1. Introduction

Native to northern Ethiopia, arabica coffee (

Coffea arabica L., Rubiaceae) is a tropical woody crop with great genetic value that is one of the most traded crops worldwide [

1,

2]. Twenty-five million agricultural households, mostly smallholders, grow coffee in 80 tropical countries for the consumption of one-third of the world's population [

3,

4].

Coffee is the second most valuable commodity in the world after oil, with sales estimated to be worth US

$102 billion globally [

5]. World coffee production was between 158 and 178 million 60 kg bags per year for the years 2023-2024 [

6]. In Ecuador, coffee is a product of great social, economic and environmental importance [

7] and its production during 2019-2020 was 559,000 and 500,000 bags, respectively, with a percentage of change of -10.5% [

5].

In Brazil coffee has been extensively investigated ecophysiologically [

4,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], while in Ecuador such studies are scant [

14]. Ecuador's genetic improvement programs lack physiological information, particularly on the physiological response to water deficit (WD), despite knowledge on production, pests, and diseases tolerance in various coffee genotypes [

7,

14,

15]. In order to choose coffee genotypes with improved physiological performance in WD conditions in Ecuador's various agroecological zones, it is necessary to understand the potential traits.

Due to global climate change, projections for Ecuador in 2050 indicate temperatures could rise by up to 2.5 °C, along with less rainfall and longer, more unpredictable droughts [

16]. These temperature changes, coupled with increased climate variability, are anticipated to pose a danger to global agricultural productivity and sustainability, having a significant impact on the quantity and quality of crops, such as coffee [

17,

18,

19]; these situations emphasize how important it is to comprehend how tropical crops responses physiologically to WD [

3,

20].

The

Coffea species is very sensitive to climate change, according to modeling studies based on predictions of rising temperatures and shifting patterns of precipitation [

3]. Changes in microclimatic factors, particularly those associated with WD, have a significant impact on coffee output and bean quality [

20,

21].

The physiological responses of plants to WD are intricate due to the disruption of numerous metabolic systems. Reduced growth and yield are caused by a drop in net photosynthetic rate (A) resulting from either impaired metabolic processes or reduced CO

2 diffusion to carboxylation sites [

22]. A wide range of plant responses to drought can be attributed to the physiological, biochemical, morphological, and molecular mechanisms involved; they include dynamic soil water depletion and failure to meet the water demands of growing coffee plants at different phenological states [

20].

Low water availability reduces coffee production by interfering with the roots' ability to extract moisture, the roots' distribution in space, the size of the canopy, and the growth of their fruit [

9]. A key factor in the genotypes of arabica coffee's variable tolerance to low water availability could be attributed to physiological and morphological features that influence water uptake and loss, such as A, stomatal conductance (g

s), water use efficiency (WUE) and root depth, which should be recommended as traits for the potential selection of coffee genotypes with higher yields subjected to WD [

9,

23,

24]. Understanding how WD affects arabica coffee's physiology and metabolism is crucial for developing drought resistant varieties [

20,

25].

We assessed the impact of WD on leaf and soil water status, leaf gas exchange, and growth traits of four Coffea arabica genotypes: Sarchimor 4260, Red Caturra, Catimor ECU 02, and Cavimor ECU. Finding potential characteristics to choose coffee genotypes with improved physiological performance in low-water environments was the goal of this study. This information can offer understandings into whether differences in genetic variability among C. arabica genotypes explain photosynthetic differences, and if the physiological response to WD is different among genotypes. Under WD, we hypothesized that: 1) coffee genotypes will respond differently from one another due to varying physiological performance; and 2) coffee genotypes might have varying effects on WUE.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Site Conditions

The investigation was carried out in 2017 at 20 m.a.s.l at the Mutile Experimental Station, Universidad Técnica Luis Vargas Torres, in the Esmeralda Province of Ecuador (0 ° 53' 40" N; 79 ° 37´23" W). The research area's parameters include mean air temperature (T

a) of 24 °C, relative humidity (RH) of 85%, heliophany of 1,200 hours of sunlight per year, and mean annual precipitation of 1,030 mm [

26]. One-year-all arabica coffee seedlings were raised in a 400-m

2 shed shielded with a neutral polythene sheet, whereafter named shade house. Utilizing a light meter (LI-250l, LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA), the photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) was determined. Values for the leaf-to-air vapor pressure deficit (Δ

W) were obtained using T

a and RH data, following Jones' [

27] equation.

Table 1 displays the values of the shade house's microclimatic parameters. Shading reduced PPFD incident at noon on the roof to 20 %.

2.2. Plant Material

The

Coffea arabica genotypes Sarchimor 4260, Red Caturra, Catimor ECU 02, and Cavimor ECU, which are commonly used in Ecuador, were chosen for this study due to their high production and resistance to coffee rust (

Table 2). In the most important coffee-producing regions of Esmeraldas Province, Ecuador, we gathered seeds. Ten-month-old seedlings were cultivated, under semi-controlled conditions in the shade house, in bags with 10 kg of sandy loam soil (pH = 6.0; organic matter = 2 %; total N = 0.1 %; total P = 21 mg kg

-1; total K = 1.4 cmol kg

-1) and watered every two days. In order to ensure seedling growth and establishment, we fertilized plants once a month (10 g month

-1) with N:P:K 12:11:18, a dose that has been shown to yield the greatest outcomes.

2.3. Experimental Design

A complete random block design was utilized with four genotypes, each with 20 plants and three repeats, for a total of 60 plants per genotype and 240 plants in total. In the shade house, three blocks totaling 121 m2 were set up, with 20 plants of each genotype spaced one meter apart in each block. Every block was separated by two meters. To prevent potential block and edge effects, plants were shifted weekly within and across blocks within each treatment. During seven months (February to August 2017), all physiological parameters were measured on seedlings that were ten months old. For each genotype (n = 5), a sample was taken from the central region of a fully opened, healthy leaf, which was the third leaf from the top.

2.4. Water Deficit Experiment

Irrigation in 10 seedlings of each genotype per block (total of 30 plants) was completely stopped for 29 days and corresponded to the water deficit treatment (WD). The remaining 30 plants were maintained well-watered and corresponded to the control. We measured water status as soil and leaf water contents, gas exchange variables, and performed A/Ci curves on days 0 (the first without irrigation) and on the following days: 8, 15, 22, and 29. On day 29, we started irrigation again, and the following day (on day 30), we took measurements of the same set of physiological variables.

