1. Introduction

Warm-up exercises are crucial in recreational training and competition as they prepare the body physiologically and psychologically, reduce injury risk, and enhance performance across individual and team sports [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Different warm-up strategies have been investigated, and research tends to agree regarding their positive impact on physical performance [

5,

6,

7,

8]. For instance, warm-up by running or cycling for 15 min at 80% of maximum oxygen uptake improves vertical jump performance immediately and in the following 20 min post-warm-up [

9,

10]. Furthermore, warm-up by running 500 m at 70% running intensity followed by 3 x 250 m at 100% running intensity significantly benefits running performance in the 5000 m in trained endurance runners [

11].

In resistance training, extensive research has been conducted to analyze the impact of post-activation potentiation (PAP), the role of general and/or specific warm-up procedures, and the effects of various warm-up protocols (e.g., varying volumes and intensities). Studies have documented the PAP effect following various exercises, including maximal loaded, submaximal loaded, and unloaded exercises [

12,

13,

14]. According to Wilson et al. [

14], the potentiation of warm-up can be optimized with multiple sets performed at moderate intensities (i.e., 60-84% of 1RM) and rest periods between 7-10 minutes in practitioners with at least one year of resistance training background. Furthermore, combining general and specific warm-ups improves force production and increases strength in the one-repetition maximum (1RM) test compared to just performing a specific warm-up during 1RM testing procedures [

15]. A study by Barnes et al. [

2] demonstrated that a specific warm-up tailored to the exercise led to a more significant enhancement in peak power for the high pull than a general warm-up.

While many previous studies have shown the benefits of warming up before resistance training, few have explored different strategies, including monitoring movement velocity, to quantify training intensity and the level of effort following specific warm-up strategies [

16,

17,

18]. Measuring movement velocity in real-time in a resistance training setting offers a reliable and regular means of monitoring exercise intensity and effort [

19]. The measurement of repetition velocity is an accurate and objective indication of the actual exertion and level of effort experienced by the practitioner during training, providing valuable information to strength and conditioning coaches [

19]. Following this velocity-monitored resistance training approach, recent findings demonstrated that specific warm-ups comprising two sets of six repetitions performed with maximal intended velocities at 40% and 80% of the training load (i.e., 32 and 64% of 1RM) enhance neuromuscular function, enabling higher movement velocity outputs in the initial squat and bench press repetitions and achieving peak velocities more quickly [

18]. Furthermore, a specific warm-up of one set of six repetitions performed with maximal intended velocities at 80% of 1RM seems more effective in potentiating mechanical performance in the squat than at 40% of 1RM in resistance-trained males [

17]. On the other hand, a specific warm-up involving two sets of six repetitions performed with maximal intended velocities with progressive loads (40% to 80% of 1RM) may be more effective in increasing mechanical performance in the bench press than a single set [

17].

Although efforts have been made to understand the effect of warming up in its various forms (e.g., general and specific) on force production and strength performance [

15,

20,

21], resistance training is typically not just a single exercise but a sequence of different exercises targeting the same or different muscle groups. In this respect, it stands out that it is important to understand whether re-warming up for the following strength exercises has benefits on mechanical (i.e., velocity) and physiological performance (e.g., heart rate and lactate responses). However, little is known about the need to re-warm-up during the session using specific warm-ups to enhance subsequent exercise performance. This need is even more evident when the muscle groups that are most stimulated are not the same in the following exercises to be performed. Therefore, considering that the warm-up effect may decrease throughout the session, especially during inactivity [

22] and if the intensity is low [

9,

10], an effective and practical solution to avoid this decline becomes necessary. It is important to balance the free time available in sessions and improve physical performance through re-warming strategies between exercises, primarily when focusing on different muscle groups during sessions.

Therefore, considering the research gap about the impact of re-warming-up in the subsequent strength exercises, this study aimed to analyze the effects of different re-warm-up strategies before the squat or bench press on mechanical, physiological, and psychophysiological responses in recreational-trained men. It was hypothesized that performing a specific rewarm-up following the first strength exercise of the session would improve mechanical performance in the squat and bench press and produce a similar physiological and psychophysiological response in recreational-trained men.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty-two male sport sciences students aged between 19 and 32 (22.8 ± 3.3 years, 76.1 ± 12.6 kg, and 1.78 ± 0.06 m; 1RM bench press: 78.5 ± 11.6 kg; 1RM squat: 96.0 ± 23.1 kg) volunteered to participate in this study. Each participant reported no previous illness, injury, or other physical problems that could impair their performance during resistance training sessions. All participants were verbally informed about the study procedures and signed a consent form. The inclusion criteria comprised male participants aged 18 or over, without physical limitations or restrictions to perform resistance exercises, and at least 6 months of resistance training experience, especially in the bench press and squat. Participants who met the criteria and voluntarily agreed to participate in the study were included. All procedures followed the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Beira Interior (approval number: CE-UBI-Pj-2021-018).

