1. Introduction

Water plays a crucial role in the reproductive process of Anura, as these amphibians are highly vulnerable to desiccation because of their skin permeability and reliance on humid environments. In addition, frog eggs are delicate and permeable, making water an essential component for their survival [

1]. The natural history of anurans delineates the evolution of diverse reproductive modes, ranging from aquatic to terrestrial, and even includes instances of reversion from terrestrial back to aquatic habitats. [

2,

3,

4]. In the transition of organisms from aquatic to terrestrial environments, the establishment of effective hydric regulation mechanisms assumes crucial importance in sustaining optimal water balance. These mechanisms encompass adaptations, including the modulation of egg layer quantity and size, production of foam to prevent dehydration, and a preference for reproductive activities in humid locales [

5]. Therefore, proper osmotic management is essential for successful reproductive modes [

6,

7].

It is known that the mechanisms responsible for water dependence and regulation are crucial for survival and reproductive success in offspring and female eggs [

8,

9,

10]. However, there is still little information available regarding the cellular physiology involved in the process of spermatogenesis, which contributes morphologically by producing viable spermatozoa. Understanding the intricate processes of spermatogenesis at the cellular level is essential for a comprehensive insight into reproductive biology. This involves not only the production of viable spermatozoa but also the regulation of their development, differentiation, and eventual function in fertilization.

The interaction between physiology and external factors modulates the reproductive cycles of frog species, as reported previously [

11,

12]. Factors such as temperature, humidity, and seasonal changes play significant roles in influencing reproductive patterns and success rates. Moreover, the specific dynamics of seasonal and local water availability dynamics are fundamental to the development of anuran species [

13,

14]. These dynamics can affect breeding sites, larval development, and adult survival, highlighting the importance of water as a critical resource. To fully grasp the complexity of anuran reproduction, it is necessary to understand the physiology of how anurans regulate and balance osmotic levels in their environment [

15]. This includes studying the osmoregulatory mechanisms that allow them to maintain homeostasis despite fluctuating external conditions.

Anuran survival heavily relies on the process of osmotic regulation, with aquaporins (AQPs) assuming a pivotal role in facilitating osmoregulation. AQPs participate in the management and control of water flux both inside and outside cells, thereby preserving the internal fluid balance of this taxonomic group [

15,

16,

17]. These proteins function by active transport and show different permeabilities to water and other metabolic molecules [

18,

19].

AQPs comprise a family of small “membrane-spanning” proteins, with monomers of 26 to 34kDa. These proteins are expressed in the plasma membranes of cells involved in fluid transportation. Proteins belonging to the aquaporin family are arranged as homotetramers in the membrane. Each monomer consists of six domains of “membrane-spanning” α-helix with carboxy and aminoterminal extremities oriented to the cytoplasm containing a distinct water pore acting as a water channel that facilitates and regulates the passage through the cell membrane [

20]. Aquaporins are present in the membrane of intracellular organelles, regulating the volume of both the organelles and the overall cell [

21]. AQPs are involved in many physiological functions such as water and solute homeostasis, secretion, facilitation of transepithelial transport, cellular migration, and neuroexcitation, and they also participate in a variety of pathological processes such as glaucoma, epilepsy, obesity, and cancer [

22,

23].

In the male genital system, water is necessary for maintaining the luminal environment where the spermatozoa are located. Water functions as a vehicle to transport these spermatozoa from the testis to the vas deferens, ensuring that they remain viable and capable of fertilization [

24]. The presence and proper functioning of water channels, such as AQPs, are crucial for this process. AQPs facilitate the movement of water across cell membranes, thereby maintaining the appropriate hydration levels within the reproductive ducts. Different types of aquaporin are expressed in specific regions or cells throughout the extra testicular ducts of mammals. Hermo & Smith (2011) [

24] reported that AQPs are located in specific membrane domains, including microvilli, apical, basal, and lateral regions of the cell as well as in endosomes. This strategic localization allows AQPs to efficiently regulate water transport and maintain the osmotic balance required for sperm maturation and mobility. The expression of these AQPs may be controlled by hormonal or luminal factors, indicating a complex regulatory mechanism that ensures optimal reproductive function.

The regulation of AQPs is a multifaceted process that can be influenced by both external and internal factors AQPs may also be regulated and influenced by external and internal factors such as variations in pH, phosphorylation, and auxiliary proteins [

20,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. There is evidence of a direct relationship between aquaporin differential expression and environmental water availability [

15,

31,

32]. These regulatory mechanisms are essential for adapting to changing physiological conditions and maintaining reproductive health.