2.5. Water Status

To determine the soil water content (SWC), relative water content (RWC), and leaf water content (LWC), samples of soil and leaves were collected. After soil samples were taken at a depth of 15 cm, their fresh weight (FW) was calculated, they were dried for 48 hours at 70 °C to achieve a constant mass, and then they were weighed to obtain their dry weight (DW). Soil water content was calculated as [(FW - DW) / FW] × 100. Ten leaves (n = 10) were collected between 7:00 and 8:00 h, and the leaf water content (LWC) was calculated as (FW - DW)/DW. To calculate the turgid weight (TW), ten leaves (n = 10) were gathered at 07:00 h and floated on distilled water at 4 °C for one hour. Leaf relative water content was then calculated as RWC = (FW-DW)/(TW-DW). The specific leaf area (SLA), which is the ratio of leaf area to DW, was determined by measuring the fresh area and DW of leaves taken from six individuals per genotype.

2.6. Gas Exchange

A portable infrared gas analyzer (CIRAS-II, PP Systems, MA, USA) in open mode linked to a PLC(B) leaf chamber was used to measure the gas exchange variables (A, gs, and E) in intact leaves in five individuals of each genotype (n = 5 per genotype). With PPFD of 1200 ± 10 μmol m-2 s-1 delivered by an LED Based Light Unit from PP systems Inc., measurements were conducted at a CO2 concentration of 410 ± 10 μmol mol-1, a leaf temperature of 30.0 ± 0.5 °C, and a ΔW of 1.8-2.2 kPa. The WUE was calculated as the ration between A and E. Every genotype that was randomly sampled had measurements taken throughout the course of three days, from 8:00 to 12:00.

2.7. A/Ci Curves

We performed A/C

i curves (n = 4) by gradually raising C

a to 1.800 μmol mol

-1 after first lowering C

a to zero. The A/C

i measurements were conducted in a leaf chamber with the following parameters: Δ

W of 1.8 ± 0.02 kPa, PPFD of 1.200 ± 10 μmol m

-2 s

-1, and leaf temperature of 30.0 ± 0.5 °C. An empirical equation was used to fit curves [

28] that yields the carboxylation efficiency (CE), as the slope of the initial part of the curve. Using the equations in [

29] and [

30], the values of the relative stomatal limitation (L

s) and mesophyll limitation (L

m) were determined. Finally, the model in [

31] was used to compute the maximum rate of electron transport through photosystem II (J

max), the maximum rate of carboxylation by RuBisCO (V

cmax), and the triose phosphates utilization rate (TPU).

2.8. Growth

By weighing paper copies of the leaves and one square centimeter of paper, as well as by figuring out the link between paper mass and area, leaf area was measured allometrically. After oven drying at 70 ºC to a constant mass, these leaves were weighed with an analytical weighing balance (Model HR200, Japan). Throughout the course of the experiment, non-destructive allometric growth measurements were performed every two weeks for six months on five plants (n = 5) per treatment. The following measurements were taken: plant total height, measured from ground level to the apical shoot; stem diameter at 10 cm from ground level; crown diameter at the lower part of each plant, on the longest lower branch of the plant – branch length of the intermediate branch of the plant is considered and measured from the insertion of the branch in the central stem to the terminal bud –; number of branches present on the stem of the plant; flowering. For flowering an arbitrary scale from 0 to 3, where 0 = no flowering, 1 = low, 2 = medium and 3 = high intensity of flowering was used.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The data displayed in tables and figures are expressed as means (5 ≤ n ≤ 10) ± standard error (SE). Statistical package, STATISTICA v10 (StatSoft Inc., OKlahoma, USA), was used to perform one and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's post hoc test at the 5% level of significance. Water status, gas exchange, and A/Ci traits were compared across four genotypes and between control and WD within each genotype using ANOVAs. SigmaPlot 11 (Systat Soft-ware, California, USA) was used for all regressions, whether they were linear or curvilinear, and significance was assessed at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The findings validated our hypothesis 1 by demonstrating differences in gas exchange and growth characteristics among four genotypes of healthy, well-irrigated arabica coffee plants. Under irrigated conditions, the genotypes Cavimor ECU and Catimor ECU 02 exhibited the greatest physiological achievement, i.e., great A and WUE. Since 15 to 29 days without irrigation resulted in a significant drop in soil and leaf water status, photosynthetic variables, and growth parameters, all four genotypes were susceptible to WD. We noticed variations in genotype response to WD, indicating variations in drought tolerance. The results indicated that Catimor ECU 02 and Cavimor ECU were more resistant to WD, while red Caturra and Sarchimor 4260 were the most susceptible. The results are consistent with our hypothesis 2, which states that different arabica coffee genotypes would experience different effects on WUE due to physiological plasticity. Specifically, WUE was more reduced during WD in the Sarchimor 4260 and red Caturra genotypes than in the Cavimor ECU and Catimor ECU 02 genotypes; however, after re-irrigation for one day, WUE values rapidly regained in the Cavimor ECU and Catimor ECU 02 genotypes, but not in the Sarchimor 4260 and red Caturra genotypes.

Significant difference in water status and gas exchange performance of plantlet of the four genotypes develop under in semi-controlled conditions suggested physiological adaptability amidst genotypes. The research showed values of A and g

s that are greater than those observed in 31 varieties of

C. arabica and

C. canephora clones evaluated in Ecuador [

14,

33] and comparable to those found in

C. arabica in Brazil, Colombia, and Ethiopia [

4,

25,

32]. For arabica and conilon coffee, mean values of A of 8 μmol m

-2 s

-1 and g

s of 148 mmol m

-2 s

-1 have been observed in Brazil [

34].

The study's g

s values, which ranged from 277 to 400 mmol m

-2 s

-1 [

14], were higher than those found in prior studies on arabica and conilon coffee (which had g

s values of 108 and 148 mmol m

-2 s

-1, respectively [

34]). The WUE observed in the study was comparable to that reported for clones of robusta and arabica coffee (2.8 and 3.8 mmol mol

-1, respectively), assessed in the field and in greenhouses [

14,

25,

32]. As SWC decreased under WD, a reduction in LWC and RWC in all four genotypes studied suggested that these were susceptible to water shortage. Coffee does not tolerate dehydration, nevertheless, as it maintains a relatively high RWC in dry conditions, making it a species that conserves water [

35].