Experimental Design

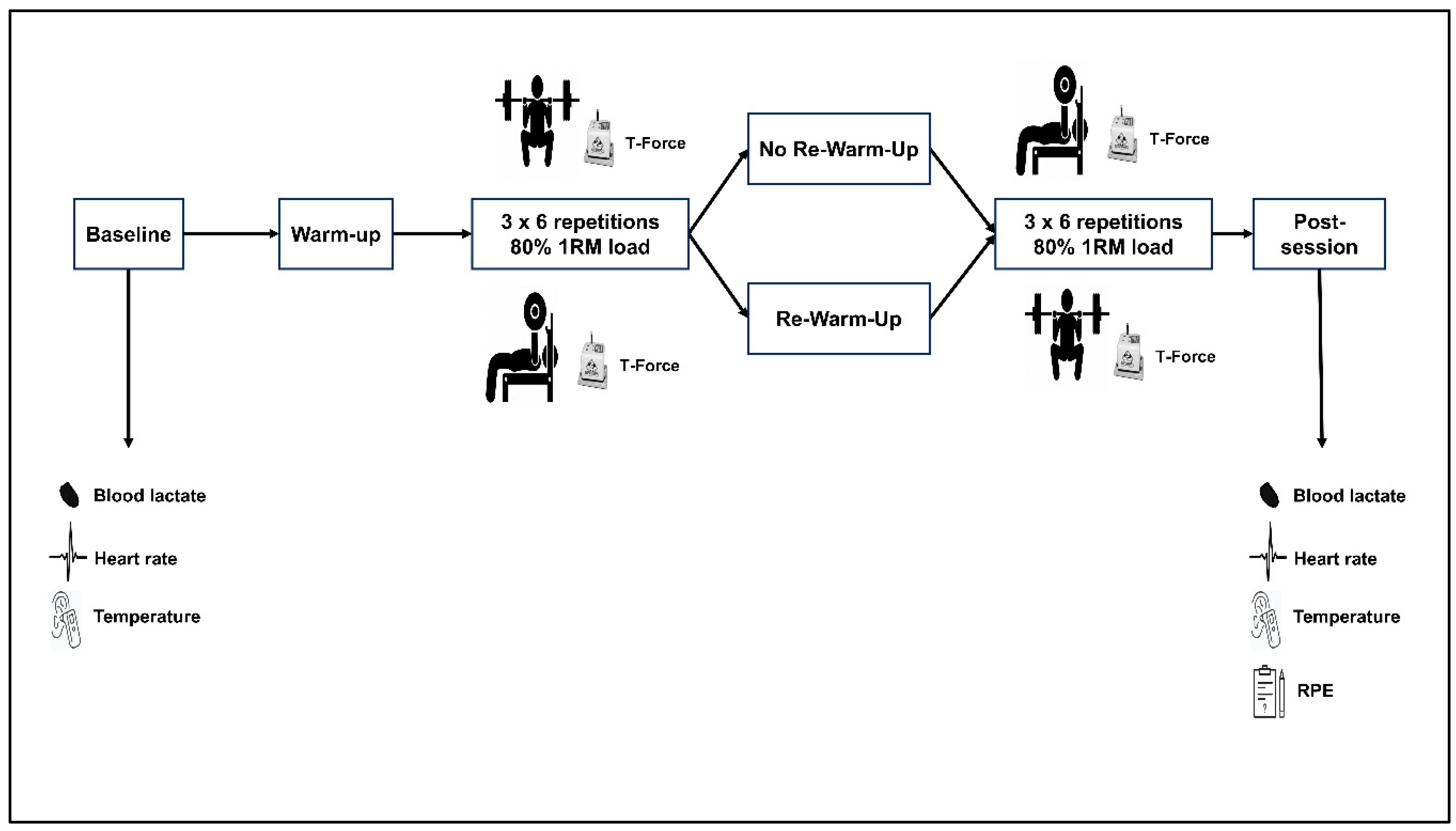

In a crossover design, participants performed four resistance training sessions with or without re-warm-up conditions following the first strength exercise in a randomized order with at least 48 hours of rest between each. The experimental conditions were: i) Warm-Up + Squat + Bench Press (W+SQ+BP); ii) Warm-Up + Squat + Re-Warm-Up + Bench Press (W+SQ+RW+BP); iii) Warm-Up + Bench Press + Squat (W+BP+SQ); iv) Warm-Up + Bench Press + Re-Warm-Up + Squat (W+BP+RW+SQ). Heart rate, blood lactate, and tympanic temperature (physiological variables) were measured at baseline and immediately after the last exercise of the session. The rate of perceived exertion (RPE; psychophysiological variable) was also collected immediately after the last exercise of the session. In all sessions, participants performed three sets of six repetitions at 80% of 1RM in the squat and bench press. A linear velocity transducer (T-Force Dynamic Measurement System, Ergotech, Murcia, Spain) with the cable connected to the barbell of a Multipower (Multipower Fitness Line, Perola, Murcia, Spain) collected all mechanical variables during the execution of repetitions. Mechanical variables included mean propulsive velocity (MPV), peak velocity (PV), time to peak velocity (TPV), velocity loss (VL), mean propulsive power (MPP), peak power (PP), and bar displacement. The degree of fatigue was expressed as the effort index (EI) [

