1. Introduction

Perianal fistulas (PFs) are painful ulcers that occur spontaneously on the skin surrounding the anus of dogs of any breed. They are an immune-mediated condition in which the current standard treatment is pharmacological. Cyclosporine is the recommended treatment of choice, but it may be associated with numerous adverse [

1] and surgical effects. This condition can be debilitating for affected dogs and can lead to euthanasia if not treated effectively [

2].

Since PFs are immune mediated, they have several characteristics in common with the fistulae in human Crohn’s disease (CD) [

3]. Considering the recent advances in the medical and surgical treatment of CD, remission rates remain low, and despite the development of new biological therapies, the average efficacy at one year is 30–50% [

4]. The factors involved in the pathogenesis of CD fistulizing disease include an increase in the production of transforming growth factor β and interleukin-13 in the inflammatory infiltrate that induce epithelial to mesenchymal transition and an increase in matrix metalloproteinases, leading to tissue remodeling and fistula formation [

5,

6].

However, it has been shown that adult mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) mediate immune suppression through various mechanisms, such as immune modulation and suppression of inflammation [

7]. Many studies have evaluated the efficacy of these stem cells in immune-mediated diseases in humans and animals [

8].

The efficacy and safety of expanded allogeneic MSC therapy for CD in humans has been demonstrated in phase III clinical trials[

9], and a patent has been obtained in Europe[

10], suggesting that the treatment of spontaneous canine PF with pluripotent stem cells could be used as a model to evaluate cell therapy [

3]. However, after revision of the PubMed database, only one open trial carried out using embryonic MSC in canines with good results was found [

10,

11]. Nevertheless, the data available support the hypothesis that the results from testing cell therapies in dogs with anal furunculosis have a significant translational value in optimizing MSC transplant procedures in patients with perianal CD (pCD) [

11].

Given the few publications on the use of allogeneic adipose stem cells for the treatment of PF in canines, and the lack of consensus protocols, the aim of this pilot clinical trial was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a new protocol proposed by our working group related to the administration of expanded and cryopreserved allogeneic adipose stem cells in spontaneous PFs in dogs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

This trial was conducted from January 2019 to December 2023 at the Enciso Veterinary Clinic, which was performed according to the Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines, was approved by the Ethics Commission of the San Luis Gonzaga National University of Ica, Peru (Resolution No. 3, Ethics Commission) and informed consent was obtained from the owner for the treatment.

The evaluation was carried out with fourteen dogs of different breeds between 4 and 16 years of age; 64% (9/14) were males, and all had a clinical diagnosis of perianal fistula (PF); six had simple fistulas and eight had complex fistulas based on Sandborn’s description [

12] (

Table 1). All were previously treated with conventional drug therapy using cyclosporin A (2–10 mg/kg) for periods of 12 months, with all the cases presenting early relapse. Exclusion criteria were the presence of significant clinical conditions/diseases and previous surgery for treatment of perianal fistula.

The patients underwent a rigorous clinical examination to rule out the presence of abscesses and tumours. If tumours were diagnosed, the patients were excluded. If an abscess was detected, antibiotic therapy with a combination of ciprofloxacin (10 mg/kg/12 h) and metronidazole (25 mg/kg/12 h) was administered, and after remission of the abscess, the patient was included in the trial.

2.2. Adipose Stem Cells

Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs) were obtained from healthy donor bitches undergoing elective sterilisation and processed at the Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) facility of the Universidad Científica del Sur. The cells were preserved in liquid nitrogen for 12 months in the cryobank of the Stem Cell Laboratory of the Enciso Veterinary Clinic in Lima (Peru). Isolation, cultured and cryopreserved of ASCs was performed as described by Enciso et al. [

13]. Briefly, ASCs were cultured in DMEM that contained 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic. After the fifth passage, aliquots were taken for cell counting, viability assay, microbiological tests, characterisation and differentiation of the ASCs into the three lineages (osteogenic, chondrogenic and adipogenic tissue) and finally frozen at -80 °C. On the day of cell administration to the patient, the cells were thawed according to a previously described routine procedure [

14] with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4, used as a diluent for administration. ASCs used for injection were cultured in the Luria-Bertani medium (Scharlab S.L. Barcelona, Spain) to evaluate sterility. Before using the ASCs therapeutically, cells were analysed by flow cytometry to confirm that they were positive for CD90 and negative for CD34, CD45, and MCH-II and expression of GAPDH, TBP, OCT4, RUNX2, SOX9 and PPARG genes was detected by RT-PCR as previously reported [

15].

Quality control, which included polymerase chain reaction tests for canine distemper virus, Mycoplasma, Ehrlichia canis and Anaplasma sp. with negative results as described by Enciso et al. in 2019 [

13]. These tests were performed prior to freezing and before use as a treatment. Cell viability was evaluated using trypan blue (with a viability greater than 95%), and the solution was distributed into 1 mL syringes with 25G x 5/8” needles at a concentration of 1x106 cells per syringe. The syringes were kept at 4-8 °C until cell administration.