The four

C. arabica genotypes under evaluation showed varied responses to WD in terms of leaf gas exchange (A, g

s, E, and WUE). Similar results have been reported in arabica coffee [

25,

32]. In contrast, in two

C. canephora clones gas exchange was unaffected by WD, although their water status was negatively affected by WD [

23]. In Ecuador, it was found that in twenty-one

C. arabica cultivars under WD in field conditions A, g

s and WUE differed significantly among cultivars [

14]. Cultivar Cavimor ECU had the highest A and WUE, maintained the values of these parameters up to 22 days of WD and showed full recovery with irrigation, suggesting that this cultivar could be selected for growth in areas subject to WD; however, further research under natural conditions is urgently required.

Results of WUE were significantly higher in Cavimor ECU and Catimor ECU 02, while the lowest were found in red Caturra. We conclude that A and WUE could be indicators of the tolerance of coffee cultivars to WD. In Sarchimor 4260 and red Caturra genotypes (sensitive to WD), A and g

s were significantly reduced by water deficit more than in Catimor ECU 02 and Cavimor ECU, making the latter two more tolerant to WD. These results suggest that during the seedling stage, arabica coffee has physiological adaptability to WD. Previous reports have shown comparable outcomes with WD for arabica coffee genotypes – the sensitive Ca754 and CaJ-19 genotypes, as well as the Castillo variety, and the comparatively tolerant Ca74110 and Ca74112 [

25,

32]. The gas exchange of 21 genotypes of

C. arabica that were assessed in field conditions decreased due to drought [

14].

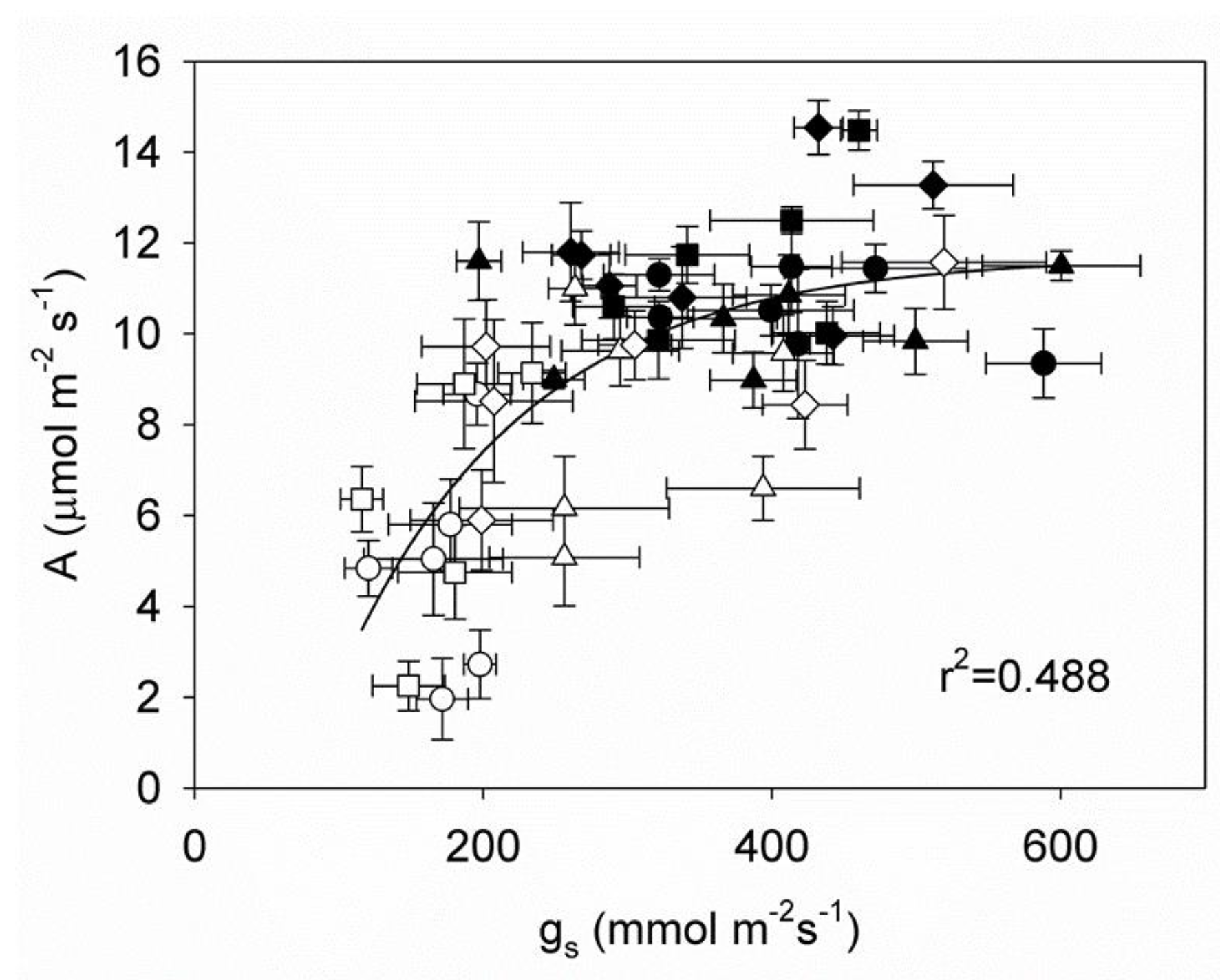

Gas exchange and related variables showed bimodal responses to WD. At first, as RWC decreased, A and g

s declined as well, but C

i remained constant, indicating that stomata were not significantly limiting A under WD. Nevertheless, C

i under WD remained constant with an average C

i/C

a ratio of 0.77, suggesting that metabolic limitation of A became increasingly significant even if the relationship between A and g

s in this study was curvilinear. This interpretation of the data is supported by the observation that after one day of re-irrigation, A was fully restored in Cavimor ECU and Catimor ECU 02 but not in Sarchimor 4260 and red Caturra. In contrast, genotypes of

C. arabica from Brazil and Ecuador have previously shown significant linear relationship between A and g

s [

14,

34], but not in conilon [

34] or in robusta, indicating that in

C. canephora cv. robusta coffee clones A was independent of g

s [

33].