23]. The experimental procedures of the study lasted three weeks, with two sessions performed per week. The first was to familiarize the participants with the testing protocols and measure height and body mass (Seca Instruments, Ltd, Hamburg, Germany). Then, participants performed a progressive loading test in the second session to determine the 1RM load in the bench press and squat. In the following sessions, participants performed experimental conditions.

Figure 1 illustrates the experimental design.

Progressive Loading Test in the Bench Press and Squat

In the bench press test, participants lay supine on a flat bench with feet on the floor and hands placed slightly wider than shoulder-width on the barbell [

24,

25]. They lowered the barbell to the chest, just above the nipples, in a controlled manner, and after approximately one second of pause, they performed the concentric phase as fast as possible [

24]. Participants were not allowed to bounce the barbell off the chest or to raise the shoulders or trunk off the bench [

26]. In the squat, participants started from an upright position with knees and hips fully extended, hands placed slightly wider than shoulder-width on the barbell, and the barbell resting on the back at the level of the acromion [

27]. Then, they began to descend until the tops of the thighs were below 90º in continuous movement (eccentric phase), and immediately after, they ascend at maximum velocity to the initial position (concentric phase) [

27]. Two experienced strength coaches were on both sides of the barbell to ensure safety. In both exercises, the first researcher and strength coaches controlled the movement to guarantee that all repetitions were performed with the required technique and a similar range of movement. The initial load was fixed at 17 kg and 20 kg for all participants in the bench press and squat, respectively, and gradually increased by 10 kg. The test finished when participants reached a concentric MPV of 0.40 m.s

-1 in the bench press and 0.60 m.s

-1 in the squat, corresponding to 85% 1RM in both exercises [

27,

28]. Inter-set recoveries ranged from 3 minutes (light loads) to 5 minutes (heavy loads). The 1RM load was determined from the last MPV obtained during the test as follows: (100 x Load) / (8.4326 x MPV

2 – 73.501 x MPV + 112.33) for the bench press [

28], and (100 x load) / (-5.961 x MPV

2 – 50.71 x MPV + 117) for the squat [

27].

Resistance Training Protocols

The warm-up included 10 minutes of treadmill running, starting at 50-55% of heart rate reserve until reaching 70% in the last 2 minutes, followed by two sets of six repetitions at 32% and 64% of 1RM in the squat or bench press [

16]. After a three-minute pause for physiological and psychophysiological variables, participants performed three sets of six repetitions at 80% of 1RM in the bench press or squat, with a three-minute interval between sets. Then, depending on the experimental condition, participants either performed a re-warm-up of two sets of six repetitions at 32% and 64% of 1RM in the squat or bench press or immediately performed the second exercise without re-warm-up. All concentric repetitions were performed with the maximal intended velocity, while the eccentric phase was controlled (~3 seconds). The first researcher and two strength coaches (each coach on each side of the barbell to spot participants) supervised all sessions to guarantee a correct execution technique and encourage participants to exert maximum effort during all repetitions.

Measurement of Physiological and Psychophysiological Parameters

Heart rate was monitored during all sessions with a Polar watch (Polar Vantage NV, Kempele, Finland). Blood lactate concentration was measured using a hand-held portable device (Lactate Pro 2 LT-1730, Arkray Inc., Tokyo, Japan). After cleansing the site with 70% alcohol, the fingertip was punctured using a disposable lancet. The first drop of blood was discarded, and a tiny blood sample was collected for analysis [

29]. Tympanic temperature was measured with an infrared thermometer to estimate the central body temperature (Braun Thermoscan IRT 4520, Kronberg, Germany) [

30]. RPE values were measured using a 15-grade scale (Borg scale 6-20) [

31].

Statistical Analysis

Considering an expected difference in MPV of 0.04 ± 0.03 m·s

-1 between experimental conditions with versus without re-warm-up [

18], a significance level of 0.05, a statistical power of 80%, and a drop-out rate of 20%, an estimated sample size of 12 participants was required [

32]. Microsoft Office Excel (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA, USA) was used to collect physiological and psychophysiological results and extract data from the T-Force software. Afterward, data was analyzed in SPSS (v27.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The Shapiro-Wilk test analyzed the normality of the data. After confirming the assumption of data normality, paired t-tests were used to compare experimental conditions with vs. without re-warm-up (W+SQ+BP vs. W+SQ+RW+BP; W+BP+SQ vs. W+BP+RW+SQ) in mechanical, physiological, and psychophysiological variables. The significance level was set at

p ≤ 0.05. The effect size (ES) was calculated using Cohen’s

d to determine the magnitude of the differences between conditions. The ES was interpreted as trivial (0.00–0.19), small (0.20–0.59), moderate (0.60–1.19), large (1.20–1.99), very large (2.00–3.99), and extremely large (> 4.00) [