The success of the biological process of anurans is intimately bound to the hydric dynamics, osmotic regulation, and physiological control of water flux through organs [

15,

16]. Evidence indicates that the dynamic of fluid concentrations between the internal and external mediums plays a fundamental role in biological processes as reproduction acts in the success of external fertilization, especially regarding the activation of sperm motility in frogs [

17,

27]. Considering this information, water is important in the dynamics of the male genital system, and water regulation in the testis by aquaporin is an essential process for sperm concentration [

33,

34] and consequential to male fertility [

35,

36].

In light of the pivotal role aquaporins play in water regulation in the male reproductive system [

19], and the lack of research on the expression of aquaporin across different animal groups and environmental context, particularly in anuran reproduction [

15], this study seeks to investigate the expression patterns of three distinct aquaporin proteins (AQP1, 2, and 9) in the testis of the neotropical anuran species

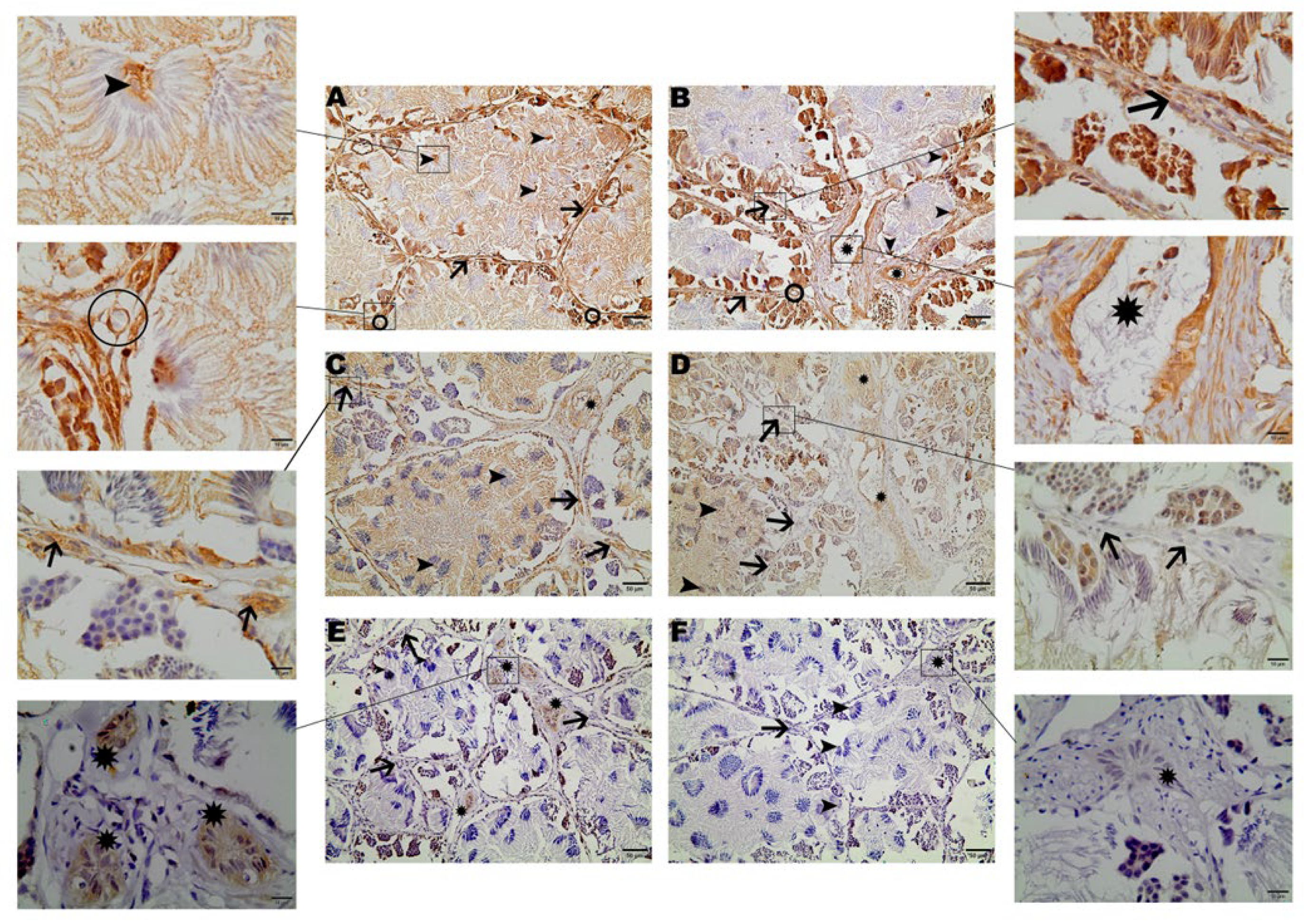

Leptodactylus podicipinus throughout its reproductive cycle. Therefore, this study aims to elucidate the localization of these proteins within testicular tissue and determine whether difference exist in the labeling of aquaporins throughout the species reproductive cycle.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Location

Animals were obtained from specific areas for the reproduction of species [

37,

38]. Rio Bonito (22°40′28.0”S;48°20′00.8” W) and Porto Said (22°40′49.1”S 48°19′37.0” W) both locations situated in the city of Botucatu state of São Paulo, Brazil.

The sampling was done through monthly expeditions during two years (2021 a 2023), totalizing 8 mature males separated into two groups (Reproductive, n=4; Non-reproductive, n=4). representing different periods of the species reproductive cycle. The location and capture of specimens were made through an active search at vocalization sites during the crepuscular period. The specimens used in the experiment were maintained according to the Ethical Principles of Animal Experimentation adopted by the Colégio Brasileiro de Experimentação Animal (CEUA Nº 4478221021), and all the expeditions and sampling were conducted with a sampling license (n°79953-3 SISBIO/IBAMA).

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

After euthanasia, the gonads were fixed for 24h by immersion in Tamponade Formalin 10% (90% PBS, 10% Formol), at room temperature. After fixation, they were submitted to inclusion in Paraplast (Sigma—Aldrich®), and 3 non-consecutive longitudinal sections were made per animal (3 µm thick, 50 µm distance between the sections).