2.3. Allogeneic ASC Administration Procedure

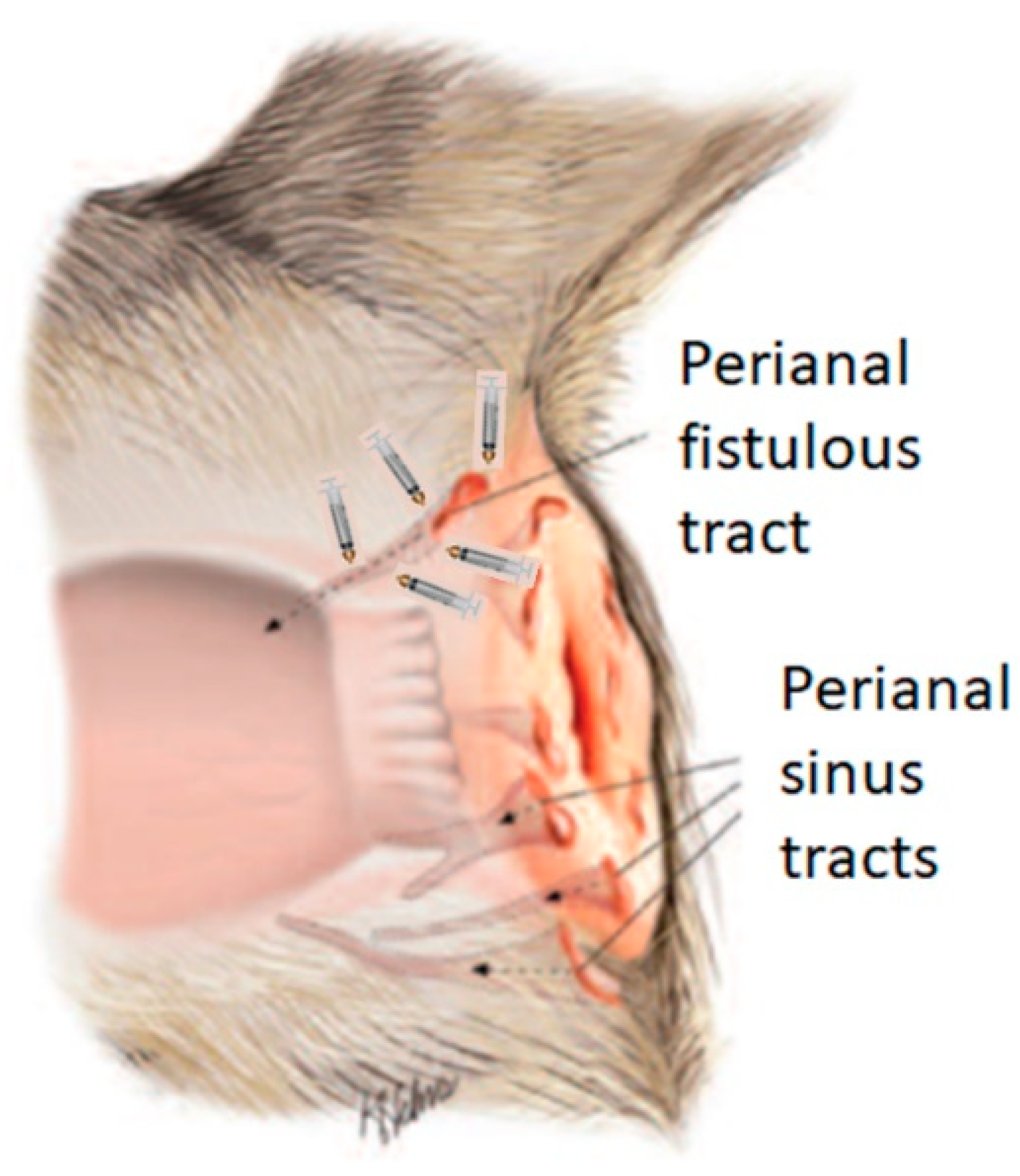

Prior to the ASC administration procedure, general anaesthesia of the patient was induced by intravenous neuroleptoanalgesia using a combination of xylazine/ketamine (1 mg/kg/10 mg/kg, Ket-A-Xyl®, Agrovet Market, Animal Health, Peru). Subsequently, the syringes with the cells were removed from refrigeration and kept at room temperature in the operating room of the veterinary clinic, until administration in doses of 1x106 diluted in PBS, at each point of each fistula as indicated in

Figure 1, using a 1 ml syringe with a No. 25G x 5/8¨ needle. Since the origin of a fistula is the internal orifice, it was considered that efficacy would be greater if the cells were injected into the tissue surrounding the fistula orifice and along the walls of the fistulous tracts, care was taken not to deposit the cells in the lumen of the orifice, similar to previous work in humans [

16]. In no case was the fistula sutured and neither topical nor systemic antibiotics were applied. A second and third dose was applied in two patients (table 1. Patient number 4 and 10) when there was evidence of recurrence of the clinical picture expressed by pruritus in the perianal area, but no fistula was present. A dose of 5x106 cells was applied to the erythematous area.