Reduces in RWC, A, and g

s without alterations in WUE in Catimor ECU 02 and Cavimor ECU after 29 days of WD were a general pattern that indicated coffee genotypes optimizing water use. Similarly, WUE did not change in arabica coffee in response to drought [

14]. Water limitation may result in a decrease in A due of stomatal limitation, because of reductions in g

s-related stomatal closure and decreases in C

i and/or through damage of metabolic process [

22]. With the exception of Cavimor ECU, the majority of all four genotypes closed their stomata in response to WD, resulting in a drop in g

s and a consequent avoidance of excessive water loss and reductions in A. Since WD had no effect on C

i, we do not completely rule out the possibility that metabolic variables were crucial in the regulation of A [

22]. With the exception of Cavimor ECU and Catimor ECU 02, where colimitation of A by stomatal and metabolic factors occurred, values of L

s remained constant during the 29 days of WD, while L

m increased gradually in all four cultivars. This suggests that, as WD increased, biochemical and photochemical regulation of A became more important than decline in g

s (stomatal closure). This implies that the regulation of A by photochemical and biochemistry became increasingly significant as WD rose, rather than stomatal closure (i.e. the reduction of g

s).

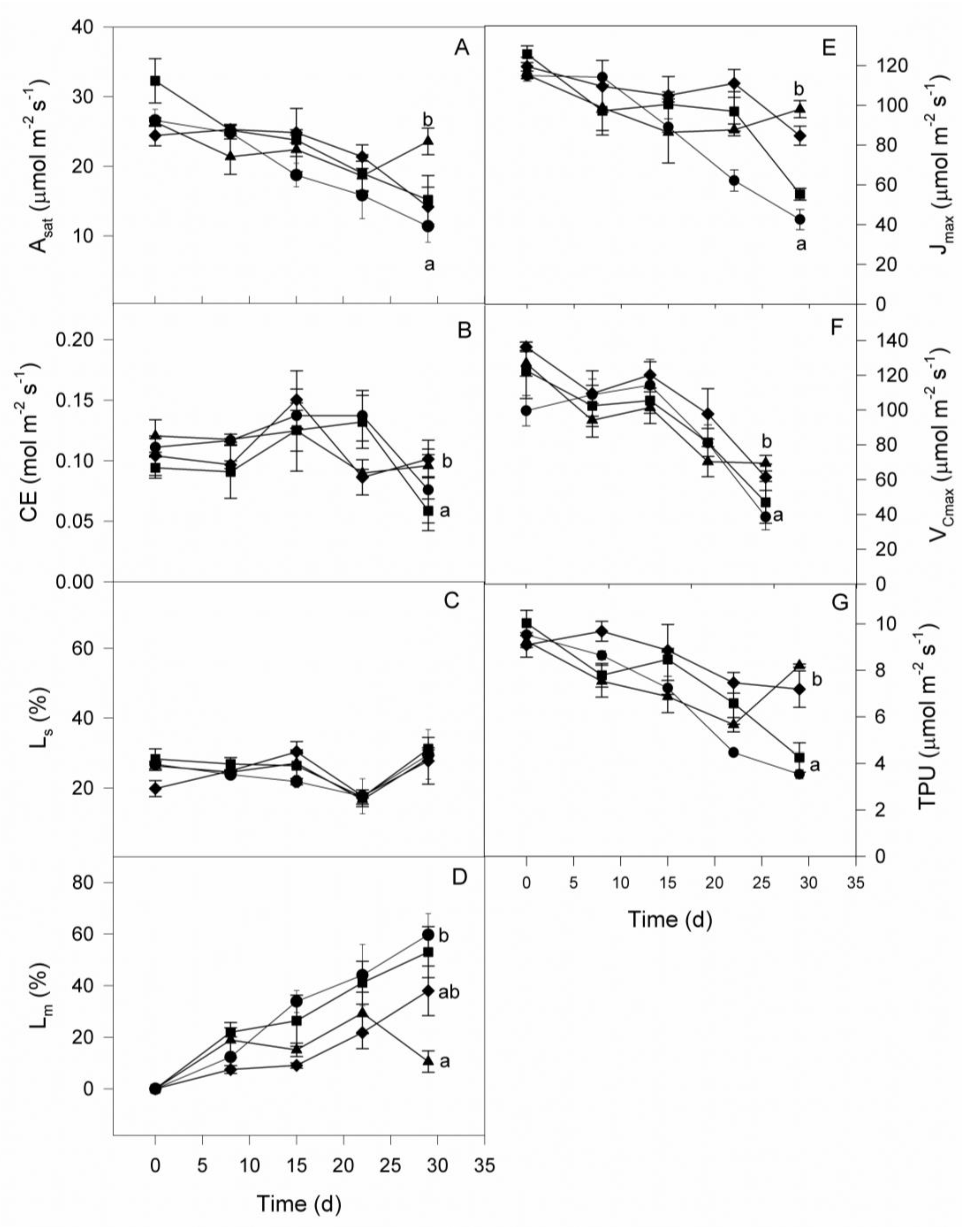

All four genotypes had comparable photosynthetic capacities, which were influenced by WD in distinct ways as seen by the A/C

i curves. Control plants showed the maximum photosynthetic capacity, determined under saturating PPFD (A

sat) of 24-32 μmol m

-2 s

-1, similar to reported values up to 30 μmol m

-2 s

-1 [

36,

37]. In Sarchimor 4260, red Caturra and Cavimor ECU, the noted declines in A

sat and CE with decreasing A discernible decrease in V

cmax and J

max, respectively, suggests that WD had a significant impact on the activity and/or quantity of RubisCO and the availability of RuBP. In contrast, only a small reduction of CE and A

sat was found in Catimor ECU 02, which suggested that no metabolic process was impaired. Our estimations of biochemical parameters in the four

C. arabica cultivars studied support data reported before in red Catuai and arabica coffee by [

38,

39] and the values of V

cmax, J

max and TPU were higher than the results reported in Catimor [

2].