33]. Figures were generated in GraphPad Prism (v7.0, GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

Mechanical Differences Between Experimental Conditions with vs. Without Re-Warm-Up

Table 1 shows significant differences between W+BP+SQ vs. W+BP+RW+SQ conditions on MPV (first set: t

21 = -2.43,

p = 0.02, ES = 0.52; second set: t

21= -2.25,

p = 0.04, ES = 0.48; third set: t

21 = -2.09,

p = 0.05, ES = 0.45), PV (first set: t

21 = -2.89,

p = 0.01, ES = 0.62; second set: t

21 = -2.69,

p = 0.01, ES = 0.57), MPP (second set: t

21 = - 2.57,

p = 0.02, ES = 0.55; third set: t

21 = - 2.10,

p = 0.05, ES = 0.45), and PP (second set: t

21 = - 3.11,

p = 0.01, ES = 0.66; third set: t

21 = -2.18,

p = 0.04, ES = 0.47).

Table 2 shows significant differences between W+SQ+BP vs. W+SQ+RW+BP on VL (third set: t

21 = 2.48,

p = 0.02, ES = 0.53), TPV (second set: t

21 = 2.98,

p = 0.01, ES = 0.64), and EI (third set: t

21 = -0.23,

p = 0.01, ES = 0.60).