2.4. Clinical Evaluation of the Effect of ASCs

The efficacy endpoint was established 3 months after injection and follow-up was performed in some cases up to week 48. Efficacy was defined as complete closure of the fistulous tract and internal and external openings without drainage or signs of inflammation. The presence or absence of recognised local and systemic adverse clinical events such as fever, urticaria, pruritus and possible tumour development in the vicinity of the fistulae was assessed.

On days 0 (ASC injection), 7, 30, 60 and 90, patients were clinically examined to determine the presence/absence and depth of fistulae. In addition, to determine the safety of the treatment, a haemogram and blood biochemistry were performed to assess liver and renal function. In addition, clinical evaluation of patients who started the trial continued.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The results were analysed using SPSS 25 (IBM Corporation, Endicott, NY, USA) and Graph Pad Prism version 6 (Software, Inc., San Diego, California. United States). Data distribution was analysed using the Shapiro‒Wilk test. Comparison between the number of fistulas pre-treatment and at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after treatment with allogeneic ASC was evaluated with ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. All data are expressed as the mean and standard deviation. A difference was considered significant when the p value was <0.05.

3. Results

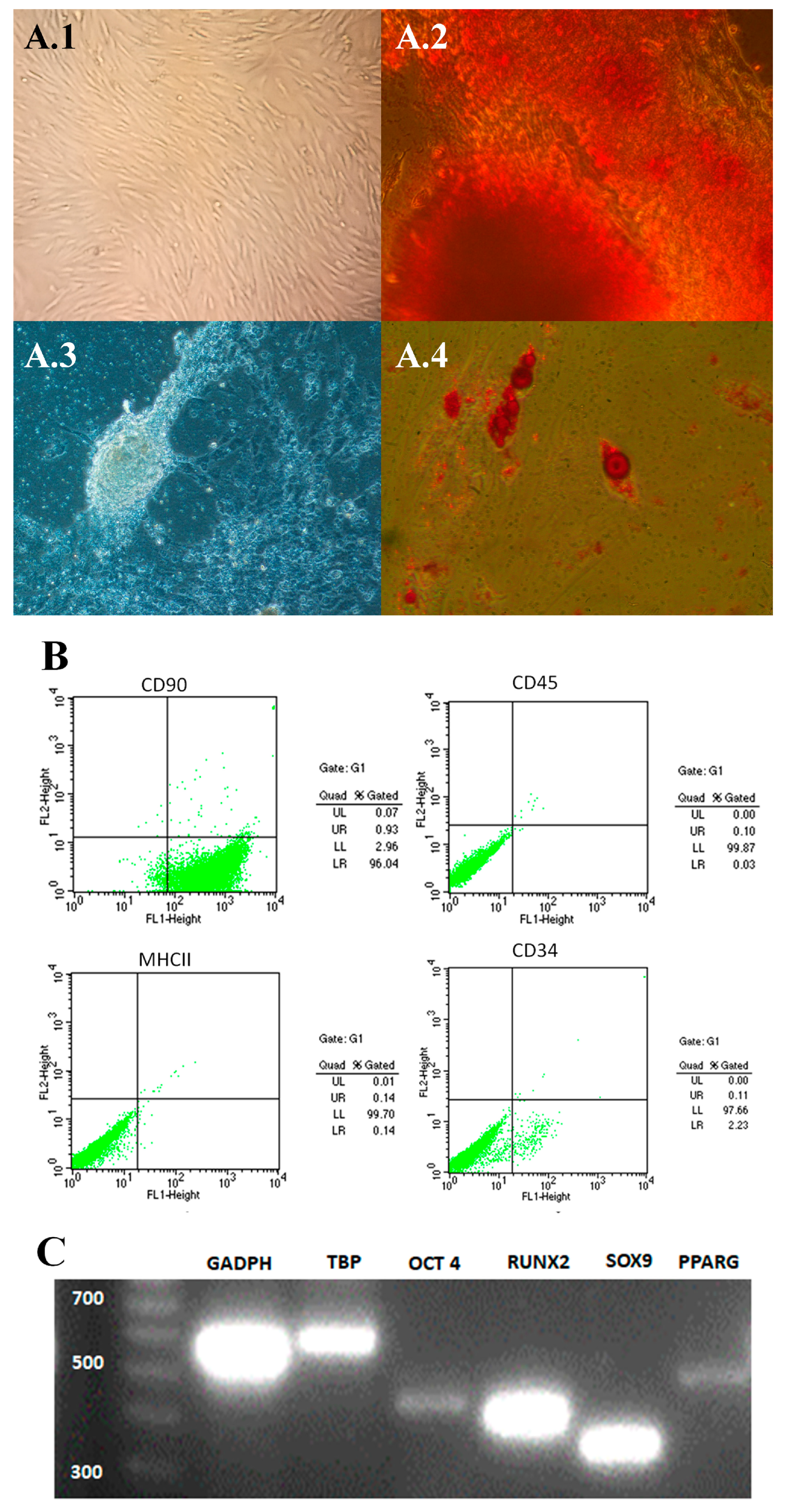

The thawed ASCs used for this trial had the minimum characteristics to be considered mesenchymal stem cells, according to the International Society for Tissue Cell Therapy (ISCT) [

17]. The cells presented a fibroblastoid morphology and adhered to plastic (

Figure 2A1) and differentiated into osteocytes, chondrocytes and adipocytes (

Figure 2A2–A4 respectively). In addition, the cells phenotyped CD90 positive while less than 2% were CD34, CD45 and MHCII positive (

Figure 2B) and showed expression of stem cell markers OCT4, RUNX2, SOX9 and PPARG (

Figure 2C).

