Introduction

Surfing is a high participation and growth sport. In Australia, across the 2000’s surfing participation had a growth rate of 24% year-on-year1 and it has been reported that between 2019 to 2021 196,000 new participants registered with formal surfing clubs2. Furthermore, from 2016 to 2023 there was a surfing population increase of 46% amongst people aged 18 years or older3. Currently, in Australia, it ranks as one of the top five nature-based recreations for popularity and it is believed nearly 730,000 adults engage in surfing, spending nearly $3 billion annually. These numbers are likely to mirror world-wide numbers where it is thought that more than 50 million people engage in surf sports3, however this likely under-represents actual participation because it is a sport that men and women of all ages can participate in without engaging in organized events1, 3. Despite the popularity or the sport, relatively little research exists surrounding performance in surfing. This is particularly surprising given surfing’s inclusion as an Olympic Sport from the 2020 Tokyo Olympics onwards. Surfing is one of few sports which requires physical acts both above and below water; with padding through water, surfing on water, and disembarking board and duck diving under water all being required. As such, data is needed to observe if other sport knowledge translates to surfing. Given the nature of the sport, aspects of warm-up and maintenance of body temperature presents itself as of interest.

Both water and wind factors affect body temperature, however most research exploring how these elements affect body temperature has been undertaken in swimmers or divers4-7 and a small amount with water skiers8. Heat loss, and heat perception, is individual in nature and it is known that for most humans water can start to markedly cool the body at 20 degrees Celsius and below9. Wetsuits, which are often used by surfers, are thought to ameliorate the rate of cooling; and this is supported by a small amount of research conducted with surfers which showed that a 2 mm wetsuit can prevent most heat loss for short periods in water temperature of 15 degrees Celsius or greater10, 11. However, as wave quality and availability is often better in winter, surfers will often encounter combined chill factors well below 15 degrees Celsius. Therefore, more comprehensive, and ecologically valid data examining heat attainment and retention in surfing would be useful.

From a performance perspective, core, and correspondingly muscle temperature, has an important sport performance related effect - namely increasing potential power generation capacity in muscles12-14 and potentially reducing injury risk15. For sports with relatively high muscular power demands, and in conditions where maintenance of that elevation is challenged by environment, structuring warm-ups to include muscle temperature elevation and combining passive heat retention mechanisms to retain that heat until competition start has proved a highly successful performance strategy16-20. Even in sports where hot and humid environments may better be prepared for by pre-cooling, combinations of muscle warmth and core cooling facilitate enhanced overall performance compared to pre-cooling or warming alone21. In surfing competition, one of the key judging criteria is demonstration of power on the wave and evidence shows that land based tested strength and power increase with elite performance22, 23. Surfing is also a timed sport, and common strategy often involves obtaining several early wave scores (best two wave score combination wins). Therefore, having added core and muscle temperature, and potentially better early generation of muscle power, poses as a useful attribute. In free surfing where no judgement is applied participants want to pop-up cleanly onto waves, catch as many good waves as possible and often spend maximum time on waves performing manoeuvres, all these likely have power contributors. In addition, in free surfing reducing participation injury is a worthy goal and muscle heat may offer some amelioration to risk15.

The aims of this study were 1) to explore the thermal profile of surfers across the duration of a surfing session, in cold water, which would be similar in length to a competition with and without a structured warm-up combined with passive heat retention, and 2) to explore any relationships to free surfing performance (surfing in which strict competition criteria have not been requested). We hypothesised that the warm-up and heat retention strategy would elevate core body temperature enabling surfers to enter the water warmer and potentially sustain a higher core body temperature throughout the session. Furthermore, we hypothesised that performance following the warm-up would be enhanced on waves early in the session when warm-up temperature effects were potentially more marked.

Study Overview

This research adopted a repeated measures pre- and post- design with randomized crossover treatment. Participants attended an artificial wave pool (UBRN Surf, Victoria, Australia) on several occasions – once for familiarization, once under experimental conditions, and once for ‘control’ conditions. For the ‘experimental’ surf, participants entered the wave pool following a combined active and passive warm-up; for control they entered the pool without completing a warm-up; therefore, participants acted as their own control. For both control and experimental conditions participants swallowed a thermometer pill (BMedical, Paris, France) and core body temperature was measured every 30-seconds for the duration of data collection. For a subset of participants, performance on their first two waves and their tenth wave was scored under both experimental and control conditions by two Australian State level qualified surfing judges (though they were not told they were being scored and they were free surfing). Consequently, core body temperature under experimental conditions was compared to core body temperature under control conditions for all participants; and performance, using scoring criteria, was also compared between conditions but for a subset of participants only.