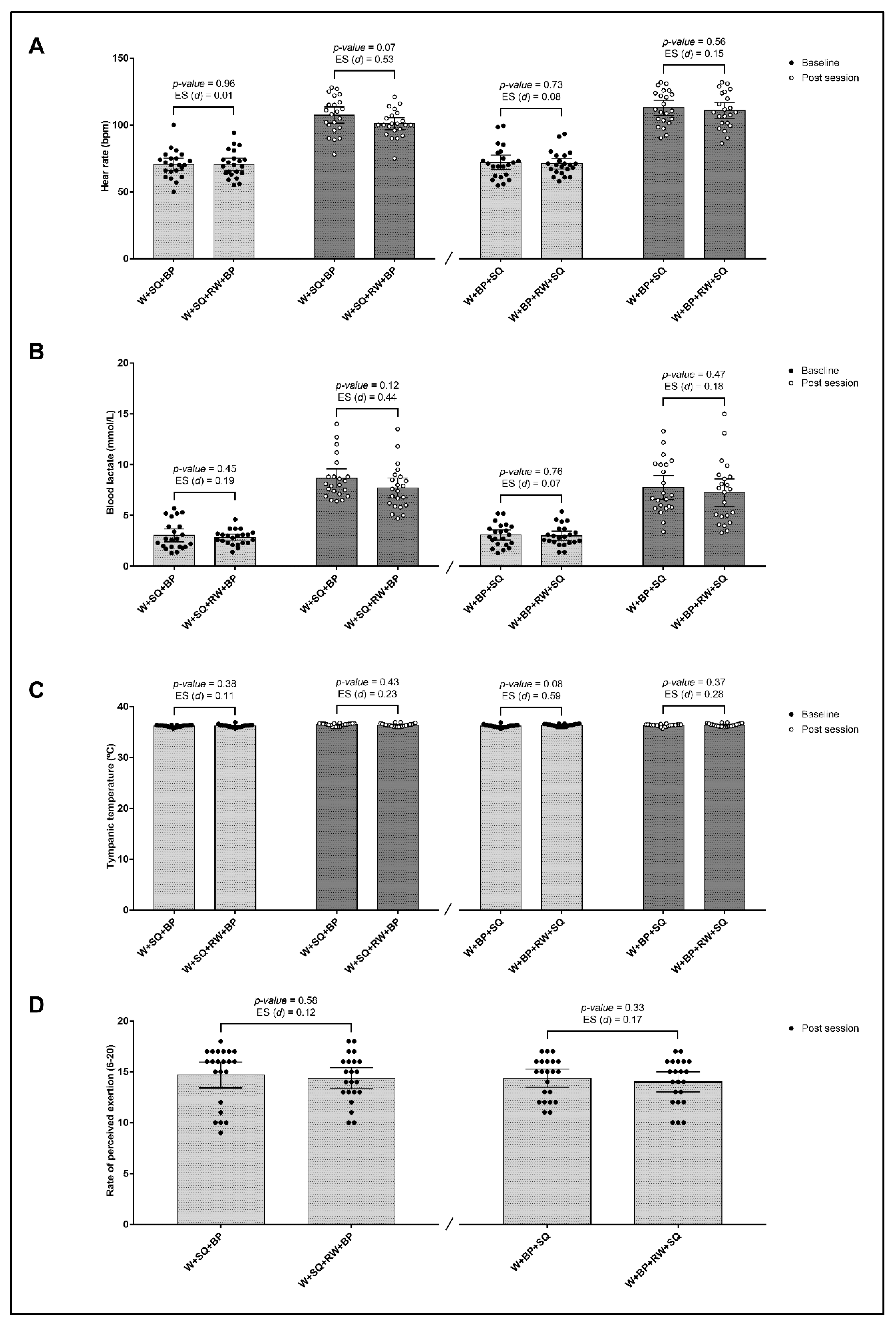

Physiological and Psychophysiological Differences Between Experimental Conditions With vs. Without Re-Warm-Up

Figure 2 shows no significant differences in physiological and psychophysiological parameters between W+SQ+BP vs. W+SQ+RW+BP and W+BP+SQ vs. W+BP+RW+SQ at baseline and post-session.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the effects of re-warm-up after the first strength exercise of the session (bench press or squat) on mechanical, physiological, and psychophysiological parameters in recreational-trained men. The hypothesis that the re-warm-up would improve mechanical performance in the squat and bench press was partially confirmed by the present findings. Re-warming up between the bench press and squat (W+BP+RW+SQ condition) was shown to be more favorable for enhancing MPV and PV during the first two sets of squats than not performing sets of re-warm-up (W+BP+SQ condition). Moreover, the power-related variables were higher in the second and third sets when the re-warm-up was performed. On the other hand, the re-warm-up between the squat and bench press (W+SQ+RW+BP condition) did not show differences in the propulsive velocity compared to the no-re-warm-up condition (W+SQ+BP condition). However, the relative VL and EI were higher in the third set of the bench press when no re-warm-up was completed after the squat. The comparison between experimental conditions with vs. without re-warm-up revealed no significant differences in physiological and psychophysiological parameters, confirming our second hypothesis that an additional warm-up in the session would not cause a disturbance in physiological parameters. These results highlight the importance of re-warming up during the resistance training session to optimize mechanical performance, primarily when the following exercise works different muscle groups compared to the previous exercise.

In our study, the re-warm-up effect optimized the mechanical performance in the squat exercise, which aligns with previous studies that observed similar mechanical responses [

17,

18]. This result can occur because the squat recruits large muscle groups, such as the quadriceps femoris and gluteus maximus [

34], which may benefit from a pre-activation to maximize force production and propulsive velocity. Contrarily, when the re-warm-up was performed between the squat and bench press (W+SQ+RW+BP condition), it did not result in any additional effect on the mechanical performance of the bench press. This result may be explained because the bench press, contrary to the squat, involves smaller muscle groups than the squat [

23,

35], which may benefit from the muscular activation performed in the previous and different exercises, including the squat.

Over the years, the warm-up phase has been considered a critical component of a training session to potentiate the performance of athletes in different sports [

7]. It is well-known that the warm-up routine increases body temperature, preparing the body for the following activity, which can supply positive effects in physiological parameters, such as the increment of the metabolic efficiency or nerve conduction rate and a decrease in muscular stiffness [

36,

37]. Despite the benefits of the warm-up, some uncertainties remain regarding re-warm-ups’ effects in specific resistance training activities [

20,

38]. Following the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines [

39] for resistance training prescription in novice and untrained individuals, it is recommended to prescribe exercises focusing on full-body, and a special preference to apply a general warm-up at the beginning of the session. However, there is still a gap in the literature about the contribution of warm-up or re-warm-up in resistance training performance.

Our results reported that re-warming up between the squat and bench press (W+SQ+RW+BP) seemed indifferent to obtaining better physical performance, as the propulsive velocity did not report differences between the experimental condition without re-warm-up (W+SQ+BP). However, the TPV in the bench press was inferior in the second set using the re-warm-up condition, which can be important for practitioners who aim to increase the ability to produce force quickly. Furthermore, it is relevant to highlight the lower VL and EI measured in the last set performed on the bench press when the re-warm-up was used after the squat. Considering that EI is a powerful indicator of neuromuscular fatigue [

23], the current results may support the relevance of the re-warm-up in the sense that it can contribute to attenuating fatigue levels and preserving the ability to produce force for longer within the training session.

Although no differences were found between experimental conditions with vs. without re-warm-up in physiological responses, re-warm-up after the squat or bench press resulted in slightly, not significantly, lower blood lactate concentrations compared to conditions without re-warm-up. These results might be related to the decrease in volume and relative intensity during the re-warm-up phase, which may also enable the body to recover between exercises. Therefore, if the metabolic responses following the re-warm-up strategies were slightly lower, they do not negatively influence the performance of the subsequent exercise. Since no more differences were found in other physiological and psychophysiological (RPE) variables between conditions with and without re-warm-up, future studies must employ a detailed analysis using, for example, muscle temperature, hormonal responses, and motor control after exercise for a deeper analysis.

