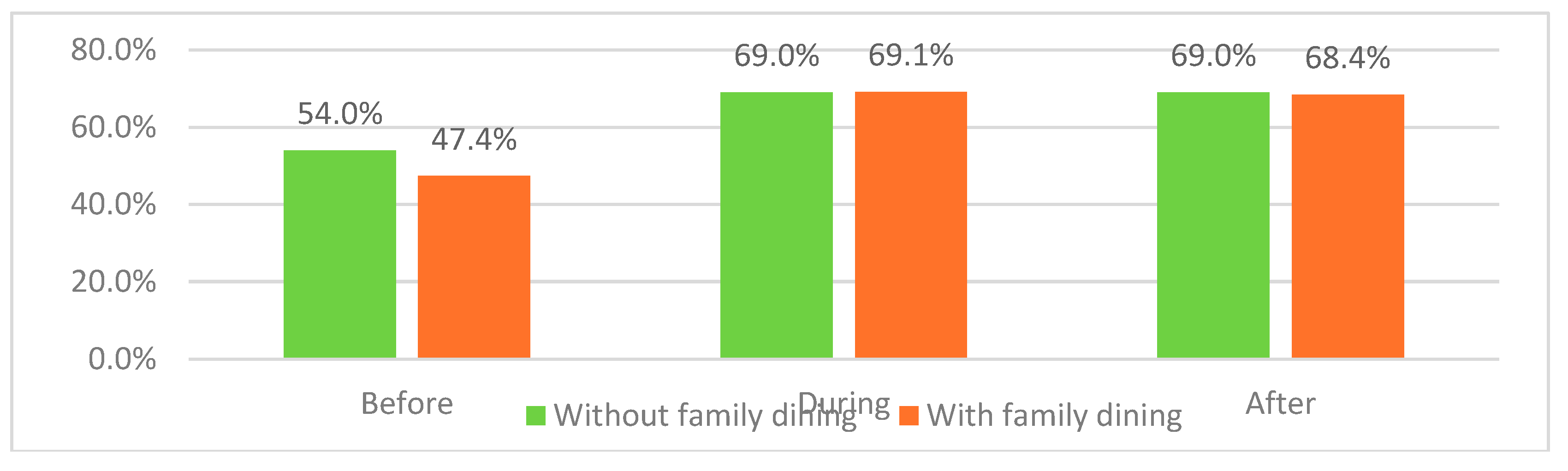

Figure 55.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchen through three stages of study.

Figure 55.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchen through three stages of study.