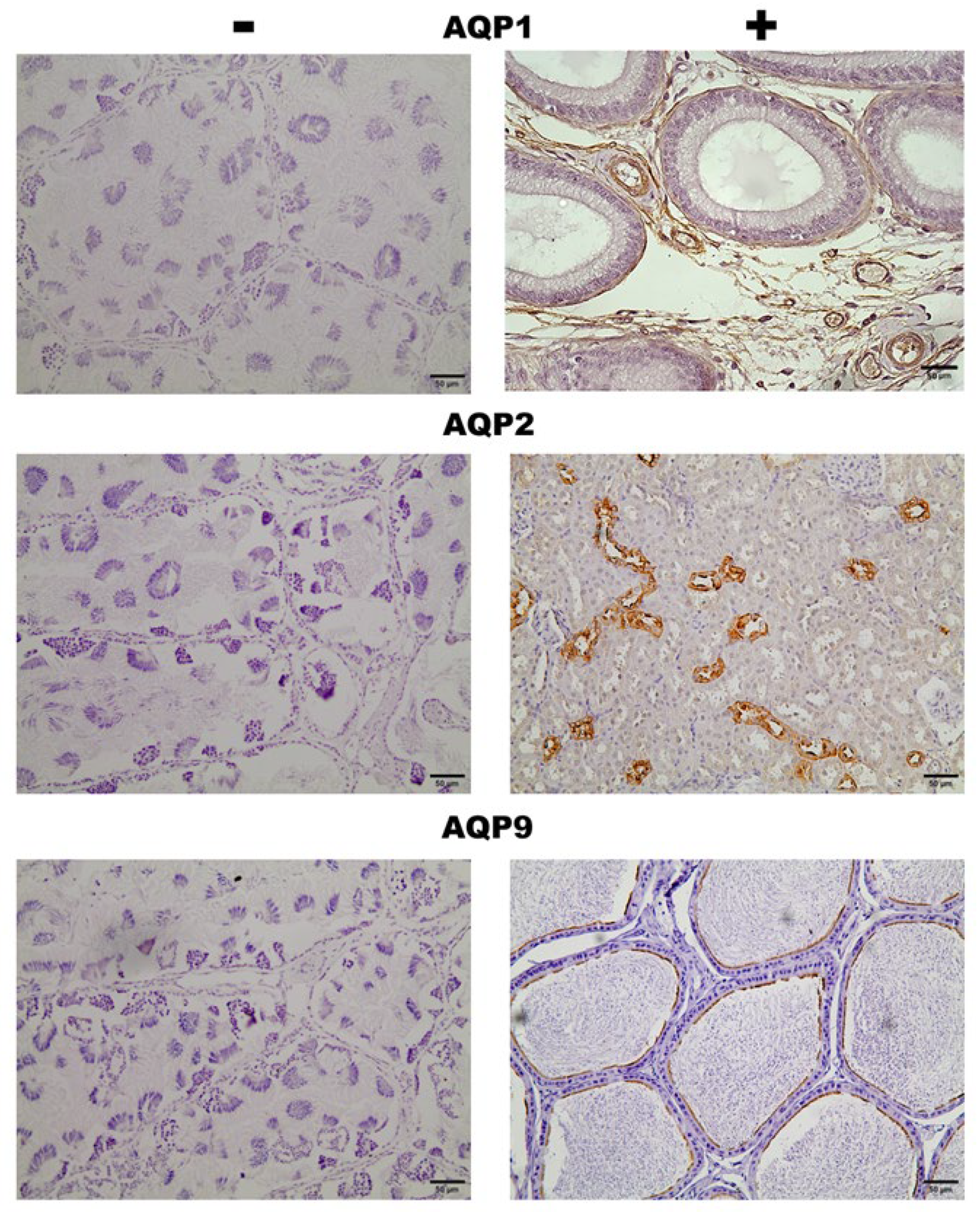

Histological slides of the testis were prepared, starting with deparaffinized in xylol followed by dehydrated in ethanol. Antigenic retrieval was performedsubjecting the slides toa immersion in tamponade citrate solution (pH 6.0) and subsequent exposure to a temperature of 100ºC for 15 minutes in a microwave (750W). To ensure optimal results, peroxidase blockade was performed in methanol solution containing 3% H2O2 for 15 minutes. To diminish the unspecific link, slides were incubated in a blocking solution comprising bovine serum albumin (BSA) at a concentration of 3% in PBS-T for 1 hour at room temperature. Following preparatory steps, the detections of AQP1, AQP2, and AQP9 was meticulously carried out using selected antibody dilutions at a concentration of 1:100 (Anti-AQP1 AB2219 Sigma-Aldrich; Anti-AQP2 AB3066 Sigma-Aldrich; Anti-Aqp9 AQP91-A Alpha Diagnostics) diluted in PBS, with overnight incubation at 4ºC. Subsequent to thorough washing with PBS, the slides were subjected to incubation with a secondary HRP antibody (Anti-rabbit IgG—1:100 AB6721 Abcam-USA) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by revelation using diaminobenzidine (DAB) and coloration with Mayer Hematoxilyn. Negative controls were made by substituting the primary antibody for 0,01M of PBS. Positive controls were employed to validate specific labeling, utilizing slides containing tissues from mouse and rat tissues (Appendix;

Figure S1).

Commercially available antibodies were used since aquaporin from anuran tissue presents a high homology to mammalian aquaporins (AQP1 60% similarity [

16,

39]; AQP2 70% similarity [

16,

40]).

Following immunohistochemistry, the slides were coded for blinded analysis. The evaluation of AQP1, 2 and 9 reaction results outcomes entailed meticulous comparison of reaction intensities across the two designated period groups. This analysis was conducted by Bordin and independently corroborated by Dr. Domeniconi to ensure rigor and reliability. Subsequently, the coded slides were examined under a light microscope Axiophot 2 equipped with a digital camera AxioCam HR (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) from the Department of Structural and Functional Biology, Anatomy sector, Biosciences Institute, UNESP—State University of São Paulo, Brazil.