Some limitations should be addressed in this study. First, a small sample size of men was used, and a larger sample including both sexes would provide more evident conclusions in the analyzed variables and support the effects of different warm-up approaches, including re-warm-up routines. Second, only the squat and bench press were included in the study. Usually, resistance training is not constituted by only these two exercises, reinforcing the need to include more exercises in future research. Lastly, including additional physiological variables (e.g., creatine kinase, testosterone, cortisol) would allow us to analyze the impact of different re-warm-up strategies more deeply. Even conscious of the study’s limitations, the current findings are important for researchers and strength and conditioning coaches to provide evidence about the warm-up methodologies and their effects on resistance training performance. Future research should include additional resistance training exercises (e.g., knee extension and biceps curls) or even supplementary variables such as muscle temperature and hormonal responses to enrich the knowledge of the warm-up phenomenon in resistance training performance. These analyses could be pertinent and helpful in increasing the understanding of the effects of different warm-up routines in recreational contexts and sports performance.

This study has practical implications for researchers and strength and conditioning coaches when implementing interventions in recreational-trained males. Based on the results, when combining the bench press and squat in the same resistance training session, performing a re-warm-up following the bench press might be indicated to improve the squat’s propulsive velocity. Furthermore, introducing a re-rewarm-up between the squat and bench press might be indicated to decrease the magnitude of fatigue in the last sets and preserve mechanical performance over the sets. Finally, performing a re-warm-up in both protocols will not induce a more significant increase in heart rate, blood lactate, tympanic temperature, and RPE when compared to not performing a re-warm-up.

5. Conclusions

The current study highlights the potential benefits of re-warm-up for improving mechanical performance during resistance training, particularly in the squat, in recreational-trained men. When the squat was performed after the bench press, the re-warm-up demonstrated a notable increase in propulsive velocity, indicating its positive influence on physical performance outcomes. However, when the bench press followed the squat, the impact of the re-warm-up appeared less pronounced. Considering physiological and psychophysiological parameters, no differences were found between experimental conditions with vs. without re-warm-up. The current results highlight the positive impact of re-warm-up between exercises in mechanical performance, emphasizing the need for personalized approaches to optimize resistance training outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P.N., A.R.A., and H.P.N.; methodology, H.P.N.; validation, A.R.A., H.P.N., and D.L.M.; formal analysis, H.P.N., and D.L.M.; investigation, P.P.N.; resources, D.A.M., R.F., M.C.M., and H.P.N.; data curation, P.P.N., A.R.A., H.P.N., and D.L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P.N., and A.R.A.; writing—review and editing, D.L.M., H.P.N, D.A.M., R.F., M.C.M., and A.R.A.; visualization, P.P.N.; supervision, A.R.A., H.P.N., and D.L.M..; project administration, P.P.N.; funding acquisition, D.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by national funding through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the project UIDB/04045/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki recommendations and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Beira Interior (approval number: CE-UBI-Pj-2021-018:ID720; approval date: June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participation of the students from the University of Beira Interior.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ayala, F.; Moreno-Pérez, V.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; Moya, M.; Sanz-Rivas, D.; Fernandez-Fernandez, J. Acute and Time-Course Effects of Traditional and Dynamic Warm-Up Routines in Young Elite Junior Tennis Players. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152790, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152790. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.J.; Petterson, A.; Cochrane, D.J. Effects of Different Warm-up Modalities on Power Output during the High Pull. Journal of Sports Sciences 2017, 35, 976–981, doi:10.1080/02640414.2016.1206665. [CrossRef]

- Neiva, H.P.; Marques, M.C.; Fernandes, R.J.; Viana, J.L.; Barbosa, T.M.; Marinho, D.A. Does Warm-Up Have a Beneficial Effect on 100-m Freestyle? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2014, 9, 145–150, doi:10.1123/ijspp.2012-0345. [CrossRef]

- Zois, J.; Bishop, D.; Aughey, R. High-Intensity Warm-Ups: Effects During Subsequent Intermittent Exercise. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2015, 10, 498–503, doi:10.1123/ijspp.2014-0338. [CrossRef]

- Fradkin, A.J.; Zazryn, T.R.; Smoliga, J.M. Effects of Warming-up on Physical Performance: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2010, 24, 140–148, doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c643a0. [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.H.; Neiva, H.P.; Alves, A.R.; Sousa, A.C.; Ferraz, R.; Marques, M.C.; Marinho, D.A. The Effect of Warm-up Running Technique on Sprint Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2021, 35, 3341–3347, doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003528. [CrossRef]