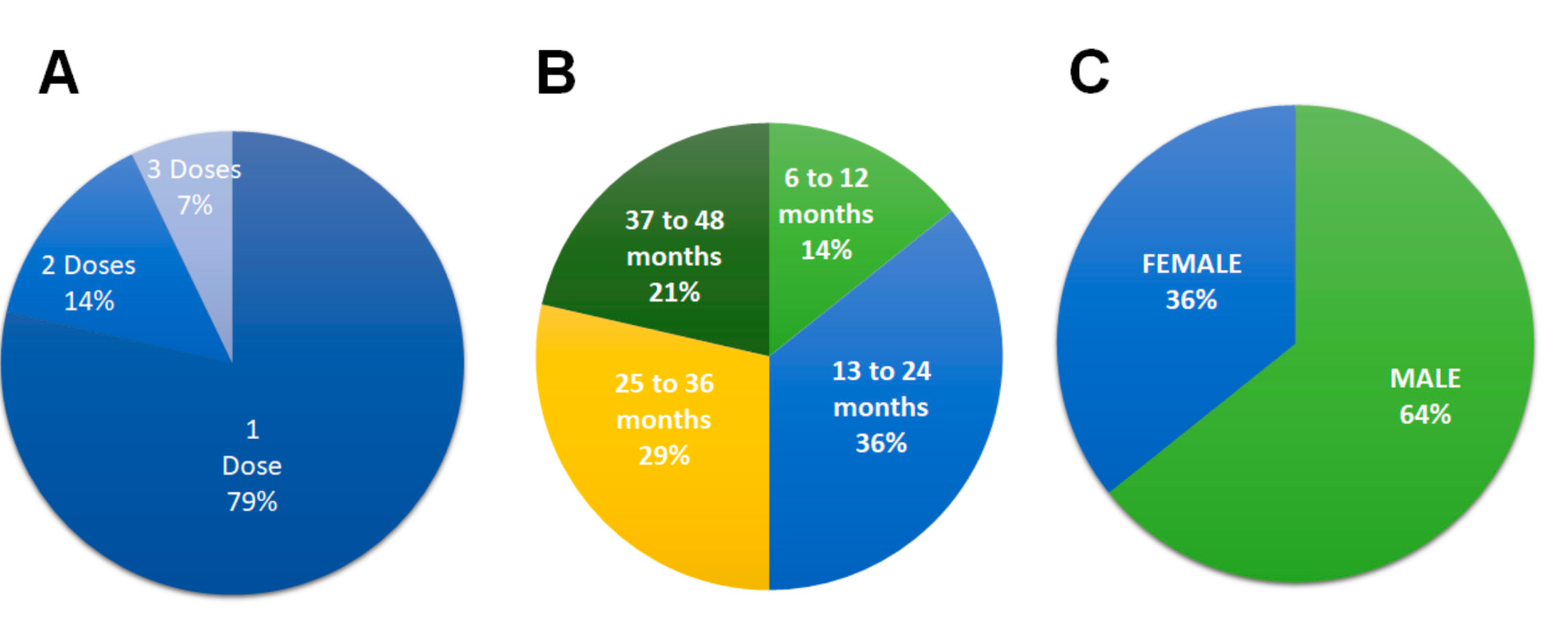

Eleven patients (79%) received a single dose of ASC, two patients (14%) received two doses and one patient (7%) received three doses over a period of 90 days due to the severity of the lesions, although the fistulas closed within one month, signs of inflammation remained; and after the last dose no recurrence was shown until 12 and 24 months in the patients who received 2 doses and 48 months in the patient who received 3 doses (

Figure 3A). The difference in post-cell therapy follow-up is due to the different presentation times of the cases within study period.

In the study period, out of a total of fourteen patients, (100%) had no recurrence after 12 months’ post-treatment. By the end of the study of the fourteen patients, five (36%) patients had no recurrence 13-24 months after treatment, the fistula did not recur between 25-36 months in four patients (29%) and three patients (21%) did not recur between 37-48 months (

Figure 3B). The majority (64%, n = 9) of patients were male (

Figure 3C).

