Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

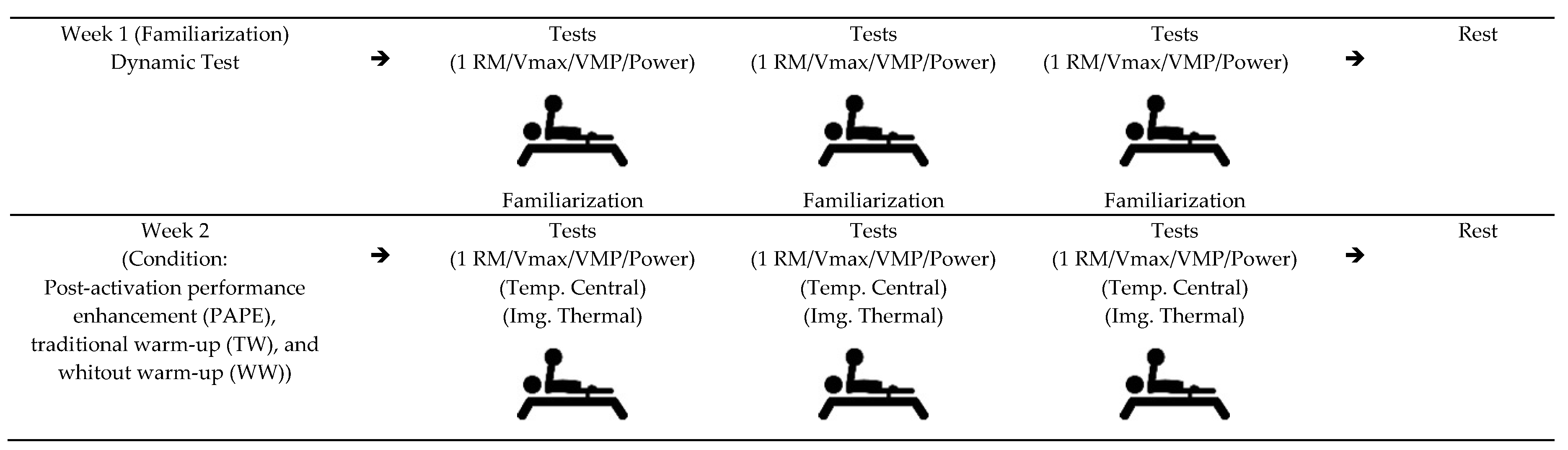

2.1. Experimental Design

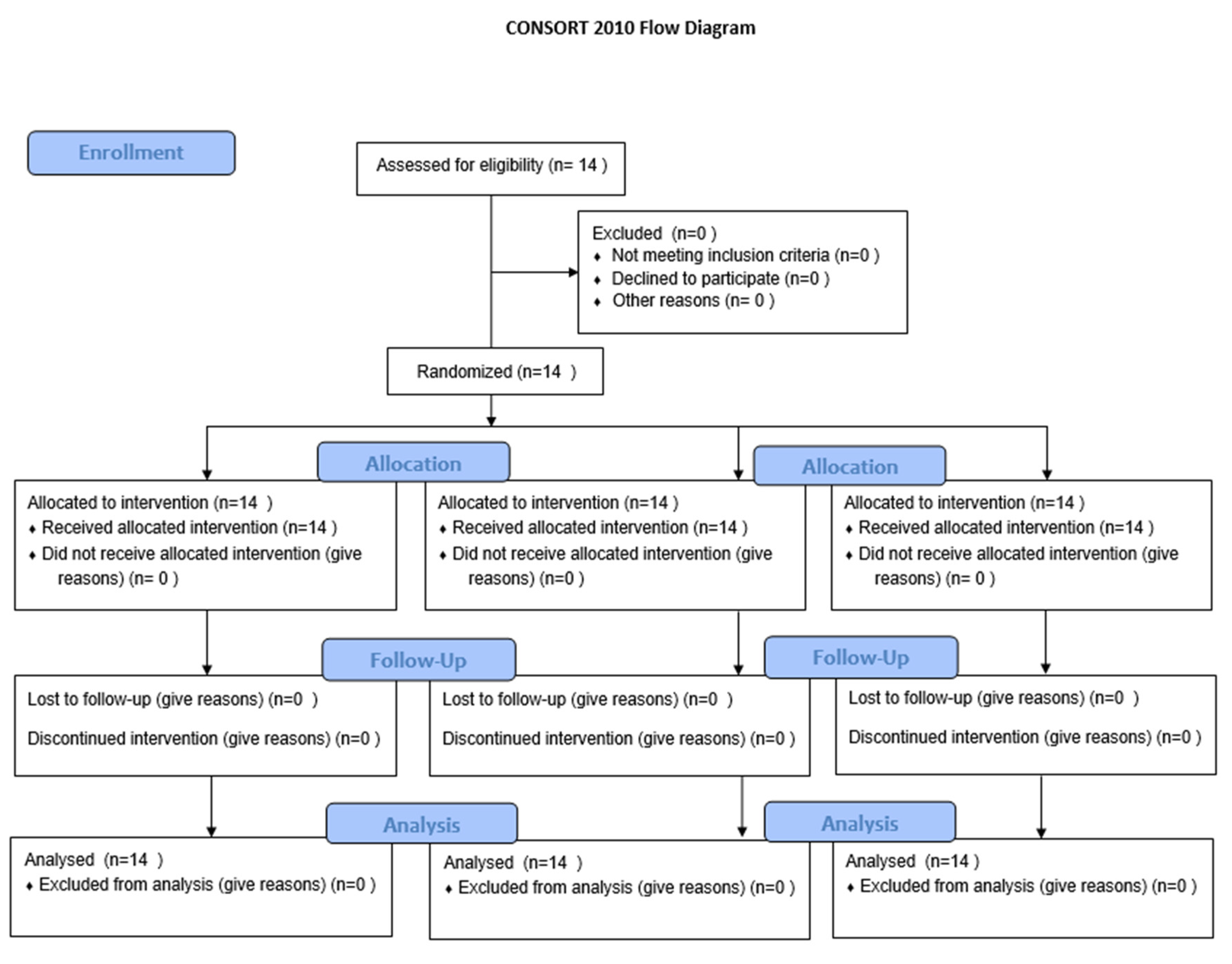

2.2. Sample

2.3. Instruments and Procedures

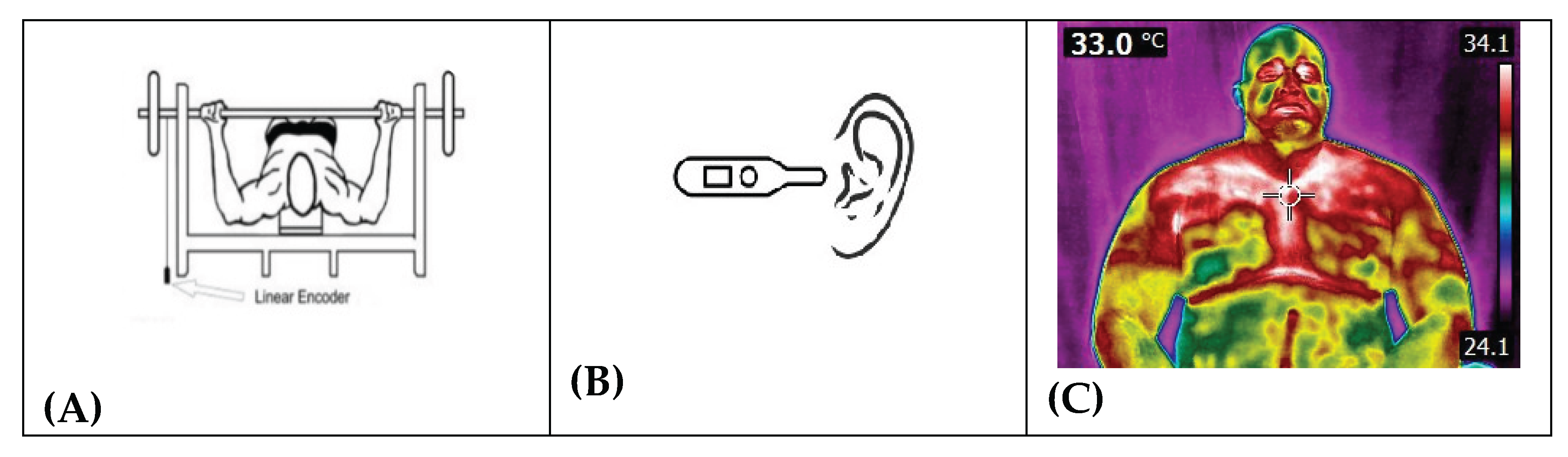

2.4. Maximum Load Test (1RM) and Dynamic Strength Indicators