- McGowan, C.J.; Pyne, D.B.; Thompson, K.G.; Rattray, B. Warm-Up Strategies for Sport and Exercise: Mechanisms and Applications. Sports Med 2015, 45, 1523–1546, doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0376-x. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.M.; Neiva, H.P.; Marques, M.C.; Izquierdo, M.; Marinho, D.A. Effects of Warm-Up, Post-Warm-Up, and Re-Warm-Up Strategies on Explosive Efforts in Team Sports: A Systematic Review. Sports Med 2018, 48, 2285–2299, doi:10.1007/s40279-018-0958-5. [CrossRef]

- Chiba, I.; Samukawa, M.; Takizawa, K.; Nishikawa, Y.; Ishida, T.; Kasahara, S.; Yamanaka, M.; Tohyama, H. Warm-Up Intensity and Time-Course Effects on Jump Height under Cold Conditions. IJERPH 2022, 19, 5781, doi:10.3390/ijerph19095781. [CrossRef]

- Tsurubami, R.; Oba, K.; Samukawa, M.; Takizawa, K.; Chiba, I.; Yamanaka, M.; Tohyama, H. Warm-Up Intensity and Time Course Effects on Jump Performance. J Sports Sci Med 2020, 19, 714–720.

- Alves, M.D.D.J.; Knechtle, B.; Silva, D.D.S.; Fernandes, M.S.D.S.; Gomes, J.H.; Thuany, M.; Aidar, F.J.; Weiss, K.; De Souza, R.F. Effects of High-Intensity Warm-Up on 5000-Meter Performance Time in Trained Long-Distance Runners. J Sports Sci Med 2023, 254–262, doi:10.52082/jssm.2023.254. [CrossRef]

- Chaouachi, A.; Castagna, C.; Chtara, M.; Brughelli, M.; Turki, O.; Galy, O.; Chamari, K.; Behm, D.G. Effect of Warm-Ups Involving Static or Dynamic Stretching on Agility, Sprinting, and Jumping Performance in Trained Individuals. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2010, 24, 2001–2011, doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181aeb181. [CrossRef]

- Kilduff, L.P.; Owen, N.; Bevan, H.; Bennett, M.; Kingsley, M.I.C.; Cunningham, D. Influence of Recovery Time on Post-Activation Potentiation in Professional Rugby Players. Journal of Sports Sciences 2008, 26, 795–802, doi:10.1080/02640410701784517. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Duncan, N.M.; Marin, P.J.; Brown, L.E.; Loenneke, J.P.; Wilson, S.M.C.; Jo, E.; Lowery, R.P.; Ugrinowitsch, C. Meta-Analysis of Postactivation Potentiation and Power: Effects of Conditioning Activity, Volume, Gender, Rest Periods, and Training Status. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2013, 27, 854–859, doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31825c2bdb. [CrossRef]

- Abad, C.C.; Prado, M.L.; Ugrinowitsch, C.; Tricoli, V.; Barroso, R. Combination of General and Specific Warm-Ups Improves Leg-Press One Repetition Maximum Compared With Specific Warm-Up in Trained Individuals. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2011, 25, 2242–2245, doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e8611b. [CrossRef]

- Neves, P.P.; Alves, A.R.; Marinho, D.A.; Ferraz, R.; Garrido, N.; Marques, M.C.; Neiva, H.P. The Impact of General and/or Specific Warm-up on Power and Velocity during Squat and Bench-Press Training. Retos 2024, 53, 28–35, doi:10.47197/retos.v53.101851. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B.; Pereira, A.; Neves, P.P.; Sousa, A.C.; Ferraz, R.; Marques, M.C.; Marinho, D.A.; Neiva, H.P. The Role of Specific Warm-up during Bench Press and Squat Exercises: A Novel Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 6882, doi:10.3390/ijerph17186882. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B.; Pereira, A.; Alves, A.R.; Neves, P.P.; Marques, M.C.; Marinho, D.A.; Neiva, H.P. Specific Warm-up Enhances Movement Velocity during Bench Press and Squat Resistance Training. JOMH 2021, doi:10.31083/jomh.2021.069. [CrossRef]

- González-Badillo, J.J.; Sánchez-Medina, L.; Ribas-Serna, J.; Rodríguez-Rosell, D. Toward a New Paradigm in Resistance Training by Means of Velocity Monitoring: A Critical and Challenging Narrative. Sports Medicine - Open 2022, 8, 118, doi:10.1186/s40798-022-00513-z. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.S.; Romanzini, M.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Souza, M.F.; Avelar, A.; Cyrino, E.S. Effect of Different Warm-up Procedures on the Performance of Resistance Training Exercises. Percept Mot Skills 2014, 119, 133–145, doi:10.2466/25.29.PMS.119c17z7. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B.; Pereira, A.; Neves, P.; Marinho, D.; Marques, M.; Neiva, H.P. The Effect of Warm-up in Resistance Training and Strength Performance: A Systematic Review. Motricidade 2021, Vol. 17 (2021): Motricidade, doi:10.6063/MOTRICIDADE.21143. [CrossRef]