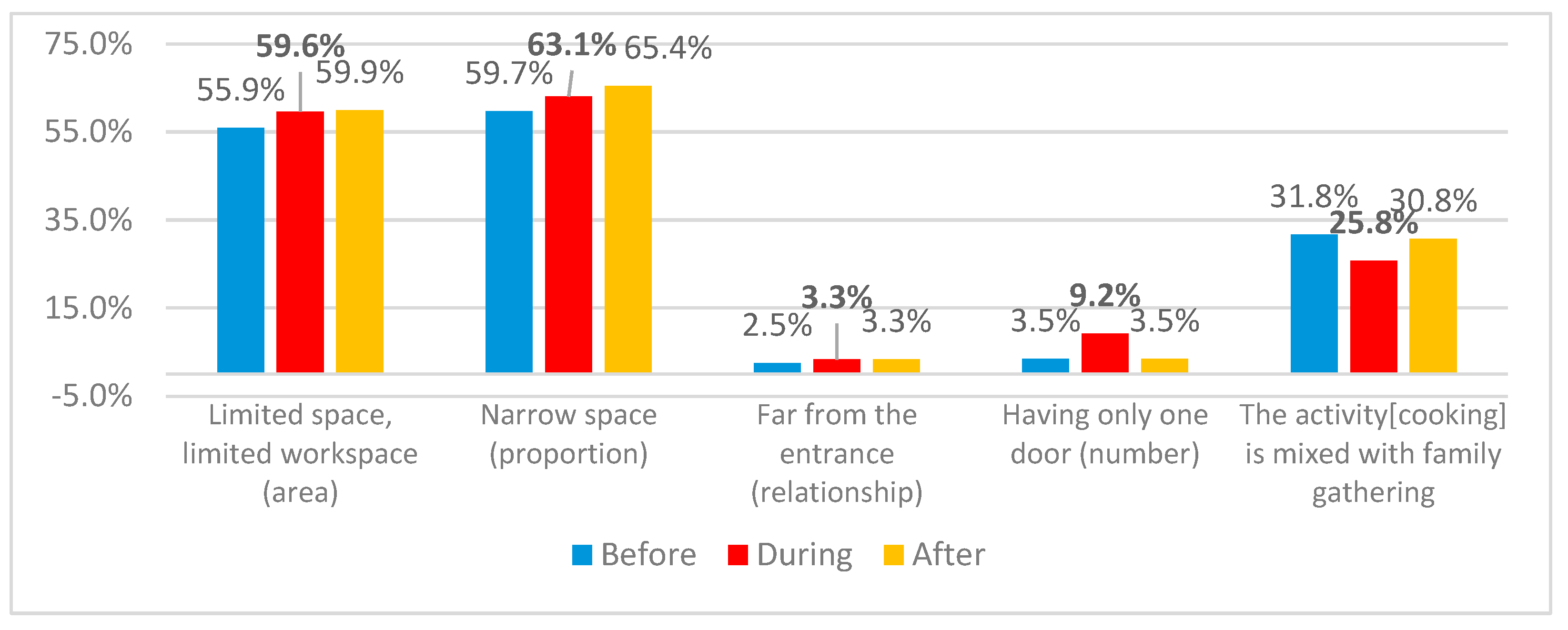

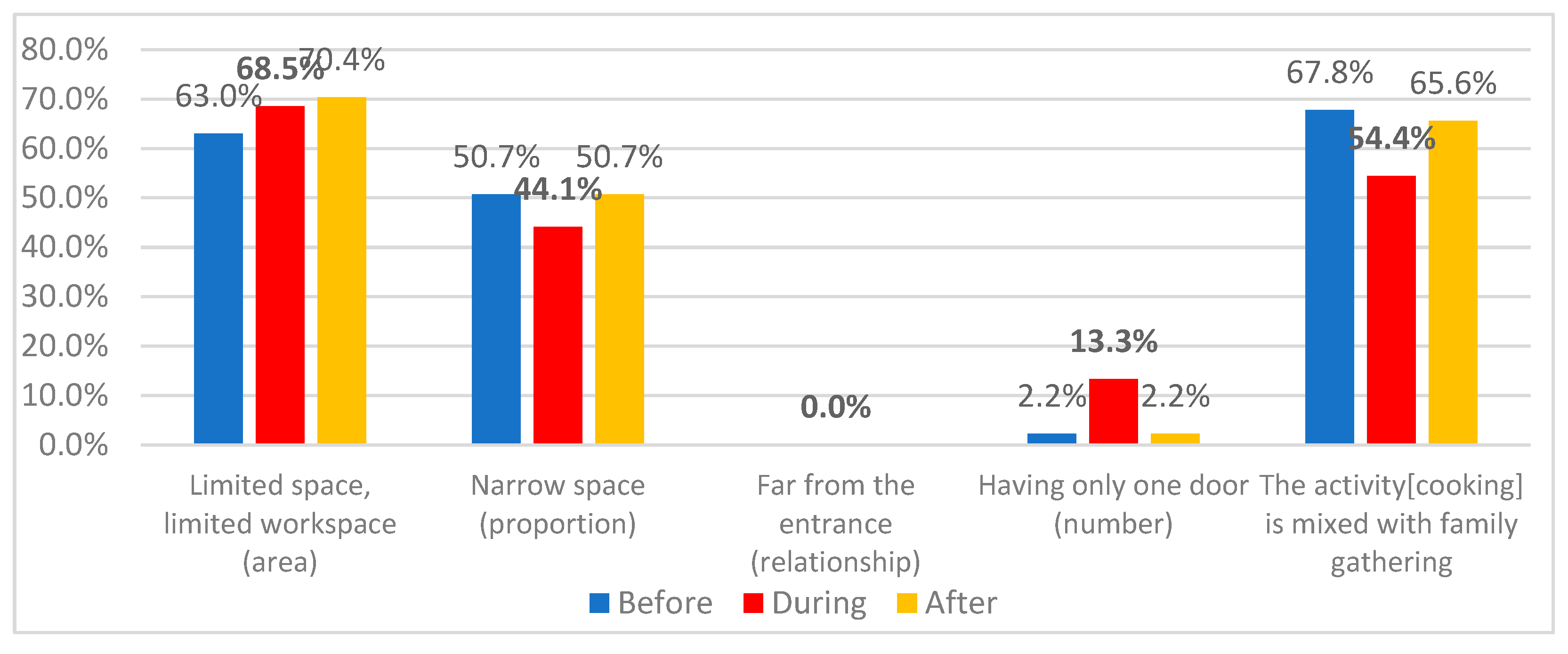

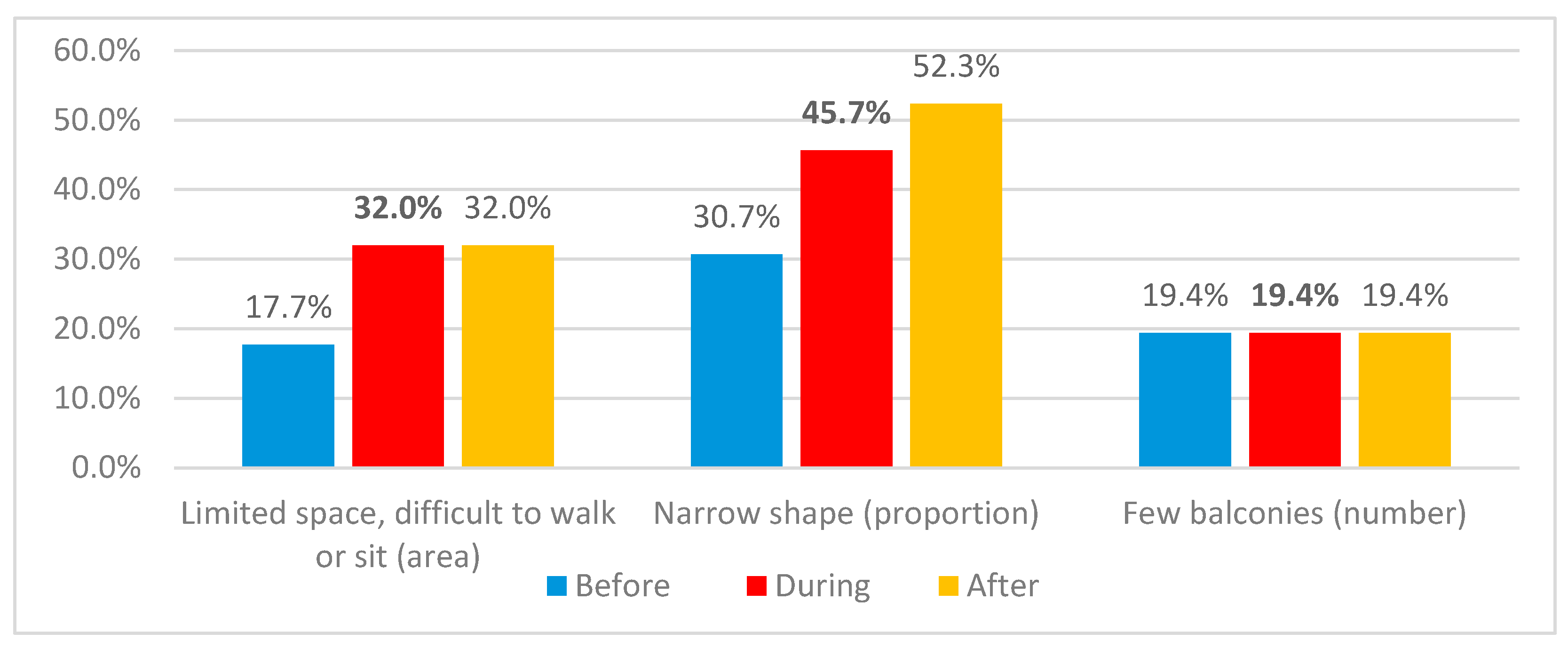

Figure 56.