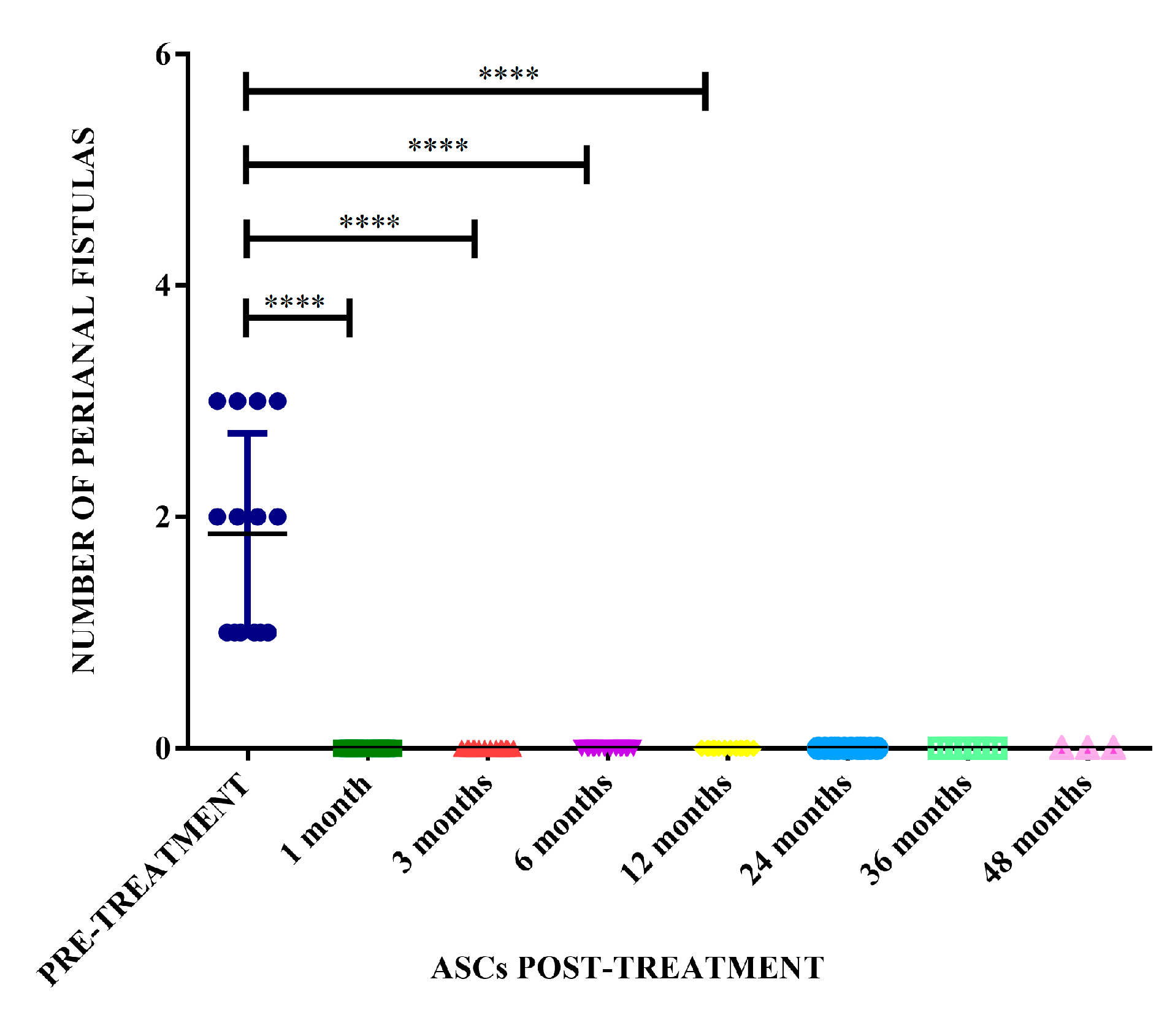

The therapeutic protocol described in the present study achieved a therapeutic efficacy of 100% in the treated dogs presenting complete resolution of the fistula lesions within 3 months, and with remission after one month in some cases (

Figure 4). There was a significant difference in the number of fistulas before treatment compared with the number of fistulas at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after treatment with allogeneic ASC (p <0.0001) (

Figure 5).