Participants

Thirty-four participants (n = 20 males; n = 14 females) were recruited to this study. The mean (± SD) age, height and weight for the male participants was 25.8 ± 10.6 years, 176.8 ± 7.5 cm, and 71.6 ± 10.2 kg respectively, and for females it was 34.9 ± 11.4 years, 167.1 ± 6.1 cm, and 60.7 ± 4.4 kg respectively. All participants ranged from advanced surfers (i.e., they were capable of executing aerial maneuvers, and competitive at state level in Australia) down to intermediate level recreational surfers (i.e., could execute maneuvers considered one to two ‘levels’ down from advanced). Fourteen of the surfers were goofy footed (i.e., they stood on a surfboard with right foot forward), and 20 surfed with a natural stance (i.e., they stood on a surfboard with left foot forward). The subset of participants who were scored by the qualified judges (n = 19) were all advanced level surfers. Of the subset of participants, 15 were male, four were female, nine were goofy footed, and ten were natural. The mean (± SD) age, height, and weight for the males in subset of the sample was 20.0 ± 6.8 years, 176.1 ± 7.7 cm, and 67.9 ± 9.1 kg respectively, and for the females in this subset of the sample it was 32.4 ± 14.2 years, 164.5 ± 5.3 cm, and 60.0 ± 0.1 kg respectively.

Procedures

Approval to conduct this research was granted by the University of New England Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol number HE22-141). Prior to commencement of data collection voluntary informed consent to participate was provided by each participant following briefing of the research aims and protocols.

For familiarization, participants surfed at the artificial wave pool in their own time prior to commencement of the experiment. Thereafter, on two separate occasions, at least 24 hours apart, but no more than 72 hours apart, participants attended the wave pool at approximately 7:00 am and swallowed an activated thermometer pill. On the control day participants were instructed to prepare for a surf as they normally would and entered the pool at 9:00am. On the experimental day, at 8:20 am participants commenced a land-based warm-up in their wetsuits before covering themselves with a survival blanket until they were entered the wave pool at 9:00am. Survival blankets are low-weight, low bulk blankets made of thin plastic heat-reflective sheeting. The warm-up was similar to that described elsewhere