main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchen in all apartments .

Figure 56.

main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchen in all apartments .

Figure 57.

Dissatisfaction differences for kitchens in 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 57.

Dissatisfaction differences for kitchens in 2+1 and 3+1 category.

Figure 58.

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchens for 2+1 category.

Figure 58.

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchens for 2+1 category.

Figure 59.

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchens for 3+1 category.

Figure 59.

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchens for 3+1 category.

Figure 60.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchens due to spatial organization.

Figure 60.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchens due to spatial organization.

Figure 61.

Reasons of Dissatisfaction for kitchens for closed spatial organization .

Figure 61.

Reasons of Dissatisfaction for kitchens for closed spatial organization .

Figure 62.

Reasons of Dissatisfaction for kitchens for opened spatial organization .

Figure 62.

Reasons of Dissatisfaction for kitchens for opened spatial organization .

Figure 63.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchens due to availability of family dining .

Figure 63.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchens due to availability of family dining .

Figure 64.

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchens without balcony.

Figure 64.

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchens without balcony.

Figure 65.

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchens with balcony.

Figure 65.

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for kitchens with balcony.

Figure 66.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchens due to availability and absence of balcony with closed spatial organization .

Figure 66.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchens due to availability and absence of balcony with closed spatial organization .

Figure 67.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchens due to availability and absence of balcony with closed spatial organization .

Figure 67.

Dissatisfaction variations for kitchens due to availability and absence of balcony with closed spatial organization .

Figure 68.

Dissatisfaction variations for family bathroom through stages of study.

Figure 68.

Dissatisfaction variations for family bathroom through stages of study.

Figure 69.

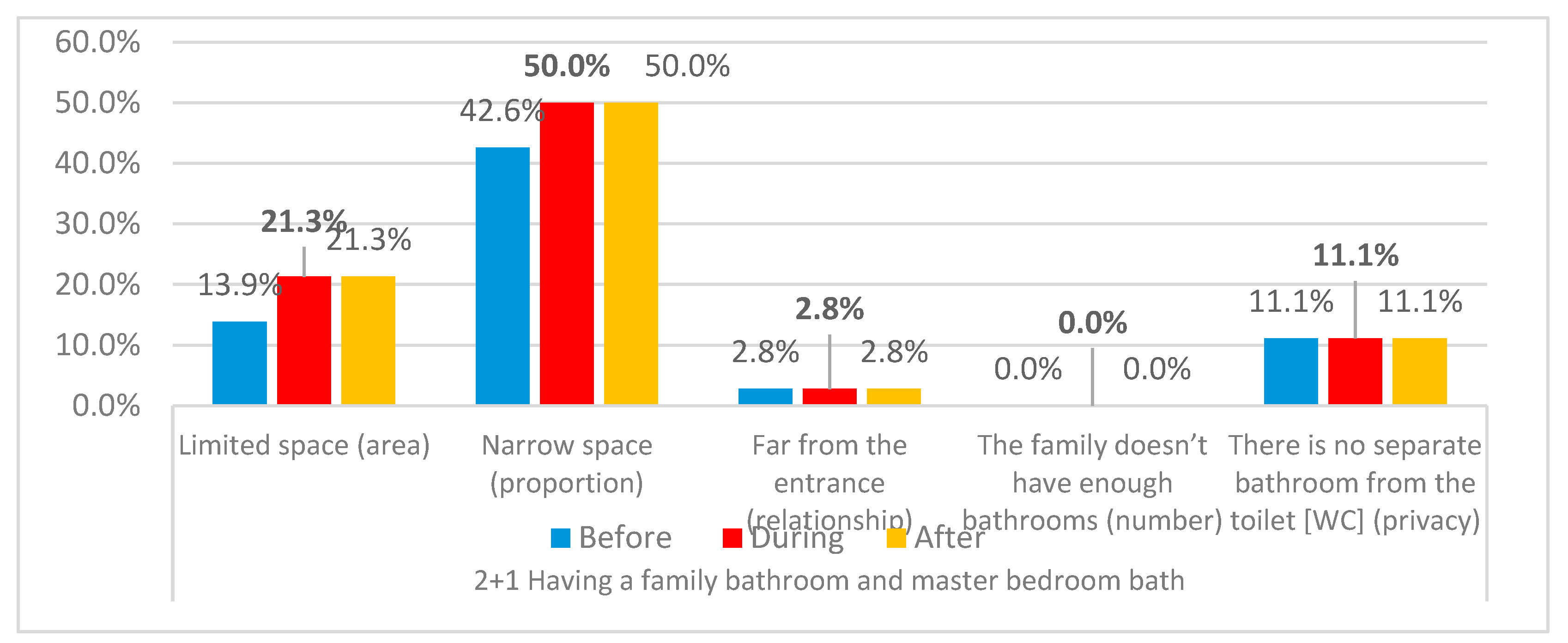

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for family bathrooms .

Figure 69.

Main reasons for dissatisfaction differences for family bathrooms .