2.5. Warm-Up Through Post Activation Performance Enhancement (PAPE)

2.6. Traditional Warm-Up (TW)

2.7. Without Warm-Up

2.8. Thermal Imaging

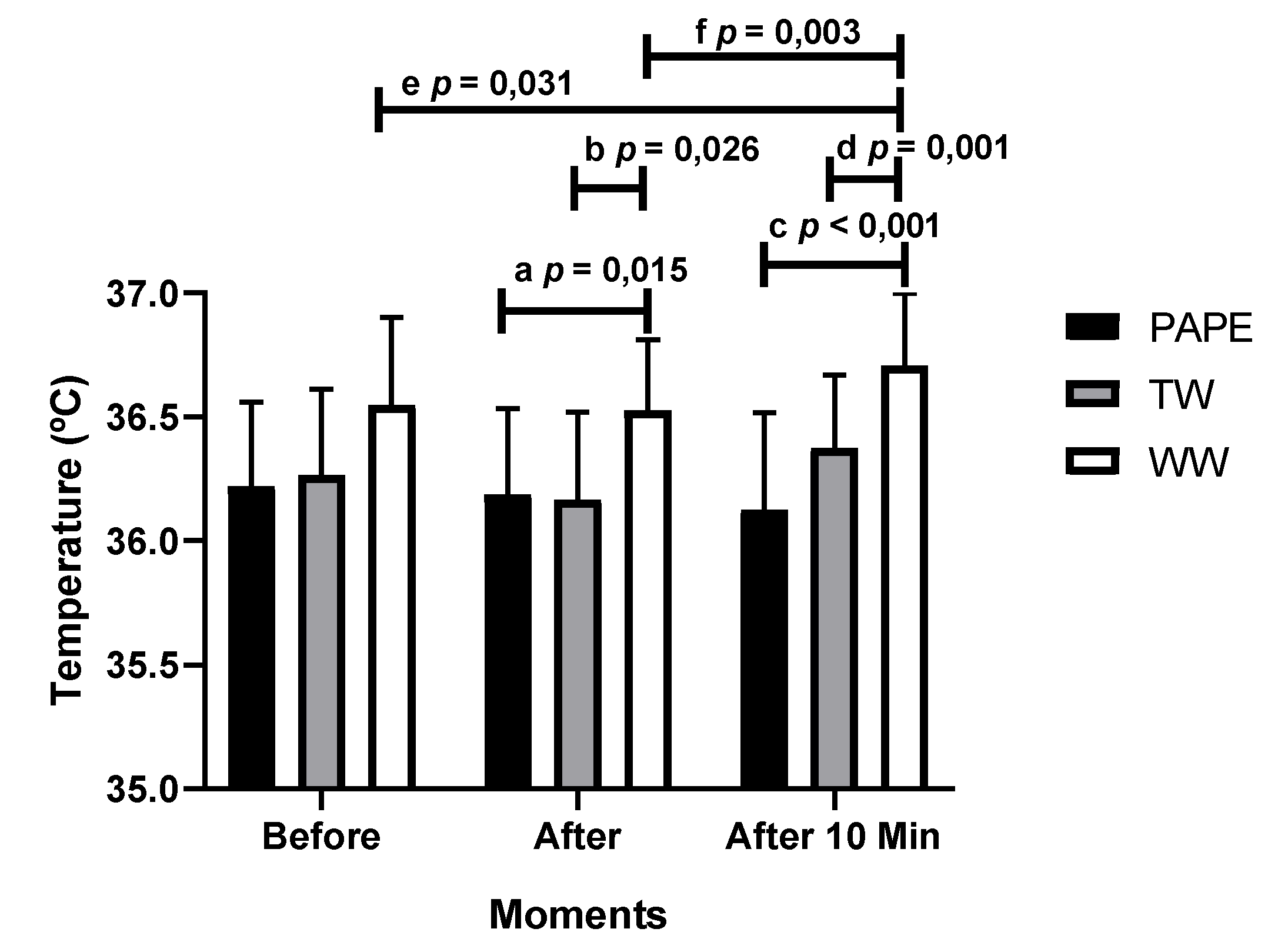

2.9. Tympanic Temperature

2.10. Statistics

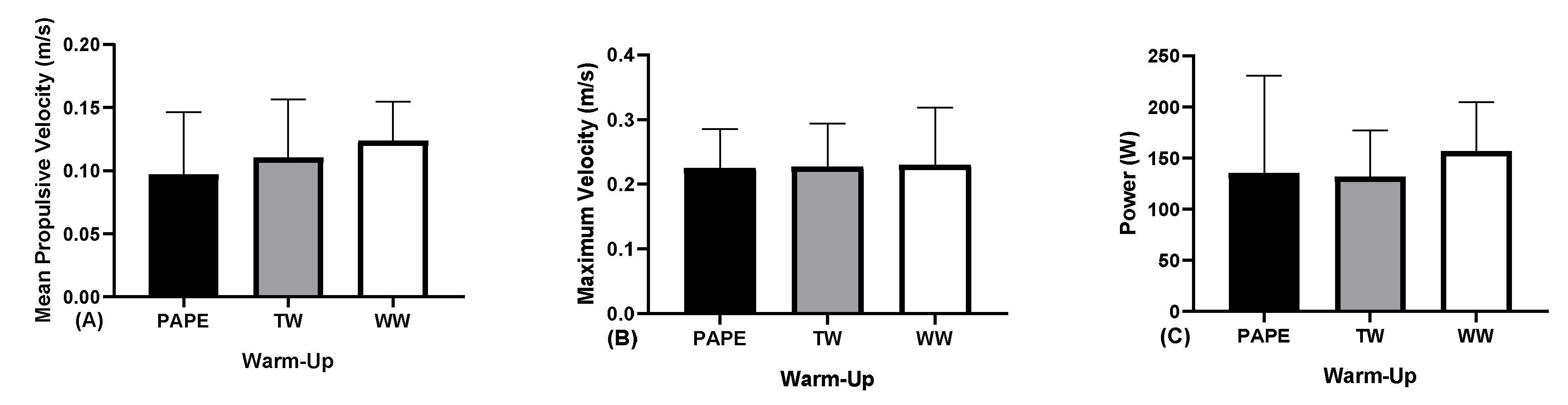

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

References

- International Paralympic Committee [Internet]. [citado 18 de outubro de 2024]. Para Powerlifting News & Events. Disponível em: https://www.paralympic.org/powerlifting.

- Aidar FJ, Clemente FM, de Lima LF, de Matos DG, Ferreira ARP, Marçal AC, et al. Evaluation of Training with Elastic Bands on Strength and Fatigue Indicators in Paralympic Powerlifting. Sports (Basel). 12 de outubro de 2021;9(10):142. [CrossRef]

- Aidar FJ, Brito CJ, de Matos DG, de Oliveira LAS, de Souza RF, de Almeida-Neto PF, et al. Force-velocity relationship in Paralympic powerlifting: two or multiple-point methods to determine a maximum repetition. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 24 de agosto de 2022;14(1):159.