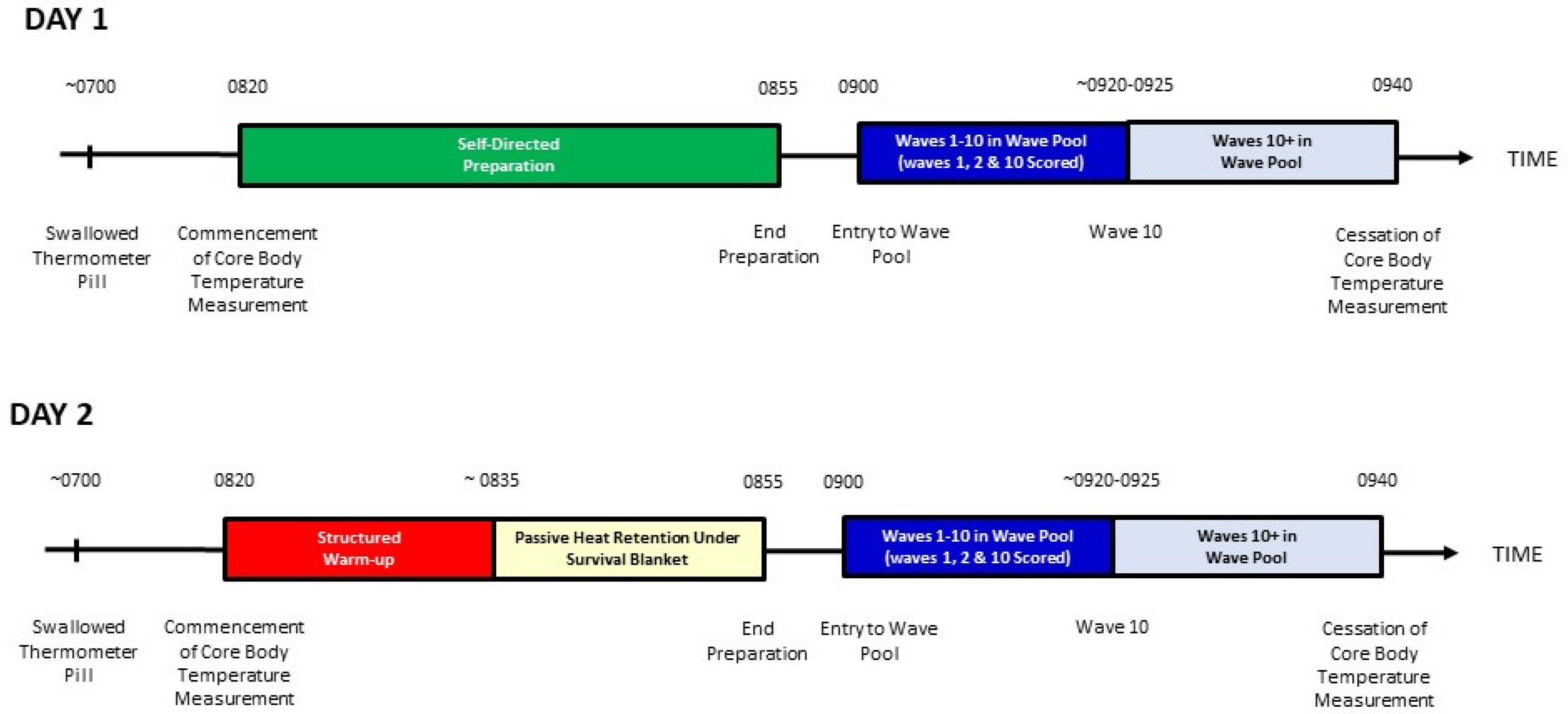

24, and thus consisted of 2-5 minutes of general mobility, 2-3 minutes of upper body and lower body reactive strength exercises, 2-3 minutes of upper body and lower body elastic strength exercises, and 2-3 minutes of upper body and lower body mechanical power exercises. The warm-up took 12-15 minutes, therefore participants remained under survival blankets, remaining reasonably still, for 15-20 minutes. The order of days whereby participants undertook a land-based warm-up prior to entering the wave pool vs. preparing as they normally would was randomized per participant. The wave pool water temperature was 13 degrees Celsius, and participants wore full length arm and leg wetsuits of at least 2 mm neoprene foam thickness. They were also instructed to wear the same wetsuit on both occassions. Core body temperature was analyzed from 8:20am to 9:40am on both experimental and control days, and data was compared. A schematic of the research protocol can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of research protocol. Note, whether participants completed session 1 or session 2 first was randomized. Both sessions were completed greater than 24 hours between each other, but no more than 72 hours.

Figure 1.

Schematic of research protocol. Note, whether participants completed session 1 or session 2 first was randomized. Both sessions were completed greater than 24 hours between each other, but no more than 72 hours.

Core Temperature Measurement

Thermometer pills were activated prior to ingestions using and eCelsius Performance Activator (BMedical, Paris, France) and swallowed by participants between 90 and 60-minutes prior to commencing the warm-up. Participants were instructed to not consume and drinks between swallowing the pill and entering the pool to not affect core temperature readings while the pill was in their stomach. All temperature readings were transferred wirelessly from participants soon after completion of the surf using and eCelcsius Performance Monitor (BMedical, Paris, France) and downloaded to ePerformance Manager (BMedical, Paris, France) and exported to Microsoft Excel for later analysis.

Statistical Analysis

A linear mixed model with the dependent variable being temperature change from baseline (i.e., start of warm-up), considering time (i.e., end of active warm-up, end of passive warm-up, wave pool entry, approximate time for wave 10, and end of session) and condition (i.e., control, warm-up) as fixed effects, and the participant as a random effect.

For the subset of participants’ whose data was analyzed for performance, descriptive data was initially explored. Thereafter, given data was somewhat categorical in nature, non-parametric statistical analysis was performed to establish whether a difference for any scoring variables where present for entry score, maneuver scores, and overall scores using a Friedman’s test. Where a significant difference was indicated, separate Wilcoxon’s were performed on all possible combinations to establish where the significant differences exist.