Figure 70.

Variations in dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom in addition to basic family bathroom.

Figure 70.

Variations in dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom in addition to basic family bathroom.

Figure 71.

Reasons of dissatisfaction for cases only having basic family bathroom.

Figure 71.

Reasons of dissatisfaction for cases only having basic family bathroom.

Figure 72.

Reasons of dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom added to family bathroom.

Figure 72.

Reasons of dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom added to family bathroom.

Figure 73.

Variations in dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom in addition to basic family bathroom in between categories of 2+1 and 3+1.

Figure 73.

Variations in dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom in addition to basic family bathroom in between categories of 2+1 and 3+1.

Figure 74.

Reasons of changes in dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom in addition to basic family bathroom for category of 2+1.

Figure 74.

Reasons of changes in dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom in addition to basic family bathroom for category of 2+1.

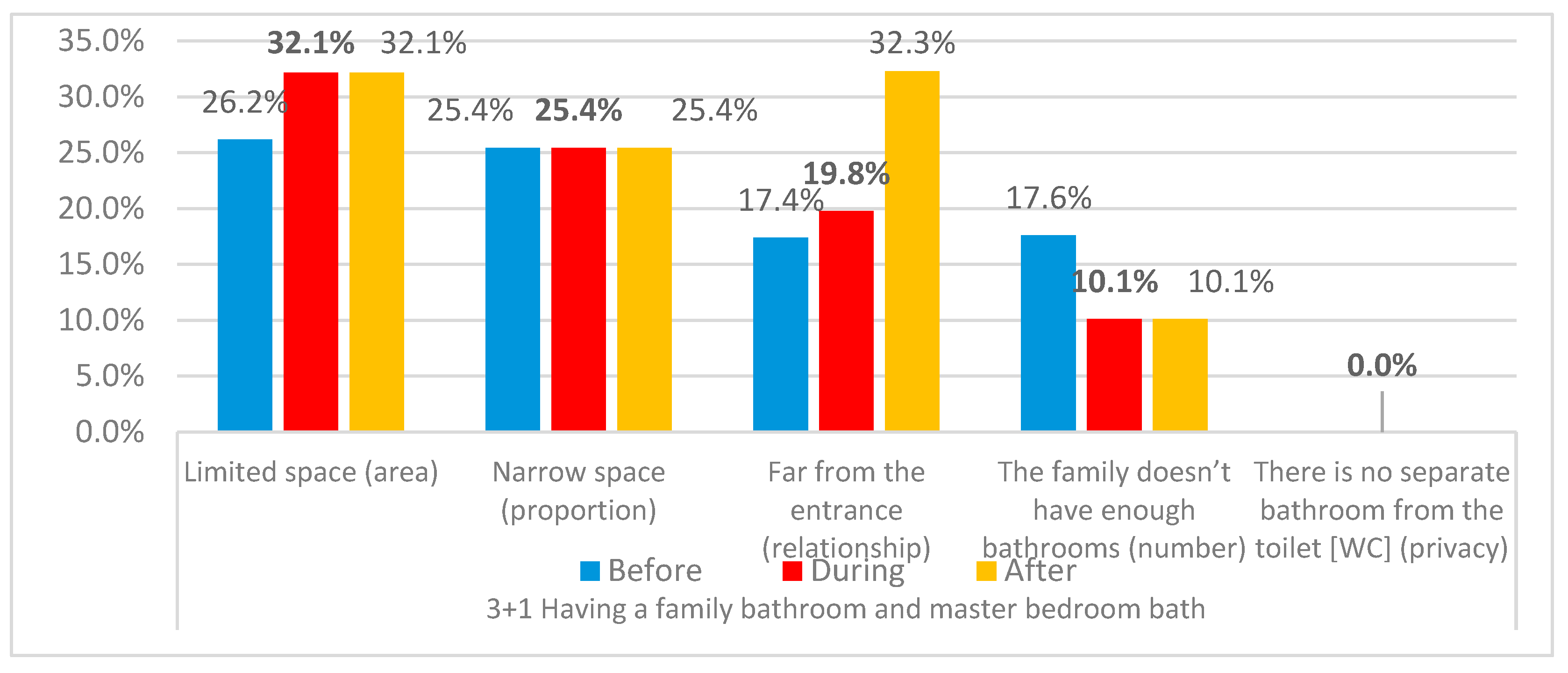

Figure 75.

Reasons of changes in dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom in addition to basic family bathroom for category of 3+1.

Figure 75.

Reasons of changes in dissatisfaction by the existence of master bathroom in addition to basic family bathroom for category of 3+1.

Figure 76.

Dissatisfaction variations for toilets through three stages of pandemic.

Figure 76.

Dissatisfaction variations for toilets through three stages of pandemic.

Figure 77.

Differences in dissatisfaction percentages for 2+1 and 3+1 categories.

Figure 77.

Differences in dissatisfaction percentages for 2+1 and 3+1 categories.

Figure 78.

Differences in dissatisfaction percentages for apartments without separate toilets and those who had separate units. .

Figure 78.

Differences in dissatisfaction percentages for apartments without separate toilets and those who had separate units. .

Figure 79.

Absence of separate toilet in formation of apartments indicating high dissatisfaction percentages of category 2+1 compared to 3+1 category. .

Figure 79.

Absence of separate toilet in formation of apartments indicating high dissatisfaction percentages of category 2+1 compared to 3+1 category. .

Figure 80.

Reasons for different dissatisfaction percentages for apartments with separate toilets.

Figure 80.

Reasons for different dissatisfaction percentages for apartments with separate toilets.

Figure 81.

Differences of dissatisfaction percentages in apartments with family toilet space and those with guest toilet spaces.

Figure 81.

Differences of dissatisfaction percentages in apartments with family toilet space and those with guest toilet spaces.

Figure 82.