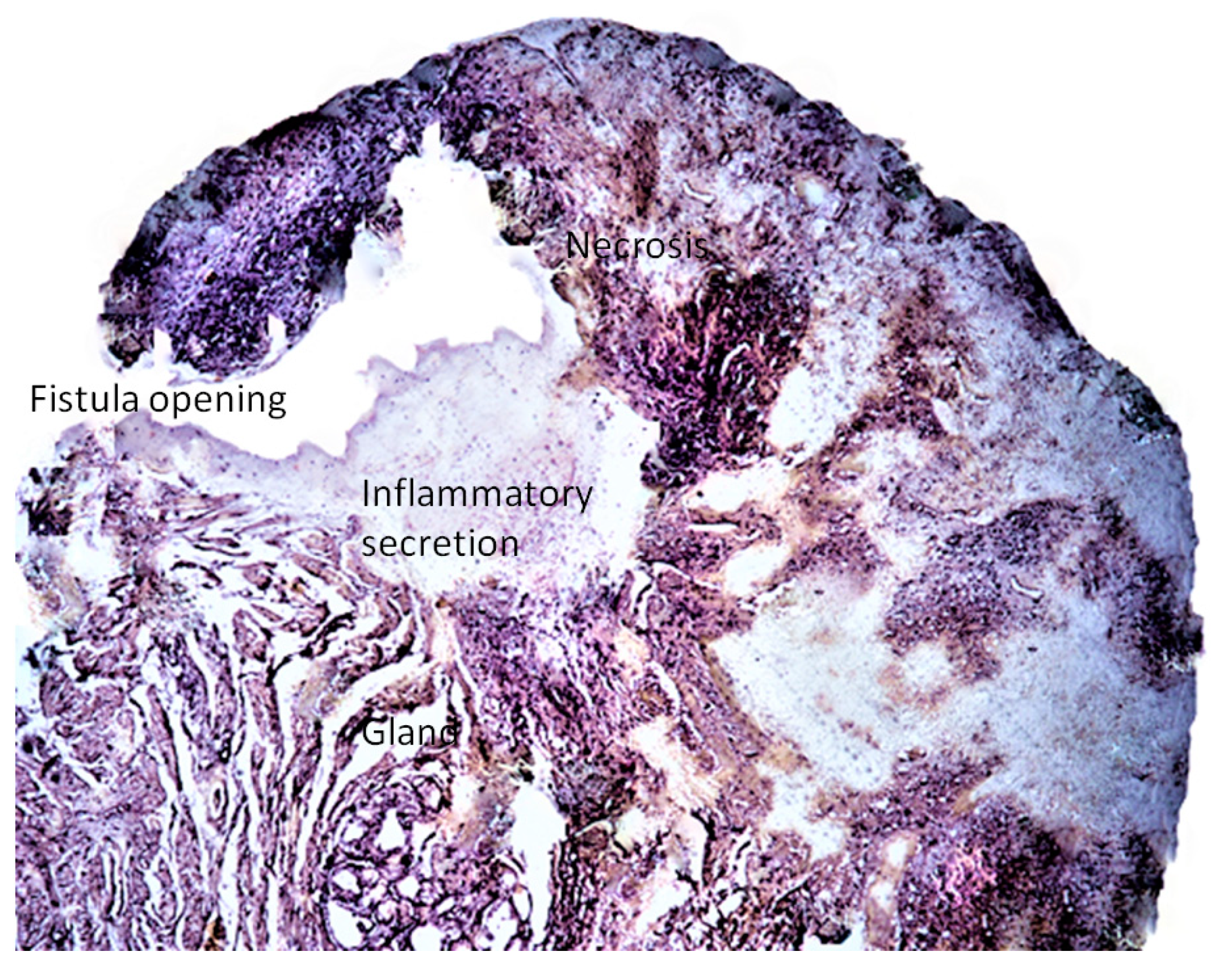

Histological study showed a predominance of active chronic inflammation with epidermal ulcers. In 2 cases the lesions were deeper, presenting pyogranulomatous cellulitis with involvement of the adnexal glands. The inflammatory infiltrate was composed of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages and plasma cells, and the presence of necrotic areas (

Figure 6). However, there was no uniformity regarding the presence of acute and chronic inflammatory cells. For humanitarian reasons, no post-therapy biopsies were performed by request of the owners of the patients.

During the months of follow-up of the study patients, no local or systemic adverse side effects such as fever, hypersensitivity, altered blood cell counts or liver and kidney function (data not shown), and no tumour development were observed.

4. Discussion

The results of this work demonstrate that cryopreserved allogeneic ASCs are effective for the treatment of refractory canine PF, with no recurrence or adverse effects observed in patients for varying periods of time ranging from 12 to 48 months post-treatment in 100% of the cases studied. Our trial is the first to be conducted with this type of cell at low doses and repeated doses in only two cases out of fourteen at 3 months post cell therapy, with prolonged follow-up to monitor for recurrence or adverse effects. In contrast to previous studies in dogs using doses of 2x 107 human embryonic cells/fistula [

10], higher than in our work, it took 3 months to become fistula free and had one case of recurrence at 6 months, which was the follow-up time in this work; while in another experimental study in rabbits with induced perianal fistulas, they used a rabbit adipose stem cell line at a dose of 2x 106 cells/fistula, but the fistulas were sutured beforehand, healing occurred 6 days after therapy and they had a post-therapy follow-up of only 70 days [

18].

It is also important to note that the dose used in this study is five times lower than the dose applied in situ in a recent study in humans with the same cell type [

19], . Although we have no explanation for this remarkable dose difference, perhaps the dose effect is later but more prolonged in humans compared to canines. However, this cannot be verified, as the follow-up time after cell therapy in both studies was medium-term. However, a recent review study found that the difference in cell types, cell sources and cell dose did not influence the mid-term efficacy of MSCs in humans [

20], but we believe that the difference in dose may be explained by having different interspecies immune response mechanisms.