- Kapnia, A.Κ.; Dallas, C.N.; Gerodimos, V.; Flouris, A.D. Impact of Warm-Up on Muscle Temperature and Athletic Performance. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 2023, 94, 460–465, doi:10.1080/02701367.2021.2007212. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rosell, D.; Yanez-Garcia, J.M.; Torres-Torrelo, J.; Mora-Custodio, R.; Marques, M.C.; González-Badillo, J.J. Effort Index as a Novel Variable for Monitoring the Level of Effort During Resistance Exercises. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2018, 32, 2139–2153, doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000002629. [CrossRef]

- Pallarés, J.G.; Sánchez-Medina, L.; Pérez, C.E.; De La Cruz-Sánchez, E.; Mora-Rodriguez, R. Imposing a Pause between the Eccentric and Concentric Phases Increases the Reliability of Isoinertial Strength Assessments. J Sports Sci 2014, 32, 1165–1175, doi:10.1080/02640414.2014.889844. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Medina, L.; González-Badillo, J.J.; Perez, C.E.; Pallares, J.G. Velocity- and Power-Load Relationships of the Bench Pull vs. Bench Press Exercises. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2014, 35, 209–216, doi:10.1055/s-0033-1351252. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Medina, L.; González-Badillo, J. Velocity Loss as an Indicator of Neuromuscular Fatigue during Resistance Training. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2011, 43, 1725–1734, doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213f880. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Medina, L.; Pallarés, J.G.; Pérez, C.E.; Morán-Navarro, R.; González-Badillo, J.J. Estimation of Relative Load From Bar Velocity in the Full Back Squat Exercise. Sports Medicine International Open 2017, 1, E80–E88, doi:10.1055/s-0043-102933. [CrossRef]

- González-Badillo, J.J.; Sánchez-Medina, L. Movement Velocity as a Measure of Loading Intensity in Resistance Training. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2010, 31, 347–352, doi:10.1055/s-0030-1248333. [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.L.; Neiva, H.P.; Faíl, L.B.; Gil, M.H.; Marques, M.C. Acute Effects of Low and High-Volume Resistance Training on Hemodynamic, Metabolic and Neuromuscular Parameters in Older Adults. Experimental Gerontology 2019, 125, 110685, doi:10.1016/j.exger.2019.110685. [CrossRef]

- Resende, M.D.A.; Vasconcelos Resende, R.B.; Reis, G.C.; Barros, L.D.O.; Bezerra, M.R.S.; Matos, D.G.D.; Marçal, A.C.; Almeida-Neto, P.F.D.; Cabral, B.G.D.A.T.; Neiva, H.P.; et al. The Influence of Warm-Up on Body Temperature and Strength Performance in Brazilian National-Level Paralympic Powerlifting Athletes. Medicina 2020, 56, 538, doi:10.3390/medicina56100538. [CrossRef]

- Borg, G.A. Psychophysical Bases of Perceived Exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1982, 14, 377–381.

- Arifin, W.N. Sample Size Calculator (Version 2.0) [Spreadsheet File] Available online: https://wnarifin.github.io/ssc_excel.html.

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Batterham, A.M.; Hanin, J. Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2009, 41, 3–12, doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278. [CrossRef]

- Contreras, B.; Vigotsky, A.D.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Beardsley, C.; Cronin, J. A Comparison of Gluteus Maximus, Biceps Femoris, and Vastus Lateralis Electromyography Amplitude in the Parallel, Full, and Front Squat Variations in Resistance-Trained Females. Journal of Applied Biomechanics 2016, 32, 16–22, doi:10.1123/jab.2015-0113. [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Moysi, J.; Idoate, F.; Olmedillas, H.; Guadalupe-Grau, A.; Alayón, S.; Carreras, A.; Dorado, C.; Calbet, J.A.L. The Upper Extremity of the Professional Tennis Player: Muscle Volumes, Fiber-type Distribution and Muscle Strength. Scandinavian Med Sci Sports 2010, 20, 524–534, doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00969.x. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. Warm Up I: Potential Mechanisms and the Effects of Passive Warm Up on Exercise Performance. Sports Medicine 2003, 33, 439–454, doi:10.2165/00007256-200333060-00005. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. Warm Up II: Performance Changes Following Active Warm Up and How to Structure the Warm Up. Sports Medicine 2003, 33, 483–498, doi:10.2165/00007256-200333070-00002. [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.R.; Viana, R.B.; Silva, M.H.; Guimarães, T.C.; Vieira, C.A.; Santos, D.D.A.T.; Gentil, P.R.V. Postactivation Potentiation Improves Performance in a Resistance Training Session in Trained Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2021, 35, 3296–3299, doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003367. [CrossRef]

- Ratamess, N.A.; Alvar, B.A.; Evetoch, T.K.; Housh, T.J.; Kibler, W.B.; Kraemer, W.J.; Triplett, N.T. Progression Models in Resistance Training for Healthy Adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2009, 41, 687–708, doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).