Differences in percentages for reasons for dissatisfaction in apartments with family toilet space and those with guest toilet spaces.

Figure 82.

Differences in percentages for reasons for dissatisfaction in apartments with family toilet space and those with guest toilet spaces.

Figure 83.

Dissatisfaction variations for laundry through three stages of pandemic.

Figure 83.

Dissatisfaction variations for laundry through three stages of pandemic.

Figure 84.

Dissatisfaction variations due to availability or absence of laundry space.

Figure 84.

Dissatisfaction variations due to availability or absence of laundry space.

Figure 85.

Reasons for variations due to availability or absence of laundry space.

Figure 85.

Reasons for variations due to availability or absence of laundry space.

Figure 86.

Apartments without specific laundry space dissatisfaction percentages of both categories.

Figure 86.

Apartments without specific laundry space dissatisfaction percentages of both categories.

Figure 87.

Reasons for dissatisfactions variations of both categories with absence of specific laundry.

Figure 87.

Reasons for dissatisfactions variations of both categories with absence of specific laundry.

Figure 88.

Apartments containing specific laundry space’s dissatisfaction percentages of both categories 2+1 and 3+1.

Figure 88.

Apartments containing specific laundry space’s dissatisfaction percentages of both categories 2+1 and 3+1.

Figure 89.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding both apartments’ categories 2+1 and 3+1 with the availability of specific laundry space.

Figure 89.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding both apartments’ categories 2+1 and 3+1 with the availability of specific laundry space.

Figure 90.

Dissatisfaction variations for storage through three stages of pandemic.

Figure 90.

Dissatisfaction variations for storage through three stages of pandemic.

Figure 91.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding storage activity .

Figure 91.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding storage activity .

Figure 92.

Dissatisfaction variations due to availability or absence of storage space.

Figure 92.

Dissatisfaction variations due to availability or absence of storage space.

Figure 93.

Dissatisfaction percentages of both categories 2+1 and 3+1 of apartments without specific storage space.

Figure 93.

Dissatisfaction percentages of both categories 2+1 and 3+1 of apartments without specific storage space.

Figure 94.

Dissatisfaction percentages of both categories of apartments having specific storage space.

Figure 94.

Dissatisfaction percentages of both categories of apartments having specific storage space.

Figure 95.

Reasons for dissatisfactions variations regarding both apartments’ categories 2+1 and 3+1 with the absence of specific storage space.

Figure 95.

Reasons for dissatisfactions variations regarding both apartments’ categories 2+1 and 3+1 with the absence of specific storage space.

Figure 96.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding both apartments’ categories 2+1 and 3+1 with the availability of specific storage space.

Figure 96.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding both apartments’ categories 2+1 and 3+1 with the availability of specific storage space.

Figure 97.

Dissatisfaction variations for balconies through three stages of pandemic.

Figure 97.

Dissatisfaction variations for balconies through three stages of pandemic.

Figure 98.

Dissatisfaction percentages of both types of apartments for availability or absence of balconies through three stages of study concern.

Figure 98.

Dissatisfaction percentages of both types of apartments for availability or absence of balconies through three stages of study concern.

Figure 99.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations for all apartments with the availability of balconies.

Figure 99.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations for all apartments with the availability of balconies.

Figure 100.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding both apartments’ categories 2+1 and 3+1 with the availability of balconies.

Figure 100.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding both apartments’ categories 2+1 and 3+1 with the availability of balconies.

Figure 101.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding all apartments with the availability of balconies of category 2+1.

Figure 101.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding all apartments with the availability of balconies of category 2+1.

Figure 102.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding all apartments with the availability of balconies of category 3+1.

Figure 102.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding all apartments with the availability of balconies of category 3+1.

Figure 103.

Dissatisfaction variations regarding all apartments with different numbers of balconies zero cases were excluded .

Figure 103.

Dissatisfaction variations regarding all apartments with different numbers of balconies zero cases were excluded .