Both the Catimor ECU 02 and Cavimor ECU genotypes, which partially tolerant to WD, displayed a significantly rapid and better recovery from the negative effects of WD following a single day of re-irrigation. The four arabica coffee genotypes showed notable variations in the A/C

i curve parameters; Catimor ECU 02 and Cavimor ECU showed less variation than Sarchimor 4260 and red Caturra. In addition to affecting A

sat, J

max, CE, and V

cmax, water deficit also increased L

m by 56% on average in two genotypes that were sensitive, indicating that both stomatal closure (to a lesser extent) and metabolic, photochemical, and/or biochemical limitations during WD were responsible for the reduction of A. In contrast, L

s accounted for 40% of the constraints in red Catuai grown in both full sun and shade, whereas L

m made up 30% of the constraints in the same radiation conditions [

39].

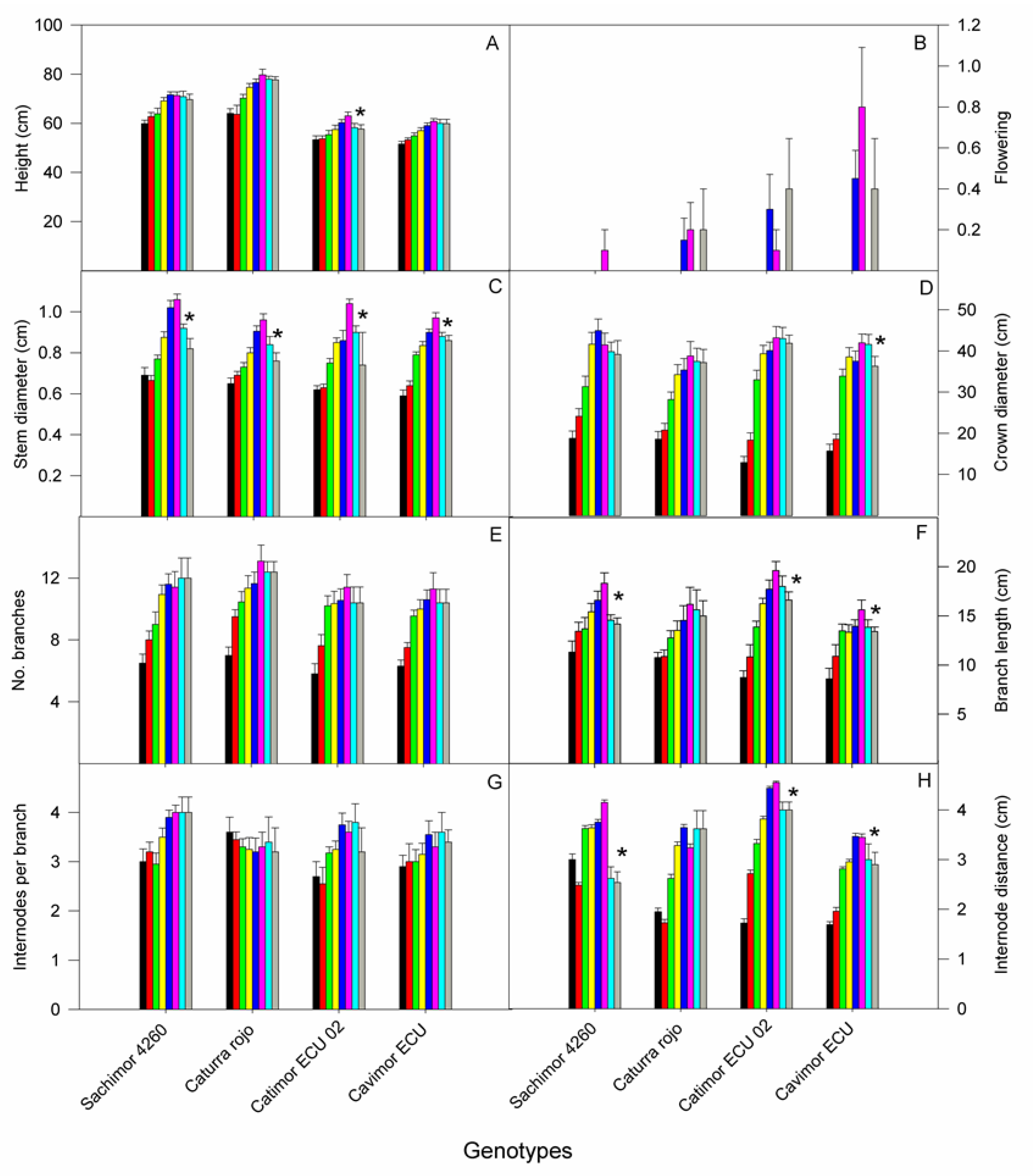

Water deficit caused a reduction in some growth variables, this effect being stronger in Sarchimor 4260 and red Caturra than in Catimor ECU 02 and Cavimor ECU. Similar results, except for stem height, shoot fresh mass and dry biomass, were reported in tolerant and sensitive arabica coffee genotypes under drought [

25], supporting the observation that WD reduces crop yields by affecting the plant’s vegetative growth [

9].