- Blazevich AJ, Babault N. Post-activation Potentiation Versus Post-activation Performance Enhancement in Humans: Historical Perspective, Underlying Mechanisms, and Current Issues. Front Physiol. 1o de novembro de 2019;10:1359. [CrossRef]

- Boullosa D. Post-activation performance enhancement strategies in sport: A brief review for practitioners. Human Movement. 8 de março de 2021;22:101–9. [CrossRef]

- Afonso J, Brito J, Abade E, Rendeiro-Pinho G, Baptista I, Figueiredo P, et al. Revisiting the ‘Whys’ and ‘Hows’ of the Warm-Up: Are We Asking the Right Questions? Sports Med. 2024;54(1):23–30.

- Patti A, Giustino V, Hirose N, Messina G, Cataldi S, Grigoli G, et al. Effects of an experimental short-time high-intensity warm-up on explosive muscle strength performance in soccer players: A pilot study. Front Physiol. 25 de agosto de 2022;13:984305. [CrossRef]

- McGowan CJ, Pyne DB, Thompson KG, Rattray B. Warm-Up Strategies for Sport and Exercise: Mechanisms and Applications. Sports Med. novembro de 2015;45(11):1523–46.

- Borba D de A, Ferreira-Júnior JB, Santos LA dos, Carmo MC do, Coelho LGM. Effect of post-activation potentiation in Athletics: a systematic review. Rev bras cineantropom desempenho hum. fevereiro de 2017;19:128–38.

- de Aquino Resende M, Aidar FJ, Vasconcelos Resende RB, Reis GC, de Oliveira Barros L, de Matos DG, et al. Are Strength Indicators and Skin Temperature Affected by the Type of Warm-Up in Paralympic Powerlifting Athletes? Healthcare (Basel). 22 de julho de 2021;9(8):923.

- Winwood PW, Pritchard HJ, Wilson D, Dudson M, Keogh JWL. The Competition-Day Preparation Strategies of Strongman Athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. setembro de 2019;33(9):2308. [CrossRef]

- Resende M de A, Vasconcelos Resende RB, Reis GC, Barros L de O, Bezerra MRS, de Matos DG, et al. The Influence of Warm-Up on Body Temperature and Strength Performance in Brazilian National-Level Paralympic Powerlifting Athletes. Medicina (Kaunas). 14 de outubro de 2020;56(10):538.

- Shellock FG, Prentice WE. Warming-Up and Stretching for Improved Physical Performance and Prevention of Sports-Related Injuries. Sports Medicine. 1o de julho de 1985;2(4):267–78. [CrossRef]

- Gil MH, Neiva HP, Sousa AC, Marques MC, Marinho DA. Current Approaches on Warming up for Sports Performance: A Critical Review. Strength & Conditioning Journal. agosto de 2019;41(4):70.

- Iversen VM, Norum M, Schoenfeld BJ, Fimland MS. No Time to Lift? Designing Time-Efficient Training Programs for Strength and Hypertrophy: A Narrative Review. Sports Med. 2021;51(10):2079–95. [CrossRef]

- Park DS, Kwon IS, Yoon JH. The effects of different types of warm-up exercises on golf performance [Internet]. 2021 [citado 23 de agosto de 2024]. Disponível em: https://www.jomh.org/articles/10.31083/jomh.2021.036. [CrossRef]

- Yu W, Feng D, Zhong Y, Luo X, Xu Q, Yu J. Examining the Influence of Warm-Up Static and Dynamic Stretching, as well as Post-Activation Potentiation Effects, on the Acute Enhancement of Gymnastic Performance: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 1o de março de 2024;23(1):156–76. [CrossRef]

- Hsu FY, Tsai KL, Lee CL, Chang WD, Chang NJ. Effects of Dynamic Stretching Combined With Static Stretching, Foam Rolling, or Vibration Rolling as a Warm-Up Exercise on Athletic Performance in Elite Table Tennis Players. 28 de abril de 2020 [citado 21 de janeiro de 2025]; Disponível em: https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/jsr/30/2/article-p198.xml.

- Neves PP, Alves AR, Marinho DA, Neiva HP, Neves PP, Alves AR, et al. Warming-Up for Resistance Training and Muscular Performance: A Narrative Review. Em: Contemporary Advances in Sports Science [Internet]. IntechOpen; 2021 [citado 20 de dezembro de 2024]. Disponível em: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/75109.