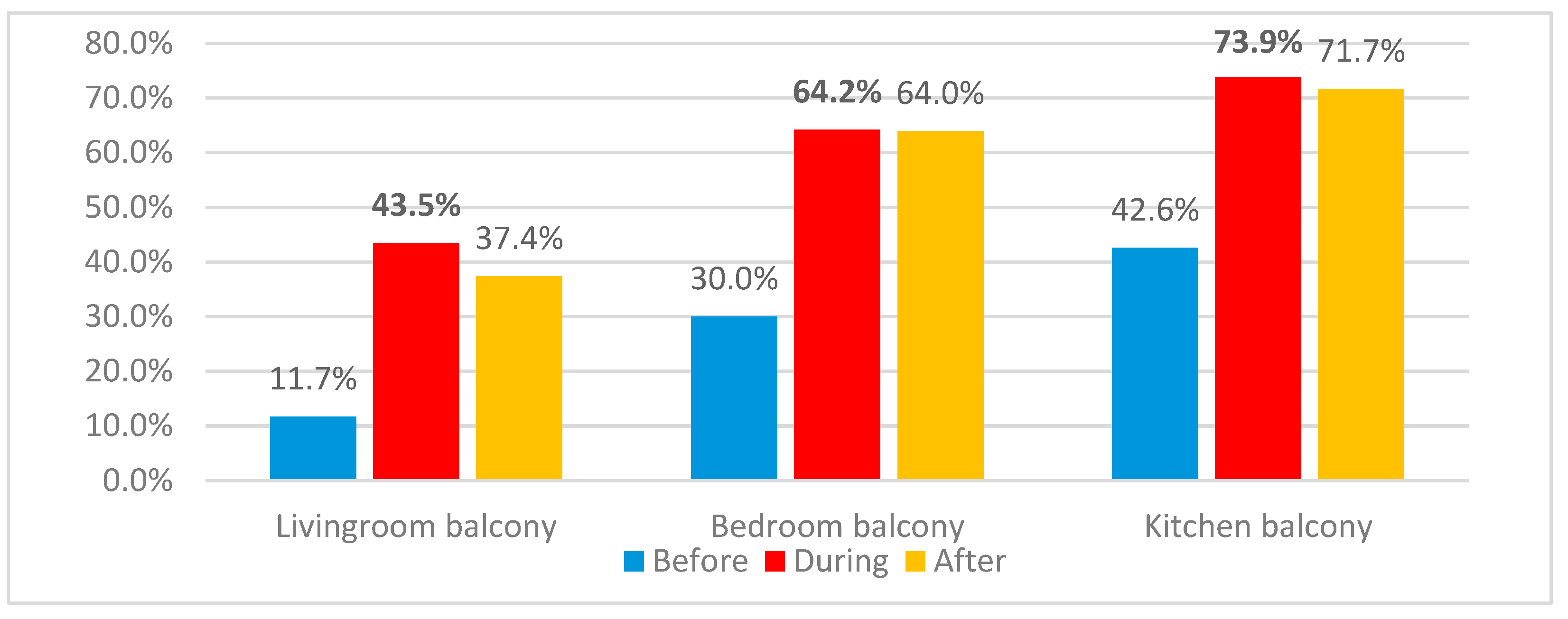

Figure 104.

Dissatisfaction variations regarding different balconies types related to internal spaces.

Figure 104.

Dissatisfaction variations regarding different balconies types related to internal spaces.

Figure 105.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding living room balconies.

Figure 105.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding living room balconies.

Figure 106.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding bedroom room balconies.

Figure 106.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations regarding bedroom room balconies.

Figure 109.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations for apartments’ corridors through the three stages of pandemic.

Figure 109.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations for apartments’ corridors through the three stages of pandemic.

Figure 110.

Dissatisfaction variations for corridors between categories 2+1 and 3+1 .

Figure 110.

Dissatisfaction variations for corridors between categories 2+1 and 3+1 .

Figure 111.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations for apartments’ corridors through the three stages of pandemic for categories 2+1 and 3+1.

Figure 111.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations for apartments’ corridors through the three stages of pandemic for categories 2+1 and 3+1.

Figure 112.

Dissatisfaction variations for corridors between closed and opened spatial organizations.

Figure 112.

Dissatisfaction variations for corridors between closed and opened spatial organizations.

Figure 113.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations about apartments’ corridors through the three stages of pandemic for closed and opened spatial organizations .

Figure 113.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations about apartments’ corridors through the three stages of pandemic for closed and opened spatial organizations .