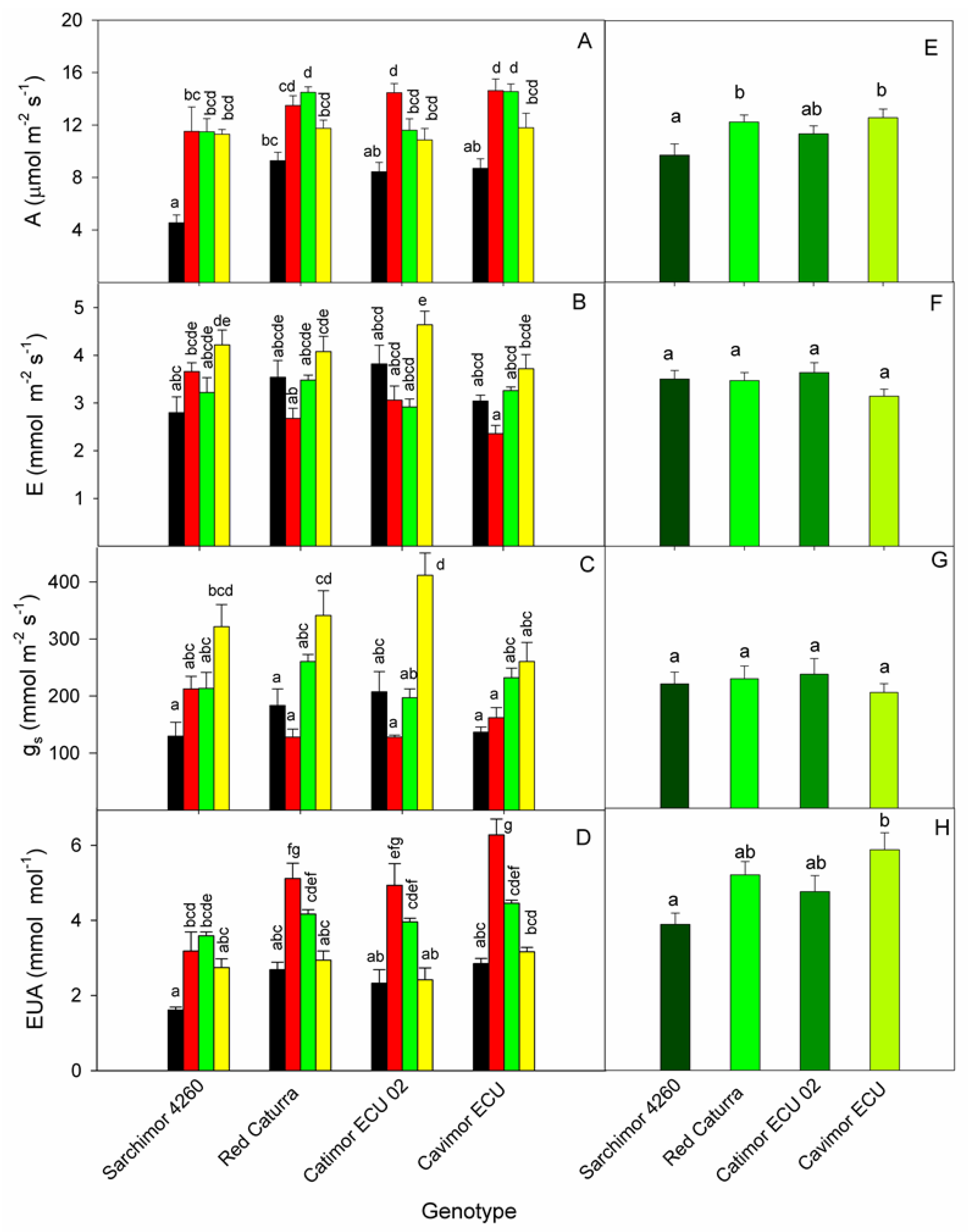

Figure 1.

Gas exchange parameters of four arabica coffee genotypes. A, E) Net photosynthetic rate; B, F) transpiration rate; C, G) stomatal conductance; D, H) instantaneous water use efficiency. The vertical bars represent the mean of five plants ± SE. Distinct letters indicate significant variations in genotypes and/or sampling time (p < 0.05). Every bar shows a distinct sampling in February (black), March (red), April (green) and May (yellow) 2017. Panels E, D, F and G show the means of all samples for each genotype.

Figure 1.

Gas exchange parameters of four arabica coffee genotypes. A, E) Net photosynthetic rate; B, F) transpiration rate; C, G) stomatal conductance; D, H) instantaneous water use efficiency. The vertical bars represent the mean of five plants ± SE. Distinct letters indicate significant variations in genotypes and/or sampling time (p < 0.05). Every bar shows a distinct sampling in February (black), March (red), April (green) and May (yellow) 2017. Panels E, D, F and G show the means of all samples for each genotype.