- IPC - Paralympics News, Sports and Results [Internet]. [citado 23 de setembro de 2024]. Disponível em: https://www.paralympic.org/home.

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Medicine. 24 de março de 2010;8(1):18.

- Karvonen MJ, Kentala E, Mustala O. The effects of training on heart rate; a longitudinal study. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn. 1957;35(3):307–15.

- Adelsberger R, Tröster G. Effects of stretching and warm-up routines on stability and balance during weight-lifting: a pilot investigation. BMC Res Notes. 20 de dezembro de 2014;7:938.

- Soares Freitas Sampaio CR, Aidar FJ, Ferreira ARP, dos Santos JL, Marçal AC, de Matos DG, et al. Can Creatine Supplementation Interfere with Muscle Strength and Fatigue in Brazilian National Level Paralympic Powerlifting? Nutrients. 19 de agosto de 2020;12(9):2492.

- J F Steven, William K. Designing Resistance Training Programs, 4E. Human Kinetics; 2014. 520 p.

- Pérez-Castilla A, Piepoli A, Delgado-García G, Garrido-Blanca G, García-Ramos A. Reliability and Concurrent Validity of Seven Commercially Available Devices for the Assessment of Movement Velocity at Different Intensities During the Bench Press. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. maio de 2019;33(5):1258.

- Dote-Montero M, Pelayo-Tejo I, Molina-Garcia P, Carle-Calo A, García-Ramos A, Chirosa-Ríos LJ, et al. Effects of post-tetanic potentiation induced by whole-body electrostimulation and post-activation potentiation on maximum isometric strength. Biol Sport. março de 2022;39(2):451–61. [CrossRef]

- García Ramos A, Haff G, Padial P, Feriche B. Reliability of power and velocity variables collected during the traditional and ballistic bench press exercise. Sports Biomechanics. 24 de outubro de 2016;17. [CrossRef]

- Esformes JI, Keenan M, Moody J, Bampouras TM. Effect of Different Types of Conditioning Contraction on Upper Body Postactivation Potentiation. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. janeiro de 2011;25(1):143.

- Filho GF dos S, Aidar FJ, Getirana-Mota M, Brito CJ, Aedo-Muñoz E, de Almeida Paz Â, et al. Analysis of Velocity, Power and Skin Temperature in Paralympic Powerlifting Athletes with Fixed and Variable Resistance. Sports (Basel). 11 de setembro de 2024;12(9):250. [CrossRef]

- Santos LCV, Aidar FJ, Villar R, Greco G, de Santana JL, Marçal AC, et al. Evaluation of the Training Session in Elite Paralympic Powerlifting Athletes Based on Biomechanical and Thermal Indicators. Sports (Basel). 10 de agosto de 2023;11(8):151.

- Wilk M, Filip A, Krzysztofik M, Gepfert M, Zajac A, Del Coso J. Acute Caffeine Intake Enhances Mean Power Output and Bar Velocity during the Bench Press Throw in Athletes Habituated to Caffeine. Nutrients. 4 de fevereiro de 2020;12(2):406. [CrossRef]

- Fogt DL, Henning AL, Venable AS, Mcfarlin BK. Non-invasive Measures of Core Temperature versus Ingestible Thermistor during Exercise in the Heat. International Journal of Exercise Science. 1o de março de 2017;10(2):225.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. julho de 1992;112(1):155–9.

- Kuniszyk-Jóźkowiak W, Jaszczuk J, Czaplicki A, Szyszka P. Variability of shoulder girdle temperature in the initial phase of the snatch in weightlifting. Acta Bioeng Biomech. 2019;21(3):143–8.

- Woods A, Bishop P, Jones E. Warm-Up and Stretching in the Prevention of Muscular Injury. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). 1o de outubro de 2007;37:1089–99. [CrossRef]

- Boullosa D, Del Rosso S, Behm D, Foster C. Title: Post-Activation Potentiation (PAP) in Endurance Sports: A Review. European Journal of Sport Science. 5 de fevereiro de 2018;18.