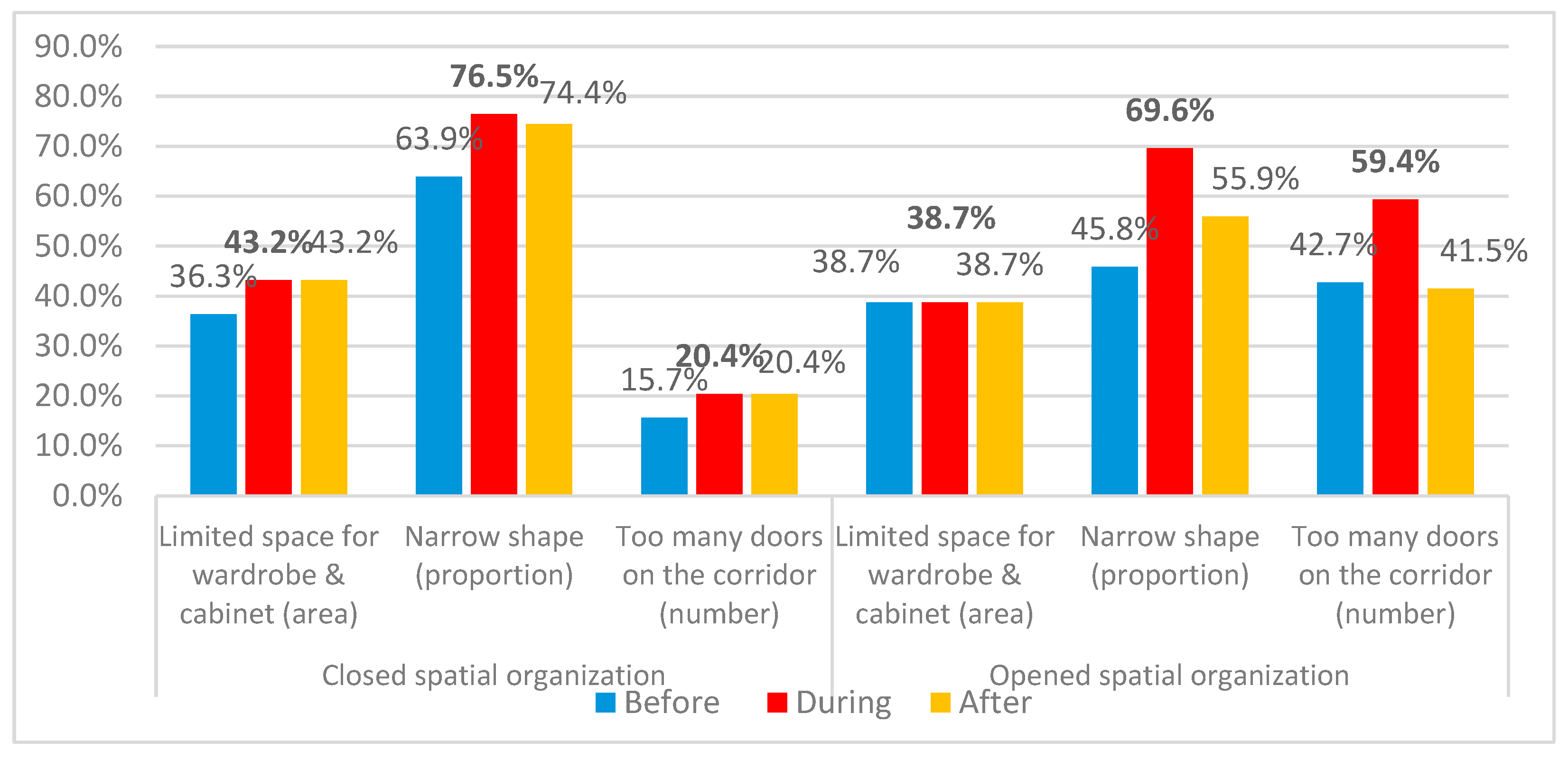

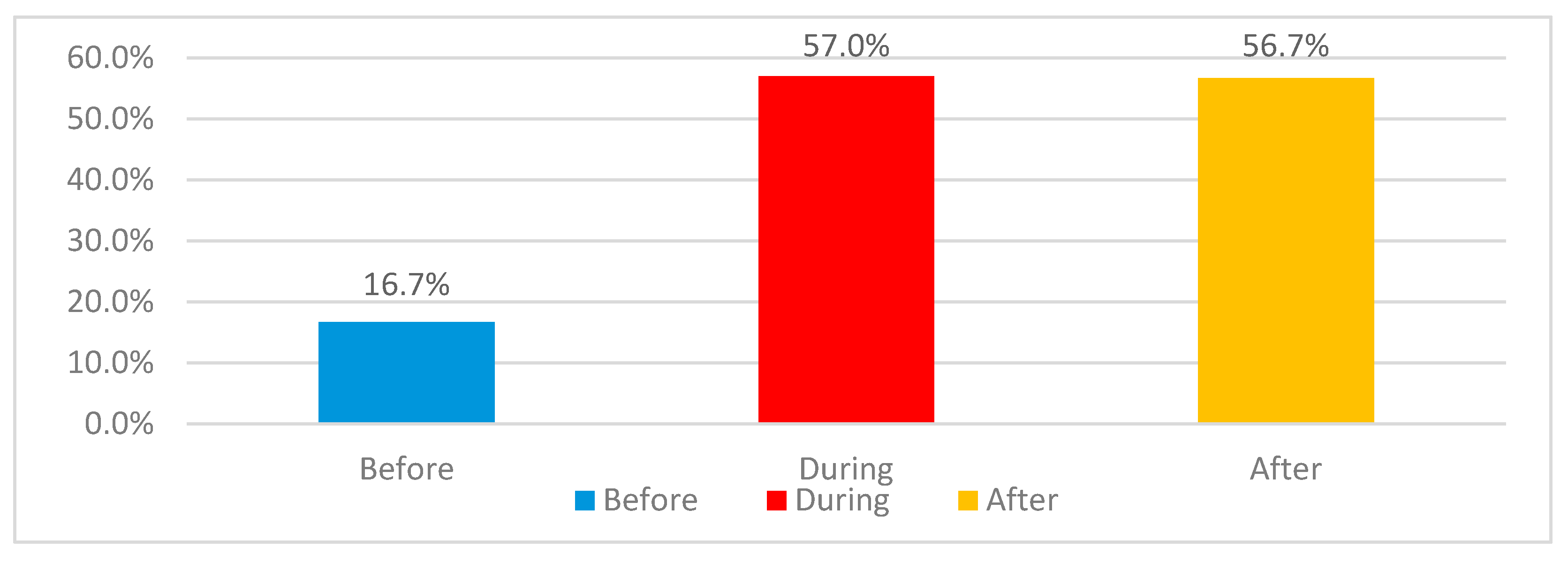

Figure 114.

Dissatisfaction variations for apartments’ layout due to pandemic.

Figure 114.

Dissatisfaction variations for apartments’ layout due to pandemic.

Figure 115.

Dissatisfaction variations for apartments’ layouts s through the three stages of pandemic for categories 2+1 and 3+1 and subcategories 2+2 and 3+2.

Figure 115.

Dissatisfaction variations for apartments’ layouts s through the three stages of pandemic for categories 2+1 and 3+1 and subcategories 2+2 and 3+2.

Figure 116.

Dissatisfaction variations for corridors between closed and opened spatial organizations.

Figure 116.

Dissatisfaction variations for corridors between closed and opened spatial organizations.

Figure 117.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations about apartments’ layout of closed organization.

Figure 117.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations about apartments’ layout of closed organization.

Figure 118.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations about apartments’ layout of opened spatial organization .

Figure 118.

Reasons for dissatisfaction variations about apartments’ layout of opened spatial organization .

Table 1.

Main criteria used for selection of investment projects for current study.

Table 1.

Main criteria used for selection of investment projects for current study.

| No |

Projects |

Residents’ main requirements |

Apartments requirements |

Acceptance for participation |

| |

Criteria |

Occupied |

Family |

Ownership |

Stages |

Size |

Higher |

Investor authorization |

Family authorization |

| 1 |

Zanyary |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| 2 |

Eskan Tower |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| 3 |

Quatro |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| 4 |

Park View |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| 5 |

Empire |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| 6 |

MRF5 |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| 7 |

Roya |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| 8 |

Cihan |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| 9 |

FM Plaza |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| 10 |

Plus Life |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

Table 2A.

Respondents Demographic characteristics part A.

Table 2A.

Respondents Demographic characteristics part A.

| Table -2 Respondents’ Demographic Characteristics -part A |

| Criteria |

Category |

Frequency |

% |

| Gender |

Male |

72 |

50.7% |

| Female |

70 |

49.3% |

| Total |

142 |

100% |

| Age of Head |

20-29 |

29 |

20.4% |

| 30-39 |

70 |

49.3% |

| 40-49 |

24 |

16.9% |

| 50-59 |

11 |

7.7% |

| 60-69 |

8 |

5.6% |

| >69 |

0 |

0.0% |

| Total |

142 |

100% |

Table 2B.