Regarding the efficacy of ASCs administration in the FPs reported in the present study, it could be explained by the same mechanisms described for immune-mediated and inflammatory diseases, since the histological study of the present cases showed the involvement of chronic active inflammation coincident with the descriptions of Killingsworth et al [

21], as previously proposed by Day [

15,

22]. This could be explained by the fact that MSCs have been shown to be effective in the treatment of multiple immune-mediated diseases in humans and in animals with spontaneous disease [

7]. Likewise, the mechanism of action of stem cells has been demonstrated in inflammatory and immune-mediated processes[

6], in refractory wounds in dogs [

15] and in canine atopic dermatitis [

13,

23], all of these diseases are caused by inflammatory and immune-mediated processes, similar to the pathogenesis of canine perianal fistula.

Moreover, despite the small sample size of the present study, we found that 100% of cases responded satisfactorily, with 79% (11/14) of ASC-treated dogs requiring only one dose, and 86% (12/14) were relapse-free for at least 24 months after treatment. One patient has been relapse-free for 48 months. Which, when compared to the current approach we see that for many years, FPs have been approached with surgical procedures that, besides not being curative, can lead to the development of collateral damage such as anal stenosis and fecal incontinence [

24,

25]. While in pharmacological treatment which is currently the treatment of choice, medical protocols use cyclosporin A but cannot guarantee cure of the disease [

12]. In fact, not all cases respond satisfactorily and pharmacological treatment can be associated with numerous adverse effects [

1]. Moreover, less satisfactory long-term results can be observed, such as recurrence of lesions in 30-50% of dogs treated with cyclosporin A [

26].

Whereas in this study, during the 12 to 48 months of follow-up, no adverse effects were observed in any of the cases studied, so we can affirm that the ASCs used in this study are innocuous and did not induce any adverse disorder. This quality of the cells used in this study could be explained by the absence of immunogenicity due to the lack of MHC class II and very low levels of MHC-I [

27]. This biological quality could contribute to standardize application protocols and the dose used, as suggested in other studies [

28]. Also, by having a long-term follow-up of up to 4 years, it decreases the risk of the main concern regarding the administration of MSCs, which is the possibility that they may promote tumor development by inducing neoplastic cell proliferation and neoangiogenesis [

29], although no case of tumor has yet been described [

30].

Although this study included a small number of patients (n = 14), it is the largest evaluation of the use of low-dose allogeneic adipose stem cells in cases of spontaneous perianal fistula, and with a medium- and long-term follow-up considering the life expectancy of the canine species. In addition, it is pertinent to note that due to the economic limitations of the owners, MRI could not be routinely performed during the follow-up of the patients. However, our results may have translational value for optimizing MSC transplantation procedures in human patients with perianal Crohn's disease, taking into account the low dose of stem cells used in this work compared to the high doses used in humans described in other studies [

11,

31].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study show that exclusive administration of allogeneic cryopreserved adipose stem cells at a low dose of 5x106/fistula according to the new protocol described in this study completely resolved perianal fistulas 1-3 months after in situ application in 100% of the cases studied. There was no recurrence of initial clinical manifestations for 12-48 months depending on follow-up time, and no local or systemic adverse effects were observed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: NE, JE; Methodology: JE, NE; Data curation: JE-B, JE; Formal analysis: JE; Investigation: JE, JE-B; Software: NE; Resources: JS, JE; Supervision: JS; Validation: NE, JE; Writing - original draft: JE; Writing - review & editing: NJ; JE-B, JE.