2.3. Western Blotting

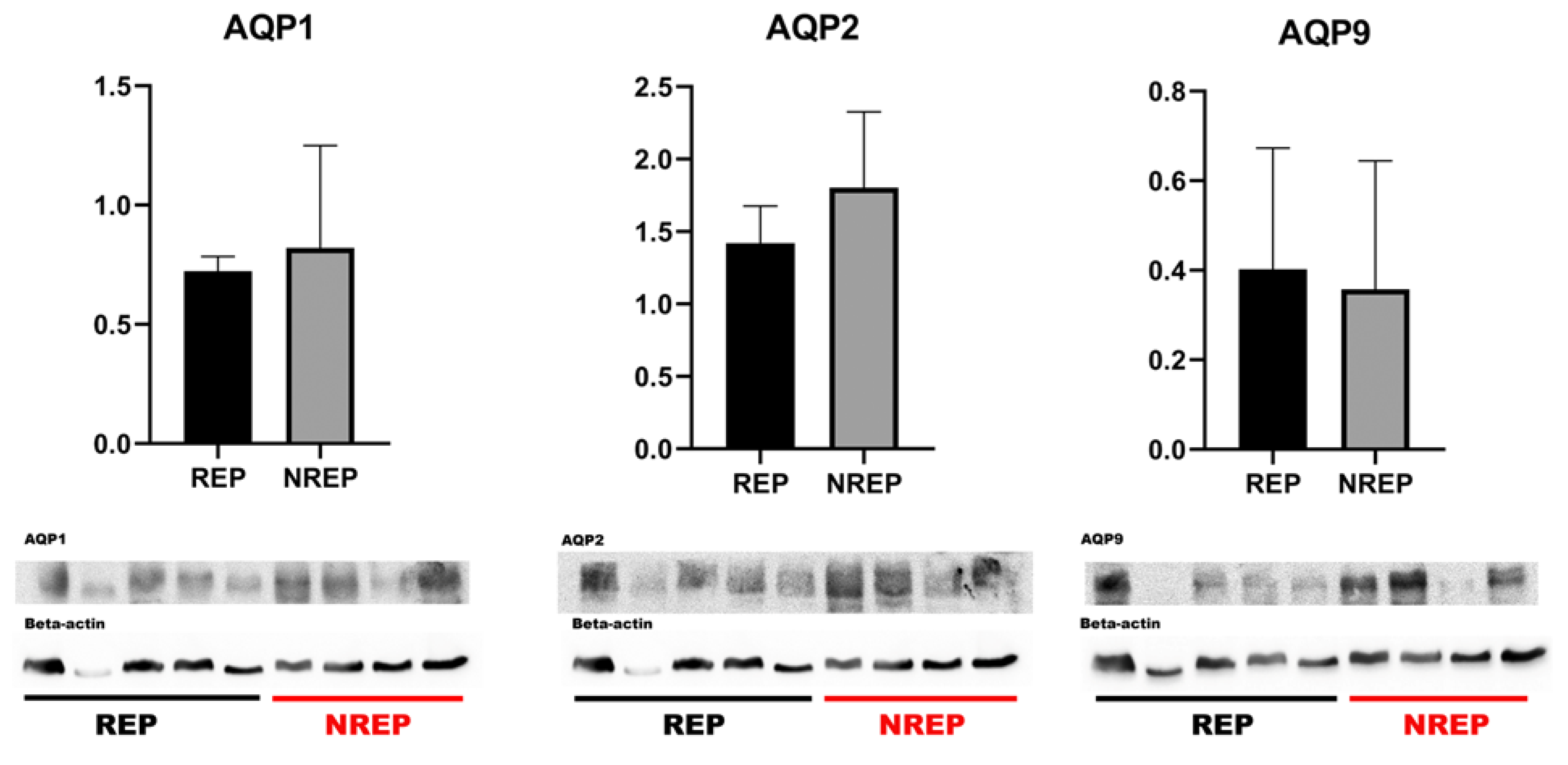

Frozen testicles were sampled and sonicated in a 50 mM TRIS buffer (pH 7.5) for 5 minutes, with a cycle of 1 minute per pulse at 40% amplitude while maintaining the temperature at 4°C. Following the sonication process, the material was centrifuged to separate the cellular debris, and the protein fraction was extracted from the resulting supernatant. The protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976). Subsequently, the protein samples were heated in a dry bath at 96°C for 15 minutes to denature the proteins. These samples were then loaded onto 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels for electrophoresis under reducing conditions. Post-electrophoresis, the separated protein bands were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Sigma). The membrane was blocked with 3% non-fat dry milk in TBST (comprising 10 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 hour to prevent non-specific binding. The blot was then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against AQP1 (AB2219, Sigma-aldrich), AQP2 (AB3066, Sigma-aldrich), or AQP9 (Aqp91-A, Alpha Diagnostic), each diluted at a ratio of 1:1,000 in 3% bovine serum albumin. Following this incubation, the blot membrane underwent a series of seven 5-minute washes with TBST to remove unbound antibodies. It was then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit-IgG secondary antibody (AB6721, Abcam). After a subsequent series of seven 5-minute washes in TBST, the proteins were visualized using an ECL prime detection reagent (Sigma). For quality control and to ensure equal loading, beta-actin was used as a positive control (Figure 2).