Respondents Demographic characteristics part B.

Table 2B.

Respondents Demographic characteristics part B.

| Table -2 Respondents’ Demographic Characteristics -part B |

| Criteria |

Category |

Frequency |

% |

| Education of Head |

H.S. |

11 |

7.7% |

| B.Sc. |

105 |

73.9% |

| M.Sc. |

19 |

13.4% |

| Ph.D. |

7 |

4.9% |

| Others |

0 |

0.0% |

| Total |

142 |

100% |

| Job of Head |

Engineer |

31 |

21.8% |

| Doctor |

27 |

19.0% |

| Architect |

12 |

8.5% |

| Employee |

45 |

31.7% |

| Housekeeper |

6 |

4.2% |

| Retired |

2 |

1.4% |

| Private sector |

19 |

13.4% |

| Total |

142 |

100% |

Table 3.

Respondents families’ Demographic characteristics.

Table 3.

Respondents families’ Demographic characteristics.

| Table -3 Respondents ‘Family Demographic Characteristics |

| Criteria |

Category |

Frequency |

% |

| No. of residents |

One person |

4 |

2.8% |

| Two persons |

20 |

14.1% |

| Three persons |

48 |

33.8% |

| Four persons |

45 |

31.7% |

| Five persons |

15 |

10.6% |

| Six persons |

6 |

4.2% |

| Seven persons |

4 |

2.8% |

| Total |

142 |

100% |

| Marital Status |

Single |

8 |

5.6% |

| Married |

21 |

14.8% |

| Married with children |

108 |

76.1% |

| Married with parents |

5 |

3.5% |

| Total |

142 |

100% |

Table 17.

average dissatisfaction percentages for all apartments’ spaces and items considered in current research.

Table 17.

average dissatisfaction percentages for all apartments’ spaces and items considered in current research.

| No. |

Dissatisfaction

Stages

|

Trend |

B< [D ≤A] |

[B < A] & [D > A] |

[B > D,A] & [D < A] |

[B=A] Or [ B<A] |

| |

Change |

Definition |

Firm change |

Real change |

Slight change |

Stable or Negative |

| |

Change Typology |

|

Type 1 |

Type 2 |

Type 3 |

Type 4 |

| 1 |

En.Q1.Beforepandemic |

34.0% |

|

|

|

|

| En.Q1.Duringpandemic |

65.2% |

|

|

|

| En.Q1.Afterpandemic |

57.9% |

|

|

|

| 2 |

Re.Q1.Beforepandemic |

52.7% |

|

|

|

|

| Re.Q1.Duringpandemic |

32.7% |

|

|

|

| Re.Q1.Afterpandemic |

37.3% |

|

|

|

| 3 |

Li.Q1.Beforepandemic |

21.1% |

|

|

|

|

| Li.Q1.Duringpandemic |

45.5% |

|

|

|

| Li.Q1.Afterpandemic |

47.5% |

|

|

|

| 4 |

Fd.Q1.Beforepandemic |

33.6% |

|

|

|

|

| Fd.Q1.Duringpandemic |

50.3% |

|

|

|

| Fd.Q1.Afterpandemic |

59.4% |

|

|

|

| 5 |

Ma.Q1.Beforepandemic |

9.5% |

|

|

|

|

| Ma.Q1.Duringpandemic |

25.7% |

|

|

|

| Ma.Q1.Afterpandemic |

24.8% |

|

|

|

| 6 |

Ch.Q1.Beforepandemic |

29.1% |

|

|

|

|

| Ch.Q1.Duringpandemic |

36.5% |

|

|

|

| Ch.Q1.Afterpandemic |

36.6% |

|

|

|

| 7 |

Ki.Q1.Beforepandemic |

48.4% |

|

|

|

|

| Ki.Q1.Duringpandemic |

69.1% |

|

|

|

| Ki.Q1.Afterpandemic |

68.5% |

|

|

|

| 8 |

Ba.Q1.Beforepandemic |

31.8% |

|

|

|

|

| Ba.Q1.Duringpandemic |

40.3% |

|

|

|

| Ba.Q1.Afterpandemic |

39.9% |

|

|

|

| 9 |

To.Q1.Beforepandemic |

54.7% |

|

|

|

|

| To.Q1.Duringpandemic |

68.0% |

|

|

|

| To.Q1.Afterpandemic |

66.8% |

|

|

|

| 10 |

La.Q1.Beforepandemic |

67.1% |

|

|

|

|

| La.Q1.Duringpandemic |

77.8% |

|

|

|

| La.Q1.Afterpandemic |

77.8% |

|

|

|

| 11 |

St.Q1.Beforepandemic |

78.2% |

|

|

|

|

| St.Q1.Duringpandemic |

92.8% |

|

|

|

| St.Q1.Afterpandemic |

92.8% |

|

|

|

| 12 |

Ap.Co.Q1.Beforepandemic |

27.8% |

|

|

|

|

| Ap.Co.Q1.Duringpandemic |

58.2% |

|

|

|

| Ap.Co.Q1.Afterpandemic |

51.9% |

|

|

|

| 13 |

Bal.Q1.Beforepandemic |

31.8% |

|

|

|

|

| Bal.Q1.Duringpandemic |

64.7% |

|

|

|

| Bal.Q1.Afterpandemic |

61.2% |

|

|

|

| 14 |

Ap.La.Q1.Beforepandemic |

16.7% |

|

|

|

|

| Ap.La.Q1.Duringpandemic |

57.0% |

|

|

|

| Ap.La.Q1.Afterpandemic |

56.7% |

|

|

|