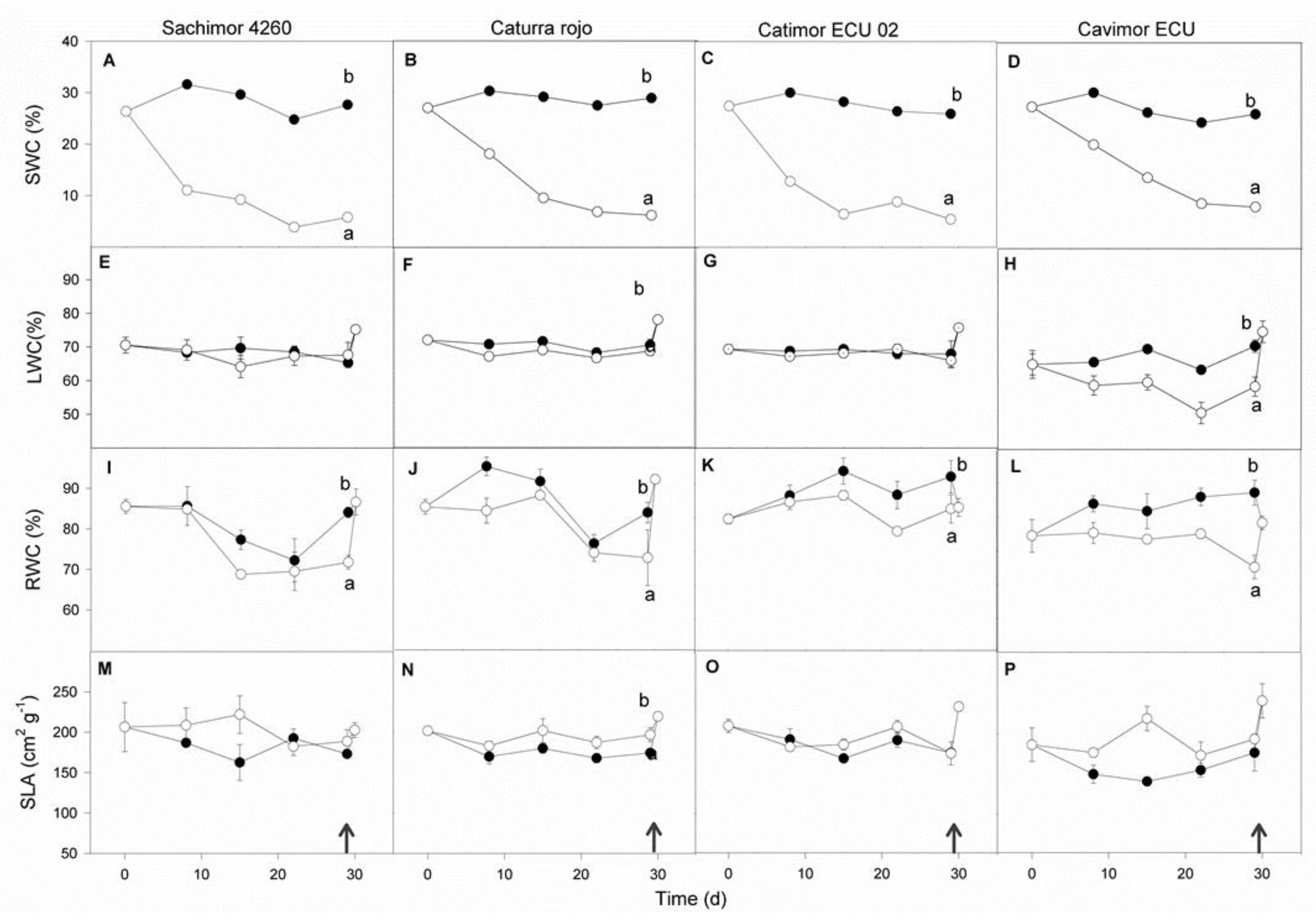

Figure 2.

Effects of water deficit duration on four coffee genotype plants' leaves: A-D, soil water content (SWC); B-H, leaf water content (LWC); I-L, relative water content (RWC); and M-P, specific leaf area (SLA), in both WD (open circles) and control (closed circles) plants. Genotype name is shown above the uppermost panels. The data represent means (6 ≤ n ≤ 10) ± SE. For each parameter at p < 0.05, distinct letters denote significant variations between WD and control seedlings. Measurements taken a day after re-irrigation are indicated by arrows.

Figure 2.

Effects of water deficit duration on four coffee genotype plants' leaves: A-D, soil water content (SWC); B-H, leaf water content (LWC); I-L, relative water content (RWC); and M-P, specific leaf area (SLA), in both WD (open circles) and control (closed circles) plants. Genotype name is shown above the uppermost panels. The data represent means (6 ≤ n ≤ 10) ± SE. For each parameter at p < 0.05, distinct letters denote significant variations between WD and control seedlings. Measurements taken a day after re-irrigation are indicated by arrows.

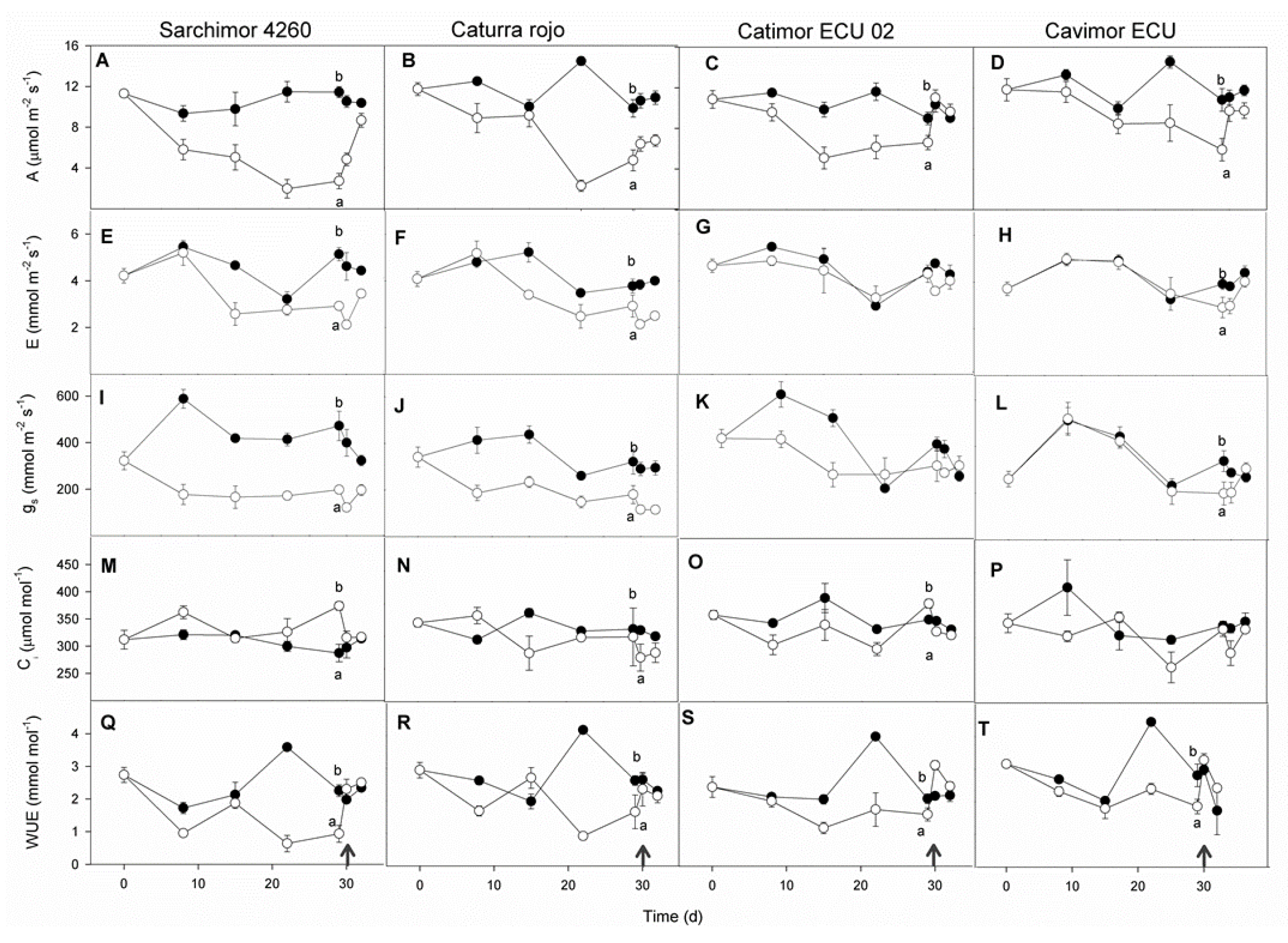

Figure 3.

Effects of water deficit duration on four coffee genotype plants' leaves: control (closed circles) and WD (open circles) plants. Net photosynthetic rate (A-D), transpiration rate (E-H), stomatal conductance (I-L), intercellular CO2 concentration (M-P), and water use efficiency (Q-T). Genotype name shown in the uppermost panels. The data are means (n = 5) ± SE. For each parameter at p < 0.05, distinct letters denote significant variations between WD and control seedlings. Measurements taken a day after re-irrigation are indicated by arrows.