Results

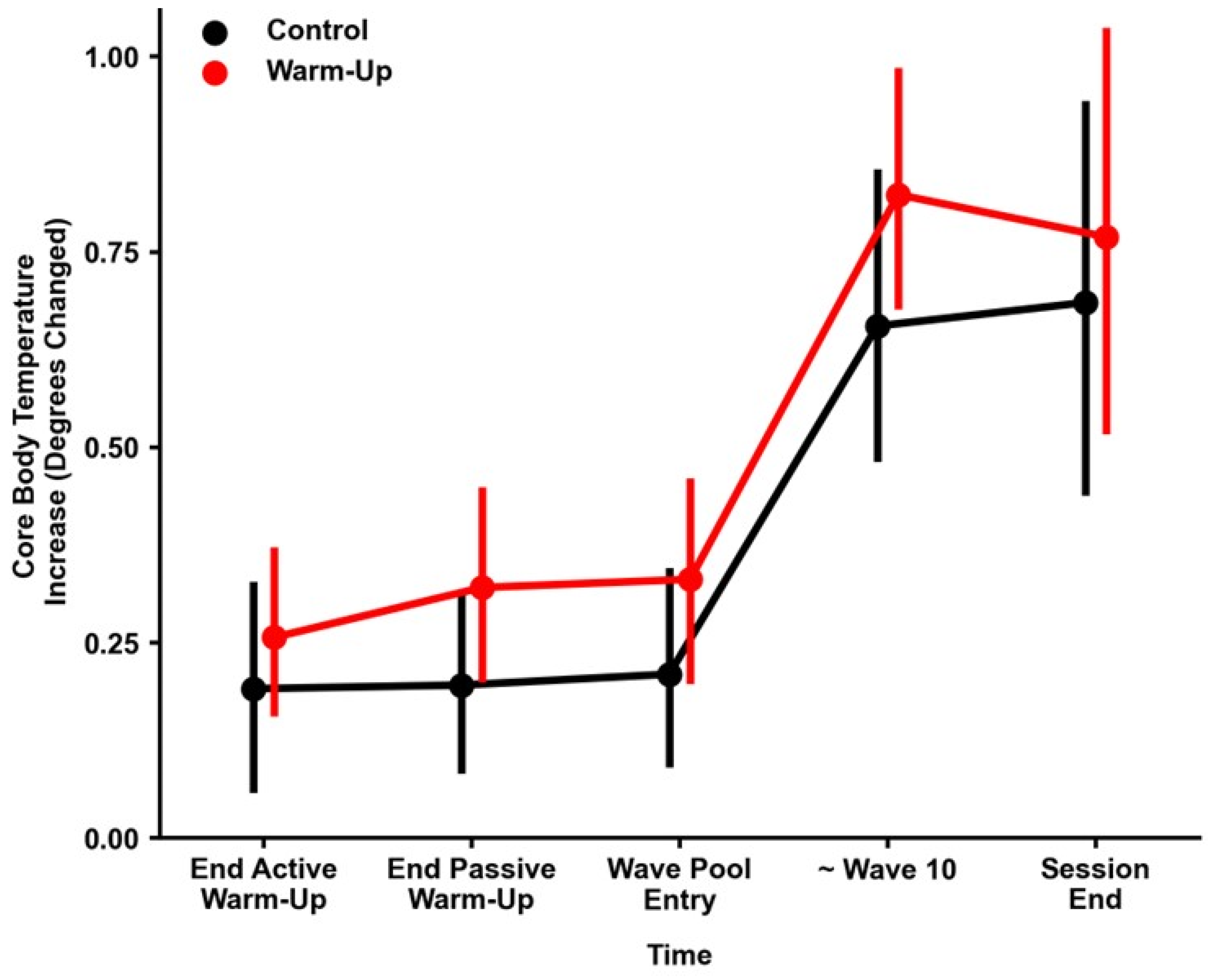

The overall performance for the model exploring core body temperature as per R-squared was 0.55. Statistically significant main effects were present for time (p < 0.001) and condition (p = 0.006), but no statistically significant interaction effects were present for time and condition. Post-hoc analysis revealed a main effect for condition where control had a lower temperature change compared to warm-up as an effect across entire surfing session (p = 0.006). For the main effect of time, there were statistically significant temperature changes between the end of the active warm up, end of passive warm-up and wave pool entry to the approximate time of wave 10 and the end of the session (see figure 2).