4. Discussion

In this study, we not only elucidate the immunolocalization of AQP1, AQP2, and AQP9 in anuran testicular tissue but also incorporate Western blotting analysis, thus providing a multifaceted approach to characterizing aquaporin expression in this context. It is noteworthy that, while the aquaporin family has been investigated across various zoological groups, including fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals [

31,

41,

42,

43,

44], our study makes a distinct contribution by integrating immunolocalization and Western blotting techniques to examine aquaporins in amphibian testes.

In the anuran specie

Dryophytes chrysoscelis, AQP1 was detected in the testis, expressed in the testicular tissue and Leydig cells but not in germ cells and ejaculated spermatozoa, indicating that AQP1 is related to support cells and testicular development but not closely associated with mature spermatozoa [

17]. In

L. podicipinus, the findings contrast to those for the

D. chrysoscelis, because in the

L. podicipinus AQP1 is closely linked to both germinative and testicular tissue, indicating its presence in both support and spermatogenic cells. The difference between the two species could be influence from factors such as climate and geographic location. Notably,

D. chrysoscelis, a temperate species, is encountered in North America (Canada and U.S), whereas

L. podicipinus, a tropical species, predominantly inhabits South America (Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay).

In the fish species

Sparus aurata, AQP1 appears to be specifically associated with early germ cells like spermatids and spermatozoa. Its involvement suggests a potential role in addressing the metabolic requirements during the advanced stage of the spermatogenic process [

44]. In this study, AQP1 was additionally found to be associated with germinative cells and strongly related to spermatozoa when compared with the other tested aquaporins. These observations support the hypothesis that AQP1 plays a pivotal role in the metabolic process of spermatogenesis, particularly in spermiogenesis. Additionally, the strong labeling of AQP1 observed in the spermatozoa from the reproductive group indicates its potential involvement in sperm maturation and motility.

Aquaporins present varied characteristics denoting conservation and variation across the zoological groups, in goose testis AQP1 is expressed in testicular blood vessels but not in Leydig cells [

43]. In the tested anuran species, AQP1 is present in both the testicular blood vessels and Leydig cells, underscoring the conservation of AQP1’s role in blood regulation. However, there is variation in its expression in anuran Leydig cells, as it was not detected in birds.

Regarding AQP2, this aquaporin has been described in turkey reproductive ducts and is considered to be involved in the maturation of avian spermatozoa [

45]. Similar to birds, in

L. podicipinus, AQP2 is present in spermatozoa; however, AQP1 seems to play a more significant role in the maturation process. This is evidenced by its strong labeling observed in both early and late germ cells, as well as in supporting cells such as Sertoli, along with the absence of labeling in sperm from the non-reproductive periods. These findings suggest that AQP1 in anurans may serve as a marker for the final stage of sperm maturation.

Despite the stronger association of AQP1 with germ line cells, AQP2 was exclusively found in the Leydig cells only in animals from the reproductive group. This result may be attributed to a seasonality factor, once vasotocin, a peptide homologous to vasopressin in mammals, is known to regulate AQP2 expression in anurans [

39,

41,

46]. In addition to its involvement in various reproductive activities such as vocalization, amplexus, and male agonistic behavior, vasotocin exhibits a seasonal variation, predominantly expressed during the reproductive period of anurans varying with steroid sex hormone levels that are regulated by supporting cells such as Leydig cells [

46,

47]. The finding of AQP2 labeling Leydig cells only in individuals of reproductive period supports the notion that vasotocin may be associated with AQP2 regulation in the reproductive tract of anurans, suggesting a potential association with the seasonal behavior of AQP2 throughout the reproductive cycle of these amphibians.

AQP9 was detected in the interstitial tissue of

S. aurata testis, specifically in Leydig cells [

44]. However, the function of this aquaporin regarding the Leydig cells remains unknown. In contrast, in the

L. podicipinus testis, AQP9 was found only on the intratesticular ducts, with no presence observed in interstitial tissue or germ cells. This suggests that AQP9 may be more closely associated with the transport of spermatozoa rather than participating in their maturation process. Specifically, the majority of AQP9 labeling in

L. podicipinus testis was found in animals from the reproductive period indicating that the function and localization of AQP9 may be closely related to the transportation and regulation of mature spermatozoa, as seen in the reproductive tract of mammals, where it is found in the epididymis of rodents and carnivores [

19,

42].