- Hodgson M, Docherty D, Robbins D. Post-activation potentiation: underlying physiology and implications for motor performance. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). 1o de fevereiro de 2005;35:585–95.

- Švantner M, Lang V, Skála J, Kohlschütter T, Honner M, Muzika L, et al. Statistical Study on Human Temperature Measurement by Infrared Thermography. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) [Internet]. 2021 [citado 9 de janeiro de 2025];22. Disponível em: https://consensus.app/papers/statistical-study-on-human-temperature-measurement-by-%C5%A1vantner-lang/230d2e96d3d15c9c8bd123293ed68bcf/.

- Moreira DG, Costello JT, Brito CJ, Adamczyk JG, Ammer K, Bach AJE, et al. Thermographic imaging in sports and exercise medicine: A Delphi study and consensus statement on the measurement of human skin temperature. Journal of Thermal Biology. 1o de outubro de 2017;69:155–62. [CrossRef]

- Aidar FJ, Fraga GS, Getirana-Mota M, Marçal AC, Santos JL, de Souza RF, et al. Evaluation of Ibuprofen Use on the Immune System Indicators and Force in Disabled Paralympic Powerlifters of Different Sport Levels. Healthcare (Basel). 18 de julho de 2022;10(7):1331.

- Fraga GS, Aidar FJ, Matos DG, Marçal AC, Santos JL, Souza RF, et al. Effects of Ibuprofen Intake in Muscle Damage, Body Temperature and Muscle Power in Paralympic Powerlifting Athletes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17 de julho de 2020;17(14):5157.

- Maroto-Izquierdo S, Bautista IJ, Martín Rivera F. Post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) after a single bout of high-intensity flywheel resistance training. Biol Sport. dezembro de 2020;37(4):343–50.

- Rumeau V, Grospretre S, Babault N. Post-Activation Performance Enhancement and Motor Imagery Are Efficient to Emphasize the Effects of a Standardized Warm-Up on Sprint-Running Performances. Sports (Basel). 22 de maio de 2023;11(5):108.

- Rappelt L, Held S, Wiedenmann T, Micke F, Donath L. Post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) protocols do not further increase jumping performance beyond warm-up effects: findings from three acute randomized crossover trials. Front Physiol [Internet]. 14 de agosto de 2024 [citado 15 de abril de 2025];15. Disponível em: https://www.frontiersin.orghttps://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2024.1447421/full.

- Wilk M, Krzysztofik M, Filip A, Szkudlarek A, Lockie RG, Zajac A. Does Post-Activation Performance Enhancement Occur during the Bench Press Exercise under Blood Flow Restriction? Int J Environ Res Public Health. junho de 2020;17(11):3752.

- Garbisu-Hualde A, Gutierrez L, Fernández-Peña E, Santos-Concejero J. Intermittent Voluntary Isometric Contractions Effects on Performance Enhancement and Sticking Region Kinematics in the Bench Press. [citado 11 de setembro de 2024]; Disponível em: https://jhk.termedia.pl/Intermittent-Voluntary-Isometric-Contractions-Effects-on-Performance-Enhancement,161777,0,2.html. [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Filip A, Zmijewski P, Zajac A, Tufano JJ. Can Post-Activation Performance Enhancement (PAPE) Improve Resistance Training Volume during the Bench Press Exercise? Int J Environ Res Public Health. abril de 2020;17(7):2554.

- Tillin N, Bishop DJ. Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation and its Effect on Performance of Subsequent Explosive Activities. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). 1o de fevereiro de 2009;39:147–66.

- Liu H, Jiang L, Wang J. The effects of blood flow restriction training on post activation potentiation and upper limb muscle activation: a meta-analysis. Front Physiol [Internet]. 11 de julho de 2024 [citado 9 de setembro de 2024];15. Disponível em: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2024.1395283/full. [CrossRef]

- McCrary JM, Ackermann BJ, Halaki M. A systematic review of the effects of upper body warm-up on performance and injury. Br J Sports Med. 1o de julho de 2015;49(14):935–42.