For scoring metrics, as can be seen in table 1, descriptive statistics reveal less people execute maneuvers on later waves, and it appeared that participants were less likely to complete as many maneuvers as possible on later waves. Furthermore, the Friedman test showed a significant difference for ‘entry score’ (χ

2(3) = 7.96,

p = 0.04). Wilcoxon analyses revealed that entry score under warm up conditions for wave two was better than wave10 under warm-up conditions (

Z = 2.11,

p = 0.03), although wave 10 was not significantly different across treatments. Interestingly, entry score for wave two under was better under warm-up conditions (

Z = 2.30,

p = 0.02). No other statistically significant observations were made, although trends as in table 1 suggest a slight favorability across all criteria in the warm-up condition.

Figure 2.

Mean core body temperature over time under control conditions vs. warm up conditions. Values are mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Mean core body temperature over time under control conditions vs. warm up conditions. Values are mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this work was to explore core body temperature changes in surfers with and without a structured warm-up combined with a passive heat retention strategy (wrapping post active warm-up in a survival blanket). Secondary to this, in a subset of participants who were advanced surfers, we examined whether warm-up influenced performance criteria across free surfing. Our results showed a clear thermal advantage to undertaking an active warm-up combined with passive heat retention strategy prior to surfing. Specifically, we saw that the warm-up protocol resulted in consistently high core body temperature changes compared to baseline versus control conditions. Furthermore, this was maintained across the entire pool session. Across the session both treatments showed warming-up further, a product of paddling and surfing likely combined with the effects of a wetsuit

26, 27. A well-designed

Table 1.

Summary of surfing performance with or without a structured active warm-up with passive heating. Total number of participants = 19.

Table 1.

Summary of surfing performance with or without a structured active warm-up with passive heating. Total number of participants = 19.

| |

Wave 1

(median ± IQR)* |

Wave 2

(median ± IQR)* |

Wave 10

(median ± IQR)* |

| Number of Participants Who Popped-Up Onto the Wave |

|

|

|

| |

Warm-Up |

19 |

19 |

19 |

| |

No Warm-Up |

18 |

19 |

17 |

| Entry Score |

|

|

|

| |

Warm-Up |

|

3.0 ± 0.5 |

2.0 ± 1.0†‡

|

| |

No Warm-Up |

|

3.0 ± 1.0 |

2.0 ± 2.0 |

| Number of Participants Who Executed One Manoeuvre on The Wave |

|

|

|

| |

Warm-Up |

|

19 |

17 |

| |

No Warm-Up |

|

18 |

12 |

| Score for First Manoeuvre |

|

|

|

| |

Warm-Up |

|

3.0 ± 1.0 |

2.0 ± 1.0 |

| |

No Warm-Up |

|

3.0 ± 2.0 |

2.0 ± 1.0 |

| Number of Participants Who Executed Two Manoeuvres on The Wave |

|

|

|

| |

Warm-Up |

|

14 |

9 |

| |

No Warm-Up |

|

13 |

7 |

| Score for Second Manoeuvre |

|

|

|

| |

Warm-Up |

|

3.5 ± 2.5 |

2.0 ± 1.0 |

| |

No Warm-Up |

|

3.0 ± 3.0 |

3.0 ± 1.0 |

| Number of Participants Who Executed Three Manoeuvres on the Wave |

|

|

|

| |

Warm-Up |

|

8 |

6 |

| |

No Warm-Up |

|

7 |

0 |

| Score for Third Manoeuvre |

|

|

|

| |

Warm-Up |

|

3.5 ± 2.0 |

2.5 ± 2.5 |

| |

No Warm-Up |

|

2.0 ± 2.5 |

n/a |

| Overall Score |

|

|

|

| |

Warm-Up |

|

4.0 ± 3.0 |

3.0 ± 1.0 |

| |

No Warm-Up |

|

3.0 ± 2.0 |

3.0 ± 2.0 |

wetsuit with combination of 3/2mm thickness (i.e., chest and back panels of wetsuit made of 3 mm neoprene foam, whereas limb panels are made of a 2 mm neoprene foam) will almost certainly facilitate heat retention. Finally, and secondary to the thermal effect, our data suggests performance in free surfing may be slightly enhanced following the warm-up.