The localization of proteins is crucial for their function, especially in dynamically regulated processes such as reproduction. Our immunohistochemical observations indicate that the localization of aquaporins changes during the reproductive cycle. This suggests that aquaporins play specific and contextual roles in reproductive physiology, with high expression in critical locations during reproductive periods. The differential localization of these proteins can offer valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms regulating reproduction in anuran species, aiding in hypothesis formulation and guiding future research in this area.

The Western blot results for the studied aquaporins showed bands at 29-30 kDa, which align closely with existing results in the literature. In the species

D. chrysoscelis, AQP1-type aquaporin was reported at 26 kDa [

17], slightly lower than the results observed in

L. podicipinus. For

Hyla japonica, an AQP2-type aquaporin was described in urinary bladder tissue with bands at 30-31 kDa, similar to findings in

Rana catesbeiana,

R. nigromaculata, and

Bufo japonicus [

39,

48]. The observed variations in the molecular weights of the aquaporins may arise from differences in amino acid sequences, post-translational modifications, or tissue-specific isoforms. Additionally, there is limited data describing the characteristics of AQP9 in anurans. While the molecular weights of aquaporins provide valuable insights into their structural features, comprehensive studies encompassing functional assays, protein interactions, and expression patterns are necessary to unravel the complexities of AQP biology across different species and tissues.

The comparison between two different periods regarding the protein levels of AQP1, AQP2, and AQP9 in the Western blotting analysis yielded no significant differences. Western blotting measures global protein levels in tissue samples, potentially diluting local variations in expression that are more clearly visible with immunohistochemistry. Furtheremore, aquaporin expression may be regulated post-translationally, affecting their localization and functionality without altering the total levels detectable by Western blotting.

The protein levels obtained from blot analysis showed no different value of AQP1 and AQP2 in animals from the non-reproductive period, which aligns with the immunohistochemical labeling results of spermatozoa and Leydig cells, as there are no statistical differences. The immunohistochemical differences were specific to certain cells, not the entire tissue. Since the labeling was predominantly found in other cells, the quantification of these aquaporins between the stages of reproduction could be related to the water conservation function rather than their reproductive and hormonal function, as these two functions are not mutually exclusive.

The aquaporin family in anurans has a long history of studies since the first hypothesis related to the cellular water channels [

16]. The present molecular result contribute to the report of diversity in aquaporin characteristics in the anuran group, comparing the AQPs molecular weight of

L. podicipinus with other species such as the HC-1 and AQPh2 from

D. chrysoscelis and

H. japonica. This diversity is also related to the range of environmental behavior within the group, reflected in physiological mechanisms such as water balance via aquaporins influenced by environmental or hormonal factors [

16]. This is evident in the thermal-specific expression of

D. chrysoscelis HC-1 and HC-3 in osmoregulation organs [

16,

40]. Conversely, in

L. podicipinus testicles, there is no significant difference in the quantity of AQP expression between periods, despite tissue expression variation. Although the organs are from different systems, the lack of variation in

L. podicipinus may reflect the stable and tropical environment that the individuals inhabit.

Furthermore, extended research and testing are necessary to determine whether the difference is only related to the localization of the aquaporins or if there is indeed a differential expression of these proteins throughout the reproductive cycle of the species.

5. Conclusions

The present study marks the first description of the localization of AQP1, AQP2, and AQP9 in the testis of an anuran species. Although there were no statistical differences in the western blot results between the two periods, our qualitative diagnosis and comparison of the immunohistochemical images from the two groups reveal a difference in the localization of these aquaporins throughout the reproductive cycle of the species studied, indicating that the physiological changes occurring in the anuran reproductive tract during the cycle could affect the expression of AQPs. This is evidenced by the strong labeling of AQP1, AQP2, and AQP9 in spermatozoa, Leydig cells, and intratesticular ducts respectively, during the reproductive period, contrasted with the absence of labeling in non-reproductive animals. While variation exists between different animal groups, comparisons also reveal similarities, aiding in the formulation of hypotheses and guiding the elucidation of the roles of these proteins in various tissues and systems.

In conclusion, reproduction is an important and complex aspect of animal life, and delving into the reproductive dynamics of species, particularly anurans, holds immense value given the group’s variability. However, much remains unclear regarding the cellular and physiological roles of aquaporin in anuran reproduction. It is evident that further research is imperative to unravel and enhance our scientific understanding in this area.