Figure 3.

Effects of water deficit duration on four coffee genotype plants' leaves: control (closed circles) and WD (open circles) plants. Net photosynthetic rate (A-D), transpiration rate (E-H), stomatal conductance (I-L), intercellular CO2 concentration (M-P), and water use efficiency (Q-T). Genotype name shown in the uppermost panels. The data are means (n = 5) ± SE. For each parameter at p < 0.05, distinct letters denote significant variations between WD and control seedlings. Measurements taken a day after re-irrigation are indicated by arrows.

Figure 4.

The net photosynthetic rate (A) and stomata conductance (gs) of four genotypes of arabica coffee in the leaves of plants experiencing a water deficit (open circles) and control plants (closed circles) are correlated. The genotypes examined were Sarchimor 4260 (●), Red Caturra (■), Catimor ECU02 (▲) and Cavimor ECU (♦). The data are means (n = 5) ± SE. The regression was significant at p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

The net photosynthetic rate (A) and stomata conductance (gs) of four genotypes of arabica coffee in the leaves of plants experiencing a water deficit (open circles) and control plants (closed circles) are correlated. The genotypes examined were Sarchimor 4260 (●), Red Caturra (■), Catimor ECU02 (▲) and Cavimor ECU (♦). The data are means (n = 5) ± SE. The regression was significant at p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Effects of water deficit duration in parameters calculated from A/Ci curves on four coffee genotype plants' leaves: A, Ci-saturated photosynthetic rate; B, carboxylation efficiency; C, relative stomatal limitation; D, relative mesophyll limitation; E, maximum rate of electron transport through PSII ; F, maximum rate of RuBisCO carboxylation and G, triose phosphates utilization rate. The genotypes examined were Sarchimor 4260 (●), Red Caturra (■), Catimor ECU02 (▲) and Cavimor ECU (♦). When a value exceeds the symbol size, standard errors are presented. The data are means (n = 4) ± SE.

Figure 5.

Effects of water deficit duration in parameters calculated from A/Ci curves on four coffee genotype plants' leaves: A, Ci-saturated photosynthetic rate; B, carboxylation efficiency; C, relative stomatal limitation; D, relative mesophyll limitation; E, maximum rate of electron transport through PSII ; F, maximum rate of RuBisCO carboxylation and G, triose phosphates utilization rate. The genotypes examined were Sarchimor 4260 (●), Red Caturra (■), Catimor ECU02 (▲) and Cavimor ECU (♦). When a value exceeds the symbol size, standard errors are presented. The data are means (n = 4) ± SE.

Figure 6.

Changes over time of growth variables in plants of four arabica coffee genotypes in: A) height; B) flowering index; C) stem diameter; D) crown diameter; E) number of branches; F) branch length; G) total number of nodes per branch, and H) distance between internodes. Control plants measured on February (black bars), March (red bars), April (green bars), May (yellow bars), June (blue bars) and July (pink bars); plants under water deficit for 15 d (turquoise) and 29 d (grey). Cultivar names are indicated on the abscissa. An asterisk indicates significant differences between control plants in July and those subjected to water deficit (p< 0.05).

Figure 6.

Changes over time of growth variables in plants of four arabica coffee genotypes in: A) height; B) flowering index; C) stem diameter; D) crown diameter; E) number of branches; F) branch length; G) total number of nodes per branch, and H) distance between internodes. Control plants measured on February (black bars), March (red bars), April (green bars), May (yellow bars), June (blue bars) and July (pink bars); plants under water deficit for 15 d (turquoise) and 29 d (grey). Cultivar names are indicated on the abscissa. An asterisk indicates significant differences between control plants in July and those subjected to water deficit (p< 0.05).

Table 1.

Variations in the daily values of the following microclimatic parameters, which were measured inside the shade house on ten separate sample days: ambient CO2 concentration (Ca), photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), air temperature (Ta), relative humidity (RH) and air vapor pressure deficit (ΔW). Values are mean ± SE (n = 10 days).

Table 1.

Variations in the daily values of the following microclimatic parameters, which were measured inside the shade house on ten separate sample days: ambient CO2 concentration (Ca), photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), air temperature (Ta), relative humidity (RH) and air vapor pressure deficit (ΔW). Values are mean ± SE (n = 10 days).

| Hour of day |

Ca

(µmol mol-1) |

PPFD

(µmol m-2 s-1) |

Ta

(°C) |

RH

(%) |

Dw

(kPa) |

| 08:00 |

510 ± 24 |

30 ± 3 |

24.8 ± 0.4 |

82.8 ± 0.4 |

0.53 ± 0.02 |

| 13:00 |

414 ± 7 |

260 ± 70 |

33.1 ± 0.7 |

53.7 ± 0.7 |

2.3 ± 0.08 |

| 17:00 |

418 ± 5 |

50 ± 6 |

28.4 ± 0.6 |

66.2 ± 0.6 |

1.3 ± 0.05 |

Table 2.

In Esmeraldas, Ecuador assessed the genotypes of C. arabica, including their names, attributes, genetic origins, and responses to coffee rust.

Table 2.

In Esmeraldas, Ecuador assessed the genotypes of C. arabica, including their names, attributes, genetic origins, and responses to coffee rust.

| Name |

Traits and genetic origin |

| Sarchimor 4260 |

Sarchimor from CIFC based on the cross of Hybrid Villa Sarchi × Timor Hybrid. Various genetic lines of Sarchimor are being evaluated in Ecuador, and to date have excellent agronomic, productive and resistance to coffee rust. |

| Red Caturra |

Caturra are mutants of the coffee variety Bourbon, native to Brazil. This variety is considered to have a wide range of adaptability, high production, good agronomic and organoleptic characteristics, but susceptible to coffee rust. |

| Cavimor ECU |

Developed at the Coffee Rust Research Center (CIFC, Oeiras, Portugal) based on the crossing of Hybrid Catuaí × Catimor. Several Cavimor genetic lines currently being evaluated showed resistant to coffee rust. |

| Catimor ECU 02 |

The CIFC has developed the hybrid Catimor, the result of the cross between Caturra and Timor. This hybrid shows great genetic variability and resistance to coffee rust. |