Free surfing is characterized by the surfer’s freedom to choose maneuvers, length of ride, taking risk, having fun etc., and not be bound to any scoring criteria. However, it is possible to characterize each ride using standard performance criteria with the expectation that lower scores may be observed (participants are less concerned in trying to achieve standardized criteria). Hence, we utilized standard surfing Australia judging criteria applied by two independent blinded judges to observe if any performance data trends emerged. At a descriptive level across all criteria, post-warmup waves scored slightly higher. In particular, pop-ups were more likely and entry score, of the pop-up, on wave two was higher as were the number of maneuvers following warm-up. In addition, variation across performance scores following warm-up was less than in control (i.e., interquartile range was lower under warm-up conditions versus control). Wave ten performance was slightly less than wave two, possibly reflecting some fatigue. Certainly catching nine waves in 20 minutes is likely to have been physically challenging. In “free” surfing, surfers will often go longer on waves past the point where they get best scores so fatigue may have been more than would have been observed in a directed competitive scored situation. Speculation is difficult given the open end of what surfers perceive in free surfing, however the results tantalizing suggest that warm-up did affect aspects of performance early in the surf session. This is consistent with other data around performance effects of warm-up16, 21, 28. The lack of clear effect by wave ten does not negate this potential benefit as the warm-up treatment was not in any-way penalized relative to the control treatment. Is it unknown if injury risk was reduced, however as warmth has been suggested as ameliorating risk in land-based sport15, this may be an additional potential benefit.

An extension of this work would be the converse research in a very hot and humid environment where surfing can also often occur; in other sports previous work has suggested precooling to be beneficial to performance mainly due to reducing endurance fatigue29. However, in sports involving a benefit from early power availability the innovative combination of both warming (legs) and cooling torso may offer benefits that exceed either treatment alone21, something worthy of further surf performance research. Thus, the results from this study are certainly provocative to suggest further work should be undertaken under surfing competition conditions where surfers are under onus to perform to judged criteria. Moreso the results speculatively suggest even in recreational free surfing there may be advantages to the warm-up protocols in terms of ability to catch waves, stay on waves and get more manoeuvres (likely equating to more fun, a major goal of free recreational surfers).

Numerous other studies have shown the use of passive heat maintenance, such as survival blankets, can maintain and even add to body heat from active warm-ups16, 30, 31; and data herein supports the same in surfing. Often warm up needs to be time separated from actual competition start and in surfing anecdotally it is popular to sit and analyse waves immediately before water entry. The addition of a passive warming technology from our study appears ideal to assist in heat maintenance under such conditions. However, it is worth noting that thermal comfort and individual perception is another interesting factor which can influence clothing choice; for example, research has showed synthetic garments enhance comfort, thermoregulatory it sense can sometimes trump performance based choices in terms of adoption of a practice32-34. As such, factors other than performance gains may influence likelihood of uptake of passive heating strategies. In terms of the outcomes speculated for free surfing and recreational surf markets clothing designs incorporating comfort, fashion and appropriately designed and tested warmth retention may be useful.

While this study produced some interesting findings, the results should not be considered without their limitations. The main being that thermometer pills were swallowed relatively soon to when experimental measurement started. Research suggests that thermometer pills should be swallowed near six hours prior to experimental measurement so they can lodge in the intestines, not stomach, and not be subject to rapid changes of temperature due to consumption of food and drink35. However, recent work has shown that, if unaffected by such confounding factors, then thermometer pills can still accurately measure core body temperature35. Another limitation was the scoring method adopted for overall score applied to a free surfing format; given overall score considered performance across the whole wave, and not all participants complete three maneuvers on each wave, a person who only complete one maneuver, for example, may have scored disproportionately high or disproportionately low. Whereas a participant who complete three maneuvers on each wave is likely to have been scored more accurately, and achieving more scoreable maneuvers would be something surfer would aim for in a competitive scenario (as opposed to maximum fun in free surfing). Nonetheless, it should be noted that for participants who execute two or more maneuvers on each wave, no statistically significant difference in performance between maneuver one, maneuver two and maneuver three was typically observed; as such, scoring and performance was likely reasonably robust, and it may still be argued that some interesting trends were observed. It should also be noted that, despite them being lower after warm-up versus control, the relatively high interquartile ranges suggest some may have been ‘better’ responses to the warm-up intervention than others. Across our sample we had both gender and broad BMI differences. We did not attempt to tease these out as our study was focused on a broad sample effect, but obviously doing so in a further study could be insightful. Finally, it should be acknowledged that the frequency of waves was far greater than what would we be expected in real world environment. However, our arguments would largely be unaffected by this.