Funding

This research was funded by Agreement No. 053-FIDECOM-INNOVATE PERU PIMEN-2018 in addition by the Clínica Veterinaria Enciso, the Universidad Científica del Sur and the Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia de la Universidad San Luis Gonzaga de Ica, Perú.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This trial was approved by the Ethics Commission of the San Luis Gonzaga National University of Ica, Peru (Resolution No. 3, Ethics Commission)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for treatment was obtained from all animal owners.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Harvey, R.; Horton, H. Successful treatment of perianal fistulas in two dogs with oclacitinib. Vet Dermatol 2023, 34, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, C.L. Canine Perianal Fistulas: Clinical Presentation, Pathogenesis, and Management. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2019, 49, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Zhu, K.; Guo, Y.; Wang, E.; Huang, J. Evaluation of animal models of Crohn's disease with anal fistula (Review). Exp Ther Med 2021, 22, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, S.; Luber, R.P.; Tamilarasan, G.; Dinneen, E.; Irving, P.M.; Samaan, M.A. Emerging Treatments for Crohn's Disease: Cells, Surgery, and Novel Therapeutics. EMJ 2021, 6, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund, B.; Feakins, R.M.; Barmias, G.; Ludvig, J.C.; Teixeira, F.V.; Rogler, G.; Scharl, M. Results of the Fifth Scientific Workshop of the ECCO (II): Pathophysiology of Perianal Fistulizing Disease. J Crohns Colitis 2016, 10, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panés, J.; Rimola, J. Perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease: pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 14, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasim, S.A.; Yumashev, A.V.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Margiana, R.; Markov, A.; Suksatan, W.; Pineda, B.; Thangavelu, L.; Ahmadi, S.H. Shining the light on clinical application of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.H.; Kim, H.K.; Na, J.Y.; Jin, C.; Seon, J.K. Anti-inflammatory effects of mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned media inhibited macrophages activation in vitro. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panés, J.; García-Olmo, D.; Van Assche, G.; Colombel, J.F.; Reinisch, W.; Baumgart, D.C.; Dignass, A.; Nachury, M.; Ferrante, M.; Kazemi-Shirazi, L.; et al. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, L.; Kimbrel, E.A.; Lam, A.; Falk, E.B.; Zewe, C.; Juopperi, T.; Lanza, R.; Hoffman, A. Treatment of perianal fistulas with human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells: a canine model of human fistulizing Crohn's disease. Regen Med 2016, 11, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdzinska, A.; Galanty, M.; Więcek, S.; Dabrowski, F.A.; Lotfy, A.; Sadkowski, T. The Intersection of Human and Veterinary Medicine-A Possible Direction towards the Improvement of Cell Therapy Protocols in the Treatment of Perianal Fistulas. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Fazio, V.W.; Feagan, B.G.; Hanauer, S.B. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2003, 125, 1508–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enciso, N.; Amiel, J.; Pando, J.; Enciso, J. Multidose intramuscular allogeneic adipose stem cells decrease the severity of canine atopic dermatitis: A pilot study. Vet World 2019, 12, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowski, M.; Giovino-Doherty, M.; Ji, L.; Shi, M.; Smith, K.P.; Laning, J. Basic pluripotent stem cell culture protocols. StemBook [Internet].

- Enciso, N.; Avedillo, L.; Fermín, M.L.; Fragío, C.; Tejero, C. Cutaneous wound healing: canine allogeneic ASC therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther 2020, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molendijk, I.; Bonsing, B.A.; Roelofs, H.; Peeters, K.C.; Wasser, M.N.; Dijkstra, G.; van der Woude, C.J.; Duijvestein, M.; Veenendaal, R.A.; Zwaginga, J.J.; et al. Allogeneic Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Promote Healing of Refractory Perianal Fistulas in Patients With Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Wang, P.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chao, M.; Wang, W. Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Are an Efficient Treatment for Fistula-in-ano of Japanese Rabbit. Stem Cells Int 2019, 2019, 6918090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, I.; Yanai, H.; Avni, I.; Slavin, M.; Naftali, T.; Tovi, S.; Dotan, I.; Wasserberg, N. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for Crohn's perianal fistula-a real-world experience. Colorectal Dis 2024, 26, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Jin, H.Y.; Fei, B.Y.; Jiang, J.L. Mesenchymal stem cells transplantation for perianal fistulas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Stem Cell Res Ther 2023, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killingsworth, C.R.; Walshaw, R.; Dunstan, R.W.; Rosser, E.J., Jr. Bacterial population and histologic changes in dogs with perianal fistula. Am J Vet Res 1988, 49, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Day, M.J. Immunopathology of analfurunculosis in the dog. Journal of Small Animal Practice 1993, 34, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Ramos, F.; Malard, P.F.; Brunel, H.; Paludo, G.R.; de Castro, M.B.; da Silva, P.H.S.; da Cunha Barreto-Vianna, A.R. Canine atopic dermatitis attenuated by mesenchymal stem cells. J Adv Vet Anim Res 2020, 7, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, A.; Campbell, K.L. Managing Anal Furunculosis in Dogs. Compendium on Continuing Education for The Practicing Veterinarian 2005, 27, 339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, G.W. Treatment of perianal fistulas in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1995, 206 11, 1680–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B.J.; Hauptman, J.G. Long-term prospective evaluation of topically applied 0.1% tacrolimus ointment for treatment of perianal sinuses in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 4.

- Zhang, R.; Duan, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Al-Bashari, A.A.G.; Ye, P.; Ye, Q.; He, Y. The Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Future Vaccine Synthesis. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.-H.; Park, H.-M. Challenges of stem cell therapies in companion animal practice. Journal of Veterinary Science 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.-H.; Chang, M.-C.; Tsai, K.-S.; Hung, M.-C.; Chen, H.-L.; Hung, S.-C. Mesenchymal stem cells promote growth and angiogenesis of tumors in mice. Oncogene 2013, 32, 4343–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberspacher, C.; Mascagni, D.; Ferent, I.C.; Coletta, E.; Palma, R.; Panetta, C.; Esposito, A.; Arcieri, S.; Pontone, S. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Cryptoglandular Anal Fistula: Current State of Art. Front Surg 2022, 9, 815504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lightner, A.L.; Kurowski, J.; Otero-Pinerio, A.M. Direct Injection of Ex Vivo Expanded Allogeneic Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Treatment of Pediatric Crohn's Perianal Fistulizing Disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2024, 67, e115–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).