- Wilk M, Krzysztofik M, Drozd M, Zajac A. Changes of Power Output and Velocity During Successive Sets of the Bench Press With Different Duration of Eccentric Movement. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 1o de fevereiro de 2020;15(2):162–7. [CrossRef]

- Garbisu-Hualde A, Gutierrez L, Santos-Concejero J. Post-Activation Performance Enhancement as a Strategy to Improve Bench Press Performance to Volitional Failure. J Hum Kinet. 15 de julho de 2023;88:199–206.

- Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Stastny P, Golas A. Post-activation Performance Enhancement in the Bench Press Throw: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol. 2020;11:598628.

- Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Stastny P, Golas A. Post-activation Performance Enhancement in the Bench Press Throw: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol. 15 de janeiro de 2021;11:598628. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro B, Pereira A, Neves PP, Sousa AC, Ferraz R, Marques MC, et al. The Role of Specific Warm-up during Bench Press and Squat Exercises: A Novel Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. janeiro de 2020;17(18):6882.

- Guo W, Liang M, Lin J, Zhou R, Zhao N, Aidar FJ, et al. Time Duration of Post-Activation Performance Enhancement (PAPE) in Elite Male Sprinters with Different Strength Levels. Children (Basel). 26 de dezembro de 2022;10(1):53. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Su Q, Yang J, Li G, Zhang S, Lv Y, et al. Effects of rest interval and training intensity on jumping performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating post-activation performance enhancement. Front Physiol. 23 de junho de 2023;14:1202789.

- Chen CF, Chuang CY, Wang CC, Liu SA, Chang HW, Chan KH. Lower Repetition Induces Similar Postactivation Performance Enhancement to Repetition Maximum After a Single Set of Heavy-Resistance Exercise. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. maio de 2024;38(5):848.

- Chen Y, Su Q, Yang J, Li G, Zhang S, Lv Y, et al. Effects of rest interval and training intensity on jumping performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating post-activation performance enhancement. Front Physiol [Internet]. 23 de junho de 2023 [citado 23 de setembro de 2024];14. Disponível em: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2023.1202789/full.

- Chen CF, Chuang CY, Wang CC, Liu SA, Chang HW, Chan KH. Lower Repetition Induces Similar Postactivation Performance Enhancement to Repetition Maximum After a Single Set of Heavy-Resistance Exercise. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. maio de 2024;38(5):848. [CrossRef]

| Warm-up | Pectoral Clavicular X ± DP (95% CI) |

Sternal Pectoral X ± DP (95% CI) |

Deltoid X ± DP (95% CI) |

Tríceps X ± DP (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAPE (A) |

33,79±1,51 (32,95-34,63) |

32,43±2,05 (31,29-33,56) |

33,65±1,24 (32,96-34,33) |

30,97±1,08 (30,38-31,57) |

| Traditional Warm-up (B) |

34,04±1,43 (33,25-34,83) |

33,17±1,62 (32,27-34,06) |

33,74±1,38 (32,98-34,50) |

32,06±1,16 A (31,42-32,70) |

| Without Warm-up (C) |

34,44±1,16 (33,79-35,09) |

33,25±1,28 (32,54-33,95) |

33,96±1,11 (33,35-34,57) |

31,29±1,16 (30,64-31,93) |

| A vs B |

p = 0,390 d = 0,229 |

p = 0,063 d = 0,522 |

p = 0,727 d =0,092 |

p < 0,001 d = 1,308 |

| A vs C |

p = 0,030 d = 0,624 |

p = 0,043 d =0,575 |

p = 0,193 d = 0,353 |

p = 0,159 d = 0,384 |

| B vs C |

p = 0,141 d = 0,403 |

p = 0,786 d = 0,071 |

p = 0,388 d = 0,230 |

p = 0,004 d = 0,896 |

| P |

p=0,159 |

0.061 |

0.743 |

A p<0,001 |

| η2p | XXX | XXX | XXX | 0,371 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).