Conclusion

A land-based active warm-up combined with passive heat retention (e.g., being wrapped in a survival blanket) has a clear benefit to heat attainment and retention in surfers. Furthermore, our results suggest that surfing performance may be enhanced by this protocol; and, speculatively, injury risk may decline. The outcomes of this study has implications for surfing performance in recreational and competitive settings, as well as product design (i.e., land-worn heat retaining garments, wetsuit etc.).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.J.C. and B.G.S.; Methodology, C.J.C., B.G.S., L.J.H., and A.F.; Formal Analysis, B.G.S. and A.F.; Investigation, C.J.C., B.G.S. and L.J.H.; Resources, C.J.C., B.G.S., L.J.H and P.J.F.; Data Curation, C.J.C., B.G.S., and L.J.H.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, C.J.C. and B.G.S.; Writing – Review & Editing, C.J.C., B.G.S., L.J.H., A.F., and P.J.F.; Project Administration, C.J.C., B.G.S, L.J.H. and P.J.F.; Funding Acquisition, C.J.C.

Funding

Partial funding for this project was awarded by the University of New England Academic Pursuit Fund for C.J.C.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of New England Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol number HE22-141, October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study is not publicly available due to guidelines from the approving institutional review board.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the participants for donating their time to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Australian Sports Commission. Surfing State of Play Report: Driving Participation & Engagement; Australian Sports Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Sports Commissions. Ausplay Focus; Australian Sports Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Manero, A.; Yussof, A.; Lane, M.; Verreydt, K. A national assessment of the economic wellbeing impacts of recreational surfing in Australia. Marine Policy 2024, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardy, E.; Mollendorf, J.; Pendergast, D. Active heating/cooling requirements for divers in water at varying temperatures. In 2007 ASME-JSME Thermal Engineering Summer Heat Transfer Conference, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 2007.

- Hall, J.; Lomax, M.; Massey, H.; Tipton, M. Thermal response of triathletes to 14C swim wth and without wetsuits. In 15th International Conference on Environmental Ergonomics (ICEE XV), 2015.

- Hayward, J.S.; Eckerson, J.D.; Collis, M.L. Thermal balance and survival time prediction of man in cold water. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1975, 53, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melau, J.; Mathiassen, M.; Stensrud, T.; Tipton, M.; Hisdal, J. Core Temperature in Triathletes during Swimming with Wetsuit in 10 degrees C Cold Water. Sports (Basel) 2019, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, N. Slalom water skiing: Physiological considerations and specific conditioning. Strength and Conditioning Journal 2007, 29, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.; Ferreira, P.H.; Micheletti, J.K.; Almeida, A.C.L.I.; Vanderlei, F.M.; Netto Junior, J.; Pastre, C.M. Can water temperature and immersion time influence the effect of cold water immersion on muscle soreness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2016, 46, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, L.J.; Simmons, G.H.; Nessler, J.A.; Newcomer, S.C. Characterisation of regional skin temperatures in recreational surfers wearing a 2-mm wetsuit. Ergonomics 2018, 61, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.; Saulino, M.; Lyong, K.; Simmons, M.; Nessler, J.A.; Newcomer, S.C. Effect of wetsuit outer surface material on thermoregulation during surfing. Sports Engineering 2020, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Alonso, J.; Quistorff, B.; Krustrup, P.; Bangsbo, J.; Saltin, B. Heat production in human skeletal muscle at the onset of intense dynamic exercise. J Physiol 2000, 524 Pt 2, 603–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racinais, S.; Oksa, J. Temperature and neuromuscular function. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010, 20 Suppl 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racinais, S.; Wilson, M.G.; Periard, J.D. Passive heat acclimation improves skeletal muscle contractility in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2017, 312, R101–R107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. Warm up I: potential mechanisms and the effects of passive warm up on exercise performance. Sports Med 2003, 33, 439–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.; Holdcroft, D.; Drawer, S.; Kilduff, L.P. Designing a warm-up protocol for elite bob-skeleton athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2013, 8, 213–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilduff, L.P.; Finn, C.V.; Baker, J.S.; Cook, C.J.; West, D.J. Preconditioning strategies to enhance physical performance on the day of competition. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2013, 8, 677–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, C.J.; Pyne, D.B.; Thompson, K.G.; Raglin, J.S.; Osborne, M.; Rattray, B. Elite sprint swimming performance is enhanced by completion of additional warm-up activities. J Sports Sci 2017, 35, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, D.J.; Dietzig, B.M.; Bracken, R.M.; Cunningham, D.J.; Crewther, B.T.; Cook, C.J.; Kilduff, L.P. Influence of post-warm-up recovery time on swim performance in international swimmers. J Sci Med Sport 2013, 16, 172–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, D.J.; Russell, M.; Bracken, R.M.; Cook, C.J.; Giroud, T.; Kilduff, L.P. Post-warmup strategies to maintain body temperature and physical performance in professional rugby union players. J Sports Sci 2016, 34, 110–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaven, M.; Kilduff, L.; Cook, C. Lower-limb passive heat maintenance combined with pre-cooling improves repeated sprint ability. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, J.M.; McNamara, P.; Osborne, M.; Andrews, M.; Oliveira Borges, T.; Walshe, P.; Chapman, D.W. Association between anthropometry and upper-body strength qualities with sprint paddling performance in competitive wave surfers. J Strength Cond Res 2012, 26, 3345–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.T.; Lundgren, L.; Secomb, J.; Farley, O.R.; Haff, G.G.; Seitz, L.B.; Newton, R.U.; Nimphius, S.; Sheppard, J.M. Comparison of physical capacities between nonselected and selected elite male competitive surfers for the National Junior Team. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2015, 10, 178–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, B.G.; Strahorn, J.; Colomer, C.; McKune, A.; Cook, C.J.; Pumpa, K. The effect of speed, power and strength training, and a group motivational presentation on physiological markers of athlete readiness: A case study in professional rugby. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surfing Australia. Surfing Australia Rule Book Surfing Australia: 2023.

- Wiles, T.; Simmons, M.; Gomez, D.; Schubert, M.; Newcomer, S.; Nessler, J. Foamed neoprene versus thermoplastic elastomer as a wetsuit material: a comparison of skin temperature, biomechanical, and physiological variables. Sports Engineering 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, M.; Moore, B.; Newcomer, S.; Nessler, J. Insulation and material characteristics of smoothskin neoprene vs silicone-coated neoprene in surf wetsuits. Sports Engineering 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviglio, C.M.; Crewther, B.T.; Kilduff, L.P.; Stokes, K.A.; Cook, C.J. Relationship between pregame concentrations of free testosterone and outcome in rugby union. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2014, 9, 324–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongers, C.; Thijssen, D.; Veltmeijer, M.; Hopman, M.; Eijsvogels, T. Precooling and percooling (cooling during exercise) both improve performance in the heat: a meta-analytical review. Br J Sports Med 2015, 49, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilduff, L.P.; West, D.J.; Williams, N.; Cook, C.J. The influence of passive heat maintenance on lower body power output and repeated sprint performance in professional rugby league players. J Sci Med Sport 2013, 16, 482–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowper, G.; Goodall, S.; Hicks, K.; Burnie, L.; Briggs, M. The impact of passive heat maintenance strategies between an active warm-up and performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2022, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamalha, E.; Zeng, Y.; Mwasiagi, J.; Kyatuheire, S. The comfort dimension: A review of perception in clothing. Journal of Sensory Studies 2013, 28, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchi, L.; Pourazad, N.; Michaelidou, N.; Tanusondjaja, A.; Harrigan, P. Marketing research on Mobile apps: past, present and future. J Acad Mark Sci 2022, 50, 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denny, A.; Moore, B.; Newcomer, S.; Nessler, J. Graphene-infused nylon fleece versus standard polyester fleece as a wetsuit liner: Comparison of skin termperatures during a recreational surf session. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notley, S.; Meade, R.; Kenny, G. Time following ingestion does not influence the validity of telemetry pill measurements of core temperature during exercise-heat stress: The journal temperature toolbox. Temperature (Austin) 2021, 8, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).